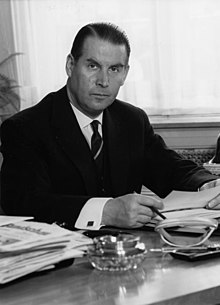

Gerhard Schröder (CDU)

Gerhard Schröder (born September 11, 1910 in Saarbrücken , † December 31, 1989 in Kampen on Sylt ) was a German politician ( CDU ). The lawyer was Federal Minister of the Interior from 1953 to 1961, Federal Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1961 to 1966 and Federal Minister of Defense from 1966 to 1969 .

Schröder was seen as dynamic and competent, but aloof. As Foreign Minister, he shaped in particular the Ostpolitik and the partnership between the Federal Republic of Germany and the USA and Great Britain ( integration with the West ). In the election of the German Federal President in 1969, he was defeated by the SPD candidate Gustav Heinemann with the narrowest result to date in a federal assembly .

Youth and education

Gerhard Schröder was born in Saarbrücken in 1910 as the eldest of three children of Jan Schröder , a railway official from East Friesland , and Antina Schröder, née Duit. He attended humanistic grammar schools (the Ludwigsgymnasium in Saarbrücken , a grammar school in Friedberg, the Landgraf-Ludwigs-Gymnasium Gießen ) and graduated from today's Max-Planck-Gymnasium in Trier in 1929.

After graduating from high school, Schröder began studying law at the Albertus University in Königsberg because he wanted to gain new experience far from his hometown. He later studied for two semesters at the University of Edinburgh , where he was impressed by the British way of life, to which he felt a lifelong connection. From the summer of 1931 he was a student in Berlin , where he experienced the sometimes bloody confrontations between political opponents in the final phase of the Weimar Republic , and soon afterwards he moved to the University of Bonn . During this time he was involved in university politics and was a member of the DVP university group . For this he also moved into the AStA of the university.

In Bonn, Schröder completed his law studies in 1932 with the first state examination and in 1936 with the second state examination.

Assessor time and lawyer in Berlin 1933–1939

In 1934 he was promoted to Dr. jur. PhD. His dissertation with the title The Extraordinary Dissolution of Collective Agreements was written before the National Socialists came to power, so that it was obsolete under the new legislation passed by the National Socialists and was nothing but paperwork. The university therefore released him from the obligation to have the doctoral thesis printed.

From 1933 he was initially an assistant at the law faculty of the University of Bonn. From October 1934 to 1936 he was a consultant at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Comparative and International Private Law in Berlin. In 1935 he had to visit the Hanns Kerrl trainee camp near Berlin for three months, where he said he disliked the political indoctrination. Then in 1936 he became an associate lawyer in a large law firm whose employees were predominantly Jews. His head of the firm and later partner, Walter Schmidt, attested to him in the denazification procedure that he had stood by Jewish and other persecuted clients at the time, so that he had often had problems with the National Socialist Lawyers' Association , to which he belonged under membership number 013115. In 1939 he became a lawyer specializing in tax law .

Second World War 1939–1945

In September 1939 he was drafted into the Wehrmacht and trained as a radio operator near Berlin. From September 1940 to May 1941 he received an exemption from the Wehrmacht and worked in his office in Berlin during this time. He was then sent to the occupied Denmark to Silkeborg and the island of Fanø . During the Russian campaign he got into the Kolm pocket and was wounded there by a shrapnel in his right lower leg , so that he was unfit for war until 1943. After his recovery he was employed as a radio instructor (most recently in the rank of non-commissioned officer ) near Berlin and surrendered to the US troops near Calbe in 1945 . He was interned in a British POW camp near Bad Segeberg , where he was a translator. In June 1945 he was released from captivity .

family

His wife Brigitte Schröder , whose brother was a friend and fellow student of Schröder, was considered a “mixed race” according to the Nuremberg Laws due to her partly Jewish origin. The wedding was therefore only possible with a special permit from the Wehrmacht. Schröder had to forego a military career in writing, so that he only held the rank of corporal in the Wehrmacht. The wedding took place in May 1941 as a distance wedding . Gerhard and Brigitte Schröder had three children:

- Christina (* December 1941)

- Jan (* May 1943)

- Antina (born October 1945)

Professional activity 1945–1953

After his release from captivity, he met his wife again in Hamburg , who had fled the Red Army with their children from their parents' manor in Silesia . There they initially lived with his parents. His father Jan died on November 24, 1945.

As a civil servant 1945–1947

In 1945 Schröder applied to the Upper President of the Rhine Province, Hans Fuchs, in Düsseldorf and received a position as a senior government councilor . He kept this even after the British occupation forces replaced Fuchs with Robert Lehr . During this time he also made contact with Konrad Adenauer and Kurt Schumacher .

At the turn of the year 1945 to 1946 he became head of the German electoral law committee in the British occupation zone . This committee had the task of making proposals to the British occupying forces for the course of the first local elections .

