Prehistoric and early historical terminology and systematics

The prehistoric and early historical terminology and systematics in prehistoric archeology is neither binding nor in use everywhere and with every scientist and in every publication, i.e. relatively inconsistent, but despite all of the unavoidable vagueness and uncertainties in detail, there are some internationally General conventions of terminology as well as the chronological , cultural-historical and archaeological - excavation-technical systematics and periodics developed, including temporally and / or culturally defined sub-systems that further subdivide or replace the large order grids such as the three-period system locally and regionally according to various criteria, where they are not applicable.

Accordingly, the concept of culture in prehistoric archeology, as it is mainly used in the German-speaking area, is first described as a higher-level aspect. This is followed by a detailed presentation of the terminology and system structure of prehistoric chronology and periodics. Find and finding systematics and the archaeological classification principles derived from them as well as the tool classification and its various systems are a further focus. A detailed overview of the non-European periodicals and classifications, which cannot be represented or can only be represented with great difficulty within the framework of the three-period system, forms the conclusion.

The concept of culture in prehistory

term

The term culture was finally established in its current meaning by Johann Gottfried Herder at the beginning of the 19th century and defined as a regionally and temporally delimitable state of societies. According to the definition of the Encyclopædia Britannica , culture is an “integrative pattern of human knowledge, belief and behavior. Seen in this way, culture consists of language, ideas, beliefs, customs, taboos, codes, institutions, tools, techniques, works of art, rituals, ceremonies and other related elements. The development of culture depends on people's ability to learn and their ability to pass on knowledge to subsequent generations. ”So this is the multifactorial concept of culture that is used in classical historical research as a regional and temporal unit of interpretation of this and others, for example economic, political and social Aspects is used. In prehistoric times, however, as they can reconstruct the archaeologist, missing almost all of these intangible aspects as they adduced no concrete evidence at best now and then on the basis of sensitive ethnological parallels analogistisch can be concluded scientifically highly controversial procedure.

Problem

The term culture can therefore only be used in the prehistory and partly also in early history, but especially in the Palaeolithic and Middle Stone Age , due to the available evidence, only in the sense of “ material culture ”. Only this is known through tools and other preserved artifacts, and even this only in unrepresentative excerpts, in which the upper class is mostly overrepresented, especially in the late Neolithic and early history. Only rarely such as B. with cave paintings such as the Franco-Cantabrian cave art or the Urals , the rock art of the Sahara , Namibia or Australia, sculptures such as the Venus figurines or the isolated paleolithic burials (e.g. Shanidar cave, La Ferrassie , Monte Circeo , Sungir , Unterwisternitz , Prednost , Ofnethöhle , etc.), statements that go beyond this have been preserved, in which the modern concept of art can only be used in a greatly expanded sense. Conclusions on immaterial culture, for example on religion in the Paleolithic and shamanism, can therefore only be made very cautiously; and it is here that the scientific controversies are particularly pronounced. In addition, the interpretation of such evidence and finds depends in particular on the archaeologist's private, scientific or socially pre-formed ideas about the society in question. The excavation and exploration methods used in each case are also an essential factor, as archeology used to concentrate more on monumental buildings or richly furnished graves. Concepts of the history of the humanities and the history of science and “superstructures”, such as those represented by cultural studies , cultural anthropology or ethno-archeology, are of particular importance, with the latter in particular holding numerous interpretive pitfalls through pseudo-ethnic parallelism and delicate analogies. Tomáš Sedláček has recently investigated the economic and social aspect of culture and civilization, which he treats both as equal terms, for prehistoric processes, among other things.

Cultural anthropology, on the other hand, has been shaped by particularly virulent ideas of development, especially since the 19th century when it emerged, especially after Charles Darwin and in the political and economic environment of European imperialism. The result of such thoughts were so-called "stages of culture". The ethnologist Wolfgang Marschall writes in the introduction to the anthology he edited : Classics of Cultural Anthropology “The fact that archeology in the 19th century made it possible to construct a chronology and development history from the succession of different object forms in the excavation layers strengthened the development-historical thinking of that century . ”But this was already present as a tendency in the history of ideas, like the famous academic inaugural speech given in 1789 by Friedrich Schiller's What is meant by and at what end does one study universal history? clearly show, in which, among other things, there is talk of peoples who are located around us at various levels of education “how children of different ages stand around an adult and, through their example, remind him of what he was and what he was went out ”, crude tribes that a wise hand had saved for us for the time“ where we would have advanced far enough in our own culture to make a useful application of this discovery to ourselves and the lost beginning of our generation to this To restore mirrors. "

In prehistoric contexts, the term “culture” can therefore at best be used as a popularizing designation for complexes of finds and it is best to avoid it, especially if one takes as a basis the definition of the Brockhaus encyclopedia that “this cultural term is not just what is made and produced and artificial, but also addresses the moral good of the culture ”. Since the concept of culture has its own definitions in anthropology , social psychology and ethnology , it does not have the prerequisites necessary for precise delimitations in purely archaeological contexts. In addition, because of their conservation potential, find inventories represent a substantial part, but by no means the only or even representative state of cultures, including those of the Paleolithic.

In German, where the term culture is still often and more traditionally used to designate techno complexes, there is also the fact that it is particularly charged in terms of intellectual history and is used differently than is customary internationally, namely as a superordinate, positive term, while in other languages, especially in English and French, "civilization", a term with a rather negative connotation in German, is either used equally, but rather as the overarching term and culture denotes a specific, regional or temporal subordination of it.

Possible application

The very large periods of the three- period system such as the Old, Middle and Neolithic and their subdivisions as well as the Early, Middle or Later Stone Age etc. in Africa were always too inconsistent and the knowledge about them is still too sketchy to be labeled as a culture . They are therefore neutral and because of their purely temporal conception, they are considered “periods” (hence the three “period” system). In the past, however, a larger, supraregional complex within these periods with a very long duration, such as the Acheuléen or Moustérien, was often referred to as “culture” under the restriction of purely material culture mentioned above, even if there were potentially complementary phenomena such as “early art”. There is also the term archaeological culture , which is, however, not undisputed in science. In the meantime, “Technokomplex” is usually used for such large periods and these are divided into “Industries”. If one refers primarily to the tools of individual sites, one says "inventory" (see find complexes according to John Desmond Clark ), whereby there are systemically different weightings and relationships between these three basic terms, especially in the archaeological context.

The concept of culture in prehistoric archeology can therefore at best be used in a practical and value-neutral manner without reference to intellectual history, as is the case in particular in Anglo-Saxon research. Andrew Sherratt writes in his Cambridge Encyclopedia of Archeology : “In the preliminary ordering of his material, the archaeologist finds it useful to define certain 'cultures'; these are constantly occurring groups of simultaneous find types in a limited area. They form a frame of reference for the interpretation of changes in living conditions resulting from buildings, artifacts and food residues, such as B. animal bones, mussels, shells, seeds and other organic remains. ”However, John Desmond Clark , one of the most important experts of the 20th century on the prehistory of Africa, rejected the use of the term“ culture ”in prehistoric contexts and consistently replaced it with "Technokomplex". Wherever “culture” could not be avoided, he usually put the word between quotation marks.

In the Neolithic, on the other hand, the use of the concept of culture can make sense with restrictions because of the fact that the finds can now be recorded in much more detail, provided that some of its basic conditions, as they are assumed quasi axiomatically in the highly cultural phases determined by the presence of a script (i.e. art, state, economic and social complexity of the organization, coherent and differentiated worldview, etc.), and above all aims at the internal uniformity and its good delimitation from neighboring complexes of these "early cultures", as happens similarly with the term "primitive culture".

