Vegetable asparagus

| Vegetable asparagus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Asparagus officinalis |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Asparagus officinalis | ||||||||||||

| L. |

Vegetable asparagus or common asparagus ( Asparagus officinalis ) is one of approx. 220 species from the genus Asparagus ( Asparagus ). Colloquially it is usually called asparagus for short (via Middle Latin sparagus and Latin asparagus from Greek aspáragos ). The young shoots are eaten ( Greek or Attic asp (h) áragos , "young shoot", from spargáein , "burst, be swollen, sprout with young shoot").

The home of the vegetable asparagus are the warm and temperate regions of southern and central Europe , North Africa and the Middle East , especially on river banks. It is cultivated as a vegetable in several cultivars .

description

The asparagus is a deciduous, perennial, herbaceous plant . From the rhizome it sprouts fleshy, juicy, whitish or pale reddish sprouts covered with spirals with lower leaves , which extend above the ground in a branched, green, 0.6 to 1.5 meter high, smooth stem . The leaf-like branches are needle-shaped, smooth.

The flowering period extends from June to July. The flowers are rarely hermaphroditic or mostly unisexual. If the flowers are unisexual, then the vegetable asparagus is dioeciously segregated ( diocesan ). The relatively small, hermaphrodite flowers are threefold. The six bracts are yellowish and up to 6.5 millimeters long.

The berries are scarlet and slightly poisonous.

The number of chromosomes is 2n = 20.

Occurrence

Forerunners or relatives of today's vegetable asparagus occur wild in Central and Southern Europe , Western Asia, western Siberia and North Africa . The eastern Mediterranean is believed to be the home of asparagus . In South and North America as well as in New Zealand it occurs in places naturalized. It is unclear whether the stocks on gravel and sandbanks of the Rhine, Main and Danube, already mentioned by medieval authors, are real wild occurrences or go back to naturalization. Feral asparagus can be found in Central Europe on dry, moderately nutrient-rich locations, on dams, along roadsides, in dunes and in ( ruderal ) dry grasslands . It usually thrives in societies of the order Corynephoretalia , but also the order Origanetalia or the class Festuco-Brometea .

Economical meaning

The greatest producers

In 2018, according to the food and agriculture organization FAO, 9,108,203 t of asparagus were harvested worldwide.

The following table gives an overview of the 10 largest producers of asparagus worldwide, who produced a total of 98.6% of the harvest.

| rank | country | Quantity (in t ) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

7,982,230 |

| 2 |

|

360.630 |

| 3 |

|

277,682 |

| 4th |

|

133.020 |

| 5 |

|

68,403 |

| 6th |

|

49,000 |

| 7th |

|

35,460 |

| 8th |

|

26,937 |

| 9 |

|

23,779 |

| 10 |

|

20,957 |

trade

In 2017, 401,132 t of asparagus were exported worldwide. The largest exporters were Mexico (160,939 t), Peru (115,427 t) and the USA (39,645 t).

Germany imported 25,140 tons that year and exported 5,120 tons of asparagus in the same period.

Market supply in Germany

| year | harvest | Imports | total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 98.193 | 22,591 | 120,784 |

| 2010 | 92,404 | 24,437 | 116,841 |

| 2011 | 103.457 | 24,925 | 128,382 |

| 2012 | 102.395 | 26,409 | 128,804 |

| 2013 | 103.107 | 23,696 | 126,803 |

| 2014 | 114.090 | 26,062 | 140.152 |

| 2015 | 113,613 | 23,578 | 137.191 |

| 2016 | 120.014 | 24,484 | 144,498 |

| 2017 | 130,881 | 25,140 | 156.021 |

| 2018 | 133.020 |

use

A distinction is made between white (or pale) and green asparagus. In the former, the shoot axes are harvested before they reach the surface of the earth. The asparagus shoots are harvested in Europe from March to June, depending on the region, and are particularly valued as a vegetable . In Germany nowadays, the consumption of white asparagus predominates, in English-speaking countries (as in the past also in Germany) that of green asparagus.

sorts

Although many people understand asparagus varieties only to have different colors (white, green and purple), there are also varieties of asparagus, as with other vegetables, that have different properties (the color is partly due to the different harvesting methods - white asparagus shoots are under cut off the earth, green and purple above the earth).

For centuries, asparagus was propagated by harvesting and re-sowing the seeds of the best plants. As a result of this process, regionally adapted varieties emerged over time, which may have advanced to the cultivar stage, ie that there was a certain purity of desired characteristics ( plant breeding ). It can be assumed that by the middle of the 20th century there were such local varieties for most of the larger German cultivation areas (e.g. Improved Schwetzinger, Grünköpfiger Ulmer).