When the state of North Rhine-Westphalia was founded, he was transferred to the Ministry of the Interior , where he was also responsible for election issues at state level. With the then SPD -Minister Walter Menzel , there was no constructive cooperation, which significantly to its adherence to the system of proportional representation was while Schroeder a majority vote favored. When a former member of the SS by the name of Hans-Walter Zech-Nenntwich , who was working as a British agent under his new name Nansen , became an advisor to the Minister of the Interior, Schröder arranged for his dismissal, but then resigned himself because of the trust he had with his employer was no longer given. Zech-Nenntwich was later convicted of war crimes .

North German Iron and Steel Control 1947–1953

From 1947 to 1953 he worked as a lawyer and as a department head at "North German Iron and Steel Control" (NGISC). He was the advisor to Heinrich Dinkelbach , the head of the NGISC. During this time he had also become a member of the supervisory boards of two steel companies, the Hüttenwerk Haspe AG in Hagen and the Duisburg Ruhrort-Meiderich AG. His rejection of the KPD , which was strongly represented on both supervisory boards , also originated from this time .

In 1948 Elisabeth Nuphaus became his closest colleague, who worked for him until 1980.

Parties 1933–1989

NSDAP 1933-1941

On April 1, 1933 Schroeder came under the membership number 2177050 in Bonn in the NSDAP one. At the urging of the President of the Higher Regional Court, he became a member of the SA together with all other trainee lawyers . When he moved to Berlin in 1934, however, he did not renew his membership. On May 1, 1941, Schröder resigned from the NSDAP.

CDU 1945–1989

In 1945 Schröder was one of the founders of the CDU. In the period up to 1949 he was considered a leading expert on electoral law in his party and therefore headed the Arithmetic Committee in 1948 , which recommended that the CDU advocate majority voting.

From 1950 to 1979 he was a member of the executive board of the Rhenish CDU.

From 1967 to 1973 he was Deputy Federal Chairman of his party. He was elected at the federal party conference in Braunschweig with 405 of 562 votes, it was the best result of the five elected deputies of Kiesinger . In November 1970 he was confirmed in this office, but with the worst result of the elected candidates.

At the federal party convention in Saarbrücken in 1971, he had agreed with Helmut Kohl to actively support his candidacy for party chairmanship in return for the Union's candidate for chancellor in the next federal election. The main competitor was Rainer Barzel , who immediately sought both posts in order to combine them with his parliamentary group chairman. At the crucial moment, Schröder hesitated to support Kohl and subsequently did not become the next candidate for Chancellor.

In the 1972 federal election , Schröder was part of the core team of CDU candidate Rainer Barzel, along with Franz Josef Strauss and Hans Katzer, and represented the areas of foreign and security policy.

Evangelical working group of the CDU

In May 1952, the Evangelical Working Group of the CDU and CSU was founded in Siegen in order to open the Catholic-dominated Union to interdenominational standards. After the first two speakers of the EAK, Hermann Ehlers and Robert Tillmanns , died in office in 1954 and 1955, respectively, the delegates unanimously elected Gerhard Schröder as their new speaker on December 2, 1955 . Schröder previously had no house power of his own within the CDU , so that through this office he was able to continue to establish himself in the inner circle of the party leadership. Since then, his name has often been mentioned speculatively in the media as a possible candidate for chancellor of the Union. Schröder was one of the most important representatives of the Protestant part of the Union and from 1955 to 1978 spokesman for the EAK throughout. His successor was the future Federal President Roman Herzog .

Election of the Federal President in 1959

Since Theodor Heuss was not available for a third term as Federal President , which would have required a constitutional amendment, the Union had to find a new candidate. In January 1959, Schröder was sent to Ludwig Erhard to examine whether he would be available for the highest office of the state. But Erhard waved it off. Schröder then belonged to the 16-person selection committee of the two Union parties that proposed Erhard as a candidate for the office of Federal President on February 24, 1959. However, this refused again.

When Chancellor Adenauer brought himself into play as a candidate for the office of Federal President, Schröder was immediately in favor of this option. But when it turned out that Ludwig Erhard saw himself as a candidate for chancellor, supported by the parliamentary group and public opinion, Adenauer rejected his own candidacy again, to Schröder's chagrin. Already there were signs of the growing struggle between Erhard and Adenauer for Adenauer's successor, since the latter wanted to prevent Erhard as Chancellor with all available means. With all his sympathy for Erhard, Schröder was always loyal to Adenauer, who lost a lot of his reputation in this party crisis. A survey by the Emnid opinion research institute at that time showed a majority for Ludwig Erhard of 51 percent to 32 percent for Konrad Adenauer when it came to the chancellor question.

Since Adenauer was now looking for alternatives to Erhard, Schröder first came into his focus when he announced him to some party friends, alongside Kai-Uwe von Hassel and Heinrich Krone, as a possible challenger to Erhard.

