Scissors grinder

Scissors grinders , sometimes also scissors and knife grinders or knife and scissors grinders , also knife grinders for short , are craftsmen who sharpen and repair blunt knives , scissors and other cutting tools. It is a training occupation that nonetheless requires a lot of experience.

Mobile knife and scissors grinders, also known as traveling grinders , and out of date cart grinders , have existed in Europe since the Middle Ages. Traditionally, they came from a few regions of origin in northern Italy and northwestern Spain . In addition, the traveling trade was practiced by the traveling people such as Sinti and Roma and is one of the traditional professions of the Yeniche , especially in Central and Western Europe . They went through the towns and offered the sharpening of knives and scissors. In the second half of the 20th century, the demand fell sharply and almost came to a standstill. The need decreased increasingly because cutlery in the domestic sector was less used overall as a result of the decline in general agricultural activity and the changing supply and buying behavior of food and textiles . The main reason for the lack of demand, however, is the drop in the price of new goods due to the mass production of cutlery.

In the meantime, the profession of knife and scissors grinder is rarely practiced and is therefore one of the crafts threatened with extinction. In addition, professional sharpening tools are increasingly available in stores for households and businesses. Since the end of the 20th century, the reduced general need for re-sharpening knives and scissors that have become blunt has mostly been served by a decreasing number of mobile, sometimes supraregional, small business owners as travel trades and by various stationary specialist companies, some of them by post.

However, there is still continuous demand from some industries and professional groups, such as in the catering industry, slaughterhouses and hairdressing salons as well as more demanding hobby cooks, who often use high-quality and usually very expensive cutting tools. In addition to the specialist trade , a number of stationary and mobile sharpening and grinding services have developed since the end of the 20th century, most of which offer specialized services .

history

Origin of the traveling trade and grinding technology

With the increasing demand for cutting and thrusting weapons , the scissors and knife sharpener emerged from the armorer's craft around 1500 . The name comes from his job of sharpening a pair of scissor blades to fit. During the production of swords and daggers, etc., they had to be sharpened several times, which was often done by the armorer's assistants. When, in addition to weapons, “good scissors and knives” were increasingly required by various trades and were also in demand in private households, the craft of cutlery developed in the 16th century . As a result, the increasing qualitative and quantitative requirements for the products led to a more extensive division of labor in the form of a split in the manufacturing process and new professional groups emerged, such as blacksmiths , hardeners , grinders , sword sweepers and later the Reider . The “ cutlery knife ” in particular went from being a special object of daily use for the nobility to an important everyday object for a broad section of the population. In addition, there was the generally increasing need for cutlery and scissors as well as flick knives , hip knives and other cutting tools. As with the armory, a decentralized production method prevailed among the knife makers, which was provided by "mostly independent small masters with their own workshops".

As a result of the wider spread and use of knives and scissors, etc., the need arose to sharpen cutting tools that had become blunt through use. In both knives and scissors, the blades wear out depending on the type and duration of use, in that the sharp blades are initially bent to the side in the minimal range and then torn out and jagged, which makes repeated grinding or re-sharpening necessary. This led to the touring trade of knife and scissors grinders, who used their standard equipment, usually a grinding wheel , to travel across the country and through the cities, offering and performing resharpening.

As patron of the scissors grinder applies - such as, among others, in the armories - the Saint Catherine of Alexandria .

The principle of grinding or (re) sharpening is always the same: The cutting edge , such as a pair of scissors, is moved lengthways over an even harder surface - a grindstone or a grinding wheel (grinding wheel) . The resulting heat may have to be dissipated so that the steel of the material to be sharpened does not lose its hardness, which is the case at temperatures above 170 ° C. The thin edges of knife blades are particularly vulnerable. The simplest device that can still be viewed in folklore museums is a mobile, elongated and open water tank, into which the round grindstone protrudes halfway from above. This is cranked with the foot or the left hand while the right hand guides the material to be sharpened. The water is used to cool the grinding wheel and thus also the material to be sharpened. The hand crank or the (foot) pedal drive was rarely operated by a second person.

The grinding wheel was immediately cooled, mainly by means of a storage and drip container with an adjustable drain cock, which was attached above the wheel and from which the grinding wheel was wetted with water (or partly with grinding oil ). In addition to the better adjustability, this brought the advantage of weight reduction for transportable grinding racks or for the later grinding carts .

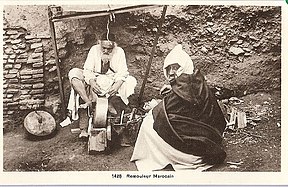

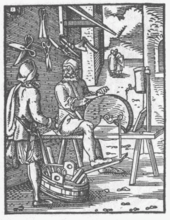

→ See, for example, the corresponding device in the illustrated woodcut "Der Schleyffer" by Jost Amman from his "Ständebuch", around 1568.

Cart grinder, Moleti, Arrotini, Afiladores

As demand emerged, scissors grinders began offering their services as wandering craftsmen in the 17th century. In the beginning, they usually used a transportable sanding frame with the sanding wheel that they carried on their backs. In some cases, however, they also used the larger grinding wheels that were mostly available in settlements and remote courtyards, and thus only offered their artistry as knife and scissors grinders.

From the end of the 17th century, the transportable grinding frame was mainly replaced by the more robust grinding cart and so-called cart grinders moved from place to place. In the course of technical advancements in Europe and the Middle East, differently constructed grinding carts or grinding carts emerged , such as the " Austrian grinder" which is widespread in Central Europe . With the end of the First World War in 1918 and "with the industrial manufacture of cutlery, the trade of the cart grinder died out".

Many of the wandering craftsmen came from what was then Welschtirol (later: Trentino) and mainly belonged to a few families from the high valley of Val Rendena - also known as Valle dei Moleti (German: `` Valley of the knife grinders '') - north of Riva del Garda . As so-called " Moleta " they spread the scissor-grinder craft not only throughout Europe, but also in the USA and many other countries around the world. In addition to the seasonal or long-term migration of men from the Welschtiroler Tal , many of them emigrated permanently and settled abroad.

Another region of origin was the Résia Valley in Friuli , Italy , where there was (also) too little work and the men as scissors grinders , so-called “ Arrotini ”, traveled all over Europe and above all through the former countries of Austria-Hungary to help their families survive to back up. The typical Arrotini grinding carts were replaced in the 1960s by converted bicycles in which the grinding wheel is firmly mounted between the handlebar and saddle. After jacking up the rear wheel with a foldable or separate stand, which also makes the jacked up wheel stable, the grinding wheel can be driven by the normal pedals via a belt or a separate chain. More recently, motorization has taken place through the use of motor-driven work equipment and correspondingly modified motor vehicles . In the meantime, this traveling trade is no longer important.

