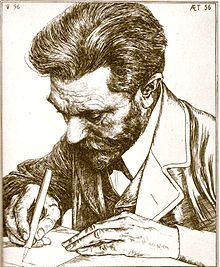

August Bebel

Ferdinand August Bebel (born February 22, 1840 in Deutz near Cologne, † August 13, 1913 in Passugg , Switzerland ) was a socialist German politician and publicist . He was one of the founders of German social democracy and is still considered to be one of its outstanding historical personalities. He was one of the most important parliamentarians in the time of the German Empire and also emerged as an influential author. Its popularity was reflected in the popular names "Kaiser Bebel", "Gegenkaiser" or "Arbeiterkaiser".

His political beginnings were rooted in the liberal-democratic association of workers and craftsmen before he turned to Marxism . August Bebel worked with Wilhelm Liebknecht for decades . With him he founded the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP) in 1869 . In 1875 he was involved in the union with the General German Workers 'Association (ADAV) to form the Socialist Workers' Party of Germany (SAP) . From 1867 to 1881 and 1883 until his death, Bebel was a member of the Reichstag of the North German Confederation and the Empire, and during the repression of the party through the Socialist Law, he developed into the central figure of German social democracy. From 1892 he was alongside Paul Singer and Hugo Haase, until his death, one of the two chairmen of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) , as the SAP called itself after the law was repealed. In the following years he represented the so-called Marxist center of the SPD between a left and a “ revisionist ” wing .

Life

Childhood and youth

Bebel was born in poor circumstances as the son of NCO Johann Gottlob Bebel and his wife Wilhelmine Johanna Bebel (née Simon) in the casemates of fortress Deutz . After the early death of his father, who succumbed to pulmonary tuberculosis in 1844 at the age of 35 , his mother married his twin brother, who worked as a supervisor in the Provincial Correctional Institute ( work house ) in Brauweiler . However, the stepfather also died after two years. Since the widowed mother had no pension entitlement, she moved impoverished to her family in Wetzlar , where August attended elementary school. He was gifted and took math lessons from an outside school teacher.

The mother died in 1853. She left her children with a few small, scattered parcels of land around Wetzlar. The two brothers who were still alive came to their mother's relatives. To ensure the brothers' livelihoods, they received financial and material support from an orphan fund . Later, in his will, Bebel bequeathed him 6000 marks out of gratitude. Due to the difficult financial circumstances, Bebel had to give up hope of studying mining. From 1854 to 1857 he learned the woodworking trade in Wetzlar without any real inclination . Despite the hard work, he tried to educate himself by reading.

After completing his apprenticeship, Bebel began his journeyman hike in 1858 . It initially led through southwest Germany to Freiburg im Breisgau. Further stations were Regensburg, Munich and Salzburg. In Freiburg he had already joined the local Catholic journeymen's association , which at that time also accepted Protestants. He also took part in club life in Salzburg, attracted by the newspapers and training opportunities available.

When the Sardinian War broke out in 1859 , as he wrote in his autobiography, Bebel volunteered with the Tyrolean hunters out of a "thirst for adventure" , but was turned away as a non-Tyrolean. His attempt to join the Prussian Army became irrelevant because peace had meanwhile been made. In later trials, Bebel was always put on hold because of his weak constitution. In 1860 he returned to Wetzlar via several stations. He couldn't find work there and moved on to Saxony .

Beginnings of political action

From civil associations to workers' associations

In Leipzig he quickly found work in a larger workshop. Because of bad food he persuaded the other journeymen to protest. Because Master gave in, the planned strike did not take place.

At that time the city was a center of associations for workers and craftsmen. Liberal and democratic bourgeois circles supported their educational efforts. On the one hand they wanted to increase the professional opportunities of workers and craftsmen, on the other hand it was a matter of binding these groups to liberalism. In February 1861, at the suggestion of the Polytechnic Society and some liberals, the Gewerbliche Bildungsverein was founded, which Bebel also joined in the same year. A number of personalities from the early labor movement emerged from this association . In addition to Bebel, these included Friedrich Wilhelm Fritzsche , Otto Dammer and Julius Vahlteich . In 1862 Bebel was second and from 1865 to 1872 first chairman of the industrial education association.

Bebel still saw himself as a craftsman and was aiming for the position of master. He had achieved this goal in 1864 by opening his own workshop in the courtyard of the Drei Könige house in Petersstrasse , where he also lived. He raised the necessary capital by selling the family's small property in Wetzlar. In the first few years the company was still very small. At first he only employed an apprentice and a journeyman. He tried not to exploit his employees like other entrepreneurs and paid them more wages with fewer working hours than usual.

Bebel took full advantage of the educational association's range of lectures and courses. In 1862 he became a member of the board of directors of the educational association as well as head of the association library and the entertainment department. Politically, he was initially still opposed to efforts to increase the independence of the workers. The attempt of Julius Vahlteich and Friedrich Wilhelm Fritzsche to turn the association into a political organization, Bebel opposed in 1862 and advocated the exclusion of these members. They then formed the forward association .

In the fall of 1862, preparations began for the establishment of a supra-regional German Workers' Day. Bebel was a member of the preparatory committee. He was opposed to the demands of the cooperative socialist Ferdinand Lassalle for a general, equal, direct and secret right to vote because he did not consider the workers to be politically mature enough.

The establishment of the ADAV in May 1863 was perceived as a threat by the liberal associations in the workers' association movement. As a reaction to this, they convened the Association of German Workers' Associations (VDAV) in Frankfurt am Main in June and formed an umbrella organization. Bebel was present as the Leipzig delegate.

Shortly before that, the industrial educational association in Leipzig had separated from the Polytechnic Society . After it was united with the Vorwärts association , it was reconstituted as a workers' association . Bebel first took on the position of deputy chairman and finally that of chairman. In 1864, Bebel was the meeting leader of the second VDAV Association Day, which took place in Leipzig. There he was elected deputy chairman of the umbrella organization.

Turning to socialism

A political change of direction began to take place at Bebel. Although he remained a staunch opponent of Lassalle, he began to read his writings intensively and gradually approached Marxism.

“In the constant battle with the Lassalleans, I had to read Lassalle's writings to know what they wanted, and with that a change soon took place in me. [...] Like almost everyone who became socialists at the time, I came to Marx through Lassalle. Lassalle's writings were in our hands even before we knew a work by Marx and Engels. "

Social conflicts also strengthened Bebel's doubts as to whether the workers' close ties to liberalism would continue to make sense. The contact with the philosopher and social politician Friedrich Albert Lange in the leadership of the VDAV played a role . Bebel was a mediator in a book printers 'strike and was involved in founding a miners' union . The organization was involved in a strike with supporters of Lassalle.

Turning away from bourgeois democracy towards socialism did not cost Bebel any “great spiritual battles” according to his account. Even if personal relationships were destroyed in the process, he accepted this because he was convinced of his changed point of view. The meeting with Wilhelm Liebknecht, who came to Leipzig in 1865, strengthened him in this. Liebknecht had belonged to the circles around Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in London . Even if not uncritically, Bebel followed Liebknecht's ideas in many ways. From Liebknecht, Bebel accepted the basic thesis that the political and social struggle of the workers was a unit. Therefore, the workers' associations would have to break away from the liberals. In his autobiography, however, Bebel rejected the assumption that Liebknecht had made him a socialist. Rather, he was already on the way when Liebknecht came into his life.

Bebel was critical of the fact that Liebknecht created a fait accompli without prior discussion. Because Liebknecht lacked practical skills, others had to carry out the measures later. Nevertheless, both were regarded as the "inseparable", and a friendly relationship developed from the mere cooperation.

Saxon People's Party

Bebel also adopted Liebknecht's anti-Prussian stance. When the German war was imminent in 1866 , Bebel criticized Otto von Bismarck's small German policy at a large popular assembly and spoke out in favor of the greater German side .

