Martin Luther and the Jews

The relationship between Martin Luther and Jews and Judaism is, because of its history of impact, a frequently examined topic in the history of the Church within and outside the Church . The reformer (1483–1546) adopted anti-Judaism throughout the Middle Ages and tried to underpin it with his christological Bible exegesis . In 1523 he was the first authoritative Christian theologian to demand a non-violent mission to the Jews and the social integration of Jews. Under the impression of a lack of mission success and the endangerment of the Reformation, he increasingly moved away from it from 1525. In 1543 he called on the Protestant princes to enslave or expel the Jews and renewed the anti-Jewish stereotypes that he had rejected 20 years earlier. In doing so, he passed them on to modern times .

Luther's 1523 writing was mostly considered authoritative in German Protestantism . His later "Judenschrschriften" were used several times for local actions against Jews. Anti-Semites used them from 1879 to exclude Jews. National Socialists and German Christians (DC) legitimized the state persecution of Jews, especially the November pogroms of 1938 . Large parts of the then German Evangelical Church (DEK) agreed to this persecution or remained silent about it.

Since the Holocaust , the causes and consequences of Luther's Jewish texts have been intensively researched scientifically. According to today's research consensus, they were not yet determined by racism , but by its anti-Judaist theology. However, this contributed significantly to the fact that many Protestants adopted anti-Semitism and consented or not resisted the National Socialist persecution of the Jews. Since the 1960s, many Protestant churches have publicly distanced themselves from Luther's anti-Jewish statements. Whether and how far his theology should also be revised is discussed.

Contemporary historical context

The traditional anti-Judaism

At the time of Luther, anti-Judaistic thought patterns had been widespread for a long time: God continually punished the Jews for their alleged murder of God , the crucifixion of Jesus Christ , with temple loss (70), diversion (135) and persecution. They are godless, anti-Christian, obdurate, cursed, descended from the devil , are identical with the Antichrist , regularly commit ritual murders , host sacrifices , well poisoning and secretly strived for world domination . Since around 1200, church officials have confiscated and burned the Talmud more often . Since about 1230 presented Judensau sculptures are on church buildings Jews repulsive acting body features and intimacy with pigs. Christian guilds and guilds displaced Jews despised by Christians occupations, followed by their usury attributed, aversion to work and exploitation of Christians. Since the invention of the printing press (around 1440), old and new Adversus Judaeos inflammatory pamphlets have been distributed en masse. Since the Jewish pogroms during the crusades (12th / 13th centuries) and the plague pandemic (1349), surviving Jews have been expelled from many regions of Western and Central Europe and almost 90 German cities. Imperial cities that took in displaced Jews continued to reserve certain professions for Christians, isolated Jews in many cases in ghettos and required Jewish clothing . Princes subjected them to chamber servitude and increasingly had their housing and property rights paid for with Jewish shelves . Since Judaism as a whole was considered heresy , Jews were constantly threatened with expulsion.

Jews in Luther's homeland

Around 1500 there were fewer than 40,000 Jews in the Holy Roman Empire north of the Alps (0.2 percent of the total population). They recognized their Christian rulers according to Talmudic principles, but stuck to their expectation of the Messiah and judged Christianity according to the Torah as image and idolatry . At that time, proportionally far fewer Jews lived in the Electorate of Saxony than elsewhere. Since 1536 there was a residence, purchase and moving ban for them there, which was renewed in 1543 at Luther's instigation. In Thuringia around 1540 there were only about 25 small Jewish settlements without synagogues and single families in peripheral villages.

At that time there were no Jews in Luther's residence or residence, only in Eisleben (until 1547). His few personal contacts with Jews came from them, including a meeting with two or three rabbis in 1525 , after which he reinforced his negative judgments about them. He and his wife Katharina von Bora suspected Jewish doctors of wanting to murder him. His image of the Jews was hardly determined by personal experience, but by anti-Judaistic prejudices, his interpretation of the Bible, internal Christian conflicts and religious-political goals.

Luther's knowledge of Judaism

As an Augustinian monk, Luther intensively studied the Masoretic text of the Tanach based on editions by Christian humanists . They had studied Hebrew with Jewish scholars and, with papal permission (1311), advanced Hebrew studies at Europe's universities. Because the scholasticism attacked them nonetheless as “friends of the Jews” and secret heretics, they tried to justify Hebraistic studies with anti-Jewish treatises as a debilitation of the Jewish Bible exegesis for a more successful mission to the Jews.

In 1506 Luther acquired a new Hebrew grammar from Johannes Reuchlin . In 1516 he began to translate the Book of Psalms using the Hebrew text edition by Konrad Pellikan and the grammar by Wolfgang Capito . In 1518 and 1520, at his insistence , the University of Wittenberg acquired a complete Hebrew Bible, probably the edition by Soncino (Brescia 1494). He probably also studied the then new textbooks on Hebrew grammar by Johann Böschenstein (Wittenberg 1518) and Matthäus Aurogallus (Wittenberg 1523). In 1534 the Luther Bible appeared with the complete translation of the Old Testament (OT). Thereafter, Luther did not expand his limited knowledge of Hebrew, but instead resorted to arguments from Christian Hebraists and Jewish converts such as Nikolaus von Lyra and Paulus de Santa Maria , against objections from rabbis . He emphasized that grammatical rules are formally indispensable, but should not obscure the generally understandable self-interpretation of the entire Bible and alone could not penetrate the actual meaning of the text (“what Christ does”). That is why he criticized the Latin translation of the Bible by Sebastian Munster (1534/35) , based on rabbinical exegesis, as "Judaizing" and dangerous for the Christian faith. In doing so, he adopted a stereotype that his Catholic opponents had directed against the humanists and himself.

Luther mistrusted Jewish converts who, like Böschenstein, also interpreted Jewish writings or, like Matthäus Adriani, questioned his translation of the Bible. Jakob Gipher (Bernhardus Hebraeus) got a job as a private teacher for Hebrew in Wittenberg, but not a pastor's position. Werner Eichhorn, who denounced him in several heretic trials, nourished his distrust.

Luther's basic position in the Reformation

Luther accepted the Bible as the only standard of Christian knowledge and actions (“ sola scriptura ”). For him, its center was the unconditional promise ( gospel ) of God's grace (“ sola gratia ”), which occurred exclusively in the vicarious assumption of guilt by the Son of God crucified for men (“ solus Christ ”) and solely through unconditional trust it becomes effective (“ sola fide ”). As God reveals himself in the suffering and death of Jesus Christ ( theology of the cross ), he judges all who justify themselves before God through their own efforts (“works”) as “enemies of the cross of Christ”. Because God alone wants to forgive human sin , " work righteousness " leads to damnation in spite of and against God's grace .

As the main representative of this fairness of works, Luther often listed papacy , Judaism and Islam together in early exegetical works . For him, these groups as well as the “ enthusiasts ” misused God's law for self-justification, thereby reflecting the endangerment of all believers and threatening their end-time salvation community. His criticism of self-justification was aimed first at the Christians themselves, not first at those of other faiths. From the beginning, Luther theologically classified Judaism as a “religion of law” which endangers the true faith. In contrast, his later advice on dealing politically with the Jews directly contradicted his earlier advice. Whether this change arose from his doctrine of justification or contradicted it is the decisive problem of interpretation.

Influences of the course of the Reformation

Luther's texts on Jews reflect the course of the Reformation and were part of internal Christian conflicts. Since 1520, Luther expected the sovereigns to help establish and protect a Reformation church administration without determining questions of faith ( doctrine of two regiments ). Luther's writing from 1523 reflects the departure when the evangelical teachings prevailed in many places. He wanted to enable the hitherto oppressed Jews to live together in a humane way in evangelical areas and so seemed to allow them to practice their religion freely. However, he limited this offer in time, made it dependent on the success of the Reformation and the mission to the Jews and, unlike Reuchlin, did not base the desired integration of the Jews on their Roman citizenship .

Since the inner evangelical conflict with the “enthusiasts”, Luther moved away from the principle of fighting “heretics” only with God's word. Especially since the peasant uprisings of 1525 , he expected the Protestant princes to fight “false doctrines” with state violence in order to enforce the Lutheran creed uniformly in their areas. In 1530, a Lutheran expert in Nuremberg concluded from Luther's doctrine of two regiments that the princes had to protect the religious practice of Jews, Anabaptists and Lutherans in their area and were only allowed to interfere in cases of attacks on people of different faiths. In contrast, Luther demanded in the same year that the “authorities” should punish publicly expressed false doctrines analogously to blasphemy and riot. One should not “suffer and tolerate” the Jews like Christians of other faiths, since the Jews are also excluded from opportunities for advancement and Christian professions and are not allowed to publicly blaspheme Christ.