In the rural Spanish region of Galicia , the tradition of the scissor grinder can be traced back to the late 17th century. The so-called "Afiladores" came mainly from various places in the north of the local Ourense province and left their cultural imprint there. Thus a separate guild language developed , the Barallete , which is based on the Galician language and enriched it with a mixture of technical knowledge and the traveling handicraft of the Galician scissor grinders. The original work tool of the Afiladores was a frame with the grinding wheel, which they carried on their backs. Later it became a grinding cart that was pushed, then an adapted "scissors-grinder bike" like the Italian Arrotini and finally a motorization took place. In the meantime, the afiladores' trade also lost its importance.

- Cart grinders, Moleti, emigrants, Arrotini, Afiladores

Cart grinder, around 1650 (etching by Adriaen van Ostade )

Scissors grinder ("Afilador") with grinding cart in Buenos Aires , 1870

Scissors grinder ("Afilador") with grinding carts in Oviedo in Spain, around the beginning of the 20th century.

"Moleta" emigrated to the USA with grinding carts in Boston , 1917

Typical “scissor grinder bike ” of the Italian “Arrotini” from the 1960s, here with the rear wheel jacked up

“Afilador” with a converted “scissor grinder bicycle” in Spain , 20th century.

Traveling craftsmen, scissors grinders from the traveling people

Traveling merchants and craftsmen have been to be found in Europe since the Middle Ages , mostly Jews as well as Sinti and Roma . The cause lay in their social exclusion: They were not allowed to settle down as craftsmen in the cities and were not accepted into the guilds . They earned their living as traveling traders, peddlers , tinkers , scissors grinders or actors and artists . In the urban societies they sold goods that were often not offered by the urban traders. As craftsmen, their professions - like that of scissors grinder - covered a niche in urban handicrafts that on the one hand required a certain skill, but on the other hand was not enough for a living in the city. In rural society, the traveling craftsmen and peddlers were important for supplying them and meeting their needs until the middle of the 20th century.

In addition to the wandering craft journeymen and the seasonal migrant workers, such as the so-called Holland - goers , one of the phenomena was the permanent migration of marginalized groups who roamed the rural areas as vagrants and beggars or who lived from trade or small crafts as peddlers, scissors grinders and tinkers of the 18th and 19th centuries. According to the LWL museum director Willi Kulke, the number of traveling craftsmen was far larger than the historical representation at the beginning of the 21st century, because the written records are more than inadequate in these branches of business. Because of the low income opportunities and the competition from other traders and craftsmen, they were often forced to steadily expand their hiking radius. As a result, they had to live on the streets for a long time and ask for alms when the proceeds were poor . The transition to the vagabond way of life was fluid. The long life of the traveling artisans on the street led to many prejudices and rumors, whereby they were often regarded by their contemporaries as "morally depraved and suspected of theft".

The everyday life of the traveling traders and craftsmen was shaped by their difficult way of life. In addition, they were subject to constant regulations and legal restrictions, "which were intended to make life as difficult for them as possible and ideally to drive them out of the country". Initially, the authorities issued so-called trading patents , in particular for peddlers, some of which were also known as permits or charter , which can be viewed as the forerunners of the later traveling trade license . Such official regulations existed not only in all parts of Germany, but also in many countries in Central and Western Europe.

The traveling traders and craftsmen transported their goods or work equipment and tools on their own, with a wheelbarrow or handcart , with a backpack basket or a vendor's tray . Owning a team of dogs or a horse and cart was considered a social advancement. The typical grinding carts used by the touring scissor grinders mostly had only one wheel, which served both as a drive wheel ( flywheel ) for the grinding wheel and to transport the grinding cart. For his sharpening and grinding work, the scissors grinder stepped behind the device, placed the leather drive belt over the flywheel and drove the grinding wheel. Most of the grinding carts were only equipped with one grinding wheel - only better equipped scissors grinders were able to switch from one or, in some cases, several grinding wheels to a polishing wheel.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, from the rural poverty layer began Tyrol , the Switzerland and southern Germany originating Jenischen to wander and practiced it as a traditional fringe of society similar professions like the ethnic minorities of Roma and Sinti " basket weavers , rag pickers and [ especially " scissors grinder ". The latter professional group became the typical appearance of the traveling people, who primarily moved from spring to autumn, because of the grinding tools they carried with them, the grinding cart . In general terms, the settled population in the German-speaking area referred to these “travelers” as well as the entirety of the Roma, Sinti and Yeniche up to modern times as “ Gypsies ”.

- Between increasing exclusion and meeting needs

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Verein für Socialpolitik took up the beginning social discussion about the expanding trade of traveling traders and traveling craftsmen in the German Empire and carried out an extensive study. However, the focus was on economic aspects, such as the complaints of traders and craftsmen or their associations about "the allegedly business-damaging competition of peddlers", while the social issues of their activity were neglected. In 1898/99 the Verein für Socialpolitik published its findings under the title Investigations into the situation of the peddling trade in Germany in five volumes, with the association including both the negative contemporary opinion about the life of traveling traders and craftsmen and the increasing state sanctions and Regulations such as the restrictive issue of traveling trade licenses were also described in detail. However, the Verein für Socialpolitik also found in its report: “The pan-makers, basket makers, scissors grinders […] partly belong to the gypsies, but on the whole they are of a different kind and already form a more solid group of the wandering people, because they at least operate useful businesses and were more restricted in their journeys to certain areas. "

In the 1920s to the 1930s there was once again an increase in the number of scissors grinders and peddlers: the global economic crisis and mass unemployment forced people to make a living with retail trade or manual labor “on the streets”. While peddlers were again more numerous in rural areas, in urban areas it was mainly migrant workers such as scissors grinders who offered their services.

In Germany , from the beginning of the 19th century to the Porajmos in the time of National Socialism, there were often storage areas for the traveling people in regions with a corresponding need for recurring handicraft and maintenance work such as re-sharpening cutting tools. The craftsmen doing the wage labor did not have a workshop, but the work was carried out at the customer's premises. This also included, in particular, scissors grinders who, for example, regularly found work on the Swabian Alb with its traditionally many textile companies . The scissors were sharpened and tested on site. Such a storage area for Sinti and Roma caravans existed, for example, in the Zollernalb district in what was then the village of Steinhofen , with an inn in neighboring Bisingen serving as the registration point for the required trade licenses.

