Indian architecture

The Indian architecture includes the architecture of the Indian subcontinent with the states India , Pakistan , Bangladesh , Nepal and Sri Lanka from the beginning of the Indus Valley Civilization in the third millennium BC. Until today. It reflects both the ethnic and religious diversity of the Indian subcontinent and its historical development.

Beginnings

Its beginnings lie in the cities of the prehistoric Indus culture , which are characterized by considerable urban planning achievements and great functionality. Monumental buildings were still completely unknown to this earliest advanced civilization on Indian soil. For reasons that have not yet been clarified, the Indus culture declined in the 2nd millennium BC. Under. A continuity to the later art historical development cannot be proven.

The Indian architecture of the historical period was primarily sacral architecture until the early modern period. The Buddhism shaped the beginning of monumental architecture, dates from the time of the Maurya -Herrschers Ashoka in the 3rd century. The stupa as the earliest cult building was followed by Buddhist temples and monasteries. With the revival of Hinduism in post-Christian times, the phase of Hindu temple architecture began, which has experienced a wide variety of stylistic characteristics depending on the region and epoch. Hindu architecture radiated to Southeast Asia in the Middle Ages , Buddhist architecture to East Asia and Tibet in ancient times , while the architecture of closely related Jainism was always limited to the subcontinent. What all three architectures have in common is a strict geometry that is derived from cosmological and astrological views. Buddhist, Hindu and Jain shrines are primarily understood as symbols of the cosmos or individual parts of it. The Hindu temple , like the Buddhist stupa, depicts the mythical world mountain Meru as the seat of the gods and can therefore be viewed as a kind of monumental large-scale sculpture. This context explains the intrinsic preference of Indian architecture for three-dimensional representation and, among Buddhists, Hindus and Jainas, the special importance of iconography .

From the Middle East , Islamic architecture came to India in the 8th century, where it developed into an independent Indo-Islamic architecture under local as well as West and Central Asian influences. The mosque , the most important Islamic structure as a place of community prayer, lacks the strong symbolism of the buildings of Indian religions. In detail, however, the Hindu influence on the sculptural stone processing cannot be overlooked. In the Mughal Empire at the latest , Islamic and Indian elements merged to form a unit that could be separated from the architecture of non-Indian Islam .

The colonialism brought in the 16th century European art ideas that initially remained largely isolated from native traditions. It was not until the end of the 19th century that an unmistakably British-Indian colonial style emerged. In the modern age, contemporary western-style architecture is just as effective as traditional building forms and innovative, independent lines of development.

Basics and general traits

Spatial concepts

The Indian concept of space is closely linked to astrological and cosmological ideas, while its pictorial structure reflects the position of people and things in the world. The Vedic architecture theory Vastu explains idealized city schemes with the following basic structure: In the center of the city there is a sanctuary reserved for the most important Vedic god Brahma , which is considered the “holiest of holies”. This expresses the notion of the world mountain Meru , which is still present in Hinduism and Buddhism today, as the center of the world and seat of the gods. Around the central sanctuary, less significant sanctuaries are arranged in concentric rings, each dedicated to a particular deity or a particular form of the divine. The deities and thus the sanctuaries are assigned to stars (sun, moon, fixed stars). The specific location of the smaller sanctuaries depends on the direction pilgrims have to follow around the central sanctuary (usually clockwise). The city is traversed by two axes based on astronomical observations: the first axis runs in an east-west direction between the equinoxes , the second in a north-south direction between the culmination points of the sun. The basic geometric shapes of square and circle, which can be represented as a mandala , or cube and sphere result from the center position and the oriented axis cross . The square has special symbolic power, as the four mythological “corner points” of India - the pilgrimage sites Puri in the east, Rameswaram in the south, Dvaraka (Dwarka) in the west and Badrinath in the north - form a square.

In fact, some cities in northern and central India have a structure that is almost comparable to the ideal case described, with axles aligned with the cardinal points and a distinctive central structure. Jaipur ( Rajasthan , northwest India) is close to the ideal , built in the 18th century as a planned city with a continuous east-west axis, an incomplete parallel street, two north-south axes, checkerboard-like side streets and the palace of the maharajah as the central dominant . However, the strict principle is more or less weakened depending on the geographical conditions. In most cities, the side streets of the major axes are winding; they are not subject to a strict principle of order. Even Islamic foundations have a similar structure, but this is based on the ideas of paradise of this religion. The axis cross is modeled on the paradise garden divided into four.

South Indian temple cities are also marked by an axilla; in addition, they are approximately square. As the city grew, the walled city center was enclosed by a larger wall. This follows the inner wall ring in shape and orientation, although the latter was usually preserved. Over the centuries, several interlocking wall squares were created, which provide an indication of the age of the city districts, comparable to the annual rings of a tree. The sides of the squares ideally run in an east-west or north-south direction. The main temple rises in the innermost square, usually the oldest building and starting point for urban development. Its architecture is also oriented towards the cardinal points and is dominated by rectangular basic structures. The districts with smaller temples all around are arranged concentrically and hierarchically. Some south Indian cities like Tiruvannamalai come extremely close to this ideal.

The ordering principles of quadrature and orientation can also be recognized in small-scale structures. The arrangement of the components of a temple is laid down in the Vastu doctrine in a similar way to the layout of a city . Traditional Indian houses are also often square or rectangular. The main entrance faces east if possible. The interiors are grouped hierarchically around a house shrine. However, there is considerable regional variation.

Construction methods and materials

In Vedic times wood was the preferred building material. Early monolithic stone buildings, such as the Hindu and Buddhist cave temples and monasteries, therefore reproduce large halls built in wood with a uniform ceiling. Ornaments, presumably modeled after wood carvings, were carved into soft sandstone . After the transition to free-standing, composite stone buildings, in some cases until the early modern era, wooden structures still served as models in many cases. Time and again, long stone beams were laid according to the wood construction method without compensating for the inadequate static properties due to the weight of the heavier building material. Collapses and subsequent corrections were therefore relatively frequent. Nevertheless, stone construction prevailed thanks to the durability of the material.

For dry masonry , which dominates regions such as the Dekkan and its foothills , which are rich in natural stone , stone blocks were cut so precisely that they could be stacked on top of one another without mortar and were able to carry heavy ceiling tiles. Lime or gypsum mortar was mainly used in the northern and northwestern part of the subcontinent, where brick is the most important building material. But also in South India the upper floors of towering temple towers are made of lighter mortar masonry. In Bengal and Sindh , clay is still used as a building material and binding agent. In the Islamic period, fast-setting, cement-like mortar mixtures made according to the Persian model provided the necessary stability for the construction of large cantilever vaults and domes. Ceiling constructions - in Indian architecture it is not common to have attached roof trusses based on the European pattern - and outer walls were also sealed with mortar to prevent water from penetrating during the rainy monsoon season . Especially with domes, the mortar layer applied from the outside gives additional strength.

The most widespread indigenous building techniques of the pre-Islamic period were the stone layering and the collaring . Although vaults and domes were already known in antiquity, they were only widely used by Islamic architects. Many outstanding Indo-Islamic buildings are domed structures. The transition from the rectangular base to the base of the dome was solved in pre-Islamic times by corner plates and cantilever constructions, later by trumpets , pendants and Turkish triangles . Vault keystones and amalakas (keystones on top of a temple tower) almost always have symbolic and / or decorative functions in addition to purely static tasks.

Stone or iron brackets and anchors , which hold the large stone blocks or entire parts of the building together, serve as auxiliary structures in buildings made of stone . Brick constructions are stabilized by wooden beams, often made of teak , connected with ring anchors . Iron or wooden tie rods are embedded in many vaults in order to counteract the thrust of the vault. Structural elements ( girders , joists , etc.) are often concealed. Externally visible ribs therefore usually have no static function; Especially in Islamic buildings they are usually pure decorative elements made of stucco .

A peculiarity of Indian architecture is the custom of providing individual structural elements or even large wall surfaces, especially in sacred buildings, with a coating of metal, glass or other shiny materials. This practice is very common in Nepal , where the wooden components of important, half-timbered temples are often covered with metal or even completely replaced by metal. The best-known example of the use of metallic building materials in facade design is the Golden Temple in the Indian city of Amritsar , the highest sanctuary of the Sikhs' religious community .