MP 1949–1980

Before serving as minister in the Bundestag 1949–1953

From 1949 to 1980 Schröder was a member of the German Bundestag .

Characterized by his previous work in the steel trust administration, Schröder campaigned for the Works Constitution Act , which was passed on November 14, 1952, within the CDU parliamentary group .

In 1952 Schröder belonged to a group of 34 members of the CDU / CSU parliamentary group who introduced a bill to introduce relative majority voting in the Bundestag, which, however, jeopardized the stability of the coalition, as the smaller parties did not support majority voting. Schröder then submitted a motion that provided for a threshold clause in federal elections. The right to vote in the Bundestag today is based on his application.

From June 24, 1952 to October 20, 1953, he was deputy chairman of the CDU / CSU parliamentary group . He gave up this office when he became Federal Minister of the Interior.

From March to mid-April 1953 he followed an invitation from the State Department to the United States with some young politicians in the governing coalition . Various visits to government agencies and military institutions there followed a brief audience with the then President of the United States, Dwight D. Eisenhower .

After serving as Federal Minister in the Bundestag 1969–1980

From 1969 to 1980 he was chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee . In this capacity, he was the first German top politician to receive an invitation to the People's Republic of China . There he negotiated from July 13 to 29, 1972 with the Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai about the later establishment of diplomatic relations.

He also traveled in that capacity in January 1971, the first time in the Soviet Union after Moscow . Despite the visit, Schröder sharply criticized the Eastern Treaty in the Bundestag.

He also met with the new US President Richard Nixon in 1971 to discuss détente policy. Nixon and Schröder knew each other from their time as US Vice President and Federal Minister of the Interior, respectively.

On April 27, 1972, when the CDU / CSU parliamentary group brought the first constructive vote of no confidence in the German Bundestag, he replied to the then Federal Foreign Minister Walter Scheel's speech on the foreign policy of the social-liberal coalition and thus justified the foreign policy proposal of the CDU / CSU parliamentary group on the election of the Brandt government and the election of Rainer Barzel.

He had a controversial meeting at the end of 1974 as chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee with Yasser Arafat , which was controversial in the social-liberal governing coalition, but also within the party.

In the debate about the Eastern Treaties , Schröder was a warning against excessive euphoria in the policy of détente; although he supported it, he did not see it as the key to German unity.

After Rainer Barzel had resigned the parliamentary group and party chairmanship on May 9, 1973, which Schröder regretted very much, Schröder ran for this office on May 17, 1973 against his former State Secretary Karl Carstens and again against Richard von Weizsäcker. He was clearly defeated by 28 votes, 58 votes for Weizsäcker and 131 for Carstens, whom Helmut Kohl favored. This defeat marked the end of his life as a top politician, as he was never considered for important offices again and slipped into the status of elder statesman .

Schröder belonged to Ludwig Erhard, Hermann Götz (both CDU), Richard Jaeger , Franz Josef Strauss , Richard Stücklen (all CSU ), Erich Mende ( FDP , later CDU), Erwin Lange , R. Martin Schmidt and Herbert Wehner (all SPD ) to the ten members who have belonged to parliament for 25 years without interruption since the 1949 Bundestag election.

Schröder is the chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee, who held the longest term in office at eleven years of age. His successor was his former companion Rainer Barzel.

Constituency candidate 1949–1969 and list candidate 1972–1976

Gerhard Schröder is last on the national list North Rhine-Westphalia ( 1969 , 1972 and 1976 always) and before that as directly selected delegates of the constituency Dusseldorf-Mettmann and Dusseldorf-Mettmann II ( 1965 ) in the Bundestag drawn in. The former central politician Richard Muckermann was originally supposed to receive this constituency , but the delegates voted for Schröder with a large majority, as the Catholic Muckermann would probably have had no chance in the strongly evangelical constituency. At the first election (1949), Schröder had no list security.

In his first federal election campaign in 1949 , his campaign slogan was For Health-Work-Peace . He won the constituency with 34.1% of the vote and a lead of 2.7 percentage points over his social democratic opponent.

In the election to the 2nd German Bundestag , as a constituency candidate , he received 52 percent of the first votes and thus around four percentage points more than the CDU of second votes.In 1957 he achieved his best result of first votes with 54.2 percent and thus also the best result ever a candidate in that constituency could achieve. In 1961 he received 44.9 percent of the first votes (for comparison: the Union received 45.3% of the second votes). In this election campaign he appeared as a representative of Adenauer in the television program Unter uns Said by Kurt Wessel . Ludwig Erhard was upset that he was not invited to the show as Vice Chancellor.