Although the racially motivated persecution of the traveling people by the Nazi state ended with the Second World War , exclusion and a lack of social participation also continued in the German successor states. In this respect, the wandering scissors grinders and other traveling craftsmen, who reappeared in the post-war period and with the beginning of the economic miracle , continued to face prejudices and discriminated against them as "gypsies".

- Traveling craftsmen, scissors grinders from the traveling people

"Mobile" scissors grinder with grinding cart in Marseille , early 20th century.

Scissors grinder with grinding cart in Vienna , around 1905–1914

Yenish scissors grinder in Switzerland , around 1930

Scissors grinder with "Dutch grinding cart" in Amsterdam , around 1930

Scissor grinder in the Netherlands, 1931

Travel routes and areas

As a rule, there were no agreements about travel routes and "areas" of the wandering scissor grinders among themselves, especially since there were no associations such as guilds or associations. Only among the traveling craftsmen from the same region of origin in Welschtirol, Italy and Spain or from the same ethnic group and “home region” of the traveling people did informal agreements take place or there were sometimes traditional territorial claims. The “Afiladores” from Galicia traveled mainly through Spain and neighboring Portugal , while the “Moleta” from Welschtirol and the “Arrotini” from Italian Friuli traveled to certain European countries as well as many other countries around the world. They often covered enormous travel routes and were sometimes on the move for years.

In the rural areas they frequented, they often encountered competition from local small-scale craftsmen who were looking for a living as traveling craftsmen and who offered their services in their local or regional environment. For the nationally wandering scissors grinders from the particular regions of origin or from the traveling people, this meant that the expected need and earnings could often not be assessed due to the local and regional competition - and ultimately always changes to the actually planned travel route were made, as well as longer intermediate routes without Earning potential had to be coped with.

Decline in the traveling trade in modern times

In many countries in Western and Central Europe, including Germany, until the second half of the 20th century, traveling scissors grinders came "at regular intervals to the residential streets to offer their services in households and to sharpen scissors and knives if necessary" . In the 1950s to 1970s, however, modern mass production and a broader supply of consumer goods made the purchase of scissors and knives so cheap that it was often more cost-effective to replace the outdated cutting tools with cheap products. In addition, the change in the world of work as a result of the post-war boom ("economic miracle") led to a sharp decline in general agricultural activity, so that maintaining the sharpness of the cutting tools used in this area increasingly faded into the background. At the same time, average private households increasingly supplied themselves with partly and fully prepared food as well as with ready-made textiles, so that the private use of cutting tools generally declined and resulted in a reduced need for re-sharpening by scissor grinders. In addition, this development was accelerated by the emergence of hardware stores and the availability of affordable sharpening tools and grinders . In the meantime, professional sharpening tools such as manual or electrically powered knife sharpeners are increasingly available in stores for households and businesses . However, hardware store equipment with a “scissors program” only pulls the upper side of the scissors without dismantling them, while professional scissors grinders, on the other hand, usually dismantle scissors and regrind both cutting surfaces.

As a result of the lack of demand, the regular visits by scissors grinders initially decreased and finally ended almost entirely.

In addition, the industry has fallen into disrepute due to fraudulent "scissors grinders" going from door to door in many places, who seek to take advantage of their customers through inferior and overpriced services or are even out to steal from trickery . The incorrect grinding technique often practiced by such "peddlers" and / or insufficient cooling can cause the blade to "burn out", which means that "the sharpened object becomes virtually useless".

present

Development since the end of the 20th century

Since the end of the 20th century, scissors grinders have become less and less common, as only a few people still need their services. Exceptions are professional users such as hairdressers , cooks , butchers or tailors , who still count on high-quality - and often very expensive - cutting tools. These must be expertly sharpened at regular intervals to ensure accurate and fatigue-free work. In addition, "more demanding amateur cooks [...] are now ready to let sharp knives taste something".

In Germany, scissors grinders belong to the professional group of grinders , but in contrast to tool grinders , who have been known as cutting tool mechanics specializing in cutting machine and knife forging technology since the late 1980s , or scissors and cutlery grinders , they are not an apprenticeship, but only a training occupation. The related artisanal apprenticeship has been called precision tool mechanic since August 2018 . The surgical mechanic makes scissors for medical purposes and also sharpens them. In addition, "grinding and repair jobs [...] are among the most frequent jobs of cutlers ", which are also among the trades at risk.

Similar to the scissors and cutlery grinders active in the production of cutlery - which can be found in Germany especially in the Bergisches Land - the profession is characterized by "special requirements" and requires a lot of skill and experience. The sharpening of scissors and cutting tools of various kinds "on the grinding machine requires a particularly good eye, excellent knowledge of the material and an extremely steady hand". This applies in particular to the resharpening of scissors, especially their insides (hollow sides) as well as scissors with curved scissor levers such as surgical scissors or nail scissors , whereby a lot of experience and specialist knowledge as well as special sharpening tools such as plating discs are required.

As in Germany, in Austria, Switzerland and Italy ( South Tyrol ) there is also no professional training for knife and scissor grinders , so that the necessary specialist knowledge and skills can only be acquired through " training ". In Austria, as in other countries, the sharpening of cutting tools is also part of the activity of the related, crafted apprenticeship of the cutler; however, since the end of the 20th century there has been no apprenticeship (training) to become a cutler in Austria. In Switzerland there is still basic vocational training to become a cutler, but the craft profession is threatened with extinction. There is no formalized training to become a cutler in South Tyrol. For the related German apprenticeship as a precision tool mechanic, there is no comparable training offer in Austria, Switzerland and South Tyrol.

Travel trade, fixed and mobile grinding companies

Since the end of the 20th century, there has been a declining number of mobile scissors and knife grinding shops in Germany - in addition to various stationary grinding companies with shops, some of which are also mobile - which are mostly at weekly and annual markets or in supermarkets - parking lots etc. Stop. They are mostly run by small business owners as travel trades , with some of them also acting as outpatient traders and selling knives and scissors on the side. Common features of the mobile grinding workshops, usually in small workshop trailers or trucks are housed mainly include electric grinders with "grinding stones [n] with coarse and fine structure" as well as special " serrated -stones [n]", inter alia, "Help frequently used hairdressing scissors blades to get their original sharpness". In addition to the conventional cooling with water or grinding oil, grinding is now partly "oil-based", using oil-soaked diamond grinding stones . The water or oil that evaporates during grinding ensures that the grinding wheel and the material to be sharpened are cooled. Polished the Schärfgut after grinding is usually by means of an electric polisher with special polishing wheels, such as, for example, Hirschhorn or canvas - lamellae .

