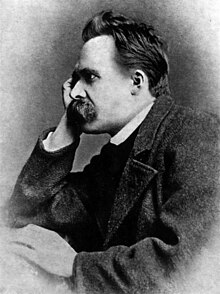

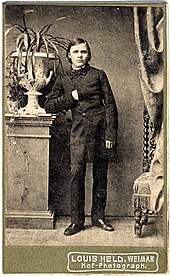

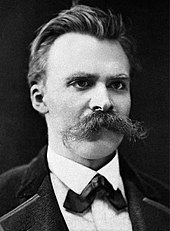

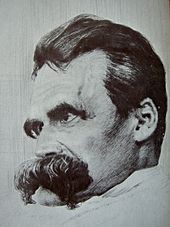

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (pronunciation: [ˈniːtʃə] or [ˈniːtsʃə] ; * October 15, 1844 in Röcken , † August 25, 1900 in Weimar ) was a German classical philologist . Posthumously his writings made him world famous as a philosopher . In the sideline he created poems and musical compositions . He was initially a Prussian citizen, but after moving to Basel in 1869 he was stateless .

At the age of 24, Nietzsche became Professor of Classical Philology immediately after completing his studies at the University of Basel . Ten years later, in 1879, he resigned the professorship for health reasons. From now on he traveled to France, Italy, Germany and Switzerland in search of places whose climate should have a favorable effect on his migraines and stomach ailments. From the age of 45 (1889) he suffered from a mental illness that made him incapable of work and business . As a result, he no longer consciously experienced his fame, which began quickly in the early 1890s. He spent the rest of his life in the care of his mother, then his sister, and died in 1900 at the age of 55.

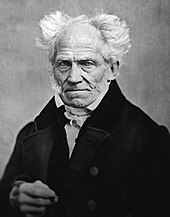

The young Nietzsche was particularly impressed by Schopenhauer's philosophy . He later turned away from its pessimism and placed a radical affirmation of life at the center of his philosophy. His work contains harsh criticisms of morality , religion , philosophy , science, and forms of art . In his eyes, contemporary culture was weaker than that of ancient Greece . Recurring targets of Nietzsche's attacks are above all Christian morality as well as Christian and Platonist metaphysics . He questioned the value of truth in general and thus paved the way for postmodern philosophical approaches. Nietzsche's concepts of the “ superman ”, the “ will to power ” or the “ eternal return ” still give rise to interpretations and discussions.

Nietzsche's thinking worked far beyond philosophy and is still subject to a wide variety of interpretations and evaluations. Nietzsche did not create a systematic philosophy. He often chose aphorism as the form of expression for his thoughts. His prose, his poems and the pathetic-lyrical style of Also sprach Zarathustra earned him recognition as a writer.

Life

Youth (1844–1869)

Friedrich Nietzsche was born on October 15, 1844 in Röcken , a village near Lützen in the Merseburg district in the Prussian province of Saxony (today Saxony-Anhalt ). His parents were the Lutheran pastor Carl Ludwig Nietzsche and his wife Franziska . The Nietzsche family has been documented as Protestant in Saxony since the Reformation in the 16th century. There was a high proportion of Protestant pastors in the families of both parents. His father gave him his first name in honor of the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV , on whose 49th birthday he was born. Nietzsche himself claimed in his later years that he was descended from the paternal line of Polish nobles , but this could not be confirmed.

The sister Elisabeth was born in 1846. After the death of their father in 1849 and their younger brother Ludwig Joseph (1848–1850), the family moved to Naumburg . Bernhard Dächsel , who later became the judiciary , was formally appointed guardian of the siblings Friedrich and Elisabeth.

From 1850 to 1856 Nietzsche lived in the “Naumburg women's household”, that is, together with his mother, sister, grandmother, two unmarried aunts on his father's side and the maid. Only the legacy of her grandmother, who died in 1856, allowed the mother to rent her own apartment for herself and her children. The young Nietzsche first attended the general boys' school, but felt so isolated there that he was sent to a private school, where he made friends with Gustav Krug and Wilhelm Pinder, both of whom came from respected families. From 1854 he attended the Domgymnasium Naumburg and was already noticed there due to his special musical and linguistic talent. In 1857 Pastor Gustav Adolf Oßwald, a close friend of his father, prepared him for the entrance exam in Schulpforta in church divisions . On October 5, 1858, Nietzsche was admitted to the Pforta State School as a scholarship holder , where he met Paul Deussen and Carl Freiherr von Gersdorff as permanent friends . He did very well at school, and in his spare time he wrote and composed. In Schulpforta his own idea of antiquity developed for the first time and, as a result, a distance to the petty bourgeois Christian world of his family. During this time Nietzsche met the older, once politically committed poet Ernst Ortlepp , whose personality impressed the fatherless boy. Teachers particularly valued by Nietzsche, with whom he remained in contact after his school days, were Wilhelm Corssen , the later rector Diederich Volkmann and Max Heinze , who was appointed as his guardian in 1897 when Nietzsche was incapacitated . Corssen had also advocated that Nietzsche, despite a poor grade in mathematics, received his Abitur by referring to his special talent in the ancient languages and German.

Together with his friends Pinder and Krug, Nietzsche met from 1860 on the castle ruins of Schönburg , where he discussed literature, philosophy, music and language with them. With you he founded the artistic-literary association "Germania". The founding ceremony took place on July 25, 1860: “… the three sixteen-year-old club members made their national oath at Naumburg red wine (the 75 pfennig bottle). Poems, compositions, and treatises had to be delivered regularly. They wanted to discuss it together. ”The meetings took place every quarter. Lectures were given on them. There was a communal fund from which books were obtained. During this time Nietzsche developed his passion for Richard Wagner's music . Nietzsche's early works, which were created against the backdrop of the Schönburger Germania, include the synodal lectures , Childhood of the Nations , Fate and History, and On the Demonic in Music . Germania was dissolved in 1863 after Pinder and Krug lost their interest in it.

In the winter semester of 1864/65 Nietzsche began studying classical philology and Protestant theology at the University of Bonn, among others with Wilhelm Ludwig Krafft . Together with Deussen, he became a member of the Frankonia fraternity in Bonn . He voluntarily denied a scale length from which he retained a tear on the bridge of his nose. After a year he left the fraternity because he disliked the social life. In addition to his studies, he immersed himself in the works of the Young Hegelians , including The Life of Jesus by David Friedrich Strauss , The Essence of Christianity by Ludwig Feuerbach and Bruno Bauer's criticisms of the Gospels. These encouraged him (to the great disappointment of his mother) in the decision to drop out of theology studies after one semester.

Nietzsche now wanted to concentrate entirely on classical philology, but was dissatisfied with his situation in Bonn. Therefore, he took the change of philology professor Friedrich Ritschl to Leipzig (as a result of the Bonn philologist dispute ) as an opportunity to move to Leipzig together with his friend Gersdorff. In the following years Nietzsche was to become Ritschl's philological model student, although he was still inclined to his competitor Otto Jahn in Bonn . Ritschl was at times a father figure for Nietzsche, before Richard Wagner (see below) later took this position.

In October 1865, shortly before Nietzsche began studying in Leipzig, he spent two weeks in Berlin with the family of his college friend Hermann Mushacke. In the 1840s, his father had belonged to a debating group around Bruno Bauer and Max Stirner . It is obvious that Nietzsche was confronted during this visit with Stirner's book The Single and His Property , published in 1845, but it cannot be proven. In any case, immediately afterwards Nietzsche turned to a philosopher who was very far removed from Stirner and Young Hegelianism: Arthur Schopenhauer . Another philosopher he discovered for himself during his time in Leipzig was Friedrich Albert Lange , whose history of materialism appeared in 1866. Primarily, however, Nietzsche initially continued his philological studies. During this time he made a close friendship with his fellow student Erwin Rohde . Together with this he participated in the establishment of the Classical Philological Association at the University of Leipzig in 1866.

In the so-called German War between Prussia and Austria, during which Leipzig was also occupied by Prussia, he was still able to avoid his military conscription, Nietzsche was now (1867) committed as a one-year volunteer with the Prussian artillery in Naumburg . When he was incapacitated after a serious riding accident in March 1868, he used the time of his cure for further philological work, which he continued in his last year of study. His first meeting with Richard Wagner in 1868 was of great importance .

Professor at the University of Basel (1869–1879)

On the recommendation of Friedrich Ritschl and the instigation of Wilhelm Vischer-Bilfinger , Nietzsche was appointed extraordinary professor of classical philology at the University of Basel in 1869, even before he had received his doctorate ( honoris causa ) and completed his habilitation . His job also included teaching at the Basel grammar school on Münsterplatz ( pedagogy ). As his most important finding in the field of philology, he saw the discovery that the ancient metric , in contrast to the modern, accentuating metric, was based exclusively on the length of syllables ( quantifying principle ).

