History of the Küssaburg

The ruins of the Küssaburg are located in southern Baden-Württemberg on the Swiss border in the eastern district of Waldshut in the municipality of Küssaberg .

The history of the Küssaburg (also Schloss Küssenberg ) is based on assumptions that are derived from geographical conditions and the history of the places in the area and are based on military measures - for example, with the assumption that the Celts and Romans did not unsettle a tactically significant place would have left.

There are various details in the literature about the first documented mention: Whether it was about the Küssenberg, or possibly a built-up area (888); later about a noble family, from whose name it was possible to draw conclusions about a castle (1135/1141) or about the clear mentioning of a castle, cannot be definitively decided without looking at the documents again.

In the entire course of the history of the castle is not recorded coherently in the literature until today:

"Although the history of the castle has been dealt with in numerous individual representations and there are extensive references from this point of view, a source-based and complete treatise is still pending."

Naming

There are two scientifically justified derivations and some regional, poetic and speculative interpretations that relate to comparisons in word sound or in spelling.

Place names are generally derived from two factors - on the one hand from the names of the founders and owners, on the other hand from topographical features - terrain names - whereby "the names of waters ( hydronymes ) stick very permanently to the geographical appearance once named, more permanent than the settlement names and that they were also able to withstand any population shifts, for example mass migrations. "

It is important to note that the place names (castle) Küssenberg and Küßnach in the naming convention should be examined, especially as they also belong together historically. Both are “compound names”, with Küßnach - “with -bach or -ach / -a as the second component (basic word). […] While -bach first became the basic word for river naming in German, compositions with -ach / -a as a second component belong in older, Germanic contexts […] in the migration period or even earlier . [...] It wouldn't be pointless to operate there with Celtic names. "

With -ach or -a ...

"... are compositions with the old German word aha 'water'. [...] There are also aha names with a personal name as a defining word. The hydronomy of the district of Waldshut shows such a case, namely in the settlement names Küßnach and Küssaberg. It has long been suspected that an old name of today's Hinterbach (on the Rhine) lives on in both names. "

Historical evidence.

According to Albrecht Greule , a personal name - Kusso ( Genetic Kussin ) - is to be seen as a defining word , in combination with the basic word -ach in Küßnach. This then also applies - through the same owner of both places - in the transfer to (castle) Küssaberg.

“Beginning with the Wutach, an oh- landscape spreads in the district of Waldshut almost to the edge of the Alps [...] You probably don't go too far if you consider this finding with an early settlement of the eastern Upper Rhine and northern Lake Constance areas by Germanic Tribes ( Alemanni ) explained. "

A second version is also based on a compound name: in the defining word from the personal name 'Cossinius':

In the local history research Emil Müller-Ettikon : “On the Küssenberg sat a Celt who called himself Cossinius, a gender name that is attested several times. He also named the village of Küßnach. The -ach does not come from the Germanic aha = ah, which means flowing water […], but is the Celtic suffix -akos, Latin akum, which expresses possession, belonging to a person. "

Both interpretations are considered by the archaeologist Jürgen Trumm:

“For the place names north of the High Rhine, a possible pre-German origin on the part of linguistics is only discussed for Gurtweil ( curtis villa with reference to the Roman settlement Schlößlebuck ), Rafz and Küßnach opposite Zurzach. In the latter case, B. Boesch suspects - as with Küßnacht on Lake Zurich or Küßnacht on Lake Lucerne - a Gallo-Roman place name with the possible derivation of fundus Cossiniacus [court of Cossinius]. "

“This thesis is tempting, even though Roman finds from the Küßnach district have not yet become known. Küßnach would therefore be the only pre-German name north of the Rhine or Lake Constance between the mouth of the Aare and Bregenz. A Germanic place name is also conceivable, composed of a personal name (e.g. 'Chusso') and a water body name with the suffix -ach (for water). "

In the Swiss neighborhood, in the village ( Küssnacht am Rigi ), the emphasis is on the 'Gallo-Roman interpretation'.

Wolf Pabst, Küssaberg, has summarized the multitude of poetic, sometimes speculative name explanations, which mostly relate to comparisons in word sound or in spelling.

Location and importance

The ruins of the Küssaburg are located on the Küssenberg plateau , an elevation of the southern foothills of the Randen Mountains , which demarcate the Klettgau landscape from the Upper Rhine .

The direct possible control of an ancient traffic and trade route from the Alpine foothills across the Rhine to the north is decisive for the historical significance of the Küssenberg and the fortifications on the summit.

The panoramic view there allows the view of this from the Romans from 15 BC onwards. Chr. To Heerstraße south of the Rhine crossing between the today's places Bad Zurzach / Switzerland and Rheinheim (Küssaberg) and to the north over the Klettgau level to the place Oberlauchringen to the west and east to the Randenberg mountains near Schaffhausen and up to the hill above the city Stühlingen with Hohenlupfen Castle . It is believed that watchtowers and signal towers were built here in Roman times.

After the Roman era, the importance was reduced to regional aspects, for example as a hill fort and refuge for the residents of the surrounding villages, primarily for Küßnach and Bechtersbohl . After the incorporation of Alemannia into the Franconian Empire and the consolidation of the Germanic state formation from the 6th century onwards, the importance could have increased again. It is not known whether the place played a role in the Alemannic uprisings against the Carolingian rulers . After Franconian counts took control of the districts founded by Charlemagne , a castle on the Küssenberg became the seat of the Klettgaugrafen.

In the following centuries of empire formation, the founding of the Swiss Confederation and the emergence of European wars, the fortress played a strategic role, but it also became the fortress of a peasantry that was becoming more self-conscious, but could never be conquered by them.

In the Thirty Years' War it became clear that the importance of fixed places was dissolved as a result of large-scale political conflict situations and also military-technical developments.

After the destruction in 1634, the Küssaburg was not renewed and fell into disrepair.

prehistory

It was not just the secure location that made it probable that the place was inhabited in prehistoric times. Nearby plateaus and springs offered groups of people a favorable environment:

Early days

“In 1938, when a water pipeline was being built in the immediate vicinity of the castle, a heavy ax from the early Bronze Age (7000 to 5000 BC) came to light. The site of the find, a thick layer of rubble, is in the immediate vicinity of the outer curtain wall from 1530. Details of the circumstances of the find are not known. […] Location: Waldshut Local History Museum, Inv. No. Wa 474. "

Celts

It can also be assumed that the Küssenberg was fortified by Celts . Although there are still ramparts or ramparts in the further east of the castle, a determination is not possible without archaeological investigations. Since the plateau of the Küssaburg could be well sealed off by the mountain slopes sloping steeply on three sides and the narrow 'tube' at the weak point on the eastern side, a Celtic fortification can be assumed, as hill castles in the region similar to old traffic routes such as the Wallburg Semberg , the Hornbuck near Riedern am Sand or the Birnberg near Grießen can be traced back to Celtic or early development.

Romans

It is also assumed that there was a watchtower and signal tower at the same location around 2000 years ago to secure the section of the Roman military road from Tenedo (Bad Zurzach / Switzerland) to Juliomagus (Schleitheim / Switzerland). At the foot of the mountain there was a Gallo-Roman temple . An aerial photo that led to the discovery of the temple shows, in addition to the route of the Heeresstrasse, a number of other buildings around the temple, so that extensive Roman development of this area in front of the castle can be assumed.

The finds and findings from the Bronze Age to the early Middle Ages make a very old fortification on the mountain probable, but the fortifications built are no longer visible above ground. The local history researcher Egon Gersbach: “So much should be emphasized that most of these places [like on the Küssenberg] due to their favorable defensive position and taking advantage of already existing fortification ruins were populated again and again and often enough into the early Middle Ages or in the higher The Middle Ages encouraged castle building. The older fortifications, which have more or less decayed, may have been redesigned beyond recognition by the younger buildings, or they may have been completely destroyed or cleared away. It is precisely the extensive and particularly profound earth movements that were connected with the expansion of the high medieval castles in stone that the prehistoric security systems that were certainly there in the past fell victim to the mostly spatially restricted areas. "

Two track stones in the wall material of the Küssaburg show that, after the transition to stone construction around 1000 AD, the material from the ancient stone buildings in the area was used for new constructions in villages and especially for castles, which are probably from the steeply sloping Roman road from Bechtersbohl in the Klettgau . They prevented cars from swerving there. Processed stones, including those with inscriptions, were mostly set into the masonry with the 'picture side' facing inwards, so that they can hardly be seen today.