Builders and craftsmen

Little is known about the architects of important Indian monuments, especially sacred buildings of the local religions. For Hindus, Buddhists and Jainas, the focus is on the religious significance of a sanctuary, behind which the personality and performance of its builder have to take a back seat. For this reason, very few Indian architects are known by name. The distribution of tasks in the construction of a temple and the function of the architect, on the other hand , have been handed down in the Shilpa Shastra , medieval treatises on Hindu architecture. The general direction of a temple building project as a sthapaka (priest architect ) was always taken over by a respected Brahmin scholar who had to have extensive knowledge of the holy scriptures as well as a good education in the field of art and architecture. The actual construction was incumbent on the Sthapati , the actual architect, who was also a Brahmin. Subordinate to him in the hierarchy - in this order - were the Sutragrahin , often his son, as draftsman and designer, the Takshaka as the top stonemason and carpenter and the Vardhakin as his assistant. The craftsmen who carried out the construction work were organized in boxes according to professional groups . Belonging to a certain caste and thus to a certain professional group was determined by birth.

Some master builders are only known by name from building inscriptions and chronicles from the Islamic period. Islamic rulers sent famous architects from Persia and Turkey to India to instruct and teach local craftsmen, including Mirak Mirza Ghiyas, the builder of the tomb of the Mughal ruler Humayun . Muslim master builders ( mimar ) of Near Eastern origin had a lasting influence on the development of court building schools, which experienced regional characteristics through local handicraft techniques .

Architecture of prehistoric times

Indus culture

In the 3rd millennium BC The cities of the Indus or Harappa culture replaced the previous village cultures. The latter have been around since the 7th millennium BC. It is documented, among other things, in Mehrgarh ( Balochistan , Pakistan) by primitive chamber buildings made of hand-formed and air-dried mud bricks. Transitional cultures were discovered in Kot Diji on the Lower Indus and in Kalibangan in Rajasthan . In both settlements, adobe structures lie within a massive wall. After a temporary abandonment, the places were covered by larger, urban settlements.

The actual high civilization of the Indus (around 2600 to 1800 BC) comprised several hundred cities not only on the lower reaches of the Indus, but also in Punjab , the "five rivers country " now divided between Pakistan and India , in southern Balochistan and in the Indian states of Haryana , Gujarat , Rajasthan (Kalibangan in the far north) and Uttar Pradesh ( Alamgirpur in the far west). The largest centers were Harappa in Punjab and Mohenjodaro in Sindh. Lothal in Gujarat was one of the most important cities outside the industrial plain . Almost all larger settlements have a similar, strictly geometric urban structure. A citadel-like upper town in the west towers above the spatially separated, roughly parallelogram, rectangular or square lower town or residential town in the east. Monumental buildings of a sacred, cult or profane nature were apparently unknown to the Indus culture. In Mohenjo-Daro, various large structures have been designed based on archaeological findings as "priests' college", "large bath" and "granary"; However, in view of the still undeciphered writing of the Indus culture, definitive evidence for the actual purpose of the building is still lacking.

Vedic period

For reasons that have not yet been clarified, the Indus culture died out around 1800 BC. With its extinction, the clay building tradition also came to an end for the time being, although individual Harappan settlements were still inhabited until the 17th century BC. The village cultures of the following centuries are only documented by ceramics and everyday objects, structural remains have not survived.

The residential buildings of the Indo-Aryans consisted of perishable materials such as wood, bamboo or straw, and later also of clay. A city culture could only emerge again in the late Vedic phase in the 7th or 6th century BC. In the plane of the Ganges and the Yamuna . Early cities like Kaushambi (near Prayagraj ) and Rajagriha (in Bihar ) were surrounded by ramparts. The quarry stone wall of Rajagriha from the 6th century BC BC is the earliest preserved natural stone building in India. House systems from the founding time of these cities have not been preserved.

Buddhist architecture

Indian monumental architecture began in the time of Ashoka (r. 268 to 232 BC), ruler of the Maurya empire , the earliest great empire in Indian history, which in the 6th century BC. . As a reform movement from the authoritarian BC Brahmanism emerged Buddhism had accepted and promoted its dissemination. Against this background, a Buddhist sacred architecture emerged for the first time, as well as a secular architecture influenced by Buddhist iconography . The Buddhist sacred building does not serve to worship deities, but is intended either to symbolize cosmological ideas in the form of a cult building or to accommodate followers of Buddhism in the form of a monastery on the " eightfold path " to overcome suffering.

Centers of Buddhist architecture were the Maurya empire (4th to 2nd century BC), its successor empire under the Shunga dynasty (2nd and 1st century BC), the western Deccan in the area of today's Maharashtra as well as the northwest of the subcontinent with the historical region of Gandhara and the kingdom of Kushana (3rd century BC to 3rd century AD), where Buddhism has a close symbiosis with the culture of the Hellenistic world that has been widespread since Alexander the Great received ( Graeco Buddhism ). According to the Hellenistic model, it was built around the 1st century BC. The settlement Sirkap in the area of Taxila (Gandhara, today's northwestern Pakistan) with main street, right-angled secondary streets and blocks of houses in a rectangular grid.

The capital of the Maurya, Pataliputra ( Bihar , northeast India) is said to have been one of the largest cities of that time according to the description of Megasthenes . As Pataliputra is now largely under the city of Patna , so far only a small part of the ancient city has been exposed, including the remains of a picket fence . The remains of a large hall resting on monolithic sandstone pillars, the purpose of which is unknown, represent the most outstanding find.

After the fall of Kushana, sometimes even before that, Buddhism was on the decline all over South Asia with the exception of Sri Lanka , albeit with considerable regional differences in time, compared to the resurgent Hinduism. This was accompanied by a reduction in Buddhist building activity, which finally came to a standstill after the advance of Islam . The Buddhist building tradition experienced a continuation and further development outside of India, especially in Southeast and East Asia as well as in the Tibetan cultural area.

Beginning of monumental architecture

The origins of Indian monumental architecture, which began in the 3rd century BC, have not been clearly clarified, but many scientists (including Mortimer Wheeler ) attribute them to Persian influences, while the Indian archaeologist and art historian Swaraj Prakash Gupta sees an in-house development made from wood-carved forms of the Gangestal. According to the proponents of the Persian theory, after the destruction of the Achaemenid Empire by Alexander the Great in 330 B.C. BC brought the art of stone working and polishing to India. The design of figure reliefs speaks in favor of this thesis. On the other hand, the Buddhist stupas, the earliest representatives of sacred architecture, as well as early temples and monasteries, can be derived from Indian models, although many design principles were actually adopted from wood construction.

It is undisputed that the Achaemenids as early as the 6th and 5th centuries BC. BC expanded to the northwest of the Indian subcontinent. Numerous city fortifications (ramparts, ditches) in northern India date from this time. A second wave of construction of such facilities took place at the time of the Hellenistic invasions of the Graeco-Bactrians in the 2nd century BC.

The stupa as the earliest Buddhist cult building

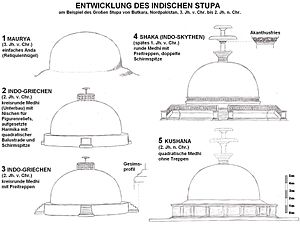

During the Maurya period, the stupa was the earliest known form of Buddhist sacred architecture. The stupa emerged from older burial mounds made of earth. Early stupas consisted of a flattened, brick-walled hemispherical building ( anda , literally "egg") filled with rubble or earth , in which a chamber ( harmika ) is set for the storage of relics , and were surrounded by a wooden fence. In addition to keeping relics, stupas were often intended to commemorate significant events in the history of Buddhism.

