Bremen Cathedral

The St. Petri Cathedral in Bremen is a Romanesque church building made of sandstone and brick , which was built from the 11th century on the foundations of older predecessor buildings and has been rebuilt in the Gothic style since the 13th century . Side chapels were added in the 14th century . In 1502, the redesign into a late Gothic hall church began , but it did not get beyond a new north aisle when the Reformation stopped further extensions. In the late 19th century, the building, which was well cared for inside but looked shabby on the outside, was extensively renovated, one of the two towers of which had collapsed. The design was mainly based on the existing and old representations, but some innovations were also designed, such as the neo-Romanesque crossing tower . Today the church belongs to the Evangelical Lutheran cathedral parish of St. Petri. It has been a listed building since 1973 .

history

The Carolingian predecessor buildings

The place at the site of today's cathedral, the highest point of the Weser dune right next to an existing settlement, became the nucleus of the developing diocese with the construction of an allegedly consecrated church in 789 by the Anglo-Saxon mission bishop Willehad . The timber structure was burned down and completely destroyed as early as 792, only three years after its completion, in the course of the Saxon Wars . After the death of Willehad in 789, there was neither a bishop nor a cathedral in Bremen for 13 years. From the time of Bishop Willerich (805-835) and his successors, excavations in the central nave of today's cathedral have revealed several phases of construction of a stone church, which in its largest and latest expansion represented a three-aisled stone building, which was consecrated by the bishop in 860 Ansgar is associated.

Northwest of the traces of the north side wall of this three-aisled church, shortly before the western end of today's north aisle, a foundation from the 9th century running in north-south direction was discovered during the excavations. It was only after 2010 that it was recognized as a reference to a west transept, as it was built in the same epoch in Fulda , Paderborn and in Cologne's Hildebold Cathedral . These west transepts (for churches without east transepts) were used to worship relics. No archaeological evidence was found for the remainder of the shape of the Carolingian west transept in Bremen, especially not for the west choir (or at least a west apse ) found in the comparative buildings , because no excavations were made there.

On September 11, 1041, however, the Carolingian church - like much of the rest of the town's development - fell victim to the conflagration of the Bremen fire . The flames also irretrievably destroyed the holdings of the cathedral library.

The Salic construction phase

In the Salian period, beginning with the last years of office of Bishop Adalbrand (1035–1043), a fundamental new building fell, the dimensions and material traces of which can still be observed on the current structure. Adam von Bremen reports that Adalbrand, who is usually called Bezelin by his other name in the architectural history literature and who was Cologne canon , took the old Carolingian Cologne cathedral as a model. Floor plan dimensions, two choirs, two crypts and the patronage Petrus in the west choir and Maria in the east choir were adopted in Bremen. Adalbrand's successor Adalbert (1043–1072), one of the most powerful bishops of that era, according to Adam von Bremen, continued the construction based on the model of the cathedral in Benevento . Difficult, ambiguous and controversial is the assessment of the sequence of construction measures after 1042, especially with regard to the two crypts. When the high altar was consecrated in 1046, the east choir should have been raised and the east crypt underneath, if not completed, was at least constructed in a constructive manner. Perhaps the west crypt was consecrated in 1066. It suffered several alterations and drastic changes, most recently as a result of the cathedral restoration from 1888. In its sculpture of the capital one wanted to recognize the activity of Lombard stonemasons, which Adalbert is said to have brought with him from Italy. Adalbert endeavored to complete the cathedral while he was still in office, and therefore proceeded with construction with little regard to other requirements. So he had the wall of the Domburg pulled down in order to obtain building material. As a result, Bremen was sacked in 1064 by an army of the Saxon Duke Ordulf and his brother Hermann.

Liemar (1072–1101), Adalbert's successor, is referred to on a writing plate found in his grave as constructor huius ecclesiae (“builder of this church”). He was given the task of closing the big gap between the only partially completed choirs. He had the pillars and walls of the basilica nave pulled up and roofed over; the work in the crypts will probably only be completed during his term of office. The new building was now almost twice as large as its predecessor. How the west facade was planned and whether Liemar had already completed it is not clear. No evidence was found as to whether or not the present-day western towers had predecessors. In any case, the current line of flight of the west facade, which was advanced to the west, was not created until the late Romanesque phase.

Late Romanesque and Early Gothic

There are no documents about the beginning of the high medieval construction phase. The first components that were built during this period, i.e. the lower parts of the west facade and the lower floors of the west towers, do not yet have any Gothic style elements. They may have originated in the last two decades of the 12th and the first two of the 13th centuries.

During the term of office of Gerhard II (1219–1258) there were some important changes, both from an architectural point of view as well as from a church-political point of view. First, Pope Honorius III confirmed . in 1224 Bremen finally became the seat of the double archbishopric. That means that Bremen was now the seat of the archbishopric and Hamburg no longer had its own bishop. The cathedral chapter of Hamburg, endowed with special rights, remained in existence. Since then, Bremen Cathedral has been a metropolitan cathedral . The seal of the city of Bremen, introduced in 1230, which shows the tower front of the cathedral between Charlemagne and Bishop Willehad, gives an even if not very precise impression of the planning of the west facade at that time. The motif was later adopted in the Ihlienworther Altar , in the relief band on the west choir of the cathedral and in the town hall painting. The extensive renovations in the 39 years of Gerhard II's reign were clearly influenced by models from Westphalia and the Rhineland. Much was found similarly in church buildings under the rule of his relatives.

Vault

In 1224, Pope Honorius III approved . an indulgence to "repair" the cathedral. With the income made possible by this, the vaulting of the nave, which may already have begun, was carried out in two phases up to around 1250.

The vaults of the nave are very diverse. The two western bays of the central nave between the western towers were vaulted in front of all other naves, two different vaults that also differ from all the rest of the building. Next, the two low aisles were vaulted. The still preserved south aisle, predominantly domical vaults , resemble those of the Bremen Liebfrauenkirche .

In the second and last early Gothic phase, the vaults of the central nave, crossing, choir and transepts were created. They have relatively slightly sloping vertex lines. In the transept and transept, the weight of each vault yoke is evenly distributed over its four corners.

The ceiling of the main nave, however, consists of four six-span double yokes, each supported on six (wall) pillars. Due to the diagonal ribs of the double yokes, the weight of three quarters of the vaulted area rests on the pillars at the yoke corners. Only a quarter of the vault area rests on the pillars in between. One of the pairs of pillars under greater load belongs to the crossing. The other four heavily loaded pairs of pillars are stabilized by flying buttresses (since the late Gothic redesign of the north aisle only on the south side ) . There are no buttresses between the pillars. The vault of the choir consists of a double yoke. The middle pair of pillars has only been supported from the outside by flying buttresses since the subsequent stabilization of the choir in 1909/1910 . The buttress arches at the corners of the choir are medieval, but also not from the time of construction, they connect architecturally to the later added choir flank chapels. The choir of the Stephanikirche , which was built around the same time as the cathedral choir, has a similar vault and its buttresses are made of modern, small bricks.

Late Gothic period

After the parish for the market settlement and then the city of Bremen had been the St. Veit- / Liebfrauen -Kirchspiel since 1020 , divided into three parishes in 1229, the St. Wilhadi church , located a little to the south, became the parish church for the in the 14th century lay people living in the cathedral freedom . Thus the cathedral was only used for the services ( times of day and mass) of the archbishop and the cathedral chapter , as well as for special large ceremonies.

- Chapels and north tower

In the 14th and 15th centuries, several chapels were built on the south side of the church and a double chapel on the north side of the east choir. In 1346 the north tower was raised by two stories and it was given a Gothic helmet .

In a fire in the north tower in 1483, the north aisle was also badly damaged, which up until that time was probably very similar to the surviving south aisle. The same source provides contradicting information about the condition of the towers before this fire. The Ihlenworther Altar from the late 15th century shows two different cathedral models:

- In the upper right field of the right wing there is the Karl and Willehad motif, which was already known from the city seal of 1230. In this relief, the entrance area is depicted realistically, a gate under each tower, between - instead of the blind arcades - two windows, above a gallery. The rose window is very small. Both towers have horizontal walls and high, pointed roofs above. The masonry of the south tower is not quite as high as that of the north tower.