At his own request, Nietzsche was released from his Prussian citizenship after moving to Basel and remained stateless for the rest of his life. However, he served as a medic on the German side for a short time in the Franco-German War . During this time he contracted severe dysentery and diphtheria , the convalescence of which was long-lasting. He perceived the founding of the German Empire and the subsequent era of Otto von Bismarck from the outside and with fundamental skepticism.

Because of his poor health, Nietzsche was forced to take a leave of absence for the remainder of the winter semester 1875/1876, which would soon lead to the termination of his teaching activity. The friendship with his colleague Franz Overbeck , an atheist theology professor, began in Basel in 1870, which lasted until the time of Nietzsche's mental derangement . Nietzsche also valued his older colleague Jacob Burckhardt , who, however, politely but definitely kept his distance from him.

Nietzsche had already met Richard Wagner and his future wife Cosima in Leipzig in 1868 . He adored both of them deeply and since the beginning of his time in Basel was a frequent guest in the house of the "Master" in Tribschen near Lucerne . Although he took him into his closest circle at times, he valued him above all as a propagandist for the establishment of the Bayreuth Festival Hall .

In 1872 Nietzsche published his first major work, The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music , an investigation into the origin of tragedy , in which he replaced the exact philological method with philosophical speculation. He developed his art psychology in it by trying to explain the Greek tragedy from the pair of terms Apollonian-Dionysian. The text was rejected by most of his colleagues in classical philology, including Ritschl, and passed over in silence. Through Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff's polemic Zukunftsphilologie! There was still a brief public controversy in which Rohde, now a professor in Kiel, and even Wagner intervened on Nietzsche's side; but Nietzsche became even more aware of his isolation in philology, which is why he had applied for Gustav Teichmüller's professorship in Basel in early 1871 . But this was filled with Rudolf Eucken . In 1873 Nietzsche met Bertha Rohr (1848–1940) in Flims and fell in love.

The four Untimely Considerations (1873–1876), in which he exercised a cultural criticism influenced by Schopenhauer and Wagner , did not find the desired response either. In the meantime Nietzsche had got to know Malwida von Meysenbug and Hans von Bülow in the Wagner circle , and the friendship with Paul Rée , whose influence dissuaded him from the cultural pessimism of his first writings, began. Nietzsche took his disappointment at the first Bayreuth Festival in 1876, where he was repelled by the banality of the drama and the lack of sophistication of the audience, as an opportunity to distance himself from Wagner. His previous passion turned into rejection and ultimately radical opposition.

The same process took place with Schopenhauer. On December 6, Nietzsche began to read Philipp Mainlander's 200-page critique of Schopenhauer's philosophy - a few days later he wrote that he had broken with Schopenhauer. With the publication of Menschliches, Allzumenschliches (1878), the alienation from Wagner and from Schopenhauer's philosophy became apparent. The friendships with Deussen and Rohde had also cooled noticeably. During this time Nietzsche made several unsuccessful attempts to find a young and wealthy wife for himself, in which he was supported above all by the maternal patroness Malwida von Meysenbug. In addition, the diseases that had occurred since his childhood ( migraines and stomach disorders as well as severe myopia , which ultimately led to practically blindness) increased and forced him to take longer and longer vacations from teaching. In 1879 he finally had to take early retirement as a result.

Free philosopher (1879–1889)

Driven by his illnesses in the constant search for optimal climatic conditions for him, he now traveled a lot and lived as a freelance author in various places until 1889. He lived mainly from the pension granted to him; in addition, he occasionally received gifts from friends. In summer he stayed mostly in Sils-Maria , in winter mainly in Italy ( Genoa , Rapallo , Turin ) and in Nice . Every now and then he visited the family in Naumburg, whereupon there were several quarrels and reconciliations with his sister. His former student Peter Gast ( formerly Heinrich Köselitz) temporarily became a kind of private secretary. Köselitz and Overbeck were Nietzsche's most constant confidants.

From the Wagner circle, Meysenbug in particular was retained as a maternal patroness. He also kept in contact with the music critic Carl Fuchs and initially with Paul Rée. At the beginning of the 1880s, Dawn and The Happy Science were other works in the aphoristic style of Menschliches, Allzumenschliches .

In 1882 he met Lou von Salomé through the mediation of Meysenbug and Rée in Rome . Nietzsche quickly made far-reaching plans for the "Trinity" with Rée and Salomé. The approach to the young woman culminated in a stay of several weeks in Tautenburg , with Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth as chaperone . Despite all the appreciation, Nietzsche saw Salomé less as an equal partner than as a gifted student. He fell in love with her, asked for her hand through their mutual friend Rée, but Salomé refused. Due to Elisabeth's intrigues, among other things, the relationship with Rée and Salomé broke up in the winter of 1882/1883. Nietzsche, who was plagued by thoughts of suicide in the face of new episodes of illness and his now almost complete isolation - he had fallen out with his mother and sister because of Salomé - fled to Rapallo, where he wrote the first part of Also Spoke Zarathustra on paper in just ten days .

He developed the thoughts for the third part during his stay in the mountain village of Èze near Nice. A street and a plaque commemorate Nietzsche's days in Èze.

Even after his break with Wagner and the philosophy of Schopenhauer he had only a few friends, the completely new style in Zarathustra met with incomprehension even in the closest circle of friends, which was at best masked by courtesy. Nietzsche was well aware of this and practically cultivated his loneliness, even though he often complained about it. He gave up the briefly cherished plan to go public as a poet. In addition, he was plagued by money worries because his books were hardly bought. He published the fourth part of Zarathustra in 1885 only as a private print with an edition of 40 copies, which were intended as a gift for “those who did a lot for him” and of which Nietzsche only gave seven away.

In 1886 he had Beyond Good and Evil printed at his own expense. With this book and the second editions of Birth , Human , Dawn and Happy Science published in 1886/87 , he saw his work as finished for the time being and hoped that a readership would soon develop. Indeed, interest in Nietzsche increased, albeit very slowly and hardly noticed by himself.

Nietzsche's new acquaintances during these years were Meta von Salis and Carl Spitteler , and a meeting with Gottfried Keller had taken place. In 1886 his sister, now married to the anti-Semite Bernhard Förster , left for Paraguay to found the “Germanic” colony Nueva Germania - a project that Nietzsche found ridiculous. The sequence of quarrels and reconciliation continued in correspondence, but the siblings were only to meet again personally after Friedrich's collapse.

Nietzsche continued to struggle with recurring painful attacks that made constant work impossible. In 1887 he wrote in a short time the pamphlet on the Genealogy of Morals . He exchanged letters with Hippolyte Taine , then also with Georg Brandes , who gave the first lectures on Nietzsche's philosophy in Copenhagen in early 1888.

In the same year Nietzsche wrote five books, some of them from extensive notes, for the temporarily planned work The Will to Power . His health had temporarily improved, and in the summer he was in real high spirits. His writings and letters from the autumn of 1888, however, suggest that he was already beginning to be megalomaniac . The reactions to his writings, especially to the polemic Der Fall Wagner from spring, were grossly overrated by him. On his 44th birthday, after completing the Twilight of the Idols and the initially held back Antichrist , he decided to write the autobiography Ecce homo . An exchange of letters with August Strindberg began in December . Nietzsche believed he was on the verge of an international breakthrough and tried to buy back his old writings from the first publisher. He planned translations into the most important European languages. He also intended to publish the compilation Nietzsche contra Wagner and the poems Dionysus-Dithyramben .

In mental derangement (1889–1900)

On January 3, 1889, he suffered a mental breakdown in Turin. Small documents, so-called "delusional notes", which he sent to close friends, but also to Cosima Wagner and Jacob Burckhardt and even Umberto I of Italy, were marked by a mental illness. The cause of the collapse has been controversial since then. An important question is whether intermittent symptoms appeared and stylistically reflected before this collapse, or whether the collapse occurred abruptly and should be viewed in isolation from previous illnesses such as migraines and asthenopia with high-grade myopia . An extensive and source-critical medical historical research in original findings speaks more for the latter thesis or for the fact that Nietzsche's collapse can best be explained with the quaternary stage of syphilis (or neurolues ).

