Iran

Iran , also: Iran (with article), Persian ايران, DMG Īrān , [ ʔiːˈɾɒːn ] , full form: Islamic Republic of Iran , before 1935 at the international level ( exonym ) also Persia , is a state in the Middle East . With around 83 million inhabitants (as of 2019) and an area of 1,648,195 square kilometers, Iran is one of the 20 largest and most populous countries in the world . The capital, largest city and economic and cultural center of Iran is Tehran , other megacities are Mashhad , Isfahan , Tabriz , Karaj , Shiraz , Ahvaz and Qom . Iran has referred to itself as the Islamic Republic since the Islamic Revolution in 1979 .

Iran consists largely of high mountains and dry, desert-like basins. Its location between the Caspian Sea and the Strait of Hormuz on the Persian Gulf makes it an area of great geostrategic importance with a long history going back to antiquity .

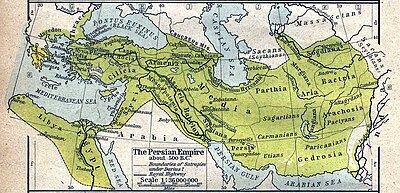

After between 3200 and 2800 BC. BC that. Reich Elam had formed, the Iranian united Medes the area around 625 v. For the first time to a state that took over the cultural and political leadership in the region. The Achaemenid dynasty founded by Cyrus ruled from southern Iran the largest empire in history to date. It was founded in 330 BC. Destroyed by the troops of Alexander the Great . After Alexander, his successors ( Diadochi ) divided the empire among themselves until they settled in the Iranian area around the middle of the 3rd century BC. Were replaced by the Parthians . This was followed from around AD 224 by the Sassanid Empire , which, alongside the Byzantine Empire, was one of the most powerful states in the world until the 7th century . After the spread of Islamic expansion to Persia, in the course of which Zoroastrianism was replaced by Islam, Persian scholars became bearers of the Golden Age until the Mongol storm in the 13th century threw the country back in its development.

The Safavids unified the country and made the Twelve Shiite creed as the state religion in 1501 . Under founded in 1794 Qajar dynasty, the influence of Persia shrank; Russia and Great Britain forced the Persians to make territorial and economic concessions. In 1906 there was a constitutional revolution , as a result of which Persia received its first parliament and a constitution that provided for the separation of powers . As a form of government, it received the constitutional monarchy. The two monarchs of the Pahlavi dynasty pursued a policy of modernization and secularization , in parallel, the country was in World War I by Russian, British and Turkish troops and occupied during World War II by British and Soviet troops . Thereafter, there was repeated foreign influence such as the establishment of an Autonomous Republic of Azerbaijan with Soviet help or a coup d'état organized by the CIA in 1953 . The suppression of the liberal, communist and Islamic opposition led to tensions on a wide scale, culminating in the 1979 revolution and the overthrow of the Shah .

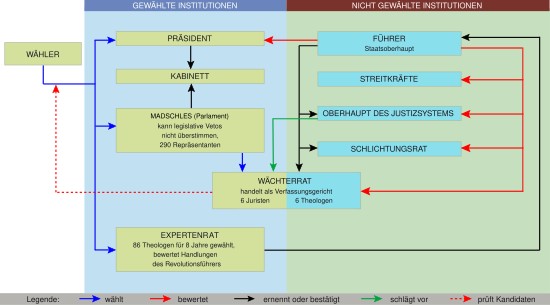

Since then, Iran has been a theocratic republic led by Shiite clergy, at whose head the religious leader concentrates power. It is only checked by the expert council . Regular elections are held, but criticized as undemocratic due to the extensive containment by the rulers, accusations of manipulation and the insignificant position of parliament and the president . The Iranian state controls almost every aspect of daily life for religious and ideological conformity, permeating the lives of all citizens and curtailing individual freedom. There is no comprehensive freedom of the press or freedom of expression in Iran. Since the Islamic Revolution, the good relations with Western states have turned into open hostility, which is firmly anchored in state ideology, especially with regard to the former friends of the USA and Israel . Iran is largely isolated in terms of foreign policy, and at the same time a regional power in the Middle East .

In addition to ethnic Persians, there are numerous other peoples living in Iran who have their own linguistic and cultural identity. The official language is Persian . The largest ethnic groups after the Persians are Azerbaijanis , Kurds, and Lurs . The peoples of Iran have long traditions in handicrafts, architecture, music, calligraphy and poetry; There are numerous UNESCO World Heritage sites in the country .

Thanks to its natural resources, above all the largest natural gas and the fourth largest oil reserves in the world, Iran has a major influence on the world's supply of fossil fuels. Apart from that, the Iranian economy was among other things. Due to the high proportion of inefficient state-owned companies, corruption and the sanctions in the wake of the conflict over the Iranian nuclear program , long in a deep crisis.

Country name

From the earliest times the country was referred to by its people as Irān (an abbreviation of the Middle Persian Ērān šahr ). The old Persian form of this name, Aryānam Xšaθra , means "land of the Aryans " (see also Eran (term) ).

The name Persia , which was used in the West into the 21st century, goes back to Pars (or Parsa / Perser; related to " Parsen "), the heartland of the Achaemenids , who lived in the 6th century BC. A first Persian empire created. Called Persis by the Greeks , it essentially referred to the present-day Fars province around Shiraz . The Persian word Fārsī is derived from it /فارسی/ 'Persian' for the Persian language .

In 1935 the Shah Reza Chan made "Iran" the official name.

The geographical term Iran refers to the entire Iranian highlands .

In German , the word occurs both with a certain masculine article (“der Iran”) and without an article. The Center for Near and Middle Eastern Studies at the Philipps University of Marburg recommends the spelling without articles, which is also common in German academic language. The German Foreign Office does not use the article either.

geography

Iran borders on seven states: in the west and northwest on Iraq (border line 1609 kilometers), Turkey (511 kilometers), Azerbaijan (800 kilometers) and Armenia (48 kilometers), in the northeast and east on Turkmenistan (1205 kilometers) as well to the east and southeast to Afghanistan (945 kilometers) and Pakistan (978 kilometers).

The northernmost point of Iran is at 39 ° 47 ′ north latitude and is roughly on the same latitude as Palma (Spain). The southernmost point is at 25 ° north latitude and is about the same latitude as Doha (Qatar). The most westerly point is at 44 ° 02 ′ east longitude and thus about the same length as Baghdad (Iraq). The most easterly point is at 63 ° 20 ′ east longitude and thus roughly the same length as Herat (Afghanistan).

relief

About two thirds of the territory of Iran is taken up by the highlands of Iran , which in turn are divided into a number of different basins. The extension of these basins ranges from a few square kilometers large Bolsonen to the huge basins of the Lut (130,000 km²) and the Great Kawir (200,000 km²). Depending on their tectonic history, the basins are between 200 m and 1500 m above sea level. The basins are separated from each other by thresholds of different heights; some continue in Afghanistan and Pakistan .

The highlands are bordered in the west, southwest and south by the mountains of Zagros and Kuhrud . These mighty fold mountains consist of several mountain ranges running side by side in a northwest-southeast direction, between which there are steep valleys. Its highest peaks are the Zard Kuh (4571 m) and the Kuh-e-Dinar (4432 m). The Zagros has a maximum width of 250 km and a length of 1800 km ( including the Makran chains ) and is one of the largest closed mountain ranges in the world. The north of Iran is characterized by several mountains. In the northwest, the Armenian-Azerbaijani mountain node dominates with the large basin of Lake Urmi . This is followed by the 1200 km long Elburs - Kopet-Dag system , which extends from the Talysh Mountains to the Turkmen border . Here is the highest mountain in the Middle East at 5670 m, the dormant, glacier-covered volcano Damavand , as well as the 4840 m high Alam-Kuh . The Kopet-Dag is a mighty fold mountain range on the border to today's Turkmenistan . The almost 6000 m difference in altitude from the Caspian Sea to Damavand, only 60 km away, are among the steepest climbs in the world.