Luther based the Reformation's claim to truth entirely on his interpretation of the Bible and tried harder than any theologian before to find scriptural proof of Jesus' messianicism. He also saw himself as an authoritative advisor to the princes on their religious policy. The more the Lutheran faith established itself in Protestant areas, while the Lutheran mission to the Jews remained unsuccessful, the more Luther believed that the Jews were maliciously stubborn. Contemporary anti-Judaist pamphlets and Christian Hebraists who questioned his Bible exegesis because of Jewish influences increased his hatred of Jews. From 1538 he tended more and more towards the final expulsion of the Jews from Protestant areas. These were supposed to enforce his writings from 1543 by taking up and tightening all anti-Jewish stereotypes of the time. A constant theological reason for this was its christological reading of the OT, which did not allow any other interpretation. Seen as a whole, the Reformation did not give the Jews a way out of the persecution of Jews in the High Middle Ages .

Luther's statements about Jews

Overview

During his entire time as a theologian (1513 to 1546), Luther dealt with Judaism in exegetical commentaries, sermons, letters, table speeches and thematic essays. The latter were classified as "Writings against Jews" as early as 1555, and in 1920 in the introduction to Volume 53 of the Weimar edition they were first named "Judenschriften". However, they were all directed to Christians, only indirectly to Jews. Luther advocated mission to the Jews without giving practical guidance. He did not write a missionary “booklet” to Jews planned until 1537. Special investigations include the following texts:

| year | title | Weimar Edition (WA) |

|---|---|---|

| 1513-1515 | First psalm reading | WA 55/1 and 55/2 |

| 1514 | Letter to Spalatin to Johannes Reuchlin | WA Letters 1, No. 7, pp. 19-30. |

| 1515-1516 | Roman epistle lecture | WA 56 |

| 1521 | Canticle of the Blessed Virgin Mary, called the Magnificat | WA 7, p. 601ff. |

| 1523 | That Jesus Christ was a born Jew | WA 11, pp. 307-336. |

| 1523 | Letter to the baptized Jew Bernhard | WA letters 3, pp. 101-104 |

| 1524 | A sermon from the Jewish Empire and the end of the world | WA 15, pp. 741-758. |

| 1526 | Four comforting psalms to the Queen of Hungary | WA 19, pp. 542-615. |

| 1530 | Letter on the liturgical organization of baptisms of Jews | WA letters 5, No. 1632, pp. 451f. |

| 1537 | To the Jew Josel | WA Letters 8, No. 3157, pp. 89-91. |

| 1538 | Against the Sabbaths to a good friend | WA 50, pp. 309-337. |

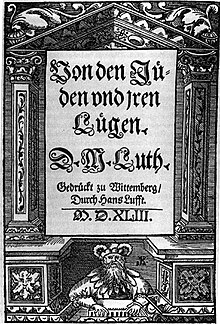

| January 1543 | About the Jews and their lies | WA 53, pp. 412-552. |

| March 1543 | Of the Shema of Hamphoras and of the family of Christ | WA 53, pp. 573-648. |

| July 1543 | From the last words of David | WA 54, pp. 16-100. |

| 1543-1546 | Sermons | WA 51, pp. 150-192 |

| 1546 | A warning against the Jews | WA 51, pp. 195f. |

First reading of the psalms (1513-1515)

In his first Wittenberg lecture, of which Luther's hand copy of the Wolfenbüttel Psalter with his handwritten notes has been handed down as a working text , Luther largely interpreted the biblical psalms as the Catholic tradition as prayers of Jesus Christ. In doing so, he equated their literal sense with God's ultimate intention, which was revealed in Christ crucified. As a result, he did not refer to the “wicked” and “enemies” in the Psalms to opponents of praying Jews but to the opponents of Jesus and his followers. He referred such verses to Jews far more often than previous interpreters. Like them, he blamed Jews for Jesus' crucifixion, but also accused them of repeating this by saying no to the Christian faith. Thus the Psalms served him for a variety of polemics against the Jews of his presence: Their interpretation of the Bible scourged and stone the prophets, as their fathers literally did; to this day they have become a “synagogue of Satan”, “blood men”, “animals” subordinated to Christians everywhere. Because they could not live out their hatred of Christians, it expressed itself in secret curses, blasphemy and slander. If the Christians would hear this, "they would destroy it completely". In this way, their hatred hits the Jews themselves at the core. God had already destroyed their Torah and synagogue through Christ and permanently excluded them from salvation. That serves as a chilling example for Christians. Luther understood the promise of Rom. 11.23 LUT fictitiously: The mass of Jews could have been saved, but actually gambled away this chance. God would only save the small remainder of the Jewish Christians who relied on the crucified Christ alone, not their works. In doing so, he intensified the theology of substitution in the early Churches on theology of the cross.

Letter to Spalatin to Johannes Reuchlin (1514)

In 1514 Luther took a position on the Cologne dispute over the burning of the Talmud with a theological report. The humanist Johannes Reuchlin rejected this in his work Augenspiegel in 1510 and assigned the Talmud a positive role in understanding the Christian faith. That is why the Cologne Dominicans under inquisitor Jakob van Hoogstraten and the Jewish convert Johannes Pfefferkorn wanted to ban his work in an inquisition process. Luther absolved Reuchlin of suspicion of heresy and criticized his opponents' zeal for persecution for two reasons: The Christians blasphemed God with their idols far more than the Jews, so that they had enough to clean up themselves. God's prophets would have prophesied the Jewish blasphemies of God and Christ. Fighting that makes the Bible and God appear to be liars. God's wrath gave the Jews "so in a rejected sense" that they were "incorrigible". Therefore God alone will overcome their rejection of Christ "from within". Luther therefore assumed real Jewish blasphemies in the Talmud, but did not try to refute them, but withdrew the Talmud from the authority of the authorities. The fact that he pleaded for Reuchlin and against the burning of the Talmud resulted from his anti-Judaistic interpretation of the Bible, not from tolerance towards Judaism.

Roman letters lecture (1515/16)

Luther's lecture on Paul's letter to the Romans already reflects the “Reformation turn”, since he understood God's righteousness (Rom 1.16f.) As a gift of grace. In it he interpreted all statements that emphasize God's faithfulness to all of Israel despite his rejection of Jesus Christ ( Rom 3,1–4 LUT ; 9,3–6 LUT ; 9.26 LUT ; 11.1.28f. LUT and more often) from his prejudice: Israel has lost its salvation privileges because of the rejection of Jesus Christ. Paul of Tarsus only reminds of past, not permanent promises of God to destroy the self-righteousness of the Jews. Luther compared them to justification based on faith as exemplary “work saints” who kept God's commandments only out of selfishness and fear of punishment. He justified this not from writings by or experiences with Jews, but only with their rejection of Jesus as Messiah, which he identified with rejection of God's grace. In addition, he often paralleled “Jews” in Romans with “Papists” so that he transferred his image of his current opponents to the Jews.

However, this should guide Christians to self-criticism and humility. Luther commented Rom 11:22 LUT : God treat the Jews so severely, "so that we learn to fear God by the example of the misfortunes of others and not be presumptuous in any way." The arrogant behavior of Christians towards the Jews contradicts this. Instead of “blasphemous abuse” and “cheekily portraying themselves as the blessed and those as the cursed”, they should “have pity” and “fear similar things for themselves”. Because God only accepted Jews and Gentiles out of “pure mercy”, “both had reason to praise God, but not to argue with one another.” This self-critical line was also represented by his sermon on the contemplation of the holy passion of Christ (1519): The crucified one reflect one's own death-worthy sin, about which the individual ("you") must be fatally frightened when looking at his suffering. Jews and Gentiles would have caused his death equally and together. They have become instruments of the grace of God realized therein. Therefore, Luther's accusation of murdering God resigned. In 1520 Luther also rejected the anti-Jewish sermons that were common at the time of the Passion, demanded a departure from them (WA V, p. 427ff.) And formulated a new Passion hymn to replace the anti-Jewish improperies of the Catholic Good Friday liturgy. It was introduced in Wittenberg in 1544, according to his anti-Jewish writings.