At the beginning of the 20th century, individuals such as JB Norton in the USA, A. Huchel in Osterburg, J. Böttner in Frankfurt / Oder and Gustav Unselt in Schwetzingen began with the targeted breeding selection of the existing " local varieties ". Two of these varieties can still be found in Germany (almost exclusively in amateur cultivation): Ruhm von Braunschweig and Huchel's performance selection (selected from the previous one). Outside Germany you can still find the "old" varieties, which are also preferably grown as pale asparagus, Goldgendender (Austria), Argenteuil (France), Blanco de Navarra , Blanco de Aranjuez (Spain), Harvest 6 and Early Yellow (Russia, Ukraine, etc.) , the green asparagus varieties Mary Washington , Connover's Colossal (mainly Great Britain and USA), Santenese (Italy) and the purple varieties Jacq Ma Pourpre (France) and Violetto d'Albenga (Italy).

Since the 1950s, asparagus varieties have been produced using increasingly sophisticated methods. The variety "Schwetzinger Meisterschuss" as the first hybrid variety (1952) and "Lucullus" as the first purely male asparagus hybrid (1975) by the company Südwestdeutsche Saatzucht were the beginning of a rapid development that has led to exclusively such purely male hybrid varieties in Cultivation are.

Worth mentioning in this context are the two varieties Start (green) and Eros (used as green and white), which were bred in the German Democratic Republic during the same period .

In Germany, only a few companies share the task of supplying the rapidly growing market with new asparagus varieties. Limseeds from Horst , Netherlands as a leading company created so u. a. the varieties Gijnlim (now the standard variety), Grolim , Backlim , Herkolim and Thielim , the Südwestdeutsche Saatzucht in Rastatt contributed Rapsody , Ravel and Ramires , the German asparagus cultivation in Mölln participated with Mondeo and Hannibal .

This is only a small selection of the steadily growing range of more or less similar high-performance varieties , the original lines of which are technically generated by haploid breeding and which cannot be propagated by seeds.

Cultivation

Asparagus grows best in loose, sandy, not too moist soil, but can in principle be grown on any soil that does not contain too many stones and waterlogging. To plant the asparagus beds in your own garden, you dig a trench of approx. 30 cm before the onset of winter, dig under dung or other organic fertilizer on the bottom, and plant one to two-year-old asparagus plants in spring ( called claws because of their long, fleshy roots ) and cover them with earth. Cultivation from seeds is more complex and time-consuming. In autumn, the stems are cut off and disposed of in order to remove the basis for pathogens such as fungi and pests such as the asparagus fly. In spring, the trench is completely filled with earth. At the beginning of the third year, an approx. Knee-high wall is built over the planting ditch (known as Bifang in the southern German and Austrian language areas ) and then the harvest can begin.

In principle, green asparagus requires the same procedure, only no earth wall is built over the plants.

harvest

Once the asparagus shoots in the spring break through the dam, they are up to 25 cm excavated and mostly cut off at the lower end with a specially manufactured for sticking knife ( engraved ). To this day, this is still done by hand in most cases. After the “prick”, the resulting hole is filled up again and the surface is smoothed so that further shoots can be seen better.

The asparagus fields are searched twice a day (early in the morning and in the evening) for sprouting asparagus.

In order to be able to better control the harvest, the walls are now mostly covered with foils. A black outside increases the temperature in the ridges and thus accelerates growth (early harvest); the opposite is achieved with a white film on the outside. The asparagus spiders are used for harvesting under the foils , which avoid the time-consuming uncovering and covering of the foils by hand.

After pricking, the asparagus is washed, separated according to quality using an asparagus sorting machine and passed on to wholesalers or sold directly.

In order to save personnel costs or because there are no longer enough helpers available for the strenuous harvest, increasing attempts are now being made to harvest the asparagus mechanically. There have been attempts to do this in the USA since 1907 . From the 1950s to the 1990s in particular, much research has been carried out and some patents have been granted in the USA and Australia for the selective and non-selective asparagus harvest; but so far none of the methods has been able to prevail or offer a price advantage. Asparagus harvesting machines are now also available in Germany .

The non-selective harvesting method, in which all asparagus shoots are randomly cut off at a certain point in time, is controversial, on the one hand, because it does not differentiate between short and long (desired) stalks and, on the other hand, can damage the roots to such an extent that the following harvesting season leads to yield losses is to count. It is therefore preferred to work on selective mechanical harvesters.

The end of the asparagus season is described by traditional farmer rules : “Never cut the asparagus after Midsummer” or “Red cherries, dead asparagus”. Their official end in Germany is traditionally June 24th, St. John's Day . The background to this farmer's rule is the maintenance of a sufficient regeneration time for the plant for a high-yield harvest in the next year. If the asparagus season started earlier due to favorable weather conditions, the growers often prefer the end of the harvest by one to two weeks.

Growing areas in Germany

"Asparagus is the most commonly grown vegetable in the open air," wrote the Federal Statistical Office in March 2013. The asparagus acreage in Germany has been growing rapidly for several years. In 2000 it was 15,500 hectares . According to the latest figures, the asparagus acreage increased by 10 percent from 2008 to 2012 to almost 24,000 hectares. In 2013 the largest areas under cultivation are in Lower Saxony (4300 hectares), North Rhine-Westphalia (3200 hectares) and Brandenburg (2900 hectares). More than half of the total German asparagus cultivation area is in these three federal states.