Most during the Maurya period in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC Stupas built in northern India and Nepal in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC were walled over under the Shunga dynasty , such as the oldest of the excellently preserved stupas of Sanchi (Madhya Pradesh, Central India). Under the stupas of Sanchi, the middle of the 2nd century BC stands out. Renewed the Great Stupa, which essentially originated from the Maurya era, and is one of the most important architectural monuments of Indian antiquity. It has all the elements that are characteristic of the later stupas. The Anda rests on a terraced circular substructure ( medhi ), which is accessible via open stairs. The harmika is no longer embedded in the Anda , but stands on top within a square stone balustrade . The conclusion is a stone mast ( Yasti ), which is derived from the central wooden bars of the earlier burial mounds, with a triple umbrella-shaped crown ( Chattra , plural Chattravali ). According to Buddhist ideas, the building as a whole symbolizes the cosmos, with the Anda standing for the vault of heaven and the Yasti for the axis of the world. The building complex is surrounded by a walkway ( Pradakshinapatha ) and stone fence ( Vedika ); the four stone gates ( Torana ) embedded in them with rich figurative decorations were not made until the 1st century BC. Or later added. The stupa of Bharhut in Madhya Pradesh also dates from the Shunga period . The Shatavahana, which ruled in what is now Andhra Pradesh , were built between the 2nd century BC. BC and the 2nd century AD. Stupas with friezes rich in pictures , among others in Ghantasala , Bhattiprolu and Amaravati .

Stupa architecture also flourished in the northwest; one of the earliest examples is the Dharmarajika stupa in Taxila in the Gandhara region of northern Pakistan, which resembles the stupas of the Maurya and Shunga. . In Gandhara also a new type of stupa developed. From about the 2nd or 3rd century AD sparked in Kushan -Reich a square base, the round Medhi , while the previously flattened hemispherical shape of the actual Stupa has now stretched cylindrical. The stupa of Sirkap near Taxila is representative of this new type. The elongated stupas found widespread use in northern India due to the expansion of Kushana. In the case of particularly large stupas, the medhi is narrower, higher and separated from the superstructure by cornices , so that the stupa appears like a multi-storey building. Stupas from the late period of Buddhism in northern India tower high, and the Anda only forms the upper end. One example is the incomplete, cylindrically elongated Dhamek stupa from Sarnath ( Uttar Pradesh , Northern India) from the 4th or 5th century.

In Sri Lanka , which, in contrast to the reinduced and later partly Islamized India, is still Buddhist today, development began in the 3rd century BC. A special variety of the stupa known as dagoba . The oldest dagobas are either preserved as ruins or were later built over. Characteristic are the mostly round stepped base, the hemispherical or bell-shaped Anda , the square harmica sitting on it and the conical tip made up of tapering rings.

The building tradition of the stupa was continued and further developed in other parts of Asia, where Buddhism is still partly established today. New forms of construction emerged from this, for example the chortas in Tibet , the pagoda in China and Japan and - via the intermediate step of the dagoba - the Thai chedi . Other variants are common in Southeast Asia.

Buddhist cave temples and monasteries

The caves in the Barabar Mountains of Bihar from the 3rd century BC BC, the era of the Maurya, represent the starting point of the monolithic cave temple architecture, which in later centuries matured into an important characteristic of all-Indian architecture. Although the Barabar caves served as a place of worship for the Ajivika sect, a non-Buddhist community, they anticipate some features of later Buddhist cave temples. The Lomas Rishi Cave consists of an elongated hall, which is adjoined by a circular chamber that served as a cult room. Both spatial forms later merged in the Buddhist sacred building to form the prayer hall ( Chaityagriha , Chaitya Hall). Among the Barabar Caves, only the entrance to the Lomas Rishi Cave is decorated with an elephant relief based on wooden models.

In the 2nd or 1st century BC The oldest parts of the monastery complex are dated from Bhaja , which stylistically stands at the beginning of the Buddhist cave temples. Bhaja is located on the western Deccan, where the main development of the cave temples took place. Here, the rectangular hall and circular chamber have already merged into the apsidial Chaitya long hall with barrel vault . A row of columns divides the hall into three naves. A small stupa rises in the apse, which, like all other structural elements, is carved out of the rock. On either side of the horseshoe-shaped entrance to the Chaitya Hall are several simple rectangular cells, each grouped around a larger central room, which in their entirety form a monastery ( vihara ). The structure described represents the basic concept of Buddhist cave monasteries in India; With a few exceptions, later systems differ only in their size, complexity and individual artistic design. The architecture of the cave monasteries evidently imitates the contemporary wooden construction, because the pillars of the Chaitya halls and the ribs of the vaulted ceilings are without any static function in caves. The external facades also often imitate wooden models that have not been preserved.

The layout of the Karla caves from the 1st to 2nd centuries AD is similar to the nearby monastery complex of Bhaja. Karla takes a special place with his rich picture decorations, which stand in contrast to the rather sparse decor Bhajas. While the columns in Bhaja are still unstructured and completely unadorned, the capitals of the finely structured columns in Karla are adorned with artistically crafted figures of lovers ( Mithuna ). The plastic decoration in the four Chaitya halls and more than 20 Vihara caves of Ajanta is perfected , which was built over a long period from about the 2nd century BC. BC to the 7th century AD. In addition to lavish relief and ornamental decorations on portals, columns and pilasters , Ajanta is famous for its wall paintings. While the Buddha is only worshiped in symbolic form in the older complex through stupas, there are numerous figurative representations in the younger caves. In Ellora only the oldest part (about 6th to 8th centuries) is Buddhist, there is also a Hindu and a Jain cave group.

See also: Buddhist cave temples in India

Free-standing temples and monasteries

In view of the high mastery of the monolithic rock monasteries and temples and the obvious borrowings from wood art, it can be assumed that the free-standing sacred architecture was made of wood in the early Buddhist phase, but has not been preserved due to the transience of the material. Remains of free-standing stone architecture from the late Buddhist period can only be found here and there. In Gandhara in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, free-standing viharas have been built since the 2nd century AD , which, like the cave viharas, consisted of monks' chambers grouped around a generally rectangular courtyard. They were mostly part of larger structures with temples, stupas and farm buildings, which today are only preserved as ruins. One of the largest monastery complexes of this type was Takht-i-Bahi in today's Pakistan. The remains of the monastery university ( Mahavihara ) in Nalanda (Bihar, northeast India), founded in the 5th century by the Gupta , later supported by Harsha and the Pala and destroyed by Muslim conquerors in the 12th century , are relatively well preserved . The main structure is the over multiple predecessors brick built Large Stupa ( Sariputta -Stupa), the steps of, terraces and Votivstupas and angle towers with sculptures of Buddha and Bodhisattvas is surrounded. Little more than the foundation walls of the Chaityas and Viharas have survived , but these clearly show that the Viharas were arranged around large courtyards - similar to the cave Viharas around central spaces. The tower-like high temples of Nalanda, some of which are still completely intact, are significant, and their cella is on the top floor.

The free-standing temple No. 17 by Sanchi also dates from the Gupta period (approx. 400) and housed a - lost - Buddha statue. The most important free-standing Buddhist building in India is the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodhgaya (Bihar, Northeast India), the place where Siddhartha Gautama achieved enlightenment. The brick temple was built in the 6th century parallel to the early form of the Hindu temple in the Gupta empire, but was modified by Burmese master builders in the 12th and 13th centuries . Its basic shape, with a central tower rising up in the shape of a pyramid on a platform and a scaled-down replica of the same at the four corner points of the platform, resembles the concept of medieval Hindu temples in the Nagara style.

See also: Buddhist temple

The stambha

Free-standing monolithic columns ( stambhas ) from the time of Ashoka, which are still completely preserved, were discovered in several places in northern India on ancient trade routes and cult sites. They contain historically very significant inscriptions ( column edicts ). The bell-shaped capitals are adorned with sculptures of individual or grouped guard animals, which have similarities to Achaemenid motifs. While the oldest capitals were rather compact, the later stambhas have elongated capitals, the abacus of which are decorated with depictions of animals and plants. The best known is the capital of the Stambha of Sarnath (Uttar Pradesh, North India) with four lions looking in the cardinal directions and the Buddhist symbol of Dharmachakra ("wheel of teaching"). It served as a model for the national coat of arms of the Republic of India .