Rom 11.25f. However , Luther found EU ("hardening lies on a part of Israel until the Gentiles have achieved salvation in full; then all of Israel will be saved ...") "so dark" that this promise does not allow anybody from the final conversion of all Jews to Jesus Christ could convince. He remained skeptical of this promise all his life because he could not reconcile God's fidelity to the election of all of Israel with his understanding of the justification of the wicked.

Magnificat (1521)

In 1521 Luther commented on the Magnificat ( Lk 1.46–55 LUT ). In the final verse he stated: With the birth of Jesus as the son of a Jewish mother, but without the assistance of a man, God fulfilled the promise in Gen 12: 1-3 LUT : Christ was the promised “seed” (descendant) of Abraham . This promise is therefore the basis of salvation for Christians too and applies until the last day. All of Israel's biblical patriarchs and prophets had already known and taught this. The Torah was only given as an incentive to hope for the future Savior even more. But the Jews misunderstood this offer of salvation and believed that they could redeem themselves by fulfilling the law. The great majority of them are "stubborn" in this regard.

Nonetheless, Christians should treat them kindly and not despise them, since, according to the current Abrahamic promise, some Jews could recognize Christ every day: “Who would become a Christian when he sees Christians treating people in such an unchristian way? Not like that, dear Christians. Tell them the truth amicably. If you don't want to, let them go. How many are Christians who do not respect Christ, who do not even hear his words, worse than Gentiles and Jews. ”With this he advocated the renunciation of violence in the mission to the Jews. This concern carried out his following writing, which he possibly planned as early as 1521.

That Jesus Christ was a born Jew (1523)

With this writing, Luther responded to the Catholic reproach that he had denied divine procreation and thus indirectly denied the virgin birth and sonship of Jesus. He considered this reproach to be absurd and wanted to rebut it by retelling the entire biblical history of salvation to Christian opponents (Part 1) and, moreover, "to stimulate many Jews to believe in Christ" (Part 2). In this he was encouraged by the former rabbi Jakob Gipher, who was baptized in 1519 because of Luther's sermons and then taught Hebrew in Wittenberg. In 1523 he wrote to him: The rudeness of the popes and clergy had aggravated the stubbornness of the Jews; Church doctrines and customs had shown them no “sparks of light or warmth”. But since "the golden light of the gospel" shines, there is hope that many Jews like Gipher will be "carried away by their hearts to Christ". He dedicated the Latin translation of his writing to him. Their aim was to largely integrate Jews into society in order to be able to convert them more successfully.

At the beginning Luther rejected the entire previous mission to the Jews, violence and oppression of the Jews, which had resulted from the false Catholic teaching. The representatives of the papal church treated the Jews in such a way that a good Christian would have been more likely to become a Jew than a Jew a Christian. If the Jewish apostles had behaved like this to the Gentiles, no one would have become a Christian. The heathen had never met any people more hostile than the Jews. They were merely subjected to the papacy by force, treated "like dogs", insulted and robbed. Yet they are relatives of Jesus by blood, whom God has distinguished before all peoples and entrusted with the Bible. If you forbid them to work among Christians and to have fellowship with them, you drive them to rampant: “How should they mend it?” As long as they are harassed with violence, slander and accusation that they need Christian blood in order not to stink and other "foolish work" more, one could not do anything good about them. If one wants to help them, then one should practice “not the law of the Pope, but Christian love” on them, “accept them kindly”, work and let them live with Christians so that they would have the chance “to accept our Christian teaching and our lives hear and see ”. “Whether some are stubborn, what does it matter? We are not all good Christians either! "

Luther described the traditional church defamation of the Jews as ritual murderers and host molesters as “fools' work”. His criticism that Jews are treated like "dogs" referred to the designation of homeless Jews, known since late antiquity, as "stray" or "rabid dogs", with which church representatives justified their oppressed status. In 1519, Georg von der Pfalz ordered all Jews in his diocese to be completely isolated because they were “not people, but dogs”. In some Catholic areas, Jews who were accused of religious or other offenses were hung by their feet between two living dogs in order to be particularly torturous and dishonorable and to force them to convert before they died.

Then Luther tried to prove Jesus of Nazareth as the promised Messiah from the promises of the Bible. He first interpreted Gen 3,15 LUT ; Gen 22.18 LUT ; 2 Sam 7,12 LUT and Isa 7,14 LUT as prophecies of the Son of God and the virgin birth, then Gen 49,10-12 LUT , Dan 9,24-27 LUT , Hag 2,10 LUT and Zech 8,23 LUT as negative Evidence that the Jewish Messiah expectation is outdated. These passages had already been used mutatis mutandis in Patristic towards Jews. He recommended, however, that the gospel should be proclaimed in stages: one should first let the Jews recognize the man Jesus as the true Messiah; later they should be taught that Jesus is also true God, that is, overcome their prejudice that God cannot be human. He emphasized that God had honored the Jews like no other people through the gift of the Torah and prophecy and that they were closer to Christ than the Gentiles. That is why they are to be taught "neatly" from the Bible and treated as human beings. Work and guild bans as well as ghettoization should be lifted, the baseless ritual murder charges should be stopped.

Luther's practical demands were new. His theological argument, however, coincided with his earlier statements: He took it for granted that the stubbornness of the OT showed Jesus and no one else but the Christ. Only now can the liberating Gospel be heard clearly and everywhere: In Christ God unconditionally accepts all sinners, Jews as well as Gentiles. With this, Luther established solidarity between Christians and Jews in listening to the Bible together, but at the same time strictly denied any other interpretation than that presupposed by the New Testament (NT): All of the OT's promises spoke for him of Jesus Christ, yes, he spoke in it himself. The Reformation had revealed the true meaning of the Bible and its wording shows that Jesus Christ fulfilled the biblical promises. Therefore nothing more prevents the Jews from becoming Christians. In doing so, however, he projected his understanding of faith as overcoming the righteousness of works onto the entire Bible, so that Jewish self-image did not come into his view.

Luther also addressed the traditional mistrust of baptized Jews ( Marranos ) and traced the attitude of those who remained “Jews under the Christian guise” for life back to papal heresy and a lack of gospel sermon. In 1530 he instructed a Protestant pastor in a letter to be careful when baptizing a Jewish girl that she did not pretend to be Christian, as this was to be expected among Jews. In a later dinner speech to Justus Menius , Luther wanted to push a “pious” Jew who was trying to obtain baptism with flattery, rather with a stone around his neck from a bridge into the Elbe. This Luther word has been misinterpreted since the 17th century as hatred of Jews willing to be baptized, i.e. a rejection of mission to the Jews. As much as Luther only accepted Christian baptism as the spiritual and later also the worldly salvation of the Jews, he insisted on the fact that individual Jews can sincerely convert to Jesus Christ. He did not expect a conversion of all Jews, but limited the non-violent preaching of Christ in 1523 with the indication that he would later see what he had achieved.

The fact that Luther attributed the “hardening” of the Jews in 1523 to the failed mission of violence by the papal church and did not mention the fairness of work and legality of Judaism was misinterpreted as a revision of these theological views. However, Luther's anti-Judaistic thinking remained unchanged behind Luther's pro-Jewish statements. His writing increased the demands on the mission to the Jews not only to baptize Jews and thus provide them with property guarantees, but to make convinced Christians out of baptized Jews. To this end, Protestant Christians should behave in an exemplary manner in everyday life and be enabled to provide exegetical evidence from the OT. Evangelical missionary successes should show the truth of the Reformation to the papal church. This expectation contributed to Luther's later disappointment and his change of course.

Four comforting psalms to the Queen of Hungary (1526)

In 1525 Luther had his only direct argument in Wittenberg with three Jews who had asked him for a letter of recommendation. In doing so he tried to convince them of his christological interpretation of the OT. After their departure he learned that they had torn up his letter of introduction because it contained the "hanged man" ( Jesus crucified as blasphemer according to Dtn 21,23 LUT ).