Terminology and system structure of chronology and periodic

Chronology and periodic always imply a certain, archaeologically defined concept of time that is in no way identical with the scientific one. Time is not experienced as such indirectly and individually or through time measurement systems, but directly and objectively as a morphological phenomenon of material representations. You alone are witnesses to a certain time. These include excavation finds such as tools, ceramics, weapons, remains of settlements, etc., all of which have always preserved a certain point in time, in these cases the time of their creation and use. This has considerable effects on archaeologically understood time sequences, which can be defined as relative and absolute , depending on whether there is a sequence that cannot be precisely fixed in time, such as that offered by stratigraphy , or fixed points in time can be determined, such as those provided by physical methods. The presentation of this section begins with the most general terms, characteristics, criteria and systematics of the prehistoric and early historical systematics and then descends and expands to the more and more specific substructures of systematics and terminology.

Historical-systematic basic concepts

Prehistory and prehistory

The still occurring naming the unwritten history in Germany as Prehistory deviates greatly from the international usage where pre history (Prehistory, Prehistory, Prehistoria etc.) or German ago is history consistently usual. The dtv dictionary of synonyms from 1999 lists “prehistory” only as a peripheral term to “prehistory”. The Duden dictionary of synonyms from 2007 does not even have “prehistory” as a lemma, but also only lists it as a subordinate variant of “prehistory”. The German dictionary vol. 3 of the Brockhaus encyclopedia (vol. 28) from 1995 lists "prehistory" only briefly (p. 3608), but "prehistory" in much more detail (p. 3791: 17 lines to 4 lines). The actual Brockhaus encyclopedia also lists “prehistory” only with an arrow pointing to “prehistory”, which takes up over one page there (vol. 23, p. 448 ff.). Nevertheless, in Germany, for example, the names of the relevant seminars and institutes at universities have been inconsistent to this day, mostly for historical reasons, despite increasing alignment with international usage.

In terms of linguistic history, “prehistory” is an analogy based on older words such as prehistory, origin, cause, author , which is likely to have its formative roots in the 18th and 19th centuries in the wake of the Baroque era . The further development then leads through idealism , the Weimar Classic and Romanticism in Germany.

The Grimmsche German Dictionary (DWB) records “prehistory” in today's sense of a prehistoric epoch designation as a new formation of the early 19th century, which, like “prehistory”, was first recorded in Joachim Heinrich Campe's “Dictionary of the German Language” (1807-1812). Zedler's Universal Lexikon , published between 1732 and 1754 and with 64 volumes the most extensive encyclopedia in Europe in the 18th century, does not use the keyword “prehistory” or the keyword “prehistory” - a sign that the concept had not yet begun. It only began with the increasing interest in the past at the beginning of the 19th century, as the history of historical studies shows, which now broke away from the classical antiquity that had existed since the Renaissance and its sole orientation to Greco-Roman antiquity.

The term “prehistory” is also mentioned in the DWB, which appeared between 1854 and 1971, so that there was initially competition between two terms, which was then apparently dissolved in favor of prehistory in the course of German Romanticism. The use of pre-history, on the other hand, is controversial, especially among prehistorians, as it would place this longest part of human history outside the historical framework.

Delimitation: prehistory - early history - history

This threefolding is not to be confused with the three-period system . Rather, it almost exclusively relates to the absence or presence of written sources, so it is much more culture-specific than this. Technological phenomena such as tool manufacture and its materials, as they are the basis of the three-period system, do not play a role in this classification. The same applies to other cultural expressions such as economy, art, religion, way of life, etc.

prehistory

The prehistory describes the history of people from the beginning to the onset of clearly identifiable written sources that are at least partially understandable in terms of content. The tribal history of humans is usually also included in order to identify the bearers of the respective phases, which belonged to several homo types from Homo habilis , Homo erectus to Neanderthals to anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens ), especially since one belonged to them found bony remains, albeit very rarely, along with tool inventories.

The prehistory (or prehistory) ends quite differently around the world and is still present today in some regions of the world where peoples without writers live (e.g. Sub-Saharan Africa, Amazonia, Australia, Oceania, South and North Asia, etc.). There are therefore only archaeologically obtained evidence in the sense of artefacts that lead to findings as finds . The very rare anthropological finds, i.e. bones, only play an accompanying role here when one tries to identify the carriers of a techno complex. However, they are of the greatest interest to paleoanthropologists who, however, do not deal with the prehistory of humans, but with their tribal history, which goes back much further, and for whom prehistoric archeological finds are merely accompanying finds .

If you leave aside the purely evolutionary-biological relevant pliocene phase of the hominid - pre -humans of the Australopithecus type from 5 million BP and the even older Miocene phase of the animal-human transition field (8 to 5 million BP) before that, this prehistory , which began with the Pleistocene , almost covers 99 , 9% of the total human history and begins with Homo rudolfensis and Homo habilis and their first verifiable stone tool production in Africa, which starts from about 2.5 million years BP . (The much older osteodontokeratic culture of the australopithecines postulated by Raymond Dart , which would have put the beginning of prehistory far back, has now been refuted.)

In this narrower sense, which is the only relevant one here, prehistory includes the entire Old , Middle and New Stone Ages and mostly also the Bronze Age . Exceptions are the early high cultures , such as ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia , where there are already sufficiently valid written documents. The early (pre-Roman) Iron Age , the so-called Hallstatt and La Tène times (named after their eponymous sites ), such as the Celts , Teutons and Slavs , the Thracians , Illyrians and Dacians of Europe and the early cultures of the Aegean , mostly still belong to this framework, even if here occasionally, however, mostly fabulous descriptions by Greek historians such as Herodotus , Polybios , Aristotle and Poseidonios are present, so that in these so-called "barbaric fringes of the later Greco-Roman world" with the proto-historical peoples of Europe there is already an early history There is a transitional situation in which these cultures do not have their own script, but external authors from other cultures report on them. The unscripted peoples of Sub-Saharan Africa and other indigenous peoples in South America, South Asia, Australia, New Guinea, New Zealand and Oceania also clearly belong to prehistory, and in some cases to this day .

The scientific structure of prehistory follows the climatic periodization of the Quaternary , extends over the entire Pleistocene and, depending on the region, 70 to 100% (i.e. until today) of the subsequent Holocene and is subdivided on the basis of find inventories, so-called techno complexes and their substructures Temporal-cultural delimitations in the tabular overviews of the three-period system are only shown very summarily, but were actually connected or influenced by more or less short phases of transition and by overlapping.

The term prehistoric times , on the other hand, should not be used in scientifically determined prehistoric and early historical contexts, since it is unspecific or diffuse in time and has the meaning "up to the very first beginnings, an infinitely long time ago" etc. The term is often used in poetic (e.g. Goethe, Schiller, Herder, A. v. Arnim, Platen) and even mythical contexts. In principle, however, it goes back through palaeontological and geological content and even includes cosmological areas (e.g. Big Bang ). The evolutionary history of humans or even their prehistory from 2.5 million BP are only the marginal end point here (approx. 2/10 per thousand of the total period of 13 billion years).

Early history

The history of writing , which marks the beginning of the prehistoric period, according to current opinion, began around 5000 years ago, but according to Harald Haarmann's relatively controversial view, it even began with sacred writing in ancient Europe from around 5300 to around 3500 BC. BC, initially in the Vinča culture , which was then followed by the development of writing in the Minoan culture of ancient Crete, which can possibly be associated with it. It is uncertain to what extent such pictographic symbols, which were already postulated by André Leroi-Gourhan and Julien Ries as so-called mythograms for the Franco-Cantabrian cave art of the Upper Palaeolithic , can already be described as writing in the sense of a universally usable, flexible information carrier. The classification of prehistoric cultures, especially their beginnings, is correspondingly uncertain.

Early history is thus a transition phase, which is sometimes difficult to define precisely, between prehistory without writing and written history, mainly history documented in writing or by external reporters. The existence of a script alone does not necessarily mean that one can talk about history, as the example of the very esoteric-religious runic script shows, which was a priestly secret script with a magical function.