The idea of a cult pillar has models in the oldest temples in the Near East, the Indian stambhas can be derived as a development within the region from the Vedic ritual pillar, the round mast for animal sacrifices Yupa . Buddhist stambhas set up freely in the area served to proclaim the doctrine and as an unrepresentative symbol for the worship of Buddha. In early stupas on a round base, as in Sanchi, stambhas were set up next to the buildings on the ground floor. With the development of square base zones, the pillars were erected at the corners on these platforms, especially in northwest India. This can still be seen on stupa images on bas-reliefs from Mathura and Taxila -Sirkap. Stone pillars that were once covered in stucco and ornately decorated have been excavated near 1st century AD stupas in Mingora , Swat Valley in northwestern Pakistan. The largest and most famous pillar from the Kushana period was the 28 meter high Minar-i Chakri south of Kabul in Afghanistan.

Stambhas at Chaityas (Buddhist cave temples) are preserved in front of the largest cave temple in India in Karli west of Pune - it is a pillar with a lion capital similar to the Ashoka column from the 2nd century AD - and from the same time on both sides in front of the entrance to Cave No. 3 in Kanheri in the back country of Mumbai .

Free-standing Buddhist stambhas were later no longer built, their mythological importance as a world axis was transferred to the central mast ( yasti ) erected on the stupa , which carries the honorary umbrellas ( chattravali ). For this, this symbolism was adopted by the Jainas , whose medieval temples have a manas stambha placed in front of them . The iron pillar erected in Delhi from the Gupta period around 400 is spectacular because of its material . In Hindu temples, the pillar erected in the main axis of the temple building ensures cosmogonic order.

Hindu temple architecture

The Vedic religion ( Brahmanism ) as a forerunner of Hinduism lost around the 5th century BC. Their dominant position on the Indian subcontinent to Buddhism. The religion of Jainism as well as various ascetic reform movements directed against authoritarian Brahmanism emerged parallel to Buddhism, which led to the development of Hinduism in its current form. After the fall of the Maurya Empire in the 2nd century BC Many ruling dynasties, including the Shunga , Shatavahana and especially the Gupta , increasingly turned back to Hinduism and helped it to a renaissance.

The Hindu temple ( mandir ) is - despite the large number of deities - always dedicated to a single deity, which, however, in no way excludes the fact that smaller shrines are located outside the actual sanctuary in honor of subordinate gods. The cult image of the deity is kept and venerated in a small chamber, the Holy of Holies ( Garbhagriha = mother's womb), almost comparable to the cella of ancient Greek and Roman temples. Like the Buddhist stupa, the Garbhagriha is seen as the embodiment of the heavenly. In Hindu cosmology, the sky symbolizes the square, which is why the Garbhagriha is always laid out on a square floor plan.

There was probably a rich tradition of building Hindu temples out of wood in ancient times, but - apart from isolated remains of Hindu shrines from the 3rd century in Andhra Pradesh in southern India - the transition to the Gupta dynasty was not made until the middle of the 5th century Hindu temple made of stone (see Gupta temple ). In doing so, she laid the foundation for the immense wealth of forms in Hindu temple architecture in the Middle Ages.

Since around the 8th century, the three main regional styles, which are described in the Shilpa Shastra , medieval teaching texts on art and architecture, have been distinguishable: the Nagara style in North and East India, the Dravida style in the south and the Vesara style as a hybrid of the aforementioned on the western Deccan. The Shilpa Shastra also draw a mandala of Vastu as a basic plan for the temple, the Vastu Purusha Mandala , in which the body of the Purusha is used as the personification of regional planning with bent arms and legs. In fact, the strict formal schemes of Shilpa Shastra have only partially found application in practice.

Close trade contacts between India and Southeast Asia enabled Hindu beliefs, including Hindu cosmology and symbolism, to spread to the rear of India and the Malay Archipelago in early post-Christian times . Hindu temple forms were also adopted there from Buddhist architecture. In the Funan empire in what is now Cambodia and in the Champa empire in southern Vietnam , the design of the Prasat emerged in the early 7th century . These tower sanctuaries were initially based closely on South Indian models, but from the 9th century onwards they developed increasingly independently in the Khmer Empire . From Prasat Khmer, the forwards Thai Prang off. The construction of Hindu sanctuaries, known there as Chandi , began on Java around the middle of the 8th century, also under South Indian influence. The development of the temple architecture of the Pyu and the subsequent cultures of Myanmar, on the other hand, was influenced by the East Indian Odisha .

Early temple forms in the Gupta and Chalukya empires

The oldest known form of the free-standing Hindu temple consists only of a cube-shaped, windowless, flat-roofed garbhagriha , the entrance of which is a small pillar veranda - the original form of the later temple hall ( mandapa ) - is built in front of it as protection from the weather, for example temple no.17 in Sanchi and the Narasimha Temple in Tigawa (both Madhya Pradesh, Central India) from the 5th century. Stylistically, the temples of this type are based on the older cave architecture; they were apparently only erected in places unsuitable for the creation of monolithic rock sanctuaries.

In the 6th century, a characteristic that was extremely important for the further development emerged: By extending the Garbhagriha in the vertical, this - and thus also the central cult image - should be emphasized more strongly. The tendency towards verticalization manifested itself in the construction of the Garbhagriha on a raised pedestal and finally in the crowning of the central sanctuary by a stepped tower. Both features are combined in the Dashavatara temple of Deogarh in Uttar Pradesh , northern India , built around the year 500 in honor of Vishnu on a cross-shaped floor plan , which is considered the high point of the development of the Hindu temple in the Gupta empire, although the tower is now badly damaged and the four pillar verandas, which covered the entrance of the Garbhagriha and the relief niches in the three other outer walls are no longer preserved. The square base of the temple is accessible from all four sides by stairs.

In parallel to the development in the north of India, the empire of the early Chalukya on the western Deccan showed trends towards the medieval temple styles. As a new element, the pillared hall ( mandapa ) was added to the cubic garbhagriha and merged with it to form a unit. The Lad Khan Temple, built around the middle of the 5th century in the Chalukya capital Aihole ( Karnataka , Southwest India), is the first example of this new type. The Garbhagriha leans against the back wall of the almost square assembly hall ( Sabhamandapa ), which is preceded by a smaller vestibule ( Mukhamandapa ). Sculptured pillars support the two mandapas , whose flat roofs are slightly inclined to the side. Flat roof and the unit of Garbhagriha and assembly hall, with the former either in the back of the hall or in the middle, characterize the first generation of Chalukya temples.

The Durga temple in Aihole from the late 7th or early 8th century has a veranda-like corridor ( Pradakshinapatha ) for converting the Garbhagriha and an apsidial floor plan, echoing the Buddhist Chaitya hall. Apsidial form and veranda were not continued, but the tower structure, which characterizes the younger Chalukya temples of the 7th and 8th centuries, is extremely important. Its curvilinear contour anticipates the beehive-shaped temple tower ( Shikhara ) of the north Indian Nagara style, without the Chalukya temples themselves being assigned to the Nagara type. The temple tower appears in a similar form at the Huchchimalligudi temple, among others. The disk-shaped, ribbed keystone ( amalaka ) and the vase-like tip ( kalasha ) have also been preserved on the Chakragudi temple from the 8th century - they too later characterize the Nagara temple.

At the same time the development of a pyramidal stepped temple tower ( vimana ) in the early Dravida style begins , which is probably due to the influence of the Chalukya by the southern Pallava dynasty. Examples of this are the early Malegitti Shivalaya temple from the first half of the 7th century and the more mature Virupaksha temple from the middle of the 8th century in Pattadakal (Karnataka, Southwest India).

