Cancer (medicine)

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| C00-C97 | Malignant neoplasms |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

In medicine, cancer is the uncontrolled reproduction and proliferation of cells , i. H. a malignant neoplasm ( malignant neoplasm ) or a malignant (malignant) tumor (cancerous tumor, malignancy ). Malignant means that, in addition to cell proliferation, settlement ( metastasis ) and invasion of healthy tissue also take place. In the narrower sense, the malignant epithelial tumors ( carcinomas ), then also the malignant mesenchymal tumors ( sarcomas) meant. In a broader sense, malignant hemoblastoses are also referred to as cancer, such as leukemia as “blood cancer”.

All other tumors, which also include benign (benign) neoplasms, are not referred to as cancer in modern medicine. These are tissue increases or masses in the body that do not form metastases . This applies to both swelling in the event of inflammation and benign neoplasms (new formation of body tissue due to dysregulation of cell growth).

Benign tumors such as birthmarks and lipomas are not referred to as cancer in technical terms, but they can still be dangerous because they can degenerate or impair the functioning of vital organs (such as the cerebellar bridge angle tumor ). In common parlance, cancer is a collective term for a large number of related diseases in which body cells can grow uncontrollably , divide and displace and destroy healthy tissue . According to the current state of knowledge, this phenomenon is limited to placental mammals , provided that hemoblastosis is disregarded. Cancer has different triggers, all of which ultimately lead to a disruption of the genetically regulated balance between the cell cycle (growth and division) and cell death ( apoptosis ).

The medical discipline dedicated to cancer is oncology .

Occurrence and course

|

Standardized incidence (new cases) / 100,000 inhabitants (European standard) and relative five-year survival rates in% in Germany 2016 |

||||

| Art | Incidence | 5 year survival rate | ||

| ♀ | ♂ | current | 1980s | |

| All in all | 348.3 | 422.9 | ♀: 65; ♂: 59 | ♀: 50-53; ♂: 38-40 |

| with children | 17th | approx. 85 | approx. 67 | |

| Oral cavity and throat | 6.5 | 17.6 | ♀: 58-68; ♂: 42-50 | |

| esophagus | 2.4 | 9.4 | ♀: 11-36; ♂: 14-31 | <10 |

| stomach | 7.2 | 14.8 | ♀: 29-40; ♂: 24-42 | |

| Intestines | 31.8 | 50.7 | ♀: 60-66; ♂: 58-66 | approx. 50 |

| pancreas | 10.4 | 14.4 | ♀: 4-19; ♂: 5-14 | |

| Larynx | 0.8 | 5.4 | ♀: 63; ♂: 50-69 | |

| lung | 31.4 | 57.5 | ♀: 17-26; ♂: 10-19 | |

| Malignant melanoma | 19.9 | 21.0 | ♀: 89-96; ♂: 83-94 | |

| Mammary gland | 112.2 | 1.1 | ♀: 86-90; ♂: 77 | |

| cervix | 8.7 | 62-70 | ||

| Uterine body | 16.5 | 75-82 | ||

| Ovaries | 11.1 | 38-50 | ||

| prostate | 91.6 | 86-91 | ||

| Testicles | 10.2 | 99-100 | ||

| kidney | 7.5 | 15.7 | ♀: 73-82; ♂: 69-81 | approx. 50 |

| bladder | 9.0 | 34.7 | ♀: 36-53; ♂: 48-63 | |

| Nervous system | 5.9 | 7.6 | ♀: 15-32; ♂: 14-38 | |

| thyroid | 11.1 | 5.1 | ♀: 90-97; ♂: 71-93 | ♀: approx. 77; ♂: approx. 67 |

| Hodgkin's disease | 2.4 | 3.2 | ♀: 75-92; ♂: 78-94 | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 12.0 | 16.4 | ♀: 67-74; ♂: 59-76 | |

| Leukemias | 8.6 | 13.5 | ♀: 53-63; ♂: 52-60 | |

| Source: Cancer in Germany for 2015/2016 - frequencies and trends. (PDF) A joint publication by the Robert Koch Institute and the Society of Epidemiological Cancer Registers in Germany. V. , accessed on March 11, 2020 . | ||||

In principle, any organ in the human body can be attacked by cancer. However, there are significant differences in frequency according to age, gender, collective affiliation, geographic region, dietary habits and similar factors. There are over 100 different types of cancer. In Germany, cancer occurs more frequently in organs such as the mammary gland (women), prostate (men), lungs and colon .

In Germany, cancer is the second most common cause of death after cardiovascular diseases . However, not every cancer course is fatal if therapy is started in good time or a slowly growing cancer does not appear until the patient is so old that the patient dies from another cause of death. The current from the Society of Epidemiological Cancer Registers in Germany e. V. (GEKID) 2017 published relative 5-year survival rates for all types of cancer refer to patients who fell ill in 2013 and 2014. For women the value was 65%, for men it was 59%. In northern European countries there are even cheaper values. For example, in Finland , the 5-year survival rates of women and men who fell ill in 2014-2016 were 68.6% and 66.3%, respectively. In oncology, cured is a patient who survives for at least five years without relapse ( relapse ). This definition of “cured” is problematic because many relapses only occur at a later point in time. The cancer success statistics therefore include patients who later die of cancer. However, for most types of cancer after five years of recurrence-free survival, the average life expectancy approaches that of their peers.

Cancer manifests itself in various forms and clinical pictures. For this reason, no general statements can be made regarding life expectancy and chances of recovery. There are currently around 100 different types of cancer known, some of which differ greatly in terms of their chance of survival, treatment options and the tendency to form metastases .

The incidence of most cancers increases significantly with age , so that cancer can also be viewed as an aging disease of cell growth . In addition, smoking , other carcinogenic noxae , familial disposition (disposition) and viral infections are the main causes of cancer. The Nobel Prize winner Harald zur Hausen carries 20 percent of all cancers in infections back ( human papillomaviruses (HPV), hepatitis B and C, pylori Helicobacter , EBV , human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1 ), certain parasites ( bladder cancer in the Nile Delta ) and Merkel cell polyoma virus ). In Germany and the United States, this proportion is estimated to be significantly lower and assumed to be around 5 percent. The fact that a woman has children leads to a reduction in the risk of cancer by more than 2/3 compared to childless women; the reduction is slightly lower for men.

Through cancer prevention and early detection of cancer risk can (depending on the time of diagnosis, the type of cancer and one for optimum age of the patient) under certain circumstances, be significantly reduced.

Cancer is by no means a modern disease. In terms of evolutionary history, it is a very old disease that in principle can affect at least all mammals. The oldest tumor findings are (as of 2003) dinosaur bones of the Hadrosauridae , in which hemangiomas were recognized in fossil remains.

In the human medical sense, cancer probably does not occur in other groups of organisms such as plants or reptiles; Tissue growths are more likely to be viewed as benign tumors. The immediate ancestors of humans (Homo), such as Australopithecus (2 to 4.2 million years ago), also had cancer. Cancer diseases have accompanied humanity throughout evolution . In the Ebers Papyrus from the period 1550 BC cancers are mentioned.

Name story

The German term for certain tumors and ulcers with "cancer" (from Middle High German krëbez "eating ulcer, carcinoma, cancer") comes from ancient Greek , where karkínos (καρκίνος) also means both animals (cancer or crab) and disease (Cancerous ulcer, carcinoma) was named. As a name for ulcers, the name first appears in the Corpus Hippocraticum . In the 2nd century AD, Galenus explains the origin of the name according to the similarity of swollen veins of an external tumor with cancerous legs:

“… And on the breast we often saw tumors that were very similar to the shape of a cancer. Just as the animal's legs lie on both sides of the body, the veins leave the tumor, which is shaped like the cancerous body. "

Aristotle called cancer superficially detectable, infiltrating and ingrowing ulcers into neighboring organs (such as advanced skin cancer or breast cancer ).

The term “cancer” (Latin cancer ) can also be found, for example, for ulcers in sexually transmitted diseases (“chancre”) and in the word “water cancer ” for noma .

In the Middle Ages, the chest area belonged to the zodiac sign Cancer (cf. Homo signorum ).

history

An ulcerated process of the skin that could be regarded as cancer was discovered in the 15th century BC. Mentioned in the Ebers papyrus . Hippocrates or the Corpus Hippocraticum differentiated tumors of the skin from “cancer” of the mammary gland and internal organs. A deeper understanding of the nature of cancer and the ontogenetic relationships can be found in Galen in the 2nd century AD. Galen differentiated the tumors into "natural" (physiological) hyperplasias , "nature exaggerating" granulating inflammations and "unnatural" (good- and malignant) growths . Specific substances as a cause of cancer were mentioned in the 16th century by Paracelsus ( arsenic (V) sulfide referred to as " realgar " in mining as the cause of lung cancer) and in the 18th century by Percivall Pott ( soot as the cause of scrotal cancer). (The connection between aromatic hydrocarbons in shale oil, soot, tar, paraffin and coal was illustrated by Ernest Kennaway in 1924). Other substances recognized as causing cancer were aromatic amines such as aniline and benzidine, which the surgeon Ludwig Rehn found in 1895 in workers in the dye industry suffering from bladder cancer. The nature of the cancer has been using since 1866 by Ernst Abbe developed microscopes and the Humoralpathologie detaching cellular pathology detected accurately Virchow.