In order to be able to start the harvest season earlier and less dependent on the weather, there are individual growers in various asparagus growing areas who heat their fields. This can sometimes also be done with waste heat , but it is controversial.

Important German asparagus growing areas are:

-

Schleswig-Holstein

- in Aukrug near Neumünster

- in the Lauenburg region

-

Lower Saxony

- District of Diepholz

- District of Nienburg / Weser

- northwest and north near Braunschweig

- near Burgdorf , Fuhrberg and Neustadt a. Rbge in the Hanover region

- near Bardowick near Lüneburg

- smaller locations in the Lüneburg Heath

- in Artland , Osnabrück district

- in the southern Osnabrück region ( Glandorf , Bad Iburg )

-

North Rhine-Westphalia

- on the left Lower Rhine asparagus village Kessel and at Walbeck , a district of Geldern

- in Brüggen-Bracht and Effeld , on the Dutch border.

- between Cologne and Bonn ( foothills )

- the Münsterland , but also on the border area between the Ruhr area and Münsterland

- the dairy farm near Paderborn

-

Brandenburg and Saxony-Anhalt

- the Zauche around Beelitz southwest of Berlin

- Beetz / Sommerfeld in the Brandenburg district of Oberhavel

- the Lower Lausitz , with production areas when Sallgast , Walddrehna , Werenzhain

- the Altmark around Osterburg , Stendal , Seehausen and Klötze

- Hohenseeden and Parchen in Jerichower Land

-

Thuringia

- in the entire Thuringian Basin at different locations, e.g. B. Herbsleben and Kutzleben

- in Altenburger Land and the adjacent area in West Saxony

-

Hesse

- the southern Hessian sandy soil region near Weiterstadt , Griesheim and Pfungstadt west of Darmstadt

- in the district of Groß-Gerau ( South Hesse )

- in Rodgau , the area between Mühlheim am Main and Dieburg

- in the Bergstrasse district mainly in Lampertheim

-

Rhineland-Palatinate

- the Rhine Palatinate

- in the old Rhine sand of Rheinhessen ( Rhineland-Palatinate )

-

Baden-Württemberg

- the North Baden Hardt region with the largest asparagus market in Europe in Bruchsal

- in Südbaden im Breisgau near Munzingen , a district of Freiburg im Breisgau , on and on the Tuniberg

- in North Baden in Hügelsheim in the Rastatt district , near Malsch in the Karlsruhe district

- in the Rhein-Neckar district near Schwetzingen , Oftersheim , Reilingen , St. Leon

- interspersed in the fruit-growing areas around Lake Constance and the Schussental (Tettnang, Meckenbeuren, Ravensburg) in Upper Swabia

-

Bavaria

- near Abensberg in Lower Bavaria

- since 1912 with Schrobenhausen in Upper Bavaria

- the Franconian garlic country between Erlangen and Nuremberg

- the region south of Nuremberg around Schwabach

- the Bamberg area

- in the area of the Franconian Main Triangle

- Ochsenfurt Gau [Allersheim]

There is a European Asparagus Museum in Schrobenhausen ; further asparagus museums were set up in Schlunkendorf near Beelitz and in Nienburg an der Weser. In Baden , the Badische Asparagus Road leads through the growing areas. In Lower Saxony there is the Lower Saxony Asparagus Route .

Cultivation outside of Germany

While Germany is the largest producer in Europe and fourth largest in the world with 103,107 t, the People's Republic of China (7,000,000 t) is by far the largest producer in the world, followed by Peru (383,144 t) and Mexico (126,421 t).

On the other places (5 to 15) follow Thailand, Spain, USA, Japan, Italy, Iran, France, the Netherlands, Chile, Australia and Argentina.

criticism

Since asparagus is the type of vegetable with the largest cultivation area in Germany (almost a fifth of the federal German cultivation area of vegetables in the open air), but the yield per hectare is significantly lower than with other types of vegetables, it is often criticized that the cultivation of the "luxury product" asparagus is not consistent with an efficient use of agricultural land. In addition to world food issues, the increasing importance of the alternative use of arable land (e.g. flower meadows ) also play a role. This applies to cultivation in Germany as well as in third countries such as B. Peru. Furthermore, the use of plastic sheeting, heatable fields and the import from third countries by plane, which have a negative effect on the ecological balance of asparagus, as well as the working conditions during cultivation are criticized.

Use in the kitchen

Asparagus is a very delicate vegetable and should be handled carefully from harvest to preparation. Good white or purple asparagus can be recognized by closed heads, uniform growth, a still damp, not hollow end (if you press your fingernail, moisture should escape) and the squeaking noise that fresh asparagus stalks make when rubbed together. Thin bars are of poor quality. The normalized in the EU before 2011, since in the commercial practice, and as UNECE standard or common commercial grade 1 required on white asparagus a diameter of 10 millimeters, the classification of 1+ or Extra of 12 millimeters or more, while the classification 2 may be unsorted or can have smaller bars from 8 millimeters. Green asparagus can be a little thinner, the head is already slightly open due to the exposure to light.