Dravida style

As the first of the medieval Hindu temple styles of India, the South Indian Dravida style appeared. The starting point was the monolith temples of the Pallava dynasty in Mamallapuram ( Tamil Nadu , South India), which were carved out of granite rocks in the first half of the 7th century . Of particular architectural importance is the group of Pancha Ratha ("five Rathas "; a Hindu temple that reproduces a processional float is called Ratha ), in which various designs were experimented with. While the attempts to transfer wooden shrines with protruding thatched roofs and temples with an apse-shaped barrel roof based on the model of the Buddhist Chaitya hall into stone construction were not continued at a later time for structural or religious reasons, the Dharmaraja- Ratha gives some of the basic features of the Dravida- Temple before. It consists of a pyramid-shaped, stepped tower with a hemispherical end ( stupika ) built on a square floor plan above the still inconspicuous Garbhagriha . This type of temple, known as Vimana , symbolizes the world mountain Meru , on which, according to Hindu mythology, the gods are at home. Accordingly, the Vimana is "populated" by a large number of figures of gods, and symmetrically arranged miniature shrines adorn it. A second basic design of the Dravida style is indicated in the Bhima- Ratha : its barrel roof on an elongated rectangular floor plan will later become part of the monumental gate tower ( gopuram ), which marks the entrance to the south Indian temple district. The Bhima- Ratha , like the Sabhamandapa of early Chalukya architecture, is derived from the assembly hall, but in contrast to this it is spatially separated from the actual temple. The pillars on which the barrel vault rests are characteristic of later buildings, although they have no supporting function in the monolithic structure.

In the late 7th century, the forms tried and tested in monolithic construction were transferred to the structured open-air structure, for example to the Kailasanatha Temple in Kanchipuram (Tamil Nadu), the upper floors of which are made of lighter stone than the foundations to relieve the lower ones - a technique that in the Dravida architecture was used again and again. Around the stepped pyramid-shaped, square Vimana with hemispherical, hood-like keystone and attached tip, as well as the originally free-standing mandapa , which was later connected by an additional hall, is now an enclosing wall, which is broken through by a gate in the east. A small, stepped tower on a rectangular floor plan with a transverse barrel roof rises above the gate. The gables on the front sides of the barrel roof contain arched niches ( kudu ) which, like the floors ( tala ) of the tower, are sculptured. The gate tower described is the prototype of the gopuram . Even under the chola , which ruled south India from the 9th century , the basic concepts of vimana and gopuram initially remained almost unchanged, while the size and decoration of the vimanas gradually increased to monumental proportions. The highlight of this development is the Brihadishvara Temple in Thanjavur from the early 11th century with a two-story Garbhagriha and a 14-story tower roof.

Also under the Chola, whole temple cities of sometimes enormous proportions began to develop through ever new and larger foundations. The actual temples were supplemented by numerous outbuildings such as shrines for subordinate deities, priests' homes, assembly halls, temple schools, rest houses for pilgrims and bazaars. Ever larger enclosing walls, which lie concentrically around the central sanctuary, had to protect the growing temple complexes. Outstanding examples are the cities of Chidambaram , Madurai , Srirangam and Tiruvannamalai (all in Tamil Nadu). In total there are more than 70 such temple cities in Tamil Nadu alone; there are also a few in southern Andhra Pradesh and Kerala .

Along with the growth of the temple cities, in the late Chola period, around the 12th century, even more under the Pandya dynasty that followed in the 13th century , the vimanas regressed for unknown reasons in favor of the now towering gopurams . Art historians have tried to explain the process of transferring the Weltenberg idea from the holy of holies to the gate tower, which is irrational from a religious point of view, by saying that Hindu rulers tried to surpass their predecessors in splendor without, however, wanting to change the central temple or being able to expand it due to lack of space . Against this, however, speaks that some temple cities with small vimana and emphasized gopurams were completely redesigned and laid out. The slim, sometimes slightly concave gopurams with several small tips attached to the barrel roof dominated the younger Dravida style until its end in the 18th century. For the construction, the South Indian architects increasingly used fired bricks instead of the heavier natural stone for the upper floors. Sculptors decorated the facades of the gopurams , like those of the Vimanas before , with numerous figures of gods and miniature shrines made of terracotta or stucco , which smooth the staircase shape of the towers. Late gopurams were also painted in bright colors, for example in the complex of the Minakshi Temple in Madurai, which was largely built in the 16th and 17th centuries. In place of the rather modest twelve -pillar mandapas common among the Pallava, there were lavishly decorated 100- and 1000-pillar halls, usually flat-roofed and free-standing.

Nagara style

A century later than the Dravida Temple of the South, in the 8th century, the stone Hindu temple in Nagara style was built from older bamboo structures in the east Indian coastal region of Odisha . Later it appears in various regional forms in the entire northern half of the Indian subcontinent. Its main feature is the tower ( Shikhara ) above the Holy of Holies, which is not pyramid-shaped and tiered like the South Indian vimanas , but rather convexly curved and with a smooth contour in elevation , comparable to a beehive. The arching lines of the Shikhara are not real arches , but cantilever structures . Some of the Chalukya temples of Aihole and Pattadakal in particular served as models, but also the more mature ones of the north Indian Gupta temples of the 5th and 6th centuries such as the Dashavatara temple of Deogarh. In common with the Dravida Temple, the Shikhara has the symbolic embodiment of the world mountain Meru and the simple, cell-like cube shape of the Garbhagriha in the center.

The Parasurameshvara Temple in Bhubaneswar (Orissa, East India) from the early 8th century represents the early Nagara style . Here to the east of the Garbhagriha there is a meeting hall corresponding to the Sabhamandapas of the Chalukya, which in Orissa is called Jagamohan , but unlike the Chalukya it forms a clearly separated unit. At the Parasurameshvara Temple, the Jagamohan , like the Chalukya Temple, is closed off by a flat roof that slopes slightly to the side.

The Nagara style of Orissa is fully developed in the Lingaraja Temple, also built in Bhubaneswar around the year 1000, whose floor plan was elongated by adding further halls. In the west is the Garbhagriha , open to the east , above which the Shikhara towers. This is followed in a west-east direction by the Jagamohan , a dance hall ( Nat-Mandir ) and a sacrificial hall ( Bhog-Mandir ). All rooms, including the Garbhagriha , are laid out on a square floor plan. The Shikhara has the usual convex curvilinear shape; this tower shape is called Rekha-Deul in Orissa . It rests on a cube-shaped ground floor ( Bada ), inside of which the Garbhagriha is hidden. There are further chambers inside the curvilinear upper floors. The upper end of the Shikhara is formed by a large, disc-shaped keystone with vertical ribbing ( amalaka ) and above it a vase-shaped tip ( kalasha ) , which is typical for the Nagara temple . Likewise typical of the Nagara style are the pilaster- like risalites ( paga ) that rise along the outer facade of the tower from the floor to below the amalaka . The Jagamohan is crowned by a pyramid-shaped step tower ( Pida-Deul ) like the South Indian Vimana , as is the Nat-Mandir and the Bhog-Mandir . The height of the towers decreases from west to east, so that the holy of holies with the central cult image is most strongly emphasized. The outer walls are covered with elaborate sculptures and reliefs. The Jagannath Temple in Puri from the 12th century has a similar structure. In the case of smaller temples, the nat mandir and the bhog mandir are usually omitted , as is the case with the Mukteshvara temple in Bhubaneswar from the 10th century, which is characterized by a massive, free-standing portal with a round arch , which is rare in Hindu temple architecture .

The Nagara style of Orissa experienced a last heyday and at the same time its climax in the middle of the 13th century with the Surya temple in Konark , which exceeds all earlier temples in size. It depicts the heavenly chariot of the sun god Surya , as illustrated by stone wheels on the substructure of the building and draft horse sculptures. The jagamohan , which, like its predecessors in Bhubaneswar, is roofed by a terraced pida , and the shikhara , of which only remains have been preserved, stand on a high plinth . The Nat-Mandir , also only preserved as a ruin, stands in the axial direction of the other two buildings, but unlike earlier halls, it stands separately on its own base.

In parallel to the development tendencies in Orissa, the Pratihara dynasty, which ruled large parts of northern, western and central India from the 8th to 11th centuries, built small temples with curvilinear Shikhara in relation to the size of the temple, following the building tradition of the Gupta Base. Later an open pillared hall ( mandapa ) was added. Most of Pratihara temples fell victim to the Islamic invasion of northern India by Mahmud of Ghazni in the 11th century or later waves of Muslim destruction. Among other things, the Surya Temple of Osian ( Rajasthan , northwest India) from the 8th century has been preserved as one of the oldest Pratihara temples with Shikhara and Mandapa .