Alemanni and Franks

In 386, the Romans finally built a stone bridge between the fort town of Tenedo (Bad Zurzach) and the Rheinheim bridgehead. In historical literature, a long phase of often peaceful coexistence (trade) is assumed during these times. After the dissolution of the Roman Empire and the withdrawal of the last troops from the Upper Rhine line in the middle of the 5th century AD - the bridgehead on the northern bank probably still existed around Rheinheim and with the involvement of the Küssenbergs - the Alamanni were also able to survive in the Unhindered settlement of the Upper Rhine region on both sides of the river.

.. After the defeat of the Alemanni around 500 AD against the Franks under the Merovingian kings ( Battle of Tolbiac , 496), the winners first occupied strongpoints Alamannia and later founded their own villages - a fact that in the research with corresponding name extensions of villages connected becomes. The traditions tell of a long and extensive autonomy of the Alamanni under Frankish rule.

It can be assumed that the Küssenberg was immediately occupied by the Alamanni after the Romans withdrew and as a strategic point after their victory by Franconia. It is known that former Roman places, which the Alamanni tended to avoid, were already rebuilt into royal estates by the Merovingians. The country was left to Alemannic dukes who tried to make themselves independent again in a series of uprisings from the middle of the 7th century. However, in the blood court of Cannstatt (746) these efforts came to an end.

Under the Carolingian kings, Alamannia was only a province of the empire that Charlemagne divided into the districts that still exist today around 800. The former duke title used by the Alamanni was replaced by the Franks with the establishment of the count's offices, which were initially also occupied by them. Counts Ruthard and Warin are the first to come down to us.

middle Ages

A castle was " first mentioned in the archives of the Rheinau monastery in 888 ".

Local history researcher Hans Ruppaner provided more detailed information in an (undated) brochure for the exhibition “Die Küssaburg” at the Museum Küssaberg (July 17 to September 12, 1993): “The history of the Küssaburg has been documented since the 9th century. For then a count Gotzpert, forgave Gaugraf of Alb - and Klettgau, the castle to the monastery Rheinau. "

Wolf Pabst also confirms this ownership, which refutes the widespread representation that a castle was first mentioned in a document in the 12th century. A picture of his own: “The Küssaburg [...] in the 9th century. [...] The Gaugraf Gotzbert from the noble family of the Guelphs ruled the castle . [...] The fourth abbot of the Rheinau monastery was also called Gotzbert. It is therefore assumed that the lord of the Küssaburg entered the monastery in later years. ”The transfer of ownership of the castle to Rheinau in 888, in which the lord became abbot of the monastery, is a logical consequence.

Emil Müller-Ettikon, historian Küssabergs, however, wrote: "Whether Count Gotsbert [...] had his residence in Balm or on the Küssaburg cannot be proven."

“In the Klettgau, the effectiveness of counts […] can be traced back to the time of Charles d. Size can be followed up to the end of the 11th century. ”But it can be stated“ that the occupation of the count's office in Klettgau was not able to develop heredity into the 10th century. [... The counts] belonged to a class of aristocracy whose activities and their personal relationships went far beyond a single country. "They were representatives of the Franconian kingdom, relied on royal estates and were in the region -" since 858 "- in close connection with the Rheinau monastery . With the "formation of numerous independent aristocratic lords" in a wide area in conjunction with the system of donations to the monasteries, there were shifts in power "around 1100"; In other words, the rule changed to “noble houses of the countryside”, who were able to enforce the inheritance of the count's office.

High Middle Ages (1050 to 1250)

After the end of the first empire formation by Charlemagne (from 800), the secular power structures dissolved again in the 10th century into numerous small aristocratic rule: “Of these, in the 1st half of the 12th century about 15 at the same time in the Noble houses living in Klettgau only 3 or 4 remained at the end of the same century. "

With Heinricus de Chussaberch , the Küssenberger family is mentioned for the first time in 1135 and 1150 in documents from the Allerheiligen monastery .

It should be noted that the builders (owners) of a castle did not name the castle by its name, but rather by the (already existing) name given to the castle or the mountain.

From this finding it could be concluded that the castle was built by the Küssenbergers or that it was new and larger from modest previous buildings.

Counts of Küssenberg

The Counts of Küssenberg were an important aristocratic family at that time, because in addition to their rule over the Klettgau "the Landgraviate of Stühlingen also came to the Barons of Küssenberg, whose ancestral castle was the Küssaburg."

A Werner of kisses Berg was from 1170 to 1178 Abbot in St. Blasien monastery .

In 1177 a Heinricus is mentioned for the first time as Comes (Count) de Stuhlingen Henricus de Cussachberch in a document from Berthold IV. Von Zähringen .

At the turn of the 12th to the 13th century, the Counts of Küssenberg , who derived their title from the extinct Counts of Rüdlingen-Stühlingen, and the Lords of Krenkingen ruled the region: “Both were families who referred to the Dukes of Zähringen leaned on ". In 1218, however, the Zähringers died out and their state collapsed - the Krenkingers occupied the vacant positions in the region. Obviously, the Küssenbergers couldn't keep up here. The last Count of Küssenberg was Heinrich III.

Sale of the Küssaburg to the diocese of Constance

“In 1241 Count Heinrich III., Who married the daughter ( Kunigunde ) of Count Albrecht von Habsburg and sister of the later King Rudolf I and whose marriage remained childless, sold the castles of Küssaburg and Stühlingen and the town of Tiengen to Bishop Heinrich from Constance . After the death of Count Heinrich III. von Küssaburg [probably 1250] a dispute arose between the successor of Bishop Heinrich, Eberhard von Konstanz and Heinrich von Lupfen, who laid claim to the entire Küssaburg inheritance including the Landgraviate of Stühlingen . Heinrich von Lupfen, who considered himself the legal successor to this inheritance, since Heinrich III. von Küssaburg had died childless, devastated the Constance area when the bishop asserted the purchase contract. The bishop, however, banned him and offered his vassals. After long feuds, a settlement was reached on March 13, 1251, which was settled by arbitration.

Heinrich von Lupfen and his descendants did without the Küssaburg with accessories in this comparison, for which Bishop Eberhard awarded them the Stühlingen Castle and 12 Marks Hubengeld. Since there were also a number of properties belonging to the Diocese of Constance in the vicinity of the Küssaburg, a small lordship of its own 'Küssaburg Castle and Valley' was formed. [...] It was made up of the five communities of Bechtersbohl, Küßnach, Dangstetten, Rheinheim and Reckingen, whose residents had to pay taxes, interest and services to the bailiff and belonged to the judicial district of the basement court in Rheinheim . "

The bishop also acquired “the numerous single farm settlements created by clearing on the slope of the southern edge”.

Late Middle Ages (1250–1500)

In the background of these rearrangements to the old counties Klettgau and Stühlingen in 1251 far higher level of power had formed: When Duke of Swabia "had in 1254 [..] the Hohenstaufen King Conrad IV. The staufer loyal Count Rudolf von Habsburg against release of cities Breisach and Kaiserberg the count and Vogt rights over 'St. Blasien und den Swarzwalt '(left). [...] The Habsburgs needed rule over the forest zone in order to achieve their long-term goal of becoming the successor of the Hohenstaufen in the Duchy of Swabia . You did not get a chance in this regard. But they never released the 'forest' and St. Blasien. "

Despite the end of the Interregnum , the emperorless period by King Rudolf von Habsburg, the Roman-German Empire remained fragmented and large parts of real power lay with the secular and spiritual territorial lords, who now had ever larger areas. Despite all the problems that occurred, the late Middle Ages were characterized by increased mobility and internationality as well as changes in many areas of life.

After the end of the Küssenberger Grafschaft in 1250, the Habsburg King Rudolf I soon eliminated the power of the Krenkingers - in 1288 - so that “at the turn of the 13th to the 14th century, the Landgraves in Klettgau: the Counts of Habsburg-Laufenburg , only had to reckon with two competitors: the Bishop of Konstanz and his rule Küssaberg and the trading town of Schaffhausen, which was gradually emerging from the monastic rule of the All Saints' Abbey . "

Constance monastery

Under the rule of the Diocese of Constance (since 1250), which had appointed a Vogt to administer it, the castle and the traffic routes were extensively expanded: "The Bishop of Constance had a bridge built to the neighboring exhibition center of Zurzach ."

In the following decades, the bishops of Konstanz systematically expanded their power in Klettgau as well as on the left bank of the Rhine: They acquired Neunkirch from the Krenkingers in 1260 and elevated the town to a town in 1270, and in 1302 they took over the bailiffs in Ober- and Unterhallau - south of the Rhine in 1265 Zurzach and surrounding villages, 1294 city and castle Kaiserstuhl . “In contrast to the flourishing of episcopal-Constance rule in Klettgau, there was the decline of Krenkian power.” Like other noble houses, the barons of Krenkingen were able to enforce a form of arbitrary rule during the period without central power - “the imperial times”: They “raged and raged in Klettgau with impunity until King Rudolf von Habsburg - whose house in Klettgau was wealthy - appeared in Klettgau with armed force in 1288 and took and destroyed their castles Weißenburg and Neu-Krenkingen. “It cannot be ruled out that the Krenkinger held the county in Klettgau for a long time in the 13th century, but "since the end of the 13th century the Habsburg-Laufenburgers have been the owners of the bailiwick over Rheinau and the Landgraviate of Klettgau."

