Commodore 128

| Commodore 128 | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Manufacturer |

|

| Type | Home computer (C64 mode) Office computer (other modes) |

| publication |

|

| End of production | 1989 |

| Factory price |

|

| processor | 8-bit MOS Technology 8502

8-bit Zilog Z80A (CP / M mode)

|

| random access memory | 128 kB RAM (max. 640 kB) 16 kB VRAM (C128, C128D) 64 kB VRAM (C128D-CR) |

| graphic | 8-bit MOS 8564 (NTSC) 8-bit MOS 8566 (PAL-B) 8-bit MOS 8569 (PAL-N)

8-bit MOS 8563 (C128, C128D)

8-bit MOS 8568 (C128D-CR)

|

| Sound | 8-bit MOS 6581 (C128, C128D) 8-bit MOS 8580 (C128D-CR)

|

| Disk | 5¼ inch floppy disks (DS, DD) 3½ inch floppy disks (DS, DD) compact cassettes plug-in modules |

| operating system | Commodore BASIC V2.0 (1981) Commodore BASIC V7.0 (1985) CP / M-Plus Version 3.0 (1985) GEOS 128 (1986) |

| predecessor | Commodore 64 (1982) Commodore Plus / 4 (1984) |

| successor | Commodore 256 (not ready for series production) |

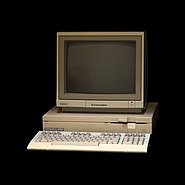

The Commodore 128 (short- C128; colloquially " Hundertachtundzwanziger ") is the last brought to market maturity 8-bit - microcomputers of the US technology company Commodore International . The number contained in the model designation indicates the size of the working memory (RAM) installed ex works of 128 kilobytes (KB). Due to the wide range of services, which, according to contemporary perception, combines the properties of home computers with those of workstation computers, the computer cannot be clearly assigned to a device class. The computer can be operated and programmed with the help of a proprietary, interpreted dialect of the BASIC programming language .

The C128, which is the successor to the world's best-selling Commodore 64 home computer , was first presented to the world in January 1985 at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas after a five-month development period. Shortly afterwards, the launch price was US $ 300 in the United States, £ 269 in Great Britain and DM 1,198 in West Germany . With around four million units sold worldwide, the C128, which was produced in three different versions until 1989, is one of the most commercially successful computers of the second half of the 1980s. Nevertheless, the versatile device could not dominate in any market segment: In the high-priced area, the sales figures lagged significantly behind those of the IBM PC-compatible ones , in the middle price segment Atari 520 ST and Amiga 500 dominated the market and in the low-priced 8-bit home computer area, as was ahead of its predecessor, the Commodore 64, the top position in terms of sales.

The relevance of the C128 in terms of technology history is derived primarily from the unusual equipment of the computer with two 8-bit main processors from different manufacturers and three different operating systems.

history

In the first half of the 1980s, home computers had already firmly established themselves as a mass product on the entertainment electronics market . However, in North America and Western Europe there was a fierce battle for market share between primarily US manufacturers such as Commodore, Atari , Apple and Texas Instruments . This is why this era, which was shaped by numerous incompatible models, is sometimes referred to as the “home computer war”.

Inside the company, too, tensions arose between corporate management and the development department at Commodore. Almost all of the engineers involved in the development of the C64, including the chip developers Bob Yannes and Al Charpentier, complained about the lack of salary increases despite the great sales success. There was no agreement on new hardware projects. Charpentier proposed the development of a new computer called the C80 with an 80-character screen, 256 kB RAM, a high-resolution monitor and a faster floppy disk drive for the medium price segment.

However, this idea was rejected by chief executive Jack Tramiel, who is known for his low price policy . Tramiel expected more profit from a cheaper new computer like the C64 that could be connected to conventional television sets. In the summer of 1983, Tramiel's orders began to work on the Commodore 264 series with the aim of developing a competing model for the successful British low-cost computer ZX Spectrum . Yannes, Charpentier and other leading engineers then left the company.

Tramiel himself had to vacate his position as managing director on January 13, 1984 due to irreconcilable differences of opinion with the main shareholder and chairman of the supervisory board Irving Gould after a good thirty years with the company. He was replaced on February 21, 1984 by Marshall F. Smith, who had previously worked in the steel industry. Although the market-leading C64 still sold excellently, the computers of the Commodore 264 series, which were not compatible with the C64 and which were brought to market at the beginning of 1984, turned out to be slow-moving.

development

Project planning taking into account customer requirements

In order to get clarity about the customer's wishes regarding a C64 successor, Commodore employees carried out a survey among the trade fair visitors who owned a C64 on the occasion of the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago. This resulted in great satisfaction with the graphics capabilities, the sound generation options and the comparatively low price of the C64. In addition to the most frequently mentioned C64 software compatibility, an improved BASIC, more RAM, the ability to display 80 characters per line, a numeric keypad, a faster floppy disk drive and the native ability to use professional CP / M software were among the most urgent requests for improvement.

In September 1984, managing director Smith finally commissioned the development of the C128, taking into account the improvement requests mentioned. The new computer should be ready in time for the Winter Consumer Electronics Show scheduled for January 1985 in Las Vegas. This meant that only four months of development time were available. Project management was taken over by Bil Herd, who was appointed head of the hardware development department in 1983 at the age of 24. The knowledge that the C128 Commodore would be the last representative of the 8-bit home computer pioneer generation was a special motivation for the development team.

planning

A development team headed by Robert Russell had been working on a new home computer model called the D128 since 1983. The D128, for its part, was based on considerations made in connection with the planning of the CBM-500 series , which included the B128 as an office computer model and the P128 as a home computer model. Similar to the P128, the D128 should also be equipped with the 8-bit main processor MOS Technology 6509 (MOS 6509 for short), which is capable of managing more than 64 kB of RAM, as well as the MOS Technology 6581 sound chip (MOS 6581 for short) already built into the C64. Since Russell's engineers did not venture to develop the fuel-capable and very complex 40-character graphic chip MOS Technology VIC II (VIC II for short) after Charpentier's departure , the screen output of the D128 was problematic. Last but not least, the use of two graphics chips working in parallel in the form of the tried and tested VIC II and a color-capable 80-character graphics chip still to be developed was considered.

Since the planning either way did not provide for C64 compatibility or CP / M capability and thus contradicted the specifications made by the company management, the D128 project was ended by Herd without further ado. Herd's own development team took up some of the considerations made in connection with the D128 when planning the C128, for example with regard to the use of two graphics chips. In order to be able to implement the desired improvements in performance without losing full C64 compatibility, the chipset built into the C64 since 1982 with the main processor MOS Technology 6510 (MOS 6510 for short), the graphics chip VIC II, the sound chip MOS 6581 and other components should also be used for the C128 can easily be further developed. In order to implement the required CP / M capability, the widespread CPU Zilog Z80 A (Z80A for short) was used as a second processor.

In order to achieve the set goals, the C128 should also be provided with three completely independent operating modes. In order to develop the extensive software library that already exists for the C64, the hardware of the new computer in C64 mode should emulate the previous model completely . A higher working speed, a more comfortable BASIC and an enlarged main memory should be available in the C128 mode, which was intended as the main operating mode. Finally, the CP / M mode was primarily intended for serious professional applications and the use of the tried-and-tested and abundant CP / M software. While the original operating system kernel of the previous model could be used unchanged for the C64 mode, a new operating system kernel and a more powerful dialect of the Commodore BASIC had to be programmed for the C128 mode .

implementation

In order to be able to achieve the desired higher operating speed in the C128 mode, the well-known 8-bit main processor MOS 6510 from the C64, which works with a clock frequency of around 1 MHz, has been revised and further developed. This task was taken over by the group's own semiconductor development department. It was called the Commodore Semiconductor Group (CSG for short) and emerged from the semiconductor manufacturer MOS Technology, which was taken over by Commodore in 1976 . The revision finally led to the completion of the MOS Technology 8502 (short MOS 8502) with a clock frequency of around 2 MHz twice as fast and with additional functions.

