religion

Religion (from Latin religio 'conscientious consideration, care' , to Latin relegere 'consider, mindful' , originally meant is "the conscientious care in observing signs and regulations") is a collective term for a multitude of different worldviews , the basis of which is the respective Belief in certain transcendent (supernatural, supernatural, supernatural) powers is, as well as often in sacred objects.

The teachings of a religion about the sacred and the transcendent cannot be proven in the sense of the philosophy of science , but are based on the belief in communications from certain mediators ( founders of religions , prophets , shamans ) about intuitive and individual experiences. Such spiritual communications are called revelation in many religions . Statements about spirituality and religiosity are views without the need for explanation, which is why religions put these into parables and symbol systems in order to be able to bring their content closer to many people. Skeptics and critics of religion , on the other hand, only seek controllable knowledge through rational explanations.

Religion can normatively influence values , shape human behavior, actions, thoughts and feelings, and in this context fulfill a number of economic, political and psychological functions. These comprehensive characteristics of religion carry the risk of the formation of religious ideologies .

In the German-speaking world, the term religion is mostly used for both individual religiosity and collective religious tradition. Although both areas in human thought are extremely diverse, some universal elements can be formulated that are found in all cultures of the world. In summary, these are the individual desires for finding meaning, moral orientation and explanation of the world, as well as the collective belief in supernatural powers that in some way influence human life; also the striving for the reunification of existence on this side with its origin on the other side. However, some of these standard declarations are criticized.

The world's largest religions (also known as world religions ) are Christianity , Islam , Hinduism , Buddhism , Daoism , Sikhism , Jewish religion , Bahaitum and Confucianism (see also: List of Religions and Worldviews ). The number and variety of forms of historical and contemporary religions far exceeds the number and variety of forms of world religions.

Premodern cultures invariably had a religion. Religious world views and systems of meaning are often part of long traditions . Several religions have related elements, such as communication with transcendent beings within the framework of salvation teachings , symbol systems , cults and rituals, or they build on one another, such as Judaism and Christianity. The creation of a well-founded system of religions, which is derived from the relationships between the religions and their history of origin, is a requirement of religious studies that has not yet been met.

Some religions are based on or have adopted philosophical systems in the broadest sense . Others are more politically, sometimes even theocratic ; still others are mainly based on spiritual aspects. Overlaps can be found in almost all religions, and especially in their reception and practice by the individual. Numerous religions are organized as institutions ; in many cases one can speak of a religious community .

Religious studies , the history of religion , the sociology of religion , the ethnology of religion , the phenomenology of religion , the psychology of religion , the philosophy of religion and, in many cases, sub-areas of the theology concerned deal with the scientific research of religions and ( in some cases ) religiosity . Concepts, institutions and manifestations of religion are questioned selectively or fundamentally through forms of religious criticism.

The adjective “religious” has to be seen in the respective context: It denotes either “the relation to (a certain) religion” or “the relation to the religiosity of a person”.

Attempts at definition

There is no generally accepted definition of religion, just various attempts at definition . Substantialist and functionalist approaches can be roughly distinguished. Substantialistic definitions try to determine the essence of religion in relation to the sacred , transcendent or absolute ; According to Rüdiger Vaas and Scott Atran, for example, the reference to the transcendent represents the central difference to the non-religious.

Functionalist concepts of religion try to determine religion on the basis of its community-building social role. Often the definition takes place from the point of view of a certain religion, for example from the part of Christianity . One of the most famous and often cited definitions of religion comes from Friedrich Schleiermacher and reads: Religion is “the feeling of absolute dependence on God”. The definition from the point of view of a Jesuit is: "Worship of spiritual, outside and above the visible world standing personal beings, on whom one believes oneself to be dependent and which one tries to favor somehow".

A substantialist definition according to the Protestant theologian Gustav Mensching reads: "Religion is an experience-like encounter with the sacred and responsive action of the person determined by the sacred." According to the religious scholar Peter Antes , religion is understood to mean "all ideas, attitudes and actions towards that reality ], who accept and name people as powers or power, as spirits or demons, as gods or god, as the sacred or the absolute or, finally, only as transcendence. "

Michael Bergunder divides the term into religion 1 and religion 2. Religion 1 can be understood as the religious studies attempts at an exact definition of the term. Religion 2, on the other hand, describes the everyday understanding of religion. However, there are interactions between these two definitions, so that a clear distinction cannot be made. Bergunder historicizes the concept of religion and therefore criticizes it at the same time. So there is a difference in the understanding of religion on the meta-level (true philosophical) and in experience (anthropological).

Clifford Geertz and Gerd Theißen

Gerd Theißen defines religion based on Clifford Geertz (1966) as a system of cultural signs :

"Religion is a cultural sign system that promises gain in life through correspondence to an ultimate reality."

Theißen (2008) simplifies Geertz's definition by speaking of a system of signs instead of the " system of symbols". According to Geertz (1966) a religion is:

- a system of symbols that aims

- create strong, comprehensive and lasting moods and motivations in people,

- by formulating ideas of a general order of being and

- surrounds these ideas with such an aura of facticity that

- the moods and motivations seem to correspond completely to reality .

Geertz developed the theory of interpretive or symbolic anthropology in his writings ( density description ), he is considered a representative of a functional concept of religion, that is, he did not deal with the question of what the essence or substance of religion is (in the sense of a substantial concept of religion ), but what their function is for the individual and for society. For him religion was a necessary pattern of culture. Geertz saw in religion a system of meaning and orientation and ultimately a strategy for resolving conflicts, because religions provide a general order of being and a pattern of order and through them no event remains inexplicable.

Theißen justifies this with the fact that symbols in the narrower sense are only a particularly complex form of signs and Geertz's formulation of the description of the "correspondence of moods and motivations to a factually believed order of being" in an equally differentiated manner in the "correspondence to an ultimate reality" finds expression. Theissen's definition now allows the following analysis:

- cultural sign system, says something about the essence of religion;

- The sign system corresponds to an ultimate reality, says something about effect;

- Sign system promises gain in life, says something about function.

| Religion as an ordering force | Religion as crisis management | Religion as a crisis provocation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| cognitive | Building a cognitive order: placing people in the cosmos | Coping with cognitive crises: the irritation caused by borderline experiences | Provocation of cognitive crises: The intrusion of the whole other |

| emotionally | Build basic emotional trust in a legitimate order | Coping with emotional crises: fear , guilt , failure , grief | Provocation of emotional crises: through fear, guilt, etc. |

| pragmatic | Building accepted forms of life, their values and norms | Overcoming crises: repentance, atonement , renewal | Provocation of crises: through the pathos of the unconditional |

etymology

The word religio had various meanings in Latin , ranging from “concerns, doubts, anxiety, scruples of conscience” to “ conscientiousness , religiosity , fear of God , piety , worship ” to “ holiness (e.g. of a place)” and “ superstition ” . The etymology of the term cannot be traced back to its origin with certainty. Religio is not a term used in ancient Roman religion . The earliest evidence for the use of this expression can be found in the comedies of Plautus (approx. 250-184 BC) and in the political speeches of Cato (234-149 BC).