The outer bailey of the Küssaburg

With the expansion of the castle "the houses of the servants and serfs were united with the castle by a curtain wall on the upstream plateau ." The residents of the outer bailey are documented from 1317 to 1494. "The outer bailey of the servants received the right to hold its own mayor and priest in 1346 through Bishop Ulrich Pfefferhard ." On Mychahel's evening in 1346, Ulrich Pfefferhard gave the outer bailey the same town charter as the city of Neunkirch with a letter of freedom .

The outer bailey - also: the town in front of the Küssaburg - existed for about 200 years:

“When the outer bailey was rebuilt after the Peasants' War [1525], part of the outer bailey was given up because it was partially destroyed by the peasants. [...] Remains of the curtain wall can still be seen on the south side of the former outer bailey. "

End of the Constance rule

According to the yearbook for Swiss history (1911), Bishop Marquard von Randegg pledged his castle and town in Küssenberg in 1402 to the city of Schaffhausen for 450 gold guilders. This representation contradicts a Konstanzer Regeste Marquard von Randegg from June 13th 1402, in which he only opens the Küssaburg and the castles Neunkirchen and Kaiserstuhl for 10 years in Schaffhausen, which is more like the equivalent of 450 guilders. This opening soon became a nuisance due to an attempted influence and was revoked by Konstanz as early as 1408. Around 1408 the castle came to the knight Ulrich Thüring von Brandis .

In 1410 Albrecht Blarer resigned voluntarily as Bishop of Constance and Otto III. von Hachberg followed him as bishop, from him in July 1410 he received a fixed sum in money, annually grain, oats and six loads of Meersburger wine as well as a right of residence on the Küssaburg, where he remained as priest Albrecht until the end of his life.

The castle was pledged to Bilgeri the Younger von Heudorf in 1421. His son Knight Bilgeri von Heudorf took the Küssaburg as his seat in 1429. In 1444 Bilgeri von Heudorf exchanged with the bishop Heinrich VI. von Hewen ran the Küssaberg against the city of Tiengen, but stayed at the castle until 1448/49.

Archduke Maximilian initiated the end of the rule of the diocese over the castle in 1479 when he ordered the transition from either the castle and the rule of Tiengen or the rule of Küssaburg and castle to a pledge to Otto IV von Sonnenberg .

Ownership in the 15th century

While the castle and town remained in the possession of the Diocese of Constance for a long time, but were increasingly pledged - sublet, as it were - the change of power in rule over the Klettgau was already underway at the beginning of the 15th century. The castle had obviously already lost its importance as the central seat of power in the power structure. This was only to change again in the Peasants' War - the people tried to establish themselves as a new power factor here for the first time and thus the disputes shifted back to the region.

Change of ownership in the county of Klettgau

“In 1408 Ursula, the daughter and heiress of Count Hans IV. Brought the Landgraviate of Klettgau [...] to the house of the Counts of Sulz . [...] By acquiring the dignity of Landgrave in Klettgau, the Counts von Sulz also tried to maintain the Vogtei Rheinau . "From 1409, this was subordinate to Duke Friedrich IV of Austria , who tried to create" a closed Swabian-Upper Rhine property ":" The tip of land between Wutach and Rhine was indeed an annoying obstacle to territorial development for Austria in the border area between Upper Rhine and Swabia . However, for half a century the Counts of Sulz fought bitterly for the Bailiwick of Rheinau. ”Another opponent was the city of Schaffhausen , which dominated numerous positions (taxes, jurisdiction and religious sovereignty) in the“ Schaffhausen Klettgau ”.

The count's opponents achieved a significant success with the destruction of the Sulzer bastions in front of Rheinau in 1449 - the Balm and Oberrheinau castles . "The feud between the Rheinau monastery and the Counts of Sulz was only settled when it came under the protection of the Swiss Confederation in 1455 [...]."

Although Bilgeri von Heudorf fought as the “last knight” with the Count von Sulz in league, the city of Schaffhausen between 1449 and 1476 on all levels, but this did not change the great military stalemate. The disputes had now shifted to a settlement in court in 1497: The Sulzer received control of the Küssaburg.

Transfer of the castle to the Counts of Sulz

In a letter in 1479 , Archduke Maximilian instructed the Bishopric of Constance to give the castle and rule of Tiengen or the rule of Küssenberg and Otto IV of Sonnenberg as pledges. The diocese ceded the Küssaburg.

This order of the Archduke shows a power of disposal that was decided far outside of regional disputes and followed other regulatory interests than those involved on site. These relationships cannot currently be clarified using the available (regional) literature.

In 1482 Alwig X. von Sulz acquired the pledge for the town and castle of Tiengen from the bishopric of Konstanz.

His son Rudolf V. von Sulz married Countess Margaretha von Waldburg - Sonnenberg (1483–1546) on May 1, 1497 . This made it possible for Sulzer to access the Küssaburg.

Rudolf V ceded the rule and the Bohlingen castle to the diocese of Constance and received the castle and the rule of Küssaberg as a pledge from the Sonnenbergers for an additional pawn schilling of 6000 guilders.

The reorganization between Sulzern, Konstanz and Schaffhausen appeared two years later with the 'Swiss War' that began in 1499. As a result, the Klettgau became the plaything of great powers - and the castle "a spatially insignificant, but constantly effective bastion against the Swiss Confederation."

The Küssaburg in the Swiss War

The outbreak of the Swabian or Swiss War in 1499 was the response of the Confederation , which saw its freedom threatened , to the imperial reform decreed by Emperor Maximilian .

This "confronted Count Rudolf von Sulz with the decision to take the side of the Emperor and the Swabian Confederation as prince or to fulfill his obligation as a citizen of Schaffhausen and Zurich." The count not only had possessions on the Upper Rhine border - his Core holdings were in Swabia, in the Reich territory.

His hesitation “put an end to Count Sigmund von Lupfen and Lux von Reischach after the invasion of the Confederates in Hegau and occupied Tiengen and the Küssaburg from Waldshut, where Count Rudolf was also staying, which contrary to the advice of Eglisau Landvogtes Jakob Tyk of the Confederates had not been occupied in order to secure the people of Zurich on the Rafzer Feld and the Klettgau people, but many of them fled to Switzerland via the Rhine. […] During Palm Week, the Zurich team moved into the Klettgau and captured Neunkirch and Hallau with enthusiastic support from the population, even though they were subjects of the Bishop of Constance. The two villages were recaptured and set on fire, but fell back to the Confederates. "

By occupying Tiengen and Küssaburg with an Austrian garrison, Count Rudolf von Sulz had meanwhile positioned himself for the imperial side. As a result, the Federal Diet decided to move to the Hegau and the Black Forest with the plan to take Tiengen and the Küssaburg.

“In mid-April 1499, the people of Bern, Lucerne, Zurich and Schaffhausen, who had come from Kaiserstuhl via Grießen and Geißlingen to Lauchringen, moved to the town of Tiengen, where the Freiburgers joined the ring of besiegers. The city was held by a garrison of 1,400 men under the orders of Dietrich von Blumegg , who preferred, however, to leave the city secretly with some other nobles at the hour of greatest need, whether out of cowardice or because he did not accept the occupation, which is known to be rampant trust, as a Swiss chronicler thinks, is put there. After two days of siege and shelling, Tiengen surrendered on April 18, 1499. "

The residents and soldiers were able to leave "in their bare shirts" and the city was given up for looting. The following day the city caught fire and was completely destroyed.

According to the chronicler Valerius Anshelm , the Swiss managed to position a large cannon in front of the main gate of the Küssaburg during the night. The crew of 50 men surrendered to 500 besiegers on April 20 and received free retreat, allegedly against the will of the captain. Anselm emphasizes that the Küssaburg was a castle that was well looked after, and that the crew was even equipped with armor.

"On the Küssaburg, whose crew was commanded by the Zurich captain Heinrich Ziegler and Hans Stucki as Vogt until the conclusion of peace, the conquerors made rich booty from the belongings that had fled here."

The events in the castle are recorded in the contemporary diary of the Villingen councilor Heinrich Hug : Among the 25 men of the crew was Remigius Mans as gunsmith from Villingen , who Hug used as a source. Twenty men, including peasants who had been forced to serve, refused the commandant's service. After the arrival of the crew in Waldshut, the mutineers were beheaded up to five men by order of the governor.