- In the right field of the middle panel, Willehad is standing alone with a model of the cathedral. In this case, the ground floor of the western front has only three openings, but unlike in the seal and later in the sculpture gallery, not between the towers, but distributed across the entire width. The rose window is shown slightly larger, in the form of a cross. In this relief, the masonry of both towers ends in gables, and both have high pointed roofs.

- North ship

During the tenure of Archbishop Johann III. Rode von Wale , the north aisle was brought to the height of the central nave from 1502 to 1522 and received a late Gothic reticulated vault . However, the north nave and central nave together do not give the impression of a hall, because the arcade between the two aisles is still divided into two floors; the lower one still comes from the Romanesque pillar basilica. This renovation was carried out by Cord Poppelken, who also shortened the west crypt around 1512 and created the choir screen for the west choir above (today the organ gallery), which was then decorated with the sculpture gallery. Possibly an increase in the south aisle and the extensive redesign of the cathedral to a hall church was planned . The beginning of the Reformation in Bremen prevented further expansion .

- missal

Archbishop Rode commissioned the printing of a missal in 1511 , the Missale secundum ritum ecclesie Bremense , which describes the rite for Holy Mass valid in the Diocese of Bremen .

reformation

On November 9, 1522, the expelled Augustinian monk Heinrich von Zütphen held the first Reformation sermon in Bremen in a chapel of St. Ansgarii Church . From 1524, Protestant preachers were appointed to the parish churches in addition to the Catholic priests. Catholic masses were banned in the parish churches in the city in 1525, in the rural areas in 1527 and in the monasteries in 1528.

In 1534 a church order approved by Luther was introduced.

The cathedral had already been closed by the cathedral chapter in 1532 after the committee of 104 men, who opposed the dominance of the merchants, interrupted the mass on Palm Sunday and forced a Lutheran service. After 15 years, the cathedral chapter in 1547 lifted the closure on again and certain at the proposal of Seniors, Count Christoph von Oldenburg , the of Overijssel originating Albert Rizäus Hardenberg for preacher . He turned out to be a radical reformist, which resulted in disputes between Lutherans and followers of Melanchthon . Eventually Hardenberg was expelled from the city on February 18, 1561, and the cathedral was closed for ordinary services for the second time in 29 years, this time for 76 years. However, it was opened on special occasions during this time, such as the inaugurations of office and other receptions of the archbishops, such as 1566 for Georg, 1588 for Heinrich von Lauenburg and 1637 for Friedrich II. There were also several burials, of the 28 epitaphs or grave slabs in the cathedral were created and attached fourteen years after it was closed.

Hardenberg was, however, supported by the majority of the citizens, the mayor Daniel von Büren (d. J.) and some councilors. The majority of the council wanted to take action against this, but a civil movement defended it in January 1562. This led to numerous opponents of Hardenberg leaving the city.

In the meantime, in 1558, Georg von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel had been elected Archbishop of Bremen and Bishop of Verden . He was open to the Reformation and introduced the Lutheran Bremen church order in the Diocese of Verden . From 1566 Lutheran archbishops were elected by the Bremen cathedral chapter, of course not recognized by the Roman church and therefore often referred to as administrators. The disputes in the city were resolved in February 1568, and the majority of Hardenberg's opponents returned.

In 1581, Bremen joined the theological direction of Philipp Melanchton in the so-called “second Reformation” , which was less rigid than Calvin's teaching , but nevertheless led the city into the Reformed camp and again isolated it from its surroundings. Fourteen years later, the city received a new church order based on the German Reformed form ( Consensus Bremensis ) , and the Heidelberg Catechism was introduced around 1600 . The cathedral as well as numerous properties and residents in the cathedral district were not subject to the city, but to the sovereignty of the archbishopric and thus remained Lutheran.

Tower disasters

The south tower of the cathedral did not have a pointed helmet on its four gables, but only a cross roof, but there were eight bells below it. It had been cracked for a long time and collapsed on January 27, 1638, burying two small houses attached to it. Eight people died in this accident.

The council clerk Metje, who stepped from the town hall onto the market square at the moment of the collapse , later described the event with the words:

“And as I come out of the door, I hear a rumble and break, as if someone were breaking through a thousand wooden poles at once. I immediately look up at the tower and I think my heart will stop! A long crack from top to bottom, and as I can still see it is getting wider and wider, and the roof disappears into the tower - yes, and then the walls will break down! It was a crash, I thought the whole cathedral would collapse! "

The city view of Merian shows the tower stump temporarily disguised and covered with a pent roof at about the height of the central nave roof. In the same year, the cathedral was ordered by the Lutheran Archbishop Friedrich III. Prince of Denmark reopened. Since then it has served as a sermon church for the Lutheran congregation within the Bremen city walls and received a diakonia on November 11th that same year .

As before the Reformation, the maintenance of the building continued to be financed from the income generated with the assets still coming from the medieval cathedral factory . While damage to the roofs was carefully repaired, the funds were insufficient to counter the weathering of the outside of the masonry.

In 1648 the Archbishopric of Bremen was secularized and passed to Sweden as the Duchy of Bremen . Eight years later, the cathedral suffered further serious damage: on February 4, 1656, the north tower burned down after a lightning strike. The roof of the central nave was also destroyed by the fire. The stump of the south tower was now open at the top. During its rapid repair, the north tower was first given a flat cover, then within five years a slightly inclined pyramid roof .

Largest preaching church in Bremen

The cathedral parish , which was responsible for maintaining the building, consisted of the Lutherans living within the walls of Bremen. Officially it was not a parish, but due to demographic shifts it grew from a small minority to the largest parish in Bremen by the end of the 18th century and belonged to the General Diocese of Bremen-Verden , established in 1651 . Several galleries were built in to accommodate the increasing number of people attending church services. Between 1694 and 1696 the church got a baroque main altar with canopy based on the model of the papal altar in the Roman St. Peter's Church and verses from Paul's 1st letter to the Corinthians , with which the Lutheran position of the Swedish Duchy of Bremen-Verden was emphasized. In the same period, between 1693 and 1698, the cathedral received one of the most valuable pieces of equipment in its history, the Arp Schnitger organ .

In 1715 Sweden transferred the rights to Bremen Cathedral to the electoral Hanover consistory in Stade . Under his administration, the north tower was given a Welsche hood made of sheet copper in 1767 . It replaced the simple pyramid roof that had been covering the tower since the fire 111 years ago, but the majority of the Bremen population saw it as unsuitable for the tower.

Around the same time, the medieval rose window was replaced by a simpler one after rain had endangered the organ.

Dom becomes city-Bremen

According to the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803, the cathedral area fell to the city of Bremen and was incorporated. The cathedral still lacked parish status, but in 1810 the cathedral parish was officially founded as the Lutheran parish of the city of Bremen in a contract between Lutheran representatives and the council and Johann David Nicolai was approved as pastor primarius . They also received a large part of the cathedral property back, from whose income the maintenance of the cathedral church was financed. However, there was insufficient funds for design measures. This would have required donations and grants. After the economic bottleneck of the Napoleonic era , the conversion of the also dilapidated archbishop's palatium into a (for the time) modern administration building, the town hall , had priority. Then infrastructure measures for Bremen's position as an ocean port claimed all of the Free Hanseatic City's funds. So the city did not spend any money on the cathedral.

As early as 1817, following a council resolution, several small houses built on the north wall were removed and the now exposed wall was repaired with funds from the cathedral. Extensive renovation and embellishment work took place inside from 1822, financed by donations. Among other things, the cathedral received a neo-Gothic main altar in 1839/40 and, in 1853, for the first time since the Reformation, colored glazing. The vault of the north aisle and the towing roof above were also thoroughly renovated. The outer appearance was determined by the north tower with the Welscher hood and the collapsed south tower for nine decades in the 19th century.

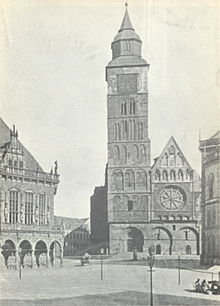

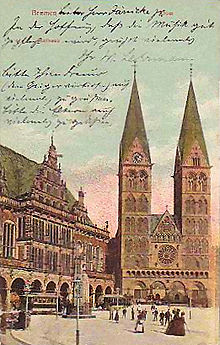

Complete renovation 1888-1901

Only in the 1880s were plans developed for a radical renovation of the cathedral. This was then financially supported by the Bremen citizenship by Franz Ernst Schütte , carried out from 1888 on the ideas of the cathedral builder Max Salzmann . It was intended to restore the medieval state, but then made some changes.