The graphics chip VIC II from the C64 was further developed by Dave DiOrio and could now process graphics data with the same basic clock rate as the MOS 8502 with the video signal switched off. However, the resulting MOS Technology VIC IIe (VIC IIe for short) did not show any significant improvements in terms of image resolution , color depth or the fuel capability, which is important for the games industry.

Frank Palaia took on the task of successfully completing the integration of the Z80A into the proven 8-bit computer architecture from Commodore in December 1984. For this purpose, the clock frequency of the Z80A, which is actually twice as fast, was throttled to 2.04 MHz. For operation under CP / M, a porting of the current operating system version CP / M-Plus version 3.0 (CP / M 3.0 or CP / M-Plus for short ) had to be developed that was tailored to the hardware of the C128 . This task was entrusted to the programmer Von Ertwine. Terry Ryan wrote the new BASIC dialect for programming and operation of the C128, henceforth called Commodore BASIC V7.0. Fred Bowen was entrusted with the programming of the operating system routines.

The working memory of the new computer has been increased to 128 kB RAM, which gives it its name. Since the 16-bit address bus structures of the MOS 8502 were not sufficient to manage such a large main memory, a memory management module and an address manager also had to be newly developed. Dave Haynie's experience in emulating the address manager and the conception of the time control later flowed into the development of the Commodore Amiga . In accordance with customer requirements, the VC1541 5¼ inch floppy disk drive of the previous model C64, notorious for its extremely slow data transfer, was to be replaced by a newly developed device with a significantly higher data transfer rate. Greg Berlin was responsible for planning the hardware of the new 5¼-inch floppy disk drive VC1571 , while Dave Siracusa programmed the associated floppy operating system Commodore DOS 3.0.

The C128 also received a completely new design that, in contrast to the bulky bread box shape of the C64, aimed at professionalism, office suitability and improved ergonomics . The case has been significantly flattened compared to the previous model in order to save users the tiresome lifting of the heels of the hands when operating the keyboard. In addition, the keyboard received a numeric keypad and additional function keys. It is not known who exactly designed the case of the C128. It is assumed that the award-winning industrial designer Ira Velinsky, who had already designed the cases for the Commodore Max , SX-64 and Plus / 4 models before he left Commodore International with Tramiel in 1984, was involved.

Problems with the integration of the 80-character graphics chip

At the time the C128 was being developed, the hardware development department at Commodore already had experience with graphics chips capable of displaying 80 characters per line. For example, CSG had already further developed the Motorola 6845 for the office computers of the CBM-8000 series to become the MOS Technology 6545 (MOS 6545 for short) that serves as the control circuit for the cathode ray tube of the permanently installed screen. The MOS 6545, also known as Cathode Ray Tube Controller (CRTC for short) in English-speaking countries, was only able to display texts in two colors. Therefore, the graphics chip for the D128 as well as a 16-bit was Workstation designed, but also never to series production brought Commodore 900 under the leadership of Kim and Anne Eckert from the beginning of 1983 in approximately one and a half years for using a palette of 16 colors and dedicated graphics working MOS Technology 8563 (short MOS 8563) further developed. Since the MOS 8563 was primarily intended for word processing, the ability to display sprites was dispensed with.

In order to implement the capability of the C128 to display 80 characters per line, the development department decided to install the MOS 8563 in the new computer. When trying to integrate the MOS 8563 into the system architecture of the C128, however, there were communication problems between the stove and the independently working CSG. Herd knew that the MOS 8563 represented a further development of the Motorola 6845 and the MOS 6545, which were already being considered for use in the D128. However, the C128 project manager had not been informed about changes to the address bus structures, the timing and the handling of the read / write line from the colleagues in the semiconductor development department. The 80-character graphics chip of the C128, which was basically usable from September 1984, therefore repeatedly caused problems for the hardware developers, especially with its tendency to overheat resulting from stove ignorance and its clocking, which deviates from the 40-character graphics chip VIC IIe.

Official presentation

According to Herd, the shortage of time when planning the C128 was so great that the sinks in the development laboratory had to be used as temporary showers. The overheated floppy disk drives were used to keep the ready meals consumed at work warm. The night before the opening of the Winter Consumer Electronics Show (CES for short) from January 5 to 6, 1985, work had to be done on the prototype of the C128 until two in the morning in order to be able to present the computer to the public in good time. On top of that, the hotel room reservations made by the presentation team in Las Vegas had been canceled by an unknown person in the run-up to the fair. It was possibly an act of sabotage by the former Commodore manager Tramiel.

At the time of its official presentation, the C128, announced with a list price of under US $ 300, was not yet really reliable. An average of two copies of the 80-character MOS 8563 graphics chip burned out per day. The presentation team secretly replaced the defective graphics chips behind the scenes with functional replacement modules. This gave the trade fair audience the impression of an already perfectly functioning, ready-to-use computer. Only in the course of the next few months did the Commodore developers succeed in implementing the MOS 8563 in the overall system in a technically reliable manner, even in continuous operation, by changing the layout of the motherboard.

In addition to the C128, Commodore also presented the new, CP / M-compatible 5¼-inch floppy disk drive VC1571, the 1902 color monitor, a monochrome monitor and the 1350 computer mouse and announced the release of a more expensive desktop version of the computer called the C128D with an integrated VC1571 without giving a specific date for the market launch. In addition to various memory expansions with the model 1660 a 300 baud modem and the model 1670 a 1,200 baud modem for the C64 and C128 were announced.

The C128 was presented to the continental European public at the Hanover Fair from April 17 to 24, 1985. It was a prototype with a German keyboard. The new computer advertised as “super thing” now worked technically flawlessly and attracted a lot of attention. New software developed for demonstration purposes, however, remained a rarity at this point, to the disappointment of the trade fair visitors - with a few exceptions such as the Superscript word processor . The porting of CP / M-Plus was not yet completed and the test version presented was also very slow. The West German introductory price was DM 1,198. In addition to the C128, a prototype of the desktop version C128D was also on display.

In Great Britain, the C128 was officially introduced on the occasion of the International Commodore Computer Show from June 7th to 9th, 1985. The introductory price for the C128, which was not yet announced by the manufacturer for Great Britain at that time, was estimated at £ 300-350 and for the not yet market-ready C128D at £ 500-600.

Desktop model variants

At the Which Computer Show, which was held from January 15 to 18, 1986 in the National Exhibition Center of the English industrial city of Birmingham , Commodore presented the C128D, which had already been announced last year, to the European trade audience with a space-saving plastic housing, fold-out handle, separate keyboard and integrated 5¼-inch VC1571 floppy disk drive officially before. The suggested retail price for the new, business-oriented model was initially £ 499 or £ 538.85 including VAT. A monochrome monitor should also be included in this price. The whole package ended up costing £ 599.

Despite initial sales successes in Western Europe in the course of 1986, the C128D was not sold in the US because, in the opinion of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) responsible for the approval of electronic devices, the computer was not sufficiently interference-free. In order to still meet the strict FCC standards and not to lose market share, the company developed the C128D-CR, another desktop model with a metal housing and revised electronics, which should replace the C128D. The new device was presented to the North American audience at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show held in Las Vegas from January 8-11, 1987. The suggested retail price was US $ 550.

Probably as early as the end of 1985 the Commodore development department was also working on another variant of the C128D with an integrated 3½-inch floppy disk drive. However, the development of a functional, but never beyond the planning stage, NTSC prototype remained. This contained the circuit board and drive mechanics of the 3½-inch diskette drive VC1563, which was also never ready for series production, with its own diskette operating system already programmed for the later VC1581 on a temporary EPROM chip, a heavily modified motherboard, several improvised additional boards, a plastic housing with ventilation slots and one fold-out handle. In order to distinguish it from other model variants, this prototype is unofficially referred to as the C128D / 81, as there is no clarity about the project name used internally by Commodore (the term “Kentron” may have been used for this).

