Science fiction

Science fiction [ ˌsaɪəns ˈfɪkʃən̩ ] ( English science : science , fiction : fiction ) is a genre in literature ( prose , comic ), film , radio play , video game and art . Characteristic are scientific and technical speculations , space travel topics, distant future, foreign civilizations and mostly future developments.

The spelling science fiction (less often science fiction ) is also used. Common abbreviations are Sci-Fi or SciFi ([ saɪ̯faɪ̯ ], also [ saɪ̯fɪ ]) and SF .

Synonyms and delimitation

Synonyms are science fiction , -literatur, -film, Scientific Fantastik (ehem. GDR loan translation from Russian Научная фантастика).

Related areas that do not belong to the SF are utopian literature as well as fantastic literature (not to be confused with fantasy or romantic fantasy ). The authors Heinlein , Haldeman and Robinson used the term speculative fiction for non-scientific-technical literature .

development

The term was first introduced in 1851 by the British poet and essayist William Wilson (approx. 1826-1886) in the heading of chapter 10 of his book A little earnest book upon a great old subject as "science fiction" and, according to the writer Felix J. Palma in his book the Geography of time, from the Luxembourg-American inventor, writer and publisher Hugo Gernsback in April 1926 in his magazine Amazing Stories used as "scientifiction" and in 1929 in the final form "science fiction" as a genre designation established . In August 1923 he had already published a special issue of his magazine "Science and Invention" as Scientific Fiction Number. In 1929 the loan word science fiction was used in advertisements for Air Wonder Stories magazine . The abbreviation sci-fi is from 1955.

The salvation of man is seen in natural science and its application dimension, technology. In the 19th century, fear of science and technology arises parallel to belief in science. This belief and this fear merge into the epoch-making new and divided attitude to life of being a neo-mythical titan who is afraid of his own power. This is why dystopias arise , such as those in Aldous Huxley and George Orwell . This ambivalence shapes science fiction, which is particularly dedicated to describing the effects of technology on people and the utopian-futurological extrapolation of its effects. Some post-structuralist authors like Samuel R. Delany argue that indefinability is an essential feature of science fiction. In the theoretical discussion, it is unclear whether science fiction is a genre or a genre , i.e. whether it can be defined by a relatively fixed set of formal, content-related or structural elements or whether science fiction should be more appropriately described as a mode that describes the nature of the respective fictional world on a more fundamental level than that of a genre. Delany even sees literary science fiction as having its own linguistic form of expression, which, like poetry, must be read differently than normal narrative literature.

Science fiction is not on the scene of action defined. This means that a story does not necessarily belong in the genre of science fiction just because it takes place in the future or in space.

Differentiation from fantasy

Science fiction is usually different from fantasy . Fantasy is always when the phenomena narrated have no relation to a (natural) scientific consideration and instead use elements from fantastic literature . If the two are mixed, one usually speaks of “science fiction / fantasy”, “sci-fi fantasy” or “ science fantasy ”. Often one uses classic fantasy elements and reinterprets them. For example, the magic of fantasy in science fiction is often exchanged for psi powers, gods or spirits for evolutionarily advanced forms of life.

There is broad agreement that science fiction is characterized by one or more elements that are not (yet) possible in our normal everyday world. For this element, the term Novum has largely established itself . There is disagreement about the extent to which the novelty differs from typical elements of fairy tales or fantasy. Proponents of the strict science fiction definition argue that the novelty must be scientifically explainable and rationally understandable. This position is controversial, however, because in practice most science fiction nova are scientifically unsettled or speculative or it happens (albeit rarely) that today's scientific bases for science fiction ideas become obsolete. Typical nova such as time travel or exceeding the speed of light often arise from pure wishful thinking and are not based on scientific facts. In their plausibility , they hardly differ from the topoi of fairy tales such as flying carpets or talking animals.

The definition becomes difficult by narratives that only mention a topic in the title but choose a different topic as the focus. An example of this is HG Wells ' novel Die Zeitmaschine , in which the time machine is more of a secondary idea that still signals the genre of science fiction, while it is primarily about the dystopia of the Morlocks and Eloi, which are taken from horror literature . The problem also arises that, although comprehensible social criticism appears in a science fiction story, this happens against the background of overly ill-conceived technical ideas that seem to be taken from fantastic literature.

The author Arthur C. Clarke formulated his Third Clarke's Law on this problem : "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic." Perhaps it can be stated that science fiction "tries" to provide scientific explanations while in fantasy the corresponding elements (large, speaking spiders in Harry Potter ) simply have to be accepted without explanation.

Changes

Since science fiction left its former niche and conquered the mass market , it seems less necessary to incorporate science as a constituent element. Fantasy always passes through science fiction more easily. The fact that the viewer immediately identifies the “transporter” of Star Trek technology as a science fiction element has nothing to do with the fact that it is more plausible or technically comprehensible than the magic wand only through its appearance. It just saves scientific justification. Conversely, this does not mean that “all” elements of this type of science fiction are just more magical.

Recently, therefore, science fiction is no longer required, but only that it "claims" science for itself. Science fiction is less a question of plausibility than of the attitude that a film or novel adopts towards the world it portrays. Science fiction is seen by many authors as a fairy tale in which only the selection of the fantastic elements is adapted to the time - people are not conjured up to other places, but " beamed " with technical devices (for example in Star Trek ) to make the story more plausible close. The novelty is "naturalized", ie adapted to the respective ideas of science and technology.

"Aging" of science fiction and fantasy

Science fiction is constantly updated in its methods. Just as Jules Verne and H. G. Wells made unimaginably huge cannons or seemingly absurd steam-powered mechanical devices at the heart of the story, today's authors invent similarly daring devices for time travel or locomotion. The more science fiction moves away from a science-critical point of view in its portrayal of how technology and science have to look, the more it approaches fantasy . This is one of the reasons why science fiction stories, and films in particular, can appear naive or involuntarily funny just a few years after they are made. Developments take place faster, slower or completely different than assumed at the time the work was created. The communicator in the first Star Trek series, for example , with its planetary range was not even conceivable as an expensive special radio device in the 1960s, but in the age of mobile telephony it seems antediluvian (if one neglects in this frequently cited example that mobile telephones are connected to networks and their elaborate installations are required, while communicators function beyond any civilization and even through solid planetary bodies). Other technologies, such as the spaceship or holodeck , are far ahead of the development. Science fiction thus always remains a balancing act between too strong and too weak an assessment of development. There is, however, the genre of steampunk , in which the authors deliberately return to the level of knowledge of an earlier era - preferably the late 19th century - and develop the technologies that were prevalent from there. In recent years, the term “ rocket punk ” has been coined to describe a sub-genre that imitates the classic SF of the Golden Age , based on a level of knowledge from around 1950.

