Martin Luther's trip to Rome

Martin Luther (1483–1546) is said tohave wanderedfrom Nuremberg to Rome around October / November 1510 as the companion of an older monk who was not known by name, according to research that had prevailed for a long time. Luther accompanied the negotiator as a socius itinerarius . The travelers would have had to cross the Alps in winter. According to this reconstruction, which is essentially based on Heinrich Böhmer , Luther probablyreturned to Nurembergtowards the end of March 1511 . According to Böhmer, Luther himself almost always indicated the year 1510 as the start of the trip to Rome. The dates of Philipp Melanchthon , Cochläus and those of the Augustinian order historiographer Felix Milensius, all of which cite the year 1511, Böhmer tries to present as implausible.

In this article, Martin Luther's travel route, which can be assumed under this premise, is reproduced. The prehistory is thereby older research assumptions, z. B. those of Böhmer (" older " hypothesis ), presented below, which as the reason for the trip an appointment with Pope Julius II . suspected on behalf of the unruly reform monasteries to which Luther belonged.

Since such a protest cannot be proven and the reason for the trip does not seem plausible from the political point of view, a more recent study by Hans Schneider (“ newer ” hypothesis) assumes that Luther did not leave Wittenberg (not Nuremberg) until a year later on behalf of his mentor Johann von Staupitz and dates the arrival in Rome before the end of November 1511.

The difficult-to-manage alpine crossing in winter would not have been necessary. The return journey from Rome would have taken place at the beginning of 1512 . Soon afterwards, in May 1512, Luther took part in an order meeting in Cologne , at which a compromise was reached on the disputed question of union, which the trip was intended to clarify, which supports the hypothesis of a later date of the trip.

Luther's journey took place during the Italian Wars , more precisely the War of the Holy League (1511–1513). The 1511 by Pope Julius II , Maximilian , Ferdinand II , his son-in-law Henry VIII of England, the Republic of Venice and the Swiss against France, led by King Louis XII. , Closed Holy League, Lega Santa del 1511 initially rectified the situation so that the French troops had to withdraw from the Duchy of Milan on October 4, 1511 .

In March 1513, however, the Republic of Venice switched sides and allied with France, which further complicated the political situation. On June 6, 1513 the Swiss defeated Ludwig XII. in the Battle of Novara and put the Sforza back as rulers in Milan.

prehistory

Martin Luther entered the strict Erfurt monastery of the Augustinian order as a monk in 1505 . For many years there have been two currents in observing the rules of the Order. The "observants" wanted to strictly obey the rules. The "conventuals" wanted to leave it to the convents of the monasteries to allow exemptions from the strict rules. These contradictions led to an order dispute or union dispute that affected the entire order.

The order general Aegidius de Viterbo was directly subordinate to the Pope and had his seat in Rome. General vicars were responsible for larger areas of the order . The German vicar general was Johann von Staupitz. Four provincial vicars were responsible to him. Erfurt belonged to the Saxon province, which Staupitz had also headed from 1510. The order general de Viterbo and the German vicar general Staupitz were both observants. They pursued the plan to merge the convents with a more free interpretation of rules with the observant convents. The observant monasteries resisted this, because they feared a weakening of the observance.

In August 1507, Cardinal Bernardino López de Carvajal was sent from Rome to Germany as Legatus a latere , with exceptional papal powers to settle the religious dispute. Already on December 15, 1507 in Memmingen he issued the bull Bernhardinus, miseratione divina , which authorized Staupitz to enforce the unification of the conflicting monasteries within the Saxon province. At the same time, the opponents of the reunification were forbidden to appeal directly to the Pope. This bull was kept secret by Staupitz for almost three years and only published on September 30, 1510.

Of the 29 monasteries under observation, seven, including Erfurt and Nuremberg, insisted on objecting to the merger and did not accept the instructions of the vicar general. In the fall of 1510, Böhmer accepted a conference of the opposing monasteries in the Augustinian monastery in Nuremberg , in which Luther participated as a representative of the Erfurt monastery. Here it should have been decided that Erfurt and Nuremberg should each send a representative to the Order General in Rome in order to obtain a direct appeal to the Pope against the stipulations of the bull. Nuremberg is said to have appointed an older, experienced monk as the first man whose name has not been passed down; Luther had been nominated from Erfurt.

However, these assumptions, for which there are no sources, raise a number of questions that appear to be resolved by the more recent hypothesis that there was no journey at this point and that Luther did not migrate to Rome until a year later. The main difficulties of the older hypothesis are that there is no evidence for the assumed meeting in Nuremberg and that such an initiative would have been doomed to failure from the start and would therefore have been pointless, especially since the Order General wrote in a letter of July 29, 1510 to the members of the Congregation expressly ordered to obey the Vicar General Staupitz and in case of disobedience threatened to act against the rebels and enemies of the order.

According to older research hypotheses, the two monks set out from Nuremberg between late October and early November 1510. There were few travel arrangements to make, such as creating letters of recommendation and credentials for this mission. Passports were also necessary, because the trip to Rome took place during the Italian wars and passed through war-prone areas.