The most striking construction work concerned the west towers, which were designed symmetrically for the first time in at least 500 years. The masonry of the north tower was replaced on the upper floors and redesigned based on the lost south tower. The core of the lower three to four storeys was retained, but the partly heavily weathered facing was removed and partly made of new, partly reconditioned old stones. Since efforts were made to use new facing bricks from the same locations ( Porta Westfalica and Obernkirchen ) as in the Middle Ages, chemical-physical investigations to differentiate between medieval and newly acquired bricks are not very meaningful. The south tower was completely rebuilt from the foundation and for the first time also provided with a pointed spire. Apart from the design of the top tower storeys with larger and more plastic framed windows, these measures can be justified as eliminating losses and completing medieval concepts. The foundation stone for the south tower was laid in 1889, and only four years later both towers were completed.

The gallery above the entrance floor, made of wood in front of blind arcades in the 16th century, has now been designed as a stone arcade. The rose window, which had previously started on or even below the upper edge of the roof of the gallery, was set higher, so that the rose window level and the storeys of the central nave façade above are now a little higher to the tower storeys than before the reconstruction. The rose window is now more splendid than in the 19th century, but based on representations from the 15th and 16th centuries.

While the west facade consists of components that come close to the original, the crossing tower is to be rated as an arbitrary neo-Romanesque ingredient. It is hardly any different with the neo-Gothic bridal portal. The crossing tower echoes the two original medieval central towers of Worms Cathedral . It required considerable effort, as the crossing pillars had to be replaced unattractively for it - while maintaining the medieval vault supported by them.

In the interior of the nave, the parish galleries and the side choir barriers against which the back rows of the choir stalls, removed in 1822, had leaned, were removed. All interior walls were always has known for nearly two centuries limed Service. During the renovation, remains of colored medieval painting were found in numerous places. The new wall painting Schapers was influenced by Byzantine models. It has essentially been retained to this day. The glass windows with depictions of important scenes from the Reformation, which were destroyed in the Second World War, were created by the Frankfurt artist Alexander Linnemann .

20th century

Soon after completing the major renovation, it became apparent that the crossing tower was endangering the statics. Additional buttresses were built between the windows on both sides of the choir. The east wall was also stabilized and only received its current facing. At the beginning of 1915, a large fire destroyed the bell and other parts and subsequent buildings of the cathedral monastery. The cloister survived the fire, but was demolished in 1925 when today's bell building was built.

During the Second World War , the cathedral was hit by fire bombs during an air raid on Bremen in 1943 . The damage was initially limited; only the panes of the south aisle broke. In the following year of the war, the church suffered further bomb hits. In March 1945, an explosive bomb exploded on the north side of the cathedral . As a result, parts of the vault collapsed in the north aisle. The entire building was considered to be in danger of collapsing. Some of the rubble stones from this attack are still in the cathedral as a memorial. Immediately after the end of the war, the restoration of the roof structure of the north nave began in 1946 ; by 1950 the destroyed vault was restored.

From 1973 to 1984 extensive archaeological excavations were carried out in and around the cathedral under the direction of the state archaeologist (1973 in the central and south aisles, 1979 in the north aisle, 1983 in the east crypt and 1984 in the lead cellar ). During these investigations one found the foundation walls of the previous buildings, several graves of former archbishops and gained insights into the building history. The finds made in the process were divided between the Cathedral Museum and the Focke Museum . In addition to the excavations, maintenance work was carried out to repair damage to the foundations and walls and to bring the interior furnishings closer to the state in the Middle Ages compared to the changes in the 19th century.

architecture

The Bremen Cathedral is around 93 m long. The height of the west towers is just below that.

Nave

Although the cathedral has the main nave, side aisles and transept of a cruciform basilica , the transept does not protrude laterally over the nave and has only been highlighted by its own roof ridge and a crossing tower since the renovation in the late 19th century . Before that, the transept, like the late Gothic elevated north aisle, was only covered with pent roofs, which is unusual for a transept. The fact that the main nave has a choir at each end is not uncommon in the German version of the Romanesque period, and that there is a hall crypt under both choirs is a specialty. The east crypt extends from the choir to the crossing . From the 14th century to the 1890s at the latest, the raised area above was functionally part of the choir. Lateral walls from the height of the Romanesque pillar arcades separated it from the transept arms. Here, under the crossing, the choir stalls stood in two rows on both sides, with the back row leaning against the wall.

Although all parts of the church interior were arched and the height of the north aisle was adjusted to that of the central and transept at the beginning of the 16th century, the central nave is still limited on both sides by the low arched arcades of the pillar basilica from the 11th century. On the north side of the central nave, the upper aisle was replaced by Gothic arcades in the 16th century.The south side remained basilical . It received Gothic vaults and pointed arched windows, as well as outer buttresses in front of every other vaulted pillar; Due to the six-part double yokes of the central nave vault, the vaulted corners supported in this way carry three quarters of the load and the sideshift, the others only a quarter. The pillars of the flying buttresses emerge today from the middle of the towing roof below the upper aisle; its lower parts have disappeared into the partition walls of the attached row of high Gothic chapels. There is no triforium storey between the arcade and the upper storey ; This floor is often seen as essential for Gothic basilicas, but the Freiburg Minster and a few others do not have any.

Choir and south transept around 1820, left the octagonal " bell "

and transept are old: the upper aisle of the central nave and west wall of the south transept at the transition from the Romanesque to the Gothic, the row of chapels below in front of the aisle is High Gothic.

The external appearance of the church building is kept relatively simple. The medieval facades are characterized by the Romanesque , the Romanesque-Gothic transition style and various forms of the Gothic . Until the early Gothic period, the masonry was made of solid stone , but in the area of the tower facade with coarse inner walls and carefully hewn outer skin. The high-Gothic row of chapels in front of the south nave is the only outer wall made of brick . The brickwork of the Gothic north facade is faced with sandstone, similar to the Schütting, which was built only a little later . In its original state, the eaves had no tracery balustrade , but in one place a closed one decorated with a frieze. Today in forms of late Gothic held neo-Gothic bride Portal was out of the (possibly translated) Roman garb simply. There are “ bridal portals ” on the north side of a number of churches. The right-angled instead of radial round window on the north wall of the transept replaced a historicist window group after the Second World War .

Main towers

The two main towers of the Bremen Cathedral are square, they have a base side length of 11 m. The height information differs: The total height for the south tower is 93.27 m (north tower 93.26) according to GeoInformation Bremen or 92.31 m according to Born. Without the 2.38 m high weather vanes it is 90.89 m. In relation to sea level (NN), the height of the south tower with the weather vane is 103.79 m.

As already shown in the building history, the south tower was completely rebuilt in 1888–1893, the north tower at least partially rebuilt, but in forms that had been realized in at least one of the two before 1600.

The cathedral towers with their copper helmets, which are now covered with patina , are the tallest church towers in the city of Bremen and the only ones with a viewing platform. This is located in the south tower exactly above the base line of the gable triangles, i.e. at a height of about 57 meters. It can be reached via 265 stone steps. The north tower is normally closed to the public and is only opened on special occasions (for example, Monument Open Day ).

The north tower has a tower clock with two dials, one in the west and one in the north gable, and a striking mechanism . The clock has been operated electromechanically since 1961. The corresponding clockwork was made by the tower clock manufacturer Eduard Korfhage & Söhne , headquartered in Buer . Thanks to its weight, the Bremen cathedral tower clock is able to automatically set itself to the correct time after a power failure . At the beginning of a power failure, the clockwork also cuts out and a weight expires. The length of the distance it covers corresponds to the duration of the power failure. When it ends, the weight is retracted and the clock is set accordingly. The cathedral clockwork must be serviced once a month.