By early summer 1986, all C128 model variants intended for Western Europe were manufactured in Commodore's branch in Corby , England . After the closure of the only British production facility of the global group, production of the computer was relocated to the West German branch in Braunschweig for cost reasons . At the end of 1986 the company management decided to have the new Amiga 2000 manufactured in Braunschweig in the future , while the C128 production was relocated to the parent plant in West Chester in the US state of Pennsylvania and to the Far East.

Successor models without series production

Chief developer Bil Herd left Commodore shortly after the market launch of the C128. Dave Haynie and Frank Palaia from the former development team worked on possible successor models based on the C128 from 1986, despite the obvious loss of importance of the computers with 8-bit architecture.

Several design studies resulted from this collaboration. One of them was the desktop model Commodore 256 (C256 for short), which at least made it to the stage of a demonstrable prototype and is also mentioned in a maintenance manual for the C128 from 1987 as a planned successor to the C128. The C256 prototype had an integrated 3½-inch floppy disk drive and an internal hard disk with a storage capacity of 25 MB, a more generous working memory of 256 kB RAM and a second processor Z80A clocked at full 4 MHz. The higher clock rate should lead to a significant increase in the working speed in CP / M mode compared to the C128.

Another design study aimed at a stripped-down version of the basically overly complex C128. Without any C64 compatibility, it should only have the 80-character graphic chip MOS 8563 and should therefore be significantly cheaper to manufacture.

However, both concepts were flatly rejected by the company's management. Since the C128 already had memory expansions from our own company, with the help of which the main memory could be expanded to up to 640 kB RAM, there was no need for another model based on the C128 with a storage capacity of only 256 kB. Even the renunciation of any C64 compatibility and the fuel capability of the 40-character graphics chip VIC IIe did not convince the top management, who knew about the importance of the game software. Haynie and Palaia then concentrated entirely on the development of the still unfinished 16-bit high-end computer Amiga 2000.

Although Commodore did not bring a C128 successor model to market maturity, the completely redesigned design of the computer including the flattened case shape, beige case color and ergonomic keyboard was made by the development department when planning the C64C - a 1986 revision of the C64, which was originally made in a gray bread box shape accepted.

marketing

Launch in North America and Western Europe

The original plans were for the C128 to be available in the United States by April 1985 at the latest and in Europe by the following summer. The series production of the C128 did not start until the summer of 1985, so that these deadlines could only be partially met. From the end of July 1985, the first copies of the calculator were available in West German department stores. At the end of August 1985, the big US department store chains such as Kmart or Sears Roebuck followed , while the C128D, which was planned to be launched a little later, but did not receive FCC approval, should be reserved for specialist retailers. In Canada, the computer was initially only available in small numbers from September 1985, because there were problems with the acceptance of the power supply by the responsible authorities and each copy had to be checked individually before being sold.

From September 1, 1985, the C128 should originally also be available in Great Britain. However, delivery there was delayed in order to gain time to develop a cheaper, only £ 199 alternative to the relatively expensive VC1571, which eventually came with the 5¼-inch read / write head housed in the previous model's VC1541. Floppy disk drive VC1570 was implemented. Since British consumers were less willing to spend on a new computer than customers in more affluent North America, the marketing department hoped that the cheaper VC1570 would have greater sales opportunities for the C128 itself. The VC1570 is therefore practically unknown in the United States. From the beginning of October 1985 the calculator was finally also available in Great Britain - initially only a few in independent specialist shops, then also in large department stores.

Production delays on peripherals and desktop models

Commodore initially only delivered the C128. The peripheral devices should follow some time later. However, there were delays of several weeks in the production of the VC1570 and VC1571 floppy disk drives and the newly developed RGBI-capable color monitor in 1902. In the United States, the VC1571 and 1902 NTSC color monitor became available in smaller quantities in November 1985. Around the same time, the cheaper VC1570 floppy disk drive and the PAL color monitor 1901 were also available in Great Britain. The VC1571, on the other hand, was only available there from March 1986 for £ 269 and was just as expensive as the computer itself. In West Germany, on the other hand, both disk drives were only available around the turn of the year. Commodore press spokesman Gerold Hahn denied any rumors that had arisen about technical problems and blamed delivery difficulties at the suppliers of the case and the drive mechanism of the VC1571 for the delays. The introductory price of the VC1570 in West Germany was 750 DM, while the VC1571 cost a little less than the C128 at 950 DM. The 1901 color monitor was available in West Germany from the same date for DM 998. The 1,200 baud modem 1670 was available from the end of 1985. However, early series of the device contained a hardware error. Although this was corrected in later production series, the modem 1670, which was only manufactured in small numbers and available for US $ 89.95, did not achieve high market penetration and was hardly available until mid-1988.

The production delays and delivery difficulties that had already occurred in the course of the market launch continued with the peripheral devices brought to market by Commodore after 1985 and the desktop model C128D-CR, while the C128D appeared punctually in Western Europe at the beginning of 1986 and was already available in high numbers in the second quarter was. As early as the spring of 1986, Commodore announced the imminent readiness for series production of the digital joystick mouse 1350 and the memory expansion modules 1700, 1750 and 1764 with capacities of 128 kB, 256 kB and 512 kB respectively. In the summer of 1986, plans to develop the 3½-inch VC1581 floppy disk drive were also announced. According to the plan, the VC1581 floppy disk drive and the mouse 1350 should be available from autumn 1986 at the latest. The recommended retail price for the VC1581 was initially US $ 399, but was later lowered to US $ 249.95. The street price for the VC1581 in West Germany in autumn 1987 was around DM 600.

However, there were again production delays. The 128 kB memory expansion 1700 for 198 DM and the 512 kB version 1750 for 298 DM were not available in stores until the end of 1986. At the beginning of 1987, the 256 kB memory expansion 1764 followed for an initial price of US $ 129, and then US $ 149.95 later. Due to delivery problems on the part of the supplier companies for the RAM chips, the 512 kB version could only be produced in small numbers anyway. It was therefore always difficult to obtain, even in North America. In West Germany, the 1750 model was sold out after just a few months and from then on - if available - had to be imported from the United States. The other peripherals mentioned did not gradually hit stores until the first three quarters of 1987. In addition, in the summer of 1987 the analog proportional mouse 1351, which had already been presented at the previous Winter Consumer Electronics Show, was brought onto the market for US $ 49. Also in the summer of 1987, Commodore released corrected versions of the Commodore DOS 3.0 burned onto ROM chips for US $ 9.95 and the C128 operating system for US $ 24.95.

In the autumn of 1987, in cooperation with the then Deutsche Bundespost, the BTX decoder module II, available for 399 DM, was launched in West Germany, with the help of which the interactive end-user information system screen text (BTX for short), which at that time was accessible across Germany via just 70,000 connections. could be operated on the C128, which is regarded as the failed precursor of today's Internet and the World Wide Web . With this cooperation, the three million BTX connections originally targeted by the Bundespost should at least be brought closer. By the beginning of 1989, however, the number of BTX connections was only doubled to just under 150,000.

Even the newly developed top model C128D-CR, officially launched in January 1987, was only available from the third quarter of 1987, despite the simplified manufacturing processes and lower manufacturing costs compared to the keyboard computer version and the C128D. Due to the unexpectedly high demand, it was even temporarily in the spring of 1988 Delivery problems with this last model variant of the C128 brought to market.

TV and magazine advertising

As part of the launch of Commodore turned on the US television and in magazines one against competing models IBM PC , IBM PCjr and Apple IIc directed advertising campaign with the slogan, Bad news for IBM and Apple '(English "Bad news for IBM and Apple " ). Other advertisements published in various computer magazines emphasized the superiority of the C128 over the Apple IIc in terms of storage capacity, for example, with slogans such as ' Thanks for the memory' and also emphasized the addition of a numerical keypad Keyboard the outstanding graphics and sound capabilities of the new computer. However, the more compact design of the Apple IIc compared to the C128, whose alleged technical inferiority is symbolized in the attached advertising photo by apples falling from the tree, was kept secret. In another advertisement, the C128 was shown in a horizontal sequence of images as a continuously developing and expanding computer system with a computer, floppy disk drive, memory expansion, mouse, modem, printer and color monitor, alluding to current representations of the human tribal history caused by evolution , accompanied by the Slogan ' How to evolve to a higher intelligence' .