In the 1965 federal election , Schröder succeeded for the last time in defending his constituency with 48.6 percent of the first votes. In the 1969 Bundestag election , Schröder was unable to defend his constituency for the first time, with the SPD clearly gaining votes. Nevertheless, he moved into the Bundestag because he had received first place on the state list of North Rhine-Westphalia.

In the federal elections in 1972 and 1976 , he ran only on the state list. In 1972 he was second on the list, behind candidate for chancellor Barzel, and in 1976 he was sixth.

In 1980 Schröder wanted to move into the Bundestag again via a place on the state list. However, he was not nominated for three reasons: after losing the state elections in North Rhine-Westphalia in 1980 , the CDU NRW had a surplus of candidates; the Union's candidate for chancellor, Franz Josef Strauss, did not want to see his internal enemy in the 9th Bundestag and the CDU chairman Helmut Kohl was only moderately interested in Schröder in the Bundestag. Schröder was removed from the state list with relatively rough means and his time in the Bundestag ended at the end of the legislative period.

Public offices 1953–1969

Federal Minister of the Interior 1953–1961

Assumption of office

On October 20, 1953, Schröder was appointed to the office of Federal Minister of the Interior by Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer . The decisive factors for this were Schröder's successful result in his constituency in the second general election, the increasing age of his predecessor, his relative youth and his legal training. In addition, Schröder was a Protestant and in the first few years the position of Federal Minister of the Interior was given exclusively to Protestant politicians in order to maintain a certain parity between the denominations in the cabinet. He became the successor to his former superior Robert Lehr.

The Otto John case

On July 17, 1954, the second Federal Assembly met in West Berlin to re-elect Federal President Theodor Heuss. On July 20, there was a memorial hour in Berlin on the 10th anniversary of the assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler . For scheduling reasons, Schröder had already traveled to Bonn in advance to receive the victorious German national soccer team as the Federal Minister responsible for sport after the miracle of Bern . The President of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, Otto John, was present as a former resistance fighter and traveled to the GDR during the night . For a long time Schröder took the position that John must have been kidnapped and offered a reward of 500,000 DM for clues. Most Bonn politicians, however, were of the opinion early on that John had voluntarily fled to what was then the Soviet occupation zone. The Bundestag Committee for the Protection of the Constitution, which was headed by Schröder's former superior Walter Menzel, with whom Schröder had a close hostility, and the SPD parliamentary faction filed a disapproval against Schröder and called for an investigative committee. At the time, the FDP was not sure whether it wanted to support Schröder. However, the simultaneous failure of the European Defense Community forced them to keep the coalition and consequently to support Schröder, so that the disapproval motion did not find a majority and the committee of inquiry could not attest any wrongdoing by Schröder two years later. After John's return to the Federal Republic of Germany in December 1955 and his conviction for treason , Schröder campaigned for Theodor Heuss to be pardoned in 1958 . Sensitized by the events surrounding John, Schröder's top priority was safety. He soon earned a reputation as a law-and-order politician.

Increase in the Federal Border Guard

At the beginning of Schröder's tenure, the only armed force in the state under the federal government was the Federal Border Guard . Due to the events of the uprising in the GDR , the Federal Border Guard was doubled from 10,000 men. When the Bundeswehr was founded, large parts of the BGS provided the personnel of this force voluntarily. In the negotiations, Schröder achieved that the BGS was not fully integrated into the Bundeswehr and that the troop's target strength was soon achieved again.

Ban on the KPD

Schröder pushed through an application for a ban against the KPD . His predecessor in office had already successfully enforced a ban against the Socialist Reich Party and at the same time submitted an application to ban the KPD, which, however, was only approved under Schröder's aegis. An amnesty law for KPD functionaries was successfully fought in parliament by Schröder, although the SPD and FDP supported this draft law, as Herbert Wehner compared Schröder with Andrei Wyschinski , the Soviet accuser of the Stalinist show trials, in the debate . This process was successfully exploited by the CDU in the 1957 federal election campaign.

Civil defense

Schröder placed particular emphasis on civil, air and civil protection. During the Cold War at that time , facilities had to be created for the civilian population in order to protect them as much as possible in the event of war. Schröder therefore undertook an extensive trip to the USA in 1957 to familiarize himself with the security measures there. For example, disaster hospitals were built and the BGS and the federal government used material stores to prepare for various disaster situations in order to alleviate the suffering of the civilian population as quickly as possible.

Fight against nuclear death

When, at the end of the 1950s, the Bundestag decided, through the absolute majority of the CDU and CSU factions, that the Bundeswehr could be armed with nuclear weapons in the event of war, a broad front of the SPD, GVP , DGB and FDP formed to oppose this law under the motto Fight atomic death with a referendum . Schröder was a notorious opponent of plebeian elements in the Federal Republic, as he knew them from the Weimar period and was convinced that extreme parties like the NSDAP and KPD had used this constitutional means to fight against the democratic republic. On July 30, 1958, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled the government, thereby recognizing referendums as unconstitutional. The NATO Council later decided that only the US would have to decide on such a measure in the event of a crisis, rendering the law meaningless.