West facade

The west facade, which was renewed around 1900, was originally built from the 13th century, probably after 1224, about 10 m west of the early Romanesque west end. The rose window between the west towers has been brought closer to the original delicacy, which is still shown in images from the 16th century, during the renovation, when the sturdy wheeled window from the late 18th century was replaced. The four evangelist symbols grouped around them did not exist before. The Zwerchgalerie above the west portals has only been a stone arcade based on Italian models since 1888/93. In the 16th century there was a wooden gallery with blind arcades on the back. The glittering mosaics of the ground floor arches were justified by the colorful painting of these arches in the representation of the cathedral in the upper town hall, but are unusual for outer walls of the Romanesque in Germany. The walls of the two west portals correspond to those of the north west portal before the renovation.

Sculpture decorations on the facade

Until 1888, the decoration of the double tower facade included a Coronation of the Virgin Mary (relief pair, around 1300?) And five statues of virgins (around 1230) in the gable. In the northern blind arcade of the ground floor zone there was a sculpture of a crucified Christ (around 1490), also made of stone, and in the southern one a crucified Christ from around 1400. Images from the 16th and 17th centuries show a sculpture in the gable of the then collapsed south tower , with the crucified one two minor figures, and above the base line of the portal arches and blind arcades first four (of possibly five), then three sculptures between and next to the arches. The nine surviving figures were badly weathered. They were moved inside during the restoration and replaced on the exterior between 1890 and 1894 by freely supplemented imitations. Late additions are, however: the group of the Adoration of the Magi in the gable field (as well as the Coronation of Mary by Friedrich Küsthardt ), the evangelist symbols in the window rose pendentives, and the figures between the arches: David, Moses, Charlemagne (with facial features of Kaiser Wilhelm I. ), Peter and Paul, all by Peter Fuchs . The sculptures stand on short columns that are supported by griffins or lions, these symbolize the overcoming of greed (personified by a dice player), carnal lust (buck), disbelief (destruction of the pagan Irminsul , with reference to Emperor Karl above), falsehood or Original sin (snake) and vanity (jewelry and mirror). The tympanum reliefs above the entrances represent the Lamb of God and the Last Judgment. The mosaics in the central arched fields of the blind arcades were designed in Venice by Hermann Schaper in 1899–1901 ; they take up themes that were previously sculptured at this point. For the staggered medieval figures and the bronze portals, see the Equipment section below .

Furnishing

Since the cathedral became Lutheran during the Reformation and thus did not reject images in churches as strictly as the Reformed parishes in Bremen, it still has a remarkable collection of works of art compared to other Protestant churches, including from medieval times. Nonetheless, it only represents a small part of the original furnishings, which included, for example, over 50 altars. The main works are presented in the following, sorted by material and chronology:

Early stone sculpture

- Christ enthroned

Presumably from the tympanum of a west portal comes the large, originally a semicircular relief of the enthroned Christ , which now hangs over the altar of the west crypt used as a baptistery. He is holding an open book in his left hand and two keys in his right. The figure at the bottom right, reduced in terms of meaning , is a donor figure . Christ is probably depicted when the keys are handed over to the Apostle Peter (the patron saint of the cathedral!). In any case, the two keys were included in the archbishop's coat of arms as an attribute of the patron saint. Although heavily weathered and only preserved as a fragment, perhaps even reworked, it is undisputed that it is the oldest work of sculpture in Bremen and its wider area. A more precise specification of the time of origin is of course controversial and ranges from “around 1050” to “2. Half of the 12th century ”.

- Biblical figures from the exterior facades

The five stone figures on the inner wall of the north aisle come from a series of figures of the clever and foolish virgins . It is assumed that the original location was the bridal portal on the north side, i.e. towards the cathedral courtyard, where they formed a figure portal on the sloping or stepped walls together with the remaining, lost figures and a tympanum. Remnants of the associated arch field represent perhaps the two even more heavily destroyed seated figures of a coronation of the Virgin Mary , now in the east crypt. Both groups were moved to the east crypt before 1532, perhaps at the late Gothic north side aisle extension, after the renovation around 1900, the five foolish virgins, however, later in their present-day, extremely unfavorable place for consideration. Nevertheless, despite all the loss of substance, its extraordinary quality can still be recognized. Especially on the reasonably preserved robes that flow with their fine pleats as dünnster material and below with indicated the members Kontrapost highlight just tender is to recognize that these fragments are among the most monumental sculptures of early Gothic in 1230 in Germany. They also represent the oldest figure cycle on this topic in our country.

- Cathedral mouse

The cathedral mouse is located on the right side wall of the east choir at the foot of a round arch portal from the 2nd half of the 11th century (originally an entrance portal on the outside of the old western front of the cathedral facing the market square) . In the Middle Ages, a picture of the mouse was a symbol for the unclean and the evil, which could definitely find its place in the subordinate place of the church world of images. It remains uncertain whether its function at this point was to banish the power of the devil , which was penetrating from the outside , or whether it was more the powerlessness of evil against the power of the Christian God, which should be visible in the cathedral. However, the fact that the mouse later served as a landmark, by naming traveling journeymen elsewhere to make their stay in Bremen credible, is a modern legend, for which reputable sources could not be named so far.

Sculpture around 1400

- Cheeks of the choir stalls

From Bremen sources from around 1400 we know that there were years of increased artistic activities for the cathedral, encouraged by the bourgeois builders. At the beginning of this wave are the choir stalls . From the double row of seats, originally arranged in a U-shape, which was demolished in 1823 and leaned against the walls of the choir and rood screen, at least seven side panels have been preserved, which reproduce 31 image fields from the Old Testament and New Testament and thus offer the most extensive series of medieval scenes on a choir stalls in Germany. It was completed between 1366 and 1368. Iconographically interesting is the singular case of a takeover of motifs on the six image fields depicting the public appearance of Jesus, which used corresponding miniatures from an Ottonian illuminated manuscript that was then still kept in Bremen Cathedral . Artistically remarkable are the scenes on the high cheeks with their sequence of scenes from the crucifixion of Christ to the Pentecost picture. The depictions on the lower cheeks from the history of the Maccabees have been interpreted as a political demonstration in the field of conflict between the archbishop, cathedral chapter and council.

- Crucifixes

The fragment of the Crucified on the east crypt west wall comes from the south arch field of the west facade. Because of its realistic, painfully distorted facial features and precise recording of the body modeling, it has often been assigned to the end of the 15th century, but the swaying arches of the loincloth make it necessary to classify this hitherto rather unrecognized work in the time of the Soft Style .

A second, well-preserved crucifix made of sandstone of about the same age stands on the altar of the east crypt. It is uncertain whether this altar cross comes from the cathedral, but stylistically it fits in with Bremen.

- Last supper

The ogival framed picture field with the Last Supper probably comes from the gable decoration of a sacrament niche that may have been on the north wall of the choir. Today the relief can be seen at eye level in the Cathedral Museum .

- Cosmas and Damian

There a pair of reliefs shows scenes from the lives of the medical saints Cosmas and Damian , who were highly venerated in the cathedral. After all, since 1335 they boasted that they had the complete relics of these saints , for which a golden shrine was forged around and after 1400 , which has belonged to the Michael Church in Munich since 1649 .

- Saint Dorothea

Finally, of the highest artistic rank and to be counted among the so-called Beautiful Madonnas , is the round statue of St. Dorothea , which is on permanent loan in the Focke Museum . The “most beautiful of the medieval sculptures in Bremen” was probably made in the vicinity of the Parler in Bohemia.

In terms of size and artistic importance, some of these sculptures are at least synonymous with their secular neighbors and contemporaries: the Bremen Roland and the town hall figures .

Late Gothic stone sculptures

There are hardly any sculptures in and around the cathedral from the period between 1430 and 1460. But towards the end of the century the art of sculpture continued with large ensembles and numerous epitaphs, with the clear Westphalian element of all late Gothic stone figures, epitaphs and other reliefs in the cathedral being striking. The depiction of Christ carrying the cross (now on the parish altar on the north side of the central nave by the first pillar west of the pulpit, formerly the west facade), created around 1490, comes from a Westphalian-influenced Bremen sculptor's workshop, which a little later also includes the individual figures of St. Christopher , Hieronymus , and Nicholas and St. Anna created.