The software manufacturers initially waited with regard to the C128. Only a few established publishers such as Timeworks, Audiogenic , Thorn EMI , Spinnaker Software or Precision Software announced programs for business purposes, but no games for the near future. When more and more C128 owners began to complain about the lack of software for their new computers in various computer magazines towards the end of 1985, Commodore published advertisements using the slogan ' Hard Facts About the Software ” ) announced the development of hundreds of new application programs for the C128 mode. Overall, however, the advertising campaigns for the C128 in the United States pale in comparison to the more intensely advertised Amiga 1000 .

In Great Britain, General Manager Smith saw the CP / M-capable Amstrad CPC6128 , also marketed by Schneider in West Germany , as the main competitor of the C128 - a point of view shared by parts of the British trade press. With advertising texts such as “The facts speak a clear language” ( “When you look at the facts, they do seem to weigh heavily in our favor” ) and accompanying photos that show the C128 as the winner of a weight comparison with a competitor model that cannot be precisely identified on a Beam scales were advertised in British computer magazines for the calculator. The idea was to give the C128 the image of an office computer that was also interesting for business people and small business owners, and with which one could not only play.

In the German-speaking area, the Apple IIc, like its predecessors Apple IIe and Apple II Europlus, was hardly widespread because of its high price. That is why a different advertising strategy was initially pursued there. In the tradition of the successful office computers of the CBM-8000 series , the C128 was presented to German-speaking customers as a professional, technically superior personal computer to the far more expensive IBM PC . It was particularly emphasized that the new computer with full C64 compatibility with its 80-character screen, its CP / M capability and its large working memory, which can also be expanded to 640 kB RAM, "extends far beyond the limits of the home computer class". In fact, the C128 was slightly superior to the IBM PC in benchmark tests with regard to the calculation of prime numbers and floating point numbers in BASIC and was also able to keep up with the IBM computer in terms of the speed of reading data stored on floppy disk and the storage capacity per diskette. The IBM PC only had speed advantages over the C128 for disk writing operations. It was later used with slogans such as “Mighty memory. Strong programs. A higher form of intelligence "or" high intelligence. Powerful vocabulary. Three microcomputers packed into one ”linked to the advertising campaign carried out in the English-speaking world.

After the market launch of the C128, the group got increasingly into financial difficulties, which also had an impact on product advertising. In the third quarter of 1985, losses of US $ 39.2 million were posted, some of which was attributed to the high development costs for the C128 and the Amiga 1000. In the fourth quarter of 1985, the deficit even grew to US $ 50.2 million. In total, the losses in calendar year 1985 amounted to a whopping 144 million US $. The first quarter of 1986 also showed no improvement with losses of US $ 36.7 million. In April 1986, Thomas J. Rattigan replaced his predecessor Smith as Commodore managing director due to this downturn. Rattigan closed unprofitable branches like the one in Corby, England, and took out a loan of US $ 135 million, running until March 15, 1987, which was even increased to US $ 140 million in the fall and, last but not least, appropriate marketing of the C128 as well of the Amiga 1000 should allow.

These measures actually brought the company back to profitability. However, advertising spending under Rattigan was initially reduced. The lack of advertisements and the imminent publication of the slightly more expensive, but significantly more powerful Amiga 500, prompted denied rumors by the top of the company that production of the C128 would be discontinued after the 1986 Christmas season , the advertising measures were briefly strengthened again. After that, Commodore completely renounced advertising and aggressive marketing. From then on, the C128 was only advertised - albeit indirectly - only by Berkeley Softworks , the publisher of the GEOS 128 graphical user interface that was brought out for the computer in 1987. Slogans such as 'Will your C128 grow up or old?' (English "Is your 128 growing up or growing old?" ) or "Scientists from the University of Berkeley stop the aging process" (English "Scientists at Berkeley stop the aging process" ) aimed at enabling the computer despite its 8 -Bit architecture to give the image of a still modern personal computer.

Special offers

In Great Britain, the home computer industry was dominated by domestic manufacturers such as Sinclair , Acorn and Amstrad in the mid-1980s , while Commodore was considered the industry leader in the United States and West Germany. The company therefore went to great lengths to boost sales specifically in the UK. This included numerous special offers.

In the pre-Christmas season of 1985, the C128 was bundled with the VC1570 floppy disk drive for an inexpensive £ 449.99. This package was flanked by other special offers. For example, owners of the C64 were offered a discount of £ 50 if they were willing to hand over their old computer when they bought a C128. When purchasing a C128, owners of other computer models were also offered a free 1530 datasette worth £ 45 as an incentive in exchange for their previous computers . With this offer, the marketing department hoped to switch users who had previously used home computer systems from other manufacturers. Finally, with the free datasette, customers were given access to all of the C64 game software, which can be purchased cheaply on compact cassettes. In the run-up to the 1986 summer vacation, the marketing department also introduced special bundled offers with additional purchase incentives. Each package consisting of a C128, a VC1570 and a Commodore monitor was accompanied by five vouchers worth £ 50 each. The vouchers could be redeemed in selected travel agencies when booking package tours.

Since a relatively expensive and therefore unaffordable RGBI color monitor for most British home users was required to operate the computer in 80-character mode, Commodore began to develop new special offers aimed at the comparatively financially strong small business owners from the beginning of 1986. For this purpose, the development of the office-compatible C128D, which was announced in the summer of 1985, the mouse of the type 1530 as well as the memory expansions was accelerated. Inexpensive bundled offers consisting of a C128D, a monochrome monitor and a software package at a price of £ 499 should also help the computer to gain larger market shares in the British education market, which was previously dominated by Acorn's BBC Micro and its successor, the BBC Master .

In the months after its market launch, US consumers were offered the computer together with a free subscription to the online service provider QuantumLink, via the Commodore Information Network, which had previously been operated in cooperation with Compuserve and, in addition to exchanging information, was also used for customer service, from November 1985 could be accessed.

Cessation of production

While the development department at Commodore repeatedly achieved significant cost savings in the manufacture of the C64, the much more complex C128 always suffered from high production costs and comparatively low profit margins. The computer was therefore only competitive to a limited extent in the low-price segment. In the middle price segment, however, the C128 achieved a higher level of market penetration. The considerably more powerful and gradually becoming cheaper 16-bit computers such as the Atari ST , the Amiga 500 released in 1987 and the numerous IBM PC-compatible ones gradually gained market share in this area, which is decisive for sales of the C128.

At the COMDEX computer trade fair held from November 1st to 6th, 1987 , the company management officially announced, despite this growing competition, even from within its own company, that it would continue to produce the C128 beyond Christmas 1987 if demand did not decrease. After that, however, the computer gradually approached the end of its market presence. In a survey among the readers of the computer magazine 64'er to determine the computer of the year 1988 , the C128 only landed in the middle, behind more powerful 16-bit computers such as the Apple Macintosh II , the Amiga , the Compaq Deskpro and the IBM Personal System / 2 as well as the models of the Atari ST series , but still before the C64, the home computers of the Atari XL series or the standard-setting IBM PC / XT / AT. In January 1989, production of the original keyboard computer version was initially discontinued in favor of the C128D-CR. In addition, Commodore offered potential buyers of an Amiga 500 or an Amiga 2000 in the United States a price reduction of US $ 100 in exchange for their old C128 models. In March 1989 the 5¼-inch floppy disk drive VC1571 was also withdrawn from the market, which prompted hastily denied rumors about an imminent production stop of the C128-DCR. In Canada and Western Europe, however, the VC1571 was still available for some time. At the same time, the complaints printed in the computer magazines about the inadequate support of the C128 by Commodore increased. In July 1989 the company management finally decided to stop the production of the no longer profitable C128D-CR.