In particular in the "Blade City" of Solingen , the center of the German cutlery industry in the Bergisches Land, as well as in Tuttlingen in Baden-Württemberg with its large number of medical technology companies, there are a number of stationary grinding companies that produce reground knives and scissors (Solingen) or reground surgical scissors etc. (Tuttlingen) by post. In contrast, many of the mostly medium-sized companies in the clothing and textile industry that still exist in Germany, such as those in the Swabian Alb up to the present (2020), are regularly visited by scissors grinders who do their work on site. There are also some "travel grinders" who offer their services nationwide on fixed dates in retail stores such as household and hardware stores and at consumer fairs.

In the Austrian-Italian region of Tyrol, several scissor grinders were still circulating in small trucks around 2015.

In southern and southeastern Europe towards the end of the 20th century, instead of the “scissor grinder bicycles” from the Arrotini, partially converted scooters or small motorcycles were used, and ultimately also three- wheeled box vans up to small vans and small trucks with one or more - on a motorcycle or mounted in the structure of the commercial vehicle - grinding wheels are connected to the gearbox shaft of the engine or are partly also operated electrically.

Similar developments in the industry have taken place in many countries around the world. While in underdeveloped countries and regions up to the present (2020) there are still some traveling craftsmen with often the simplest grinding equipment, mobile scissors and knife grinders are currently mostly on the move with converted bicycles or motorcycles or appropriately equipped vans or small trucks. Overall, however, their number has declined sharply in recent decades, especially in industrialized and emerging countries .

In the countries of the Anglo sphere as British Isles ( UK and Ireland ), United States , Canada , Australia and New Zealand has a sharpening booth often an integral offer of traditional "Farmers' markets' ( farmers' markets ) that there regularly and especially in take place in rural areas. Usually it is a sharpening and grinding service based in the respective region, which can build up a regular customer base. In these countries, the sharpening and grinding services often use so-called wet grinding machines with electric drive , in which a slowly rotating grinding wheel runs on one side through a water bath and is thus cooled. In addition, special, also electrically operated belt grinding machines are often used. Such wet and belt grinding machines can sometimes also be found at sharpening and grinding services in Scandinavia , Germany, Austria , Switzerland and some other European countries; in addition, they are often used by other manual users.

In addition, there are now a number of mobile sharpening and grinding services in Germany and many other countries that carry their mobile sharpening equipment with them in small vans and - like their local predecessors from the traveling people who worked for textile companies in the past - to order their customers come where they do their work on site. Often they have specialized in certain industries and are also active in a regionally limited area.

The particular specialization, for example, aimed at industrial kitchens , hotels , catering and slaughterhouses (sharpening of cutting tools, such as cooking tools, cutlery, knives, slicers knife , cutter knives , meat chopper knives and meat grinder discs), hairdressers (sharpening of hairdressing scissors) or municipal green area offices , horticulture and landscaping plants and forest holdings (Sharpening of lawn mower blades as spindle, lower and sickle blade, saw chains of chainsaws as well as other gardening equipment). The main advantage for customers is that the cutting tools are immediately available again and any replacement equipment is not required when they are taken away. In addition, if the cutting performance is insufficient, there is usually immediate (free) rework.

In some cases, these mobile grinding services also offer special repair work or take on related additional services such as the regular dressing or grinding of cutting boards and chopping blocks made of plastic or wood in accordance with the HACCP EC hygiene standard in catering and slaughterhouses .

- Scissors grinder since the beginning of the 21st century

Scissors grinder with a "modern grinding cart" in Paris , 2008

Scissor grinder with a converted bicycle in Rome , 2011

A scissor grinder with a converted scooter in Tossa de Mar , 2009

Workshop trailer of a mobile scissors grinding shop in Bremen , 2017

“Small workshop truck” of a mobile scissors grinding shop in New York City , 2010

Mobile sharpening service in Hampshire, 2019

Market situation towards the beginning of the 21st century

The trade of the "wandering" knife and scissors grinders is generally under increasing market pressure as a result of globalization . The relocation of the mass production of cutlery to low-wage countries as well as the marketing in global online trade or as promotional goods by discounters , department stores and furniture store chains ensure continued and further price drops for new goods , especially since the use of newer technologies in production and factory sharpening such as steel material selection and remuneration , Laser cutting and sharpening technology as well as ceramic coating of cutting surfaces lead to useful results and longer edge retention . For the normal consumer with lower demands, replacing cutting tools that have become blunt by purchasing new ones is now usually cheaper and also causes less effort than regular professional re-sharpening. On the other hand, a few large and many long-established niche manufacturers for the professional need for knives and other cutlery, which are mainly located in Solingen in Germany, have been able to hold their own in the market and have even recorded sales growth since the end of the 2000s.

As a result, the need for re-sharpening and regular basic grinding of the cutting tools on the part of professional users and more demanding hobby cooks will continue to favor the development of the knife and scissors-grinding trade towards specialized service providers, which partly occurred at the end of the 20th century .

reception

General

The figure of the scissors grinder , the "stranger in the city" or in the town, not only inspired the vernacular , but also many artists and cultural workers, such as painters, sculptors, authors, photographers, filmmakers, composers and musicians.

In everyday culture , the motif of the traditional scissors grinder with its typical grinding wheel can also be found on decorative objects, ornamental figures or toys, such as:

- decorative porcelain sculpture (as from the Meissen Porcelain Manufactory )

- A rather rare, decorative bronze figure (such as the bronze figure “Scherenschleifer-Lighter” from Vienna around 1900, which shows a scissors grinder with a grinding cart at work, where the grinding wheel serves as an ignition surface for matches) or very rarely as an ivory figure

- decorative carved wooden figure , partly as a Christmas crib figure

- historical tin toys (such as from the former toy manufacturer Arnold from Nuremberg)

- Tin figure or as part of tin figure groups

Currently (2020) various museums and exhibitions deal with the historical life and working world of traveling knife and scissor grinders, with typical tools, documents and photographs being shown. In addition, some memorial sites have recently been created in the earlier regions of origin of the "Moleta" and "Arrotini" in Italy and the "Afiladores" in Spain , which are dedicated to the history of the scissor grinder with special museums, exhibitions, events and in the form of monuments .

