Civaux

| Civaux | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| region | Nouvelle-Aquitaine | |

| Department | Vienne | |

| Arrondissement | Montmorillon | |

| Canton | Lussac-les-Châteaux | |

| Community association | Vienne et Gartempe | |

| Coordinates | 46 ° 27 ' N , 0 ° 40' E | |

| height | 67-149 m | |

| surface | 26.39 km 2 | |

| Residents | 1,203 (January 1, 2017) | |

| Population density | 46 inhabitants / km 2 | |

| Post Code | 86320 | |

| INSEE code | 86077 | |

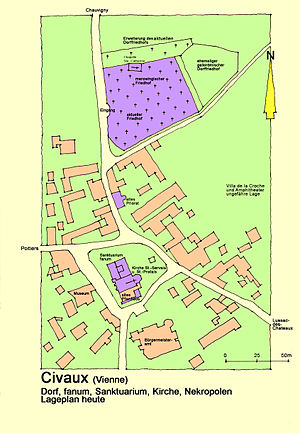

Site plan (2012) |

||

Civaux is a commune with 1,203 inhabitants (at January 1, 2017) in the southeast of the department Vienne , in the region Nouvelle-Aquitaine , about 30 km southeast of Poitiers and 15 km south of Chauvigny , close to the river Vienne . Civaux is particularly known for its formerly extensive Merovingian necropolis and its early Romanesque parish church with its predecessor, a Gallo-Roman sanctuary .

Civaux was a cultural and religious Gallo-Roman center for a long time and consisted of the Villa de la Croche , an agricultural domain , a large aristocratic residence , an ancient theater for about 3000 spectators, a Gallo-Roman presumably double sanctuary (fanum) , another smaller fanum and two grave fields, supplemented by facilities for crafts and agriculture.

history

The historical landscape, called Val de Civaux , stretches on both sides of the Vienne on a strip of land of about a dozen kilometers between the places Salles-en-Toulon in the north and Lussac-les-Châteaux in the south. Civaux is the center, but its history also affects the neighboring municipalities of Lussac and Mazerolles in the south and Valdivienne in the north.

Prehistory

Early origins

Abundant finds of worked stones and bones dating from the Acheuléen (between 500,000 and 300,000 years BC), the Moustérien (between 300,000 and 30,000 years BC) and the Magdalenian (20,000 to 10,000 years BC) in the Sand pits in Civaux and the surrounding communities, but also in caves and under abrises (rock overhangs) indicate a very early human settlement in the area.

Around 15,000 BC BC, in the Magdalenian , lived on both sides of the Vienne people with an artistically extraordinary production of artefacts . More than 500 engravings on moving media have been found in the cave of La Marche near Lussac . These are large discs, plaques or simple rolls on which realistic representations of bears, steppe bison (Bison priscus), deer, cats, mammoths , horses, reindeer and ibex can be found.

In the cave of Fadets , 800 m from the previous one, about 170 burned plates were found, including one with a very precise representation of a person. Other sites from this period were the Grotto of Marche (depictions of a mammoth, a horse and sexual motifs), the cave of Loubressac (stylized bison), the cave of Bois-Rago t near Gouex (abundant finds, such as a harpoon made of reindeer antlers, Engravings on a fragment of the rib, two heads of cattle and a small cat).

Neolithic and Copper Age

In Western Europe, the Neolithic (New Stone Age) began around 6000 BC. And from 5000 BC Agriculture in the Vienne valley had developed far and wide. A high population growth could have been responsible for this. The people lived in villages with houses made of wood and mud, the archaeological traces of which, however, are very small. In addition to livestock farming, sheep and cattle, the cultivation of wheat and barley was successful. Pottery was used for storing food and for cooking food. Working with stone, especially grinding the surfaces, has improved the quality of tools.

In the tombs of Goumoisière, in Saint-Martin-la-Rivière , the first traces of the local Neolithic age have recently appeared. From around 4500 BC. Mysterious stoves were made from heated stones discovered in Claireaux north of Civaux . Six large elongated depressions, 8 m long and 1 m wide and about three more, more or less oval, contained a sediment of coal and large amounts of pebbles that had exploded in the fire. Their meaning is unclear.

Between 4500 and 2500 BC BC, monumental megalithic structures were mainly built on or near the Atlantic coasts of Europe . The dolmens , stone chambers under so-called tumuli (burial mounds), which were accessible from outside via corridors, testify to this . The Loubressac dolmen , south of Civaux, today presents seven columns made of limestone and granite and a chamber 4.0 by 2.5 m in size. Adults and children with ceramic vases and flint tools were buried in it. It was damaged a little while the roadside was being cleaned up.

Arthenacia

At the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC A new cultural group, the Artenacien ( Artenac = name of a site in the Charente ) - late Chalcolithic , around 2400 BC. BC - a vast area in the mid-west and south-west of France. At that time dolmens were still used to bury the dead, but monuments made of dry stone were also built. Several necropolises from this period are known in the Vienne department, including that of Maupas near Valdivienne . 31 graves were excavated in 1883, a burial mound measured 30 by 10 m and 2 m in height. Skeletons of several dozen people have been found. Trepanation (opening of the skull) was detected in five of the dead . In these graves the dead were given everyday objects and offerings to help them cope with the afterlife . There are ceramic vases that presumably contained food, animal bones, flint implements (weapons, arrows, knives) and stone and bone jewelry.

The Western European Copper Age , also known as the Copper Age , ran parallel to the Neolithic , beginning with around 3000 and ending around 2200 BC. Chr.

Bronze age

Towards the end of the 3rd millennium, the Bronze Age began in Europe with the discovery of the bronze alloy made from copper and tin, with arsenic, antimony and lead bronzes in preliminary stages. The economy was still based on the activities of an agricultural and grazing economy. Ceramic production was on the upswing. The use of the new and much harder metal, bronze, increased considerably and lasted until the beginning of the 1st millennium BC. Chr.

The search for raw materials for the production of bronze led to trade on a large scale, sometimes over long distances. Copper came from the Alps, from the Iberian Peninsula or from southwest Germany, tin, from the British Isles, as well as from Brittany . Bronze was used to make weapons and tools (knife, sword and ax, spearheads) as well as jewelry and other items. The deposits on the surface or in rivers, as in the Limousin , were mined for the production of jewelry and objects for cult purposes as well as unusual cones, such as that of Avanton (Vienne) .

Numerous testimonies of burials and other cult activities were discovered in the “Val de Civaux” from the Bronze Age , above all with the help of the increasing use of aerial archeology . The aerial photographs show a very high density of such places of worship on the middle terrace of the Vienne , north of Civaux near Cubord . They mostly consisted of fencing with defensive walls, wooden fences or ramparts, which were often surrounded by trenches and intended for funeral rites or cultural events. They were initially circular and later square, with different dimensions between 6.50 and 15.00 m in diameter or side length.

A salvage excavation was carried out over a strip of land with a length of 2500 m and a width of 20 to 100 m. Of the thirty circular enclosures, eight were threatened by the work of the nuclear power plant and were therefore searched first. With a diameter of 12 to 15 m, most of them were surrounded by a wooden fence. In some cases pyres with the remains of the deceased were found in pits, in others the graves contained fences 15 m in diameter filled with small limestone slabs, and an upside-down stele was buried next to the pit . Eleven post holes were found within the perimeter wall. Some of the enclosures appeared to be related to the burial of the deceased, others to their cremation. The decor of a plate allowed dating to the Bronze Age. Towards the end of the period some enclosures apparently no longer had a cultural function. This was the case, for example, of a circular structure, 6.50 m in diameter, which was surrounded by a trench, at the bottom of which flint fragments and fragments of two deliberately broken containers were found.

Iron age

The Iron Age began around 800 BC. And ended in the 6th century AD, a period that roughly coincides with antiquity . It includes the Hallstatt period , the Latène period and the period of the Great Migration . The democratization of the iron industry and metallurgy revolutionized trade. Iron ore and wood for processing were abundant in the Vienne regions .