Burgvogt Martin von Starkenberg handed over the castle to the confederates in front of Stühlingen in return for the assurance that the city, castle and population would be spared. In vain, because the city and castle were subsequently looted and cremated. The "communities of the Küssenberger Valley - including Jestetten, Erzingen, Grießen and Geißlingen - [...] who were forced to pay homage by the confederates in return for an assurance of protection - escaped retaliation as their executor, Field Captain Willibald Pirkheimer on the orders of Count Rudolf for help requested forest bailiffs to steal, plunder and pillage his soldiers. When the news spread among the mercenaries that the forest bailiff was claiming the entire pillage for himself, they let their bitterness run wild. In their distress, the residents had fled to the churches, and the congregations tried to avert the cremation of the houses by paying ransom. But vengeance was carried out without mercy. "

The war had spread to many regions in the early summer and the declaration of war by Emperor Maximilian to the Confederates was followed by the victorious decisive battle near Dornach on July 22, 1499. The population then suffered particularly up to the signing of the peace treaty on September 22, 1499 in Basel.

“In older historiography, the peace of Basel was seen as a decisive step towards the independence of the Confederation from the Reich. After the war, however, the Confederations expressly asked that their connection to the Reich be maintained or restored, although now exempt from taxes and court oversight on the part of the Reich. ”The Confederation only became formally independent of the Reich in the Peace of Westphalia of 1648 In 1501 Basel and Schaffhausen joined the Federal Confederation, which developed into the Thirteen Old Places .

The Küssaburg was returned to the Count of Sulz by the Zurich residents in October 1499.

"The humane balance of the war was over 20,000 casualties, around 2,000 cities, villages and castles that were completely or partially destroyed and a country devastated in a wide area."

Modern times (16th to 20th centuries)

After the destruction in the Swiss War in 1499, Rudolf V rebuilt Tiengen Castle and made it his ancestral home. As an extension of an existing letter of protection, Archduke Ferdinand I. Count Rudolf granted funds in 1523, which were to be paid out via the Tyrolean Chamber in Innsbruck, for the expansion of the Sulzer fortresses of Vaduz and Küssaburg. Due to the financing, Count Rudolf assured the Archduke that both fortresses would be “open forever” to the imperial troops.

Bild-Dokument 1515

The first known contemporary depiction of the Küssaburg is on a fresco on the north wall in the so-called “ballroom” of the prelature of the former St. Georgen monastery in Stein am Rhein . It is part of those wall paintings that were named in the specialist literature Zurzacher Messe . The fair in Zurzach was an important market in southern Germany in the Middle Ages. The fresco was created around 1515. Participating painters: Tomas Schmid and Ambrosius Holbein . The picture must be based on the sight of the castle before it was converted into a fortress (from 1529).

In the 16th century, those who up until then had always been used as serfs , as (slaughter) victims, as a 'maneuvering mass' rose for the first time: in the peasant war. They found support in numerous cities which, through money, established themselves as a power factor against the nobility and the church.

background

The Peasants' War from 1524 to 1526 is part of a long series of European uprisings and resistance actions that stretch from the late Middle Ages to modern times. As early as the 13th and 14th centuries, farmers had risen in Switzerland, Flanders and England, and in the 15th century in Bohemia.

The high nobility was not interested in a change in the living conditions of the peasants, the lower nobility was heading towards decline and had to struggle with a dramatic loss of power. The attempt of many lower nobles to stay afloat through robber barons was largely at the expense of the peasants. The church was also against any change - hardly a monastery existed without associated villages. The only reform efforts aimed at the abolition of old feudal structures came from the growing bourgeoisie in the cities.

The Küssaburg in the Peasants' War

"In May 1524 the farmers [in the Albgau] refused to pay the owed taxes to the St. Blasien monastery, on June 23 the farmers of the Landgraviate of Stühlingen revolted and in August [...] allied themselves with the town of Waldshut." They found in Hans Müller von Bulgenbach became a war-experienced leader, rejected requests for submission, also won the Hegau farmers, achieved some advantages and remained unmolested in winter. The Klettgau farmers, who were under the protection of the city of Zurich, were initially reluctant, but at the end of October 1524 they too “refused to obey the bailiff Johann Jakob von Heidegg, who resided in the Küssaburg. […] At the invitation of Archduke Ferdinand, the farmers were supposed to submit their complaints to an arbitration tribunal in Stockach and refrain from further riot. Their answer was the siege of the Küssaburg in January 1525. […] The efforts of the city of Zurich to bring about an agreement between the peasants, who had submitted their complaints and demands on 44 points, and the Sulzian rulers, remained without result neither side wanted to give in. "

“Due to the general fire that started in the spring of 1525, the gentlemen were initially powerless [...] Hans Meyer, the Wagner of Grießen, ruled the Klettgau for about six months. He decided everything at his own discretion and played the judge in disputes, as was otherwise the rule. "

“In June 1525 the farmers moved again in front of the Küssaburg and demanded in the name of 'the County of Klettgau including the whole Evangelical Brotherhood' the bailiff to open and hand over the castle, 'because we are greatly burdened by this castle.' Since the active help expected from Zurich failed to materialize, the farmers agreed to a ceasefire that lasted from June 29th to St. Verena Day (September 1st). The Klettgau peasantry immediately refused to approve the contract negotiated with their representatives in Radolfzell on July 25th. "

In the meantime, however, the Swabian, Hessian and Alsatian farmers had suffered devastating defeats and the Odenwälder, the Allgäu and the Black Forest Haufe were also defeated. “On the whole, the Stühlinger escaped terrible, violent submission. On July 12th, 1525, however, they had to pay homage again to their master in a very humiliating manner in Ewattingen. ”Hans Müller was executed on August 12th, 1525 in Laufenburg.

The Klettgau farmers were able to hold out for a few more months because “they didn't expect much from the grace of their master. Archduke Ferdinand therefore called on his lords and cities to move to the Klettgau. And they came from all sides, because otherwise the farmers everywhere had been violently thrown down. "

In vain did the people of Klettgau besieged the Küssaburg and ...

“... the decisive battle took place on November 4, 1525 near and in Grießen, where around a thousand Klettgau farmers, supported by a small group of confederates, had gathered. They faced 1,000 foot soldiers and 500 horsemen under the command of Rudolf V. von Sulz and 1,000 foot soldiers under the command of knight Christoph Fuchs von Fuchsberg . According to the Villinger Chronik von Hug, 500 farmers died in a grueling battle, while Heinrich von Küssenberg gives the number of fallen soldiers as 200 in his chronicle [...] The Gottesacker had become a refuge for around 300 farmers until they had to surrender after midnight. Many also found death in the houses set on fire by the soldiers. "

Emil Müller-Ettikon wrote about the last defense lawyers: “Count Wilhelm von Fürstenberg (went) to them and encouraged them to surrender, he would guarantee their lives. 350 men surrendered. The Fürstenberger was scolded badly for having promised them his life, but the gentlemen would not let him break his word. 14 ringleaders were led captive to the Küssaburg, the others had to swear to unconditionally surrender to grace or disgrace. [...] Count Rudolf had Captain Klaus Meyer's eyes gouged out and his oath fingers chopped off. ”The Zwinglican Reformed preacher of Grießen Hans Rebmann , arrested on November 11, was also blinded at the castle the following day. Out of consideration for Zurich, Rudolf V. von Sulz was subject to the death penalty for high treason. In addition to monetary payments, the villages of the Klettgau had to pay their largest church bell to the Küssaburg. They were cast into guns for the fortress.

Regulations were imposed on the peasants "which sealed complete defeat and servitude."

Expansion of the Küssaburg into a fortress

From 1529 onwards, the Küssaburg was expanded into a state fortress with Austrian money. In 1548, after the death of Count Hans Ludwig von Sulz, the Bishop of Constance Johann von Weeze tried to buy back the pledge for Tiengen and the Küssaburg. However, he received no response from the pawnbrokers to his offer. In 1558, when Sulzer pledged parts of Tiengens and the Küssaburg to the Margrave of Baden, the city of Zurich was even more annoyed. In fact, the pledge was opened in the territorial state. A bilateral agreement was only reached in 1575 by a decree of the emperor. The pledge agreement for Tiengen and the Küssaburg was legally converted into a pawn loan by the diocese of Constance. After the death of the last male descendant of the direct line Sulz-Brandis, this should revert to the diocese of Constance.