Sales

Falling prices made the remaining copies of the C128D-CR, which had not yet been sold, again attractive for many small West German entrepreneurs in 1990, as the computer was well suited for managing company finances. After the end of the Commodore fiscal year 1989/90, which ended in the second quarter, the computer no longer played a role in the manufacturer's balance sheets. The majority of the C128 owners switched to the now dominant IBM PC-compatible computers with XT or AT architecture or other platforms with more powerful 16-bit main processors such as the Amiga. With a few exceptions such as the Wordstar 128 word processor , the dBase II database application or the Microsoft Multiplan spreadsheet , many commercial application programs for the CP / M mode were no longer commercially available at this time, as MS-DOS had meanwhile CP / M had already replaced the de facto standard operating system.

Occasionally in 1991, unsold copies of the C128D-CR from old West German production re- imported from the other EC countries were offered in various department stores for 499 DM. Peripheral devices such as the 3½-inch VC1581 floppy disk drive, memory expansions and commercial software for the C128 mode or operation with CP / M-Plus were practically only available in the United States at that time. In order to eliminate these supply bottlenecks, replicas of the VC1571 floppy disk drive and the 512 kB memory expansion 1750 by the hardware manufacturer CEUS-Computersysteme were brought onto the market in Germany in 1992.

In the United States, the C128D-CR was offered by mail order wholesaler Montgomery Grant until mid-1991, including a free computer game for US $ 399. Until 1997, repaired used copies of the computer were also advertised for sale by the hardware manufacturer Creative Micro Designs . Both model variants achieved gradually increasing prices, which were between US $ 129 and US $ 159 for the C128 and between US $ 239 and US $ 299 for the C128D-CR.

Sales figures

At the time of the market launch, the company's management assumed that one million copies of the C128 had been sold by the end of 1986. In fact, the computer initially sold extremely well. In June 1985 there were already 100,000 pre-orders. By the end of 1985, 425,000 units had been sold worldwide, 60,000 of them in West Germany. At the beginning of September 1985, Commodore even hired 350 new workers in order to be able to produce the C128 and its predecessor in sufficient quantities. By Cebit in March 1986, almost 500,000 copies were sold worldwide, which Harald Speyer, head of the German branch of Commodore International, described in an interview as the “most successful market launch of all time”. By mid-1986, 600,000 units had been sold in the United States alone. At that time, the C128 was considered to be one of the fastest-selling computers in recent American technology history. Outside of North America, however, sales were more sluggish. Of the approx. 800,000 units sold worldwide up to August 1986, for example, only 10 percent came from the western German market dominated by Commodore, i.e. just 80,000 samples. Nevertheless, the computer was definitely a sales success: Commodore managing director Rattigan confirmed in an interview in the spring of 1987 that around one million units of the C128 had actually been sold worldwide by the end of 1986. The original expectations of the top management had thus been fulfilled.

By July 1987, the number of copies of all C128 model versions sold in West Germany rose to 210,000. This corresponds to a share of 10.67 percent of all Commodore computers sold there up to this point in time. In April 1988, the estimated number of North American C128 users was already 1.5 million. The C128 was particularly popular there among users who already owned a Commodore computer. According to a survey published in May 1986 by the US computer magazine Run , 78 percent of this group of people said they would buy a C128 in the near future. The company management itself, however, had only expected 28 percent. In August 1988, the number of units sold worldwide exceeded the two million mark. With a total of four million units sold worldwide by 1990, the C128 finally achieved by and large "acceptable sales figures".

With 284,300 units sold by 1990, the C128 remained far behind the 3.05 million units of its predecessor, the C64, in West Germany. The sales figures were thus at the same level as those of the models of the Commodore 264 series that were ready for the market in 1984 and are generally considered flops. However, the relatively high sales figures for this model series are mainly explained by the dropping prices at which the devices were sold in the branches of the supermarket chain Aldi from 1985 after a market presence of only one year . Incidentally, there were also many loyal Commodore customers among the West German C128 owners. Most of them had already purchased a C64 or a Plus / 4 before.

According to an estimate published in SPIEGEL , around 200,000 home computers from Western production came to the GDR by the time of German reunification , most of them as private imports in luggage. Among them was an unknown number of copies of the C128. In a survey carried out by the computer magazine 64'er in the spring of 1990, 26 percent of the West German respondents said they had a C128. In the GDR, however, the proportion of the C128 was only 11 percent.

Price development

United States

During the C128's market presence, prices for the computer in the United States remained relatively constant. The manufacturer's suggested retail price of less than US $ 300 for the keyboard computer version - several sources even speak of just US $ 250 as the originally planned introductory price - could not be sustained due to the high production costs. From the fourth quarter of 1985 onwards, it was always between US $ 349 and US $ 399. The recommended retail price for the C128D-CR ranged between US $ 549 and US $ 599.

The street prices of the computer, which is often bundled with a floppy disk drive and a monitor in department stores, specialty shops and by numerous mail order wholesalers such as Lyco Computer, Protecto, Computer Direct or Montgomery Grant, were usually well below the list prices of Commodore, especially in the run-up to Christmas. In December 1987, for example, Montgomery Grant asked for US $ 219.95 for a C128, around US $ 130 below the current price recommendation. At the same time, Lyco Computer was selling the C128D-CR for US $ 439.95, around US $ 160 below the current list price.

| model | Oct. – Dec. 1985 |

Jan. – Jun. 1986 |

Jul. – Sep. 1986 |

Oct. – Dec. 1986 |

Jan. – Jun. 1987 |

Jul-Dec 1987 |

Jan. – Jun. 1988 |

Jul-Dec 1988 |

Jan. – Mar. 1989 |

Apr. – Jun. 1989 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C128 | US $ 349 | US $ 349 | US $ 349 |

US $ 399 | US $ 399 | US $ 349 | na * | na * | - | - |

| C128D-CR | - | - | - | - | US $ 550 | US $ 599 | na * | US $ 549 | US $ 549 | US $ 599 |

| * not available | ||||||||||

Great Britain

In the UK, wholesale mail order prices were initially barely below the stable recommended retail price of £ 269 for the C128 and £ 499 for the C128D. For example, Dimension Computers sold the keyboard computer version in January 1986 for a full £ 269.95 and the desktop model was £ 499.95. Evesham Micros and HiVoltage, on the other hand, offered the keyboard computer version at the same time a little cheaper for £ 259. HiVoltage charged £ 489.95 for a C128D.

It was only after some time that the computer was finally offered in the United Kingdom well below the official list price. For example, Dimension Computers advertised the keyboard computer version in December 1987 for £ 199.95, around £ 70 cheaper than recommended by Commodore. In contrast, the C128D-CR, which has now replaced the C128D, was charged at £ 399.95, around £ 100 less than the manufacturer's recommended retail price.

West Germany

In West Germany, the prices for the computer were initially at a significantly higher level than in Great Britain. In the first few months of the C128's market presence in autumn 1985, however, only a few mail order wholesalers actually asked for a price equal to the recommended retail price of DM 1,198 for the keyboard computer version. In September 1985, these providers included the hardware and software sales company H. Steber (HSV Steber for short). In November 1985, however, HSV Steber reduced the price for the C128 to 1,098 DM.

By contrast, the vast majority of mail order wholesalers already estimated prices below the DM 1,000 limit, which is important in terms of sales psychology, at the end of the third or beginning of the fourth quarter of 1985 . Neckermann , the IES computer trading company, Computer Reschke and Valasik-Computer, for example, charged DM 998 for a C128. At Abacomp the computer cost 960 DM. The computer and software sales company Riegert (CSV Riegert for short) offered the C128 in September 1985 for 949 DM and in October 1985 for 929 DM. With a price of 898 DM, the CC computer dispatch even remained below the 900 DM limit and thus 300 DM below the manufacturer's recommended retail price. In order to boost Christmas sales, HSV Steber finally dropped the price to DM 998 in December 1985.

The retail chain Vobis offered the C128 in January 1986 for 975 DM and the C128D for 1,785 DM. Later in 1986, however, wholesale mail order prices fell noticeably for both the keyboard computer version and the desktop model. At the end of the first quarter of 1986, ProSoft GmbH offered the C128 for 798 DM and the C128D for 1,698 DM. At the same time, Dela Elektronik was asking for 899 DM for the C128. CSV Riegert reduced the price for the C128 to 749 DM by the end of the second quarter of 1986. At the end of the third quarter, CSV Riegert was still asking 679 DM for the C128 and 1,475 DM for the C128D.