Sources: In addition to archaeological finds, other sources are also available in prehistoric periods, although these are not sufficient for a halfway conclusive overall historical picture. Such sources are above all with regard to the proto-linguistic so-called "barbaric fringe peoples" of classical antiquity:

- Sporadic written documents such as inscriptions. Their informational value is low, as they mostly only contain names of persons, gods and places and occasionally not always clear time information. You form z. B. With the Etruscans the main mass of the traditions and can be read only with difficulty because of their comparatively small amount. Sometimes it was even not clear for a long time, as in the case of the Maya pictorial writing, that it was actually a question of writing and not just decoration.

- Linguistic monuments such as names of places, waters and fields and native animal and plant names. They prove relationships between ethnic groups, as investigated by Indo-European Studies, for example , by determining the substrates of other languages and their origins and drawing conclusions about the whereabouts of the individual ethnic groups. The name “Berlin”, for example, comes from an Old Slavic waters name, many German river names such as Neckar or Main are of Celtic origin, Old Indian Sanskrit is an Indo-European language ( Kentum and Satem languages ), the majority of the Sub-Saharan languages belong to the Bantu languages and testify to the expansion the Bantus to the south, etc.

- Administrative documents of the dominant, here usually Roman, and formerly also Greek, Mesopotamian and Egyptian institutions, i.e. military and provincial administrations. Their value is limited, as ethnic units, for example, are distorted and simplified. In addition, only longer representations, such as B. Caesar, more telling.

- Commercial documents from merchants can provide further information about goods and trade routes, trading stations, local needs and values, etc., including additional information about the country and people that interest a merchant. In fact, it was even the Phoenician merchant people , who did not even develop their own state, only maintained large trading cities, such as Byblos or Carthage, who developed the first usable, still purely consonantic cursive script from older pictorial and syllabary scripts, which then developed over the Greek and Latin all later European scripts were based. Even the runes could possibly go back to it via the Etruscan alphabet derived from the Greek.

- Oral folk-language traditions fixed in writing. The old Germanic ( Hildebrandslied etc.) or Greek epics, such as the Homers , are cases that have no direct historical information value, but convey spiritual and religious attitudes and thus usually very long-term traditions of individual peoples as well as reports about local, often mythical or heroically colored events. The fact that they can still be of archaeological relevance is paradigmatically shown, among other cases, by Heinrich Schliemann's discovery of Troy .

- Ancient reports on the non-scripted cultures of Europe , i.e. descriptions of Herodotus , which are based on observations by their authors themselves or on reports from sources, but are often fantastically distorted and are also very limited in their perspective. It reports deliberately or casually about encounters with “barbarians” and their customs. They are very limited in their perspective, mostly related to the ruling classes, priests and warriors, and more precise information about the social structure can only be obtained from longer ethnographic works or long descriptions of the history, such as those of Caesar or Tacitus, whereby such descriptions are often very one-sided, are politically and militarily oriented and sometimes contradict each other from author to author. In addition, they hardly provide any information about social changes.

In addition, the archaeological finds continue to exist and are still far more important , i.e. buildings, waste, equipment, ceramics, graves or coins as well as bony remains of animals, plant remains (e.g. pollen, seeds, fibers, etc.) and the like. Language and written sources are to be evaluated using the means of language research, material finds are archaeological.

Legibility: Sometimes the situation arises that a script is verifiable but not translatable (e.g. the Cretan script Linear A or the Rongorongo script from Easter Island ). In practice, in such cases one is then dependent on archaeological means, although the cultural evidence is prehistoric, and with rich written material could even be considered historical. The Meso and South American civilizations were such cases long until the Mayan script was translated . It is questionable whether the Quipu , the knot script of the Incas used primarily as a mnemonic technique , can be regarded as sufficient to view the culture as historical for that reason alone. However, there are enough other features here (buildings, secondary reports from the Spaniards, etc.) that nevertheless allow the classification as high culture . This also applies to the culture of the Etruscans, whose script is now generally legible, but the source material is too poor to be able to gain further historical information from it.

In the Mediterranean area, the recorded early history begins first. In Central Europe it started around the time of Julius Caesar in the middle of the 1st century BC, when Roman authors began to describe the cultures there in more detail (even if with a not inconsiderable Roman cultural arrogance, wrong classification and above all with non-ethnological motives for the writing of the scriptures must be expected, quite similar, albeit for different reasons, as with the description of the Etruscans ). For Northern Europe, however, early history begins later.

history

Overall, the concept of history is extremely complex and often philosophical and theoretical. For historical studies , however, it initially only refers to the period of history in which there are so many written evidence locally, regionally and ethnically that the evaluation of a political-social network of relationships between people in all their temporal relationships is possible according to historically halfway verifiable criteria. without having to rely exclusively or predominantly on archaeological finds, which nevertheless still play an important role, but above all in the evaluation of individual questions and phenomena, but no more or less for the overall picture. The métier of historiography developed early on, for example in the old advanced cultures, from which modern history ultimately emerged.

However, this is no longer limited to the presentation of the epochs documented by written evidence, but reaches far deeper into prehistory, in which case an attempt is made to combine the findings of prehistoric archaeologists with those of paleoanthropologists, zoologists and climatologists and botanists, geologists, religious scholars, etc. to form a relatively coherent overall picture, which, however, cannot be called historical in the narrower sense of the word, since certain chronologies can only be roughly and roughly represented, rather should be understood as an attempt, “the prehistory to be understood as a coherent overall phenomenon ”. The Encyclopædia Britannica does not even define “History” as a period, but as “the discipline that studies the chronological record of events (as affecting a nation or people), based on a critical examination of source materials and usually presenting an examination of their causes ", Ie exclusively as a historical science , and" Prehistory "does not appear as a lemma, nor does" Early history ". The main article History deals accordingly only with "The Study of History", but then on 70 closely printed pages. There is only one sparse definition, namely: "the events and actions that together make up the human past" and "the accounts given of that past and the modes of investigation whereby they are arrived at or constructed."

A further phase within this series, which is located within written history, can be described as the advanced civilization , which, as in the case of the ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern, but also early Chinese and ancient American advanced cultures, can actually even show characteristics of prehistory, even Neolithic to Early Bronze Age .

Major periods and their substructuring

The three period system

Thomsen's three-period system is a purely archaeological, non-cultural-typological model (of which there are a number of others, structured according to different aspects such as social, economic, religious etc.) on the simple material differentiation basis of stone, copper, bronze and iron purely chronologically and sequentially does not contain any regional components or variants or overlaps, so extremely simplified.

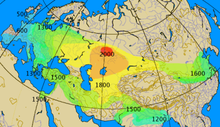

Applicability: As the three-period system of prehistoric and early historical archeology developed and established in the first half of the 19th century by the Danish archaeologist Christian Jürgensen Thomsen and others, later refined after the development of better dating options and excavation and exploration techniques as well as the increasing number of archaeological finds was, this was done primarily on the basis of European and circum-Mediterranean prehistory and early history. Nevertheless, it can still be used to this day in Europe and large parts of Asia, especially in the Middle East and each with some regional restrictions, where isolated groups such as the Adivasi of India, some ethnic groups of Central Asia or the Ainu of northern Japan, culturally from individual cultural phases were not reached in Central , South and East Asia , but not or only to a very limited extent in the Malay Archipelago and in North Asia (e.g. the peoples of Siberia ). This also applies to isolated ethnic groups in Northern Europe such as the Sami . (The non-European periodic not covered by the three-period system is shown in an overview at the end of the article.)