Overbeck, alarmed by the delusional notes sent to Burckhardt and himself, first brought Nietzsche to the Friedmatt insane asylum in Basel, which Ludwig Wille directed . From there, the mentally deranged man was brought by his mother to the Psychiatric University Clinic in Jena under the direction of Otto Binswanger . An attempt at healing by Julius Langbehn , who had made contact with his mother on his own initiative , failed. In 1890 his mother was finally allowed to take him in at the Nietzsche House in Naumburg . At this time he could occasionally have short conversations, bring up scraps of memory and put greetings dictated by his mother under a few letters, but quickly and suddenly he fell into delusions or apathy and did not recognize old friends either.

Overbeck and Köselitz initially discussed the further procedure with the partially unprinted works. The latter began a first complete edition. At the same time, the first wave of Nietzsche reception began.

Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche returned from Paraguay after her husband's suicide in 1893, had the already printed volumes of the Köselitz edition crumbled , founded the Nietzsche archive and gradually took over control of both the elderly mother and his brother in need of care Estate and the publication of his works. She fell out with Overbeck, while she was able to win Köselitz for another collaboration.

Nietzsche himself, whose decline continued, was no longer aware of any of this. After his mother's death in 1897, after his sister had sold the house in Naumburg, he lived in the Villa Silberblick in Weimar, where Elisabeth looked after him. She granted selected visitors - such as Rudolf Steiner - the privilege of being admitted to the demented philosopher. The Jenaer Volksblatt reported , citing a Naumburg newspaper:

- “His way of life goes by the doctor's prescription, which has regulated his food and service. Otherwise he sits there, deeply absorbed in himself; only when street or children's noise reaches his ear does he utter incomprehensible sounds, but calms down again when one reads to him without, of course, understanding what he has read. His appearance is by no means unhealthy, it is just a bit difficult to dress and undress him because lately a certain awkwardness of the limbs has become noticeable. "

Another detailed description of Nietzsche, who slept in the night, comes from Steiner. After several strokes , which are also compatible with a diagnosis of neurolues (see above), Nietzsche was partially paralyzed and could neither stand nor speak. On August 25, 1900, at the age of 55, he died of pneumonia and another stroke in Weimar. He was buried in the family grave of the Röcken village church.

Thought and work

Nietzsche began his work as a philologist, but increasingly saw himself as a philosopher or a " free thinker ". He is considered a master of the aphoristic short form and the rousing prose style. The works are sometimes provided with a framework, foreword and afterword, poems and a “prelude”. Some interpreters consider even the apparently poorly structured books of aphorisms to be cleverly “composed”.

More than almost any other thinker, Nietzsche chose freedom of method and consideration. A definitive classification of his philosophy in a particular discipline is therefore difficult. Nietzsche's approach to the problems of philosophy is partly that of the artist, partly that of the scientist, and partly that of the philosopher. Many parts of his work can also be described as psychological , although this term only got its current meaning later. Many Deuters see a close connection between his life and his intellectual work, so that much more research and writing about Nietzsche's life and personality than is the case with other philosophers.

Overview of the work

Nietzsche's thought and work are often divided into specific periods. The following breakdown goes back to Nietzsche himself and has been used in a similar form by almost all interpreters since the Nietzsche book Lou Andreas-Salomés (1894).

- The Wagnerian-Schopenhauerian period (1872–1876), which is primarily characterized by these two men and shows romantic influences. It includes the works:

- The birth of tragedy from the spirit of music

-

Untimely considerations in four parts:

- David Strauss, the confessor and the writer

- The benefits and disadvantages of history for life

- Schopenhauer as an educator

- Richard Wagner in Bayreuth

- The “free-spirited” time (1876–1882). Nietzsche is increasingly detaching himself from Wagner's personal influence and from Schopenhauer's philosophical influence. Especially at the beginning of this period, scientific-empirical knowledge is in the foreground. This is why this phase in Nietzsche's work is often referred to as " positivistic ". In the place of the earlier related treatises, there are now collections of aphorisms , which among other things reflect the influence of the French moralists, whom Nietzsche valued :

- Human, All Too Human (with two sequels)

- Dawn. Thoughts on the moral prejudice

- The happy science .

- The central work Also sprach Zarathustra (1883–1885), in which new teachings are formulated in symbolic-poetic language. Also spoke Zarathustra and the late writings are often combined.

- The late works (1886–1888), in which the previous approaches are further elaborated and increasingly brought into polemical sharpness. In addition to aphorisms and sentences, there are now longer treatises. This period includes:

- Beyond Good and Evil

- On the genealogy of morals

- The case of Wagner and Nietzsche versus Wagner

- Twilight of the Idols or How to Philosophize with the Hammer

- The antichrist

- Ecce homo ( autobiography , can be assigned to the same group).

There are, however, some overlaps and breaks in this scheme. Nietzsche added a self-critical foreword and a fifth book to the second editions of The Birth of Tragedy and the Happy Science of 1887. Also significant is the book On Truth and Lies in the Extra-Moral Sense , published in 1896 in the summer of 1873, in which Nietzsche anticipated many of his later thoughts. Nietzsche deals with some topics - such as the relationship between art and science - in all periods, albeit from different perspectives and with correspondingly different answers.

In addition to his philosophical reflections, Nietzsche published poems in which his philosophical thoughts were expressed sometimes in a cheerful, sometimes dark and melancholy manner. They are related to the prose works: The Idylls from Messina (1882) were included in the second edition of the Happy Science , while some of the Dionysus dithyrambs (1888/89) are revisions of pieces from Also Spoke Zarathustra .

The importance of Nietzsche's estate was controversial for a long time , the reception of which was made more difficult by the questionable publication by the Nietzsche archive (see Nietzsche edition ). Karl Schlechta , on the one hand, took extreme positions here , who at least found nothing in the estate published by the archive that was not to be found in Nietzsche's published works; and on the other hand, for example, Alfred Baeumler and Martin Heidegger , who saw Nietzsche's published work only as a “vestibule” while the “actual philosophy” is in the estate. In the meantime, there is a middle position that understands the estate as a supplement to the published works and sees it as a means of better understanding Nietzsche's path of thought and developments.

Nietzsche's thinking has been interpreted in many different ways. It contains breaks, different levels and fictional standpoints of lyrical persons (“A forger is someone who interprets Nietzsche by using quotations from him. […] Every metal can be found in this thinker's mine: Nietzsche said everything and the opposite of everything . ", Giorgio Colli ). Canonical rendering is very difficult.

The question of whether Nietzsche's extensive lack of a system was intended, thus expressing his worldview, was discussed in detail at the reception. It has been largely affirmed since the second half of the 20th century. Compare below the section Criticism of Religion, Metaphysics and Epistemology .

Criticism of morality

One of the most important objects of Nietzsche's criticism at least since the human, all-too-human is morality in general and Christian morality in particular. Nietzsche accuses previous philosophy and science of uncritically adopting prevailing moral concepts; Truly free and enlightened thinking, on the other hand, as the title of a book says, has to place beyond good and evil . All occidental philosophers since Plato , especially Kant , have failed to do this . Nietzsche often does not examine value judgments for their supposed validity, but rather describes connections between the creation of values by a thinker or a group of people and their biological-psychological condition. He is therefore concerned with the question of the value of moral systems in general:

" All sciences now have to prepare for the future task of the philosophers: understand this task to mean that the philosopher has to solve the problem of value , that he has to determine the ranking of values ."

This form of criticism on a meta-level is a typical characteristic of Nietzsche's philosophy. Compare: metaethics .

He himself carries out this criticism excessively with the methods of history, culture and linguistics and places special emphasis on the origin and development of moral ways of thinking, for example in On the Genealogy of Morals . Important terms in his moral criticism are:

- Men - and slave morality

- Master's morality is the attitude of those in power who can say yes to themselves and their lives, while they regard others as “bad” (root word: “simple”) disparagingly. Slave morality is the attitude of the "miserable [...], poor, powerless, low [...], suffering, deprived, sick, ugly" who first rated their counterparts - the rulers, the happy, those who said yes - as "bad" and themselves then identified as their "good" opposite. Above all, it was the morality of Christianity that produced such slave morality in part itself, but in any case favored it and thereby made it the dominant morality.

- resentment

- This is the basic feeling of slave morality. Out of resentment, envy and weakness, the “failures” create an imaginary world (for example the Christian afterlife) in which they themselves could be the rulers and live out their hatred of the “noble”.

- Compassion and compassion

- While the pessimist Schopenhauer placed pity at the center of his ethics in order to implement his philosophy of negation of life, Nietzsche turned the thesis of pity on after his break with Schopenhauer's philosophy: Because life is to be affirmed, pity applies - as a means to it Negation - as a danger. It increases suffering in the world and opposes the creative will, which must always destroy and overcome - others or even oneself. Active shared joy (as opposed to passive compassion) or a fundamental affirmation of life ( amor fati ) are the higher and more important Values.

