Frédéric Chopin

| Timetable | |

|---|---|

| For the time of Chopin's works, see below: Works . | |

| April 6, 1807 | Birth of Ludowika, Chopin's older sister. |

| February 22 or March 1, 1810 | Birth of Fryderyk Chopin in Żelazowa Wola around 6 p.m. |

| April 23, 1810 | Baptism of Fryderyk in the Church Świętego Rocha i Jana Chrzciciela in Brochów. |

| September / October 1810 | The Chopin family moves to Warsaw. |

| July 9, 1811 | Birth of sister Izabela. |

| November 20, 1812 | Birth of sister Emilia. |

| 1813 | Chopin's first attempts to play the piano. |

| 1814 | Death of the grandfather François Chopin. |

| 1816 | First piano lessons from sister Ludowika. |

| 1817 | First piano lessons with Wojciech Żywny. First printed work - Polonaise in G minor (B. 1, KK IIa / 1, Cho 161). |

| February 24, 1818 | First public appearance at a charity concert in Radziwiłł Palace. Chopin plays the Piano Concerto in G minor by Adalbert Gyrowetz. |

| February 26, 1818 | Chopin gives the mother of the Russian tsar two compositions (the polonaises in G minor and B flat major) during a visit to the Warsaw Lyceum. |

| 1822 | First composition lesson; To prepare for the conservatory, Józef Elsner takes on the lessons. |

| 1823 | Admission to the Warsaw Lyceum. |

| 1825 | Enter Chopin before Tsar Alexander I, who gives him a diamond ring. |

| July 1826 | Chopin leaves the Warsaw Lyceum a year earlier without a school leaving examination. |

| July 28 - September 11, 1826 | Travel to the Bad Reinertz spa (today Duszniki-Zdrój) as a companion to sister Emilia and mother. Benefit concert for orphans. |

| October 1826 - July 1829 | Music studies at the conservatory. |

| April 10, 1827 | Emilia, Chopin's 14-year-old youngest sister, dies. |

| July 31 - August 19, 1829 | Trip to Vienna, Prague, Dresden. |

| August 11, 1829 | 1st concert in Vienna. |

| August 18, 1829 | 2nd concert in Vienna. |

| August 21-24, 1829 | Visit to Prague after leaving Vienna. |

| August 26 - September 2, 1829 | Visit to Dresden after leaving Prague. |

| 1829/1830 | Encounter with the romantic poets Stefan Witwicki, Bohdan Zaleski, Seweryn Goszczyński a. a. |

| March 17, 1830 | First concert at Teatr Wielki in Warsaw. |

| October 11, 1830 | Farewell concert at Teatr Wielki in Warsaw. |

| November 2, 1830 | Departure from Warsaw towards Kalisz. |

| November 5, 1830 | Departure from Kalisz, he leaves Poland. |

| November 6, 1830 | Arrival in Breslau and appearance on November 8th (rondo from the piano concerto in E minor). |

| November 23, 1830 | After 8 days in Dresden and a short stay in Prague, arrival in Vienna. Beginning of the November Uprising in Warsaw. |

| November 23, 1830 - July 20, 1831 | Stay in Vienna. |

| June 11, 1831 | Chopin's appearance in Vienna (concert by D. Mattis). |

| July 20, 1831 | Chopin leaves Vienna and travels to Paris via Salzburg, Munich (appearance on August 28, 1831), Stuttgart and Strasbourg. |

| September 8, 1831 | Surrender of Warsaw during Chopin's stay in Stuttgart. |

| October 5, 1831 | Arrival in Paris. |

| December 7, 1831 | Robert Schumann publishes an article about Chopin in the “Allgemeine Musikzeitung”. |

| February 25, 1832 | First concert in Paris at the Salons Pleyel, 9 rue Cadet. |

| January 1833 | Fryderyk becomes a member of the Polish Literary Society in Paris. Beginning of Chopin's friendship with Bellini and Berlioz. |

| May 16, 1834 | Trip to Aachen for the Lower Rhine Music Festival. Visits to Cologne, Koblenz and Düsseldorf - meeting Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. |

| Summer 1835 | Journey to Karlsbad, here he meets his parents. Travel to Dresden and get to know Maria Wodzińska . |

| August 1, 1835 | Chopin receives a French passport. |

| 1836 | Fryderyk secretly engaged to Maria Wodzińska. Return journey via Leipzig. Meeting with Robert Schumann. |

| Fall 1837 | First meeting with George Sand in Paris at a reception at the Hôtel de France. |

| 1837 | Fryderyk rejects the title of court pianist to the Russian tsar. Breaking off engagement with Maria Wodzińska. |

| July 7, 1837 | Chopin as the companion of Camille Pleyel for two weeks in London. Meeting with the piano maker Broadwood. |

| March 12, 1838 | Concert in Rouen. Chopin plays his Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11. |

| April 1838 | Beginning of love affair with George Sand. |

| October 18, 1838 | George Sands leaves for Mallorca with her children (Chopin follows on October 27th). |

| December 15, 1838 | Relocation to the Valldemossa Charterhouse on Mallorca. |

| February 13, 1839 | Departure from Mallorca. |

| February 24 - May 22, 1839 | Stay in Marseille. |

| June 1–10. October 1839 | Chopin's 1st stay in Nohant. |

| 1839, 1841-1846 | Chopin spends seven summers in Nohant |

| April 26, 1841 | Chopin's public concert in Paris after a six-year break. Concert review by Franz Liszt in the “Gazette Musicale”. |

| May 3, 1844 | Death of the father Mikołaj Chopin. |

| Late May 1846 - November 11th 1846 | Chopin's last stay in Nohant. |

| July 28, 1847 | Last letter from George Sand to Chopin. End of relationship. |

| February 16, 1848 | Last concert in Paris in the concert hall of the Salons Pleyel, 22 rue Rocheouart. |

| February 22, 1848 | Outbreak of the February Revolution in Paris. |

| March 4, 1848 | Last chance meeting of George Sand and Chopin in Paris. |

| April 19, 1848 | Trips with Jane Stirling to England and Scotland. |

| November 23, 1848 | Return to Paris. |

| September 29, 1849 | The terminally ill Chopin moves into the apartment in Paris, Place Vendôme 12. |

| October 17, 1849 | Fryderyk Chopin's death around two in the morning in Paris, Place Vendôme 12. |

| October 30, 1849 | Funeral service in the La Madeleine church in Paris and burial in the Père-Lachaise cemetery. |

| October 17, 1850 | In the Père-Lachaise cemetery, Jean-Baptiste Auguste Clésinger unveils the tomb he designed with Fryderyk Chopin's medallion. |

| March 1, 1879 | Burial of Chopin's heart in the Church of the Holy Cross (Kościół Świętego Krzyża) in Warsaw. |

| 1927 | Establishment of the International Chopin Competition in Warsaw. |

| 1949 | Chopin's year on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of his death. |

| 1960 | Chopin's year on the occasion of his 150th birthday. |

| February 3, 2001 | Chopin's Legacy Protection Act entered into force. |

| 2010 | Chopin's year on the occasion of his 200th birthday. |

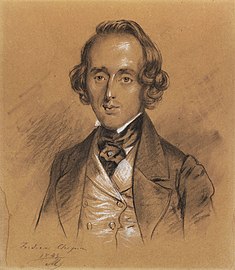

Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin (also Szopen , more rarely Szopę or Choppen ) or Frédéric François Chopin (born February 22 or March 1, 1810 in Żelazowa Wola , in the then Duchy of Warsaw , Poland ; † October 17, 1849 in Paris ) was a Polish composer , Pianist and piano teacher . He had French citizenship from 1835.

Chopin's father was French, his mother Polish. He grew up in a loving, stimulating home atmosphere. His lifelong close ties to family and home were decisive for his personality. Chopin, who is considered a child prodigy , received his musical training in Warsaw , where he also composed his first pieces. He spent the first 20 years of his life in Poland, which he left on November 2, 1830 for professional and political reasons. From October 1831 until his death (1849) Chopin lived mainly in France . His life was marked by illness. In the end he was penniless and dependent on the help of friends. He died at the age of 39, most likely from pericarditis(Pericarditis) as a result of tuberculosis .

Chopin is like Robert Schumann , Franz Liszt , Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy and others. a. a representative of romanticism , which had its heyday in Chopin's adopted home France between 1815 and 1848. As a composer he almost exclusively created works for piano. Chopin's compositional style is influenced by Polish folk music , the classical tradition of Bach , Mozart , Weber , Hummel and Schubert , but especially by the bel canto style of contemporary Italian opera and its representative Vincenzo Bellini. The atmosphere of the Parisian salons, in which Chopin frequented, had a formative influence. Here he developed his skills in free improvisations on the piano, which often became the basis of his compositions. His innovations in all elements of the composition (melody, rhythm, harmony and forms) and the inclusion of the Polish musical tradition with its emphasis on the national character were important for the development of European music.