On August 19, 1866, together with Wilhelm Liebknecht, he founded the radical democratic Saxon People's Party . Despite his now strongly socialist attitude, Bebel and Liebknecht wanted to bring about an alliance of workers and Greater German and worker-friendly bourgeois forces against the Prussian domination in the emerging North German Confederation .

In the same year August Bebel married the plasterer Julie Otto . She supported him in his increased dedication to politics, although he still had to work as a master craftsman during this time. In addition to his duties in associations and the party, he now also took on journalistic activities. He wrote for the German Workers' Hall , a sheet of the VDAV, as well as for the Democratic Weekly Paper published by Liebknecht , the organ of the Saxon and the German People's Party (DtVP) .

From Eisenach to Gotha

Foundation of the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP)

In 1866, Bebel had joined the socialist International Workers' Association (IAA) , which had been founded in London two years earlier. Later historiography also spoke of the First International. Bebel promoted the objectives and organizational ideas of the IAA within the workers' associations. At the VDAV Association Day in Gera in 1867 , he was able to enforce a regular board in place of the standing committee. In the election of the chairman, he won more votes than his opponent Max Hirsch . Bebel was President of the VDAV from 1867 to 1869. At the VDAV Association Day in Nuremberg a year later, it was mainly due to Bebel that the Association joined the First International. He advocated the adoption of the International's program "because it sets out the demands of the workers with sharpness and clarity and because a standard is required for the workers of the entire civilized world." This led to the separation of the liberal and bourgeois democrats.

As a union arm of a new labor movement alongside and in competition with the ADAV, which goes back to Lassalle, and the liberal Hirsch-Duncker trade associations , Bebel - supported by Liebknecht - founded a number of international trade unions for various groups of workers and drafted a model statute for them.

The resolutions of the Nuremberg VDAV Association Day and the development of the ADAV were an important step on the way to a new workers' party. The leadership style of long-time ADAV President Johann Baptist von Schweitzer , which many described as dictatorial, contributed to the fact that numerous members moved to the Bebel and Liebknecht camp. The tone of the very polemical arguments intensified between the two sides.

On August 8, 1869, at the party congress in Eisenach, the VDAV, former members of the ADAV and the Saxon People's Party, headed by Bebel, formed the SDAP. Bebel was the most important organizer at the Eisenach founding party convention, at which the Eisenach program was adopted as the founding program of the SDAP, and had shaped the unification negotiations together with Liebknecht in advance. In contrast to the ADAV, the new party was structured democratically. Admittedly joining the IAA was not possible for legal reasons, but Bebel emphasized that the new party supported the International in all points, both ideally and materially. He could not prevail on the name question. In order to keep the still existing democratic bourgeoisie, he suggested the designation “Democratic Socialist Party”, but failed.

In the following years he campaigned as a speaker and as an author for the new party. His brochure Our Goals , published at the beginning of 1870 and reprinted many times, was particularly effective . In it he took the concept of the working class very broadly. In addition to wage workers, this includes small craftsmen, but also small farmers , elementary school teachers and lower civil servants. Since these groups together made up the vast majority of the population, after the victory of the working class there could be no talk of class rule, rather a “reasonable democratic society” was sought. The cooperative mode of production should take the place of private property . With regard to the form of social transition, Bebel did not rule out a violent revolution during this period . In addition, the text contained demands for the emancipation of women. Despite his membership in the International, Bebel was sometimes far removed from the positions of Marx and Engels. Because of his political activities he came back to court and was sentenced to three weeks in prison in Leipzig.

Reichstag member

Bebel was elected to the constituent Reichstag in February 1867 . In the Saxon constituency of Glauchau- Meerane , he won against the Lassallean Friedrich Wilhelm Fritzsche. Bebel was also a member of the first ordinary Reichstag and the later Reichstag until 1881, then again from 1883 until his death in 1913. He represented constituency 17 of the Kingdom of Saxony (Glauchau, Meerane, Hohenstein-Ernstthal ) until 1877. He then represented a constituency of Dresden until 1881 , from 1883 to 1893 the constituency of Hamburg I ( Neustadt , St. Pauli ), from 1893 to 1898 the constituency 8 of Alsace-Lorraine ( Strasbourg -stadt) and again from 1898 until his death Hamburg constituency I.

Despite all the similarities, there were considerable differences between Bebel and Liebknecht in the assessment of parliamentary work during this period. Liebknecht refused to "make pacts and parliaments". He saw parliament as a mere political propaganda tool. Bebel, on the other hand, saw the Reichstag as an instrument for improving the situation of the workers. He took an active part in the debates, particularly on issues of worker protection and advice on women's or child labor . As a member of the commission to advise on the trade regulations , he succeeded in lifting the previous obligation to keep work books , some of which were used by entrepreneurs as a control instrument. In addition, he demanded that trade courts should also decide on termination issues. He also called for the truck system to end and advocated a ban on child labor under the age of 14.

However, like Liebknecht, Bebel also sharply attacked the political system of the North German Confederation. The founding of the federation was by no means aimed at German unity; rather, it was merely based on Prussian power interests.

The result is a "Greater Prussia, surrounded by a number of vassal states whose governments are nothing more than governors-general of the Prussian crown." In the course of his first parliamentary speech, Bebel emphasized that he was on the German, but not the Prussian standpoint. He disapproved of a federation that "made Germany into a large barracks" "in order to destroy the last remnants of freedom and popular law." Bebel and Liebknecht's large-German federalist stance stood in opposition to the ADAV's small-German-Prussian standpoint. This difference exacerbated the conflict between the two branches of the socialist labor movement.

Bebel knew how to assert himself among the sometimes much more experienced parliamentarians. His brilliant oratory skills also attracted the attention of political opponents. Hermann Wagener , a close confidante of Otto von Bismarck, characterized him:

"Bebel is not only an excellent nature speaker, he also has a statesmanlike streak, which gives his speeches a certain higher stamp, so that few can compare and measure with him in parliamentary operations."

Engels compared the parliamentarian Bebel with the master of ancient rhetoric Demosthenes , and even Bismarck described him as the “only speaker” in parliament.

Attitude to the Franco-German War

The beginning of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 led to a crisis within the party. The trigger was Liebknecht and Bebel's attitude to the question of whether or not one should approve war credits in view of the general enthusiasm for war. Bebel made a statement on this in the Reichstag of the North German Confederation . In his view, this was a dynastic war in the interests of the Bonaparte dynasty . He and Liebknecht could not approve funds because this would be a vote of confidence in the Prussian government, which itself had prepared this situation with the war of 1866. But he did not want to refuse the funds either, because this could be interpreted as approval of “the outrageous and criminal policy of Bonaparte. As principled opponents of every dynastic war [...] we can neither directly nor indirectly declare ourselves in favor of the current war and therefore abstain ”.

The party committee in Braunschweig, as the highest party body of the SDAP, viewed the war as a defensive war, criticized the attitude of its two parliamentary representatives and attacked them sharply in the party organ Der Volksstaat .

The French defeat in the Battle of Sedan and the end of the French Empire brought an end to the internal party dispute. The party demanded an immediate end to the war. In the North German Reichstag on November 26, 1870, Bebel protested against the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine by the German Reich in the name of the peoples' right to self-determination and warned of the resulting growing enmity between Germans and French. In a famous speech he called for "peace with the French nation, renouncing any annexation". The Lassalleans and the Eisenachers were now in harmony with this. From now on, MPs from both parties voted against further war loans. Bebel and with him the entire party were then considered "traitors to the fatherland".

Both in the analysis of the war as dynastic in the first half of the war and in characterizing the conflict in the second phase as a German war of conquest, Bebel followed Marx and Engels.

