Thutmose III.

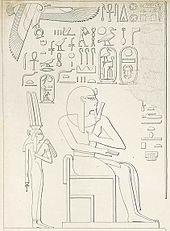

| Name of Thutmose III. | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Horus name |

K3-nḫt ḫˁj-m-W3st Strong bull that appears in Thebes |

|||||||||||||||

| Sideline |

W3ḥ-nsyt With constant royalty |

|||||||||||||||

| Gold name |

Ḏsr-ḫˁw With holy apparitions |

|||||||||||||||

| Throne name |

Mn-ḫpr (w) -Rˁ (w) The one of permanent form is the Re (on earth) |

|||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

(Djehuti mes) Ḏḥwtj msj (w) Thot is born. |

|||||||||||||||

| Greek |

Manetho variants: Josephus Mephramuthosis Africanus Misphragmuthosis (ΜισΦραγμούθωσις) Eusebius Misphragmuthosis Eusebius, A version Mispharmuthosis |

|||||||||||||||

Thutmose III. (* around 1486 BC ; † March 4, 1425 BC ) was the sixth ancient Egyptian king ( Pharaoh ) of the 18th Dynasty ( New Kingdom ). He climbed Schemu I on 4th 1479 BC. The throne and ruled until the 30th Peret III 1425 BC. Chr.

Thutmose III. came from the marriage of King Thutmose II with a concubine named Isis . The main wife of Thutmose II was Hatshepsut . Since Thutmose III. was obviously still a child when he ascended the throne, his stepmother Hatshepsut, who was also his aunt, ran the business of government. Presumably, Hatshepsut took over the throne between the 2nd and 7th year of the common government by making herself the sole ruler. Time and extent of the suppression of Thutmose III. are controversial in research. Different dated texts indicate that the rule of Hatshepsut ended at the latest in the 22nd year of reign and Thutmose III. then took over the sole rule.

The 22nd year of Thutmose III's reign. also initiated the almost annual campaigns to the Middle East . The first campaign was the so-called Battle of Megiddo against a coalition of Syrian princes led by the Prince of Kadesh . The aim of the Egyptians was on the one hand the destruction of the Middle Eastern power bases for fear of further foreign rule over Egypt (based on the rule of the Hyksos ) and on the other hand there was an economic interest in the region. Egypt benefited from rich trade goods and tributes such as labor, natural products and raw materials, which ensured the country an unprecedented level of prosperity. There were further major field battles in the 8th, 10th and 16th campaigns. The enemy was now the realm of the Mitanni . This could be enormously weakened in each case.

In addition to the Middle East, Egypt also expanded to Nubia in the early 18th dynasty , south of the 1st Nile cataract near Aswan . Thutmose III. was able to move the southern border of Egypt permanently beyond the 4th cataract and set the southern end at Gebel Barkal ("Pure Mountain") with Napata as a border town and trading base.

The kings of the 18th dynasty felt particularly close to the imperial god Amun in Karnak . Accordingly, the temple area of Amun was under Thutmose III. significantly expanded and restored. A central building in Karnak is the Ach-menu , also known simply as the “festival temple”, which he had built in the 24th year of his reign.

Thutmose III built his first mortuary temple . in Thebes-West near today's place Qurna and in the last ten years of government another one in Deir el-Bahari . The king was buried in grave KV34 - 'KV' stands for 'Kings' Valley' - which is located in a narrow rocky gorge in the southernmost wadi in the Valley of the Kings . The mummy Thutmose 'III. was later reburied in the " Cachette of Deir el-Bahari ", where it was discovered in the 1870s.

Perhaps Thutmose III continued. his son and successor Amenhotep II already in his last reign as co-regent.

Origin and family

Only a few generations before Thutmose III. the so-called Hyksos (Heka-chasut - "rulers of foreign countries"), who were probably immigrants from the Near East , ruled over a large area of Lower Egypt . Finally, at the end of the 17th dynasty , a long-established Theban dynasty , also known as the " Ahmosids ", succeeded in driving the Hyksos out of Egypt: After the kings Seqenenre and Kamose had undertaken several campaigns against the Hyksos, it was Ahmose who whose capital Auaris took and forced the Hyksos to withdraw. With this he founded the New Kingdom . It is believed that major driving forces of unification also Ahmose grandmother Tetischeri and mother after her death Ahmose Ahhotep I had.

Amenophis I , the son of Ahmose and his great royal consort Ahmose Nefertari , took over the government after Ahmose's death. Amenhotep and his mother were later deified and especially venerated during the Ramesside period as the patron saints of the necropolis workers in Set-maat, today Deir el-Medina . Amenhotep I apparently left no male heir to the throne. After him Thutmose I came to power, whose origin is unclear. He gained the right to the throne through a marriage with the princess Ahmose , a daughter of Amenophis I. With Thutmose I. the so-called Thutmosiden dynasty and with it the actual line of descent of the 18th dynasty began. The historian Manetho let the 18th dynasty begin with the unification Ahmose, but from a genealogical point of view Ahmose and Amenophis I still belong to the 17th dynasty.

Hatshepsut came from the marriage of Thutmose I and Ahmose, but the heir to the throne Thutmose II came from his marriage to the concubine Mutnofret . The half-sister Hatshepsut became the main wife of Thutmose II, presumably in order to preserve the “pure blood” and to legitimize the claim to the throne. From this marriage, among other things, the eldest daughter of the king Neferure emerged. Thutmose III. However, came from the marriage with the concubine Isis , about whose origin almost nothing is known. Isis probably came from a noble family who enjoyed good relations with the royal family, and Angelika Tulhoff assumes that she was accepted into the royal women's palace as a token of favor from the king.

The main consort of Thutmose III. entitled Great Royal Wife was Satiah , daughter of the royal nurse Ipu. From this marriage arose perhaps the first heir to the throne named Amenemhat . In the 24th year of his reign, this Amenemhat is called the eldest son of the king and, according to an inscription in the festival temple in Karnak, he was named “head of the cattle for the flock of Amun ”. At that time, Satiah was still the main consort. Other children from this marriage were a daughter named Nefertari and another son named Sa-Amun. Prince Amenemhat died between the years of reign 24 and 35.Satiah probably also died prematurely because after the 33rd year of reign she is no longer mentioned, as is probably Sa-Amun. Thutmose III. finally married the "civil" Meritre Hatshepsut and appointed her Great Royal Wife. This gave birth to the successor Amenophis II as well as the two daughters Merit-Amun and Tija. The inscription on a scarab mentions another daughter named Baket of a concubine.

A representation on a pillar in the central chamber of his grave complex ( KV34 ) also provides information about the king's female family members : In addition to the still living Queen Mother Isis, the living second main wife Meritre Hatshepsut appears behind it. Behind it appears Satiah, who is shown as " justified ", that is, deceased. Behind this is another, less important royal consort named Nebtu. She must have been a wealthy and influential woman because she had her own asset manager. The daughter Nefertari is also shown on this pillar, but she had also died at this point, as the inscription (“justified”) shows.

Three other co-wives named Manhat, Mahnta and Manawa are known from their common grave in the small Wadi Quabbabat el-Qurud in West Thebes. They could be identified as Syrian women because of their strange names written aloud . The grave complex is particularly well-known for the discovery of numerous pieces of jewelry, cosmetic containers and valuable dishes. An exact dating of the burial is not possible, although there are some indications that it was already in Thutmose III's youth. were buried. Angelika Tulhoff suspects that the three Syrians came to the court under Thutmose II and that they were succeeded by Thutmose III's successor in accordance with moral customs. were taken over.

Domination

Joint government with Hatshepsut

Accession to the throne

As a prince, Thutmose III. first training to become an Inmutef priest. This priesthood was often exercised by princes and was related to the funeral cult. After the death of his father Thutmose II , he formally came to power. Thutmose III reports on his election as king. in an inscription in the Karnak Temple from his 42nd year of reign. In it, he attributed his election to a decision of the god Amun-Re and thereby underpinned his legitimacy as a king on a religious level, as Hatshepsut had already done before him in the so-called birth myth .