According to Hans Schneider's reconstruction, which is now increasingly regarded as secure, the trip to Rome did not take place until a year later, after Luther had already moved from Erfurt to Wittenberg and was under the influence of the vicar general and provincial of the Saxon Augustinian hermits, his mentor Staupitz. He came into the possession of the office of provincial through the election of the Münnerstadt chapter on September 9, 1509. In this "double function" he was now able to set about realizing a Union plan. After all, the reason for the trip was the dispute over his plan for union, which still could not be implemented against the resistance of the rebellious monasteries. According to Schneider, the reason for the resistance of the seven unruly monasteries (see above) was the exercise of the offices of vicar general and provincial in personal union. In addition, Schneider suspects that Luther was not recalled from Wittenberg to Erfurt in 1509 because of a personnel shortage, but rather as a reaction to Staupitz's election as provincial superior. This interpretation is supported by the observation that the likewise unruly monastery in Nuremberg did not send any more monks to study in Wittenberg for the entire duration of the union dispute. In this situation of an order dispute, Staupitz looked for alternative solutions that had to be coordinated with the order leadership. Luther therefore traveled to Rome not as an opponent, but as an envoy of the vicar general, with whom he had a close personal friendship.

Travel companion

The prior Jan van Mechelen from Osbach ( Orsbeck ) and prior in Enkhuizen , who shortly before had received his doctorate theologiae in 1511 in Wittenberg, is accepted as Luther's travel companion, who led the discussions in Rome significantly . This hypothesis is supported by the statement of a contemporary, the Nuremberg Augustinian hermit Nikolaus Besler. He reported that on February 25, 1512, the Augustinian Johann von Mecheln, who “had just returned from a mission to Rome, was sent by Staupitz from Salzburg to Cologne in order to accelerate the chapter to be held there”.

Another hypothesis assumes the rain Johannes Nathin († 1529), Luther's early teacher , as a travel companion . For example, a later opponent of Luther's Hieronymus Dungersheim mentioned in his "Dadelung des obgesatzten bekentnus or unworthy Lutheran Testament" (Leipzig 1530) that he had traveled to Halle with Nathin to mediate the provost of Magdeburg's Archbishop Ernst II of Saxony in the To obtain the matter.

Under these conditions, the earliest possible departure date would be October 5, 1511. On their return to Germany, the Fathers traveled separately, with Luther possibly crossing the Rhône region in southern France to avoid the war situation around Bologna , which had now escalated . In May 1512 the Chapter of the Order took place in Cologne, where the compromise between the parties to the dispute, which had apparently been agreed in Rome, was decided and implemented. Luther's presence at this gathering, which has been documented by sources but has been difficult to explain up to now, is much better understandable if one assumes his participation in a recent trip to Rome in 1511/12.

Even Anton Kress , a Nuremberg patrician as John Cochlaeus wrote to come into question.

"Older" hypothesis for the travel year 1510/1511 and accompaniment

If one proceeds from the older hypothesis regarding the dating of the travel year 1510/1511, Luther and his travel companion would have been sent to the Roman Curia as one of the opponents to his superior Johann von Staupitz. Then Luther would have set out from Erfurt and his companion might have been Johann Nathin . For an outward journey in the autumn, i.e. October / November 1510, it would be mentioned that the consumption of pomegranates ( harvesting the pomegranate ) helped him and his travel companion with a fever attack. This argument becomes less important when you consider that harvested pomegranates can be stored or kept at 0–5 ° C for several months. The fruits can become a bit dehydrated, but they stay juicy inside. The companion according to the older hypothesis could have been the Augustinian Regens Johannes Nathin († 1529), a former teacher of Luther.

"Newer" hypothesis for the travel year 1511/1512 and accompaniment

Von Staupitz was appointed Vicar General of the German Observant Congregation of the Augustinian Order in Eschwege on May 7, 1503 , an office which he held until August 29, 1520. In the order the “observants” had separated from the “conventuals”. The observants accused the conventuals of not keeping the rules of Augustine , the rules of the order , strictly enough, and in particular violating the law of poverty . Although von Staupitz headed the stricter religious faction, he sought to overcome the division in order to enable the competing religious factions to unite. For this purpose he took over the leadership of the Saxon-Thuringian religious congregation, which stood for the moderate way.

Under the more recent hypothesis dated 1511/1512 Luther would not have set out from Erfurt, but from Wittenberg. Based on the more recent dating, he would not have traveled to Rome against von Staupitz, but on behalf of the Vicar General of the German Augustinian Reform Congregation von Staupitz to obtain further instructions from the Prior General Aegidius de Viterbo in the “Staupitz dispute” about the planned union the Reform Congregation and the Saxon Order Province.

In this case there is a lot to be said for Johan van Mechelen , Johannem Mechliniam the prior of Enkhuizen as his companion. The background to the different reconstruction is briefly outlined in the section on the prehistory below; then the route will be reconstructed based on the older assumptions including the adventurous alpine crossing.

Some of Luther's more recent biographers have adopted the new reconstruction and expressly appreciated it, but in some cases they also stick to older representations without discussing the dating problem.

Itinerary

Luther did not write any travel records. There are in later records, in particular the transcripts of his dinner speeches held in the 1530s and 1540s, several partly explicit remarks by Luther about his trip to Rome as well as reports on personal memories, some of which certainly go back to the trip to Rome or for which such a connection is obvious and in many cases it can only be assumed with some certainty.