Due to its particular hardness, the new metal was increasingly used in the manufacture of most tools and weapons, such as the discovery of a sword in the Tumulus de Bataillerie , a knife in the enclosure of the Tombe-au-Cornemuseux. This included, in particular, wagon wheels, such as the one in the grave of Séneret in the Quinçay community. The work of the bronze smiths continues, but they specialize in jewelry (bracelets, necklaces, rings, hooks, ...), small tools or vessels (kettles).

The settlements in this era often remained at the known altitude. In addition to their function as a residential area, they preserved the traces of economic life, craft and trade, as well as the religious communities.

The pottery developed in the Haut-Poitou , until the 5th century AD. AD. A beautiful ceramic with a metallic glaze , was mostly based on graphite , and was near Civaux found in the camp Cornoin or tumulus de- la battalion (Valdivienne) . They were always used in the Vienne valley , with the large cultural ensemble of grave goods from the Bronze Age. A series of pits and nine round and square enclosures were discovered north of Civaux with the help of aerial archeology, which are considered the southernmost part of all the burial chambers of Cubord in Tombe-au-Cornemuseux . During these excavations, finds of ceramics and an iron knife could be dated to the end of the first younger Iron Age (around 450 BC).

The second phase of the Iron Age (450 to 50 BC) was marked by important changes, no doubt arose from the increase in contacts and cultural exchange with other peoples. It is known as the La Tène civilization (after the name of the site in Switzerland). The historical and archaeological knowledge about this epoch is very sketchy. At the time of the conquest of all of Gaul (58–50 BC) it was almost part of a single cultural and economic system. Only Julius Caesar then recorded the organization of Gaul in his article: “ De bello Gallico ” .

Antiquity

Gallo-Roman camp Cornoin

South of Civaux near the ford of La Biche (deer), the Gallo-Roman camp of Cornoin dominated the valley, which stretched about thirty meters from the right bank of the Vienne. The fortified settlement took up an area of about ten hectares. In the north, natural protection was provided by the steep slope of a dry valley, the Perrofin gorge . It was framed by a rampart developed by the Gauls , made of dry-set stones with cross-laid wooden trunks, interlocked with iron nails 30 to 40 cm in length. Caesar called him Murus Gallicus (Gallic Wall). The former defensive wall can still be seen at 140 m, but from its original height of four to five meters, it is barely two to three meters today. However, the construction was not durable indefinitely, as the wood used rotted over the years. These fortified settlements not only had a strong defensive power, but also had a particularly high level of prestige. The camp was fully active at the time of the Roman conquest and was used until the 5th century AD. A similar wall can be found around the Bibracte camp on Mont Beuvrais in Burgundy . The location of the former Gallo-Roman camp is now marked by a small settlement called Cornoin .

Gallo-Roman burials

At the Croix-de-Laps , three round enclosures, which were bordered by ditches, with diameters of 11, 15 and 17 meters respectively, were found, the burial sites from the late 5th century. corresponded. Anthracological studies and analyzes were carried out, one of which again a ritual ceremony could be proven. The Anthracologie is the study of charcoal that is produced by burning wood. It can be used to prove the age and type of wood. In the southeast of the 2.50 m wide pit, the remains of the burnt deceased were deposited, as well as the remains of the pyre made from oak and blackthorn . Metal parts of clothing such as decorated belt buckles and brooches have also been found again . Further in the pit, flowers and plants with fragrances were placed. Deliberately broken pottery was scattered around the site during the ceremony.

Other sites with similar relics from this period were: La Papiotière (operating a gravel pit) from the middle La Tène period, Ganne Mazerolles, from the end of the old to the beginning of the middle La Tène period, Tombe-au-Cornemuseux , partially from Gallic times, Cubord , from the beginning of the 1st century BC Chr.

Civaux, a Gallo-Roman center

The Gallic tribe of the Pictons , with the capital Lemonum (later Poitiers ) , settled in the area of today's Poitou-Charentes region since prehistoric times . Even after the conquest of Gaul by the Romans from 58 to 50 BC. They dominated this area. The Pictones tribe can still be found today in the name of the capital Poitiers and the Poitou countryside . During the Gallo-Roman era, the area was integrated into the Roman province of Gallia Aquitania , of which Lemonum became the capital . A new urbanism established itself in the big cities, right up to the metropolitan areas (lat. Vici ) and the rural centers and residences of the rural residents (lat. Villae ).

A cultural and religious Gallo-Roman center developed on the site of today's town of Civaux , essentially from the Villa de la Croche , northeast of today's church square, an ancient theater, a Gallo-Roman presumably double sanctuary (fanum) , next to and below today's church, another smaller fanum and two cemeteries, supplemented by facilities for handicrafts and agriculture. The prerequisite for this development and its ongoing operation required a dense network of communication channels and their maintenance.

Communication channels

At that time, several roads supplied Civaux . Even before Roman times they crossed the village from north to south. A section of Départementstrasse 114, which leads past the Dolmen of Loubressac to Tours , today noticeably corresponds to this old path that led to Caesarodunum (Tours) in the north and to Augustoritum (Limoges) in both directions, following the Vienne valley . In an east-west direction, a Roman road crossed the Vienne with a ford near Civaux , the path is now called Argneaux . The formerly orthogonal (constructed with right angles or vertical lines) course of the Roman streets within the former settlement no longer corresponds to today's village streets, but is found again in parts during excavations, for example on the northeast edge of the buildings. In the 19th century a Roman milestone was found, a miliarium that indicated the distance between the place where it stood and the capital or the borders. This was dedicated to Emperor Alexander Severus (222-235). The original site can no longer be given today. It is exhibited in the Poitiers Museum.

In addition, there were old paths on the other side of the Vienne, if only to the fortified settlement of Cornoin, the current path from Perrofin possibly already allowed access to earlier Gallic times. This old name is made up of Perro (from Pierre = stone) and fin (from fines = fine) and probably goes back to the former Gallo-Roman fortifications or the steep cliffs.

In the Middle Ages, Civaux was on the northern border of the Basse - Marche district , but it is quite possible that the Gallo-Roman camp was a clear boundary marker even in pre-Roman times.

The Vienne was undoubtedly a communication channel of particular importance even in Roman times, the archives show that it was until the 17th century. Even the Gallic Pictons used large, clumsily built ships with flat bottoms that were not moved with oars, but with leather sails and iron anchor chains. The large number of towns, ports or fords confirm the role of the river in the pre-medieval economy.

Villa de la Croche

The Gallo-Roman villa was an agricultural domain (French: Domaine, Seigneurie ), a manorial estate and consisted of a series of buildings for representative living, for servants to live in, for farming, as well as a handicraft area. The Villa de la Croche is a large aristocratic residence , built in the Roman Empire (20–360 AD) on an area of around 7500 m². In addition to the main residence, it included the courtyards and gardens of the branches in the area. This villa was still inhabited in the middle of the 4th century, as can be seen from the abundant furniture found.

The property was excavated in the northeast of the church square outside the present-day village and is now in the midst of cultivated fields. The foundations of the extensive residential buildings were exposed, including two cellars that had been converted into storage rooms, which housed plenty of furnishings. In other cellars of the same structure one came across large quantities of ceramics ( terra sigillata "à l'éponge" = "with the sponge"), coins, weavers' weights, figures and jewelry. Aerial photographs of the excavation findings clearly show that the group of buildings in the villa was enclosed by a rectangular area many times as large, which was separated by a wall, probably a large garden. There were still delimitations of partial areas or buildings. Although the finds were badly damaged by the plowing over centuries, the explorations have shown a dense settlement of this area.

Inside the Villa de la Croche , a kiln for ceramics was found in the northwest, which was set a good meter into the floor level. In front of the actual combustion chamber was an equally deep service area, from the bottom of which the furnace was loaded with fuel. In the furnace itself there was a perforated platform just above on which the clay-shaped blanks were stacked. The top of the furnace was covered with a dome, in which an exhaust vent provided the necessary ventilation. This was broken open when the fire was over. The finished ceramics were taken from above. The excavation area of the villa is now almost completely overgrown by nature and can hardly be recognized as such.