The temple construction was continued in north central India; it reached full bloom in Khajuraho ( Madhya Pradesh , Central India). The perfect form of the temple group built there in the 10th and 11th centuries suggests a comparison with the mature Orissa temples of the same era, because there are some differences between these and the regional variant of the Nagara style in Khajuraho. While the individual halls in Orissa are loosely connected to one another, in Khajuraho the sanctuary and the main hall ( Mahamandapa ) merge into one unit on the floor plan of a double cross. Inside, Garbhagriha and Mahamandapa are separated from each other by a short space ( Antarala ). The Garbhagriha is surrounded by a processional passage ( Pradakshinapatha ) for the ritual around the sanctuary, through which balcony-like openings in the outer wall can be reached. At the Mahamandapa a small entrance hall (hugs Arthamandapa ) to. In larger temples there can be another mandapa between the two . All of Khajuraho's temples stand on unusually high plinths, which are accessible via stairs to Arthamandapa , and, unlike the temples of Orissa, are not walled. The Shikhara has the beehive shape typical of the Nagara style, ending with the Amalaka and Kalasha . The risalites on the outer wall of the Shikhara , called Urushringas in Khajuraho, are also present at the later temples, but do not lead to the Amalaka like the Orissas Pagas . Rather, they represent scaled-down repetitions of the Shikhara . While the Shikharas of the early Khajuraho temples from the 10th century are still in one piece, the number of Urushringas and with it the complexity of the temple towers increased over time. The pinnacle of the development from the one-part to the multi-part Shikhara is the Kandariya Mahadeo Temple from the middle of the 11th century, when construction activity in Khajuraho ceased after only around 100 years.

Nagara temple construction was continued until the 13th century under the Solanki in Gujarat (West India). Features are the multi-part Shikhara of the Khajuraho type and the outwardly open, more pavilion-like than hall-like mandapa with a pyramidal roof, which, unlike in Orissa, does not consist of horizontal terrace steps that are set back with increasing height, but of towering miniature pyramids. The floor plan of the roof is also mostly octagonal. A significant example is the ruins of the Surya Temple of Modhera from the first half of the 11th century. From the 13th century onwards, the permanent Islamic domination of northern India resulted in hardly any significant Hindu temple buildings in the Nagara style.

Vesara style

In the Middle Ages, a third important temple style emerged on the western Deccan. Initially, Dravida temples were built in the southwest of the Deccan under the rule of the Ganga dynasty, which lasted until the early 11th century, and were still mainly influenced by the Pallava, while the Rashtrakuta, who ruled in the northwest of the Deccan, continued to maintain the cave temple architecture. It was only when the Chalukya drove out the Rashtrakuta in the late 10th century that elements of Nagara and Dravida architecture were mixed in the Vesara style, the name of which is derived from the Sanskrit word वेसर vesara “mixture, crossing”. Although it did not produce any fundamentally new structural elements, it is based on its own principle of order, which does not justify an assignment to either the Nagara or Dravida style.

The earliest Vesara temples from the 10th and 11th centuries are still heavily influenced by the Dravida style, but their towers already show a greater tendency towards the vertical, comparable to the Shikharas of the Nagara style. In the Mahadeva Temple from 1112 in Ittagi (Karnataka, Southwest India) the transition from the eclectic mixed style to the independent Vesara style has been completed. The Vesara temple experienced its full expression at the time of the Hoysala from the 12th to the 14th centuries. The grouping of up to five Shikharas around a square mandapa is characteristic - a clear contrast to the axial arrangement of the temple buildings in the Nagara and Dravida styles. The Shikharas are usually based on a star-shaped floor plan, which results from the rotation of several squares lying one inside the other within a circle. Again, the most important geometric shapes of Hindu cosmology, square and circle, symbolize the earthly and the heavenly. One of the best preserved examples of the mature Vesara style of the Hoysala period is the Keshava temple in Somnathpur (Karnataka), completed in 1268 . It comprises three Garbhagrihas with Shikharas on a star-shaped floor plan, which are grouped around a small central mandapa . In front of this is another, much larger mandapa , so that a cross-shaped floor plan results for the entire temple. In the structure of the Shikharas , the symbiosis of Nagara and Dravida styles comes to the fore most clearly: they consist, comparable to the Shikharas of the north and the Vimanas of the south, of a base in which the Garbhagriha is hidden, the actual tower and a keystone with tip. In outline, like the North Indian Shikhara, they strive upwards in a parabolic manner , but like the South Indian Vimana are tiered by superimposed, horizontal planes. The end is formed by a hood divided into amalaka- like, ring-shaped segments and an attached tip - a superimposition of the north and south Indian keystone types. The outer walls adorn artfully designed figure friezes in the lower area. The temple complex is surrounded by a wall, on the inside of which there are numerous small shrines. The temples of Belur and Halebid (both Karnataka) are other significant examples of Vesara architecture .

Cave temple

The resurgence of Hinduism in the Gupta period not only contributed to the emergence of the Hindu temple, but also to the continuation of the cave temple architecture begun by the Buddhists . The early Hindu cave sanctuaries of Udayagiri (Odisha, East India) from the 4th century have a garbhagriha carved into the rock , with a porch made of stone pillars in front of the entrance. This design was taken up by the above-mentioned free-standing cube temples, such as those in Sanchi and Tigowa, on the one hand, and by the builders of later cave temples on the other.

The Badami caves (Karnataka, Southwest India) from the 6th century show an expanded structure . Here lies a pillared mandapa between the pillared veranda, which is now also carved out of the rock, and the Garbhagriha . In the later Mahesha Cave of Elephanta , an island off the coast of Maharashtra (West India), the Garbhagriha is not located outside, but in the east of a considerably enlarged mandapa with a cruciform floor plan, which is reminiscent of the floor plans of Gupta-era temples.

In Ellora ( Maharashtra ), one of the most important sites of Hindu cave and rock architecture since the second half of the 6th century, the basic shape of the cave temple consists of a transverse hall, separated from the anteroom by columns and thus veranda-like, to which this in turn extends Columns separated Garbhagriha surrounded by a Pradakshinapatha connects. There is another small room on each of the narrow sides of the hall. In addition to the "veranda type", two other types can be distinguished in Ellora from the 7th century onwards, which take their models from the open-air building. The first type is similar to the construction of old Indian courtyard houses. It is characterized by an elongated hall, which is divided by colonnades into a courtyard-like front area and a rear area reserved for the Garbhagriha . The second type appears from the late 7th century and is based on the free-standing temple that has since emerged. Like the temples of the early Chalukya, it includes a temple hall ( Sabhamandapa ) and a small entrance hall ( Mukhamandapa ) in addition to the Garbhagriha .

The Kailasanatha Temple of Ellora, which was begun under the Rashtrakuta in the second half of the 8th century, occupies a special position. Although it is not a cave structure, but a free-standing temple entirely carved out of the rock, it had to be adapted to the peculiarities of the monolithic construction. The Garbhagriha is towered over by a South Indian Vimana and opens up to the square Sabhamandapa , which can be accessed from the other three sides through a Mukhamandapa . A bridge connects this actual temple with a smaller shrine. Both the temple and the shrine rise on basement floors that have not been hollowed out, but are massive to support the weight of the superstructures. Another bridge connects the shrine with a gopuram . The Kailasanatha temple is stylistically attached to the Chalukya temples in Pattadakal (Karnataka, Southwest India), which were shaped by the Dravida style of the Pallava period . It is the largest rock temple in India and at the same time the highlight of Indian monolith architecture, which existed until the 12th century, but no longer produced any comparable works.

See also: Hindu Cave Temples in India

Regional temple styles

Due to special geographical and climatic circumstances, the scarcity or availability of certain building materials as well as local and non-Indian influences, a considerable variety of regional Hindu temple styles has developed apart from the known Nagara, Dravida and Vesara designs. Since a detailed treatment would go beyond the scope of this article, only the most important regional styles of the Himalayan region, the Malabar coast and Bengal will be considered.