There are only a few lowland countries in Iran. On the southern shore of the Caspian Sea there is a 600 km long, only a few kilometers wide coastal lowland. The Turkmen steppe connects to the east and the Mugan steppe to the west . In the southwest, a small part of the Mesopotamian lowlands belongs to Iran, from there a narrow, flat, barren coastline runs along the Persian Gulf.

Geology and soils

Iran is located on the Alpidian mountain belt , which includes the Zagros Mountains. The Iranian highlands, on the other hand, consist of a Precambrian shield, which is considered an extension of the Arabian shield. From the point of view of plate tectonics , the area of what is now Iran was once part of Gondwanaland , which moved to its current position in the late Cretaceous period . The collision with the Arabian plate led to strong volcanic and seismic activity, which resulted in ore formation . This explains why the mountains of Iran sometimes have strong characteristics of the Precambrian mountains, and why there are no mountains that were formed between the Precambrian and Triassic . The sediments in central Iran are on average 3000 to 4000 meters thick, of terrestrial origin and homogeneous. These sediments are partly stored directly on the Precambrian rock, partly on land areas eroded in the Triassic.

The ongoing mountain formation means that earthquakes frequently occur in Iran . Especially the 1600 km long and 250 km wide Zagros fault line is extremely seismically active. On average, stronger earthquakes occur here once a year, but they usually do not assume catastrophic proportions. The areas frequently affected by strong earthquakes lie along the so-called "Iranian Crescent", a region along the country's northern and eastern borders, from western Azerbaijan to Makran . There are numerous smaller faults and faults here, some of which are geologically young and are characterized by irregular quakes. Periods with a high number of quakes alternate with long periods of rest. The already difficult prediction of earthquakes is therefore not possible.

The region around Tabriz is considered to be the most endangered area of the country , where there have already been several particularly severe earthquakes, the last time in 2012 . There are signs that the quake activity alternates between the northwest and the east and that the northwest is currently in a phase of relative calm, whereas the quake activity in the east is peaking. The last devastating earthquakes with thousands of deaths occurred in Tabas (1978), Rascht (1990) and Bam (2003).

Gravel and stone deserts with sterile desert soils , sand dunes and saline soils dominate the highlands of Iran . In the end basins there are mostly salt or gypsum crusts, and there are extensive Serir or Hammada surfaces, where the fine material is blown out due to the absence of vegetation. The humus content of these soils is usually less than 0.5%.

Between the mountain ranges, several types of soil unite to form catenas , the valley floors mostly have filler material from alluvial soils and brown steppe soils, which means they can be used for agriculture. Alluvial soils, brown forest and steppe soils, regosols and lithosols dominate the Caspian lowlands ; loess soils occur in the Turkmen steppe .

Waters

In the north, Iran is bordered by the Caspian Sea, the largest lake in the world and also an end sea, over a length of 756 kilometers . In the south and southwest, the country has a coastline of 2045 kilometers to the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf , separated from each other by the Strait of Hormuz . In this strait near Bandar Abbas , which is important for the transport of crude oil, the island of Qeschm and the eponymous small island of Hormuz are located near the Iranian coast . The distance from the Iranian mainland to the Arabian Peninsula ( Oman and United Arab Emirates ) is barely 50 kilometers here.

There are around 1,300 short, mostly straight rivers that drain the northern flanks of the Talysh and Elburs mountains and flow into the Caspian Sea. The largest are Sefid Rud , Chalus , Gorgan and Atrak . The main rivers that flow from the Zagros towards the Persian Gulf are Karun , Karche , Dez and Schatt al-Arab . They have the most water in spring and can cause devastating flooding in their lower reaches. The water flow is lowest in summer, only a tenth of that in spring.

Two thirds of the territory is not drained towards a sea. In the arid basins of the Iranian highlands, there is hardly a river that carries water all year round, like the Zayandeh Rud . After rainfall, the water flows through rivers or streams out of the mountains and there mostly seeps into gravel fields, more rarely it flows into lakes, which are then often salty. Such lakes include Lake Urmia , the Hamun Lake , the Bakhtegan Lake and Maharlu Lake .

The gravel, limestone and sandstone layers in the subsoil often contain groundwater. That is why there are numerous springs in the mountainous parts of the country, some of them artesian springs . People have been making themselves since 800 BC. The groundwater can be used by means of qanats . In the past, all human settlements in the arid area were supplied with water using qanats. Wells and dams have been built more and more since the 1950s, with the sinking of the lake and groundwater levels, the depletion of water supplies and the sedimentation of reservoirs being the main problems for the water supply of the future. The main focus of environmentalists is the strongly salty Lake Urmia , which is sometimes used as a habitat for pelicans and flamingos, but is threatened by increasing dehydration. The Iranian government has therefore released $ 900 million for the rescue of the lake.

climate

The winter climate in Iran is influenced by the interaction of cold air currents from Central Asia and Siberia on the one hand and warm, humid Mediterranean air masses on the other. In summer there is a constant northeasterly trade wind blowing from the dry and hot Central Asia. Due to these weather conditions and the geographical conditions of the country, the climate is regionally very different.

The mountain regions of northern and western Iran receive a relatively large amount of precipitation due to wet western currents in late autumn and winter, especially on the western slopes of the Zagros . With increasing height, the humidity increases here . The altitude and the relative distance from the sea cause very cold winters and great summer heat. The highlands of Iran lie in the rain shadow of the mountains, so it is everywhere dry to arid with low humidity and large fluctuations in annual rainfall. The annual mean temperatures are significantly higher than in the mountain regions, but they also have a large amplitude: extreme heat in summer, where values above 45 ° C are not uncommon, are sometimes offset by severe frosts in winter. There is never any frost along the Gulf Coast and in Khuzestan . The winters are mild, the summers are very hot and often humid, the humidity is very high all year round, but rainfall is extremely rare. The climate of the Caspian coastal lowlands is fundamentally different from the rest of the country. The winds blowing from the northeast are charged with moisture over the Caspian Sea, accumulate on the mountain ranges and rain down there. Thus, this region is humid all year round with sometimes very high humidity. The climate is mild in winter and warm in summer, the extreme temperatures are significantly reduced compared to the highlands.

The meteorological peculiarities include the consistently north- westerly wind of the 120 days between May and September , which is extremely unfavorable for people and vegetation in the east and south-east of Iran due to its high dust content. In the highlands, where local air pressure differences can be significant due to the lack of vegetation, dust turbulences can be observed regularly .

|

Isfahan's climate diagram (1961–1990)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Climate diagram by Bandar Abbas (1961–1990)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Climate diagram of Tabriz (1961–1990)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Climate diagram by Ramsar (1961–1990)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cities

There were urban settlements in what is now Iran as far back as ancient times . Of many of the early cities, such as Susa , Bischapur or the residential cities of Pasargadae and Persepolis , only ruins have survived, others have disappeared without a trace. It is typical for Iran that the cities outside the regions with sufficient rainfall emerged along the trade routes, for example along the line Zanjan - Qazvin - Tehran - Semnan - Dāmghān - Maschhad - Herat , or Yazd - Kerman . The urban development trend was least pronounced in the south and south-east of the country. When choosing a location, the proximity to water sources that could be made usable with the help of qanats was always decisive. The Iranians almost never built in places that would have been easy to defend. The typical Persian city in Islamic times had the bazaar and the Friday mosque as the center, so there were caravanserais and the residential areas; all of this was enclosed by city walls and fortified gates.

Urbanization began to accelerate in Tehran as early as the 19th century and in the rest of the country in the 1920s, with Tehran and the cities around Tehran experiencing the greatest growth. The city walls were moved or torn down, wide streets and new residential areas were built. Due to the central requirement of these redesigns, the Iranian cities received a relatively uniform cityscape. The new quarters and the newly built infrastructure generally followed Western concepts of urban planning and architecture. The contrast between rich and poor was now also reflected in the cityscape, which had not previously been a feature of Persian cities. Until the 1970s, the historic city centers deteriorated, only the high income from oil production and the increased awareness of the importance of the architectural cultural heritage led to renovation programs from 1973 onwards. Cities continued to grow after the Islamic Revolution, but this trend has recently weakened.