In the present case, the travel route is reconstructed using the map of the Rome route drawn up by the cartographer Erhard Etzlaub for the Holy Year 1500 . The trade route map, which shows the common routes between Bavaria and Italy around 1500, is also used. For the last section from Siena to Rome, the information about the Via Francigena is used for comparison . Luther's later references are hereby synchronized.

The trade route from Nuremberg to Italy had a western branch via Switzerland and an eastern branch via the Brenner. The hikers' way there went west via Switzerland and Milan (mentioned by Luther as a travel stop). At the beginning of the trip, Luther noticed that the old Roman (1.482 km) and not the German (7.500 km) mile was valid in Switzerland and further in Italy . The way back could have led via Innsbruck and Augsburg; the only station that Luther safely passed on his way back is Augsburg.

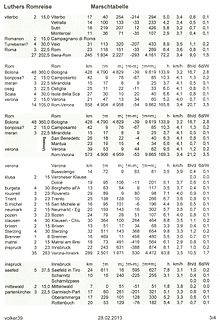

The locations of the Romweg map are recorded with their current names in the marching table .

Away

Approach Erfurt - Nuremberg

The Romweg map shows the topographically best route. From Erfurt in the valley of the Gera the path goes up the Wilde Gera to Arnstadt and on to Ilmenau in the valley of the Ilm on the northern edge of the Thuringian Forest . He crosses this at an altitude of 770 m, then goes down to Eisfeld and Coburg in the valley of the Itz . Down the Itztal, the route briefly touches the Main and leads to Bamberg in the Regnitz valley . Up the Regnitz valley follow Forchheim , Erlangen and finally Nuremberg at the confluence of the Pegnitz and Rednitz rivers to the Regnitz. Luther's presence in Nuremberg is confirmed by his mention of the striking mechanism of a clock.

Nuremberg - Lindau on Lake Constance

Luther later mentioned Ulm in conversation, so he must have been there. The Romwegkarte does not show any connection from Nuremberg to Ulm . The trade route map shows a schematic route and names Nördlingen . From this, the route via Gunzenhausen , Nördlingen and Heidenheim an der Brenz was deduced as the probable route .

According to the route sketch, the route goes from Nuremberg first to Schwabach to the fork in the road to Augsburg or Ulm and then leads via Hergersbach , Gunzenhausen and Oettingen in Bavaria to Nördlingen. The path then leads south directly to the characteristic Danube arch near Dillingen. He always remains in Bavaria east of the border with Baden-Württemberg. Heidenheim an der Brenz was probably not passed. The route leads from Nördlingen via Hohenaltheim , Thalheim and the Unterliezheim Abbey to Dillingen an der Donau . Then it goes up the Danube via Lauingen and Günzburg to Ulm. This route is 2-3 hours longer than via Heidenheim.

The Romweg map shows the route to Ulm via Biberach an der Riss and Ravensburg to Lindau (Lake Constance) .

A presumed route from Ulm via Memmingen and Kempten to Lindau is not shown on either map. The route via Kempten is a considerable detour of nine leagues. From Memmingen there is a sensible route, only two hours longer, via Leutkirch and Wangen to Lindau.

Alpine Rhine Valley Lindau - Chur

From Lindau the route follows the Alpine Rhine Valley via Bregenz and Feldkirch to Balzers . The territory of the Swiss Confederation began behind Balzers . The trade route map shows the topographically given route further over the St. Luzisteig (713 m), Maienfeld and Zizers to Chur .

Alpine crossing Chur - Chiavenna

From Chur there are two cross-alpine pass routes to Chiavenna (German: Cleff or Cleven): the Obere Straße over the Septimerpass and the Untere Straße over the Splügenpass . The Romweg map only shows Chur and Chiavenna, but does not provide any topographical information on the pass route. The trade route map shows the Splügen route, which was expanded and made mobile in 1473.

Septimer route

The emissaries probably followed the Septimer route, which was preferred at the time. Were passed Tiefencastel (859 m), Tinzen (now Tinizong-Rona), Mulegns (to 1943 mills), Bivio (1,769 m) and over the Septimerpass (2,310 m) we went to Casaccia (1,458 m) in the Bergell . Then it went down the Mera to Castasegna , the border town to Italian Lombardy . Luther often talked about Switzerland but did not report any place names. He praised the Swiss for their friendliness and hard work. In the lower Bergell Valley, hikers passed Piuro and Scilano , which were buried in a landslide in 1618, and came to Chiavenna (333 m). This is where the Splügen route arrives.

Splügen route

According to the trade route map, the route goes from Chur to Bonaduz at the confluence of the Vorderrhein and Hinterrhein rivers . It then follows the Hinterrheintal to Thusis and then over the dreaded Viamala through its narrowest point to Zillis and Andeer to Splügen (1,475 m). There the route branches off to the Splügen Pass or San Bernardino Pass. The path goes up through the valley of the Hüscherenbach to the Splügenpass (2,113 m) on the Italian border and then through the Val San Giacomo with the river Liro via Campodolcino to Chiavenna (333 m). This route is about six leagues, almost a day shorter than via the Septimer.