During the war, the southern German states joined the North German Confederation, which then renamed itself the " German Empire ". In the first Reichstag of the empire , Bebel received another mandate and immediately criticized the empire vehemently. He took the view (alluding to Bismarck's quote): “The empire, laboriously welded together with 'blood and iron', is no ground for civil liberty, let alone for social equality! States are preserved by the means by which they were founded. The saber stood by the empire's side as an obstetrician, the saber will accompany it to the grave! "

His positive comments on the Paris Commune in particular met with widespread lack of understanding and rejection outside of the socialist labor movement. On May 25, 1871, he openly expressed solidarity with the broken commune in the Reichstag:

"If Paris is suppressed at the moment, then I remind you that the struggle is only a small outpost battle, that the main thing in Europe is still ahead of us, and that before a few decades pass, the battle cry of the Parisian proletariat: war on the palaces, Peace to the huts, death of need and idleness will be the battle cry of the entire proletariat ! "

This speech confirmed Bismarck and the governments of the German member states in the assumption that the socialists are revolutionaries who endanger the state. The SDAP was then placed under police surveillance.

Leipzig high treason trial

In 1870 Bebel, Liebknecht and the editor of the People's State Adolf Hepner were investigated for high treason . After 102 days in custody, the three defendants were released for lack of evidence as the authorities had found nothing incriminating during searches. In 1872 all three were tried after all. The Leipzig high treason trial was a show trial on the basis of unreliable evidence. The defendants were able to defend themselves effectively. Bebel contradicted the accusation that the SDAP wanted to achieve its goals by force.

"Our party is not a party of coups , not a party that has written riots and coups on its flags."

In the further course he appealed to Lassalle and argued that the workers' party only meant the revolution as a reshaping of public conditions in a peaceful sense. The party had never discussed the way in which it was done. “We left that to the future; we want to wait and see how things go. "Bebel and Liebknecht were to two years imprisonment convicted, acquitted Hepner. In Bebel's case, he was later imprisoned for nine months on charges of lese majesty . The Reichstag mandate was revoked. The condemnation did not achieve its purpose. On the contrary, the defendants Bebel and Liebknecht became political martyrs, and the movement continued to gain popularity.

While in detention, Bebel recovered physically from the exertions of the past few years. Above all, however, he trained himself and spoke of his “detention university”. He not only read socialist authors, but also works by leading representatives of contemporary science as well as classics such as Plato's State . Liebknecht, who was imprisoned with Bebel, introduced him to history and natural history and taught him English and French. Bebel also implemented what he had learned. He made translations from French on the social doctrine of Christianity, wrote a commentary on it and wrote a paper on the Peasants' War of 1525 . He also began his first studies, which were later used in his book The Woman and Socialism .

Nevertheless, Bebel suffered from being unable to participate politically. This was all the harder for him as the central dividing points between ADAV and SDAP were no longer applicable and efforts to reach agreement became apparent.

Way to the united workers party

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels also tried to influence the unification process in order to suppress Ferdinand Lassalle's ideas in the new party. Wilhelm Liebknecht, who had meanwhile been released from prison, was ready to make ideological concessions in the interests of unity. August Bebel was briefed on the various positions in prison by the Marxist Wilhelm Bracke . He brought Bebel a draft program negotiated between representatives of the ADAV and the SDAP, which was far removed from Marxist positions. However, Bracke did not put Bebel's Marxist counter-draft up for discussion in the unification negotiations because he opposed him on a number of points. After his release from prison, Bebel wanted to publicly criticize the negotiated program. However, Liebknecht managed to dissuade him on the grounds that such a dispute could endanger the union again.

From London, Marx and Engels raised strong objections with their marginal glosses on the program of the German Workers' Party . Since these were only made known to a small group - even Bebel did not know them at the time - they hardly played a role in the real development. Although Bebel and Liebknecht valued Marx and Engels as providers of ideas and advisors, they retained a great deal of independence in tactical questions. On May 27, 1875, the Gotha program was adopted at a unification party conference of the SDAP and the ADAV. August Bebel hoped to overcome the "Lassalle'sche poison" in this program in the long run by educating the party members.

Confession to Marxism

Not least as a result of the founder crisis , the number of social democratic voters and party members rose. In the Reichstag elections of 1877 , twelve members of the Social Democrats entered the Reichstag. As a result, the number of state repression measures increased. In 1877, Bebel was sentenced to nine months in prison. The reason was that in a brochure he compared the amount of the military budget to that of elementary school education and argued that in Prussia there would be 85 pupils for one teacher, but six soldiers for one non-commissioned officer in the army.

In parliamentary terms, he and Fritzsche proposed a draft for equal rights for women. He also called for a regulation of prison work, the ban on Sunday and night work and better occupational safety for women and apprentices.

During this time he clearly acknowledged the theory of scientific socialism that Engels later worked out . From then on, this represented the basis of the party’s work:

“As soon as the question of principle takes a back seat in our practical work […] is perhaps downright denied, the party leaves the solid ground on which it stands and becomes a flag that turns like the wind blows. The basic standard must be applied to all of our demands in practice, it must form the touchstone of whether we are on the right track or not. "

Even if Bebel agreed with Engels in particular on fundamental issues, his positions were determined less by Marxian theory and more by experience of practical political work.

Factory owner and private life

In 1863 he met the plasterer Julie Otto in Leipzig , and the wedding took place three years later. The daughter Bertha Friederike emerged from the marriage three years later. Julie Bebel actively supported her husband even during the five years of his repeated imprisonment . Evidence of this is the extensive correspondence between the two of them. Professionally, Bebel had concentrated on the production of door and window handles from buffalo horn. The start-up boom enabled him to expand his business. The workforce comprised a foreman, six assistants and two apprentices. About his motivation to work as an entrepreneur, Bebel expressed himself in a letter to Engels, who for similar reasons had been a successful wholesale merchant for many years, “because if I manage to create an independent position in a business relationship, I can change stand up for the party more freely. "

The founders' crash threatened Bebel's business since 1874. Ferdinand Issleib's entry as a partner, who took over commercial matters, saved him from the economic end. In 1876 the joint company grew by moving to a factory with a steam operation. The product range was expanded to include items made of bronze. Bebel was mainly responsible for sales. He combined business trips throughout the empire with his party work.

In 1884 Issleib terminated the partnership and paid Bebel out. He then described himself as a traveler and writer. His resources were limited at the time. Five years later he gave up traveling completely. The high editions of his writings and his income from journalistic work for various party papers made this possible. In addition, there was a large, unexpected inheritance.

His way of life was quite bourgeois. During his time in Plauen near Dresden, the family lived on the first floor of a villa. Even when Bebel lived in Berlin from 1890, he lived comfortably. So his apartment had electric lighting early on. After 1890 he lived in Berlin-Schöneberg for many years . He consciously moved to the west of Berlin, where it's better to live than anywhere in Leipzig, as he wrote to Natalie Liebknecht.

Under the socialist law

Socialist law

The two assassinations of Kaiser Wilhelm I in 1878, the first on May 11, 1878 , the second on June 2, 1878 , were successfully blamed on the Social Democrats by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. The turnover of the Bebels company then fell, and the Social Democrats lost votes and seats in the Reichstag elections on July 30, 1878 . On October 19, 1878, the new Reichstag passed the Socialist Law, a far-reaching anti-social-democratic exception law. The party and subsidiary organizations such as trade unions and magazines were banned, and leading party members were expelled from Berlin. Protected by his mandate, Bebel did much of the work to ensure the party's survival. Inevitably, he took over the position of the party's treasurer and raised funds for the benefit of members who were in need by the law. He also worked as a speaker and organizer. He was supported by his wife.