Ancient theater

Not far from the villa was the ancient theater of which nothing could yet be excavated. On the basis of soundings, however, its approximate location is known and its diameter is estimated to be around 50 meters. The cavea , the theater's auditorium, made of stone rows of ascending seats, was partly dug into the slope and opened to the northeast towards the river Vienne.

There is no evidence of where the audience that was supposed to fill the theater came from. The ensemble of Civaux , consisting of theater, sanctuaries, villa and cemeteries, is compared to the ruins of Sanxay , a Gallo-Roman spa and cult site, about 35 km southwest of Poitieres , made up of a temple district, thermal baths , a theater, with associated living and hotel buildings for their staff and guests, on a scale that would be enough for a big city. The theater has an outer diameter of 90 meters and held around 6500 spectators. The facilities were well known and people made pilgrimages there from great distances in order to enjoy a few days of “wellness” for body and mind .

That was certainly not the case in Civaux . With a diameter of 50 meters, the theater could hold an estimated 3,000 spectators and the thermal baths were either missing or not yet discovered. The theater was probably a prestige object of the gentlemen residing in the nearby villa , who could certainly use their own thermal baths in their house.

Gallo-Roman sanctuaries

From the Gallo-Roman sanctuary (Latin: fanum , sanctuary) from the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, the excavation findings presented to the public north of the church provide clear information about its original appearance. A fanum , the common temple popular in rural areas, usually had a square shape and usually consisted of a small square room, the cella , in which the sculpture of a deity was displayed. The cella were surrounded on all sides by a gallery that was open on all sides or partially, the length of which was almost three times as long as that of the cella . The cella was covered by a gently sloping gable roof or a pyramid roof, while the gallery on all sides was covered by a circumferential pent roof, which attached a little lower to the cella and was supported on the outside by columns that perhaps stood on parapet walls.

The excavations of 1960 uncovered the foundations of three frames of such a fanum on the north side of the church, the fourth one was initially believed to be under the north wall of the church. At the same time, the foundations of the cella were exposed. In 1988 the continuation of the eastern border of the fanum on the north side was discovered on the south side of the church , which then bends to the west outside the attached old rectory and is about as long as the width of the northern border. With this discovery, one comes to the assumption that the borders of the fanum on the north side of the church were connected with those on the south side and enclosed an elongated rectangle. Likewise, it is assumed that south of the center of the long rectangle, under the buildings of the church and the rectory, there was perhaps a second cella , which together with the first formed a double fanum in a common border. Two separate square sanctuaries with a small distance from one another would also be conceivable.

In the Vienne department, a sanctuary of Masamas in Saint-Léomer is known which also has two cellae in the same rectangular border, which confirms the assumption for Civaux .

In the immediate vicinity of the sanctuary (s) there was a spacious square where the faithful who visited the temple (s) could gather and lead to their entrance. He was likely surrounded by private houses, shops, and businesses. In the east of the sanctuary, still within the aforementioned development, another but much smaller fanum was discovered in 1990 , as well as a cemetery that complemented this ensemble. Its square edging with a side length of 8.60 m contained a cella with an inner side length of 1.70 m, which was enclosed by a large gallery two meters wide. The walls were made of limestone and the roofs were covered with tiles.

Gallo-Roman cemeteries, funeral rites

The cemetery of the Gallo-Roman settlement was outside the closed development, roughly on the northeastern adjacent site of the much later Merovingian necropolis , barely 200 meters from the sanctuaries and a little closer to the theater and the Villa de la Croche . Apparently it was used from the beginning of the 1st century to the second half of the 2nd century.

The cemetery is known from drawings by the actor and draftsman Beaumesnil from the mid-18th century, although not particularly reliable, and from Siauve , as well as from descriptions by Maximin Deloche , at the beginning of the 20th century, as well as of steles from the Proximity have been found. Deloche described masonry pits containing burnt bones and burial objects found by H. Duguet . He took into account the Roman stelae , fillings of sarcophagi that contained ashes of the deceased.

Another piece of information confirmed the existence of the Gallo-Roman cemetery at this location. In at least two cases, in 1737 and 1860, the pastors of Civaux in Poitiers reported that Roman coins deposited in the tombs were found in the fields of farmers between the Merovingian cemetery and the Vienne, as the one above corresponds to the situation described.

It is difficult to determine the importance of this cemetery. At least three steles from the 3rd to 4th centuries were found there. They are indigenous creations and have a popular style. The first is 1.40 m high and shows a man in the dress of the Gauls who is holding a hammer or an oar in his hand and pressing a child's hand against a kind of purse or a toy. On the second there is a figure wearing a short cape and holding a hammer or ax on its chest. The third stele shows an arcade which is covered by a triangular pediment . In it stands a bearded person in a knee-length robe who is leaning on a walking stick with his left hand. In her right hand she is holding a child half her size in a knee-length dress who is holding an object in her right that looks like a hammer.

The location of the Roman cemetery at this point suggests that the settlement area did not expand beyond these limits. A small deep wall ran across part of the Merovingian cemetery from east to west. It could have been a wall at the end of the Gallo-Roman cemetery.

In the 1960s a rectangular Gallo-Roman sarcophagus was found in the cemetery of Pièce-des-Genêts , on the edge of the road from Civaux to Toulon , about 700 m north of the village. It had no lid, was filled with earth and contained a sickle , an ax, a bulbous vase (French: balustre ) and a ceramic fragment of the type “à l'éporge” (“with the sponge”). The excavations in this cemetery began with an enclosure of 250 m², which was surrounded by a dry stone wall. There were 30 to 40 cremation graves in it, plus four more outside the wall. A “ ustrina ” (a kind of crematorium ) in the form of a simple pit to cremate the deceased, replaced the pyre here.

After the cremation, the ashes and the remains of the bones were placed in the burial urn made of ceramic or glass, which was then buried in the ground. Ceramics, coins and objects were sometimes added to them.

Cremations and body burials always existed side by side. From the 4th century BC Until the 1st century AD, cremation was the norm, later in body burial became the rule.

In the northwest of Civaux an isolated grave with rare contents was found. A glaze urn was housed in a limestone box, the lid of which was decorated on one side with an “ascia” (ax or Herminette = hoe with cross-cutting edge ), a symbol of the inviolability of the tomb. In front of this box was a device on which the Etruscan- Roman ritual “Os resectum” took place before the cremation. A part of the body was cut off from the deceased, usually a finger among the Romans, and then buried separately or in the urn with the ashes of the deceased before it was buried. This cult, known in Rome but rarely documented in Gaul, testifies to the social status or the Roman origin of the deceased.

The settlement of Civaux cannot be classified as vicus (settlement in the secondary area) in the Gallo-Roman era . Rather, this social organization with economic and religious diversity was directly related to the life of the noble family in the Villa de la Croche , who financially participated in the realization of the public buildings, monuments and their operation.

Late antiquity, time of the Great Migration

The late antiquity or migration of peoples with their great changes in Europe from about the 4th century to the 6th century, attracted especially the fall of the Western Roman Empire to the west and the reasoning of the Merovingian and Christian Frankish kingdom .

The Christianization probably began at the end of the 3rd century, especially in the valley of the Vienne . The first local churches were built in the 4th century. In Civaux , monuments and finds testify to exceptional and early religious activities.

Clovis I (French: Clovis ), Frankish king from the Merovingian dynasty , was one of the main characters in the historical developments in the west of today's Europe, also for the valley of Civaux . He subjugated the Visigoths under Alaric in the Battle of Vouillé in 507 , but more likely at Voulon , about 30 km west of Civaux as the crow flies. He is considered to be the founder of the Frankish Empire, which was to exist until the 9th century. His conversion to Catholicism towards the end of the 5th century, instead of - as was customary with the Teutons until then - to the Arian form of Christianity, was an important setting for the further course of medieval history.