Emergency legislation

The Germany Treaty between the Federal Republic and the three Western Allied Powers provided for a right of reservation in Article 5, Paragraph 2, which gave the Allies the opportunity to take over command in Germany in an emergency. Schröder's ministry drew up the first draft laws as early as 1958 on the instructions of Federal Chancellor Adenauer, which were announced to the SPD at an early stage, as this change in the constitution required the votes of the SPD parliamentary group in the Bundestag and the federal states led by the SPD. Due to the Berlin crisis , the legislative initiative was blocked. In the end, there was no vote on the emergency laws because the SPD did not want to vote for them. From a confidential letter from an SPD functionary, he learned that the leadership of the SPD never seriously intended to support his draft law and therefore negotiated hesitantly in order to await the result of the 1961 federal election with their fresh and relatively young candidate for Chancellor Willy Brandt .

Adenauer television

Chancellor Adenauer saw himself and his CDU falling behind in the control of ARD . Only the federal states exercised control over their own broadcasters. The federal executive had almost no possibility of intervention. Adenauer therefore founded the Deutschland-Fernsehen GmbH on July 25, 1960 under private law with its seat in Cologne. The SPD-led federal states of Hamburg, Bremen, Lower Saxony and Hesse called the Federal Constitutional Court, which blocked Adenauer's plans with the 1st broadcasting judgment of February 28, 1961. As a result, ZDF was founded in 1962. Schröder was considered an advocate of Adenauer television because, as a “centralist”, he would have liked to curtail the power of the federal states.

Failed initiatives

Schröder failed in court when he tried to ban the unification of those persecuted by the Nazi regime . Likewise, his intention to bundle the state elections failed due to the resistance of the state governments.

Schröder's initiative to pass an entry and exit law to the GDR in the Bundestag did not succeed, whereby the GDR built the Wall in 1961 to make the bill obsolete.

Gerhard Schröder is still the Federal Minister of the Interior with the longest term in office, both as a direct consequence and as a whole.

Federal Foreign Minister 1961–1966

Adenauer cabinet 1961–1963

The way to office

After the general election in 1961, the Union needed a coalition partner in order to govern. Federal Chancellor Adenauer quickly came to an agreement with the FDP, although the new coalition partner insisted that Heinrich von Brentano should be replaced as Federal Foreign Minister. For this office, the FDP favored the Baden-Württemberg Prime Minister at the time, Kiesinger, while Adenauer favored his long-term Interior Minister Schröder or Walter Hallstein . At the same time, the Berlin CDU mobilized all forces to prevent Schröder, who had reprimanded Berlin 's poor strategic position during the Berlin crisis and when the Wall was being built, and had spoken out in favor of giving up the city entirely in order to prevent a war that might arise The Berlin side had little or no trust in Schröder as a person and especially in the office of the Federal Foreign Minister. Likewise, Federal President Lübke was not ready to appoint Schröder as Foreign Minister. The objection of the then State Secretary in the Foreign Office, Karl Carstens , that the Federal President was not entitled to reject individual ministers, caused Lübke's resistance to be abandoned. Lübke was taken against him by Schröder's statements on the Berlin question and the building of the Wall.

Nevertheless, a small Catholic group in the Union faction around Karl Theodor zu Guttenberg , Bruno Heck and Heinrich Krone tried to prevent Heinrich von Brentano from retiring from office, to change the Chancellor's mind and to pave the way for a grand coalition with the Social Democrats. Adenauer stuck to his decisions and Schröder became the new Federal Foreign Minister on November 14, 1961, with Federal President Lübke Schroeder's certificate of appointment demonstratively being the last to sign.

Schröder was considered the winner of the new government formation, as he received the most important office alongside the Federal Chancellor and was thus able to positively stage himself for his further career.

Taking office

With Karl Carstens and Rolf Lahr, Schröder had two state secretaries in office, with whom he quickly harmonized and whose opinions were very important to him. This harmony was probably also promoted by the fact that all three were North Germans and Protestants.

The leadership style in the ministry changed significantly when Schröder took office. Lower experts with official rank were also involved in the decisions and the foreign policy decisions of Schröder's closest staff were sometimes also communicated to his secretaries so that these other ministries could respond competently to questions. In addition, the heads of department held a morning meeting every day, mostly chaired by the state secretaries, to assess current foreign policy events.

Schröder operated an open personnel policy that was based on performance and competence and not on the applicant's party book. In this way, lower ranks could also send critical memoranda to him and did not need to fear that this would damage their official career. Schröder's cool aloofness deterred many officials, who they often mistook for arrogance, and many discussions with him ended in asserting Schröder's opinion, as he was often better at mastering the issues than the specialist officials. In order to improve the flexibility of the Foreign Office's decisions, he was the first minister to introduce a planning staff.