Lombardy Chiavenna - Bologna

Then the path leads south on both maps through the valley of the Mera coming from the Bergell to Gera Lario at the northern tip of Lake Como . The route leads along the west bank via Gravedona and Cadenabbia to Como . A monastery connected with the German observants offered you accommodation here. It went through the southern foothills of the Alps via Seveso to Milan, which Luther mentions as a travel stop. Because of the Ambrosian rite, he was not allowed to read mass there. There were two observant monasteries here that provided accommodation. Following the map of the Rome route, the route continued via Pavia , the Ticino and Po downhill through the Lombardy plain to Piacenza . There was an Augustinian monastery here. This was followed Brescello and San Giovanni in Persiceto and finally Bologna was reached. Here is the access to the trails across the Apennines.

In Bologna, the hikers found quarters in a friendly Augustinian monastery and were given advice on the difficult conquest of the rugged mountains. At that time, Pope Julius II was in Bologna. Contact with papal authorities was forbidden. The delegates must have tried to see the Pope at public masses. Luther thoroughly inspected the church treasures of Bologna.

Apennines Bologna - Siena

The route across the Apennines , particularly arduous in winter , went straight to the south according to the Rome route map. The places Pianoro , Loiano , Monghidoro (formerly Scaricalasino), Pietramala, Firenzuola , Scarperia and finally Florence , which Luther mentions as a travel stop, are listed. He praises the Ospedale degli Innocenti .

On this route the Passo del Giogo (882 m) was passed between Firenzuola and Scarperia . The trade route map shows the route over the Passo della Futa (903 m). After Pietramala the paths separate and come together again at San Piero a Sieve.

In Florence there was an Augustinian monastery in the north where the hikers lodged. Luther fell ill on the way across the Apennines and turned to the Santa Annunziata Hospital . In a dinner speech, he later praised this as an excellent facility. The envoys left Florence on the south gate and came through San Casciano in Val di Pesa and Poggibonsi to Siena .

Siena - Rome

After Siena we went on the ancient Via Cassia through the Campagna Romana via Buonconvento , San Quirico d'Orcia to Radicofani . This place is a bit off the Via Cassia but on the Via Francigena. The incessant stream of pilgrims and the nearby monastery of San Salvatore di Monte Amiata made the place important. In the Romwegkarte is pallio specify what probably referring to the nearby river Paglia relates. The route then goes via Acquapendente , Bolsena (Via Francigena) and Montefiascone to Viterbo .

Then the map of the Rom way next shows Romanon , that is Campagnano di Roma near the Via Cassia. The following location information Turrebarran? can point to the tumuli , especially the Tomba del Anatre near the city of Veji , which was destroyed in the 5th century and is now the Veio necropolis .

Following the Via Francigena, the main route goes from Viterbo via Vetralla , Sutri , Monterosi , Campagnano di Roma and La Storta , near Veio, to Rome. A secondary route goes via Caprarola , Ronciglione and Nepi to Monterosi and is three to four hours longer than the main route.

Rome

The emissaries reached Rome shortly after Christmas on December 25, 1510 or in January 1511. According to the Christian calendar of that time , Christmas was the beginning of the year 1511.

Shortly before Rome, the Via Cassia meets the Via Flaminia , on which the hikers reached the Piazza del Popolo via the Milvian Bridge (Ponte Milvio) and through the Porta Flaminia (Porta del Popolo) . Visitors have entered the city in this famous square since ancient times. A legend has come down to us:

"At the first sight of Rome, Luther threw himself to the ground with the words: 'Greetings, you holy Rome, truly holy of the holy martyrs, whose blood it is oozing.'"

After outdated reconstructions of the 20th century (e.g. Böhmer) it was Luther's task in Rome to represent the point of view of the observants before the order general Aegidius de Viterbo . For this purpose Luther lived in the monastery of the Basilica di Sant 'Agostino in Campo Marzio , which at the time was also the official seat of the order general. An apartment in the monastery of Santa Maria del Popolo , as Heinrich Böhmer suspected, would have reduced the chances of negotiation from the outset, since the monastery belonged to the recalcitrant Lombard congregation and the general of the order considered all the resistance to be rebels anyway: “Disobedience could easily lead to the religious dungeon , especially in Rome. "

Within the prescribed two days, the order given by the Nuremberg Conference was submitted to the order procurator Ioannes Antonius de Chieti to allow an appeal to the Pope on the question of the religious dispute.

Luther underwent some acts in Rome that were part of the piety of achievement at the time: sober pilgrimage through the seven pilgrimage churches of Rome , fasting, reading masses and finally also penance exercises: he crawled up the so-called holy staircase at the Lateran Palace on his knees and prayed on every step a Lord's Prayer for his grandfather Heine Luder.

On January 20, 1511, Luther took part in such a great pilgrimage within Rome. A few days later, the delegates were informed of the General's decision. Certainly the embassy had already been doomed to failure: Aegidius de Viterbo was an advocate of the religious policy of the German vicar general Johann von Staupitz ( see above ) .