Thereupon Luther interpreted the curse psalm 109 LUT as "consolation" that he related the prayer to Christ, his cursed opponent to Judas Iscariot and identified his failure with the post-Christian history of the whole of Judaism. Although they continued to exist after the temple was destroyed, they are no longer God's people. This can be seen in his loss of his own country and the unsteady existence since then. This is what happened to the enemies of Jesus Christ for 1500 years, so that reason must understand that it is cursed. But Satan does not let the Jews understand. This delusion serves the Christians as a consolation: “Help God, how often and in many countries have they played a game against Christ, about which they are burned, strangled and chased away ... But Christ and his people remain joyful in God when they are confirmed by it in their faith ... So they put on the curse in the spirit as a daily dress, so also let them wear a publicly shame on the outside so that they are recognized and despised as my enemies before all the world ... “The suffering of the Jews among the Christians is to be their cursed prove by God: With this common old church escape theory, Luther justified the Jewish costume decreed at the 4th Lateran Council in 1215 and the entire previous persecution of Christians, which he had rejected in 1523, from the Bible.

Letter to Josel von Rosheim (1537)

In 1536, Elector Johann Friedrich I forbade Jews to stay, gain employment and travel through in the Electorate of Saxony. Thereupon Josel von Rosheim , the then lawyer for the Jews in the Reich, traveled to the Saxon border and wrote to Luther asking for a meeting and to appeal to the elector for the lifting of this ban. He saw in him a possible advocate for the Jews. Luther refused on June 11, 1537: His writing from 1523 had "served all Jews a lot". But because they had "shamefully misused" his service for intolerable things, he now sees himself unable to stand up for them with the princes. Although Jesus is also a Jew and “did not harm the Jews”, they constantly blasphemed and cursed him. He therefore suspects that if they could do what they wanted, they would destroy all Christians and their property. This proves Luther's disappointment that the Reformation had hardly persuaded Jews to convert, and his changed view of the Jewish practice of religion: He now saw this as a latent threat to Christianity. Therefore, he affirmed for the first time the non-tolerance of Jews in a Protestant area. Some church historians see this as a decisive turning point in Luther's attitude towards Jews.

This was based on Luther's knowledge, which he had gained in 1532, of the Christian Sabbaths in Moravia , who kept the Sabbath instead of Sunday . He attributed this to Jewish influence and saw it as evidence of Jewish " proselyte-making " among Christians. This disappointed him immeasurably, also because it seemed to confirm Catholics who had accused him that the evangelical tolerance of the Jews would only increase their hostility to Christianity. Imperial and princely Jewish regulations strictly forbade Jews from proselytizing Christians and otherwise threatened to withdraw legal protection. But the Reformation had strengthened messianic hopes in Judaism for an early redemption and return to the promised land of Israel ( David Reuveni ). His Torah observation also radiated into some groups of the Anabaptist movement. Luther's fear of evangelical areas turning away from his conception of faith was therefore not unfounded. The Confessio Augustana of 1530 also fended off “Jewish teachings” (CA 17) and a feared or “deliberately stylized” Jewish counter-mission.

Against the Sabbaths (1538)

Luther issued this work as a private letter "to a good friend" in order to hide the origin of his information and to make it difficult to replicate it. He claimed that in Moravia the Jews had already circumcised many Christians and led them to believe that the Messiah had not yet come. These Christians who converted to Judaism committed themselves to observing the entire Torah. However, this is impossible because of the destruction of the temple in 70 AD . In order to be able to keep the Torah, the Jews would first have to rebuild the Jerusalem Temple , recapture the Land of Israel and make the Torah a general state law there. Then all proselytes would have to move there too. One should wait and see whether that happens; if not, the ridiculousness of their attempts to get Christians to keep the Torah, which has been "rotten" for 1,500 years, is proven.

The "Sabbaths" themselves only appeared marginally in Luther's writing. Knowing them since 1532, he probably knew that they had no contact with Jews. The church historian Thomas Kaufmann therefore assumes that Luther used these very small and politically ineffective groups as a pretext to claim alleged Jewish proselytization and to demand the expulsion of the Jews from Moravia.

Of the Jews and Their Lies (January 1543)

Luther named a dialogue script directed against his Sabbath script as the occasion for this writing, in which a Jew tried to refute the belief of an "absent" Christian by reinterpreting passages in the Bible. This was possibly Sebastian Munster's work Messias Christianorum et Judaeorum Hebriace & Latine (1539), which unfolds the rabbinical idea of the messiah , talmudic and cabbalistic exegesis and contrasts it with only Christianly interpreted OT passages. Luther declared at the beginning that he no longer wanted to convert the Jews because that was impossible. Experience shows that disputations and learning their Bible exegesis only strengthened them in their faith and in “luring Christians to themselves”. He just wanted to “strengthen our faith and warn the weak Christians against the Jews” and prove to them the “senseless folly” of the Jewish faith in the Messiah. The NT is sufficient for this. The rabbis' “damned glossing ” (false interpretation) should be rejected. A purely philological Bible exegesis misses the actual task of presenting the OT testimony to Christ. Luther explained this in the first part in contrast to Münster's dialogue script.

He first described the "arrogance" of the Jews of today: They considered themselves to be God's people because of their descent, circumcision , Torah, land and temple ownership, although they, like all human beings, are sinners under God's wrath (I). With five AT points he then tried, similar to 1523, to prove Jesus' messiahship (II), described Jewish polemics against him and the Christians (III) and deduced practical measures from this (IV). Already in the beginning he allowed the stereotypes of the time to flow into it: Jews are bloodthirsty, vengeful, the most greedy people, real devils, stubborn. Their "damned rabbis" seduced the Christian youth against their better judgment to turn away from the true faith. Several times Luther accused the Jews of poisoning wells and robbing and dismembering children like Simon of Trent . These legends, which he had rejected as “fools' work” 20 years earlier, he has now underpinned with an NT quotation (Mt 12:34). They would do good out of selfishness, not love, because they would have to live with Christians, with the result:

"Yes, they keep us imprisoned in our own country, they let us work in sweat, win money and goods, meanwhile sit behind the stove, lazing around, pomping and frying pears, eating, drinking, living gently and well on the goods we have earned, have caught us and our goods by their accursed usury, mock and spit on us that we work and they let lazy Juncker be [...] so our masters, we their servants. "

With this, Luther appealed to the social envy of the population and demagogically reversed the real situation of the "chamber servants" at the time in order to end their tolerance for protection payments to the princes. To this end, he demanded of these seven steps, which he cynically called "sharp mercy ", later openly referred to as "ruthlessness":

- to burn down their synagogues,

- destroy their houses and let them live like gypsies in stables and barns,

- to take away their prayer books and Talmudim, which anyway only taught idolatry,

- to forbid their rabbis from teaching under threat of the death penalty ,

- to deprive their traders of safe conduct and right of way,

- to forbid them from "usury" (money business), to confiscate and store all their cash and jewelry,

- to give the young vigorous Jews tools for physical labor and to let them earn their bread.

But although he would like to strangle Jews himself, Christians are forbidden to curse them and attack them personally. The authorities that God set up to ward off evil must protect Christians from the “devilish” Jews. If the princes refused his advice, they would at least have to forbid the Jews from their religious sites, services, books and their blasphemy. If this cannot be carried out either, the only thing left is to chase the Jews out of the Protestant countries “like mad dogs”.

With this brutal appeal for violence, Luther denied the Jews the human dignity that he had granted them in 1523. His comparison of the Jews with "Gypsies" was an early modern stereotype. The Roma were 1,498 throughout the Holy Roman Empire for outlaws declared because they like the Jews (the spies of the "Turks" Muslims in the expanding Ottoman Empire ) were suspected. Luther was familiar with this Reichstag resolution, so he called for the Jews to be disenfranchised and extradited. The Catholic lawyer Ulrich Zasius had already demanded in 1506 that Jews should be expelled or "eliminated" because they cursed Christians daily, exploited them with usury, refused to serve them, ridiculed the Christian faith and blasphemed against Christ. The cruelest is the daily and nightly “blood thirst” of these “bloodsuckers”. He concluded: “So why should the princes above all not be allowed to cast out such outspoken enemies, such fierce beasts, why not drive them out of the territories of the Christians? One must let that most disgusting sputum sink into miserable darkness. Even if this endless mob of circumcised Christians is no longer tolerated, there will still be many of these monsters who can hang around among the heathen. "

Luther also claimed here that he had not previously known that the Jews in their schools and synagogues “lie, blaspheme, curse, spit and desecrate Christ and us.” This referred to the “prayer crime” that the Jewish convert Antonius Margaritha 1530 as the alleged main feature of Jewish religious practice. His influential text "The whole Jewish faith" was presented as a compendium of Judaism to warn Christians of alleged anti-Christian practices of the Jews and to convince them that any protective rights are a dangerous illusion for them. Any tolerance only strengthens their presumptuous awareness of election and leads to the enslavement of Christians and their rulers. Only forced labor can bring the Jews to the knowledge of the wrath of God and Jesus Christ lying on them. This is done out of “mercy”, so that in the misery of the Jews their divine rejection may also remain visible for Christians of all peoples until the end of the world. Luther adopted this line of argument right down to the choice of words. He instructed the evangelical pastors and preachers to follow his advice regardless of the behavior of the authorities, to warn their congregations against any contact with Jews and any neighborhood help for them, to constantly remind their governments of their "God owed" task, the Jews to work to force them to forbid the taking of interest and to prevent them from all criticism of Christianity. He himself demanded that his anti-Jewish writings be passed on and constantly updated.