Carcinogenesis

It has been known since the mid-19th century research by the pathologist Rudolf Virchow ("omnis cellula e cellua") that cancer is the growth of body cells .

In a healthy organism, the cell types that make up the various tissues of the organs are formed and regenerated in a balanced species-specific equilibrium, which is known as homeostasis . In this state of homeostasis there is a balance between the reproduction of cells ( cell proliferation ) and cell death. Most of the cell death occurs through apoptosis , in which the cells “commit suicide”. In pathological situations, this death can also occur through necrosis . In cancer, this balance is altered in favor of cell growth. The cancer cells grow unhindered because inhibitory signals are not recognized or not carried out. The reason lies in defects in the required genetic code that have arisen as a result of mutations in the genome .

Around 5,000 of the total of 25,000 human genes are responsible for the safe maintenance of the genetic code from one cell generation to the next. These so-called tumor suppressor genes monitor the correct sequence of the base pairs in the DNA after each reduplication , decide on the need for repair processes, stop the cell cycle until the repairs have been carried out and, if necessary, initiate programmed cell death ( apoptosis ) if the repair is not successful leads. In addition, the protooncogenes are responsible for initiating or maintaining the proliferation of the cell and its subsequent development into a certain cell type ( differentiation ).

According to the theory of carcinogenesis , which is now considered plausible , the primary disease event is a change in one of these guardian genes - either due to a copying error or, more rarely, due to an innate mutation. This gene can then no longer correctly accompany the partial step it monitors, so that further defects can occur in the next cell generation. If a second guardian gene is affected, the effect increases continuously. If apoptosis genes (e.g. p53 ) are also affected, which in such a situation would have to trigger programmed cell death, these cells potentially become immortal . By activating the proto-oncogenes, a cancer is stimulated to grow, which can lead to a mass and consequently to pain. Several such mutations are necessary for cancer development ( multiple hit model ). Here, Peter Nowell's assumption has been confirmed that at least six to seven mutations are necessary for a malignant tumor to develop .

The proliferation of a cell that has been modified in the relevant genes to form a cluster of cells increases the likelihood of a further relevant genetic change in the multi-step process, since errors can occur with every DNA copying process. Such changes can also be induced by external influences (e.g. carcinogenic substances, ionizing radiation , oncoviruses ), or by genetic instability of the changed cell population. Irritating stimuli can accelerate this process by increasing the proliferation. While one or two mutations may be sufficient for some tumors, there are also tumors in which up to ten different mutations must have occurred. Some of these necessary mutations can be inherited, which explains why very young children can develop cancer and that cancer can occur more frequently in so-called "cancer families". A typical example of this is hereditary xeroderma pigmentosum . Close relatives of breast cancer patients are twice as likely to develop breast cancer as the rest of the population. In the intermediate steps of tumor development (promotion and progression), non-genotoxic processes play a major role, which could lead observers to classify these influences as the actual "carcinogens".

Through further changes in the DNA, the cell can develop additional properties that make treatment of the cancer more difficult, including the ability to survive in a lack of oxygen, to build up its own blood supply ( angiogenesis ) or to migrate out of the bandage and to settle in foreign tissues such as bones ( bone metastasis ) , Lungs ( lung metastasis ), liver ( liver metastasis ) or brain ( brain metastasis ) (metastasis). It is only through this ability that cancer gains its deadly potency: 90% of all cancer patients in whom the disease is fatal do not die from the primary tumor, but from the diseases that result from the metastasis.

The immune system basically tries to track down and fight uncontrollably growing cells (English immune surveillance ). The first assumptions that tumors can shrink or disappear as a result of an immune reaction were made by Louis Pasteur , but a more detailed description was only given in 1957 by Thomas and Burnet. However, since these resemble normal body cells in many ways, the differences and thus the defense measures are usually not sufficient to control the tumor.

Cancer cells are often aneuploid , which means they have an altered number of chromosomes . It is currently being investigated whether the aneuploidy of cancer cells is the cause or consequence of the disease. Linked to this is the theory that the development of cancer is not or not only due to the mutation of individual genes , but primarily to changes in the entire set of chromosomes. These differences in the chromosome sets of degenerate cells also led to the consideration of some types of cancer as each new species.

Multi-step model or three-step model

Most cancer researchers start from the so-called 'multi-step model' of cancer development. The multi-step model tries to understand the cause of cancer development. Every single step corresponds to a specific genetic change. Each of these mutations in turn drives the gradual transformation of a single normal cell into highly malignant offspring ( malignant transformation ). The actual malignancy (malignancy) of the degenerate cell is reached in the phase of progression. The terms promotion and progression are increasingly being replaced by the term co-carcinogenesis.

The older, so-called 'three-stage model', on the other hand, divides cancer development into phases: initiation, doctorate and progression. This should explain the years or decades of latency between the initial DNA damage , i.e. the transformation of a single cell, and the detectable tumor. The problem with the three-stage model is that the terms initiation , promotion and progression only describe and do not explain the cause.

Monoclonal model vs. Stem cell model

The monoclonal theory of carcinogenesis assumes that all tumor cells are the same; H. if they are able to divide, they can become the starting point for new tumors at any time. The stem cell model, on the other hand, describes a hierarchy: the normal cancer cells are derived from a few cancer stem cells, which enlarge the tumor through frequent division. Such stem cells could explain why chemotherapy or radiation therapies initially make an existing tumor disappear, but after a while the tumors reappear : Since the stem cells divide significantly less often than tumor cells, they are also less vulnerable to most chemotherapies . New, rapidly dividing tumor cells would then be formed from the remaining stem cells. The extent to which such tumor stem cells exist and whether they can be eliminated despite resistance to previous treatment approaches is the subject of current research.

In 2009 there were first indications of such resistance in breast cancer stem cells. In 2012, some independent research provided additional evidence of stem cells in benign tumors of the skin and intestines , but also in glioblastomas , a malignant brain tumor.

A new theory by cancer research pioneer Robert Weinberg compares the behavior of tumors and embryos (see also the section on historical assumptions ). A fertilized human egg cell ( zygote ) or the embryo is not passively supplied by the uterine lining , but instead actively nests in it through invasion and attracts small blood vessels with certain factors for supply. After that, the zygote / embryo divides very frequently and thus multiplies exponentially. It is precisely these three behaviors that surprisingly characterize an invasive metastatic cancer cell. Since cancer cells are known to reactivate embryonic genes (e.g. for alpha-1 fetoprotein ), the conclusion that cancer arises from body or adult stem cells (see above), which repeat an earlier stage of development through malfunction, albeit completely unregulated . Therefore, malignant tumors, i. H. Sarcomas and carcinomas, very likely restricted to mammals, as only they have the embryonic invasion genes.

Historical assumptions

In 1902, John Beard wrote that cancer cells resemble trophoblastic embryonic cells . At the beginning of a pregnancy , these cells ensure that the embryo can implant itself in the uterus. The growth is aggressive and chaotic. The cells divided quickly and get their energy from sugar fermentation . They suppressed the mother's immune system and produced human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which is now recognized as a tumor marker . The growth does not stop until the embryo starts producing pancreatic enzymes from the seventh week . Without these enzymes the most malignant tumor, chorionic carcinoma , would develop . The assumption that cancerous tumors derive energy from sugar fermentation (i.e., the tumor would live anaerobically ) has been the basis for many outdated treatments.

In 1908, Vilhelm Ellermann (1871-1924) and Oluf Bang (1881-1937) discovered a virus that caused leukemia in chickens.

It was then Peyton Rous who, in 1911, filtered an extract from a muscle tumor with the high filter fineness of 120 nanometers, with which he could produce cancer again. He suspected a virus in this extract. In 1966, Rous received the Nobel Prize for this discovery of the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV).

Cancer Triggers Theories

According to the theory described above, influences that change the genetic makeup are primarily carcinogenic . The cell is particularly sensitive to this during cell division ; therefore, cells that divide quickly are particularly vulnerable. The majority of cancers, 90–95% of cases, are caused by environmental factors. Influences that prevent the immune system from recognizing and eliminating degenerate cells are also considered to be carcinogenic. The following are particularly dangerous:

Environmental toxins and radiation

- Physical noxes

-

Ionizing radiation such as ultraviolet light , X-rays or radioactive radiation .