Even during his lifetime, Chopin was considered one of the leading musicians of his time. His piano playing and his work as a teacher were due to the expansion and utilization of the technical and tonal possibilities of the instrument, the sensitivity of the touch, the innovations in the use of the pedals and in fingeringregarded as exceptional. His ideas about piano playing (facilité "lightness", rejection of the percussive "knocking" stroke, model of singing, the so-called bel canto in agogic and articulation, rejection of mechanical practice without musical commitment, use and training of the fingers according to their natural physiological conditions instead equalizing finger drill) are still considered fundamental in piano pedagogy, or their importance is only being recognized today (e.g. in the prevention of playing damage).

family

Frédéric Chopin's parents were the Lorraine language teacher Nicolas Chopin and Tekla Justyna Chopin, née Krzyżanowska, from Poland. At the time of Chopin's grandparents, Lorraine was ruled by King Stanisław Bogusław Leszczyński , who had received the duchy in 1737 as compensation for the loss of the Polish throne. Many of his Polish followers, including Chopin's grandfather, Fryderyk Choppen (later Chopin), had found a new home in Lorraine. Nicolas Chopin, Chopin's father, took on Polish citizenship and used the Polish form "Mikołaj" [ miˈkɔwaɪ̯ ] as his first name . He worked as an office worker and unskilled worker. After the fall of the Kingdom of PolandIn 1795 he earned his living as a tutor for French with the Polish nobility . Later he was a French teacher at the Liceum Warszawskie , initially as a collaborator and from 1814 until the school closed in 1833 as a high school professor .

Chopin's parents shared a passion for music: Nicolas played the violin and flute, Tekla Justyna played the piano and sang. The marriage took place on April 2, 1804. They had four children.

Birth and baptism

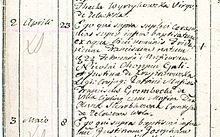

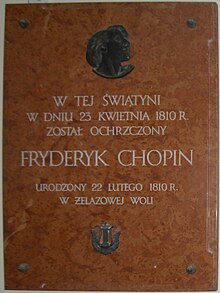

Chopin was born in Żelazowa Wola , a village in the Brochów commune , Warsaw department, in what was then the Duchy of Warsaw . He was baptized on April 23, 1810 (on an Easter Monday) in the church Świętego Rocha i Jana Chrzciciela (Polish " Saint Roch and John the Baptist ") of Brochów under the name Fryderyk Franciszek.

The two documents record February 22, 1810 as the date of birth, but both Chopin and his mother stated March 1, 1810 as their birthday. In the family, Chopin's birthday was always celebrated on March 1st. Since both dates fell on a Thursday, it is now assumed that the father, when he counted back when reporting the birth, counted a week too many and incorrectly entered February 22nd as his son's birthday.

Chopin in Poland (1810-1830)

Childhood, youth and first successes

In the fall of 1810 the family moved to the Saxon Palace in Warsawwhere the Warsaw Lyceum was located and Nicholas was hired as a French teacher. Fryderyk and his three sisters received a thorough upbringing that was characterized by warmth and tolerance. At the request of his father, Chopin received home schooling until he was 13 years old. At the age of five, Fryderyk and his older sister Ludwika came into contact with the piano through their parents who played music. Under the guidance of his mother, the boy made rapid progress in playing the piano and showed great manual and musical talent. In 1816 the parents gave the child to the music teacher Wojciech Żywny for further education. It quickly developed into a child prodigy. Żywny laid the technical foundations guided the six-year-old to his first compositions and prepared him for his public appearances. His first compositions thatPolonaises in B flat major and G minor date from 1817. The press drew attention to the publication of the first work and the child's extraordinary talent. On February 24, 1818 Fryderyk performed in a concert on the theater stage of the Radziwiłł Palace with the Piano Concerto in G minor by Adalbert Gyrowetz . The child, who had become famous, was soon invited to the salons of the nobility in Warsaw and passed around as an attraction for his game and ability to improvise.

In 1822 Żywny finished piano lessons because he felt that he could not give the gifted child any more impulses. Chopin's piano and organ teacher was followed by Wilhelm Würfel , an excellent pianist who familiarized the boys with the modern playing technique, as required by contemporary European piano music of the style . So Chopin learned the works of Johann Nepomuk Hummel , Carl Maria von Weber , Carl Czerny , Ignaz Moscheles , John Field and Ferdinand Riesknow. They had a lasting influence on his virtuoso playing and his own compositional style. From 1822 Chopin took private lessons in music theory and composition from the German Joseph Elsner (Polish: Józef Elsner) , who came from Silesia .

Chopin attended the Royal Prussian Lyceum in Warsaw until 1826 . This was followed by studies at the music college that bears his name today (Uniwersytet Muzyczny Fryderyka Chopina), where he was further taught by Elsner in counterpoint , figured bass and composition . He composed eagerly and presented the results to Elsner, who stated that Chopin, with his unusual talent, avoided the well-trodden paths and common methods. Chopin's other interests varied widely during his music studies. In 1827 the Chopin family moved to the Czapski Palace (Warsaw) .

On February 24, 1823, Chopin appeared as part of a concert series for charitable purposes with a piano concerto by Ferdinand Ries and on March 3, 1823 again with the piano concerto No. 5 in C major by John Field. The reviews of both concerts recognized the young virtuoso's good pianistic and musical abilities.

Under Elsner's guidance he wrote the Rondo in C minor, Op. 1, in 1826 the Rondo à la Mazur in F major, Op. 5, and in 1828 the Rondo in C major, Op. 73 in the version for two pianos and the Krakowiak, Grand Rondeau de Concert F major op.14 for piano and orchestra.

Tytus Woyciechowski (1808–1879) was one of Chopin's closest childhood friends or lovers . He was a fellow student of Chopin at the Warsaw Lyceum and a frequent guest of the Chopin family. Friends of his youth such as Tytus Woyciechowski, Jan Białobłocki, Jan Matuszyński , Dominik Dziewanowski and Julian Fontana remained lifelong. Woyciechowski, whom Chopin referred to several times in his letters as "My dearest life", had like Chopin piano lessons with Vojtěch Živný and then studied law at the University of Warsaw. Chopin dedicated the Variations in B flat major op. 2 on the duet Là ci darem la mano (German: "Give me your hand, my life") from Mozart's opera Don Giovanni.

“As always, I now carry your letters with me. How happy I will be when I walk outside the walls of the city in May, thinking of my approaching departure, pulling out your letter and assuring myself that you truly love me - or at least just look at the hand and the writing of him I know how to love! "

The thesis is widespread that Tytus was also the confidante during Chopin's alleged affair with the singer Konstancja Gładkowska (1810–1889), for which there is, however, no conclusive evidence. When Chopin left the country in autumn 1830, she sang as part of a mixed program at his last public concert on October 11, 1830 in Warsaw.

Even in his youth, Chopin had traveled a lot. Travel was part of his life until the end of his life. His interests were broad. He visited museums, exhibitions, concerts and operas, libraries, universities and admired buildings and their architecture. Chopin's listeners and sponsors included the richest Polish families, such as Radziwiłł , Komar, Potocki , Lubomirski , Plater , Czartoryski and others. a., some of which would later play a major role in Chopin's career as emigrants in Paris and as patrons of his art.

Journey to Berlin (September 1828)

Chopin, eager to get to know the musical life of other cities and well-known artists, had the opportunity in September 1828 to accompany a friend of his father's to a congress in Berlin organized by Alexander von Humboldt . His wish to get in touch with the greats of Berlin's musical life such as Carl Friedrich Zelter , Gasparo Spontini or Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy was not fulfilled, partly because he was too insecure to approach the famous musicians. Numerous visits to concerts and operas ( Carl Maria von Weber's Freischütz ), including the performance of Georg Friedrich Handel's Caecilienode in theThe Berlin Singakademie most impressed, made the two-week trip to Berlin an important event for Chopin's artistic development.

Without belonging to the high nobility himself, Chopin had dealings with aristocratic families since childhood because of his musical talent. In addition to his family socialization, this had an important influence on his personality development . Throughout his life it was important to him to be able to move appropriately in high circles, to be respected and respected.

In July 1829 Chopin finished his studies. Elsner's assessment reads: “Szopen Friderik. Special talent, musical genius ”( Polish “ Szopen Friderik. Szczególna zdolność, geniusz muzyczny ” ). However, an application to the minister responsible for assistance in financing a longer trip abroad to further educate the young artist was unsuccessful. So the family decided to let Frédéric travel to Vienna for a while.