→ See also the following subsection Museums, Exhibitions, Places of Remembrance and Monuments

The Scherenschleiferstraße in Lüneburg's old town is named after the trade of the scissors grinder .

Sayings, fairy tales, folk songs

The trade of the scissors grinder used to be viewed in a derogatory way. So exist to the present day (2020) in the Swabian the dirty word "Scheraschleifer" which describes a rascal who is unreliable and can not be trusted. Some of the wandering scissors grinders - including on the Swabian Alb with its once many textile companies - did not provide sustainable sharpening with poor tools and sometimes inability (too high temperature of the grinding material, disproportionate amount of material removal), so that the knives and scissors quickly became blunt again.

Occasionally, scissors grinders used to have a trained monkey with them to attract audiences. This is where the cyclist saying comes from : He sits there like a monkey on the grindstone - of course the animal never "sat" on the turning stone, but kept jumping up and down with its backside.

In the fairy tale Hans im Glück (Hans im Glück) by the Brothers Grimm , the scissors grinder is Hans’s very last and poorest exchange partner, and he too takes advantage of him.

The figure of the scissor grinder is treated in various, mostly folk songs . A (slippery) folk song that takes up the theme of the wandering men and is still uttered in the present (2020) in southern Germany at festivities or at some later hours in the tavern is called Wir sind die Schleifer . Otto Hausmann's popular poem Der Scherenschleifer was set to music in 1890 by Robert Kratz (1852–1897) as a “folk song for male choir”. In Flanders , Jan Bois published in his collection of Hundreds of Old Flemish Songs, published in 1897, among other things, a well-known scissor-grinder song from the Leuven region with the title Komt vrienden in het ronde . A German broadcast followed later (Come friends around) .

art

In the fine arts , especially in painting , depictions of scissors grinders were a popular subject. The most famous works include:

- Scissors grinder , around 1568, woodcut by Jost Amman from the book of estates

- The scissors grinder , around 1650, etching by Adriaen van Ostade

- The scissors grinder , 1808–1812, painting by Francisco de Goya

- Scissor grinder , around 1840, painting by Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps

- The scissors grinder , 1891, painting by Giovanni Giacometti

- The Knife Grinder , 1907, painting by Jean-François Raffaëlli

- The knife grinder , before 1913, painting by Carl Maria Seyppel

- The scissors grinder , 1913, painting by Kazimir Severinovich Malevich

- The knife grinder , 1926, woodcut by Todros Geller

- Scissor grinder , 1936, painting by Felix Nussbaum

The English sculptor Newbury Abbot Trent created several natural stone reliefs that show historic London street scenes for Buchanan House in London , which was built in 1957 , a high-rise in St. James’s district in Westminster . Underneath there is also a relief representation of a scissors grinder with his grinding cart at work, who is observed by a child.

Fiction

- Dino Larese : The scissors grinder. Story of a serene life . 5th edition. Huber, Frauenfeld 1995, ISBN 3-7193-0788-3 (Larese tells in the form of a fictional representation from his own memories about the hard life of his father, who throughout his life as a scissors grinder "on the Seerücken from Oberthurgau to Stein am Rhein" from Ort zu Place drew. First published: 1981).

- Johannes Vilhelm Jensen : Hverrestens-Ajes - Anders med slibestenen. In: Ders .: Himmerlandshistorier, tredie Samling. Gyldendal, Copenhagen 1910 (Danish; published as a German translation under the title Himmerlandsgeschichten in various, sometimes limited editions by several publishers. In the story, the Nobel Prize winner Jensen deals with the fate of a poor man from Himmerland who moves around as a knife grinder so that his family can survive .).

- Eugène Chavette : The scissors grinder . Novel (in four volumes). Hartleben, Leipzig 1876 (French: Le rémouleur . 1873.).

Photographs

The Austrian photographer Emil Mayer , who primarily documented Viennese street scenes and "types", is known to have made photos of scissor grinders in the streets of Vienna between 1905 and 1914.

In 1939, the German photojournalist Richard Peter portrayed a scissors grinder with his grinding cart as part of his worker photographs , which he portrayed as a self-confident and well-traveled craftsman. The series of five photographs taken in the Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR) is now in the possession of the Deutsche Fotothek in Dresden.

The inventory of the Deutsche Fotothek also includes a documentary photograph of a scissors grinder in a Berlin backyard from 1967 by the German photographer (and later RAF lawyer) Klaus Eschen .

Movie

- L'Arrotino (2001; Eng . “The scissors grinder”), 35 mm short film by Straub-Huillet .

- Under the Sky of Paris (1951; original title: Sous le ciel de Paris ), French feature film by Julien Duvivier with Albert Malbert in the role of the scissor grinder.

- Adieu Léonard (1943), French feature film by Pierre Prévert . The role of the scissor grinder is represented by Guy Decomble .

- Regain (1937), French feature film by Marcel Pagnol based on a novel by Jean Giono . One of the main characters in the film is the knife grinder Gédémus, played by Fernandel .

- Angèle (1934), French feature film by Marcel Pagnol based on a novel by Jean Giono. Charles Blavette took on the role of Tonin scissors grinder.

- Liliom (1934) , French feature film by Fritz Lang . The author, poet and actor Antonin Artaud plays the role of the scissors grinder and guardian angel.

music

In classical music , several composers dealt with the figure of the scissors grinder , such as Michel Pignolet de Montéclair (1667–1737) in his baroque piece of music Le rémouleur .

