Transverse church

A transverse church is a form of church building in which either (with the usual east- facing longitudinal floor plan ) the transept is considerably larger than the nave (the latter is almost completely omitted) or in which the interior furnishings (stalls, multi-sided galleries, sometimes also the altar) the pulpit faces on one long side - i.e. transversely to the spatial longitudinal orientation.

With the transverse church, the only purely Protestant sacred structure emerged. As with the Reformation Central Church, which modified a Catholic-Baroque building principle by centralizing the altar, it was understood as an architectural implementation of the principle of the “ priesthood of all believers .” Choirs and ships were thus no longer regarded as a constitutive (fundamental) part of the church building. It was not until the Baroque period that transverse churches were built in large numbers.

history

With the Querkirche, the only purely Protestant sacred structure emerged, and not just in the 18th century, as some otherwise excellent specialist literature and even in the Reformation year 2017 the German Foundation for Monument Protection believe. It developed from the late medieval long church without seats, in southern German imperial cities above all from the churches in which preachers were specially employed for preaching services even before the Reformation , and from the Dominican preachers' church, which is usually in the imperial city , in which the pulpit is usually on one side Central nave pillar was attached. The congregation had gathered in front of this during the sermon, but otherwise focused on the consecrated altar in the east choir for the mass service . With the Reformation, this place of the Sunday sacrifice in a sacred space reserved for the clergy , the choir, separated from the nave for the lay people , was no longer an option, but it was often given a new meaning as a free-standing altar table : the Lord's table around which the congregation is for the priestly service of all baptized , gathered for the Lord's Supper. Martin Luther's understanding of worship - every place and room is right for the proclamation, prayer and Lord's Supper - that he had outlined in his sermon for the inauguration of the Torgau Palace Chapel on October 5, 1544, corresponded to the alignment of the pews and the installation of often multi-sided ones Galleries with sitting, listening and viewing directions primarily to the pulpit, which gave the congregation a more direct acoustic and visual access to the starting point of the preached gospel. In addition to the western gallery, which is also traditionally widespread in the Catholic area, there are often two-sided angled, three-sided U-shaped horseshoe galleries, as well as four-sided round galleries that surround the entire nave. For acoustic reasons, the pulpit was usually located on one long side of the church interior. With this functional rotation to the south, north, and sometimes even to the west, the east no longer played a role, which can also be seen in many post-Reformation extensions and reconstructions of traditional longitudinal churches as well as in nave additions to Gothic choirs or Romanesque choir towers. In the case of small village churches, it could make sense to move the previous altar from the narrow choir into the newly designed sermon hall, because due to lack of space, the congregation could only meet here for the Lord's Supper. For example, old choir rooms were sometimes almost inoperable if they were not suitable for the installation of special stalls, for the installation of epitaphs or an organ. The Protestant church building and its master builders had to find - also structural - solutions for wide church rooms that were as pillar-less as possible, which brought the listening community in a more semicircular arrangement to the “sermon chair” (the pulpit ).

Luther already speaks of the fact that the post-Reformation building or conversion of castle chapels into transverse churches is not an exclusively internal castle measure benefiting local, regional or state rule, but rather, in the spirit of the Reformation, "the church" is seen as a community and local parish encompassing a class of his Torgau sermon. - The other church building measures in castles that followed up to 80 years later also open the stately worship space for the non-class congregation: the chateau chapel becomes the parish church. There were, however, class differences when attending church services: the architecturally and artistically prominent gallery, usually directly accessible from the stately private apartments, was used by the rulers and their entourage, on the unadorned ground floor the castle staff sat or stood and "who otherwise want to enter" ( Luther).

Querkirchen as new buildings were built after the Torgau Palace Chapel, primarily in southern Germany. In the Duchy of Württemberg and its neighboring and partly related counties and later principalities of Hohenlohe , Brandenburg-Ansbach and Brandenburg-Bayreuth , this was due to the independent theological and liturgical profile between Lutheranism and Calvinism and the committed church building efforts of the sovereigns and their builders: " Unlike in Wittenberg, the basic liturgical decision of the Reformation in Württemberg was not based on the medieval tradition of the Roman mass, but on those preaching services that were widespread in the cities of south-west Germany [...]. ”Therefore, preaching hall churches were established early on - deliberately without a choir room of the sacraments - regarded as exemplary for evangelical worship services. A separation of spiritual and secular church space was no longer necessary after the Reformation.

The transverse hall, which is geared towards the proclamation of the Word and less towards the altar and communion table, initially had its focus in Württemberg across Germany with a focus on Franconia, even as far as Königsberg , but was not realized everywhere in Württemberg through new buildings. Existing building stock with limited possibilities for complete redesign in the sense of the sermon hall and transverse hall concept as well as a lack of financial means led to locally different compromise solutions: Very often existing churches were not only widened in the nave on one or both sides and provided with galleries there, but even wider or narrow choirs, and there, too, the stalls facing the pulpit. The position of the altar was then based on the space available for the community mealtimes at the Lord's table . Many of these subsequent conversions and installations were removed during renovations in the 20th century and the church interior was aligned lengthways again, but were characteristic of Protestant churches for centuries. The patronage local and regional nobility, when expanding or building a new church, sometimes oriented themselves more towards their needs for representation and burial than according to Reformation theological principles: in the traditional longitudinal orientation of a church, the choir often became a space for epitaphs, as burial was for the Protestant nobility or the memory of the dead in monasteries was lost. The consciously Protestant character of the church was then emphasized in a different way: with Reformation altarpieces (for example the Lord's Supper "in both forms" ) and other features.