Asparagus should be eaten fresh as possible, but will keep in the refrigerator for two to three days if you wrap it in a damp towel. It can be peeled (and also already cooked) frozen without any problems and can then be kept for a long time. However, the taste quality is reduced. Peeling after freezing and thawing is not possible.

preparation

Asparagus is mostly boiled, less often steamed or fried. White and purple asparagus must be peeled in preparation, as the peel is fibrous and tough. To peel, start a little below the head and peel towards the end of the asparagus. A piece should be cut off from it (if it is fresh, about 1 cm, otherwise more), as it can be woody and / or bitter. The leftovers can be boiled to make a stock as a soup base or to cook the asparagus. Green asparagus often does not have to be peeled, often only the lower third. Approximately 500 grams of asparagus per person (based on the unpeeled vegetables) is appropriate.

Since the tender heads cook faster than the rest, asparagus should be cooked upright - carefully tied - in a narrow, high saucepan at a moderate temperature. The pot must not be made of aluminum, otherwise the asparagus will turn gray due to aluminum compounds. The water is enriched with salt , a little sugar and a piece of butter and should only reach just below the head. You can add lemon juice , which gives the asparagus a light color but slightly covers the aroma. Depending on the thickness, the asparagus is cooked for 8 to 15 minutes. In modern kitchens, asparagus is also prepared more “biting”. It is cooked for about three to four minutes and then has to steep for six to eight minutes.

Cooking the asparagus in its own juice without water is particularly gentle on the aroma and ingredients, which some cooks implement accordingly. To do this, the peeled asparagus is either steamed in a closed pot for 15 to 20 minutes on its own peels and sections or cut into pieces in a pan with other ingredients. Asparagus is also easy to fry, ideally divided into narrow pieces. Asparagus can also be eaten raw, for example as a salad. However, the typical asparagus taste is less present in raw form.

Classically, asparagus is served with boiled young potatoes , melted butter, hollandaise sauce or mayonnaise and ham . In the region around the Lower Rhine , asparagus is also consumed with melted butter and scrambled eggs , in the Mark Brandenburg with breadcrumbs roasted in butter . As a variant, a fried veal schnitzel is served with asparagus, and the combination of asparagus with fried or steamed fish has been gaining in importance for around 20 years. In Baden , asparagus is served with patties or Kratzete (Schmarrn) and boiled ham. Around Nuremberg , asparagus is usually served in the form of asparagus salad made from whole, cooked sticks with coarse Franconian sausages or small Nuremberg sausages. Bolzano sauce , a kind of mayonnaise made from boiled eggs, is common in South Tyrol . In some regions of Schleswig-Holstein , asparagus is also consumed with "sweet" ( shiny ) jacket potatoes . These jacket potatoes are fully cooked and peeled again in a pan with butter and sugar, served with ham and hollandaise sauce.

Ingredients and effects

| Nutritional value per 100 g asparagus ( Asparagus officinales L. ), raw | |

|---|---|

| Calorific value | 86 kJ (20 kcal) |

| water | 93.1 g |

| protein | 1.96 g |

| carbohydrates | 2.04 g |

| - fiber | 1.27 g |

| fat | 0.16 g |

| Vitamins and minerals | |

| vitamin C | 20.0 mg |

| Vitamin E. | 2.1 mg |

| Calcium | 26 mg |

| iron | 675 µg |

| magnesium | 17 mg |

| sodium | 4.3 mg |

| phosphorus | 44 mg |

| potassium | 203 mg |

| zinc | 396 µg |

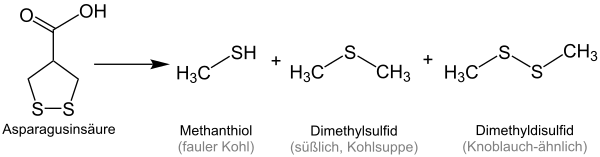

The main component of asparagus is water. It also contains some vitamins and minerals, which are shown in the nutritional table. Due to the asparagine it contains and its high potassium content, it has a diuretic effect . When consumed, the excreted urine may have a strong odor ( urine odor , asparagus urine ). Responsible for the strong smell of urine after eating asparagus is contained in asparagus asparagusic acid . In about 40% of people, this is enzymatically split into sulfur-containing compounds such as methanethiol (a thiol ), dimethyl sulfide (a sulfide ) or dimethyl disulfide (a disulfide ). The individual compounds are odor-active and have characteristic smells, which are shown in the figure.