This was due to the failure of his previous exegetical argumentation and a “ pressure to migrate ”: Elector Friedrich had temporarily lifted the travel ban for Jews in 1539. In 1541 they were expelled from Bohemia to the neighboring regions. Margaritha's and Münster's writings also encouraged Luther to view the Jews as active enemies of Christianity. Thereupon he wanted to persuade all evangelical princes with all rhetorical means to expel the Jews and destroy their economic and religious livelihoods in order to force them to convert. This was supposed to show God that Christians did not knowingly tolerate and were not complicit in the alleged lies and blasphemies of the Jews of which he was convinced. Luther wanted to avert God's feared punishment and save his Reformation, which he then saw threatened from all sides. His other anti-Jewish texts from 1543 also pursued this goal. How much his imminent expectation of the final judgment played a role is controversial. Luther saw his presence as the last onslaught of the devil who wanted to destroy Christianity through the enemies of the Protestant faith. However, he justified the expulsion of the Jews here with the threat from the Turks at the time, which he distinguished from the final judgment. He saw the main danger in the rabbinical interpretation of the OT promises of the Messiah, which he wanted to make permanently impossible.

From the Shem of Hamphoras (March 1543)

With the work Vom Schem Hamphoras , Luther published the Toledot Jeschu, which he translated into German, based on a Latin version that had already been edited in an anti-Judaist manner. This Jewish legend, compiled from Talmudic passages, portrayed Jesus as a magician and illegitimately conceived changeling who had misused the divine name YHWH (circumscribed as Ha-Shem Ha-Mephorasch : “the most holy, executed name”) as a magical formula and therefore failed. Luther got to know this text through Antonius Margaritha and made it known in German-speaking countries in order to prove the allegedly blasphemous hostility towards Christ of all Jews, which he saw in their sanctification of the Name of God. He ridiculed this Jewish tradition and the Jewish Bible exegesis to the utmost: He described it as obtained from the excrement of Judas Iscariot, took up the Wittenberg Judensau sculpture, called Jews "these devils" and thus put Jews, Judas, excrement, pigs and devil pictorially alike His vulgar language reached a maximum sharpness even in the coarse style of abuse and insult that was customary at the time.

Luther also expressed an early modern, long-term conspiracy theory : Jews were a “basic soup of all loose, bad boys from all over the world” and “like the perpetrators and gypsies” ( Tatars and Roma or non-residents) banded together around the Christian Scouting out and betraying countries, poisoning water, stealing children and deviously causing all kinds of damage. Like the assassins, they committed assassinations of Christian rulers in order to then take their territories.

Admonition Against the Jews (February 15, 1546)

In January 1546 Luther traveled to Count Albrecht VII von Mansfeld in order to enforce the expulsion of the Jews from his territory with sermons. After their expulsion from Magdeburg (1493) they were admitted to Eisleben; the Mansfeld counts argued about how to deal with them. On February 15, after his last sermon three days before his death, Luther read his “Admonition”, which summarized his attitude towards Jews like a legacy:

- He wanted to treat the Jews in a Christian way and offered them to accept Jesus of Nazareth as their Messiah, who was their blood relative and legitimate descendant of Abraham. Christians should make this offer of baptism "so that one can see that they are serious."

- The Jews would refuse the offer and "blaspheme and desecrate our Lord Jesus Christ every day," seek Christians for "body, life, honor and property," harm them with usurious interest, and would like to kill them all if they could, and would do so , "Especially those who pretend to be doctors". Even if they seem to cure the disease first, they would only "seal" artfully so that you would later die of it.

- If the Christians were to knowingly tolerate the Jews, they would be complicit in their crimes: Therefore "you masters shall not suffer them, but drive them away."

- “But wherever they convert, let their usury be and accept Christ, we will gladly keep them as our brothers. Otherwise nothing will come of it ... They are our public enemies. "

Luther therefore only gave the Jews the choice between baptism or expulsion. Since he could not wait for them to be baptized, he deprived them of any right to exist in Protestant areas. He justified this disenfranchisement with the collective intention to murder, which he had first imputed to them in 1537 and which he considered real.

reception

16th Century

Luther's “Judenschriften” were only a small part of his work, but at that time they were among the most widely read texts on the subject of Jews. That Jesus Christ was a born Jew appeared in ten German and three Latin editions, Vom Schem Hamphoras in seven, the remaining writings on Jews in two German and one Latin editions.

Luther's 1523 writing was a sensation for Jews at the time. Dutch Jews sent them to the persecuted Jews of Spain as encouragement. Others sent him a German translation of Psalm 130 in Hebrew as a thank you. In 1524 Abraham Farissol pointed a popular Messiah prophecy to Luther: God had saved him from his opponents, he had weakened their faith, and since then Christians have been benevolent and welcoming to Jews. Because of his Hebrew studies and his disgust for the Catholic clergy, he was probably a secret Jew who was gradually returning to Judaism. Because the Reformation heralded the imminent arrival of the Messiah, Jews forcibly baptized should quickly resume their faith. An anonymous rabbi interpreted Luther's name as “light” and emphasized that the Reformation abolition of monasticism , asceticism , celibacy and fasting had brought Christians and Jews closer together. In 1553, Samuel Usque suggested that Marranos secretly instigated Lutheranism. God split Christianity so that forcibly baptized Jews could find their way back to Judaism. Joseph ha-Kohen welcomed Luther's interpretation of the Bible in 1554 as a rational contribution to abolish “abuses of Rome” such as indulgences and to improve Christian life. God let the Protestants triumph over the overwhelming Catholic power and liberated their country like Israel did earlier. Kohen listed the Lutheran martyrs and mourned them according to Jewish liturgy. Rabbi Abraham Ibn Megas also welcomed in 1585 that the Reformation had split Christianity into many doctrines. May God gradually purify Christians from their sins against the Jews through their religious wars .

Other Jews soon recognized Luther's change of course. An anonymous writer wrote around 1539 that Luther first tried to convert the Jews and then slandered them when there was no success and other Christians mocked him as an almost Israelite. After his unsuccessful attempt at contact, Josel von Rosheim tried to push back Luther's influence on the Jewish orders of the Reich. In 1543 he asked the city council of Strasbourg to forbid Luther's writing On the Jews and their Lies : Never before had “a highly learned man imposed such a grossly inhuman book of reproach and vice on us poor Jews, from which, God knows, in our faith and In fact, nothing can be found in our Jewishness. ”The Strasbourg city council forbade the printing of Luther's writings from 1543, but in 1570 allowed other anti-Jewish books and graphics.

Luther's writing of 1523 was also considered a turning point in Lutheranism . By 1529, seven Protestant pamphlets reacted to it. The pre-Reformation Epistola Rabbi Samuelis explained the 1000-year exile of all Jews with biblical passages like Am 2,6 EU as God's persistent judgment for the sale of the righteous Jew Jesus and the persecution of his apostles. Because of this argument, which was only related to the OT, Lutherans translated this writing as an aid to their mission to the Jews. Three fictional dialogues between a Christian and a Jew illustrated the new approach to Jews suggested by Luther. They did not contain any anti-Jewish invectives, argued only from the OT, named Jewish counter-arguments and described mutual respect between the dialogue partners, even if they remained divided. The first text of the dialogue rejected Jewish hopes for a kingdom of their own, which had strengthened rumors of unknown Jewish armies in front of Jerusalem. The second ended with, and the third without, the conversion of the Jew, but concluded that Judaism would last until the return of Christ. Accordingly, the “friendly” mission to the Jews failed because of the Reformation interpretation of the OT, which excluded the post-biblical rabbinical tradition, and because of Jewish end-time hopes. Luther's friend and translator Justus Jonas the Elder said: It was only the Reformation that rediscovered the value of the people of Israel and their Bible. The Jews could know Jesus Christ from the stubbornness of OT. That is why the Church must work incessantly for her salvation. Luther had for the first time proven exegetically that the Messiah had already come and that the Talmud was just as useless as Catholic scholasticism. That is why Christians should pray for the Jews, especially since they too often only call themselves Christians. Jonas held on to this hope of conversion in 1543, even after Luther had given it up.