First stay in Vienna (July 31 - August 19, 1829)

The journey began in July 1829 in the company of four friends. Stations were Krakow, Bielsko (German Bielitz), Teschen (Polish Cieszyn ) and Moravia . After arriving in Vienna on July 31, 1829, Chopin visited Polish friends and the publisher Tobias Haslinger. He promised to publish Chopin's Opus 2, Variations on the duet “Là ci darem la mano” from Mozart's opera Don Giovanni for piano and orchestra, written in 1827/28, on the condition that Chopin played it in a concert beforehand and had positive reviews on sale promoted. The concert took place on August 11, 1829 in Vienna's Kärntnertortheaterinstead of. In addition to the world premiere of the Mozart Variations op. 2, Chopin also played a “Free Fantasy”, an improvisation on a theme from the opera La dame blanche (German The White Lady ) by François-Adrien Boieldieu and a Polish folk song. The concert was celebrated as a success by listeners and the press, led to encounters between Chopin and representatives of the Viennese music scene and to a second, even more successful concert on August 18, 1829, in which Chopin, in addition to his Mozart variations, also performed the Krakowiak, Grand Rondeau de Concert F- majorop. 14 played. The reviews of both concerts emphasized Chopin's nuanced, virtuoso playing and praised the delicacy of his touch. It was found, however, that he played too softly, an accusation that Chopin would hear more often in the course of his later career. The compositions were not always understood due to the novelty of their tonal language.

On December 7th, 1831 , the Allgemeine Musikische Zeitung published a review by Robert Schumann under the title Ein Opus II , which was introduced with the exclamation “Hats off, your gentlemen, a genius” about the sheet music edition published by Tobias Haslinger in Vienna . It also said: “Chopin cannot write anything that does not have to be called out after the seventh or eighth bar at the latest: This is Chopin!” Elsewhere: “Chopin's works are like cannons hidden under flowers”. Chopin left Vienna with his companion on August 19, 1829. After a three-day stay in Prague, an extensive tour of the architectural monuments and picture gallery of Dresden and a visit to a performance of Goethe's Faustthe departure from the Saxon capital took place on August 29, 1829. The way back to Warsaw, which was reached on September 10, 1829, went via Breslau and Kalisz .

In Warsaw until departure (September 10, 1829 - November 2, 1830)

After returning from Vienna, Chopin devoted himself intensively to the musical life of Warsaw and to his own work. Important works from this period are the Piano Concerto in F minor, Op. 21, some of the Etudes, Op. 10, the Polonaise in F minor, Op. 71, No. 3, and the Waltzes, Op. 70, No. 1-3. The first performance of the piano concerto in F minor (published in 1836 as the 2nd piano concerto op. 21) took place in a small, private setting in front of invited guests on February 7, 1830. The public performance took place on March 17, 1830 in the National Theater on Krasiński Square in Warsaw. The reviews of the concert in which Chopin also wrote his Grande Fantaisie sur des airs nationaux polonais in A majorop. 13 were very positive. On March 22, 1830 Chopin appeared again in the same theater. This time, in addition to the Piano Concerto in F minor, he played Krakowiak, Grand Rondeau de concert in F major Op. 14 and improvisations on themes from Polish operas ( Jan Stefani : Krakowiacy i górale “The Krakowians and the Mountain People”; Karol Kurpiński : Novi Krakowiacy “The New Cracow”). This concert was also very successful. Even before Chopin's final departure, he wrote a. the Nocturnes Op. 9 and the Piano Concerto in E minor (published in 1833 as the 1st Piano Concerto, Op. 11).

In July 1830, Chopin visited Tytus Woyciechowski for two weeks on his farm in Poturzyn.

“I want to tell you honestly that I think back to all of this with joy - your fields have left a certain longing in me - the birch in front of the windows will not get out of my mind. That Arbaletta [crossbow]! - How romantic! I remember the Arbaletta, because of which you plagued me so much - for all my sins. "

Chopin gave his last concert in Poland on October 11, 1830 at the National Theater in Warsaw (Teatr Narodowy) with the performance of his Piano Concerto in E minor (op. 11) and the Grande Fantaisie sur des Airs Nationaux Polonais pour le Pianoforte avec accompagnement d'Orchestre ( “Great Fantasy on Polish Ways for the Pianoforte with Orchestra Accompaniment” in A major op. 13) under the direction of Carlo Evasio Soliva .

Chopin abroad (1830–1849)

Chopin knew that the really great musicians were not to be found in Warsaw and also no longer in Vienna, but in Paris, the stronghold for artists from all over the world in the 19th century. Back then, the size of a pianist was measured by success in this metropolis. For the first time in 1829 his parents and his teacher sent him to Vienna for three weeks to expand his artistic experience.

Chopin leaves Poland

Chopin left Poland on November 2, 1830 at the age of 20 - also at the urging of his father to face the impending revolt - and traveled with Tytus Woyciechowski via Kalisz, Breslau, Prague and Dresden to Vienna, where he arrived on November 23, 1830. The friends presented him with a silver cup with Polish soil on the last evening and sang him a farewell song on the outskirts, which contained the following refrain:

| • Farewell song (Polish) |

|

Zrodzony w polskiej krainie, |

Refrain:

Although you leave our country,

your heart still remains among us;

the memory of your talent will remain with us ...

We wish you success everywhere. "

Second stay in Vienna

After a four-day stay in Breslau (with a concert on November 8, 1830) and a week in Dresden, Chopin arrived in Vienna with his friend Tytus Woyciechowski on November 23, 1830. Chopin tried in vain to persuade the music publisher Carl Haslinger , who received him kindly, to publish his compositions (sonata, variations). The Viennese taste in music had changed so that during his eight-month stay - in contrast to his first stay in Vienna - he only gave one public concert on June 11, 1831. It took place in the Kärntnertortheater as part of the so-called academies. In this benefit concert, Chopin played his Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11, without a fee. The press praised his piano playing, but not the composition.

During this time Chopin frequented the doctor Johann Malfatti .

Consequences of the November Uprising in Poland

At the beginning of December 1830, Chopin received news in Vienna that on the evening of November 29, 1830 the November uprising against Russian rule had broken out in Warsaw. Woyciechowski left Vienna to take part in the uprising, leaving behind a lonely, homesick Chopin. After a stay of over seven months, which Chopin found disappointing because he was recognized as a pianist, but not as a composer, and because he was marked by concern about Poland's uncertain fate, Chopin left Vienna on July 20, 1831.

The complicated exit formalities - Chopin was a Pole and thus a subject of the Russian Tsar - meant that Chopin, despite his intended destination Paris, applied for a passport to England on the advice of a friend, because he was neither from the Austrian could still hope for support from the Russian authorities. His request was rejected by the Russian embassy in Vienna. But he managed to get a visa to France. His passport was marked “passant par Paris à Londres”. Later in Paris, Chopin often jokingly said that he only stayed here “en passant” - in transit. However, Chopin intended to stay in Paris for at least three years. He drove via Salzburg to Munich, where on 28. August 1831 played the Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11 and the Grande Fantaisie sur des airs polonais in A major, Op. 13 in the Philharmonie. In Stuttgart, which he reached in early September 1831, he learned of the suppression of the Polish uprising and the surrender of Warsaw on September 8, 1831. He continued the journey via Strasbourg to Paris.

Chopin in Paris (1831–1849)

Chopin arrived in Paris in the early evening of October 5, 1831, a complete stranger. He only had two letters of recommendation with him: one from his teacher Józef Elsner for the composer and composition teacher Jean-François Lesueur , the other from the medical doctor Johann Malfatti for the composer Ferdinando Paër , who was responsible for possible contacts with Gioachino Rossini , Luigi Cherubini and Friedrich Kalkbrenner was important.

The Italian composer and court conductor Ferdinando Paër campaigned for Chopin with the authorities to obtain a residence permit. Chopin was fascinated by Paris. Here he met Friedrich Kalkbrenner , whom he valued as a pianist and who made the offer to teach him for three years. With that, Chopin would have undertaken not to appear for this period. Kalkbrenner recognized Chopin's extraordinary talent and, if possible, wanted to avoid competition in the music business. Chopin turned down the proposal, worried about losing his personal way of playing the piano.

When Chopin's arrival in Paris on October 5, 1831, there was a time of economic crisis that repeatedly led to demonstrations. Unrest, hardship and bitterness characterized the mood of the working class. Chopin was in bad physical and mental health. In a letter to Tytus Woyciechowski dated December 25, 1831, he described his situation:

| • Chopin's letter to Tytus Woyciechowski (Polish) |

|

"... my health is miserable. Outwardly I am happy, especially among ours (by ours I mean the Poles), but inside something plagues me - some premonitions, restlessness, dreams or insomnia - longing - indifference - the will to live and then again the desire for death - some sweet peace , some torpor, absent-mindedness, and sometimes an exact memory torments me. I feel sour, bitter, salty, an ugly mixture of feelings throws me back and forth! "

After his arrival in Paris on October 5, 1831, Chopin had first contacts with Polish emigrants who had come from Poland as part of the so-called Great Emigration (Polish: Wielka Emigracja ). Soon Chopin was a guest in the most important and influential Parisian salons. The rooms in the building of Camille Pleyel's piano factory at 9 rue Cadet were to be of particular importance to Chopin . It took place here on February 25, 1832 through the mediation of the pianist Friedrich Kalkbrenner, who was also a partner in the Pleyel company, Chopin's first concert took place in Paris. It was a great success and laid the foundation for Chopin's successful career as a composer, pianist and, above all, as a sought-after piano teacher for members of the aristocracy. The printed program of this Grand Concert Vocal et Instrumental, donné par M. Frédéric Chopin, de Varsovie has been preserved. Chopin played his Piano Concerto in E minor, Op. 11 (not the one in F minor, Op. 21, as was long believed), his Grandes Variations brillantes sur un thème de Mozart, Op. 2, and together with Friedrich Kalkbrenner, Camille Stamaty(instead of the originally planned Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy), Ferdinand Hiller, George Osborne and Wojciech Sowiński the Grande Polonaise précédée d'une Introduction et d'une Marche op. 92 by Kalkbrenner in an arrangement for six pianos.