In 1512 the choir screen of the west choir, from 1528 the parapet of the organ gallery, was equipped with a sculpture gallery by Evert van Roden from Münster. To the side of the group with the two cathedral founders, Bishop Willehad and Charlemagne , ten saints who are particularly venerated in Bremen are depicted: four local archbishops, next to them the saints Victor , Corona , Achatius , Quiriacus / Cyriacus of Jerusalem and others that cannot be clearly identified. A colored version from the beginning of the 20th century was removed in 1980, and the figures were wrongly set up in reverse order. The ensemble of this so-called Westlettner also originally included the individual figures of the Mother of God , St. Dionysius , St. Rochus and St. Gregory made in the same Westphalian workshop . Stylistically connected is the high relief of the holy clan in the north tower, rich in figures . Around 1525, Master Evert received the order for a relief of the baptism of Jesus based on a template from the Poor's Bible , which, like a formally similar but two decades older relief with the Annunciation, was part of a series of images for the former cathedral cloister.

painting

In the southern side chapels there are some large-format paintings. From east to west: Franz Wulfhagen : Adoration of the Magi , around 1660. - Johann C. Baese: Christ Carrying the Cross (copy after Raphael) , 19th century - Heinrich Berichau: Last Judgment , 1698. - Arthur Fitger : Entombment of Christ , 1898 and Adoration of the Kings and Shepherds, 1898. - Four passion scenes on a South German (Passau?) Altar wing, dated 1513 and signed “H. Red". - In the cathedral museum: two altar panels with flagellation of Christ and carrying the cross, Franconian , around 1490,

Bronze castings

- The baptismal font

One of the most famous pieces of equipment in Bremen Cathedral is the Bremen baptismal font . It is carried by four men riding on lions and shows 38 figures on the wall between ornamental palmette ribbons in two rows of arcades (Christ, apostles and angels above and half-figures of the prophets with banners in hands below). The bronze basin was made around 1220–1230 by a bell caster presumably from Bremen. According to the research carried out by R.Spichal, its capacity is 216.5 liters, and he suspects that it served as the urban norm for dimensions in the Middle Ages. Since the value comes close to the Bremen trade measure for liquids, an Oxhoft (in Bremen: 217.44 liters) or three Bremen grain bushels (approx. 72.5 liters each), this thesis, which has also been verified in other medieval baptismal fonts, has a lot to offer. The work was initially in the west choir of the church. After that, it saw numerous implementations. It has stood on a three-step pedestal north of the entrance since the 16th century. From 1811 it was in the first chapel in front of the choir. After the west crypt was redesigned into a baptistery, it was moved there in 1958.

- Door leaf

In the course of the major cathedral restoration, which was completed in 1909, the two west portals were given bronze doors based on models by the Cologne sculptor Peter Fuchs ; they were cast by Josef Louis, Cologne; the picture fields on the north doors (1895) depict scenes from the old , those on the south portal (1898) those from the New Testament . In both of them, a lion's head from an older door from the 13th century is embedded as a door puller, on the north door in the left wing, on the south door in the right; Modern copies have been added to the other two wings.

The Focke Museum has a door pull in the shape of a lion's head, around 1520, which was still on the north portal in 1876, and a replica from 1819 for the second wing .

- More recent bronze work

Around 1975–1980 Heinrich Gerhard Bücker made the figuratively richly decorated bronze grids around the east choir as well as the high altar and the bronze crucifix on it.

Where the Romanesque gate, which was uncovered in 1978, leads into the cloister in the south transept, inscriptions on bronze tombstones by Klaus-Jürgen Luckey have been reminding of the dignitaries of the cathedral who were newly buried here since 1986 .

Epitaphs and tombstones

Inside the nave there are almost 90 graves of bishops, archbishops and other influential church figures. Adolph Freiherr von Knigge , who is also buried in the cathedral, was the legal successor to the church administrators as the Hanoverian administrator of the Bremen cathedral district.

Unless otherwise stated, the following selection is sculptural work in stone.

The table can be sorted by columns (click on the header).

| Surname | Year of death | place | Representation, remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Three bishops? | 1053? | West crypt | Grave slab with three bishop's staff. From collective grave for the bishops Adalgar , Hoger and Reginward? |

| Johann Rode. Provost | 1477 | Cathedral Museum | Reclining figure. engraved brass grave plate |

| Johann III. Rode of whales . archbishop | 1511 | North transept | Grave slab, figurative |

| Brandis, Gerhard. Canons | 1518 | Entrance to the cathedral museum / choir staircase | Our Lady and Saints |

| Holtsviler, Johann von. Drost | 1575 | North transept | Grave slab with reclining figure in armor |

| Rantzau, Berthold. Provost | 1489 | South transept south wall | Lamentation of Christ , master of the Bentlager family relief, Münster, around 1460–1470 |

| Schulte, Friedrich | 1509 | under west gallery | Trinity , with Mary pointing to her divine motherhood |

| Oldewagen, Gerhard | 1494 | 2nd south central nave pillar | Christ before Pilate |

| Clüver, Segebade | 1547 | northern tower hall | Allegory of redemption, portrayal of the donor |

| Hincke, Joachim | 1583 | South aisle | Reclining figure, Ascension . Epitaph portal. Attribution to the Karsten Hussmann / Hans Winter workshop |

| from Sandvoort, Catharina | 1590 | South aisle | Neptune |

| Behr, Arnold | 1578 | North transept | Raising Lazarus from the dead . Attribution to the Karsten Hussmann / Hans Winter workshop |

| von Hude, Segebade | 1578 | North transept | Cross worship of the deceased. Attribution to the Karsten Hussmann / Hans Winter workshop |

| Clüver, Hermann | 1570 | South nave chapel, (5.) | Raising Lazarus from the dead. Attribution to the Karsten Hussmann / Hans Winter workshop |

| from Lith, Melchior | 1581 | South nave chapel, (5.) | Raising Lazarus from the dead. Attribution to the Karsten Hussmann / Hans Winter workshop |

| Varendorp, Ludolph. Provost | 1571 | North aisle | Brass grave plate with portrait |

| Varendorp, Ludolph. Provost | 1571 | North nave, arcade pillar | Epitaph, Last Judgment. Attribution to the Karsten Hussmann / Hans Winter workshop |

| von Langen, Ahasver | 1603 | next to the pulpit. Entombment of Christ. Attribution to Hans Winter or workshop successor. | |

| by Galen, Theodor and Judocus | 1602 | Central nave, opposite the nave altar | fragmentary double epitaph, brazen snake , standing figures of the two brothers. Attribution to Hans Winter or workshop successor. → image |

| Wippermann, Engelbert | 1621 | North aisle west wall | Christ Birth, Annunciation. → image |

| from Hasbergen, Albert | 1625 | Central nave | Resurrection , ascension, virtues. → image |

| Bocholt, Johannes. Canons | 1510 | East crypt | Crucifixion with Maria, Johannes and donor |

| Stedebargen, Meinhard. Cathedral Vicar. | 1535 | Main nave pillar | Pietà |

| Unnamed | 1480 approx. | between Querhs. and south aisle | Crucifixion with 2 donors |

| Unnamed (reredos?) | 1480–1490 approx. | East crypt | Man of Sorrows between Maria and Johannes. Westphalian workshop. |

| from Luneberge, Bernhard. Canons | 1500–1510 approx. | Under the organ gallery | Gregory Mass with a donor figure |

| Voguel, Henry | 1746 (executed in 1754) | North ship | Pelican . Sculptor: Th. W. Frese . → image |

| Vaget, Gerhard. Last abbot of the Paulskloster | 1567 | Cathedral Museum | Resurrection. Attribution to the workshop of Kirsten Hussmann / Hans Winter |

| Knigge, Adolph , writer | 1796 | South aisle, passage to the Glockenhof | Replica (1984) of an older grave slab with inscription and coat of arms |

Pulpit and altars

When the cathedral was reopened for (now Lutheran) services in 1638, the last Archbishop of Bremen, Friedrich Prince of Denmark, had the richly figured pulpit made by Jürgen Kriebel , the Glückstadt court sculptor of the Danish king Christian IV . The pulpit originally had a colored, in the Baroque period a white and gold version and in the 19th century a brown paint, which was removed around 1977. The pictorial program (apostles, prophets, virtues) is exaggerated by the risen Christ on the sound cover, victorious over evil . The pulpit has always risen from the central pillar of the northern Romanesque arcade of the main nave.