For the 1986 Christmas business, ProSoft offered the C128 for 679 DM and the C128D for 1,288 DM. At the same time, CSV Riegert was still charging DM 679 for the C128, but only DM 1,299 for the C128D. Abacomp meanwhile offered the C128 for 665 DM, the C128D for 1,368 DM. Other mail order wholesalers such as Computertechnik Luda, Computer Discount Munich or the Syndrom Computer GmbH offered the keyboard computer model in the run-up to Christmas also consistently below the 700 DM limit.

At the end of the first quarter of 1987, ProSoft was still asking 679 DM for the C128, but only 1,279 DM for the C128D-CR, which has meanwhile come onto the market. CSV Riegert, on the other hand, no longer had the C128 in its range at this point and was now offering the C128D-CR for DM 1,169. At Vobis, the C128D-CR cost 1,248 DM at the same time. In the second quarter, ProSoft reduced the prices for the C128 to 630 DM and for the C128D-CR to 1,099 DM. CSV Riegert meanwhile only went down by 20 DM with the price of the C128D -CR down to DM 1,149. At Abacomp the computer was now available for 580 DM in the keyboard computer version and for 1,140 DM as a desktop model. In the third quarter of 1987 Vobis asked DM 569 for a C128. CSV Riegert reduced the price for the C128D-CR by a further 100 DM to 1,049 DM in the same period. Abacomp, however, stayed at 1,140 DM for the C128D-CR. At this point, ProSoft was no longer advertising the computer.

At the beginning of the fourth quarter of 1987, the recommended retail price on the part of Commodore was revised downwards to 499 DM for the C128 and 999 DM for the C128D-CR. From then on, numerous providers fell below the DM 1,000 mark for the desktop model for the first time. The C128D-CR could be ordered from Quelle and Abacomp for 998 DM. CSV Riegert offered the C128D-CR for 969 DM. At Zweifach Computer customers had to pay only 444 DM for a C128 and 958 DM for a C128D-CR in the pre-Christmas business of 1987. At Tornado Computer Sales, however, it was 549 DM for the C128 and 979 DM for the C128D-CR.

In the first half of 1988, the keyboard computer model gradually disappeared from the assortments of most wholesale chains and mail order wholesalers. At the same time, hardly anything has changed in the prices charged for the C128D-CR. Only in the middle of 1988 did the price structure move again. Vobis offered the desktop model in the summer of 1988 for 899 DM. CSV Riegert reduced the price for the C128D-CR in the third quarter of 1988 to 929 DM. Two-fold computer followed this example in the fourth quarter with 888 DM.

In 1989, under the impression of the cessation of production of all model variants as well as the rise of the more powerful 16-bit computers such as the company's own Amiga, the Atari ST series or the IBM PC-compatible, further, in some cases significant price reductions took place, the C128D-CR and Remaining unsold copies of the keyboard computer version should make them particularly interesting for beginners. The prices for the desktop model were now consistently below the DM 700 mark and for the keyboard computer model below the DM 350 mark. By the Christmas business in 1989, Zweifach Computer reduced the prices for the C128 to 333 DM and the C128D-CR to 666 DM. At CSV Riegert, a C128D-CR cost 699 DM at the same time.

In the course of 1990, many mail order wholesalers finally took the now technically outdated computer out of their range. Both the C128 and the C128D-CR were still available. In June 1990, Zweifach Computer asked for DM 333 for a bundle offer consisting of a C128, a joystick and two games, while the C128D-CR cost DM 577 at the same time. At that time, the C128D-CR was available from Vobis for 599 DM. The computer was significantly more expensive in mid-1990 in West German department store chains such as Karstadt or Horten . The last remaining copies of the C128 cost around 450 DM, a C128D-CR cost an average of 850 DM. At Christmas 1990, two-way computers only asked 299 DM for the C128 bundle offer and 555 DM for a C128D-CR. At the end of 1990 the second-hand market prices for a C128 were around 200–300 DM, for a C128D-CR around 300–530 DM.

Areas of application

While there were many similarities between North American and Western European users of the C128 with regard to the use of peripheral devices, there are notable differences, particularly with regard to the use of the computer in everyday life and in the educational system.

Use in everyday life

In North America, the C128 owners used their computers much more often for remote data transmission than the C64 users. The C128 was also used more frequently than its market-leading predecessor in the area of application programs. In the late 1980s, desktop publishing was added as a new area of application.

The most popular areas of application for the C128 in German-speaking countries were applications such as creating and printing out texts, the CP / M mode and programming in BASIC or assembly language, while the computer was rarely used for remote data transmission or for gaming. In addition to mostly young men, women in western Germany were also among the users of the C128.

Use in the education system

At schools, universities and other educational institutions in the United States, the C128 could not prevail against the successful Apple II model, which had dominated the market since the 1970s. The computer was used privately by pupils and students, for example for completing homework or seminar papers. In Western Europe, on the other hand, the C128D managed to become the official school computer in several West German states and in Belgium by the spring of 1986.

These decisions made the desktop model variants in Western Europe particularly interesting for new products in the field of learning software . For example, at Didacta , the annual trade fair for schools and training, held from February 16 to 20, 1987 , several software companies showed the C128D-CR as a computer for controlling physical experiments in school lessons. The well-known Danish toy manufacturer Lego also presented the control software of its new Lego Technic Control product range on a C128D-CR on the same occasion. At the CeBIT held from March 16 to 23, 1988, in addition to Lego, Fischertechnik also presented the Computing Experimental construction kit on a C128D, which was intended for learning how to use computers in the areas of measurement, control and regulation . In addition, the computer was used to create school newspapers using desktop publishing software , giving young people their first glimpse into the world of journalism.

hardware

The C128 is technically based on its predecessor, the C64. However, the computer has an improved keyboard , more interfaces with extended functionality compared to the C64, and a much more extensive and technically more powerful chipset with components, which are largely fully downward-compatible further developments of the components used in the previous model. The very complex 8-bit architecture of the C128 also consists of two main processors , two graphics chips , two I / O modules , two memory management units , a sound chip and a number of memory chips that exchange data with each other via a system bus that was extraordinarily complex for the time can.

Neither the hardware properties nor the system software of the C128 allow a clear assignment to a certain device class. The 8-bit architecture, the use of a proprietary operating system in the form of a native BASIC dialect, the availability of connections for two joysticks and a datasette , the plastic housing of the model variants C128 and C128D as well as the comparatively low one speak in favor of an assignment to the home computers Price. In contrast, the ability to display 80 characters per line, the integrated 5¼-inch floppy disk drive in the C128D and C128D-CR models, the sheet steel housing of the C128D-CR and finally the use of the standard CP / M operating system add to the staff Computers or workstation computers close by. Correspondingly, the C128 appeared in the contemporary perception as a "mixture between game computer and professional machine" or as a "general-purpose computer" (German all -purpose computer ).

Main board of the C128 with main processors , graphics chips , sound chips , memory management modules , I / O modules , memory chips , system bus -

conductor tracks, HF modulator, slots, interfaces , bottom shielding plate , imprint of the model name and Commodore logo

Main processors

MOS Technology 8502

The first main processor used in the C128, the MOS 8502, has 40 connection pins and is a further development of the MOS 6510 used in the C64. It was specially developed for the C128 in HMOS- II technology and controls both the C64 and the C128 mode. The MOS 8502, which has a typical 8-bit processor architecture , has eight data and 16 address lines. It also has a program counter (PC), an accumulator (AC), a status register (SR), two index registers (XR, YR), a stack pointer (SP), an interrupt logic , a timer and an electronic arithmetic unit for all logic as well as arithmetic operations responsible arithmetic-logic unit (English Arithmetic Logic Unit , short ALU). The MOS 8502 also has a special one to control the RAM chips, ROM chips, I / O modules, Datasette and the caps lock key on the US keyboard layout or the character set shift key on the versions of the C128 that are not produced for English-speaking countries 7-bit data direction register for defining the data flow direction as well as an associated data register for selecting the named system components.

