suicide

|

|

This article is about suicide. For those at risk, there is a wide network of offers of help in which ways out are shown. In acute emergencies, the telephone counseling and the European emergency number 112 can be reached continuously and free of charge. After an initial crisis intervention , qualified referrals can be made to suitable counseling centers on request. |

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| Z91.5 | Personal history of self-harm (parasuicide, self-poisoning, attempted suicide) |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

A suicide (out of date also suicide ; from Latin sui "his [self]" and caedere "to kill, murder") is the deliberate termination of one's life . Suicide , suicide and suicide are used synonymously . The European Court of Human Rights has recognized the right of termination of one's life as a human right on 20 January 2011th

The term suicidality describes a psychological state in which thoughts , fantasies , impulses and actions are persistent, repeated or in critical exacerbations aimed at deliberately bringing about one's own death .

overview

Suicide is a complex phenomenon. According to the World Health Organization, suicide should be considered a "health policy priority" due to its frequency. Suicides can be committed for a variety of reasons; the ideological and legal classification is extremely heterogeneous. While various court rulings in Europe after the turn of the millennium classify suicide as a human right, for example, historically suicides have also been sentenced to death posthumously .

An estimated 793,000 people worldwide committed suicide in 2016, around 10,000 of them in Germany. Worldwide, 10.5 people per 100,000 people committed suicide, in Germany the rate was 13.6 suicides per 100,000 for men and 4.8 suicides per 100,000 for women. The global ratio of men to women is around 1.8; in Germany around 70 percent of suicides are male. About 79 percent of all suicides worldwide are committed in low- or middle-income countries. Suicide was the second leading cause of death among 15 to 29 year olds in 2016. The most common methods used are pesticides and weapons , and hanging is often chosen. Suicide can be committed actively and passively, for example by not using medication.

An act of suicide that does not result in death is called a suicide attempt . Attempts are estimated to be 10 times more common than completed suicides. Previous suicide attempts are the greatest risk factor for accomplished suicides.

From the perspective of clinical psychology and psychiatry , suicidal acts are often a symptom of a mental disorder . Suicidal acts can be prevented with psychotherapeutic or psychiatric treatment and various preventive measures. In addition to this consideration, there is also, for example, the controversially discussed concept of assisted suicide and the controversial term of accounting suicide . Basically, the World Health Organization (WHO) assumes that acts of suicide and suicidality are stigmatizing and subject to a general taboo . The World Health Organization also criticizes the fundamental underestimation of the subject of suicide. As of 2018, suicide prevention was only a priority in health policy in "few countries" , and only 38 countries had a prevention strategy at all.

As an independent science that deals with suicide especially from a psychiatric-medical point of view, suicide emerged in the 20th century .

designation

Suicide was assessed differently in societies and epochs, which is also expressed in language. Suicide is well established in the professional world . Like the neo-Latin word suicidium, which was used until the 20th century, the word is a modern neologism . Historically, tentamen suicidii was used for attempting suicide.

The term suicide is used colloquially , although this term is not used by many media and is rejected by many experts. This is based on the fact that this term implies a valuation and the legal definition of murder is not fulfilled. In addition, suicide is a complex phenomenon that can affect third parties as well as suicides. After a 2004 by Peter Helmich in German Medical Journal published articles the judgmental terminology complicates the mourning of the bereaved. According to Barbara Schneider, deputy chairwoman of the German Society for Suicide Prevention , the taboo “self-killing”, which is reinforced by the use of the term suicide , makes prevention work more difficult.

“The unfortunate, depressed or delusionally disturbed are due respect, understanding, compassion and therapeutic efforts; their relatives need and deserve compassion [...]. No word is more inappropriate than "suicide" for such a fate. "

The Latin root caedere can be translated differently depending on the context, for example with “to kill” and “morden”, but also with “to fall”. According to Helmich, this underlines the different possibilities of classification. Nevertheless, the colloquial term is still common, along with various euphemistic formulations. The latter are for example “take your own life” or “put your hand to yourself” (instead of suiciding , committing suicide or killing yourself ) and represent a way of distancing yourself .

The term suicide is used officially . The difference between intent and negligence remains open.

Suicide

Suicide is the historically oldest German-language term for a suicide. The originally non- judgmental term is not actually a German word creation, but arose as a loan translation of the neo-Latin suicidium in the 17th century. The word suicide appeared in the 16th century, for the first time with Martin Luther as "sein selbs körder" (his own murderer).

The Indo-European root of the word murder means "to be rubbed up, to grind" (cf. from the same root of the language friable and pain ). The word originally meant "death" (cf. the related Latin word mors for "death"). But already in old Germanic times the meaning of the word had shifted in many tribes and stood for "deliberate, secret killing".

In 1652 John Donne established the terms self murder for reprehensible suicide and self-homicide for suicide that was not reprehensible from the outset in the English language.

In his dictionary of philosophy (1923), Fritz Mauthner pleaded for the term suicide to be replaced by suicide : “[I am] inclined to use the new, less than perfect expression of suicide - not yet booked in DW - the old and the language words reminding of criminal law are preferable to suicide . [...] Jean Paul dared to transform himself into suicide ; the idea is always linked to that of crime , as it was called homicie de soi-même in French until after the middle of the 18th century . Suicide reminds me, like the outside staircase, sanctuary, of something that leads into the open, that allows freedom. "

In the sciences concerned with the phenomenon , the term suicide is mostly rejected today, as it is seen as an assessment of the act which, according to the general opinion, should be avoided. Fred Dubitscher said suicide was "not a murder in the strict sense and not a crime". Adrian Holderegger put it: "This residue of a religious prejudice and an outdated legal conception no longer has any place in a modern assessment scheme".

suicide

The term suicide assumes that a person kills himself in full consciousness of his mind and self-determined . According to the German Society for Suicide Prevention , however, this is not the case. Suicide attempt survivors reported that "they did not feel free to make decisions at the time."

The term was formed at the beginning of the 20th century from Friedrich Nietzsche's On Free Death , a chapter in his work Also sprach Zarathustra . According to Nietzsche, those who intend a free death should choose a “noble” death “at the right time”: “In your death your spirit and your virtue should still glow, like an evening red around the earth: or else dying has turned out badly for you. "

An example of suicide on the basis of philosophical considerations can be seen in the death of Socrates , who refused to flee, accepted the judicial judgment with respect for the law and discussed philosophical issues with his friends until the end. Even Seneca , who was already gravely ill, took after the failed attack on Emperor Nero his death sentence in the spirit of Stoicism as morally indifferent thing ( adiaphora ) and has studied both oral and written at length with his friends with death and suicide. He criticized those philosophers who declared suicide to be a sin.

The philosopher Wilhelm Kamlah spoke of a decision to commit suicide after careful consideration and out of inner peace and freedom and described it as a fundamental right . The philosopher Ludger Lütkehaus also pleaded for the "freedom to death" to be respected.

From a psychiatric point of view, it is a form of rational coping with suicidal tendencies, such as that undertaken by the severely traumatized writer Jean Améry in 1978.

The Duden describes the term as a cover word .

Assisted suicide and homicide on demand

If the suicide is carried out with the assistance of another person, it is called over the infringement depending on either the "assisted suicide" or in the legal language of " killing on demand " or " assisted suicide ". Such forms of euthanasia are internationally controversial and legally regulated differently. In geriatrics and geriatric care , passive euthanasia is repeatedly discussed in connection with the terms “ artificial nutrition ” or “food refusal”.

causes

Today's findings

The most common cause of a suicide or suicide attempt is seen today in diagnosable mental illness. Depending on the estimate, 90% of all suicides in Western societies are attributed to this. Since the diagnosis is often only made as a suspected diagnosis after a successful suicide, this classification is at least questionable, as only the suicide act itself and the descriptions of relatives can be used for the diagnosis. The latter may be incomplete or incorrect, or individual incidents may be given inappropriate importance afterwards ( recall bias ). Other studies only look at patients with a known psychiatric illness and also show a high proportion of the mentally ill in suicides; this tends to be underestimated here because many psychiatric illnesses are not diagnosed. Accordingly, suicide occurs more frequently in depression and manic-depressive illnesses .