“Amun, he is my father, I am his son, he commanded me to be on his throne when I was still one who is in his nest. He created me in the middle of the heart; […] [It is not a] lie; there is no untruth in it - since I was a boy when I was still a baby in his temple and my initiation as a prophet had not yet taken place [...] I was young in the appearance and shape of an Inmwtf priest, like Horus was in Chemmis . […] Re himself set me up, I was adorned with [his] crowns that were on his head. His only one dwelt on [my forehead ... I was endowed] with all his excellence, I was satiated with the excellence of the gods, like Horus, when he had claimed himself, to the temple of my father Amon-Re; I was provided with the dignities of God. "

In ancient Egyptian ideology , the state embodied a principle of order that the king established through the use of divine means of power . With the assumption of power, he re-established the state and thus restored the “divine world order” ( Maat ), which had expired with the death of the predecessor. The king obtained divine power from the sun god, who is understood as the “person of origin” of the Maat world order. Their transmission took place in the rituals of accession to the throne and coronation .

The first years of government

Since Thutmose III. was obviously still a child when he ascended the throne, his stepmother Hatshepsut, who was also his aunt, took over the affairs of state. It was common practice in ancient Egypt for the great royal wife of the late king to rule the state until the official heir to the throne was old enough to rule himself.

The autobiographical inscription in the Theban grave of the builder Ineni provides information about this situation :

“His son took his (Thutmose 'II) place as king of the two countries; he ruled on the throne of him who had created him. His (Thutmose II.) Sister, the wife of God Hatshepsut, looked after the land, the two countries lived according to their plans, and they served her while Egypt was humble; the excellent seed of the god who came out of him, the front rope of Upper Egypt, the landing stake of the southern peoples, the excellent rear rope of Lower Egypt was she, a mistress of command, whose plans were excellent; which calmed the two countries when she talked. "

Some evidence suggests that Thutmose III. officially made political decisions in the first years of government. The earliest evidence of Thutmose's reign is a visitor's inscription at the Djoser pyramid in Saqqara , which comes from a Ptahhotep from the seventh month of the new government. He highlights Thutmose's charity in Thebes without mentioning Hatshepsut.

In the second year of reign Thutmose III issued. an order to the viceroy of Kush , the temple of Semna in honor of the god Dedwen and the deified Sesostris III. to build new. This decree was depicted on the east wall of the new temple. It is of course questionable whether Thutmose himself came up with the plan for this temple, or whether the order was more likely issued in his name. It is also difficult to determine how long was the time lag between the year 2 decree and the actual placement of the text in the newly built temple. A depiction of Hatshepsut in the temple, which was later chiseled, names her as the great royal consort, but her role and attitude towards the gods is that of the temple donor, which usually falls to the king.

Another dated document is an inscription on the foundation of Senenmut in Karnak. Senenmut, who among other things held the office of asset manager, reports that the king ordered him to set up a foundation for the Amun temple. The date of the inscription has often been read as year 4, 1st Schemu, day 16, but since the first lines are damaged, other reign years have been suggested as well. The clear mention of Thutmose III. would suggest that three years after accession to the throne, official acts were carried out on his behalf. In addition to the uncertainty about the dating, the first lines were completely re-carved during the restoration of monuments that had been destroyed in the Amarna period . So it is a copy of the original text from the Ramesside period . It is no longer possible to determine whether Hatshepsut and the name of Thutmose III were not originally mentioned in the text. was rewritten about it.

Another official act of Thutmose III. is documented from his fifth year of reign when he appointed Useramun as a vizier . This replaced his aged father Ahmose Aametju in this office. The Papyrus Turin 1878 handed down the beginning of a literary representation, like Thutmose III. came personally and chose Usaramun for the office because of his excellent qualities. Another, undated version of this event is described in the inscriptions in Useramun's tomb in Thebes. Neither of these two representations is contemporary with the event. The funerary inscription was placed when Useramun was completing his burial arrangements, i.e. in the middle or towards the end of Thutmose's reign, after the death of Hatshepsut. The papyrus dates even later, certainly after the 18th dynasty.

Hatshepsut seizes power

Presumably, Hatshepsut took over the throne between the 2nd and 7th year of the common government by making herself the sole ruler. Time and extent of the suppression of Thutmose III. are, however, controversial in research. Suzanne Ratié and Wolfgang Helck speak out in favor of year 7, Donald B. Redford and Christian Cannuyer in favor of year 2 and Claire Lalouette in favor of years 5–6. In any case, Hatshepsut accepted the royal title in the year 7 at the latest .

This elevation to the male kingdom of Hatshepsut is unprecedented in Egyptian history. It initially took place through the adoption of royal titles and regalia, with the figure and clothing of a woman being retained in the representations. Various documents at this time show a mixture of hallmarks of a king and a queen in the representation. It is difficult to determine how long this intermediate stage lasted, but there was enough time to erect three monuments:

- a limestone chapel in Karnak, which was later used in the foundations of the temple of Amenhotep III. was rebuilt in Karnak-Nord

- a building that included a limestone lintel

- the southern temple of Buhen .

In this context, an inscription from the Red Chapel (Chapelle Rouge) in Karnak from the 2nd year is also important, in which Hatshepsut is announced or granted rule by an oracle of Amun. It is also significant that Thutmose II was still venerated in the Holy of Holies in the Temple of Buhen. At a later date, Hatshepsut broke all ties with her husband and emphasized her origins from her father, Thutmose I. This ideological change on the later monuments played an important role in proclaiming their royal legitimacy. For example, an inscription from the 8th pylon in Karnak says that Amun granted her accession to the throne because of the deeds performed for him by Hatshepsut's father, Thutmose I. In particular, a large cycle in the mortuary temple of Deir el-Bahari depicts the divine descent and establishment of Hatshepsut. The coronation of Hatshepsut is depicted on blocks of the Red Chapel.

The driving back of Thutmose III. by Hatshepsut was interpreted very differently in Egyptology. For example, Hatshepsut is valued as a “vain, ambitious and unscrupulous woman” who “was eager to rule, loved power and loved the young Thutmose III. pushed into the shadows ”stylized as“ angry mother-in-law ”compared to the“ vengeful nephew ”Thutmose III. Ratié even saw possible parallels to Akhenaten , due to a certain traditionalism, religious rigor, great determination and a persistent will.

In the fifth year of the reign, Hatshepsut began building her mortuary temple in Deir el-Bahari . Although this was exclusively her mortuary temple, there are depictions of the young Thutmose III in many places. in royal robes, with various crowns and when performing sacrificial acts. According to Gabriele Höber-Kamel, these representations show “that there can be no question of Thutmose III. marginalized or not considered a legitimate king by his aunt ”. Accordingly, Thutmose used his youth to grow into the royal office. In this way he was able to gain experience in the field of governance in peace.

Beginning of sole rule and possible persecution of Hatshepsut's memory

Variously dated texts indicate that Hatshepsut's rule ended in the 22nd year of the reign, although there is no reference to a specific point in time. Manetho mentions in his history that the fourth king of the 18th dynasty was a female person named Amessis who ruled for 21 years and 9 months. This reign seems very good with the beginning of the annual campaigns in the 22nd year of Thutmose III's reign. agree, which is why many historians equate Amessis with Hatshepsut and agree with the said reign.

It has also been suggested that Hatshepsut did not die in the 22nd year of reign, but merely handed over power to her now of age nephew and stepson Thutmose and continued to live in retirement for several years. The last dated evidence of Hatshepsut is the stele of the writer Night of Sinai from the 20th year of the reign. Then Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. shown in clearly parallel equality in the victim.

At a later point in time, Hatshepsut's memory was pursued: Their representations and cartouches were hacked out, their obelisks walled in Karnak and their statues smashed. The timing and reasons for this persecution are disputed in research. The most important evidence for a possible dating of this Damnatio memoriae is the Red Chapel in Karnak. Since the construction was still unfinished when Hatshepsut died, Thutmose initially completed it in his name during his sole rule. Since a fragmentary inscription in the Karnak Temple, possibly from the 42nd year of the reign, mentions the Red Chapel, this can be regarded as the earliest possible date.

Thutmose III. around this time replaced the Red Chapel with a new granite chapel. The removal of the chapel was carried out with the utmost care, as the excellent condition of the found blocks shows. The blocks of quartzite and diorite are likely to have been piled up in one of the numerous depots around the temple before they can be used again. As Dormann has shown, names and depictions of Hatshepsut were chiseled out of these piled blocks, but certainly only after the chapel was dismantled, as the deletions of the name on blocks that were previously hidden in joints show. Especially Amenhotep III. later used many of the blocks as the foundation for the 3rd pylon in Karnak.