Thirty Years War (1618 to 1648)

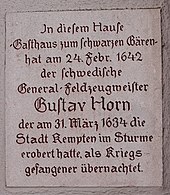

The religious disputes in Christianity after the Reformation of Martin Luther led in the early 17th century through numerous smaller armed conflicts to a European war in which the religious image was based on political interests. “After the outrage of the Bohemian estates against Emperor Ferdinand II , the war began in 1618, in which initially only the Protestant princes and cities united in the union and the imperial cities united in the Catholic league faced each other, but this was due to the interference of Sweden and France assumed ever greater proportions. ”For a decade and a half, southern Germany was spared acts of war,“ before the first enemy troops, the Swedes, defeated General Count Horn in 1632 after their victory in the Battle of Lützen and their horrific atrocities march Upper Rhine and in Breisgau on the Upper Rhine showed and invaded Klettgau under the Scottish Count Hamilton . "

The region could no longer be used as winter quarters and so the Swedes and shortly afterwards their French cavalry withdrew again in autumn 1633.

The Swedes on the Upper Rhine 1633

"The Swedes came to the Klettgau at the beginning of 1633." The local historian Alois Nohl quotes "a letter from the mayor and the councilors of the city of Zurich of February 19, 1633" in which this was for the residents of the Landgraviate of Klettgau, who are Zurich “affectionate and related in an eternal castle right”, asked for leniency, since “an impossible contribution is required from the subjects who have been almost impoverished for several years [...].” The letter was addressed “to Baron von Andre Montbrun, Royal Swedish Colonel ”and asks the Swedish General Field Marshal Horn to hold back by force in Klettgau. The Swedes and their French auxiliaries did not consider complying with Zurich's request and behaved no differently than they had on their approach in the Upper Rhine area.

“In a battle on May 7, 1633 near Lottstetten between a 300-strong French cavalry unit who served under Swedish flags and farmers from Klettgau, 150 of the 600 farmers were killed, a large part captured and the others chased away. The then Lottstetter pastor recorded the dramatic events in a report in the church register. In revenge for the attack by the peasants, Colonel Villefranche had Lottstetten burned down on May 8, 1633 'in such a short time that everything burned in one hour and a second.' In the following days Jestetten, Erzingen, Grießen and almost all Klettgaudörfer were plundered, houses set on fire and the population tortured. "

The local history researcher Alois Nohl from Geißlingen documented the following months: “On May 28, 1633, the French under René du Puy-Montbrun plundered the villages of Erzingen and Grießen and caused great damage. The French drove the imperial soldiers from the Küssaburg and occupied the castle. […] On October 18, 1633, the French withdrew from the Küssaburg. As a result, the Küssaburg Castle was again occupied by imperial soldiers. "Nohl documents on November 2, 1633 and January 1, 1634" Imperial soldiers on the Küssaburg "and:" Captain Lauterberger on the Küssaburg castle commandant. "

Destruction of the Küssaburg on March 8, 1634

When the 'Swedish Army' approached under General Gustav Horn ', the castle was' set on fire and abandoned by its own crew', is the reason for the destruction that is still widespread today. The origin of this representation can currently be traced back to Jürgen Meyer von Rüdlingen, who wrote in 1866:

"Küssenberg was [...] now subject to the imperial family, now to the Swedes, until 1634, when the latter again approached under Franz Horn, who withdrew the too weak garrison and surrendered the magnificent fortress to the flames."

Perhaps Meyer took over the representation of Joseph Bader , whom he quotes in a different context, but complains there that he does not name his sources. Both authors come from the intellectual epoch of Romanticism , which aroused an emotional interest in history (ruins as monuments instead of quarries) and a tendency to transfigure historical situations into victory as well as defeat. Only an entire army could be considered for the downfall of the “magnificent fortress”.

What is striking about Meyer is the incorrect naming of the Swedish general's first name: Gustav and not "Franz Horn". The depiction of the approach of the army under Horn was probably already widespread in the 19th century - in the post-war period Ernst Wellenreuther kept a low profile in 1965/66 when he only wrote about the “fire of 1634”. 20 years later, however, he gives the 'general version': “On March 8, 1634, the castle, which was occupied by an imperial troop, was abandoned by the garrison and set on fire when the Swedish army under General Horn approached. The castle crew shied away from sieges and fighting. "

A “siege” of the castle is even listed on the notice board on the right at the gate entrance to the castle.

Obviously, no author asked himself why the “Swedish army under General Horn”, which had devastated the Klettgau in the summer of 1633, plundered and burned the villages, should “advance” again at the beginning of March 1634. The agreement on the process (most recently with Andreas Weiß and Christian Ruch: Die Küssaburg. 2009.) was only questioned by Alois Nohl, Geißlingen, 1994:

The bells of Wilchingen

“When the storm bells rang in Wilchingen on March 8, 1634 and were replied by the neighboring villages, the Küssaburg crew took this as a sign that the Swedes were approaching again. The imperial garrison therefore set fire to the castle and fled. Later it turned out that a fire had broken out in Wilchingen, which is why the storm bells were rung. "

Nohl gives no evidence of this and there is no mention of a fire in the Wilchingen chronicle . Nohl's account was not included in the discourse of historians in the Waldshut district. Church bells were also used to warn against foreign armies.

Swedish army in the winter of 1633/34

If the Swedish Army (then about 30,000 armed men) had marched towards Klettgau at the beginning of March 1634, they would certainly have left winter quarters. This conclusion is of a logistical and logical nature and was not considered in local history research. An examination of the facts today reveals sufficiently documented findings:

- After they had thoroughly devastated and plundered the Klettgau, the Swedes left the scorched landscape in September 1633. Horn moved to Constance , but had to end the siege of the city on October 5, 1633 because of the imperial fleet that ruled Lake Constance . The troops remained in the Upper Swabian-Bavarian region and were found from January 1, 1634 to March 19, 1634 with Gros (General Horn) in the winter quarters in Pfullendorf.

This representation in the source from 1825 already takes up the period in which the Swedish army should have moved into the Klettgau. The other information shows that it was also in the Swabian-Bavarian region in the following months:

- Kempten: The city was conquered on March 20, 1634 by General Horn's army in a coup.

- Biberach :

"The Imperial [...] took over the city on September 27th. But already on March 25, 1634 , the Swedes recaptured the city. "

- On April 8, 1634 Gustaf Horn's army, which was being pursued by the Bavarian Catholic League Army under Aldringen , united with Duke Bernhard's army between Donauwörth and Augsburg.

See: Battles around Regensburg (1632–1634)

- The following information can be found about the history of the city of Memmingen :

In the spring of 1634 there was a siege of the city by Swedish troops of Field Marshal Gustaf Horn , who camped near Buxach and Amendingen. On April 12, the Vorwerk in front of the Niedergassentor was shot at with 4 half cartoons that had been brought from Augsburg and Ulm. In the evening of April 13th the big hill was stormed, with 250 dead on both sides. On April 14th, the city was handed over to the Swedes by the commandant Gerhard Graf von Arco, with 400 men of the garrison going over to the Swedes.

“On April 23, 1634 the siege of the city of Überlingen began . General Horn ran against the city walls with such force that the thunder of the artillery and the many catapults against the walls amounted to a continued earthquake. Although the Swede fought like a lion and tried to unnerve the besieged people with the thunder of the guns, all efforts of the enemy were in vain. The Swede had to give up the siege ring around the city on May 16, 1634 and leave the city of Überlingen. "

General Horn then moved north with his army.

Military situation spring 1634 Hochrhein / Bodensee

In the winter quarters of 1633/34, the Swedes had arranged the territorial power of disposal in the western part of Austria (southern Germany). The Swedish Chancellor and Plenipotentiary on the Rhine, Axel Oxenstierna , who held the political leadership and also planned the military operations with Horn, his son-in-law (1628), appointed Horn's deputy, Major General Bernhard Schaffalitzky , as Commander-in-Chief at a convention in Frankfurt at the end of 1633 over the Black Forest, Upper Swabia and Lake Constance.

Schaffalitzky's regiment, a foot troop, was in Ellwangen in the winter quarters, his drafting place was Reutlingen. At the beginning of March Schaffalitzky set out with 800 lightly armed soldiers [according to Thomas Mallinger] across the Wutach Valley to the Upper Rhine. Apart from the fact that this was the shortest connection, the Landgraviate of Stühlingen belonged to the Heilbronner Bund at that time . The looting of the St. Blasian Fützen in March 1634 can also be classified in this context. The arrival of Schaffalitzky and the abandonment of the Küssaburg coincide in time. Apart from the von Schaffalitzky troops, no regular units of the Swedish alliance operated in the region around the Küssaburg in 1634.