Museums, exhibitions, places of remembrance and monuments

About the historic hiking profession of knives and knife-grinder, inform various museums and exhibitions in particular some of Folklore and History Museums , open-air museums , and Arbeitswelt-, craft and industrial museums . The usual exhibits include typical tools such as portable grinding racks, grinding carts and the adapted “scissor grinder bicycles” from the Moleta, Arrotini and Afiladores, as well as documents and photographs. Such collections can be found, for example, in the following countries and museums (selection):

- Germany: in the German Agricultural Museum Schloss Blankenhain in Blankenhain in Saxony; in the Deutsches Museum in Munich; in the historical cutlery in Mössingen in Baden-Württemberg; in the Hohenloher open air museum in Schwäbisch Hall - Wackershofen in Baden-Württemberg; in the Elmshorn Industrial Museum in Elmshorn in Schleswig-Holstein; in the decentralized LWL industrial museum in Westphalia-Lippe; in the Lower Rhine Open Air Museum in Grefrath in North Rhine-Westphalia

- Netherlands : in the Ootmarsum open-air museum in Ootmarsum in the province of Overijssel; in the Zuiderzeemuseum in Enkhuizen in the province of North Holland

- Austria: in the district museum Landstrasse in Vienna; in the private "Historical Museum of all things cutlery with an experience grinding shop" (which was set up in the 2010s by Helmut and Waltraud Rief's grinding shop based in Hattingerberg in Tyrol)

- Italy: in the Museo etnografico del Friuli in Udine in Friuli; See also below for the places of remembrance, museums and monuments in the province of Trentino and in the Résia Valley in Friuli

- Spain: in the Museo das Mariñas in Betanzos in the province of A Coruña in north-west Galicia; see also below about the places of remembrance and monuments in the Galician province of Ourense

- Australia : in the National Museum of Australia in the capital Canberra (shown is the Saw Doctor's wagon , German 'Sägendoktor-Wagen' - mobile home and mobile grinding workshop by Harold Wright, with whom he traveled through the northwest with his wife and daughter from 1935 to 1969 from Victoria and New South Wales in Australia. The unique truck trailer has been owned by the National Museum of Australia since 2002 and is one of the “highlights” of the permanent exhibition after restoration.)

The LWL-Industriemuseum - Westphalian State Museum for Industrial Culture continued in its 2013 exhibition “Migrant work. Human - Mobility - Migration. Historical and modern working worlds ”deals with the phenomenon of labor migration . One of the total of 15 exhibition areas dealt with the historical touring profession of knife and scissor grinders under the title “Scissors Grinder - Strangers in the City”. The exhibits included, among other things, an adapted “scissor grinder bicycle”. The special exhibition was shown from 2013 to 2015 at four different locations of the decentralized industrial museum in Westphalia and Lippe . An exhibition catalog was published in 2013 as accompanying material .

In the northern Italian province of Trentino, the former Welschtirol, a memorial in the high valley of Val Rendena has been commemorating the historic hiking trade and the labor migration of men from the valley, who formerly wandered job seekers through Europe and partly to the USA and many , since 1969 other countries in the world emigrated. The monumental monument is located in the Trentino village of Pinzolo and consists of a larger than life bronze sculpture on a solid block of natural stone. The sculpture was created by the Italian sculptor and Franciscan Silvio Bottes and realistically depicts a scissor grinder sharpening knives on the typical pedal-operated grinder. The monument was financed by donations from many scissors grinders from all over the world who emigrated from Val Rendena . In 2018 an international meeting of knife and scissors grinders took place in the place. In the Trentino municipality of Cinte Tesino , a small grinder museum is dedicated to the former hiking knife grinders from the village and their working and living conditions.

Another place of remembrance is in the Résia Valley in Friuli, Italy, in the municipality of Resia in the district of Stolvizza, the "village of the Arrotini", the scissors grinder. The scissors grinder museum , which opened there in 1999, provides information about the former traveling craftsmen from the village and the Val Resia , who used to roam all of Europe and especially the countries of Austria-Hungary. A previously inaugurated in 1998 monument, consisting of a large, incorporated into a rock bas-relief made of bronze , shows a Arrotini with his typical converted "Scherenschleifer Bike" from the 1960s. Every year a Festa del arrotino , a "festival of the scissors grinders ", is celebrated in the town.

In the Spanish province of Ourense in Galicia, the traveling trade of the scissors-grinders, the Afiladores, who used to come from this region, is honored with a monument in the municipality of Nogueira de Ramuín . A life-size bronze sculpture, created by the Spanish sculptor Manuel García de Buciños , shows an afilador with his grinding cart sharpening a knife. The sculpture stands on a high stone pedestal with gargoyles in the middle of the water surface of a fountain . Another scissor grinder monument, also a bronze sculpture, is in the municipality of Esgos , which is located near Ourense .

media

literature

- Josh Donald: Sharp. The Definitive Introduction to Knives, Sharpening, and Cutting Techniques, with Recipes from Great Chefs . 1st edition. Abrams & Chronicle Books, London 2018, ISBN 978-1-4521-6306-2 (English).

- Marius, Mélanie Martin: knife. Recipes and Techniques . 1st edition. Callwey, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-7667-2282-9 .

- Willi Kulke: Scissors Grinder - Strangers in the City . In: LWL-Industriemuseum [Red .: Hendrik Bönisch] (Ed.): Migrant work. Human - Mobility - Migration. Historic and modern working environments . (Exhibition in the LWL industrial museum, brickworks museum Lage). 1st edition. Klartext, Essen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8375-0957-1 , p. 43–52 (exhibition catalog).

- Thomas Blubacher : How it used to be. Nice and interesting facts from grandmother's time (= Insel-Taschenbuch . No. 4272 ). Insel Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-458-35972-2 ( excerpt in the Google book search).

- Willy Römer : From the old craft. Nail blacksmiths, scissors grinders, file cutters… 1925–1931 (= Edition Photo Library . No. 23 ). Nishen, Berlin 1988, ISBN 978-3-88940-223-3 (illustrated book).

- Jost Amman , Hans Sachs : The status book . Frankfurt am Main 1568 ( page reproduction at Wikisource - original title: Detailed description of all stands on earth . 114 woodcuts by Jost Amman with verses by Hans Sachs).

watch TV

- One of the last of its kind: the mobile knife and scissors grinder Marco Sala . In: Franken Fernsehen , broadcast on April 18, 2018 (2:51 minutes)

- Angelo Schmid - mobile knife sharpener . In: ORF 2 , series today specifically , broadcast on May 25, 2015 (3:28 minutes)

- The scissors grinder - survival on a knife edge . In: SWR Fernsehen BW , series Mensch Menschen , broadcast on March 9, 2015 (30:00 minutes)

- Local time South Westphalia: The mobile scissors grinder . In: WDR television , local time series , broadcast on December 16, 2014 (3:40 minutes)

- Traveling grinder - knife grinder "Rief" . In: Tirol TV , series Allerhand aus'm Tyrolerland , broadcast on February 28, 2014 (3:11 minutes)

Radio

- Job description : Scissor grinder Romeo Weiß in the German Digital Library - radio broadcast of the SDR on November 29, 1994 (5:35 minutes; permalink to the archive unit R 1/005 D941071 / 108 in the finding aid of the Baden-Württemberg State Archives )

Web links

- The profession of "knife grinder " on rief-dieschleiferei.at (brief information, films and information flyers as downloads, list of links)

- Knife and scissors grinders. In: ballenbergkurse.ch. Course center Ballenberg , Hofstetten near Brienz (Switzerland)

- Jerry Finzi: L'Arrotino: The Knife Grinder, Quite a Sharp Tradition. In: grandvoyageitaly.com. June 1, 2016 (English).

