Skopje

| Skopje Скопје Shkup / Shkupi |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Basic data | ||||

| Region : | Skopje | |||

| Municipality : | Skopje | |||

| Coordinates : | 42 ° 0 ' N , 21 ° 26' E | |||

| Height : | 245 m. I. J. | |||

| Area (Opština) : | 571.46 km² | |||

| Inhabitants (Opština) : | 544,086 (June 30, 2015) | |||

| Population density : | 952 inhabitants per km² | |||

| Telephone code : | (+389) 02 | |||

| Postal code : | 1000 | |||

| License plate : | SK | |||

| Structure and administration | ||||

| Structure : | 10 districts | |||

| Mayor : | Petre Šilegov ( SDSM ) | |||

| Website : | ||||

Skopje ( Macedonian Скопје , Albanian Shkup / Shkupi , Turkish Üsküp ) is the capital of North Macedonia and, with over 540,000 inhabitants, the largest city in the country. About a quarter of the population of North Macedonia lives in the big city. Skopje has a settlement history that goes back more than two millennia and is one of the oldest still existing cities in the country.

The city on the Vardar is both the seat of parliament and the government . It is also the cultural and economic center of the country, the Orthodox bishopric of the Macedonian Orthodox Church and the autonomous Archdiocese of Ohrid of the Serbian Orthodox Church and the seat of a Grand Mufti .

Surname

Founded by the Romans, the place was called Scupi in Latin . Are derived from all the other, developed later and city names in different languages: Macedonian Скопје Skopje , Albanian Shkupi or Shkup (specific or indefinite form), Turkish Üsküp , Bulgarian Скопие Skopje , Serbian Скопље Skopje and Greek Σκόπια Skopia . The form Üsküb was also used during the Ottoman rule .

geography

location

The geographical location of Makedonija Square (formerly Marshal Tito Square) in the city center is 41 ° 59 ′ 45 "north latitude and 21 ° 25 ′ 53" east longitude. The largest expansion of the urban area in east-west direction is around 33 kilometers, in north-south direction around 10 kilometers. The city has an area of 210 square kilometers.

Skopje is located in the north of the Republic of North Macedonia, about 18 kilometers south of the border with Kosovo . The river Vardar flows through the city from west to east , and the local mountain Vodno rises to the south . The city gives its name to the Skopje Basin , which includes Skopje (10%) and numerous other municipalities (90%). This high landscape opens to the east and merges into the wide and fertile valley of the Vardar, which runs through North Macedonia from northwest to southeast.

The distances from Skopje to the capitals of the neighboring countries of North Macedonia are illustrated in the table below.

| Capital | country | Distance ( beeline ) |

Compass direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pristina |

|

75 km | north |

| Belgrade |

|

320 km | north |

| Sofia |

|

175 km | Northeast |

| Athens |

|

490 km | south |

| Tirana |

|

150 km | southwest |

geology

North Macedonia lies in a seismologically extremely active region between the Eurasian and African plates . The exact limit is unclear as the Eurasian plate breaks up into several smaller plates in this area. The Apulian plate , which includes Italy and the Dinaric Mountains , deserves a special mention here .

Skopje lies roughly in a geological transition zone between the Dinaric Mountains in the northwest and the Rhodope Mountains in the east. This tectonic rift is called the Morava-Vardar furrow and is characterized by numerous tectonic faults and activities, as evidenced by the three earthquakes in the town's history (518, 1515 and 1963). The Skopje basin, surrounded by mountains, has an area of 2100 km².

Waters

The river Vardar , which has its source at Gostivar, 90 kilometers away, flows through the city and is used by bathers and swimming guests in summer. Numerous meanders and bridges - including the famous Kamen Most - shape the river.

In addition to the Vardar, there are other smaller rivers, all of which flow into the Vardar. One of the most important is the Treska , which flows into the Vardar in the west of the city ( Gjorče Petrov district ) at the Sveti Lazar hospital . In its upper reaches of the river is to Matkasee jammed, who as ninth largest lake Nordmazedoniens applies. With its many caves and deep canyons, the lake is a natural attraction for tourists.

The Lepenac rises near the Kosovar city of Prizren and flows into the Vardar after 75 kilometers in the Zlokučani district in the west of the city within the Karpoš district . It is the third longest river in Skopje.

City structure

The Opština of Skopje divided since the reform of the entire Macedonian administrative system from 2004 in ten municipalities that have their own mayor ever, a council, a coat of arms, a flag and political skills. A special feature of these opštini is that they often include not only districts of Skopje, but also other localities outside the urban space of the capital.

| number | Parish name | Area (km²) | Population (2002 census) |

Population density (inhabitants / km²) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aerodrome | 21.85 | 72.009 | 3,295.61 | |

| 2 | Butel | 54.79 | 36,154 | 659.86 | |

| 3 | Čair | 3.52 | 64,773 | 18,401.42 | |

| 4th | Centar | 7.52 | 45,412 | 6,038.83 | |

| 5 | Gazi Baba | 110.86 | 72,617 | 655.03 | |

| 6th | Gjorče Petrov | 66.93 | 41,634 | 622.05 | |

| 7th | Karpoš | 35.21 | 59,666 | 1,694.58 | |

| 8th | Kisela Voda | 34.24 | 57,236 | 1,671.61 | |

| 9 | Saraj | 229.06 | 35,408 | 154.58 | |

| 10 | Šuto Orizari | 7.48 | 22,017 | 2,943.45 | |

| A total of | City of Skopje | 571.46 | 506.926 | 887.07 |

climate

In the area around Skopje there is usually a transitional climate from continental to Mediterranean . The winters are rich in precipitation and cold, the summers are warm and poor in precipitation. However, due to the accumulated heat in the Skopje basin , it is much warmer here than in the rest of the country. The annual mean temperature is 12.1 degrees Celsius and the average annual rainfall is around 504 millimeters.

The warmest months are July and August with an average of 22.3 degrees Celsius, the coldest is January with an average of 0.2 degrees Celsius. Most of the precipitation falls in May with an average of 60 millimeters, the lowest in August and September with 27 and 36 millimeters respectively.

| Skopje | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Average monthly temperatures and rainfall for Skopje

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

population

In terms of population and area, Skopje is the largest city in North Macedonia: Around a third of the country's population lives in the city on the Vardar. Different ethnic groups , languages and religions characterize the population structure.

The last census of North Macedonia was in 2002, when the municipality of the city of Skopje had 506,926 inhabitants. About 2.52 percent of them or 12,774 people were illiterate and around 28.46 percent or 144,271 people were unemployed. According to an update by the Statistical Office, Skopje already had 544,086 inhabitants on June 30, 2015.

Ethnicities and languages

As in large parts of the country, different ethnic groups live together in Skopje. For 2002, of the 506,926 inhabitants, 338,358 (66.75%) identified themselves as Slavic Macedonians , 103,891 (20.49%) as Albanians , 23,475 (4.63%) as Roma , 14,298 (2.82%) as Serbs , 8,595 (1.70%) as Turks , 7,585 (1.50%) as Bosniaks , 2,557 (0.50%) as Aromanians and 8,167 (1.61%) reported a different ethnic group.

The languages with the most native speakers in 2002 were Macedonian , Albanian , Romani , Serbian , Turkish and Bosnian .