As expected, the appellation to the Pope was not allowed: 1511 January To appeal to the Germans is prohibited by law. In order that German affairs would be brought back to love and perfect obedience, Brother Johannes the German was sent to the Vicar. As was customary at the time, Brother Johannes was sent to the Vicar General Staupitz to ensure secure communication. Soon after, in late January or early February 1511, the emissaries set off for home. It is not known whether the three people traveled together.

Schneider puts the purpose of the trip to Rome in a different context: after the recalcitrant convents appealed to the Pope for the third time on September 10, 1511 and were excommunicated on October 1, 1511, the question arose how it was now Union policy) should continue. According to this, Luther traveled to Rome to get the answer to this question from the order general.

The impressions he gained in Rome must have accompanied him throughout his life. And with regard to the Reformation , Thomas Kaufmann wrote :

“It cannot be overlooked that some of what he had seen in the Eternal City (...) made it easier for him to receive anti-Roman polemics. In this respect, Luther's trip to Rome does not represent a source of the break with the papal church, but a prerequisite for subsequently giving the break that occurred later a special plausibility and popularity. "

Luther stated that the length of stay in Rome was four weeks.

way back

Military situation near Bologna

To restrict the power of Venice , the League of Cambrai was formed on December 10, 1508 . The subsequent Great Venetians war should Venice permanently weaken selling French and their allied troops from Italy and the Papal States expand. This goal was only partially achieved. Venice was pushed back, but France expanded its sphere of influence considerably. On February 24, 1510 the alliance ended. After that, French and papal troops faced each other in Romagna without fighting. This location was uncomfortable for residents and unsafe for travelers, but not unusual for the time. Bologna was the papal headquarters until January 2, 1511. Then the Pope moved to Mirandola, came on 6/7. February back to Bologna and on February 11, 1511 went to Ravenna for several months.

Between Luther's outward journey in December 1510 and his return journey in February 1511, the risk situation at Bologna had not deteriorated noticeably. It is assumed here that Bologna was passed by both emissaries on the outward and return journey.

If the trip to Rome took place in 1511/12, the emissaries would have ended up in a virulent war zone on the outward and return journey near Bologna.

To expel the too powerful French from Italy, the Holy League was formed on October 1, 1511 . The Pope had since recruited considerable mercenary troops. In November 1511 a federal army of 20,000 men had moved to Italy and threatened Milan. In December 1511, Julius II began arming his army in order to u. a. Recapturing Bologna. On April 11, 1512, the French won the battle of Ravenna over the papal army and its allies. Under these circumstances it is difficult to imagine that the envoys passed via Milan and Bologna on the outward journey.

In order to avoid the war zone extensively on his return journey in 1512, a route through southern France is suggested for Luther. From Rome first following the Via Francigena to Siena and Lucca. Then along the coastal road to Genoa, Nice and Aix-en-Provence. Then up the Rhone valley to Lyon, Geneva and through Switzerland via Friborg to Zurich. Augsburg, which Luther passed on the return journey, is then reached via Memmingen. On this route, San Benedetto Po is not passed, although this is said to be probably visited by Luther . It is also assumed that the emissaries have separated. The older brother is said to have moved from Rome via Rimini, Venice by ship, Villach to Salzburg. This would have violated the order's rule of always marching in pairs, one behind the other and in silence. This could supposedly have been cured by hikers on loan in stages.

These interesting suggestions are not examined further here.

Rome - Verona

The journey home initially took the envoys back to Bologna via Florence on the same route.

According to the Romwegkarte, the route leads from Bologna via Camposanto , Mirandola , Ostiglia and Isola della Scala to Verona . Probably the 3–4 hours longer route via San Benedetto Po and Mantua to Verona was taken. There was a conventual Augustinian monastery there.

Brenner route Verona - Innsbruck

After Verona, the route of the Romwegkarte leads through the Veronese Klause and the Adige valley up to the Alps. Via Borghetto all'Adige , Rovereto Trient , San Michele all'Adige (Sankt Michel) and Neumarkt the route goes to Bozen . In the Eisack valley , you take the Kuntersweg to Klausen and from there upwards via Brixen , Sterzing to the Brenner Pass (1,370 m). Then it goes down in the valley of the Sill via Matrei am Brenner to Innsbruck , about whose architecture Luther later made a comment.

Innsbruck - Nuremberg

After Innsbruck, the Romweg map shows the way via Seefeld in Tirol (1,180 m) through the Scharnitz Pass (955 m) to Mittenwald and Partenkirchen in the Loisach valley . The next named place Schongau lies on the Lech . The route into the Lech Valley goes near Oberau over the Ettaler Sattel (869 m) to Ettal , Oberammergau an der Ammer and Rottenbuch to Schongau. The following village, romakessel , has been a rest stop in Seestall that still exists since the Middle Ages . Then comes Landsberg am Lech . The barn , today preserved in the name of Schwabstadl , probably means the nearby village of Lagerlechfeld on the ancient Via Claudia Augusta . Finally, they reach Augsburg , which Luther later told us about. There he is said to have met the alleged starvation martyr, Anna Laminit . The route leaves the Lech and goes over the Danube at Donauwörth and on to Monheim , crosses the Altmühl at Dietfurt an der Altmühl and then leads via Weißenburg in Bavaria and Roth to Nuremberg.