A central problem was that the social democratic newspapers were either banned or could only express themselves cautiously. It was Bebel who advocated the creation of a central organ that was to be printed abroad and smuggled into Germany in order to maintain internal party communication. From 1879 the newspaper Der Sozialdemokrat appeared in Zurich (later in London) , first directed by Georg von Vollmar and a short time later by Eduard Bernstein . The editorial committee included Bebel, Liebknecht and Fritzsche. The " Red Field Postmaster " Julius Motteler brought the paper into the Reich. During this time, Bebel became the party's central and leading figure. The police were of the same opinion: The development should "mainly depend on whether Bebel will understand how to expand the dominant influence which he has regained for some time as the most intellectually significant and energetic leader on the party." appeared in election meetings, he was cheered by the audience. In 1882, when newspapers carried a false report of Bebel's death, Marx wrote:

“The greatest misfortune for our party! He was a single phenomenon within the German (one can say the European) working class. "

August Bebel made a significant contribution to motivating supporters, who were partially demoralized by the ban. The Socialist Law led to radicalization in some parts of the party, including the demand to counter violence with violence. Bebel was sharply criticized by the left wing of the party for indirectly acknowledging “non-nationalist patriotism” in an article and for having spoken out in favor of the Social Democrats' participation in a defensive war in an attack from outside. Although he had the term “legal” deleted from the party program at the illegal party's first congress in 1880 at Wyden Castle (Switzerland), he also ensured that prominent representatives of social revolutionary , tending to anarchist views, such as Johann Most and Wilhelm Hasselmann, were excluded . At Bebel's request, the party congress condemned anarchism as anti-socialist.

At his instigation, the legal parliamentary group of the SAP was also given party leadership and the newspaper Der Sozialdemokrat declared the central organ . Bebel tried to keep control of the paper's political line in the hands of the leadership within the empire. Nevertheless, there were always conflicts in which Bebel took different positions. In 1882 Bebel criticized the newspaper for making too radical statements, while a year later he defended it against moderate members of the Reichstag parliamentary group. Bebel resisted the parliamentary group's attempt in 1885 to effectively control the editorial staff.

He received support from Marx and Engels on a visit to London in 1880. In particular, his relationship with Engels became very close over time, as the lively correspondence between the two shows. The two combined criticism of the moderates in the leadership of the party and in the parliamentary group in the Reichstag. This included Liebknecht, who in 1879 had described the SAP as a reform party in the strictest sense of the word and emphasized the party's submission to the law. In contrast, Bebel developed a close relationship with Paul Singer .

The police surveillance of Bebel brought no results. In 1881 Leipzig was also under siege under Section 18 of the Socialist Act. By means of this paragraph in connection with the ordinance of the Royal Ministry of Dresden of June 28, 1881, various socialists (including Bebel, Liebknecht and Bruno Geiser ) were expelled from the city and district of Leipzig. Then Bebel moved with Wilhelm Liebknecht to a suburban villa in Borsdorf near the city, before he went to Plauen with the entire family in 1884.

In 1881 Bebel became a member of the 2nd Chamber of the Saxon State Parliament . In the Reichstag election on October 27, 1881 , he was no longer elected to the Reichstag because he refused to enter into an electoral agreement with the party of the anti-Semitic court preacher Adolf Stoecker . In this election, Bebel ran in several Württemberg constituencies with a counting candidate . How far the labor movement was from its zenith at that time can be seen in some of the results of such candidacies. In his counting candidacy in the city of Nürtingen , in which the SPD was to become the strongest party 17 years later , Bebel only received one vote in the Württemberg parliamentary electoral district 5 ( Esslingen , Nürtingen , Kirchheim , Urach ). In 1882 he was imprisoned again for four months. The reason this time was an alleged insult to the Federal Council . In 1883, Bebel was again a member of the Reichstag through a by-election in the Hamburg I constituency. He represented this constituency until 1893 and then again from 1898 until his death in 1913.

Between compromise and fundamental opposition

Bebel's attitude towards parliamentary work changed during the validity of the Socialist Law. Although he held a central position in the Reichstag parliamentary group, he saw himself more as a party politician and less as a parliamentarian. With the majority of party members, he rejected compromises in parliament. He accused many of the other social democratic members of the Reichstag, such as Wilhelm Blos , Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Dietz or Wilhelm Hasenclever , of thinking of themselves as “demigods”, of having forgotten their proletarian origins and of taking the “parliamentary comedy” too seriously. Unlike after 1890, there are a number of anti-parliamentary statements by Bebel from this period: "I am beginning to dread parliamentarianism," he wrote to Liebknecht in 1885. Within the party, too, he turned against those who were willing to compromise. In a letter to Ignaz Auer in 1882 he said:

“The point of difference lies in the whole conception of the movement as a class movement , which has and must have great world-reshaping goals and therefore cannot compromise with the ruling society and, if it did, would simply perish, or in a new form and from freed from previous leadership, regenerated. "

However, not all members of the Reichstag parliamentary group shared this view and there were sometimes violent disputes, for example in 1884 in a debate about subsidizing steamship lines overseas. While the majority of the parliamentary group saw this question only as a factual problem of transport policy, for Bebel it was a question of principle. “A representation of the working class cannot possibly grant subsidies to the bourgeoisie .” With that he shared the opinion of a considerable part of the party members on this question. According to his own statement, however, he kept his mandate out of a sense of duty to the party.

“My personal wish would be that I had nothing to do with parliamentarism; I do understand, however, that once I get hitched in front of the party cart, I have to keep up there too, as long as I can honorably do so. "

Seated, from left: Georg Schumacher , Friedrich Harm , August Bebel, Heinrich Meister , Karl Frohme .

Standing: Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Dietz , August Kühn , Wilhelm Liebknecht , Karl Grillenberger , Paul Singer .

In 1882 he again prevailed against representatives of a compromise policy at the internal party conference in Zurich. At the illegal party congress in Copenhagen in 1883, at Bebel's insistence, the Bismarck social legislation was declared as a tactical maneuver intended to alienate the workers from the party.

Returning from Copenhagen, Bebel and numerous other delegates were arrested. The regional court in Freiberg sentenced her in 1886 to nine months imprisonment for “unlawful association” ( § 129 StGB ). Bebel also used this imprisonment time for intensive study and writing.

In 1887, the last party conference took place in St. Gallen in the illegality. Bebel's claim to political leadership was undisputed there. He, Liebknecht and Ignaz Auer were elected to a commission to work out a new party program. Bebel also prevailed with his view of parliamentarism. On the one hand, the power of social democracy is based on parliamentary activity and participation in elections, on the other hand, the party should not overestimate parliamentarism. Socialism cannot be achieved by parliamentary means: "Anyone who believes that the ultimate goals of socialism can be achieved on today's parliamentary-constitutional path either do not know the same or are a fraud." In 1887 he came up with a succinct formula Rejection of the social democratic group to the long-term approval of the military budget: "No man and no penny for this system."

With a view to working with other parties, Engels had advocated run-off agreements. Bebel and the party leadership supported this view only within very narrow limits. This included support for Rudolf Virchow in a Berlin constituency against the anti-Semite Stöcker in 1884 . For Bebel, too, the characterization of the other parties as a “reactionary mass”, which goes back to Lassalle, still played an important role.

In the Reichstag, the limits of Bebel's anti-parliamentary ideas were particularly evident in social policy. In the case of the Bismarck social insurance, he ultimately only considered an expansion of poor welfare to be correct, but rejected the legislative package as a whole as half-baked. The social democratic members of the Reichstag therefore voted against the proposals. However, Bebel's position on social legislation was not entirely clear. Under his leadership, the group tabled numerous amendments. Overall, the Social Democratic MPs also worked constructively in the interests of the workers on many issues - such as the limitation of working hours, the further restriction of women's labor and child labor. They tried to improve government proposals for the benefit of their constituents through their own proposals. In doing so, they unspokenly recognized that social improvements were possible within the existing system.

In 1889, Bismarck's attempt to extend the Socialist Law indefinitely failed. The Reichstag election of 1890 produced strong gains for the opposition. The Social Democrats received around 20% of the votes cast and moved into the new Reichstag with 35 members.

Way to the mass party and wing fighting

Party leader and great speaker

Bebel was heavily involved both in the founding congress of the Socialist International in 1889 and in the development of the Erfurt program in 1891. In the end, the clear Marxist draft came from Karl Kautsky . In 1892, Bebel's leading role in what was now the SPD was made clear by his election as one of the chairmen. He held this office until his death. In addition to him, Paul Singer and from 1911 Hugo Haase held the position of chairman. Both were, however, in the shadow of Bebel.