Religions

The religions with the most followers are Orthodox Christianity and Islam with a Sunni character. There are also minorities of Catholics , Protestants , Reformed and also a few Jews . Most of the Orthodox Macedonians are organized in the Macedonian Orthodox Church , whose metropolitan resides in Skopje, even if the bishopric is nominally in Ohrid . A large part of the Muslim Albanians belong to the Islamic Believers' Association in the Republic of Macedonia (Alb. Bashkësia Fetare Islame në Republikën e Maqedonisë ). The Grand Mufti of North Macedonia has its seat in the capital.

Personalities

history

City history

Creation of Scupi

The earliest traces of human settlement in the Skopje area were found inside the Kale fortress. They date from the Neolithic Age and are over 6,000 years old. The settlement brought to light by archaeologists was founded by an as yet unknown people who lived in the region for several centuries from the Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age .

The first known settlers in the Skopje area were the Triballer , who belonged to the Thracians . After them came the peonians , but in the 3rd century BC. The Dardaner , an Illyrian tribe, were able to occupy the area and they founded a large kingdom that stretched from the Scupi settlement to Naissus in the north and the Albanian Alps in the west. The Dardans declared in the 2nd century BC BC Scupi became their capital and extended their empire to Bylazora (near today's Veles ) in the south.

The Romans conquered in the course of the Macedonian-Roman wars in 168 BC. BC also the empire of the Dardaner, but for decades they were only able to enforce their rule in Macedonia and Illyria only sparsely. The Roman emperor Domitian (81 to 96 AD) settled veterans of the legions I Italica , III Augusta , IV Macedonica , V Macedonica , V Alaudae , IIII Flavia and VII Claudia in the military camp-like settlement of Scupi at the beginning of his rule . The place gained the status of a Colonia in AD 86 and was also called Colonia Flavia Aelia Scupi .

- The Roman Scupi

The archaeological excavation work in the ancient site of Scupi began between the two world wars and in 1925 brought an early Christian basilica to light. The most important building, a Roman theater, followed later . The Skopje City Museum began restoring various ruins for the first time in 1966 . In 2008 archaeologists found a 1.7 meter high statue of Venus . A total of over 23,000 objects have been found so far.

The excavated buildings of Scupi include the aqueduct , some thermal baths , individual townhouses and the theater. With the exception of the theater, which has fallen into disrepair, all buildings can be visited. The archaeological site of Scupi is about four kilometers northwest of the city center on the other side of the Vardar.

middle Ages

The next centuries were very eventful for the small town. In 518 an earthquake devastated the entire city; however, the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I had it rebuilt. Not even 100 years passed when, in the winter of 594/95, in the course of the Slavs' conquest of the Balkans, tribes of the Slavs razed the city to the ground. The Middle Ages between the invasion of the Slavs and the conquest by the Ottomans in the 14th century was characterized by bloody power struggles between regional powers, above all the Byzantines and Bulgarians . In the 9th century the latter joined the city to the First Bulgarian Empire and was able to hold its own for several decades. The Christianization of Bulgaria also made it a bishopric. In 980, Tsar Roman declared Skopje to be the Bulgarian capital and the seat of the Bulgarian patriarch for a short time . In 1004 there was a great battle between Byzantines and Bulgarians in the outskirts of Skopje . After the fall of the First Bulgarian Empire in 1018, the Byzantines conquered the city and declared it the capital of the Byzantine theme of Bulgaria . The rule of Byzantium did not last long, however, and led to the strengthening of the local Boljars . As early as the 12th century, after an uprising, the Bulgarians were able to recapture Skopje and incorporate it into their Second Empire . The Boljar of Skopje, Konstantin Tich Assen , was appointed Bulgarian tsar in the Bulgarian civil war and the region around Skopje was subsequently directly subordinate to the Bulgarian tsars.

In 1282 the Serbian Nemanjid king Milutin wrested the city from the Bulgarians. Skopje developed into the new residential city of the Serbian ruling dynasties. On April 16, 1346 King let Stefan Uroš IV. Dušan and his spouse in Skopje from Bulgarian Patriarch Simeon and the Archbishop Nikolai of Ohrid for the Serbs Czar and Czarina crown. He also raised the head of the Serbian church Joanikije II to the first Serbian patriarch.

Ottoman time

On January 19, 1392 Skopje came under Ottoman rule for more than 500 years . As the Yugoslav orientalist Hasan Kaleshi (* 1922 in Srbica ; † 1976) reports, the name of the first Ottoman Margrave , who lived in Skopje, was Paşayiğit Bey , who perhaps had the oldest Islamic building in the city, the Meddah Baba Mosque, built around 1397 . He was followed by his adoptive son Ishak Bey , who built a hospice (later converted into a Friday mosque, known as the Colorful Mosque ) and also donated a madrasa (not preserved) including a library. To maintain his community facilities, Ishak Bey stipulated the income of two hamams , 102 shops and two hans as well as the income of two villages and seven rural complexes including fields and gardens from the surrounding area in his Wakfiye . He himself was later buried in the courtyard of the Colorful Mosque, but not, as is often stated, in the domed grave tower behind the mosque, which for stylistic reasons must be dated to the second half of the 15th century.

In the middle of the 15th century, Üskub had 5,145 residents who were registered for tax purposes. Of these, 3,330 were Muslims , mainly Turks from Asia Minor and 1,815 Christians . Because Christian ethnicity was insignificant for tax purposes, it was not recorded. However, it can be assumed that they spoke a South Slavic language, Greek and / or Albanian. The greater part of the population worked in trade . An economic boom occurred in Skopje in the 16th century. It was favored by the location of the city at the junction of the trade routes from Edirne to Saraybosna and from Selanik to Belgrade , by the Ottoman protectorate over Dubrovnik and the arrival of Sephardic Jews . Around the middle of the 16th century, the city had more than 10,000 inhabitants (7425 Muslims, 2735 Christians and 265 Jews) who were active in around 80 different professions. A synagogue was first built in Skopje in 1361. Another major earthquake struck around 1515.

A detailed description of Skopje, which was important for the High Ottoman period (16th / 17th century), three decades before Skopje was set on fire by the Habsburg general Giovanni Norberto Piccolomini in 1689, can be found in the “travel book” ( Seyahatnâme ) of the Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi . He described the city as a huge settlement that stretched on both sides of the Vardar. The citadel lay over the city, with about 100 crew houses, storehouses and armories. The approximately 1060 stone houses with their red bricks shaped the cityscape. During this time there were also 9 schools for reading the Koran, which were attached to the mosques, 20 dervish monasteries ( Tekke ), one Mewlevik monastery and 70 schools (Mekteb).

In Üsküb, Evliya witnessed the lively economic life in over 2100 shops in the several bazaars in 1660 . Regarding the population structure, he notes that in addition to the Muslims, there are also residents of Armenian , Bulgarian , Serbian and Jewish origins in the city who had their own places of worship. A large number of Catholics also lived in the city, but they held their services in the Serbian churches.

The development of Skopje was abruptly interrupted when in the Great Turkish War (1683–1699) Austrian troops under General Giovanni Norberto Piccolomini advanced as far as Macedonia. On October 25, 1689, his army took the city without much fighting because the Ottoman forces and many residents had left the place. Piccolomini ordered that Skopje be burned down, which happened on October 26th and 27th. Apparently the spread of cholera should be prevented. The fire destroyed many homes and businesses. The Jewish quarter was hit hardest. Most of the houses, two synagogues and the Jewish school were destroyed by the fire.