Example: In the cardiac (coronary) examination using computed tomography , patients buy the increased sensitivity of the examination method with an increased risk of cancer. American scientists calculated that one of 143 women examined by means of coronary CT in twenty-year- olds will develop cancer in the course of their life as a result of this angiography radiation, but only one of 686 men of the same age. Coronary CT angiography appears to significantly increase the risk of cancer, especially in women and young people. After a skull CT, the cancer risk for women is 1: 8,100 and for men 1: 11,080. Based on 70 million CT scans performed in the US in 2007, 29,000 future cancers are to be feared. - Fibers such as asbestos and nanoparticles such as titanium dioxide , which in themselves have a chemically neutral reaction, can cause cancer or cancer precursors due to their geometry and size in the body.

-

Ionizing radiation such as ultraviolet light , X-rays or radioactive radiation .

- Chemical noxae

- Mutagenic chemicals . The most important are larger polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons , benzene , chromium (VI) compounds and nitrosamines . Arsenic compounds , soot , asbestos and selenium can also cause cancer .

Biological influences

-

Oncoviruses (according to estimates by the American Cancer Society, around 17% of cancer cases)

- DNA viruses , e.g. B. the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which can lead to liver cell carcinoma , and the human papillomavirus (HPV), which can lead to cervical carcinoma

- RNA viruses , e.g. B. the hepatitis C virus

- Retroviruses , e.g. B. HIV , HTLV

- Bacteria, e.g. B. Helicobacter pylori

- Living organisms (or their excretion products), for example Schistosoma haematobium , cat liver fluke and Chinese liver fluke

- Stem cells , especially embryonic ones, can cause cancer under certain circumstances.

- Immunosuppressive therapies after an organ transplant can increase the risk of cancer by three to six times that of the normal population. The most common cancers after a transplant include Kaposi's sarcoma and other forms of skin cancer, as well as a group of various lymphoma-like diseases called PTLD . In general, the immune system plays an important role in the development of cancer, because it is in principle able to recognize degenerate cells and successfully fight them. In addition, in rare cases already contained tumors can also be transplanted.

- Height: Studies in both men and women show a connection between height and the risk of cancer later in life. The reason for this could be that, as has long been known, many types of cancer respond to the same growth factors that lead to growth in youth.

- Only in animals: some tumors can be transmitted from animal to animal; infectious tumors include sticker sarcoma in dogs and DFTD ( Devil Facial Tumor Disease ) in the devil .

Lifestyle and living conditions

- The Million Women Study confirmed the belief that being overweight increases the risk of cancer. An increased body mass index had both the incidence and the mortality rise following cancers: endometrial cancer , esophageal cancer , kidney cancer , multiple myeloma , pancreatic cancer , non-Hodgkin's lymphoma , ovarian cancer , breast cancer and colon cancer after menopause . According to the authors of the study, 5% of all cancer cases can be traced back to overweight and obesity . According to a recent study, up to 49% of certain types of cancer are linked to obesity. In vivo , NK cells failed to reduce tumor growth in obesity.

- Mental causes

- That personality or certain internal conflicts cause cancer is unconfirmed. However, it is conceivable that mentally stressed (e.g. stressed) people behave more riskily (e.g. smoke more, sleep too little).

- Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE), e.g. In a study of 17,000 participants, for example, a parent's alcoholism or experience of physical or emotional violence were linked to greatly increased risks for a variety of symptoms, from Alzheimer's to depression, substance abuse, low income, early pregnancy to cancer, obesity and diabetes. At least one of the defined risk factors was found in around half of the participants. The number of risk factors present correlated strongly with the severity of the symptoms.

Quantitative assessment of various factors

| factor | Percentage ownership % |

|---|---|

| food | 35 |

| Tobacco use | 30th |

| Infections | 10 |

| Reproductive and sexual behavior | 7th |

| Workplace | 4th |

| alcohol | 3 |

| geophysical factors (e.g. sunlight exposure, indoor exposure to radon, general radiation exposure) | 3 |

| general (anthropogenic) environmental pollution (e.g. indoor space, air, drinking water, soil, contaminated sites, pesticide input) | 2 |

| Industrial products | <1 |

| Food additives | <1 |

| Medicines and medical procedures | 1 |

| unknown | ? |

Consequences of tumor growth

The consequences of malignant tumor growth for the organism are very diverse and are very different for each patient. On the one hand, tumor growth can lead directly to local effects in neighboring tissue. On the other hand, tumors can also cause systemic effects (affecting the entire organism). The development of daughter tumors, which in turn can lead to a number of functional disorders in the affected organs, is often decisive for the course of the disease.

Local effects

When tumors grow, they can displace the healthy neighboring tissue without destroying it, or they can grow into the neighboring tissue in a destructive manner (invasive, destructive growth). Both forms of growth can lead to local complications. For example, a blood vessel can be compressed through expansive growth. The subsequent circulatory disturbance of the dependent tissue can lead to the death of this tissue ( necrosis ). Infiltrating-destructive growth can lead to breakthroughs ( perforations ) and fistulas in hollow organs such as the intestine, for example, by destroying the tissue . Tumor fistulas often lead to further complications due to infections. In lung cancer, breast cancer and other tumors in the chest, it may by an exudate in a pleural effusion come.

Systemic effects

Tumors can affect the entire organism in different ways. Daughter tumors originating from the primary tumor can settle in other organs and destroy tissue here through local growth and lead to functional disorders. Many patients experience a general decline in strength and weight ( tumor cachexia , emaciation ) in the course of the cancer . So-called paraneoplastic syndromes are also included in the systemic effects of tumors . This leads to characteristic symptoms in various organ systems that are ultimately caused by the tumor. For example, lung cancer can lead to a disruption of the hormonal regulation of the water balance ( Schwartz-Bartter syndrome ).

Most patients do not die from the primary tumor, but from the effects of its metastases. Their uncontrolled reproduction damages vital organs until they can no longer fulfill their function. Frequent immediate causes of death are vascular occlusions (embolisms), tumor cachexia or infections that the organism can no longer control ( sepsis , blood poisoning ).

Paraneoplasms

Tumor patients sometimes have symptoms or diseases that are not directly triggered by tumor cells, but are related to the tumor disease. Paraneoplasms usually go away when the tumor is completely healed. Occasionally, the paraneoplasia occurs before the primary tumor is discovered. Here are some examples of paraneoplasms:

- TIH (tumor-induced hypercalcemia )

- Thrombo- embolism

- Skin changes: paraneoplastic pemphigus , erythema gyratum repens , pyoderma gangrenosum , reader Trélat syndrome , acrokeratosis paraneoplastica

- PNS (paraneoplastic neurological syndromes): LEMS ( Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome ), PLE (paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis ), paraneoplastic bulbar encephalitis, POM (paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome), PCD (paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration), paraneoplastic myelitis , PEM (paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis)

- SIADH (syndrome of inadequate ADH secretion)

See the Paraneoplastic Syndrome article for more details .

Classification of the types of cancer

Malignant tumors differ from benign (benign) tumors by three characteristics: They grow

- infiltrating : the tumor cells cross tissue boundaries and grow into neighboring tissue

- destructive : they destroy surrounding tissue

- metastasizing : they form daughter tumors ( metastases ) via blood and lymph vessels or by draining .

The staging of malignant tumors is based on the international TNM classification . The focus is T0 to T4 for the expansion of primary T umors, N0 to N3 for the lymph node involvement (English N ode) and M0 or M1 for the absence or presence of long-distance M etastasen.

Special forms

In addition, a distinction is made between semi-malignant tumors and facultative or obligatory precanceroses . Semi-malignant tumors only meet two of the criteria mentioned, precancerous lesions are tissue changes that can dedifferentiate into malignant tumors with an increased probability, but have not yet grown in an infiltrating or metastatic manner.

The most common semimalignant tumor is the basalioma , a tumor of the basal cell layer, especially of the sun-exposed skin, which grows in an infiltrating and destructive manner, but does not metastasize. If left untreated, the tumor can destroy the entire face, including the facial bones.

By far the most common precancerous condition is cervical intraepithelial neoplasia , an overgrowth of the cervix, the cells of which show signs of malignancy in terms of cell biology , but have not yet infiltrated, destroyed or metastasized from the tissue . As a preventive measure, women are recommended to take the annual Papanicolaou uterine smear, also known as the PAP smear, as precancerous lesions can be treated much better.

Fabric origin

Cancer tumors are classified according to the type of tissue that has deteriorated. Carcinomas , i.e. tumors that originate from the epithelium , make up the vast majority of all cancers . These are further differentiated into squamous or squamous carcinomas, which are derived from keratinized and uncornified (mucous) skin, and adenocarcinomas , which are derived from the glandular epithelium and are further differentiated depending on their origin and structure. Carcinomas emanating from the transitional tissue are known as urothelial carcinomas and are typical of bladder cancer , among other things . Another large group are the hematological forms of cancer of the blood and the blood-forming organs, which can be subdivided into leukemia and lymphoma , also known as "lymph gland cancer". There are also less common malignant tumors such as sarcomas originating from the supporting and connective tissue , neuroendocrine tumors such as the carcinoid or teratomas originating from embryonic tissue (especially of the gonads ).

localization

The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) classifies malignant tumors according to their location .

statistics

High quality data on cancer incidence worldwide has been collected since the 1960s and published by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a WHO organization . The WHO also publishes data on cancer mortality for selected countries. Incidence data are available for about one sixth of the world's population and mortality data for one third. In Germany, the Robert Koch Institute publishes together with the Society of Epidemiological Cancer Registers. V. (GEKID) the report "Cancer in Germany" every two years. The 10th edition was published in 2015 with data up to 2012. A report is published every five years in Switzerland, and the second edition in 2016.