The census of 2011 showed that eight in Iran megacities are: Tehran (8,154,051 inhabitants), Mashhad (2,766,258), Isfahan (1756126) Karaj (1614626), Tabriz (1494998) , Shiraz (1,460,665), Ahwaz (1,112,021) and Qom (1,074,036). Other major cities can be found in the list of major cities in Iran .

Flora and vegetation

Iran's natural vegetation has been largely destroyed by human use for centuries. It can be divided into four zones depending on geographical factors. The deserts and semi-deserts, where the soil is not entirely sterile, have a vegetation that usually covers less than a third of the soil. It consists of wormwood bushes , Rheum ribes , various Astragalus species, Dorema Ammoniacum , the coveted food plant Prosopis Farcta and the wood Zygophyllum atriplicoides . Due to overgrazing, grasses are rarely found, the natural flora includes feather grasses and stipagrostis species.

In the dry forests of the country, which cover the Zagros and other mountains, there are various oaks , maples , hornbeams , cold-resistant junipers , ash trees , paliurus , oleanders and myrtles ; under the bushes dominate pomegranate shrubs , hawthorn , cotoneaster , Prunus types, and rose plants . With increasing drought, particularly on the slopes in the highlands of Iran, the dry forests are very clear mountain almond - pistachio over -Baumfluren where also particularly adapted to drought Watkins - Acacia - and succulent species occur. For Balochistan which is dwarf fan palm typical; the soil in the dry forests is covered by tragacanth and wormwood plants.

The only wet forests in Iran can be found between the Elburs Mountains and the Caspian Sea; biogeographically they are referred to as the Hyrcanic Forest or the Caspian Forest. They are extremely species-rich and tend to be impenetrable because of their climbing plants. The flora of these forests includes trees such as the chestnut-leaved oak , the iron tree , elm , beech , maple , boxwood or blackberry ; many of the species are endemic to the region ; the primeval forests of the oriental beech have only survived in this extent in the far east of the beech area. Cypress forests can also be found in special locations . The Hyrcanic Forests are a hotspot in the context of the CBD process ( Convention on Biological Diversity ). The Parrotia project of Iran, the German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation and the Michael Succow Foundation should lead to the recognition of the Hyrcanic forests as a world natural heritage by UNESCO and to a sustainable protection and use concept.

Special forms of vegetation can be found in the end basins, for example, where halophytic marsh and marsh plants thrive. Gallery forests made up of willows and poplars can sometimes be found along the rivers . In the sand dunes there are stocks of Saxaul , Calligonum species and tamarisk plants .

Wildlife

The fauna in Iran is very diverse and reflects the different vegetation zones and the geographic location of the country. The large animal fauna includes steppe and semi-desert inhabitants such as gazelles and half donkeys as well as wild sheep and wild goats as typical mountain animals , but also porcupines . Red deer are found in the forests of the country . Some brown bears , cheetahs , lynxes and leopards still live in remote areas, while the Caspian tiger and the Persian lion have been exterminated in Iran. Hyenas , jackals and foxes take on an important natural hygienic function. On the south coast of the Caspian Sea there are lagoons with a very high variety of bird species, in the interior there are pheasants , partridges and steppe grouse , which are also hunted. Iranian birds of prey include golden eagles , hawks , bearded vultures and lammergeier vultures . The only bird species endemic to Iran is the Plesky Jay . The fishery on the coast of the Caspian Sea is of great economic importance. The sturgeon is mainly fished for the production of caviar , and mullets and whitefish are also caught. Trout is also fished in the cold mountain streams of Albors and Zagros. An amazing phenomenon is the natural occurrence of small fish in the qanats of the desert areas.

Iran has several protected areas, such as the Arasbaran Conservation Area , Touran Conservation Area , Golestan National Park, and Kawir National Park . A population of Mesopotamian fallow deer , which had become extinct in the wild, was settled on an island in Lake Urmia .

Environmental issues

The accelerated industrialization of Iran has led to extensive air pollution in Tehran and other major cities. Another consequence is the enormous increase in energy consumption. Iran is one of the most energy-intensive countries in the world. This is due, on the one hand, to the lack of advanced infrastructures and government subsidies for energy sources, and, on the other hand, to the inefficient consumer behavior of the population.

As the Iranian Ministry of Health announced in 2010, air pollution is now so severe that the proportion of people who go to hospital emergency rooms with severe breathing difficulties has increased by 19%. In the first nine months of 2010, at least 3,600 people died in Tehran alone as a result of air pollution.

The then Health Minister Marsieh Wahid Dastjscherdi also reported that the Iranian government had no other solutions than the closure of organizations and schools to address the environmental problems of the large cities in today's Iran. Unlike the Ministry of Health, the Iranian government appears to have fewer concerns. This continuously promotes car sales, also because of its own shares in the automotive industry, with over 3.5 million vehicles now dominating the streets in Tehran alone.

The Iranian nuclear program is also causing serious problems in the areas surrounding the nuclear facilities, including water sources, flora and fauna. In addition, the regional location of several nuclear facilities is very worrying. The Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant , which was launched in November 2010, is located for example in a seismically particularly threatened area. This was built exactly on the intersection of three plates (Arab, African and Eurasian). Experts argue that an earthquake on and in the building could cause damage equivalent to the extent of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster . The Kuwaiti geologist Jazem al-Awadi has warned that the radiating leaks would pose a serious threat to the Gulf region, particularly Kuwait, which is only 276 km from the Bushehr facility .

Iran sent a delegation led by then President Ahmadineschād to the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro in 2012 . Iran's participation in the summit, however, faced criticism that Iran does not want to deal with its environmental problems.

Due to the sanctions against the country, the ideologized goal of self-sufficiency is adhered to. Most of the available water in dry land is used in inefficient arable farming. Awareness of the catastrophic effects of river diversions began to rise and activists were allowed to criticize the government on television in 2017. On the other hand, there is a lobby of construction companies that build such works. Kaveh Madani , deputy head of the Iranian environmental department for a few months from September 2017 to January 2018, coined the term “Iranian water bankruptcy”.

population

Iran today has a population roughly equivalent to that of Germany, but which is spread over four and a half times as large a territory. The average population density is thus 46 inhabitants / km². However, the distribution of the population is very uneven. The areas that are preferred in terms of their environmental conditions have a very high population density, for example the provinces on the Caspian Sea (provinces Gilan and Mazandaran with 177 and 129 inhabitants / km²) or along the Alborz ( provinces Tehran and Alborz with 890 and 471 inhabitants / km²). In contrast, the areas dominated by deserts are extremely sparsely populated or not populated at all: in Semnan , South Khorasan and Yazd only 6, 7 and 8 people live on one square kilometer, respectively.

Population development

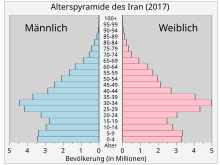

At the beginning of the 20th century, Iran had fewer than 12 million inhabitants, 25 to 30% of whom were nomadic and only 15% in cities. By 1976 the population had grown to 33.7 million people. The last census in 2016 finally showed almost 80 million people. The urban population had risen to about a third by 1956 and to just under half of the total population by 1976; In 2011, 70% of all Iranians lived in cities.

The significant increase in life expectancy is primarily responsible for the strong growth in the population: at the beginning of the 20th century, people lived on average just under 30 years old and child mortality was around 50%. In 2015, however, the average life expectancy was 76.2 years for women and 74.0 years for men. At the same time, fertility remained at a very high level for a long time: in 1956 with an average of 7.9 children per woman, and in 1986 with 6.39 children per woman. It has fallen sharply since then and in 2008 was only 1.81 children per woman. In 2018 the fertility was 2.1 and thus roughly at the conservation level. The world average in 2018 was 2.42. Only in Japan after World War II can a more rapid decline in fertility be observed. As a result, natural population growth has slowed, from 2010 to 2013 it was 1.1% per year. This population development results in an on average still very young but steadily aging Iranian population. While the average age of Iranians in 1976 was 22.4 years, it was 29.86 years in 2011, increasing by around two years every decade. Three quarters of Iranians are under 40 and 55% of Iranians are under 30.