Bebel's influence on the development of the social democratic labor movement was greater than that of any other politician of his generation . He was primarily responsible for the organization of the party and largely shaped its course and its image in public. His honesty and straightforwardness made him the idol of social democratic supporters. Thanks to his talent for rhetoric, his speeches became an experience for his audience. He appeared to them as the mouthpiece of their wishes and goals. Wherever Bebel appeared in public, he regularly attracted thousands of listeners. Before the end of the Socialist Act in 1890, he spoke to around 40,000 to 50,000 people in Hamburg, of whom only around 10,000 could be seated in the assembly halls. He wrote to his wife: When he stepped into the stands "there was a storm of applause that shook the walls, and the same was the case when I left the stage after 1.5 hours of speech [...]." After the chairman cheered Bebel had brought out, "the enthusiasm no longer knew any limits."

Bebel was of the opinion that the end of civil society was imminent. He never left any doubt about the ultimate goal of his policy. It was about the overthrow of the existing state and social order by the working class and the establishment of socialism. In 1891 he prophesied that most of those present would live to see it. Bebel expected the revolution as a lawfully occurring “great bluff” that social democracy did not have to strive to bring about. For him, the international socialist labor movement was a “mighty stream that knows no more obstacles.” Therefore, he reckoned with “victories”.

At the same time, he was aware that many followers not only banked on the future, but asked for changes in their present.

"We only have the enormous following and trust in the working masses because they see that we are practically working for them and not only point them to the future of the socialist state, of which one does not know when it will come."

The party's task is therefore to do everything possible to “raise and improve the situation of the workers [...]” as far as this is possible in bourgeois society.

Inner conflicts since the Erfurt program

Even if the party had been clearly Marxist-oriented since the Erfurt program, there were soon new internal debates about the right path. As a leading figure in the party leadership, Bebel played a central role.

From left: Dr. Simon (Bebel's son-in-law), Frieda Simon-Bebel, Clara Zetkin , Friedrich Engels, Julie Bebel, August Bebel, Ernst Schattner, Regine Bernstein and (only half visible) Eduard Bernstein

The first challenge came from the so-called boys . The opposition spokesmen were Bruno Wille and Paul Ernst . They criticized the party leadership as authoritarian, feared the development of the SPD into a reform party, refused to participate in parliamentary work and, referring to Lassalle 's iron wage law, took the view that wage increases in the capitalist system were pointless. The young were not anarchists but revolutionary socialists. Bebel feared that a radical course would challenge new anti-social democratic laws. He also relied on being able to achieve political power through the steady growth of supporters and voters without violence. It was not difficult for him and the other members of the party leadership to isolate the small opposition group and to drive the boys out of the party.

On the other side of the inner-party political spectrum, Georg von Vollmar , a member of the Reichstag and since 1893 chairman of the party's parliamentary group in Bavaria , pleaded for a reformist course. For him, the struggle for practical social reforms in parliaments was more important than theoretical debates. He also professed to support a defensive war by the workers. Bebel saw this as the task of the central party principles:

"The denial of the real revolutionary goals of the party leads only with necessity to bogus [...] So far we have fought for everything we can achieve from today's state, but what we always achieve - this has always been emphasized - is only a small concession and changes absolutely nothing in the true state of things. "

Vollmar had to bow to Bebel at the party congress of 1891. However, this did not mean the end of reformism. In addition, there were pronounced federal ideas at Vollmar . He advocated a relatively independent state policy and was not prepared within the party to take on all the decisions of the party leadership. In 1894 the Bavarian parliamentary group of the SPD approved the government's draft budget because it contained improvements for the workers. Bebel sharply criticized this. At the Frankfurt party congress in 1894, Bebel and the party executive introduced a resolution that was supposed to oblige members of the state parliament to vote against state budgets. With this proposal, Bebel clearly failed because of the party congress majority. As a result, a public, sometimes polemical, argument developed between Bebel and Vollmar. Bebel accused the Bavarian MPs of being petty bourgeois , opportunists and philistine bourgeoisie , Vollmar described Bebel's behavior as righteousness and self-importance. Vollmar did not succeed in pushing through his ideas in the party, partly because of Bebel's resistance. On the other hand, in this conflict, for tactical reasons, Bebel was not prepared to push for Vollmar to be expelled from the party.

Agricultural program and revisionism dispute

The problem of finding a balance between adhering to Marxist principles and practical politics continued to determine Bebel's political action despite his rejection of southern German reformism .

Bebel's hope of achieving a parliamentary majority after the end of the Socialist Law was not fulfilled. In particular, attempts to reach the rural population failed. Therefore, an agricultural program was designed to protect farms. The party congress of 1895 rejected this at Kautsky's instigation because it was too far removed from Marxist principles. With all due respect for theory, Bebel decidedly went too far. He told Victor Adler :

"The Wroclaw resolutions extend our waiting period by at least 10 years, but we have saved the principle."

In political practice, Bebel was quite ready to deviate from the party program. Although the party congress in 1893 had decided not to take part in the elections for the Prussian House of Representatives , Bebel spoke out in favor of it in 1897. Even the support of bourgeois opposition politicians he no longer ruled out. He argued that in so many places it could be possible to get rid of the worst enemies of the workers. He met with strong resistance from the party leadership, but also at the grassroots level. It was not until 1900 that it was able to prevail. He also advocated joining up with bourgeois parties beyond Prussia, insofar as this was necessary to strengthen the party, expand political rights, improve the social situation or to defend against “anti-workers and anti-people” efforts. Since electoral agreements were tied to a long list of conditions at Bebel's request at the 1902 party congress, this aspect did not play a significant role in practice. It was not until 1912 that an agreement was reached with the Progressive People's Party , which Bebel received sharp criticism from the left of the party.

As early as the 1890s, initiated primarily by Eduard Bernstein , the theoretical questioning of Marxist orthodoxy as embodied by Kautsky began in the revisionism dispute. Like Vollmar, Bernstein came to the conclusion that the SPD had to develop into a left-wing democratic reform party. Despite his friendship with Bernstein, Bebel firmly rejected his ideas because, in his opinion, they threatened the foundations of the party. He remarked in a letter to Victor Adler in 1898:

"By questioning the principles, the tactics are also called into question, our position as social democracy is called into question."

In the years that followed, Bebel vehemently fought against what was disparagingly revisionism. Like Kautsky, he even wanted to expel Bernstein from the party at first. For the first time, the party congress of 1899 discussed Bernstein's theses heavily. Ultimately, Bebel succeeded in pushing through a resolution that was Marxist in tone. However, the composition of the delegates also showed how wide the range of views was. On the left was Rosa Luxemburg ; a rather broad “revisionist” group turned against it. B. Eduard David belonged. Between these wings, the center around Bebel and the party leadership had a difficult position. The debate about bringing revisionism to an end did not succeed, especially since Bernstein returned from exile in 1901.

The inner-party conflict was exacerbated when, after the election victory in 1903, Vollmar proposed that the strongest party claim a place in the Presidium of the Reichstag. But since this was connected with going to court , with the introduction to the emperor, Bebel strictly refused. At the 1903 party conference in Dresden, Bebel stated that the party had never been more divided. Since the dispute with Vollmar he had "had a lot to swallow", but he had always tried to balance the differences, "now we have to finally get clear, clean the table." Revisionism would never be successful in the party, but "It splinters our forces, it hinders our development, it forces us to disagree." Vollmar, on the other hand, violently turned against Bebel, who he accused of being authoritarian:

“He divides the party comrades into such first and second class, yes, into the true and false Social Democrats. I ask you: in what tone did Bebel speak to the whole party? 'I will not tolerate', 'I will wash my head', [...] 'I will keep my accounts'. I, I, I - is that the language of an equal among equals, or rather the language of a dictator. "

Bebel replied that nine tenths of party members rejected Vollmar's theses, even if the common press praised them. At this party congress he exclaimed:

“I want to remain the mortal enemy of this bourgeois society and this state order in order to undermine their conditions of existence and, if I can, to eliminate them. As long as I can breathe and write and speak, it shouldn't be any different. "

Bebel succeeded in asserting his positions on the question of the Reichstag presidium as well as on the formal rejection of revisionism and a ban on budget approvals by the parliamentary groups with a large majority. However, this could not prevent the practice, especially among trade union leaders, from strengthening a tendency towards practical reforms.