Medicines can also cause suicidal thoughts. Usually the basis of the undesired drug effect is the increase or triggering of a depression or psychosis. This side effect has been statistically demonstrated in Phosphordiesterasehemmern , quinolones , 5-alpha reductase inhibitors , bupropion and SSRI .

Addictions , personality disorders and chronic pain also play an important role, but they also have smooth transitions to depression. Factors that trigger suicide can then be life crises such as separation from the partner, fear of failure or economic ruin - but this only occurs in about 5 to 10% of cases as the sole background to suicide. Nevertheless, it can be assumed that there is both an internal and an external cause of depression, that is, a patient who is susceptible to depression becomes depressed as a result of his or her circumstances.

Studies by the Psychiatric University Clinic in Zurich show that actual as well as threatened job loss is the trigger in around 20% of all suicides. For the years 2000 to 2011, based on WHO data, 233,000 suicides in 63 countries were examined. 45,000 of them were directly or indirectly related to a job loss. In addition, the increase in the suicide rate generally precedes a higher unemployment rate by around half a year.

A Swedish study shows that the risk of suicide is increased for adults who were not physically fit as adolescents. The risk of suicide is particularly high when, in addition to a lack of physical fitness, there is also a cognitive impairment.

Sometimes suicide is seen as a person's last resort from a life that is determined by physical pain and suffering that cannot be alleviated by the means of medicine. The triggering factors also depend on the culture. For example, the so-called loss of face is known as a motive for suicide in Asia.

Historical interpretations

The sociologist Émile Durkheim analyzed the social context of suicide on an empirical basis with his work on suicide (Le suicide) in 1897 . He distinguishes between the selfish , the altruistic , the anomic and fatalistic suicide.

Sigmund Freud's postulate of a death instinct in his work Jenseits des Lustprinzips (1920) has at best something to do with suicide on the edge. Rather, Freud understands the “death instinct” quite generally as a destructive aspect of life that can also be found in single-cell organisms and animals. The concept of the death instinct, which Freud himself referred to as “speculation”, was controversial from the outset even among adherents of psychoanalysis .

In his dictionary of philosophy (1923), Fritz Mauthner compared the suicide to a cat standing on the sea wall, which, because it is surrounded by hot iron bars, leaps into the deadly water. Like the cat, which would otherwise have suffered severe burns, we only kill ourselves if we consider survival to be more undesirable than death. Only then does the possibility arise that conscious motives become stronger than the instinct for self-preservation .

In 1927 Hans Rost compiled thousands of texts of all kinds on various aspects of suicide in a bibliography. The “Suizid-Bibliothek” from Rost's estate is now in the Augsburg State and City Library , and large parts of it are also available in microform (see literature).

Alfred Hoche (1865–1943) coined the term " balance sheet suicide " for suicide after a rational consideration of living conditions. Balance sheet suicides in the sense of a rationally calculated decision correspond to a subjective feeling. Viktor Frankl therefore spoke out in favor of using the term “accounting suicide” exclusively for the perspective of the person concerned.

Suicide prevention

Often a suicide is announced in advance. In addition, there are some signs that can precede suicide. Erwin Ringel introduced the term presuicidal syndrome for three such symptoms (narrowing of thought, inhibition of aggression or reversal of aggression and suicide fantasies) .

Psychologists take the position that such announcements and warning signs should be taken seriously and that the person concerned should be openly addressed if they suspect suicidality . They argue that people who want to die by suicide tend to find no one to talk to about these thoughts. A central point of prophylaxis is therefore to help people to talk about their problems and suicidal thoughts (“ suicide pact ”) so that they do not become even more isolated . Out of this thought, telephone counseling emerged in the 1950s as an institution for suicide prevention.

The “Nuremberg Alliance Against Depression”, headed by the psychiatrist Ulrich Hegerl, examined from 2001 to 2002 whether an education and training campaign about depression could prevent suicide and attempted suicide. General practitioners were trained on four complementary intervention levels, a professional PR campaign was designed, multipliers such as teachers, journalists, pastors and nursing staff were addressed and trained, and support measures and information materials were offered for those affected and their relatives. After two years of intervention (2001 and 2002) the total number of suicides and suicide attempts decreased significantly by 24% compared to the control year 2000 and the control region Würzburg. No statistically significant evidence was possible for suicides alone, as the region investigated, and thus the number of suicides, was too small and the random annual fluctuations too strong.

The Austrian psychiatrist Erwin Ringel investigated methods of preventing suicide and founded the world's first center for suicide prevention in Vienna in 1948. In addition, he initiated the founding of the International Association for Suicide Prevention (IASP) in 1960 and became its first chairman. Gernot Sonneck continues suicide research in Austria and, together with his colleagues, founded the Wiener Werkstätte for Suicide Research in 2007 .

The German Society for Suicide Prevention (DGS) offers background information on the entire topic of suicide: prevention, research, practical advice, literature, help facilities and the like. In December 2002 this society founded an initiative group National Suicide Prevention Program for Germany. Over 70 organizations and almost 200 experts work on this. She sees suicide prevention not only as a health policy, but also as a social task. In mid-August 2011, Gerd Storchmann from the Berlin association NEUhland for young people at risk of suicide, after the joint suicide of three girls near Cloppenburg , spoke out against “fundamentally condemning” Internet forums on suicide through which the three might have met; these do not always have to have negative effects.

Understandable as suicide prevention (of course leading to stress for fellow human beings, for example through rail suicide or falling into the depths)

- the lack of advisory literature with factual information about painless and considerate methods of suicide and

- the obstruction of assisted suicide by professional and legal regulations.

In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) proclaimed September 10th as World Suicide Prevention Day for the first time . This annual day of action is intended to raise public awareness of this taboo subject, as the WHO believes that suicides are one of the greatest health problems of our time.

As a preventive measure, some buildings with high viewing terraces are equipped with unclimbed grids or textile nets. In June 2014 it was decided to equip the Golden Gate Bridge , a structure with a particularly high number of suicide jumps, with a horizontal net that catches those who fall. At the Empire State Building , the railing is raised to the ceiling with a grille: the lower area with a grille with diagonally crossed struts, above vertical struts.

In a guideline published for the first time in 1997 , the German Press Council recommends restraint in reporting on suicides (see Werther Effect: Reaction of the media ) in order to avoid acts of imitation (see Werther Effect ).

Suicide prevention in adolescents

A study published in 2014 with more than 44,000 adolescents in Germany identified a total of nine factors that are significantly related to suicide attempts in adolescents. Eight factors were found that were associated with a higher risk of suicide attempts in adolescents:

- female gender

- a doctor-made ADHD diagnosis

- currently a smoker to be

- have binge drinking in the past four weeks

- School refusal

- Migration background

- parental separation experiences, such as B. Divorce as well

- a neglectful parenting style in childhood.

The only protective factor Donath and colleagues could find was an authoritative parenting style in childhood. This later lowered the risk that young people would seriously try to kill themselves. The researchers conclude from these findings that the style of upbringing is essential and that one could develop very early prevention approaches that include the features and implementation of the authoritative style of upbringing in everyday life. It is also suggested that existing and accepted prevention programs for adolescents who are e.g. B. aim at substance consumption (see drug prevention ), to expand in terms of suicide prevention.

statistics

Worldwide

According to the World Suicide Report by the World Health Organization (WHO), around 804,000 people worldwide committed suicide in 2012. This equates to 11.4 per 100,000 people. In 2012, suicide was the second leading cause of death for 15 to 29 year olds after traffic accidents.