There the delegates had to report to the convent of the Augustinian monastery and the city council about the rejected appellation. Luther soon returned to Erfurt and arrived there again in April 1511.

Conditions of the trip

The trip took place in the winter months with rather short days. The hours of day are the length of the day (time between sunrise and sunset) plus civil twilight of around 40 minutes in the morning and evening. In hours this was approximately: from Nuremberg 10.5; Septimer / Splügen 9.5-10.0; Rome 10.5; Bozen / Brenner 11.5; to Nuremberg 12.5. The hiking stages had to be divided in such a way that a quarter could be found.

The winter weather conditions made the trip difficult even in "Germany". The Alps were crossed on the way there in deep winter. There was snow on all the pass routes. Crossing the Septimer was exhausting and especially dangerous in winter. Local mountain guides must have shown the right way. From Tiefencastel at 859 m, the path climbs to the Septimerpass at 2,310 m. The difference in altitude is 1,451 m, the total altitude difference (↑ m ascent plus m ↓ descent) is 3,693 m. The crossing was a special sporting achievement. Crossing the Splügen Pass would also have been no less sporty. From Thusis at 720 m, it goes up 1,393 m to the Splügenpass at 2,113 m, with 2,922 meters of altitude to be achieved. On the way back, the Brenner Pass and the Zirler Berg were crossed in the snow despite the beginning of winter.

The winter in Italy in 1510/11 was unusually harsh. It rained incessantly in Rome from late October 1510 to early February 1511. There was deep snow in Bologna on January 2, 1511, on the 6th there was a heavy snowstorm and on the 15th there was a blizzard. In addition, it was unbearably cold.

The rule of Augustine also had to be observed during the journey. This included observance of Lent , which is important for the hikers . On November 11th, the 40-day fast began in the Advent season before Christmas. The emissaries had to fast until Rome. The Easter fasting period is also 40 days and starts between February 9th and March 16th. It is therefore possible that part of this fasting period also had to be observed during the hike. Exercise and fasting are a challenge for everyone. It would have to be clarified whether Sunday was a day of rest without hiking . Here it is assumed that there are six days of walking and one day of rest per week.

While crossing the Lombard plain, the hikers developed a severe febrile illness from which they recovered with difficulty. They could only walk a mile in a day. In Florence, Luther was admitted to a hospital because of illness .

The delegates must have stayed longer than one night in special places, especially in Milan and Bologna .

Marching performance

The march table shows the travel locations with historical and current names, as well as distances, ascents and descents, hours of travel , march speed and march duration.

A route planning program was used for the creation. From the suggested routes, the most appropriate variant for the terrain and settlement was selected. Hiking trails across country or across mountain ranges were not selected. Most of the time they corresponded to road connections that had not grown. From the selected variant, km distance, ↑ m ascent and m ↓ descent were taken over.

To determine the hiking times, the hiking time calculation customary in Switzerland was used. The simple method calculates the walking time as follows: hours = 4.2 km / hour. + 300 (↑ m + m ↓) / hour The detailed method, hour = 4.0 km / hour. + 300 ↑ m / h + 600 m ↓ / h, only differs by 7–9% for pronounced mountain stretches. For the total trip, the results of both methods are practically the same with a difference of one per thousand.

| stage | Way km | Heights ↑ m + m ↓ | Way h | km / h | Days 8 h | Weeks 6 days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuremberg - Lindau on Lake Constance | 299 | 2,038 | 78 | 3.8 | 10 | 2 |

| Lindau - Chur | 98 | 874 | 26th | 3.7 | 3 | |

| Chur - Septimer - Chiavenna | 96 | 5,533 | 41 | 2.3 | 5 | 1 |

| Chiavenna - Bologna | 399 | 1.941 | 102 | 3.9 | 13 | 2 |

| Bologna - Siena | 183 | 5,458 | 62 | 3.0 | 8th | 1 |

| Siena - Rome | 245 | 4.161 | 72 | 3.4 | 9 | 1-2 |

| Away | 1,320 | 20.005 | 381 | 3.5 | 48 | 8th |

| Rome - Verona | 558 | 9,862 | 166 | 3.4 | 21st | 3-4 |

| Verona - Innsbruck | 289 | 4,472 | 84 | 3.5 | 11 | 2 |

| Innsbruck - Nuremberg | 321 | 3.223 | 87 | 3.7 | 11 | 2 |

| way back | 1,169 | 17,557 | 337 | 3.5 | 42 | 7th |

| Nuremberg - Rome - Nuremberg | 2,489 | 37,562 | 718 | 3.5 | 90 | 15th |

| Erfurt - Nuremberg - Erfurt | 424 | 4,982 | 117 | 3.6 | 15th | 2-3 |

| Erfurt - Rome - Erfurt | 2,912 | 42,544 | 835 | 3.5 | 104 | 17-18 |

The average daily mileage is 28 km. This agrees well with understandable information in the literature. Other figures of 40 km / day cannot be explained plausibly. Daily mileages over 30 km are forced military marches with high personnel wear and tear.

Summary

For the outward journey, taking into account the calculated eight hiking weeks, the weather conditions, the illnesses and the visits for the purpose of viewing, at least two months are to be assumed. The envoys must have left Nuremberg in October / November 1510 to arrive in Rome at the end of December. This is a remarkable sporting achievement that was motivated by a great spiritual goal.