Such lines of thought are bundled by Nietzsche into an increasingly radical criticism of Christianity, for example in Der Antichrist . This is not only nihilistic in the sense that it denies the sensually perceptible world any value - a criticism that Nietzsche understands also applies to Buddhism - but, in contrast to Buddhism, also born out of resentment. Christianity hindered every higher kind of person and every higher culture and science. Carl Albrecht Bernoulli emphasizes that Nietzsche's anti-Christianity is primarily anti-Semitic and that, where he speaks honestly, “his judgments about the Jews leave all anti-Semitism far behind.” In later writings Nietzsche increased the criticism of all existing ones Norms and values: He sees after-effects of Christian doctrine at work in bourgeois morality as well as in socialism and anarchism . All modernity suffers from decadence . In contrast, a “revaluation of all values” is now necessary. How exactly the new values would have looked, however, is not clearly clear from Nietzsche's work. This question and its connection with the aspects of the Dionysian , the will to power , the superman and the Eternal Coming are still discussed today. Nietzsche's most extreme statements about the energy of greatness and anti-humanism can be found in a legacy fragment from 1884: “... -to gain that immense energy of greatness in order to develop future people through breeding and on the other hand through the annihilation of millions of failures shape and not perish from the suffering that one creates and whose equal has never been there! "

“God is dead” - European nihilism

The keyword “God is dead” is often associated with the idea that Nietzsche conjured up or wished for God's death. In fact, Nietzsche saw himself more as an observer. He analyzed his time, especially the (Christian) civilization that, in his opinion, had meanwhile become ailing. He was also not the first to ask the question of “God's death”. The young Hegel already expressed this thought and spoke of the “infinite pain” as a feeling “on which the religion of the new age is based - the feeling: God himself is dead”.

The most important and most noticed passage on this topic is the aphorism 125 from the gay science with the title “The great person”. The stylistically dense aphorism contains allusions to classical works of philosophy and tragedy. This text makes the death of God appear as a threatening event. The speaker in it dreads the terrible vision that the civilized world has largely destroyed its previous spiritual foundation:

"Where is God going? he cried, I will tell you! We killed him - you and me! We are all his killers! But how did we do this? How could we drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the whole horizon? What did we do when we untied this earth from its sun? Where is it going now? Where are we going Away from all the suns? Don't we keep falling? And backwards, sideways, forwards, in all directions? Is there still an above and a below? Are we not wandering through an infinite nothingness? Doesn't the empty space breath on us? Hasn't it gotten colder? Doesn't night come and more night? [...] God is dead! God remains dead! And we killed him! How do we console ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? "

This incomprehensible process will take a long time, precisely because of its large dimensions, to be recognized in its scope: “I'm coming too early, he said then, I'm not yet time. This tremendous event is still on the way and is traveling - it has not yet reached the ears of people. "And the question is:" Isn't the size of this deed [to have killed God] too great for us? Do we not have to become gods ourselves just to appear worthy of them? ”Among other things, from this thought the idea of the“ superman ”appears later, as it is presented above all in Zarathustra :“ All gods are dead: now we want that the superman lives. "

The word of God's death is also found in Aphorisms 108 and 343 of the Happy Science , and it also appears several times in Also Spoke Zarathustra . After that, Nietzsche no longer used it, but continued to deal intensively with the subject. Noteworthy here is, for example, the abandoned fragment The European Nihilism (dated June 10, 1887), in which it says: "'God' is a far too extreme hypothesis ."

Nietzsche comes to the conclusion that several powerful currents, above all the emergence of the natural sciences and history, contributed to making the Christian worldview unbelievable and thus to bring down Christian civilization. By criticizing existing morality, as Nietzsche himself pursues, morality becomes hollow and implausible and finally collapses. With this radicalized criticism, Nietzsche stands on the one hand in the tradition of French moralists, such as Montaigne or La Rochefoucauld , who criticize the morality of their time in order to arrive at a better one; on the other hand, he emphasizes several times that he is fighting not only the hypocrisy of morals, but the ruling “morals” themselves - essentially always Christian ones. In this sense, he describes himself as an “immoralist”.

Today there is widespread agreement that Nietzsche did not see himself as a proponent of nihilism, but saw it as a possibility in [post] Christian morality, perhaps also as a historical necessity. These passages say little about Nietzsche's atheism in the sense of non-belief in a metaphysical God. (See the section Critique of Religion, Metaphysics, and Epistemology .)

Art and science

The pair of terms “ Apollonian-Dionysian ” was already used by Schelling , but only found its way into the philosophy of art through Nietzsche. With the names of the Greek gods Apollon and Dionysus , Nietzsche in his early work The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music refers to two opposing principles of aesthetics . Accordingly, the dream, the beautiful appearance, the brightness, the vision, the sublimity are Apollonian; Dionysian is the intoxication , the cruel disinhibition, the breaking out of a dark elemental force. According to Nietzsche, in the Attic tragedy the union of these forces succeeded. The “primordial one” reveals itself to the poet in the form of Dionysian music and is translated into images by means of Apollonian dreams. On the stage the tragedy was born by the choir , which gives space to the Dionysian. As an Apollonian element, the dialogue in the foreground and the tragic hero are added.

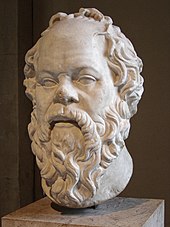

The Greek tragedy perished through Euripides and the influence of Socratism. As a result, above all the Dionysian, but also the Apollonian, were driven out of the tragedy, and the tragedy itself had sunk to a merely dramatized epic. Art had placed itself in the service of knowledge and Socratic wisdom and had become pure imitation. Only in Richard Wagner's musical drama did the opposing principles succeed again.

In later writings Nietzsche moves away from this position; in particular, he no longer sees a new beginning in Wagner's works, but rather a sign of decline. He also varied his fundamental aesthetic considerations: In the writings of the “positivist” period, art clearly took a back seat to science. For Nietzsche, “the scientific man is the further development of the artistic” ( human, all-too-human ), even “[d] as life is a means of knowledge” ( joyful science ).

Only after Also Spoke Zarathustra did Nietzsche revert more clearly to his early aesthetic views. In an 1888 notebook it says:

“The art and nothing but the art! She is the great facilitator of life, the great seductress of life, the great stimulant of life. "

In the later writings he also developed the concept of the Dionysian. The deity Dionysus serves to project several important teachings, and Ecce homo closes with the exclamation: “Dionysus against the crucified!” The theme of Dionysus is one of the decisive constants in Nietzsche's life and work, from his birth of tragedy to insanity , where he signs with Dionysus and Cosima Wagner becomes his Ariadne .

Criticism of religion, metaphysics and epistemology

A critique of previous philosophies is connected with the critique of morality. Nietzsche is fundamentally skeptical of metaphysical and religious concepts. The possibility of a metaphysical world is not refutable, but it is none of our business:

“It is true there could be a metaphysical world; the absolute possibility of this can hardly be combated. [...] but everything that [...] has made metaphysical assumptions valuable, terrifying, pleasurable , that which has produced them, is passion, error and self-deception; the very worst methods of knowledge, not the very best, have taught to believe in it. When these methods have been discovered as the foundation of all religions and metaphysics in existence, they have been refuted. Then that possibility still remains; but one cannot do anything with it, let alone let happiness, salvation and life depend on the cobwebs of such a possibility. - For nothing at all could be said about the metaphysical world except an otherness, an inaccessible, incomprehensible otherness; it would be a thing with negative qualities. - Even if the existence of such a world had been proven so well, it would be certain that the most indifferent of all knowledge would be its knowledge [...] "

All metaphysical and religious speculations, on the other hand, can be explained psychologically; above all, they would have served to legitimize certain morals. According to Nietzsche, the respective way of thinking, the philosophies of the philosophers, are to be derived from their physical and mental constitution as well as their individual experiences.

"Indeed, one does well (and wisely) to explain how the most remote metaphysical assertions of a philosopher actually came about, always to ask oneself: What morality is (does he -) aim at ?"

Nietzsche also applies this thesis in his self-analyzes and repeatedly points out that we necessarily always perceive and interpret the world in perspective . The very necessity of expressing oneself in language and thus using subjects and predicates is a prejudice-prone interpretation of what is happening ( about truth and lies in the extra-moral sense ). With this Nietzsche dealt with questions that were partially taken up again by modern philosophy of language .