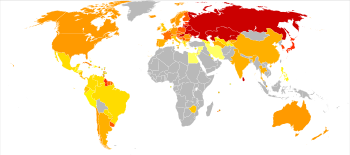

An overview of the suicide rates worldwide in comparison can be found in the list of suicide rates by country . A global average cannot be determined due to inadequate data. Within the OECD , the suicide rate (suicides per 100,000 inhabitants / year) fluctuated between 11 and 16 between 1960 and 2005. Since a peak of 16.0 in 1984, the suicide rate has steadily decreased and stood at 11.4 in 2005. In the European Union , according to a report by the EU Commission from 2005, 58,000 people died each year as a result of suicide, most of these cases involving people suffering from depression. In terms of other causes of death , the same report lists 50,700 road deaths and 5,350 victims of violent crimes annually.

The suicide rate is strongly dependent on gender; the rate is consistently higher in men than in women. In affluent countries the proportion of men is around 75%, in poorer countries around 60%. Bangladesh and China are the only countries where the proportion of women exceeds that of men.

The highest suicide rate worldwide is reported from Sri Lanka , with 35.3 in 2015 (men 58.7; women 13.6), the highest suicide rate among women from South Korea with 16.4 in 2015 (men 40.4; average 28.3). The highest suicide rate in Europe was recorded in Lithuania , with 32.7 in 2015 (men 58.0, women 11.2). The lowest suicide rates in Europe were measured in Greece , with 4.3 in 2015 (men 7.1, women 1.7) and in Albania , also with 4.3 in 2015 (men 5.9, women 2.7 ).

The suicide rate is also age-dependent, but this dependency varies widely from one culture to another. It is highest worldwide for people aged 70 and over. In South Korea , the suicide rate rises steadily with age, but decreases in Norway and New Zealand , while in countries with a low suicide rate such as Portugal, Greece or Italy it is hardly dependent on age.

Germany

Overall frequency

The number of suicides in Germany (the former Federal Republic of Germany and the new federal states including East Berlin ) followed a falling trend from around 1980 to 2007, after which it rose slightly and fell again after 2014. A high number of unreported cases can generally be assumed in the case of suicides. In 2017, 9,235 people died as a result of suicide in Germany (2016: 9,838 or 11.29 per 100,000 inhabitants). In 1980, 18,451 people (23.6 per 100,000 inhabitants) had died as a result of suicide. In West Germany (excluding the GDR ) there were a total of 12,868 suicides in 1980 (8,332 men, 4,536 women), with 61.66 million inhabitants that is 20.87 per 100,000 inhabitants. For the GDR, the above figures result in 5,583 suicides in 1980. With 16.74 million inhabitants, that's 33.35 per 100,000 inhabitants.

Improved specialist medical care, the removal of taboos on mental illnesses and problems with methodological recording are seen as reasons for the sharp decline in the meantime. In the meantime, the category of the “unclear cause of death” has been introduced, and there is also likely to be a high number of suicides among the alleged drug deaths . Approximately 1,000 drug deaths are assumed for 2011, not including those who died from alcohol abuse (> 70,000) and as a result of tobacco smoking (> 110,000). It is therefore assumed that a realistic estimate of the actual number of suicides is 25% above the statistically recorded number. In 2007, suicides accounted for 1.1% of all deaths and 30.7% of deaths with an external cause (comparison: accidents 60.4%, including falls 25.2%, traffic 16.9%). The increase in the suicide rate of almost 9% since 2007 corresponds to the recent sharp rise in the burden of illness due to mental disorders, especially depression, and affects men more than women.

Experts suspected that the sudden significant increase in the number of suicides in 2009 was due to a connection between media coverage of the suicide of soccer goalkeeper Robert Enke and the number of copycats. In 2009, 9,571 suicides were committed. As early as the publication of Goethe's novel The Sorrows of Young Werther , there had been a wave of suicides in 1774, with numerous deaths clearly recognizable as imitations of the novel. In the scientific literature, copycat suicides are therefore referred to as the “ Werther effect ”. In the meantime, numerous studies (such as two increases after the first broadcast and repetition of the film Death of a Schoolboy ) have confirmed a connection between media coverage of suicides and an increase in crimes. That is why the German Press Council urges the media to exercise restraint when reporting on suicides in its code. From today's perspective, however, the interpretation of the sudden increase in the number of suicides in 2009 as an “outlier” is put into perspective by the equally strong increase in 2010 and the further increase in 2011 as well.

Frequencies

Age and gender

The death rate from suicide is very dependent on age and gender. In 2007 children were affected with a mortality rate of less than 0.3 per 100,000 inhabitants. In the 15- to 19-year-old group, the mortality rate was 2.1 (female) and 6.2 (male) per 100,000 population and rose to 17.9 and 68.7 per 100,000 for 85-year-olds and older, respectively Residents. The proportion of suicides in the causes of death nevertheless reaches its maximum in young adults, since their mortality rate from illness is very low. In the 15- to 35-year-old age group, suicide was the cause of one in six deaths (16.5%). Overall, the suicide mortality rate for females was 5.7 and for males 17.4 per 100,000 inhabitants. Of the 9,402 suicides, 7009 (74.5%) were carried out by men. Because the number of suicides in women is falling faster, this proportion has an increasing tendency.

There are significant regional differences within Germany. In 2006, the highest number of suicides occurred in Bavaria (13.3 per 100,000 inhabitants), the lowest in Saxony-Anhalt (6.6 per 100,000 inhabitants). In 1990, most cases were counted in Saxony (28.3 per 100,000 inhabitants) and the fewest in North Rhine-Westphalia (11.9 per 100,000 inhabitants). In 1982 the frequency of suicide in the then Federal Republic of Germany was 24.7 per 100,000 inhabitants, in the GDR it was 35. However, researchers attribute this less to the social order, since the territory of the GDR mainly comprised areas such as Saxony and Thuringia, which already showed increased suicide rates in the German Reich . In the period that followed, however, this frequency decreased and is now 20 for men and 7 for women. Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia are currently still among the federal states with the most suicides.

Other factors

The number of suicides is also subject to seasonal fluctuations. In 2006, more people took their own lives during the spring and summer months than during the autumn and winter months. From March to July the proportion of suicides in the year was higher than the proportion in the month of the year, particularly in May and July, while from August to February the proportion of suicides was evenly below the annual proportions.

The suicide rate of doctors is up to 3.4 times higher than that of other citizens, the rate for women doctors is up to 5.7 times higher. In addition to the occupational long-term preoccupation with stressful issues such as illness and death, one possible explanation for this high rate is that doctors have both the expertise and access to means to commit suicide that other population groups have less often.

In prisons , suicide is the leading cause of death. The percentage of the social group also clearly exceeds that of other groups. In 1987 there were reports of a rate ten times higher. In the same year the Federal Constitutional Court did not accept the constitutional complaint of the prisoner Günther Adler , who wanted to sue the state for help in suicide because of the "hopelessness" of his life, which he himself assumed.

Suicide attempts

The number of suicide attempts is estimated to be a factor 10 higher than the number of completed suicides, i.e. around 100,000. Here too, high numbers of unreported cases are to be expected. The influence of age and gender is exactly the opposite of that of completed suicides. The frequency of suicide attempts is highest in young women and lowest in older men. Sample estimates for Germany determined 131 for women and 108 for men per 100,000 inhabitants for 2001. For 15 to 24 year old women, up to 300 attempts per 100,000 population are estimated. Overall, soft methods of poisoning dominate in suicide attempts (78% female, 59% male) followed by the use of cutting or stabbing objects (14% female, 23% male). The intention of suicide attempts correlates significantly with age: In younger people, parasuicidal gestures and breaks dominate, in older people there are more likely to be suicide attempts in the narrower sense, i.e. with the intention of suicide .

Methods

Of 10,209 recorded suicides in the Federal Republic of Germany in 2014, the following causes of death were recorded:

- Hanging / Choking 4,863 (48%)

- Fall 983 (10%)

- Medication poisoning 800 (8%)

- Throwing yourself in front of the train or cars ( rail suicide , street suicide ) 653 (6%)

- Gas poisoning (mostly carbon monoxide ) 471 (5%)

- Shoot them (mostly headshot ) 464 (5%)

In 2006, men resorted to the so-called “hard” suicide methods of hanging, strangling or suffocating in 52.6% of cases and thus more often than women (34.5%), who in turn more often used “soft” methods such as poisoning with an overdose of medication etc. applied.