According to Cicero (1st century BC) religio goes back to relegere , which literally means “read again, pick up again, put together again”, in a figurative sense “consider, pay attention”. Cicero was thinking of the temple cult, which had to be carefully observed. He contrasted this religio (as the conscientious observance of traditional rules) with superstitio (according to the original meaning ecstasy ) as an exaggerated form of spirituality with days of prayer and sacrifice. In the sense of a “professional” worship of God, religious people were referred to as religiosi in the Middle Ages . The term has this meaning to this day in Roman Catholic canon law . When it was borrowed into German in the 16th century, religion was initially used in this sense, namely to denote official Church interpretation of the Bible and cult practice and how it was differentiated from so-called superstition (see superstition ). To this day, the Roman congregation for religious is called the " Religious Congregation ".

At the beginning of the 4th century, however, the Christian apologist Lactantius led the word religio back to religare " back- , to-, to tie" back, where he argued polemically with Cicero's view of the difference between religio and superstitio . He said it was a "bond of piety" that binds the believer to God. However, this origin is controversial among linguists, as there are no comparable words that come from a verb in the Latin a-conjugation in which the suffix -are has developed into -ion without any signs .

In the Middle Ages and in the early modern period , the expressions fides (“faith”), lex (“law”) and secta (from sequi “to follow”, ie “allegiance, direction, party”) were used to denote the totality of the religious . Religio initially referred to doctrines that were considered right or wrong depending on the view. It was only after the Reformation , especially in the Age of Enlightenment , that a more abstract concept of religion was coined, to which the current definition approaches go back.

In most of the non-European languages no exact translations of the word religion were found until the 19th century . The phenomenon has often been described in several terms. Own terms were coined relatively late. This applies, for example, to the term Hinduism , the meaning of which has also changed several times.

The scholar of religion and linguistics, Axel Bergmann, has recently proposed a different etymology. According to this, the word is not formed with the prefix re- (“back, again”), rather it goes to the old Latin rem ligere “to bind a thing (or a project)”, ie. H. "Look at it with (religious) scruples" and consequently "shy away in awe", back. According to Bergmann, this expression of everyday language was initially specifically related to religious scruples and later extended to the entire field of religion.

Universal elements of the religious

The Austrian ethnologist, cultural and social anthropologist Karl R. Wernhart has classified the basic structures of "religious beliefs per se" , which are common to all religions and cultures - regardless of their constant change - as follows:

Faith

- Existence of incorporeal, supernatural "force fields" (souls, ancestors, spirits, gods)

- Connection of the human being with the transcendent in a holistically intertwined relationship dimension that goes beyond normal human consciousness and is sanctified

- All ethics and morals are causally rooted in the respective world of belief

- Man is more than his purely physical existence (has a soul, for example)

orientation

Answers to the metaphysical " cardinal questions of life": (Italics = Wernhart quotes the "Declaration on the relationship of the Church to non-Christian religions" of the 2nd Vatican Council from 1962–1965)

- Where do we come from? ( What is man? What is the meaning and purpose of life ?)

- Creation myths - which are often transformed and kept alive with the help of drama, music, rites or dances - form a vehicle everywhere to record historical events in a timeless dimension. The myth is the way how the world explains legitimized and is evaluated.

- Where are we in the world? (What is the good, the bad, [...]? Where does the suffering come from and what is the point?)

- Where are we going? (What is the way to true happiness?)

- What is our ultimate goal? (What is that last and inexpressible secret of our existence [...]?)

Security aspect

Many scientists (e.g. A. Giddens , LA Kirkpatrick, A. Newberg and E. d'Aquili) particularly emphasize the aspect of safety for the individual or his neighbor when it comes to orientation. In their view, religions satisfy the need for support and stability in the face of existential fears; they offer comfort, protection and clarification in the face of suffering, disease, death, poverty, misery and injustice. According to Kirkpatrick's attachment theory , God is a substitute caregiver when human caregivers (parents, teachers, etc.) are missing or insufficient. This assumption could be supported empirically by RK Ullmann .

Boyer and Atran criticize the functions of security and orientation. They counter this by saying that religions often raise more questions than they answer, that the idea of salvation often does not occur, that despite the official religions, there is often a belief in evil spirits and witches and that even many denominations not only reduce fears, but also new ones create. In contrast to Wernhart, the two scientists reduce the universals to two human needs: cooperation and information.

Forms of expression

Every believer has expectations, hopes and longings which, against the background of faith and religious orientation, find their expression in various practices:

- Prayers to ask for or thank and for dialogue with the transcendent

- Cult acts ( rites , sacrifices , ceremonies, etc.)

- Asceticism , ecstasy , meditation , mysticism

Systematics of Religions

Since the beginning of religious studies, many attempts have been made to reconstruct the postulated historical relationships between the various belief systems and to create a typology and system from them. While this is quite easy with the world religions due to the written evidence, it has not yet been convincingly successful for the ethnic religions - or for all religions as a whole - by today's standards.

Religion as a historical phenomenon

Oldest traces

After older theories - such as that of a prehistoric bear cult or a uniform "primordial religion" (see for example: Animistic primordial religion , core shamanism according to Harner or primeval monotheism according to Wilhelm Schmidt ) - are now considered to be refuted, but on the other hand the long-doubted dating of Upper Palaeolithic cave paintings and musical instruments have been significantly expanded and have been confirmed, a scientific consensus has emerged on the beginning of human religious history . According to this, burials and (later) grave goods are recognized as early archaeological signs of religious expression, which began around 120,000 years BC. In the Middle Paleolithic in both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. In the late Middle Paleolithic (middle section of the Paleolithic) and early Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age), Homo sapiens developed more complex forms of expression in early small works of art, cave paintings, later with elaborate tombs and buildings that were prominent in the Middle East at the beginning of the Neolithic (New Stone Age), such as those interpreted as temples Gobekli Tepe .

From approx. 40,000 BC. BC - with the appearance of artistic sculptures, paintings and musical instruments - the references become clearer. It is unclear or speculative, however, which religious contents and concepts can be ascribed to these artefacts .

Historical religions

Many of the religions still practiced today have their roots in prehistoric times. Other early religions no longer exist today and their content is often difficult to grasp, as missing or incomplete tradition makes understanding difficult and religious concepts are only reflected indirectly in the material artefacts found by archeology. This leads to very different interpretations of the archaeological finds.

Even where there are very extensive written sources (e.g. the ancient religions of the Greeks and Romans), knowledge of cult practice and individual religious practice is still very sketchy. Often one has knowledge mainly of mythology , so one knows something about the mythology of the Celts and the Teutons , but hardly anything about cult practice.

The historical religions include (spatially and temporally ordered):

|

|

History of Concrete Religions

The history of various religions is presented in the history sections of their respective articles or in separate historical articles:

- African religions

- Bahaitum

- Buddhism

- Christianity

- Daoism

- Hinduism

- Islam

- Jainism

- Judaism

- Confucianism

- Sikhism

- Shinto

- Zoroastrianism

Religion in Modern Times

In contrast to the medieval Christian societies, in which almost the entire reality of life was under the authority of religion, institutionalized religion increasingly lost power in modern times . In place of theology , the natural sciences and humanities gained authority, for example in questions of evolution or ethics / law , areas that were previously subject to religion. The tendency towards a separation of church and state is called secularization . Attempts to explain this phenomenon often relate to the ideas of humanism and the Enlightenment , influences of industrialization , the gradual or revolutionary overcoming of the feudal corporate state and the associated economic, social , cultural and legal change. The change encompasses all social fields, including that of the constituted religion, which also became more differentiated, on the one hand showed the potential for violence and intolerance, on the other hand it appeared more pluralistic and often displayed more tolerance .