He honors the skeptics as the only "decent type in the history of philosophy" ( The Antichrist ) and expresses fundamental reservations about any kind of philosophical system. It is dishonest to think that the world can be fitted into an order:

“I distrust all systematics and avoid them. The will to the system is a lack of righteousness. "

In his autobiography Ecce homo he describes his relationship to religion and metaphysics one last time:

“'God', 'Immortality of the soul', 'Salvation', 'Beyond' are all concepts to which I have paid no attention or time, not even as a child - maybe I was never childlike enough? - I do not know atheism as a result, much less as an event: I understand it by instinct. I am too curious, too questionable , too cocky, to put up with a rough answer. God is a rough answer, an undelicacy against us thinkers - basically just a rough prohibition against us: you shouldn't think! "

More thoughts

- genealogy

In Nietzsche's works it can be shown that from a young age he demanded access to the topics of metaphysics, religion and morality, and later also the aesthetic, from a historical-critical point of view. All explanatory models that aim at something transcendent, unconditional, universal are nothing but myths that arose in the history of the development of knowledge on the basis of the knowledge of their time. It is the task of modern science and philosophy to uncover this. In this sense Nietzsche saw himself as an advocate of a radical enlightenment idea. "[...] only after we have corrected the historical way of looking at things that the age of the Enlightenment brought with it in such an essential point, we may the flag of the Enlightenment - the flag with the three names: Petrarch, Erasmus, Voltaire - again carry on. We have made progress out of the reaction. ”He first used the term genealogy in the title of the genealogy of morals . The methodology is explained there in particular in the second treatise in sections 12 to 14. He already described and practiced the underlying method in the Human, All Too Human (Aphorisms 1 and 2), and already in the Second Untimely Consideration he reflected critically the value of the historical, showed its limits, but also its inevitability. For Nietzsche, genealogy does not mean historical research, but a critical explanation of contemporary phenomena on the basis of ( speculative ) theoretical deductions from history. The focus is on a “de-plausibility” of previous narratives in philosophy, theology and cultural-scientific issues through historically based psychological theses. Nietzsche's concept had a great influence on Michel Foucault . Josef Simon equated the method with modern deconstruction .

- Perspectivism

From his criticism of metaphysics, epistemology, moral philosophy and religion, Nietzsche himself developed a pluralistic worldview. By conceiving the world and humans as an organism in constant evolution, in which a multitude of elements struggle to assert themselves in constant opposition to one another, he broke away from traditional substance-based thinking and from any causal-mechanistic and teleological explanations. “All unity is unity only as an organization and interaction: no different from how a human community is a unity: that is, the opposite of atomistic anarchy; thus a rulership structure that means one, but is not one. ”In this organism as a totality, the most diverse forces work in battle against one another; they follow their respective will to power (see below). "Life should be defined as a permanent form of process of ascertaining strength, in which the different struggling in turn grow unevenly." Each organism conducts its struggle from its own perspective.

“In the end, let us not be ungrateful, especially as those who know, to such resolute reversals of the accustomed perspectives and valuations with which the mind has for too long apparently ravaged itself in a malicious and useless manner: to see differently for once, to want to see differently is no small discipline and preparation of the intellect for its former 'objectivity' - the latter is not understood as a 'disinterested intuition' (as which is a non-conception and absurdity), but as the ability to have one's pros and cons in control and to hang and hang up: so that one knows precisely how to make the difference in perspectives and affect interpretations usable for knowledge [...] There is only perspective seeing, only perspective 'knowing'; and the more affects we let speak about a thing, the more eyes, different eyes we know how to commit ourselves to the same thing, the more complete our “concept” of this thing, our “objectivity” will be. But to eliminate the will altogether which hang out affects together and separately, provided that we are able to do this: how? doesn't that mean castrating the intellect? "

The subjective view that leads to perspective now means neither arbitrariness nor relativism. The perspective taken in each case rather leads to the fact that the human being combines the world as it appears to him into an image, an interpretation.

“That the value of the world lies in our interpretation (- that perhaps other interpretations are possible somewhere other than merely human -) that the previous interpretations are perspective estimates, that we can think of in life, that is, in the will to power, to the growth of the world Receiving power, that every elevation of man brings with it the overcoming of narrower interpretations, that every strengthening and expansion of power that has been achieved opens up new perspectives and means believing in new horizons - this goes through my writings. "

- Will to power

The “ will to power ” is firstly a concept that is introduced for the first time in Also Spoke Zarathustra and is mentioned at least in passing in all subsequent books. Its beginnings lie in the psychological analyzes of the human will to power in the dawn . Nietzsche explained it more comprehensively in his posthumous notebooks from around 1885.

Second , it is the title of a work planned by Nietzsche as a revaluation of all values that never came about. Notes on this were mainly used in the works Götzen-Twilight and The Antichrist .

Thirdly , it is the title of an estate compilation by Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche and Peter Gast , which, in the opinion of these editors, should correspond to the “main work” planned under point two.

The interpretation of the concept “will to power” is highly controversial. For Martin Heidegger it was Nietzsche's answer to the metaphysical question about the “ground of all that is”: According to Nietzsche, everything is “will to power” in the sense of an inner, metaphysical principle, just as Schopenhauer's “will (to life)” is . Wolfgang Müller-Lauter took the opposite opinion : According to this, Nietzsche's “will to power” by no means restored metaphysics in the sense of Heidegger - Nietzsche was precisely a critic of all metaphysics - but attempted to give a consistent interpretation of all events which avoid Nietzsche's erroneous assumptions of metaphysical “meaning” as well as an atomistic - materialistic worldview. In order to understand Nietzsche's concept, it would be more appropriate to speak of the (many) "wills to power" that are in constant conflict with one another, conquer and incorporate one another, temporary organizations (for example the human body), but no "whole" because the world is eternal chaos.

Most of the others move between these two interpretations, whereby today's Nietzsche research is much closer to that of Müller-Lauter. In Nietzsche (with his worldview, which is always oriented towards the healthy individual), however, it is precisely the concept of power that predicts newer positive forms of understanding such as those we use for example. B. in Hannah Arendt - here, however, in relation to people in society: the basic possibility of creating something “to do something”.

- Eternal return

Nietzsche's “deepest thought”, which first appeared in The Joyful Science and was highlighted in Also Spoke Zarathustra , which came to him on a hike in the Engadin near Sils-Maria , is the idea that everything that has happened has happened and will recur endlessly. One should therefore live in such a way that one not only endures the perpetual repetition of every moment, but even welcomes it. “But all lust wants eternity - wants deep, deep eternity” is a central sentence in Also Spoke Zarathustra . Amor fati (Latin for "love of fate") is closely related to the "Eternal Coming", for which Nietzsche tried to give scientific justifications despite his only very superficial scientific education . For Nietzsche, this is a formula for designating the highest state that a philosopher can reach, the form of the most elevated affirmation of life.

There is no agreement about the “ eternal return ”, its meaning and position in Nietzsche's thoughts. While some interpreters made it the center of his entire thinking, others saw it merely as a fixed idea and a disturbing “foreign body” in Nietzsche's teachings.

- Superman

Nietzsche does not believe in any progress in human history - or in the world in general. For him, the goal of mankind therefore can not be found on her (time) end, but that in their recurrent highest individuals over people . He sees the human species as a whole only as an attempt, a kind of basic mass, out of which he calls for “creators” who are “hard” and ruthless with others and above all with themselves, in order to create something valuable from humanity and themselves Creating artwork. As a negative counterpart to Superman is in Zarathustra Thus Spoke the last man presented. This stands for the weak endeavor to assimilate people with one another, for a long and "happy" life as risk-free as possible without hardship and conflicts. The prefix “Über” in the word creation “Übermensch” can not only stand for a higher level relative to another, but can also be understood in the sense of “over”, so it can express a movement. The superman is therefore not necessarily to be seen as a master man over the last man. A purely political interpretation is considered misleading in today's Nietzsche research. The “will to power”, which should be concretized in the superman, is therefore not the will to rule over others, but is to be understood as the will to be able, to enrich oneself, to overcome oneself.

Influences

Nietzsche's first practical experience with Christianity resulted from his youth in the parsonage and in the petty-bourgeois, pious “women's household”. Very soon he developed a critical point of view and read writings by Ludwig Feuerbach and David Friedrich Strauss . When exactly this alienation from the family began and what influence it had on Nietzsche's further path of thought and life is the subject of an ongoing debate in Nietzsche research.

Nietzsche's early death may also have influenced Nietzsche; in any case, he himself often pointed out its importance for him. It should be noted that he hardly knew him himself, but rather made an idealized picture of his father from family stories. As a friendly and popular, on the other hand physically weak and sick country pastor, he appears again and again in Nietzsche's self-analyzes.

Even in his youth Nietzsche was impressed by the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Lord Byron , and he chose Holderlin , who was taboo at the time , as his favorite poet. He also read Machiavelli's work The Prince privately when he was at school.