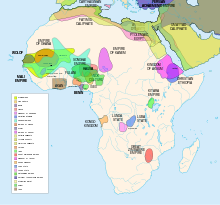

However, it is largely useless for the area of the two Americas, including the high cultures there (only the Andean peoples such as the Mochica and Incas developed or mastered bronze casting and could therefore be subsumed under the three-period system), as well as for Australia and Oceania . The same applies to Sub-Saharan Africa , as there was no Bronze Age anywhere and in large parts not even a Neolithic Age (e.g. the San or Pygmies ), but a direct transition from the Stone Age to the Iron Age, either during the so-called. Bantu expansion or even later by the Arab and European conquerors and colonial powers, the latter with a focus in the 19th century, when colonialism passed into imperialism and cultural imperialism .

Classification principle: The three-period system divides the prehistoric and early historical epochs and rooms into roughly the Stone Age , Bronze Age and Iron Age according to the materials mainly used in tool and weapon manufacture . It then subdivides these further into various sub-epochs such as the Paleolithic or the Old Paleolithic ( hunters and gatherers ), the Middle Paleolithic (technically highly improved devices also made of bones: the so-called Moustérien ) and the Mesolithic (transition to the Neolithic, which, however, can only be ascertained in Europe ) and Neolithic or Neolithic (agriculture, domestications and ceramics as well as stone grinding and stone drilling). These subdivisions are then in turn further subdivided relatively chronologically on the basis of tool development and related cultural factors and, in the Neolithic, also economic factors. This results in sub-categories with the phases old or early , medium , young and, if necessary, late , end and epic , which, however, now appear very differently locally and temporally.

Transition periods: The three-period system also only marginally, undifferentiated or not at all contains the most important transition phases, which often have different names and occur in different regions. They are:

- The Middle Stone Age (Mesolithic), a term limited to Europe north of the Alps, which occurs in the Mediterranean as the Epipalaeolithic and represents the link between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The periodization is based on the geological-climatological incision formed by the end of the Würm Ice Age and the beginning of the Holocene ; to the front it is delimited in terms of cultural history and economics by the transition to the rural economy of the Neolithic Revolution .

- The Pre-Ceramic Neolithic , also called Akeramikum or PPN (Pre Pottery Neolithic), which is chronologically divided into three phases PPNA , PPNB , PPNC (Transition to Ceramic), and in this terminology is not included in the three-period system, but is largely identical to the European Mesolithic . It occurs in the Eastern Mediterranean and adjacent areas, especially in the earliest settlements such as Jericho (PPNA), Nevalı Çori (PPNB), Ain Ghazal (PPNB) and Göbekli Tepe (PPNA and B) and continues with the already sedentary culture of the Natufia as the earliest, still epipalaeolithic stage, which in the Middle East, and only there, formed a hunter-farmer transition stage.

- The Chalcolithic or the Copper Stone Age in the late Neolithic as a link to the early Bronze Age with the beginnings of metalworking, which in its earliest stage is sometimes also referred to as the Eneolithic . It is proven above all in Central and Eastern Europe, in the Middle East , but also in South America in the Moche culture . The glacier man Ötzi belonged to this phase, because he carried an ax made of almost pure copper with him (it was traded and therefore probably intended for use), a valuable commodity, as we know from other contemporary finds, where there are often regular depots with copper axes and devices were found.

- The early history as a link and transition stage between illiterate Prehistory and writing attested history. With the onset of early history, which is no longer recorded by him, the three-period system closes ( see above and below ).

Transition from the three-period system to regionally and culturally defined units

Paleolithic substructuring

The other, no longer necessarily relative-chronological and sometimes overlapping in time and region, are usually subdivided into techno complexes such as Acheuléen , Moustérien , Levallois, such as Acheuléen , Moustérien , and Levallois, which are usually the first locations, especially France, not necessarily the most important ones) , Aurignacien , Magdalenian and their potential sub-epochs (again with early, middle, late, etc.) are no longer explicitly part of the materially defined, but basically purely temporally structured three-period system, but expand regionally, sometimes strongly fanning out downwards smaller subgroups or “cultural units”, even if they are limited in time by the three-period structure. The decisive factors for this subdivision are regional, sometimes partially and locally overlapping techno complexes, industries and inventories. Occasionally, cultural phenomena, which are usually very difficult to date, can also be used for the substructuring. In Europe, for example, this is the Franko-Cantabrian cave art of the Upper Paleolithic ; in North Africa it is the Holocene rock art of the Sahara with their mainly content-based time stages (see Africa ), which are still paleolithic in their first phase (they are in the last phase Iron Age and Early History). There are also similar rock art sequences for Namibia , which are very difficult to organize chronologically. They belong to the Bushman culture, so in terms of content they belong to a pure hunter-gatherer culture. The same applies to other rock art regions such as that of the Aborigines of Australia, some of which were still alive well into our time.

Neolithic substructuring

Particularly in the Neolithic, which is archaeologically much better than the Paleolithic, such subperiods can then be further subdivided and, above all, regionalized, because there are now permanent settlements here that are much more meaningful and rich in findings than the temporary camps of the Paleolithic (with the exception of the Upper Paleolithic caves ). The use of the term “culture” is now more appropriate (sometimes also neutral “group”), since one knows a lot more about the individual groups and their social and economic structures, for example through dwellings and their facilities, mine finds, characteristic ones Ceramics, domestic animals, means of transport, commercial goods or large equipment such as plows and means of transport such as wagons and boats as well as the weapons and protective devices that are now increasingly appearing (such as palisades); and burials sometimes also give us more information about intangible cultural features such as belief. These groups, which can often be distinguished by individual ceramic styles, are correspondingly easier to grasp, so that in some cases an individual cultural image, even if it is still coarse, can be created, a development that was massively strengthened in the Bronze Age and also led to increasingly differentiated ideas of culture archaeologically and society leads.

In some places where such differentiations are possible due to the location of the finds, the European Neolithic is divided into an Early Neolithic with the Lower Epochs Old and Middle , and a Late Neolithic with the Lower Epochs Young and End .

These in turn each comprise individual cultural groups, which are then usually named according to certain criteria, which either designate local communities that can be easily distinguished from neighboring groups or are based on cultural phenomena that now dominate in individual groups, connect them with one another or separate them from one another and archaeologically so can be easily described that they impress as cultures:

- Groups or “cultures” named after places such as Michelsberg , Aichbühl , Rössen , Schussenried , Ertebølle , Bromme etc.;

- According to certain characteristics such as ceramic line tape - Stroked - and Corded Ware , Beaker , Beaker , Globular Amphora ,

- According to burial and other religious customs such as individual graves , urn fields , tumuli , megalithic culture , etc.

- According to certain tool and weapon characteristics such as battle ax and boat ax , dagger time .

However, the Neolithic phases and individual cultures are by no means coincident even within Europe. Rather, they form regional units that can be shifted from one another, whereby the individual cultures do not appear everywhere, as the following table shows paradigmatically for Germany and southern Scandinavia. The Neolithic periodization in Eastern, Southern and Northern Europe deviates even more strongly from east to west and from south to north in accordance with the spread of Neolithic technology.

Early history - historical transition

These names, which were still prehistorically oriented, based solely on archaeologically determined criteria, then passed into cultural names of peoples, i.e. Celts , Teutons , Scythians , Iberians , Italians , Illyrians , etc., which are now increasingly more precisely comprehensible as ethnic-cultural units, before the Iron Age especially through the reports of ancient authors or geographers about them, who were usually also the originators of the names of peoples, which they either adopted directly from the peoples and sometimes incorrectly or inadmissibly generalizing or assigned to them self-educated (the Celts and Germanic peoples are such a case, in which heterogeneous groups were artificially combined to form a non-existent “total population”).