These and other odorous compounds are excreted in the urine. Together they form the characteristic odor of asparagus urine. It is not known why some people produce the reaction products in observable concentrations and others do not. Not all people can perceive these substances because, due to a mutation in the gene of an olfactory receptor, they cannot smell the specific scent of sulfur-containing compounds. Such loss of smell is known as anosmia .

consumption

Asparagus is considered a difficult dish in terms of observing table manners. In the past, asparagus was mainly consumed with the fingers. The simple reason for this was that the cutlery of the time was made of silver or non-stainless steel and tarnished due to sulfur-containing compounds in asparagus. Eating asparagus with your fingers was not a restriction or a violation of etiquette. Nowadays, knives and forks are used, especially on fine occasions.

Common names

In German-speaking countries, the following other trivial names are or were used for this plant species, sometimes only regionally: Aspars ( Holstein ), God's herb ( Livonia , the name refers to the use of the plant to decorate images of saints), Heirbeswurz ( Old High German ) , Hosendall ( Transylvania ), Korallenkraut ( Silesia , East Prussia ), Schwammwurz ( Switzerland ), Spahrsch ( Low German ), Sparge (Old High German), Spajes ( Weser ), Sparjes (Weser), Spargen, Spargle (Switzerland), Spargus ( Pomerania ), Sparig, Spars (Holstein, Switzerland), Sparsach ( Schaffhausen , St. Gallen ), Sparsich (Schaffhausen, St. Gallen), Sparsen ( Graubünden ), Spart ( East Germany ), Sparz ( Vierwaldstätte ), Speis ( Unterweser ) and Teufelstrauben.

history

Asparagus (天 門冬 Tiān mén dōng. Asparagus lucidus ) were already listed in the oldest Chinese medicinal plant book, the Shennong ben cao jing . The currently valid Chinese pharmacopoeias recommend asparagus for the following diseases: emptiness-exhaustion cough, palpitations and insomnia, intestinal dryness-constipation, internal heat and strong thirst.

The Roman author Columella mentions it in his book De re rustica . As a medicinal plant, wild asparagus was used, which, according to Dioscurides, should have a diuretic and laxative effect and help against jaundice . It was used with these indications until the 19th century.

With the Romans and their culture, asparagus probably also found its way across the Alps ( a lead price tag for asparagus from the 2nd century was found in Trier in 1994). With the decline of Roman culture, asparagus cultivation also disappeared. The cultivation is not occupied again until the 16th century - asparagus was considered an expensive delicacy in aristocratic circles.

In the past, the root was recognized as a remedy ( officinal ); the seeds were used as a coffee substitute.

swell

- Antiquity - late antiquity: Theophrast 4th century BC - Dioscurides 1st century --- Pliny 1st century --- Galen 2nd century --- Pseudo-Apuleius 4th century

- Arab Middle Ages: Avicenna 11th century --- Circa instans 12th century --- Pseudo-Serapion 13th century --- Ibn al-Baitar 13th century

- Latin Middle Ages: Michael Puff 15th century --- Herbarius Moguntinus 1484 --- Garden of Health 1485 --- Hortus sanitatis 1491 --- Hieronymus Brunschwig 1500

- Modern times: Otto Brunfels 1537 --- Hieronymus Bock 1539 --- Leonhart Fuchs 1543 --- Mattioli / Handsch / Camerarius 1586 --- Tabernaemontanus 1588 --- Nicolas Lémery 1699/1721 --- Onomatologia medica completa 1755 --- William Cullen 1789/90 --- Jean-Louis Alibert 1805/05 --- Pierre-Jean Robiquet 1805 --- Louis-Nicolas Vauquelin and PJ Robiquet 1806 --- August Husemann , Theodor Husemann 1871

Historical illustrations

..... Pseudo-Apuleius ... ..... Kassel 10th century .....

..... Abdul ibn Butlan ..... ..... 14th century

... Herbarius Moguntinus .......... Mainz 1484 .....

... garden of health ......... Mainz 1485

...... Hortus sanitatis .......... Mainz 1491

Left: Hortus sanitatis 1497. Right: Small distilling book 1500

Otto Brunfels 1537

Leonhart Fuchs 1543

Tabernaemontanus 1588

See also

literature

- Klaus Englert, Hans-Peter Wodarz: Asparagus: History - Cultivation - Recipes. HLV Ludwig, Pfaffenhofen 1985, ISBN 3-7787-2067-8 .

- Klaus Englert, Grieser, Hastreiter, Heller; Hans-Peter Wodarz (Ed.): Asparagus - From the magic of asparagus. With watercolors by Kurt Sauer. Edition q, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-86124-060-2 .

- Franz Göschke: The rational asparagus farming . Berlin 1882.

- Burmester and Bültemann: asparagus growing. Braunschweig 1880, OCLC 258246658 .

- Gerhard Sulzmann: asparagus fruit for pleasure. [divine vegetables] In: AV book. Österreichischer Agrarverlag, Leopoldsdorf 2005, ISBN 3-7040-2079-6 (with recipes and wine recommendations from Manfred Buchinger).

- Oskar Sebald, Siegmund Seybold, Georg Philippi , Arno Wörz: The fern and flowering plants of Baden-Württemberg. Volume 7, Ulmer, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-8001-3316-4 .

