Main building of the University of Vienna

The central building of the University of Vienna is its main building in the 1st district . The front is located on the university ring, which has been known as the university ring since 2012 . The building designed by Heinrich Ferstel was built between 1873 and 1884.

history

prehistory

The medieval university was housed in various buildings in the parlor district of the historic old town of Vienna . Her first house was the Herzogskolleg , which opened in 1385, at today's Postgasse 7–9. After the Jesuit College was incorporated into the university in 1623, the early Baroque Jesuit College was built on the same site. With the university church and some additions, it is still preserved today as the old university and houses, among other things, the archive of the University of Vienna .

From 1753 to 1755 Maria Theresa had a new main building, the "New Aula", built right next to the Jesuit college. The auditorium was the central meeting place during the revolution of 1848 . After the violent suppression of the revolution, the university was occupied by the military. The students were driven from the old town; the building was given to the Academy of Sciences in 1857 .

Studies now took place in temporary alternative quarters: the medical faculty was housed in a former rifle factory at Währinger Strasse 13 in the 9th district (today the "Anatomical Institute"). The juridical, philosophical and theological lectures were held in the former Piarist town convict in the old town. The chemical laboratory was housed in the Theresianum in the 4th district , and numerous institutes were located in Erdberg , a part of the 3rd district further away from the city center.

Planning on the Alsergrund

In 1854, Minister of Education Leo von Thun und Hohenstein planned the construction of a new university building on Rossauer Glacis , at the beginning of Währinger Strasse or today's Günthergasse in what is now the 9th district. Thun commissioned the architects Sicardsburg and van der Nüll to design the new building, which was then decided in 1855.

The medical faculty found the location attractive because it was conveniently close to what was then the General Hospital . In the meantime, however, the building site for the Votive Church , a project by the Emperor's brother Ferdinand Maximilian , had been marked out, and this building project, which began in 1856, was now in the way of the university. Sicardsburg and van der Nüll redesigned and planned a university building behind the choir of the Votive Church. The style was based on the Gothic to fit the Votive Church.

At the end of 1857, Franz Joseph I decided to leave the city wall around the old town and to build the Vienna Ringstrasse around the old town ; a project that took many years to complete. Independently of this, the plan for the new university building near the Votive Church and its immediate implementation were decided in 1858. In 1859 construction could not be started because of the war in northern Italy , and in 1860 Thun left the government, which brought the project to a standstill.

The project was increasingly criticized. Heinrich Ferstel in particular protested violently against the fact that a second monumental building should compete with his votive church. In contrast, the Alsergrund district council fought for the prestigious project in their district. Years of discussion were the result. During these years the plans changed often. The university was at times planned as a single building, then again as a campus of several buildings based on the English model. The Chemical Institute at Währinger Strasse 10 was the only building on this campus to be built by Heinrich Ferstel from 1869–1872.

The construction of the University on the Ring

The situation changed fundamentally after the emperor approved the abandonment of the large parade and parade ground near the old town, which the city administration had long demanded. In the winter of 1868/69, Mayor Cajetan Felder gave birth to the idea of having three monumental buildings erected on the parade ground, the parliament, the town hall and the university. The plan was immediately appreciated. It was immediately decided that Theophil Hansen would build the parliament and Heinrich Ferstel the university.

However, there was also resistance. Although there was now a lot of space available at the parade site, several faculties wanted to hold onto the location on Alsergrund - the medical professionals in particular felt at home in the former rifle factory. Architect Ferstel had always opposed a monumental building next to his votive church; now that he was allowed to build the university himself, his protests became even more violent.

Finally, Franz von Matzinger , the head of the Vienna City Expansion Fund , finally succeeded in enforcing the new location on Ringstrasse, namely where the Franzensring (after several name changes, this section has been called the Universitätsring since 2012 ) in front of the Schottentor (today a traffic junction next to the university ) shows a marked change of direction, in sight, but without a direct connection with the Votive Church. The building site was delimited by the Ring, Rathausplatz , Reichsratsstrasse and Universitätsstrasse .

After Ferstel's construction plans were published, the university management was pleasantly surprised by the size of the building; above all, the entire university library could now be accommodated in the main building.

On July 25, 1870, during the term of office of kk Prime Minister Alfred Józef Potocki, the final decision was taken to build the university on the Ring. In the spring of 1871 Heinrich Ferstel went on a study trip to Italy, during which he mainly visited the universities of Bologna , Padua , Genoa and Rome . Up to the summer of 1872 countless negotiations and meetings took place in which the individual faculties announced their space requirements, which then had to be coordinated by Ferstel.