Individual evidence

Note: Individual references given at the end of paragraphs refer to the entire paragraph before.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Willi Kulke: Scherenschleifer - Strangers in the city . In: LWL-Industriemuseum ; Red .: Hendrik Bönisch (Ed.): Migrant work. Human - Mobility - Migration. Historic and modern working environments . 1st edition. Klartext, Essen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8375-0957-1 , p. 43–52 (exhibition catalog).

- ↑ Johannes Großewinkelmann (edit.), Jochen Putsch (edit.): Forging - development of a trade from craft to factory . Ed .: Landschaftsverband Rheinland, Rheinisches Industriemuseum , Solingen branch, Hendrichs drop forge (= museum educational work materials . Issue no. 2 ). Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-7927-1065-X , p. 3–5 ( digitized at industriemuseum.lvr.de [PDF; 25.6 MB ; accessed on May 16, 2020]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g cf. B .: Anke Velten: Really sharp. In: weser-kurier.de . June 2, 2016, accessed on November 7, 2018 (article in the Bremen-West district courier ).

- ↑ Helmut Rief: The profession of the "knife grinder". In: rief-dieschleiferei.at. Helmut Rief, Volders ( Tyrol , Austria), accessed on October 4, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Helmut Rief: The cart grinder and its history! (PDF; 74 kB) In: rief-dieschleiferei.at. Helmut Rief, Volders, accessed on November 8, 2018 (information flyer).

- ↑ a b cf. E.g. History of Service Wet Grinding. In: servicewetgrinding.com. Retrieved on February 22, 2020 (self-information on the company history of the Service Wet Grinding Company in Cleveland , Ohio / USA , which was founded in 1905 by a scissors grinder from Val Rendena in Welschtirol and a US immigrant).

- ↑ a b c Cf. Comitato Associativo Monumento all'Arrotino: Arrotini Val Resia. In: arrotinivalresia.it. Comitato Associativo Monumento all'Arrotino, accessed November 11, 2018 (Italian).

- ^ Olegario Sotelo Blanco: Los afiladores. Una industria ambulante (= Fin de siglo . Band 14 ). Ronsel Ed., Barcelona 1995, ISBN 84-88413-12-2 (Spanish).

- ^ Hugh Thomas : Eduardo Barreiros and the recovery of Spain . Yale University Press, New Haven et al. a. 2009, ISBN 978-0-300-12109-4 , pp. 7th ff . (English).

- ↑ a b Jose Luis Dominguez Carballo: Lembranzas de Armariz: La emigración estacional o temporal >> Los afiladores. In: lembranzasdearmariz.blogspot.com. June 25, 2017, Retrieved February 8, 2020 (Spanish).

- ↑ a b c d e Willi Kulke: Scherenschleifer - Strangers in the city . In: LWL-Industriemuseum (Ed.): Migrant work . Klartext, Essen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8375-0957-1 , p. 43-47 .

- ^ A b Carsten Küther: People on the street. Vagging lower classes in Bavaria, Franconia and Swabia in the 2nd half of the 18th century (= critical studies on historical science . Volume 56 ). Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1983, ISBN 978-3-525-35714-9 , pp. 62 ff .

- ^ Willi Kulke: Scherenschleifer - Strangers in the city . In: LWL-Industriemuseum (Ed.): Migrant work . Klartext, Essen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8375-0957-1 , p. 48 .

- ↑ See e.g. B .: "Asocial" and Yeniche were humiliated. In: versoehnungsfonds.at. Austrian Reconciliation Fund , accessed on February 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Studies on the situation of the peddler trade in Germany. In 5 volumes (= Association for Socialpolitik : Writings of the Association for Socialpolitik . Volume 77-81 ). Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig (published: 1898/1899).

- ↑ Studies on the situation of the peddling trade in Germany (= Association for Socialpolitik : Writings of the Association for Socialpolitik . Volume 78 ). tape 2 . Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1898, p. 63 .

- ↑ a b Willi Kulke: Scherenschleifer - Strangers in the city . In: LWL-Industriemuseum (Ed.): Migrant work . Klartext, Essen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8375-0957-1 , p. 46-50 .

- ↑ See e.g. E.g. Paul Münch: Bisingen: An Oskar Schindler from Steinhofen? In: schwarzwaelder-bote.de . October 12, 2017, accessed January 28, 2020 .

- ↑ Siegfried Ruoss: There were many princes and little bread. From scissor grinders, brush binders and other little people in Württemberg . Theiss, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 3-8062-1770-X .

- ↑ See e.g. B .: Christian Wolpers: With education against antiziganism . In: Lower Saxony Memorials Foundation (Ed.): Annual Report 2014 . Self-published, Celle 2015, p. 21-23 .

- ↑ See e.g. E.g .: Julien Floris: “We are the fourth or fifth culture in Switzerland” . In: Tangram. Bulletin of the EKR . No. December 30 , 2012, p. 73–76 (German, French, Italian, digitized [PDF; 2.4 MB ; accessed on March 1, 2020] Interview with the Swiss Yenish traveler Benno Kollegger).

- ↑ a b c d e f cf. B .: Harald H. Richter: One of the last in the guild of traveling scissors grinders. In: op-online.de . May 10, 2018, accessed November 7, 2018 .

- ↑ Stephan Reporter: Who still grinds knives these days? In: hausjournal.net. Retrieved February 10, 2020 .

- ↑ See e.g. B .: Lucretia Jochimsen : Gypsies today. Investigation of an outsider group in a German medium-sized town . In: Sociological Current Issues, NF Volume 17 . Enke, 1963, ISSN 0081-3265 , p. 17 (also dissertation, University of Münster 1961).

- ↑ See e.g. B .: (lnp): Scissors grinders go from house to house: Are they cheaters? In: pnp.de . October 23, 2018, accessed November 8, 2018 .

- ↑ See e.g. B .: (wk): A stranger pretends to be a knife grinder and steals from the married couple. In: weser-kurier.de . March 16, 2017, accessed November 8, 2018 .