Of particular importance for the history of Civaux are the remains of the former Christian-Merovingian necropolis, which adjoined the older Gallo-Roman local cemetery to the south-west, but which have now been greatly changed.

Two legends have been handed down in the valley of Civaux :

After the first, Clovis and his Merovingian army tried, after a long journey, to find a passage through the floods of the Vienne near Civaux . In a miraculous way a deer (French: la Biche ) showed him the place of a ford. His army was then able to cross the river and victoriously end the battle (presumably in 507 of Vouillé / Voulon ). A spring rose under the hooves of the royal horse; the soldiers could be tended and the horses watered. The survivors were baptized in Civaux . A large number of existing sarcophagi provided the opportunity to bury those who fell in battle.

Three field names still remember these events today: “Le gué de la biche” (The ford of the deer), “La Font Chrétien” (The Christian spring) and “La Chaise-du-Roi” (The king's chair). The Gue-de-la-biche is marked near the village of Loubressac on the left bank of the river by the small Romanesque chapel Saint-Silvain with residential buildings, the remains of the former Loubressac priory .

According to a second story in the 12th century, the author of the song “de geste” (= of the deeds) of the Girart de Roussillon delivered that a fight against King Charles the Bald was waged in the 9th century, in "Sivax, with a port on the Vienne " took place and cost seven thousand deaths. They would have got a last asylum in time, through a large amount (French: Pluie = flood) “of beautiful and white sarcophagi” .

In both legends one can definitely find similarities: especially many sarcophagi, which are only necessary for a great battle and “which only heaven can provide”.

First Christian Merovingian church

The Merovingians preserved the Gallo-Roman culture, made use of the knowledge of the old Gallo-Roman aristocracy and leaned on the late Roman administrative practice. Already at the end of the 4th century the Merovingians built the first Christian church in Civaux , of which the walls of the choir apse bear witness. In the floor of the apse were the remains of another baptistery , a repeated confirmation of the importance of Civaux as a religious center. The masonry made of flat stones and the pink-colored mortar, which suggests the admixture of brick powder, point to Roman traditions. A nave was probably attached to the apse , there is no evidence of its size or appearance, but which was in the frame of the presumably double fanum and in it above the foundation walls of the second cella . Maybe the ship was only as wide as the apse.

The placement of the church in the middle of the former Gallo-Roman sanctuary was supposed to symbolize the victory of early Christianity over the past paganism of the Romans.

In many post-Roman ecclesiastical, public or private buildings, as well as in burials, the abundant stone materials of the Gallo-Roman buildings and sarcophagi were reused, which contributed to the attractiveness of the location.

Christian-Merovingian necropolis

The burial place of the Merovingian necropolis remained for a long time the most important and probably also the most economical facility in the village. It is located on the east side of the road that branches off from the church square and leads north to Salles-en-Toulon, outside of the closed development (see map at the beginning of the article). Today's property with its compact polygonal outline has an average size of 60 by 70 meters, which corresponds to a good 4000 square meters. The cemetery has had its current expansion since the 18th century. The external peripheral location has often made it easier for graves and stone materials to be looted over the centuries . For example, the sarcophagi were popular in agriculture as feed troughs or containers for seeds.

Father Routh , author of a report from 1737 on the first excavations in the necropolis, writes that the cemetery was then more than two hectares (20,000 m²), which is at least five times the size of today. This certainly includes the northern and eastern properties. He went on to explain: "There were also few sarcophagi in the neighboring areas" . According to his descriptions, there was chaos at the time: "Open sarcophagi, lids, columns or Gallo-Roman stone slabs were mixed up" . The number of accumulated sarcophagi in the early Middle Ages is estimated according to the sources at 7,000 to 16,000 pieces.

In a graphic by Beaumesnil , around 1747, of which a replica is on display in the Museum of Civaux , the position of the necropolis is strangely shown to the northwest and closer to the church, and rotated by more than 45 degrees. It in no way corresponds to the actual location (see map of today's location) but has similar proportions and structures, and the 15th century chapel is roughly correctly placed in the enclosure and was already a ruin at that time. The sarcophagi are shown in seamless rows and also extend over the adjacent properties, such as that of the Gallo-Roman cemetery, or the extension of today's local cemetery. Nothing can be seen of the chaos described above. The draftsman could perhaps have depicted a “reconstruction” of the greatest extent of the entire necropolis. In a second graphic from the 18th century, in perspective, the chaos of the remaining sarcophagi was depicted almost realistically. The older access to the cemetery is also located on it in the sloping southwest corner. The chapel ruin is roughly the same as today.

In connection with the first excavations in the 18th century, the largely intact sarcophagi were brought together to the present area, some of them rearranged in rows, provided with matching lids and a distinctive enclosure made of the many surplus sarcophagus lids, which are placed upright in the ground let in, surrounded. The fence made of vertical stone slabs is reminiscent of the stone setting of the menhirs of the megalithic cultures . The access door, initially located in the southwest corner, was later moved to the center of the west wall.

The sarcophagi have uniform production characteristics. Most of the containers have trapezoidal outlines. The often flat lids very rarely consist of three parts and usually have no decoration. The lengths are different, adapted to the size of the buried, there are even small sarcophagi for children. The thickness of the walls is 8 to 10 cm. These containers are trimmed with tools. Pillows and head recesses are sometimes carved into the stone of the coffin.

Some containers are deeply hollowed out, like architectural elements of monuments from Roman times. On some specimens, Latin or Greek crosses are preserved at the head of the sarcophagus . Early authors have confirmed the presence of sarcophagi for two or three people, such as those seen in the Saint-Jean de Poitiers Baptistery , as well as in Saint-Pierre-les-Églises near Chauvigny . Some groups or rows of containers can be viewed there. But because of their numerous changes, it cannot be said that they are all originals.

Like the containers, the lids are trapezoidal. They are flat, but often also adorned with a ribbon in the entire length that is crossed by three broad ribbons in the transverse direction. There are many open questions about the meaning of this decor. It seems that it is a somewhat simplified imitation of ornamental motifs of Roman sarcophagi, as the stonemasons worked in the immediate vicinity of the Gallo-Roman necropolis. This decor was very common in the region and characterizes the sarcophagi of the so-called Poitou type .

Drawings by Beaumesnil , Dom Cabrol , Siauve and Pater de La Croix represent various forms that confirm this hypothesis and show a chronological development. Some are partially round or rounded. There are also numerous reused stones from Roman columns, pieces of friezes or steles that are affixed to the back. These lids are sometimes engraved with characters at head height: Greek or Latin crosses, tridents, anchors, fish, the alpha and the omega, often simple names such as Maria, Ulfino, Pientia, Amada, Sancta, inscriptions are rare. In the museum of Civaux you can even find a headless Roman sculpture that was used as a sarcophagus lid.

The existence of the aboveground ruins of the theater, the villa and the sanctuaries in post-Roman times, which was sure to continue for a long time, also supplied the burial places with stone material, which was probably inexpensive to demolish in the immediate vicinity. The considerable effort involved in loosening and shaping the material from the quarries was reduced significantly. The large blocks of the theater's seating steps may even have been used to make sarcophagi.

The oldest sarcophagi date from the end of Roman times and the beginning of the early Middle Ages. They are rectangular, extremely solid, and are covered by roof-shaped lids made of four parts, some of which are decorated with decorations. This was followed by the trapezoidal sarcophagi with different lids, like in the form of a roof, rounded or flat, but often decorated with stripes in the longitudinal axis and in several transverse axes.

In the High Middle Ages not only trapezoidal or rectangular sarcophagi were used, but also casings made of dry stone, chests made of wood, or again graves without containers directly in the ground, with tombstones or steles to mark the position of the grave. At all times the deceased could be buried in mausoleums (small burial buildings). No richly decorated sarcophagi have been found in Civaux ; no doubt, looters have managed to remove the most beautiful specimens. Most of the tombs are characterized by great simplicity.