The project was finally assessed by the architect Gottfried Semper . Semper's expertise was basically positive, although he made some suggestions for improvement. Taking these suggestions into account, Emperor Franz Joseph I granted his approval on July 29, 1872. At the same time, the emperor approved 7 million guilders from state assets for university building. At that time, the kk Hofopertheater on Ringstrasse had already opened, but the construction of the kk Hofburgtheater had not yet started. The Art History Museum and the Natural History Museum , the two large court museums on the Ringstrasse, had been under construction for a year. Construction of the nearby Votive Church began in 1856, but lasted until 1879.

Construction work began a year later, on July 14, 1873. The laying of the foundations turned out to be very difficult. The Mölker Bastei once extended directly in front of the university ; the area was criss-crossed by old mine tunnels from the time of the Turkish wars.

Exactly ten years to the day after construction began, on July 14, 1883, Heinrich Freiherr von Ferstel died in his summer apartment in what was then the Viennese suburb of Grinzing . His long-time employee and brother-in-law Karl Köchlin (1828–1894) and his son Max von Ferstel took over the construction. A year later, the building was largely completed, on October 10, 1884 the university was ceremoniously opened in the presence of the emperor. The decorative design took years to complete. The total costs up to 1890 amounted to 7,633,186 guilders (approx. 67 million euros).

The building

As a homage to the first heyday of science in Europe, Ferstel had chosen the Italian High Renaissance style for the building , with the universities of Padua and Genoa as the inspiration. The building complex has a large arcade courtyard (50 × 40 meters) and eight smaller courtyards, the main facade with its access ramp is structured by protruding corner projections and the elevated central section. The eye-catcher on the Ringstraße is the prominently protruding columned hall. In the gable, a relief depicts the birth of Minerva , the goddess of wisdom.

The area of the main building covers 21,412 m², of which 14,530 m² are built up. The university library with the large reading room is located at the rear of the building on Reichsratsstrasse . Since the library has no windows, the wall along Reichsratsstrasse was decorated with sgraffiti . The Auditorium Maximum was not built until the 1930s; With 751 seats it is the largest lecture hall in Austria.

The main building of the University of Vienna has repeatedly been the focus of political disputes. In the interwar period, the local National Socialists, who had tightly organized and well-equipped party formations , also made themselves felt at the university. Student riots took place in front of the university in 1928 and 1932. Taras Borodajkewycz, who was right-wing radical in the 1960s, worked here in the 1930s. In 1936 the German philosopher Moritz Schlick was murdered by one of his former students on a staircase in the main building. The Siegfriedskopf, which was erected in the auditorium in 1923 by anti-Semites and anti-democrats and only moved to a less prominent location in 2006, was the subject of discussions about its ideological background.

Today the main building houses the following facilities:

- 2nd mezzanine floor : Institute for German Studies

- 2nd floor : seminar and practice rooms, German studies departmental library, Institute of History, historical sciences department, Catholic-Theological Faculty, Evangelical-Theological Faculty

- 1st mezzanine floor : international relations, public relations, personnel administration, institute for economic and social history

- 1st floor : University library, directorate, Institute for Austrian Historical Research, Institute for History, Faculty of History and Cultural Studies, Faculty of Philological and Cultural Studies, small ballroom, large ballroom, Senate hall

- Raised ground floor : auditorium, arcade courtyard, textbook collection, internal auditing, finance and controlling, personnel administration, Institute for Classical Philology, Institute for Ancient History and Classical Studies

- Lower ground floor : Audimax, admission to study, Institute for Scandinavian Studies, Institute for Dutch Studies

The main building is very easy to reach via the directly adjacent Schottentor underground station and ten tram lines stopping there. A large underground car park is available under the square for private transport.

The immediate building neighbors include the Hotel de France , the former main building of the Creditanstalt-Bankverein , the Palais Ephrussi , the former OPEC building (Universitätsring 10) and the Pasqualati house on the Mölker Bastei with a Beethoven memorial.

The arcaded courtyard

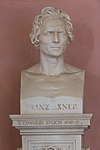

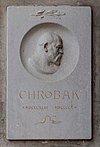

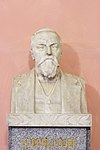

Heinrich von Ferstel wanted the large, central arcaded courtyard to be understood as the heart of the complex. From here you can reach all the important stairs. In 1885 the Academic Senate stipulated that deserving professors could posthumously be honored with a memorial in the arcade courtyard, at the earliest five years after their death (this period has now been increased to 15 years). Only in the case of the anatomist Josef Hyrtl was a monument erected during his lifetime.

The university was not allowed to cost anything to put up the busts or monuments. The rectorate examined and approved the drafts, but they were financed by relatives, students or associations. The first bust in the arcade courtyard was that of the lawyer Julius Glaser in 1888 ; she had been paid by his family. By 1918, 78 monuments were erected, between 1918 and 1945 28 monuments, and since 1945 48 monuments, a total of 154. In addition, there are some older monuments in the arcade courtyard that originate from other buildings.