In Europe, Christianity began to lose importance in terms of its reputation, its social and political influence and its spread at an accelerated rate from the late 19th century. Some traditionally Christian western countries recorded a decline in the number of clergymen , downsizing of the monasteries and an increase in the number of people leaving the Church or other forms of distancing.

The social influence of the Catholic Church declined particularly in France, where strict secularism was implemented through the Revolution of 1789, the Civil Code 1804 and the law separating church and state at the beginning of the 20th century .

The decreasing material and spiritual power of the large Christian churches, which Friedrich Nietzsche commented on at the end of the 19th century with the words “ God is dead ”, was and is criticized by some religious thinkers. They argue that the waning influence of religion will reduce ethical standards and make man the measure of all things . Under the motto "Without God everything is allowed", destructive actions and nihilistic thinking could be encouraged. However, there is no clear evidence of such consequences.

In the Soviet Union , especially during Stalin's reign of terror , in National Socialist Germany and, to a lesser extent, in the Eastern Bloc states after 1945, public religious activity could lead to societal disadvantages, including death sentences and deportation. Therefore, the proportion of visibly practicing members of religious communities there was comparatively low. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, an ambivalent development can be observed. While organized religion continues to play only a marginal role in the new federal states , it is deeply rooted in Poland, for example . In many other regions of the world, such as the Islamic and Asian regions, there was and is massive discrimination based on religious affiliation. See for example the World Persecution Index on this and especially on the persecution of Christians .

Current trends

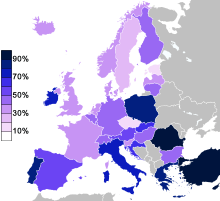

Numerous studies show declining visitor numbers in churches, synagogues and other religious institutions, e.g. B. in Great Britain, Germany and France, although according to surveys the churches are still recognized as public institutions. In most European countries, however, more than 50% of the population were members of a Christian church in 2005. In Poland , Ireland , Spain and Italy , the Catholic Church, to which more than 80% of the residents belong, is considered to be politically influential. In many European countries it is still customary, at least formally, to belong to a religious community. For a few decades, and increasingly since the end of the last millennium, young people in particular have increasingly turned to institutionalized or other forms of religious expression.

In contrast to secularization in Europe, Islam and Christianity in particular, but also Buddhism, are gaining in importance in the rest of the world. In the United States and Latin America, for example, religion continues to be an important factor. In the 20th century, the influence of Christianity and Islam in Africa grew considerably. In the Arab world , Islam is still the defining element of society. Islam has also gained influence in parts of Asia, such as Indonesia , Pakistan , India and Bangladesh . In the People's Republic of China, religious communities have experienced a moderate upswing again since the respective bans were relaxed. Of the Christian churches and religious communities, the evangelical missionaries who belong to Protestantism achieve the greatest number of “ conversion successes ” worldwide .

However, this does not mean that the largest number of people who profess a religious community also actively practice their faith. Wherever religion contributes to the formation of national or political identity, such as Catholicism in Poland or Orthodoxy in Russia , or where it offers potential for identification with a political thrust against Western invaders, for social justice or for ethnic demarcation, it is popular without it this must be connected with the renewed strength of traditionally lived piety. On the contrary, precisely where traditionally lived religiosity is declining, the politicized religion gains strength. This applies not only to evangelicalism in North and South America or fundamentalist Islam, but also to Buddhism (e.g. in Sri Lanka or Myanmar ) or the Hindu nationalism in India . The polarization between indifference to religion and the trend towards fundamentalism could be related to the rationalization and a declining tolerance of ambiguity in the modern world, since an acceptance of transcendence requires the recognition of uncertain or contradicting views, unless the transcendence occurs in a fundamentalist, unambiguous way suggestive expression. Islam is a sign of a decreasing tolerance for ambiguity in the transmission and interpretation of holy scriptures. While several versions of the Koran were read and commented on until the end of the 19th century, and several interpretations were allowed, today's commentators are mostly convinced that there was only one interpretation. The Islamic scholar Thomas Bauer attributes this development to the confrontation of Islam with the West. Other associated trends are religious indifference as a strategy to avoid ambiguity and the increasing arbitrariness or randomness of the choice of a “private religion”, sometimes in a secularized form (e.g. diet as a substitute religion, which can of course be dogmatized).

Recent research indicates that there is a statistically verifiable connection between demographics and religion in contemporary societies . The number of children in religious communities is sometimes considerably higher than in more secular societies. Examples of this are the birth rates of families of Turkish origin in Germany, most of whom belong to Sunni Islam , of evangelical Christian groups in the USA and increasingly also in Europe, and members of Orthodox Judaism in Israel . This phenomenon is currently assessed not only positively but also negatively against the background of the problems of a growing world population.

In most of the member states of the United Nations , the right to religious freedom has now been enshrined in law, but not necessarily implemented in everyday life. However, there are still numerous countries in which there is no right of free choice of religion. B. Saudi Arabia and North Korea , or in which the freedom of action of religious individuals and groups is limited. In contrast, the USA grants practically every community that describes itself as religious, the status of a religious community with corresponding rights.

Since the increasing recognition of indigenous peoples, there has been a revitalization of ethnic religions (for example among the Tuvinians in China and Russia, among many Indians in North America or among the Sami of Scandinavia). However, due to the knowledge that has already been lost in many cases, the long-term influences of other religions or the reference to (sometimes incorrect) interpretations of Western authors from science and esotericism, these forms of religion cannot in most cases be equated with their traditional predecessors.

Religions in numbers

The sources for precise statements about religious affiliation worldwide are extremely questionable. Not only do the research methods differ significantly, but above all the starting situation in the states is very different. Relatively exact statements can only be made about states in which there is freedom of religion . But there is also a high degree of variance there , especially in terms of data collection. Different results are to be expected, for example, depending on whether the statements are based on officially recorded membership of a religious community or on surveys. Regimes that do not guarantee religious freedom or states that officially consider themselves atheist make a realistic picture almost impossible. In addition, the world religions are also very heterogeneous: for example, Christianity in African countries differs from that in Scandinavian countries in many ways. Non-religious Jews are mostly counted as Judaism, all church taxpayers in Germany, even if they are not religious, and all citizens of Saudi Arabia are counted as Islam. Blurs arise u. a. also because children and young people are assigned to the religion of their parents, but do not necessarily feel that they belong to this religion themselves. More precise information can be given for individual states with designated statistical systems, but these cannot be easily compared with one another.

| Religion / belief | Relatives in millions according to adherents.com, approx. 2006 | Relatives in millions according to Britannica Online, approx. 2006 |

|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 2100 | 2200 |

| Islam | 1500 | 1387 |

| Secular , non-religious | 1100 | 776 |

| Hinduism | 900 | 876 |

| Traditional Chinese Religions | 394 | 386 |

| Buddhism | 376 | 386 |

| Ethnic religions | (266) | |

| Non-African Ethnic Religions | 300 | |

| Traditional African religions | 100 | |

| New Religious Movement | 107 | |

| Sikhism | 23 | 23 |

| spiritism | 15th | 14th |

| Judaism | 14th | 15th |

| Bahaitum | 7th | 8th |

| Confucianism | 6th | |

| Jainism | 4th | 5 |

| Shinto | 4th | 3 |

| Caodaism | 4th | |

| Zoroastrianism | 2.6 | 0.2 |

| Tenrikyō | 2 | |

| Neopaganism | 1 | |

|

Universalism / Unitarianism (there are both Christian and now non-Christian universalists / Unitarians) |