The relationship with the USA under Adenauer

In the course of the Berlin crisis and the building of the Berlin Wall, Schröder's first business trip as Foreign Minister took him to Washington as Adenauer's companion. Unlike Adenauer, he placed more trust in the US tactics of negotiating with the Soviet Union and its satellite states than the Federal Chancellor. With his American counterpart Dean Rusk , he quickly formed a good friendship that was based on mutual respect.

This fact, combined with the USA's first offers of negotiation to Moscow, prompted Adenauer, Gerhard Schröder and his two state secretaries, as well as Adenauer's intimate partner, to quote Hans Globke to Cadenabbia , where he traditionally took summer vacation. There, Schröder had to withdraw his first diplomatic concession on the American side and bow to the guideline competence of the then 85-year-old Chancellor.

Nonetheless, Schröder hoped that the Federal Republic would continue to have a say in NATO's defense policy, especially with regard to the European allies and their quarrels with the USA at the time. Above all, he hoped that the Federal Republic would also have influence on the alliance's nuclear defense measures , because West Germany had no nuclear weapons, but was the strongest NATO member in Europe compared to the nominal strength of its army.

In the negotiations on the test freeze agreement , Schröder rejoined the opinion of the Kennedy administration and started negotiating. Adenauer brought almost the entire federal cabinet behind him, tried to prevent ratification of the agreement by the GDR as well, leaned closely on France, which has not ratified this agreement to date. In the end, the rift between the Federal Chancellor and the Foreign Minister could hardly be repaired and the conflict between the Atlanticists and Gaullists in the CDU took on worrying forms. Schröder then successfully campaigned for Germany to join the agreement with the support of the SPD and FDP.

Relations with France under Adenauer

There was no friendship with his French counterpart Maurice Couve de Murville , and neither was there a friendly tone with the French President Charles de Gaulle . Schröder considered the French policy of the time for the Federal Republic and the EEC to be negative, as he found no elements of integration in it. Schröder understood the European unification and also the Franco-German reconciliation as a complementary policy to the alliance policy within the framework of NATO and the leadership of the USA. For this reason, he also pleaded in the Federal Cabinet for the admission of Great Britain to the EEC in order to have a counterweight to France. This policy provoked protests from Adenauer and he sent him a letter via Globke that was supposed to tie Schröder to the Federal Chancellor's authority to issue guidelines. The indirect attempt to provoke Schröder to resign, however, failed.

Great Britain was moving closer to the USA again at this time, as it was dependent on American aid for delivery systems for atomic warheads after the USA had stopped manufacturing the promised AGM-48 Skybolt without consulting London. This turn on the part of Great Britain provoked de Gaulle so much that he proposed a bilateral treaty to Adenauer. Adenauer seized this opportunity, which culminated on January 23, 1963 in the Élysée Treaty , which Schröder also had to sign. After the signing, Adenauer received a hug and a kiss from de Gaulle, both of which de Gaulle Schröder refused.

The resulting French rejection of Great Britain's accession to the EEC and thus also Germany's vote in favor of France, dismayed the US administration, which had firmly expected Great Britain to join soon, in order to create a solid political and economic alliance in Western Europe to NATO, also through the EEC to create with Great Britain and thus to present the Soviet Union with a second power bloc on its western border. Schröder then sent State Secretary Carstens to Washington as a troubleshooter to calm the mood there.

The relationship to the Eastern Bloc under Adenauer

In 1955 the young Federal Republic had established diplomatic relations with the USSR. In 1966 in Geneva , Schröder also met the Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Andrejewitsch Gromyko , with whom he had little in common. At the first meeting, however, he succeeded in showing Gromyko his idea for better trade relations, even though the USSR felt threatened at that time by a possible nuclear armament in the Bundeswehr. But he also emphasized the German guideline of foreign policy that the first goal was to achieve German unity in peace.

A short time later, the Foreign Ministry was confronted with indiscretions from the German ambassador in Moscow , Hans Kroll . He had divulged the Globke plan to representatives of the press. Schröder had to threaten Adenauer with his own resignation until he finally agreed to Kroll's removal from Moscow. The fact that Kroll had high-ranking friends in Bonn, such as Heinrich Krone, Franz Josef Strauss, Erich Mende or Erich Ollenhauer , may also play a role .

Schröder was one of the few West German politicians who saw the construction of the Wall without emotion and only as an expression of the GDR leadership's helplessness to keep their people in their own country.