Transverse churches were also built in the Protestant territories of the Holy Roman Empire in Franconia (from 1690), in Baden (from 1612) and in the Electoral Palatinate , in Hesse (from 1607) and in the Reformed Calvinist countries of Switzerland (from 1667) and Netherlands (from 1620), plus the very simply designed churches of the religious refugees Huguenots and Waldensians - mostly without pictures and cross - in some German areas directly after the Edict of Fontainebleau of 1685 and in Württemberg from 1721. In France , however, it gave way shortly after During the Reformation, Huguenot meeting rooms, often as a round and wooden structure and as a lecture hall modeled on the theater, occasionally also built horizontally, mostly quickly destroyed in the more than 100 years of persecution and, in contrast to the Catholic "église", always called "temples". "The influence of the Huguenots on the development of the transverse churches in the empire (...) must be assessed as extremely small." The Evangelical Reformed Huguenot Church Erlangen in the Franconian domain of the Brandenburg princes and margraves, built between 1686 and 1693, is the oldest church in the Huguenots outside France. This Calvinist- reformed construction after the end of the Thirty Years War cannot have influenced the early building of the transverse church in Württemberg, as is sometimes assumed, and the first wave of Calvinist religious refugees from the Netherlands to the Electoral Palatinate, which had converted to Calvinism , did not even bring about in the late 16th century there, let alone Wuerttemberg, so early a church building according to Reformed ideas.

In the Reformed church building in Switzerland , the transverse church was a popular concept , especially in the late baroque and classicism . The reasons are to be found in the fact that the Reformed theology of Huldrych Zwingli and Jean Calvin provides for a radical renunciation of images and altars, which goes far beyond the Lutheran ideals. In the search for an ideal spatial concept, the transverse church, which allows a view of the pulpit as the center of the Reformed sermon service, appeared optimal. The ground plan shapes are varied and range from oval churches to rectangular buildings to churches with a cross plan. The U-shaped galleries , which are best shown to advantage in the churches of Wädenswil and Horgen , the largest and most important transverse churches in Switzerland, are also typical of the Reformed church building .

After 1815, Protestant sacred architecture was again oriented more towards medieval concepts. The Eisenach regulation of 1861 recommended the Gothic canon of forms for church building, in which the sacrament (the altar), but not the sermon (the pulpit), is the focus. This concept met with resistance from liberal Lutherans and Reformed people and was replaced by the Wiesbaden program in 1891. Many church buildings in the Wiesbaden program, as well as modern and postmodern, are designed as central buildings and often come close to the concept of the transverse church.

A few Catholic churches were also designed as transverse churches - albeit for specific practical needs. The best- known example of this is Gianlorenzo Bernini's Church of Sant'Andrea al Quirinale in Rome .

Construction engineering

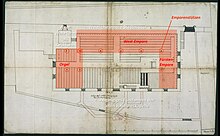

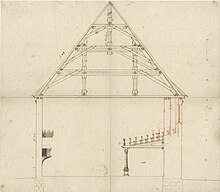

For practical reasons, it was recommended that the post-Reformation church should encompass the entire congregation as wide as possible with a pillar-free ceiling, good visibility and acoustics between the seats and the pulpit. From a nave width of 8-10 meters with conventional roof structures, this was no longer possible for structural reasons. It can be assumed that Elias Gunzenhäuser's pillarless, self- supporting roof structure, which is known in professional circles such as the royal courts, was further developed in the New Lusthaus , which was completed in Stuttgart in 1593 . In the town church Waldenbuch and for the large ballroom of the Renaissance castle Weikersheim Gunzenhäuser found appropriate solutions, and the architect Heinrich Schickhardt created with his staff for the City Church Göppingen 1618-1619 a Bautechnisches masterpiece of carpentry skills: a combination of so-called lying chairs , explosives and hanging trusses over three or four lofts, which had to be able to withstand high loads at the same time to accommodate the payload (fruit chute, grain floor). Simpler variants had already emerged before and then later as the only usable roof and ceiling structures for transverse churches. The Reformation's new form of worship led to a structural innovation. The liturgy challenged construction technology - or, to use the Bauhaus principle of the 20th century, form follows function , since the architectural is subordinate to the task at hand. The reclining chair, for large cantilevered spans combined with trusses and hanging structures, developed into the standard solution for roof structures in southern German churches in the late Renaissance and Baroque periods, so that gradually almost every larger church roof made use of these structural elements in the 17th and 18th centuries. Further north in Germany and also in other European countries, this innovation apparently hardly spread, to which the long timber competition for shipbuilding in coastal and river regions also contributed. The few larger Renaissance and transverse churches without a flat ceiling from the Netherlands to Scandinavia had supporting wall elements for their large vaults with cross, oval, round or double-rounded floor plans.