Foreign policy

Campaigns to the Middle East

Under Thutmose II, Egypt still held the predominant position in the Near East . In Hatshepsut's time there are few mentions about Asia. Presumably, important areas of Egypt fell away during her reign, and Egypt's area of influence extended, if at all, to the southern part of Palestine .

The 22nd year of Thutmose III's reign. initiated the start of campaigns that take place almost annually. These events were mentioned in the annals of Thutmose III. in Karnak , which he recorded in his 42nd year of reign. In addition, they are handed down on steles from Napata ( Gebel Barkal ) and Armant and in the biographies of officers involved , but also toponym lists as ancillary tradition . Thutmose III was guided by this approach. in "glorious models", such as the campaigns of Sesostris III. According to Nubia : "The annual presence in the region prevents any burgeoning rebellion, and the basis for a more extensive presence can be created by means of depots and garrisons."

In the first, eighth and tenth campaigns there were real field battles , the others were probably smaller enterprises. In the first armed conflict, the enemy was still the Prince of Kadesh , in the others it was mainly the Mitanni .

The first campaign led to the battle of Megiddo . In the Middle East, a coalition of Syrian princes came together under the leadership of the Prince of Kadesh . Overall, Thutmose III. the probably more symbolic number of 330 princes and kings. According to Wolfgang Helck, Thutmose's first campaign was an "offensive defense". The deployment of the troops around the Prince of Kadesh could therefore only have had the aim of conquering Egypt. Thomas Schneider doubts, however, that it was an impending reconquest of Egypt by the great power Mitanni, in connection with the rule of the Hyksos. Francis Breyer at least notes that "after the foreign rule of the Hyksos, the need for security vis-à-vis the Near East in Egypt was obviously very great".

The opponents to the Prince of Kadesh gathered at the fortress of Megiddo . Thutmose III. decided on a risky route through the Carmel Mountains and attacked his opponents taking advantage of the surprise effect. However, these were able to withdraw into the fortress, as the Egyptians apparently began to plunder in the mention of their victory instead of smashing the enemy troops. It was only after several months of siege that the fortress could be forced to give up.

The outcome of the battle at Megiddo can be interpreted in different ways. On the one hand, it can be assumed that it was only won with great effort and that the Egyptian king therefore refrained from moving further north to Syria, even if southern Syrian places appear on the place name lists. On the other hand, assuming a preventive strike , the company was very successful: "So successful that from now on the opponent is no longer Qadeš, but Mitanni."

An Egyptian imperialism developed in the Middle East. The aim of the Egyptians was on the one hand to destroy the Middle Eastern power bases out of fear of further foreign rule over Egypt (based on the Hyksos ) and on the other hand there was an economic interest in the region. Egypt benefited from rich trade goods and tributes such as labor, natural products and raw materials, which ensured the country an unprecedented level of prosperity. In order to bond the princes more closely, their children were brought to the Egyptian royal court as political hostages, where they were trained, and if one of the princes died, his son was installed in his place as a loyal successor.

The eighth campaign in the 33rd year of the reign represented a high point in the king's military career. Thutmose advanced as far as the Euphrates in the kingdom of the Mitanni. In order to be able to move the army and supplies across the Euphrates quickly and flexibly , he had experienced Phoenician craftsmen build smaller ships that could easily be dismantled. With the help of ox carts the wooden boats could be carted over the land route from Byblos to the Euphrates. There they were put together to navigate the river. On the Euphrates built Thutmose III. a stele next to that of his grandfather Thutmose I. On the western bank of the Euphrates, the Egyptian army met the hostile Mitanni army at the fortress Karkemiš . Nothing is known about the course of the battle. In any case, the Egyptians gained the upper hand and the Mitanni fled into the hinterland. The Egyptians contented themselves with crossing and plundering the borderlands to the right and left of the Euphrates. It is said that Thutmose took part in an elephant hunt after the victory at Karkemisch. An incident occurred during the hunt in which he was seriously threatened by an elephant. The officer Amenemheb boasts in the biography of his grave ( TT85 ) that he saved the king from the life-threatening situation by cutting off the animal's trunk.

In the 35th year of reign, the Mitanni army again threatened the Egyptian empire. Thutmose and his army immediately opposed this personally. Unfortunately, some of the annals texts are badly damaged. In any case, near the Syrian city fortress Aleppo, the Egyptian army encountered the enemy troops under the command of the Mitanni king. There were probably two battles in which, according to the descriptions, the Egyptians won the upper hand without major problems. The opposing army fled back into the hinterland, and here too Thutmose III pursued. the opposing troops no further. Nothing is reported about an advance to the Euphrates. Perhaps the army was already too weakened by the great battle or the cold season had already begun.

The Mitanni made one last attempt in the 42nd year of Thutmose's reign when they allied themselves with the Prince of Tunip . Thutmose III. went by sea to the allied coastal city of Simyra . From here the army marched to Irqata to fight the Mitann troops there. The city of Irqata could be taken and with a supply of troops he advanced to Tunip. There must have been a bitter battle in which the opposing army was defeated. The last leaders were destroyed in Kadesh.

Nubia politics

In addition to the Middle East, Egypt expanded in a completely different direction in the early 18th dynasty: to Nubia, the area south of the 1st Nile cataract near Aswan . Ahmose brought the region back into his power through campaigns and introduced the new office of viceroy of Kush (also "King's son of Kush"), who was responsible for overseeing the reclaimed area, which was of particular importance to the Egyptians because of its gold mines and quarries was. In addition, a system of fortifications that had already been laid out in the 12th dynasty was restored and expanded for permanent control.

Thutmose I finally pushed far beyond the defined southern border and put an end to the kingdom of Kerma , the first significant independent Nubian kingdom. Even among his successors, the armed conflicts were not yet over. Thutmose II and Hatshepsut also intervened militarily to put down insurgents. Thutmose III. was able to expand permanently beyond the 4th cataract and set the southern end at Gebel Barkal ("Reiner Berg") with Napata as a border town and trading base.

Donald B. Redford identifies at least four military interventions in Nubia during the co-reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose. One of the few dated inscriptions shows a Nubia campaign in the 12th year of Hatshepsut / Thutmose III's reign. firmly, significantly at a time when Thutmose III. was old enough to lead the Egyptian army. This graffito in Tangur-West (between the island of Sai and the 2nd cataract) names Kush as the main enemy.

It is difficult to determine how much control Thutmose III. could exercise over the area upstream of the 4th cataract. At least the Gebel-Barkal stele, which dates to the 47th year of the reign, is an indication that he founded the city of Napata on the Gebel Barkal. The inscription could be a later elaborated speech that the king gave to high officials and people from the south. Another Nubian campaign is testified by an inscription from the 50th year on the island of Sehel, which was erected in memory of the reopening of the canal that runs through the 1st cataract when the king returned from a victorious campaign from Nubia.

Foreign trade and diplomacy

Aggressive foreign policy in the early 18th dynasty created new trading areas. Significantly, after Hatshepsut's takeover, one of the largest undertakings was the expedition to Punt . The representation of this expedition takes up a lot of space in the decoration of your mortuary temple. The wife of the "ruler" of Punt, who was characterized by an extraordinary body size, always attracts attention. The most important goods imported from Punt were incense and ebony , but other objects and animals were also brought with them.

The annals of Thutmose III. provide information not only about the campaigns to the Middle East, but also about the direct and indirect exchange of goods to Egypt. Much of the inscription lists people, animals, agricultural products, raw materials and artifacts that were brought to Egypt as gifts , tributes , spoils of war or trade goods . The diplomatic gifts included precious raw materials such as silver , lapis lazuli and other precious stones , but also copper , wood , horses , exotic animals and metal vessels. The supplying regions cannot always be identified with certainty. The kings of Hatti , Babylonia , Assyria , Alašija , Alalach and Tanaja (the Mycenaean Greek mainland or parts of it) are named as gift suppliers . The booty from the campaigns consists not only of military goods such as prisoners of war , chariots , horses and weapons, but also of a wide range of valuables, women, children and livestock that were plundered by rebellious cities as punitive measures. Most of the records, however, list tributes from the conquered areas.