During the same period, the number of households rose disproportionately, so that the average size of an Iranian household fell from 5 people in 1976 to only 3.5 people in 2011.

migration

It is estimated that around four million people of Iranian descent live outside of Iran today; in 2010, about 1.3 million Iranian nationals, about 1.7% of the population, lived outside the country. The most important destination countries for Iranian emigrants include the USA, Canada, the northern EU states, Israel and the rich countries bordering the Persian Gulf such as Qatar, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates. Since there are many well-educated young people among the emigrants, the losses caused by emigration for the Iranian economy seem massive: around 50 billion US dollars are supposed to be lost through the brain drain every year . The funds flowing back into Iran from exile each year add up to around 1.1 billion US dollars. The Iranian diaspora, which is connected to its homeland, is also an important part of the opinion-forming of the Iranian population via Persian-language radio and television stations as well as blogs.

Iran is also a destination for immigration. The 2011 census showed that almost 1.7 million foreigners lived in Iran, almost half of whom came as refugees. The majority of the foreigners (1.45 million) came from Afghanistan. Afghans have been migrating to Iran for many decades, on the one hand as labor migrants, but increasingly as refugees since the Soviet invasion and the subsequent wars. Since many Afghans speak a variant of Persian and also have a very similar cultural and religious background, it is relatively easy for them to integrate in Iran and to impersonate Persians in censuses; the number of Afghans could thus be significantly higher. Nonetheless, Afghans in Iran are also exposed to discrimination. In addition to the Afghans, around 50,000 Iraqis and 17,000 Pakistanis live in Iran; other countries of origin of immigrants are Azerbaijan, Turkey, Armenia and Turkmenistan.

ethnicities

The mediating position of Iran between Central Asia, Asia Minor, Arabia and the Indian subcontinent has resulted in a high degree of ethnic diversity. Indo-European groups probably immigrated from the north into the Iranian highlands and reached the Zagros at the beginning of the first millennium BC. The Medes were the first Iranian people who could establish a stable empire on Iranian territory. After the Arab conquest of Iran, Arabs settled all over the country and mingled with the local population; many Iranian families can prove their Arab origin by their names. In the 11th century, Turkish tribes began to immigrate to what is now Iran in ever new waves. With their nomadic way of life, they shaped large areas of Iran up to the beginning of the 20th century; in the end they settled mainly in the north-west of the country, where the climate is most suitable for nomadic cattle breeding.

The peoples of Indo-European origin dominate the country numerically today. Between 60 and 65% of the population are Persians ; the Iranian highlands are almost exclusively inhabited by Persians. To the west of the Persian settlement area live Kurds, who make up 7 to 10% of the total population, speak a language related to Persian and mostly follow Sunni Islam, and the predominantly Shiite Lurs (6% of the population of Iran). The Baluchi , who are also Sunni and make up 2% of the population, live in eastern Iran . Smaller Indo-European peoples are z. B. the Bakhtiars .

The Turkic-speaking peoples mainly include the mostly Shiite Azerbaijanis ( Azeri ), who make up 17 to 21% of the population of Iran and live in the north-west of the country. The mostly Sunni Turkmens inhabit the northern steppe areas, and there are also numerous islands of Turkish ethnic groups scattered all over the country, to which the Kashgai belong.

The Arabs of Iran live in the southwest on the border with Iraq; they make up about 2 to 3% of the total population. There are also a large number of very small ethnic groups living in Iran, some of which settled in Iran before the arrival of the Persians (like the Assyrians ) or came into the country in several waves, some centuries ago (like the Armenians ).

The available figures on the ethnic composition of the Iranian population vary greatly because the Iranian state does not determine and publish any data. Last but not least, mixed marriages, which are now normal, lead to a certain blurring of ethnic boundaries. It can be assumed that the linguistic assignment to the original ethnic groups is not always possible, since large parts of the minorities are now mainly linguistically assimilated to the Persian majority culture.

languages

Different languages are spoken in the multi-ethnic state of Iran. The official language is Persian . It belongs to the family of Indo-European languages and therefore has no common roots with Arabic , although Persian has taken up numerous loanwords from Arabic and is written with an alphabet derived from Arabic . Persian is spoken as a first language by only more than half of Iranians; Almost all residents of the Iranian plateau speak Persian. In 2000, 85% of Iranians mastered Persian as their mother tongue or second language , another 5% could understand it, and only 10% did not speak it at all. In the 1930s, each ethnic group could only speak its own language; Recruits drafted into the military therefore had to learn Persian for six months.

The part of the population whose mother tongue is not Persian is divided into several language groups that live mainly in the periphery, along the borders. Minority languages include those that are related to Persian such as Kurdish , Mazandaran , Gilaki , Pashtun , Lurian , Bakhtiarian , Baluch and Talish ; Overall, around 70% of Iranians speak an Indo-Iranian language . Turkic languages are spoken by around 18 to 27% of Iranians, depending on the source, mainly in the north-west and north-east of the country; this includes Azerbaijani , but also Turkmen , Kashgaish , Khorasan Turkish and Afsharic . The Arabic language is spoken by around 2% of the population in Iran. As the language of the Koran , however, it is learned by all children in school. Since multilingualism is a matter of course for Iranians nowadays, there are very divergent numbers for the exact distribution of the speakers across the many different languages. The Persian dialects spoken in Iran include the Bandari and the Sistani as well as the Chuzi (in the province of Fars ). Also dardische dialects as Kohestani are spoken.

The Iranian constitution defines the Persian language as the sole official and educational language. However, it is allowed to teach the minority languages alongside Persian in schools. English is the second foreign language in schools after Arabic.

religion

Despite modernization and 50 years of secularization under the Pahlavi, Iran is today a state in which religion pervades almost every aspect of social life. The 2011 census found that 99.4% of Iran's citizens are Muslim. It is estimated that 89% to 95% of Iranians belong to the state religion of the Twelve Shia and the remaining 4% to 10% to Sunni Islam . A study by the GAMAAN institute in 2020 came to a significantly different result. According to this, 32% of the Iranian population describe themselves as Shiites, 9% as atheists, 8% as Zoroastrians, 7% as spiritual, 6% as agnostics and 5% as Sunnis. Smaller proportions describe themselves as Sufis, humanists, Christians , Bahais and Jews , 22% do not identify with any of these world views.

The belief in Shi'aism is one of the characteristics that most distinguish Iran from its neighbors. The basic contents such as the belief in a single, almighty and eternal God as well as in Mohammed as the last of the prophets that God sent to the people to convey his message, are identical for Shiites and Sunnis. The fundamental difference between these two currents of Islam lies in the question of who is authorized to lead the Islamic community. The Shiites only recognize the direct descendants of the Prophet Muhammad as legitimate leaders and refer to them as imams . A total of twelve imams lived. The central belief of the Twelve Shi'ahs is the secretive twelfth imam who would one day come back to earth, spread Islam all over the world and usher in an era that precedes the end of the world. The Imams and their descendants are very venerated by the Shiites. Shrines were built around the graves of these people and their relatives , of which there are more than a thousand in Iran. The more important of these shrines, such as the Imam Reza Shrine or the Shrine of Fatima Masuma , are destinations for pilgrimages; a practice that is rejected by the Sunnis. Another peculiarity of the Shiite creed is the Taghiyeh permission to hide one's beliefs and neglect religious duties if the believer would otherwise be in danger. The Sunni creed is particularly widespread among ethnic groups who live in the border areas with neighboring countries, such as the Kurds , Turkmens or Baluch . The Shiite leadership does not regard the Iranian Sunnis as a minority, but as Muslims who have recognized the Shiites' claim to leadership. As a result, only Shiite-run mosques are available in predominantly Shiite areas.