At the end of May 1962, Schröder gathered a small group of employees for a strategy conference in Maria Laach Abbey in order to discuss new approaches in Ostpolitik with them. Without recognizing the GDR, it was agreed that trade relations should be established with the Warsaw Pact states. Trade should lead to rapprochement and greater understanding. In June 1962 he presented his theses to the 11th CDU federal party congress in Dortmund. His program was very controversial in the CDU, especially among his strongest critics around von Guttenberg and Krone; The FDP and SPD, on the other hand, welcomed these new accents in German foreign policy. Schröder, who was always shunned by the opposition and the coalition partner as interior minister, became a trustworthy cooperation partner in the office of foreign minister. The first trading branch was opened on March 7, 1963 in Warsaw after the successful conclusion of a contract. At the end of 1964 it was possible to open commercial agencies in almost all Eastern Bloc countries with the exception of the GDR.

First possible candidate for Chancellor in 1963

Under pressure from the FDP, Adenauer had to hand over the post of Federal Chancellor to a successor from the ranks of the Union during the fourth legislative period (1961 to 1965). In the struggle for his successor, Adenauer tried to prevent his deputy Ludwig Erhard by all means. There were very unpleasant scenes on the part of the patriarch that split the CDU into two camps. For this reason, several potential opponents of Erhard crystallized out at the beginning of the legislative period, including Franz Josef Strauss, Eugen Gerstenmaier , Heinrich von Brentano, Heinrich Krone and Gerhard Schröder. In the course of the internal power struggle, Krone and Brentano declared that they were no longer ready to run against Erhard, Gerstenmaier was only to be had as Chancellor of a grand coalition, so that only Strauss and Schröder remained. The opposition between the two Union politicians grew noticeably to the point of the Spiegel affair , which put an end to Strauss' prospect for a possible candidate for chancellor. Schröder, who had almost nothing to do with the Spiegel affair, quickly distanced himself from then Defense Minister Strauss and was thus the only real competitor to Erhard's candidacy for chancellor.

The CDU member Will Rasner immediately tried to build Schröder in the Union faction as a candidate against Erhard. On March 22, 1963, the parliamentary group met and Heinrich von Brentano opened the meeting with a report that the party could not get past Ludwig Erhard. Adenauer, who wanted to prevent Erhard, did not use the opportunity to bring Schröder into play as a candidate. Perhaps that was also due to the fact that Schröder had not acted aggressively enough against the Vice Chancellor and his ambitions to become Chancellor, so that Adenauer had too little confidence in Schröder. In the end, Erhard was unspectacularly selected as the new candidate for chancellor of the Union parliamentary group.

Schröder (like Strauss) saw in Erhard at that time only a transitional chancellor who was to win the federal election in 1965 as the election campaign engine of the Union and whose successor was to be chosen as soon as possible, so that both of them put their ambitions back to the Federal Chancellery for the time being.

Schröder, like Heinrich Krone or Ernst Lemmer , avoided leaving posterity with his view of the succession dispute and the internal party conflict.

The end of Adenauer's chancellorship

Adenauer and Schröder went their separate ways more than ever in the last few months of Adenauer's office. The test-free debate was the culmination of the split. Schröder resented Adenauer for not advocating for him in the debate about the successor to Chancellor, and Adenauer resented Schröder that he continued to pursue a pro-American course and did not fulfill the Chancellor's favorite alliance with France, as Adenauer did had wished. In the last days of the Chancellor's office, Schröder briefly and partly succinctly rejected written warnings from Adenauer.

Schröder had no idea that his behavior could harm him later. Adenauer remained party chairman until March 1966 and the gray eminence of the Union until his death in April 1967.

Erhard cabinet 1963–1966

Change of Chancellor

When Ludwig Erhard took office as Federal Chancellor, little changed for Schröder, as Erhard was in no way angry with him that he had been treated as a candidate for Chancellor in between. It was also Schröder who urged Erhard to moderate himself when he increasingly demanded a change of Chancellor. Politically, Erhard was, like Schröder, an Atlanticist and supported the foreign policy efforts of his foreign minister in this direction to the best of his ability. Only Konrad Adenauer tried to reinstall Heinrich von Brentano as foreign minister, but was not heard by the party, parliamentary group, coalition partner or the new Federal Chancellor. The federal cabinet has now been almost completely taken over by Erhard except for Rainer Barzel as federal minister for all-German issues , who had to vacate his ministerial chair for the FDP party chairman and vice chancellor Erich Mende and switched to the leadership of the Union faction.

The relationship with the USA under Erhard

Shortly after the change of Chancellor, the American President Kennedy was killed in an assassination attempt in Dallas . He was succeeded by Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson . After Kennedy's funeral was over, Johnson invited Chancellor Erhard and Foreign Minister Schröder to his ranch in Texas. On a human level, the partners Johnson / Rusk and Erhard / Schröder were immediately close and both sides affirmed that they would move closer together again on political issues, at least more than was the case under Adenauer.