For the years 33 and 38 trade expeditions to Punt were recorded. These represent a different form of the development of foreign areas. These are rare explicit evidence of actual trade as an exchange of goods in the official records. As with Hatshepsut's expedition, the ships returned with incense and other exotic goods.

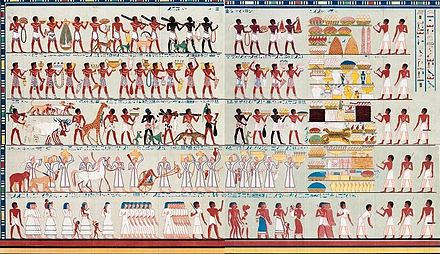

The pictorial counterpart to the annals are depictions of foreign processions in at least 15 Theban private graves from this period. These illustrate the same kind of foreign policy from an authentic, private point of view. The processions appear almost exclusively in the graves of high officials of the Egyptian administration. According to Diamantis Panagiotopoulos, the usual (modern) term “tribute scenes” is insufficient. As the visual and textual sources show, it misinterprets the real content and plays down the diversity of its subject. First, the scenes do not relate to the delivery of tributes in the strict sense, since tribute as a punitive measure never appeared in Egypt's external relations. The conquered areas were incorporated into the Egyptian administration and paid taxes like the Egyptian population. Second, they tell different ceremonial and administrative events related to the career of the tomb owner.

The best preserved example comes from the grave of the vizier Rechmire ( TT100 ) in Sheikh Abd el-Qurna . The five registers show different levels of political relations with Egypt, from free people (the top two), politically controlled (third and fourth registers) and slaves (bottom):

- 1. Register: People from punt bring incense, precious stones, ebony, ivory, animal skins and other exotic products.

- 2nd register: Mycenaeans carry elaborate metal vases, jewelry and minerals.

- 3. Register: Nubians are endowed with their typical products: gold, ebony, ostrich feathers and eggs, cattle, animal skins and wild animals.

- 4th register: residents of the Syria-Palestine region bring metal vases, weapons, a chariot, horses, minerals and ivory.

- 5th register: women and children from Nubia and Syria-Palestine. The inscription mentions that they came to Egypt as booty from the campaigns and that they were assigned to the Amun temple as slaves.

From the 15th century BC The so-called Kurustama Treaty , an intergovernmental agreement between the Egyptians and the Hittites, has come down to us . Parts of the contract have been preserved on cuneiform tablets from Hattuša , on the one hand as secondary sources in later tradition, on the other hand there is also a fragment of the original contract. It is therefore the oldest preserved parity state treaty. The contracting partners are Tudhalija I on the Hittite side and Thutmose III on the Egyptian side. or, according to the older view, Amenhotep II . In the treaty, Egyptians and Hittites regulated the consequences of the emigration of residents from Kurustama to the territory of the Egyptians. The treaty also appears to have included border regulations. It was valid until the Hittites attacked the Egyptian Amka at the end of the Egyptian 18th dynasty (approx. 1330 BC; see also Dahamunzu affair ). The city of Kurustama was probably in northern or northeastern Anatolia , but an exact location is not possible. According to Breyer, the two great powers had come so close during this time that a direct confrontation threatened, which is why they established diplomatic contacts. The Egyptians learned the cuneiform script in order to be able to communicate internationally. Even before the Amarna period, a kind of code of conduct for international relations was created. The beginning and intensifying contacts between the two cultures became tangible for the first time in the Thutmosid period: "Not only in diplomatic relations do you have to say goodbye to the beloved image of internationalization until the Amarna period - even the early Thutmosids were 'global players'. . "

administration

The king was theoretically in possession of the entirety of the land and the bureaucracy grew as a means of collecting and redistributing Egyptian products on behalf of the ruler. Much source material is provided by the biographies in the official graves , especially in Thebes West (see also list of Theban graves ). The royal service assumed a priority position: “To act for the king, to prove oneself to him, to be rewarded by him, fulfills the center of official existence so much at this time that all other points of reference in the life of an official become secondary . "

On the other hand, the transition from the rule of Thutmose III. to coregence with Hatshepsut and finally to the sole rule of Thutmose III. do not proceed without the support of key officials. The memory of the most important officials was not pursued after these crossings. A new class of officials were under Thutmose III. the veterans of the Asian campaigns. These men earned their positions in the administration through their loyalty as warriors and friends of the king.

Viziers

The highest official in the state was the so-called vizier (ancient Egyptian Tjati ). At the latest at the time of Thutmose III. the vizier was divided into two parts. There was a vizier for each of the parts of the empire Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt . Until the year 5 under Thutmose III. and Hatshepsut officiated Ahmose Aametju as vizier. His son Useramun followed him into this office. After his long term in office, his nephew Rechmire took over the office of vizier. The graves of Useramun ( TT61 and TT131 ) and Rechmire (TT100) give a good insight into the organization of the vizier's office. TT61 and TT100 deliver one of the most important documents on the Egyptian administration in its oldest text form: the instructions for the vizier . This describes the most important tasks and duties of a vizier in 27 paragraphs. According to van den Boorn, the tasks of the vizier can be summarized in three main aspects: the administration of the pr-nswt (palace), the management of the civil administration and the representation of the king.

Neferweben is the earliest documented vizier in Lower Egypt. He is known from two canopic jugs that come from Saqqara , the necropolis of Memphis . This proves that Neferweben was buried there and probably resided there. The names of Thutmose III appear on a statue of him, which means that he can be dated with certainty under this ruler. Perhaps Neferweben was the father of the vizier Rechmire, since his father was also called Neferweben, but he never bears the vizier title in the context of Rechmire.

Other senior administrators

In the early New Kingdom, the office of treasurer ( Jmj-r3-ḫtmt - Imi-ra chetemet , literally: "head of the seal") was still very influential. It included the administration of the royal income from foreign taxes and from trading ventures, the organization of expeditions and the entire palace administration. The treasurer Sennefer in particular is known for his grave complex in Theben-West ( TT99 ). The collection and distribution of grain was one of the basic organizational activities of the state. The “head of the two barns of Upper and Lower Egypt” was responsible for monitoring this activity, recording it and reporting the income to the king. Minnacht held this office until at least the year 36. His career began as a low-ranking official in the Amun temple in the north of the country at the time of Hatshepsut. His son Mencheperre-seneb succeeded him in his offices.

The heralds were authorized to speak in the king's name, just as the scribes were allowed to keep records on his behalf. You were the king's reporter and worked in a wide geographical area. Iamunedjeh was royal scribe, first royal herald, head of the guard and head of the two barns of Upper and Lower Egypt under Thutmose III. In his rock tomb in Qurna ( TT84 ) he reports on the special election by the king. As the first royal herald, he was the one “who was called at all times to carry out the plans of the two countries”. A statue from Thebes tells of the participation in Thutmose III's procession. over the Euphrates .

As high priest of Amun in Karnak, Mencheperreseneb was one of the highest officials in the religious field under Thutmose III. He also supervised the king's work in the Amun Temple and owned the two tombs TT86 and TT112 in Sheikh Abd el-Qurna . From his father's line he probably did not come from an influential family, but his mother Tajunet was a royal nurse and according to his statements he had known the king since childhood.

Puiemre held the title of Second Amun Priest and began his career under Hatshepsut. His area of responsibility included the inspection of the workshops in the Amun temple, the control and organization of various temple ceremonies and the receipt of tributes to the Amun temple. His grave TT39 in El-Chocha is of extraordinary architecture .

Educator of the royal children

In the 18th dynasty officials who looked after royal children had a great influence. The tutors were both male and female and were sometimes assigned to a group of royal children and were sometimes chosen to tutor a prince or princess.

Hatshepsut's chief architect, master builder and senior asset manager Senenmut was also responsible for bringing up her daughter Neferu-Re . Under Thutmose III. was one of those royal tutor Bener-merut . Similar to the well-known educator statues of Senenmut, the cube stool CG 42171 shows the officer with Merit-Amun, the daughter of Thutmose III. The girl's head looks up from her tutor's lap. According to his titles, Bener-merut also worked as a construction manager and in royal administration.

Military and police officers

Up until the Amarna period , high-ranking military officials were not trained in this field, but were promoted from positions that deal with registration and calculation. The decisive qualifications were therefore organizational skills and arithmetic skills, because the success of a military operation strongly depended on the organization, division of soldiers and distribution of weapons.