0.8 | |

| Rastafarian | 0.6 | |

| Other religions | 1.2 |

For distribution in Germany, Austria and Switzerland see also Religions in Germany , Recognized Religions in Austria and Religions in Switzerland

| religion | Relatives in Germany in millions (2014) |

|---|---|

| Non-religious | 26 (32%) |

| Roman Catholic Church | 24.2 (30%) |

| Evangelical regional churches | 23.4 (29%) |

| Islam | 4 (5%) |

| Orthodox Church | 1.5 (1.9%) |

| New Apostolic Church | 0.35 |

| Buddhism | 0.3 |

| Judaism | 0.2 |

| Jehovah's Witness | 0.17 |

| Hinduism | 0.1 |

According to a representative survey by the Eurobarometer , 52% of people in the then European Union believed in God in 2005 , and another 27% believed somewhat more vaguely in a spiritual force or higher power. 18% percent of those questioned believed neither in a God nor in any other spiritual force, 3% of EU citizens were undecided.

According to the 15th Shell Youth Study from 2006, 30% of the German young people surveyed between the ages of 12 and 24 believe in a personal God, another 19% in a higher power, while 23% gave more agnostic statements and 28% did not believe a god yet a higher power.

Scientific approaches to defining and describing religion

Even when trying to find a scientific approach to the term “religion”, the sciences are faced with great difficulties: How can one find a supra-historical definition of religion that encompasses all religions and that can be used scientifically? Often the definitions are either too narrow, so that important religious trends are not included; or the term “religion” loses its precision and becomes too arbitrary for comparable investigations to be permitted. It turns out to be difficult to deal scientifically with an object of investigation, the definition of which does not allow a clear delimitation.

Nevertheless, religion is "a social reality, a specific communication process that creates realities and itself takes on real shape through social actions" and therefore necessarily the subject of scientific curiosity. The concepts presented in the following should always be perceived against the background of the difficulties in finding terms that contrast with the scientific necessity to deal with the real phenomenon of "religion".

Philosophical and psychological approaches

The pioneer of the Enlightenment Jean-Jacques Rousseau criticized religion as a source of war and abuse of power in his influential work " On the Social Contract or Principles of State Law " , published in Paris in 1762 , but noted people's religious feelings. He developed the model of a civil religion that would meet the political requirements of a "free" enlightened society. This included the recognition of the existence of God , an afterlife , the retribution of justice and injustice, the inviolability (holiness) of the social contract and the laws and finally tolerance . This new civil religion, equally valid for all citizens, should contribute to the stability of the community.

His also enlightened opponent Voltaire , who rejected the dogmas and the power of the Catholic Church even more sharply, advocated a reason-led, tolerant deism independent of the religions that existed until then and emphasized the moral usefulness of belief in God. He was convinced of the regularity of the cosmos and the existence of a supreme intelligence, assumed the immortality of the soul and a free human will, positions which he also doubted in every respect. He did not share a belief in scriptures or in Jesus Christ as the Son of God.

In 1793, Immanuel Kant formulated his conception of a religion of reason in his religious-philosophical work “ The Religion Within the Limits of Mere Reason ” . He developed a philosophical doctrine of religion that postulates the principle of evil . Evil is inherent in the human being. He assumes the existence of God and the immortality of the soul. However, God cannot be proven . According to Kant, only Christianity, in contrast to other, in his view “outdated” and “ritualized” religions such as Judaism and Islam , has a doctrine and morality that philosophy can recognize. Consistent moral action is therefore not possible without belief in freedom , the immortality of the soul and God. Hence morality is the original. Religion, however, declares moral duties to be divine commandments. So religion follows the pre-existing moral law. In order to find the actual human duties, one must filter out the right thing from the various religious teachings. Kant rejected ritual practices of the religions as "clergy". Epistemologically , he took an agnostic attitude.

In 1841, the religion critic Ludwig Feuerbach declared religion to be “the first, and indeed indirect, self-confidence of people. [...] man objectifies his own secret being in religion. ”Accordingly, the religious man regards everything that he considers to be true, right and good as independent appearances outside of himself. These independent appearances can be seen by man as a singular person or present plural with limited or unlimited sphere of activity and consequently name his concepts of true, right and good as divine gods or the only god or without personification as forces, powers, effects, legal processes or similar. How he does this depends on regional development and tradition. Logically, Feuerbach no longer regards religion as a world-defining, humane system, but as an ethnological research area.

Karl Marx described in 1844, following Feuerbach in his Introduction to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right religion as "the opium of the people ", a phrase which the dictum has become. A central idea for Marx is that creatures rule their creators: "As man is ruled by the work of his own head in religion, so in capitalist production he is dominated by the work of his own hand."

From Feuerbach's demand that people “give up the illusion about their condition”, Marx draws the conclusion “to give up a condition that needs illusions”. According to Marx, religion is produced by the state and society as an inverted world consciousness because in previous social systems man was alienated from himself . "The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people" is for him therefore "the requirement of his real happiness".

Of Friedrich Nietzsche the idea as originating Modern repeatedly quoted saying "God is dead!" He goes on, and this is less well known: "God is dead! And we killed him! How do we console ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? ”The philosopher counted the growing importance of the natural sciences and the science of history, together with the radical criticism of religion, among the causes for the decline in (Christian) morality.

Standing in the tradition of Feuerbach and Nietzsche, the founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud presented religion as an obsessional neurosis and infantile defensive behavior. Primitive man personalized the forces of nature and elevated them to protective powers so that they could support him in his helplessness. The underlying behavior pattern is linked to the early childhood experience of the protective, but also punitive, father. This results in an ambivalent relationship with the father, which leads to "faith" in adulthood. Man fear the gods and at the same time seek their protection. Referring to Charles Darwin's theory of evolution , Freud saw the “primal horde” with a despotic “tribal father” as leader who could dispose of all women of the tribe. His sons adored him, but also feared him. Out of jealousy, they killed their forefather together. The “ Oedipus Complex ” emerged from this. The guilt consciousness of the whole of humanity (conception of the " original sin ") is thus the beginning of social organization, religion and - related to this - sexual restriction.

The Argentine religious psychologist Ana-Maria Rizzuto assumes - unlike Freud - that the concept of God is a necessary part of the formation of the ego . Accordingly, children develop their respective image of God from the wide range of fantasies about heroes and magical beings - within the framework of the reference system of their parents and the environment.

Erich Fromm coined a broad, socio-psychological definition. As a religion, he considered any system of thought and action shared by a group that offered the individual a framework of orientation and an object of devotion.

The contemporary postmodern German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk attributes the effect of a psycho- semantic immune system to religion . In the course of cultural development, people have become more open, but also more vulnerable. Religion enables people to heal "injuries, invasions and offenses" themselves. Sloterdijk does not call God, but “the knowledge of healing as a reality, from the biological to a spiritual level” as the pearl in the shell of theology .

Jürgen Habermas , the most prominent representative of critical theory in the present, has been emphasizing the positive influence of (Christian) religion on democratic value systems since the late 1990s, while Theodor W. Adorno, in the Marxian tradition, understands religion as a "social projection" and Durkheim's Sociology of religion pointedly summarized in the statement that “in religion society adores itself”.