For the production of sarcophagi, the organization of the production and the marketing are equally important. There were workshops in the quarries, such as those of La Tour-aux-Cognos , Font-Chrétien, Guillotière and Vallée-aux-Tombes. Marketing took place on site, some sarcophagi were exported by water to other neighboring communities, to the center and above all to the Loire .

The stone cutters were artisans or simple workers. It seems that this type of activity was associated with a social organization where religion and aristocratic power are very close to each other. There are indications that a large cemetery could only be economically sustained if it was associated with ownership and the formation of profit. It is certainly no coincidence that the song De geste de Girart de Roussillon recalls the location of Civaux and speaks of a feudal abbot who controls the manufacture and marketing of sarcophagi. From the 5th to the 7th and 8th centuries, the necropolis developed in the ground next to the Gallo-Roman burial ground and perhaps gradually at its expense.

Other burial sites in the area around Civaux, in the early Middle Ages

In 5 km north of Civaux , the Claireaux cemetery, near the Dive, extended over an area of 600 m² and contained 172 row graves. It is proven for the 5th or 6th and for the 8th century. Several groups of tombs, the structure, orientation and dating of which differ - there are limestone containers next to each other, rectangular wooden boxes that were inserted into large pits, then the same type of tombs, but trapezoidal, and finally trapezoidal sarcophagi. The reuse of sarcophagi as well as graves has been proven. One of the graves contained a simultaneous burial of a man and a woman. In six graves jewelry objects were found, dated to the 6th and 7th centuries, such as brooches, rings and belt buckles. It is likely that it was near a town.

Not far from here, in Cubord-de-Maison-Neuve , two sarcophagi were found that contained the remains of seven people. One of the lids is richly decorated.

Just 700 m from the village of Civaux , on the way to Loubressac in the Monas plain, É.-M.-Siauve discovered some sarcophagi in the 19th century , two of which are decorated with a Latin cross. During an excavation, some walling was found, as well as other graves, in which up to three people were buried. At the beginning of the 20th century, Henri Duguet undertook research in the same place. He discovered the remains of a small square building, the floor of which was made of flint overlaid with concrete . A so-called crapaudine (= "toad", pierced stone or metal plate in which a door hinge rotates) was found on the doorstep in the north and the lintel rested on the floor. There were graves all around. Some lids are decorated with ribbons lengthways and crossways or with different motifs such as trident, star, wheel and the Greek letter rho . One was specially decorated: three Greek crosses towered over two spirals and penetrated one another. The dating of the building is controversial and ranges from the Gallo-Roman period to the early Middle Ages, as well as its importance, such as a small temple, a private burial chapel or, more likely, an oratory for the cult of the dead.

middle Ages

The Middle Ages cover a period from around 500/600 to 1500 AD and are divided into three sections, namely:

- Early Middle Ages: 6th century to early 10th century

- High Middle Ages: beginning of the 10th century to around 1250.

- Late Middle Ages: circa 1250 to circa 1500.

Early middle ages

The early Middle Ages was this long time, from antiquity (Gallo-Roman period) to Romanesque , which extended to the so-called Merovingian and Carolingian periods, from the end of the 5th century to the beginning of the 10th century.

Early parish and a priory

Towards the end of the Roman Empire, the village did not disappear like other Roman or Gallo-Roman settlements. Civaux owes its prosperity to the early spread of Christianity . The tradition of the Gallo-Roman sanctuary was adopted by the early Merovingian Christians and continued with their own sanctuary. In the northern gallery of the ancient sanctuary, a stone baptismal font from the 3rd century was excavated in 1961 . Above this, a baptistery was built in the 4th century using the partially preserved walls of the former northern fanum and the reconstruction of walls on the still preserved foundation walls , the only known at that time in the rural areas of Poitou . It was used for adult baptism, also known as the baptism of believers, which was customary at the time, in a building or room that was independent of the church. To do this, the person to be baptized climbed a staircase into a basin set in the floor, which was filled with water about knee-deep, and was doused with this water by the baptist. A Christian community existed here since the end of the 4th or beginning of the 5th century.

The prosperity and notoriety of Civaux from the 4th to the 10th centuries were remarkable. The reasons that led to the construction of the great Merovingian necropolis are still little known. In any case, it was one of the largest in the wider region when it was first created. Its foundation and its existence was only allowed under the supervision and dependence of a bishop. The early existence of a Christian community in Civaux can be explained in part by the influx of pilgrims who were attracted by the presence of relics such as those of Saint-Gervais and Saint-Protais , or by the influence of certain aristocratic persons who converted to Christianity were, perhaps also because of the proximity of the bishopric of Poitiers . The long cultural tradition, especially the funeral rites in this part of the valley, undoubtedly played an important role.

The components of this center of religious life, such as the church and its relics, the priory , the baptistery, the necropolis, were not without effect on the local economy. In addition to the manufacture and marketing of sarcophagi, there were a number of church regulations that created financial advantages for the benefit of certain institutions or people. In the early Middle Ages, the bishop was able to grant the right to preach as well as the right to be buried, even to be baptized. From the end of the 6th century, the faithful had to pay a tithe (in money) for the various services. A few examples show that a place could be obtained in which the monopoly of baptizing and burial was granted for a large number of parishes in the area.

Saint-Gervais and Saint-Protais

In the choir of the church of Civaux there are representations of the instruments of their martyrdom of Saints Gervasius and Protasius , the sword with scabbard and a scourge weighted with lead, and palm fronds as symbols of their martyrdom. In 386, St. Ambrose (* 339 in Trier, † 397 in Milan), then Bishop of Milan, discovered the relics of the two. Some miracles occurred and the cult spread quickly but was short-lived. There are nine churches dedicated to the saints along the Vienne. Because of the great importance of the Civaux site in the Middle Ages, historians think that at least parts of the relics of the two were kept in the church.

Intensive use of the necropolis

More recent excavations from 1962 to 1967 in the great Merovingian cemetery have shown that many dead were buried in certain places in the depths during the Middle Ages. The tombs were used very intensively and various types of burial were found, such as graves in the ground, graves in timber boxes made of wood or sometimes just hollow spaces made of stones and containers made of dry stone. Sometimes only a few stones seemed to have delimited the grave site, for example around the skeleton or just around the skull. A child's grave consisted of two Roman tiles made of burnt clay, which were also made of earth. The graves were usually lined up in a row, which means that the markings on the surface sometimes reflected the stock below. Other groups of tombs of the same type. were updated again, like five dry stone boxes, dated through a glass bottle to the time of the High Middle Ages, one of them containing the remains of three people. These types of graves have endured for long periods of time. Informative “furniture” was also found in or near the grave sites. In a grave, next to the skull, there was a bottle made of glass and ceramics, which bear witness to the 12th to 14th centuries. Some coins and shards of pottery from Roman times were found in the landfill, particularly near the ancient wall. Numerous re-uses of the sarcophagi have been demonstrated.

Medieval cemetery near the church

From the middle of the early Middle Ages, around the 8th century, the Christian believers increasingly looked for resting places for their burials "ad sanctos" , that is, with the saints, in the places of worship with relics of saints, who undoubtedly include the martyrs Gervais and Protais were. The realization of burials so close to the church was the desire of early Christians. In the Carolingian era , in the 8th century, adult baptism declined in favor of infant baptism. This also made the use of the baptistery with its large baptismal font increasingly superfluous.

Early medieval sarcophagi were particularly numerous on today's church square, especially in the surrounds of the northern fanum, but also on the south side of the church and on its choir apse. There were significantly more than can be seen today. After the excavation, they were largely covered again.

Towards the end of the 18th century, Dom Mazet studied the burials in the square north of the church, and observed frequent superimpositions of graves, which often contained several skeletons. He had found up to seven levels of the sarcophagi north of the church. In the garden of the old rectory in the south of the church, excavations between 1987 and 1988 found sarcophagi and graves from the 5th to 8th centuries with similar arrangements. The excavations also carried out on the church square in the 20th century have shown that most of the sarcophagi have been reused. Therefore, the date of their installation and use cannot be clearly established. In other comparable finds in the Vienne department , stacking of sarcophagi around cult buildings on at least two or three levels has been proven, for example in Champagne-Saint-Hilaire , Ussodun-Poitou and Savigné . These graves were either re-uses or changes to the adjacent cemetery.