In 2008, 714 people killed themselves on German railway lines, in 2009 it was 875, according to a report by the Federal Railway Authority .

Austria

In the interwar period from 1919 to 1939 there were between 30 and 40 suicides per 100,000 inhabitants per year in Austria. No data are available for the years 1940 to 1945. In 1945, an exceptionally high suicide rate was recorded with 60 suicides per 100,000 inhabitants (4,500 in absolute terms).

The suicide rates after 1945 fluctuated between 20 and 30 suicides per 100,000 inhabitants, with an absolute value of 1500 to over 2000 suicides per year. Based on these figures, Austria is considered to be a country with a medium (10–20) to high (over 20) suicide rate in an international comparison. Between 1945 and 1986 there was a significant increase in the rate from 20 to 28 suicides per 100,000 inhabitants. Thereafter the number declined and in 1999 fell to around 19 suicides per 100,000 inhabitants. Suicide rates are developing very differently from region to region, while they have been falling in Vienna since 1986, for example, and have been increasing in Tyrol and Upper Austria since 1991.

The suicide rate of men in Austria is twice as high as that of women and increases with age. While male adolescents up to the age of 15 have a suicide rate of 2, girls of the same age have a suicide rate of 1. At the age of 85, however, the suicide rate for men is 120, compared with only 33 for women. As in Germany, the suicide rate for men over 85 is particularly high high, their rate is 140% higher than that of 60 to 64 year olds.

There is a high suicide rate among prison inmates , who, however, are predominantly male and tend to be older. One source cites 20 suicides per 8,800 prisoners, a rate of 227 / 100,000. The letter bomb bomber Franz Fuchs attempted a suicide by pipe bomb when he was arrested in 1997, broke both hands and hanged himself in solitary confinement in 2000. The killer Jack Unterweger was paroled early in 1990, convicted of 9 more murders in 1994 and hanged himself in the cell the following night.

For the detention cell of the Hörsching barracks in the guard building at the main entrance, the regulation to leave the shoelaces outside the cell was strictly enforced around 1985, probably to thwart strangulation. However, a small backpack with one inch wide shoulder straps was tolerated in the cell.

In the police detention center (PAZ, formerly police prison) in Graz, lace-up shoes are generally tolerated, but a backpack in the cell is taboo (2000 and 2019). Cigarettes, lighters and smoking are allowed in the cells. Sometimes there is a fire as a result of an accident or a fire, prisoners can then not escape from a mostly locked cell, not all cells have smoke detectors, and the guard often does not react for minutes to ringing the doorbell or intercom. In the PAZ Bludenz - 3 hours after his nightly admission, after an alarm from the fire alarm - a 28-year-old Austrian, who was supposed to serve a 14-day administrative sentence, was pulled out of his burning cell on April 7, 2017, he died after 8 weeks Coma and could not be questioned. The police assume arson. In 2015, a Spaniard (28) died in the PAZ Villach in his cell, which was smoked with smoke at 6 a.m. Here, too, the cause remains unclear.

The number of suicide attempts can only be estimated because of the difficulty in collecting data. Projections have shown a number of around 25,000 to 30,000 suicide attempts per year. These are mainly poisonings (especially with alcohol) and drug overdoses.

The most common method of suicide among men and women in Austria is hanging. Around 40% of suicides by women are caused by hanging, 25% by poisoning and 14% by falling from a height . In the case of men, almost 50% of the suicides hang themselves, around 20% shoot themselves and around 10% poison themselves.

Switzerland

In 2014, just over 1,000 people died as a result of suicide in Switzerland (around 750 men and 275 women). This corresponds to an annual suicide rate of 20 per 100,000 men and 7 per 100,000 women. 1,043 people committed suicide in 2017; a further 1,009 people have committed assisted suicide .

The suicides that occurred between 1969 and 2000 were carried out in the following ways:

- Hanging 25%

- Firearms 24%

- Poisoning by solid or liquid substances 14%

- Crash 10%

- Drowning 9%

- Rail suicide 7%

- Gas poisoning 6%

- Cutting, piercing 2%

France

In France , the suicide rate is significantly higher than in Germany (see list of suicide rates by country ). In about 2006 it was 18 per 100,000; in Germany less than 12 per 100,000. According to the French UNPS (Union Nationale pour la Prevention du Suicide) , over 10,000 people have been killing themselves each year in France for many years; Alcohol consumption during life crises lowers many people's inhibition threshold to commit suicide.

Manifestations

Suicide of old age

Suicidality increases with age in Europe. The age limit for this increase is sometimes given as the age of sixty. Some of the seniors suffer (actually or supposedly) from a serious illness; they lead to self-abandonment - suicides. These can take place in a way that a person consciously reduces or completely stops his food and / or fluid intake. For relatives and caregivers, this often creates an ethical conflict situation between respect for freedom of choice and the fear that death through thirst or hunger could occur involuntarily.

Depression (illness) as a cause of suicidal ideation can be treated at any age, including the very old, with roughly the same good chances of success ( prognosis ). On the other hand, there is the opinion that depressed people also have free will and can decide; It is therefore to be granted to them that, like other sick people, they refuse therapeutic interventions or therapeutic interventions that reduce suffering.

Assisted suicide

The German Society for Human Dying assumes that there are numerous patient suicides in Germany . In part, she sees it as one of her tasks to provide individual and social support for this. There are different ethical judgments.

Other so-called suicide aid organizations have been founded in Germany since 2000. As a result, a law was passed in Germany on December 3, 2015 ( Federal Law Gazette I, p. 2177 ), which criminalizes the commercial promotion of suicide by the newly drafted Section 217 of the Criminal Code (StGB).

Double suicide

General example: A couple sit down in a car and, with the engine running, lead the exhaust gases through a hose into the interior of the car. Each of the two has the opportunity to break off the suicide by opening the car door on his side until his senses disappear, but renounces this ( decided by the BGH , whereby the survivor who stepped on the accelerator was due to a killing on request according to § 216 StGB on his girlfriend).

With internet suicide , two people agree to commit suicide together over the internet .

Concrete examples

- Stefan Zweig and his wife Charlotte died in exile in Brazil in 1942 as a result of double suicide using medication. Charlotte Zweig waited for her husband to die before overdosing on herself.

- Adolf Hitler and his wife Eva killed each other on the afternoon of April 30, 1945 in the Führerbunker of the New Reich Chancellery . Both poisoned themselves with potassium cyanide , and Adolf Hitler shot himself in the temple.

Examples of suicide and homicide on demand

- Heinrich von Kleist killed Henriette Vogel on November 21, 1811 at the Kleiner Wannsee near Berlin at her request, and then himself. But since Kleist killed his spiritual friend who was willing to die and suffered from uterine cancer, it would not be a “double suicide” today. It would be a killing by Kleist at Henriette Vogel's request.

- On the night of January 30, 1889, the Austro-Hungarian heir to the throne, Crown Prince Rudolf , and his lover Mary Vetsera died at Mayerling Castle . The details of the circumstances have not yet been clarified, as the Viennese court destroyed key documents and obliged contemporary witnesses to remain silent for life. According to the current state of research, the depressed 30-year-old Rudolf first shot the 17-year-old Baroness Vetsera before killing himself with a head shot.

- In 1911, Hans Fallada and his friend Hanns Dietrich von Necker agreed to commit suicide together in Rudolstadt . The friends disguised the project as a "duel". Von Necker died, Fallada survived seriously injured, was prosecuted and given medical treatment, remained mentally unstable and drug addict until the end of his life in 1947 . If the project had been implemented as planned, this would not have been a “double suicide”, but would have been criminally assessed as a mutually committed killing on request.

- Johannes R. Becher tried in Munich in 1910 to kill himself and his lover, who was seven years his senior, by shooting first at her and then at himself, as agreed. While the woman died, Becher survived. The act was obviously inspired by Kleist's example, to whom Becher dedicated his first published literary work, the “Kleist hymn” Der Ringende . Becher was charged with homicide on demand, but escaped conviction at the instigation of his father, a judge at the Munich Higher Regional Court, by being declared insane . In the years that followed, Becher repeatedly had to undergo clinical treatment for addictions and made several suicide attempts.