The most famous general of this time is Djehuti , whose military successes later found their way into the literary story of the conquest of Joppa . In particular, his cunning is appreciated. The story contains an episode that is reminiscent of Ali Baba and the Trojan Horse : the city was conquered by having Djehuti and two hundred fellow soldiers sew themselves into sacks. These were smuggled into the city without difficulty, as the local prince believed that they were gifts. During the night the soldiers crawled out of their sacks and were able to open the city gates, which led to the conquest of the city. Djehuti's tomb was probably located in Saqqara , from where some objects with his name come from.

The life of the "Colonel and Deputy of the Army" Amenemheb is well known through his autobiography in grave TT85 . Amenemheb had risen from being a soldier at the front to the highest office attainable as a non-civil servant, a colonel . At the coronation of Amenhotep II he was promoted to deputy of the army. However, this was not due to his merits, but rather the position of his wife Baki as the wet nurse of a king's child at court. The crossing of the Euphrates during Thutmose's eighth campaign is mentioned as a military high point. He was awarded the gold of honor for saving the king from the elephant hunt near Nija .

Neferchau held the office of "Colonel of the Medjau and head of the desert". The desert police ( Medjau or Medjai) guarded the desert politically and militarily. It pursued fugitives into the desert and offered expeditions protection against Bedouins. The police colonel Dedi is known from his rock grave TT200 in El-Chocha . He served himself from a simple soldier to the standard bearer of the royal guard and was finally promoted to colonel of the police in Thebes-West, a force that consisted largely of Nubians. This security force protected the valuables piled up en masse in the royal tombs and temples and the necropolis workers.

Cultic activities

As part of the traditional role of an Egyptian ruler, Thutmose III. as a mediator between man and deity. In his function as priest he was responsible for the interdependent exchange between the mortal and the divine world. His participation in the cult of gods thus guaranteed the harmony of life among the living.

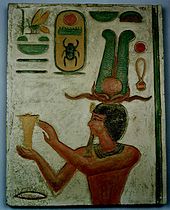

Thutmose III. however, belongs to those kings who emphasized their divine nature. During his lifetime he was also called as a parallel god to Amun in the sacrificial formula. He boasted that he was the "son" or "image" of Amun. In Nubia Thutmose III was. after the example of the deification of Sesostris III there. probably already raised to a real local deity during his lifetime, as the image of Thoth .

Sedfeste

One of the most important appearances for the king was the Sedfest . It served to renew the rule and power of the ruling king. Usually it was celebrated for the first time after 30 years of reign. In complex rituals, the king should go through a process of rejuvenation. In the Red Chapel there are already depictions of Hatshepsut performing such a festival. However, it cannot be clearly established whether such a situation has already taken place under her. There is a lack of independent confirmations for such an event, such as inscriptions on vessels whose contents were intended for a sedfest, or reports in the graves of officials about their participation in the preparations for one.

A "first time of the jubilee" in the 30th year of Thutmose's reign is mentioned on pillars of his temple in Medinet Habu . Representations in the "festival temple" (Ach menu) in Karnak also refer to the implementation of a first Sedfest. These include cult runs, which were an important part of the festival and in which the aging king demonstrated his strength. A third Sedfest mentions the Obelisk from Heliopolis, which is now in London.

Temple festivals

The execution of various temple festivals was regulated by a calendar that was drawn up under the authority of the king. At such festivals the god left his temple in the form of a cult statue and thus came into contact with his worshipers. In a procession , the priests carried the god on a processional barque .

Probably the most important and longest of the annual festivals in Thebes was the Opet festival . During this festival Amun of Karnak visited the sanctuary of the "Southern Opet" (Jp.t-rsj.t) in what is now the Luxor Temple , which was considered the place of his birth. The Opetfest also served to renew the king's divine Ka power . His ka united with that of his royal ancestors. At the height of the mystery-like rituals, the king met Amun-Re in his barge January. The god transferred the divine Ka powers to the king. Representations in the Red Chapel show Thutmose III. together with Hatshepsut for the first time in carrying out such a festival. In its sole rule it is mentioned for the first time after the return of the first Victorious Campaign to the Near East.

At the " Festival of the Beautiful Desert Valley ", Amun moved from Karnak to Thebes-West to the million year houses . These facilities served not only the cult of the deceased, but also that of the living king. At the center of the ceremonial act was the regeneration of gods and kings, the regular renewal of their physical and mental powers "for millions of years". The final destination of the procession under Hatshepsut was their million year house Djeser Djeseru in Deir el-Bahari . After the construction of his own mortuary temple in Deir-el Bahari , it should have served as the last stop at the valley festival.

Death and succession

Possible coregency of Amenhotep II.

Thutmose III reflects on a memorial stele in front of the Amun Temple near Gebel Barkal from the 47th year of reign. various aspects and achievements from his reign. It is marked by victorious memories, impressive speeches and the complete patronage of the gods. The victorious campaigns to the Middle East take up a lot of space. Further plans for the future are not mentioned and Amenhotep II appears neither as a prince nor as a coregent, which is not surprising with such a propagandistic text.

In the famous biography in the tomb of Amenemheb in Sheikh Abd el-Qurna ( TT85 ) the death of Thutmose III. and Amenhotep II's accession to the throne reports:

“The King, he completed his lifetime with many beautiful years in strength, power and justification, beginning in year 1 to year 54, 3rd month of the growing season, last day under the majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt Form of the Re ', the justified. He withdrew to heaven and united with Aton. The body of God joined him who created it.

Very early in the morning, when the sun was just rising and the sky had become bright, the king of Upper and Lower Egypt was told, 'Great are the figures of Re', the son of Re, 'Amenophis (II), God and ruler von Thebes', who was given life, bestowed his father's throne. He sat down on the throne and took possession of his rule. "

It is true that one cannot be entirely sure whether Amenhotep II's accession to the throne on the day after the death of Thutmose III. is a symbolic allusion, but there is also another date of accession to the throne of Amenhotep II, which suggests that he was installed as co-regent before Thutmose's death. In addition to the date IV Peret 1 in the biography of Amenemheb, the Semna stele of Usersatet and Papyrus British Museum name 10056 as the date of accession to the throne IV Achet 1.This raises the question of whether Amenhotep took office before or after Thutmose's death (III Peret 30) took place. The former is to be assumed, since otherwise one would have to assume a "pharaoh-free" period of two thirds of a year. Alan Gardiner interpreted the four months between Amenhotep II's accession to the throne and Thutmosis III's death. as the length of the coregency, although it is not known whether the two events occurred in the same year.

Another clue could be the question of Amenhotep II's “first victorious campaign”. The Amada stele Amenophis 'describes a first campaign in his 3rd year and the Memphis stele Amenophis' II a first campaign in the year 7. Based on the assumption of the existence of two first campaigns, Peter Der Manuelian proposes the following hypothesis: The Both campaigns cannot both be dated during the coregence or the autocracy of Amenhotep II, otherwise both would not be designated as "first". Thus, Amenhotep II is likely to have ruled as coregent at the side of his father for a few years.

funeral

With death the king allied himself with his predecessors as one of the divine fathers. The cult in his mortuary temple, which was already active during his lifetime, guaranteed his immortal existence on earth. The tomb provided the setting in which his authority among the gods was affirmed. These two components describe the role of the dead king as a force among the living and as a transcendent cosmic force.

Thutmose III. was buried in grave KV34 in the Valley of the Kings. He owned a mortuary temple in Qurna and another in Deir el-Bahari . In the 22nd Dynasty, the mummy Thutmose 'III. however, with numerous other royal mummies in the grave DB 320 (so-called cachette of Deir el-Bahari ), as this offered better protection against grave robbers. The mummy was discovered there in the 1870s. Today it is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo with the inventory number CG 61068. The 1.60 m long mummy was in poor condition and broken in three places. It was adorned with a bouquet of rushes . The shroud is inscribed with hieroglyphic texts, including the 27th chapter of the Egyptian Book of the Dead and the litany of the sun for King Thutmose III, son of Queen Isis , whose name appeared here for the first time.