Late Ottoman period

The city was slow to recover from the fire. The hundred years of Skopje's history that followed this destruction in 1689 are largely in the dark. A few isolated sources report that the mosque of Sultan Murad II was repaired in 1712, 23 years after the fire. An Ottoman plan of the district around the mosque mentioned shows that at that time most of the buildings there were still destroyed. Travelers who visited Üsküb towards the end of the 18th or beginning of the 19th century consistently report about 5,000 to 6,000 inhabitants, compared to 40,000–60,000 inhabitants before the fire or even 1,500 houses that were quite small and lined dirty streets.

Skopje also got caught up in the turmoil of nationalism in the Balkans in the 19th century. In 1844 Albanians organized an uprising against the Ottoman Empire. They protested against taxes that were felt to be too high and the policy of centralization. After the uprising was crushed, many Albanian residents were imprisoned or exiled to Asia Minor .

An upswing began in the course of the 19th century, not least due to the construction of railway connections promoted by the late Ottoman state, combined with the influx of non-Muslim populations. From 1873 Skopje was connected to Thessaloniki by a railway line along the Vardar, and in 1888 also to the Serbian railway lines. From now on the city was directly connected to Central Europe via Belgrade . Connections to Bitola and Istanbul followed in the 1890s . Skopje was the capital of a Sanjak and from 1888 ( replacing Pristina ) the capital of the Ottoman province ( Vilâyet ) Kosovo. During this time Skopje became the third largest city in Macedonia after Thessaloniki and Bitola. At the turn of the 20th century, Skopje had 30,000–40,000 inhabitants, primarily as a result of the influx of Slavic Christians from the rural areas, which gave the city a non-Muslim majority for the first time since the 15th century.

In the struggle for a Bulgarian church independent of the Greek ecumenical patriarchate of Constantinople, the Greek bishop was expelled several times in the 1830s and the sending of a Bulgarian bishop was demanded. The conflict came to a head when the Bulgarian community of Skopjes founded the Church of Our Lady and an associated monastery school (built in 1836/37). The former was built by the builder Andreja Damjanov . The project was made possible by the loosened Ottoman building laws that once restricted the construction and renovation of Christian churches. Around 1850 the school was converted to the Lancaster system and in 1895 to the Bulgarian Pedagogical School .

According to the Ferman issued by Sultan Abdülaziz on February 28, 1870 for the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate , Dorotej von Skopje, the first Bulgarian bishop of the Eparchy of Skopje, was installed in 1874 after a plebiscite of the Slavic population , who finally submitted to the Bulgarian Exarchate .

The 20th century

Two years after the Young Turkish Revolution , the Young Turks carried out a census throughout the Ottoman Empire in 1910. Accordingly, the Jewish community was represented by 2,327 people.

In August 1912, Skopje was taken by 30,000 Albanian insurgents, led by Isa Boletini and against the policies of the Ottoman Empire. During the Balkan Wars , Skopje was conquered by the Serbian armed forces on October 25, 1912 and came under the rule of Belgrade. The Serbian troops wreaked havoc in the city. Albanian and Turkish houses were set on fire, people were beheaded and their bodies piled up in the streets. According to a report by Leon Trotsky , not only men but also hundreds of children and women were set alive. With the new demarcation after the Balkan Wars in 1912 and 1913, when Bitola became a border town with Greece, the rise of Skopje to the undisputed center of "southern Serbia" began. During the First World War it was captured by Bulgarian troops on October 10, 1915. As they withdrew, the Serbs set fire to the northern part of the city, which caused great damage to historical buildings. In 1918 Skopje was retaken from Serbia and, like all of today's Macedonia, belonged to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes , which was renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929 and made Skopje the capital of the newly established Vardarska banovina (Banschaft Vardar) in the same year .

During the Second World War , from 1941 to 1944, Skopje was again occupied by Bulgarian soldiers and fighters from the VMRO and on August 2, 1944, it was declared the capital of the new Socialist Republic of Macedonia , which was a republic of communist Yugoslavia .

At 5:17 a.m. on July 26, 1963, a major earthquake struck the history books. On that day the earth shook and the disaster claimed 1070 lives. Around 75 percent of the population lost their home and 3,300 people suffered serious injuries. Almost the entire old town was razed to the ground. The tremors could be felt all over the country and also in neighboring Kosovo and Serbia. In total, property damage totaled over a billion US dollars . With international help, Skopje was rebuilt over the next few years; the Japanese architect Kenzō Tange developed a master plan for the city on the Vardar.

“The day before the earthquake was an ordinary day: school, children's games and dinner with my parents. I was eight years old. My parents went to work early. The earthquake woke me up. When I thought of my sister, I quickly ran back up the stairs. My one-year-old sister was still at home. I ran back, took it, and ran in front of the building. All the neighbors were there. They wore pajamas or just underpants. The picture was terrible. The building I had lived in was no longer there. It was just leftovers. You could hear people screaming, crying and calling out names. Many names were heard. I lost my mother. She was one of the 1000 people who lost their lives. "

Skopje has been the capital of the independent Republic of Macedonia since 1991, and North Macedonia from 2019. During the Kosovo war , city authorities took in thousands of refugees from neighboring Kosovo. Bloody fighting between the Macedonian UÇK and the state police took place just a few kilometers northeast of Skopje near Aračinovo during the Albanian uprising in 2001 . At the beginning of 2016 there was a conflict over the erection of an oversized cross .

Population development

| year | Residents |

|---|---|

| 1450 | 5,000 |

| 1550 | 10,000 |

| 1650 | 40-60,000 |

| 1800 | 5-6,000 |

| 1900 | 30.- 40,000 |

| 1981 | 408.143 |

| 2002 | 506.926 |

The city has seen two major population increases in its history. The first large population growth could be recorded in the Ottoman or, more precisely, in the High Ottoman period (17th century). During these decades, Skopje grew into a supra-regionally important trading city with 40,000 to 60,000 inhabitants. The second population surge began during the Yugoslav era, when large investments in industry and infrastructure were made in the city. The thriving economic city attracted many people from all over North Macedonia who were looking for work. In the last Yugoslav census of 1981, 408,143 people were registered for Skopje. Since then, the city's population has increased by around a quarter. The 2002 census recorded 506,926 residents.

Tourist Attractions

With a settlement history of over 2000 years, Skopje has a large number of buildings and monuments from different epochs. For example, the aqueduct of the ancient city of Scupi has been preserved from Roman times . In the Middle Ages, the spread of Christianity in the Balkans resulted in numerous Byzantine churches and monasteries in the area as well as in the city. The Islamic architecture left behind during the 500 years of Ottoman rule their mark in the form of mosques , bridges, Hamame , caravanserais , libraries, and especially in the bazaar section, the old town of Skopje. With the blossoming of nationalism in south-eastern Europe at the beginning of the 19th century, the city on the Vardar became a center of the Bulgarian and Albanian resistance movements against the sultanate on the Bosporus. Bulgarian and Albanian clergy were again able to build Orthodox and Catholic churches on a large scale.

The fortress Kale ( Macedonian Скопско кале , Albanian Kalaja e Shkupit ) is located on a hill west of the old town and on the north side of the Vardar. The first traces of human settlement on the castle date from the 4th millennium BC. Under the Bulgarian Tsar Samuil (10th century AD), a fortified settlement stood on the hill for the first time. In 1391 the city and the surrounding region were conquered by the Ottomans . Large parts of the city, including the fortress, were destroyed by the war. After that, the castle served as a barracks for the Ottoman troops. The fortress and Skopje then lost their economic importance in the region. The castle was renewed around 1700. The current outer wall, towers and gates also date from this period. The east gate was the most important; it led straight into the bazaar . Also in the 20th century the fortress served as barracks for the troops of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia ; ten large military buildings, headquarters and barracks were built. In 1951 the armies withdrew and the Archaeological and Historical Museum took over the management. Most of these modern buildings were destroyed in the severe earthquake in 1963. Since then, numerous archaeological works have been carried out on the fortress.