The return journey was started after Böhmer's reconstruction in January / February 1511 and should have lasted almost two months with seven calculated hiking weeks with visits to San Benedetto and Innsbruck, among others . Nuremberg was probably reached again at the end of March 1511. This remarkable sporting achievement is also to be explained by the obligation to report to the convention as soon as possible in accordance with the instructions.

After the reporting, Luther returned to Erfurt in mid-April 1511, which he had left in mid-October 1510.

literature

- Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. U. Deichert'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung Werner Scholl, Leipzig 1914

- HH Borcherdt, Georg Merz (Ed.): Martin Luther, Selected Works, Table Speeches. Chr. Kaiser Verlag, Munich 1963

- Hans Schneider: Luther's trip to Rome. In: Martin Luther in Rome. The Eternal City as a cosmopolitan center and its perception. (Library of the German Historical Institute in Rome 134), edited by Michael Matheus, Arnold Nesselrath, Martin Wallraff, Berlin / Boston 2017; Pp. 3-31, ISBN 978-3110309065 .

- Hans Schneider: Martin Luther's trip to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. Studies on the history of science and religion, Volume 10, pp. 1–157, Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, De Gruyter, Berlin / New York, 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-025175-3 , e- ISBN 978-3- 11-025372-6 , ISSN 0930-4304

- Herbert Voßberg: In Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, license 420. 205-293-66. ES2C. H2678. III-15-6. ed

- Reinhard Zweidler: The Franconian Way - Via Francigena, The medieval pilgrimage route from Canterbury to Rome. Knowledge Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-534-16282-X

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michael Matheus, Arnold Nesselrath, Martin Wallraff: Martin Luther in Rome: The Eternal City as a cosmopolitan center and its perception. Vol. 134 Library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-1103-0906-5 , p. 11

- ^ Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914.

- ^ Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. S. 7th f .

- ^ Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. S. 23 .

- ^ Hans Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. In: Werner Lehfeldt (Hrsg.): Studies on the history of science and religion (= treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. New series, volume 10). De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-025175-3 , pp. 1–157.

- ^ Hans Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. Presented by Hans Schneider at the meeting on July 17, 2009 PDF

- ↑ Martin Luther in Rome. Cosmopolitan center and its perception. International conference organized by the German Historical Institute in cooperation with the Centro Filippo Melantone. Protestant Center for Ecumenical Studies Rome. 16. – 20. February 2011, German Historical Institute in Rome, conference report by Christina Mayer [1]

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, pp. 7–9

- ^ Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914, p. 36

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 10

- ^ Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914, p. 52

- ^ Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914, pp. 161–166

- ^ Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914, p. 56

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, pp. 10–11

- ^ Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914, p. 58

- ^ Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. S. 31 .

- ^ Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. S. 60 .

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 12; Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914, p. 79

- ^ Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. S. 49 .

- ^ Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. , P. 49: "It soon became clear - and Staupitz soon felt it - that the Münnerstadt election had been a serious tactical mistake, against which resistance from the ranks of the congregation and interested authorities arose."

- ^ Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. S. 50 .

- ^ Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. S. 51 .

- ^ Hans Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. In: Werner Lehfeldt (ed.): Studies on the history of science and religion. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-025175-3 , pp. 45 f., Accessed on April 10, 2018 [2]

- ^ Ulrich Köpf: Martin Luther. The reformer and his work. Reclam, Stuttgart 2015, p. 30.

- ↑ Christopher Spehr: Luther yearbook 82nd year 2015: Organ of international Luther research. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-6478-7447-0 , p. 14

- ^ Hans Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. Presented by Hans Schneider at the meeting on July 17, 2009, accessed on December 30, 2018 [3] , p. 16

- ↑ Lyndal Roper: The man Martin Luther - The biography. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2016, ISBN 978-3-10-066088-6 , pp. 90-92.

- ^ Hans Schneider: Martin Luther's journey to Rome. In: Studies on the history of science and religion. Vol. 10, Academy of Sciences, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2011, pp. 1–157

- ↑ Michael Matheus, A. Nesselrath, Martin Wallraff: Martin Luther in Rome: Cosmopolitan Center and His Perception. Library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2015, ISBN 3-1103-1611-0 , p. 9

- ↑ WATR 4, No. 4104 (Latin) p.136; No. 1327 (German) pp. 48-50

- ↑ Michael Matheus, Arnold Nesselrath, Martin Wallraff: Martin Luther in Rome: The Eternal City as a cosmopolitan center and its perception. Vol. 134 Library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-1103-0906-5 , p. 11

- ↑ Lyndal Roper: The man Martin Luther - The biography. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2016, ISBN 978-3-10-066088-6 , pp. 90-92.