Posthumous adoration

The first clear elevation of Thutmose III. to God in the private cult of the dead happened in the grave TT89 of Amenmose at the time of Amenophis III. Thutmose III is enthroned here. in a kiosk and is venerated by the grave owner. Also in tomb TT161 at night he appears as the deified king on the left side of the rear entrance, while Amenophis I and the holy Ahmose Sapair are depicted on the right side. A number of private steles from the Voramarna period and Ramessid private steles from Gurob also show the godlike status of Thutmose III. on.

Since the reign of Amenhotep III. to the Ramessid were Amenhetep I. and Thutmosis III. venerated together several times in private Theban graves . The two kings are also depicted together several times on wall reliefs in Karnak. The question arises whether Thutmose III. possibly together with his great-grandfather belonged to the patron saints of the Theban necropolis.

On three steles with demotic inscriptions from the Ptolemaic period , priestly titles contain the royal name Menech-pa-Ra (Mnḫ-p3-Rˁ) which is probably a late spelling of the throne name Mn-ḫpr (w) -Rˁ (w) by Thutmose III . acts. If so, they provide the only evidence of a cult for this king at that time.

Construction activity

Construction projects in Karnak

The kings of the 18th dynasty felt particularly close to the imperial god Amun in Karnak . Accordingly, the temple area of Amun was under Thutmose III. significantly expanded and restored.

New construction of the central barge sanctuary

The barque sanctuary around the 5th pylon, built by Hatshepsut just a few years earlier , was replaced by a new building made of black granite, divided by another small gate and a small porch was added. In the small courtyard in front of this extension, the two small "shiny golden" obelisks of Thutmose III. who stood when Thebes was conquered by the Assyrians in the 7th century BC. Were captured. On the western outer wall of the southern part of the central building, Thutmose erected a false door , a dedication inscription tells of its former decoration with gold and precious lapis lazuli . The so-called Annalensaal, which extends on the walls of the courtyard in front of the barge January and on the northern wall, is particularly interesting from an inscription. The texts engraved here in the 40th year of reign give a clear account of the king's military actions.

Reconstruction and expansion of the central sanctuary and the pillared hall

The holy area between today's 4th pylon and the festival temple Thutmose III. (Ach-menu) the Egyptians called Ipet-Sut ( jpt-swt - "place of election"). The oldest building section from the Middle Kingdom was left in its original state because of its sacred nature and the later buildings were built around this area. Thutmose III. had the portico (colonnade) laid out by Thutmose I around the central sanctuary of the Middle Kingdom removed and replaced by many small, closely spaced chapels. Statues of deceased rulers were venerated in it.

The two-part hall with columns, the so-called Wadjit, was built under Thutmose I and redesigned under Hatshepsut. Among other things, two obelisks made of rose granite came from her , one of which is still preserved in situ . Thutmose III. had all the pillars in the hall replaced by a double row of massive papyrus pillars made of sandstone. The Osiris pillars Thutmose I were surrounded with a "tongue wall" to give the impression of statuary niches. The obelisks of Hatshepsut were walled in such a way that they were no longer visible inside the building, but still towered over the temple house from the outside. Thutmose III had two more obelisks. Set up on the occasion of a sed festival directly in front of the obelisk Thutmose I at the entrance to the central sanctuary (4th pylon). These were used for the construction of the 3rd pylon by Amenophis III. away.

In the 24th year of reign Thutmose III. To the east, behind the area of the Middle Kingdom, set up the Ach-menu, also simply referred to as the “festival temple”. Its full name is Men-cheper-Ra-ach-menu, which means something like "Glorious about monuments is Men-cheper-Ra (Thutmose III)" or "Sublime is the memory of Men-cheper-Ra".

The center of the building is a large festival hall, next to it there are rooms for the cult of Amun and Sokar , a double January in which secret mysteries were held, and a higher-lying room for the sun cult that can be reached via a staircase. The sanctuary is oriented north-south, but it also takes into account the east-west axis of the main temple. Contrary to the usual arrangement for an Egyptian temple of the New Kingdom, the main entrance is at the end of a long corridor and the actual sanctuary can only be reached after a 90 ° turn via an anteroom.

The 40-meter-long festival hall is the oldest known example of a basilica building: the roof of the central nave is supported by a row of 10 columns and the surrounding aisles are supported by a total of 32 pillars. The shape of the pillars monumentally imitates the wooden poles of a tent. It is thus a marquee made of stone, which played a central role in the ritual activities of the Sed festival .

On the walls of a small chapel in the south-west corner of the hall was the so-called King's List of Karnak . On it the pharaoh stands sacrificing in front of a total of 61 seated kings. This royal pedigree is important for the historical-relative chronology.

The Ach-menu is also known as the Millennium House . It is designed in a similar way to the millions of years old on the west bank of Theban, with a sun cult site on the roof, a Sokar sanctuary and a chapel for the cult of the ancestral kings. From this point of view it is assumed that “the building was primarily dedicated to the cult of the king as a manifestation of Amun-Re”. Piotr Laskowski goes even further in his interpretation: The CG 34012 stele tells of miracles that occurred during the founding ceremony. Unexpectedly, Amun attended the ceremony and performed the founding rites. This can be understood as a sign of a perfect union between the God and the King. Thutmose III. founded the temple for Amun and was at the same time a form of Amun. Thus he founded a temple, which served the purpose of his own cult.

The "botanical garden"

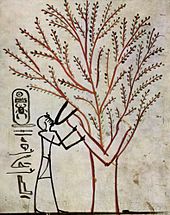

The “botanical garden” in the north-eastern part of the Ach-menu is exceptional. During the third campaign in the 25th year of reign in the Retjenu region , Thutmose III. according to the inscription "all rare plants and beautiful flowers" and also animals to donate them to the Amun temple in Karnak. It is just as extraordinary that this variety of non-Egyptian plants and animals was depicted with botanical and zoological meticulousness on the reliefs. In contrast to the usual conventions in Egyptian art, the animals, plants and parts of plants are often not represented on a base line, but freely distributed over the surface. They are presented on their own, more in the sense of a descriptive catalog than an ecological or functional integration into a scene.

Overall, Nathalie Beaux was able to identify 86% of the plant species shown and 30 of the 36 bird pictures. It remains questionable, however, whether all plants and animals were collected during a campaign or whether they did not find their way into Egyptian hands through trade or as gifts. Nor can it be said whether these were only documented on site, or whether they were actually brought to Egypt and perhaps even acclimatized . The representations in the punt hall of Hatshepsut in Deir el-Bahari show that exotic plants and animals were imported as commercial goods. The report of the exploration of Punt shows a world whose novelties are noticeably overcome.

This interest in the exotic , however, did not arise from a purely scientific curiosity. When transferring these landscape observations into the monumental context of a temple, Kai Widmaier thinks of forms of appropriation and appropriation of the exotic stranger in their own cultural contexts. Nathalie Beaux sees this as a form of symbolic extension of the boundaries, in that either the stranger that has actually been reached or unusual elements of the unknown have been incorporated into the decoration program of the temple.

Erecting the east temple

The so-called east temple is behind the Ach-menu on the east wall of the temple wall. Probably Thutmose III. remove or change an older shrine of Hatshepsut here. The small complex consists mainly of a divine shrine for Amun. Originally two obelisks from the time of Hatshepsut flanked the sanctuary. Thutmose III. commissioned another obelisk, which was not completed until Thutmose IV. It was brought to Rome in antiquity , where it has stood in the Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano and is called Obelisco Lateranense .

Extension of the north-south axis

A second axis of the temple of Amun begins in front of the 4th pylon and faces south towards the Mut district and the Luxor temple three kilometers further away. Hatshepsut had this boulevard extended with festival courtyards, station chapels and the 8th pylons, but only Thutmose III. could complete the pylon. Existing inscriptions were adapted accordingly to his government.

He had another gate area, the 7th pylon, built between the 8th and 4th pylon. A well-preserved relief scene shows Thutmose III. as a general in slaying the enemy. In front of the entrance area of the pylon there were once two colossal statues, of which the right Thutmose III. and the left the later King Ramses III. which, except for the base and remains of the foot and leg area, have been destroyed. Immediately in front of it stood two obelisks of Thutmose. The upper part of the western part was brought to Constantinople in ancient times and is now located in Istanbul's Hippodrome Square. The remains of the lower part of the eastern obelisk are still in place.

Between the 7th and 8th pylon, the architects Thutmose 'III built. in the 30th and 34th year of reign a station chapel, which served as a resting place for the cult image of Amun during solemn processions. The poorly preserved complex faced the Holy Lake .