Theories of the history of religion

The primary question in the history of religion is: “Is the development of religion subject to a direct socio-cultural evolution or is it just a by-product of other cognitive developments?” An evolutionary process always requires selective factors , so that the question can only be answered if unequivocal factors can be determined that give believers some survival advantage.

In the early days of the scientific treatment of religion, evolutionist designs were predominant, in which the individual events were seen as mere stages of comparatively simple, global, quasi-natural law developments, for example with James Frazer as a development from magic through religion to science . These teleological positions often suffered from inadequate empirical foundations , mostly contained explicit or implicit evaluations and were often not applicable to the individual case of concrete religious-historical events. In modern religious studies they only play a role as suppliers of material and as part of the specialist history.

In a historical-philosophical consideration, Karl Jaspers made what he called an Axial Age between 800 and 200 BC. In which essential innovations in intellectual history shaped the philosophical and religious history of China , India , Iran and Greece . Jaspers interpreted this as a comprehensive epoch of the “spiritualization” of man, which had an impact in philosophy and religion, and secondarily in law and technology. With this pluralistic interpretation Jaspers turned against a Christian motivated conception of a universal story . In contrast to the revealed religions, which he rejected, he conceived in his religious-philosophical work The Philosophical Faith in the Face of Revelation a philosophical approach to a transcendence in the face of human ideas of omnipotence.

The religious-spiritual notions of non-written cultures , often referred to as “natural religions” , scientifically more correct than ethnic religions or (outdated) as animism , have long been regarded as the oldest forms of religion because of their alleged “primitiveness”. But they are also subject to historical change and are therefore no longer understood by some authors in the sense of unchanged traditions . Due to the lack of dogmas and their great ability to adapt to changed conditions, on the contrary, they are all younger than the known high religions . Nevertheless, a number of prehistorians (such as Marcel Otte ) hold on to the idea that the religions of the past can be reconstructed by comparing them with today's “primitive religions”. It ignores the fact that these belief systems must have had a beginning at some point that must be thought in a much simpler way than the complex worldviews of today's indigenous people.

In general, a direct evolution of religions in close connection with the change in social structures is postulated today, because it obviously has a positive influence on certain aspects of living together. However, there is still disagreement about the specific selection advantages. Neither the promotion of altruistic behavior nor a concrete influence on the reproduction rate has been proven beyond doubt. The religious scholar Ina Wunn also criticizes the fact that many models still require a higher level of development, thus degrading ethnic or polytheistic religions. This would justify reprisals by certain states against their religious minorities in the interests of progress.

In recent times, the history of religion as a universal history has taken a back seat to the study of the history of individual religions or cultural areas. However, theories relating to the history of religion, such as secularization and pluralization, are being given increasing attention again.

Religious sociological approaches

Religious sociological thought processes can already be found in ancient Greece , especially in Xenophanes ( If the horses had gods, they would look like horses ).

According to Ferdinand Tönnies (1887), one of the co-founders of sociology , religion in the “ community ” is the equivalent of “ public opinion ” in “society”. Tönnies understands this demarcation as normal . Religion and public opinion are the respective mental training of the community or society (in addition to the political and economic). Since people in the community see themselves as a “means to the end of higher collectives”, they are capable of great sacrifices in favor of an assumed higher authority - unlike “socially” connected people who see all collectives as means for their individual ends, and utilitarian support or combat the respective society . According to Tönnies, religion and public opinion have strong similarities, such as severe intolerance towards dissenters.

According to Émile Durkheim (1912), another co-founder of sociology, religion contributes to the consolidation of social structures , but also to the stabilization of the individual . His concept of religion is therefore a functionalist one . According to Durkheim, religion is a system of solidarity that refers to beliefs and practices that encompass things considered sacred and that binds all members together in a moral community such as the church. This gives rise to three aspects of religion, the beliefs ( myths ), the practices ( rites ) and the community to which these beliefs and practices are related. Durkheim describes belief as an element of the power society wields over its members, among other factors. One of the notable aspects of his concept of religion is the distinction between the sacred and the profane , which allows religion to be defined without reference to God, gods or supernatural beings ( deities ). It is also used outside of sociology and is also based on the term "secular religion" (in Max Weber: "this- worldly religion"), which is used to describe world views that include worldly phenomena such as B. make the state, a party or a political leader the object of religious-like veneration.

Max Weber , who at the beginning of the 20th century dealt extensively with the phenomenon “religion” from a sociological point of view, differentiates between religion and magic . He understands “religion” to be a permanent, ethically founded system with full-time functionaries who represent a regulated teaching, lead an organized community and strive for social influence. According to Weber, “magic”, on the other hand, is only effective in the short term, tied to individual magicians or magicians who, as charismatic personalities, supposedly conquer the forces of nature and develop their own moral ideas. Weber sees this demarcation as ideal . Pure forms are rare, overlaps and transitions are noted. Weber worked out extensive theoretical treatises on the various religions, in particular on Protestant ethics, and conducted empirical studies on the different economic developments in Protestant and Catholic countries.

In the second half of the 20th century, Niklas Luhmann differentiates between “system” and “environment” in his system theory . The environment therefore offers opportunities that can be used by the system through exclusion and selection. This selection process limits the complexity of the environment. However, since both the system and the environment are still characterized by a high level of complexity, simplifications are necessary for orientation. As a social functional system of modern societies, among others, religion has such an orienting function. It limits an excess of possibilities and prevents any change in the selection.

The theory of the rational decision of religions emerged in the 1980s. The main representatives are Rodney Stark , Laurence R. Iannaccone and Roger Finke . This theory says that actors choose their actions in a utility-oriented manner. Assumptions of this theory are: the actor acts rationally by weighing costs and benefits; there are stable preferences that do not differ greatly from actor to actor or over time; social events are the result of social interactions between actors. According to this theory, not only the actor in the form of the believer acts in a utility-maximizing manner, but also religious organizations. They specialize their offering of religious goods so that they attract as many believers as possible. This theory is criticized by various other sociologists of religion because, for example, central terms of the theory are not precisely defined (“costs”, “benefits”), and it is disputed whether cost-theoretical concepts from business administration can be transferred to religious action.

Religious Studies Approaches

The religious studies , a variety of disciplines such as sociology of religion , philosophy of religion , religion philology , history of religion u. a. includes, investigates on an empirical and theoretical basis religions as social phenomena. Theories of religious studies must be understandable and falsifiable regardless of beliefs . Established as an independent discipline for about 100 years , it goes back to forerunners both within Europe and beyond (comparative religious studies in China and the Islamic world). In contrast to theology , religious studies include, on the one hand, the possibility of dialogue , but also the option of criticizing religion .

According to Clifford Geertz (1973), religion is a culturally-created system of symbols that tries to create lasting moods and motivations in people by formulating a general order of being. These created ideas are surrounded with a convincing effect (“aura of facticity”) that these moods and motivations appear real. Such “holy” symbol systems have the function of connecting the ethos - that is, the moral self-confidence of a culture - with the image that this culture has of reality with its notions of order. The idea of the world becomes an image of the actual conditions of a form of life . The religious symbol systems create a correspondence between a certain lifestyle and a certain metaphysics that support one another. Religion adjusts human actions to an imagined cosmic order. The ethical and aesthetic preferences of the culture are thereby objectified and appear as a necessity that is generated by a certain structure of the world. Accordingly, the beliefs of the religions are not restricted to their metaphysical contexts, but rather generate systems of general ideas with which intellectual, emotional or moral experiences can be meaningfully expressed. Since the symbol system and cultural process can be transferred, religions not only offer models for explaining the world, but also shape social and psychological processes. The different religions generate a variety of different moods and motivations, so that it is not possible to determine the importance of religion in ethical or functional terms.