How strong the influence of the poet Ernst Ortlepp or the ideas of Max Stirner or the whole of Young Hegelianism on Nietzsche were is controversial. The influence of Ortlepp has been particularly emphasized by Hermann Josef Schmidt . The influence of Stirner on Nietzsche has been debated since the 1890s. Some interpreters saw this as a fleeting acknowledgment, others, above all Eduard von Hartmann , made a plagiarism charge . Bernd A. Laska advocates the outsider thesis that Nietzsche went through an "initial crisis" as a result of the encounter with the work of Stirner, which was conveyed to him by the Young Hegelian Eduard Mushacke, which led him to Schopenhauer.

While studying philology with Ritschl , Nietzsche learned not only the classical works himself, but also mainly philological and scientific methods. This is likely to have influenced the methodology of his writings on the one hand, which is particularly evident in the genealogy of morality , and on the other hand also his image of strict science as arduous work for mediocre minds. His rather negative attitude towards science at universities was undoubtedly based on his own experience both as a student and as a professor.

At the university Nietzsche tried to win talks with Jacob Burckhardt, whom he valued , read some of his books and listened to his colleague's lectures. During his time in Basel, he had a lively exchange of ideas with his friend Franz Overbeck , and Overbeck later helped him with questions of theology and church history .

Nietzsche made use of works by well-known writers such as Stendhal , Tolstoy and Dostojewski for his own thinking, as well as those by authors such as William Edward Hartpole Lecky or scholars such as Julius Wellhausen . For his views on modern decadence, he read and evaluated George Sand , Gustave Flaubert and the Goncourt brothers .

Finally, Nietzsche's interest in the sciences from physics (particularly Roger Joseph Boscovich's system) to economics can be demonstrated. In the preface to the genealogy of morals , Nietzsche relied heavily on the special importance of the critical examination of the book The Origin of Moral Sensations (1877) by Paul Rée. Nietzsche relied heavily on his knowledge of physiology , also in the critical examination of Darwinism on the work The Struggle of the Parts in the Organism. A contribution to the completion of the mechanical expediency theory of the anatomist Wilhelm Roux . He also believed that his illnesses gave him a better knowledge of medicine , physiology and dietetics than some of his doctors.

Wagner and Schopenhauer

From the mid-1860s, the works of Arthur Schopenhauer had a great influence on Nietzsche; At the same time, Nietzsche admired not so much the core of Schopenhauer's teaching as the person and the "type" Schopenhauer, that is, in his mind the truth-seeking and "out of date" philosophers. Another essential inspiration was the person and the music of Richard Wagner . Richard Wagner's writings in Bayreuth (Fourth Untimely Contemplation ) and above all the Birth of Tragedy celebrate his musical drama as overcoming nihilism as well as flat rationalism . This veneration turned into enmity at the latest in 1879 after Wagner's supposed turn to Christianity (in Parsifal ). Nietzsche justified his radical change of heart later in Der Fall Wagner and in Nietzsche contra Wagner . The fact that Nietzsche occupied himself almost obsessively with the former “master” long after Wagner's death in 1883 has attracted some attention: There have been many studies of the complicated relationship between Nietzsche and Wagner (as well as Wagner's wife Cosima ) with partly different results. In addition to the ideological and art-philosophical differences mentioned by Nietzsche, personal reasons certainly also played a role in Nietzsche's "falling away" from Wagner.

He now also saw Schopenhauer more critically and believed that he recognized a phenomenon typical of the time and therefore a backward-looking phenomenon in his pessimism and nihilism. Of course, in 1887 he still found words of praise for Schopenhauer, who "as a philosopher was the first admitted and indomitable atheist that we Germans had":

“[Now] the Schopenhauerian question comes to us in a terrible way : does existence have any meaning at all? - that question that will take a few centuries to be heard completely and in depth. What Schopenhauer himself answered to this question was - please forgive me - something hasty, youthful, just a severance payment, a stopping and getting stuck in the Christian-ascetic moral perspective, which, with belief in God, is belief was canceled ... But he's the question asked . "

Nietzsche's Reception of Other Philosophies

Nietzsche did not systematically acquire his knowledge of philosophy and the history of philosophy from the sources. He took it primarily from secondary literature : above all from Friedrich Albert Lange's History of Materialism and Kuno Fischer's History of Modern Philosophy to later authors. Plato and Aristotle were known to him from philology and were also the subject of some of his philological lectures, but the latter in particular he knew only incompletely. He dealt intensively with the pre-Socratics at the beginning of the 1870s , and later came back to Heraclitus in particular .

For Spinoza's ethics , which Nietzsche suggested at times, Fischer's work was his main source. He also got to know Kant through Fischer (and Schopenhauer, see above); in the original he probably only read the Critique of Judgment . For some time he accepted Schopenhauer's harsh criticism of German idealism around Hegel . Later he ignored the direction. It is noteworthy that Nietzsche did not make any noteworthy statements about the Young Hegelians ( Feuerbach , Bauer and Stirner ), although he saw them as thinkers of a “lively time”, also none about Karl Marx , although he made various statements about political socialism .

Other sources received by Nietzsche were the French moralists such as La Rochefoucauld , Montaigne , Vauvenargues , Chamfort , Voltaire and Stendhal . Reading Blaise Pascal gave him some new insights into Christianity.

Now and then Nietzsche argued polemically with the philosophers Eugen Dühring , Eduard von Hartmann and Herbert Spencer , who were popular at the time . He obtained his knowledge of the teachings of Charles Darwin primarily from the latter and the German representatives of the evolution theory around Ernst Haeckel .

The intensive research of sources over the last few decades has identified numerous references in Nietzsche's works, including to his contemporaries Afrikan Spir and Gustav Gerber , whose linguistic and epistemological theory show surprising similarities with Nietzsche's.

Occasionally, Nietzsche research has pointed out that Nietzsche's criticism of other philosophies and doctrines is based on misunderstandings, precisely because he only knew them through distorting secondary literature. This applies in particular to Nietzsche's statements on Kant and the theory of evolution. But this topic is also controversial.

effect

Works and editions

Year numbers in brackets indicate the year of creation, separated by commas the year of first publication.

Philological works

- On the history of the Theognideische Spruchsammlung. 1867.

- De Laertii Diogenis fontibus. 1868/69.

- Homer and Classical Philology. 1869.

- Analecta Laertiana. 1870.

- The Florentine Treatise on Homer and Hesiod. 1870 (see: Certamen Homeri et Hesiodi ).

- The Greek musical drama. 1870 (Critical Study Edition (KSA) I, 513-549)

Philosophy, poetry and autobiography

-

Five prefaces to five unwritten books. 1872 KSA 1:

- I. About the pathos of truth .

- II. Thoughts about the future of our educational institutions.

- III. The Greek state.

- IV. The relationship between Schopenhauer's philosophy and a German culture.

- V. Homer's competition.

- The birth of tragedy from the spirit of music . 1872 KSA 1.

- About truth and lies in a non-moral sense . 1873 KSA 1.

- Philosophy in the tragic age of the Greeks . 1873 KSA 1.

-

Out of time considerations. 1873–1876 KSA 1 and 2.

- David Strauss, the confessor and the writer. 1873.

- The benefits and disadvantages of history for life . 1874.

- Schopenhauer as an educator. 1874.

- Richard Wagner in Bayreuth. 1876.

- Human, All Too Human - A book for free spirits. (with two continuations), 1878–1880 KSA 2

- The Wanderer and His Shadow 1880

- Dawn. Thoughts on the moral prejudice . 1881 KSA 3.

- Idylls from Messina . 1882 KSA 3.

- The happy science ("la gaya scienza"). 1882 KSA 3.

- Thus spoke Zarathustra - a book for everyone and nobody. 1883–1885 KSA 4.

- Beyond good and bad - prelude to a philosophy of the future . 1886 KSA 5.

- On the Genealogy of Morals - A Polemic. 1887 KSA 5.

- The Wagner case - a musicians problem . 1888 KSA 6.

- Dionysus dithyrambs. 1889 KSA 6.

- Twilight of the Idols or How to Philosophize with the Hammer . 1889 KSA 6.

- The Antichrist - curse on Christianity. 1895 KSA 6.

- Nietzsche versus Wagner . 1895 KSA 6.

- Ecce homo - How to become what you are . (1888) 1908 KSA 6.

Poetry (selection)

- Ecce homo (yes, I know where I come from).

- “My luck!” I see the pigeons from San Marco again.

- Solitary (the crows screech and fly to town).

- The mysterious boat (last night when everyone was asleep).