Religious minorities in Iran today comprise only very small groups, but they are of great importance from a historical and cultural point of view. The oldest known Iranian religion is Zoroastrianism . It was made between 1200 and 700 BC. Donated by Zarathustra ; Variants of Zoroastrianism were considered the state religion under the Sassanids and Parthians . Above all, monotheism , which was innovative for the time, and religious dualism (heaven and hell, God and devil ) influenced religions that emerged later. Some Iranian festivals that are still celebrated today contain Zoroastrian elements, sometimes in a syncretic form. The constitution recognizes the Zoroastrians as a religious minority; in the 2011 census, more than 25,000 people identified themselves as Zoroastrians. Their centers are in Yazd and Kerman , where holy flames still burn in the fire temples .

Jews have lived in modern-day Iran since ancient times; conversely, Iran has an important place in Jewish history because King Cyrus II made it possible for Jewish parts of the population to return from exile in Babylon . Over time, the Jews were so assimilated that they differ from other Iranians only in their religion. The Jewish community , which had around 80,000 members before 1979, has shrunk sharply to around 20,000 members since the Islamic Revolution. This is mainly due to the anti-Zionist policies of the Iranian government, through which Iranian Jews are easily suspected of being Israeli spies.

The Christianity in Iran also has a long history; before the Islamization of Iran, many Nestorians immigrated to what is now Iran. Today around 60,000 Assyrian Christians live in Iran and the descendants of the approximately 300,000 Armenian Christians who were brought into the country under the Safavids ; its center is still in Isfahan to this day . There are also Roman Catholic , Anglican, Protestant and other Christian communities and churches .

Articles 13 and 14 of the Iranian Constitution recognize Christianity, Judaism and Zoroasterism as religious minorities. They stipulate that the Iranian state must treat them fairly and protect their practice of belief, rites and ceremonies. The religious minorities elect their own deputies in parliamentary elections, for whom a minimum number of parliamentary seats are reserved. However, these religious communities are not allowed to engage in activities against Islam or the Islamic Republic. For example, they must observe the dress code in public and are not allowed to recruit members from among Muslims . Muslims in Iran face the death penalty for apostasy . In practice, all members of religious minorities are exposed to a subtle form of discrimination, such as job choice in the state-dominated economy, inheritance law or witness statements. They are also closed to higher offices such as ministers, state secretaries, judges or teachers in regular schools.

As the largest non-Muslim religion in Iran, the true Bahá'í Faith . It emerged from Shiite Islam in the middle of the 19th century, when a benefactor (the Bab ) described himself first as the gateway to the twelfth Imam and later as the twelfth Imam himself, and with several followers such as Qurrat al-Ain developed and developed an active missionary activity declared the Islamic laws abolished. Bahāʾullāh later formed the now internationally represented Bahaitum from Babism . This religion has been regarded as heresy since its inception and has been fought accordingly in many Islamic countries. The persecution intensified in Iran after the Islamic revolution again. Baha'i is officially banned in Iran, so its approximately 300,000 followers practice their religion underground, because professing Baha'i are excluded from higher education or work for the state; they also risk arrest and execution.

socialsystem

In his book The Islamic State , Ruhollah Khomeini formulated the improvement of the living conditions of the poor population and the elimination of social inequality as goals of an Islamic social order:

“Nobody cares about the poor and barefooted […] Islam solves the problem of poverty. This problem is at the top of his program […]. According to the principles of Islam, the life of the poor and the helpless must first be improved. "

93% of the Iranian population have received direct payments of US $ 40 per month since the subsidy reforms cut direct subsidies for staple foods and fuel. Apart from the support programs of the religious foundations, the state has 28 organizations for social assistance, social security and aid programs. The basis is the social security law. The Social Security Organization, which is subordinate to the Ministry, offers social insurance in the form of unemployment benefits, pensions, maternity benefits, sick pay and health services (2nd health provider in the country, for pensioners, unemployed, social insured persons). In 2011 the World Bank certified that the IRI had a relatively high social indicator compared to regional standards, due to the efforts of the government to increase access to education and health care. The current five-year plan continues to focus on social policy.

Despite these efforts, major problems with poverty persist. According to an official statistical survey, between 44.5 and 55% of the urban population lived below the poverty line in 2011. The scientists also criticized manipulation in the publication of poverty statistics. According to official statistics, there are 2.5 million street children in Iran who have only recently come into the focus of government welfare organizations.

Iran is home to the second largest refugee population in the world (mostly from Afghanistan). The UNHCR works with state welfare organizations and the Imam Khomeini Aid Committee to help refugees who do not benefit from other state social benefits.

training

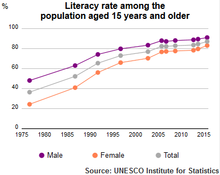

In the last 30 years the level of education of the Iranian population has improved significantly, despite the turmoil the education system was exposed to in the years after the Islamic Revolution. In the country, the mean school attendance for over 25s increased from 4.2 years in 1990 to 8.5 years in 2015. The current educational expectation is already 14.8 years. Women were able to participate more than men in the improvements. Specifically, in the 2006 census, the illiteracy rate of all citizens over the age of 6 was 14%, while in 1976 just under half of men and only a third of women could read and write. The share of illiterate people in the rural population has fallen from 75% (1976) to 22% (2006).

The proportion of boys in elementary and secondary schools is only slightly higher than that of girls; in higher education, young women made up around 60% of students in 2006. There is therefore no longer any gender-specific gap with regard to education among the young income groups. In the natural sciences and mathematics in particular, the proportion of women among students in Iran is very high in an international comparison. In 2012, the Ahmadinejah government introduced quotas of a maximum of 50% women or less for some subjects. The United Nations criticized this practice, which led to a decrease in the proportion of women from 62% in 2007–2008 to 48.2% in 2012–2013. These provisions have been repealed by the Rouhani government. In 2015, the proportion of women studying science or mathematics in Iran was 65%, while it is much lower in Europe.

The education system of Iran today consists of several levels:

- a non-compulsory one-year preschool for all children aged five and over

- the five-year primary school for all children aged six and over

- this is followed by a three-year middle school, in which the further educational path of the student is determined; after her compulsory schooling ends.

- the secondary school, which lasts three years, is usually not free and is divided into several specializations

- higher education at universities, teacher training institutes and technical colleges, of which there are state and private institutions. The prerequisite for access to higher education is the completion of secondary school, participation in a one-year preparatory course and passing the nationwide university entrance exam.

In addition to the state schools, numerous mosques are affiliated with religious schools. The generous budgets that the government allocates to religious schools are blamed for the lack of money in the state schools and the associated low quality of teaching and the low salaries of teachers. According to Salehi-Isfahani, Iran's education system is also focused on the acquisition of diplomas and not on teaching productive skills. This and the rigid labor market cause high macroeconomic inefficiencies, and not least, the high unemployment among young people is attributed to this.

Bless you

Iran is a country where extramarital intercourse ( zinā ) can be punished with the death penalty, and where conservative moral standards are very important, knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases , HIV or contraception, if at all, only becomes apparent after marriage conveyed. Because of this, knowledge of the ways in which sexually transmitted diseases are spread is extremely poor. In 1997 the Iranian government still denied the existence of an HIV problem in the country. For 2004 the number of HIV-positive Iranians was estimated at 10,000 to 61,000, for 2014 at 51,000 to 110,000 people. The lack of knowledge about contraceptives, their high price and their lack of acceptance among the population lead to a high number of unauthorized or unwanted pregnancies that are terminated in illegal clinics . Even more frequently, the women affected use dangerous substances from animal breeding to terminate their pregnancy and cause serious damage to their health.