On the eve of the Reformation, the cathedral is said to have housed fifty altars. Today there are four. The main altar is simple today. The other three altars are in the two crypts and on the north side of the main nave. As already described, the altar figures are sculptures that were created for other purposes in the Middle Ages.

Stained glass window

In March 1945 all existing at that time, i. H. stained glass windows made since 1852 lost.

The rose in the west and the colored windows of the choir wall were created in 1946 by Georg Rohde from Bremen . The "Adoration of the Magi" was designed in 1953 by the German painter Charles Crodel . Several of the windows in the chapels of the south aisle were made by Robert Rabolt († 1974) from Munich, the upper clad windows and others were designed by Heinrich Gerhard Bücker .

Organs

Since 1244 there was an instruction to the cantor of the cathedral to also look after the organ . An organist was mentioned by name for the first time in 1508.

A large organ with several manuals and six bellows was installed from 1528. It was even played on special occasions in the decades when the cathedral was normally closed. In 1688 the cathedral organist, Scheele, complained about serious damage.

Between 1693 and 1698 the famous Schnitger organ with 56 registers was installed, designed by the Hamburg-based organ builder Arp Schnitger . In the 150 years of its existence the instrument has been rebuilt several times, including a. by Otto Biesterfeldt in the years 1827/28.

The cathedral received a new organ in 1847–1849. The instrument with 59 registers was created by Johann Friedrich Schulze from Paulinzella .

Sauer organ

In the course of the restoration of the westwork of Bremen Cathedral, the cathedral was given a new organ by Wilhelm Sauer in 1894 using the Schulze prospectus and the Contrabass 32 'from 1849 . A series of modifications between 1903 and 1958 led to extensive changes in the technical system and an exchange or modification / conversion of a total of 58 original Sauer registers in order to adapt the disposition to contemporary tastes with regard to the so-called organ movement . From a three-manual instrument with 65 registers, it developed through various intermediate stages to a four-manual instrument with 101 registers. A comprehensive restoration by Christian Scheffler (1995–1996) finally succeeded in reconstructing numerous registers that were removed in the meantime to reflect Wilhelm Sauer's aesthetic. In addition, the neo-Gothic prospect, which was partially destroyed in 1958, was restored and a new mobile gaming table was built on the gallery. Today the large organ on the west gallery has 98 stops.

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- (H) = existing register (historical inventory)

- (t) = partially existing, partially reconstructed register

-

Couple

- Normal coupling: II / I, III / I, IV / I, III / II, IV / II, IV / III, I / P, II / P, III / P, IV / P

- Super octave coupling: II / I

-

Game aids

- Fixed combinations (p, mf, f); Tutti; Tutti Rohrwerke; Shelf (pipe works, manual 16 ′); Single tongue storage

- Swell kicks for III. and IV. Manual; Swell kick for Vox Humana (IV)

- Crescendo roller, storage (roller, coupling from the roller, hand register)

- 2 × 256-fold setting system (lockable); Sequencer.

- Remarks

- ↑ II. Manual (for the super octave coupler II / I) expanded to a 4 .

Bach organ

On the east wall of the north transept is the neo-baroque Bach organ with 35 registers, which was made between 1965 and 1966 in the workshop of the Dutch organ builder van Vulpen in Utrecht and on February 20, 1966 with a concert by Käte van Tricht was inaugurated. It replaced the first Bach organ by the builder Wilhelm Sauer, which was badly damaged in the Second World War and was inaugurated in the cathedral on the occasion of the 26th German Bach Festival in 1939.

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Coupling : II / I, III / I, I / P, II / P, III / P

- Swell step for Borstwerk

Wegscheider choir organ

The cathedral's newest organ is a single-manual choir organ from the Dresden organ workshop Wegscheider from 2002, which is used for the musical design of weddings, communion services and other events in the cathedral's high choir. The construction of this organ, which is located in the choir on the north side to the left of the altar, was made possible by a foundation from Ingeborg Jacobs, the widow of the Bremen company founder Walther C. Jacobs.

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Pairing : I / P

Silbermann organ

In 1939 the cathedral parish from Dresden acquired a historic Silbermann organ with eight registers. It was originally created between 1734 and 1748 under the direction of organ builder Gottfried Silbermann for the church in Etzdorf , Saxony , and received a pedal in 1796. Since 1865, she stood in the church of Wallroda . It was bought by the Dresden organ builder Eduard Berger in 1902. Subsequently, the organ was in different private hands for 37 years and was rebuilt several times before it was discovered by Richard Liesche and Käte van Tricht in Dresden in 1939 and transferred to the Bremen Cathedral.

Here it was initially in the west crypt, was moved to the east crypt during the war and is now back in its old place in the west crypt. In 1994 the Dresden organ workshop Kristian Wegscheider restored the instrument and, in addition to removing the pedal that was added later, restored the pitch, tuning and intonation that had been modified in the meantime. It is one of 32 Silbermann organs still in existence.

At the same time Wegscheider made a copy of the instrument, which has been in the Gottfried Silbermann Museum in Frauenstein in the Ore Mountains since 1994 .

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Klop organ

In April 2001 the cathedral received a two-manual organ built by Gerrit Klop in 1991 in the Dutch organ workshop . The Klop organ is on permanent loan from private property and is located in the east crypt under the choir. In the style of the Italian Renaissance it has exclusively wooden registers as “organo di legno”.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The organists at Bremen Cathedral included Käte van Tricht (1933–1974), Richard Liesche (1930–1957), Hans Heintze (1957–1975), Zsigmond Szathmáry (1976–1978) and Wolfgang Baumgratz (1979–2013). Stephan Leuthold has been organist at St. Petri Cathedral in Bremen since 2014 .

Bells

The cathedral had at least eight bells in the Middle Ages. Of these, only Maria Gloriosa from 1433 has survived. Some were destroyed by the collapse of the south tower in 1638.

At the end of the 19th century, the Bremen Cathedral received its present form. Since that time, three generations of Otto bells have shaped the bell sounds of the cathedral alongside the medieval Gloriosa bell by Ghert Klinghe. From 1893 to 1896 the F. Otto company supplied five bells for St. Petri Cathedral, including the 1st Brema. In 1925 Otto delivered the second generation of bells consisting of three bells, including the 2nd Brema. With the exception of the 1st Brema, these Otto bells fell victim to the confiscation of bells during the two world wars. In 1951 Otto cast two new bells for the Bremen Cathedral and in 1962 the 3rd Brema. The cathedral parish was not very lucky with the Brema bells, which are the largest in the peal of the cathedral. The 1st Brema got a crack in 1919 and had to be re-cast. The 2nd Brema was destroyed in World War II. The 3rd Brema also got a crack in 1972 and had to be repaired at great expense.

The current inventory includes four bells:

|

No. |

Surname |

Casting year |

Foundry, casting location |

Mass (kg) |

Chime |

tower |

| 1 | Brema | 1962 | Bell foundry Otto , Bremen | 7112 | g 0 + - 0 | South tower |

| 2 | Maria Gloriosa | 1433 | Ghert Klinghe, Bremen | h 0 + - 0 | North tower | |

| 3 | Felicitas | 1951 | Bell foundry Otto, Bremen | d 1 +2 | ||

| 4th | Hansa | 1951 | e 1 +2 |

The medieval bell "Maria Gloriosa"

The bell from 1433 is the work of the Bremen bell founder Ghert Klinghe . It bears several inscriptions. The first is written in Latin and reads:

- cvm strvctvarivs meynardvs no (m) i (n) e / dictvs hic opvs ecc (lesia) e respexit / tractvs amore petri clavigeri vas fecit hoc fieri

- (When the builder Meinard - that's his name - was overseeing the building of the church, he had this vessel made out of love for the key bearer Peter.)

Below these lines is a poem rhymed in Low German :

- + gloriosa anno domini mccccxxxiii / master ghert klinge de mi ghoten hat / ghot gheve siner sele rat / in de ere sunte peters kosme unde damian / ghot late se long to eren loew ghan / jhesus pc maria

- (+ Gloriosa. In the year of the Lord 1433. Master Ghert Klinghe, who watered me, God give his soul advice, in honor of St. Peter, Cosmas and Damian, God let them go to their praises for a long time. Jesus pc (?) Maria.)