According to Friedrich Wernet, the clashes in the region took on the form of gang fights:

“On March 8th, Küßnach was robbed. Lorraine, Croatians 'and other rabble' were in the imperial troops. They lived as badly as the Swedes who looted Fützen on March 10th . [...] The guerrilla war began, initially in the Black Forest. Everyone beat everyone to death. The difference between friend and foe disappeared. "

Schaffalitzky had already occupied the abandoned Waldshut in mid-March: “Eodem (March 12, 1634) Colonel Schabalitschgi arrived in the Waldstätten with 800 men. Waldshut, because it was abandoned, taken and occupied, also attacked Lauffenburg in different ways, but was driven off again. ”Via St. Blasien, where he presumably obtained contributions, Schaffalitzky reached Freiburg, which the Swedes conquered on April 11, 1634. The Swedes were now “at the peak of their power” in the imperial empire. But on September 5 and 6, 1634, the united Swedish armies were defeated by an imperial Bavarian army in conjunction with a Spanish army in the battle of Nördlingen .

For the small castle garrison it had not played a decisive role whether an entire army or a kind of 'reaction force' like the Swedish regiment with 800 men was on the march, and the enemy should not be left with a facility suitable for occupation.

Alois Nohls: “The destruction of the castle was not as great as today's visitor might assume. The fire in the castle was limited to the combustible wooden parts. The wine-red discolouration on the stones of the interior, which can still be seen today, are traces of the fire of 1634. After the castle was destroyed, the ruins served the surrounding villages as a quarry until the middle of the 19th century. For example, stones were verifiably fetched for the construction of the Oberlauchringer mill, for the church in Schwerzen , and for the construction of the stations in Tiengen from the Klausenkapelle to the Kreuzkapelle. Stones from the ruins were also used to build the courtyards near the Küssaburg. "

After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, plans for reconstruction were considered, but were not implemented due to unprofitability. The castle, which was no longer of any strategic importance, continued to deteriorate. It remained in the possession of the Prince of Schwarzenberg until the Grand Duchy of Baden acquired the Klettgau in 1812 . In 1855, further decay and use as a quarry were stopped.

Rockslide on December 25, 1664

The illustration that a landslide caused further major damage to the castle, which was partially destroyed by the fire, goes back to Ernst Wellenreuther, 1965/66, with reference to a contemporary illustration by the engraver Conrad Meyer.

Wellenreuther assumes “that at that time it was still largely preserved, and that a second, even more serious event than the fire of 1634, of which historiography has not yet reported anything, completed the work of destruction.” The engraving [see Picture] is provided with a text that Wellenreuther only partially quotes in the original: “This mountain slide happened at night, between nine and ten o'clock, with a four-hour terrible echo, of falling trees, and rock-hard gneissing ashlar stones - before decay dises Almost unknown place is no one but those who come there who have painted the game or otherwise climbed up wonderful mountains. "

However, Wellenreuther did not quote the heading to the above text:

“Actual demolition of the strange mountain fall on the Küssenberg; Called Heidenstatt; next to Geislingen in the county of Sulz [date unclear: possibly December 25th] 1664 on the Geislinger Kirchweihungs-Tage. "

In the text quoted first, the information that it is supposed to be an 'almost unknown place' is irritating, which is hardly credible in relation to the Küssaburg, but is not yet counter-evidence. The place is called 'Heidenstatt': after an old name of the Gewann in Klettgau on the mountains east of today's Geißlingen. It is noticeable that the forest extends in full size over the drawn walls, as if they had been hidden and only emerged through the slope slide. This is reminiscent of the image that often exposed Jura limestone layers offer: rock broken into horizontal lines, vertically divided into cuboids. One could recognize (from a distance) former walls - a "pagan city". This assumption is underlined by the fact that at the mountain height next door - east towards Geißlingen - a large landslide can still be seen today, which has the rock pattern described above at the edge of the break.

The further assumption by Wellenreuther, "The earthquake caused by the landslide undoubtedly brought down all of the medieval buildings that stood inside the castle," is speculative on this basis. Wellenreuther's hypothesis was not taken up by later authors. The landslide actually took place - but on the hill east of the mountain bearing the Küssaburg:

“From the Küssaburg, a series of mountains stretches towards the east in beautifully curved lines. The first of them, half an hour away from Geißlingen, shows a location that stands out due to its name, the so-called Heidenstatt Wall. […] In a report by the geological state institute in Freiburg on December 2, 1933, the geologist Dr. C. Schnarrenberger already back then the mountain fall on the Küssaburg. "

Prince of Schwarzenberg

The ruins of the fortress, which had no further strategic importance, continued to deteriorate. After the death of the last male Count von Sulz, the pawn loan from Küssaburg would have been legitimately returned to the diocese of Constance. Johann Ludwig II. Von Sulz prevented this with a Fideikommiss - and Primogenitur - disposition in favor of his daughters. Through this inheritance construction of Klettgau 1698 elevated to princely Landgraviate came over the marriage of Maria Anna of Sulz Ferdinand von Schwarzenberg in 1703 as a whole at the Haus Schwarzenberg . Since then, the Schwarzenbergs have also held the title of Count von Sulz and the Landgrave of Klettgau . The administrative seat of the Schwarzenberg rule in Klettgau was Tiengen Castle. Until the acquisition of the Klettgau by the Grand Duchy of Baden in 1812, the Küssaburg remained in the possession of the Prince of Schwarzenberg .

Küssaburg as a ruin

The castle was not rebuilt, but it was not preserved either:

“The destruction of the castle was not as great as today's visitor might assume. The fire in the castle was limited to the combustible wooden parts. The wine-red discolouration on the stones of the interior, which can still be seen today, are traces of the fire of 1634. After the castle was destroyed, the ruins served the surrounding villages as a quarry until the middle of the 19th century. For example, stones were verifiably fetched for the construction of the Oberlauchringer mill, for the church in Schwerzen , and for the construction of the stations in Tiengen from the Klausenkapelle to the Kreuzkapelle. Stones from the ruins were also used to build the courtyards near the Küssaburg. "

These measures required at least the approval of the Tiengen building inspector Paul Fritschi. On May 31, 1855, the Waldshut building inspection received the order from the Directorate of Forests, Mining and Metallurgy in Karlsruhe to develop the ruin without disturbing its character.

Excavations and reconstructions

In the 19th century, “along with the Romantic era, the sense of looking after and maintaining the ruins, which had become state property, awoke. In 1855, the spiral staircase between the gate and the eastern battery tower [Tower I] was renewed and the ground-level embrasure to the north was expanded to form an entrance. "At that time there was no drawbridge and rubble was meters high behind the gate.

Exposure 1896–1900 From

1896 to 1897 the first systematic excavations were carried out in the ruins. The excavation finds came into the possession of the grand ducal collection for antiquity and ethnology in Karlsruhe. A high-quality green glazed stove tile from the second half of the 15th century, which was found behind the Pallas Gate, is still part of the exhibition on the subject of the late Middle Ages in the Baden State Museum . The square tile shows a couple making music at the fountain (inventory number C 7673 Landesmuseum Karlsruhe). The representation is based on a reverse copper engraving template by the master ES (L 203).

The south-western tower III was excavated - “the stairs to the lower floors of this tower were still hidden”, the opposite gate into the interior of the castle was uncovered: “At the height of the wheel axis, it was worked out so that with the narrow door width of 1.63 meters a car could just drive through. ”Inside the roundabout, a waste pit and a foundation wall with parts of millstones and grindstones were found. In the southeastern "Tower II", the staircase to the basement was exposed, as well as the courtyard pavement around the cistern and a "second walling of the shaft, which was thus carefully protected against water loss and contamination. Parts of a tiled stove were found behind the large pallastor. Some well-preserved tiles, one of which bore the inscription 'Maria', were given to the Grand Ducal Collection for Antiquity and Ethnology in Karlsruhe. "

Excavations 1933 to 1939

Under the direction of government building officer Siebold (Waldshut district building authority), the castle complex was then completely exposed. "After the entire ruined area had been cleared of the lush undergrowth, around four thousand five hundred cubic meters of rubble, up to three meters high, had to be removed." The kennel in particular was cleared out, and there were also many monk and nun bricks here. “Step by step, the masonry was repaired with the uncovered.” Finds worth mentioning: door and window fittings, parts of weapons and armor, an iron figure holding a coat of arms, various knives, keys, bronze needles and coins.

“On the bottom of the cistern, which was dug up to its eight meter deep bottom, a halberd with remains of wood, a well-preserved ball pouring apparatus and a copper pan came to light. Unfortunately, these objects, which were supposed to form the basis of a Küssaberg museum, were stolen during the past war. "

Building structures are now recognized, such as a second gate within the Zwinger, the kitchen in the inner northern area and the Pallas kitchen between the keep and the gate building. The renovations and new buildings between 1525 and 1529 can be identified more precisely.