Mass strike debate and budget approval

After the Russian Revolution in 1905 and the formation of workers' councils there , the importance of the left wing increased in German social democracy. Rosa Luxemburg was responsible for informal management. She was supported by Karl Liebknecht and Clara Zetkin, among others . Especially the advocacy of the left for the political mass strike led to internal party conflicts. Luxembourg's main opponent on this issue was the party's predominantly reformist (“reformist”) trade union wing.

At the party congress in Jena in 1905, opinions clashed. Bebel tried to mediate between the camps. In certain cases he thought the mass strike was legitimate and necessary. This was especially true for the defense of the democratic right to vote at Reich level and for the right of association .

“We do not allow rights that we have to be taken away from us, otherwise we would be pathetic, wretched fellows. [...] Then we all have to go into the fire, if we stay on the track. "

In contrast to Luxemburg, which saw the mass strike as a means of offensive, for Bebel it was only a defensive weapon. Bebel did not see this as a panacea for solving all political questions.

"We do not believe that we can turn bourgeois society off its hinges with the general strike , but we are fighting for very real rights, which are essential for the working class if it wants to live and breathe."

At Bebel's request, the party congress decided to recognize the general strike only as a means of defense to ward off “political crimes”.

Large sections of the trade unions maintained their line of reform despite Bebel's efforts to win them over to the party's position. Resolutions of the trade union congress against the mass strike showed how great the differences were between party and trade union. A year later at the Mannheim party congress, Bebel repeated his position. He emphasized, however, that the party had to rely on the unions to trigger strikes and tried to improve the relationship with the unions, which was burdened by the mass strike debate.

"Above all, we want to bring about peace and harmony between the party and the trade unions."

The party congress approved a motion by the executive committee, which stated that political actions would have no prospect of success without active support from the unions. It was not the party but the General Commission of the Trade Unions that had the last word on the mass strike question. This meant a clear rejection of an offensive political mass strike. At the end of the party congress, the Mannheim Agreement recognized the actual equality of the party and the trade unions.

The mass strike was also the subject of the 1907 International Socialist Congress in Stuttgart. Bebel submitted a resolution there on the question of the behavior of the SPD in the event of a possible outbreak of war. In this case, the socialist parties should do what they consider most effective to prevent war. On the other hand, the French side called for specific actions such as the general strike. For Bebel this was unacceptable: the German Social Democrats would not allow themselves to be forced to use methods of struggle that would be fatal for party life. The French socialist Gustave Hervé then accused him of claiming that German social democracy had become bourgeois and that Bebel had become a revisionist.

In connection with the Prussian suffrage struggle in 1910, Rosa Luxemburg expanded her concept of a mass strike and found approval from some left-wing parties. The board of directors, at the head of which was still Bebel, rejected this approach.

The reformist forces also continued to put pressure on Bebel. Despite clear party congress resolutions, the Bavarian parliamentary group, for example, reserved the right to approve or reject the state budget, depending on the situation. The parliamentary group voted in 1908 and against in 1910. Something similar had already happened in Württemberg and Baden . At the 1908 party congress, Bebel once again emphasized that acceptance of the budget would mean recognition and even support for the system. Resistance to this came mainly from the southern Germans Ludwig Frank and Eduard David. 258 delegates voted for a resolution of the board of directors on this matter, but 119 against. This shows how divided the party was on the budget issue. It was obvious that the South German Social Democrats would ignore the decision in case of doubt. When the SPD parliamentary group in the Baden state parliament approved the budget in 1910, Ludwig Frank was aware that this would meet with fierce resistance from Bebel. Bebel wrote about this to Kautsky:

"Now the question must be asked, either recognition and submission to the decisions of the party congress, or withdrawal from the party."

In 1911, the Magdeburg party congress condemned both the mass strike demands of Luxembourg and the “Baden reformism” as a violation of party discipline. However, the exclusion of the Baden residents in particular was out of the question, as this would have divided the party. The party congress also decided that budget approval would result in party exclusion in the future. By 1910 at the latest, the three party wings were clearly separated from one another: the left wing around Luxembourg, the reformist center with a focus on southern Germany, and the Marxist center around Bebel and Kautsky.

Politics in the Reichstag

Bebel devoted a large part of his time to his mandate in the Reichstag. Philipp Scheidemann reported emphatically on the great importance that parliament played for Bebel.

"For Bebel, the Reichstag was actually the House, which he only entered in holiday clothes because the people wanted to send their best here, at least those who enjoyed their trust and should represent their interests."

Bebel took his parliamentary obligations very seriously and was the Social Democratic speaker in the Reichstag who drew the most attention. In addition to being one of the best speakers, he was also one of the hardest-working applicants. Not least his increasingly positive attitude towards parliamentarianism led Rosa Luxemburg to be increasingly critical of Bebel.

"The situation is simply this: August and especially all the others have given up completely for parliamentarism and parliamentarism."

The criticism was not entirely justified because Bebel did not try to approach other parties and make compromises in order to win majorities. He always stayed in his basic position. He therefore viewed the actions of the center leader Ludwig Windthorst with incomprehension , who was ready for alliances with various parties.

Despite their numerical strength, the Social Democrats in the Reichstag were still outsiders. When Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg asked Bebel how he was doing in 1912 , it was a remarkable event for him.

“I've been part of this house since 1868. This was the first time that a member of the government addressed me outside of the negotiations. "

In 1894, Wilhelm II tried again to push through an anti-social democratic special law with the overthrow bill. Engels then called on the SPD to take part in mass protests. Bebel turned it down because he knew that the law would be brought down in parliament with the help of the Center Party. The prison bill of 1898 fared little differently . Bebel said in parliament:

“I mean, there has never been anything so class-hating, something so upsetting and incitatory to the lowest classes, like this bill. All social democratic agitators taken together could not work for social democracy in such an excellent way as the dissemination of the memorandum for this draft did. "

Bebel took part in numerous political disputes. Outside the Reichstag, too, he turned against the Germanization policy in eastern Germany. He rejected anti-Semitism as reactionary. He viewed it as a transition phenomenon of the middle classes and hoped to be able to win anti-Semites over to socialism. The saying “anti-Semitism is stupid fellows socialism” has been falsely attributed to him. Bebel himself names the Austrian politician Ferdinand Kronawetter as the source . He presented his position in this regard at the party congress in 1893 in a keynote speech that appeared in the form of a brochure under the title “ Anti-Semitism and Social Democracy ”.

Military legislation was particularly important to him. Again and again he fought the Prussian army organization and stood up for a militia army . He repeatedly denounced the harassment of officers and NCOs. In 1892, he submitted a collection of material to the Reichstag that documented the abuse of soldiers by superiors.

Last but not least, he criticized the “politics of strength” and the armament associated with it. He fought them as early as 1890

"Circles which, in their hypernational vanity, believe that in the slightest conflict with any state Germany must appear with the dashing of a reserve lieutenant and force the enemy to blind submission at any cost through cannons and saber rattles or fleet demonstrations."

Ultimately, Wilhelminian Germany is only concerned with "belonging to the world's first war powers."

Under the leadership of Bebel, the SPD followed a clear course against the imperialist policy of the German Reich. Bebel in particular repeatedly denounced human rights violations in the colonies in the Reichstag debates . In 1889 he criticized the bulk import of brandy into the colonies. It aims to degenerate and corrupt the local population and ultimately to get them completely under control. He often criticized measures that he considered to be wrong. In 1900, for example, he condemned the sending of German troops to suppress the Boxer uprising in China. He sharply rejected the brutal methods used in German South West Africa the uprising of the Herero and Nama was crushed. He also disapproved of the policy of the Reich Commissioner for German East Africa Carl Peters . The German attitude during the first Moroccan crisis in 1905/06 was also rejected by him .