The number of diagnosed cancers is increasing worldwide. The WHO states that 14.1 million people were diagnosed with cancer in 2012 - 11 percent more than in 2008. The number of cancer deaths rose by 8 percent to 8.2 million in the same period. In Switzerland, as in the western developed countries, the increase is due to the demographic aging of the population.

At the same time, the incidence and mortality of most cancers (including the lung, colon, breast, and prostate) are falling in the United States and most Western countries. "We have been observing for 15 years that cancer mortality is falling in the USA and Germany," says Nikolaus Becker from the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg. US statistics attribute the greatest share of the success to the early detection of colon cancer . Lung cancer rates decrease in men because they smoke less.

In some developing and emerging countries, however, the incidence rates are increasing due to the adoption of an unhealthy lifestyle (smoking, lack of physical activity, consumption of energy-dense foods). For example, a few of these countries already have lung and colon cancer rates higher than the United States. However, developing countries are still disproportionately affected by infectious cancers (cervix, liver, stomach).

The most common cancers worldwide are lung cancer, breast cancer, and colon cancer.

Statistically, one in three Europeans will develop cancer in their lifetime. In Germany around 395,000 people develop cancer every year, of which around 195,000 are women and 200,000 men. Most cases occur after the age of 60 years. With around 107,000 cases, those under 60 make up only around a quarter of all new cancer cases. According to a US study, around 20,000 people worldwide die every day from complications from cancer. In 2007 there were around 7.6 million deaths from cancer - 4.7 million of them in developing countries. According to this source, the total number of all annually newly diagnosed cancers worldwide is given as 12.3 million. This was the first estimate of its kind. For death from the effects of smoking, researchers continue to expect the numbers to rise. In the 20th century, tobacco consumption (cf. tobacco smoke ) was the cause of around 100 million deaths; in the 21st century, around one billion deaths can be expected.

Every year in Germany around 1750 children under the age of 15 develop cancer. In this age group, leukemia (34 percent), tumors of the brain (22 percent) and the spinal cord, and lymph node cancer (12 percent) are most frequently diagnosed. Boys get sick almost twice as often as girls. Five years after diagnosis, 81 percent of children are still alive if they seek treatment. In the 1950s it was less than 10 percent. After five years, the children are considered cured. This rate varies between 59 percent for AML and 90 percent for ALL to 97 percent for retinoblastoma . In Switzerland, around 250 children and young people under the age of 16 develop cancer every year.

Since the turn of the millennium, the 5-year survival rates of most cancers have increased, with large differences between individual countries (as of 2018). Countries with the highest cancer survival rates include South Korea , Japan , Israel , Australia, and the United States .

The statistical figures for Germany for the period from 2011 to 2012 show a relative 5-year survival rate of 62 percent for men and 67 percent for women for all types of cancer. After this five-year survival period, the survivors then usually have an average life expectancy that corresponds to that of their peers in the general population. Only in very few types of cancer is this not the case; a 10-year period has to be waited for. Approx. 90% of all cancer cures are achieved exclusively through so-called locoregional treatment, which is locally targeted to the tumor region, i.e. through surgery and radiation therapy (»steel and beam«).

Spontaneous remissions are very rare . They only occur in about 1: 50,000–100,000 cases. Spontaneous remission is the complete or partial disappearance of a malignant tumor in the absence of all treatments or with treatments for which no proof of effectiveness has yet been established. However, the probability of such spontaneous remissions is less than the probability of a misdiagnosis. Despite intensive research, it is currently not possible to induce specific spontaneous remissions therapeutically.

Many malignant patients apparently do not appear in cancer statistics. Malignant tumors are often only revealed by a dissection. In Hamburg, the autopsies carried out between 1994 and 2002 at the Institute for Forensic Medicine were examined more closely in terms of cancer diagnosis. 8844 sections were included in the evaluation. A malignant tumor was found in 519 deaths (5.9%). Only 58 of these cases had been reported to the cancer registry . Two thirds of the malignancies were known during their lifetime, 27.2% were only discovered during dissection. In a good half, cancer was the cause of death . Even of the lethal tumors, 17% were not recognized until the autopsy. The cancer registries, which are based on tumor diseases known during lifetime, do not seem to be exact. With the exception of malignant melanoma, all skin cancers are not recorded in the cancer statistics. This is why the cancer registry in Germany does not contain the 171,000 cases of new cases of white skin cancer ( spinalioma , basalioma ) in Germany.

| Affected organ (+ ICD-10 code) | male | Female | total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| diagnosed | died | diagnosed | died | diagnosed | died | |

| All | 246,700 | 115,870 | 223.100 | 99,572 | 469,800 | 215,442 |

| Lungs (C33, C34) | 33,960 | 29,505 | 15,570 | 12,841 | 49,530 | 42,346 |

| Intestines (C18 - C21) | 35,350 | 13,726 | 30,040 | 12,936 | 65,390 | 26,662 |

| Breast (C50) | 520 | 136 | 71,660 | 17.209 | 72,180 | 17,345 |

| Pancreas (C25) | 7,390 | 7,327 | 7,570 | 7,508 | 14,960 | 14,835 |

| Stomach (C16) | 9.210 | 5,929 | 6,660 | 4,581 | 15,870 | 10,510 |

| Prostate (C61) | 63,440 | 12.134 | 63,440 | 12.134 | ||

| Blood: leukemia (C91 - C95) | 6,340 | 3,908 | 5,080 | 3,400 | 11,420 | 7,308 |

| Cardioid (C64) | 8,960 | 3,060 | 5,540 | 2,041 | 14,500 | 5.101 |

| Ovary (C56) | 7,790 | 5,529 | 7,790 | 5,529 | ||

| Urinary bladder (C67, D09.0, D41.4) | 20,850 | 3,611 | 7,490 | 1.921 | 28,340 | 5,532 |

| Lymph glands: Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (C82 - C85) | 7,270 | 2,926 | 6,430 | 2,658 | 13,700 | 5,584 |

| Oral cavity and throat (C00-C14) | 9,520 | 3,776 | 3,490 | 1,170 | 13,010 | 4,946 |

| Esophagus (C15) | 4,800 | 3,655 | 1,380 | 1,135 | 6,180 | 4,790 |

| Uterus (C54, C55) | 11,280 | 2,420 | 11,280 | 2,420 | ||

| Skin: Malignant Melanoma (C43) | 8,910 | 1,365 | 8,890 | 1,135 | 17,800 | 2,500 |

| Cervix (C53) | 4,880 | 1,596 | 4,880 | 1,596 | ||

| Larynx (C32) | 3,610 | 1,275 | 510 | 209 | 4.120 | 1,484 |

| Thyroid (C73) | 1,710 | 279 | 4,160 | 429 | 5,870 | 708 |

| Blood: Hodgkin's disease (C81) | 1,160 | 193 | 920 | 148 | 2,080 | 341 |

| Testicles (C62) | 3,970 | 153 | 3,970 | 153 | ||

| Year of description | Type of cancer | job |

|---|---|---|

| 1775 | Testicular cancer | Chimney sweep (contact with benzo [ a ] pyrene contained in soot ) |

| 1820 | Skin cancer | Lignite workers (contact with lignite tar ) |

| 1879 | Lung cancer | Miners (inhalation of coal dust ) |

| 1894 | Skin cancer | Seafarers (sun exposure; contact with tarred ropes, planks, etc.) |

| 1895 | Bladder cancer | Workers in contact with Fuchsin |

| 1902 | Skin cancer | X-ray staff |

| 1912 | Lung cancer | Professions with chromate contact |

| 1922 | Scrotal and skin cancer | Professions with contact with shale oils |

| 1928 | leukemia | Professions with contact with benzene |

| 1933 | Nose and lung cancer | Professions with contact with nickel |

| 1933 | Lung cancer | Professions with exposure to asbestos |

| 1938 | Pleural mesothelioma | Professions with exposure to asbestos |

| 1954 | Peritoneal mesothelioma | Professions with exposure to asbestos |

| 1972 | Lung cancer | Occupations with contact to halogenated ethers (“haloethers”), especially dichlorodimethylether |

| 1974 | Liver angiosarcoma | Occupations with contact with vinyl chloride |

| 1988 | Adenocarcinomas of the main and paranasal sinuses | Professions with contact with hardwood dust (dust from oak and beech wood ) |

Current situation in Germany

With 500,000 new cases per year, cancer is a key health problem in Germany, according to current statistics for 2018/2019. According to the German Cancer Aid Foundation, around half of the German population will develop one of over 200 types of tumor during their lifetime. The most common new cases are breast cancer in women with 71,900 cases and prostate cancer in men with 60,700 new cases per year. Around 2,000 children and adolescents in Germany develop cancer every year.