- ↑ See e.g. B .: Hubertus Heuel: The honorable scissors grinder. In: wp.de . April 27, 2014, accessed November 14, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Frank-O. Docter: Scissor grinder from Gießen is one of the last representatives of his profession. In: giessener-anzeiger.de . February 18, 2017, accessed October 5, 2019 .

- ^ A b Marius, Mélanie Martin: knife. Recipes and Techniques . 1st edition. Callwey, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-7667-2282-9 .

- ↑ Legal ordinance: Surgical Mechanic Training Ordinance of March 23, 1989 (Federal Law Gazette I, p. 572) . Ed .: Federal Law Gazette 1989.

- ↑ a b cf. E.g .: knife and scissors grinders. In: ballenbergkurse.ch. Course center Ballenberg , Hofstetten near Brienz (Switzerland), accessed on October 6, 2019 .

- ^ A b Zweckverband Naturpark Bergisches Land (ed.): Bergische Berufe. Zweckverband Naturpark Bergisches Land, Gummersbach 2012, p. 6–7: Scissors and cutlery grinder ( digital copy ; PDF, 8.7 MB).

- ↑ See e.g. B .: F. Klopotek, J. Putsch: Development stations of the Solingen cutlery and cutlery industry . In: Association of German Engineers , Bergischer Bezirksverein (Hrsg.): History of technology from the Bergisches Land. People and machines through the ages . Born, Wuppertal 1995, ISBN 3-87093-072-1 , p. 60-72 .

- ↑ See e.g. B .: Antonia Löffler: The man who brings back the polish . In: The press . October 23, 2016 ( diepresse.com [accessed May 17, 2020]).

- ↑ See e.g. E.g .: cutler. In: ballenbergkurse.ch. Course center Ballenberg , Hofstetten near Brienz (Switzerland), accessed on May 17, 2020 .

- ↑ See e.g. B. Information in the transnational information database of the European Vocational Training Atlas .

- ↑ See e.g. B .: Carina Schriewer: Sandro, the master of sharp blades. In: nordbayern.de . April 19, 2014, accessed October 4, 2019 .

- ^ Gerhard Halder: Structural change in clusters using the example of medical technology in Tuttlingen . Lit, Münster 2006, ISBN 3-8258-9243-3 , pp. 145 (also dissertation, University of Stuttgart 2005).

- ↑ See e.g. B .: Ilka Platzek: Always a sought-after man: the mobile knife sharpener. In: rp-online.de . September 13, 2019, accessed February 1, 2020 .

- ↑ See radio report by the radio station Österreich 1 (Ö1), broadcast on October 30, 2015, 2:18 p.m.

- ↑ a b c d e f cf. E.g .: Kristine M. Kierzek: Local sharpening crews can help you baby your knives so they last a lifetime. In: eu.jsonline.com. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel , January 9, 2020, accessed January 31, 2020 .

- ↑ See e.g. B .: (zautor): How the knife makers from Solingen survived. In: capital.de . April 13, 2019, accessed January 31, 2020 .

- ↑ The second 100 Swabian words >> serial no. 182: Scheraschleifer. In: heimatverein-moeglingen.de. Heimatverein Möglingen , accessed on March 1, 2020 .

- ↑ See e.g. B .: Klaus Gimmler: Gustl Krapf was the cutler of Karlstadt. In: mainpost.de . March 7, 2017, accessed March 1, 2020 .

- ↑ We are the grinders. In: lumpenlieder.de. Karl Schupp, accessed October 4, 2019 .

- ↑ See: Otto Hausmann : The scissors grinder . Poem. In: Wikisource .

- ↑ Robert Kratz: The Scheerenschleifer . Music printing. Based on a poem by Otto Hausmann . Score. Kistner, Leipzig 1890 ( three songs in folk tone for male choir , No. 2).

- ↑ De Scheresliep / Komt vrienden in het ronde. In: benhartman.nl. Retrieved January 28, 2020 (Dutch).

- ↑ Des Schleifers Weis' / Friends come round. In: ingeb.org. Retrieved January 28, 2020 .

- ↑ Historical cutlers. In: moessingen.de. Retrieved August 20, 2020 (two workshops in their original condition, from the second half of the 19th century and from 1920).

- ↑ HLFM leaflet "Auf der Reis" - The 'unknown' Yenish minority in the southwest ". (PDF; 6,047 KB) In: wackershofen.de. Retrieved on August 22, 2020 (the permanent exhibition, which opened in 2017, provides information on the culture and way of life of the Yenish people who, among other things, traveled across the country as scissors grinders and sold their services on the “Reis”).

- ↑ Bettina Hachenberg: Travelers are settling in Heuberg. In: STIMME.de . July 24, 2020, accessed August 22, 2020 .

- ↑ Object of the month August 2012: scissor wheelbarrows. In: industriemuseum-elmshorn.de . August 2, 2012, accessed February 16, 2020 .

- ↑ "Historical museum all about cutlery" with experience grinding shop. In: rief-dieschleiferei.at. Retrieved February 15, 2020 .

- ↑ Collection highlights: Saw Doctor's wagon. In: nma.gov.au. National Museum of Australia , accessed February 16, 2020 .

- ↑ Migrant work. In: lwl.org. LWL-Industriemuseum , 2013, accessed on February 15, 2020 .

- ↑ Madonna di Campiglio >> Pinzolo >> Scissor Grinder Monument . In: tour.campigliodolomiti.it. Retrieved on February 27, 2020 (Italian, English, German, see information text in the pop-up window).

- ↑ Storia della Val Rendena. La "Val da la trisa" or the Valle dei Moleti. In: pinzolodolomiti.it. Retrieved February 7, 2020 (Italian).

- ↑ Schleifer Museum - Cinte Tesino. In: cultura.trentino.it. Retrieved February 7, 2020 .

- ^ Scissor Grinder Museum. In: tarvisiano.org. Retrieved February 7, 2020 .

- ^ Scissors Grinder Museum. In: alpenvereinaktiv.com. Retrieved February 8, 2020 .

- ↑ Arrotini Resia. In: arrotinivalresia.it. Comitato Associativo Monumento all'Arrotino, accessed February 7, 2020 (Italian).

- ↑ Gisela Hopfmüller , Franz Hlavac : Experience Friuli: Plants - Kitchen - Joy of Life . Styria Regional Carinthia, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-7012-0122-8 , p. 198 ff .

- ↑ Monumento al Afilador. In: coloresymiradasanaviso.blogspot.com. Retrieved February 8, 2020 (Spanish).