The most prominent representatives of the Ringstrasse era can be found with regard to the sculptors who carried out the work: Caspar von Zumbusch created nine monuments in the Arkadenhof, Carl Kundmann seven, and Hans Bitterlich six. Almost all monuments are busts, only the statue of Education Minister Leo von Thun and Hohenstein is full-length.

In 1938, National Socialist students began to knock over or smear some of the busts. The rector then had the monuments of 18 Jewish scholars moved to a depot in the cellar. They survived the war undamaged and could be put up again in 1947.

The writer Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach is honored with a text plaque. Although she was neither a scientist nor taught at the university, she was the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Vienna. Two of the busts, namely those of Wilhelm Emil Wahlberg and Heinrich Siegel , were designed by a woman, namely Melanie Horsetzky von Hornthal (1852–1931).

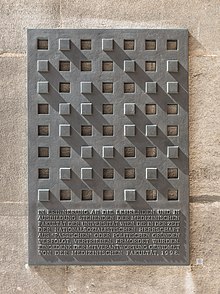

In 1998, a memorial plaque was unveiled in memory of the members of the medical faculty who were displaced between 1938 and 1945. The bronze wall memorial was designed by Günter Wolfsberger (* 1944).

In June 2016, seven researchers were honored with monuments in the Arkadenhof of the University of Vienna: Charlotte Bühler , Marie Jahoda , Berta Karlik , Lise Meitner , Grete Mostny , Elise Richter and Olga Taussky-Todd .

List of monuments in the arcaded courtyard

The order of the monuments corresponds to a clockwise tour through the arcaded courtyard.

literature

- Norbert Wibiral, Renata Mikula: "Heinrich von Ferstel". Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1974. ISBN 3-515-01928-6 . Volume VIII, 3 by Renate Wagner-Rieger (Ed.): “The Vienna Ringstrasse. Picture of an Era (Volume I – XI). “Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1972–1981. ISBN 978-3-515-02482-2 .

- Kurt Mühlberger (Ed.): “The University of Vienna. Brief glimpses of a long history. ”Holzhausen, Vienna 1996, ISBN 3-900518-45-9 .

- Kurt Mühlberger, University of Vienna (Ed.): “Palace of Science. A historical walk through the main building of the Alma Mater Rudolphina Vindobonensis [University of Vienna]. ”Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2007, ISBN 978-3-205-77619-2 , parallel edition in English:“ Palace of Knowledge. A historical stroll through the main building of the Alma Mater Rudolphina Vindobonensis. "Translated by Camilla R. Nielsen and J. Roderick O'Donovan, ISBN 978-3-205-77807-3 .

- Thomas Maisel, University of Vienna (ed.): “Scholars in stone and bronze. The monuments in the arcade courtyard of the University of Vienna “Böhlau, 2007, ISBN 978-3-205-77616-1 .

- Julia Rüdiger, Dieter Schweizer (Ed.): “Places of Knowledge. The University of Vienna along its buildings 1365–2015 “Böhlau, 2015, ISBN 978-3-205-79655-8 .

Web links

- www.univie.ac.at Official website

- u: monuments The monuments in the arcade courtyard of the University of Vienna

- www.studentpoint.at Advisory center at the University of Vienna

- www.dieuniversitaet-online.at Online newspaper of the University of Vienna

- Project Phaidra digital long-term archiving of the University of Vienna

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kurt Mollik, Hermann Reining, Rudolf Wurzer: “Planning and Realization of the Vienna Ringstrasse Zone”. Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1980. ISBN 3-515-02481-6 . Volume III by Renate Wagner-Rieger (Ed.): “The Vienna Ringstrasse. Picture of an Era (Volume I – XI). “Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1972–1981. ISBN 978-3-515-02482-2 .

- ↑ Barbara Dmytrasz: The Ringstrasse - A European Building Idea , Amalthea Signum Verlag, Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-85002-588-1 . P. 96 ff.

- ↑ Bundespolizeidirektion Wien (Ed.): 80 Years of the Vienna Security Guard , Verlag für Jugend und Volk, Vienna 1949, p. 52.

- ↑ Bundespolizeidirektion Wien (Ed.): 80 Years Wiener Sicherheitswache , Verlag für Jugend und Volk, Vienna 1949, p. 63.

- ↑ orf.at - Seven women's monuments for the University of Vienna . Article dated October 28, 2015, accessed October 28, 2015.

- ↑ derStandard.at - Arkadenhof of the University of Vienna now also houses women's monuments . Article dated June 30, 2016, accessed July 1, 2016.

- ↑ orf.at - women in the arcade courtyard of the University of Vienna . Article dated June 30, 2016, accessed July 1, 2016.

- ↑ This bust was only temporarily erected, see description on monuments.univie.ac.at

Coordinates: 48 ° 12 ′ 47 " N , 16 ° 21 ′ 35" E