Commemorative plaque on Chopin's apartment on Square d'Orléans: "Frédéric Chopin lived in this house from 1842 to 1849". The plaque was installed on October 26, 1919 by the Société Chopin in Paris on the initiative of Édouard Ganche .

In the 18 years that Chopin spent essentially in Paris from 1831 to his death in 1849, he lived in nine different apartments.

| Frédéric Chopin's Parisian apartments | Period |

|---|---|

| 27 boulevard Poissonnière | Early October 1831 - June 1832 |

| 4 cité Bergère | Fall 1832 - mid June 1833 |

| 5 rue de la Chaussée d'Antin | June 1833 - September 1836. From 1834 together with Jan Matuszyński . |

| 38 rue de la Chaussée d'Antin | 2nd half of September 1836 - September 1839. Together with Julian Fontana . |

| 5 rue Tronchet | October 1839 - early November 1841 |

| 16 rue Pigalle (since April 1, 1997 rue Jean-Baptiste-Pigalle) | Beginning of November 1841 - September 1842 in a separate pavilion next to the one in which George Sand lived. |

| 9 square d'Orléans | August 5, 1842 - late May 1849 (From April to November 1848 Chopin was in England and Scotland.) |

| 74 rue de Chaillot | End of May 1849 - 1st half of September 1849 |

| 12 place Vendôme | Mid-September 1849 until his death on October 17, 1849 |

Economic situation

Chopin made his living primarily by taking piano lessons . In Chopin's day the piano was a widespread instrument that was mainly learned by women. Its great popularity since the beginning of the 19th century, which was viewed very critically by some observers such as Heinrich Heine in Paris or Eduard Hanslick in Vienna, has several reasons. The social philosopher Max Weber says that the piano is “a bourgeois house instrument” in terms of its “musical essence”. Due to its simple sound generation from the user's point of view, it opens up direct access, even for laypeople, to various types of music, from simple children's songs to virtuoso concert literature.

Due to his early intercourse in the Parisian salons of the aristocracy and also in the world of politics and finance, the protection of the Polish noble emigrants and not least because of the resounding success of his first concert in Paris (February 25, 1832), Chopin was soon a sought-after, good Paid piano teacher, whose students came mainly from the aristocracy and the influential political and financial milieus.

From 1833 Chopin had a regular income, which he was able to top up with fees for concerts and compositions, which he sometimes offered to publishers in France, England and Germany at the same time.

As can be seen from letters to his friends, Chopin was sometimes disappointed with the reward and the handling of his compositions. Then he was not afraid to use insulting and - from today's point of view - sometimes anti-Semitic statements.

Chopin had an elaborate lifestyle in Paris. He afforded a private carriage, had servants, and valued expensive clothing. He taught about five hours a day. The teaching fee was 20 francs. (On purchasing power: a carriage ride through Paris cost 1 franc). He asked for 30 francs per hour for house calls, which is around € 200 today. One lesson lasted 45 minutes, but he extended it with his talented students. Lessons from Chopin became a status symbol. During his time in Paris he had a total of around 150 students.

| The public concerts of Frédéric Chopin | time | place | program |

|---|---|---|---|

| Several soloists took part in most of the concerts. Only Chopin's contributions are listed here . | |||

| Warsaw | February 24, 1818 | Pałac Radziwiłłów (Radziwiłł Palace) |

- Adalbert Gyrowetz: Piano Concerto in G minor |

| Warsaw | February 24, 1823 | Gmach Towarzystwa Dobroczynności (House of the Charity Society) |

- Ferdinand Ries: piano concerto |

| Warsaw | 3/3/1823 | Gmach Towarzystwa Dobroczynności (House of the Charity Society) |

- John Field: Piano Concerto No. 5 in C major |

| Bad Reinerz (Duszniki-Zdrój) |

August 11, 1826 | Hall of the bath | Program not known |

| Bad Reinerz | August 16, 1826 | Hall of the bath | Program not known |

| Vienna | August 11, 1829 | Kärntnertortheater | - Variations on “Là ci darem la mano” from Mozart's Don Giovanni in B flat major op. 2 - Improvisations on a given theme from the opera La dame blanche ( The White Lady ) by François-Adrien Boieldieu and the Polish folk song “Oj chmielu, chmielu "(" 0 hops, hops ") |

| Vienna | August 18, 1829 | Kärntnertortheater | - Krakowiak. Grand Rondeau de concert in F major op.14 |

| Warsaw | December 19, 1829 | Dawna Resursa (Ancient Resource) |

- Piano accompaniment and improvisation on themes from Joseph Drechsler and Józef Damses The Millionaire Farmer or the Girl from the Enchanted World |

| Warsaw | March 17, 1830 | Teatr Narodowy (National Theater) |

- Piano Concerto in F minor, Op. 21 (published as No. 2 in 1836) - Grande Fantaisie sur des airs nationaux polonais in A major, Op. 13 |

| Warsaw | March 22, 1830 | Teatr Narodowy (National Theater) |

- Piano Concerto in F minor, Op. 21 (published as No. 2 in 1836) - Krakowiak. Grand Rondeau de concert in F major op. 14 - improvisation on themes from Polish operas by Jan Stefani and Karol Kurpiński |

| Warsaw | October 11, 1830 | Farewell concert at Teatr Narodowy | - Piano Concerto in E minor, Op. 11 (published in 1833 as Concerto No. 1) - Grande Fantaisie sur des airs nationaux polonais in A major, Op. 13 |

| Wroclaw (Wroclaw) |

November 8, 1830 | resource | - Rondo from the Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11 - Improvisation on a theme from The Mutes from Portici by Daniel-François-Esprit Auber |

| Vienna | June 11, 1831 | Kärntnertortheater | - Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11. |

| Munich | August 28, 1831 | Hall of the Philharmonic Society | - Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11. - Grande Fantaisie sur des airs nationaux polonais in A major, Op. 13. |

| Paris |

First concert in Paris February 25, 1832 |

Salons Pleyel (9 rue Cadet) | - Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor op.11 - Friedrich Kalkbrenner: Grande Polonaise précédée d'une Introduction et d'une Marche op.92 (version for six pianos, together with Kalkbrenner, Stamaty, Hiller, Osborne, Sowiński) - Variations on “Là ci darem la mano” from Mozart's Don Giovanni in B flat major op. 2 |

| Paris | May 20, 1832 | Salle du Conservatoire (2 rue Bergère; benefit concert) | - Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11 (1st movement) |

| Paris | March 23, 1833 | Salle du Wauxhall (former rue Samson) | - Johann Sebastian Bach: Allegro from the Concerto for Three Pianos in A minor BWV 1063 (together with Franz Liszt and Ferdinand Hiller) |

| Paris | 3 April 1833 | Salle du Wauxhall | - Henri Herz: Grand morceau pour deux pianos à huit mains sur le choeur du Crociato de Meyerbeer (together with Franz Liszt, Jacques and Henri Herz) |

| Paris | April 2, 1833 | Théâtre-Italy (benefit concert) |

- George Onslow: Sonata in F minor for piano four hands op.22 (with Franz Liszt) |

| Paris | April 25, 1833 | Hotel de Ville | - Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11 (2nd and 3rd movements) |

| Paris | December 15, 1833 | Salle du Conservatoire | - Johann Sebastian Bach: Allegro from the Concerto for Three Pianos in A minor BWV 1063 (together with Franz Liszt and Ferdinand Hiller) |

| Paris | December 14, 1834 | Salle du Conservatoire (benefit concert) |

- Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11 (2nd movement) |

| Paris | December 25, 1834 | Salon de Stoepel (6 rue de Monsigny) | - Ignaz Mocheles: Grande Sonate pour piano à quatre mains op 47th - Franz Liszt: Grand Duo sur des Songs Without Words de Mendelssohn (together with Franz Liszt) |

| Paris | February 22, 1835 | Salons d'Érard (13 rue du Mail) | - Ferdinand Hiller: Grand Duo pour deux pianos op.135 (together with Ferdinand Hiller) |

| Paris | March 15, 1835 | Salons de Pleyel | - Program unknown (together with Kalkbrenner, Herz, Hiller and Osborne) |

| Paris | 5 April 1835 | Théâtre-Italy (benefit concert for the Polish refugees) |

- Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor or No. 2 in F minor |

| Paris | April 26, 1835 | Salle du Conservatoire (benefit concert) |

- Grande Polonaise brillante précédée d'un Andante spianato op 22nd |

| Rouen | March 12, 1838 | Hotel de Ville (town hall) | - Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11 |

| Paris | March 3, 1838 | Salons de Pape (10 rue de Valois) | - Beethoven-Alkan: Allegretto and Finale of the 7th Symphony arranged for two pianos and eight hands (together with Zimmermann, Alkan and Gutmann) |

| Paris | April 26, 1841 | Salons Pleyel (Salle de concert, 22 rue Rochechouart) | - Preludes from op. 28 - Ballad No. 2 in F major, op. 38 - Scherzo No. 3 in C sharp minor, op. 39 - Mazurkas - Nocturnes - Selection of studies |

| Paris | February 16, 1848 Last concert in Paris |

Salons Pleyel (Salle de concert, 22 rue Rochechouart) | - Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano trio in G major KV 564 - Sonata in G minor for piano and violoncello op.65 (without the 1st movement, together with Franchomme) - a nocturne - Barcarolle in F sharp major op.60 - Selection of studies - Berceuse in D flat major op. 57 - Preludes from op. 28 - Mazurken - Waltz, at the end of the concert waltz D flat major op |

| London | June 23, 1848 | Singer Adelaide Sartoris-Kemble's Salon, 99 Eaton Place | - Berceuse D flat major op.57 - Nocturnes - Mazurkas - Waltz |

| London | 7. 7. 1848 | Lord Falmouth, St. James Square 2 | - Berceuse D flat major op.57 - smaller individual pieces - Scherzo No. 1 B minor op.20 - a ballad - three etudes from op.25 (No. 1 A flat major, No. 2 F minor, No. 7 c sharp minor) - Preludes from op.28 |

| London | November 16, 1848 | City Hall, Guild Hall | - Etudes op. 25 No. 1 and 2 - no further information available |

| Manchester | August 28, 1848 | Concert Hall | - a ballad - Berceuse D flat major op. 57 - smaller pieces |

| Glasgow | September 27, 1848 | Merchant's Hall | - a ballad - Berceuse in D flat major op.57 - Andante spianato from op.22 - Impromptu No. 2 in F sharp major op.36 - Selection of studies - Preludes from op.28 - Nocturnes in C sharp minor, D flat major op. 27 No. 1/2. - Nocturnes in F minor, E flat major op.55 No. 1/2 - Mazurken op.7 - Waltz op.64 |

| Edinburgh | October 4, 1848 | Hopetowns Rooms | - similar program as in Glasgow - Largo (it is either the Largo in E flat major (KK IVb / 2), called Modlitwa Polaków “Prayer of the Poles”, or the 3rd movement of the Sonata No. 3 in B minor op . 58) |

Overall, Chopin performed in around 40 public concerts: in Warsaw, Bad Reinerz (today: Duszniki-Zdrój ), Breslau (today: Wrocław), Vienna, Munich, London, Rouen, Manchester, Glasgow, Edinburgh and in Paris. As was customary at the time, several soloists took part in the varied programs, with Chopin not always being the main soloist. Sometimes they were benefit concerts or concerts by other musicians, to whose success the famous colleagues contributed through their participation. In contrast to Liszt, Chopin preferred the intimate atmosphere of the salons to the large concert halls in which his delicate playing was not played out.

Social life in Paris and friends

In 1832, Chopin became one of the first members of the Société littéraire polonaise (French "Polish Literary Society", Polish Towarzystwo Literackie w Paryżu ) founded in Paris on April 29, 1832 by Polish emigrants . The first president was Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski , and vice-president Ludwik Plater .

In Chopin's time there were around 850 salons in Paris, semi-private gatherings of friends and art lovers, which were common in large houses, and who met with a certain regularity, weekly or monthly, for dinner, conversation and music. Those who frequented these circles of the Parisian bourgeoisie had achieved a social reputation. Chopin probably felt most at home in the artists' salons, where he socialized with his own kind and ensured an intellectual level by making music and exchanging ideas.

A sign of the social recognition Chopin enjoyed in Paris is the invitation of the royal family to play in the Tuileries palace . Each time he received a gift with the engraved inscription: Louis-Philippe, Roi des Français, à Frédéric Chopin ("Louis Philippe, King of the French, to Frédéric Chopin").

Chopin's circle of friends included the poets Alfred de Musset , Honoré de Balzac , Heinrich Heine and Adam Mickiewicz , the painter Eugène Delacroix , the musicians Franz Liszt , Ferdinand von Hiller , and the cellist Auguste-Joseph Franchomme . Chopin was also several times a guest of the Marquis Astolphe de Custine , one of his ardent admirers, in his château in Saint-Gratien . Among other things, he played in Custine's Salon, such as the Etudes op. 25: 1-2 and the then unfinished Ballad op. 38.

Of particular importance to Chopin was Julian Fontana , of the same age , with whom he had a lifelong friendship since childhood. Until his emigration to the United States (1841), he was indispensable for Chopin as a copyist , arranger , secretary and impresario , who also negotiated with the publishers and took care of his friend's everyday business. After Chopin's death he published - against the will of the composer, but with the consent of the family - some posthumous works with the opus numbers 66–73 (published 1855) and opus 74 (published 1859).

The pianist, music publisher and piano manufacturer Camille Pleyel was one of the most important people in Chopin's time in Paris from the start. It was a professional collaboration characterized by friendship and mutual respect that benefited both of them. The pianos and grand pianos, which Pleyel made available to Chopin free of charge, were, for Chopin, as he put it, the non plus ultra of piano making ; Chopin was a valued advertising medium for Pleyel, according to the company's sales statistics.

Travel and engagement: Aachen and Karlsbad (1834), Leipzig (1835)

In 1834, the doctor and close childhood friend Jan Matuszyński moved into his apartment at Chaussée-d'Antin No. 5 and lived there with him until 1836. In May 1834 Chopin traveled to Aachen for the Lower Rhine Music Festival. He visited Cologne, Koblenz and Düsseldorf, where he met Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, whom he already knew from Paris. In the summer he traveled to Karlovy Vary, where he met his parents. After his onward journey to Dresden, he met the Wodziński family again in Marienbad in 1836, where they were taking a cure and - despite the protests of their uncle - it was said that Chopin and Maria Wodzińska were engaged . Maria's mother allegedly insisted that this be kept secret until the summer of the following year. There is also no solid evidence for this.

In 1835 Chopin made the acquaintance of Clara and Robert Schumann in Leipzig, mediated by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, and in 1836 with Adolph von Henselt in Karlsbad. Only a year later, the alleged engagement to Maria Wodzińska was supposedly dissolved again - probably at the insistence of her parents because of Chopin's poor health.

In 1836, the pianist, composer and close childhood friend Julian Fontana moved in with Chopin in Chaussée-d'Antin as the successor to Jan Matuszyński .

Polish patriot

Despite his success and strong roots in the cultural life of Paris and a large circle of friends of Polish emigrants, Chopin longed for Poland and his family; As is evident from his letters and statements, he suffered from constant homesickness. Throughout his life Chopin insisted on the Polish pronunciation of his French surname: [ˈʃɔpɛn] . He expressed his sense of home and his national pride particularly in his mazurkas and polonaise. The expression of longing, nostalgia and melancholy (Polish "żal" ) became a characteristic of his music , along with the emphasis on Poland ( Polish "polskość" ). As an ardent Polish patriothe was entirely on the side of the resistance against tsarist Russia, which was occupying the so-called Congress Poland . If there was a Polish charity bazaar before Christmas, Chopin helped organize it.

His patriotism and longing for Poland remained a source of inspiration for many of his compositions. Inspired by the uprising, he wrote his revolutionary etude (Opus 10 No. 12).

1837 Chopin received over Count Carlo Andrea Pozzo di Borgo the offer, court composer and -pianist of Tsar Nicholas I to be. The background was a concert that Chopin had given in May 1825 on an aeolomelodicum (an organ variant) in front of his predecessor, Tsar Alexander I , in the Trinity Church in Warsaw . Chopin turned down the tsar's offer.

Chopin and George Sand

Chopin first saw the successful writer Amandine Aurore Lucile Dupin de Francueil, aka George Sand , in the fall of 1836 at a reception at the Hôtel de France in Paris, where Franz Liszt and his lover Marie d'Agoult, coming from Switzerland, were relegated. His first reaction to this man, dressed in men's clothing and smoking cigars, was disapproval. The 27-year-old Chopin got into a life crisis because of an unhappy love for the then 18-year-old Maria Wodzińska. Maria Wodzińska and George Sand, however, were fundamentally different. Unlike Wodzińska, George Sand was a confident, provocative, and contradicting personality. The initiative for the relationship with Chopin came from her. Your nine-year relationship with Chopin, a love affair, initially characterized by trust, mutual appreciation, tenderness, but later also by jealousy, hatred and distrust, leaves some questions unanswered.