An interesting variant of the hanging structure was often used in Switzerland , especially by the bridge construction engineer Hans Ulrich Grubenmann , in the 18th century in church construction: both longitudinal and transverse churches were given a roof structure over the length of the room similar to a wide-span wooden bridge : with very long rafter trusses, stabilizing cross trusses and hip trusses as well as hanging pillars to support the flat ceiling. In other countries this construction does not seem to have been realized.

Examples of transverse churches

Germany

- 1503 Wittenberg Castle Church , Saxony (-Anhalt), late Gothic; 1507–1817 university church, Protestant since 1525; Martin Luther's place of work

- 1510 Ulm Minster , Württemberg, 14.-16. Century, largest Protestant church in Germany; Protestant since 1530; Although architecturally a classic Gothic basilica with longitudinal orientation, interior with pulpit Built in 1510 and with nachreformatorischer bench equipment subsequently applied as a cross church - like many other rich urban preacher churches also

- 1544 Evangelical Castle Church Torgau , Saxony; Renaissance

- 1553 Castle Chapel Dresden , Saxony; Late Gothic and Renaissance; Profaned in 1737, destroyed in the war in 1945, rebuilt as a concert and event space from 1985–2013

- 1562 Evangelical Castle Church in Stuttgart's Old Castle , Württemberg; Renaissance; Ducal building contract (builders Aberlin Tretsch and Blasius Berwart ), the oldest transverse church in Württemberg

- 1563 Evangelical Lutheran Castle Church in Schwerin , Mecklenburg; Renaissance, neo-Gothic choir

- 1574 Evangelical Laurentius Church in Oberderdingen in the Amthof (Oberderdingen) , Württemberg; Renaissance; ducal building contract

- 1575 Evangelical Castle Chapel in Plassenburg ob Kulmbach , Upper Franconia; Renaissance; Wuerttemberg-ducal event (advisory builders: Aberlin Tretsch and Blasius Berwart )

- 1577 Castle Church in Stettin , Pomerania; Renaissance; profane

- 1578 Evangelical Agidius Church in Brettach , Württemberg

- 1584 Evangelical St. Andrew's Church in Schlat , Württemberg

- End of the 16th century:

- Evangelical Church of St. Gereon and Margaretha Aichwald-Aichschieß , Württemberg

- Evangelical Martinskirche Calw- Altburg , Württemberg

- Evangelical Georgskirche Bad Teinach-Zavelstein , Württemberg

- Evangelical Stephanuskirche Neuweiler , Württemberg

- 1586 Evangelical Lutheran parish church of St. Mang in Kempten (Allgäu) , Bavarian Swabia; Renaissance and Baroque

- 1586 Evangelical Castle Church in Königsberg , East Prussia; Württemberg builders Aberlin Tretsch and Blasius Berwart on behalf of the Franconian Margrave Georg Friedrich I.

- 1591 Evangelical Michaelskirche Asperg , Württemberg

- 1595 Evangelical Castle Church Sulzbach am Kocher, Württemberg - profaned in 1837

- 1599 Evangelical Church in Braunsbach-Döttingen , Württemberg; Extension of the Romanesque choir tower church

- Early 17th century: Evangelical Johanneskirche Weinsberg from 1200, Württemberg; Conversion to a transverse church, dismantled in 1947

- 1601 Evangelical Church Aidlingen- Dachtel , Württemberg, Renaissance; ducal master builder Heinrich Schickhardt , converted into a longitudinal church in 1972

- 1602 Evangelical St. John Baptist Church in Hornberg in the Ortenau district (Baden); Wuerttemberg property, ducal master builder Heinrich Schickhardt

- 1602 Evangelical Church in Öhringen- Ohrnberg , Württemberg

- 1605 Heidenheim an der Brenz , castle church Hellenstein Castle , Württemberg; Renaissance; ducal builders Heinrich Schickhardt and Elias Gunzenhäuser - since 1901 municipal museum

- 1606 Evangelical Church Deyelsdorf , Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania; Renaissance

- 1607 Evangelical Bonifatius Church in Braunsbach am Kocher , Württemberg

- 1607 Evangelical Church of Saint-Martin in Montbéliard (Mömpelgard), then a county of Württemberg in Burgundy; Renaissance; ducal builder Heinrich Schickhardt

- 1607 Evangelical town church St. Veit Waldenbuch , Württemberg; Ducal builder Elias Gunzenhäuser , † 1606

- 1607 Evangelical castle chapel Rotenburg an der Fulda , Hesse; Demolished in 1790

- 1610 Evangelical Georgskirche Horkheim , Württemberg; Renaissance; ducal builder Heinrich Schickhardt

- 1610 Evangelical Lutheran Trinity Church in Haunsheim near Dillingen / Danube (Bavarian Swabia), directly under the Empire; Renaissance

- 1612 Evangelical Lambertus Church in Pfaffenhofen , Württemberg (planning for master builder Heinrich Schickhardt )

- 1612 Evangelical town church St. Salvator Neckarbischofsheim , Baden; Renaissance

- 1612 Evangelical-Lutheran Sand Church in Schlitz , Vogelsbergkreis / Hessen, small cemetery church with inner and outer pulpit, oldest preserved transverse church in Hesse