Bebel saw with great concern that the German-British relationship was deteriorating. Against this background, he warned against an expansion of the German navy. In particular, his criticism of the naval armor led him to "flee into secret diplomacy". For years he had been in contact with British government circles through Heinrich Angst, the British consul general in Switzerland. He warned the British government several times that their armaments efforts would be eased. He demanded that Great Britain should try to induce Germany to give in by increasing rearmament. Until shortly before his death, he delivered political assessments and reports to the British.

While Bebel advocated an alliance with England and strictly rejected a war between Germany and France, his relationship with Russia was different. Like Marx, he saw the greatest threat to peace in the imperialism of the Russian Empire . At the same time, he saw Russia as a pillar of the reaction in Germany:

“There in the east is our real and only dangerous enemy. We have to be on our guard against him and keep our powder dry on land. "

He even expressed patriotic views on the perceived threat from Russia . The Social Democrats would defend Germany, "because it is our fatherland, [...] because we want to make this our fatherland a country that nowhere else in the world exists in such perfection and beauty."

At the SPD party congress in 1907, he said that in the event of a war against Russia he would be "an old boy still ready to pick up the gun and go to war against Russia."

Within his faction, Bebel was a leading figure, but was unable to assert himself in all respects. When he in 1902 z. B. wanted to submit a motion to abolish § 175 and thus against the prosecution of homosexual men, it failed because of the majority of the parliamentary group members. In recent years, Bebel, who for health and family reasons mainly lived in Zurich, was no longer able to take part in parliamentary sessions; but he tried at least to be present in the parliamentary group meetings. In 1911 he gave his last major foreign policy speech and warned against any war policy. His frequent absence meant that the various forces in the faction diverged more and more. Certain currents held special conferences, and in fact sub-groups emerged.

Writing activity

August Bebel never saw himself as a socialist theorist. In fact, however, he was also important for the development of the party as the author of agitation pamphlets, daily political newspaper and magazine articles, but also of powerful larger publications and books.

He wrote in the newspapers Arbeiterhalle , Democratic Weekly , Volksstaat or Vorwärts . He also worked frequently for Die Neue Zeit . Of his directly party-political writings, the frequently reissued brochure Our Goals (1870) was particularly effective.

In addition, he published on historical topics. In Zwickau prison Osterstein Castle was built 1874-75 his work on the Peasants' War of 1525. She was less important than the study of Friedrich Engels on the same subject, at that time did not know the Bebel. At the same time he wrote a little pamphlet about the early socialist Charles Fourier , which later saw several editions. In prison in 1884 he dealt intensively with the history of the Arab Orient and in 1884 published the work The Muslim-Arab Period of Culture . It illuminates the state of knowledge of the history of the Arab empires of the Orient at that time up to the rise of the Ottoman Empire to a great power in the 16th century from the perspective of a Marxist self-taught person . He emphasized the role of Islamic culture in the Middle Ages in Spain and the Orient as a mediator between classical Greco-Roman antiquity and modern times, as well as the tolerance of Islamic culture towards religious minorities, especially Judaism, and contrasted this with intolerant and narrow-minded Christianity , which officially preached anti-Semitism and intolerance towards members of non-Christian religions and atheists in the second half of the 19th century in both the Roman Catholic and Protestant forms. As an atheist, he turned against Protestantism and Catholicism of his time in other writings. Christianity and socialism were irreconcilable opposites for him.

His most influential work was Die Frau und der Sozialismus (1879) with numerous reprints up to the present day. During his lifetime alone, 52 issues appeared. With the 50th edition in 1910, the book acquired the form it still has today, and by 1913 it was translated into 20 languages. In it he calls for the professional and political equality of women. Bebel incorporated numerous aspects from medicine, the natural sciences, law and history. He combined his description of the situation of women over time with criticism of the existing social order. Only a socialist society would bring an end to discrimination against women. Finally, Bebel sketched the socialist future state. After the abolition of private ownership of the means of production , numerous social evils would also be remedied, state organizations would be superfluous, and religion would disappear.

The work was also perceived outside the party, but largely rejected as unscientific. Eugen Richter processed the content in his social democratic images of the future . For decades, women and socialism were among the most effective agitation writings in working class circles.

In addition to this clearly forward-looking font, Bebel also wrote works aimed at improving living and working conditions in the present. In addition to specialist knowledge, this was also based on intensive study of the data and facts. In 1880 a paper appeared on the situation of the Saxon weavers, in 1888 Bebel wrote about Sunday work and in 1890 he wrote a detailed account of the working conditions of the journeyman bakers. The data came from government investigative commissions. Bebel's work helped remedy some of the grievances presented.

Of great importance for the party were the reports on the parliamentary work of the previous legislative period that appeared in connection with the Reichstag elections. Due to lack of time, Bebel's plan to write a history of German social democracy, for which he had already started preliminary studies, could not be implemented.

In 1909, Bebel began writing his autobiography. This was published under the title "From my life." In 1910 the first part appeared, a year later the second. Bebel could no longer complete the third part. The presentation ends in 1883. Apart from the first chapters about his youth, he wrote more about political developments and less about himself. The work is of great importance as a source for the history of early social democracy.

Last years and death

In May 1888 his daughter Bertha Friederike (Frieda) fell ill. From 1889 Frieda Bebel (1869–1948) studied medicine in Zurich, a decision her father had encouraged her. Since the late 1890s, Bebel stayed mostly in Zurich. His daughter lived there with her husband Ferdinand Simon (1864–1912). The marriage of the two was, according to the contemporary witness Heinrich Lux, "extremely happy". In 1894, Bebel's only grandson Werner (1894–1916) was born. In 1897, Bebel had a ten-room villa built at Seestrasse 176 in Küsnacht , the "Villa Julie", with its own jetty to Lake Zurich . He and his wife lived in the attic, the rest of the house was rented out. He later sold the house and ended up living in an apartment in Zurich.

Bebel remained mentally unaffected until the end of his life. But he had long suffered from his weak physical condition. Since 1907 there was also a serious heart condition. He ignored the advice of his doctors to give up all parliamentary and agitational activity.

In his final years he suffered a number of personal blows of fate. His wife Julie died in 1910. His son-in-law, the doctor Ferdinand Simon, became infected during a bacteriological examination and died in 1912. As a result, Frieda had to be admitted to a sanatorium because of severe depression. After her condition improved, she lived with her father. The early death of his son-in-law pained Bebel deeply. In addition, there was the assumption of additional responsibility for daughter Frieda Simon and the still underage grandson Werner Simon.

Within the party, most of his old confidants had already passed away. Although he was highly revered in the party and the International, Bebel no longer had close friends, apart from Victor Adler in Vienna. He was not personally close to the men of the new generation of leaders in the SPD. He didn't get along very well with Hugo Haase , and Friedrich Ebert seemed to him to be on the right. Bebel performed for the last time at Whitsun 1913 in Bern . There, members of the German Reichstag and the regional parliaments met with representatives from France for a large mutual agreement conference initiated by Ludwig Frank.

On August 13, 1913, August Bebel died of heart failure in Passugg , Switzerland, during a stay in a sanatorium. He was buried in the Sihlfeld cemetery in Zurich with great sympathy from the local population after he had been laid out in public in the Volkshaus "under a forest of wreaths", where 50,000 people passed him in silence. Delegations from numerous countries came to the funeral.

Until his death, Bebel remained the universally recognized leader of German social democracy. Even within the Socialist International , Bebel enjoyed a worldwide reputation, which after him, as a German Social Democrat, was probably only achieved by Willy Brandt .