An important part of the temple area was the rectangular, 200 × 177 meter large Holy Lake. In this, the priests performed purification ceremonies before entering the temple. The water basin was probably rebuilt and redesigned under Thutmose. This symbolizes the primordial ocean Nun , which at the beginning of time covered the entire surface of the earth and from which the sun god emerged at creation.

New building of the Ptah temple

In addition to the imperial god Amun, Ptah , the main god of the old imperial city of Memphis , owned a place of worship in Karnak. At least since the beginning of the 18th dynasty there was a small sanctuary made of adobe bricks and with wooden pillars. Already after the first campaign in the 23rd year of the reign, Thutmose ordered the construction of this building. The new stone sanctuary consisted of three connected rooms and a small hall in front of it, the roof of which was supported by two columns. It was expanded under King Shabakah and in Ptolemaic times .

Construction projects in Theben-West

The mortuary temple in Qurna

Thutmose III built the first mortuary temple. 400 meters southwest of the beginning of the path of the mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II and 300 meters northeast of the Ramesseum in Thebes-West near today's place el-Qurna . In choosing the construction site, he continued the sequence of mortuary temples to the southwest, which Amenhotep I had begun, and which subsequently continued to Medinet Habu .

It is not known exactly when Thutmose began building the mortuary temple. The earliest recorded mention is in the Red Chapel , on a black base block (No. 290). This proves that the building was built during the time of co-reign with Hatshepsut, because the Red Chapel, a barque room of Hatshepsut, was built in the 16th year of the joint government. Therein the mortuary temple of Thutmose is mentioned among the temples offering sacrifices. Accordingly, in the 16th year of the reign it was already finished and in operation in a first version.

The lack of nicknames in the name ring of most of the brick temples in the surrounding wall of the first phase of construction and the modest size of the temple also speak in favor of the start of construction in the first years of government.

Another dated mention comes from the 23rd year of the reign. In the annals of the Annals Hall in the Karnak Temple , Thutmose III mentions that the victory festival of the third Asian campaign was celebrated in the mortuary temple.

The king's nicknames on the brick temples indicate that the temple continued to be built during the time of the sole government. The Hathor Shrine appears to have been completed under the successor of Amenhotep II . The temple seems to have been extended and rebuilt, especially in the sole government. According to Ricke, because Thutmose III. did not want to make the temple appear too modest next to its huge complex in Deir el-Bahari and because it was able to expand the cult with the means of the Asian campaigns and needed more space for this development.

The mortuary temple in Deir el-Bahari

In the last ten years of reign Thutmose built another mortuary temple in Deir el-Bahari, the Djeser-achet ("Holy (from) the horizon"). The start of construction may coincide with the damnatio memoriae of Queen Hatshepsut and the associated destruction of her temple. The construction manager was Tjati Rechmire .

It was not until 1961/62 that a team of Polish archaeologists led by Kazimierz Michałowski and later by Jadwiga Lipińska discovered the temple and uncovered it in five years of excavation work.

Since Thutmose already owned a mortuary temple and the Ach-menu in Karnak is also referred to as such, it is difficult to determine the function of the temple. According to Dieter Arnold it is not a royal mortuary temple, "but rather a replacement for the chapels of the gods of the Hatshepsut temple that had been affected by the Hatshepsut persecution, especially for its Amun sanctuary and the Hathor sanctuary" . Accordingly, the temple took over the function of the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut as the last stop at the valley festival , during which the cult image of Amun was carried to Deir el-Bahari in a procession of the gods, whereby the temple of Hatshepsut lost its importance. According to Sergio Donadoni, however, the reigning king owed what Thutmose III had long had. was the honor of hosting the god overnight in his mortuary temple. According to Donadoni's interpretation, only the last stage of the valley festival was moved from the first mortuary temple Hut-henket-anch in el-Qurna to Djeser-achet in Deir el-Bahari.

The tomb in the Valley of the Kings

The grave of Thutmose is located in a narrow canyon in the southernmost wadi in the Valley of the Kings in West Thebes. It is numbered KV34 . Workers Victor Lorets , the then general director of the Egyptian antiquities administration, discovered it on February 12, 1898.

The bent shape of the floor plan and the oval coffin chamber reflect, like all early graves in the Valley of the Kings, the curved rooms of the underground beyond .

An entrance in the north leads to the first corridor and further into a "rhythmic alternation of stairs and corridors" into a first chamber with a central ramp, a second corridor and via a shaft to the trapezoidal upper pillar hall, which is in one axis Makes a bend of 72.64 degrees and leads down a staircase to the burial chamber, which in turn has four adjoining rooms. As in all tombs of the 18th Dynasty, corridors and stairwells were left without decoration.

The walls of the trapezoidal antechamber show a catalog with 741 deities (without the hostile beings) from the Amduat , which is without comparison. The figures are only drawn in outline and each supplemented with a star and a bowl of incense as well as a symbol for the Ba soul .

The 14.6 m × 8.5 m large burial chamber is rectangular with rounded corners and resembles a cartouche . The walls are decorated with the twelve night hours of the Amduat, the arrangement of which is based on the real cardinal points and the notes in the text: hours 1–4 are on the west wall, 5 and 6 on the south wall, 7 and 8 on the north wall and 9 –12 attached to the east wall. However, this ideal could not always be maintained and due to lack of space certain adjustments and omissions had to be made. The figures are painted in black and red line drawings, the texts in italic hieroglyphics, the background is in a light yellow-red tone. This creates the impression of a monumental papyrus .

Two pages of the two pillars contain a short version of the Amduat book ("The writing of the hidden chamber") as a kind of table of contents. 76 figures of the litany of the sun are shown on four sides .

Another scene on a pillar is the representation of the king with his mother Isis in a boat and accompanied by family members. In addition, an unusual and well-known scene is briefly sketched: a stylized tree extends the king's chest. It bears the caption: "He sucks on (the breast) of his mother Isis". Since Thutmose's mother was actually called Isis, the scene could ostensibly be interpreted as the return of the king to his mother and rejuvenation, but the tree suggests a goddess who otherwise grows out of the tree in the official graves as Nut or Hathor and the dead with his bird-shaped ba offers cool water and offerings. The fact that Isis is called here instead is due to the name of the earthly mother, but also to the myth according to which the king represents the role of Horus on earth and returns to the protection of his divine mother Isis, who cares for and protects him.

The royal sarcophagus is shaped like a cartouche and can still be seen in the grave. The mummy was discovered in 1881 in the cachette of Deir el-Bahari (TT320), wrapped in a shroud with the text of the sun litany .

The little temple in Medinet Habu

In Medinet Habu , the southernmost area of the Theban necropolis, there is a religiously significant sanctuary of Ur-Amun. It was considered the tomb of the Ur-Amun Kematef, where Amun of Karnak regenerated every ten days. A sanctuary called Djeser-Set (ḏsr-st) was built over a small building of the 11th dynasty during the time of coregence with Hatshepsut . This consisted of the actual sanctuary with six rooms and a barque chapel with piers in front of it.

Two rooms were only decorated during the sole rule of Thutmose: Room L, an anteroom that led to two cult rooms and in which there was a double statue made of black granite, Thutmose III. and Amun showed and room M, which Uvo Hölscher calls the king's sanctuary. The latter had no connection to the other rooms of the temple. The decoration shows Thutmose III. sitting in front of the sacrificial table and worshiped by Inmutef priests.

Thutmose's most important project was the enlargement of the barque sanctuary, to which the hall of columns planned by Hatshepsut fell victim. The new shrine was exactly the same width as its predecessor, but twice as long.

During the erection of the mortuary temple Ramses III. the small temple from the 18th dynasty was included in its wall.

Memorial temple of Thutmose II.

In the vicinity of Medinet Habu, north of the small temple, Thutmose III built. another temple. This was dedicated to the cult of the dead for Thutmose II. It is uncertain whether it is a million year house , as no inscription with such a designation has been found. However, as Luc Gabolde pointed out, Tutankhamun's millennium is almost an exact copy of this temple, so one could assume that it could actually be a millennium of Thutmose II.

The temple was built in two phases using two different types of limestone. A limestone block of Hatshepsut could indicate that the temple was built in a first phase during the reign of Hatshepsut. He may have been abandoned shortly thereafter. When Thutmose III. decided to rebuild the temple in memory of his father is difficult to say. Thutmose II certainly became an important element of the royal ideology in the course of the dishonoring of Hatshepsut.