Treatment options

In order to be able to treat a tumor successfully, the most effective treatment methods for the respective tumor must be used. However, which methods are the most effective depends on the individual tumor. The established approach is based on the identification of the origin of the tumor within the body (clinical diagnosis including ICD ) and the pathological findings (histological diagnosis). Based on the origin, a therapy can then be determined on the basis of guidelines (for frequent cancer diseases). It is assumed that tumors of the same origin can be treated similarly. These guidelines are often missing for rather rare forms of cancer. Further aids that can lead to a more targeted selection of therapy methods are additional diagnostic procedures ( cancer diagnosis or tumor diagnosis ).

In addition to the currently established method of therapy based on the origin of the tumor, attempts are now being made to further subdivide the tumors. The view that every cancer has its own tumor biology has largely prevailed. The goal is to tailor the therapy to each patient. This approach to individualization of therapy is known as personalized medicine .

Current treatment methods

Surgical removal (operation)

- Resection : surgical removal of the tumor and neighboring lymph nodes ( lymphadenectomy ).

Therapies with the aim of stopping growth or regression of the tumor

-

radiotherapy

- with radioactive substances

- through radioactive iodine ( thyroid actively absorbs iodine )

- with x-rays

- with electrons or neutrons

- with proton therapy or ion irradiation (irradiation with protons or ions that spares the tissue surrounding the tumor)

- with radioactive substances

- Drug treatment

- With cytostatics ( chemotherapy ): the rate of division of the cancer cells should be reduced or the division should be stopped entirely

-

Targeted cancer therapy with drugs (monoclonal antibodies or so-called small molecules ) that are directed against biological and cytological peculiarities of cancer cells, for example:

- Inhibition of blood vessel growth (cancerous tissue attracts blood vessels to grow in the direction of the cancerous tissue to supply it.)

- Anti- hormone therapy ("hormone therapy"), e.g. B. Testosterone withdrawal in prostate cancer

- Cancer immunotherapy (several procedures based on the immune system. For example, monoclonal antibodies , radioimmunotherapy , immunotoxins , Bacillus Calmette-Guérin or cytokines )

- Hyperthermia , for example with microwaves (heating of the affected tissue)

- Electrochemotherapy

- There are experiments on cancer treatment with oncolytic viruses or cancer vaccines .

Palliative medical treatments to promote quality of life (for types of cancer with no chance of recovery)

- Administration of pain medication

- Improvement of general well-being through pain treatment

- adequate nutrition

- Inhibition of bone loss

- Increase in blood production in the bone marrow

- symptomatic treatments such as dilatation of stenoses by bougienage or insertion of stents

- Physiotherapy (special respiratory therapy for lung cancer)

- palliative chemotherapy

Evaluation of the treatment result

Even if a complete cure often cannot be achieved, it must be taken into account that in a 75-year-old cancer patient a lifetime extension of 1 or 2 years can be regarded as a very good result (older cancer patients often die from something other than the Cancer), while a 45-year-old breast cancer patient only has 10 years of relapse-free status as “very good” because she actually has a significantly higher life expectancy .

Alternative treatments

The unsatisfactory cure rate for certain tumor diseases and the side effects of the established treatment methods often trigger fears and despair in those affected and their relatives. Under certain circumstances, this leads to a turn to unconventional types of treatment , which in many cases lack evidence of effectiveness and the justification for which usually does not stand up to scientific examination. Some of them are rejected as “ miraculous cures ”, while others are accepted as complementary therapy methods by evidence-based medicine . The abandonment of conventional procedures in favor of exclusively alternative therapy increases the risk of death considerably.

Alternative treatments include mistletoe therapy and the use of amygdalin , among others . Both are controversial. A scientifically tenable proof of the effectiveness has not been provided for mistletoe therapy or amygdalin.

Completely independently of this, a number of successful cytostatics, such as vincristine or paclitaxel , were originally found in plants. However, these cytostatics are highly pure and highly concentrated and therefore cannot be compared with "herbal tea" or something similar.

Dietary supplements are not medicines . In contrast to drugs, which have been required to prove their effectiveness in Germany since 1978 in accordance with the Drugs Act before approval can take place, this has not been the case with food supplements so far. They are subject to the Food, Consumer Goods and Feed Code . Proof of effectiveness must be in accordance with Regulation EC No. 1924/2006 on nutrition and health claims for foodstuffs have recently been provided if the corresponding food supplement is to be advertised with a statement. From a legal point of view, such products may not otherwise be marketed with statements related to illness. However, this is often undermined, particularly in the case of products advertised on the Internet.

Many people consider the use of vitamin preparations to be a miracle cure against aging of the skin and cancer. Researchers keep finding that this is a mistake. At the University of Gothenburg, researcher Martin Bergö carried out studies on mice. After adding substances that contain antioxidants such as ACE vitamins, multivitamins, selenium or other supplements, the metastasis rate doubled. Tests on human skin and lung cancer cells gave almost the same results. The researchers advise cancer patients to eat a healthy diet.

For example, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warns on its website against the purchase of 125 products from 23 manufacturers. Some manufacturers, who advertised with slogans such as “cures all types of cancer” or “works against cancer cells and protects healthy tissue”, have been warned. The products listed include “ medicinal mushrooms ” such as the glossy Lackporling (Reishi) or the Brazilian Almond Gerling ( Agaricus subrufescens ), herbal teas such as Essiac, vitamins and minerals.

At the international level, the Concerted Action for Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Cancer (CAM-Cancer) organization deals with the methods and resources of alternative / complementary medicine for the treatment of cancer and publishes specialist information on its website.

The alleged cancer therapies whose effectiveness has been refuted or are controversial due to a lack of valid scientific and medical knowledge include:

- Germanic New Medicine : Conflicts should be the cause of cancer (and other diseases), "conflict resolution" should cure cancer "naturally". This is a contradiction to the recognized medical knowledge.

- beam ray device : The cancer virus allegedly discovered by Royal Rife could not be detected, nor was the effectiveness of its beam ray device for cancer therapy.

- Therapeutic Touch : That this variant of the laying on of hands can cure cancer or other diseases cannot be proven by scientific studies.

- Holistic therapy according to Issels : A scientific proof of effectiveness of this form of therapy, which is based on the rehabilitation of tooth fillings and the use of various supposedly "immune-stimulating" agents, could not be presented up to now.

- Therapy according to Di Bella : The use of the hormones somatostatin and melatonin in the context of this therapy is ineffective or only of low effectiveness, according to an investigation commission set up by the Italian government.

- Amygdalin : There is no scientifically sound evidence of the therapeutic effectiveness of this substance, which is also incorrectly referred to as vitamin B17 .

- Shark cartilage : The one effect of shark cartilage in human cancers could not be proven by independent scientific studies.

- Bis (carboxyethyl) germanium sesquioxide (Ge-132) : The responsible authorities expressly warn against consumption of Ge-132 , as serious damage to health and death cannot be ruled out.

- Gerson Therapy : This diet, which is primarily based on avoiding certain foods, has no evidence of its effectiveness against cancer, according to a commission from the New York County Medical Society.

- Alkaline diet : The German Nutrition Society states that: "An excess of base diet [...] does not bring any verifiable health benefits."

- Breuss cancer diet : The effectiveness of the 42-day juice cure, in which chemotherapeutic agents and radiation should not be used, could not be proven; According to the Austrian Cancer Society: "[T] he absurd diet does not produce any healing results, but accelerates death".

- Oil-protein diet according to Budwig : This diet, which emphasizes quark and cottage cheese in addition to linseed and cold-pressed linseed oil, is not able to cure cancer, according to oncologists and nutritionists.

- Macrobiotics : According to the German Nutrition Society: "Above all, the claim [of this form of nutrition] to cure [to] all diseases, including cancer."

rehabilitation

Rehabilitation is useful in order to keep additional health impairments as low as possible, to restore the ability to work and to maintain the quality of life despite the illness. The German Cancer Aid and the German Cancer Society have stepped up their joint information work to inform those affected about rehabilitation. The number of applications for oncological rehabilitation has been falling since 2011. Around 40 percent of cancer patients in Germany are of working age. Nevertheless, many cancer patients do not apply for benefits that restore or stabilize their ability to work, although that would make perfect sense.