According to Rüdiger Vaas, religions offer the "ultimate relatedness": the feeling of connectedness, dependence, obligation as well as the belief in meaning and purpose.

Jacques Waardenburg describes the definition of religion as 'belief' as a product of Western tradition. This term therefore does not apply to the ideas of other cultures and is rather unsuitable for describing religions. In his opinion, religions can be viewed as a structure of meaning with underlying basic intentions for people.

A common approach to the concept of religion in religious studies is to regard religion as an “open concept”, that is, to completely dispense with a definition of the concept of religion. This view was particularly represented by the Bremen religious scholar Hans G. Kippenberg .

Michael Bergunder took a cultural-scientific approach. Bergunder looks at the historical change in terminology and finds that religion was Eurocentric for a long time . The “common understanding of everyday life” to which religious studies refers must, however, today be based on a global concept of religion.

Other religious scholars developed the model of the various "dimensions" of religion. Above all, Rodney Stark and Charles Glock should be mentioned here. They differentiate between the ideological , the ritualized and the intellectual dimension, as well as the experience dimension and the practical dimension. The Irish-British religious scholar Ninian Smart took a similar approach : he also designed a multidimensional model of religion and distinguishes between seven dimensions: 1. the practical and ritual, 2. the experiential and emotional, 3. the narrative or mythical, 4. the doctrinal and philosophical, 5. the ethical and legal, 6. the social and institutional and 7. the material dimension (e.g. sacred buildings).

Recently, a dialogue has developed between some neuroscientists and religious scholars as well as theologians, which is sometimes referred to as neurotheology and which is increasingly intertwined with biologists' search for a conclusive theory on the evolution of religions.

Scientific approaches

Various neuroscientists have been searching for neurological explanations for different types of religious experiences since 1970 . Corresponding studies have been published by David M. Wulff, Eugene d'Aquili, C. Daniel Batson, Patricia Schoenrade, W. Larry Ventis, Michael A. Persinger, K. Dewhurst, AW Beard, James J. Austin and Andrew Newberg .

Evolutionary researchers such as the biologist Richard Dawkins and the psychologist Susan Blackmore proposed the theory of memes and tried to capture the phenomenon of religion. In 1991 Dawkins describes a religion as a group of ideas and thought patterns that reinforce one another and work together to spread them ( Memplex ). This classification is based on the observation that religions can successfully propagate actions and beliefs that seem senseless outside of their religious context or that are contrary to objective reality. According to Dawkins, a prerequisite for the dissemination of religious thoughts is the willingness to literally pass on beliefs and to follow the instructions coded in them. He compares these processes with the mechanisms by which viruses stimulate an infected organism to spread their own genetic material. In analogy to computer viruses, he also speaks of "viruses of the mind".

Many evolutionary biologists agree that religion has proven beneficial for community building in the course of evolution. Jointly erected stone circles such as that of Göbekli Tepe , which probably served the cult of the dead and whose stone blocks weigh up to 20 tons, go back to the 10th millennium BC. BC back, d. H. to the pre- Neolithic era. Religion was therefore not a “luxury product of sedentary people”, but motivated to act together and was therefore more of a prerequisite for sedentarism.

Some authors draw from the in different cultures observed notions of supernatural actors and empirical conclusions about underlying processing processes in the human brain . According to a hypothesis derived from ethnological studies, z. B. Pascal Boyer that the brain processes sensory impressions with the help of various modules . One of these modules is specialized in inferring the presence of living beings from changes in the environment. Such a "living being recognition module" should work over-sensitive, since it is usually more useful for survival, z. B. to mistakenly interpret a breath of wind as a predator, as to overlook an actually existing one. As a result, vague perceptions could easily give rise to images of supernatural actors, such as ghosts or gods.

The research on free will and the assumption of an absolute determination of the human mind also have an influence on the attempts to explain religious ideas and practices.

Religious psychology in particular deals with the question of whether there is a general correlation between religion and health or lifespan of an individual. Research in the USA mostly supports this thesis, while European studies often fail to find such a link.

The American studies by Newberg and d'Aquili show, for example, that religious people are healthier and happier, live longer and recover more quickly from illnesses and operations. As a possible cause, they indicate the security and thus stress-reducing effect of religion, as well as the ability to find one's way in a terrifying world. B. Clark and R. Lelkes also cite greater life satisfaction, which would arise from a lower tendency to aggression and higher social skills.

Phenomena and religion-specific terminology

Various criteria and terms for describing religious phenomena are available. However, many of them are themselves products of religious perspectives and therefore of controversial value for describing religious phenomena on a scientific basis. For example, “ syncretism ” describes the mixing of religious ideas, but originally also denotes the overlooked logical contradictions and has been used as a battle term. Nevertheless, they are (especially in religious phenomenology ) valuable for comparative purposes.

Natural religion

In the Age of Enlightenment , ideas about natural religion (or natural theology ), which was seen as the origin of historical, flawed religions, go back to the philosophers of ancient Greece, Plato and Aristotle . In contrast, u. a. Friedrich Schleiermacher the thesis that these are abstractions of existing religions. This view has prevailed in modern religious studies.

Religion and belief

Especially in Christian-Protestant theology in the 20th century, according to Karl Barth , belief is often differentiated from religion. Barth saw religion as an unauthorized way of man to God and emphasized that knowledge of God's will only exists in faith in Jesus Christ . Listening to the gospel breaks all human concepts of God, all ethical wrong turns.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer adopted the distinction and radicalized it in his question of Christianity without religion , but distinguished himself from Barth's “revelatory positivism”. Gerhard Ebeling also emphasized the critical power of belief against religious determinations and certainties, but saw religion as a condition of life for belief.

Theism and atheism

The wide range of theism includes deism , polytheism , pantheism or pandeism and panentheism or panendeism; at the same time, overlaps and delimitations to agnosticism and atheism are described.

Religions, the majority of which believe in their own obligation to worship only one supreme God, are called monotheistic . This does not necessarily mean an assumption of the non-existence of other gods, but possibly also a value judgment, a distinction between the one true God and the various false gods ( see also: Shirk in Islam).

Those who assume the existence of several gods and give them a meaning for or an influence on their lives are called polytheistic.

Concepts according to which the divine or God is identical with the totality of the world (the universe) (and usually not personal) are called pantheistic.

For some researchers, e.g. B. Ray Billington , religions such as Buddhism, whose traditional ideas and rites are essentially not geared towards one or more gods, are in a certain sense atheistic. Jainism and Buddhism are cited as examples. Most, however, refuse to apply this term to worldviews in which the question of God does not play a role.

cosmology

Religions often convey an idea of how the world came into being (a story of creation or cosmogony ) and a picture of the last things, an eschatology .