The stone bridge over the Vardar ( Macedonian Камен мост Kamen most , Albanian Ura e gurit ) used to connect the old town north and south of the river. Today the southern old town is overbuilt by modern buildings. The bridge was built from 1421 to 1433 by Ottoman architects on behalf of Sultan Murad II , using the foundations of an older bridge from the 6th century. The seven-arched bridge is 213.85 meters long. It was renovated in 1555, in the 18th and 19th centuries, as well as in 1905 and 1994. In addition to the fortress, it is another symbol of the city, which is why it is also shown on the city coat of arms.

The Daut-Pascha- Hamam (bath house) is located northeast of the stone bridge and was built by the Grand Vizier of Eastern Rumelia , Daut Pascha , from 1489 to 1497, whereby a gender-separated use was intended. The structure has 13 domes. The two largest domes house the two cloakrooms and some fountains. The smaller domes cover the different bathrooms. Today the building houses the National Art Gallery, which has a large collection from the 18th and 19th centuries.

The Çifte Hamam in the central old town was also built in the 15th century. The bathhouse was used until 1915. The city's Jewish residents also used the complex for their ritual ablutions. Today it is a contemporary art gallery.

With around 70 mosques , Skopje was an important Islamic center in the region. There are far fewer today than in the Ottoman era. The oldest Islamic places of worship are in the old town. Among the best preserved there are the Isa Bey Mosque from 1475, the Sultan Murad Mosque from 1436, the Colorful Mosque from 1438 and the Mustafa Pasha Mosque from 1492.

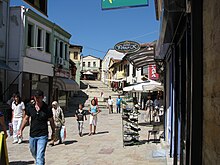

Because of its strategically important location, Skopje was also an important base for traders, travelers and caravans. The best preserved caravanserais Kapan Han (15th century), Kursumli Han (1550) and Suli Han (15th century) were the largest Ottoman inns in the city. Today it houses restaurants and the Kapan Han houses the bazaar museum.

Other Ottoman buildings are the clock tower from 1566, the Bezisten and the bazaar on the northern edge of the old town as well as the entire historic city center.

The Church of St. Panteleimon ( Macedonian Црква Свети Пантелејмон ) from 1164 is located southwest of Skopje on the ridge of the Vodno in the village of Nerezi . It has numerous frescoes and is one of the most important surviving Byzantine works of art from the Coman era.

The St. Nikita Monastery ( Macedonian Манастир Свети Никита ) was built between 1307 and 1308 by the Serbian King Milutin . It stands in the village of Banjani, northwest of the city.

There are also some sights from more recent times. These include the Church of Our Lady from 1835, the Kliment von Ohrid Church from 1990, the old train station in the center, which today houses the city museum, and the Millennium Cross on Mount Vodno. A gondola lift leads up Skopje's local mountain, and hikes either to the middle station or to the summit are popular.

One of the relics from Ottoman times is the Skopje clock tower (also called Sahat Kula )

The Colorful Mosque is one of the most architecturally outstanding buildings from the Ottoman era

The interior of the Isa Bey Mosque

Cityscape

General

Skopje has an eventful cityscape, which is characterized by its eventful history, by the various religions and ethnic groups as well as by different social conditions.

For a long time, today's old town was the economic and cultural center of Skopje. Ottoman town houses, narrow cobblestone streets, fountains, mosques, inns, rest stops for traders, workshops, bathhouses and tekken were important parts of the cityscape. With the fall of the Ottoman Empire, its rulers withdrew from the city and a new era began for Skopje. Called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes until 1929 , the Kingdom of Yugoslavia replaced the Ottomans. Not much has changed in the appearance of the city on the Vardar yet. Only during the economic growth after the Second World War did the socialist government of Yugoslavia invest in infrastructure, industry and culture in Macedonia and Skopje. Large new residential areas with the typical prefabricated buildings , large industrial areas, wide streets and boulevards, many schools and hospitals and the railway network were expanded. At the same time, the population grew and the city spread along the Vardar more and more to the west and east. In the course of this building boom, large parts of the historic city center were built over, which slowly began to disappear from the cityscape. Today, multi-lane roads lead around and through the old town. The historical core on the other bank of the Vardar was almost completely destroyed and replaced by new buildings. Today there are many factories and commercial buildings in the east of the city, but they have had to cut their economic activity significantly and are no longer running as they did in Yugoslav times. In the north, however, on the main road to Pristina, new companies have sprung up since the 1990s and employ some of the residents. In the Aerodrom district behind the train station there are housing estates built in the Yugoslav era with multi-storey high-rise buildings on an area about the size of the Čair district .

Parks

The city park (maz. Gradski Park , alb. Parku i Qytetit ) is located northwest of the center along the Vardars and extends over an area of 500 by 600 meters. The football stadium and a sports hall are very close by . The park is also home to a zoo, a botanical garden and a bonsai garden. Artificial ponds and many canals in the green shape the appearance of the park. On a hill northeast of the old town is the 700,000 m² Gazi Baba Park, which consists of a forest and footpaths. Gazi Baba Park is the city's most important recreational area.

Skopje 2014

The then government, led by the conservative party VMRO-DPMNE , has invested in many ethnic Macedonian cultural institutions since it came into power after the parliamentary elections in 2008 . By 2014, a large number of monuments (mostly “ethnic Macedonian heroes”) and mostly historicizing buildings were erected. In addition to a 22-meter-high statue of Alexander the Great and the largest Macedonian Orthodox Church on the main square, new buildings for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Macedonian State Archives and other public institutions have also been built. When the construction work began in the summer of 2010, the Macedonian Constitutional Court declared it illegal because the planning and awarding procedures for many buildings had not proceeded according to the regulations. However, the government under Nikola Gruevski declared this court decision invalid and allowed the construction work to continue. Originally, total costs were estimated at around 80 million euros, but at the end of 2010 the costs were already estimated at 200 million (this corresponds to 2.68 percent of the gross domestic product). Critics think that the money could be better invested, for example in the partly outdated transport infrastructure. The Muslim minority in the city (around a third of the population), especially the Albanian, sees itself discriminated against by the construction projects, as their taxpayers' money is supposed to help finance the construction of the church (and other facilities), while the mosques have to be financed privately . The government and its sympathizers see the building as creating an identity, the Muslims and opponents of the building feel marginalized by the state.

The neighboring country Greece also criticized the construction of the partly nationalistic structures and monuments. There, the imposing statue of Alexander in the main square aroused people's hearts (see dispute over the name of Macedonia ). In 2011 the triumphal arch of Macedonia was completed, which shows the entire region of Macedonia on one motif . This caused head shaking in Albania, as the historical region of Macedonia also includes part of the Albanian national territory. The Albanian government made a demarche to the Macedonian government . The erection of the Tsar Samuil statue, in turn, worsened relations with its eastern neighbor Bulgaria (which, however, have returned to normal), which had never commented on the Skopje 2014 project. In 2012, the former Prime Minister Ljubčo Georgievski criticized the project because of the lack of a concept, the waste of funds and called it a “great caricature”, “historical kitsch” and “Macedonian Disneyland”.

The government policy of the VMRO-DPMNE visibly worsened the domestic and foreign policy situation, protests by Albanians against the establishment of a new Orthodox church in the historic Kale fortress escalated and further intensified intra-ethnic relations.