- 1613 Evangelical Peter and Paul Church in Köngen , Württemberg; Renaissance

- 1613 Evangelical Castle Church Maienfels , Württemberg; Renaissance

- 1615 Evangelical Dreifaltigkeitskirche Leutkirch , Free Imperial City (now Württemberg) - (Builder Daniel Schopf from Isny, with reference to builder Heinrich Schickhardt )

- 1618 Evangelical town church Vaihingen an der Enz , Württemberg; Reconstruction after city fire; ducal architect Heinrich Schickhardt - converted into a longitudinal church in 1893

- 1618 Evangelical Kilian Church in Waldbach , Württemberg; Renaissance; ducal builder Friedrich Vischlin

- 1619 Evangelical City Church in Göppingen , Württemberg; ducal architect Heinrich Schickhardt - with almost 41 × 21 meters, the largest Protestant Renaissance and transverse church; 1772 interior rebuilt to a longitudinal church

- 1619 Evangelical Lutheran town church Peter and Paul Sebnitz , Saxony; Renaissance

- 1621 Evangelical Marienkirche Bretzfeld- Adolzfurt , Württemberg; ducal builder Heinrich Schickhardt

- 1621 Evangelical Holy Cross Church in Sternenfels-Diefenbach , Württemberg; Renaissance; ducal builder Heinrich Schickhardt

- 1621 Evangelical Laurentius Church in Erbstetten , Württemberg

- 1621 Evangelical Dreifaltigkeitskirche Ulm , Free Imperial City (now Württemberg) - destroyed in 1944, rebuilt for another use

- 1621 Evangelical town church Geislingen from 1424/28, pulpit built in 1621 on the central north pillar, Württemberg; In 1892 it was converted into a longitudinal church

- 1624 Evangelical town church Bad Wildbad , Württemberg; Renaissance; ducal builder Heinrich Schickhardt , burned down in 1742 and replaced by a new building

- 1624 Evangelical hospital church in Biberach an der Riss , Württemberg

- 1624 Evangelical Laurentius Church Bretzfeld- Bitzfeld , Württemberg; Renaissance; ducal builder Friedrich Vischlin

- 1626 Evangelical St. George Church in Rotfelden , Württemberg; Renaissance; ducal builder Friedrich Vischlin

- 1641 Protestant Bremen Cathedral from 11th to 13th Century, Bremen; from the middle of the 16th century initially occasionally, from 1638 finally Protestant; since 1641 with the installation of the stalls and the baroque pulpit in the central nave as a transverse church

- 1651 Evangelical old village church in Bartenbach (Göppingen), Württemberg; Use since 1983, property of the Armenian Community of Baden-Württemberg in 2019, now: Heilig Kreuz Kirche

- 1660 Evangelical town church Schorndorf , Württemberg; Ulm master builder Joseph Furttenbach - converted into a longitudinal church in 1959

- 1664 Evangelical Old Johannes Church in Hanau , formerly Lutheran Church , Hesse; rebuilt after severe war damage (1945) changed

- 1669 Evangelical Martinskirche Langenau , area of the Free Imperial City of Ulm (now Württemberg)

- 1681 Evangelical Castle Chapel Stetten im Remstal , Württemberg, Baroque

- 1683 Evangelical Lutheran St. Salvatoris Church Clausthal-Zellerfeld am Harz, Renaissance; 1864 Conversion of the hall church with wooden barrel vaults into a three-aisled and seven-bay hall church with ribbed vaults

- 1684 Evangelical Reformed Neander Church in Düsseldorf , Rhineland; Early baroque

- 1692 Castle Church (Eisenberg) , Thuringia, Baroque

- 1692 Evangelical Reformed Huguenot Church Erlangen , Franconia; oldest Huguenot church outside France

- 1696 Evangelical Marienkirche Altheim (Alb) , Württemberg; Baroque; In 1975 converted into a longitudinal church

- 1698 Evangelical St. Vitus Church Stetten im Remstal , Württemberg, Baroque, ducal building contract

- 1699 Evangelical Lutheran St. George Church in Schwarzenberg , Ore Mountains / Saxony

- 1700 Evangelical parish church Walddorf in Walddorfhäslach , Württemberg; Conversion to the transverse church

- 1704 Evangelical Church Carlsdorf , Hofgeismar, "the only transverse hall among the Huguenot and Waldensian churches in Hessen-Kassel"

- 1713 Evangelical Lutheran Castle Church in Weilburg , Hesse

- 1717 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Helpershain near Ulrichstein , Hesse

- 1722 Evangelical Nikolauskirche Unterheinriet from 1250, Württemberg; Extension to the transverse church

- 1722 Evangelical Church (Wabern) , Hesse - canceled in 1910

- 1723 Evangelical Reformed Church in Eisemroth near Siegbach , Hesse

- 1726 Evangelical Reformed Church Wabern (Hesse)

- 1731 Evangelical Martins Church in Tuningen , Württemberg

- 1731 Evangelical Reformed Reinhard Church in Steinau an der Strasse , Hesse

- 1731 Evangelical Lutheran Church "Zur Himmelspforte" Ober-Eschbach near Bad Homburg vor der Höhe , Hesse