- Udelgard Körber-Grohne: Useful Plants in Germany. The competent reference work. Nikol, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-933203-40-6 .

Web links

- Vegetable asparagus. In: FloraWeb.de.

- Vegetable asparagus . In: BiolFlor, the database of biological-ecological characteristics of the flora of Germany.

- Profile and distribution map for Bavaria . In: Botanical Information Hub of Bavaria .

- Asparagus officinalis L., map for distribution in Switzerland In: Info Flora , the national data and information center for Swiss flora .

- Overall Distribution Map

- Thomas Meyer: Data sheet with identification key and photos at Flora-de: Flora von Deutschland (old name of the website: Flowers in Swabia )

- Schrobenhausen European Asparagus Museum

- Asparagus ingredients

- Lower Saxony Asparagus Museum

- History of asparagus, uses in cooking and medicine

- Causes of the smell of asparagus in the urine

- Working group for agricultural quality standards: UNECE-NORM FFV-04 for the marketing and quality control of ASPARAGUS. Edition 2017. Ed .: United Nations. New York and Geneva June 22, 2018 ( unece.org PDF; 78 kB, English: UNECE STANDARD FFV-04 ASPARAGUS. 2018).

Individual evidence

- ^ Friedrich Kluge , Alfred Götze : Etymological dictionary of the German language . 20th edition. ed. by Walther Mitzka . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1967. (21st unchanged edition. Ibid. 1975, ISBN 3-11-005709-3 , p. 720.

- ↑ sec : the or the asparagus; Plural: the asparagus, (mostly in Swiss :) the asparagus.

- ^ Asparagus ( memento of August 6, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) at the Information Center against Poisoning of the University of Bonn

- ↑ a b Erich Oberdorfer : Plant-sociological excursion flora for Germany and neighboring areas . With the collaboration of Angelika Schwabe and Theo Müller. 8th, heavily revised and expanded edition. Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart (Hohenheim) 2001, ISBN 3-8001-3131-5 , pp. 135-136 .

- ↑ a b c Crops> aspargus. In: FAO production statistics for 2018. fao.org, accessed on February 23, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Crops and livestock products> aspargus. In: FAO trade statistics. fao.org, accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ^ The special culture of asparagus in Pleidelsheim - cultivation and history. ( Memento from February 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Pleidelsheim community

- ↑ Albert Kraft: Practical guide to the cultivation of kitchen plants, flowers, dwarf fruits, berries and table grapes in the open country. Reprint of the original edition from 1890. UNIKUM, 2012, ISBN 978-3-8457-4070-6 , p. 73.

- ^ FA Hexamer: Asparagus - Its culture for home use and for market - A practical treatise on the planting, cultivation, harvesting, marketing and preserving of asparagus, with notes on its history and botany. Original: Orange Judd Company, New York 1914; The Project Gutenberg [EBook # 31643] March 14, 2010, accessed May 22, 2014 .

- ↑ Overview of the history of the Southwest German seed breeding. Südwestdeutsche Saatzucht GmbH & Co. KG, accessed on January 10, 2014 .

- ↑ Manfred Ernst: Asparagus in the garden. Deutscher Landwirtschaftsverlag, Berlin 1979, p. 17.

- ↑ Limseeds. (No longer available online.) Limgroup, archived from the original on January 10, 2014 ; accessed on January 10, 2014 .

- ↑ The Southwest German Saatzucht. Südwestdeutsche Saatzucht GmbH & Co. KG, accessed on January 10, 2014 .

- ↑ German asparagus farming. German asparagus cultivation, accessed on January 10, 2014 .

- ↑ Protected / approved varieties - List of varieties. Bundessortenamt, accessed on May 22, 2014 .

- ^ Hermann Kuckuck, Gerd Kobabe, Gerhard Wenzel: Basic features of plant breeding. 5th edition. de Gruyter, p. 138.

- ↑ State variety trial asparagus: The variety is decisive for quality and yield. (No longer available online.) Bavarian State Institute for Viticulture and Horticulture, archived from the original on January 10, 2014 ; accessed on January 10, 2014 .

- ↑ Asparagus, New Varieties, White Asparagus, Variety Trials, Variety Testing. Lower Saxony Chamber of Agriculture, accessed on January 10, 2014 .

- ↑ Variety overview of the European Plant Variety Office, 74 entries. Community Plant Variety Office (CVPO), accessed May 22, 2014 .

- ↑ haploid breeding --pflanzenforschung.de. Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), accessed on April 2, 2018 .

- ↑ ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: Freshness decides on taste. ) At the Bavarian Farmers' Association

- ↑ Asparagus cultivation

- ↑ Stechmesser the company. Firmenich / Solingen

- ↑ The machine is supposed to replace the asparagus cutter

- ↑ Harvester tested: Kirpy

- ↑ "Asparagus - the royal vegetable" Cultivation tips - trends, innovations - recipes (PDF; 590 kB) Chamber of Agriculture North Rhine-Westphalia, p. 4.