Kashmir and Nepal

In Kashmir (northern India), Hindu temples, such as the Sun Temple in Martand from the 8th century, were built as a tower within a square walled courtyard derived from the Buddhist Vihara . The Garbhagriha was closed off with a lantern ceiling made up of squares placed one on top of the other, shrinking towards the top . Such lantern ceilings are also known from major style Indian temples, where they are mostly found in mandapas . Instead of the shikharas common in northern India , Kashmiri temples have towers made of tented roofs one on top of the other - possibly a local adaptation to the masses of snow in the Himalayas that these roofs have to withstand in winter. In addition, traditional Kashmiri houses have similar roof shapes to this day. Above the entrances to the temples there are gables with decorative surfaces, very similar to the tympanum known from European architecture . While the sun temple of Martand has only survived as a ruin, the very small Shiva temple of Pandrethan , which lacks the surrounding courtyard, from the 11th century still gives a complete impression of this architecture. The mandapa known from other parts of India is completely absent in Kashmir; however, lay Doric and Ionic columns capitals a long after-effects of the Greek-influenced art of Gandhara close.

While the predominance of Islam in the Middle Ages and early modern times interrupted the continuity of Hindu architecture in Kashmir for centuries, a similar tradition of temple building has been preserved in Nepal . Here two or three, in extreme cases up to five pyramids were stacked on a square ground floor to form towers with overhanging roofs. Wood is typically used for the upper floors and brick for the substructure. The Nepalese temple is reminiscent of the style of Chinese pagodas , which in the past was often attributed to Chinese influences. However, it should be noted that the Chinese pagoda itself had its origin in the Indian stupa, so it is more likely that the pagoda style spread from Nepal to China and not the other way around. The mandapa is also unknown as a component in Nepal . The two main works of the Nepalese pagoda style are the Kumbeshwar Temple in Lalitpur and the Nyatapola Temple in Bhaktapur . The former was built as a two-story pagoda in the 14th century and expanded into today's five-story tower in the 17th century. The Nyatapola Temple was built at the beginning of the 18th century on a high, stepped base, to which a staircase flanked with figures rises.

Bengal

The invasion of Islam had devastating consequences for the Hindu architecture of the north Indian plains. In the 11th century, countless sanctuaries fell victim to the raids and lootings of Mahmud of Ghaznis , and later Muslim rulers also had Hindu temples destroyed. In the 13th century, the Muslims settled permanently in the Ganges plain and permanently prevented the further development of the Nagara style. When Hindu building activity began to revive after the fall of the Mughal empire , the builders either oriented themselves to the Dravida style, which was unaffected by Islam in southern India, or to regional traditions of secular architecture.

In Bengal, a temple style typical of the region emerged from the construction of traditional wooden or bamboo houses in the middle of the 17th century. The Bengali temple usually has a square floor plan. The main feature is the convex curved roof, with two forms being distinguished. The Chala roof, also known as the Bengali roof , is a ridge or vaulted roof on a rectangular floor plan, the boundary lines of which are all convexly curved. It is also known as a domed keel-bow barrel. On the Keshta Raya Temple in Bishnupur ( West Bengal , East India) built in 1655 , two Chala roofs were placed side by side, one roof covering the Mandapa and the other the Garbhagriha . Here, too, the roofs, eaves and verges are convexly curved. This variant is known as Jor Bangla ("twin roof"). There are other variants with four or eight combined Chala roofs. The second roof shape is the square, arched Ratna roof, the eaves edges of which in turn correspond to convexly curved arches. The simplest version of the Ratna roof has a central tower. In the Shyama Raya Temple from 1643 in Bishnupur, the central tower is surrounded by four smaller corner towers. The large Kali temple of Dakshineshwar (West Bengal) , built in the middle of the 19th century, even has eight corner towers. What all Bengali temples have in common are the particularly solid walls, arched portals and facades that are strongly structured by pilasters due to the static effect of the roofs . Since Bengal is poor in natural stone deposits, the temples were usually built from brick and mortar. The facades were clad with terracotta , which is why the Bengali temples of this type are also known as "terracotta temples".

Another Bengali special form are the vaultless and almost tower-like towering Rekha-deul temples, whose original form originated in Odisha ( Bhubaneswar ).

Malabar Coast

On the Malabar coast in the extreme southwest of the Indian subcontinent, the Dravida style of the late Chola period spread from around the 13th century , after which temples with gopurams and several mandapas were built. However, the individual temple buildings here retained a number of architectural peculiarities that distinguish the architectural style of the Malabar coast from the Tamil Dravida style. The central sanctuary ( srikovil ) of the temple complex, which consists of several free-standing structural elements, can have an apsidal or even round floor plan in addition to the usual square or rectangular shape, which is completely foreign to other regions of India. Usually only the foundations were made of stone, but the superstructures were made of wood, which is available in sufficient quantities on the originally densely forested Malabar coast. Depending on the underlying geometric shape, the temples were covered with a protruding hipped , saddle , tent or conical roof with an attached tip. In the case of larger temples, two or three such upwardly tapering roofs are placed on top of each other. The gable and eaves were carved. As in the Himalayas, there is a certain similarity to the roof shapes of East Asian architecture, but this can be explained as an adaptation to the particularly heavy monsoon rains on the Malabar coast.

Jain architecture

The Jainism emerged as the Buddhism as a reform movement from the Brahmanism . Its founder Mahavira lived in the 6th century BC. He is considered the last of the 24 tirthankaras ("ford preparers"), the spiritual fathers of this ascetic religion, whose most important principles are absolute non-violence, the renunciation of unnecessary worldly possessions and truthfulness.

general characteristics

From the beginning, Jain sacred architecture adopted the concepts and forms of construction developed by Buddhist and later Hindu master builders. A Jain temple therefore hardly differs from a Hindu temple in the same region. Jain sanctuaries with a very similar structure can also be found at some sites of early Hindu cave architecture, for example in Udayagiri ( Odisha , East India) and Badami ( Karnataka , southwest India). In Ellora ( Maharashtra , Central India) there are several Jain cave temples, the structure of which with Garbhagriha , Sabhamandapa and Mukhamandapa is similar to that of the Hindu temples. However, the pillared halls are more complicated in plan, and sculptures of the Tirthankaras take the place of depictions of Hindu deities . In the south Indian open-air building, the essential features of the early Dravida style with emphasized vimana were adopted from the late Chalukya temple. Shravanabelagola (Karnataka) is the most important Jain sanctuary in South India.

However, the Jaina temple serves a different purpose than the Hindu temple, because in it no deity is worshiped or divine assistance is sought, but the Tirthankaras and their spiritual achievements are commemorated. Accordingly, the Jaina temple deviates from its architectural models, especially in the individual design. In contrast to Hindu temples, the exterior is mostly sober and unadorned, while inside there is hardly any area left with exceptionally detailed stone carvings. For outstanding sanctuaries, not granite or sandstone was used, as is common in Hindu temples , but white marble . This shows the wealth of the Jaina community, because because Jainas are not allowed to do physical work due to their religious commandments, they mainly specialized in commercial professions. In the form of temple donations, they contributed to the sumptuous furnishings of many temples.

Jain temple style from Rajasthan and Gujarat

Luna Vasahi Temple (13th century) in Mount Abu (Rajasthan), floor plan:

1 - Garbhagriha 2 - Gudhamandapa 3 - Mukhamandapa 4 - Rangamandapa 5 - surrounding wall 6 - pillars |

The most important centers of Jainist building activity are in Rajasthan (northwest India) and Gujarat (West India), where a Jain temple style developed from the regional variant of the Hindu temple since the 11th century. The Garbhagriha (also called Mulaprasada here ) is, like in the Hindu temple, a small, square room in which there is a statue of the Tirthankara , to whom the temple is dedicated. It opens to the east or west to an equally square, massive assembly hall ( Gudhamandapa ), which in turn is preceded by a light-flooded entrance hall ( Mukhamandapa ) that is open on all sides . The conclusion is a large dance pavilion ( Rangamandapa ) with a colonnade, which stands a little lower than the vestibule. Together, these four structural members form the central temple, the rectangular floor plan of which is extended to a cross by portals protruding to the north and south. The temple rises on a platform in the middle of a walled rectangular courtyard. Along the inside of the surrounding walls, small, domed shrines containing Tirthankara sculptures are lined up with porticoes built in front of them. This type is represented by the three most important of the Dilwara temples of Mount Abu (Rajasthan): the Vimala Vasahi temple from the 11th, the Luna Vasahi temple from the 13th and the unfinished Pittalhar temple from the first half 15th century. Her sculptural decorations on columns, ceilings and walls are among the most important creations of Indian sculpture. The Garbhagrihas were closed by low pyramid roofs, as they are known from the West Indian mandapa .