- Steglitz school tragedy in 1927 in Berlin-Steglitz: The agreed-upon killing and suicide because of complicated relationship problems with four young people involved. Two people died, one did not carry out the promised deed, survived, later emerged as a writer and scientist under the new name Ernst Erich Noth and lived until 1983.

Mass suicide

Extended suicide

In rarer cases, suicide is accompanied by the killing of third parties (mostly partners and children), in advance or in unity , with intent or with contingent intent . In these cases one often speaks of an extended suicide . Even if the other people killed were not asked for their consent, the language rule of extended suicide applies .

The terms entrainment suicide and homicide-suicide ( "Homozid-suicide") and murder-suicide are used synonymously. A take-home suicide is only present if the goal of harming oneself is greater than the goal of causing harm to others.

The rampage with subsequent suicide is a special case of extended suicide in which people who are not known to the perpetrator are often victims.

The term “ extended suicide” was made unword of the year in Switzerland in 2006 . There was also astonishment and a discussion about this term in reports and comments on the Germanwings crash in the Alps in 2015. The term pilot suicide was coined for such events .

Suicide as a protest action and political means

With suicides carried out in public, attempts are often made to serve a “higher concern” in a political, moral and ethical sense and to attract appropriate public attention. Spectacular examples of this are:

- During Kurdish protests in Germany on March 19, 1994 in Mannheim, the two women Nilgün Yildirim ("Berîvan") and Bedriye Tas ("Ronahî") set themselves on fire in protest against the bans on Newroz celebrations in the Federal Republic and the FRG's participation in the war Kurdistan , yourself. Both died from their burns.

- During the Vietnam War , many clergymen and monks burned themselves to death in public places by dousing themselves with gasoline and setting fire to themselves in front of the camera. These protest suicides soon stopped because they could not influence the course of the war.

- Jan Palach's self-immolation in Prague on January 16, 1969, of the consequences of which he died three days later, touched the protest against the crackdown on the Prague Spring and caused an international stir.

- In the former GDR, the evangelical pastor Oskar Brüsewitz wanted to point out the hostility of the SED regime to the church on August 18, 1976 in front of the Michaeliskirche in Zeitz ("Fanal von Zeitz").

- The self-immolation of Hartmut Gründler on November 16, 1977 in front of the St. Petri Church in Hamburg during an SPD party congress was directed against the energy and nuclear policy of the federal government at that time. Gründler was a doctoral student in Tübingen and a follower of the teachings of Gandhi .

- Since April 1998, 118 Tibetans and 22 Tibetan women set themselves on fire in protest against Chinese politics and the oppression of Tibet. 117 of them died.

- In December 2010, news of the self-immolation of the greengrocer Mohamed Bouazizi on December 17, 2010 in Sidi Bouzid , a city 250 kilometers south of the capital Tunis, quickly spread in Tunisia . The unrest quickly turned into a revolution .

- Since the austerity and increasing crisis in Greece , the number of suicides has risen sharply. The suicide of the former pharmacist Dimitris Christoulas on April 4, 2012 on Syntagma Square in Athens became particularly well known. Christoulas had participated in protests and wrote in a suicide note that a dignified life in retirement would no longer be possible in the future.

Since the 1980s, the number of so-called suicide bombings in conflicts in the Islamic cultural sphere has risen sharply. The emergence of suicide attacks during this period is seen by some as a military strategy. It has also occurred in Sri Lanka. For more specific information, see below

Hunger strikes sometimes lead to the death of those who carried out them. As a result of a politically motivated hunger strike, for example, the Northern Irish IRA activist Bobby Sands died in 1981 (cf. Irish Hunger Strike of 1981 ) and the German RAF member Holger Meins in 1974. Both tried to refuse to eat in different contexts in detention to enforce political prisoner status and improvements in prison conditions.

Suicide as a Military Tactic

As early as 500 BC, the Chinese general Sunzi mentioned The military tactic of the suicide attack, to which one should not drive an opponent. Suicide is also a way of evading jurisdiction or arrest by political or military enemies while shocking and impressing the opponent. The mass suicide on the fortress Masada became known by Jewish zealots under Eleazar ben Ja'ir in the year 73 AD.

The deeds of Arnold Winkelried and Carl Klinke are more or less legendary .

In the Second World War , especially in its final phase, young Japanese pilots from the Shimpū Tokkōtai special unit flew attacks on American ships with their fighter planes, which was known as the "kamikaze tactic". National Socialist Germany adopted this tactic at the end of the Second World War, so that such operations were also ordered and flown on the German side.

In civil wars, wars and uprisings, suicide bombers have recently become more active , for example in Iraq.

The suicide bombers who hijacked several civilian planes on September 11, 2001 and drove two of them into the two towers of the World Trade Center and one into the Pentagon , became particularly well known .

Suicide in world views

The question of the moral permissibility of suicide is culturally considered very different. There is often an ambivalent relationship in the different societies. In many societies, a mostly differently defined “honorable suicide” has been and is widely accepted as the only permissible type of suicide. This included the Japanese seppuku , which was about restoring a lost honor . This occurs with a similar goal in Europe, with the military and politicians (not infrequently through self-shooting), but also with business people in bankruptcy . In 1900, the publication of Arthur Schnitzler's Lieutenant Gustl sparked a scandal. The protagonist of the novella is happy not to have to kill himself out of honor, since his unequal opponent has suddenly died. The Austrian officers' society degraded the nest-polluting author.

Antiquity

The moral valuation of suicide was already very controversial in ancient times. In tragedy and epic , suicides were widely revered as heroes. The Greek philosopher Hegesias (3rd century BC), who was nicknamed Peisithanatos (“the persuader to death”), emphasized the misery of human existence in his lectures, fed by his pessimistic view of life . He attributed the right to commit suicide to individuals. Human life in itself has no particular moral value. His remarks turned out to be so convincing that his lectures were banned in Egypt because many listeners took their own lives.

Leading Greek philosophers such as Pythagoras and Plato (see Phaidon), later also Romans such as Cicero ( Somnium Scipionis ), on the other hand, rejected suicide for religious and religious-ethical reasons. Many stoics of the middle Roman school such as Cato the Younger and Seneca , on the other hand, saw suicide as an option in certain cases. For Marcus Aurelius (around 170 AD) life and death as such were irrelevant. What was important to him was a rational lifestyle characterized by charity. He saw his empire - at least in his public self-portrayal - as an order to fulfill his duty "like a soldier storming the enemy wall". So giving up was not part of Marcus Aurelius' concept of life; but death as a necessity - for example, during the fulfillment of duty - does. This coincided with the traditional view of the Roman nobility , which had always propagated “Roman death”, that is, honorable suicide in certain situations.

The suicide, mainly practiced by Roman generals and made famous through literature and films, of throwing oneself at the sword in hopeless situations, was no longer unanimously regarded as an "honorable death", at least in the later imperial era, as it was usually carried out in completely hopeless situations in which members of the army either looked to a perhaps even more terrible end or wanted to prevent personal disgrace. The Greek historian Cassius Dio wrote around 220 looking back about the end of the commander-in-chief Publius Quinctilius Varus during the battle in the Teutoburg Forest (9 AD):

“Varus and the rest of the officers were gripped by the fear that they would either be captured alive or be killed by their fiercest enemies [...], and that made them dare a terrible but necessary act: They committed suicide. [...] As the news spread, not one of the rest of the people, even if they were strong enough, offered resistance, rather some imitated the example of their general, while others threw away their weapons themselves and tried the next best thing who wanted to be put down; because escape was impossible, no matter how badly one wanted to seize it. "

In the case of the emperor Nero , his attempted suicide - at least in the portrayal of the consistently hostile tradition - during his escape became a disgrace, since he needed the help of his last faithful with his dagger stab in the neck. Nero's death was not a suicide of the kind practiced in the military. The suicide of his short-term successor, Otho , who committed suicide in 69 after losing the civil war, is praised in the sources.