- ↑ Volker Leppin : The foreign Reformation. Luther's mystical roots. CH Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-69081-5 , p. 12

- ^ Otto Clemen : The Augustinian monastery in Antwerp at the beginning of the Reformation (1513-1523). Monthly notebooks of the Comenius Society. Edited by Ludwig Keller, Volume 10, Issue 9 and 10, November-December 1901, Berlin 1901, R. Gaertners Verlagbuchhandlung Hermann Heyfelder, p. 307 [4]

- ^ Conference report by Christina Mayer: Martin Luther in Rome. Cosmopolitan center and its perception. International conference organized by the German Historical Institute in cooperation with the Centro Filippo Melantone. Protestant Center for Ecumenical Studies Rome. 16. – 20. February 2011, German Historical Institute in Rome [5]

- ^ So Thomas Kaufmann ( Martin Luther. 2nd, reviewed edition, Beck, Munich 2010, p. 36 f.), Bernd Moeller ( Luther and the papacy. In: Albrecht Beutel (Ed.): Luther Handbuch. 2nd edition , Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2010, p. 107), Volker Leppin ( Martin Luther: from the monk to the enemy of the Pope. WBG , Darmstadt 2013, p. 24 for note 42) and most recently Ulrich Köpf ( Martin Luther. Der Reformer und sein Werk. Reclam, Stuttgart 2015, pp. 30–34), who describes the new dating of the trip to Rome as “the most important contribution to biographical Luther research from recent years” (ibid. P. 247).

- ↑ So Heinz Schilling ( Martin Luther: Rebell in a Zeit des Umuchs. Munich 2013, p. 100 ff.) And Volker Reinhardt ( Luther der Ketzer. Rom und die Reformation. Munich 2016, p. 30).

- ↑ high spring attributed by Herbert Voßberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 14

- ↑ a b c d e f Trade route map (PDF; 1.2 MB)

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 13; Schneider: Martin Luther's trip to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. , Pp. 120-121

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, pp. 13-14; Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914, p. 77: Schneider: Martin Luther's journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. , Pp. 121-125

- ↑ a b c Martin Brecht: Martin Luther. His path to the Reformation 1483–1521 . 2nd Edition. tape 1 . Calwer Verlag, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 978-3-7668-0678-9 , pp. 105 .

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 16

- ^ Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. P. 78

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, pp. 17–21

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 21

- ^ Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. , P. 121

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 24

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, pp. 26–27

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, pp. 28–29

- ↑ http://www.italytravelescape.com/italienischen-stadten/standort/karte-toskana/florenz/pietramala.html

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 30; Schneider: Martin Luther's trip to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. , P. 121

- ↑ Günter Scholz: "Didn't I cause enough commotion?": Martin Luther in personal testimonies. CHBeck, Munich 2016

- ↑ but possibly also the Ospedale di Santa Maria Nuovi

- ↑ HH Borcherdt, Georg Merz (ed.): Martin Luther, Selected Works, Table Speeches. Chr. Kaiser Verlag, Munich 1963, p. 23

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 36

- ^ Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914, p. 79

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 37

- ^ Heinrich Böhmer: The young Luther . Gotha 1925, p. 71 .

- ↑ Schilling: Martin Luther: Rebel in a time of upheaval. O . S. 104 f .

- ↑ Schilling: Martin Luther: Rebel in a time of upheaval. S. 105 .

- ^ Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. , 67 297

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 43

- ↑ Schilling: Martin Luther: Rebel in a time of upheaval. S. 107 .

- ↑ Schilling: Martin Luther: Rebel in a time of upheaval. S. 107 .

- ↑ Martin Brecht: Martin Luther. His path to the Reformation 1483–1521 . 2nd Edition. tape 1 . Calwer Verlag, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 978-3-7668-0678-9 , pp. 106 .

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, pp. 112–113: MDXI.Jan.Appellare ex legibus germani prohibentur. Ut res Germanae ad amorem et integram oboedientiam redigerentur, Fr. Johannes Germanus ad Vicarium missus est ; Schneider: Martin Luther's trip to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. , P. 66: the date MDXI.Jan is missing here .

- ^ Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. S. 115 f .

- ↑ Schilling: Martin Luther: Rebel in a time of upheaval. S. 109 .

- ↑ Thomas Kaufmann: History of the Reformation . Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2009, p. 138 f .

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 112; Schneider: Martin Luther's trip to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. , P. 115

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 114; Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome, Deichert. Leipzig 1914, p. 79

- ^ Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. P. 122

- ^ Schneider: Martin Luther's Journey to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. Pp. 119-127

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 114; Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914, p. 82; Schneider: Martin Luther's trip to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. P. 121

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 116; Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914, p. 78; Schneider: Martin Luther's trip to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. P. 121

- ↑ http://www.roemerkessel.com/

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 34; Schneider: Martin Luther's trip to Rome - newly dated and reinterpreted. P. 121

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 119

- ↑ HH Borcherdt, Georg Merz (ed.): Martin Luther, Selected Works, Table Speeches. Chr. Kaiser Verlag, Munich 1963, p. 288

- ^ Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914, pp. 79/80

- ^ Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914, p. 80

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 23

- ↑ http://www.komoot.de/plan/

- ↑ The route km from Siena to Rome could not be brought into agreement with the information in the Via Francigena route table

- ↑ http://www.alternatives-wandern.ch/reports/wanderzeit.htm

- ^ Herbert Vossberg: In the Holy Rome, Luther's travel impressions 1510-1511. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1966, p. 15: 4 miles = 30 km / day; Heinrich Böhmer: Luther's trip to Rome. Deichert, Leipzig 1914, p. 79: less than 32 km / day