Adinatha Temple (15th century) in Ranakpur (Rajasthan), floor plan:

1 - Garbhagriha 2 - Rangamandapa 3 - Meghanadamandapa 4 - corner shrine |

A second Jain temple type emerged from the type described, the simple basic structure of which can be seen at the Parshvanatha temple of Mount Abu from the 15th century. Here the garbhagriha is open in all four directions. The Tirthankara statue looks four-faced in all directions ( Chaumukha type). There is a tiny vestibule in front of each opening, so that the floor plan is a Greek cross. The Rangamandapa is octagonal and stands free. The latter and the three-storey main building are surrounded by a wide, covered porch with pillars. In contrast, the surrounding wall is completely missing.

In addition to Mount Abu, the holy mountains Girnar near Junagadh and Shatrunjaya near Palitana (both Gujarat) are among the most important pilgrimage sites of the Jainas. City-like complexes of several hundred temples and shrines each were built on both mountains. In Palitana a large temple and several smaller sanctuaries surrounding it are combined into a rectangular walled unit ( tuk ). Although the older temples date back to foundations from the early 13th century, today's buildings date from the 16th to 19th centuries, as the original complex was destroyed several times by Muslim invaders in the Middle Ages. Stylistically, the temples are characterized by Shikhara towers adopted from the Hindu Nagara style and pyramid-shaped covered vestibules ( mandapas ). Both the axially arranged type of the Dilwara temples of Mount Abu and the Chaumukha type can be found. Unlike Palitana, the temple complex on the Girnar was spared Muslim attacks. The oldest structures, including the Neminatha Temple, date from the 12th century. The 13th century Parshvanatha Temple stands out from other temples due to its unusual floor plan. It consists of a main building, the garbhagriha of which is crowned by a Shikhara , a rectangular mandapa and two domed shrines to the north and south, which, like the later Chaumukha temples, are open in all four directions. The overall floor plan resembles a clover leaf.

Jain temple architecture reached its climax with the Adinath Temple of Ranakpur (Rajasthan) from the 15th century, in which the two types of temples described are combined into a complex complex. The main building corresponds to the Chaumukha type with a cross-shaped Garbhagriha . Each of the four openings of the Garbhagriha has a rangamandapa and a three-storey meghanadamandapa ("high hall") built in front of it, so that an axis cross is created. All Meghanadamandapas are open pillared halls and are connected by further halls with a total of four shrines at the corners of the temple. As with the first type of temple on Mount Abu, there is a surrounding wall with smaller shrines and porticos built in front of it. In total, the huge temple comprises 29 halls and five shrines, the latter symbolizing the five sacred mountains of Jain mythology. While the halls are überkuppelt, the roofed Garbhagriha a Hindu Nagara temple style borrowed Shikhara -Turm with rising up to the outer wall projections ( Urushringas ) and balconies. Although all structural elements of the Adinatha temple can also be found in the same or similar form in Hindu temples, the spatial distribution is completely different.

Islamic architecture

→ Main article: Indo-Islamic architecture

→ Main article: Mughal architecture

The Indo-Islamic architecture has its beginnings in the 12th century. The influence of Islam on the Indian subcontinent began in the early Middle Ages, but major construction activities only began with the subjugation of the north Indian Ganges plain by the Ghurids in the late 12th century. The Indo-Islamic architecture is originally based on the sacred architecture of Muslim Persia , but from the beginning shows Indian influence in stone processing and construction technology. Islam also brought new forms of construction from the Near East to India, above all the mosque and the tomb . Two types of decorative elements are also conspicuous in Indo-Islamic architecture: the flat, often multi-colored wall decorations in the form of tiles, tiles and inlays, and plastic sculptures of non-Islamic, Indian origin, from the Near East.

The main styles of Indo-Islamic architecture are the styles of the Sultanate of Delhi in northern India from the late 12th century and the style of the Mughal Empire from the middle of the 16th century. In parallel to the styles of the Mughal Empire and the Sultanates of Delhi in northern India, various regional styles developed in smaller Islamic empires, especially in the smaller empires on the Deccan in southern India, which had gained independence from the northern Indian empires from the 14th century on. All styles of Indo-Islamic architecture have in common a concept largely based on Persian and Central Asian models and, depending on the epoch and region, a differently pronounced degree of indification of the decor and construction technology.

From the early modern period, Persian and Indian-Hindu elements finally merged into an independent style that clearly differs from Islamic architecture outside of India. The Taj Mahal, completed in 1648, is considered the highlight of Indo-Islamic architecture . Indo-Islamic architecture ended with the decline of the Islamic empires in India and the rise of the British to colonial power on the subcontinent in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. However, elements of Indo-Islamic architecture can occasionally be found in the eclectic colonial style of British India and in the modern Islamic architecture of the states of South Asia.

Sikh architecture

Towards the end of the 15th century, Guru Nanak Dev, now venerated as a saint, formed a reform movement that was directed against certain Hindu beliefs and practices. The monotheistic religion of Sikhism , which today is particularly widespread in Punjab in north-west India, arose from it through Islamic influences . One of the most important principles is the strict rejection of the Hindu caste system , which divides people according to their social origin.

The place of prayer of the Sikhs is called Gurdwara ("Gate to the Guru "). Historical gurdwaras are mostly located in significant places in the history of the Sikhs, for example in places where one of the ten human gurus lived or worked. The central component of a Gurdwara is always a large hall in which a copy of Guru Granth Sahib , the Sikh holy scripture venerated as the eleventh Guru, is kept and in which the believers gather for communal devotion. Another important feature is the kitchen, often a separate building in which all visitors to the sanctuary can receive free food. A large number of other buildings, including residential and functional buildings, were often built around important Gurdwaras . Fixed schemes for the construction of a Gurdwara do not exist, rather there are Gurdwaras with very different outlines and outlines. Larger sanctuaries usually have two floors, but there are also tower-like buildings with up to nine floors. The formal language of the sacred architecture of Sikhism, which even combines Hindu and Islamic ideas, represents an eclectic mix of Indo-Islamic and Rajput architectural elements . Most Gurdwaras have a cupola, often in the Mughal style with outer ribs and lotus tip. Pointed, pointed and round arches as well as pietra dura mosaics with floral motifs also come from the Indo-Islamic building tradition. Ornamental pavilions ( chattris ) on roofs or towers, window bay windows, ornamental friezes, tracery ( jali ) as window or balustrade decoration and protruding, partly console-supported eaves ( chajjas ) go back to Rajput origins . Artificially created ponds are used for the ritual washing of the faithful. Since Gurdwaras are in principle open to all people regardless of belief or status, they have a doorless entrance on each side. In addition, they lack a strict demarcation from the outside, as is the case in mosques through the courtyard that is not visible from the outside or in Hindu temples through the surrounding wall of the temple complex.

The most important Gurdwara is the Harmandir Sahib in Amritsar (Punjab, Northwest India), also known as the " Golden Temple " because of its elaborate gilding . The current building dates from 1764 and was sumptuously furnished in the early 19th century. It is located on a platform in the middle of a rectangular pond. A shallow dam connects it with the jagged arched main gate of the complex. The temple itself is built on a hexagonal plan and comprises three floors. Stylistically, he follows the late Mughal style with Rajput influences. The low dome on the recessed, square third floor is ribbed and has a lotus blossom-like tip. The console-supported, protruding flat roof of the second floor is adorned by four chattris , whose domes repeat the main dome. Indo-Islamic floral decor characterizes the Pietra-dura inlay work in white marble on the facade of the ground floor, while the upper area is completely gilded.

Secular architecture of the pre-colonial period