Judaism

In Judaism , YHWH as the creator of the world is the one who gives and takes life. Until the 20th century, suicides were denied all usual funeral rites. Like criminals, they had to be buried in separate places outside the cemeteries; a practice that the churches later adopted. Suicide was a criminal offense in Israel until 1966 and was therefore strongly taboo .

Today (depending on the Jewish orientation) the mental state of the suicide is seen as a mental illness and the actual suicide as a consequence of this illness. This makes it possible to carry out the funeral rites again.

But also in Judaism there was and is the possibility of enjoying the highest veneration through an “honorable suicide”. Rabbinic and later also Orthodox Judaism assessed all religiously inspired suicides as equivalent to martyrdom that occurred in the face of threatened agonizing death, immoral treatment or the compulsion to apostasy . This is also known as Kiddush HaSchem - sanctification of the name (God). Therefore, in today's state of Israel, the people on the Masada are highly honored who killed themselves before the last attack by the Romans.

Christianity

In late antiquity the church dealt with the philosophical doctrines. In many cases, the separation between philosophy and religion was not yet clear. Even the church father Augustine , despite all the criticism of Plato, allowed many fundamental Platonic ideas to flow into his views and thus into the Catholic tradition. In his best-known work De civitate Dei , Augustine called Plato as a witness for a ban on suicide. Augustine interpreted the biblical commandment You shall not kill in such a way that it can also be applied to the preservation of one's own life. Later the church took over the Jewish tradition and refused - analogous to Judaism - until the early 20th century to allow suicides to be buried in cemeteries. Instead, the body was buried in unconsecrated earth, see donkey burial .

An important argument of Catholicism against suicide is that life in itself belongs to God and so the gift of life is rejected. Closely related to this is the view that human life is sacred and unique and that every effort must be made to protect it. Cicero had already taken this point of view.

In the Codex Iuris Canonici (CIC) of 1917, deliberate suicide was a reason for exclusion from a church funeral . That was not true in the case of signs of repentance. In case of doubt, a church burial was to be granted. The CIC of 1983 no longer mentions suicide under the exclusion of a church burial (Can. 1184).

Islam

In Islam , suicide is strictly forbidden. According to some hadiths , people who kill themselves are refused admission to Paradise and are threatened with "eternal hellfire". At least it is considered a serious sin (Sura 4,29), because according to the Muslim view only God has the right to decide between life and death.

Nonetheless, people who viewed themselves as Muslims committed numerous suicide bombings . This happened and is happening partly as part of a struggle against “unbelievers” and partly within the framework of internal Islamic struggles of different faiths. In these cases the boundaries between suicide and witness of faith are fluid. Apparently, many assassins believe that they will be taken to paradise immediately after their death . Martyrdom was also politicized, especially through Shiite Islam.

Islamic martyrdom always requires the consent of religious leaders and a religious community; otherwise it would be viewed as suicide. In the Shiite tradition it was also stipulated that only unmarried men and not women were allowed to die as a martyr. In addition, the parents always had to agree. These traditions were softened in the early 1980s by Ayatollah Khomeini , who no longer considered parental consent necessary. The leading Shiite religious scholar in Lebanon, Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah (1935-2010) , also shared this opinion . He saw it as the duty of girls and boys to go to their deaths without the consent of their parents. The intra-Muslim disputes about who is a martyr and who is not, make Fadlallah's condemnation of al-Qaeda clear. Fadlallah is also the spiritual mentor of the radical Islamic terrorist organization Hezbollah , but he refuses to continue the Islamic struggle in the United States, as happened in the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in New York City. He condemns the attacks by al-Qaida as "not compatible with Sharia [...] and true Islamic jihad". For Fadlallah, the al-Qaida fighters are not martyrs, but “mere suicides”.

In Sunni Islam, too , suicide is viewed as a sin; nevertheless there is a tradition of suicide there. After Shiite scholars restricted or lifted the parental consent to the martyrdom of their children, the Sunni Abdalsalam Faraj , pioneer of the Egyptian jihad group, supported this stance in his book The Forgotten Duty (1981).

The comparatively low general suicide rate in Islamic countries may also be due to the idea of predestination of fate ( “kismet” ).

Buddhism

In the Buddhist scriptures, suicide is viewed in a differentiated manner. Buddhism itself vacillates between outright rejection and conditional consent to suicide. In no way does suicide compare to the killing of another being, and forms of suicide that endanger other lives are largely outlawed because of this fact. Suicide with the aim of protecting one's own enlightenment from relapse (e.g. in the event of a serious illness) or in order to ascend to a higher form of existence after rebirth is valued positively here and there in the scriptures. A prerequisite for a positive evaluation of suicide is a “clear, concentrated and calm state of mind” and “trust in a Buddha”. Under these conditions, suicide is said to be neither reprehensible nor karmically harmful.

One of the most famous texts in the Pali canon on the subject of suicide is the Channovāda Sutta :

“ Sāriputta and Mahācunda, his companions, visit the monk Channa, who is suicidal because of a serious illness . They inquire in detail about possible deficiencies in food, care or medical care. But Channa denies any deficiency. Then they inquire about possible deficiencies in enlightenment, but Channa explains in detail that he has achieved enlightenment. After the two monks have found no lack in Channa, they speak to him once more of the doctrine of the end of suffering and leave him. Channa takes the sword and kills herself. Then Sāriputta questioned the Buddha and presented the case to him:

'The venerable Channa, O Lord, took up the sword. Which is his path, which is his fate after death? '

Buddha points out that Channa has proven to be flawless in the thorough interrogation, that is, as one who has achieved arhatship and will not be reborn. Seen in this way, the Sāriputta's question is already wrong. Sāriputta, however, refers to the relatives and friends who regard the behavior of Channa as reprehensible, but Buddha rejects this:

“Who, oh Sāriputta, throws off this body and puts on another body, I call him reprehensible. This is not (the case) with Channa the monk; Channa, the monk, took up his sword without blame "."

So it seems here that someone who will not be born again may well die by suicide.

The commentary literature on this case strictly refuses to take this text as evidence that an arhat, in contrast to an unsaved, may kill himself. In the comments, the moment of attaining arhatship is moved to the moment of death to emphasize that the act of suicide was not the act of a redeemed, but the act of a person who stood before it. If he were already in a state of arhatship, Channa would be an ethical model for all Buddhists, and this should not be derived from it.

Any suicide that is associated with self-assertion is therefore in principle viewed as ethically reprehensible, since this is precisely the cause of the eternal rebirth samsara .

Since all life is respected in Buddhism, suicide is also outlawed in Buddhism today, insofar as a destructive motivation is the cause. In Thailand and Sri Lanka , which have been shaped by Theravada Buddhism, suicide is also considered a disgrace for the entire family.

Only in very rare cases can a suicide be rated positively, for example if it saves other people.

Hinduism

With the suppression of Buddhism by Hinduism in India from the 5th century onwards, suicide became widespread. The Puranas , which are one of the most important texts of the Hindus, emphasize that suicide is a reward for the ascetics to seal their piety, but not a way out for people who do not believe in the gods. In the spirit of these texts, pilgrims let the wheels of their processional floats roll over them during parades in honor of Jagannath ( Rath Yatra ); others seek holy places where one can jump to one's death from great heights, drown oneself or, especially in the case of Himalayan sanctuaries, freeze to death in the snow.

A type of suicide known from all over East Asia is widow burning . For a woman, in view of her rebirth, it was considered meritorious to jump into her husband's funeral fire. However, it also happened that relatives forced the death of the wife. Even after the colonial administration of British India banned widow burning in the 19th century, women repeatedly went into the fire. In contrast to some currents of Buddhism, the bereaved of a suicide in Hinduism are not blemish.