Culture

Skopje is the cultural center of North Macedonia. The country's largest museums, operas, theaters and other cultural institutions are located here. For a long time and still today, the city was a melting pot of different cultures and religions, which clearly left their mark on the city in different ways.

Museums and galleries

There are numerous museums and galleries in Skopje, which are among the largest in the country. The Museum of Contemporary Art houses the largest art collection in North Macedonia and is the most important cultural institution of contemporary art . Founded on February 11, 1964 by a city council resolution, the new museum was part of the new master plan for the city after the catastrophic earthquake of 1963. In 1970 the museum moved into the current building, which was designed by Polish architects. The museum to the north of Kale Fortress now has a collection of 1,000 exhibits.

The 1963 earthquake destroyed the city's old train station, which was built in 1938, and in its place is now a small art gallery as well as the Skopje City Museum , which contains objects of the first human settlement in the 5th millennium BC. Shows until today.

The National Art Gallery of Macedonia is housed in the former Daut-Pasha Hamam , which is located in the old town. Founded as an institution in 1948, the gallery today has an art collection since the 14th century.

The Museum of Macedonia is a state institution and was created in 1991 from a merger of the Archaeological, Historical and Ethnological Museums, some of which had existed since 1924. Exhibits dating back to antiquity are on display over an area of around 6,000 square meters. The museum is located in Kursumli Han , an Ottoman building from the 16th century.

The Mother Teresa Memorial House is a memorial that opened on January 30, 2009 in honor of Nobel Peace Prize laureate and humanist Anjeza Gonxhe Bojaxhiu, known as Mother Teresa. The museum is located near the central Makedonija square and houses various objects from the life of the Albanian Catholic clergy in their replica birth house. There is also a life-size statue of the nun in front of the building. In the place of the memorial house, there used to be the Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, in which the blessed was baptized on August 27, 1910 one day after her birth.

The Natural Science Museum is located northwest of the city center on Vardar. Connected to it are the zoological and botanical gardens and the city park. The museum, built in the 1920s, has a collection of 4,000 exhibits from mineralogy , paleontology , botany and entomology .

The Natural History Museum was founded in October 1926 and has around 4000 exhibits on 1700 square meters. Minerals, stones, fossils, plants, invertebrates, insects, fish, amphibians and reptiles, birds and mammals from the area of Macedonia are collected, studied and exhibited.

The museum of the old bazaar is housed on the ground floor of the Suli Han ( caravanserai ) in the old town, built in the 15th century . With its collection of photographs and maps from this period, it shows the importance of Skopje for regional traders. Products from workshops and manufactories from the Ottoman period are also on display. The bazaar museum is one of the few photos from the 1963 earthquake.

The State Archives of Macedonia was founded on April 1st, 1951 and has a large archive collection of which 15,000 copies have been digitized.

On the Albanian national holiday, November 28, 2008, the UÇK Freedom Museum was opened in the Čair district . It shows the efforts of the Albanian people for freedom and emancipation from the founding of the League of Prizren in 1878 to the domestic political crisis of Macedonia in 2001 .

theatre

The National Theater is located just east of the Kamen Most stone bridge on Vardar. Due to its repertoire operation , the theater is the center of the Macedonian musical theater scene. The first piece performed was Cavalleria rusticana on May 9, 1947.

Events

Various occasions have a long tradition in Skopje. Music and literature festivals in particular are among the biggest cultural events of the year.

First launched in 1979, the Skopje Summer Festival is the most important and largest cultural event of the year. Artists, musicians, entertainers and performers show their achievements in the fields of music, fine arts, film, theater and multimedia performance for one month in the summer. Venues are numerous facilities and public spaces.

The Skopje Jazz Festival has been a jazz festival that has been taking place since 1982 and is part of the European jazz network. In addition to jazz, Cuban music and experimental music are also played. The festival takes place annually at the beginning of October and is always very popular. The most famous musicians who have performed include Ray Charles , Herbie Hancock , John McLaughlin .

Every year in July, the Blues and Soul Festival is held, where various blues and soul musicians from Europe and North America take part. The venues are mostly clubs and pubs.

The May Opera Evenings are classical music evenings. Ballet , opera and instrumental concerts are part of the program of the event, which has been taking place in the National Theater since 1972.

In May 1976, young enthusiasts launched the Open Youth Theater Festival . Her goal was to create a center for the younger theater scene in Yugoslavia in Skopje . Soon they achieved that too, and the Open Youth Theater became a destination for young people eager to show their talent to the public. Alternative and experimental theater performances as well as improvisational theater are shown by directors, actors and musicians.

The Linden Festival is one of the largest and most important literary events in Macedonia. Founded by the Macedonian Writers' Association in 1997, national and international authors, poets and writers can take part in the festival. It takes place in early June, when the linden trees bloom in the city , after which the cultural event is named. One award is given to a national poet and another to an international poet.

Sports

As the capital, Skopje is home to many national sports teams and clubs. The football clubs Vardar Skopje and Rabotnički Skopje play in the Prva Makedonska Liga and have won the championship several times. The handball teams Kometal Gjorče Petrov Skopje and RK Metalurg Skopje are the best known in the country and have often been able to take part in international events. The Philip II football stadium is located northwest of the city center on Vardar right next to the city park and is the largest stadium in the country with almost 37,000 seats. The two football clubs play their home games there.

The Boris Trajkovski Sports Center is a multifunctional sports hall and is used for smaller sporting events such as hand and basketball games. It is named after the former Macedonian President Boris Trajkovski , who was killed in a plane crash in 2004. In 2008 it was one of the two venues for the European Women's Handball Championship . It has a capacity of 6,000 to 10,000 seats.

The Skopje Marathon takes place every year in late spring and is always very popular.

politics

City Councilor and Mayor

The Skopje City Council has 45 members. For the legislative period 2009–2013 and 2013–2017, the councils were and are divided among the parties as follows:

| Political party | Alignment | Seats 2009-2013 |

Seats 2013-2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| VMRO-DPMNE | conservative | 19th | 22nd |

| SDSM | social democratic | 11 | 14th |

| BDI | Albanian | 5 | 5 |

| DR | Albanian | 3 | 1 |

| PDSA | Albanian | - | 3 |

| LDP | liberal-democratic | 3 | |

| VMRO-NP | national-conservative | 2 | |

| STLS | Communist | 1 | |

| GIKK | initiative | 1 |

Mayor of the city has been Petre Šilegov (SDSM) since 2017 .

City symbols

The shield-shaped coat of arms of Skopje shows the stone arch bridge Kamen Most, the Vardar, the Kale fortress and a snow-capped mountain.

The flag of Skopje is a red, vertical banner in a 1: 2 ratio. In the upper left quarter the coat of arms is placed in golden yellow.

Town twinning

Skopje has had a total of 18 town twinning agreements since 1961.

Economy and Infrastructure

economy

Skopje is the economic metropolis of North Macedonia. The leading companies in all economic sectors are based in the capital. The Stock Exchange Macedonian Stock Exchange began its work in 1996 and is the largest stock index of the country. A total of 30 joint stock companies are registered. The National Bank of North Macedonia regulates, among other things, the rate of the denarius . It is also based in the capital. In 2002 there were around 64,000 companies based in the city. Unemployment was 14.07 percent in the same year, lower than the national average, which was estimated at 19 percent. For January 2012 the unemployment rate in Macedonia was put at 31.8 percent. However, unemployment is particularly widespread among young people; In 2011, 52.5 percent of 15 to 24 year olds were unemployed in the country.