George Sand was a passionate woman who had a number of mostly younger lovers. The relationship between the then 32-year-old and Chopin, who was six years younger, was shaped from the start by very different emotional and sexual needs. George Sand destroyed numerous letters addressed to her, making the relationship difficult to assess. Clear indications, however, are a thirty-two page letter from George Sand to Chopin's friend Wojciech Grzymała(1793–1871) from late May 1838 in which she asked him for advice. She found herself in a conflict because she still had a relationship with the writer Félicien Mallefille, but on the other hand had developed an affection for Chopin, about whose feelings towards her she was in the dark. In any case, there must have been a closer encounter between the two.

| • Letter from George Sands to Albert Grzymala (French) |

- George Sand à Albert Grzymala, fin May 1838 (unabridged excerpt)

|

“And since I am telling you everything, I will also tell you that there was one thing that I disliked about him. […] He seemed, in the manner of bigots, to despise gross human desires and to blush at his temptations, and he seemed to be afraid of tainting our love with a stronger excitement. This way of looking at the ultimate love union has always repelled me. If this last embrace is not as sacred and pure as everything else, there is no virtue in abstaining from it [...] Can there ever be love without a single kiss and a kiss of love without lust? "

During the nine-year relationship, the couple alternated between Paris and George Sand's country estate, now the Maison de George Sand , in Nohant-Vic .

Stay on Mallorca (November 9, 1838 - February 13, 1839)

On October 18, 1838, George Sand began a trip to Mallorca with their children Maurice and Solange on medical advice. It was hoped that Maurice's health, suffering from rheumatism, would improvewas sick. Since Chopin suffered from tuberculosis and hoped for an improvement through a milder climate, he traveled to the family on October 27, 1838, who were waiting for him in Perpignan. After a boat trip to Barcelona and a five-day stay, the crossing to Mallorca began on November 7, 1838 with the destination Palma, which was reached on November 9, 1838. After various difficulties, the group left Palma and rented a beautifully located villa nearby from November 15, before they had to leave the place for reasons of hygiene - Chopin's lung disease had alerted the doctors and authorities - and finally settled in the abandoned Carthusian monastery Valldemossa where they stayed from December 15, 1838 to February 11, 1839. While Maurice was recovering, Chopin stayed in theValldemossa Charterhouse under a bad star. The premises were cold and damp, and the weather was very bad. In addition, there was the negative attitude of the Mallorcans towards the unmarried couple, and also the suspicion that Chopin's coughing indicated a contagious disease.

Chopin soon showed all signs of pneumonia , as George Sand later complained in writing. On February 13, 1839, after three and a half months, she and Chopin left the island. Despite the relative shortness of the stay in Mallorca, both Chopin and George Sand were severely affected. But in contrast to George Sand, who shared their partly negative experiences in the report Un hiver à Majorque (French Ein Winter auf Mallorca), Chopin reacted less resentfully. The often cited letter of December 3, 1838 about the medical art of the Mallorcans is possibly not meant so maliciously as rather testimony to the self-irony that Chopin often used to deal with his chronic illness.

| • Chopin's letter to Julian Fontana (Polish) |

- Chopin: List do Juliana Fontany, 3 grudnia 1838

|

“The three most famous doctors on the whole island examined me; one sniffed what I spit out, the second knocked where I was spitting from, the third felt and listened to me spitting. One said that I died, the second said - that I would die, the third - that I would die. "

Before leaving, Chopin had asked his friend Camille Pleyel to send him a piano to Mallorca. Since this only arrived in January 1839, he had to be content with a poor instrument in the meantime in Palma and Valldemossa. The 24 Preludes Opus 28 were completed in Mallorca, including the so-called Raindrop Prelude . In the context of these pieces of music, people like to point out how uncomfortable Chopin felt in the uncomfortable surroundings of the monastery. A letter dated December 28, 1838 confirms this assumption. Chopin wrote to Julian Fontana:

| • Chopin's letter to Julian Fontana (Polish) |

- Chopin: List do Juliana Fontany, 28 grudnia 1838

|

“Only a few miles away between the rocks and the sea lies the huge abandoned Carthusian monastery, in which you can imagine me in a cell with a door, a gate that has never been seen in Paris, with no hair, without white gloves, pale as ever . The cell is in the form of a high coffin, the vaulted ceiling is huge, dusty, the window small, in front of the window oranges, palms, cypresses; opposite the window my bed on belts under a Mauritanian, filigree rosette ( German rosette ). Next to the bed a nitouchable ( German "untouchable"), a square folding desk that I hardly ever use for writing, on it a leaden candlestick (here a great luxury) with a candle, Bach, my scribbles and other musical notes ... quietly ... you could scream ... and still be quiet. In a word, I am writing to you from a strange place. "

This letter contrasts with the enthusiastic letter that Chopin wrote from Palma to Fontana in Paris.

According to George Sand, Chopin suffered from hallucinations at that time . Spanish neurologists conclude that the violent visions can best be explained by what is known as temporal lobe epilepsy .

After arriving on the mainland, the group stayed in Barcelona for over a week and arrived on February 24, 1839 by steamer in Marseille, where, on medical advice, because of Chopin's health, they stayed for three months until May 22, 1839 to recover . A sea voyage lasting from May 13th to 18th, 1839 brought Chopin and George Sand on an excursion to Genoa, before they reached Nohant on June 1st, 1839 on their return journey via Arles and Clermont. It was here that Chopin spent his first summer at George Sand's estate.

Two centers of life: Nohant and Paris

| Chopin in Nohant | |

|---|---|

| The works created in Nohant | |

| 1. Summer in Nohant: 1839

(June 1 - October 11) |

Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor op.35 Impromptu No. 2 in F sharp major op.36 Nocturne in G major op.37/2 Scherzo No. 3 in C sharp minor op.39 Trois études (Méthode des Méthodes) in F minor, A flat major, D flat major KK II b, 1-3 Three Mazurkas in B major, A flat major, C sharp minor op.41 / 2,3,4 |

| Summer 1840 Chopin and George Sand did not stay in Nohant |

In Paris, among others: Waltz (Grande Valse) A flat major op.42 Waltz A flat major op.64 Mazurka A minor (Émile Gaillard) KK IIb, 5 Mazurka A minor (Notre Temps) KK IIb, 4 |

| 2nd summer in Nohant 1841

(June 18 - October 31) |

Tarantella A flat major op.43 Polonaise in F sharp minor op.44 Prélude in C sharp minor op.45 Ballade No. 3 A flat major op.47 Two Nocturnes in C minor, F sharp minor op.48 Fantasy in F minor op.49 |

| 3rd summer in Nohant 1842

(May 6th - July 28th and August 9th - September 27th) |

Three Mazurkas in G major, A flat major, C sharp minor op.50 Impromptu No. 3 G flat major op.51 Ballade No. 4 in F minor op.52 Waltz in F minor op. 70/2 Polonaise No. 6 A flat -Dur op 53rd Scherzo no. 4 e-Op. 54 |

| 4. Summer in Nohant 1843

(May 22nd - November 28th) |

Two Nocturnes in F minor, E flat major op.55 Three Mazurkas in B major, C major, C minor op.56 Berceuse D flat major op.57 |

| 5. Summer in Nohant 1844

(May 31-November 28) |

Piano Sonata No. 3 in B minor, Op. 58 |

| 6. Summer in Nohant 1845

(June 13th - December 1st) |

Three Mazurkas in A minor, A flat major, F sharp minor op.59 Barcarolle in F sharp major op.60 Polonaise Fantaisie A flat major op.61 |

| 7. Summer in Nohant 1846

(May 7th - November 11th) |

Two Nocturnes in B major, E minor op.62 Three Mazurkas in B major, F minor, C sharp minor op.63 Two waltzes in D flat major, C sharp minor op.64 Sonata for piano and violoncello in G minor op. 65 |

After returning from Mallorca, Chopin's life in Paris took an orderly course. The winters were dedicated to teaching, social events, cultural life, salons and the few personal appearances. Up to and including 1846, the couple spent the summer stays of several months at George Sand's inherited country estate in Nohant . Chopin spent a total of seven summers in Nohant: 1839 and 1841 to 1846. During this time Chopin found peace and quiet to compose. A number of the most important works were created here. He received friends and debated aesthetic issues with Delacroix. He studied the bel canto repertoire of the 18th century and Luigi Cherubini's Cours de contrepoint et de fugue (German course in counterpoint and fugue ).

From September 29, 1842, Chopin lived and worked in Paris at 9 Square d'Orleans, in the immediate vicinity of George Sand and her friend, Countess Marliani, wife of the Spanish consul, who had arranged the apartments.