In the ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern high cultures, especially the Egyptians, Sumerians , Babylonians , Persians , Hittites , etc., one can first find a differentiation according to local or urban cultures from the late Neolithic to the early Bronze Age such as Jericho , Hattuša , Çatalhöyük , Ur , Lagasch , Abydos , Byblos , etc., which later sometimes led to historically documented empire formations or were absorbed by them, provided that they did not simply perish with the Indus culture, like the north-west Indian Harappa . Or, as in ancient Greece, politically large-scale city-states or local cultures such as the Mycenaean culture on the Greek mainland or the Minoan culture of Crete emerged. Typical of this period are above all Neolithic to Bronze Age river cultures, which can be precursors to later great empires, for example on the Yangtze , Mekong , Nile, Euphrates and Tigris, even if the development is not always so direct, for example on the Mississippi , the Danube or the Indus passed. Later empires also emerged on the coasts or near the coast, such as the Etruscan cities of the League of Twelve Cities or Phoenician foundations such as Carthage . Even Troy falls into this still pre- to early historically defined set, although it here probably close links with the Luwians are missing and later regional governmental development similar to the case of Carthage.

Other chronological terms used in prehistoric archeology

In principle, one differentiates today in relative chronology the following time units in descending order:

- Epochs (so-called ages) such as Paleolithic, Bronze Age, etc.

- Periods such as Middle Paleolithic, Older Iron Age etc.

- Levels like Bronze Age A, Latène B

- Phases, e.g. B. Hallstatt A1, Latène D2

- Sub- or sub-phases, e.g. B. Bronze Age A2a, Latène D1a.

In addition, local specifications such as Nordic Iron Age, penknife group, etc.

Fund horizon, cultural layer

The terms come from the excavation-technical stratigraphy and further subdivide individual inventories, whereby the find horizon refers to a certain find layer , also known as a cultural layer, initially in the context of a relative chronology with regard to underlying, i.e. older find layers and above, i.e. younger (at undisturbed find situation, so-called in-situ situation). Several such layers or settlement layers, initially always geostratigraphically from top to bottom in the order of exposure (you can't know from the beginning how many there will be) then form a stratigraphic and chronological sequence. Not to be confused with this is the cultural-historical sequence that was determined secondary after the excavation, in which the lowest, oldest cultural layer then receives the Roman numeral I, the overlying II, etc., which are then classified as a, b, c, etc. in lower layers can be broken down, such as B. in Troy with 10 main and over 40 lower layers or in the Franco-Cantabrian caves (the Isturitz cave was occupied for between 90,000 and 10,000 BP over and over again). The stratigraphy of self-contained gates, for example in garbage pits, can also be called this because the bottom layer can quickly be seen in the gate.

Since three-dimensional excavations have long been used nowadays , this alone allows important statements to be made about individual finds and their relationships with one another in the same horizon. If you are lucky and find charcoal , for example as the remainder of a fireplace or in caves of paint residues or even if rarely and mostly only in damp settlements , other organic residues, then an absolute dating of this layer is even possible with the help of the radiocarbon method (if it is still is in the measuring range of the RC method of a maximum of 50,000 years).

Level and group

From such a local fund horizon, including several successive ones that have typical leading forms in common, a level or cultural level can then sometimes be derived that is related to a higher-level industry or a technology complex or a large group or local group, e.g. B. the Ahrensberger stage as part of the stem tip group (more precisely: stem tip industry) or the three local subgroups of the Federmesser group , which in turn are both late subgroups of the late Paleolithic-early Mesolithic techno complex. This is particularly interesting when a sequence is found at the same site, as is not uncommon especially in caves or abrises , that spans a very long period of time with different stages and different leading forms, around 250,000 years on the Kalambo Falls in southeastern Central Africa . The sequence of layers of the Olduvai Gorge even offers a time panorama that extends over 1.9 million years, in whose 100 m thick layer sequence between Bed I to Bed V the human evolution from Australopithecus to Homo erectus and Homo sapiens can also be followed the tool development between early and developed Olduwan (Bed I and II), early and late Acheuléen (Bed III and IV) and Late Stone Age (Bed V).

Linguistic variants and abbreviations

Linguistic variants of the terminology

As far as the English or French language form of the specific archaeologically defined complexes, industries or inventories is concerned, i.e. Acheuléen or Acheulean, the French form is preferred for the complexes or industries etc. named after French or other European places and geological-paleontological models -en / -ien (except of course in the English-speaking countries), otherwise the English-language derivatives are more in use internationally . Especially in the case of the major periods, the supplementary complex, -industry, -inventory etc. is missing in technical terms, and the endings ien / -en / -an / -ian , for example in Olduwan, Acheuléen, Micoquien , Sangoan , appear in abbreviation , Lupemban . In the scientific literature, local inventories are sometimes also abbreviated in this way, i.e. Debban, Shamarkhian, Fayyumian, Ténéréan, Silsilian etc. (also to avoid the often controversial or unclear definition of “complex / industry / inventory”). However, in German the derivation on -ien sometimes sounds a bit cumbersome or strange, so that in such cases one occasionally uses one instead of e.g. B. Hamburgien (so for example) says Hamburg culture. On the other hand, Pavlovien , a Moravian-Austrian variant of Gravettien , is quite common. However, it is recommended to say “group” instead of Ahrensburg culture neutral Ahrensburg level or better still after the tool type handle tip group. However, Fiedler explicitly recommends the use of “Technokomplex” and “Industry”.

Abbreviations of the prehistoric and early historical chronology

- v. BC, BC: The indication "before the birth of Christ" (in English publications BC) is usually limited to the Neolithic and later, since it is used with dates such as 1.5 million years BC. Is more or less pointless and suggests a false accuracy. Also for the Mesolithic the time is v. It makes sense and is customary because after the end of the Ice Age in Central Europe in the Holocene the period between 8000 and 4000 BC. BCE covered and regionally different, often flows relatively early into the Neolithic. Phillipson, Cunliffe and Clark do the same; other authors, e.g. B. the Australian archaeologist Graham Connah, even in historical times (such as Ancient Egypt) consistently use the phrase "... years ago" (ie BP, but with the reference year 1950) and completely avoid the Christian era. On the other hand, one can sometimes find the indication “v. Chr. ”Even for the Middle Paleolithic and even more frequently for the Upper Paleolithic . This has the advantage that, especially in encyclopedic overviews, there are no too large breaks in the time information, but in both cases the old Paleolithic information “v. h. ”or“ ... millions of years ago ”, so that the chronological break between the Old and Middle Paleolithic or the Middle and Upper Paleolithic takes place here.

- BP, vh: Vorneo- or pre-Mesolithic times are therefore indicated with the abbreviation “BP” ( Before Present ) or “v. h. ”(before today), which is calculated back from the base year 1950 (out of consideration for the correspondingly correlated radiocarbon dating = RC dating ) and thus indicates approx. 2000 years more than“ v. Chr. “The times are sometimes abbreviated as TJ in graphics and tables or in English publications with kY (thousand years or kilo years) (ie 80 TJ / kY = 80,000 years).

- BCE, vu Z., vd Z .: The religiously neutral abbreviation BCE (or CE) with the meaning “Before Common Era” and “Common Era” (before / after the Christian era) is particularly common in the Anglo-Saxon language area . It corresponds to the German-language abbreviation vu Z. (before our era) that was widespread in the GDR . In France the following applies to “before the birth of Christ”: “avant / après notre ère” (ANE), “Avant Jesus-Christ” (Av. JC.). “L'ère commune” (ÈC) is also common. The Islamic time calculation AH for Anno Hegirae , on the other hand, cannot be used for scientific and other secular purposes, since it is based on the lunar year (this is eleven days shorter than the solar year ) and is not corrected by switching elements. In Judaism , the designation vd Z. (before the era = BC) or n. Z. (new era = AD) is common. The religious Jewish calendar , on the other hand, like the Islamic calendar, is not suitable for secular purposes, although its lunar year cycle is adjusted at intervals to the solar year by a leap month Adar II . It also begins in 2012 AD 5772 years ago, i.e. in the early Neolithic. Similar objections apply to other historical calendars (even the extremely accurate Mayan one ).