This also includes answers to the question of what happens to people after death. (See also: soul .) Many religions postulate an existence after death and make statements about the future of the world. Topics such as reincarnation , nirvana , eternity , afterlife , heaven or hell , and what will happen to the world ( end of the world , apocalypse , Ragnarök , kingdom of God ) are central in many religions.

Religious specialists

Most religions know groups of people who deliver the religion, teach it, carry out its rituals and mediate between man and deity. Examples are seers or prophets , priests , pastors , preachers , clergy , monks , nuns , magicians , druids , medicine men or shamans . Some religions attribute supernatural qualities to some of these people.

The status of these people varies widely. They can be active within a formal organization or they can be independent, paid or unpaid, can be legitimized in various ways and be subject to a wide variety of codes of conduct .

In some religions, the religious rituals are performed or directed by the head of the family. There are also religions without a specifically authorized intermediary between the supernatural and man.

Spirituality, Piety and Rituals

Often religions and denominations maintain their own kind of spirituality . Spirituality - originally a Christian term - describes the spiritual experience and the conscious reference to the respective belief in contrast to dogmatics , which is the fixed teaching of a religion. In today's western usage, spirituality is often viewed as a spiritual search for God or some other transcendent reference, whether within the framework of specific religions or beyond. The term piety is often used synonymously, but it is used more in the church context today and also often has a negative connotation in the sense of an exaggerated, unconditional turn to religion. In some religions there are currents whose followers find the encounter with transcendence or the divine in mystical experiences .

Religious rites in the broader sense include prayer , meditation , baptism , worship , religious ecstasy , sacrifice , liturgy , processions, and pilgrimages . In addition, this also includes piety practiced in everyday life such as giving alms , mercy or asceticism .

Some atheistic-secular worldviews also make use of seemingly religious rituals. Examples are the elaborately staged marches and celebrations in socialist or fascist states as well as the (an) leader cults practiced in them at least for a time . The thesis that apparently non-religious systems use religious forms is being scientifically discussed ( see also: Political religion , civil religion , state religion or Religio Athletae ).

Schisms and Syncretisms

In the history of religions there have been many schisms (divisions) and the formation of sects . As a rule, new religions arise from the separation of a group from an older religious community.

The term syncretism describes the mixing of practices of different religions. This can be an attempt to (re) unite similar religions or to initiate the creation of a new religion from different predecessors.

Religion and religiosity

In German in particular, a distinction is made between "religion (s)" and "religiosity". While a religion refers to religious doctrine (→ dogma ) and the associated institution , religiosity refers to the subjective religious life, feelings (reverence for the “big picture”, transcendent explanation of the world) and desires ( enlightenment , religious affiliation) of the individual. For Johann Gottfried Herder , religiosity was the expression for a genuine religious feeling. In the Christian context, religiosity is often equated with belief.

In the history of German religion, Romanticism and Pietism in particular emphasized the inner attitude of the believer. The Protestant theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher, for example, wrote in his work Über die Religion (1799): "Religion is not metaphysics and morality, but looking and feeling."

The emphasis on feeling is also characteristic of the conception of religion presented more than 100 years later by the North American philosopher and psychologist William James : In his work The varieties of religious experience (1902) the pragmatist avoids a general definition of the term religion. According to James, religious truth is not something superordinate, withdrawn from humans. Rather, it manifests itself in the experience of the religious person and is experienced through the religious feeling that is formed through connection with a religious object. Due to the different feelings, which range from the certainty of the transcendental meaning of words and perceptions to the mystical feeling of connection with the cosmos, different forms of religiosity can be described. The deep religious experience transcends simple moral concepts. For James epistemological questions and those of methodology are secondary. He bases his work solely on descriptions and systematization of religious feelings.

James' work was significant for the development of early religious studies in the early 20th century. While Ernst Troeltsch tried to make James 'descriptions useful for his theory, James' approach was heavily criticized by religious psychologists such as Wilhelm Wundt and Karl Girgensohn .

The Protestant theologian and religious philosopher Rudolf Otto assumes in his main work Das Heilige , published in 1917 , that there is a special system (sensus numinis) for religious feeling. If a person has this disposition only weakly or not at all, he is hardly suitable as a religious believer. The religious feeling is to be differentiated from other feelings, nevertheless it is possible to draw parallels to the experience of other feelings (e.g. aesthetic feelings). Otto names four moments that are typical for experiencing religious feelings: The tremendum = the terrifying, the majesty = the overwhelming, the energetic = the strength, the will, the mystery = the “completely different”; see also Mysterium tremendum . These moments run through the entire history of religion. Furthermore, he assumes that religious experience, which is initially experienced affectively (“irrational”), is never “understood”, but is “ moralized ” through cognitive processes (“rationalization”) .

Rudolf Otto's emotional concept of the sacred also sparked a lively discussion at the time. While the religious scholar Gustav Mensching was inspired by Otto in his idea of tolerance of religions, Otto's theory was rejected as parapsychological by Wundt's student Willy Hellpach . Today Otto plays practically no role in religious studies. But ideas of numinous are still u. a. due to the depth psychological concepts of Erik H. Erikson and CG Jung taken in alternative directions of psychology (e.g. transpersonal psychology ).

Since the Enlightenment - especially in western cultures - a distinction has been made between institutionalized religion and a personal attitude towards the transcendent. In this way, the individual development of the religiosity of the individual is favored. In addition, there are increasingly forms of religion that have little effect on the lifestyle of the followers because they only use religious 'services' on certain occasions. This also includes approaches according to which groups or individuals have ideas, rituals, etc. from religions and other world views, etc. a. esoteric , reassemble and tailor to your needs. This eclectic approach is sometimes called "patchwork religion" or "supermarket of world views" by representatives of traditional religions.

Religion and ethics

Numerous ancient religions claimed to regulate human coexistence through laws. Most of today's religions have an ethical value system that they demand to be observed.

This system of values encompasses views of what is right and wrong and what is good and bad, how to act like a member of the respective religion and, in part, how to think. This is mostly based on a certain conception of the world, nature and the position of man. Although these beliefs change historically, there are similar ethical principles behind such religious duties in almost all religions. These are intended to regulate the low- conflict coexistence of the members of the religious community, to influence society and in part politics in the interests of religion and to bring people closer to the respective religious goal. In addition, they offer the individual a moral framework that can stabilize him mentally and physically, encourage individual and collective willingness to help or even contribute to social improvements.

All world religions and most minor religions demand mercy from their members. So in Islam z. B. stipulates that everyone should donate a fixed portion of their income for social purposes ( zakat ). In the Christian Middle Ages, the Roman Catholic Church founded universities and schools, maintained hospitals and orphanages and provided food for the poor . One aspect of religion can be peace-building , which in most religions is expressed through special regulations on compassion , forgiveness or even love of one's enemies .

In some religions, according to the respective tradition, these moral laws are said to have been brought directly to the founder of the religion by the corresponding deity and thus to have the highest authority ( revelation religions ). According to this idea, secular rulers should also bow to the respective ethical requirements. Obedience is demanded under threat of punishment in this world or in the other, or is presented as the only way to salvation . Even apostasy can ever be punished for interpretation of the religion.

Often there are other rules that do not come directly from the founder of the religion, but are derived from the holy scriptures and other traditions of the respective religion (e.g. Talmud , Councils , Sunna ). Some of these norms lost their meaning for many believers in the course of historical development and in some cases were adapted to the very different value systems of the corresponding time. (See Reform Judaism .)