- ↑ Asparagus is the most common outdoor vegetable. Federal Statistical Office, accessed on January 10, 2014 .

- ↑ Asparagus 2013: acreage increases, yield decreases. ( Memento from January 10, 2014 in the web archive archive.today ) Federal Statistical Office

- ↑ Asparagus farming: Giant heating for precious vegetables on: tagesspiegel.de , April 13, 2001.

- ↑ Asparagus only sprouts with heating. on: augsburger-allgemeine.de , March 22, 2013.

- ↑ Asparagus thanks to the huge heating in the ground. on: aachener-zeitung.de March 20, 2009.

- ↑ Werenzhain .: Everything has to be right for asparagus :: lr-online. In: www.lr-online.de. Retrieved June 20, 2016 .

- ↑ statista Top 15 producers of asparagus worldwide in 2013 (in tons)

- ↑ Asparagus: Production: How is asparagus grown? In: Federal Center for Nutrition. Retrieved May 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Vegetable cultivation in Germany in 2011. (PDF) In: Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture. Retrieved May 19, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Environmental sin & exploitation: Are there better asparagus? May 13, 2016, accessed May 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Ecological madness: which asparagus is acceptable? In: sueddeutsche.de . April 15, 2015, ISSN 0174-4917 ( sueddeutsche.de [accessed on May 19, 2019]).

- ↑ Environment & Resources Living ecologically Eating & Drinking Elegant paleness has its price. NABU, accessed May 19, 2019 .

- ^ Federal Center for Nutrition (Germany): Asparagus: labeling ; Obsolete to the legal basis, but as a presentation of a common understanding: Georg Köster: Handelsklassen on www.spargelseiten.de; UNECE standard for asparagus (pdf)

- ↑ a b Souci, SW, specialist, W. & Kraut, H. (2016): The composition of food nutritional tables . 8th edition. Stuttgart: Scientific publishing company. Pp. 788-789, ISBN 978-3-8047-5073-9 .

- ^ Waring, RH, Mitchell, SC & Fenwick, GR: The chemical nature of the urinary odor produced by man after asparagus ingestion . In: Xenobiotica . 1987, PMID 3433805 .

- ↑ M. Lison, SH Blondheim, RN Melmed: A polymorphism of the ability to smell urinary metabolites of asparagus. In: British medical journal. Volume 281, Number 6256, 20.-27. Dec 1980, pp. 1676-1678, ISSN 0007-1447 . PMID 7448566 . PMC 1715705 (free full text).

- ^ Drescher, D .: An explosive question - not only for medical laypeople; Why does urine smell? In: Uro-News . tape 22 , no. 5 , 2018, p. 24-28 .

- ↑ Pelchat, ML, Bykowski, C., Duke, FF & Reed, DR: Excretion and perception of a characteristic odor in urine after asparagus ingestion: a psychophysical and genetic study . In: Chemical senses . tape 36 , no. 1 , 2011, ISSN 1464-3553 , p. 9-17 , doi : 10.1093 / chemse / bjq081 .

- ↑ If the urine smells like asparagus. aerztezeitung.de, accessed on May 9, 2009 .

- ^ Georg August Pritzel , Carl Jessen : The German folk names of plants. New contribution to the German linguistic treasure. Philipp Cohen, Hannover 1882, p. 47, online.

- ↑ Quoted from Bencao Gangmu , Book 14 (Commented Reprint, PR China 1975, Volume II, p. 1281).

- ↑ George Arthur Stuart: Chinese Materia Medica. Vegetable Kindom. Shanghai 1911, p. 55 f .: Asparagus lucidus (天 門冬 Tiān mén dōng) (digitized version ) .

- ↑ Quoted and translated from: Pharmacopoeia of the PR China 1985. Volume I, p. 38.

- ^ Lothar Schwinden: Asparagus - Roman asparagus: a new lead label with graffiti from Trier. In: Finds and excavations in the Trier district. Issue 26, 1994.

- ↑ Theophrastus of Eresus . Natural history of plants . 4th century BC Chr. Edition. Kurt Sprengel . Friedrich Hammerich, Altona 1822, Volume I, p. 217 (Book 6, Chapter 1) Translation (digitized) . Volume II, p. 220 Explanations (digital version)

- ↑ Pedanios Dioscurides . 1st century De Medicinali Materia libri quinque. Translation. Julius Berendes . Pedanius Dioscurides' medicine theory in 5 books. Enke, Stuttgart 1902, p. 220 (Book II, Chapter 151): Asparagos (digitized version )

- ↑ Pliny the Elder , 1st century. Naturalis historia Book XX, Chapter 42 (§ 108–111): Asparagus (digitized version) ; Translation Külb 1855 (digitized version )

- ↑ Galen , 2nd century De simplicium medicamentorum temperamentis ac facultatibus , Book VI, Chapter I / 66 (based on the Kühn 1826 edition, Volume XI, p. 841: Asparagus (digitized version)