Via software control, the MOS 8502 can be operated with either a slower clock frequency of 0.985 MHz (PAL version) or 1.02 MHz (NTSC version) and a faster clock frequency of 1.97 MHz (PAL) or 2.04 MHz ( NTSC). This means that it is theoretically about twice as fast as the MOS 6510 in 2 MHz mode. Since both CPUs have the same instruction set, they are completely software-compatible with one another. MOS 6510 and MOS 8502 are also the same with regard to the types of addressing. However, there are differences in the pin assignments.

The clock frequency of the MOS 8502 is generated by the clock module MOS Technology 8701, which in turn is connected to an external quartz crystal and is compatible with both the PAL television standard widely used in Western Europe and the North American NTSC standard . However, the video signal of the VIC IIe graphics chip responsible for displaying 40 characters per line must be switched off in the 2 MHz mode of the MOS 8502. Following the example of the MOS 6510, the MOS 8502 also uses the first 256 bytes of the main memory as zeropage for memory management . In addition, like its predecessor, it has a total of 4,000 transistors.

Zilog Z80A

With the Z80A from the US chip manufacturer Zilog , the C128 has another main processor with a typical 8-bit processor architecture, which can be operated with a clock frequency of up to 4 MHz, but effectively only to a maximum of 2 for reasons of synchronization with the MOS 8502 .04 MHz is clocked. The 40-character graphics chip VIC IIe acts as the clock module. The Z80A, which acts as a second processor and is implemented in NMOS logic , is used to control the C128 in CP / M mode. It consists of 8,500 transistors and has 40 connection pins with eight data and 16 address lines. With a maximum memory access time of 380 nanoseconds, the Z80A is one of the above-average fast 8-bit main processors in this field.

In contrast to the memory-oriented MOS 8502 , the Z80A, which emerged from the Intel 8080 , is a register-related main processor, as is the case with all CPUs of the Intel 80xxx family built into the IBM PC , IBM PC XT and IBM PC AT . Despite its twice as high clock frequency, the Z80A is faster, but not twice as fast as the MOS 8502. The Z80A often needs more clock cycles than the MOS 8502 to process machine commands - a disadvantage that is only partly caused by that of the Z80A Pipelining integrated into the processor architecture is compensated, which allows the Zilog CPU to load a new instruction while the current machine instruction is being processed.

In addition to the MMF 9000 , the CBM 630 and the CBM 730, known in the United States as the SuperPET , the C128 is the only 8-bit computer from Commodore in which a CPU not from the Group's own semiconductor manufacturer MOS Technology has been installed. The Z80A enables the computer to run software that was written for the CP / M -Plus operating system . Since the two main processors, MOS 8502 and Z80A, cannot operate simultaneously, but exclusively in series, the C128 is not a multiprocessor system.

Graphics chips

A special feature of the C128 is that the device is equipped with two 8-bit graphics chips, one of which is responsible for screen output in 40-character mode, the other for screen output in 80-character mode. Since both graphics chips generate their own video signal and have their own interfaces for image output, two monitors can be operated on the C128 at the same time in the C128 mode with the 80 character mode activated. The 80-character screen is used for entering commands via the BASIC interpreter and for text output, while the 40-character screen is used for graphics output. Several versions of both graphics chips were developed and installed in the various model variants of the C128.

MOS Technology 8563

| Color palette of the 80-character graphic chip MOS Technology 8563 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | black | 9 | Magenta (dark) |

| 2 | White | 10 | Dark yellow |

| 3 | Dark red | 11 | Bright red |

| 4th | Cyan (light) | 12 | Cyan (dark) |

| 5 | Magenta (light) | 13 | Medium gray |

| 6th | Dark green | 14th | Light green |

| 7th | Dark blue | 15th | Light Blue |

| 8th | Light yellow | 16 | Light gray |

For the first 8-bit graphics chip of the type MOS 8563 installed in the C128, the abbreviation VDC has become established, which stands for the term video display controller, which is common in the English-speaking world but also in German-speaking countries . The MOS 8563 with 42 connection pins is used in the model variants C128 and C128D and is responsible for the screen structure in high-resolution 80-character mode. The graphics chip produced in the HMOS-II technology not only takes over the generation of the CGA compatible RGBI - video signal , but managed with his 16 address lines, allowing an address space of up to 64 kB, also in the basic configuration factory-installed dynamic graphics memory of 16 kB VRAM directly. This consists of a 2 kB image repetition memory , a 2 kB color memory or attribute RAM and an 8 kB character set memory, while the remaining 4 kB graphics memory remains unused.

The MOS 8563 also has 37 internal registers . With the help of the registers numerous parameters can be set, for example the number of characters per line, the pixel width, the display mode , the image resolution , the colors for the foreground and background, the cursor settings etc. The native Commodore BASIC V7 .0 of the C128, however, too slow. Therefore, the 80-character graphics chip had to be programmed in machine-level programming languages such as assembly language. The MOS 8563 also masters a number of picture formats, including the television standards PAL and NTSC.

The MOS 8563 has a color depth of 4 bits and thus a palette of 16 colors, whereby the color values can be programmed via the color memory or the attribute RAM. Although the MOS 8563 does not allow the display of sprites , and is therefore only conditionally fit for the game programming, but allows for a smooth scroll (English smooth scrolling ) in a horizontal and vertical direction. In addition, the MOS 8563 is able to move raster graphics and bobs (abbreviation for blitter objects ) across the screen. For this purpose, special shift commands (English block movement commands ) are available, which allow the fast copying and transfer of related memory contents (English Bit Block Image Transfer ).

Text mode and high resolution graphics

The registers of the MOS 8563 are set using the system routines for screen output so that it is possible to switch between a text mode with a standard setting of 80 × 25 characters suitable for word processing and a graphics mode with a standard resolution of 640 × 200 pixels.

In text mode, the MOS 8563 has both a character set with uppercase and lowercase letters and a graphic character set, which, unlike the C64, can all be displayed on the screen at the same time. Flashing, underlined or inverse letters can be displayed by changing the attribute RAM. Just like the other 8-bit computers from Commodore, the MOS 8563 also uses the CBM-ASCII character set, which works with a dot matrix of 8 × 8 pixels per character, in the standard setting, provided no country-specific character set is activated . In 80-character mode, this is first copied from the character set ROM into the character set memory belonging to the graphics memory, which is why the desired characters only appear on the screen with a short delay. The size of the letter matrix can also be changed. Up to 32 × 8 pixels per character are possible.

In the graphics mode, the basic configuration of the C128 with its preset 640 × 200 pixels achieves a standard resolution that is equal to the much more expensive 16-bit computers IBM-PC and the NTSC version of the Amiga 1000. In this resolution, however, monochrome bitmap graphics already consume the entire 16 kB of VRAM of the early model variants C128 and C128D. Multi-colored bitmap graphics or higher resolutions require an expansion of the dedicated graphics memory.

In addition, there is - as with the computers of the Amiga series - an interlace mode , which is neither supported by the operating system nor used with noteworthy regularity by professional software , which allows the display of up to 80 × by using two offset fields with, however, reduced image quality 50 characters and a resolution of 640 × 400 pixels are permitted. For this purpose, both the refresh memory and the color memory are doubled to 4 kB each, at the expense of the graphics memory area not used by the operating system. In principle, slightly higher resolutions than the mentioned 640 × 400 pixels are also possible in the interlace mode, for example 640 × 536 pixels.

MOS Technology 8568

In the C128D-CR, which has a fully expanded graphics memory of 64 kB VRAM ex works, an unrestricted software-compatible further development of the MOS 8563 called MOS Technology 8568 (MOS 8568 for short) with identical graphics performance was used. In the new graphics chip, however, logic functions are integrated that were fulfilled by external components in the previous models C128 and C128D and were connected to the original MOS 8563 via glue logic . Due to the higher degree of integration, Commodore saved manufacturing costs with the introduction of the MOS 8568 without risking any loss of performance, reliability or software compatibility. In addition, the MOS 8568 has an additional, a total of 38 registers. This enables the use of an IBM PC-compatible EGA monitor. As the pin assignments differ, the two versions of the VDC cannot be interchanged.