The old bell from Ghert Klinghe is traditionally called Maria Gloriosa in Bremen. This is due to an incorrect reproduction of the bell inscription. The bell inscription correctly begins as follows: + GLORIOSA ANNO DOMINI ... and ends with the name of the Mother of God Maria, but not with the word Gloriosa.

In addition to the inscriptions, the Maria Gloriosa is decorated with biblical scenes on the wall. For example, the Annunciation and the crucifixion group with the Saints Cosmas, Damian , Maria Magdalena and Simon Peter are depicted.

Newer bells

In 1951, a native of Bremen who emigrated to the United States donated the purchase of two new bells for the north tower to the main church in his old hometown. They were given the names Hansa and Felicitas . Both bells were cast in the Otto bell foundry in the Hemelingen district of Bremen . The inscriptions are strongly influenced by the horrors of the war, which were not so far back then. The Hansa bears the inscription:

- VERBUM DOMINI MANET IN AETERNUM - ANNO DOMINI MCMLI

- (The word of the Lord remains for ever - In the year of the Lord 1951)

and Felicitas said:

- DONA PACEM DOMINE IN DIEBUS NOSTRIS - ANNO DOMINI MCMLI

- (Grant us peace, Lord, in our time - In the Lord's year 1951)

Twelve years later, in 1962, a merchant family from Bremen donated a new casting of the Brema bell that was formerly in the cathedral . Like its predecessors from 1894 and 1925, this was also manufactured in the Otto brothers' bell foundry. It is the largest bell in Bremen Cathedral, weighs around seven tons and hangs alone in the south tower. Cracks in the suspension made it necessary to shut down for several months in 2008. After repair work, the Brema could be rung again on May 25 of the same year. The inscription on the bell reads:

- BREMA / LOST IN WAR AND EMERGENCY / CREATED NEW EASTER 1962 / TO HONOR THE DEAD / TO ADMN THE LIVING. BE TRUE UNTIL DEATH / HOW I WILL GIVE YOU THE CROWN OF LIFE.

The first Brema , cast in 1894 from two cannons donated by Kaiser Wilhelm II, burst in 1919. It bore the inscription:

"

My name is Brema, I praise God, my ore was captured in the war,

peace celebrations are ringing

, and everyone who hears me will be given

peace in their hearts."

Ringing order

The Hansa , Felicitas and Maria Gloriosa are rung for the regular Sunday service, this is also the case at the noon and evening bells, the exception being Friday, when the Brema rings as a soloist. The plenum takes place on special holidays. The quarter- hour strike is on the Hansa , the hour strike on the Maria Gloriosa .

City bell

The nearby medieval Martini Church was also able to replace its bells, which had been destroyed by metal donations and war, by 1962 and matched the tone sequence to the cathedral bells. At the inauguration on July 18, 1962, the bells of the cathedral and Martini church rang together with ten voices. The so-called old town bell is nowadays one of the most beautiful in Germany and has the following tone sequence:

| church | Dom | Dom | Martini | Dom | Martini | Dom | Martini | Martini | Martini | Martini | Martini |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chime | g 0 | h 0 | c 1 | d 1 | d 1 | e 1 | f 1 | g 1 | a 1 | c 2 | d 2 |

Building organization

Civil building management in the late Middle Ages

Despite all the conflicts of interest between the archbishopric and the city, it must not be forgotten that there was a high degree of civic identification with the cathedral as a building and an urban location. In the later Middle Ages, the fabrica ecclesiae was more than just a building works ; as a building itself, to use a modern term, it almost had the quality of a legal person. Its head ("buwmester") was mainly taken from the ranks of the council in the late 14th and 15th centuries. This lay guardianship corresponded to the concern for securing the building's own property against unauthorized use. An important holder of this office was the cathedral builder and temporary mayor Johann Hemeling around 1400 .

Bremen cathedral builder

Cathedral builders were and are responsible for the construction and maintenance of domes; formerly mostly in cathedral huts . Below are some well-known Bremen cathedral builders:

- Cordt Poppelken , builder from 1502 to 1522, built the late Gothic north nave and rebuilt the west crypt

- Johann Wetzel , since around 1830

- Max Salzmann , since around 1888

- Ernst Ehrhardt , from 1897 to 1901

- Walter Görig , since around 1930

- Friedrich Schumacher , from around 1960 to around 1980

Cathedral parish

Church leadership

The highest decision-making body of the St. Petri-Domgemeinde is the church convention. This is made up of permanent and elective members. The builders , preachers, full-time church musicians and a total of 36 deacons and old deacons are constantly represented in the convent . The freely selectable places, for which every community member can apply, are allocated for a four-year period; however, there is a possibility of re-election. In 1999, the church convention adopted a constitution that outlines its area of responsibility: The body is responsible for the choice of builders from among its members, the election and appointment of preachers, and the election of the members of the church council. All decisions made by the financial administration in the cathedral chancellery regarding the budget, the position planning or the annual accounts require the approval of the Convention. In addition, only this person is able to fundamentally change the order of worship. The convention is allowed to set up working groups and committees consisting of its members to provide advice on various topics.

Well-known cathedral preachers and superintendents

in chronological order

- Albert Hardenberg (around 1510–1574), theologian and reformer, cathedral preacher from 1547 to 1561

- Simon Musaeus from 1561 to 1562 Superintendent Bremen

- Marcus Meinecke (1520–1584) Superintendent Bremen from 1571 to 1584

- Christoph Pezel (1539–1604) Superintendent Bremen from 1584 to 1604

- Daniel Lüdemann (1621–1677) Superintendent Bremen 1652 to 1672, then General Superintendent Bremen and Verden

- Simon Hennings , 3rd preacher 1654 to 1661

- Bernhard Oelreich , superintendent from 1673 to 1686

- Jacob Hieronymus Lochner (1649–1700), superintendent before 1700.

- Gerhard Meier (1664–1723), from 1701 or 1702 to 1723 superintendent

- Christoph Bernhard Crusen (1676–1744), pastor and superintendent from 1725 to 1744

- Johann Vogt (1695–1764), cathedral preacher from 1719

- Wolbrand Vogt (1698–1774), cathedral preacher from 1746

- Johann Georg Olbers (1716–1772), cathedral preacher from 1760

- Johann Gotthard Schlichthorst (1723–1780), cathedral preacher from 1765, 1775 to 1780 pastor, primary surgeon and superintendent

- Johann David Nicolai (1742–1826), 1771–1781 sub- rector or rector of the Athenaeum, cathedral preacher since 1781, pastor primarius from 1810 to 1826

- Adolph Georg Kottmeier (1768–1842), cathedral preacher

- Oscar Mauritz (1867–1959), assistant preacher from 1889 to 1892, cathedral preacher from 1897, pastor primarius from 1915 to 1946

- Otto Hartwich (1861–1948), cathedral preacher from 1909 to 1934

- Erich Pfalzgraf (1879–1937), cathedral preacher from 1914 to 1937

- Heinz Weidemann (1895–1976), cathedral preacher from 1926 to 1944 and from 1934 regional bishop of Bremen, member of the NSDAP from 1933 to 1943

- Maurus Gerner-Beuerle (1903–1982), cathedral preacher from 1946 to 1971

- Günter Abramzik (1926–1992), cathedral preacher from 1958 to 1992

- Ortwin Rudloff (1930–1993), cathedral preacher from 1971 to 1993.

- Peter A. Ulrich (* 1953), cathedral preacher since 1992

Church life

The Bremen Cathedral now offers about 1,600 seats to believers. Church services with baptisms take place every Sunday from 10:00 a.m., often with the Lord's Supper . Times may vary on religious holidays. The church services are led in alternating rotation by the currently six pastors of the congregation. Playing on the Sauer organ and the songs of the cathedral choir are essential components of every service in the cathedral. As in every other church, confirmations, church weddings and funeral ceremonies take place in the cathedral.

The Thomas Mass is celebrated in the cathedral on the last Sunday of each month from 6 p.m. It represents an alternative to the otherwise often stipulated course of a church service and, according to its own description, is aimed at questioning Christians, doubters in faith, frustrated churchgoers, worshipers grumpy . The name of this service commemorates the apostle Thomas , also known as the unbelieving Thomas. The Thomasmesse is ecumenically oriented and focuses on modern church music, meditation and alternative teaching of faith. For example, the readings and sermons are designed by both clergy and laypeople and dialogues and role play are initiated.