From 1543 onwards, some Protestant territorial lords partly followed Luther's demands. Electoral Saxony renewed and tightened the travel and residence ban for Jews. In 1546 Braunschweig and other cities expelled the local Jews. Some Protestant universities banned Jewish physicians as a result of Luther's stereotype of them. In 1547 the Count von Mansfeld drove out the Jews of Eisleben. Landgrave Philipp von Hessen ordered the burning of the Talmud and forbade Jews to take interest, but could not enforce this.

Most of the evangelical princes ignored Luther's demands of 1543 to keep Jewish protection money and economic benefits. Most of the reformers did not follow him either, although they too regarded Judaism as an outdated, hostile religion of the law. Only Philipp Melanchthon disseminated Luther's 1543 writings as “useful teaching”. Wolfgang Capito, on the other hand, supported Josel von Rosheim's attempt to lift the passage ban in Saxony. Heinrich Bullinger criticized that Luther's writings from 1543 were “distorted and desecrated by his filthy abuses and by the scurrility that no one, least of all an elderly theologian, deserves.” Even an unknown author would have “little excuse” for “porky, stinky Schemhamphoras” ". He advocated a verbatim AT exegesis, since otherwise the NT would also become implausible. Anton Corvinus and Caspar Güttel held fast to the solidarity of the common guilt of Jews and Christians before God. Urbanus Rhegius strove for a non-violent mission to the Jews in his region. Martin Bucer and Ambrosius Blarer demanded strict servitude instead of expulsion of the Jews. Huldrych Zwingli described them as deliberate spoilers of writing and direct originators of Catholic rites and wars. This had no political consequences, as there were hardly any Jews in his region. Andreas Osiander named the financial indebtedness of Christians as the cause of many pogroms against the Jews. In 1529 he was the only reformer to exegetically refute the ritual murder charge against Jews. But this remained virulent in Protestantism because Luther had again declared Jewish ritual murders to be probable in 1543.

In his edition of the Luther Sermons in 1566, Johannes Mathesius denied any change in Luther's Jewish texts and created a narrative of the betrayal of the Jews against him. Since 1523 he had cleared the OT of the "Rabbis Geschmeiß und Unflath" and helped Jews, but they had betrayed him and tried to continue to murder. Most Luther biographies followed these guidelines up to 1917. With his inflammatory pamphlet "Judenfeind" (1570), Georg Nigrinus tied in with Luther's aggressive polemics of 1543 and also claimed a Jewish host sacrilege, which was punishable by the death penalty according to the Embarrassing Neck Court Code of 1532. Landgrave Wilhelm IV. (Hessen-Kassel) recommended in a letter to his brother Ludwig IV. (Hessen-Marburg) to collect the "bad work" only copied by others. In 1577, Nikolaus Selnecker , co-author of the concord formula , published Luther's “Judenschriften” from 1538 and an anonymously compiled list of “terrible blasphemies” of the Jews as a book for Protestant housefathers and commented: Because the economic behavior of baptized and unbaptized Jews is so bad, they are just as little like "the devil and his mother himself" to tolerate. They are particularly dangerous enemies of the Lutherans, as they have risen socially everywhere, while the true doctrine has "suffered a horrible shipwreck." In 1578, the Braunschweig expert Martin Chemnitz declared that the expulsion of the Jews was a "religious matter" concerning conscience and that the local clergy were responsible for this. They recommended their colleagues in Einbeck to follow Luther's demand. Because the Jews already denied Jesus' messianship by their very existence and thus blasphemed him and the Christians, they were to be treated in exactly the same way as "sacramenters" and sects . The protection of the Jews endangers the uniform enforcement of the Confessio Augustana . So it was now seen as a departure from dogmatized Lutheranism, for which Luther's late writings were authoritative. Often the stereotype of the Jewish "prayer crime" was decisive in evangelical areas to drive out Jews. According to Friedrich Battenberg, the main reason for this was the religious-political strengthening of the princes with the principle of cuius regio, eius religio in the Augsburg imperial and religious peace (1555). This enabled them to unify their territories confessionally and to tolerate or expel the Jews depending on their interests. Thus Luther did not pass on medieval anti-Judaism seamlessly into the modern age, but initiated a long-term tendency towards radicalization.

Luther's Catholic opponents used his texts against him. Petrus Sylvius blamed him for the Turkish invasion of Europe in 1527 and claimed that Luther had also encouraged the Jews to subjugate and murder Christians and to devastate their cities and countries. Johannes Eck accused the "Jewish father" Luther of making everyone into priests, even the Jews, and had caused Osiander's rebuttal of the ritual murder accusation as well as Anabaptist iconoclasts and "sacramental desecrators" ("Ains Judenbüchlein Verlassung", 1541). Some Catholics and Protestants, including Luther himself, insinuated that their opponents were descended from Jews in order to discredit their teachings. This is where the transition from anti-Judaistic to anti-Semitic prejudice began. In 1543, Johannes Cochläus found that although Luther had reviled the Catholics and flattered the Jews, he had not converted any Jews to Christ, but only incited their hatred of Christians. He only mentioned Luther's 1543 writing in the margin, probably because its allegations against Jews coincided with Catholic tradition. In 1595 Emperor Rudolph II had this writing confiscated as a “shameless book of shame” at the request of the Jewish communities. On the other hand, the Catholic Church dogmatized its anti-Judaistic teachings and renewed its ghettoization and labeling laws in order to distance itself from the Protestant side.

17th and 18th centuries

In the 17th century Protestants tied in with either the "early" or the "late" Luther and accordingly treated Jews differently. Luther's texts from 1543 were reprinted and used in 1613 and 1617 for the anti-Jewish Fettmilch uprising in Frankfurt am Main, and also in 1697 in Hamburg for the expropriation of local Jews. The Jena theological faculty justified limited tolerance for Jews to be converted in 1611 in an expert opinion for the Hamburg magistrate with Luther's writing from 1523. The Reformed Hebraist Johann Buxtorf the Elder, on the other hand, referred to Luther's first writing from 1543 in his influential writing Juden Schul in 1641 proves their interdenominational effect.

The Lutheran orthodoxy rejected the Jewish mission from futile. Theologians such as Johann Conrad Dannhauer and Johann Arndt interpreted Israel's "hardening" following Luther's late writings as the final rejection of all Jews up to the final judgment. They often called for sharper repression of Jews as part of church reforms. Johann Georg Neumann emphasized that from 1526 Luther had consistently represented the irrevocable hardening of Judaism and rejected its conversion.

The pietism however, called for the mission to the Jews as a necessary part of the international mission. Johann Georg Dorsche and Philipp Jacob Spener indicated Röm 11,25f LUT ("... all Israel will be saved") on a future conversion of all Jews before the final judgment. From 1678 Spener took a sermon quotation from Luther from 1521 ("God grant that the time is near, as we hope") to claim, which was missing in Luther's house postil. Its first editor, Caspar Cruciger the Elder , probably left it out in 1547 because Luther again limited “all of Israel” in 1543 to the Jewish Christians who had been converted before the year 70. Spener criticized this interpretation as a time-related and theologically insignificant falsification and included the version from 1521 in the new editions of the house postil. In doing so he made Luther the key witness of the mission to the Jews; From then on, he left no mention of his later statements to the contrary. In a Frankfurt sermon published in 1685, Spener demanded, referring to Luther's early Jewish writings: “And as our dear Lutherus thought about it / we should love all Jews for the sake of some Jews / so we should also all their families for the sake of this one of the most noble Jews of Jesus respect ”. The Protestant church historian Johannes Wallmann interprets this as an implicit criticism of Luther's later anti-Jewish writings and evaluates this sermon by Spener as the beginning of real tolerance towards Jews in Germany. In 1699 , Gottfried Arnold recalled Luther's writings from 1543, but emphasized that only the early Luther was binding on the attitude towards the Jews. This view shaped the Protestant image of Luther well into the 20th century.