- EU standard: The binding date standard (EN 28601) has not yet been used in archeology. It is based on the Christian calendar, but works without further abbreviations with positive and negative signs and calculates the year zero , which was not known when the Christian calendar was established, so that the post-Christian calendar begins with +1, the pre-Christian one with −1, whereby a year between +1 and −1 is not calculated. So 20 BC is Chr. (Old) = −19; 2000 AD (old), however, remains +2000.

- RC: This is the name given to radiocarbon dating . Does it contain the additional designation cal / BCE, cal./BC or kalib. v. It is converted ( calibrated ) to calendar years (solar years ).

Find system

Main categories of prehistoric sources according to Manfred K. H. Eggert

The principle of the closed find has meanwhile become one of the fundamental premises in excavations and their evaluation. It means that at least two objects must have a simultaneity, i.e. either deposited in a burial or similar or clearly related to one another in buildings.

Nine main categories are distinguished for prehistoric and early historical finds :

- Individual finds : They are particularly difficult to classify as surface and scattered finds , as they mostly occur in the Paleolithic, and can hardly or only very roughly be dated. In addition, the circumstances of the find are often unclear. Archaeologically, they are therefore mostly of little value because they are not in situ . Field archeology is an exception , where it is recorded statistically. Ceramic finds can also be dated and assigned due to their decor.

-

Burials : A distinction must be made between various aspects:

- Disturbed or undisturbed funeral? The absence of any burials is also relevant.

- The funeral rite , for example lying down, crouching, orientation, body or cremation burial, body parts, etc. It is already here, albeit cautiously, that conclusions can be drawn about the social and religious world.

- Grave goods, e.g. B. Flowers, ceramics, weapons, jewelry, possibly if preserved, clothing. They are the most important finds, as they allow statements to be made about the status of the deceased as well as his cultural and economic environment.

- Burial type : single, double, multi-person burial , secondary burial , ossuary , mass grave, etc.

- Grave shape : flat, hill, rock, large stone, chamber grave. (Eggert distinguishes 28 types here alone).

- Grave site : The social context becomes clear here, i.e. grave field or individual grave, settlement burial in the residential area, cave grave, etc.

- Special burial : All cases that do not fit into the above scheme are subsumed here.

- Campsites, caves, abrises and settlements : the first three forms are typical of the Paleolithic, the last is Neolithic (or sometimes even Mesolithic) and later. Correspondingly, much more extensive findings can be made in it than in the places that are only visited sporadically with the exception of caves. Wet soil archeology , in particular, offers great opportunities for finding and analyzing economic and social conditions because of the good conservation conditions for biological materials, for example by examining the house and village structure, the construction and any defensive structures (palisades, ramparts, etc.) as well as the duration the settlement detects. Garbage pits are also revealing and neolithic.

- Hoards (landfills) : Although objects are found here that were landfilled at the same time, i.e. represent closed finds, this can also be repeated landfills and thus non-closed finds , to which the individual finds come, provided that a landfill is unambiguous (e.g. in graves or so-called one-piece hoarding). The functional analysis is difficult here.

- Places of worship : This includes all sites that have once played a role in the religious-cult area. These can be so-called holy places with and without associated tombs. The interpretation as a place of worship can sometimes be tricky, especially in the case of purely natural shrines . Potential sacrifices can play a role in the mapping.

-

Workplaces : Here again, several aspects have to be distinguished in the interpretation.

- Places of raw material extraction : Flint, for example, was extracted as early as the Paleolithic in open-cast mining, but occasionally also by mining, and traded on so-called flint roads.

- Raw material processing : Recognizable by the remnants of these activities, such as raw material depots, discounts, cores , defective or unsuccessful copies, etc. but sometimes also by larger inventories of finished tools.

- Extraction and processing of animal food : Paleolithic mainly so-called slaughter areas, Neolithic pens, fish traps, etc.

- Extraction, storage and processing of vegetable food : planting and storage exclusively Neolithic and later, i.e. fields, water pits, etc., but also ovens, as they are often found in damp settlements.

- Means of transport and facilities : Neolithic bicycles, wagons and boats as well as constantly used paths, landing stages, dams, bridges, etc. Particularly easy to detect in damp settlements, where one often finds very long plank paths and bridges as well as bones from draft animals.

- Rock paintings and cave paintings: They are particularly difficult to date (see rock paintings of the Sahara and Franco-Cantabrian cave art ). Radiocarbon dating is successful with charcoal residues , otherwise one has to rely on content or typological criteria of the paintings, as systematized by André Leroi-Gourhan and others for the Franco-Cantabrian caves.

- Other : This subheading includes potential battlefields, rare large finds such as Ötzi , the menhirs in various local forms and comparable stone installations, bog corpses and river finds, for example from silted river beds.

The differentiation of the find complexes according to John Desmond Clark

In the 1st volume of his Cambridge History of Africa, John Desmond Clark differentiates the following archaeologically conceived grades of prehistoric find complexes in descending order and value:

- Techno complex

- Industry

- Inventory.

- Industry

Application problems

These gradations structure approximately simultaneous findings according to their regional and supraregional value and contextual significance. In this sense, they are relativistically related to one another within a large-scale find situation, but often have cross-connections to other find situations, so that a horizontal and vertical separation is not always successful or unambiguous. This explains the frequent heterogeneity of their use in the scientific literature, especially in the case of the sometimes poor finds outside of Europe. This led and often leads to different interpretations of individual researchers and / or, especially in the case of unclear find contexts and dates, to the impression that the three terms techno complex , inventory and industry , and occasionally also culture (see cultural term above ) are in a certain sense synonymous . But different local traditions at institutes and universities also play a role here. Moreover, the distinction is often not applied consistently, and the term “industry” is sometimes used in a uniform and undifferentiated manner. Nevertheless, the three terms are generally considered useful for a rough structuring, provided that their use is systematic and coherent in itself. (For the definition of culture, techno complex , inventory and industry in the archeology of prehistory cf.)

Techno complex

Instead of “culture”, the term “techno complex ” or simply “complex”, such as the Acheuléen complex, is used as a neutral, linguistically more correct and unambiguous substitute , which makes it clear that it is only a matter of hundreds of thousands, albeit for a long time General and superordinate characteristics of large tool complexes and their manufacturing techniques that have lasted for years, such as rubble tools , nuclear technology , cutting technique , Levallois technique or blade technique , which have certain characteristics in common in methodology, form and style. Sometimes one simply says Olduwan , Acheuléen , Moustérien , Sangoan , Lupemban etc. The term “tradition” is also used in this sense when one wants to focus primarily on typical tools, e.g. B. "Hand ax tradition". The three most important South African complexes of the Middle Stone Age according to Clark are z. B. Pietersburg, Bambata and Howieson's Poort.

In German, for example in Müller-Karpe, who also uses “culture”, the term “group” is often used for complex, e.g. B. Penknife groups .