- The drunken song (O man! Pay attention!).

- Venice (I recently stood at the bridge in a brown night).

music

Nietzsche played music and composed numerous smaller pieces since his youth.

Significant are:

- All works for piano solo recorded by Michael Krücker for the label NCA, SACD (Super-Audio-CD), Order No .: 60189, ISBN 978-3-86735-717-3 .

- Manfred Meditation , 1872. On the Manfred by Lord Byron . After Hans von Bülow's devastating criticism, Nietzsche largely gave up composing. mp3 file

- Hymn to friendship , 1874. Audio sample (wav format; 421 kB)

- Prayer to Life , NWV 41, 1882, and Hymn to Life , Choir and Orchestra, 1887: Nietzsche set a poem by Lou von Salomé to music in 1882. Peter Gast reworked this into a composition for mixed choir and orchestra, which was published in 1887 under Nietzsche's name. mp3 file

expenditure

- Total expenditure

- complete, extensively commented editions:

- Works. Critical Complete Edition Sigle : KGW [also: KGA (Verlag)], ed. by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari. Berlin and New York 1967ff.

- Letters. Critical Complete Edition Sigle: KGB , ed. by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari. Berlin and New York 1975-2004.

- Karl Schlechta (Ed.): Friedrich Nietzsche, works in three volumes (with index volume). 8th edition. Hanover / Munich 1966 (cf. Nietzsche edition # The Schlechta edition and criticism of it ).

- Study expenses

- Paperback editions:

- Complete works , critical study edition in 15 volumes Sigle: KSA , ed. by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari. Munich and New York 1980, ISBN 3-423-59065-3 .

- All letters . Critical study edition Sigle: KSB , ed. by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari. Munich and New York 1986, ISBN 3-423-59063-7 .

- Nietzsche Online

- 70 volumes of Editions der Werke (KGW) and Letters (KGB) by Friedrich Nietzsche by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari: over 80 monographs and reference works such as the Nietzsche dictionary and all 38 volumes of Nietzsche studies - a total of over 100,000 book pages at De Gruyter (10 / 2010).

literature

Philosophy bibliography : Friedrich Nietzsche - Additional references to the topic (More bibliographical information can be found in most of the books and titles listed, see also the bibliographies under the web links .)

To the biography

- Charles Andler : Nietzsche, sa vie et sa pensée. 6 volumes. Brossard, Paris 1920–1931, later editions (3 volumes, two combined each) by Gallimard , Paris, ISBN 2-07-020127-9 , ISBN 2-07-020128-7 , ISBN 2-07-020129-5 (detailed Overall representation, basis of reception for many French authors).

- Sabine Appel : Friedrich Nietzsche: Wanderer and free spirit. A biography. Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-61368-5 .

- Raymond J. Benders, Stephan Oettermann : Friedrich Nietzsche: Chronicle in pictures and texts. Hanser, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-446-19877-6 .

- Daniel Blue: The Making of Friedrich Nietzsche: The Quest for Identity, 1844–1869. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2016, ISBN 978-1-107-13486-7 .

- Burkhart Brückner, Robin Pape: Biography of Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche In: Biographical Archive of Psychiatry (BIAPSY) .

- Volker Ebersbach : Nietzsche in Turin. Boldt-Literaturverlag, Winsen / Luhe; Weimar 1994, ISBN 3-928788-11-6 .

- Ivo Frenzel: Friedrich Nietzsche in personal reports and photo documents. 31st edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-499-50634-3 .

- Timo Hoyer : Nietzsche and pedagogy. Work, biography and reception . Königshausen & Neumann 2002, ISBN 3-8260-2418-4 .

- Curt Paul Janz : Friedrich Nietzsche. Biography. 3 volumes, Hanser, Munich 1978/1979, ISBN 3-423-04383-0 (standard work).

- Alfred von Martin : Nietzsche and Burckhardt . Reinhardt, Munich 1941 (4th edition, Erasmus-Verlag, Munich 1947).

- Alice Miller : The unlived life and the work of a philosopher of life: Friedrich Nietzsche. In: Dies .: The avoided key. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-518-02226-1 .

- Christian Niemeyer (Ed.): Nietzsche Lexicon. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-534-20844-9 .

- Henning Ottmann (ed.): Nietzsche manual: Life - work - effect. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2000, ISBN 3-476-01330-8 .

- Sue Prideaux: I am dynamite! A life of Friedrich Nietzsche. Faber & Faber, London 2018, ISBN 978-0-571-33621-0 .

- Translation: I am dynamite. The life of Friedrich Nietzsche. Translated from English by Thomas Pfeiffer and Hans-Peter Remmler. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2020, ISBN 978-3-608-98201-5 .

- Werner Ross : The fearful eagle; Friedrich Nietzsche's life. DVA, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-423-30736-6 , and Der wilde Nietzsche or The return of Dionysus. DVA, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-421-06668-X (two antithetical accentuations of Nietzsche's character from the perspective of a literary scholar).

- Rüdiger Safranski : Nietzsche: biography of his thinking. Hanser, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-446-19938-1 (high philosophical content; also serves as an introduction to Nietzsche's thinking).

- Hermann Josef Schmidt : Nietzsche absconditus or reading traces with Nietzsche. 4 volumes. IBDK, Berlin / Aschaffenburg 1991–1994 (meticulous psychological study of Nietzsche's childhood and adolescence).

- Rudolf Steiner : Friedrich Nietzsche, a fighter against his time in Project Gutenberg ( currently not available to users from Germany ) , Weimar 1895.

- Pia Daniela Volz: Nietzsche in the labyrinth of his illness. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1990, ISBN 3-88479-402-7 (standard work on Nietzsche's medical history).

- Giuliano Campioni: Nietzsche's personal library. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2003.

- Nils Fiebig: Nietzsche and Money - The Banality of the Everyday. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-8260-6669-6 .

- Hans Gutzwiller : Friedrich Nietzsche's teaching activity at the Basler Pedagogy 1869-1876. In: Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde. Volume 50, 1951, pp. 147-220.

To philosophy

- Christian Benne, Claus Zittel (ed.): Nietzsche and the poetry: A compendium. JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2017.

- Manuel Knoll, Barry Stocker (Eds.): Nietzsche as Political Philosopher. Berlin / Boston 2014.

- Claus Zittel: The aesthetic calculation of Friedrich Nietzsche's "Also sprach Zarathustra" (Nietzsche in discussion), Würzburg 2000 (2nd edition 2011).

- Günter Abel : Nietzsche. The dynamic of the will to power and the eternal return. 2nd, expanded edition. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1998, ISBN 3-11-015191-X (attempt to clarify the often misunderstood term).

- Keith Ansell Pearson (Ed.): A Companion to Nietzsche. Blackwell, Oxford / Malden 2006, ISBN 1-4051-1622-6 .

- Volker Caysa , Konstanze Schwarzwald: Nietzsche - Power - Greatness. Nietzsche - philosopher of power or the power of greatness. ; De Gruyter Berlin / New York 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-024572-1 .

- Maudemarie Clark: Nietzsche on Truth and Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1990, ISBN 0-521-34850-1 .

- Gilles Deleuze : Nietzsche and Philosophy. European publishing house, Hamburg 1976, ISBN 3-434-46183-3 (classic of the French Nietzsche reception).

- Jacques Derrida : Spurs. Nietzsche's styles. Corbo e Fiore, Venice 1976 (tries to show that Nietzsche's thinking has no center).

- Elmar Dod: The scariest guest. The philosophy of nihilism. Tectum, Marburg 2013, ISBN 3-8288-3107-9 . The scariest guest will feel at home. The Philosophy of Nihilism - Evidences of the Imagination. Baden - Baden 2019, ISBN 978-3-8288-4185-7 (the two studies develop Nietzsche's concept of nihilism further).

- Günter Figal : Nietzsche. A philosophical introduction. Reclam, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-15-009752-5 .

- Eugen Fink : Nietzsche's Philosophy. Stuttgart 1960.

- Erich Heller : The return of innocence and other essays. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1977.

- Karl Jaspers : Nietzsche. Introduction to understanding his philosophizing. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981 (first edition 1935), ISBN 3-11-008658-1 (Jaspers seeks access to Nietzsche's thinking as a philosopher and as a psychiatrist).

- Walter Arnold Kaufmann : Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist , Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ 1950, 4th edition. 1974; German translation: Nietzsche: Philosopher - Psychologist - Antichrist. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1988, ISBN 3-534-80023-0 (important work on the Anglo-Saxon Nietzsche interpretation).

- Domenico Losurdo : Nietzsche, the aristocratic rebel: intellectual biography and critical balance. 2 volumes. Argument / Inkrit, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-88619-338-7 .