19th century

In 1781, the enlightener Christian Konrad Wilhelm von Dohm initiated a debate about Jewish emancipation and mentioned Luther's 1543 writing as an example of the intolerance that had to be overcome. Because the National Assembly of France granted the country's Jews equal civil rights in 1791 , this has been discussed in Prussia since the victory over Napoleon Bonaparte and the Congress of Vienna (1815). In an early anti-Semitic polemic from 1816, the historian Friedrich Rühs demonstrated the “complete incompatibility” of Judaism and Christianity with anti-Semitic quotations from Luther. The Baden Oberkirchenrat Johann Ludwig Ewald then condemned these quotes as "completely anti-Christian, inhuman blasphemies" that contradict Jesus' message and that one should "rather cover with the cloak of love". The attitude of the Protestant churches in the German Confederation corresponded to this . In contrast, educated early anti-Semites around Ernst Moritz Arndt , Friedrich Ludwig Jahn and Jakob Friedrich Fries stylized Luther as the pioneer of Germanism and the German nation-state . Their supporters in the student fraternities reaffirmed these demands at the Wartburg Festival for the 300th anniversary of the Reformation in October 1817 with a book burning that also included an anti-nationalist work by the Jewish scholar Saul Ascher . The pogrom-like Hep-Hep riots followed in 1819 .

These representatives of "political Protestantism" knew Luther's Jewish texts, but did not take over his radical demands of 1543. In 1822, the anti-Semite Hartwig von Hundt-Radowsky only mentioned one speech by Luther in his Jewish school . The Leipzig theologian Ludwig Fischer tried in 1838 with a collection of quotes from Luther's Jewish texts with anti-Jewish commentary to prove that today's Jews are irreconcilable, but that the eschatological conversion of all Jews should be recorded. That is why he rejected their oppression as well as their complete emancipation. The representatives of confessional Lutheranism also rejected complete Jewish emancipation. Friedrich Julius Stahl and Ernst Wilhelm Hengstenberg did not refer to Luther for their model of a Prussian-Christian state. In 1857, Hengstenberg declared as the conclusion of his series of articles: Luther's late writings on Jews contradicted the apostles' attitude that the Lutheran Church had never adopted them unchecked. At that time this attitude was represented by all directions of Protestant theology.

From the establishment of the German Empire in 1871 until Luther's 400th birthday in 1883, nationalist Protestants like Heinrich von Treitschke captured Luther politically under the slogan “From Luther to Bismarck ”. Treitschke took his anti-Semitic motto "The Jews are our misfortune" and the comparison of (German) "host people" and (Jewish) "guest people" from Luther quotes. Luther's writing from 1523 remained authoritative for the Protestant Church; his late writings were considered incompatible with Paul and Reformation theology. Even moderate anti-Semites like Adolf Stoecker did not refer to it. The later Luther researcher Georg Buchwald, however, encouraged Protestant theologians in 1881 to sign the anti-Semite petition with a commented new edition of Luther's Jewish texts .

From 1879 onwards, anti-Semites represented a racist interpretation of Luther, which they based exclusively on his late writings. Islebiensis (pseudonym) claimed in 1879: Luther recognized in 1543 that the “ Jewish question ” could not be resolved with baptism, but only with the expulsion of the Jews: “'Get out with them' should also be our call, which we call all genuine Judge Germans. " Theodor Fritsch declared in 1883: The" German Luther "was in 1543 with the" sharpest weapons "against the" Jewish world enemy ", the" dishonorable foreigners ", the worldwide cooperative" criminal cooperative ", the" nation of traitors to humanity " proceeded. Fritsch declared Jesus to be an Aryan who had defeated the God of OT. Houston Stewart Chamberlain saw Luther as a nationalist hero who created the German nation against Rome's "Jewishized" church system. He saw his theology as a weak point. The final battle of the chosen divine Aryans or Germanic peoples against the devilish Jews is still to come and can only end with the annihilation of one by the other.

Jewish intellectuals reacted contradictingly to the increasing ethnic and racist appropriation of Luther. Johann Salomo Semler , Heinrich Heine (1834), Leopold Zunz (1855), Hermann Cohen (1880ff.) And others idealized Luther as the conqueror of the Middle Ages, heroes of intellectual freedom and pioneer of tolerance. They ignored Luther's anti-Jewish statements (according to Isaak Markus Jost 1828) or downplayed them as insignificant (according to Samuel Holdheim 1858, Emil Gustav Hirsch 1883). Ludwig Börne, on the other hand, criticized Luther in 1830 as the ancestor of political bondage and a German spirit of submission. Heinrich Graetz (1866) explained Luther's return to anti-Jewish “fairy tales” out of personal bitterness, righteousness and a lack of understanding of the ethical quality of Judaism. Luther's anti-Jewish “Testament” (1543) had long “poisoned” the Protestant world. Ludwig Geiger (1860ff.) Explained this writing more on the basis of Luther's knowledge of the contrast between his and the Jewish Bible exegesis. With the thesis of a break in Luther's attitude towards Jews, these historians tried to save Luther from anti-Semitic abuse and to strengthen an alliance of Jews and Protestants for spiritual and social progress. In doing so, however, they were hardly heard by the Protestants, as they continually made concessions to the anti-Semites on the basis of anti-Judaism.

1900 to 1933

Some Protestant theologians reacted to the anti-Semitism of the 1880s with a double strategy: in 1913, Ludwig Lemme demanded “sharp mercy” politically with reference to Luther, namely the expropriation and disenfranchisement of the supposedly dominant Judaism, and at the same time “heartfelt charity ” towards individual Jews, for them aggressively to convert. It can be assumed that all Jews have been cursed since Jesus' crucifixion. The Zionism should be rejected because it promotes only the "blindness" of the Jews against the Jewish mission. If Christians were really Christians, there would be no more Jews. Wilhelm Walther (1912) called Luther's AT interpretation and his 1523 writing "pro-Semitic". He was always concerned with the relationship between the Jews and their Savior Jesus Christ. Its outbreak of 1543 should be ignored, since modernity has been hostile to Christianity since 1789 and has given the Jews the equality with the Christians, which Luther rejected, and generalized the "Jewish business spirit" which was previously considered unbearable. The question is whether these results of tolerance are more favorable. In the Russian October Revolution of 1917, Jews murdered Christians. In doing so, he adopted the anti-Semitic cliché of the Jewish masterminds of this revolution and suggested that Luther's “tolerant” attitude of 1523 was a mistake with grave consequences. Ernst Schaeffer wanted to arm the Christians in 1917 with the memory of Luther's writing of 1523 for a coming, "self-confident" confrontation with the "corrosive, unexpectedly vital Reform Judaism and thereby avoid the" mistake "of the late Luther, who adopted and anti-Judaist" lies " so that I overlooked the more modern varieties of Judaism.

The Weimar Constitution of 1919 gave Jews the same civil rights as Christians, making academic collaboration possible. At the same time, anti-Semitism with anti-republic right parties increased enormously. Völkisch authors opened a public debate about the OT and Luther's Jewish writings in the 1920s. In 1921, for example, Alfred Falb doubted the Jewishness of Jesus against Luther and thus supported the Assyrologist Friedrich Delitzsch , who in 1920 had suggested an "Aryan" origin of Jesus. With indulgences Luther fought “against the intrusion of the Jewish spirit into the church” and in 1543 recognized the “expulsion of Jews” as “an unconditional self-defense measure of a plundered people”, but not yet separated the Christian from the Jewish God. What is now required is the elimination of the "germ spoilers" and "invaded bacteria", as requested by Paul de Lagarde and Eugen Dühring . Artur Dinter called Jesus Christ in 1926 the "greatest anti-Semite of all time" who could not have been a Jew. He called for a “completion of the Reformation” and consequent “de-Judaization” of the “doctrine of the Savior” by separating it from the “Jewish-Roman forgery” of the OT and Paul. Luther is no longer an authority for this because of his ties to the OT. In 1926/27 Max Wundt described the "Judaization" of German culture and "decomposition" of "German blood" as a current form of the murder of God. The " Germanness " is the chosen people who have to continue Luther's fight against Judaism for their own survival. In 1931, Karl-Otto von der Bach published the text "Luther as an enemy of Jews". In it, like Falb, with anti-Jewish quotations from Luther, he asserted a “national significance of the Reformation” against the “Jewish plague”. The young Luther did not know any Jews; It was only the "mature" Luther who began to hate them for national and religious reasons. His “far-sighted warning” is currently to be followed. These views became common property in the ethnic and racist part of Protestantism.