Industry

One can then further subdivide into individual regional forms of a techno complex , into "industries". The term, which is considered to be relatively neutral in value, was adopted from Anglo-Saxon (the Encyclopedia Britannica uses it almost universally and indiscriminately). Initially, it primarily refers to raw material-related or production-related and thus supra-regional groups of finds of individual artifact classes (e.g. bone industry, blade industry), which, like the complexes, are named after the main sites, e.g. B. Fauresmith industry as a South African variant of Spätacheuléen or Sangoan and / or Lupemban . The term is, not least often due to the sparse finds, particularly fuzzy and is therefore often used instead of “techno complex”, but is more limited in time and location than this. The Chitolian industry , for example, is a largely Upper Paleolithic industry of the Later Stone Age in western Central Africa and is particularly present in the Congo Basin, which is already poor in funds, around 15,000 BP, with potential relationships with the previous Lupemban. Accordingly, this intermediate term is often found synonymous with “techno complex”, as individual evaluation categories play a particularly strong role here. A transition to "inventory" is also possible (see below)

inventory

A third sub-grouping are the small groups of different types of finds in single or few, closely spaced sites, which characterize the local context of the finds, so-called stations , which, for example, are known as variants, assemblages, facies or phases, now usually called local "inventories" in Upper Egypt between 16,000 and 10,000 BP are sometimes incorrectly referred to as industries, even though they do not have any specific cultural, economic or social peculiarities in the ethnographic sense that set them apart from other inventories in the region in such a way that the designation would be justified. The term thus characterizes a spectrum of certain selected types of stone tools, so-called "Leitformen", which has been repeatedly encountered within an industry or a complex, e.g. B. Chopper ( Olduwan ), hand axes ( Acheuléen ), leaf tips ( Solutréen ), stem tips ( Atérien ), microliths ( Mesolithic ), etc. These leading forms play a more important role than the general, but non-specific devices and lithic objects, which are almost always found such as scrapers, chips or cores. Such similar groups of forms can then in turn be combined to form industries or techno complexes that are of overriding importance. Limited statements about the environment, economy, raw material situation, group size, length of stay, etc., possibly even the climate are possible, which could then be related to the local device production.

Tool classification

The classification is an indispensable basic principle of any diagnosis. In prehistoric archeology, several different systems are and were known, with the help of which features can be classified and brought into a system, which usually appear complex in finds. Classification can be analytical or synthetic, i.e. descending dissecting or ascending integrating. However, both are only cognitive ways of classification, not classification itself, because they only differ in the choice of the viewing and starting level. In addition, there are mainly heuristic points of view with their interpersonal, but also intellectual-historical variability. (Remember, for example, the interpretations of archaeological finds as Nordic, Aryan, Germanic, etc. in the Third Reich, for example in the area of pile dwellings )

A classification is based primarily on two criteria: the characteristic and the type:

- A feature is understood to mean characteristics that can serve as units of comparison and thus allow the differentiation or grouping of subsets of these phenomena.

- Type is understood to be a fixed combination of characteristics that characterize a group of specific phenomena.

In addition to the purely descriptive, there are also chronological, functional and regional as well as directly inventory-related aspects and statistical methods.

The two systems presented below each represent one of the two criteria: the first, the mode classification, is primarily a representative of the type classification, the second is primarily based on artifact-morphological features.

The fashion classification according to Grahame Clark

A parent prehistoric division of the Lower Palaeolithic to typological base offers the fashion classification as Grahame Clark has proposed in 1969 and J. Desmond Clark acquired and is still widely in use (eg. As in Phillipson). It bundles the common terms such as knock-off, blade or core technology, Levallois , microliths, etc., avoiding locally-specific assignments in a roughly chronological system that exclusively uses tool shapes and techniques as classification criteria. This systematic, which is easy to handle in practice, was designed against the background of the European and Levantine cultural sequences, but is also suitable for the sub-Saharan area and can even be used worldwide, as it avoids the pitfalls of the conventional period age system as well as the close ties to industry Phases with finite time periods and, to a lesser extent, the discontinuous division of industrial and cultural development processes. It also has the advantage of avoiding the vagueness described above by completely dispensing with rigid phased classifications in favor of a continuous chronological-evolutionary classification of the main tool types. Above all, it is shown here that elements of tool manufacture from earlier times have persisted alongside newer developments, i.e. several m-types can exist side by side, especially with regard to simple techniques that literally run through time, with even declining trends being observed . The degree of adaptation of older technologies while the economic subsistence strategy remains the same is clearly important for this continuity, which can then be expected to show significant differences between neighboring areas and comparable environmental conditions. On the one hand, the knowledge of this phenomenon provides the framework for a new understanding of human tool development.

Their disadvantage is that they make it difficult to subdivide and define an adequate cultural nomenclature stratigraphy with self-contained departments. Still, Clark's tool taxonomy is a useful tool in determining a dominant tool industry, especially as it avoids the outdated chronological implications of the traditional nomenclature system.

There are 5 groups of the Paleolithic from m1 to m5 :

- m1 : End Pliocene and Lower Pleistocene , Old Paleolithic and Early Stone Age . The Olduwan complex with the typical unspecialized rubble devices (so-called choppers), coarse scrapers, spheroids and tools machined on one side, which are supplemented in a later phase by a few rough two-sided tools ( hand ax or biface). The smaller teeing devices are somewhat more varied.

- m2 : The Acheuléen Complex: Old Pleistocene and Middle Pleistocene . Two-sided tools, especially hand-axes and Cleaver , this well-crafted small scrapers and awls addition to the m1 devices of Olduwan.

- m3 : Middle Paleolithic or Middle Stone Age . Flake tools from prepared radial and other nuclei in Levallois .

- m4 : Printing and punching technique with steep retouching for blade manufacture . Pure m4 technology is rather rare in sub-Saharan Africa and is found mainly in East Africa and the Horn of Africa as well as in the southern Sahara.

- m5 : Microliths blunted on one side , especially in shop and composite devices. In contrast to m4, m5 is particularly widespread in Africa in the Later Stone Age and in Upper Paleolithic Europe, whereby m5 is also found earliest in Sub-Saharan Africa worldwide, and notably with the earliest fossil finds of the anatomically modern Homo sapiens , so that these findings possibly provide additional support for the out-of-Africa hypothesis . Most of the tools of the Upper Paleolithic or Later Stone Age belong to this type, which is sometimes considered a prerequisite for the development of the new methods of food production of the Neolithic.

The Neolithic is no longer included in the fashion classification, even if m5 in particular continues there with numerous uses of microliths.

- Mode 1 to Mode 5 and Neolithic: Representative tool types

mode 1 Old Paleolithic chopper , quartzite , from a river terrace of the Douro , Spain.

mode 2 Middle Paleolithic ( Middle Stone Age ) hand ax from the Stellenbosch industry, South Africa.

mode 3 Middle Paleolithic to Upper Paleolithic lace in Levallois technique from Moustéria in Syria.

mode 4 Upper Paleolithic blade cut. Between 17,000 and 9,000 BP. Magdalenian IV.

mode 5 Epipalaeolithic Azilian Point ( microliths ), between 12,000 and 9500 BP.

Neolithic The three main types of equipment and their techniques: stone cutting, stone drilling, ceramics. Atalanti Archaeological Museum , Greece

Artifact-morphological tool typology according to Joachim Hahn

A purely artefact-morphological classification with only secondary systematic chronological differentiation in the respective individual case, which is also mainly limited to Europe, can be found in Joachim Hahn in Recognizing and determining stone and bone artefacts , which on almost 400 pages according to material, basic form, modifications, decomposition - and machining techniques, including those for bone, antler and ivory. The main goal is the highly detailed, hundreds of individual types comprehensive representation of tool production , its material and technical requirements as well as basic forms, dismantling techniques and manufacturing processes, functional and purpose-related results and variants including their chronology and distribution, but not the technological-periodic systematization in narrow sense.

Non-European periodic and systematics (overview)

The major cultural regions of the world are by no means the same in terms of their cultural-historical differentiation system, especially in prehistory and early history. The three-period system can only be used more or less without restrictions in the Middle East, North Africa, North India and regions of Central and East Asia. For large parts, however, it is unusable. However, even in such regions, with their various forms, the tool technologies are closely associated with the respective cultural levels and their subsistence and environmental characteristics, which due to their different prehistoric systematics are difficult or impossible to compare with one another or with the three-period system if one considers these and does not know their framework conditions. At most, a phenomenological comparison of the material criteria such as stone, copper, bronze or iron as well as basic manufacturing techniques that inevitably arise is possible, as well as a connection with the spread of central subsistence technologies such as that of agriculture, domestication or ceramics (it is of great importance for the peasant stock economy, as well as for the barter of agricultural products).