Most of the population is employed in services. These include banks (including Komercijalna banka , Tutunska Banka and First Investment Bank (UNIBanka)), insurance companies, post offices ( Makedonska Pošta ), telecommunications companies ( Telekom Makedonija ) and energy supply companies ( EVN ,).

Quite a few also work in industry, which is now partly out of date, as it was expanded mainly during the socialist era of Yugoslavia. This is testified by the large industrial area in the north of the city, where there are factories for food production, pharmacy ( alkaloid ) and many other areas. The refinery of the former OKTA joint stock company, which went into operation in 1982, is located outside the city and is the only oil refinery in the country. In 1999, OKTA was merged with the Greek Hellenic Petroleum . Makpetrol is the largest joint stock company in the oil production and processing sector. Heavy and metal industries also make up a significant part of Skopje's economy. Makstil is one of the largest steel producers in the country. Granit AD is the largest company in the construction industry .

Skopje is a trade fair city . Several times a year there are trade fairs on topics such as sales, facilities, trade, wine, finance, tobacco, machinery, agriculture, energy, electronics, industry, services, technology, upbringing, education and much more.

For some years now, tourism has also become an increasingly large branch of the economy. The many sights, the varied cultural events, the lively nightlife, the gastronomy and the role as the capital of a south-east European country attract numerous tourists from all over the world. But Skopje cannot yet compare itself with the tourist stronghold of Ohrid .

media

Skopje plays an important role in the history of radio in North Macedonia. Radio pioneers founded on December 28, 1944, in the middle of World War II , the station Radio Skopje , which for a long time was the only one in the country. The first radio broadcast was a broadcast of the second session of ASNOM , the highest legislative power in the newly formed state. Macedonian television history is also closely linked to the capital Skopje. Around 20 years after Radio Skopje , the first television program was broadcast by Television Skopje on December 14, 1964 . The Macedonian Radio MRT was founded on the same day and was part of the Yugoslav Radio JRT until 1993 .

With the democratization that began after 1993, the first private broadcasting companies were founded. Such as the television station A1 in 1993, which however ceased its work in 2011, and others such as Sitel (1993), Kanal 5 (1998) and Alsat-M (2006).

The first Macedonian newspapers appeared in the city on Vardar. The oldest daily newspaper close to the Social Democrats is Nova Makedonija . This was followed on November 11, 1963 Večer , which is nationally conservative . Dnevnik , Vreme , Utrinski Vesnik , Vest , Makedonija Denes and Spic are independent daily newspapers, and Fakti and Koha are the independent daily newspapers of the Albanian minority.

traffic

Skopje is a traffic junction and forms the northern entrance to the Vardar Valley, which forms a bottleneck in the important traffic corridor from Central Europe to Thessaloniki in Greece . In the narrow valley, the railway and the motorway run parallel. The largest airport in the country is also located at this bottleneck, around 20 kilometers east of the city center .

The M3 motorway connects Skopje with the Kosovar capital Pristina and is the most important route to the neighboring country. The M4 runs from the capital to the western and southwestern cities of the country and connects Macedonia with Albania at Qafë Thana . This route is part of the Pan-European Transport Corridor VIII , which connects the Bulgarian ( Black Sea ) with the Albanian port cities ( Adriatic Sea ) through Macedonia . Skopje is an important intersection of these pan-European traffic corridors , as the 8th corridor and the 10th corridor intersect here. This connects central Europe from Salzburg with Greece near Thessaloniki .

In 2009, the Skopje bypass motorway was opened, which, with a length of 27 kilometers, relieves the inner city of transit traffic. It leads from the motorway junction at Ilinden in the east of the city to the north and ends at the motorway junction at Kondovo in the west of the city. On the way, it also branches off with the M3 motorway. The entire new bypass cost the Macedonian government around 135 million euros .

Skopje is the seat of the Macedonian railway company MŽ , which also operates its main train station here. There are connections to Belgrade , Thessaloniki , Fushë Kosova , Kičevo , Kočani and Bitola . There are also plans for a railway line from Sofia to Tirana that will run through Skopje. The new Skopje train station , built after the 1963 earthquake, is located in the Aerodrom district to the east of the center.

The bus station is located directly at the train station, from where there are regular local and international bus connections to neighboring countries and Central Europe. Since 2011/12, conspicuous red double-decker buses have dominated city traffic , designed by the Chinese manufacturer Yutong based on the London Routemaster bus. This is a reintroduction, as there were a number of used London double-deckers in Skopje as early as 1960.

The construction of a tram line is planned for 2019 [obsolete] .

Education and Research

schools

Skopje has 21 middle schools / high schools spread across the city.

Universities and colleges

The University of Skopje is the largest university in the country and has around 50,000 students. It is named after Cyril and Method and was founded between 1946 and 1949. Another state university is the International Balkan University, which is much smaller with 500 students . In addition, many private universities and colleges are based in the capital. Including the very first private university in Macedonia, the FON University . The University American College , New York University, and the Orthodox Faculty of Theology are also some of the larger private universities in the city and in Macedonia.

Libraries

The National and University Library of North Macedonia is located in the city center south of the historic city center right next to the National Theater and is the largest library in the country.

The city library, named after the Miladinovi brothers, now has around 60,000 books, sheet music and magazines. It started work on November 15, 1945 and is located in the Karpoš district west of the center on Ivan Agovski Street .

literature

- Fikret Adanır: Skopje, a Balkan capital. In: Harald Heppner (Ed.): Capitals in Southeast Europe: History - Function - National Symbolism. Vienna 1994, pp. 149-170.

- Divna Pencic, Ines Tolic, Biljana Stefanovska, Sonja Damcevska: Skopje. An Architectural Guide. Skopje 2009.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Jakim T. Petrovski: Damaging Effects of July 26, 1963 Skopje Earthquake. (PDF; 1.0 MB) Institute of Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Seismology, University “Cyril and Methodius”, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia, accessed on March 20, 2012 (English).

- ↑ Prosveta (ed.): Mala Prosvetina Enciklopedija . Third edition. 1985, ISBN 86-07-00001-2 .

- ↑ Jovan Đ. Marković: Enciklopedijski geografski leksikon Jugoslavije . Ed .: Svjetlost-Sarajevo. 1990, ISBN 86-01-02651-6 .

- ↑ Systematic list of municipalities and localities in the Republic of Macedonia. (xls; 232 kB) Statistical Office of Macedonia, accessed on March 16, 2012 (Macedonian).

- ↑ a b 2002 population census (PDF; 394 kB) Retrieved on March 5, 2012 (Macedonian, unknown language, English).

- ↑ State Statistical Bureau: Population on June 30, 2015 by municipalities. P. 14. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ↑ 2002 census, population by ethnicity, mother tongue and religion. (PDF; 2.19 MB) Retrieved November 5, 2017 (Macedonian, unknown language, English).

- ↑ Islamic Believers Association in the Republic of Macedonia ( Memento from July 9, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c A brief account of the history of Skopje. skopje.gov.mk, accessed March 11, 2012 .

- ↑ Miroslava Mirković: Native population and Roman cities in the province of Upper Moesia . In: Hildegard Temporini (ed.): Political history (provinces and marginal peoples: Latin Danube-Balkan area) . Part II (= rise and fall of the Roman world ). tape 6 . Walter de Gruyter & Co. , Berlin / New York 1977, ISBN 978-3-11-006735-4 , p. 831 .