There are different reasons for the increasingly frequent non-use of rehabilitation services: Just a few years ago, after completing the acute treatment of a cancer patient, medical rehabilitation measures followed more or less “automatically”. Numerous inpatient acute treatments are continued on an outpatient basis. A follow-up rehabilitation rehabilitation (AHB), which follows the inpatient treatment immediately or after 14 days at the latest, could therefore often no longer be initiated directly and easily by the clinic social service. Those affected must therefore submit a corresponding application to the responsible rehabilitation agency themselves. It is known from studies on this topic that information deficits both with regard to the access routes and the benefits of a measure are responsible for the declining use of REHA. The German Cancer Aid tries to motivate cancer patients and their families to carry out rehabilitation by intensifying information work. The Cancer Aid has supplemented its information series The Blue Advice .

Treatment support

Studies show that even with cancer, patients themselves and those around them can contribute to the success of the treatment. How well informed patients are about their illness plays a role here ( health literacy ). According to a study by the Mayo Clinik, however, many cancer patients feel poorly informed about their illness, diagnostic methods, proper nutrition, stress management and how to deal with side effects. The patient empowerment should counteract this fact.

If patients take on an active role and look for ways to support the therapy and improve their quality of life, this is called self-empowerment . Well-informed patients can be actively involved in medical decisions, which improves the chances of successful treatment. An intact social environment in cancer patients can also contribute to the success of treatment to a certain extent. It helps to improve the quality of life and better cope with the disease.

Cancer prevention

early detection

For most cancers, early detection increases survival rates, such as colon cancer, cervical cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer. Early detection has only been ineffective for a few types of cancer - for example lung cancer . If left untreated, the malignant tumor grows until the organ or body becomes inoperable. Since the risk of developing cancer varies for a population, the individual cancer risk is regularly re-determined for each generation and each country. The individual risk of cancer depends, for example

- of emerging environmental pollutants or environmental toxins, the use of reduced or banned is

- from the way of life (eg. as eating habits, getting enough exercise, willingness to protect from direct sunlight)

- sexual behavior (contamination of a population with potentially carcinogenic viruses)

The sooner a cancer is detected, the better the chances of recovery. If they are detected earlier, more cancers can be cured, and they are easier to cure with minor surgery, less effort, or minor side effects. Not every early diagnosis only offers advantages (see also screening ):

- It is also false-positive findings are made.

- The screening test can have risks and / or side effects. For example, it is used in 2 to 4 of 1000 colonoscopies to a bowel perforation .

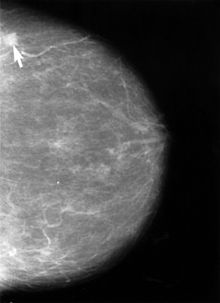

For men, for example, regular examinations of the physician to blood in the stool and the scanning of the prostate (see prostate cancer ) done for women a cervical smear (systematic Screening for cervical cancer ) and mammography - screening tests (from 50 years) made. Genetic examinations can also be used to detect certain types of cancer at an early stage. However, this method is rarely used in practice because the concentrations of biomarkers of the tumor are initially low and closer to the detection limit of the examination methods , which can lead to false-negative results.

Many cancers are diagnosed when patients see a doctor based on changes they have seen. Typical signs of cancer are:

- unusual swelling; Wounds that do not heal; Change in the shape, size, or color of any skin mark or abnormal bleeding

- chronic cough or persistent hoarseness,

- a change in bowel movements or urination

- an inexplicable weight loss,

- palpable changes when palpating the breasts.

Every self-examination is fraught with a great risk of error. Nodules in the breast can be harmless; on the other hand, laypersons can only feel malignant breast tumors when they have reached a certain size (and thus a higher tumor stage) - and there is a high probability that they have already metastasized.

The Federal Ministry of Health wrote in 2011:

“In the area of cancer screening, many doctors offer services that those with statutory health insurance have to pay for themselves (e.g. certain ultrasound examinations or blood tests). The statutory health insurances do not cover the costs for these so-called individual health services ( IGeL ) because they usually do not have any sufficiently documented medical benefits. If IGeL are recommended to you during a visit to the practice, ask for time to think about it. Insist on a written contract that contains the exact scope of the IGeL and the associated costs. You don't have to pay an invoice without a written agreement. You can obtain independent information on IGeL from the Medical Service of the Central Association of Health Insurance Funds (MDS), the independent patient advice service Germany (UPD) and the German Cancer Aid "

See also

literature

- H.-J. Schmoll, K. Höffken, K. Possinger (Eds.): Compendium of internal oncology. 3 volumes. 4th edition. Springer, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-540-20657-4 . ( limited preview in Google Book search)

- Wolfgang U. Eckart (Ed.): 100 years of organized cancer research; 100 Years of Organized Cancer Research , Thieme, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-13-105661-4 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Siddhartha Mukherjee : The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer . Scribner, 2010, ISBN 978-1-4391-0795-9 . ( limited preview in Google book search) (German edition: The king of all diseases: Cancer - a biography . DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 2012, ISBN 978-3-8321-9644-8 )

- H. Stamatiadis-Smidt, Harald zur Hausen , Otmar Wiestler (eds.): Topic cancer. 3. Edition. Springer, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-540-25792-6 . ( limited preview in Google Book Search)

- Bruce N. Ames , Lois Swirsky Gold: Misconceptions about the links between pollution and the development of cancer . In: Angewandte Chemie . tape 102 , no. 11 , 1990, pp. 1233-1246 , doi : 10.1002 / anie.19901021106 .

- Robert A. Weinberg : The biology of cancer. 2nd Edition. Garland Science, New York 2014, ISBN 978-0-8153-4220-5 .

- F. Cabanne, Rémi Géraud-Marchant and Fernand Destaing: History of Cancer. In: Illustrated History of Medicine. (French original edition in eight volumes, edited by Albin Michel-Laffont-Tchou, Paris 1977–1980) German adaptation by Richard Toellner a . a., special edition in six volumes. Volume V, Salzburg 1986, pp. 2756-2787.

- D. Hanahan , RA Weinberg: Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. (PDF). In: Cell. Volume 144, Number 5, March 2011, pp. 646-674, doi: 10.1016 / j.cell.2011.02.013 . PMID 21376230 .

- D. Hanahan, RA Weinberg: The hallmarks of cancer. (PDF). In: Cell. Volume 100, Number 1, January 2000, pp. 57-70. PMID 10647931 .

Historical sources

- Johann Heinrich Jänisch: Treatise of the cancer and of the best kind of healing of the same . 2nd edition. St. Petersburg 1785, urn : nbn: de: hbz: 061: 2-29426 .

- Jacob Wolff: The theory of cancer from the oldest times to the present. Fischer, Jena 1914 ff.

- Ferdinand Sauerbruch : world problem of health: cancer. [Radio lecture] In: Ferdinand Sauerbruch, Hans Rudolf Berndorff : That was my life. Kindler & Schiermeyer, Bad Wörishofen 1951; cited: Licensed edition for Bertelsmann Lesering, Gütersloh 1956, pp. 329–344.

- Paul Obrecht: Clinical Cancerology. In: Ludwig Heilmeyer (ed.): Textbook of internal medicine. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg 1955; 2nd edition, ibid. 1961, pp. 352-375.

Web links

- German Cancer-research center

- Center for cancer registry data at the Robert Koch Institute

- Society of Epidemiological Cancer Registers in Germany V. (GEKID)

- NCI fact sheets. National Cancer Institute

Individual evidence

- ↑ ecancer.org

- ↑ Garyfallos Konstantinoudis, Dominic Schuhmacher, Roland A. Ammann, Tamara Diesch, Claudia E. Kuehni, Ben D. Spycher: Bayesian spatial modeling of childhood cancer incidence in Switzerland using exact point data: a nationwide study during 1985-2015. In: International Journal of Health Geographics. 19, 2020, doi : 10.1186 / s12942-020-00211-7 .

- ↑ Cancer in Germany 2013/2014 - frequencies and trends. A joint publication of the Robert Koch Institute and the Society of Epidemiological Cancer Registers in Germany e. V., 11th edition, 2017, accessed on November 20, 2018.

- ↑ Cancer statistics - Syöpärekisteri . In: Syöpärekisteri . ( cancerregistry.fi [accessed December 2, 2018]).

- ↑ A good 20 percent of all cancers can be traced back to infections. In: Doctors newspaper . October 8, 2008.

- ↑ krebsatlas.de: Infectious pathogens. ( Memento of July 31, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) November 6, 2007, accessed on February 27, 2010.

- ^ Paul Schweinzer, Miguel Portela: The parental co-immunization hypothesis: An observational competing risks analysis . In: Scientific Reports . tape 9 , no. 1 , February 21, 2019, ISSN 2045-2322 , p. 2493 , doi : 10.1038 / s41598-019-39124-2 ( nature.com [accessed March 6, 2019]).

- ↑ Miguel Portela, Paul Schweinzer: How do parenting, marital status and income affect the causes of death? In: University of Klagenfurt. February 21, 2019, accessed March 6, 2019 .

- ↑ Dinosaurs also suffered from cancer - Wissenschaft.de . In: Wissenschaft.de . October 22, 2003 ( Wissenschaft.de [accessed September 17, 2020]).