Jainism

Indian monks belonging to Jainism perform the death fast at the end of a long ritual practice path.

philosophy

Important representatives of the Enlightenment, such as the philosophers Immanuel Kant and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, deny the right of people to put an end to their own lives. In Kant there are Platonic influences on this. He, too, therefore uses the image that a person is not allowed to leave his guard post. This philosopher finds suicide fundamentally reprehensible: "Destroying the subject of morality in one's own person is just as much as eliminating as much morality itself, according to its very existence, from the world."

Kant's contemporary David Hume , on the other hand, is of the opinion that suicide is a right established in human society. To the Christian view that human life is sacred and unique and that every effort must be made to protect it, Hume replies that in this sense it must also be wrong for a Christian to postpone a natural death, since this is contrary to God's will.

Arthur Schopenhauer , whose philosophical system in his main work The World as Will and Idea leads to the “denial of the will to live” as an ethical goal, nevertheless rejected suicide because, according to him, it is by no means - like voluntary asceticism - a denial of the will to Express life, but rather represent "a phenomenon of strong affirmation of the will". For “the essence of the denial [of the will to live] is not that one detests the sufferings, but that one detests the pleasures of life. The suicide wants life and is simply dissatisfied with the conditions under which it became him. ”The philosopher Philipp Mainländer , who was heavily influenced by Schopenhauer , undertook an“ apology for suicide ” in his philosophy of redemption .

Albert Camus tackled the problem of suicide in his philosophical essay The Myth of Sisyphus . Although he declares suicide as the only way out of the absurdity of human life, he vehemently rejects it. According to Camus, the strength of modern people is not characterized by killing oneself, but on the contrary, recognizing the absurdity and still continuing with one's tasks, as he explains using the example of the “Myth of Sisyphus”.

Jurisprudence

In jurisprudence , there were isolated demands for the liberalization of suicide, the execution of which continued to be punished as a criminal offense in many areas of Europe until the beginning of the 19th century. The criminal law reformer and important thinker Cesare Beccaria made it clear in his remarks that suicide should not be punished "because it can only fall on a cold and lifeless corpse or on innocent people."

Other cultures

In other cultures, ritual suicide can be socially acceptable. The Japanese seppuku or the Indian sati should be mentioned here . Even among the Maya in their classical period, the goddess Ixtab was responsible for those warriors who, after losing their honor, are pulled by her with a rope into one of the thirteen heavens.

It is more difficult to assess the role of suicide among the Suruahà in the Amazon region. Cunahá, a poison that is used to kill fish and is extracted from certain liana roots, is consumed by tribe members from the age of 12 for spiritual and ritual purposes. This is fatal if the root is not spat out again quickly enough. On the other hand, there is no word for “suicide” among the Suruahá.

Eskimo culture:

With the Eskimos , until the adoption of Christianity , until about the move from the camps to settlements in the middle of the 20th century, it corresponded to old tradition, to ensure the survival of the tribe or a large family, sick or disabled children and elderly people who had become unfit for life ( leaving them behind or even killing them when hiking in the camp. According to Franz Boas , suicide among the Eskimos was not uncommon towards the end of the 19th century and generally happened by hanging. Violent death including suicide was preferred creeping death, the souls of violent deaths by as according to the ideas of the Eskimos Qudlivun, land of happiness (happy land) go. Although men had the right to kill their parents who had grown old, this was rarely done. Old people who felt useless or whose lives were a burden for themselves and their loved ones were killed, for example by stabbing or strangling, usually, but not generally, at the request of the Eskimo concerned, or rejected. According to Knud Rasmussen , suicide was common among the elderly in the Iglulik region. They too believed that violent death would cleanse their souls for the journey into the hereafter. The killing was carried out by hanging, shooting or stabbing. Eskimos who needed assistance in their suicide had to ask their loved ones three times in a row. Family members initially tried to dissuade the petitioner from doing the first two requests, but the third request was accepted as binding. Occasionally the suicide oath was withdrawn and dogs sacrificed for it. The actual suicide took place in public and in the presence of relatives. If the suicide was accepted, the victim had to dress like the deceased in general. The death took place at a fixed place, where the material possessions of the deceased were also destroyed. According to Statistics Canada, suicide was the second leading cause of death in Inuit Nunavut Territory in 2004 . For more details on past and present suicide by the Eskimos , see Inuit Culture (section Death) .

Ainu culture:

In the Ainu religion the view exists that the soul of a man who suicide commits going to a spirit or a sort of demon, which the survivors shall visit to that fulfillment to find (Tukap) which had been denied to her in life. If someone has insulted and verbally abused someone else in such a way that he committed suicide, he is considered jointly responsible for his death. According to Norbert Richard Adami, the background is that the Ainu ethics are primarily aimed at promoting harmony and solidarity between individuals and the community, which is accompanied by considerable social pressure to "resolve differences of opinion as amicably as possible," which is the Ainu culture from the western one , "with its much less developed payarity".

Legal evaluation

Germany

Constitutional law

In Germany, the basic law forms the external framework for the legal assessment of the suicide problem . The unchangeable guideline for this is the inviolability of human dignity according to Art. 1 GG. According to today's view, it is protected in the way that the individual person understands himself in his individuality and becomes aware of himself. From this it is deduced that the inviolability of human dignity also protects the individual from becoming the object of other people's definitions of human dignity. The inviolability of human dignity is given concrete form, especially in the right to free development of the personality , as long as this does not violate the rights of others or violate the constitutional order or the moral law ( Art. 2 GG).

According to the current view, this fundamental right includes the freedom to reject life-extending or health-preserving measures. There is disagreement as to the extent to which the exercise of this right of freedom violates the moral law. Religiously based values cannot be decisive for clarifying this question. Although religious freedom in Germany ( Art. 4 GG) allows individuals to live them, they cannot be imposed on others against their will. The same applies to values that are derived from philosophical and ideological systems, because none of them can claim to be universally valid . Following Kant's philosophy , from which the concept of the moral law is borrowed, no specific material evaluations are associated with it, but an examination of the question of the extent to which the actions of the individual could be the yardstick for general legislation ( categorical imperative ).

Criminal law

As an expression of the right to self-determination, attempted suicide is exempt from punishment in Germany ; until 2015, this basically also applied to participation , i.e. incitement or aiding and abetting , but not killing on request ( Section 216 (1) StGB ).

Since 2015, the commercial promotion of suicide in Germany, however, had been punishable by law (Section 217 of the Criminal Code). However, the BVerfG declared this provision unconstitutional at the beginning of 2020 due to the violation of general personal rights.

The induction of an incapacitated person or incitement by means of deception can be manslaughter or murder (of the suicide) as an indirect perpetrator ( Section 25 Paragraph 1 Alt. 2 StGB): The perpetrator of the homicidal offense is then the man behind who exerts influence, as he is responsible for the action largely dominated his behavior. A textbook example of such a course of action is the Sirius case .

Anyone who is obliged by a guarantor (e.g. relatives, doctors, etc.) to prevent suicide can be punished for manslaughter (or possibly murder) by omission if he fails to perform the required rescue action. The assistant, but also every chance witness of the event, can also be punished for failure to provide assistance in accordance with Section 323c of the Criminal Code if he does not provide assistance after the suicide has lost control of the perpetrator (e.g. because he is unconscious) . In the past, the Federal Court of Justice took the view that the finding of an unconscious but not yet deceased suicide constituted an accident within the meaning of Section 323c of the Criminal Code. This is controversial in the field of criminal law and is rejected primarily with the argument that a freely responsible accounting suicide is not an accident, but an expression of the individual's right to self-determination. On the other hand, the main objection is that additional people (ambulance service, emergency doctor, relatives) can usually not reliably check in this situation whether the suicide is really a freely responsible suicide. Incidentally, the entire situation of a suicidal person can also be interpreted in such a way that help is fundamentally necessary, i.e. even leaving a possibly suicidal person alone is a failure to provide assistance.