- ^ Precious Third-Century Statue of Venus Uncovered in Macedonia. (No longer available online.) Balkantravellers.com, July 10, 2008, archived from the original on February 9, 2012 ; accessed on April 11, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Ruins of Scupi in the Republic of Macedonia. St. Louis Community College, October 20, 2005; accessed March 5, 2012 .

- ↑ http://www.aqueductskopje.net/ ( Memento from October 25, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ ТЪрновсқи патриарси. ( Tarnovo patriarchs. ). bg-patriarshia.bg, accessed March 5, 2012 (Bulgarian).

- ^ Skopje History. Retrieved March 5, 2012 .

- ^ Naser Ramadani: Islami dhe arsimi fetar në Maqedoni. Zëri Islam, December 18, 2009, accessed March 5, 2012 (Albanian).

- ↑ Hasan Kaleši (Hasan Kaleshi): Najstariji vakufski dokumenti u Jugoslaviji na arapskom Jeziku . Pristina 1972, p. 333 (One of the first founders in what is now Yugoslavia was Ishak Bey, the second governor of Skopje after Paşayiğit Bey. Ishak Bey built a mosque in Skopje called the Aladža (“Colorful”) Mosque, undoubtedly the oldest mosque in Skopje after the Meddah Mosque, a legacy of Paşayiğit Bey. Besides the mosque, Ishak Bey built a madrasah, which was one of the most famous in Rumeli under the Turkish rule. The mosque also housed a library, which is from the books donated after this Document [ie the deed of foundation] lets close ... In the area of the madrasah there were living quarters for the students because the founder donated 'eight dirhem per day for the students who live in the madrasah'. an imaret (public kitchen) is also mentioned ... Ishak Bey earned income to maintain the mosque, the madrasah and the imarets, to pay the various servants and servants s following foundations: two villages near Skopje, two hamams [baths] in Skopje, 102 shops in Skopje, two hane [inns] in Skopje, seven rural complexes including fields and gardens, a house as an apartment for the teachers.).

- ↑ Fikret Adanır: Skopje, a Balkan capital. Ed .: Harald Heppner (= Capitals in Southeastern Europe: History - Function - National Symbolism. ). Vienna 1994, p. 149–170 (Here pp. 153–154: Around the middle of the 15th century, Skopje had 5,145 residents, including 3,330 Muslims and 1,815 Christians. The Muslims - mainly Turks - came from Asia Minor; the local population was Islamized up to 16th century insignificant. Around 40 percent of Muslim and 14 percent of Christian households were in business around 1455. The boom in Balkan trade in the 16th century, aided by the Ottoman protectorate over Dubrovnik and the arrival of Sephardic Jews in the Balkans, came Skopje also benefits: with its more than 10,000 inhabitants around the middle of the 16th century (2,735 Christians, 7,425 Muslims and 265 Jews) who were active in around 80 different professions, and with its location at the junction of the trade routes from Edirne to Sarajevo and from Thessaloniki to Belgrade. Skopje was about to become a center of supraregional importance.).

- ↑ Albert Ramaj: The Rescue of the Jews in Albania. In: Albanisches Institut, St. Gallen. January 11, 2012, accessed on August 22, 2012 (PDF file, 73.6 KB).

- ^ Evliya Çelebi : travel book . (Üsküb lies to the left and right of the river Vardar [and is] a huge settlement, which is adorned with many thousands of remarkable stone buildings. It has seventy districts ... Inside the citadel there are about 100 crew houses, storehouses and armory but in the interior of the country it has only a few guns. The city has about 1060 pretty stone houses with and without upper storey, decorated from top to bottom with red bricks and well-built ... The small and large buildings and houses of prayer include the city 120 prayer niches, but Friday prayer is only held in 15 of them ... There are 9 Koran reading schools, but they do not have their own teaching room, but are attached to the mosques, where apart from memorizing the text of the Koran ... nothing else is taught Because the people there are not too keen on memorizing. There are schools (mekteb) in 70 places. There is a school near every mosque le furnished ... There are over 20 dervish monasteries (tekje). The Mewlewikloster has just been built and is in operation; it used to be the Pasha's house; by order of Melek Ahmed Pasha it became the seat of the Mewlewi. [There are also] 110 wells with running water; 200 Sebilhane (large fountains) are counted ... The baths are extraordinarily pretty ... There are free inns (mussafirhane) in seven places.

- ↑ Evliya Çelebi: Balkan Turkish Studies . Translation from Turkish to Herbert Duda. Vienna 1949, p. 19–38 (The town has market halls and bazaars, built of stone and decorated with vaults and domes, in which 2150 shops are housed. [The] alleys are cleanly paved. Each shop is filled with hyacinths, violets, roses, daffodils, basil, lilacs and decorated with lilies in jugs or boxes. When the heat is intense, the bazaars resemble the Serdab (cool summer rooms) in Baghdad, because the bazaars, like those in Sarajevo and Aleppo, are entirely built with arched vaults ... There are Armenian, Bulgarian, Serbian and Jewish places of worship. There are no such places for the Franks, Magyars and Germans. However, there are quite a few Latins [ie Catholics] who hold services in the Serbian churches ... The [Muslim] inhabitants [Skopjes] mostly speak Rumelian [-Turkish] and Albanian. They have a special dialect. They use dark and modified expressions. But they speak with a special grace ... It is really a clean city, because all the main paths are evenly paved white. There are very many notables, distinguished and distinguished people there. It is a place where poets live [and] where the poor are loved; the people there love enjoyment and joie de vivre, and love and passions belong (there too) to the possession of the lovesick heart.).

- ^ A brief account of the history of Skopje. Retrieved March 5, 2012 .

- ↑ Marlene Kurz: The sicill from Skopje. Critical edition and commentary on the only completely preserved Kadiamtsregisterband ("sicill") from Üsküb (Skopje) . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2003, ISBN 3-447-04722-4 , pp. 51 .

- ↑ Miranda Vickers: Shqiptarët - Një histori modern . Bota Shqiptare, 2008, ISBN 978-99956-11-68-2 , Vazhdimi i shpërbërjes së Perandorisë Osmane, p. 48 (English: The Albanians - A Modern History . Translated by Xhevdet Shehu).

- ↑ Васил Кънчов: Град Скопие. Бележки за неговото настояще и минало . 1898.

- ↑ Fikret Adanir: Skopje: A Balkan Capital In: Capitals in Southeastern Europe: History - Function - National Symbolism. Vienna 1990, pp. 149–169, here: p. 159.

- ↑ Thede Kahl, Izer Maksuti, Albert Ramaj: The Albanians in the Republic of Macedonia . Facts, analyzes, opinions on interethnic coexistence. In: Viennese Eastern European Studies . tape 23 . Lit Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-7000-0584-9 , ISSN 0946-7246 , Mother Teresa of Calcutta is Gonxhe Bojaxhiu from Skopje, p. 46 .

- ↑ Miranda Vickers: Shqiptarët - Një histori modern . Bota Shqiptare, 2008, ISBN 978-99956-11-68-2 , Lufta e Parë Ballkanike dhe themelimi i shtetit shqiptar , p. 110 (English: The Albanians - A Modern History . Translated by Xhevdet Shehu).

- ↑ Miranda Vickers: Shqiptarët - Një histori modern . Bota Shqiptare, 2008, ISBN 978-99956-11-68-2 , Lufta e Parë Ballkanike dhe themelimi i shtetit shqiptar , p. 113–114 (English: The Albanians - A Modern History . Translated by Xhevdet Shehu).