- ↑ First printing: Rome 1481, Chapter 87 (digitized version )

- ↑ Avicenna , 11th century, Canon of Medicine . Translation and adaptation by Gerhard von Cremona , Arnaldus de Villanova and Andrea Alpago (1450–1521). Basel 1556, Volume II, Chapter 611 (p. 299): Sparagus (digitized version )

- ↑ Circa instans , 12th century, print. Venice 1497, sheet 210r: Sparagus (digitized)

- ^ Pseudo-Serapion 13th century, print. Venice 1497, sheet 99r (No IIII): Sparagus (digitized)

- ↑ Abu Muhammad ibn al-Baitar , 13th century, Kitāb al-jāmiʿ li-mufradāt al-adwiya wa al-aghdhiya. Translation. Joseph Sontheimer under the title Large compilation on the powers of the well-known simple healing and food. Hallberger, Stuttgart Volume II 1842, pp. 570-572 (digitized version )

- ↑ Michael Puff . Little book about the burnt-out waters . 15th century print Augsburg (Johannes Bämler) 1478 (digitized)

- ↑ Herbarius Moguntinus , Mainz 1484, Part I, Chapter 131: Spargus (digitized version )

- ↑ Gart der Gesundheit . Mainz 1485, chapter 389: (digitized version)

- ↑ Hortus sanitatis , Mainz 1491, Part I, Chapter 523: (digitized version)

- ↑ Hieronymus Brunschwig : Small distilling book . Strasbourg 1500, sheet 108v (digitized version )

- ^ Otto Brunfels : Ander Teyl des Teütschen Contrafayten Kreüterbůchs. Johann Schott, Strasbourg 1537, pp. 24-25 (digitized version)

- ↑ Hieronymus Bock : New Kreütter Bůch. Wendel Rihel, Strasbourg 1539, part I, chapter 74 (digitized version)

- ^ Leonhart Fuchs : New Kreütterbuch [...]. Michael Isingrin, Basel 1543, Chapter 17 (digitized version)

- ^ Pietro Andrea Mattioli . Commentarii, in libros sex Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei, de medica materia. Translation by Georg Handsch, edited by Joachim Camerarius the Younger , Johan Feyerabend, Franckfurt am Mayn 1586, sheet 145r – 145v (digitized version )

- ↑ Tabernaemontanus : Neuw Kreuterbuch. Nicolaus Basseus, Frankfurt am Main 1588, pp. 515-520 (digitized version )

- ↑ Nicolas Lémery : Dictionnaire universel des drogues simples. P. 71 (digitized version) ; Translation. Complete material lexicon. Initially designed in French, but now after the third edition, enlarged by a large one [...] translated into High German / by Christoph Friedrich Richtern, [...]. Leipzig: Johann Friedrich Braun, 1721, Sp. 115 (digitized)

- ^ Albrecht von Haller (editor). Onomatologia medica completa or Medicinisches Lexicon that explains all names and artificial words that are peculiar to the science of medicine and pharmacist art clearly and completely [...]. Gaumische Handlung, Ulm / Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 1755, pp. 150–151 (digitized version )

- ^ William Cullen, A treatise of the materia medica. Charles Elliot, Edinburgh 1789. Volume I, pp. 267-268 (digitized version ) . German. Samuel Hahnemann . Schwickert, Leipzig 1790. Volume I, pp. 294–295 (digitized version )

- ^ Jean-Louis Alibert Nouveaux éléments de thérapeutique et de matière médicale. Crapart, Paris Volume I 1803, pp. 548–549 (digitized version )

- ^ PJ Robiquet : Essai analytique des asperges. In: Annales de Chimie . Volume 55 (1805), pp. 152–171 (digitized version )

- ^ Louis-Nicolas Vauquelin and Pierre-Jean Robiquet. Découverte d'un nouveau principe végétal dans les Asperges (aspagarus sativus. Linn.) . In: Annales de Chimie . Volume 57 (1806), pp. 88–93 (digitized version )

- ↑ August Husemann , Theodor Husemann : The plant substances in chemical, physiological, pharmacological and toxicological terms. For doctors, pharmacists, chemists and pharmacologists. Springer, Berlin 1871, pp. 671–675: asparagine , aspartic acid (digitized)

- ↑ Asparagus harvest. In: Abdul ibn Butlan : Tacuinum sanitatis in medicina. 13th century, Codex Vindobon. Ser. Nova 2644, sheet 26v. Translation of the text by Franz Unterkircher: Tacuinum sanitatis … Graz 2004, p. 66: “Asparagus: Complexion: warm and moist in the first degree. Preferable: fresher, the tips of which lean towards the ground. Benefit: it strengthens sexual potency and opens constipation. Damage: it damages the stomach tissues. Prevention of harm: when cooked, it should be enjoyed with salted water and vinegar. What it creates: good nutrients. Beneficial for people with cold and dry complexion, for old people and the weak, in spring and in all areas where it is found. "