- 1733 Evangelical Reformed Church in Lichenroth near Birstein , Hesse

- 1735 Evangelical parish church in Langenselbold , Hesse

- 1736 Evangelical Church Rodheim near Rosbach vor der Höhe , Hesse

- 1738 Evangelical Church in Graevenwiesbach , Hesse

- 1738 Evangelical Reformed St. Peter's Church in Kirchheimbolanden , Palatinate

- 1738 Evangelical Lutheran Church on Graben Kassel , Hesse - destroyed in the war in 1943

- 1739 Evangelical Mauritius Church in Kirchheim am Neckar , Württemberg

- 1739 Evangelical Trinity Church Zossen , Brandenburg; Baroque

- 1739 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Heftrich near Idstein / Taunus, Hesse

- 1739 Kreuzkirche (Sehnde) near Hanover, baroque

- 1740 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Neunkirchen (Westerwald) , Hesse

- 1741 Evangelical Church in Burgbracht , Hesse

- 1741 Evangelical Reformed Church in Wölfersheim , Hesse; Baroque

- 1742 Evangelical Reformed Church in Marköbel near Hammersbach , Hesse

- 1742 Evangelical Reformed Wilhelmskirche Bad Nauheim , Hesse

- 1743 Evangelical Martinskirche Gruibingen from 12./14. Century, Württemberg, 1743 to a transverse church, 1974 converted to a longitudinal church

- 1744 Evangelical Lutheran Paulskirche Kirchheimbolanden , Palatinate

- 1746 Evangelical Reformed Church of Peace Saarbrücken , Saarland

- 1750 Evangelical-Lutheran town church Erbach (Odenwald) , South Hesse

- 1750 Evangelical Reformed Church Birstein-Unterreichenbach , "Vogelsberg Cathedral", Hesse

- 1750 Evangelical Lutheran castle church in Altenburg near Alsfeld, Hesse

- 1750 Evangelical Church in Ostheim near Butzbach , Hesse

- 1751 Evangelical Peter and Paul Church Gerabronn , Württemberg; 1967 complete interior redesign

- 1751 Evangelical St. Agatha Church Unterweissach , Württemberg

- 1751 Evangelical Church of the Holy Cross in Weiler an der Zaber , Württemberg; Baroque

- 1751 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Stammheim near Florstadt , Hesse

- 1754 Evangelical Twelve Apostles Church Neuhausen an der Erms , Württemberg, Rococo

- 1756 Evangelical Church in Bicken near Mittenaar , Hesse

- 1756 Evangelical Laurentius Church in Bieber , Hesse

- 1757 Evangelical Church in Ruppertsburg near Gießen , Hesse; Baroque

- 1760 Evangelical Martinskirche Gomadingen , Württemberg; Baroque

- 1761 Evangelical Luther Church Pirmasens , Palatinate

- 1767 Evangelical town church in Aalen , Württemberg, baroque, planning by Johann Adam Groß

- 1771 Evangelical Blasius Church Engstingen-Kleinengstingen , Württemberg, Rococo

- 1775 Ludwigskirche (Saarbrücken) , baroque

- 1775 Evangelical Stephanus Church in Alfdorf , Württemberg, baroque

- 1779 Evangelical Luther Church Fellbach , Württemberg; Late Baroque and Classicism - a new ship was built by Johann Adam Groß

- 1780 Evangelical St. Peter's Church in Steinheim am Albuch , Württemberg

- 1782 Evangelical Johanneskirche Rudersberg , Württemberg; Baroque - new ship building by Johann Adam Groß , converted into a longitudinal church in 1957

- 1782 Evangelical Reformed Church Langsdorf , Hesse, Rococo

- 1784 Evangelical Baptist Johannes Church Warmbronn , Württemberg

- 1785 Evangelical Laurentius Church in Hemmingen , Württemberg; Baroque

- 1786 Evangelical Church Wittendorf , Württemberg

- 1788 Evangelical St. Veit Church in Braunsbach-Geislingen am Kocher , Württemberg; In 1963 it was converted into a longitudinal church

- 1791 Evangelical Lutheran Petrikirche Ratzeburg , Schleswig-Holstein, late baroque and classicism

- 1792 Evangelical St. Stephen's Church in Heuchlingen (Gerstetten), Württemberg, Baroque

- 1792 Evangelical Mauritius Church in Mötzingen , Württemberg, built by Johann Adam Groß

- 1799 Evangelical Church in Seewald-Hochdorf, Württemberg

- 1805 Michaeliskirche (Wolfsburg-Fallersleben) , Lower Saxony, classicism

- 1806 St. Marien (Neuruppin) , Brandenburg, classicism

- 1808 Friedberg Castle Church , Hesse, Classicism

- 1813 Evangelical Church (Bellersheim) , Hesse, Classicism

- 1816 Evangelical St. Gallus Church in Welzheim , Württemberg

- 1826 Reformed Church (Lübeck) , classicism

- 1830 Church (Wißmar) , Lahn / Hessen, late classicism

- 1832 Evangelical St. James Church Auenstein , Württemberg; Cameral office style , converted into a longitudinal church in 1969

- 1833 Evangelical Church in Schömberg , Württemberg; Cameral office style , converted into a longitudinal church in 1928

- 1833 Paulskirche in Frankfurt , Hesse

- 1834 Evangelical Michael Church in Winzerhausen , Württemberg; Camera office style