Posthumous reception

Labor movement

In 1913, Eduard Bernstein described him in his obituary as the "embodiment of the party" and as the "interpreter" of its thoughts and feelings. His demeanor might appear dictatorial, but his democratic disposition is beyond doubt.

In 1947, social democratic publishers from Berlin founded the August Bebel Institute , "in order to initiate the reconstruction of a social and democratic society with historical responsibility".

In 1950, Federal President Theodor Heuss suggested that Kurt Schumacher have a Bebel biography created "in order to do justice to this personality as a piece of German history."

On the 90th anniversary of Bebel's death, Horst Heimann wrote in Vorwärts in 2003 :

"Willy Brandt proudly mentioned the verdict of the Züricher Wochen-Chronik on the death of August Bebel 'that the 73-year-old's unexpected death caused a greater sensation in the whole world than that of a crowned head'. And Brandt added: 'August Bebel died like an emperor. And it was he too - for a long time during his lifetime: an emperor of the workers and the common people. '"

Women's movement

Bebel is considered to be one of the most important exponents of the Marxist theory of women's emancipation, his book The Woman and Socialism was of great importance for the contemporary women's movement and was widely received across Europe. This is documented u. a. by Bertrand Russell's wife Alys Russel, Ottilie Baader , Marie Juchacz , Agnes Robmann and Betty Farbstein, as well as by Auguste Fickert , who shared Bebel's conviction that gender equality cannot be achieved in capitalism. The pacifist Lida Gustava Heymann , who was involved in the radical wing of the bourgeois women's movement, had already bought Die Frau von Bebel at the age of eighteen . In her memoirs written down in exile in Zurich, she sums up:

“What German socialists like Marx, Engels, Bebel, Vollmar and others - even if one rejects their rigid Marxism - contributed to the liberation of women through their writings and their parliamentary activities, was always recognized with gratitude by the radical women's movement. It has become a historical fact and a solid foundation of the women's movement. "

Bebel's treatment of the women's question as a so-called secondary contradiction (in contrast to the main contradiction, namely the class struggle) also met with opposition in circles of the women's movement. For example, the feminist writer Johanna Elberskirchen saw the "rule of sex" as a priority.

Even a politically interested and active woman like Marie Baum , who never joined social democracy, did not want to miss a lecture by August Bebel during her time in Berlin: “When I, used to the freedom of movement in Switzerland, I gave a lecture by Bebel in the overcrowded hall looked forward from a happily secured place, suddenly the call from the supervising police officer rang out that 'women and apprentices' had to leave the hall - and I had to submit! "

In particular, the magazine Die Equality , in the understanding of its long-time editor-in-chief Clara Zetkin, above all a socialist organ of class-conscious proletarians, gave Bebel's optics a lot of space on the question of women.

Fifty years after the publication of the longseller Die Frau und der Sozialismus , the women's rights activist Minna Cauer , who is rooted in the radical wing of the bourgeois women's movement, expressed her gratitude in the magazine Die Frauenbewegung Bebel, which she published, and stated that everything that was needed was available in this work to advance the woman's cause, namely hope, dreams for the future and encouragement.

Bebel reception in Switzerland

In Switzerland, too, he was seen as a formative figure of the labor movement and social democracy, which is why an exhibition in his honor in the Sihlfeld cemetery in Zurich on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of his death in the summer of 2013, curated by Willi Wottreng .

The Swiss writer and publicist Hans Peter Gansner wrote the drama Am Saum der Zeit or Bebel's death on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of August Bebel 's death . Gansner's play takes place for three days in August 1913, in Bebel's hotel room in the Kurhaus Bad Passugg, and ends with Bebel's death. The three acts are framed by a prelude and an aftermath in which five young people from Graubünden appear. The focus is on the contemporary reception and discussion of Bebel's commitment to peace, the emancipation of women and workers on the eve of the First World War.

August Bebel Prize

The August Bebel Foundation , founded by Günter Grass in 2010 , aims to promote people who, like Bebel, have made a name for themselves in the German social movement and anchor them in national memory. Every two years, outstanding personalities are to be awarded the August Bebel Prize endowed with 10,000 euros .

- The first winner in March 2011 was the social philosopher and sociologist Professor Oskar Negt . The award goes to his life's work, in which Negt has repeatedly campaigned in the spirit of Bebel, most recently with the book Derpolitischen Mensch , published in 2010 .

- On February 22, 2013, Günter Wallraff was honored for his life's work, especially for his reports with which he highlighted grievances.

- The August Bebel Prize 2015 went to Klaus Staeck . On May 4th, the artist received the award in the Willy Brandt House in Berlin . The event also commemorated the recently deceased Günter Grass, founder of the August Bebel Foundation.

- In 2017 Gesine Schwan received the award.

- In 2019, Malu Dreyer received the August-Bebel-Preis of the August-Bebel-Stiftung, because she made a special contribution to social justice.

Facilities and locations named after Bebel

- August-Bebel-Allee in Bremen , Neue-Vahr-Nord

- August-Bebel-Höhe, name of the " Echo " lookout point in the Zwickau district of Rottmannsdorf from 1951 to 1994

- August Bebel schools (list)

- August-Bebel-Streets (list)

- August Bebel Institute in Berlin

- Bebelplatz in Berlin-Mitte

- Bebelplatz in Kiel

- Bebelplatz in Cologne-Deutz

- Bebelallee in Hamburg-Winterhude

- August-Bebel-Platz in Bautzen

- August-Bebel-Park and the adjacent street in Mannheim-Neckarau

- Bebelhof (Vienna) in Vienna

Writings and speeches

Individual fonts (selection)

- Social democracy and universal suffrage . Berlin, 1895 ( digitized version and full text in the German text archive )

- The woman and socialism. Dietz-Verlag, Berlin 1990 (Zurich 1879). ISBN 3-320-01535-4 . Digitized, 40th edition. Online edition.

- Our goals. A pamphlet against the Democratic Correspondence. Leipzig 1870. (12th edition Leipzig 1911)

- Christianity and Socialism. A religious polemic between Kaplan Hohoff in Hüffe and the author of the book: The parliamentary activity of the German Reichstag and the Landtag and the social democracy. Leipzig 1874,

- Leipzig high treason trial. Detailed report on the negotiations of the jury court in Leipzig in the trial against Liebknecht, Bebel and Hepner for preparation for high treason from 11th to 26th December. March 1872 . Edited by the defendants. Leipzig 1874.

- The German Peasants' War with consideration of the main social movements of the Middle Ages. Braunschweig 1876.

- The development of France from the 16th to the end of the 18th century. A cultural-historical sketch . Leipzig 1878.

- How our weavers live. Private study on the situation of weavers in Saxony . Leipzig, 1879. (digitized version)

- Charles Fourier. His life and his theories. Stuttgart, 1888 (online edition at: gutenberg.org )

- Sunday work. Extract from the results of the survey on the employment of industrial workers on Sundays and public holidays together with critical remarks . Stuttgart 1888.

- On the situation of the workers in the bakeries . Stuttgart 1890.

- The Muslim-Arab cultural period, 1884, 2nd edition. 1889. (Newly edited by Wolfgang Schwanitz, 1999, Edition Ost, Berlin, ISBN 3-929161-27-3 ).

- Why do women demand the right to vote? In: Women's suffrage! Edited on the First Social Democratic Women's Day by Clara Zetkin. March 19, 1911, p. 2. ( digitized version and full text in the German text archive )

- From my life, Vol. 1–3, Stuttgart, 1910, 1911, 1914. (Online version) (Unabridged new edition used here: Verlag JHW Dietz, Bonn 1997, ISBN 3-8012-0245-3 )

- Modern culture is anti-Christian. Alibri Verlag , Aschaffenburg, ISBN 3-932710-59-2 .

Collective editions

-

Horst Bartel u. a. (Ed.): Selected speeches and writings.

- Volume 1: 1863-1878. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1978.

- Volume 2: 1878-1890. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1978.

- Volume 3: 1890-1895. Saur, Munich 1995.