- ↑ M. Greaves: Cancer - the stowaway of evolution. Verlag Springer, 2002, ISBN 3-540-43669-3 , p. 9. ( limited preview in Google book search)

- ↑ M. Reitz: skin cancer in high cultures. In: A short cultural history of the skin. 2007, ISBN 978-3-7985-1757-8 , pp. 78-83.

- ↑ SA Hoption Cann et al .: Dr William Coley and tumor regression: a place in history or in the future. In: Postgraduate Medical Journal. 79, 2003, pp. 672-680. PMID 14707241 (Review)

- ↑ Johannes Steudel : Where does the name cancer come from? In: German Medical Weekly . Volume 78, 1953, p. 1574.

- ^ Felix Georg Brunner: Pathology and therapy of tumors in ancient medicine with Celsus and Galen. (= Zurich treatises on the history of medicine. New series. Volume 118). At the same time medical dissertation. Zurich 1977.

- ↑ Paul Obrecht: Clinical Cancerologie. 1961, pp. 352 and 358 f.

- ^ AG Knudson: Hereditary cancer, oncogenes, and antioncogenes. In: Cancer Res . Volume 45 (4), 1985, pp. 1437-1443. PMID 2983882 . online (PDF)

- ↑ Löffler / Petrides: Human biochemistry . 9th edition. Springer Verlage, 2014, ISBN 978-3-642-17971-6 , pp. 646 .

- ^ R. Liu, M. Kain, L. Wang: Inactivation of X-linked tumor suppressor genes in human cancer. In: Future Oncol. Volume 8 (4), 2012, pp. 463-481. PMID 22515449 .

- ↑ M. Burnet: Cancer; a biological approach. I. The processes of control. In: Br Med J. Volume 1 (5022), 1957, pp. 779-786. PMID 13404306 ; PMC 1973174 (free full text).

- ↑ D. Zimonjic et al .: Derivation of human tumor cells in vitro without widespread genomic instability. In: Cancer Res . 61, 2001, pp. 8838-8844. PMID 11751406

- ↑ P. Duesberg: The chaos in the chromosomes. In: Spectrum of Science . 10, 2007, pp. 55f.

- ↑ Alfred Böcking, Vera Zylka-Menhorn: Carcinogenesis: Are Tumors a New Species? In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt . tape 108 , no. 48 . Deutscher Ärzteverlag , December 2, 2011, p. A-2604 / B-2176 / C-2148 .

- ↑ D. Hanahan , RA Weinberg: The hallmarks of cancer . In: Cell . tape 100 , no. 1 , 2000, pp. 57-70 , PMID 10647931 .

- ↑ Jörg Blech : Saat des Evil . In: Der Spiegel . No. 24 , 2007 ( online ).

- ↑ Breast cancer: For the first time, active ingredient against tumor stem cells. In: aerzteblatt.de . August 14, 2009, archived from the original on December 26, 2014 ; Retrieved December 26, 2014 .

- ↑ rme / aerzteblatt.de: New references to cancer stem cells. In: aerzteblatt.de . August 2, 2012, accessed December 26, 2014 .

- ↑ Experiments on mice: cancer stem cells could fuel tumor growth. In: Spiegel Online . August 2, 2012, accessed December 26, 2014 .

- ↑ Gerlinde Felix: Wolves in Sheep's Clothing. In: Stuttgarter Zeitung . August 2, 2012, accessed August 3, 2012.

- ↑ Katherine Bourzac: How a Tumor Is Like an Embryo - MIT Technology Review. In: technologyreview.com. November 6, 2007, accessed December 26, 2014 .

- ^ P. Anand et al .: Cancer is a preventable disease that requires major lifestyle changes. In: Pharm. Res. 25 (9), September 2008, pp. 2097-2116. doi: 10.1007 / s11095-008-9661-9 , PMC 2515569 (free full text). PMID 18626751 .

- ↑ AJ Einstein et al .: Estimating risk of cancer associated with radiation exposure from 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography. In: JAMA 298, 2007, pp. 317-323. PMID 17635892

- ^ R. Smith-Bindman et al .: Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer. In: Archives of internal medicine . Volume 169, Number 22, December 2009, pp. 2078-2086, ISSN 1538-3679 . doi: 10.1001 / archinternmed.2009.427 . PMID 20008690 .

- ↑ A. Berrington de González, M. Mahesh, KP Kim, M. Bhargavan, R. Lewis, F. Mettler, C. Land: Projected cancer risks from computed tomographic scans performed in the United States in 2007. In: Archives of internal medicine. Volume 169, Number 22, December 2009, pp. 2071-2077, ISSN 1538-3679 . doi: 10.1001 / archinternmed.2009.440 . PMID 20008689 .

- ↑ C. Zimmer: Cancer - a side effect of evolution? In: Spectrum of Science. 9, 2007, pp. 80-88.

- ↑ Cancer warning over stem cell therapies. In: New Scientist. January 7, 2007.

- ↑ CM Vajdic, MT van Leeuwen: Cancer incidence and risk factors after solid organ transplant. In: Int J Cancer . 125, 2009, pp. 1747-1754. PMID 19444916

- ↑ Blood markers for the risk of cancer after organ transplantation. In: Doctors newspaper. February 22, 2010.

- ↑ OM Martinez, FR de Gruijl: Molecular and immunologic mechanisms of cancer pathogenesis in solid organ transplant recipients. In: American journal of transplantation. Volume 8, Number 11, November 2008, pp. 2205-2211, ISSN 1600-6143 . doi: 10.1111 / j.1600-6143.2008.02368.x . PMID 18801025 . (Review).

- ↑ GP Dunn et al .: Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. In: Nat Immunol . 3, 2002, pp. 991-998. PMID 12407406 (Review)

- ↑ GC Kabat, et al .: Adult stature and risk of cancer at different anatomic sites in a cohort of postmenopausal women. In: Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. Volume 22, Number 8, August 2013, pp. 1353-1363, ISSN 1538-7755 . doi: 10.1158 / 1055-9965.EPI-13-0305 . PMID 23887996 .

- ^ L. Zuccolo et al .: Height and prostate cancer risk: a large nested case-control study (ProtecT) and meta-analysis. In: Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. Volume 17, Number 9, September 2008, pp. 2325-2336, ISSN 1055-9965 . doi: 10.1158 / 1055-9965.EPI-08-0342 . PMID 18768501 . PMC 2566735 (free full text).

- ↑ RB Walter et al .: Height as an explanatory factor for sex differences in human cancer. In: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Volume 105, Number 12, June 2013, pp. 860-868, ISSN 1460-2105 . doi: 10.1093 / jnci / djt102 . PMID 23708052 . PMC 3687370 (free full text).

- ↑ C. Murgia et al .: Clonal Origin and Evolution of a Transmissible Cancer. In: Cell. 126, 2006, pp. 477-487. PMID 16901782 , PMC 2593932 (free full text)

- ↑ GK Reeves et al .: Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. In: BMJ . 335, 2007, p. 1134. PMID 17986716

- ↑ EE Calle: Obesity and cancer. In: BMJ. 335, 2007, pp. 1107-1108. PMID 17986715

- ↑ Xavier Michelet et al .: Metabolic reprogramming of natural killer cells in obesity limits antitumor responses. In: Nature Immunology. 19, 2018, p. 1330, doi : 10.1038 / s41590-018-0251-7 .

- ^ Tatjana Meier, Michael Noll-Hussong: The role of stress axes in cancer incidence and proliferation . In: Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. Volume 64 , no. 9-10 , 2014, pp. 341-344 .

- ↑ SO Dalton et al .: Depression and cancer risk: A register-based study of patients hospitalized with affective disorders, Denmark, 1969-1993. In: American Journal of Epidemiology. 155, 2002, pp. 1088-1095. PMID 12048222

- ↑ IR Schapiro et al .: Psychic vulnerability and the associated risk for cancer. In: Cancer. 94, 2002, pp. 3299-3306. PMID 12115364

- ^ Matthew Walker: Why We Sleep: The New Science of Sleep and Dreams , Penguin Verlag, January 4, 2018

- ↑ Vincent J. Felitti et al .: Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults - The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study In: American Journal of Preventive Medicine. Volume 14, ISSUE 4, P245-258, May 01, 1998

- ↑ After M. Bahadir, H. Parlar, Daniela Angerhöfer, Michael Spiteller: Springer Umweltlexikon. Berlin / Heidelberg 2000, p. 248. ( limited preview in Google book search)

- ↑ a b c U.-N. Riede, M. Werner, H.-E. Schäfer (Ed.): General and special pathology. Thieme, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-13-683305-8 , pp. 382-384.

- ↑ Berthold Jany, Tobias Welte: Pleural effusion in adults - causes, diagnosis and therapy. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. Volume 116, Issue 21, (May) 2019, pp. 377-385.

- ^ Federal health reporting: Cancer. ( Memento of November 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- ↑ Bicky Thapa, Kamleshun Ramphul: Paraneoplastic Syndromes . In: StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL) 2019, PMID 29939667 ( nih.gov [accessed March 12, 2019]).