The use of mind-altering substances has a long history in Iran. 400 years ago attempts were made to limit drug use; At the beginning of the 20th century, opium was deeply interwoven with the Iranian economy and society. It was the most profitable agricultural product and was widely consumed in the face of wars, famine and the lack of medical care. According to one estimate, around 10 percent of Tehran's population were addicted to opium in 1914. The modernizers of the Pahlavi dynasty identified drug use as one of the obstacles to the development of Iran into a strong state; In 1955 the production and use of opium were banned. However, this measure did not solve the problem; an infrastructure for the treatment of drug addicts was slowly emerging. After the Islamic Revolution, these institutions were abolished. Attempts were now made to deal with the drug problem by enforcing religious and moral behavior. Drug offenses were and are punished severely under criminal law; The Iranian Narcotics Act prescribes the death penalty for numerous offenses. The majority of those executed in recent years have been convicted of drug offenses. These measures have not been fruitful, so that measures of a worldly nature have been initiated. Since then, facilities for treating drug addicts have been permitted again and are being promoted. Attempts are also made to educate the population about the dangers of drug use. Iran had the fourth highest drug death rate in the world in 2011. According to drug control and health authorities, over 2.2 million Iranians are addicted to illegal drugs, 1.3 million of whom are in treatment programs. In particular, crystal meth is (as of 2015) in particular demand. Students use it in exams; Workers who can only keep themselves afloat with several jobs use it as a pick-me-up.

- Development of life expectancy over time

| Period | Life expectancy in years |

Period | Life expectancy in years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950-1955 | 40.58 | 1985-1990 | 59.97 |

| 1955-1960 | 43.50 | 1990-1995 | 66.87 |

| 1960-1965 | 46.38 | 1995-2000 | 69.04 |

| 1965-1970 | 49.18 | 2000-2005 | 71.12 |

| 1970-1975 | 52.67 | 2005-2010 | 72.73 |

| 1975-1980 | 56.71 | 2010-2015 | 75.06 |

| 1980-1985 | 51.99 |

women

Traditional Iranian society is strictly patriarchal ; At the beginning of the 20th century, almost exclusively men could be seen in the Iranian cityscape, women usually stayed at home. The degree to which women were tied to the house differed from ethnic group to ethnic group in the past: under the Lurs men had absolute power over women, while the Kashgai women had a relatively high degree of freedom. In the 1920s, only a few girls were able to attend school; Only the Pahlavi government encouraged parents to send their daughters to school as part of the country's modernization efforts in the 1930s. In 1936 the veil was banned. Although the ban could never be fully enforced, it has resulted in women from conservative sections of the population being pushed even more out of public life and in some cases not leaving the house at all. As modernization progressed, women found more and more jobs outside the home, especially as state employees. In the 1960s, the situation of women was further improved as part of the white revolution : they were given the right to vote in 1963 , abortion was allowed and secular courts were made competent for divorce issues.

After the Islamic Revolution, these reforms were reversed. Since then, Articles 20 and 21 of the Constitution of Iran have stipulated that men and women have equal rights, taking into account Islamic principles . While the husband is responsible for feeding the family, the wife has to do the housework and is obliged to be obedient to her husband. Husbands have “the right” to the sexual availability of their wives and may enforce this with violence. General domestic violence by the husband against the wife is also largely permitted. Women are also only allowed to work, travel, visit their own parents, have a passport or get divorced with the consent of the man. Beatings or sexual violence by the man are expressly not grounds for divorce, but conversely, the man can expel his wife at any time. In court, statements made by a woman are only half as effective as those made by a man, and only half of the blood money is due for the injury or death of a woman under the so-called “right of retribution” . Iranian law provides for the death penalty for sexual intercourse outside of marriage, which puts victims of rape in a particularly precarious position. Men are allowed polygamy and temporary marriage ; the legal minimum age for girls is 13 years. These rules partly contradict the socially recognized values in today's Iran, so clergymen also live in monogamy .

Despite all this, it was no longer possible to ban women from the public after the Islamic revolution, because they had supported the Islamic revolution and were needed as workers in the Iran-Iraq war . A side effect of the strict public customs of the Islamic Republic is that conservative parents no longer have any reason to deny their daughters school and study. The level of education of Iranian women is therefore higher today than ever before, so that women in Iran can be found in almost all professions up to and including car racing ( Laleh Sadigh ) and higher education at universities. Secularly oriented women let their future husbands sign marriage contracts that give them all those rights that the law denies them. With the help of lawyers, they can enforce divorces by soliciting the dowry . A religious debate about equality for women has started since graduates from Islamic universities have also been practicing Koranic exegesis . Although Iranian criminal law threatens a violation of the obligation to wear a hijab with imprisonment, women defy Islamic dress codes by repeatedly testing the limits of what is permitted.

story

Ancient and Middle Ages

The present-day national territory of Iran includes the historical heartland of ancient Persia, which historically extended over a significantly larger area at times. Up until the 20th century, Iran was referred to as Persia in official international parlance around the world. Its geographical location between the Caucasus in the north, the Arabian Peninsula in the south, India and China in the east and Mesopotamia and Syria in the west made the country the scene of an eventful history.

In the Persian metropolitan area, Iran's history leads from the kingdom of the Elamites and the Medes to the Persian Empire of the Achaemenids ( Cyrus II the Great to Darius III ) and via Alexander the Great and the Diadochian Empire of the Seleucids to the Parthians and Sassanids .

Spread of Islam

The wars with Byzantium had weakened the Sassanid state militarily and financially to such an extent that internal unrest and vulnerability to external enemies were the result. The empire fell victim to an incursion by the nomadic inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula, of whom there had already been very many before ( Islamic expansion ): In 637 the Persians lost the battle of Kadesia , shortly afterwards the capital Ctesiphon was lost. The Arabs, united and motivated by the new religion of Islam, conquered the entire Sassanid Empire in a short time, and the slow process of Islamization of Iran began . Although non-Muslims were allowed to practice their religion, they had to pay a tax and observe numerous prohibitions; there were still large Zoroastrian communities in the 13th century . Unprepared to rule such a large empire, the Arabs adopted the Sassanid government structures. In contrast to other areas conquered by the Arabs, the Persians succeeded in largely preserving their culture, making Persian one of the languages of Islam alongside Arabic, and making a decisive contribution to the development of Islam in cultural, political and intellectual areas.

Despite the important role the Iranians played in Islamic culture, they were initially disadvantaged as mawālī or even dhimmi . The fourth caliph Ali , who advocated the abolition of this disadvantage, therefore had a particularly large number of supporters among the Iranians. This was an important factor in the dispute over the legitimacy of the Islamic community's claim to leadership and its subsequent break-up into Sunni and Shi'aism . When the Umayyad dynasty was overthrown in 750 and the subsequent establishment of the Abbasid caliph dynasty in Baghdad, which was strongly based on the Sassanid model , Iranian rebels under General Abu Muslim played a decisive role in the fighting. After the power of the caliphs eroded in favor of the Turkish-born military, several regional dynasties actually ruled the country in the 9th and 10th centuries, including the Tahirids , the Saffarids and the Bujids , who acted as the protective power of the Abbassid caliph from 945. Among the Samanids , whose capital was in Bukhara , numerous Sassanid works were translated into Arabic, which accelerated the adoption of Iranian ideas into Islam. Under the Samanids, Islam also broke away from its Arab origins and began to become a cosmopolitan religion.

Turkish and Mongolian invasions

As early as the 9th and 10th centuries , Mamluks , known as Mamluks , were incorporated into the armies from the Turkic peoples of Central Asia . Beginning in the 11th century, nomads of the Turkic peoples immigrated and settled on the territory of today's Iran. They built short-lived empires based on the Iranian-Samanid model on their military base, and had themselves confirmed as Sunnis by the Abbassid caliph in Baghdad. These ruling houses include the Ghaznavids and the Seljuks . They promoted art, culture, medicine and science: the works of the great poets Omar Chayyām , Rumi and Ferdosi fall into this era. After the Seljuq dynasty had passed its zenith, the country split again into several local empires; there was severe internal Shiite fighting between the Ismailis and the Twelve Shiites .

In 1219 the Mongols invaded Iran under Genghis Khan , in whose army numerous Turks fought. The Mongols destroyed and plundered the Iranian cities, the population shrank dramatically, arable land and irrigation systems deteriorated and the central powers dissolved. From 1256 to 1335 Iran was part of the Ilkhan Empire . After the murder of the last Ilkhan, local empires were able to form again. A short time later, however, the Iranian highlands were again overrun from Central Asia, this time by the troops of Timur , who founded the Timurid dynasty in 1381, which ruled until 1507. Some areas never recovered from the devastation of the Mongol storm. The turmoil of the Mongolian and Timurid rule contributed to the emergence of popular Islam and the dervish culture.