Construction activity in Heliopolis

The place of cult of the sun in Heliopolis (Iunu) was the center of the Egyptian cult of re-cult and the pillar cult , especially the obelisk. Because of the modern use of fields and buildings, however, it is one of the least explored large sites in Egypt. Thutmose III. ordered the construction of a new pylon in Heliopolis, in front of which two obelisks about 21 meters high were erected on the third Sed festival. These were made in 13/12 BC. Brought to Alexandria in BC and placed in the Caesareum, where they were considered the " needles of Cleopatra ". One fell over in 1301 and was brought to London in 1877, the other remained upright and was transported to New York in 1880. In the 47th year of the reign, the sun temple received a new surrounding wall.

Further construction activity outside the Theban area

Thutmose's building activity outside Thebes is an important source of his royal building program and the history of his reign. Thebes was not the capital of the country in the modern sense. Heliopolis was equal to Thebes in its religious meaning. The royal residence was probably not tied to one place and the king traveled across the country. Certainly he resided in Armant, as the inscription on Iamu-nedjeh attests. There is evidence that a Harim palace existed in Gurob. The king's son was raised in Memphis. Some kind of armed resistance probably came from Peru-nefer .

The most important construction activities of Thutmose III. (from south to north) are:

- Gebel Barkal : victory stele; Beginning of the establishment of a permanent outpost

- Gebel Doscha : rock chapel

- Semna : Temple in honor of the Nubian god Dedwen and the divine Sesostris III

- Sai : fortress; Chapel and statue erected by Nehi

- Kumma : Temple for Khnum, Sesostris III. and Dedwen

- Uronarti : brick temple for Dedwen and Month in the fortress of the Middle Kingdom

- Buhen : Completion of the south temple for Horus von Buhen; Victory stele

- Ellesija : rock chapel (removed in 1966 and rebuilt in the Museo Egizio in Turin )

- Qasr Ibrim : Shrine of Nehi, viceroy of Kush

- Aniba : door jamb of Nehi's residence

- Amada : Temple for Amun-Re and Re-Harachte from the time of the co-reign of Amenhotep II.

- Quban : temple

- ad-Dakka : predecessor of the Ptolemaic-Roman temple of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III.

- Elephantine : Temple with handling of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III.

- Kom Ombo : gate

- Elkab : temple; Boat station with piers

- Esna

- at-Tud : shrine; Extension of the temple

- Armant : Pylon of the Temple of Month with African raids and killing of the rhinoceros

- Medamud : New construction of the Temple of Month

- Koptus : Harendotes Temple

- Dendera

- Abydos

- Heliopolis : gate construction and surrounding wall; two obelisks (see section Heliopolis)

- Buto : stele

- Auaris : According to Manfred Bietak , a palace district was built here in the early Thutmosid period, probably in the early reign of Thutmose III.

In addition, the inscription of Minmose in Medamut mentions temple building activities in Assiut , Atfih , Saqqara , Letopolis , Gizeh, Sachebu near Memphis, Kom el-Hisn , Busiris , Bubastis , Tell el-Balamun and Byblos.

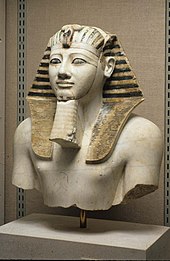

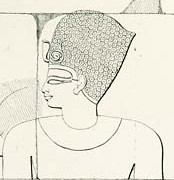

Development of the royal sculpture

It has long been recognized that the statues of Thutmose III. not always show the king with the same face. This peculiarity has often been explained with the theory that two different trends characterize the royal art of the time: an official, idealizing style based on older royal portraits and a second style based on the tradition of naturalistic portraits, even the very realistic ones Reserve heads and wooden sculptures of the Old Kingdom .

The mortuary temple in Deir el-Bahari , discovered in the 1960s , brought new finds to light that show that there was an iconographic shift in the royal portrait in the later years of the reign . Thus, the diversity of royal sculpture has to be explained at least partially from a chronological point of view - as a development process. Jadwiga Lipińska laid the basis for the study of the development of the sculpture Thutmose III. and Dimitri Laboury continued the studies.

The majority of Pharaonic sculptures were intended to be placed in a temple. The architectural context is therefore the only suitable criterion for dating. As a royal portrait, the statues of kings are at the same time the image of a man and the image of an institution, the image of the state and royalty. So one must not neglect the political and ideological dimension of the ancient Egyptian portrait of a king. According to Dimitri Laboury, the phases of royal iconography show a perfect correspondence with the political phases of the rule of Thutmose, so that the development of sculpture essentially depends on political factors.

Government year 1 to 7

At the beginning of his reign, the young king was portrayed as an adult performing his ritual duties and not in the shadow of his aunt. Statues were certainly made by him during this period, but none can be dated into them according to architectural or epigraphic criteria. Nevertheless, the analysis of two-dimensional representations helps to specify the iconography .

The figures show exactly the same physiognomy as in Thutmosis I and Thutmosis II, with a straight nose and a well-opened eye under almost horizontal eyebrows. Since Tefnin showed that the first portraits of Hatshepsut as pharaoh also depict this face, it has been clear that there was an iconographic continuity from Thutmose I until the beginning of co-government between his grandson and his daughter. The representations of the first seven years are therefore also the same as those of the last twelve.

On this stylistic basis, some sculptures could date from this period, in particular the statue RT 14/6/24/11 in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo , which comes from Karnak.

Government year 7 to 21

Hatshepsut always left space for depictions of her nephew in the two-dimensional decoration of the monuments of her reign. The fact that statues of the young king were also made at this time is evidenced in Qasr Ibrim by a group that was carved in high relief from the back wall of the third shrine and shows the king next to his ruling aunt. Unfortunately this group is totally distorted and useless to define the physiognomy of the king during this period. Furthermore, there is no architectural or epigraphic evidence that enables us to identify a statue of the young Thutmose during Hatshepsut's reign.

On the basis of stylistic comparisons with the portraits of Queen Hatshepsut, however, such statues were identified, as they shared a common iconography at least during the coregence. Some inscribed statues of Thutmose III. same portraits of Hatshepsut. This includes:

- a sphinx made of quartzite today in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (MMA 08.202.6)

- a limestone statue in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA 29.3.2)

- a statue from Karnak today in the Egyptian Museum Cairo (CG 578)

- an unlabeled head in Berlin (Berlin 3441)

These portraits and two-dimensional representations show that the official portrait of the king was heavily influenced by his aunt, but not without slightly different details.

Government year 22 to 42

At the beginning of the sole rule Thutmose III built. the Ach-menu in Karnak. Even if this important monument is badly damaged today, many of its original statues have been preserved. Some were found in the Karnak cachette (CG 42053, CG 4270-1, Luxor J 2 and possibly also CG 42060 and CG 42066 come from the Ach-menu), others were discovered by Auguste Mariette during the excavation of the area in the mid-19th century (CG 576, CG 577, CG 594, a statue at the entrance to the open-air museum in Karnak and possibly also CG 633).

These sculptures show a very homogeneous iconography, which contrasts with the royal portraits after the year 42. The face has a rounded shape with very fine modeling. This rounding is determined in particular by the lower importance of the chin, which is more integrated into the plasticity of the cheeks. The eyes appear elongated, drawn with curved lines, without angles on the upper eyelid, under high and curved eyebrows. The nose has a distinctive eagle profile with a rounded tip.

Some researchers noted similarities between the Ach-menu statues of Thutmose III. with the late portraits of Hatshepsut. Even if the physiognomic details are almost identical, there are minor differences: the protruding and low cheekbones from Thutmose's III face. determines a horizontal depression under the eye, which never occurs with Hatshepsut. The king's chin is S-shaped in profile, in contrast to his aunt's straight face, and the tip of the nose is fleshy and rounded rather than thin and pointed.

The Ach-menu statues were often viewed as a real representation of the king's face, especially CG 42053. The comparison with the mummy supports this idea. Even if the king oriented himself at the beginning of the independent rule on the iconographic model of his predecessor, the changes described are likely to be from the actual physiognomy of Thutmose III. have been inspired, as these are not documented in the sculptures of earlier kings.