But it was even more popular to be buried in church. In the Middle Ages, this became an inheritable privilege for some noble families, such as the lords of Genouillé. Excavations have shown that in the north and south of the Christian sanctuary medieval tombs have been found, dated by vases or various objects.

At the same time, the burials continued in the necropolis. There were again vases, bottles made of glass and coins, over a longer period of time, from the early Middle Ages to the 18th century. The burials in the parish cemetery continued around the church until the 18th century. Around 1715 the Bishop of Poitiers forbade burials in this place. The burials then took place again and exclusively in the necropolis. This practice lasted until a few years ago and resulted in the destruction of precious old graves, as the sarcophagi were damaged when digging pits and were often broken into many pieces. About 20 years ago the community laid out a new cemetery north of the old fences; no burial sites were found there during previous systematic archaeological research.

High and late Middle Ages

In the High and Late Middle Ages, the role of the rulers seemed to have come to an end, such as that of the lords of Genouillé . In a treatise from 1439 it is said that they had to “... to consider their graves in the church of Civaux (...) in front of the altar of St. Bloys (Saint Blaise) ” , or the lords of la Tour-aux-Cognos .

The church of Civaux was listed in a charter (dispositive document) of the abbey of Saint-Cyprien in Poitiers from the years 1097 to 1100 ecclesia de Sitvals (= Civaux ). The building was changed and restored in numerous sequels. In the 10th and 11th centuries, while maintaining the Merovingian apse of the early Middle Ages, a single non-vaulted nave was built in the extension of today's nave, illuminated by four small, slender, arched windows on both long sides, as they are still on the north wall sees. Four strong columns were erected in the choir apse in order to build the church tower on top of it, without today's upper storey. The spire and the saddle roof of the ship probably had roof surfaces that were less inclined. The length of the nave is exactly the same as the width of the borders of the Gallo-Roman sanctuaries. Its east and west walls stand on the foundations of these enclosing walls. The north wall of the ship rests on the foundation of the southern enclosure of the northern fanum .

In the 12th century, the tower was increased by one storey and got a steeper helmet, while the nave was divided by two rows of round columns and covered by three barrel vaults and received a steeper roof, everything as you can still admire it today. The capitals are decorated with figures and fantastic animals and floral motifs in the tradition of Poitou . The inner vaults made the rather massive reinforcements of the facade wall with massive buttresses necessary.

This extensive expansion and reconstruction of the Romanesque church coincided with the heyday of pilgrimages to Santiago de Compostela , when hundreds of thousands moved south every year in the first half of the 12th century. The proximity of about 30 kilometers to Via Lemovicensis (starting point Vézelay , Burgundy ) one of the four main routes to Santiago, which still met in France near Ostabat in Béarn and the existing relics made Civaux an attractive stop on the arduous route. Churches, monasteries, hospices, hostels and, occasionally, cemeteries for pilgrims who were unable to cope with the rigors of the journey and died on the way were built or developed along these paths. In any case, the church of Civaux , its priory , as well as its necropolis , certainly played a not inconsiderable part of the pilgrims' donations. After the middle of the 12th century, pilgrimage movements declined due to the disputes between France and England over Aquitaine and dried up completely in the wars of the 13th and 14th centuries. Presumably, therefore, the planned expansion or completion of the Romanesque church building did not take place.

Former priory of Civaux

The remains of the former monastery of Civaux, called “la Grande Maison” (the big house), can be found on the road that leads north to the necropolis . This priory , which in the 11th century was dependent on the Abbey of Saint-Cyprien-de-Poitiers and from the 12th century on the Abbey of Lesterps , in the Charente , definitely followed an earlier foundation structure of the early Middle Ages, of which one cannot explain the meaning knows, maybe it was a small monastery. A 13th century prior's seal was found in a tomb. The priory served as the rectory until the new rectory was built in 1772 on the south wall of the church.

Chapelle Sainte-Catherine

The Sainte-Catherine chapel in the Merovingian necropolis of Civaux has long been a ruin that fits seamlessly into the melancholy ambience of the cemetery atmosphere.

It was built in the 15th and 16th centuries. On its simple rectangular floor plan, the gable walls of the east and west walls and the side walls rise almost completely, on the ridge of the west gable a bell wall with a round-arched bell hatch. Various small arched window openings have been cut out in the walls. The chapel was built over the foundations of a previous structure from the 11th and 12th centuries. The recently updated excavations led to the discovery of the remains of a semicircular apse of the previous chapel at the head of the building, but not in the current church axis, but shifted slightly to the south. Inside the chapel, reused graves, the functional altar, some coins and a bull from Pope Clement VII (1523–1534) were found.

Development of the village

In the high and late Middle Ages, the actual settlement area remained well above the area inhabited in the Roman era. The church has always been the center of the village. Later, the development developed along the two ancient main axes, which, however, changed their orthogonal lines a little and shifted the occupation of the open spaces. Apart from the church, almost nothing remained of the medieval houses in the village, apart from the finds that indicated a priory. (For a map see the picture at the beginning of the article)

Closer surroundings

Farms and scattered settlements have existed in the vicinity since Roman times. Others, like the district of La Tour , were founded near the château.

Only remnants of the medieval castle of Genouillé remained until it was rebuilt at the beginning of the 20th century.

The Château La Tour-aux-Cognos today presents itself with a square donjon (castle keep) ten meters long and twelve meters high and is divided into four floors. This fortress was built in the 11th or 12th century by the Conienses , lords of Lussac . This rule depended on the feudal lordship of the de-Calais , whose seat was in L'Isle-Jourdain . La Tour-aux-Cognos took part in the surveillance of the Vienne valley , like all the castles that were on the river. A group of ruins remained of it since the 17th century.

The Loubressac Priory has existed since at least the Romanesque period. It still exists there today near the Gue-de-la-biche from the building of a chapel dedicated to Saint Silvain with adjoining residential buildings. His wooden statue from the 15th century that adorned the altar is currently in the parish church of Mazerolles. Towards the end of the late Middle Ages, Civaux finally lost its important position. The river, which has been the source of all human activity in the Civaux Valley for 350,000 years , has been forgotten for several centuries.

Since 1980, Civaux once again attracted the attention of mankind, who built a nuclear power station over its shores, which has been in operation since 1998.

Buildings

Romanesque parish church of Saint-Gervais and Saint-Protais

Dimensions (approx)

- Total length (nave and choir): 26.00 m

- Longhouse length (outside): 18.30 m

- Width of the nave (outside): 12.30 m

- Choir width (outside): 8.50 m

- Longhouse length (inside): 16.60 m

- Width of the nave (inside): 10.30 m

- Central nave width: 3.20 m

Outward appearance

The choir of the church is not oriented exactly to the east, but is pivoted about 20 degrees to the north. But that probably comes from the specifications found at this point by the ancient sanctuaries. The east, west and north walls of the nave stand on the foundation walls of the previous structures.

In 1772 a parsonage was added to the entire south wall of the church, and further forward in the choir area a sacristy, which covered some of the external appearance of the church, especially the windows in the first and second yoke.

Longhouse

The rectangular nave is covered by a gable roof with a roof pitch of around 45 degrees, which is covered with red tile shingles. The eaves are supported by visible rafters and protrude slightly. The rainwater that runs off is caught by copper gutters and drained off via rain pipes.