The cathedral is freely open to tourists, but guided tours are also offered.

In addition to the main church in downtown Bremen, the cathedral community also has the St. Petri Cathedral Chapel at Osterdeich No. 70a in the Peterswerder district ( Eastern suburb ). Worship services and baptisms are also held there. In addition, at irregular intervals it is the venue for the family services, which are specially intended for smaller children.

Church music

Church music has a long tradition in the Bremen cathedral community. For example, the first cathedral choir was founded in 1685 by the cantor Laurentius Laurentii . According to evidence, this had nine members in 1732. The choir financed itself through performances at family celebrations and was initially only poorly supported by the community itself, although some cantors, such as Wilhelm Christian Müller , tried to increase its popularity. The choir was re-established in 1856 and public concerts began the following year. The work Ein deutsches Requiem by Johannes Brahms was premiered here in 1868 . Nowadays the choir prepares around six to eight large concerts a year. These are often broadcast by broadcasters. Also, the choir has been several records and CDs published of which A German Requiem with the Prize of the German Record Critics' Award. The cantors of the cathedral choir include:

- Laurentius Laurentii (from 1684)

- Wilhelm Christian Müller (1784-1817)

- Carl Martin Reinthaler (1858-1893)

- Eduard Nößler (from 1893)

- Richard Liesche (1930–1957)

- Hans Heintze (1957–1975)

- Wolfgang Helbich (1976-2008)

- Tobias Gravenhorst (since 2008)

The cathedral's tower blowers , which have existed in Bremen since at least 1737, are also known throughout the city . Every Sunday after the service they blow trumpets, chorals, quartets, fugues and folk songs from the viewing platform of the south tower. During the Christmas season, they don't just play on Sundays. The tradition of the tower blowers threatened to go under in Bremen just a few years ago because the financing was unsecured, but since about 2006 the concerts have been taking place regularly again.

In addition to the oratorical performances of the choir, an average of 50 other concerts and performances take place each year, which are more instrumental. In addition, small demonstrations of organ, chamber or choral music are offered every Thursday with free admission . In 1983, the then cathedral cantor Wolfgang Helbich initiated the so-called "NIGHTS". These five-hour mixes of choral music, symphonic works and chamber music are each dedicated to a particular composer, take place each time in a different area of the nave and are mostly broadcast by Radio Bremen .

There is the Bremen Cathedral Singing School at the cathedral to promote young musicians .

Diakonia

The diakonia founded in 1638 still exists. It currently (February 2008) has 24 members. They have committed themselves to volunteer for the church and the community for twelve years.

Affiliated facilities

Cathedral schools

Throughout history there have been two church schools attached to the cathedral. In 1642 a Lutheran Latin school, the cathedral school , was founded, which competed with the reformed Latin school, the pedagogical museum from 1528 in the Katharinenkloster. The school building was located in the Kapitelhaus on Domsheide immediately south of the cathedral. For the institute, which usually had six teachers, school regulations were issued in 1648 and in the same year the school and the cathedral fell to Sweden and from then on were subject to a consistory . The professors or teachers, who previously had to work additionally in church service, have now been released from this activity. The teaching staff included the rector, the vice-rector, the sub-rector, a collaborator , a cantor for music lessons and, from 1683, a grammar school .

In 1681 the Athenaeum was established . This was a department for students who had previously attended Latin school - practically the secondary upper level. This also took place in competition with the reformed grammar school illustrious of 1610. At first only a few students visited the Athenaeum, but it was praised for its outstanding library. In 1718 both institutes became Hanoverian and in 1726 the Athenaeum had 89 students. After it was returned to the city of Bremen in 1803, it was placed under a scholar . The school has since been referred to as the Lyceum and the number of students rose to 170. In 1817 the Lyceum was incorporated into the so-called Hauptschule .

Another cathedral school also existed in the chapter house from the 16th century. The majority of the students came from Lutheran families. In 1874 they moved to the converted pastor's house at Marktstrasse number 14, but only six years later, in 1880, this cathedral school became part of a paid state elementary school.

Cathedral library

As Bremen's most important book collection of the Middle Ages, numerous manuscripts were available in the cathedral library for the liturgical needs of the clergy and for scholarly studies at the cathedral school. They suffered an eventful fate. Adam von Bremen reports that the cathedral fire of 1041 also destroyed the library. Under Archbishop Hartwich I, the inventory grew again considerably, probably also due to the work in the cathedral scriptorium . Some famous manuscripts are to be found in the great libraries of the world today: The Dagulf Psalter from the court school of Charlemagne in the Austrian National Library in Vienna, its ivory cover panels in the Louvre , the pericope book of Henry III. in the Bremen State and University Library , another Echternach evangelist in the Bibliothèque Royale in Brussels, three 11th century evangelists in the John Rylands University Library in Manchester , the Munich State Library and the State Museum of Lower Saxony, as well as the "Great Lombard Psalter" and others Manuscripts from the 12th to 15th centuries in the Bremen State Library.

Cathedral Museum

→ see also the main article Dom-Museum (Bremen) , in particular on the excavations.

The cathedral museum was inaugurated in 1987 and has since served primarily to display items that were recovered during the archaeological excavations from 1973 to 1984. In the ecumenical museum, however, other liturgical objects from past centuries are also shown, including items on loan from the Bremen Catholic Church. In 1995 the museum was expanded, the costs of which were funded by the Bremer Dom e. V. were worn. During renovation work in a room, medieval wall paintings were discovered by chance, which are among the most extensive preserved in Bremen and were probably created shortly before the altar consecration of this former chapel in 1414.

Bible garden

The in homeland security style rebuilt courtyard of the concert hall bell (instead of 1925 torn medieval cloister ) measures 37 m × 13 m and was 1998 as Biblegarden planted. In addition to 60 different types of plants, all of which are mentioned in the Bible, it is also home to traditional plants from monastery gardens, including Aaron's staff , lilies and wheat . The garden is tended by the “Bible gardeners” and is open to the public. Guided tours are offered once a month. In the garden there are some benches that are meant to invite you to linger in the green. On the central lawn is a copy of a statue of a former Jakobi fountain in Bremen with a shell on the base that marks the Way of St. James .

particularities

Lead cellar

Lead cellar is the colloquial name of the east crypt. The name lead cellar came about because lead was stored there for roof and window repairs. He is best known for the fact that some mummies were found here. They were discovered by chance around 1698 by the journeymen of the organ builder Arp Schnitger , who had been assigned the east crypt as a work space. The cause of mummification is the rapid drying out of the buried due to the air permeability of the underground; this has nothing to do with the effects of lead. Since their discovery, a total of eight lead cellar mummies, some of which are known by name, have been exhibited in open coffins, initially at the site of the discovery and later, after the east crypt was rented out as a storage room, in the coal cellar. After the archaeological excavations in the second half of the 20th century, the mummies had to move again, this time to the cellar of a cathedral building at the Bible Garden, because the cathedral museum was housed in the coal cellar. The name lead cellar was transferred to the exhibition location.

Replica

Bremen Cathedral was used as a model for the first new Catholic church in Hamburg after the Reformation, the New Mariendom , which was built in 1893 . In 1995 it was elevated to a cathedral as a bishopric for the new Archdiocese of Hamburg.

See also

- Diocese of Bremen

- Bremen church history

- Bremen Evangelical Church

- Parish hall of the cathedral parish

- Cathedral Museum

literature

- Karsten Bahnson : The St. Petri Cathedral in Bremen. 10th edition. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin Munich 2006.

- Johann Christian Bosse, Hans Henry Lamotte : The Bremen Cathedral . Recordings by Lothar Klimek . (= The Blue Books). 2nd, revised edition. 1998, ISBN 3-7845-4231-X .

- Karl-Heinz Brandt: Excavations in the Bremen St. Petri Cathedral 1974-1976. A preliminary report. Bremen 1977.

- Georg Dehio: Handbook of the German art monuments - Bremen Lower Saxony . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 1992, pp. 6-14.

- Reinhard Karrenbrock: Westphalia-Bremen-Netherlands, Westphalian sculptor of the late Middle Ages in Bremen. In: Bremen and the Netherlands. 1995/96 yearbook of Wittheit zu Bremen, Hauschild, Bremen 1997, pp. 40–61.