During the war and after the war, building maintenance was interrupted - “because of the threat of collapse of entire walls, the castle grounds had to be closed in 1955.” One of the merits of the excavation work in the 1930s was “that construction supervisor Emil Müller (Waldshut) was able to uncover it To measure the castle precisely and to record it in drawings on a scale of 1: 200. "

These plan drawings provided the basis for reconstructions carried out by Ernst Wellenreuther in 1965 and Paul Klahn jun. 1996 were made.

Reconstructions

Both works were based on the state of the castle "after it was converted into a 'cannon fortress' (1525–1529)" (Klahn). The most important differences lie in the fact that Wellenreuther regards the keep as preserved, while Klahn accepts it as no longer protruding part of a significantly enlarged Pallas and, in contrast to its predecessor, regards the roundabout as completely built over. Klahn assumed a higher space requirement than Wellenreuther. In his enlargement of the Pallas he started from the representation of the castle from 1480, which “in the monastery of St. Georg in Stein a. Rh. Hangs. ”Both authors otherwise refer to an“ engraving from the 18th century, which shows the front view of the castle Küssenberg true to detail ”(Klahn) or“ a true picture of the ruins of the time from the east side. It shows that the inventory at that time was not much more extensive than it is today. ”(Wellenreuther).

Coat of arms above the castle entrance

Today it can no longer be proven with certainty which coat of arms was originally attached above the castle gate.

Johannes Meyer von Rüdlingen, 1866, wrote:

"The sandstone still stands above the arch of the gate, on which the coat of arms of the Küssenbergers 1) once shone." Under note 1) he quotes:

1) "Fr. Hurter, a day on Küssenberg, p. 19, says that this coat of arms was a lion's head, according to Mone, Zeitschr. f. Business d. Oberrheins Bd. 3, 253, shows the seal of Count Heinrich von K. in his shield three lying crescent moons. "

Against Alfred Nohl:

"A hiker who visited the ruins around 1800 saw the coats of arms of the bishops of Constance and those of the Counts of Sulz still attached."

The sovereign situation of the Küssaburg as a result of the pledge agreement speaks for such a double coat of arms. A rough illustration of the double coat of arms can be found on the ruins of Johann Melchior Füssli . According to Franz Xaver Kraus, who refers to Christian Roder, the coat of arms stone was stolen around 1847 and made into whetstones. Detailed images of the coats of arms are not known.

The current coat of arms above the reconstructed castle entrance was made in 1983 by the sculptor Ernst Keller from Lottstetten based on a design by the Waldshut government building officer Ernst Wellenreuther. The colors are indicated by the different structuring of the surface. Wellenreuther based his representation on the younger coat of arms of the Counts of Sulz in Johann Siebmacher's coat of arms book from 1605. The bishop's cap can be traced on the Sulzer coat of arms since the end of the 14th century and has no relation to the diocese of Constance.

The coat of arms is recorded as a small monument as follows:

Registration sheet for small monuments

Kenn – Nr. 6980.06.08 Kurzbezeichnung: 0608 Objekt: Wappen über dem Hauptzugang zur Küssaburg. Kartiert: Juni 2012 Landkreis: Waldshut Gemeinde: 79790 Küssaberg

Ortsteil: Bechtersbohl, (Gemarkung Bechtersbohl). Früher bestand eine eigene Gemarkung „Küssaberg“. Gewann: Distrikt Schlossberg Flurstück: 801, Eigentümer: Landkreis Waldshut. Ruine Küssaburg, östliche Fassade, Eingangsgebäude.

Karte DGK 1:5000 – Blatt „Bechtersbohl Süd“ Nr. 8416.1 Rechtswert: 34.51.520 Hochwert: 52.73.955 Art des Kleindenkmals: Wappentafel neueren Datums. Datierung: 1982 ermittelt aus den Akten.

Description according to W. Pabst: The board shows the coat of arms of the Counts of Sulz in two coat of arms fields, three points pointing upwards. In two other fields of coats of arms you can see a burning branch, which is borrowed from the coat of arms of the noble free von Brandis, whose castle was near Vaduz. The coat of arms of the von Brandis family came through the marriage of Verena von Brandis into the coat of arms of the Counts of Sulz. The "Sulzer" were the last owners of the castle before it was finally destroyed in 1634 during the Thirty Years' War. […] The left of the two tournament helmets on the coat of arms has a bishop's miter. This representation is intended to remind us that the castle was owned by the Konstanz Monastery from 1245 to 1497. [...] In his epic “Elsbeth von Küssaberg”, the poet Karl Friedrich Würtenberger writes that he saw “a coat of arms with the head of a lion” above the entrance to the castle.

The Küssaburgbund is responsible for maintaining the castle as a cultural and historical monument .

Küssaburg Bund

"The local writer Samuel Pletscher (founded) the first Küssaburg-Bund on June 3rd, 1893, based in Oberlauchigene, which only existed for a short time."

The Küssaburgbund was re-established in the course of the excavations in the 1930s in 1934 and revived by District Administrator Wilfrid Schäfer in 1956. District administrator Schäfer's successor as chairman was Franz Schmidt, former mayor of Tiengen, who, together with mayor Berthold Schmidt von Lauchringen, took over the castle in the summer of 1978 by the district of Waldshut under district administrator Dr. Emergency aid provided. "In addition to the conservation work on the wall surfaces and crowns, which is always necessary, the reconstruction of the castle gate building with the installation of a drawbridge was carried out as an outstanding work."

Working drawbridge

"The restoration of a fully functional drawbridge [...], a drawbridge that existed several hundred years ago (... should) take more than two years." The completed Küssaburg drawbridge was put into operation in 1981 by carpenter Josef Morath. The mechanism was adjusted so precisely that “from an angle of 45 degrees the bridge closed by itself.” In 1996, the now more difficult function was compensated for by strengthening the counterweight. The current version of the drawbridge dates from May 2017.

A detailed description of the castle ruins can be found at: Entry on Küssaburg in the scientific database " EBIDAT " of the European Castle Institute

The Küssaburg in art

- On the cycle of frescoes by David von Winkelsheim on the north wall in the ballroom of the St. Georgen monastery in Stein am Rhein , Ambrosius Holbein depicted the Zurzach mass in 1515 . At the top right in the background is an ideal representation of the Küssaburg.

- For the fresco see: Mural in the monastery

- Another illustration of the undestroyed castle can be found in the Stumpf Chronicle from 1548 at the top right of a woodcut from the Zurzach fair.

- A miniature view of the still undestroyed fortress can be found on a Hans Conrad Gyger military map .

- A view of the ruins from a distance shows Merian's Zurzach view from 1654.

- Conrad Meyer wrote the single-sheet print Actual Outline of the strange mountain fall on the Küssaberg. by 1665.

- Three views of the castle, including a detailed representation of the east side of the ruin with the gate entrance, were published by Johann Caspar Ulinger in 1730 at Johann Andreas Pfeffel in Augsburg based on drawings by Johann Melchior Füssli .

- Around 1735 the ruin is shown in a view of Tiengens by Johann Heinrich Meyer (1688–1749). A free depiction of the ruins from the second half of the 18th century in oil is kept in the Tiengen Local History Museum.

- Joseph Mallord William Turner's Ruined Castle among Trees; Küssaberg near Lauchringen 1802. , is preserved in the Lake Thun Sketchbook in the Tate Gallery London.

- An ink drawing of the Küssaburg by Maximilian von Ring , dated 1828, is kept in the collection of the Augustinermuseum in Freiburg and served as a template for Plate 14: Kussenburg, in: Picturesque views of the knight's castles in Germany based on the original drawings by Mr. Maximilian von Ring. The Grand Duchy of Baden, 1: Southern part from the Kinzigthale to Lake Constance, Strasbourg, Levrault 1829.

- In the second third of the 19th century, there were two depictions from the west side, the one in 1839 in the first volume of Joseph Bader's Badenia. after page 34 were published.

- The castle researcher Eduard Schuster published drawings of the ruin in his publication Die Burgen und Schlösser Baden in 1908 .

- In the 1960s, the Küssaberg was a popular motif of the local painter Christian Gotthard Hirsch .

- A curiosity is the pewter panorama of the peasant war in Klettgau (Upper Rhine), the Küssaburg and the battle on the Rafzer Feld on November 4, 1525 , depicted in pewter figures and landscape models by the pewter figure hermitage in Freiburg's Schwabentor.

- A tribute to the castle in the history of technology is that the first steam locomotive put into service on the Hochrheinbahn was named after the Küssaburg. With it, the completed Basel-Konstanz line was opened on June 15, 1863.

Remarks

- ↑ The Chronicle of Lauchringen , which refers to a history of over 30 years (1953–1985) and has a volume of 736 pages, can be considered a historical and scientific standard work for the eastern area of the Waldshut district due to detailed research of sources. This is based on the fact that the district Oberlauchringen belonged to the Landgraviate of Klettgau, the district of Unterlauchringen to the Landgraviate of Stühlingen, so that the history of today's community required research into the history of both counties. The Küssaburg, which today belongs to the municipality of Küssaberg , is considered by the authors to be "connected in many ways (with the history of Lauchringen)", so that the history of the castle is given appropriate consideration.