- Mazzino Montinari : Friedrich Nietzsche: An introduction. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1991, ISBN 3-11-012213-8 (by one of the editors of Nietzsche's Complete Critical Edition).

- Wolfgang Müller-Lauter : Nietzsche. His philosophy of opposites and the opposites of his philosophy . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1971.

- Barbara Neymeyr , Andreas Urs Sommer (ed.): Nietzsche as a philosopher of modernity. Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2012. ISBN 978-3-8253-5812-9 .

- Raoul Richter : Friedrich Nietzsche. His life and his work. 4th edition. Meiner, Leipzig 1922 ( digitized version ).

- Wiebrecht Ries : Nietzsche for an introduction. Junius, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-88506-393-X .

- Georg Römpp : Nietzsche made easy. (= UTB . 3718). Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar 2013, ISBN 978-3-8252-3718-9 .

- Hermann Josef Schmidt: Against Nietzsche's further riveting. A pamphlet (= explanations on Nietzsche. Volume 1). Alibri, Aschaffenburg 2000, ISBN 3-932710-26-6 .

- Schmidt-Grépály, Rüdiger (ed.): On the return of the author. Conversations about the work of Friedrich Nietzsche. With Peter Sloterdijk , Renate Reschke and Bazon Brock . LSD , Göttingen 2013.

- Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann : Friedrich Nietzsche (= UTB . 3001). Fink, Paderborn 2008, ISBN 978-3-8252-3001-2 .

- Stefan Lorenz Sorgner , H. James Birx, Nikolaus Knoepffler (eds.): Wagner and Nietzsche: Culture-work-effect: A manual. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-499-55691-3 .

- Werner Stegmaier : Friedrich Nietzsche for an introduction. Junius, Hamburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-88506-695-8 .

- Bernhard HF Taureck : Nietzsche ABC. Reclam, Leipzig 1999, ISBN 3-379-01679-9 .

- Patrick Thor: »a continuous chain of signs of ever new interpretations« - Friedrich Nietzsche's ›Will to Power‹ and the semiotics of Charles S. Peirce . In: Muenchner Semiotik - Journal of the Research Colloquium at LMU (2018)

- Gianni Vattimo : Nietzsche: An Introduction. Metzler, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-476-10268-8 .

- Claus Zittel: Self- abolition figures in Nietzsche . Königshausen & Neumann 1995, ISBN 3-8260-1082-5 .

Work comments

The first 12-volume standard commentary on Nietzsche's works has been published since 2012:

Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften (Ed.): Historical and critical commentary on Friedrich Nietzsche's works . Berlin / Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 2012 ff. Nine volumes have been published so far:

- Jochen Schmidt : Commentary on Nietzsche's birth of tragedy (= historical and critical commentary on Friedrich Nietzsche's works. Vol. 1/1). XXI + 456 pages. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-028683-0 .

- Barbara Neymeyr : Commentary on Nietzsche's Untimely Considerations. I. David Strauss the Confessor and the Writer. II. On the benefits and disadvantages of history for life (= historical and critical commentary on Friedrich Nietzsche's works. Vol. 1/2). XXV + 652 pages. Berlin / Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 2020, ISBN 978-3-11-028682-3 .

- Sarah Scheibenberger: Commentary on Nietzsche's Ueber Truth and Lies in the extra-moral sense (= historical and critical commentary on Friedrich Nietzsche's works. Vol. 1/3). XV + 137 pages. Berlin / Boston: Walter de Gruyter 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-045873-2 .

- Barbara Neymeyr: Commentary on Nietzsche's Untimely Considerations. III. Schopenhauer as an educator. IV. Richard Wagner in Bayreuth (= historical and critical commentary on Friedrich Nietzsche's works. Vol. 1/4). XXV + 652 pages. Berlin / Boston: Walter de Gruyter 2020. ISBN 978-3-11-067789-8 .

- Jochen Schmidt, Sebastian Kaufmann: Commentary on Nietzsche's Morgenröthe. Idylls from Messina (= historical and critical commentary on Friedrich Nietzsche's works. Vol. 3/1). XIII + 611 pages. Berlin / Boston: Walter de Gruyter 2015, ISBN 978-3-11-029303-6 .

- Andreas Urs Sommer : Commentary on Nietzsche's Beyond Good and Evil (= historical and critical commentary on Friedrich Nietzsche's works. Vol. 5/1). XVII + 939 pages. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-029307-4 .

- Andreas Urs Sommer: Commentary on Nietzsche's On the Genealogy of Morals (= Heidelberg Academy of Sciences: Historical and Critical Commentary on Friedrich Nietzsche's Works. Vol. 5/2). XVII + 723 pages. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2019, ISBN 978-3-11-029308-1 .

- Andreas Urs Sommer: Commentary on Nietzsche's The Wagner Case. Götzen-Twilight (= historical and critical commentary on Friedrich Nietzsche's works. Vol. 6/1). XVII + 698 pages. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-028683-0 .

- Andreas Urs Sommer: Commentary on Nietzsche's Der Antichrist. Ecce homo. Dionysus dithyrambs. Nietzsche contra Wagner (= historical and critical commentary on Friedrich Nietzsche's works. Vol. 6/2). XXI + 921 pages. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2013, ISBN 978-3-11-029277-0 .

- To the reception history

- Richard Krummel : Nietzsche and the German Spirit . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1974–2006.

- Klemens Dieckhöfer: Gerhart Hauptmann (1862–1946) and Nietzsche. Nietzsche's influence on Gerhart Hauptmann and his experience of nature. In: Medical historical messages. Journal for the history of science and specialist prose research. Volume 34, 2015, pp. 123-128.

- Yearbooks

- Nietzsche Studies: International Yearbook for Nietzsche Research. De Gruyter, Berlin, ISSN 0342-1422 .

- Nietzsche research: yearbook of the Nietzsche society. Edited on behalf of the Förder- und Forschungsgemeinschaft Friedrich Nietzsche e. V. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin.

- New Nietzsche Studies. The Journal of the Nietzsche Society. ISSN 1091-0239 .

A curiosity: My Sister and I

In 1951, a book called My Sister and I was published in the United States, and Friedrich Nietzsche was named as the author. Nietzsche is said to have written this supposedly autobiographical text from 1889–1890 during his stay in the Jena mental hospital. However, no original manuscript has survived. Oscar Levy , the editor of the first English-language edition of Nietzsche's works, is named as the translator into English . Levy had died in 1946, and his heirs denied that he had anything to do with the work. Since there was no evidence for the alleged authorship of Nietzsche or Levy, the writing was mostly rejected as a forgery or ignored by the experts . In the 1980s, individual voices questioned this rejection. Parts of the controversy over authorship are reprinted in new editions of the book, such as:

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Oscar Levy (transl.): My Sister and I. Amok Books, Los Angeles 1990, ISBN 1-878923-01-3 .

Fiction

- Alexander Peer : Until death avoids us. Limbus, Innsbruck 2013, ISBN 978-3-902534-75-0 .

- Christian Schärf: A winter in Nice. Eichborn, Frankfurt 2014, ISBN 978-3-8479-0580-6 .

- Bernhard Setzwein : Not cold enough. Haymon, Innsbruck 2000, ISBN 3-85218-320-0 .

- Irvin D. Yalom : And Nietzsche cried . Ernst Kabel Verlag, Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-8225-0294-4 .

Movies

- Friedrich Nietzsche. Criminal story of a falsification. Germany / ZDF 1999, 60 min. Written and directed by Reinhold Jaretzky

Web links

Facsimile, texts and quotations

- Digital Facsimile Complete Edition (DFGA) - Digital reproduction of the entire Nietzschen estate, ed. by P. D'Iorio, Paris, Nietzsche Source, 2009–.

- Digital Critical Complete Edition Works and Letters (eKGWB) - all works according to the Critical Complete Edition, ed. by Colli / Montinari , ed. by P. D'Iorio, Paris, Nietzsche Source, 2009–.

- Works by Friedrich Nietzsche at Zeno.org . - This page follows the Schlechta edition , which is not free from errors in the later works and in the estate.

- Works by Friedrich Nietzsche in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Works by Friedrich Nietzsche in Project Gutenberg ( currently usually not available for users from Germany )

- Friedrich Nietzsche: The birth of tragedy from the spirit of music. Fritzsch, Leipzig 1872. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive ).

- Friedrich Nietzsche: So spoke Zarathustra.

- [Vol. 1]. Schmeitzner, Chemnitz 1883 ( digitized and full text in the German text archive ).

- Vol. 2. Schmeitzner, Chemnitz 1883. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive ).