French cavalry in World War I

The French cavalry in World War I played only a minor role in this conflict. The mounted soldiers were increasingly ineffective in the face of the firepower of machine guns and modern artillery . The various units of this branch of arms were therefore used almost exclusively for reconnaissance or patrol, even when the staffing level was at its peak at the beginning of the war. Mainly deployed in the western theater of war, the regiments were quickly reduced or reorganized. At the beginning of autumn 1914, the beginning of the trench warfare required a rethinking of the use of cavalry. Some of the regiments had to give up the horses and were incorporated into the newly formed "Divisions de cavalerie à pied" (cavalry divisions on foot). Here they were used as regular infantry. With the resumption of the War of Movement in 1918, the cavalry was revived, but found itself again in the role of mounted infantry.

However, a number of the regiments were deployed in the other theaters of war, where they continued to play the role of classical cavalry, for example in the Maghreb , Southeast Europe or the Middle East .

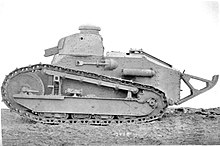

At the same time the age of mechanization began in this period; the French cavalry was first equipped with the Automitrailleuses .

Pre-war situation

At the beginning of the war, several different types of cavalry existed in the French armed forces. They differed in name, uniform and tradition. The cuirassiers and dragoons belonged to the heavy cavalry, on the other hand the "chasseurs à cheval" ( hunters on horseback ) and the hussars were counted as light cavalry. Then there were the Chasseurs d'Afrique and the Spahis , who formed the light cavalry of the armed forces in Africa.

The difference between heavy and light cavalry was on the one hand the horses; the heavy cavalry rode Anglo-normand horses, while the light cavalry was equipped with Anglo-arabe or barbel horses .

For the chasseurs and hussars, the riders theoretically had to be between 1.59 and 1.68 meters tall and their body weight was limited to 65 kilograms. The dragoons could not be taller than between 1.64 and 1.74 meters and weigh no more than 70 kilograms. A height of between 1.70 and 1.85 was required for the cuirassiers, the maximum weight was not allowed to exceed 75 kilograms. A minimum height of 1.56 meters was required for fittings , saddlers , armourers and tailors of the light cavalry.

At the beginning of 1872 and 1913 there was a reorganization of the military service, which also affected the cavalry. Military service was fixed for five years and the conscription system was retained. In 1889 military service was shortened to three years; With the law of March 21, 1905, military service was again reduced by one year to two years. However, this posed problems as it was felt that two years was not enough time to properly train the cavalrymen. As a result, the “Law of the Three Years” (Loi des trois ans) was passed in 1913 , which satisfied the critics. More attention was paid to the composition of the cavalry than to that of the infantry. An example is the garrison in Libourne with the "15 e régiment de dragons" and the 57 e régiment d'infanterie . In 1914, the cavalry regiment had a total of 619 men, 32 officers (4.5% of the staff) and 59 non-commissioned officers (8.3% of the staff); In contrast, the infantry regiment was 3,039 men strong, with 60 officers (1.8% of the staff) and 179 non-commissioned officers (5.4% of the staff). The members of the cavalry also had better chances on the military career ladder; the number of noble officers was twice as high, with 20% in the cavalry and 10% in the infantry.

- Cavalry standards 1914

- Cuirassiers

| I. | II. | III. |

|---|---|---|

- dragoon

| I. | II. | III. |

|---|---|---|

- Hussars

| I. | II. | III. |

|---|---|---|

- Hunters on horseback

| I. | II. | III. |

|---|---|---|

- African cavalry

| I. | II. | III. |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Armament and uniform

The entire cavalry was armed with the saber, the heavy cavalry wielded a straight blade and the light cavalry a curved blade.

The French cavalry used several models of sabers in 1914: Model 1854 with a straight blade 1,000 mm in length, which was shortened in 1882. For the cuirassiers the saber was now 950 mm long and weighed 1,340 grams without the scabbard, and that for the dragoons was 925 mm long with a weight of 1,320 grams without the scabbard.

The saber from model 1822 with a curved blade (length 920 mm) was shortened to 870 mm in 1884 and the scabbard was provided with only one support ring, the version with a straight blade was shortened to 870 mm. The weight was now 1,080 grams.

The model 1882 and 1896 sabers were considered too heavy and were mostly used for educational purposes. Since the officers had to pay for their own armament, they often preferred to buy them from private manufacturers instead of buying the M 1896 and M 1822/82 sabers from state depots. However, these models did not always meet military standards.

The lance had disappeared from all cavalry regiments in 1871, but was reintroduced into the Dragoons in 1890 in response to the 1889 equipping the Prussian Uhlans with this weapon. The light cavalry was only equipped with the lances in 1913. The 12 regiments of hussars and hunters on horseback led them only in maneuvers. The lance model 1890 was made of bamboo, that of the model 1913 was made of tubular steel. The latter was 2.97 meters long.

The armament also included a repeating carbine with a drawn barrel ("Fusil" - also known as a rifle) from the Carabine Berthier 1890 model with a three-shot magazine and a sight up to 2,000 meters; however, the practicable operating range was 100 to 1,000 meters. The soldiers, for whom a carbine was not intended, were equipped with the revolver model 1873 or 1892.

The riders of the heavy cavalry wore a helmet with a crest and a horse tail attached to it. The upper body of the cuirassiers was protected by a two-part armor made of sheet steel, which effectively protected against edged weapons, but not against shrapnel balls or projectiles from rifles or pistols.

In 1900 the entire heavy cavalry wore uniform skirts made of dark blue cloth, collars and piping in Turkish red (garance) - but in white for two dragoon regiments. The trousers were also Turkish red with dark blue passepoils , the coats a bluish iron gray. The trousers of the light cavalry were also Turkish red, but kept in a slightly darker shade. The tunics were light blue, the dolmans were gradually abolished starting in 1900, as they were too conspicuous and offered too easy a target in the field. One began to experiment with a uniform that would compensate for this flaw. As the first unit in 1911, the "12 e régiment de chasseurs à cheval" in Saint-Mihiel was equipped with a reseda-green tunic . From then on, the hussars and hunters on horseback differed in the color of the collars and sleeve flaps - Turkish red for the hunters and dark blue for the hussars.

To replace the shako with a helmet, a dozen different models were tested by several hussar and fighter regiments between 1879 and 1912. There was a choice of helmet bells with or without a crest, made of leather or sheet steel with aluminum or copper fittings . The helmet, approved in 1913, was very similar to that of the Dragoons. The helmet bell was made of sheet steel with a ribbon-shaped decorative field made of brass on the front, on which was, embossed, a hunting horn for the hunters and a five-pointed star for the hussars. A horse's tail was attached to the crest of the helmet. Some regiments received earth-colored helmet covers as early as 1914, although these were not planned for 1919.

organization

The organization of the cavalry units began with the smallest sub-unit, the peloton . This consisted of 30 riders, commanded by a lieutenant or a sous-lieutenant ; four pelotons formed an escadron, 125 to 135 riders strong and commanded by a captain ; four escadrons formed a regiment with about 500 riders under a colonel or a lieutenant-colonel in peacetime . A brigade , commanded by a général de brigade , consisted of two or three regiments, two or three brigades formed a division, which in turn was commanded by a général de division . This system corresponded exactly to that of the German cavalry - with the same advantages. At the same time, however, the cavalry units were equipped with fewer personnel than those of the infantry; a peloton of cavalry corresponded to only one demi-section (half platoon) of infantry, an escadron two sections, a regiment only two companies, a brigade only had battalion strength, and a division corresponded to an infantry regiment.

In October 1870 the Imperial Guard was disbanded by Napoléon III and their six cavalry regiments were renamed. The lanciers were all disbanded in 1871. The remnants of the 1st regiment were transferred to the "14 e régiment de chasseurs à cheval", those of the 2nd regiment to the "10 e régiment de hussards", the 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 8th and The 9th regiment became the “15 e ”, “16 e ”, “17 e ”, “18 e ”, “19 e ” and “20 e régiment de dragons”, the 7th formed the “14 e régiment de chasseurs à” cheval ". After the defeat in the Franco-German War , the system of marching regiments was initially abandoned. The cavalry now consisted of 56 regiments in the mother country and seven in the North African colonies. This involved a total of 12 cuirassier regiments, 20 dragoon regiments, 10 hussar regiments, 14 regiments of hunters on horseback, four regiments of African hunters and three regiments of Spahis. In addition there was the cavalry regiment of the Garde républicaine , which was subordinate to the National Gendarmerie .

The troop strength of the French army was constantly increased in order to adapt to the level of the neighboring Germans. This arms race lasted until 1914, in 1873 14 new cavalry regiments were set up. The law of March 13, 1875 on troop strength provided for a total of 77 cavalry regiments: 12 cuirassier regiments, 26 dragoon regiments, 12 hussar regiments, 20 regiments of hunters on horseback, four regiments of African hunters and three regiments of Spahis. With some of the regiments five cavalry divisions were formed, each of which consisted of three brigades: a cuirassier, a dragoons and a light brigade. The remainder were placed directly under the army corps as brigades, each with a regiment of dragoons and a regiment of light cavalry.

Further increases followed in 1887, regarding the number of active NCOs. In 1913 four new cavalry regiments were set up in response to the German army increase . The total number was now 89 regiments: 12 cuirassier regiments, 32 dragoon regiments, 14 hussar regiments, 21 regiments of hunters on horseback, six regiments of African hunters and four regiments of Spahis. In the motherland the cavalry regiments were housed widely scattered. The barracks (quartiers) were mostly close to the border, with the German border being particularly well considered. The only exception was Paris, where several regiments were stationed as an intervention force. The cavalry also included the Remontendepots , responsible for the horse supply, they were mostly located in the west.

development

After the experience of the Franco-German War, which was still characterized by cavalry attacks, such as the Battle of Wörth and the Battle of Mars-la-Tour , the attack tactics of the cavalry were changed in 1876 and 1882. The frontal attack was now abandoned and the priorities in the reconnaissance and patrol service were set. At the same time, the version of an offensive approach on a smaller scale was preferred.

Several tasks have been assigned:

“The cavalry informs the command staff, covers the deployment of the other weapons and protects against hostile surprise attacks. She is constantly looking for the opportunity to intervene in actions in a supportive manner and collaborates in the attacks of the infantry.

She pursues her to the extreme; in retreat she completely sacrifices herself to give the other troops time to break away from the fight.

Attacking on horseback with bare weapons, which alone brings rapid and decisive results, is the main task of the cavalry. The fight on foot becomes necessary if the situation or the nature of the terrain prevents the fight on horseback and thus the achievement of the set goal. "

All cavalrymen were trained to fight on foot, as a mounted rider with a height of about 2.5 meters offered an attractive target. It was therefore often preferred to leave the horses under guard in the background, while the dismounted riders developed in an open order and were thus less vulnerable. The cavalry divisions still had the bicycle units and artillery for fire support for fighting on foot. Each cavalry brigade included a machine gun platoon with two machine guns St. Étienne M1907 , each assigned to one of the regiments.

“The cavalry training regulations state that fighting on foot must be given more importance in the future than was necessary in the past. In order to implement the full offensive power of the weapon, special attention must be paid to shooting training. "

However, the traditional tasks of the cavalry were still considered important: reconnaissance, guerrilla warfare, covering marching columns and protecting the camps against surprise attacks. In 1881 Général Gaston de Galliffet wrote :

“In modern warfare, cavalry combat is secondary, while exploration and safety are paramount. Although a cavalry division forms a concentrated mass when attacking, such an opportunity will seldom be found. "

- Pre-war maneuvers

A mitrailleuse St. Étienne modèle 1907 the dragoons in position (1913)

At the beginning of the 20th century, the French cavalry showed an interest in various types of motorization available. By the beginning of the war in 1914, experiments had been carried out with a few automobiles that had been converted into Automitrailleuses. They were the beginning of the mechanization of the French armed forces.

Mobilization plan

In the case of mobilization , this took place according to plans from 1875 to 1914. Accordingly, the necessary troop strength was achieved by calling up the reservists and setting up the reserve regiments. No reserve regiments were established in the cavalry; here the number of escadrons was increased from 500 to 600 men and the number of escadrons for most regiments was increased from four to six. According to Plan XVII of 1914, some of the cavalry was directly subordinated to each of the major units. The 21 army corps each received six escadrons from the light cavalry. The 1st to 4th Escadron remained together under the corps command, while the 5th and 6th Escadron were each assigned to one of the two divisional commands of the corps. Each infantry regiment was assigned a peloton for reconnaissance purposes. At the same time, each of the 25 reserve divisions was assigned an escadron, which consisted mainly of reservists. The 12 newly established Territorial Divisions each received a part of the 37 Escadrons Territorial Cavalry, which was also intended to protect the communication routes and the fixed places. These escadrons were set up by the military regions (régions militaires) , two each, but not the 19th, 21st, 6th and 20th RM, which each set up only one escadron. The first Escadron corresponded to the type of light cavalry, while the second Escadron consisted of dragoons.

The regiments that were not divided (especially the cuirassiers and dragoons) belonged to the 10 existing cavalry divisions - each to three brigades, with the exception of the 10th with only two brigades. To each of these divisions belonged a group of field artillery, each with three batteries and four Canon de 75 mm modèle 1897 field guns . The artillerymen were all mounted and did not sometimes have to ride on the mounts or ammunition wagons, as was usual with the rest of the field artillery. The division also included a group of cyclists (400 men, parked by the hunters on foot), armed with the Lebel Model 1886 rifle , in their light blue uniforms, and a group of pioneers on bicycles. The theoretical mobilization strength of the cavalry division was 5,250 men (which makes it about as strong as the German cavalry division); the mobilization strength of the infantry division, however, was 18,000 men.

In the event of mobilization, it was planned to add one or two cavalry divisions to each field army .

Western front

The Western Front on the territory of France and Belgium was the main area of operation for the French cavalry during the First World War.

At the beginning of the war on the Western Front it was a typical war of movement that lasted from August to November. During this time, the cavalry was still able to live up to its traditional role: reconnaissance and flank protection and, in some places, border security.

Concealment of the march

Drawing by Georges Scott in the magazine L'Illustration from August 29, 1914: "... on the way to Berlin ". The Russian army had 36 cavalry divisions, 10 of which were used against East Prussia and 16 against Austria-Hungary in Galicia.

“During the war of 1870 the cavalry still played an important role, this was especially true for the German border […]. In Germany the doctrine had developed: the next war will be the triumph of the German cavalry [...]. In the face of this precise threat, France actively prepared its cavalry on the offensive to face the storms of the countless squadrons with whose help the enemy dreamed of inundating its territory. "

As a consequence, the cavalry was determined to develop immediately along the border in accordance with the mobilization plan in the first days after the declaration of war, thus shielding and disguising the deployment of the main French forces.

The deployment of the five army corps on the border (2nd, 6th, 20th, 21st and 7th Corps) began on the morning of July 31, 1914 as a result of the general mobilization, but was by order of the government 10 kilometers from the actual border stopped.

The reservists of these corps were ordered to be called up on the evening of August 1st. The first transport trains were used for the shielding troops.

Half of the French cavalry formed the ordered shield immediately before the mobilization was called, and each infantry battalion was assigned an escort squadron:

- the 8th Cavalry Division in the area of the 7th Corps, which extended from Belfort to Gérardmer via the "Secteur des hautes Vosges" .

- the 6th Cavalry Division in the area of the 21st Corps, which extended over the "Secteur de la Haute-Meurthe" from Fraize to Avricourt .

- the 2nd Cavalry Division in the area of the 20th Corps, which extended over the "Basse-Meurthe" from Avricourt to Dieulouard .

- the 7th Cavalry Division in the area of the 6th Corps, which extended over the " Woëvre méridionale" from Pont-à-Mousson to Conflans .

- the 4th Cavalry Division in the area of the 2nd Corps, which extended over the "Woëvre septentrionale" from Conflans to Givet (Ardennes) .

Rapid changes

At this point in time, the 1st Cavalry Division from Paris, Versailles and Vincennes was already being loaded onto the transport trains. (Two regiments of the cuirassiers stationed in Paris were due to leave on July 31st, but were held in the city for one more day by order of the government to counter any demonstrations. They were then unloaded on August 2nd in the vicinity of Mézières .) The division staff was under General André Sordet , plus the 3rd and 5th Cavalry Divisions . Together they formed the cavalry corps that was sent to the Ardennes to protect the left flank of the developing main force. It was also intended to educate people about the Belgian border.

In Paris, the Garde républicaine was entrusted with the tasks of the military police. Since then, the Cavalry Regiment of the Garde républicaine has been used as an escort for the President of the Republic. The last two divisions had to go the longest way: the 10th Cavalry Division came from Limoges , Libourne , Montauban and Castres , the 9th Cavalry Division came from Tours , Angers , Luçon , Nantes and Rennes . On the first day of the mobilization, they were brought up to war and loaded onto the train. (A transport train was needed for each Escadron.) On September 5, the units were unloaded in eastern France. The first units were used to secure the further incoming transports, which lasted until August 18.

As for the cavalry units added to the infantry large formations, these came with the last formations from Africa, with the 37th Infantry Division from Philippeville , the 38th Infantry Division from Algiers , the 45th Infantry Division from Oran and the Moroccan Division. On August 5th, all cavalry divisions were ready for action: the 1st, 3rd and 5th formed the "Corps de cavalerie Sordet" at Sedan, the 4th was in Longuyon with the 5th Army, the 9th was east of Verdun with the 4th Army in reserve, the 7th was with the 3rd Army in the Woëvre plain, the 2nd and 10th divisions with the 2nd Army in Lorraine and the 6th north of Baccarat and the 8th southeast of Belfort in the 1st Army. These ten French cavalry divisions faced ten German cavalry divisions - only one German had gone to the east.

Border battles

The first fights were skirmishes between patrols, the role of which was to educate and interview civilians to obtain information and to take prisoners and thereby identify the opposing units. First, the units were involved in battles that were garrisoned in close proximity to the border. It was the "11 e régiment de dragons" and the "18 e régiment de dragons" that had been monitoring the border between Morvillars and Grandvillars since July 31, 1914 at 05:00 . A battalion of the 44th Infantry Regiment was subordinate to the “11 e régiment de dragons” . On August 2, around 10:00 a.m., a patrol of the Jäger Regiment on horseback No. 5 from Mulhouse , consisting of an officer and eight riders, appeared in front of Joncherey . In a firefight with a corporal body of the 6th Company of the 2nd Battalion of the 44th IR lying here, both Lieutenant Albert Mayer and Caporal Jules-André Peugeot were killed as the first soldiers of the war.

Operations began on August 7th when French troops invaded Upper Alsace. At the head of the 8th Cavalry Division, the 1st Escadron of the "11 e régiment de dragons" passed the border at Seppois-le-Bas at 06:00 . At 11:15 a.m. a patrol of the same regiment was fired at in front of Altkirch , then the entire cavalry brigade came under German artillery fire. After French infantry occupied Mulhouse in Alsace, the Dragoon Brigade was used to monitor the Sundgau and the road to Basel . Lying in Tagsdorf on August 8 , the “11 e régiment de dragons” marched on the following day to Jettingen , the “18 e régiment de dragons” advanced to Uffheim . The general retreat to the fortress Belfort was ordered on August 10th after the French defeat at Mulhouse.

On the heights of Lorraine, the cavalry was also only capable of reconnaissance and to shield a narrow strip. So the infantry should be given the opportunity to build up an effective line of defense. Only the infantry, with the support of the artillery, was involved in real fighting here. The first skirmish among cavalry patrols took place on August 4th. On August 11th the battle took place near Lagarde . The German cavalry rode with two Uhlan regiments, albeit with high losses, a successful attack, while the French cavalry was in the reserve and was not used. Based on the published casualty figures for the Battle of Badonviller and those of the Battle of Mörchingen , it can be determined that the infantry had borne the brunt here. The same applies to Mangiennes on August 10th - it was the infantrymen who faced the Germans in the trenches.

In the offensive movement, most of the cavalry divisions were combined into two provisional corps. On the Lorraine Heights, the 2nd, 6th and 10th Cavalry Divisions formed the "Corps Conneau" in August, with the task of maintaining the connection between the 1st and 2nd Armies, since both armies were separated by the "Pays des étangs" were. For the offensive in the Belgian Ardennes, the 4th and 9th Cavalry Divisions were combined to form the “Corps Subscription” on August 18 and assigned to the 4th Army. After the French defeat in the Battle of Neufchâteau , the corps was disbanded on August 25th. Everywhere the cavalry proved incapable of informing their own armed forces of enemy movements and positions. In Lorraine, she had no contact with the Germans until the morning of August 20, in the battle of Lorraine near Mörchingen and Saarburg . Likewise in the Belgian Ardennes, where two French columns were wiped out by unrecognized German troops on August 22nd during the battle of Longwy .

The "Corps Sordet" in Belgium

In the first days after the mobilization, a cavalry corps was set up at Mézières to cover the left flank of the French army in case the German troops were to deploy through the Belgian province of Luxembourg . The corps consisted of the 1st, 3rd and 5th cavalry divisions under the command of Général André Sordet (Inspector General of the Cavalry) and comprised 72 escadrons with 16,000 riders as well as an air reconnaissance squadron, equipped with Blériot aircraft .

After the Belgian government had given permission to cross the border on the evening of August 4th, the order was given on August 5th at 7:20 a.m. for a reconnaissance mission north towards Neufchâteau , Martelange and Bastogne . The first units reached the Lesse on August 7th . On August 8, Sordet reported German troops in front of Liège . On August 9, the Belgians asked the French cavalry to move north to the Meuse in order to protect Brussels , since at least one German cavalry division was already on its way from Tongeren to Sint-Truiden . On August 11, however, the cavalry corps reported the appearance of massive German formations from the east. The 1st , 2nd and 3rd German Army , with a total strength of about 743,000 men - including five cavalry divisions - continued to advance. The cavalry corps avoided the fight and withdrew to the left bank of the Meuse on August 15th. From now on it was under the command of the 5th Army, whose operational area extended north to the Sambre as far as Gembloux . The commander in chief sent Sordet a letter through the commander of the 5th Army ( Charles Lanrezac ) on September 20 , in which he accused him of failure and notified him of his dismissal. After the defeats at Charleroi and Mons , the corps fell into a general retreat, which lasted from August 22nd to September 6th and led via Maubeuge , Péronne , Montdidier , Beauvais and Mantes to Versailles ; with unsuccessful attempts to stop the German advance (e.g. at Péronne on August 28). Long marches back and forth, sometimes like in a carousel, exhausted the horses in a senseless flight.

"[...] by the way, we are starting to get tired from the lack of sleep and the heat [...] the 24 hours a day saddled with heavy baggage, horses are completely exhausted. As soon as you stop, the poor animals with lost horseshoes and drooping heads stop as if frozen. "

The battle of the Marne

During the Great Retreat (Grande Retraite) , the Sordet Cavalry Corps, together with the British Expeditionary Corps, marched north across France, followed by German forces. The cavalry was no longer able to fight - some of the horses had already died of exhaustion, their riders now went on foot. Meanwhile, on August 29th, Général Cornulier-Lucinière set up a "Provisional Cavalry Division" made up of units that were still available and ready to fight and disbanded on September 8th. In the first days of September the Sordet Cavalry Corps had retreated to the southwest of Paris, the "Corps Conneau" (4th, 8th and 10th Cavalry Divisions) was with the British and the 5th Army, while the 9th Cavalry Division was with the 4th Army stopped. Their task was to maintain the link between the armies and to hide the gaps in the front.

On August 31, Capitaine Charles Lepic from the “5 e régiment de chasseurs à cheval” of the 5th Cavalry Division from Gournay-sur-Aronde north of Compiègne reported German columns heading south-east towards Paris. The reconnaissance continued in the following days (Capitaine Bertrand was able to steal a staff card) and led to the outer fortifications of Paris. On September 1, the cavalry corps were placed under the command of the military governor of Paris and equipped with new horses. On September 6th they were subordinated to the new 6th Army. On the morning of that day the 5th Cavalry Division had been loaded onto transport trains at Versailles-Matelots station and taken to Nanteuil-le-Haudouin (northeast of Paris). German cavalry had already been reported from Crépy-en-Valois and Senlis . On September 6th, there was a gap of 40 kilometers between the German 1st and 2nd Armies, but this was shielded by two German cavalry corps.

The Battle of the Marne consisted of several stages, in which the cavalry only played a secondary role: the 5th Division in the Battle of Ourq, the "Corps Conneau" in the Battle of Deux Morins and the "Corps L'Espée" (on Set up on September 10 from the 6th and 9th Cavalry Divisions and assigned to the 9th Army) in the battle of Marais de Saint-Gond ( Mailly-le-Camp ). On September 8th, the Corps Conneau and British troops were able to cross the Petit Morin and repel the heads of the German cavalry of the 1st and 2nd Armies. They then reached the Marne at Château-Thierry when the Germans began to withdraw ( Wunder an der Marne ).

Race to the sea

After the fighting on the Marne, the cavalry was consequently deployed in pursuit of the retreating Germans. This could only proceed slowly, however, since the horses were at the end of their strength and therefore only a few stragglers could be captured.

"[...] exhausted in the battle of the Marne, [...] when victory was near [...] the horses were no longer able to transform the retreat of the Germans into an uncontrollable escape."

On September 8, the remnants of the 8th Cavalry Division were ordered to Crépy-en-Valois to carry out an operation behind the German lines in the forests of Compiègne and Villers-Cotterêts . During this undertaking, an escadron of the "16 e régiment de dragons" carried out an attack on a column of motor vehicles on the evening of September 11th, which was transporting planes to the heights of Mortefontaine (Aisne) . First two dismounted platoons opened fire, then a mounted platoon attacked, but was repulsed by fire from a machine gun. On September 10, two horsemen of the "3 e régiment de hussards" near Mont-l'Évêque were able to force 15 scattered infantrymen of the Thuringian Reserve Infantry Regiment No. 94 to surrender and thereby capture the flag of the 2nd Battalion. The Capitaine Sonnois and the Maréchal-des-logis Noury made four prisoners and brought the captured flag to Senlis .

The pursuit was broken off from September 14th and the exhausted French cavalry halted. The 10th Cavalry Division had pushed into the gap between the 1st and 2nd German Army on September 14th and 15th, crossed the Aisne at Pontavert , reached the Camp de Sissone and then retreated. On September 17, Général Marie Joseph Eugène Bridoux , cavalry corps commander, who was traveling with his staff in motor vehicles, was caught in a fire by German cavalry near Pœuilly . He and part of his staff fell.

The race to the sea made the majority of the cavalrymen "mounted infantry", forced to move into defensive positions and wait for the regular infantry to arrive. Six of the ten cavalry divisions were on the left wing, only the 2nd cavalry division remained in the Woëvre plain. All available means were used to continue the battle: on September 15, under the command of Général Antoine Beaudemoulin, a new "Provisional Cavalry Division " was formed from the remnants of the "Brigade Gillet" and the reserve cadrons. This division was deployed on September 25th on the Somme, only to be disbanded on October 9th. It was the period in which the cavalrymen attacked with the lance on foot because they did not have bayonets : for example, on October 20th near Staden by two escadrons of the "16 e régiment de dragons" and the "22 e régiment de dragons" . On September 30, two cavalry corps were assembled on the left wing of the front and deployed at Arras : the 1st Cavalry Corps with the 1st, 3rd and 10th Cavalry Divisions under the command of Général Conneau and the 2nd Cavalry Corps with the 4th, 5th and 6th Cavalry Divisions under Général Antoine de Mitry .

On October 5, in Lens (Pas-de-Calais), a cavalry corps group (Groupement de corps de cavalerie) was formed from these two corps and placed under the command of Général Conneau. The group was assigned to the 10th Army and was immediately used in the Battle of Artois near Aix-Noulette and Notre-Dame-de-Lorette . On October 7th, the group was initially disbanded due to unsuccessfulness, but was taken back into service on October 12th at the Leie - only to be finally disbanded on October 16th. After the start of the trench warfare, the cavalry was no longer useful for reconnaissance, which is why this task was then transferred to the aircraft. Bringing in prisoners for questioning was left to the franc tireurs and their guerrilla tactics.

Trench warfare (1915-1918)

The stabilization of the front in autumn 1914 led to trench warfare, which turned into a kind of massive siege. The cavalry was out of place on this battlefield, criss-crossed by trenches and barbed wire, riddled with shell holes.

In anticipation of the breakthrough

For each of the Allied offensives - the 1915 Winter Battle of Champagne , the Loretto Battle , the Battle of Artois and the Autumn Battle of Champagne , 1916 the Battle of the Somme , 1917 the Battle of the Aisne and the Battle of Cambrai - the cavalry divisions were im Concentrated back of the front in order to push through the front and widen the gaps in the front. (The British did the same with their cavalry divisions of the Indian cavalry.) On September 2, 1915, the 3rd Cavalry Corps was established with the 6th, 8th and 9th Cavalry Divisions under the command of Général de Buyer (again on December 28, 1916 dissolved).

For example, in 1915, seven cavalry divisions stood ready for the autumn battle in Champagne: the 3rd cavalry corps ( 6e , 8e and 9e cavalry division) behind the 2nd army, the 2nd cavalry division and the 2nd cavalry corps (4th, 5th). and 7th Cavalry Division) behind the 4th Army. (During the Battle of Artois, the 1st and 3rd Cavalry Divisions and a Spahi Brigade were positioned behind the 10th Army.)

On September 28, the German lines were broken, the 8th Cavalry Division was to move south to Perthes-lès-Hurlus and the 5th Cavalry Division to the north on Souain . However, the German resistance stopped these actions.

- The cavalry of the African Army in the reserve

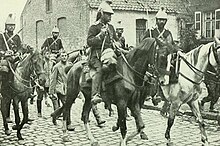

“Spahis algériens” in Veurne

Change to the battle trenches

Despite the trench warfare that was firmly established, another cavalry attack was carried out on September 25, 1915 during the autumn battle in Champagne. After the German main battle line had been fought down, the "20 e hussards" assigned to the 20th Army Corps was sent forward in the morning in the hope that it could overrun the 2nd German line. The commander of the 7th Army Corps, Général de Villaret, sent the “11 e chasseurs á cheval” north of Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand 10 minutes behind the attack lines of the 37th and 14th infantry divisions at 09:25 . To prepare for the attack of the “11 e chasseurs á cheval”, a detachment of 80 horsemen and four pioneers was deployed, who carried out leveling work in the nights from September 3rd to 19th, built temporary bridges to cross the trenches and three breaches in the French wire entanglements cut. The work department was divided into three groups: the people with the wire cutters, the levelers and the bridge builders (they should then also throw the bridges over the German trenches). On September 25th, at 5:30 a.m., the regiment gathered in a small wood. At 8:50 am, the commandant, Colonel Durand, set up three columns. on the right the 1st and 2nd escadron, in the middle the 3rd and parts of the 5th escadron and on the left the 7th and parts of the 5th escadron. Each column marched in a row, the groups 25 meters apart. At 09:15 the columns were at the exit of Saint-Hilaire. The Colonel sat at the head of the middle column, and at 9:25 AM the order to attack came.

“The three columns galloped over the first moat bridges, which were immediately shielded by the artillery. The German artillery shortened its fire the further the columns advanced. As soon as the columns reached the enemy trenches, they were taken under massive rifle and machine gun fire. A number of the horses were killed or injured. The latter galloped in all directions, jumping over the trenches or falling in and blocking them. The injured riders, who could still walk or crawl, tried to get into the trenches occupied by the Zouaves or Tirailleurs of the 37th Infantry Division. Despite the murderous fire that decimated the tips of the escadrons, they got as far as the German wire entanglements. At the head of the right column, Sous-lieutenant Preiss and his group jump from the horses, drag the Zouaves and tirailleurs along and penetrate the third trench, where he is killed. At the head of the middle column, Lieutenant Legrand and his group can occupy a section of the trench. At the head of the column on the left, Lieutenant Tézenas was shot in the head at the German wire barn. The Capitaine Levenbruck realized that the Colonel and the Lieutenant-Colonel were no longer mounted. He took command of the remnants of the regiment and led them back to St-Hilaire. [...]

In this attack, the staff and the three escadrons at the top (especially the 5th escadron) had the heaviest losses in people and horses. The three escadrons of the second line (2nd, 4th and 7th escadron) suffered less. The injured riders were rescued and cared for with great difficulty. Several injured horses wandered around or fell into the trenches, where they perished. "

The labor department, although severely decimated, remained in service with the infantry until the next morning. From September 26th to 29th the regiment stayed in the front to occupy the German trenches taken by the infantry and to wait for a new task. On September 29, the army corps renounced another use of the cavalry on horseback and pulled the remainder of the regiment from the front.

Other missions

No longer in combat use on horseback, other important tasks remained for the cavalry, such as the control of the supply routes or police tasks in the combat and rear areas as a substitute for the national gendarmerie .

In order to compensate for the emerging inactivity, the cavalry regiments regularly went into the foremost battle trenches to do infantry service. The dismounted riders of the 10th Cavalry Division occupied the Leimbach and Burnhaupt-le-Haut sectors together with the Territorial Infantry for most of 1915 . During the autumn battle in Champagne, the dismounted riders and the artillery battery of the 2nd Cavalry Corps were subordinated to the 6th Army Corps. Of the total of 1,300 men, 201 were killed, 714 wounded, and 484 were missing.

In 1917, during the period of mutiny and strikes, the cavalry was relatively exempt from the events because of their prestige and the manner in which they were recruited. However, the "25 e régiment de dragons" was one of the first to sing the Internationale on May 28, 1917 in its garrison in Vendeuil . To maintain order, the Dragoon Brigades of the 1st Cavalry Corps were deployed against the mutinous units at the end of May. After that, they were alternately relocated to the large industrial centers in order to participate in police operations and to monitor the return of holidaymakers in the train stations and depots.

Finally, the idle cavalry units were called in to work, for example to build trenches or to make fascines . They also had to help out in the fields; Message from a brigade to the 10th Cavalry Division:

"The regimental commanders are authorized to lend horses to civilians to make their work easier."

They were also used for leveling work in the fortified regions, such as the “11 e régiment de hussards”, which worked on the Fort de la Chaume in Verdun , or the “22 e régiment de chasseurs”, which established an airfield in 1915.

Blatant changes

List of further units

In the first months of the war a few more cavalry units were set up, making a total of 96 regiments:

- 12 cuirassier regiments

- 33 regiments of dragoons

- a mixed dragoon / hussar regiment

- 22 regiments of hunters on horseback (the 22nd was a marching regiment)

- 16 hussar regiments (No. 1 to 14 - No. 16 and 15 as marching regiments)

- 7 regiments of African hunters (No. 1 to 6 - No. 8 was a marching regiment)

- 4 regiments of African Spahis

- 1 March regiment of Moroccan Spahis

At the end of August 1914, the military governor of Paris scraped up everything that could still be found and with it set up a provisional cavalry brigade with two regiments from the reservists in the depots of the Paris military region. These were commanded by some officers from the cavalry school in Saumur . On August 25, the "Régiment mixte de cavalerie" (mixed cavalry regiment) was formed from the reserve groups of the "15 e régiment de dragons" and the "8 e régiment de hussards" as the "Régiment mixte de marche de cavalerie" (mixed cavalry marching regiment ) set up. It was disbanded on December 31st. On August 26, 1914, the "33 e régiment de dragons" was set up. The 7th escadrons of the "6 e ", "23 e ", "27 e " and "32 e régiment de dragons" were used. The regiment had its depot in Vincennes and Versailles , it was disbanded on January 20, 1916.

On October 9, 1914, another temporary cavalry brigade was set up on the Meurthe. It consisted of the divisional squadrons of the “6 e régiment de hussards” and the “10 e régiment de hussards”. The "Régiment des hussards de reserve B" was renamed on August 19, 1915 initially to "17 e régiment de marche de hussards", but was dissolved again on January 7, 1916. In December 1914, the "Matuzinski Brigade" was set up to complete the 10th Cavalry Division. This brigade was renamed "23 e brigade légère" in April 1915 . The marching regiment of the "12 e régiment de hussards" was set up on December 12th and formed together with those of the "5 e régiment de hussards" and the "6 e régiment de hussards" the "Groupe d'escadrons de réserve de 71 e division d'infanterie ”. The recruit depot of the "3 e régiment de chasseurs à cheval" formed an escadron on foot on June 29, 1915. All of these units were merged on July 30, 1915 to form the “16 e régiment de marche de hussards” (16th Hussar March Regiment). On January 7, 1916 it was dissolved again. The "Régiment de marche de chasseurs à cheval" was formed on December 14, 1914 from the 6th escadron of the "11 e régiment de chasseurs à cheval", the 5th escadron of the "14 e régiment de chasseurs à cheval" and the 11th. Escadron of the "16 e régiment de chasseurs à cheval" set up. In 1915 it was renamed “22 e régiment de chasseurs à cheval” and on January 4, 1916 it was dissolved.

Conversions

In the course of the conflict, cavalry units had to surrender their horses and were converted to cavalry riflemen ( unités à pied - units on foot). They were given different uniforms, different armaments and a different task.

In October 1914, each cavalry division had received a "light group" (Groupe léger) . It consisted of an infantry regiment of three battalions, with an escadron tribe on foot in each of the division's six regiments. In June 1916 most of the ten "groupes légers" were incorporated into the cuirassier regiments. On June 1, 1916, the "1 er régiment léger" (1st light regiment) - an infantry marching regiment of three battalions with 65 officers and 2,474 men - was set up. Each battalion consisted of two escadrons. The regiment had three machine gun companies (three officers and 123 men each). It was formed from the "Groupes légers" of the 2nd and 10th cavalry divisions, a reserve cadron of the "29 e régiment de dragons" and some smaller contingents of the Chasseurs à cheval . The officers were all from the cavalry, the commander was a colonel of the cavalry. The regiment was assigned to the 2nd Cavalry Division and was deployed in the front at Seppois-le-Haut on the night of July 1st. This unit was disbanded as the only one of its kind on August 15, 1917 and replaced by a cuirassier regiment on foot.

In May 1916 the 4th, 5th, 8th, 9th, 11th and 12th cuirassier regiments had to surrender the horses to the artillery; they were converted to infantry units as "regiments de cuirassiers à pied". At first each of the regiments belonged to a cavalry division, but then in December 1917 and January 1918 the "Divisions de cavalerie à pied" (cavalry division on foot) was formed. The 4th, 9th and 11th cuirassier regiments on foot fought in April 1917 while taking the mill of Laffaux during the Battle of the Aisne.

On November 11, 1915, 48 escadrons were withdrawn from the divisions and disbanded. On December 31, 29 Escadrons Dragoons were disbanded and replaced by the "Groupes légers à pied" (Light groups on foot). On June 1, 1916, the 9th and 10th Cavalry Divisions, on August 5, 1916, the 8th and in July 1917 the 7th Cavalry Division were dissolved. A number of the officers were transferred to the infantry, artillery and airmen. The unnecessarily high workforce was thus somewhat reduced in the course of the conflict: from 102,000 men (3.7% of the total workforce) in 1914 to 91,000 men (3.2% of the total workforce) in 1918, while all other branches of arms continued to increase.

Change in uniform and armament

At the beginning of the war, the cuirassiers moved out in bare breast and back armor, the riders of all branches of the army wore the same helmet with a comb and a horse's tail, which was covered with an earth-brown cover. On October 16, 1916, the red trousers of the light cavalry were replaced by those of blue color. In general, it was ordered as early as December 1914 that all riders had to wear the same uniform as the infantry - which was to be completed by the end of 1915. From June 1915 the steel helmet (model Adrian) was issued, the previous headgear was no longer used in combat. On October 16, 1915 it was determined:

"All cavalry units at the front, including the Chasseurs d'Afrique, must wear the general helmet."

Gas masks were distributed, including those for the horses. The equipment of tools was extensive: The hip came saws and axes to shovels, 94 picks and 20 wire cutters per squadron and the Division inventories, loaded onto three trucks: 260 shovels, 130 hoes, 30 axes, sandbags, barbed wire, etc. The carabiner was replaced in October 1914 by the Mousqueton Berthier modèle 1892 (the former had no device for attaching a bayonet). The carbines were then converted into Mousquetons in 1915 and modified again from 1916 to 1920 by now being given one with five cartridges instead of the three-cartridge magazine. The lance was handed in and the cuirass stored in the depot in September 1915. The firepower was increased by giving each regiment a machine gun platoon, the ammunition equipment on the man was increased from 96 cartridges to 165 (75 in the cartridge pouch on the belt and 90 in a cartridge pouch on the saddle). The units were instructed in infantry tactics and trained on grenade launchers. From March 1, 1916, machine guns of the Chauchat type were issued. Each Escadron received four of the 9 kilogram rifle. Each regiment received 36 shooting cups for rifle grenades of the "Tromblon" type and 1,000 rifle grenades of the "Vivien-Bessières" type per device. 150 incendiary grenades were carried. In addition, there were infantry guns of the caliber 37 mm Canon d'Infanterie de 37 modèle 1916 .

After the pre-war trials, the first motorized and armored vehicles were used. The chassis of civil vehicles were used for this, such as pick-up trucks from Renault , Peugeot , Delaunay-Belleville , De Dion-Bouton or White TBC . These vehicles were lightly armored and were armed with a machine gun, a 37 mm or a semi-automatic 47 mm naval cannon. Even though the latter were intended for the Navy, they were immediately taken over by the cavalry.

The armored car groups were assigned to the cavalry divisions after the formation. The 8th Division received its group in October 1914, the 9th Division in November 1914 and the 7th Division in December 1914. The other divisions were equipped in 1915. In November 1915 the 7th division received a second group, the others in May / June 1916. Among the 17 groups in total, the 10th group was in Romania from August 1916.

Reorientation

“The characteristic of the battlefield is absolute emptiness. Even airplanes can no longer make out gatherings or columns. The cavalry should not be left as the only weapon that walks around the battlefield and thus offers an easy target. The procedure of 'marching and bivouacking' as well as 'fighting' must therefore be fundamentally changed. From now on, the units on horseback that are near the front should operate in open formations, the riders staggered across the area. "

These new texts were used in the units for the theoretical framework of cavalry training, in particular the Instruction sur l'emploi de la cavalerie dans la bataille (Instruction on the use of cavalry on the battlefield) of May 26, 1918. It was decided how many dismounted riders should be used as infantry in the stabilized front and that the cavalry units should be trained in the rules of infantry combat. The regulation defined the cavalry's new priorities:

"1. Speed and mobility are the defining qualities of the cavalry. The missions that are incumbent on her in battle are based on these characteristics that the other weapons do not have in the same way.

2. The tactics of the cavalry must take into account the power of fire in modern combat; its organization and armament enable it to operate at present. The cavalry must therefore also be able to fight on foot in conjunction with the artillery. Nevertheless, fighting on horseback must still be possible and must not be neglected. This mounted battle must be effective against enemy cavalry, also against a surprised infantry in the open country, which is dispersed and demoralized, as well as against artillery on the march or in the position that they attack from the flank or in the rear.

3. The cavalry is a sensitive weapon. Replacing them is difficult and takes a long time. It should therefore not be sacrificed uselessly. It is to be used where its special qualities can be used meaningfully. "

The role of the cavalry in combat is:

- on the offensive:

"[...] to advance the development of the success [...] and, if the expansion has taken place after the breakthrough, to advance it further."

- on the defensive:

"[...] the cavalry must be able to limit the effects of an enemy breakthrough through its own front."

- and:

"[...] to have an enlightening effect in the event of the enemy retreating and to shield the movements of one's own forces."

As part of this new tactic, the cavalry was increasingly assigned the role of mounted infantry. She should fight on foot and be able to move quickly to critical places on horseback (a combination of fire and movement). New in the cavalry divisions was the equipping of light armored vehicles by train or escadron.

The text was written by Général Nivelle in connection with preparations for the battle of the Aisne in 1917: the commander had used his cavalry here to expand a breakthrough in the front.

Return to War of Movement (1918)

In the German offensives of the spring of 1918 ( Operation Michael , Vierte Flandernschlacht ), the cavalry, as mounted infantry, had the task of quickly sealing off any breakthroughs and holding them until the infantry reinforcements arrived. This happened for the first time on March 23, 1918, when the 1st, 4th and 5th Cavalry Divisions had to stabilize the 30 km front from Noyon via Montdidier to Moreuil . Again in April 1918 the 2nd Cavalry Corps of Général Robillot had to intervene in Flanders after the Germans had taken the Kemmelberg , and a third time in May / June with the "Corps Robillot" on the Ourcq and on the Vesle and with the 1st. Général Féraud's cavalry corps after the Battle of the Aisne and the German breakthrough at the Chemin des dames . The Allies' offensives, which began in the summer of 1918, were based on the artillery's successes in smashing German lines without a direct attempt to break through. So there was no pursuit, progress was limited, and the cavalry fought only on foot.

"Ah! Certainly it is no longer a pursuit as in earlier times, one of those hunts in lively pace, which were essentially the work of the cavalry, accompanied by batteries on horseback: dragoons and hussars, driving the columns of fugitives apart, cutting paths and Saber carriages. It is no longer heroic deeds like those of Lasalle and the rivals after the battle of Jena , the annihilation of the Prussian army and the cavalry taking a fortress like Stettin. Fast firing weapons with a long range no longer allow that today. Repeater rifles, light cannons and machine guns work from a long distance and create a zone in which the cavalry can no longer operate. It must be added that the rigid front lines, which do not dissolve even in retreat, counteract the large-scale movements and put an end to the triumph of the heroes of the last century. Today's pursuit takes place gradually, the infantry moves forward in waves, the attacked cover themselves with machine guns and light cannons, which are well protected in covered positions. The attackers slowly work their way forward, taking advantage of cover and cleaning up the area. "

On November 1, 1918, the Allies had six French, three British and one Belgian cavalry divisions on the Western Front. In contrast, there were 209 infantry divisions. The strength of the individual contingents was:

- 66,881 French (plus 633 cavalrymen on the front in Italy)

- 18,894 British

- 6,971 Belgians

- 6,028 Americans

When the ceasefire with Germany began, the 1st Cavalry Corps (1st Cavalry Division on foot, 1st, 3rd and 5th Cavalry Division) was in reserve at Vaucouleurs , where it was preparing to invade Lorraine. The 2nd Cavalry Corps with the 2nd Cavalry Division on foot, the 2nd, 4th and 6th Cavalry Divisions were part of the army group in Flanders and fought on the Lys and the Scheldt. Each of the two corps was assigned one, then two squadrons, a balloon company, four groups of artillery (three with field cannons "75 mm modèle 1897" and one with field cannons 105 mm), three pioneer companies and two groups with Automitrailleuses and Auto-canons (the Auto -canons were armored cars with a 37 mm gun instead of a machine gun, each group had six automitrailleuses or three auto canons).

Other fronts

Some units of the French cavalry - all colonial troops - were almost entirely recruited from North Africa and mounted on Berber horses. They stood on the front lines of the "periphery of the French field of vision". In several cases the wide operating rooms enabled the cavalry there to be more successful than was possible on the western front in Europe, despite the small number of staff there.

Africa - lower Sahara

In French West Africa, the Dakar cavalry consisted of only one Escadron sénégalaise with 119 riders (16 of them Europeans), who had been relocated to Morocco since 1912. In total there were two companies in 1914, each 100 men strong with 130 horses and 15 platoons "Compagnies méharistes saharennes" (border guards) on camels. Each platoon consisted of 60 men and 200 dromedaries . They were subordinate to the so-called "native brigades" (brigades de garde indigène) , a police-like force in strength. The brigade in Tombouctou was mounted on horses, but the brigade in Mauritania was equipped with camels. The latter had been formed as a "Compagnie de garde méhariste" with a strength of between 80 and 100 men from the barberry . In French Equatorial Africa there was only the "Régiment de tirailleurs sénégalais du Tchad", plus six companies of infantry, one escadron to two companies of Méharistes (200 men) and four independent platoons of Méharistes of 30 men each.

The conquest of the German colonies Togoland and Cameroon took place without the participation of the cavalry. Reasons were the condition of the roads and the lack of fodder in the rainforests:

"[...] the animals were not to be used for service in the columns, neither the carrying horses nor the mules of the artillery."

The "native brigades" from Dahomey and Ouagadougou were strong enough to invade Togo in August 1914, while operations in Cameroon could not begin until 1916. The French cavalry troops in the South Sahara were not used for police tasks, with the exception of a small part of the mounted company of the "4 e régiment de tirailleurs sénégalais", which was used outside Dakar as a sanitary cordon during the plague epidemic from May to autumn 1914.

Sahara territories

In the Sahara and the Sahel zone , the French cavalry units were exposed to attacks by the Sénoussis when war broke out , who moved with combat groups from Libya to southern Tunisia, to southern Algeria in the Aïr massif (Niger) and to Ouadaï (northern Chad). In Tunisia, Fort Dahibah and its outpost were repeatedly attacked by the Tripolitans in September / October 1915, June 1916, October / November 1917 and August 1918. During this period, 15 battalions of infantry and eight escadrons Chasseurs d'Afrique and Spahis were stationed in southern Tunisia. In southern Algeria a revolt broke out in the Hoggar and Tassili des Azdjers , in March 1916 groups of warriors from Ghadames (in Fessan ) attacked the Djanet and Fort Polignac posts . Both had to be given up and could not be regained until the end of October. The "Goumiers marocains" and the Méharistes (mainly from the Châamba clan ) could not regain control of the area until then.

In the Aïr massif, Khoassen, a leader of the Sénoussis who had come from Ghat , ordered the siege of Agadez on December 7, 1916 . On December 28, a little more than 20 kilometers to the east, a band of 54 horsemen of Méharistes was massacred. In response to this, the "Commandement supérieur des territoires sahariens" (High Command of the Sahara Territories) was formed on January 12, 1917, subordinated to Général François-Henry Laperrine and the troops were concentrated . At the end of the unsuccessful siege of Agadez on March 3, 1917, the guerrillas were persecuted in the mountains until February 1918. Khoassen was defeated in the Battle of Tamaclak (120 km north of Agadez) from February 14th to 19th. Guerrilla groups that had come from Koufra operated in Chad . Order was restored in Ouadaï and Dar Sila between May and July . The British were now doing this in Darfur . The Tibesti post was given up in August 1916.