As in all worldviews, there is also a contradiction in religions between theoretical claims and practical implementation. While the abuse of power and other grievances in the Middle Ages and early modern times often led to schisms and religious renewal movements, they currently often lead to a turning away from religion as a whole. In parallel to reform efforts, however, there are also fundamentalist religious interpretations and practices that extend to terrorist activities with pseudo- religious justification.

The strongest form of failure of ethical religious norms is religious wars and other acts of violence based on religious beliefs. Believers mostly see this as an abuse of their religion, while critics of religion assume a tendency towards fanaticism and cruelty inherent in all religions . It is also controversial whether these events are a necessary consequence of religions.

The Roman Catholic Church was responsible for the Inquisition . Crimes in the name of the Christian religion were the crusades , the persecution of witches , the persecution of Jews , violent forms of proselytizing or religiously disguised, actually political atrocities, such as the killing of numerous so-called Indians, members of indigenous peoples of South America during the conquest and in modern times, in part, the support of Dictatorships and the Ambivalent Role of the Churches in the Time of National Socialism . However, at all of these events there were always critics from within our own ranks. The church and religion critic Karlheinz Deschner has evaluated and commented on a wealth of historical material on this topic in his ten-volume work Kriminalgeschichte des Christianentums from 1986 onwards.

Even in recent years violence are partially linked to religion: Thus, since the establishment of a theocracy , the Islamic Republic of Iran , thousands of people for so-called "crimes against religion" in an appeal system based on a specific interpretation of Sharia based, imprisoned , tortured and often even executed (publicly effective in the media). Women are punished for non-compliance with clothing regulations and, in rare cases, stoned for “moral offenses”. The religious community of the Baha'is (and z. B. homosexuals) are criminally and by the "religion guards" followed . In India there are increasing riots by radical Hindus, especially against Muslims.

Ethics of the Abrahamic Religions

The ethics practiced in Judaism , Christianity and Islam differ, among other things, in whether the respective religion is interpreted traditionally or fundamentalistically with a wide individual scope for thought and action . There are also different schools within the individual religions, which interpret and apply the respective moral teaching differently. So there are z. B. in Christianity currents that disregard the Old Testament because of the very violent deity in it.

The three most important revealed religions are linked in their ethical systems by the thought of an end times , but Judaism is less related to the beyond than the other two religions. This linear understanding of time means that the believers in this world live according to the rules demanded by their deity in order to receive the reward for it in a later time, which does not exclude that God already rewards and punishes in this world. In Protestantism, however, divine grace is mostly considered to be decisive, regardless of whether moral postulates are followed. Judaism and Islam have a more legal character and a more comprehensive system of ritual commands and prohibitions than Christianity, which is e.g. B. reflected in the Hebrew word for religion, Torah (law). Similar to Hinduism, there are precise instructions on how the group should act. In the Christian religions today, unlike in the Roman Catholic Middle Ages, u. a. through interpretations of biblical traditions of the statements of their founder , neo-Platonic influences and effects of the Enlightenment in many currents less ritual do's and don'ts.

Jewish ethics

Fundamental to Jewish ethics are the Torah , the main part of the Hebrew Bible , the Talmud - especially the Pirkej Avot it contains and the Halacha , a body of rabbinical statements that has been continuously developed for 1500 years . Even today, the Jewish ethics is further developed through the statements of rabbis of the various branches of Judaism .

Central to Jewish ethics is a passage on charity from Leviticus (3rd Book of Moses) 19, 18, which in German translation reads something like: "Love your neighbor because he is like you". Large parts of the Talmud and much in the Torah are explanations for the concrete implementation of this charity.

Jewish ethics is a central part of Jewish philosophy . Overall, there is no general “Jewish view” of time-bound ethical questions. Very different answers to such questions can be found in Ultra-Orthodox Judaism , Orthodox Judaism , Conservative Judaism , Jewish Reconstructivism and Liberal Judaism .

Christian ethics

The main Christian schools ( Orthodox , Roman Catholic and Protestant Churches ) - as well as other Christian communities - demand that the Christian faith be combined with a moral way of life. The range of what is to be understood by this is often very wide, even within a Christian religious community or church. In theology , a distinction is made between theoretical ethics and its implementation. There is some overlap with biblical ethics, but the field of Christian ethics is broader. As a Christian virtues of faith, love and hope are.

In Christian ethics there are primarily two theoretical positions: the Christian teleological approach and the deontological , ie the doctrine of duties, whereby the two are often connected with one another with different weighting. Teleology discusses the question of meaning and purpose; B. after the “good”, “truth” or the “end” that Christians should strive for (in some Christian concepts this is “union with God”), while Christian deontology understands morality as a duty, laws or other religious ones To fulfill ordinances, especially the Ten Commandments adopted from the Old Testament Jewish faith .

A particularly well-known part of Christian ethics is the invitation (Jesus) to love not only his friends but also his enemies. See Mt 5,44 ff. EU and Lk 6,27 and 32 ff. EU .

Islamic ethics

The ethics in Islam, like in Judaism, are very strongly bound to commandments for almost all areas of life. The Qur'an gives precise instructions on how to act in a group. What is important for Islam is a collective responsibility for good and bad. This is made clear , for example, in the instruction The Right Command and Prohibit the Reprehensible . As a result, there is the possibility of unrestricted authority of the community (see also Hisbah ). Islam goes to its main directions Sunnis and Shiites from the predestination (predestination), which grants the individual only limited room for maneuver. In fundamentalist states, the Sharia is of great importance as Islamic law.

Ethics of (Far) Eastern Religions

In the religions of Indian origin such as Buddhism , Hinduism , Sikhism and Jainism, there is a direct connection between the ethical or unethical behavior of a person and its repercussions in the present life and in future lives ( reincarnation ) or in a future existence in the hereafter. This connection does not arise indirectly through the intervention of a judging, rewarding and punishing divine authority, but is understood as natural law. An act is inevitably linked to its positive or negative effect on the agent ( karma concept). Therefore, the ethical rules are aligned with an accepted universal law or a world principle, which is called Dharma in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism . Detailed ethical instructions are derived from this principle.

The followers of the religious communities are expected to recognize the laws of existence and to act accordingly. In some cases the community sanctions violations of the rules, but far more important for the individual are the assumed negative consequences of wrongdoing in a future form of existence here or in the other.

What these religions have in common is the approach of consistently investigating the mental causes of undesirable actions in order to be able to influence them at the earliest possible stage.

Dealing with the question of violence plays a central role in the ethics of these religions. What they have in common is a fundamental commitment to the ideal of non-violence ( Ahimsa , "non-violence"). Since no fundamental difference is made between humans and other forms of life, the requirement of non-violence extends to the handling of animals and at least theoretically even plants. A consistent implementation of the ideal of non-violence fails, however, because of the need to secure one's own survival at the expense of other forms of life and to defend it against attacks. This results in the need for concessions and compromises, which turn out differently in the individual religions or currents. The question of the permissibility of defensive violence and its legitimacy in individual cases has been and is controversial.

The implementation in the practice of religious followers is also very different. Contrary to a common misconception in the West, neither Hinduism nor Buddhism nor Jainism prohibits the use of military force under any circumstances. Hence, wars waged and continued by followers of these religions are not necessarily violations of religious duties. In addition, in all communities there are far stricter ethical standards for monks and nuns than for lay followers.