- 1835 Bartholomäuskirche (Vellberg-Großaltdorf) , Württemberg

- 1837 Evangelical Church of the Holy Cross, Saint Peter and Genovefa, Ellhofen from 1380, Württemberg; 1837 conversion to a transverse church, 1977 expansion and reinterpretation as a transverse church

- 1843 Paulskirche Dinkelsbühl , Franconia, historicizing style, then called Byzantine

- 1904 Evangelical Johanneskirche Untergruppenbach , Württemberg; formerly Art Nouveau

- o. J. Herrnhuter Prayer Hall , in different places

- undated parish church Jugenheim , Hesse

- Longitudinal churches converted to a transverse church

- After 1970 the Roman Catholic Church of St. Mary's Conception (Monschau) ("Aukirche", main parish church, until 1802 the Minorite monastery church )

- 1993 Evangelical Martin Luther Church Mössingen , Württemberg (from 1964), after complete renovation

Switzerland

- Existing transverse churches

- Chêne-Pâquier Church , 1667

- Reformed Church Wilchingen , 1676

- Samedan Reformed Church , after 1682

- Sornetan Reformed Church in Sornetan , 1708–09

- Reformed Church Zurzach , 1716–1724

- Temple Neuf (La Neuveville) , 1720

- Chaindon Reformed Church , 1739–1740

- Yverdon Reformed Church , 1753–1757

- Chêne-Bougeries Reformed Church , 1756–1758

- Reformed Church Le Locle , 1758–1759

- Reformed Church Wädenswil , 1764–1767

- Bémont Reformed Chapel , 1767

- Bauma Reformed Church , 1769–1770

- Reformed Church Embrach , 1779–1780

- Reformed Church Horgen , 1779–1782

- Reformed Church Grüningen , 1782–1783

- Reformed Church of Kloten , 1785–1790

- Reformed Church in Hinwil , 1786–1787

- Reformed Church Speicher AR , 1808-10

- Evangelical Church Altnau , 1810–12

- Reformed Church Netstal , 1811–1813

- Old Church Albisrieden , 1816–1817

- Reformed Church Gossau , 1820–1821

- Reformed Church of Saint-Sulpice NE , 1820–1821

- Reformed Church Seengen , 1820–1821

- Reformed Church in Meisterschwanden , 1820–1822

- Reformed Church Uster , 1822–1828

- Reformed Church in Bäretswil , 1825–1827

- Colombier Reformed Church , 1828

- Sonvilier Reformed Church , 1831–1832

- Reformed Church Wattwil , 1844–1848

- Reformed Church Thalwil , 1846–1847

- Grossmünsterkapelle Zürich , 1858–60

- Kirchgemeindehaus Liebestrasse Winterthur , 1911–1913

- Longitudinal churches converted to a transverse church

- La Brévine Reformed Church , 1604 (renovation:?)

- Nossa Donna Castelmur , around 1100 (conversion: 1840–63)

- Reformed Church of Cortaillod , 1505 (renovation: 1722)

- Baulmes Reformed Church , 11th century (renovation: 1871)

- Reformed Church Zurich-Unterstrass , 1882–1884 (renovation: 1962–63)

- Reformed church Hausen am Albis , 1751 (renovation: 1970)

- Reformed Church Rüschlikon , 1713–14 (renovation: 1971–72)

- Transverse churches converted into a longitudinal church

- Reformed Church Courtelary in Courtelary , medieval building, expanded to a transverse church in 1642/1733, converted into a longitudinal hall in 1933–36

- Reformed Church of Tavannes , built in 1385, extended to a transverse church in 1728, converted into a longitudinal hall in 1971–72

- Oron-la-Ville Reformed Church , 1678 (reconstruction: 1816)

- Temple du Bas (Neuchâtel) , 1695–1703 (renovation: 20th century)

- Reformed Church of Péry in Péry , 1706 (renovation: 1910)

- Maienfeld Reformed Church , 1721–1724 (reconstruction: 1931)

- Reformed church Sombeval in Sonceboz-Sombeval , 1733–1737 (renovation: 1866)

- Reformed Church Heiden AR , 1837–1839 (renovation: 1936)

- «False cross churches»

In some buildings, the axis structure of the exterior suggests a transverse church, but the interior is arranged as a longitudinal church.

- Reformed Church Othmarsingen , 1675 (tower: 1895)

- Reformed Church Schwerzenbach , 1812–13

- Reformed Church Gächlingen , 1844–45

- Transverse churches within building complexes

- Reformed Church Greifensee , 1344

- Markuskirche Zurich-Seebach , 1947–48

- Rosenberg Reformed Church , 1964–66

- Gellert Church (Basel) , 1964

- Evangelical Church Center Jona , 1975

Netherlands

- Reformed denomination

- Zuiderkerk (Amsterdam) , 1603–1611

- Westerkerk (Amsterdam) , 1620-1631

- Protestantse Kerk, Bloemendaal , 1635–1636

- Nieuwe Kerk (The Hague) , 1649–56

- Leiden , Waardkerk, 1662

- Lutheran denomination

- Mennonite denomination

- Doopsgezinde Kerk, Workum

- Singelkerk , Amsterdam

Denmark

Norway

- New Church in Bergen , 1700–02

France

- 1583 Montpellier, Grand Temple of the Huguenots

- 1608 Dieppe, Temple of the Huguenots

- 1612 Caen, Temple of the Huguenots

- 1634 Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines, Temple of the Huguenots, Vosges