The side walls from the 10th and 11th centuries are divided into four bays by five slightly projecting buttresses , the steeply sloping tops of which extend up to the height of the apex of the windows. Their large-format white to light gray limestone blocks have the same layer heights as those of the subsequent blocks of the walls, which indicates that the pillar templates were erected together with the walls and were not bricked up with the subsequent vaulting. It is noticeable here that the first yoke is narrower than the other three. The first large-format stones next to the pillars are continued by small-format, irregular field stones . These surfaces have been partially stripped off with a beige plaster so that individual stones or groups of stones stand out. A small, arched window has been cut out in the center of each yoke, the reveal edges of which are framed with large-format stone . Your window sill is about two thirds of the height of the wall.

The facade consists of the lower, rectangular, flat west wall on which the gable triangle rises, the verges of which are covered by the tile shingles of the roof surfaces. The flat gable field protrudes a good 20 centimeters from the lower wall. The cantilever is supported by 16 blind arcades that are lined up next to one another and stand on 17 corbels , the last arcade at the south end has been destroyed. The corbels each consist of a lower part with an L-shaped cross section, the inner surfaces of which are slightly rounded, in which animal and human heads are inserted, but also entire bodies.

The subsequent installation of the nave vaults in the 12th century made additional strong and expansive buttresses on the facade necessary as an extension of the partition walls between the naves. With their steeply sloping tops, they reach just below the corbels. A reinforcement of the already existing buttresses on the longitudinal walls was unnecessary because the new shear forces (laterally acting forces in the structural engineering) of the vaults and their lower chords were absorbed by installing wooden tie rods in the nave. The subsequent addition of the huge buttress on the northwest corner due to the vaults can hardly be explained. Presumably, however, there were subsidence of the subsoil at the corner of the building, which the aim was to render harmless. In any case, such additional support was dispensed with on the opposite corner.

The round arched, two-winged main portal is surrounded by simple, right-angled and simply stepped reveal edges. The much smaller round arched window above is also stepped, but the arches are additionally covered by a round bar, two valley profiles and a cantilever profile. The apex of its arch reaches almost under the corbels.

Between the portal and the window and the two buttresses, a flat inclined monopitch roof made of a simple wooden construction is inserted. Two corbels above its ridge and two below the eaves, on the top of the buttresses, show that this canopy was once much steeper and more expansive than it is today.

A small rectangular window is cut out well over half the height of the gable triangle. The gable ridge is crowned by a stone Latin cross.

A Latin inscription, on the buttress to the right of the entrance, from the beginning of the 12th century, reads in the legible parts: "Here is the house of the Lord ... firmly established." The word "ignea" (fiery) on this very damaged stone could indicate that the work cited there was necessary as a result of a fire.

The east wall of the nave, dating from the 10th to 11th centuries, overlooks the attached choir apse and the bell tower rising from it. The two corners of this wall are stiffened in both directions with the original buttresses.

Choir and bell tower

(See photo at the beginning of the article) The choir has an outline, consisting of a rectangular “choir bay”, to which the apse adjoins in the form of a half decagon. It has seven flat wall sections, which are separated by six ridges running vertically over the entire height. The masonry consists of white, neatly hewn flat limestone blocks, in regular layered masonry . It is a comprehensive restoration from 1965 that has restored it to its very early state. Before that, the two outer windows had been walled up and the middle one had been moved up a meter and had been significantly lengthened. A buttress was added in front of the walled-up north window. On an older black and white photo, however, you can still see the location of the old arch stones. Today you can see the original three arched windows at and at the same height, but with different widths. The middle one is slightly wider than its slimmer neighbors. They are framed by simple right-angled reveal edges. The arches made of wide wedge stones are surrounded on the outside by very narrow brick slabs. The window sills are made of rectangular monolithic limestone.

On both sides of the middle window, two gemstones of early origin are embedded at about the height of the apex of the arch. These are square limestone slabs, about 25 cm on the side, which are placed on the top and divided into four small squares by two engraved lines. Nothing is known about their meaning.

In the central wall section of the choir apse there was also a small round opening, a so-called "fenestella" , which is now closed with a stone block, about one meter above the level at that time , but whose contours can still be seen. It had a special meaning then. She allowed the faithful kneeling on the outside to put their heads, or at least their hands through them, to get closer to the graves or relics that were on display in the choir room. In this way, the graves and valuable reliquary shrines could be protected from all too harmful zeal and the believers could be close to them despite the building being closed. Such fenestellas are said to have existed in a basilica in Clermont-Ferrand under Bishop St. Venerandus . The fenestella can be compared with the openings in the steps to the choir or in the walls of the ambulatory to the reliquary-filled crypt or to the Martyrion located there (relic niche that can be locked ).

The roof of the choir slopes from all eaves of the wall sections of the choir at a slight angle up to the square base of the bell tower, which rises up as part of the east wall of the nave and is covered with red hollow tiles of Roman construction, or monk-nun roof tiles. The eaves have little overhang and no rain gutters. The base of the bell tower, which is closed on all sides, extends a little below the ridge height of the nave roof and has buttresses that protrude slightly over the entire height on both sides. The base is closed on the top by a cantilever cornice with a sloping lower visible edge.

The first floor of the bell chamber follows. Two slender, round-arched sound hatches - also called sound arcades - are recessed on all sides, with simple right-angled soffit edges, without gradation, which stand directly on the cantilever cornice. The upper demarcation is much more elaborately shaped, made of a wide, cantilevered cornice with a rectangular cross-section that rests on cube-shaped corbels. The cubes are carried by animal or human heads. This lavishly carved cornice initially closed off the tower, which was then presumably followed by a gently sloping pyramid roof.

Together with the vaulting of the nave that followed in the 12th century, the bell tower was then raised by another slightly lower storey. In each of the side walls, two round-arched, not quite as slim sound hatches are recessed, the reveals of which are simply stepped at right angles. The outer arch stones are covered by a simple cantilever profile, which swings horizontally at the outer arches and is led to the corner of the tower. The top floor is closed off with a simple cantilever cornice like the tower base.

A tower spire rises above it , with a steep, pyramid-shaped, smooth roof made of limestone, the ridges of which are covered with simple profiles. It is crowned with a stone Latin cross that resembles the cross on the nave gable. Small imitations of gargoyles protrude from the lower corners of the spire.

Interior

Longhouse

The original undivided and non vaulted nave is from the 12th century in the longitudinal direction in three ships divided, of which the middle is slightly wider than the aisles. In the transverse direction it is divided into four yokes, the first of which is slightly wider than the others.

The central nave , which towers significantly higher than the aisles , is vaulted by a semicircular barrel with rectangular belt arches, the lower aisles by groin vaults . The thick partition walls between the aisles , without an upper aisle , are each supported by four slightly sharpened partition arches on six strong round supports, which are crowned by elaborately designed capitals. Strong, profiled transoms transfer the loads of the vaulting belt arches of the side aisles and the dividing arches into the supports. The belt arches of the central nave, which are arranged much higher up, stand on semi-capitals which carry their loads into the partition walls and supports via semi-circular services. The belt arches and cross ribs of the aisles stand on the capitals of the round supports.

With the subsequent vaulting of the nave, the existing buttresses would have had to be reinforced because of the additional thrust forces on the outer walls. As an alternative, however, it was decided to use five wooden tie rods , which were drawn in at the level of the supports next to the belt arches and thus could eliminate the shear forces. The anchors were also hung in the middle of the vault.

The nave was originally illuminated through two by four slender, arched windows, the walls of which are widened inward. The later addition of the rectory to the south wall meant that the two windows of the first bays had to be dispensed with. The daylight is supplemented by a somewhat larger, arched window in the west wall, which floods the ship with the golden rays of the low evening sun.

The capitals on the pillars of the ships from the 12th century are mainly figurative and colorful (painted) in keeping with the style of the time. Besides the white limestone, red and ocher tones predominate.