Morocco

Another area of operations for the French cavalry during the First World War was in Morocco. Since the establishment of the French Protectorate (Protectorat français au Maroc) in 1912, a number of cavalry units have been deployed to occupy the country, but they could only occupy the Moroccan plains (of Chaouia , Gharb and Saïs ). The Spanish protectorate in the far north was controlled by the Spanish. In contrast, the various mountain peoples of the Atlas were completely autonomous. On August 1, 1914, the French occupation corps consisted of around 88,200 men with a total of 64 battalions and 34 escadrons, of which nine escadrons "Chasseurs d'Afrique", 13 escadrons "Spahis algériens", 11 escadrons "Spahis marocains" (also Chasseurs indigènes - " Local hunters ”), one escadron“ Spahis sénégalais ”and 14 escadrons“ Goumiers marocains ”(Moroccan militias). These were used for what was called "pacification" in France.

On July 27, 1914, the acting general resident in Morocco, Général Hubert Lyautey, received the order from Minister of War Messimy to take the best part of his troops - of the infantry the Zouaves, the Légion étrangère , the colonial infantry etc., as well as the Tirailleurs marocains and the Tirailleurs sénégalais - to contract. On August 6, the "Division de marche d'infanterie du Maroc" was set up in Rabat. It contained two escadrons of the "9 e régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique". A total of 20 escadrons and 52 battalions came from Africa between 1914 and 1918. The strength of these troops on September 15, 1914 was 75,000 men. The "Régiment de marche de chasseurs d'Afrique" was assigned to the 45th Infantry Division, the "Régiment de marche de spahis marocains" to the "Corps Conneau".

The units withdrawn from Morocco were replaced by 19 battalions of territorial infantry. It was the 90th Territorial Infantry Division and an Alsace-Lorraine battalion. The territorial troops were all used to guard ports and villages. Like the active troops, they occupied advanced posts and formed mobile columns. The workforce remained the same, but not the quality of the troops.

By October 1, 1914, 50 battalions and 28 escadrons had arrived in Europe: the cavalry consisted of six from the Chasseurs d'Afrique, 15 from the Spahis algériens, six from the Spahis marocains and 14 Goums mixtes. On July 1, 1919, there were a total of 97,000 men in Europe. They were divided into 62 battalions (some battalions of Zouaves and colonial infantry had already returned) and 32 escadrons: four of the Chasseurs d'Afrique, 22 of the Spahis algériens, one of the Spahis sénégalais and five of the Spahis marocains. In addition there were the 25 escadrons of the Goums and a few Automitrailleuses .

Orient Army

Dardanelles

After the Ottoman Empire entered the war on Germany's side in October 1914, the Allies decided in the winter of 1914/1915 to set up an expeditionary force to take Istanbul . Most of the troops consisted of units from the British Army (Australian, Indian, New Zealand, Royal Marines, etc.). The French provided a 17,000-strong infantry division (the later “17 e division d'infanterie coloniale”). The division had only one cavalry regiment, the March 15, 1915, newly established marching regiment of the Chasseurs d'Afrique, which was assigned No. 8 on July 28, 1915. It consisted of an escadron each from the 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th Regiments of the Chasseurs d'Afrique, a machine gun platoon and a mobile depot. The strength in the list in February 1915 was 31 officers, 715 men, 680 horses, 181 mules and 26 motor vehicles. In addition there was the escort for Général Albert d'Amade, consisting of 16 riders and 18 horses. The units were embarked in Bizerte and Philippeville in March 1915 and sailed via Malta to Moudros on the island of Limnos . After the failure of the naval forces on March 18, 1915 at the Battle of Gallipoli , the French troops were transported to Alexandria from March 25, after they had been in the roadstead since March 18, before Moudros . This promotion ended on March 27th. Without the cavalry, the French troops were put ashore on April 25 and 26, 1915 at Koum Kalé and at Cap Helles. Only the machine gun platoon was involved, as it was assigned to the 6th Mixed Colonial Regiment.

Saloniki

In 1915 a British-French intervention in Serbia was decided, on the one hand to relieve Serbia, on the other hand to persuade Greece and Romania to enter the war on the side of the Allies. The first French soldiers landed in Thessaloniki on October 5, 1915, with the consent of the Greek government. At the Calais Conference in the same year, Joffre had approved three infantry divisions and two cavalry divisions under the command of Général Sarrail as the "Armée française d'Orient" (French Orient Army). When the three infantry divisions had reached their destination between October and November (one came to the Gallipoli peninsula , which it vacated on January 9, 1916), a counter-order from the Minister of War revoked the use of the cavalry in a telegram on October 17, as the Combat zone is unsuitable for larger cavalry operations because of the mountainous terrain. The "Régiment de marche de chasseurs d'Afrique", which had already arrived, was immediately sent on to Egypt.

“[...] the entire area, starting with Skopje on the Romanian border to Gevgelija on the Greek border, is consistently unsuitable for cavalry. The artillery also has considerable difficulties, since there are only a few roads and all the more mountain paths on which even the infantry can only march in a row. It is therefore advisable to replace the cavalry with mountain infantry. "

But after Bulgaria's entry into the war and the Serbian defeat in the winter of 1915, the Orient Army, which had advanced into the Macedonian mountains, had to withdraw again and seek refuge in still neutral Greece. At the beginning of December, the "4 e régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique" arrived in Greece with a group of mounted artillery and formed a cavalry brigade with the "8 e régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique". This was used from December 11 at Dojran as the rearguard of the retreating Oriental Army and then at Kilkis to protect the Camp de Salonique. Sarrail demanded two additional infantry divisions, a cavalry and an artillery regiment, but Joffre did not agree, he only sent the artillery and the "1 er régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique", which was held from February 2 to 5, 1916 in Saloniki Land was set. It was used on the west bank of the Vardar along the way to Bitola .

In March 1916 the skirmishes along the border began; In April / May the Orient Army came into contact with the enemy, the "8 e régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique" was dispersed to support the large infantry units, the "4 e régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique" was on the right wing in the valley von Boutkova and the "1 er régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique" on the left in the Moglénitsa region. The General Sarrail withdrew the "1 er régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique" on August 20, 1916 , as well as two mounted artillery batteries on August 27, and the "4 e régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique" on September 6 . They were all concentrated in the Zeitlik field camp , three kilometers north of Saloniki. In September 1916 an attempt by the Oriental Army by the Bulgarian troops in the mountains was rejected. The front in Macedonia turned into trench warfare.

Albania and Thessaloniki

On October 2, 1916, the "1 er régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique" forced the Greek armed forces in Korça to withdraw, so that the "Republic of Korça" could be installed there. The tensions with the Greek government made it necessary to prevent possible counter-actions. The "1 er régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique", which had taken the left wing on December 8th, was transferred to Kojani on December 12th and stationed a train of armored vehicles in front of Thessaloniki to monitor Kalabaka and Trikala . The "Régiment de marche de spahis marocains" (RMSM) arrived in March 1917 for reinforcement. The four cavalry regiments were combined in Bardi on May 25th to form a cavalry group under the command of Colonel Bardi. This was assigned to the provisional "Division Venel" on June 3, 1917 and entrusted with the control of Thessaly .

The cavalry was now used again at Korça in Albania. The RMSM was transferred to the newly established provisional "Jacquemont Division", crossed the Devoll and took Pogradéts . The riders dismounted and fought on foot as the vanguard between September 8th and 12th, 1917. They took around one hundred prisoners and captured two cannons. After the police operation to confiscate weapons in the Albanian villages, the RMSM crossed the Shkumbin west of Lake Ohrid on October 19, climbed the slopes on the left bank of the river and fought on foot until October 22. The Spahis were withdrawn from the front on November 11, 1917 and placed in the reserve. In February 1918 the cavalry brigade of the Orient Army was set up and subordinated to the Général Jouinot-Gambetta . It consisted of:

- “Régiment de marche de spahis marocains” in Veria and Amyndeo

- “1 er régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique” in Amyndeo, then in April at Camp Samorino north of Naoussa

- "4 e régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique" south of Cernavodă and along the line to Larissa

After the seasonal ceasefire in winter (the depth of snow did not allow for any fighting), the escadrons monitored the retreat of the Russian troops.

On August 1st, the Orient Army still had 3,791 cavalrymen, which were greatly underrepresented with a total of 232,299 men. On July 6, the RMSM was used again in Albania. It operated in the Bofnjë massif.