- ↑ Българската армия в Световната война 1915-1918 (Ed.): Войната срещу Сърбия през 1915 година. Настъплението на Втора армия в Македония . tape 3 . Sofia 1938, p. 238 .

- ^ Zoran V. Milutinović: Urbanistic Aspects of Post Earthquake Reconstruction and Renewal - Experiences of Skopje Following Earthquake of July 26, 1963. International Earthquake Symposium Kocaeli. 2007 ( kocaeli2007.kocaeli.edu.tr (PDF; 266 kB) [accessed on March 5, 2012]).

- ↑ German Embassy Skopje. Skopje '63. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on June 14, 2009 ; Retrieved March 17, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Prehistoric Kale ( Memento of April 7, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Mediaeval Kale ( Memento from April 7, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) on skopskokale.com

- ↑ Kale in the turkish period ( Memento from April 7, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Kale in XX century ( Memento from April 7, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Information board on the bridge

- ↑ Skopje Stone Bridge (15th century). de.structurae.de, accessed on March 5, 2012 .

- ↑ Ottoman Skopje Daut Pasha Hamam (today National Art Gallery). (No longer available online.) Inyourpocket.com, archived from the original on February 20, 2012 ; accessed on March 5, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Ottoman Skopje Cifte Hamam. (No longer available online.) Inyourpocket.com, archived from the original on January 4, 2010 ; accessed on March 5, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Kapan Han. (No longer available online.) Inyourpocket.com, archived from the original on March 5, 2012 ; accessed on March 5, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Kursumli Han. (No longer available online.) Inyourpocket.com, archived from the original on February 20, 2012 ; accessed on March 5, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Suli Han. (No longer available online.) Inyourpocket.com, archived from the original on January 4, 2010 ; accessed on March 5, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ St. Nikita Monastery. goruma.de, accessed on March 5, 2012 .

- ↑ The figures for the parking areas come from Google Earth .

- ↑ The founder of the identity becomes a divider. Der Standard , July 6, 2010, accessed March 5, 2012 .

- ↑ Ulf Brunnbauer : Between obstinacy and flight from reality. “Skopje 2014” as a building on the nation . In: Renovabis (ed.): Macedonia. Country on the edge of the middle of Europe . Pustet, Regensburg 2015 (= Ost-West, vol. 16, issue 1), pp. 26–35.

- ↑ “Porta Maqedonia”, Tirana notë proteste Shkupit. lajme.shqiperia.com, January 28, 2012, accessed March 6, 2012 (Albanian).

- ↑ ... споменикот на цар Самоил, потег што во Софија се толкуваше како крадење на бугарската историја .. (. No longer available online) Utrinski Vestnik, August 23, 2011 filed by the original on 27 August 2011 ; Retrieved March 5, 2012 (Macedonian). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Interview with Georgievski on the Bulgarian TV channel TV7, after a lecture at the University of Sofia , May 10, 2012

- ↑ поред него проектът "Скопие 2014" е превърнал македонската столица в "Дисниленд".

- ↑ Përleshje mes maqedonasve dhe shqiptarëve në Kala të Shkupit. (No longer available online.) Alsat-M , February 13, 2011, archived from the original on May 25, 2012 ; Retrieved March 5, 2012 (Albanian). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved March 8, 2012 .

- ↑ City Museum. Retrieved March 8, 2012 .

- ^ National Art Gallery. Retrieved March 8, 2012 .

- ^ Museum of Macedonia ( Memento of September 4, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Mother Teresa Memorial House. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on March 9, 2012 ; accessed on March 8, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Natural Science Museum ( Memento from May 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Botanical Garden Skopje ( Memento from July 28, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Macedonian Museum of Natural History ( Memento from 23 August 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Bazaar Museum. (No longer available online.) Inyourpocket.com, archived from the original on January 10, 2013 ; accessed on March 10, 2012 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ The State Archives of the Republic of Macedonia. (DOC; 84 kB) arhiv.gov.mk, accessed on March 10, 2012 (English).

- ↑ “Muzeu i Lirisë” afron Shkupin dhe Prekazin ( Memento from June 9, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ National Theater. (No longer available online.) Cee-musiktheater.at, archived from the original on June 6, 2014 ; Retrieved March 8, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Cultural Manifestation Skopje Summer 2009 Opened. skopje.gov.mk, June 22, 2009, accessed March 10, 2012 .

- ↑ Skopje Jazz Festival. Retrieved March 7, 2012 .

- ↑ Brief description of the Blues and Soul Festival. (No longer available online.) Skopjeonline.com.mk, archived from the original on August 3, 2014 ; accessed on March 10, 2012 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Macedonian, American, and European Blues in Skopje. (No longer available online.) Culture.in.mk, July 1, 2008, formerly in the original ; Retrieved on March 10, 2012 (English, report from the Dnevnik newspaper ). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ↑ May Opera Evenings Skopje ( Memento from October 23, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Skopje - What To Do. travel2macedonia.com.mk, accessed on March 10, 2012 (English).

- ^ Boris Trajkovski Sports Hall. (No longer available online.) Ehf-euro.com, archived from the original on September 6, 2011 ; accessed on March 10, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Skopje Marathon. Retrieved March 17, 2012 .

- ↑ Mandates 2009 - 2013. skopje.gov.mk, accessed on March 5, 2012 (English, Macedonian, unknown language, Albanian).

- ^ Council of the City of Skopje - Mandates 2013-2017

- ↑ a b City symbols. Retrieved March 5, 2012 .

- ^ Office for International Relations - Skopje (North Macedonia) on nuernberg.de, accessed on April 23, 2019

- ↑ Skopje Sister Cities. skopje.gov.mk, accessed March 9, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c d e Macedonian Stock Exchange. Retrieved March 10, 2012 .

- ^ Strategy for Local Economic Development of the City of Skopje. (PDF; 166 kB) Retrieved March 5, 2012 (English).

- ^ Macedonia Unemployment Rate. In: Trading Economics. Retrieved June 3, 2012 .

- ↑ Youth unemployment rates reaching epidemic proportions ( Memento from May 15, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Tutunska Banka. Retrieved February 7, 2012 .

- ↑ UNIBanka (First Investment Bank). Retrieved March 7, 2012 .

- ^ Makedonska Pošta. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on May 22, 2013 ; Retrieved March 7, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Telecom Makedonia. Retrieved March 7, 2012 .

- ^ EVN Makedonija. Retrieved March 7, 2012 .

- ^ Alkaloid Skopje. Retrieved March 10, 2012 .

- ↑ Pipeline will boost production at refinery. summitreports.com, accessed March 10, 2012 .

- ↑ Data on the international trade fairs in Skopje. (No longer available online.) Biztradeshows.com, archived from the original on March 11, 2012 ; accessed on March 10, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Угашена македонска телевизија А1. Radio-Televizija Srbije , July 31, 2011, accessed March 18, 2012 (Serbian).

- ↑ Sitel. Retrieved March 7, 2012 .

- ↑ Channel 5. Accessed March 7, 2012 .

- ↑ Press Online. Retrieved March 10, 2012 .

- ^ Second Skopje bypass highway to be put into operation. Macedonian News, July 27, 2008, accessed March 10, 2012 .

- ↑ Macedonia Capital Readies for Long-Awaited Trams :: Balkan Insight. Retrieved October 16, 2017 .

- ^ City of Skopje schools. skopje.gov.mk, accessed March 10, 2012 .

- ↑ Miladinovi Brothers City Library. Retrieved March 10, 2012 .