Science fiction and fantasy

Before fantasy or science fiction found recognition as a separate genre, fantasy was often used as a synonym for science fiction (to distinguish it from utopia ).

An older, but still in use systematic regards the Fantastik as a group of those literary (filmic etc.) works in which elements that currently do not appear real occur. Science fiction is the target area here, which operates without the supernatural (such as magic and mythical creatures ). In fantasy, on the other hand, magic or mythical creatures are always part of the setting and the plot. However, there is such a crossover with the role-playing game series Shadowrun , in whose world various novels are set . In other words , in a future, high-tech cyberpunk world, classic mythical creatures such as elves or dragons do exist, and there are different types of magic. The supernatural that has nothing to do with “classical magic” or “typical mythical creatures” ( dragons , elves , trolls etc.), or things that cannot (yet) be explained scientifically and logically, are often summarized under “mystery” ( this term is mainly used in the film sector). Horror can occur in this order in any of the genres. Science fiction is still often classified under fantastic (or fantasy).

There is no uniform classification system for science fiction in literature (in film, in theater, in visual arts) to differentiate between fantasy and fantasy, so that one and the same work, depending on the setting, is sometimes classified under science fiction, sometimes under fantasy, etc. becomes.

subjects

In many science fictions, certain visions of the future are addressed, some of which are already a reality today. In most cases, this also involves modern technologies . These include, for example:

- Time travel

- Some people travel to the future to experience or explore, or to the past to undo mistakes. Mostly time machines are used for this .

- Artificial intelligence

- Artificial intelligence is a very important topic in many science fictions. There help computer or other machines with human-like or human intelligence the people . In some cases these machines get out of control and cause damage, intentional or unintentional.

- Robots and humanoids

- Robots or humanoids serve people and sometimes do uncomfortable work . In some science fictions, these later turn against their human owners or creators and destroy them. In others there is a constructive and peaceful coexistence.

- Space travel

- Travel to other celestial bodies , i.e. the moon , Mars , other planets , exoplanets , the sun or other stars are a particularly popular topic in many science fictions. New types of spaceships and propulsion technologies are used.

- Extraterrestrials

- There are encounters between humans and aliens . Most of the time the aliens are the visitors, but sometimes the humans too. In some cases these encounters are peaceful , but often belligerent .

- Nuclear war

- The nuclear war is one of the most important dystopias . Most of the time, such a war ends in the apocalypse .

- Natural disasters and the end of the world

- Natural disasters , meteorite strikes or other existential dangers decimate humanity or destroy it completely.

- Read minds

- With neurological or other methods can thoughts read are and interpreted.

- Medicine, genetic engineering and biotechnology

- Medical treatments create phenomena such as organ transplants , transgenic or cloned people.

- immortality

- With the help of new technologies, humans or animals become immortal .

Overview and directions

Overlap with other genres

Science fiction is therefore not a puristic genre that is closed to all others. On the contrary, one of the great strengths of science fiction is that it can absorb all imaginable literary currents and styles. David Graeber assumes that since the 1990s science fiction has dispensed with concrete projections of the future, has freed itself from the fascination with technology, but has also lost its utopian content: It has “today become a set of costumes that you can wear Western can dress a war film, a horror flick, a spy thriller or just a fairy tale ”or a dystopia. This gives rise to specific sub-genres. The overlaps with thematically relatively closely related genres are briefly presented below.

Overlap with horror and fantasy

The greatest proximity is probably to genres such as horror literature ( horror film , compare the Alien and Event Horizon cinema series ) and fantasy . Horror describes less the content of a story than the style, the effect on the reader. Fantasy includes those cases in which what happened is no longer apparently explained rationally. Borderline cases to fantasy are spoken of when either the story takes place in such a distant future or in such a different world that what is “natural” there appears to us as “supernatural” (as in Star Wars or Dune , which are more of the fantasy genre can be counted), or the setting (for example medieval hierarchies) or the plot structure (for example the quest ) is fantasy-typical, but the story does not work with magic or mythical creatures.

Although Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein and Robert Louis Stevenson's The Curious Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde contain supernatural elements, they are shaped by the extrapolation of scientific ideas and are therefore considered science fiction in the strict sense. Bram Stoker's novel Dracula, on the other hand, is pure fantasy, as much as actual historical realities are metaphorized, which in turn is neither described by "Frankenstein" nor by "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde ”can be said.

Works running under the umbrella term science fiction do not use space or a future world to speculate about questions of human development, but rather as an exotic backdrop against which traditional genres (adventure, romance) take place. The term is for this space opera - examples are films like Star Wars ( Star Wars ) or movie series like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers . One example in the novel booklet area is the post-apocalyptic series Maddrax , in which science fiction and fantasy are mixed with horror and classic adventure as well as parodic elements.

Depending on the content of the imagined world, novels appearing are more likely to be offered as science fiction or fantasy. Publishers often do not separate the genres sharply and run a "SF&F" series in which science fiction, fantasy and sometimes horror are summarized. For this, the term speculative fiction was coined as an alternative interpretation of the abbreviation SF . In German one speaks of "fantastic literature".

Intersection with utopias and dystopias

Modern science fiction literature usually also overlaps with utopia . While science fiction is often content with the representation of partial aspects of technical and social developments, utopia, which aims to show a complete outline of society, was originally used as a Trojan horse . The aim was often to present political and philosophical ideas to the public while avoiding official censorship.

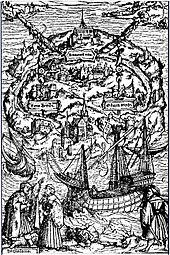

However, the classic utopias such as Thomas More 's Utopia (1516) or Tommaso Campanella's La città del Sole ( The Sun State, 1623) can hardly be considered science fiction, since they were created at a time when scientific and technical progress was not yet important Categories represented; accordingly, the early utopias are not a science fiction novelty. The classic utopias are mostly located on a distant island. Only in the 19th century, with the industrial revolution , the utopia shifted into the future, did nova become typical utopian elements. The classic utopia is based on a static, perfectly organized state structure that only needs to be worked on in detail. Since the late 20th century, less holistic utopias appeared .

An important work at the interface between utopian literature and science fiction was the novel L'An 2440, rêve s'il en fut jamais (The year 2440. A dream of all dreams) by the French author Louis-Sébastien Mercier from 1771, which describes the journey of a resident of Paris into the better future of his city and country, whereby the utopia became something attainable instead of just an exemplary blueprint; Since the author's focus is purely on socio-cultural developments and practically no technical aspects are mentioned (the protagonist of the novel dreams of the future by sleeping in his bed for 700 years), the work is not considered to be "real" Considered science fiction.

In contrast, especially in the 20th century, science fiction encompasses anti-utopias (→ dystopia ). Negative ideas about the future were not yet widespread in the Age of Enlightenment , but since the 19th century the crises of capitalism , the tyranny of totalitarianism and the horror of world wars , as well as the fear of nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction or catastrophes, provided the material for various dystopian scenarios. In the 21st century, climate change was added as a topic (“Cli-Fi” or “Climate Fiction”).

Classical dystopias, like utopias, concentrate on conceivable future forms of society, but characterize them as negative in order to warn of current aspects of the extrapolated relationships into the future. The novel The Maid's Report by Margaret Atwood (1985), for example, takes the sterility caused by disease, radiation and environmental pollution as an opportunity to showcase a Christian fundamentalist and paramilitary society. Often dystopian, or at least less enthusiastic about the future than many works of science fiction, are works of mundane science fiction , which deliberately do without technologies such as interstellar space travel , which are improbable from today's perspective .

A post-apocalypse is the name given to such stories against the background of a civilization destroyed by war, disaster or the like , such as Ape and Essence by Aldous Huxley (1948). A future doomsday event also became a literary theme, often with allusions to Christian apocalyptic , from which the term “ end times ”, widely used for apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic scenarios, was taken.

The gloomy descriptions of the future with the generic term Dark Future also include those stories that are based on a more continuous decline. Possible wars or catastrophes are not the main topic there; in the subgenre mentioned in cyberpunk , totalitarian surveillance by states or the threat of artificial intelligence (in the Matrix film series ) or corporations (in the Neuromancer trilogy ) form the basis of the plot. Steampunk is a similar genre, but in the form of an alternate world story it uses a background with technical and social development similar to the Victorian era .

Overlap with military stories

For some time now, science fiction novels that place a very strong emphasis on the military aspect and in which conflicts are usually resolved in a military manner have been classified in the military science fiction category. These include classic works such as EE Smith's novel Skylark, Robert A. Heinlein's Starship Troopers (see the film adaptation ), Hornblower science fiction adaptations for example by David Weber : Honor Harrington or David Feintuch : Nick Seafort, as well as newer space operas such as John Ringo's Invasion or David Drakes Lt. Leary.

A clear differentiation from other sub-genres of science fiction is only rarely possible. For example, Lois McMaster Bujold's award-winning Vorkosigan saga always fluctuates somewhere between military science fiction, space opera and detective / diplomatic novels, whereby the author also shows a heart for erotic non-everyday things. Due to the often detailed descriptions of technical systems, most military science fiction novels basically belong to the field of hard science fiction. In fact, there are even humorous novels such as Robert Asprin's cycle about the Chaos Company, which could be counted as military science fiction, even though they criticize the military as satirical.

Although military conflicts play an essential role in many science fiction novels, only a small proportion of these works are labeled as military science fiction .

Most authors avoid this term because this branch of science fiction is under criticism:

- "No doubt, they are among us, the revenants of long-dead saber-rascals and intergalactic war correspondents" (Phantasia Almanac No. 5)

- "With a neoconservative mindset and the writing skills of an eleven year old" (Hannes Riffel, editor and translator)

- "... limit yourself as before to transferring US-American imperialism from the home front into space" (Phantasia Almanach No. 5)

Like every literary genre, science fiction is always a reflection of the zeitgeist and the issues that move the public at the time of its creation. Military stories have increased since the main audiences in the industrialized nations were more confronted with the subject as a result of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 and the wars in Europe and the Middle East.

Hard and soft science fiction

Hard science fiction

Hard science fiction (short hard SF ) describes the branch of science fiction that is characterized by an interest in scientific accuracy or details. The stories focus on the natural sciences (e.g. astronomy , physics , genetic engineering ) and technical advances.

Characteristic is a very technique and fact-dominated narrative style and the further development of current scientific phenomena. There are also authors who put the human being in the foreground, so the elaboration of supporting figures occasionally takes a back seat. Usually the technical or scientific aspect is an important part of the plot, with the authors mostly starting from the most modern knowledge of their time in order to develop their own ideas logically.

Greg Bear , Michael F. Flynn , Peter F. Hamilton , Alastair Reynolds , Gregory Benford , Stephen Baxter , Robert Charles Wilson , Liu Cixin and Robert L. Forward are considered to be representatives of current hard science fiction, while Isaac Asimov and Arthur are classics C. Clarke .

Soft science fiction

Soft science fiction ( soft SF for short ) deals more with philosophical , psychological , political or social issues. The term soft comes from English and there distinguishes the mentioned humanities from the (hard or “exact”) natural sciences.

The soft SF uses technical achievements rather marginally and as an aid to embed the storyline. The focus is therefore more on the characterization of the people involved and their emotions, as in the case of Ray Bradbury , Ursula K. Le Guin , Jack Vance or Philip K. Dick , among others .

A well-known example of soft science fiction is Frank Herbert's desert planet series Dune , in which a universe with advanced technology but at the same time a feudal structure is conceived. The role of the leadership and questions of responsibility and ethics are the mainstay of the plot. Further examples can be found in the works of Stanisław Lem , in which he pushed fictions about psychochemical world improvement or political ideas to extremes.

Future literature

Future literature is, on the one hand, the branch of science fiction that deals with the future of human beings and speculates about the further development of mankind (see utopia and dystopia ). At times it was the main field of science fiction and was used as a generic name, with the future always closely linked to the present. Some authors tried to limit themselves to the near future. One example of this is the concept of “close-up fantasy”, which was represented by Carlos Rasch , for example .

On the other hand, the term “future literature ” can be used to describe scientific and popular scientific work on future futurology . The television program The Future is Wild (2002) used the possibilities of modern computer animation .

History of science fiction

precursor

The parody True Stories by Lukian of Samosata from the 2nd century is considered by some authors to be the first work of the genre, as characteristic features such as lunar and planetary journeys, extraterrestrial inhabitants and artificial life appear in it.

Modern times

Science fiction in the narrower sense could only arise with the development of science and technology. After the development of the telescope, the moon was recognized as an extended celestial body and in the age of explorers people immediately dreamed of traveling to the moon ( Johannes Kepler : Somnium, German The Dream , 1634; Cyrano de Bergerac : Les États et Empires de la Lune , German The States and Empires of the Moon , 1657). In Margaret Cavendish's story The Blazing World (1666) a young woman finds herself in a kind of alternative world. Voltaire took his readers into deep space in Micromégas (1752), while Jonathan Swift explored foreign peoples and cultures on earth in Gulliver's Travels (1726). Julius von Voss extrapolated in Ini. A first and twentieth century (1810) novel of military and cultural inventions, from weapons of mass destruction to general social security. In the 19th century, elements of science fiction can be found in authors such as Edgar Allan Poe ( The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall , 1835), Nathaniel Hawthorne and Fitz-James O'Brien . A German representative was ETA Hoffmann .

Early works

The real science fiction era began in Europe in the 19th century. The best-known representatives are Jules Verne with his scientific-romantic adventures and HG Wells with works that are critical of technology and society. Mary Shelley is considered to be the founder of the genre with her novel Frankenstein . The lesser-known Percy Greg also helped shape this time when he let a spaceship called Astronaut fly to Mars in his novel Across the Zodiac , published in 1880 . The word space ship was also used for the first time in a review of this book that year .

A German representative of this period is Kurd Laßwitz , after whom a prize for German science fiction literature is named. With his technical and scientific works, Hans Dominik is known as the German Jules Verne, he is one of the most important pioneers of future literature in Germany. Paul Eugen Sieg was widely read in the middle of the last century with his technical science fiction.

The first German science fiction booklet series was Der Luftpirat and his dirigible airship , which appeared in Berlin from 1908 to around 1911/12 in 165 editions.

In the USA, science fiction appeared mainly in short stories. The best-known periodic science fiction magazine of the time was Amazing Stories, published by Hugo Gernsback , which since 1926 has been devoted exclusively to the publication of science fiction stories. However, the name Hugo Gernsback chose was scientifiction, and then this period of science fiction is called "scientifiction".

The association of science fiction with “cheap” magazines and sensationally designed front pages (hideous monsters and half-naked, helpless women) made it difficult for science fiction to be recognized as serious literature in Germany. These “ pulps ”, however, gave science fiction writers the opportunity for decades to print their myriad of short stories and, because of their low price, to reach the audience most receptive to science fiction: children and young people.

Completely unaffected by the Pulps, Olaf Stapledon wrote his two main works Last and First Men and Star Maker in the 1930s . The concepts found in these works, some of which are very dry to read, were to form a quarry of ideas for many science fiction authors for decades .

With Wir , Yevgeny Zamyatin laid the foundation for dystopian science fiction when it was published in 1924 .

The Golden Age in the USA

Science fiction began to take off when John W. Campbell, Jr. became the editor of Astounding in 1937 . While Gernsback placed more emphasis on technical descriptions and a more simple style, Campbell preferred stories that dealt with topics such as sociology, psychology, and politics. Stories favored by him had to be based on a startling assumption, or at least take an astonishing turn. He later brought out stories by well-known and successful authors ( Isaac Asimov , Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Heinlein ). Overall, science fiction around the world is heavily influenced by US authors of the time.

A number of authors, who can only be attributed to science fiction to a limited extent, tried their hand at the genre and gave science fiction a more serious image ( Karel Čapek , Aldous Huxley , Franz Werfel , Clive Staples Lewis , Ray Bradbury , Kurt Vonnegut , George Orwell , Gore Vidal ).

In philosophy, the problem of the possible self-confidence of robots (the term robot was first used by Karel Čapek in 1920 in his science fiction play " RUR ") was treated as a problem of logic by Gotthard Günther , who even published in Astounding what AE van Vogt for his part took up in Die Welt der Null-A .

After the Second World War

The post-war period saw a growing popularity of science fiction, especially in the United States. The writers found a platform for their stories in ever new magazines. The American dream seemed tangible after the war was won; the 1950s were a time of boom and hope. With the advent of the Cold War , many science fiction writers took on the task of naming the fears of it or the atomic bomb , since the subject was otherwise taboo. The authors were inspired to write about paranoia and dictatorships in space.

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction became of particular importance in 1949, and was groundbreaking for the time due to its high literary quality.

This is how cinema discovered the possibilities of science fiction. The double screenings that took place on Sunday mornings were popular, in which children films such as The Day on which the Earth Stood Still , The Thing from Another World (based on John W. Campbell ), Alarm in Space , Metaluna 4 Doesn't Answer or The Demonic (according to one Template by Jack Finney ). These are films that can be seen as a memorial against atomic bombs or - depending on your point of view - the McCarthy committee or communism . This kept the interest in the books alive.

Authors as diverse as John Brunner and Frank Herbert made their debut in the 1960s , and Philip K. Dick , who had previously been the author of numerous short stories, enjoyed increasing popularity.

Modern science fiction

In 1957 the Sputnik was launched as the first human-made satellite, followed shortly afterwards by Sputnik 2 with the dog Laika on board; In 1961, Yuri Gagarin was the first person to travel into space. The United States was defeated, which is why President John F. Kennedy announced that the first person on the moon must be an American.

The interest in science fiction got a boost again, especially since a number of technical achievements were made as a result of the space race , which were soon in the living rooms of the population. But these advances did not bring peace as hoped.

Science fiction was taken seriously for the first time, because every potential reader of the stories said that their content could become reality sooner or later. The problems and their solutions that were set in space were not too different from those on Earth. James Graham Ballard and Anthony Burgess stand for science fiction that was closer to the present than they could have liked. Harry Harrison wrote New York in 1999 , Philip K. Dick wrote The Oracle from the Mountains over the USA that lost World War II, Thomas Michael Disch The Fire Devils .

Science fiction became an important topic not only in literature. In music, references to space have also found their way into song lyrics since the late 1950s. For example, the vocal quartet The Ames Brothers combined conventional lyrics about love with spaceships and distant galaxies on the album “Destination Moon”. The music label RCA Records hoped to increase sales by incorporating this current trend. Musicians like Sun Ra or Ramases also took up science fiction motifs and dressed them up in cosmic myths.

Frank Herbert's Dune (Dune) was the beginning of a multi-volume cycle him a similar fanatical earned readership like Tolkien with The Lord of the Rings . Herbert's science fiction, with its emphasis on forms of government, people and less on technology, was therefore viewed as soft science fiction.

Even Star Trek , the original Star Trek , whose debut took place in 1966 at the height of the space fever, can be regarded as such soft science fiction. Although great emphasis was placed on the technical details and their consistency (Asimov, as a scientist, acted as a consultant several times), the actions of the consequences are not very typical of SF. Nevertheless, it was the first globally successful series of the genre to advocate universalism and humanism , and the multiethnic composition of the main characters promoted international understanding (for example, a kiss between a white man and a black woman was shown on US television for the first time).

In particular, the follow-up series Spaceship Enterprise - The Next Century (Original: Star Trek: The Next Generation ), which was started in 1987, repeatedly took up explosive socially critical issues in the tradition of its predecessor, with pacifist and humanist elements being given greater weight. The same is true of some of the Star Trek cinema films.

In Germany, seven episodes of the space patrol ran in the mid-1960s with the Orion spacecraft and its crew, which had a comparable composition. The series later got some fans who attribute its " cult status ".

The longest-running science fiction television series to date, Doctor Who , started in Great Britain in 1963 and became one of the most popular television series there. It is the story of a time traveler and his companions. Since 2005, after a break of several years, new episodes have been released.

A further development in the film brought science fiction closer to a wide audience: 2001: A Space Odyssey (director: Stanley Kubrick , written by Arthur C. Clarke ) and Planet of the Apes (based on Pierre Boulle , both 1968) showed that the 'evil Extraterrestrials' no longer irritated the audience. New Hollywood began its revolution and reached science fiction cinema, not least with blockbusters like Star Wars . Between this "space fairy tale" and the uncanny encounter of the third kind (both 1977) there are already worlds, in style and type. The same applies to Alien (1978) and his first successor Aliens - The Return Eight Years Later.

Most of the following science fiction films were colorful, expensive action films , tailored to the tastes of young audiences, and hardly comparable to serious science fiction literature.

An increasingly intellectual and socially influenced science fiction has been found outside the USA since the 1960s. Especially in the countries of the Eastern Bloc , science fiction was able to practice a covert social criticism. Well-known authors are, for example, the Pole Stanisław Lem , who covers the whole spectrum from serious future non-fiction to unreal, sometimes Kafkaesque counterworlds and satirical space novels to computer fairy tales and funny self-parodies of the science fiction genre (Pilot Pirx, Professor Tarantoga), as well as the Brothers Arkadi and Boris Strugazki from the Soviet Union and Sergei Wassiljewitsch Lukyanenko in post-Soviet Russia.

New wave

In the mid-1960s a new trend emerged with the New Wave that had explicitly set itself the goal of breaking with the established conventions of the Gernsback and Campbell SFs. The New Wave was strongest in Great Britain from 1963 to the early 1970s. The central organ of this current, whose name was explicitly based on the French Nouvelle Vague des Kinos, was the British SF magazine New Worlds ; the two main protagonists were Michael Moorcock , who functioned primarily as editor and propagator, and JG Ballard , the literary leading figure of the movement; William S. Burroughs served as a great role model for both of them. Many, however, came from the USA. The American collection Dangerous Visions (edited by Harlan Ellison 1967) was important. Alfred Bester , Ray Bradbury , Algis Budrys , Fritz Leiber , Catherine Lucile Moore and Theodore Sturgeon can be regarded as precursors .

The New Wave showed a more experimental attitude towards the form and content of science fiction, combined with an ambitious , highly literary attitude that confidently differentiated itself from penny literature . The exponents of the current criticized the existing science fiction as conservative literature, which both in terms of content and form remained at a standstill. A renewal of the SF literature was called for, which should formally draw level with the "serious" literature.

The New Wave was never a homogeneous movement, however, and the claim to renew science fiction was only really realized in a few examples. Many of the programmatic texts of the New Wave are contradicting themselves. Moorcock said goodbye to the strong focus on content and pleaded for an upgrade of the style. While Gernsback and Campbell had always defined the content of science fiction and almost completely ignored formal questions, Moorcock referred explicitly to the aestheticist positions of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Cli-Fi / Climate Fiction

(From English climate fiction ). Since the 21st century, along with the emergence of the term Anthropocene , authors have been dealing with the effects of anthropogenic climate change , often with dystopian perspectives. Examples are the trilogy Capital Code - Forty Signs of Rain (2004), Fifty Degrees Below (2005) and Sixty Days and Counting (2007). Hollywood produced the disaster film The Day After Tomorrow in 2004 . The book Alice, Climate Change and the Cat Zeta , published in 2016, uses characters from the fantasy story Alice in Wonderland to discuss issues relating to climate change and to enable a broader readership to critically examine the discussion on climate change and its consequences.

Cyberpunk

A relatively new direction in science fiction is cyberpunk , in which the idea of computer-enabled virtual reality is pursued. William Gibson ( Neuromancer , Count Zero (Eng. Biochips ), Mona Lisa Overdrive ) and Bruce Sterling are to be mentioned as the founders of this direction . Other representatives are, for example, Pat Cadigan and, more recently, Neal Stephenson ( Snow Crash , Diamond Age , Cryptonomicon ). Cinematic works of mostly dystopian reading are for example Matrix or Dark City .

One of the first original film contributions on the subject of virtual reality was - alongside Rainer W. Fassbinder's two-part television film Welt am Draht (1973) - the film Tron (1982). More representative of the visual style of cyberpunk is Blade Runner (1982), the film adaptation of the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? .

Alternative reality

A subspecies of science fiction is the "alternative reality" (from the English alternate reality , see also parallel world , parallel universe, and especially alternative world history ). These stories describe a world in which history took a different course from the reality we know. The science fiction novel Pavane by Keith Roberts , in which a world after the victory of the Spanish Armada is portrayed, as well as the novels Das Oracle vom Berge by Philip K. Dick and Vaterland by Robert Harris and Wenn das Der Führer became internationally known know! by Otto Basil , who draw the world after a victory by National Socialist Germany in World War II . A novel within the novel on the same subject includes The Steel Dream by Norman Spinrad . In the German-speaking world, the authors Carl Amery brought with his novel An den Feuert der Leyermark (1979), Oliver Henkel , Marcus Hammerschmitt and Christian v. Ditfurth ( The Wall stands on the Rhine - Germany after the victory of socialism ) the variant "Alternative Reality".

Science fiction in German-speaking countries

The first description of a trip to the moon in German was Die Geschwinde Reise on the Lufft ship to the upper world, which recently employed five people .. by Eberhard Christian Kindermann from 1744.

The dream already mentioned above . by Johannes Kepler appeared in 1634, but could be read in German for the first time in 1871.

The father of German-language science fiction is Kurd Laßwitz, born in 1848, after whom the important German science fiction prize, the Kurd-Laßwitz Prize , which was established in 1980, is named. John Clute described Laßwitz's 1897 novel Auf Zweiplanet as the most important German SF novel.

Laßwitz influenced subsequent German authors, including Carl Grunert , who wrote a series of "future novellas" between 1903 and 1914. At the beginning of the 20th century, Oskar Hoffmann published several utopian adventure novels with titles such as Die Eroberung der Luft. Cultural novel from 1940 . For the 1920s and 1930s, Paul Eugen Sieg and Hans Dominik deserve special mention, whose technical and scientific science fiction enjoyed great popularity in Germany. With Berge Meere und Giganten , Alfred Döblin created an experimental novel in 1924 that depicts the development of mankind up to the 28th century.

After the Second World War, it took a long time for larger science fiction authors to reappear in German-speaking countries. One of the first was the Austrian Herbert W. Franke , who published novels such as Das Gedankennetz from the 1960s . With the booklet series Perry Rhodan , a science fiction series started in 1961, which is being continued and still has a loyal following. Wolfgang Jeschke , who as long-time SF editor at Heyne Verlag was very important for (West) German science fiction, published his debut The Last Day of Creation in 1981 . Perhaps the best and most popular SF authors in the GDR are the couple Angela Steinmüller and Karlheinz Steinmüller , their novel Andymon. A space utopia from 1982 is a classic of GDR science fiction.

Since his award-winning first novel The Hair Carpet Knotters (1995), Andreas Eschbach has developed into a well-known, popular and critically acclaimed German SF author. Frank Schätzing celebrated bestselling successes with his extensive, intensely researched science thrillers The Swarm and Limit .

Interesting individual works come time and again from authors whose works only partially or in exceptional cases belong to science fiction: for example by Arno Schmidt ( Die Gelehrten Republik , 1957) Peter Schmidt , Thomas Lehr (42), Christian v. Ditfurth (political alternative world novels ), Dietmar Dath ( Kurd-Laßwitz-Preis 2009 for The Abolition of Species ) or Christian Kracht ( Fantastic Prize of the City of Wetzlar 2009 for I'll be here in the sunshine and in the shade ).

Pronounced genre authors of the younger generation would be Andreas Brandhorst , Uwe Post or Frank Borsch .

Science fiction in the Soviet Union

Soviet literature had its own very rich selection of science fiction works, which, due to official literary policy, initially went through a much more contradictory development than was the case in Western countries. The Russian term "Scientific Fantastik" (Nautschnaja fantastika, Russian Научная фантастика) established itself almost at the same time as the English term science fiction. It was already established at the end of the 1920s. In the wake of the space euphoria of the late 1950s and early 1960s, many science fiction works provided utopian designs for a future society, for example in the novel Andromedanebel by Iwan Antonowitsch Eefremow from 1957, which, with over 20 million copies, is the most important and most successful book of this genre, which was newly established in the Soviet Union after the end of the Stalin era. The red planet by Alexander Alexandrowitsch Bogdanow (1908), which describes a communist society on the planet Mars, was published before the October Revolution . Since the 1960s, the genre of science fiction has rapidly developed into a kind of mouthpiece for liberal, religious and political critics of the Soviet government and its worldview ( Arkadi and Boris Strugazki ).

Science fiction films were later made, which in turn served to challenge “Soviet materialism”. For example, Andrei Tarkowski's film Solaris from 1972 portrays the confrontation of a crew of a space station with an absolutely alien form of life, which for them becomes a metaphysical journey into the inner world of their own culture, self-knowledge, love and patience. What is astonishing about the realization of these films is that they were all made in the Brezhnev era, when all forms of organized religion were severely restricted.

Science fiction in Japan

In Japan science fiction was and is a very popular genre that has strongly influenced modern pop culture.

The origins can already be seen in Japanese mythology, but science fiction-like materials first appeared at the time of the Meiji Restoration in Japan. In 1857 what could be described as the first true Japanese science fiction story appeared. It was written by Gesshū Iwagaki and is entitled Seisei kaishin hen ( 西征 快心 編 ), which roughly means "tale of the subjugation of the West". In addition to this fantastic adventure story - with the predominant SF-characteristic scientific mindset - initially translations of Jules Verne's novels were published .

After the Second World War it was mainly American paperbacks that came to Japan with the occupying forces. The first science fiction magazine, Seiun ( 星雲 , "Galaxie"), appeared in 1954, but was discontinued after one issue. In the 1960s, when SF Magazine and Uchūjin ("extraterrestrial") were published, science fiction finally gained popularity in Japan. During this time, the "Big Three" of Japanese science fiction published their first works: Yasutaka Tsutsui , Shin'ichi Hoshi and Sakyō Komatsu .

In the 1980s, interest in science fiction waned as interest shifted to audiovisual media. This period of time is known as the "winter time" ( 冬 の 時代 , fuyu no jidai ). Many writers published science fiction and fantasy stories as light novels to attract young buyers. Nevertheless, for example, Ginga Eiyū Densetsu was published by Yoshiki Tanaka .

In the 1990s, the line between science fiction and light novels blurred. Although Morioka Hiroyukis series Crest of the Stars is a light novel, it was by Hayakawa Shobo published as part of the science fiction mainstream. On the other hand, light novel authors such as Yūichi Sasamoto and Hōsuke Nojiri published hard SF stories.

Science fiction series

The largest SF series in literary form and in general the largest “SF universe” is the weekly series Perry Rhodan . The main series has produced various spin-offs in the form of independent series, computer games or comics. The universe of Star Trek , which is formed by the various television series and films, by novels, comics and computer games, is also very extensive . In Germany, the novel series Rex Corda and Ren Dhark were published in the 1960s, but they were not long commercially profitable. In the case of the Star Wars universe, extensive merchandising has begun based on the films . Other extensive science fiction series are the Gundam universe with more than 30 series and films in 7 timelines, the Macross universe with more than a dozen films and series, the Stargate television series, the Babylon 5 television series, the Honor Harrington book series and the Japanese Seikai-no-Monshō universe.

Prices

- German prizes: German Science Fiction Prize , Kurd-Laßwitz Prize , Fantastic Prize of the City of Wetzlar

- Soviet awards (later Russian): Aelita ; Alexander Belyayev; Bronze snail; Interpresscon; Ivan Yefromov; Begin; Strannik; Velikoye Koltso Award

- American Awards: Hugo , Nebula , Locus , James Tiptree, Jr. Award , Campbell Award , John W. Campbell Award , Rhysling Award (Poetry), Philip K. Dick Award , Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award , Prometheus Award

- International awards: Sidewise Award , Aurealis (Australia), BSFA Award (Great Britain), Arthur C. Clarke Award (Great Britain), Seiun (Japan), Sunburst (Canada), Janusz A. Zajdel Prize (Poland)

SF fandom

The SF genre is characterized by a strong fan base ( Fandom ) in which many SF authors are actively involved. In Germany this has a tradition that goes back to the 1950s. Many fans organize themselves in the numerous small and large fan clubs as well as the numerous Internet communities , which are often supported by the relevant publishers. More recently, online communities have emerged that make it possible to publish your own science fiction short stories on the Internet, for example Orion's Arm or Galaxiki.

Important German SF magazines are Nautilus - Adventure & Fantastic , fantastic! , Nova , Exodus , Quarber Merkur published by Franz Rottensteiner and the Fantastik magazine Pandora . One source of information is the extensive SF yearbook Das Science Fiction Jahr from Heyne Verlag . Contact points for questions and discussions about science fiction are, in addition to the fan clubs, the science fiction newsgroups of the de.rec.sf. * Hierarchy, as well as numerous Internet forums and chats .

In addition to working on various publications (fan magazines, fanzines ) and chat role-playing games , dedicated fan groups often deal with the organization of the numerous SF conventions , or cons for short . The most important SF event of this kind is the World Science Fiction Convention, or Worldcon for short , which awards the Hugo Award, one of the most coveted prizes in SF literature. In Germany, the DORT.con in Dortmund and the Elstercon in Leipzig, which invite international authors as guests of honor, are among the more important conventions with a focus on SF literature. The FedCon however, is valid under the oriented mainly to film and television media conventions as the biggest Star Trek - and science fiction event in Europe.

Use of the term in a figurative sense

Science fiction has entered everyday language as a - sometimes disparaging - term for technical objects or technologies, which are thus classified as "in the distant future" or as "fantasy". The speaker wants to express that he sees the thing described as unrealistic or as "music of the future". This sometimes goes hand in hand with the fact that at the same time the technical feasibility in general and thus the usefulness are doubted.

In the 1980s, for example, the US research program on missile defense in space, the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), was often referred to by critics as science fiction, which was reflected in the popular synonym Star Wars . Afterwards it turned out that the project goals had actually been utopian, and that the technical feasibility had been massively embellished, especially by Edward Teller .

See also

- DSFDB (German Speculative Fiction Database)

- List of science fiction authors

- List of science fiction films

- List of science fiction series

- List of time travel novels

- List of time travel films

- Science fiction film

- Filk

- Fantastic library Wetzlar

- Steampunk

- Fantastic

- Alternate world history

literature

reference books

- Hans Joachim Alpers , Werner Fuchs , Ronald M. Hahn , Wolfgang Jeschke : Lexicon of Science Fiction Literature , 2 Bde., Munich (Wilhelm Heyne Verlag) 1980. ISBN 3-453-01063-9 , ISBN 3-453-01064-7 .

- Hans Joachim Alpers, Werner Fuchs, Ronald M. Hahn: Reclam's science fiction guide. Reclam, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-15-010312-6 , pp.

- Hans Joachim Alpers, Werner Fuchs, Ronald M. Hahn, Wolfgang Jeschke: Lexicon of Science Fiction Literature. Heyne, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-453-02453-2 .

- John Clute , Peter Nicholls : The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction . 3rd edition (online edition).

- Don D'Ammassa : Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Facts On File, New York 2005, ISBN 0-8160-5924-1 .

- George Mann : The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Robinson, London 2001, ISBN 1-84119-177-9 .

- Robert Reginald : Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature. A Checklist, 1700–1974 with Contemporary Science Fictio., Pp.

- Peter Schlobinski , Oliver Siebold: Dictionary of Science Fiction. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-631-57980-0 .

- Donald H. Tuck : The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy through 1968. Advent, Chicago 1974, ISBN 0-911682-20-1 .

- Noelle Watson, Paul E. Schellinger: Twentieth-Century Science-Fiction Writers. St. James Press, Chicago 1991, ISBN 1-55862-111-3 .

Review works

- Brian Aldiss , David Wingrove : Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction. Atheneum Books, New York 1986, ISBN 0-689-11839-2 . German edition: The billion-year dream. The history of science fiction. The expanded and updated standard work on the most fascinating literature of our time , Bergisch Gladbach (Bastei Lübbe) 1987. ISBN 3-404-28160-8 .

- Dietmar Dath : Never story. Science fiction as an art and thinking machine. Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2019. ISBN 978-3-95757-785-6 .

- Lester del Rey : The world of science fiction, 1926-1976. The history of a subculture , New York (Garland Pub.) 1980. ISBN 0-8240-1446-4 .

- James Gunn: Alternate worlds. The illustrated history of science fiction , Englewood Cliffs, NJ (Prentice-Hall) 1975.

- Robert Holdstock (ed.): Encyclopedia of science fiction , London (Octopus Books) 1978, ISBN 0-7064-0756-3 .

- Edward James : The Cambridge companion to science fiction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 0-521-01657-6 .

- Adam Roberts : The history of science fiction , Houndmills u. a. (Palgrave Macmillan, Palgrave histories of literature) 2006. ISBN 978-0-333-97022-5 .

- Matthias Schwartz: The invention of the cosmos. On Soviet science fiction and popular science journalism from the Sputnik flight to the end of the thaw. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 978-3-631-51225-8 .

Special topics

- John Rieder: On the definition of SF or not. Genre Theory, Science Fiction, and History. In: The Science Fiction Year 2016. Golkonda-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-944720-97-5 , pp. 27-59.

- Linus Hauser : Travel to the Hereafter. The religious history context of science fiction. Wetzlar 2006.

- Thomas Koebner (Ed.): Film genres: Science Fiction. Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-15-018401-1 .

- Heiko Schmid: Metaphysical machines. Techno-imaginative developments and their history in art and culture. transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2016, ISBN 978-3-8376-3622-2 .

- Georg Ruppelt : "The great humming god" Stories of thinking machines, computers and artificial intelligence. With a document of the exhibition by Uwe Drewen u. a. (Series: Reading room, 7) Historical overview on the occasion of an exhibition, brief descriptions of classical literature, models, etc. a. Ed. Lower Saxony. Hanover State Library. Niemeyer, Hameln 2003, ISBN 3-8271-8807-5 .

- Georg Ruppelt: Yesterday's Future. An overview of the history of the years 1901–3000 compiled from old and new science fiction texts. Book accompanying the exhibition of the same name in the State and University Library Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky from November 22, 1984 - January 12, 1985. VPM, Hamburg 1984, ISBN 3-923566-12-3 .

- Matthias Schwartz: Expeditions into other worlds. Soviet adventure literature and science fiction from the October Revolution to the end of the Stalin era , Böhlau, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-412-21057-1 .

- Erik Simon , Olaf R. Spittel (ed.): The science fiction of the GDR. Authors and works. A lexicon. Verlag Das Neue Berlin, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-360-00185-0 .

- Hans-Edwin Friedrich: Science fiction in German-language literature. A paper on research until 1993 , Tübingen (Niemeyer) 1995. ISBN 978-3-484-60307-3 .

- Hans Földeak: Newer tendencies of Soviet science fiction , Munich (Sagner) 1975. ISBN 3-87690-100-6

- Harold L. Berger: Science fiction and the new dark age , Bowling Green, Ohio (Bowling Green University Popular Press) 1976. ISBN 0879721219 . ISBN 0879721227

Periodicals

- Wolfgang Jeschke , Sascha Mamczak (Ed.): The Science Fiction Year. Annual volume, Heyne Verlag.

Radio

- Thomas Gaevert : The earth is turning left! - Science fiction in the GDR. Radio feature, production: Südwestrundfunk 2002, first broadcast: October 24, 2002, SWR2.

Web links

- Bibliography of German-language science fiction stories and books

- German speculative fiction database - DSFDB

- The Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- ScienceFiction entry in the BücherWiki

- The definition of science fiction in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

- Bibliographies on science fiction in the GDR

- Online database of German science fiction books on loan from the 1950s and 1960s

- Science fiction bookshelf at Project Gutenberg - English language science fiction

- Feminist fantastic-utopian literature ( Memento from June 7, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Brian Aldiss: The Million Years Dream. Bastei-Verlag Gustav H. Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1980, ISBN 3-404-24002-2 , p. 27.

- ↑ “By 'scientifiction' I mean the Jules Verne , HG Wells and Edgar Allan Poe type of story - a charming romance intermingled with scientific fact and prophetic vision… Not only do these amazing tales make tremendously interesting reading - they are always instructive. They supply knowledge […] in a very palatable form […] New adventures pictured for us in the scientifiction of today are not at all impossible of realization tomorrow… Many great science stories destined to be of historical interest are still to be written… Posterity will point to them as having blazed a new trail, not only in literature and fiction, but progress as well. " Amazing Stories , April 1926 issue.

- ↑ The term was coined by Darko Suvin, cf. Darko Suvin: Poetics of Science Fiction. On the theory of a literary genre. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1979, pass. - Original: Metamorphoses of Science Fiction. Yale 1979.

- ↑ See Simon Spiegel: The concept of alienation in science fiction theory. An attempt at clarification. In: Franz Rottensteiner et al .: Quarber Merkur. Franz Rottensteiner's literary magazine for science fiction and fantasy. No. 103/104, pp. 13–40, First German Fantasy Club, Vienna 2006, pass.

- ↑ Rick Robinson: A Farewell to Rocketpunk? Checked 2011-0225-1754 (edt. 2008-0907-1338), Paragraph 1: “The term 'rocketpunk' was coined, by analogy to steampunk, to denote a style of retro-SF that evokes science fiction of the mid-20th century, especially the first hard SF, a [sic] la Clarke and Heinlein, the Willy Ley / Chesley Bonestall illustrations, and so forth. "

- ^ David Graeber: Bureaucracy. The utopia of the rules. Stuttgart 2016, p. 134.

- ↑ See also: Military Science Fiction Bibliography (2009) and Science and Fiction Themenkreis on ( eLib.at ).

- ^ SC Fredericks-Lucian's True History as SF. Retrieved March 25, 2019 .

- ↑ John Tresch: Extra! Extra! Poe invents science fiction! In: Kevin J. Hayes (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge / New York 2002, pp. 113–132, here p. 115.

- ↑ http://ditc-radio.blogspot.de/2012/02/die-februar-ausgabe-ist-thematisch.html Science-Fiction in Music - special broadcast of "Diggin in the Crates"

- ↑ John Clute , Peter Nicholls (Ed.): The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. St. Martin's Griffin, New York 1993, p. 378.

- ↑ Edward Rosen (Ed.): Kepler's Somnium: The Dream, Or Posthumous Work on Lunar Astronomy. Courier Corporation, 1967, p. IX

- ↑ John Clute: Science Fiction - The Illustrated Encyclopedia. Heyne, Munich 1996, p. 213.

- ↑ Cf. Matthias Schwartz: Expeditions in other worlds. Soviet adventure literature and science fiction from the October Revolution to the end of the Stalin era , Cologne 2014, pp. 234–272.

- ↑ Cf. Matthias Schwartz: The Invention of the Cosmos. On Soviet science fiction and popular science journalism from the Sputnik flight to the end of the thaw , Frankfurt am Main 2003.

- ↑ 著者 イ ン タ ビ ュ ー : 長 山 靖 生 先生 . In: Anime Solaris. Retrieved on August 5, 2014 (Japanese, Interview with Yasuo Nagayama occasion of his with the seiun award winning book Nihon SF seishinshi: Bakumatsu Meiji kara sengo made ( 日本SF精神史幕末·明治から戦後まで , "Intellectual History of Japanese Science Fiction: From the Bakumatsu and Meiji Periods to the Post-War Period ”). ISBN 978-4-309-62407-5 ).

- ↑ List of winners

- ^ Karl Clausberg: Long-range weapons - dream dreams. SDI and Science Fiction: then and now. Science & Peace 1986-3: 1986-3 / 4