- ↑ a b A. Jemal et al .: Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. In: Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention . Volume 19, Number 8, August 2010, pp. 1893-1907. doi: 10.1158 / 1055-9965.EPI-10-0437 . PMID 20647400 . (Review).

- ^ Cancer in Germany.

- ↑ Swiss Cancer Report 2015 ( Memento from March 25, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ IARC: Cancer Fact Sheets

- ↑ Press release from FSO, NICER and SKKR ( memento of March 25, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) of March 21, 2016.

- ^ Hanno Charisius : Victory in Numbers. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung. January 19, 2007, p. 18.

- ^ Message to the press - 2876th Employment, Social Policy, Health and Consumer Affairs Council. (PDF; 328 kB) June 9, 2008, accessed on July 21, 2008 . P. 21. (PDF)

- ↑ 20,000 deaths from cancer every day. In: Doctors newspaper. December 18, 2007.

- ↑ National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: NIOSH Safety and Health Topic: Occupational Cancer. May 4, 2009, Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ↑ a b Lajos Schöne: Four out of five children with cancer are cured today. In: Doctors newspaper. online, January 14, 2010.

- ↑ Geography of cancer diseases in children in Switzerland studied. In: University of Bern . May 14, 2020, accessed May 16, 2020 .

- ↑ Cancer survival rates increased worldwide with large international differences. In: Ärzteblatt. January 31, 2018, accessed April 8, 2018 .

- ↑ OECD (Ed.): Health at a Glance 2019 . 2019, ISBN 978-92-64-80766-2 , pp. 138-143 , doi : 10.1787 / 19991312 .

- ↑ S. Korea ranks among top OECD member countries in treatment of cancer: data. In: The Korea Herald . Yonhap , November 17, 2019, accessed November 30, 2019 .

- ^ Cancer in Germany. 2015, p. 20.

- ↑ Quoted from: A quarter of all cancers go undetected. In: FZ Med News. October 18, 2007; according to SM Said et al .: How reliable are our cancer statistics? In: DMW. 132, 2007, pp. 2067-2070.

- ↑ a b Robert Koch Institute (Ed.): Cancer in Germany 2005/2006 - Frequencies and Trends. ( Memento of November 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) 7th edition, 2010, p. 19.

- ↑ skin cancer. Rethink! Actively preventing cancer. In: krebshilfe.de. German Cancer Aid, archived from the original on April 14, 2011 ; Retrieved April 14, 2011 .

- ^ Cancer in Germany 2007/2008. ( Memento of April 24, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) 8th edition. Robert Koch Institute (ed.) And the Society of Epidemiological Cancer Registers in Germany V. (Ed.) Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-89606-214-7 .

- ↑ W. Hiddemann , C. Bartram (Ed.): Onkologie. 2 volumes. Edition 2. Verlag Springer, 2009, ISBN 978-3-540-79724-1 . ( limited preview in Google Book search)

- ↑ H. Matthys, W. Seeger (Ed.): Clinical Pneumology. Verlag Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-3-540-37682-8 , p. 188. ( limited preview in Google book search)

- ↑ Substances that cause lung cancer . In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt . tape 93 , no. 5 . Deutscher Ärzteverlag , February 2, 1996, p. A-247 / B-195 / C-183 .

- ↑ H. Feldmann: The opinion of the ear, nose and throat doctor. Georg Thieme Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-13-542306-9 , p. 294. ( limited preview in Google book search)

- ↑ https://www.krebshilfe.de/informieren/ueber-uns/geschaeftsbericht/ , accessed on August 8, 2019

- ↑ Robert Koch Institute and Society of Epidemiological Cancer Registers in Germany (GEKID 2019), accessed on August 7, 2019

- ↑ Skyler B. Johnson et al .: Use of Alternative Medicine for Cancer and Its Impact on Survival . In: JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute . tape 110 , no. 1 , August 10, 2017, doi : 10.1093 / jnci / djx145 .

- ↑ Norbert Aust: Study reveals: With alternative medicine, many cancer patients die earlier than necessary! ( netzwerk-homoeopathie.eu [accessed October 2, 2018]).

- ↑ Skyler B. Johnson et al .: Complementary Medicine, Refusal of Conventional Cancer Therapy, and Survival Among Patients With Curable Cancers . In: JAMA Oncology . tape 4 , no. 10 , October 1, 2018, p. 1375–1381 , doi : 10.1001 / jamaoncol.2018.2487 .

- ↑ Mistletoe in cancer therapy: standard or alternative method? Cancer information service of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, October 23, 2012. Last accessed on September 4, 2014.

- ↑ CG Moertel et al .: A clinical trial of amygdalin (Laetrile) in the treatment of human cancer. In: NEJM. 306, 1982, pp. 201-206. PMID 7033783

- ^ S. Milazzo et al .: Laetrile for cancer: a systematic review of the clinical evidence. In: Supportive Care in Cancer. 15, 2007, pp. 583-595. doi: 10.1007 / s00520-006-0168-9 . PMID 17106659

- ^ Federal Institute for Risk Assessment: Health Assessment of Food Supplements. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ↑ Cancer Information Service of the German Cancer Research Center (dkfz). Vitamins and trace elements: (Not) a plus for health? Report dated January 9, 2015. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- ↑ When miracle pills hurt. In: Focus. Issue 43/15, October 17, 2015, p. 96.

- ↑ FDA warns of fraud with alleged cancer miracle drugs. In: Online newspaper Mensch & Krebs. July 11, 2008, according to a press release from the DKFZ.

- ^ Concerted Action for Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Cancer: CAM Summaries. Summaries of various methods and resources in preventive, therapeutic and palliative alternative / complementary medicine (English), accessed on November 2, 2012.

- ↑ Jutta Hübner : Diagnosis of cancer ... which helps me now . Schattauer Verlag, 2011, p. 77.

- ^ ACS: American Cancer Society Complete Guide to Complementary and Alternative Cancer Therapies. 2nd Edition. 2009, ISBN 978-0-944235-71-3 , pp. 248-251.

- ^ S. Milazzo et al .: Laetrile for cancer: a systematic review of the clinical evidence. In: Supportive Care in Cancer. 15 (6), 2006, pp. 583-595; doi: 10.1007 / s00520-006-0168-9 . PMID 17106659 .

- ↑ Shark Info: The brutal business with shark cartilage and cancer.

- ↑ Federal Institute for Risk Assessment : BgVV warns against the consumption of 'Germanium-132 capsules' from the Austrian company Ökopharm. September 8, 2000.

- ↑ Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety (AGES) warns: Product contains harmful concentration of germanium. ( Memento of July 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) October 17, 2008.

- ↑ Press release from Krebshilfe dated June 6, 2014

- ^ Rehabilitation report 2013 of the German Pension Insurance (DRV), January 1, 2014.

- ^ Robert Koch Institute Berlin, survey from 2010.

- ↑ DVSG Chairman Ulrich Kurlemann, German Association for Social Work, June 6th, 2014.

- ^ Leslie Padrnos et al .: Living with Cancer: an Educational Intervention in Cancer Patients Can Improve Patient-Reported Knowledge Deficit . In: Journal of Cancer Education . October 11, 2016, ISSN 0885-8195 , p. 1-7 , doi : 10.1007 / s13187-016-1123-1 ( springer.com [accessed March 2, 2017]).

- ^ Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Literacy: Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion . National Academies Press (US), Washington (DC) 2004, ISBN 0-309-09117-9 , PMID 25009856 ( nih.gov [accessed March 2, 2017]).

- ^ SC Thigpen, SA Geraci: Cancer Screening 2016. In: The American journal of the medical sciences. Volume 352, Number 5, November 2016, pp. 493-501, doi: 10.1016 / j.amjms.2016.06.001 . PMID 27865297 .

- ^ J. Zhang et al .: Effectiveness of Screening Modalities in Colorectal Cancer: A Network Meta-Analysis. In: Clinical colorectal cancer. [electronic publication before printing] April 2017, doi: 10.1016 / j.clcc.2017.03.018 . PMID 28687458 .

- ↑ GF Sawaya, MJ Huchko: Cervical Cancer Screening. In: The Medical clinics of North America. Volume 101, Number 4, July 2017, pp. 743-753, doi: 10.1016 / j.mcna.2017.03.006 . PMID 28577624 .

- ^ C. van den Ende et al .: Benefits and harms of breast cancer screening with mammography in women aged 40-49 years: A systematic review. In: International journal of cancer. [electronic publication before going to press] May 2017, doi: 10.1002 / ijc.30794 . PMID 28542784 .

- ^ AK Rahal, RG Badgett, RM Hoffman: Screening Coverage Needed to Reduce Mortality from Prostate Cancer: A Living Systematic Review. In: PloS one. Volume 11, number 4, 2016, p. E0153417, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0153417 . PMID 27070904 , PMC 4829241 (free full text).