Text mode and high resolution graphics

The capabilities of the MOS 8568 for text output are the same as those of its predecessor. Due to the graphics memory, which has been enlarged to 64 kB VRAM, even higher resolutions can be generated in graphics mode with the MOS 8568 than with the MOS 8563 in the basic configuration with 16 kB VRAM. Provided that the graphics memory is fully expanded, these even higher resolutions can also be implemented with the MOS 8563 on the older model variants C128 and C128D. However, this requires careful coordination of the VDC registers. For example, resolutions of 720 × 350, 720 × 400, 750 × 300 or 750 × 400 pixels can be achieved.

In addition, numerous other image formats can be implemented. The game of skill Super-Vectors , which appeared in 1988 for typing in a computer magazine and was inspired by the multi- Oscar- nominated science fiction film classic Tron from 1982, works with a resolution of 736 × 354 pixels. In interlace mode, resolutions of 750 × 600, 752 × 600, 640 × 720 or 720 × 700 pixels can even be achieved with the help of 64 kB VRAM.

MOS Technology 8564/8566/8569

The second 8-bit graphics chip used in the C128 and responsible for the 40-character screen was produced in three versions with 48 connection pins each. The version corresponding to the NTSC standard was named MOS Technology 8564, the version compatible with the PAL-B television standard became MOS Technology 8566, and the version compatible with the PAL-N television standard common in Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay finally became MOS Technology 8569 designated. All three variants of the 40-character graphics chip are better known under the collective name VIC IIe.

The VIC IIe has a color depth of 4 bits, so it can display up to 16 colors and eight sprites in three different sizes on the screen at the same time, depending on the selected text or graphics mode. Apart from a few extensions and eight additional connection pins on the DIP housing, the VIC IIe is almost identical to the VIC II graphics chip used in the C64. The two graphics chips differ, for example, with regard to the text and graphics modes supported by the operating system and the ones used for screen output Space not significantly different from each other.

Like its predecessor, the VIC IIe has two text modes with 40 × 25 characters. In plain text mode (English text mode ) a dot matrix is per character of 8 x 8 pixels into two freely selectable colors for the foreground and background for use while in the multi-color text mode (English multicolor text mode ) per character only 8 × 4 pixels with double width can be used, but for the foreground three options for color selection are available at the same time. In addition, multi-colored bitmap graphics can be generated with a resolution of 320 × 200 pixels in two colors (English high-resolution mode ) or 160 × 200 pixels with double width in four colors (English multicolor mode ). The screen structure requires 8 kB of RAM in each of the two bitmap graphics modes, which is subtracted from the main memory. The newly added functions of the VIC IIe include an extended keyboard query, control of the system clocks and the ability to let the CPU work with a doubled clock frequency of around 2 MHz when the video signal is switched off.

The 40-character graphics chip of the C128 can handle both raster line and sprite collision interrupts and is therefore suitable for programming games. In addition, the VIC IIe has a 14-bit address bus with an address space of 16 kB, which is created by using two additional registers from the I / O module MOS Technology 6526 (MOS 6526 for short, also called CIA 2 by the C128 development team ) ) can be expanded to 64 kB. In contrast to the fixed color RAM, the graphics memory used for the screen layout and the character set RAM can be moved in the computer's main memory.

The VIC IIe also works with the CBM-ASCII character set typical of Commodore computers , which goes back to the manufacturer's first desktop computer - the all-in-one computer Commodore PET 2001 from 1977 - and also in all subsequent Commodores -8-bit home computers of the 1980s was used. Due to its limitation to a maximum of 40 characters per screen line, the VIC IIe is largely unsuitable for office work. In contrast to the 80-character mode, the character set consisting of alphanumeric characters and block graphic symbols is read out by the VIC IIe directly in the character set ROM.

Sound chip

MOS Technology 6581

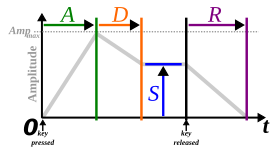

With the MOS 6581 developed in 1981 under the direction of Bob Yannes , the C128 and the C128D have the same 8-bit sound chip as their predecessor, the C64. Under the abbreviation SID (English Sound Interface Device ), the innovative and flexible MOS 6581 has achieved fame and is even considered a “small revolution in the home computer sector”. The sound chip has three individually programmable tone generators , each consisting of a tone oscillator with an integrated waveform generator , an envelope generator and an amplitude modulator . The tone oscillator may generate four digital waveforms ( sawtooth waves , square waves , triangle waves , as well as white noise ) and is also for the pitch and timbre responsible. In cooperation with the envelope generator, the amplitude modulator regulates the volume and the ADSR parameters for increase, decrease, hold and release ( attack, decay, sustain, release ). On the output side, the SID also has a programmable analog sound filter that works with the method of subtractive synthesis for the generation of more complex dynamic timbres through the use of low-pass , high-pass and band-pass . Unlike the C64, the SID can the C128 about the six commands ENVELOPE, FILTER, PLAY, SOUND, TEMPOand VOLthe Commodore BASIC V7.0 comfortable programming.

In addition to generating sound, the SID was also used to control input devices such as paddles or mice and to generate random numbers .

MOS Technology 8580

While the older version MOS 6581 , implemented in NMOS logic , was installed in the C128 and C128D , the C128D-CR came with the MOS Technology 8580 (MOS 8580 for short), a further developed, but fully downwardly compatible variant of the SID with lower operating temperature, less noise and clearer sound by correcting the filter strength. In the US trade press, the MOS 8580 was also referred to as the "Hi-Fi version of the C64 SID chip" due to these properties.

Memory management modules

The C128 has two different memory management modules which are used to control access to the main memory of the computer.

MOS Technology 8721

The MOS Technology 8721, also known as Programmable Logic Array (PLA for short) and equipped with 48 connection pins, is a programmable logic arrangement . The PLA acts primarily as an address manager and generates, among other things, a. all chip select signals for the RAM or ROM chips and the 40-character graphic chip VIC IIe, controls write access to the color RAM or DRAM with the help of a buffer and regulates the direction of data flow on the data bus.

MOS Technology 8722

In addition comes in the C128 also called the Memory Management Unit known (short MMU) memory management unit MOS Technology 8722 is used. The task of the MMU, which is also equipped with 48 connection pins, is to support the two main processors in managing the 128 kB working memory by means of address memory switching ( bank switching ). This support is necessary due to the 16-bit address bus structures of both CPUs, as these limit their address space to 64 kB each. To fulfill this task, the MMU generates not only the control signals for the various operating modes but also the selection signals for the RAM or ROM memory banks of the computer, so that it is possible to switch back and forth between them. The volume of the individual memory banks corresponds to the maximum size of the address space of 64 kB that can be individually controlled by the two main processors. The MMU can manage a total of 1 MB RAM, 96 kB internal ROM and 32 kB external ROM. The address translation is carried out in the 17 registers of the MMU.

I / O modules

The C128 has two identical I / O modules, also known as interface adapters. They are known under the abbreviation CIA (English Complex Interface Adapter ) and regulate the data streams occurring in the context of input and output operations via the joystick connections, the keyboard, the cassette connection, the user port and the serial interface. The two I / O modules of the type MOS Technology 6526 are equipped with 40 connection pins, have 16 individually programmable input and output lines and can be clocked with a clock frequency of up to 2.04 MHz. In addition, the two interface adapters have an 8-bit shift register for the serial input and output of data, a 24-hour clock and the ability to transfer 8-bit or 16-bit data with handshaking ) during read or write operations.

MOS Technology 6526 - CIA 1

The first of the two interface adapters, which is also referred to as CIA 1 in the technical documentation of the C128 to avoid confusion, is for the one to be processed via the joystick sockets, the keyboard and the serial interface in the faster 2 MHz mode - and output operations responsible.

MOS Technology 6526 - CIA 2