Africa

Especially for Africa, with the exception of Egypt and Northern Sudan, a different prehistoric structure applies , which does not coincide with the European one and, like the latter, show strong regional differences. (Data in BP , only from the Neolithic or in the Holocene is given with BC ):

- Early Stone Age or Lower Palaeolithic (2.6 million to approx. 300,000 or 130,000 if it is to be correlated with the end of the Middle Pleistocene ); the oldest phase or Archaeolithic is called Olduwan , does not yet have hand axes , only rubble tools , i.e. m1 and m2, and ranges from 2.6 to approx. 1.5 million BP.

- Middle Stone Age or Middle Palaeolithic (300,000 / 130,000–50,000 / 25,000). Fauresmith Complex , Sangoan and Lupemban were previously also combined as First Intermediate , which referred to sub-Saharan find complexes that can be roughly paralleled to the late Old Paleolithic and the Middle Paleolithic of North Africa, the Middle East and Europe, while the subsequent Middle Stone Age was roughly paralleled to the circum-Mediterranean Upper Palaeolithic corresponds. According to the Clark system of m2 and m3.

- Later Stone Age or Upper Palaeolithic (50,000 / 25,000–10,000, in Africa but also often to this day, as it has partly survived ethnically). According to the Clark system m3 and m5, rarely m4.

- There is also an Epipalaeolithic in North Africa ( Ibéromaurusia ) and in Sri Lanka , where, according to archaeological findings, it may start at 30,000 BP, and in the Hindu Kush of Afghanistan between 15,000 and 10,000 BC. It also does not coincide with the European Mesolithic and ranges in North Africa from 20,000 BP to 8000 BC. Chr. Or later. According to the Clark system m4 and m5.

- A Neolithic period was initially largely absent, except in North and Northeast Africa, and in sub-Saharan Africa it probably began to develop with millet , yams and sorghum relatively late around 4500 BC. BC and only in the area between the equator and the Sahara as well as in Ethiopia, while in the areas south of it hunter-gatherer cultures persisted for a very long time. The Holocene shepherds' societies of the Sahara occupy an intermediate position, because they raised cattle, but probably no or hardly any agriculture, lived in permanent villages, but often within the framework of transhumance . Overall, the African Neolithic, where it possibly existed outside the high culture areas, is problematic in its temporal sequence due to the natural lack of archaeological evidence (there is hardly anything apart from seed prints on ceramics, and tuberous fruits, for example, are not verifiable at all). The PPN (Pre Pottery Neolithic = Pre-Ceramic Neolithic) as the earliest Neolithic stage is presumably completely absent apart from possibly in Egypt and the Holocene Eastern Sahara, where it could have come from its core area, the Levant, together with cattle breeding. The ceramics appeared as so-called "wave ceramics" (wavy-line pottery) in these areas, however, before 9500 BP, possibly as a local development of the so-called "Early Khartoum".

- Another possibility of chronological gradation in the Holocene is offered by the Sahara rock art in North Africa . Henri Lhote , who discovered the rock art in the 1950s and analyzed it scientifically, differentiated between five regionally different and sometimes overlapping levels according to the content (the relatively uncertain times relate to the Central Sahara):

- Hunters or wild animals or Bubalus period 10,000? –6000 BC Chr.

- Round head period 7000-6000 BC Chr.

- Cattle period 6000–1500 BC (Similarities of the pottery patterns , so-called dotted wave or wavy line pottery , wave ceramics of the Sahara-Sudan Neolithic , 7th – 3rd millennium).

- Horse period 1500 BC BC to the turn of the ages (possibly empire of the Garamanten , Herodotus report, prehistoric to historical, Tuareg script Tifinagh ). The horse was introduced to Egypt in the middle of the 2nd millennium during the so-called Hyksos era as a draft animal for chariots (not as a mount) from the Near East.

- Camel period after the turn of the ages (historically, starting from Egypt, where the dromedary only became established as a pet in the Ptolemaic period between 350 and 50 BC.).

- A Bronze Age and later an Iron Age only existed in the area of high Egyptian civilization, an Iron Age in Sub-Saharan only in the area of the Bantu expansion . The origin, whether in-house development or import, is unclear. Archaeological evidence points to three areas: the Niloten area in the northeast on the central Nile, the area of the great lakes (northwest Tanzania ), particularly north of N'Djamena in Chad . Central Nigeria ( Nok culture ) is another potential place of origin . All three centers evidently developed around the same time in the 6th and 5th centuries BC. Their new technology may have reached the south for the first time in the course of the Bantu expansion, whereby an expansion of the Proto-Bantu from their Cameroon core area to the west into the Nilotic area of central Sudan and thus their knowledge of iron technology is not excluded, at least linguistically . Where this was not the case, it was only the Arab and European traders, conquerors and colonizers who introduced iron technology in sub-Saharan Africa, whereby there was often a direct transition from Neolithic, even Paleolithic, to Iron Age techniques, along with the cultural upheavals that led to this triggered.

- To what extent the early state formations and empires in North Africa and the Eastern Sub-Saharan , which mostly emerged during the first millennium BC in the area where Egypt emanated, later in the first millennium AD along the Trans-Saharan caravan routes , have historical or prehistoric aspects or can even be attributed to prehistory, differs from case to case. However, in some of these empires, which in their structural conception cannot be equated with the "empires" of European character, since they were not based on the possession of land but on the possession of human labor and therefore had no regular and stable borders archaeological finds, but above all the later states or empires that emerged in the course of the Muslim-Arab expansion very well had written cultures. The earliest empire formations outside of ancient Egypt, the empires of Kush , of Meroe and the empire of Aksum, are accordingly historically documented and therefore historical.

America

The problematic and controversial spatial-temporal and developmental division of the history of America does not produce a uniform picture in which all three material criteria of the cultural-period classification (stone, bronze, iron) coincide halfway and which is accepted by all archaeologists, such as the classic three-period system of the Old world. Haberland has therefore divided it into five major periods, which, however, appear extremely different from region to region. Lang also proceeds in a similar way, but is subdivided purely geographically and by ethnic group, as does the Encyclopedia Britannica. The North American cultural areas as well as the Central and South American cultures have their own temporal cultural stages.

North America

There are only very heterogeneous local cultures that are rather irregularly distributed across the cultural areas.

I and II : The following techno complexes can be found in the Arctic and Sub- Arctic :

- Towards the end of the 3rd millennium BC, even Mesolithic microblades culture , the so-called. Arctic small appliances tradition that occurs with late Neolithic culture trains (ceramic), like those found in Siberia. In the central high Arctic, the pre-Dorset tradition can be found around the same time , which in turn is divided into several stages. (S. Inuit culture )

- In the second half of the last millennium BC there are three regional variants:

- The northern maritime tradition ,

- the Norton tradition , Choris and Ipiutak tradition ,

- the Aleut core and blade industry (Pacific-Aleut tradition).

- The Dorset culture (500 BC to 1000 AD) and the Thule culture (1000 to 1800) follow.

- Another prehistoric division of the Arctic includes five stages I through V.

- Stage I:? until 5000 BC BC Paleo-Indian.

- Stage II: 5000 to 2900 BC Chr .: North Archaic.

- Stage III: 2500 to 800 BC Chr .: Arctic small appliance tradition.

- Stage IV: 1600 to 600 BC Chr .: Norton, Choris, Ipiutak tradition, Dorset culture.

- Stage V: 100/900 AD Thule culture.

- III and IV : The eastern woodland in the south and north shows the following cultures:

- The Neolithic Adena culture and later the Hopewell culture . Beginning between 1000 and 700 BC BC, Hopewell from the last centuries before Christian. Doom no later than AD 600

- the Neolithic temple hill builders between AD 400 and 800. Mainly incoherent local cultures such as the Mississippi culture with corn cultivation , which built particularly large mounds and cities.

- Mixed farming (hunter-gatherer and simple farmers) like the Iroquois .