End of the relationship (July 1847) and last meeting (April 4, 1848)

The relationship between Chopin and George Sand ended in 1847. On July 28, 1847, George Sand wrote her last letter to Chopin. It ends with the words:

| • Letter from George Sands to Chopin (French) |

- George Sand

|

“Goodbye, my friend, may you be cured of all ills quickly, I can now hope for it (I have my reasons for it) and I will thank God for this wonderful dissolution of an exclusive nine year friendship. Let me know how you are from time to time. It is unnecessary to ever come back to the rest. "

The reason for the separation were the conflicts between two fundamentally different, highly sensitive characters that had been pent up for years. From letters from George Sand to friends it can be deduced that she no longer wanted to lead the life of what she calls a celibate nun and nurse of a difficult, seriously ill and capricious genius. The family quarrels over her daughter were only the immediate cause. That her daughter Solange joined the destitute sculptor Auguste Clésingerhad turned, George refused to accept Sand. Chopin had also heard about Clésinger's unsteady life. He advised Solange just as strongly against - but in the end he stuck to his friendship with her. He accepted her unconditional decision to marry Clésinger and, if necessary, to break with the imperious mother. That was the trigger for family disputes, in which there were fights between the son Maurice and Clésinger or the mother who jumped at the son.

George Sand and Chopin met again by chance on Saturday, March 4, 1848. While leaving Charlotte Marliani's (18, rue de la Ville-Évêque) apartment, Chopin met George Sand. He informed her that her daughter had become a mother four days earlier.

In the story of my life , George Sand writes:

| • From George Sand: Histoire de ma vie (French) |

- George Sand: Histoire de ma vie.

|

“In March 1848 I saw him again for a moment. I squeezed his cold, trembling hand. I wanted to talk to him, but he pulled away from me. [...] I shouldn't see him again. [...] I was told that he had longed for me to the end, mourned me, loved me like a son, but they kept it from me. It was also kept from him that I was always ready to rush to him. [...] For my years of vigilance, fear and devotion, I have been rewarded with years of tenderness, trust and gratitude that an hour of injustice or erring before God could not extinguish. "

The last years (1847–1849)

In the course of 1847 Chopin's health deteriorated seriously. An effective therapy against tuberculosis was not known at the time. Chopin's pupil Jane Stirling , who had worked in the background for Chopin until Chopin's split with George Sand, took on Chopin's concerns after the couple split up and tried to alleviate his increasing material need.

On February 16, 1848, Chopin gave his last concert in Paris in the Pleyel concert hall at 20 rue Rochechouart, which was held in front of a select audience. There were only 300 tickets. The program included a piano trio by Mozart, Chopin's cello sonata in G minor op. 65 (without the 1st movement), a nocturne, the Berceuse op. 57, the Barcarolle op. 60, plus a selection of etudes, preludes, and mazurkas and waltz. The critics pointed out the concert as an unusual event (article in the Gazette Musicale of April 20, 1848).

Journey to England and Scotland (April 19, 1848 - November 23, 1848)

After the outbreak of the revolution in Paris on February 22, 1848, the so-called February Revolution , which ended with the king's flight to England and the proclamation of the republic of the July monarchy , Chopin felt increasingly uncomfortable because of the ongoing unrest in Paris. Many of his students left Paris, his financial situation deteriorated due to a lack of income.

Under the influence of his student Jane Stirling, who had been taking lessons from Chopin for years and had developed affection for her teacher, Chopin made the decision to travel to England and Scotland for a while, although he could well imagine settling there permanently. He left Paris on April 19, 1848 and arrived in London on April 20. Jane Stirling had traveled to London beforehand with her widowed sister to prepare for Chopin's arrival. The journey, which lasted about seven months in total, was extremely exhausting for Chopin and brought him to the brink of physical collapse, because Jane Stirling imposed a grueling program of visits with concerts on Chopin's family and thus prevented the much-needed rest. Jane Stirling had hoped in vain to marry Chopin. He found her unattractive and boring, but was grateful for her extreme care, even though it made him feel restricted and restricted.

Soon after his arrival, Chopin was invited to the salons of the London upper class, where he met well-known writers such as Charles Dickens and was given the opportunity to supplement his finances by teaching noble ladies. On May 15, 1848, Chopin played at a reception in the presence of Queen Victoria. Concerts in London followed on June 23, 1848 (program: Berceuse op.57, Nocturnes, Mazurken, Waltz) and on July 7, 1848 (program: Berceuse op.57, Scherzo in B minor, op.20, a ballad, three Etudes from op. 25 [No. 1 in A flat major, No. 2 in F minor, No. 7 in C sharp minor] and some preludes). At the invitation of Jane Stirling, Chopin went to Scotland on August 5, 1848. From here, Chopin had to return to a concert in Manchester on August 28, 1848, where he played solo pieces (a ballad, the Berceuse op. 57 and other pieces) in the Concert Hall as part of an orchestral concert in front of 1,500 listeners. In Scotland, Chopin was in poor physical and mental health and suffered from the obligations imposed on him. This was followed by concerts in Glasgow on September 27, 1848 (program: a ballad, Berceuse op.57, Andante spianato from op.22,

Chopin was so weak physically that he sometimes had to be carried up the stairs. After his return to London on October 31, 1848, Chopin played, despite his severely impaired health, on November 16, 1848 as a favor in the Guild Hall in a benefit concert in favor of Polish compatriots.

The Last Time in Paris (November 23, 1848 - October 17, 1849)

In a depressed mood, Chopin returned to Paris on November 23, 1848. On the whole, the stay in England and Scotland was a failure. The dwindling forces, but also the falling demand due to the unrest, made a regular teaching activity much more difficult. This created a financial bottleneck, especially as Chopin's savings were almost exhausted. Jane Stirling helped out with a large sum of money. Chopin's state of exhaustion persisted. The doctors recommended staying in the country to alleviate the symptoms. At the end of May 1849, Chopin moved into an apartment in the then still rural area of Chaillot (Rue Chaillot 74). On June 22, 1849, Chopin suffered two blood attacks at night. Hopes of recovery finally faded when doctors diagnosed terminal tuberculosis. The thought of death had accompanied Chopin all his life. His father, youngest sister, and two closest friends had all died of tuberculosis.

Chopin wrote a letter to his sister Ludwika Jędrzejewicz pleading with her husband and daughter to come to him. They arrived in Chaillot on August 9, 1849. After a brief recovery, the doctors advised to move. The Paris friends and Jane Stirling then bought him his last apartment at 12 Place Vendôme , which consisted of three rooms and two anterooms. They also ensured that Chopin did not suffer any material shortages in the last months of his life, especially since he could neither teach nor compose because of his state of health and was therefore ultimately destitute.

On September 15, 1849, he received the sacraments of death . On the same day Delfina Potocka came to Paris from Nice. She sang, accompanying herself on the piano, to the great delight of Chopin's arias by Italian composers (Bellini, Stradella, Marcello). Franchomme and Marcelina Czartoryska played the beginning of Chopin's Cello Sonata op. 65. At the beginning of October 1849 Chopin decreed that all unfinished and not yet published scores should be burned.

Death and Burial (October 17-30, 1849)

Chopin died on October 17, 1849 at two in the morning at the age of 39, probably of tuberculosis . An examination of the heart placed in cognac in 2017 found that Chopin suffered from pericarditis caused by tuberculosis.

At the time of his death, six people were probably waking up by Chopin's bed: his sister Ludwika Jędzejewicz, Solange Clésinger, Teofil Kwiatkowski, Abbé Alexander Jełowicki, Adolf Gutmann and Dr. Jean-Baptiste Cruveil here. The following morning, Auguste Clésinger took Chopin's death mask off and made a cast of his left hand. Teofil Kwiatkowski and Albert Graefle painted or drew the head of the deceased. Doctor Jean Cruveilher, who treated Chopin to his end, performed a partial autopsy during which he removed Chopin's heart. Chopin had asked that his heart be brought home. The body of Chopin remained in the apartment for two more days and was then taken to the crypt of the La Madeleine church after the embalming .

About 3000 mourners came to Chopin's funeral mass on October 30th at 11 a.m. in the La Madeleine church . When the coffin was carried from the crypt to the upper church, the orchestra of the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire ( French concert company of the Conservatory ) under the direction of Narcisse Girard played an orchestral version of the funeral march from Chopin's piano sonata in B flat minor, made by Napoléon-Henri Reber opus 35 . Furthermore, the organ, played by Louis James Alfred Lefébure-Wély, played the Preludes No. 4 in E minor and No. 6 in B minor from opus 28. The conclusion was Mozart's Requiem, a wish of Chopin. The funeral procession to the Père-Lachaise cemetery was led by Prince Adam Czartoryski and Giacomo Meyerbeer . Alexander Czartoryski, Marcelina's husband, Auguste Franchomme , Eugène Delacroix and Camille Pleyel walked by the side of the coffin . Chopin's sister Ludwika walked behind the coffin with her daughter, Jane Stirling and many who were close to Chopin. At Chopin's express request, his sister Ludwika secretly brought his heart back to Poland, where she kept it in her apartment in Warsaw. (For the further fate of Chopin's heart: see below .)