-

↑ The historical documents (1st half of the 15th century Kussach , 1500 Küssnacht etc.) indicate that the place Küßnach was in Old High German times

- Kussinaha was called. The defining word is the personal name Kusso , in the genitive Kussin . Either originated from Kussinaha

- Küssenach ( Küssnach ) or by deleting the genetic ending -in Küssach .

- Kussin-oh-berg . Such tricomposites have a tendency to be shortened, for example in that the middle link shrinks:

- Kussinberg (compare 1168 Chussenberc ). But it could also be shortened by using the short form of the hydronym ( Küssach or Küssa ) as the defining word , compare approx. 1216

- Chussachperg and 1239 Kussaberg . (Albrecht Greule: names of waters in the district of Waldshut. , 1984, p. 93 f.)

- ↑ "The name Küssnacht is a formation from a Latin personal name such as Cossinius, Cossonius, Cusin (n) ius or similar, as well as the Celtic place name ending -akos / -acum and thus means 'country estate of Cossinius'. The place name goes back to a time when the Celtic population began to use Latin personal names. ”( Lexicon of Swiss community names. Ed. By the Center de Dialectologie at the University of Neuchâtel under the direction of Andres Kristol. Frauenfeld / Lausanne 2005, p . 492.)

- ↑ A 'Gotzbert' is not listed in the list of Welfs . The list of abbots of Rheinau names an abbot "Gozbert" in fourth place, who took office in 888. Text W. Pabst on Fig. 2 .

- ↑ The certificate of 13th Martii 1251 in German has been preserved from the Tiengen archive and was printed in: ( Georg Wilhelm Zapf , Monumenta Anectdota etc., 1785. Volume 1, p. 482 ff. It is unclear who at this time of the Interregnum - "the imperial time" - made the decision in the "arbitration settled" dispute.

- ^ Johannes Meyer von Rüdlingen: Küssenberg in the Baden Klettgau. Schaffhausen 1866, p. 24, mentions "Küssenberger Schloß und Thal" with four communities, without Bechtesbohl.

- ↑ Presumably the name Schultheiss for the local superior of Bechtersbohl, which is nowhere to be found in the Landgraviate of Klettgau, goes back to the former mayor of the outer bailey or town of Küssenberg. (Brigitte Matt-Willmatt / Karl-Friedrich Hoggenmüller: Lauchringen. Chronicle of a municipality. Ed .: Municipality of Lauchringen, Mayor Berthold Schmidt, 1985, p. 41.) Also remarkable is the award of 'urban privileges' insofar as Ulrich Pfefferhard calls it “A citizen as a bishop ”. (Andreas Bihrer: A citizen as bishop. The Bishop of Constance Ulrich Pfefferhard (1345–1351), his court and the city. In: Thomas Zotz (Ed.): Princely courts and their outside world. Aspects of social and cultural identity in the German late Middle Ages (Identities and Alteritäten; 16). Ergon-Verlag, Würzburg 2004, ISBN 3-89913-326-9 , pp. 201-216).

- ↑ The center of the Sulzer Counts was in the area between Rottweil and Sulz - in the west their influence extended to the Black Forest, to the south and east to the Alb areas.

- ↑ "In three different chronicles (Berner, Villinger and Zimmerische Chronik) (it is stated) that the wife of Count Sigmund II. Von Lupfen, Clementia née von Montford, asked the peasants to collect snail shells for their maidservants during the harvest season, so that they could wind their yarn on it. ”If it was factual, this could have been the reason that 'broke the barrel', because the causes“ (conjured up) the excess of taxes, compulsory labor and sovereign claims, the suppression of freedom , the arbitrariness of the officials and other more the indignation. "(Gustav Häusler: Stühlingen. Past and present. Self-published by the city of Stühlingen, 1966, p. 23.)

- ↑ A. Nohl: The Thirty Years' War and the Destruction of the Küssaburg , 1994, p. 45. Since the Swedish army under General Horn was besieging Constance from September onwards, the French troops will have been a rearguard, the most important base Küssenberg kept busy for a while. On October 5th, the Swedes gave up the siege of Constance and moved on to Bavaria. Then Ville Franche should have followed suit.

- ^ Ernst Wellenreuther: 350 years of ruin Küssaburg in: Heimat am Hochrhein, yearbook of the district of Waldshut 1985, Verlag des Südkurier, Konstanz 1984, p. 183.

- ↑ It may have been Schaffalitzky's primary goal to establish himself on the fortress. This would have built a bridge between the Landgraviate of Stühlingen, which is part of the Swedish alliance, and the reformed canton of Zurich. Since the small imperial garrison of the castle was hardly able to successfully resist, it makes perfect sense to burn the castle down by rendering it unusable. This episode, insignificant for the course of the war, is usually left out in later historiography. It is documented in Thomas Mallinger's contemporary diary.

- ↑ "The Central Library of the City of Zurich has an engraving from around 1700 depicting the Küssaburg with a landslide that affected the castle on December 25, 1664." (Wellenreuther, 1965/66, p. 10.)

Web links

- Reconstruction drawing by Wolfgang Braun

literature

Factual publications

- Helmut Bender, Karl-Bernhard Knappe, Klauspeter Wilke: Castles in southern Baden. Schillinger, Freiburg im Breisgau 1979, ISBN 3-921340-41-1 .

- Robert Feger , castles and palaces in southern Baden. A selection. Weidlich, Würzburg 1984, ISBN 3-8035-1237-9 .

- Albrecht Greule : names of waters in the district of Waldshut. In: Heimat am Hochrhein 1985 . Südkurier Verlag, Konstanz 1984, ISBN 3-87799-053-3 .

- Arthur Hauptmann: Castles then and now - castles and castle ruins in southern Baden and neighboring areas. Verlag Südkurier, Konstanz 1984, ISBN 3-87799-040-1 , pp. 259-263.

- Brigitte Matt-Willmatt, Karl-Friedrich Hoggenmüller: Lauchringen . Lauchringen municipality (ed.), 1985.

- Hans Matt-Willmatt: Weilheim in the district of Waldshut. The Thirty-Year War. 1977.

- Johannes Meyer von Rüdlingen: Küssenberg in the Baden Klettgau. [4] , Aujourdhui u. Werdmann, Schaffhausen 1866.

- Emil Müller-Ettikon : What the names reveal about the development of the settlements. In: The Klettgau. Ed .: Mayor Franz Schmidt on behalf of the city of Tiengen / Hochrhein, 1971.

- Emil Müller-Ettikon: A brief overview of the history of Küssaberg. Ed .: Municipality of Küssaberg, 1986.

- Alois Nohl: The Thirty Years War and the destruction of the Küssaburg. In: Land between the Upper Rhine and the Southern Black Forest , published by the Hochrhein History Association, Waldshut 1994.

- Norbert Nothhelfer (ed.): The district of Waldshut. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart / Aalen 1975, ISBN 3-8062-0124-2 .

- Wolf Pabst (text and drawings): Small guide through the Küssaburg. Explanations of structural details and history of the castle. 2011. pdf

- Wolf Pabst: coats of arms and heraldic panels. Chapter: No. 6980.06.08, p. 4. pdf .

- Samuel Pletscher: Küssenberg in Klettgau in Baden. Schleitheim, 1883.

- Pierre Riché : The world of the Carolingians. Reclam, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-15-020183-1 .

- Christian Roder : Küssaberg. In: Franz Xaver Kraus (Ed.): The art monuments of the Grand Duchy of Baden , Freiburg im Breisgau, 1892, Volume III - Waldshut district; Pp. 133-142 online .

- Christian Roder: The Schlosskaplanei Küssenberg and the St. Anne's Chapel in Dangstetten. In: Freiburg Diocesan Archive Volume 31 = NF 4, 1903 ( digitized version ).

- Karl Siebold: Ruin Küssaburg. In: Association for the Preservation of German Castles (Hrsg.): Der Burgwart: Mitteilungsblatt der Deutschen Burgenvereinigung e. V. for the protection of historical fortifications, castles and residential buildings. Volume 34 (1933); Pp. 37–39 digitized .

- Jürgen Trumm: The Roman settlement on the eastern Upper Rhine. Issue 63, Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-8062-1643-6 .

- Heinz Voellner: The castles and palaces between the Wutach Gorge and the Upper Rhine. 1979.

- Andreas Weiß, Christian Ruch, The Küssaburg. Published by the Küssaburg-Bund e. V., o. O. 2009.