French-Serbian offensive

When the offensive was being prepared in August 1918, the “Spahis marocains” were pulled out of the front and relocated to Kotori (south of Florina ). The "4 e régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique" was commanded to Sakoulévo, while the "1 er régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique" was deployed in the period from August 14th to September 10th in Transporting sacks of 155 mm grenades from the Dragomantsi depot to the Serbian batteries. On September 15, the day the offensive began, the brigade's three cavalry regiments were concentrated in Bitola.

On September 20, the Bulgarian troops were defeated and retreated to the Bitola plain. The French cavalry brigade, taking advantage of the infantry's successes, penetrated Prilep , which had been evacuated by enemy forces. On September 24th, contrary to the given orders (pursuit of the Bulgarians to the north) the brigade crossed the Baboune and on the 25th the village of Stepantsi was taken. After crossing over the Vardar near Veles , the brigade was deployed in the Yakoupitsa massif, which they crossed with their horses on goat paths within four days via the villages of Drenovo, Paligrad and Dratchevo, before arriving in Skopje on September 29th . Here the “Spahis marocains” were able to take 330 prisoners (150 of them Germans) and capture five 105 mm field guns , two 210 mm mortars , 100 carts with food, a grain train, cattle, etc. After Bulgaria requested a ceasefire on September 26, the brigade pushed through Serbia to the Danube , which it reached on October 24.

Palestine and Syria

In March 1917, some French units were transported to Egypt to take part in the fighting in Palestine on the side of the British " Egyptian Expeditionary Force ". It happened at the request of the French Foreign Ministry that the units should take part in the conquest of Syria. According to the Sykes-Picot Agreement, this part of the Ottoman Empire was to become a French sphere of influence. Three infantry battalions formed the "Détachement français de Palestine - DFP" (French department in Palestine), commanded by Lieutenant-colonel (then Colonel) Philpin de Piépape (formerly commander of the "10 e régiment de chasseurs à cheval"). The cavalry consisted of a peloton of the "1 er régiment de spahis algériens" from Biskra , some of which, however , had to stay in Bizerta in April 1917 because of mumps . The loading took place on June 1, and the transport arrived in Port Said on June 10, to join the main contingent in Khan Younous near Gaza on June 15 . The cavalry's tasks were limited to protecting the lines of communication in Sinai . In November the department was in Deïr Sineïd and in December relocated to Ramallah to protect the Jaffa - Jerusalem railway line .

The détachement was reinforced by the "Légion d'Orient", consisting of Armenians and Syrians. On March 19, 1918, the 5th and 6th Escadron of the "4 e régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique" and three pelotons of the "1 er régiment de spahis algériens" arrived in Port Said . The latter formed the 4th Escadron together with the four pelotons already on site. The 5th escadron of the “4 e régiment de spahis tunisiens” was supposed to provide a final reinforcement . The Escadron was embarked in Sfax on the British merchant ship SS Hyperia , which was torpedoed by the German submarine UB-51 on July 28, 1918 84 nautical miles northwest of Port Said at 32 ° 21 ′ 0 ″ N , 31 ° 25 ′ 0 ″ O . All horses and 19 riders were killed.

On July 17, a marching regiment, the "Régiment mixte de marche de cavalerie du Détachement français de Palestine-Syrie", was set up under the command of the Chef d'escadrons Lebon. It consisted of three escadrons on horseback and one escadron on foot, whose horses had failed, and a machine gun platoon. On March 27, 1918, the entire French armed forces were named "Détachement français de Palestine-Syrie" (DFPS). After the French infantry were concentrated in Mejdel in July , they were subordinated to the 21st British Corps and pushed into the front at Rafat between August 29 and 31. On September 14th, the Escadron came on foot. From August 19 to 24, the cavalry regiment joined the Australian “5th Light Horse Brigade” of the “Australian Mounted Division” in Sarafand al-Amar. On September 1, the regiment had 25 officers (including 23 Europeans) and 692 men (including 517 Europeans).

On the morning of September 19, 1918, the British 21st Corps began the offensive on the Sarona plain . The cavalry immediately advanced north; the French regiment included "Toul Kérem" ( Tulkarem ), took 1,800 prisoners and captured 17 artillery pieces (including an Austrian battery) and 18 machine guns. On the night of September 19-20, the Australian brigade was able to interrupt the railway lines at Nablus and Jenine. On September 21st, the French invaded Nablus after attacking across the gardens and streets. They took 900 prisoners and captured three cannons and nine machine guns. The casualties so far have been seven wounded, the killed horses have been replaced by Turkish prey horses. On September 22nd the regiment was in Jenine, on the 25th in Nazareth and on the 26th in Tiberias . On September 27, it fought on foot to cross the Jordan and was involved in the encirclement of the Turks in Galilee . Fighting followed west of Sasa on the night of September 29th, and on September 30th the roads and railways west and north of Damascus were cut off, bombarding the retreating Turkish columns.

On October 1, 1918, the Desert Mounted Corps and a Bedouin army occupied Damascus while the French moved into Duma (Syria) . The 2nd (mixed) Escadron was also in Damascus. In the days that followed, eight riders died in the hospital.

On October 15, the Turks asked for the fire to be ceased, which led to the Moudros armistice on October 31 . Philpin de Piépape was appointed military governor of Beirut on November 8th . The Escadron was withdrawn from Haifa on foot to provide support and to take over police duties and arrived in Beirut on November 11th by ship. The mixed regiment left Damascus on November 20th and arrived in Beirut on November 24th. At the end of November, cavalry pelotons were in Merdj Adjoun, Hasbaya, Rachaya and Baalbek . On November 16, a peloton of Spahis was stationed in Tripoli . On January 9, 1919 two escadrons (one of them the escadron on foot) were in Beirut, two pelotons Spahis (as escort of the governor) in Latakia , one in İskenderun , one in Tripoli, one escadron in the region of Sidon , Es Sour and Djedeidé. In February 1919, an escadron was garrisoned in Jerusalem. The regiment was named "Régiment mixte de marche de cavalerie du Levant" (Mixed Cavalry March Regiment of the Levant) on October 22, 1919, and then on October 1, 1920 "1 er régiment de cavalerie du Levant" (1st Levante Cavalry Regiment ).

After the end of the war

The four armistices were signed by France

- Bulgaria on September 29, 1918 ( Armistice of Thessaloniki )

- the Ottoman Empire on October 30, 1918 ( Armistice of Moudros )

- Austria-Hungary on November 3, 1918 ( Armistice of Villa Giusti )

- the German Reich on November 11, 1918 ( Armistice of Compiègne )

closed, but this resulted in nothing but a temporary cessation of fire. The state of war remained until the respective peace treaty was signed.

The "Régiment de cavalerie de la Garde républicaine" provided the escort of honor for the Allied delegations during the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 . The cavalry was used in many of the last operations because, due to the high number of professional soldiers in its population, it was not directly affected by the demobilization that was under way.

March to the Rhine

The armistice of November 11, 1918 not only meant the cessation of fire, the German troops also had to withdraw from France, Belgium, Luxembourg and Alsace-Lorraine within 15 days and from the areas on the right bank of the Rhine after a further 15 days.

The French troops crossed the front on November 17th and followed the retreating Germans six kilometers away. Alsace-Lorraine was occupied by the "Fayolle Army Group" (formerly Reserve Army Group), which included the 5th Cavalry Division in the 10th Army. The 3rd Cavalry Division was assigned to the 33rd Army Corps. In the Ardennes, the Maistre Army Group (formerly the Central Army Group) operated with the 2nd Cavalry Division in the 6th Army. The 2nd Cavalry Corps (reduced to the 4th and 6th Cavalry Divisions) remained autonomous. On November 30, 1918, all of Alsace-Lorraine was occupied.

Between December 5 and 13, 1918, the Allied troops occupied their zones of occupation, the French from the Lauter to Bingen , the Americans to Bonn and the British to Düsseldorf , while the Belgians occupied the area up to the Dutch border. On the right bank of the Rhine between December 13th and 17th, bridgeheads in front of Mainz , Koblenz and Cologne with a depth of 30 kilometers were set up. This occupation (against the will of the German government) was carried out by a total of six army corps with 40 infantry divisions (six French) and three cavalry divisions (two French). The 3rd Cavalry Division was stationed west of Mainz and the 4th Cavalry Division southwest of Koblenz in the American zone as a bridgehead reserve.

The 1st and 2nd Cavalry Divisions had been ordered to Paris and Lyon in the winter of 1918/1919 to maintain public order.

Demobilization and occupation