However, the general obligation to render assistance can compete with an existing advance directive and come to self-determination. Euthanasia as a homicidal offense, in contrast to dying care as an orderly, palliative medical action by the doctor, must also withstand ethical reasons. A (medical) care of the suicide can present itself as bodily harm if it is not justified by an emergency or the management without order (see also: medical liability ). Doctors are not obliged to save the lives of patients after attempting suicide against their will. In practice, in the event of an acute suicide, all life-saving measures that are still promising are usually carried out, since the existence or effectiveness of a living will can hardly be checked in the necessary haste.

Reform efforts in criminal law

The constitution opens up scope for greater acceptance of people's right to self-determination, even after their end of life. This has been repeated at the legislative level in the last few decades, but so far without success. Two reform proposals from the years 1986 and 2005, drawn up by lawyers and medical professionals, deserve special mention. In addition to a legal fixation of procedures for the cessation of medical treatment for the sick (so-called passive euthanasia), this should also apply to suicides. In the case of assisted suicide by an adult based on a serious decision, whoever fails to rescue the suicide who has become unconscious should no longer make himself a criminal offense. Finally, physicians are cautiously given the opportunity to actively help a terminally ill person to die after exhausting all therapeutic options to avert an unbearable and incurable disease. These proposals met with the full approval of the 2006 German Lawyers' Conference.

Mental Illness Laws

Anyone who threatens or announces suicide must expect to be forcibly admitted and treated in a psychiatric clinic because of considerable self- endangerment . The legal basis are the mental health laws of the federal states. The legal prerequisite for this serious interference with fundamental rights is that this self-endangerment is based on a condition classified as a mental illness .

Insurance law

According to German law, life insurance also pays in the event of suicide if the act was committed in a state of insanity ( Section 161 VVG ) or more than three years have passed since the start of the insurance. This period can be increased by means of an individual agreement. In all other cases, only the surrender value including surplus will be reimbursed. In this way, the insurers are protected in particular against persons whose intention to commit suicide has already been determined when the insurance contract is concluded and who want to care for their surviving dependents at the expense of the insured community. More details are usually given in the general life insurance conditions.

In the Insurance Contract Act valid until December 31, 2007, payments were only made in the event of suicide if the person was insane. The rules can be deviated from in favor of the policyholder.

Austria

Suicide is also unpunished in Austria; In contrast to Germany, murder was expressly differentiated from suicide in criminal law ( Section 75 of the Criminal Code ). However, killing on request (Section 77 of the Criminal Code) and “participation in suicide” (Section 78 of the Criminal Code), which are punishable by imprisonment from six months to five years, are punishable. Killing on demand occurs when the act that leads directly to the death of another is undertaken by the perpetrator himself at his express and serious request. “Participation in suicide” requires that the perpetrator induces another to undertake the act that is intended to lead directly to his death himself, or that he enables or facilitates the undertaking of such an act in some way. “Participation in suicide” can also take place through psychological or moral support.

Active euthanasia is punishable in Austria and falls either under the criteria of murder (Section 75 StGB), killing on request (Section 77 StGB) or “participation in suicide” (Section 78 StGB). On the other hand, passive euthanasia is not punishable, or the renunciation of life-prolonging measures when dying, if a patient currently wishes this or has expressed this wish in advance with a valid living will. Active indirect euthanasia is also permitted, which is understood to mean medical measures that alleviate a person's suffering using all possible means, even if this may shorten the dying process.

As in Germany, even willfully allowing suicide to be committed is only a burden for those who are legally obliged to intervene as a result of the law (e.g. relatives, doctors, etc.). However, anyone who fails to provide an injured person with the help obviously necessary to rescue them from the risk of death or serious bodily harm or damage to health is deemed to be a failure to provide assistance (Section 95 StGB).

According to the OGH finding (OGH 14O s 158/99), a minor lacks the necessary maturity to grasp the full scope of his decision to commit suicide and to be able to control his behavior according to this insight. In the absence of a serious willingness to die that can be attributed to an underage person, assistance given in suicide is not to be assessed as "involvement in suicide" (Section 78 StGB), but as murder (Section 75 StGB).

Switzerland

In a judgment of November 3, 2006 (2A.48 / 2006 / 2A.66 / 2006), the Swiss Federal Supreme Court reformulated suicide as a human right : “The right to self-determination within the meaning of Article 8 of the ECHR ( European Convention on Human Rights ) also belongs the right to decide how and when to end one's life; this at least insofar as the person concerned is able to freely form his or her will and to act accordingly ”.

Swiss criminal law only punishes people who, for selfish reasons, induce someone to commit suicide or assist them in doing so, with a maximum of 5 years imprisonment for both an accomplished deed and an attempt. In practice, this formulation allows a large gray area for euthanasia . This makes Switzerland one of the most liberal countries in this regard. Organizations based in Switzerland such as Exit and Dignitas offer their members euthanasia at low cost. This makes Switzerland a point of contact for so-called “dying tourists” worldwide. In 2016, 928 people ended their lives with the help of Exit . Efforts are being made to tighten the criteria and to regulate euthanasia differently.

The Military Criminal Law indirectly prohibits suicide through mutilation (Art. 95 MStG), provided that the attempted suicide has consequences for health: Anyone who, through mutilation or in any other way, makes themselves unfit or unfit for military service, either permanently or temporarily, in whole or in part Anyone who makes another person unfit for a period of time, in whole or in part, with his consent, by mutilation or in any other way to fulfill his military service obligations, is punished with imprisonment of up to three years or a fine.

Great Britain and northern Ireland

In the UK , suicide was a criminal offense until 1961. The criminal liability was based on the fact that the crown loses a subject through suicide.

reception

Movie

- The German film Die Sünderin (leading role: Hildegard Knef ; first screening January 1951) was the object of criticism and moral indignation in the 1950s : on the one hand, because the main actress (she played a prostitute named Marina, who is the nude model of her terminally ill lover) was few Seconds was seen naked; secondly, because he interprets the themes of euthanasia and suicide: Marina makes the blind lover with sleeping pills euthanasia . and then kills himself suicide was ranked in the Catholic and the Protestant churches long as serious sin, partly based on the commandment "Thou shalt not kill "( Ex 20.13 EU ). Marina's suicide can be perceived as “death as a way out” or “death as a viable path”; as well as social criticism : "Society taboos or condemns euthanasia so much that those who have euthanized altruistically only have to commit suicide or emigrate in order to escape the impending social ostracism".

- The sea in me (2004, original title: Mar Adentro ). A film based on a true story about the Galician sailor Ramón Sampedro , who suffered a form of paraplegia ( quadriplegia ) as a result of a swimming accident at a young age and no longer sees any meaning in his life. The film accompanies him in his desperate but ultimately futile fight for the right to active euthanasia . With the help of a friend, Sampedro finally takes his own life.

- A Single Man (2009, A Single Man ). The film is set in Los Angeles in 1962. An aging homosexual literature professor who mourns his longtime partner, who died in an accident, prepares to commit suicide.

- The Virgin Suicides (1999, German subtitles The Secret of Her Death, director: Sofia Coppola ): In the 1970s, the Lisbon family lived in a small suburban house with their five closely guarded daughters Cecilia (13), Lux (14), Bonnie ( 15), Mary (16) and Therese (17). The film begins with a thirteen year old attempted suicide; she dies on the second attempt. Then the strict parents tighten the rules in the house drastically. One night all of the other four sisters also died of suicide. The parents move away; the neighbors will soon return to their daily routine. Only the neighbors, all of whom are in love with one of the daughters, continue to wonder for years how the suicides came about.

- Thread of Lies (2014, directed by Lee Han). After her 14-year-old sister dies, Man-ji discovers the reasons for her death and learns that she was bullied by her classmates.

- A Song of Love and Death - Gloomy Sunday (1999). In Budapest in the 1930s and 1940s: a love triangle between a waitress, a restaurant owner and a pianist. The song Gloomy Sunday runs like a red thread through the film. The song, composed in 1933, became known in the 1930s as the melancholy "Song of the Suicide" and became known again through the film in 1999, in German-speaking countries under the title Das Lied vom Sadigen Sonntag .

- Kurt Früh : Dällebach Kari (1970)

literature