- 1680 Saumur, Temple of the Huguenots

- 1728 Evangelical Lutheran Church Buchsweiler , Dept. Bas-Rhin

- 1751 Evangelical Lutheran Church Waldersbach , Vosges

- 1751 Evangelical Reformed Temple Neu-Saar Werden , Dept. Bas-Rhin

Italy - Catholic Cross Churches

- Pazzi Chapel in Florence , 1442–1461 by Filippo Brunelleschi

- Madonna di Pie 'di Piazza in Pescia , 1447 by Andrea Cavalcanti

- Sant'Andrea al Quirinale in Rome , 1658–1670 by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

- San Giovanni in Bassano del Grappa , 1747 and 1782–85

Great Britain

- Saint Andrew's Church, Edinburgh

- Old Congregational Chapel, Walpole (Suffolk) , 1647

- Friar Street Chapel, Ipswich

United States

- Wethersfield (Connecticut) , 1761

See also

literature

- Erwin Rall: The Protestant Church Buildings in Swabia and Southern Franconia in the 16th and 17th centuries ; Dissertation, Stuttgart 1922

- Joseph Killer: The works of the master builder Grubenmann - a structural history and structural research work ; Dissertation at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich; Zurich 1942 - available as PDF on [10] , last accessed on February 25, 2019

- E. Stockmeyer: The transverse space principle in the Zurich country churches around 1800. A contribution to the problem of Protestant church building. , in: Das Werk 30, 1943, pp. 61–64.

- Georg Germann: The Protestant Church Building in Switzerland. From the Reformation to Romanticism. Zurich, 1963.

- Siegwart Rupp: About Protestant Church Building in Württemberg ; in: Schwäbische Heimat, issue 2/1974, Stuttgart 1974, pages 123-136 - with a listing of post-Reformation church buildings in Württemberg. However, Rupp's basic assumption that the Schickhardt churches were oriented lengthways and led "as a type creation" to the Württemberg camera office churches of the 19th century has now proven to be wrong.

- Alfred Schelter: The Protestant church building of the 18th century in Franconia ; Vol. 41 of the series Die Plassenburg , Kulmbach 1981 - Extended version of the building history dissertation at the TU Berlin from 1978 ("Interior architecture of Franconian religious buildings of Protestantism in the 18th century")

- Ehrenfried Kluckert: Heinrich Schickhardt - architect and engineer ; Herrenberger Historische Schriften Volume 4, Herrenberg 1992, Chapter The Protestant Church Building Type, pp. 115-134 - still without the use of the term transverse church !

- H. Schneider: Voyage of discovery - Reformed church building in Switzerland. Zurich 2000

- Regnerus Steensma: Protestants kerken hun pracht en kracht . Gorredijk 2013

- Michael D. Schmid: transversely built. Transverse churches in the canton of Zurich . Wädenswil 2018

- Michael D. Schmid: lateral thinkers and lateral churches. History of a building type , in: etü - Historikerinnen-Zeitschrift des Historisches Seminar der Universität Zürich, Issue 1/2018, Zürich 2018, pp. 72–74.

Web links

- http://www.ag-landeskunde-oberrhein.de/index.php?id=p440v

- Texts, pictures and floor plans of Hessian cross churches

Individual evidence

- ↑ Harold Hammer-Schenk: Art. Church building III ; in: Gerhard Müller (ed.): Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 18, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1989, ISBN 3-11-017388-3 , pp. 456–498 [461.463]

- ↑ (for example) Andreas Stiene: The Stettener Querkirche - An early example of its building type ; in: Andreas Stiene, Karl Wilhelm: Old stones - new life. History and stories of the Evangelical village church in Stetten im Remstal ; Stetten im Remstal 1998

- ↑ in their online magazine Monuments February 2017 edition (last accessed on February 5, 2019)

- ↑ Matthias Figel: The Reformation sermon service. An investigation into the history of the liturgy on the origins and beginnings of Protestant worship in Württemberg ; Epfendorf / Neckar 2013 - as well as: Matthias Figel: sermon worship , in: Württembergische Church History Online, 2014 - Permalink: [1]

- ^ D. Martin Luther's works, Weimar edition; Critical Complete Edition Volume 49, Weimar 1913, pages 588–615 - available at [2]

- ^ Doct. Martinus Luther: Inauguration of a Newen house for the preaching room of Divine Words erbawet / In the Electoral Palace at Torgaw . Wittenberg 1546. Reprint for the 450th anniversary of the parish church in October 1994; ed. Ev. Torgau parish, 1994

- ↑ Martin Luther: Inauguration of a new house for the preaching office of the divine word, built in the electoral palace in Torgau (1546) , Notger Slenczka, transmission: Jan Lohrengel; in: Martin Luther: German-German Study Edition (DDStA), Volume 2, edited by Dietrich Korsch and Johannes Schilling; Leipzig 2015, pp. 851–891

- ↑ https://archiv.ekd.de/aktuell/edi_2015_05_16_schlosskirche_torgau.html

- ↑ More detailed on this and the seating arrangement: Andreas Rothe: Theologie in Stein und Bild ; in: The Castle Church of Torgau - Contributions to the 450th anniversary of the inauguration by Martin Luther; ed. Torgauer Geschichtsverein eV and Ev. Parish of Torgau; Torgau 1994, page 13.