Common motifs are mythical creatures , such as dragons with long-bearded human heads, one of which is eating a human figure that of a damned man. The ends of the tails have snake or scorpion heads. A fleur-de-lys is depicted on a coat of arms above one of the dragon 's bodies . Another shows portraits of birds with crooked beaks and human heads or masks on the corners, while another shows a long-legged pair of birds on either side of a goblet and drinks from them. It shows the Holy Eucharist, the blood of Christ, which is drunk as wine. The scene recalls Christ's sacrifice on the cross. Two scenes on a capital show unusual themes for the Romanesque sculpture and for this place, namely the sacrament of marriage , in the form of a couple shaking hands to make a promise, and temptation , in the form of a siren , who with its charm and her melodious voice seduces a fisherman who plunges into perdition. These two scenes seem to have been made by the same stonemason as the capital of the two atlases on the triumphal arch. There are also individual capitals with purely vegetal or ornamental decorations.

The same color tones are predominantly found in the coloring of the other structural elements. The round columns show the light, almost white limestone, which is completely white grouted. Walls and vaulted surfaces have white or slightly yellow backgrounds that are painted with brown and red masonry joints. The undersides and inside of the arches bear various intricate plant decorations on white backgrounds. Narrower ribbons, like those on the vaults, are adorned with simpler plant decorations. The groin vaults are painted with relatively large, circular imitation keystones that present various ornaments. The cantilevered cornices of the vaults are painted with a jagged band pattern in red and yellow.

The painting of the constructions and the setting of the capitals date from 1861, those of the choir from 1866. They are certainly not authentic, but based on their time.

The semicircular triumphal arch between the central nave and the choir is only slightly narrower than the width of the central nave. Its fighter plates are a little higher than the fighters of the partition walls. In the wall above there is a round arched niche of medium size.

The eastern end walls of the aisles are closed. With their painting and built-in combat corners, they simulate an arcade and a final belt arch. Just below the “fighters” there is a pole painted on which a curtain of folds seems to hang on rings. In the background above the curtain you can see a painted masonry bond. Perhaps the artist wanted to show what a conceivable extension to a transept could look like, to which this passage would lead.

At the western end of the nave, in the first yoke, a wooden gallery has been drawn in across the full width of the nave, which is slightly narrower than the width of the yoke. It is supported on the walls and also on two beams that are stretched in the first yoke between the west wall and the first two columns.

Choir

Today's choir offers an unfinished picture and is made up of different building eras that do not fit together. Its six-fold kinked outer walls, at least in the lower area, are among the oldest components of the first church, which was built between the 5th and 7th centuries. A completely different nave originally belonged to it, of which no evidence has been received. It is believed that this choir apse was followed by a nave of the same width. Its current three windows are reconstructions of the original substance and illuminate the choir, especially in the morning hours. Their robes are widened inward.

A stele dedicated to Aeternalis and Servilla is walled in at about eye level under the window of the south-eastern choir wall . It is a limestone with a height of 0.54 m and a width of 0.35 m, on which the Christian monogram is engraved, consisting of an X and a Rho, the first Greek letters of the word Christos , which is from the first and the last letters of the Greek alphabet, the alpha and omega , symbols of the beginning and the end, are flanked. At the bottom of the stone you can read: “AETERNALIS ET SERVILLA VIVATIS IN DEO” (Aeternalis and Servilla, live in God) . In the early days of Christianity, such names were in use as related to their beliefs or attributes. Until 1862 this plate was embedded in the masonry on the outside above the central window. According to most historians and inscription experts, it dates to the end of the 4th or the beginning of the 5th century. Since this stele has been placed inside the apse again, it is roughly where it was when the first church was built. The red whitewash that can still be seen in the stone's engravings cannot deny that it was built near the use of red colored mortar for the masonry joints of the apse.

Apparently there is no evidence of the existence of a crypt . On the other hand, it is assumed that the choir, at least in the beginning, had the function of a mausoleum or an exhibition space for relics. This is primarily due to the placement of the fenestella in the choir axis, about one meter above the Merovingian ground level.

The building structure inside the choir, which seems strange today and was built together with the nave in the 10th and 11th centuries, is reminiscent of a crossing that still lacks the additions of transept arms and a choir apse. At the bottom it consists of four square pillars with a cross-shaped plan, which are exactly an extension of the central nave and have almost the same plan dimensions as the fourth yoke of the central nave. The side parts of the eastern nave wall are axially adjacent to its western pair of pillars.

Exactly as it is usual with a crossing , further up the square is enclosed by massive walls in the thickness of the pier cores. The west wall is at the same time the east wall of the central nave, with its triumphal arch, the height of the transoms and arches of which correspond to those of the partition walls of the nave. At the height of these warriors, a simple cantilevered cornice runs on both sides of the "crossing" on which a semicircular barrel vault rises in the longitudinal direction of the church. It is barely higher than the arch of the aforementioned triumphal arch. The vertices of the three other arches of the "crossing" are slightly lower than the base of the arch of the vault. All bows stand at their approaches on simply profiled fighters. This "structure" carries the bell tower protruding from the roof surface, which was probably once planned as a crossing tower.

Above the central triumphal arch towards the choir apse, there is a higher wall surface with a plaster painting. On a red background, which is decorated with paw crosses, two people stand opposite each other, in white robes as long as feet, whose heads are backed by nimben . It is said to be the two saints Gervais and Protais. On the outside of each of them, they carry a palm frond in their hand that is leaning up against their shoulder. The person on the left points downwards with his left hand and is probably holding a scourge, the person on the right is holding two other elongated objects, a sword and a scabbard. The nimben indicate their holiness.

The uneven space between the outer walls of the choir and the walls of the "crossing" is covered by half barrel vaults that stand up on the outside all around on a simple cantilevered cornice and lean against the walls of the "crossing" on the inside. The cornice is located slightly above the apex of the "crossing arcades". The vaults are decorated with evenly distributed plant ornaments, similar to a fleur-de-lys.

From the existing conditions, it cannot be ruled out that the planners of the Romanesque church thought of removing the “old” choir at a later date and then adding two transept arms and a “new” choir apse to the tower substructure. But it never came to that, perhaps also supported by the decline and the later drying up of the streams of pilgrims from Jacob after the middle of the 12th century.

Pre- and early Christian shrines

Dimensions (approx)

fanum north of the church:

- Length parallel to the church (outside): 18.30 m

- Width (outside): 18.10 m

- Cella (outside): 7.20 m × 7.20 m

- Cella (inside): 5.50 m × 5.50 m

- Gallery widths (inside): in the north and east: 4.00 m

- in the west: 5.30 m

- in the south: 5.80 m

fanum south of the church

- Width (outside): 12.45 m

- Length: not ascertainable, probably like the northern part

Entire sanctuary

- (Width outside, across the church): 43.00 m

Gallo-Roman sanctuary

On the north side of the Romanesque church are the foundation walls of a small Gallo-Roman temple (= fanum ) about 30 to 60 centimeters high, which was built between the 1st and 2nd centuries. They were excavated archaeologically in 1960. The antique fanum had the classic floor plan of a small square cella , which is enclosed by a gallery of different widths. It is not known whether this approach was surrounded by open rows of columns in full height, columns on parapet walls, or by partially or completely closed walls.

The visible foundation walls of the cella and those of the enclosures of the fanum are ancient substances that supported the rising ancient walls and / or rows of pillars. On the west wall of the cella and the west gallery were the entrance portals, of which two monolithic stone blocks have been preserved in the foundation area, which presumably have carried special portal frames.

28 years later it was found that the edging of the ancient fanum on the north side extends even further beyond the church, so that it extends a total of about 43 meters in north-south direction. It is noticeable that the east and west walls of the nave of the church are exactly in line with the east and west of the fanum . However, this gives rise to the assumption that most likely the foundations of the former fanum were reused to found the nave of the church.

Unfortunately, there is no information about the archaeological conditions under the church and the attached rectory. So there are different ways to speculate. At first one could assume that the only fanum to the south was connected to an uncovered and walled courtyard where the faithful could gather. A second variant would be that of a second fanum in the common enclosure. A third would be a second, almost mirror-like fanum in its own completely separate enclosure. In the last two cases the remains of a second fanum would be found under the church and the rectory.

Merovingian baptistery and cemetery in the Gallo-Roman Fanum