Safavids

After an interlude of the Turkmen tribes Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu , who were able to rule the entire Iranian territory for a time, the Safavids succeeded in reestablishing a stable state. They had their origins in a Turkmen dervish order, which had achieved great wealth and organized its followers militarily ( Kizilbasch ). In 1501 they introduced the Twelve Shia as the state religion; it has represented a unifying bond in the Iranian multi-ethnic state at least since the end of the Safavid period. The Safavid Empire was in constant conflict with the Ottoman Empire , which was at the zenith of its power in the 16th century. Today's Iraq, with its shrines that are sacred to the Shiites, left Iranian territory forever in the course of this conflict. During this time, diplomatic contacts with European countries and the beginning of sea trade with Europe in the Persian Gulf were intensified. The Safavids reached the height of power under Shah Abbas I , who replaced the Kizilbash associated with their respective tribe with an army loyal only to the Shah and made the city of Isfahan his splendid residence. Contributing to the downfall of the Safavids was the fact that the army devoured large resources, that Abbas I's successors were largely incapable and that the Sunni minority was persecuted. The Shiite scholars gained significantly in power under the declining Safavids and began to play an opposition role to the monarchy.

During the rule of the Safavids, the number of nomads increased further, so that the pressure on the settled peasants increased and the nomads armed themselves. This military power remained an important factor into the 20th century. The Safavid dynasty was eventually overthrown by an Afghan invasion. However, the Afghans were driven out by a nomad leader who was crowned Nadir Shah in 1736 , made extensive conquests, but was murdered in 1747. While southern Iran experienced calm and prosperity beneath the Zand , chaos reigned in the north.

Qajars

The trunk of the Qajar was originally settled by Abbas I to border security purposes. They conquered Northern Iran, overthrew the Zand and in 1796 crowned Agha Mohamed as Shah; In contrast to their predecessor dynasty, however, the Qajars did not achieve religious legitimation of their power. They also missed the goal of expanding their empire to the borders of the Safavid Empire. The conflict with Russia and Great Britain began at the beginning of the Qajar era. By 1828 the Caucasus was lost to Russia and Russia was given a say in the Iranian succession to the throne. Great Britain achieved that large areas of eastern Iran became part of Afghanistan . In view of this threat situation, first attempts were made to reform the Iranian state and its military (defensive modernization) . These initiatives, which went back to ministers or princes, were unsuccessful due to a lack of money and opposition from conservative dignitaries or the Shah himself. After all, with Dar al-Fonun, the first higher educational institution was founded and textbooks were translated.

The Constitutional Revolution

The fact that the Shah's government was barely able to collect taxes opened the door for European states to exert economic influence. This was done primarily through the award of concessions, which foreigners left parts of the economy in return for paying small taxes, such as the establishment of the telegraph network, fishing rights, the operation of banks or oil explorations from the 1860s onwards . The climax of this development was reached with the tobacco monopoly for a British consortium, which led to a complete boycott of tobacco and the withdrawal of the concession - the first successful movement of traders, clergy and intellectuals against the rulers. In this environment, the clergy were able to distinguish themselves as defenders of national interests and, under the influence of intellectuals such as Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani, developed a militant Islam. When the Shah wanted to make further concessions to Russia in view of the bankruptcy of the country in 1905, months of unrest and a constitutional revolution ensued, as a result of which Iran received its first parliament . It passed the first constitution on August 5, 1906 , which was extensively expanded in 1907. It provided for popular sovereignty , basic rights and a separation of powers based on the Western model, but also the compatibility of all laws with Sharia law and a supervisory body made up of five clergymen. This constitution remained in force on paper until 1979. Thus, the constitutional revolution ended the absolute monarchy in Iran.

The new form of government, the constitutional monarchy , initially only lasted 15 years, it tended more and more to chaos and disintegration and, overall, brought neither stability nor progress to the country. As early as 1908, Mohammed Ali Shah staged a coup and had parliament shot at; numerous MPs were arrested and some were executed. The year-long civil war led to Mohammad Ali's resignation. The successor to the throne was Ahmad Shah , who was initially represented by a regent . Russia and Great Britain had divided the country into zones of influence and forced the Shah to dismiss the American expert Morgan Shuster, who was employed to solve the chronic financial crisis . During the First World War , fierce battles between Russia, Great Britain and the Ottoman Empire were fought on Iranian territory, despite the declaration of neutrality. After the October Revolution, the Russian army withdrew. British plans to turn Iran into a British protectorate , however, failed. Towards the end of the Qajar dynasty, the power of the Shah was limited to the capital. The armed forces consisted only of a Cossack brigade , commanded by Russian officers, a paramilitary gendarmerie, and lightly armed nomad fighters. The state had no organization to enforce its power and was dependent on large landowners, tribal leaders and clergy. Between 1917 and 1921, two million people, a quarter of the rural population, died in Iran as a result of war and subsequent epidemics and famine.

Against the backdrop of the threat of state collapse , the Cossack brigade under Reza Khan launched a coup and forced Prime Minister Sepahdar to resign. Reza Khan was first commander-in-chief of the Cossack Brigade, then Minister of War under Seyyed Zia al Din Tabatabai and later Ahmad Qavām as Prime Minister. In this function he reformed the Iranian military and violently took action against several movements with tendencies towards secession, such as in Tabriz , Mashhad , the Soviet Socialist Republic of Iran of Mirza Kuchak Khan , the Bakhtiars and Kashgai . Strengthened by these successes, Reza Khan became Prime Minister in 1923. Efforts to make a republic with Reza Khan as the first president in analogy to the proclamation of the Turkish republic from Iran failed because of the resistance of the clergy. Finally, at the end of 1925, parliament deposed the last Qajar Shah and declared Reza Khan to be Reza Shah Pahlavi. He crowned himself in April 1926.

Pahlavis

Reza Shah was a staunch leader and the first in a long time to tackle real reform. A modern education system was introduced and the judicial system was reformed. The jurisdiction of foreign powers over their citizens in Iran has been abolished. A state tea and sugar monopoly was created; with the proceeds from it the Trans-Iranian Railway was built; roads and other railway lines also emerged. The foreign banks were nationalized and new banks were founded. The situation of women has improved; Western clothing was prescribed for all men, with the exception of the clergy, and women were forbidden to wear the veil. In 1925, general conscription was introduced and sometimes enforced by force, thus, against the resistance of the clergy and landowners, all young men in the country were torn from their traditional careers and went through a nationalist-secular training. The law on identity and personal status obliged all Iranians to use a surname, to be registered with the newly created registration authorities and to carry an identity card with them; the Qajar titles were deleted without replacement. These two measures created the basis for the implementation of a central state at the expense of the local rulers. Reza Shah also began the policy of turning to pre-Islamic Iran, using the crown , cloak and banner based on the old Iranian model, introducing the Iranian calendar and demanding from abroad from 1935 - not entirely uninfluenced by National Socialist Germany , with which the Shah maintained good relations to name the country of Iran ("Land of the Aryans") and no longer Persia . Reza Shah, however, ruled dictatorially and only kept parliament to give his rule the appearance of legitimacy and constitutionality. He personally appropriated huge estates, arranged for the bloody sedentarism of the nomads, eliminated critics and, in the later course of his rule, also comrades-in-arms.

Although Reza Shah owed his rise largely to British influence, he did everything in his power to curtail Britain's influence on events in Iran. His attempt to position the USA as a counterweight to Great Britain and the Soviet Union failed. Germany, ruled by the National Socialists at the time, gladly took on this role and subsequently became Iran's most important partner. After the outbreak of World War II, Great Britain demanded entry into the war on the side of the Allies and the expulsion of the numerous German advisors, which Reza Shah only agreed to after a long period of hesitation. The Iranian government declared Iran neutral and demanded that Great Britain and the Soviet Union respect this decision. In order to secure access to the oil reserves and the supply of military material to the Soviet Union via the Trans-Iranian Railway, British and Soviet troops marched into Iran on August 25, 1941 without a declaration of war (see: Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran ). The resistance of the Iranian army collapsed after 48 hours. Reza Shah was forced to abdicate. There was no public outcry; his then 22-year-old son succeeded him on the throne.