Ludwika paid for the funeral. Jane Stirling took over the travel expenses of Ludwika and her daughter Magdalena. She bought the Pleyel grand piano (No. 14810) that Camille Pleyel had given Chopin, as well as the rest of Chopin's furniture and valuables, including his death mask. Jane Stirling later used the rest of the household effects to design a museum room in Scotland in memory of Chopin, and years later she bequeathed these items to Chopin's mother in Warsaw. Some of these memorabilia are exhibited in the Frédéric Chopin Museum in Warsaw (Muzeum Fryderyka Chopina w Warszawie) .

On the anniversary of Chopin's death, on October 17, 1850, Auguste Clésinger unveiled the tomb he designed with Fryderyk Chopin's medallion. Inside the plinth, Jane Stirling had an iron box deposited, which contained various objects: a sheet of paper with Chopin's birth and death dates and the sentence: “We expect the resurrection of the dead and eternal life”, and also Polish earth, a silver one Cross that belonged to Chopin, a small medallion from Tellefsen and coins from the year Chopin was born and died. Jane Stirling scattered the Polish soil that Ludovika had given her on the grave.

Chopin as an artist

Chopin was versatile. In addition to his talent as a composer, pianist, improviser, virtuoso and piano teacher, his comedic gift of imitating people was also known - an ability fed by extraordinary powers of observation with which he often entertained friends. This talent as an actor remained one of his social domains: in 1829 he parodied the appearance and behavior of Austrian generals in Vienna and was as successful as a pianist. He also took drawing lessons from Zygmunt Vogel - and didn't just use drawing to make caricatures .

Chopin as a composer

Chopin composed almost exclusively for the piano. His preferred forms include mazurkas , waltzes , nocturnes , polonaises , etudes, impromptus , scherzi , and sonatas .

Chopin's compositions often developed from improvisations . George Sand describes the great difficulties that Chopin had in recording his ideas, which were already fully executed on the piano, on paper. Improvisation was much more important then than it is today, both in training and in concerts. Chopin was considered one of the best improvisers of his time.

In addition to pure piano music and the two piano concertos (No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11 (1830, published 1833) and No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 (1829, published 1836)), Chopin composed works for the following genres:

- Songs . They were not published until after his death (1849) in 1859, 1872 and 1910, for the most part under the opus number 74.

-

Chamber music . Three works for piano and violoncello:

- Introduction et Polonaise brilliant in C major Op. 3 (1829/30),

- Sonata in G minor op.65 (1845/46),

- Grand Duo concertant in E major on themes from Robert le diable by Giacomo Meyerbeer , without opus number (composed with Auguste-Joseph Franchomme ) ( 1831).

- Trio in G minor for piano, violin and violoncello op.8 (1828/29).

Sources of inspiration and influences

Chopin took over - and exaggerated - the brilliant virtuoso literature . The influence of Ignaz Moscheles , Friedrich Kalkbrenner , Carl Maria von Weber , Johann Nepomuk Hummel and (who was also trained by Elsner) Maria Szymanowska is clear. Instructed in concentrated and meticulous work by Elsner, Chopin sometimes spent years honing drafts of compositions. "He [...] repeated and changed a measure a hundred times, wrote it down and deleted it just as often, in order to continue his work the next day with the same meticulous, desperate persistence."

In addition to the melodies and the virtuoso piano setting of his compositions, there is a highly expressive harmony that confidently deals with chromatics , enharmonics and altered chords and creates new effects. His teacher Elsner encouraged Chopin to turn to Polish folk dances and folk songs . Its elements can be found not only in the polonaises , mazurkas and Krakowiaks , but also in other works without naming reference. Chopin's models were Johann Sebastian Bach and Domenico Scarlatti, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and the Italian composers committed to bel canto such as Vincenzo Bellini . In response to Elsner's suggestion that he would not write operas, Chopin replied that composers would have to wait years for their operas to be performed.

| • Quote from Frédéric Chopin (Polish) |

- Frédéric Chopin

|

“They pounced on me (with the charge) that instead of writing a national opera or a symphony, I tickle my nerves in the salons and write stupid exercises. If not an opera, then I shouldn't be able to do anything but mazurkas and polonaise, but if you don't feel it, then I won't point my finger at the Polish in my scores. "

Chopin as a pianist and piano teacher

Chopin's contemporaries describe his playing or his interpretation as changeable, never fixed, but spontaneous. “To hear the same piece by Chopin twice was to hear two different pieces, so to speak”. Princess Maria Anna Czartoryska described it like this:

“Just as he constantly had to correct, change, modify his manuscripts - to the point that his unfortunate editors confused the same work - he seldom presented himself in the same state of mind and emotions: it was therefore seldom the same The composition played identically. "

Although Chopin mainly taught students who came from circles of the wealthy aristocracy, he also paid attention to their talent when selecting them. Only a few of Chopin's students later became concert pianists. One of his most promising students, Carl Filtsch (1830–1845), died as a teenager. Marie Moke-Pleyel, who - of almost the same age - may not be directly regarded as Chopin's pupil, but as an intimate connoisseur of his music, and who was still a professor at the Royal Conservatory in Brussels , became successful .

Chopin taught his students his very personal understanding of music. The following statement, Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger calls it a "profession de foi esthétique" (German: aesthetic creed), made Chopin on the occasion of a conversation about a concert that Liszt gave on April 20, 1840 at Érard.

«La dernière chose, c'est la simplicité. Après avoir épuisé toutes les difficultés, après avoir joué une immense quantité de notes et de notes, c'est la simplicité qui sort avec tout son charme comme le dernier sceau de l'art. Quiconque veut arriver de suite à cela n'y parviendra jamais; on ne peut commencer par la fin. Il faut avoir étudié beaucoup, même immensément pour atteindre ce but; ce n'est pas une chose facile. »

“The last thing is simplicity. After all difficulties have been exhausted, an immense amount of notes played, it is simplicity that emerges with its charm, like the final seal of art. Anyone who wants to do this immediately will never succeed; one cannot begin with the end. You have to have studied a lot, a tremendous amount, to achieve this goal; that's not an easy thing. "

Sketches for a piano school

Chopin only left sketches for a piano school that were published late, first by Alfred Cortot (1877–1962) and more recently by Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger , who also wrote Chopin vu par ses élèves ( German Chopin from the perspective of his students ) covers all issues related to this topic.

Chopin insisted on a piano stool that was low by contemporary standards so that the elbows were level with the white keys. The pianist should be able to reach all of the keys on either end of the keyboard without bending to the side or moving his elbows. In the initial position of the fingers, the thumb of the right hand is on "e", the second finger on "f sharp", the third on "g sharp", the fourth on "a sharp" (= "b") and the fifth finger on "h ". The fingers were trained from the basic position with the hand held calm and relaxed.

He often used the phrase “dire un morceau de musique” (French “recite a piece of music”), in keeping with the baroque concept of the “sound speech” of the historical performance practice according to Nikolaus Harnoncourt . The prerequisite for this was Chopin's unconventional finger training. Chopin did not try, as is often the case today, to correct the natural imbalance of the fingers through exercises, but rather each finger should be used according to its own characteristics. He valued the thumb as the “strongest and freest finger”, the index finger as the “most important support”, the middle finger as the “great singer” and the ring finger as “his worst enemy”.

The relaxed hand position necessary for an appropriate touch explains Chopin's preference for black keys. It allows the longer middle fingers to be in a comfortable position as a prerequisite for a virtuoso and expressive game.

In the game, emotional involvement should flow into the interpretation. Chopin was against any mannerisms and pathetic movements. A pianist should not present himself and his feelings to the audience and thus put himself in the foreground, but the work. He also rejected the stage events aimed at large and loud show effects in the manner of Niccolò Paganini and Franz Liszt for himself. Chopin recommended, in keeping with contemporary piano schools (Czerny, Hummel Kalkbrenner), that his students should let their fingers fall freely and keep their hands in the air without weight. Elisabeth Calandwill later call this the "feather-light arm". When playing the scales and exercises, the accent should be shifted to different tones to achieve evenness. Here Chopin was the forerunner of later practice practices, for example Alfred Cortot's piano pedagogy, where the rhythmic variants are recommended for overcoming technical problems. Chopin often used the term "souplesse" (French "suppleness"). It was the basis of physiologically correct piano playing. Here, too, modern piano pedagogy is based on Chopin's point of view, in that it demands suppleness and relaxation in the prevention of game damage. He also encouraged his students to sing the pieces and recommended a visit to the opera to be inspired by Italian bel canto.

Problems of performance practice

In contrast to the Chopin interpretation of the late nineteenth and first half of the 20th century, which largely depended on the intuition and personal musical taste of the interpreters, efforts were also made to reduce the basic elements of performance practice to one of the most reliable original texts to provide a scientific basis. By researching the historical and sociocultural circumstances, the performance practice has also become more objective, especially since knowledge of the old instruments, their construction, their variety and their sound, which differs from today's instruments, is also included.

Knowledge of the baroque tradition to which Chopin refers is necessary for the appropriate presentation of Chopin's compositions. Thus elements of improvisation with the practice of decorating and the variants are recourse to old forms of music-making or their continuation. This also applies to the important area of bel canto with the central concept of rubato.

Tempo rubato