- ↑ Joseph Leo Koerner: The Reformation of the Image ; From the English by Rita Seuss; Munich 2017, Chapter 22: Church Building, Notes 44–48

- ^ Erwin Rall: The Church Buildings of the Swabians and Southern Franconia in the 16th and 17th Centuries ; Typewritten dissertation at the Technical University of Stuttgart 1922, pages 8, 13 ff, 43

- ↑ Ilse-Käthe Dött: Protestant Querkirchen in Germany and Switzerland ; Typewritten dissertation, Münster 1955, pages 71–141 - The listing of earlier Württemberg cross churches no longer corresponds to the current state of research

- ↑ Walther-Gerd Fleck: The Protestant Church in Ohrnberg (Krs. Öhringen). The rural example of an early Protestant preaching room ; in: Newsletter of the preservation of monuments in Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart 1966, volume 3/4, pages 101-107 - viewable as PDF in: [3] - The last paragraph of the article as well as the preceding list of churches is groundbreaking for the Protestant type Transverse church

- ↑ Walther-Gerd Fleck; Luther Church Fellbach ; Self-published by Lutherkirche, Fellbach o. J. [1973], 12–16

- ^ Günther Memmert: The city church in Aalen and the Stephanus church in Alfdorf. On the type of Protestant cross-hall church in the Swabian Baroque . Dissertation, University of Stuttgart, 2010 - available at [4] - The assessment of the Aalen and Alfdorf churches as rare examples of Württemberg transverse churches (p. 97 ff and 146 ff), their classification in the history of church building and the listing of earlier Württemberg transverse churches no longer corresponds the current state of research

- ↑ Service book for the Evangelical Church in Württemberg - electronic ; CD-ROM, ed. Evangelical Oberkirchenrat Stuttgart; Stuttgart 2005, supplementary volume, page 2

- ↑ The service. A guide to understanding and practicing worship in the Protestant Church , Chapter 2.4 The Reformation renewal of worship; Published on behalf of the EKD Council in 2009 by the Gütersloher Verlagshaus, ISBN 978-3-579-05910-5 - available as a PDF at [5] , last accessed on December 21, 2018

- ↑ Kathrin Ellwardt: The type of the transverse church in the evangelical territories of the empire , in: Jan Harasimowicz (Hrsg.): Protestant church building of the early modern times in Europe. Basics and new research concepts ; Regensburg 2015, pp. 175–188 - but due to the lack of a tangible overview at this point in time (which the author herself regrets in note 22), almost without taking into account the extensive Württemberg transverse church building up to 1800

- ↑ Jörg Widmaier: Church stands across. The search for the "ideal" Protestant church building in Baden-Württemberg ; in: Monument Preservation in Baden-Württemberg. News bulletin of the State Monument Preservation, Volume 46, No. 4/2017, Stuttgart 2017, pages 244–249; available as a PDF on uni-heidelberg.de - Unfortunately Jörg Widmaier does not consider - apart from the Schlosskirche Stuttgart - the other transverse churches of the Renaissance and Baroque in Württemberg

- ↑ Kathrin Ellwardt: Church building between evangelical ideals and absolutist rule. The cross churches in the Hessian area from the Reformation century to the Seven Years War . Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg 2004, ISBN 3-937251-34-0

- ^ Almut Pollmer: Church pictures. The church interior in Dutch painting around 1650 ; Dissertation, University of Leiden 2011 - available as PDF see [6] , last accessed on June 4, 2019

- ^ Alfred Schelter: The Protestant church building of the 18th century in Franconia ; Volume 41 of the series Die Plassenburg , Kulmbach 1981, p. 35 - Extended version of the building history dissertation at the Technical University of Berlin from 1978: Interior architecture of Franconian religious buildings of Protestantism in the 18th century

- ↑ An overview (French) is available at [7] , last accessed on June 23, 2019

- ↑ Ellwardt, Kirchenbau, p. 22

- ↑ For example: Günther Memmert: The city church in Aalen and the Stephanus church in Alfdorf. On the type of Protestant cross-hall church in the Swabian Baroque . Dissertation, University of Stuttgart, 2010 - available on [8] , page 8 - and both Reinhard Lambert Auer: Protestant spatial programs in Württemberg and: Jörg Widmaier: The reformed church building in the German south-west ; both in: cultural monuments of the Reformation in the German south-west; (Red.) Grit Koltermann and Jörg Widmaier; (Ed.) State Office for Monument Preservation in the Stuttgart Regional Council; Esslingen 2017, pages 65-85 (71) and pages 86-95 (87); available as a PDF on [9] - Reinhard L. Auer unfortunately only mentions a few early cross churches of the 16th and 17th centuries in Württemberg

- ↑ Nikolai Ziegler: Between Form and Construction - The New Lusthaus in Stuttgart . Jan Thorbecke Verlag, Ostfildern 2016, ISBN 978-3-7995-1128-5 , plus dissertation, University of Stuttgart, Stuttgart 2015