The decade that immediately followed these events is known in Iran as the Constitutional Rebirth . Freedom of expression, freedom of the press and pluralism prevailed like never before in this country. Two important developments occurred during this period. Contrary to its promises, the Soviet Union had left its troops in northwestern Iran and supported the pro-communist governments in Iranian Azerbaijan and Kurdistan during the Iran crisis . Only after American pressure did the Soviet Union agree to withdraw and the Iranian army was able to smash the two secessionist states. The second development was the nationalization of the oil industry, which has been called for since 1941 and passed by parliament in 1951. The British government, which needed the revenues of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company , subsequently organized a boycott of Iranian oil, which led to the Abadan crisis and brought the Iranian state to the brink of bankruptcy. The still popular Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh , who is most identified with nationalization, tried at the same time to curtail the Shah's powers. In 1953, tensions peaked and the Shah fled the country. Mohammad Mossadegh was overthrown a little later with Operation Ajax with the help of the CIA , and Shah Mohammed Reza subsequently established an autocracy with the support of the USA.

Monarchist forces led by General Fazlollah Zahedi arrested Mossadegh. The Shah returned to Iran. The then government, with Zahedi as prime minister, began new negotiations with an international consortium of oil companies. The negotiations lasted for several years. In the end there was an agreement that would last until the first oil crisis .

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (1941–1979) initiated extensive economic, political and social reforms from 1963 with the “ White Revolution ”. With the rising oil revenues, an industrialization program could be launched that turned Iran from a developing country to an up-and-coming industrial country in just a few years. Active and passive women's suffrage was introduced in September 1963. Industrialization and social modernization led from the beginning to tensions with the conservative sections of the Shiite clergy. The Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in particular spoke out against the reform program as early as 1963. In addition to the Islamic opposition, the Fedayeen-e Islam , a left guerrilla movement was formed in Iran that wanted to change the country with "armed struggle". The political liberalization that followed in 1977 enabled the opposition to organize. There were violent demonstrations, murder and arson attacks that shook the country to its foundations. After the Guadeloupe Conference in January 1979, at which French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing , President Jimmy Carter from the United States, Prime Minister James Callaghan from the United Kingdom and Chancellor Helmut Schmidt all decided to stop supporting the Shah and that Mohammad Reza Pahlavi left Iran to seek conversation with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The Islamic revolution had begun.

Islamic Revolution and Republic

On February 1, 1979, Ruhollah Khomeini returned from exile in France; this day has since been celebrated as a national day of remembrance, called Fajr ( dawn ) . He quickly established himself as the highest political authority and began to form an "Islamic Republic" out of the former constitutional monarchy, among other things through the successive and violent elimination of all other revolutionary groups. His policy was shaped by an anti-Western line and did not shy away from terror and mass executions . This led to a break with numerous former supporters - such as his designated successor, Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri .

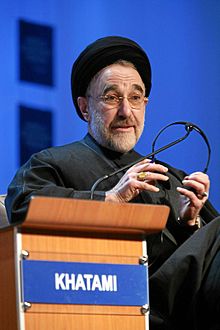

From 1980 to 1988, Iran was in the First Gulf War after Iraq attacked. Iran's ongoing international isolation eased for a time at the end of the 1990s. With Mohammad Chātami's surprising victory in the 1997 presidential election , the political movement of Islamic reformers established itself in the Iranian parliament. Thus, at the beginning of his term in office, Chātami succeeded in pushing through a liberalization of the national press. This gave the voices critical of the system a public organ to emphasize their will to reform.

The rise of freedom of the press did not last very long. The Guardian Council revoked the laws with reference to the incompatibility with Islam and from then on blocked almost all reform attempts by Parliament. Since then, the reformers have been confronted with a major loss of confidence in the population groups willing to reform. The disappointment over the powerlessness of the parliament led to a very low turnout in the local elections in 2003 (national average 36%, in Tehran 25%) and to a clear victory for the conservative forces.

Ahmadinejad's presidency

The presidential election on June 17, 2005 marked a turning point, especially since Chātami was not allowed to run again after two terms. The election of the conservative Mahmud Ahmadineschād as president and his confrontational foreign and repressive domestic policy increased international isolation again. In particular, his re-election in 2009, which was accompanied by numerous allegations of manipulation, led to massive protests in the country, which continued to increase, especially towards the end of 2009, despite the violent crackdown on peaceful demonstrations. In the process, Ahmadinejad , who appears close to the people and distributes subsidies , was also in conflict with even more radical, radical-orthodox religious groups around the influential eschatological clergy Jannati , Yazdi and Ahmad Chatami , who succeeded several times - also with the help of Parliament - as ministers and confidants of Ahmadinejad to force resignation. Other ministers remained in office against the will of the president with the support of radical Orthodox circles, but were unable to dismiss their state secretaries, supported by Ahmadinejad. The clergy accused Ahmadinejad of pursuing a national Islamic course instead of an Islamic course. Students of these Orthodox clergymen ( Haghani school in Qom ) hold numerous key positions in the Iranian military and secret service.

The result of the conflicts were threats against Ahmadine Shad and the radicalization of the judiciary, executive and legislative branches. They asked members of parliament in 2011 the death of the system also true, defeated in the presidential elections in 2009. Opposition candidates Mousavi and Karroubi , both of which were put together with their wives under officially unacknowledged and illegal house arrest, which was most severely criticized. Former President Rafsanjani , loyal to the system , lost his influential position as chairman of the Expert Council to an aged Haghani representative . The confidants and children of the billionaire , formerly known as the " Richelieu of the Iranian Revolution", became the object of bullying, violent Basij-e Mostaz'afin riots on the street.

Another result of this radicalization was increasing international economic and political isolation , as a result of which private assets were frozen and travel bans and further sanctions against numerous high-ranking Iranian military, police, judges and prosecutors, among others. were imposed by the European Community in April 2011.

Rouhani's presidency

On April 11, 2013, Hassan Rouhani , who by Iranian standards is moderate and politically close to former President Rafsanjani, announced his candidacy for the June 2013 presidential election . He stated inter alia. the intention to introduce a civil rights charter, to rebuild the economy and to improve cooperation with the world community, in particular to overcome the isolation of Iran and the sanctions that led to a devastating economic crisis due to the dispute over the Iranian nuclear program . During the election campaign, Rouhani vigorously defended his approach as chief negotiator and insisted in a TV interview that the nuclear program had never been halted even under his leadership of the negotiations, and that the Iranian nuclear program had been successfully expanded. "Prudence and hope" is the motto of the government he wants to form. According to preliminary information from the Interior Ministry, Rouhani won the election in the first round with 18,613,329 votes (50.71%).

Shortly before a visit by Rouhani to the UN General Assembly in New York on September 25, 2013, he and the supreme religious and political leader Ali Khamenei announced that the Iranian Revolutionary Guard , which is closely linked to Ahmadinejad, should stay out of politics in the future. In addition, around a dozen political prisoners were released early on September 18, 2013, including the human rights activist Nasrin Sotudeh . Some observers saw this as Rouhani's first attempt to implement his election promise to allow more political freedoms in Iran in the future, but at the same time as a signal that Iran is hoping to ease relations with Western countries. Indeed, Rouhani managed to open direct talks between the United States and Iran over the nuclear dispute. Others, like Human Rights Watch , welcomed the releases, but saw them as little more than a symbolic gesture, given that hundreds of political prisoners were still in Iranian prisons. The regime must also ensure that those released are not again targeted by the security forces and the judiciary. The Iranian Nobel Peace Prize laureate Shirin Ebadi and Amnesty International also sharply criticized Rouhani's human rights record and the sharp rise in the number of executions.