At the 1923 NSDAP party congress, Adolf Hitler stylized Luther as the model of the Führer principle for the planned Hitler coup : at that time he dared to fight “a world of enemies” without any support. This risk distinguishes a real heroic statesman and dictator. In his pamphlet Mein Kampf , written in 1924/25 in prison , Hitler mentioned Luther as a “great reformer” alongside Friedrich the Great and Richard Wagner , but sharply criticized intra-Christian denominational struggles as a dangerous distraction from the “common enemy”, the Jews. From 1923 onwards, the NSDAP newspaper Der Stürmer often used selected isolated quotations from the NT and from Christian authors, including Luther, for his anti-Semitic agitation. In 1928, the paper presented Luther's late Jewish texts as “far too little known”. After the fight against Rome, through personal experiences with Jews, he recognized the task of freeing the Germans from the “Jewish plague”. Similarly, Mathilde Ludendorff from the Tannenbergbund claimed in a series of articles in 1928 that Luther had studied the “Jewish secret goals” after 1523 and revealed them in 1543 in order to begin a “second Reformation” against the Jews. This could have saved the Germans 400 years of suffering, but the Evangelical Church had "withheld Luther's texts from the people". The publishing house of Ludendorffs Volkswarte published Luther's writings on Jews. As a result, the Inner Mission Dresden published all of Luther's writings on Jews in excerpts in 1931. Editor Georg Buchwald left out all of Luther's passages on the interpretation of the OT from the text Von den Juden und their lies . These special editions were published several times until 1933.

On the other hand, Eduard Lamparter declared in 1928 for the Association for the Defense against Anti-Semitism : Luther had been taken into party politics as the “key witness of modern anti-Semitism”. However, in 1523 "at the height of his Reformation work for the oppressed, despised and ostracized in such warm words" he "put charity so urgently to Christianity as the most important duty, also towards the Jews". Prominent Protestant theologians recommended that all pastors read out the declaration as the authoritative position of the Protestant church: anti-Semitism is a sin against Christ and incompatible with the Christian faith. Pastor Hermann Steinlein (Inner Mission Nuremberg) declared against Ludendorff in 1929: Luther was not an infallible authority. Wilhelm Walther defended the OT and Luther's interpretation of the OT as a Christian heritage, but agreed with the anti-Semites that they could appeal to Luther for their fight against current Judaism. Like him, Old Testament scholars like Gerhard Kittel separated the biblical Israelites from current Judaism, legitimized the mission to the Jews from the OT and spread Lutheran anti-Judaism by using Judaism as a law of the law irreconcilable with Christianity, its dispersion and alienation as God's permanent judgment and the state alone for Jews represented responsible. These thought patterns, typical of the Luther Renaissance , contributed significantly to the fact that the Evangelical Church did not resist the persecution of the Jews from 1933 onwards.

In contrast to the efforts of ethnic theologians, the NSDAP ideologue Alfred Rosenberg criticized Luther in his work The Myth of the 20th Century in 1930 : Although he broke the ground for the “Germanic will for freedom”, with his translation of the OT he essentially contributed to the “Judgment” of the German people contributed.

Nazi era

The German Evangelical Church Federation welcomed the " seizure of power " by the Nazi regime (January 30, 1933) with great enthusiasm. Representatives such as Otto Dibelius praised the elimination of the Weimar Constitution as a “new Reformation” on the day of Potsdam (March 21, 1933), stylized Hitler as the God-sent savior of the German people, paralleled his and Luther's biographies and constructed one directed against human rights , democracy and liberalism historical continuity from Luther to Hitler. Initially, however, only a few National Socialists, such as Karl Grunsky, compared Luther's hostility to Jews with Hitler's anti-Semitism.

Luther's Jewish texts were frequently reissued during the Nazi era. The National Socialist propaganda used them as well as the racist DC and their opponents within the church. From 1933 onwards, the “Stürmer” claimed that Luther's “downright fanatical struggle against Judaism” was “hushed up” in more recent church history works. As a good person, he first tried to convert Jews, then realized that mission was in vain because “the Jew ... the born destroyer” was, and “enlightened” the German people about it. In 1937 and 1938, two articles affirmed that Luther had to be considered a “relentless and ruthless anti-Semite” and that the evangelical pastors had to preach this much more strongly. In 1941, the paper rejected the view that Luther's late Jewish texts were a return to the Middle Ages, old-age mood or purely theologically motivated. In 1943, the editor Julius Streicher declared Luther's AT translation and writing from 1523 as a result of church education, from which he then turned away. He recognized that Christ could have nothing in common with the “Jewish murderer people” and therefore demanded their expulsion. He spoke as a warning to the present: “The criminal people of the Jews must be destroyed so that the devil may die and God live.” Consequently, Streicher defended himself against the main war criminals at the Nuremberg Trial in 1946 : “Dr. Martin Luther would be sitting in the dock in my place today, if his writing from 1543 were taken into account. In it he wrote that "the Jews were bred by snakes, their synagogues should be burned down, they should be destroyed".

In November 1937, at the “recitation evening” in the Residenztheater (Munich) for the propaganda exhibition “ The Eternal Jew ”, excerpts from Luther's writings were read out first. The “German Reading Book for Elementary Schools” from 1943 presented anti-Jewish quotes from “great Germans”, including Luther, under the title “The Jew, our arch enemy”. The “History Book for Higher Schools” (7th grade: “Führer und Völker”) from 1941 commented on Luther quotes from 1543: “Nobody before and after him has fought the Jews, these 'incarnate devils', with such elementary force as he ...” .

Since April 1933, the DC Luther used for their struggle for a conformist Jewish Christians and "Entjudung" of the Church's message, "Reich Church" exclusion. The “Bund für Deutsche Kirche” claimed in September 1933: The DEK, which was “ready to be demolished”, had refused to implement Luther's demands of 1543, had always stood apart when the “healthy German spirit” against “Jewish rape” and thus “complete degeneration and moral decay ”. Now one must stand up with Luther as a “loud shouter against the enemies of our people”, abolish the OT and put “German intellectual property” in its place. At the nationwide “ Luther Day” (November 19, 1933), theologians not belonging to the DC, such as Paul Althaus , portrayed Luther and Hitler as related heroes of a “great national turnaround” and ancestors of the German people . The respected Luther researcher Erich Vogelsang emphasized against the Jewish Historian Reinhold Lewin : Luther recognized that the whole of Jewish history since Jesus' crucifixion has been determined by God's curse. Jewish emancipation was a futile attempt to escape from this fate. Only after 150 years did the “German Revolution” of 1933 make it clear again that the Jews were “the visible God's finger of anger in human history”. Therefore, the church must in no way grant Judaism a divine right to exist, but must, like Luther, "fight everything 'Judaizing' and 'Judaism'" as "inner disintegration through the Jewish way" and the state to "take action" with "sharp mercy" prompt. Luther recognized the danger of exploitation and enslavement of the "host people" by the Jewish "guest people" and their expulsion as the only realistic solution. Although he had not yet seen “racial mixing” as a problem, he did see a degeneration of the Jews (“watery blood”) through their symbiosis with weak Christians, which had intensified their hatred of Christians. He did not worry about a corresponding dilution of German blood through Jewish "admixture", since he had rejected the mission to the Jews. The “clean separation” of Jews and Christians emerges from his late writing Vom Schem Hamphoras .

Because of these attacks, the völkisch-nationalist Jewish missionary Walter Holsten Luther's writings against Jews and Muslims were reissued in 1936 and 1938 and commented: One must distinguish the “old, right-wing Jews” from the “new, foreign Jews or bastards”. Luther connected the latter to the devil because of their religious decision against Christ. He also adhered to the mission to the Jews in 1543 and therefore asked the authorities to execute God's wrath against the Jews, behind which his “infinite love” is hidden. Therefore, the church must now allow “certain political treatment” of the Jews and exercise “sharp mercy” in its own area. The literary historian Walther Linden titled his 1936 edition “Luther's campaign writings against Judaism” and called it the “ethnic and religious creed of the great German reformer that is still fully valid today”. The theology lecturer Wolf Meyer-Erlach (DC) published excerpts from Luther's writings in 1937 with the title “Jews, Monks and Luther”. He became the main representative of a “de-Judgment of the Bible” at the Eisenach “ Institute for Research and Elimination of the Jewish Influence on German Church Life ”, founded in 1939 .