But after it became clear that the German-sponsored plan to set up a multilateral force (in German: multilateral (nuclear) armed force) could not be implemented after the election victory of the British Labor Party with its Prime Minister Harold Wilson in 1964 , Foreign Minister Schröder and Chancellor Erhard had to fight Arm yourself against increased pressure in your own parliamentary group, because the Gaullists in the CDU parliamentary group accused them of failure in foreign policy. Above all, however, the American President Lyndon B. Johnson, who was the driving force behind the MLF and who had not been able to bundle the interests of his NATO partners, failed above all, because his withdrawal against the background of domestic political problems left Gerhard's efforts Schröders fizzled out. At that time it was only due to the upcoming federal election in 1965 and thanks to the commitment of the Union parliamentary group leader Rainer Barzel that the parliamentary group rallied behind the government on this issue, although opinions diverged strongly.

The foreign exchange compensation for the stationing of US troops in Germany contractually expired in 1967, the costs had brought the federal budget into difficulties, as two billion marks were missing to pay. Chancellor Erhard therefore made a trip to the USA in September 1966 in order to postpone the payment. He was accompanied by foreign and defense ministers. The negotiations with US President Johnson turned out to be very negative, as he himself was under domestic political pressure, as the US involvement in Vietnam did not bring the desired success. Johnson negotiated extremely hard and did not allow the German government delegation to come forward.

Relations with France under Erhard

Relations with France did not get any new impetus with the new chancellor, like that with the USA. On the contrary, French interests now met an Anglophile chancellor, who was encouraged by his foreign minister. Erhard and Schröder were afraid that France was striving for political hegemony in Europe thanks to Germany's economic power in the background. This became evident very quickly in the negotiations on the EEC agricultural market and the GATT agreement , in which the French government wanted to break German agricultural price policy completely in its favor. When Schröder refused to give in, France refused to join the GATT treaty, which was economically important for Germany. Both could be regulated through renegotiations, but left a bad taste in both governments.

The kidnapping of Antoine Argoud from Munich to Paris led to further upset . The member of the OAS was most likely kidnapped on behalf of the French government without the Federal Republic of Germany being consulted or even informed. Schröder, as the former Federal Minister of the Interior, went too far to encroach on the sovereignty of the Federal Republic and wrote a protest note to France. At the same time, France was in the process of recognizing the People's Republic of China , again without consulting the Federal Republic, as the Franco-German treaty actually required.

Schröder's tough stance on these points was interpreted negatively by the Union faction. Not only the group of Gaullists around Adenauer, Guttenberg, Brentano and Krone tried to discredit Schröder, but also circles close to Franz Josef Strauss in the CSU. Only the French stance of blocking the empty chair policy in the EEC agricultural negotiations gave Schröder and his basic political position within the CDU a boost, since Gaullists were also disappointed with this type of almost extortionate policy.

What made Schröder personally more difficult was the fact that the Paris administration treated him extremely condescendingly on his visit on December 9, 1964. Officially, his aircraft had to be parked in a parking position away from the reception building at Orly Airport, as air traffic did not allow parking there at the time, so you would stop in front of a field. Schröder's spontaneous reaction was: “We didn't come here to dig up potatoes.” A rickety Air France bus appeared, whereupon Schröder refused to leave the plane. Only the arrival of a limousine and the persuasion of the stewardesses convinced him to get into the vehicle. This incident was extremely embarrassing for the visit of the foreign minister of a close friendly nation.

The Franco-German relationship was further dampened by de Gaulle's unilateral announcement of a partial exit from NATO on February 21, 1966. In the event of an emergency, France no longer wanted to subordinate its armed forces to the NATO Commander-in-Chief for Western Europe. The background was probably the French fear of being drawn into the Vietnam War . This unilateral action was all the more serious because, in breach of the treaty, the Federal Republic of Germany was not informed of the political step during extensive government talks that Chancellor Erhard and Schröder had held in Paris a few weeks earlier. Schröder then took an aggressive stance in negotiations and argued with the French and his own cabinet about the whereabouts of the French troops in Germany. In his opinion, due to the partial withdrawal from the defense alliance, they had fewer rights compared to the other NATO troops on German soil. However, under pressure from his own party and cabinet, Schröder did not remain tough for long and soon took a more conciliatory stance.

The historian Henning Köhler judges: "At no point in time has the Federal Republic's foreign policy been so short-sighted and one-sided as it was under Erhard and Schröder." Gaullists and Atlanticists were no alternative positions in terms of content, but only polemical labels. In truth, it was a matter of deepening and further expanding the cooperation with France that had begun in the Élysée Treaty, while recognizing the USA as a guarantor of German security. Schröder failed at this task.

The relationship to the Eastern Bloc under Erhard

Early on under Erhard's chancellorship, the then ruling mayor of Berlin, Willy Brandt, contacted the East German leadership through his intimate partner Egon Bahr in order to negotiate a pass agreement for the 1963 Christmas season for the West Berlin population. Such foreign policy arbitrariness, which bordered on recognition of the GDR, led to initial disagreements with the old and future chancellor candidate of the SPD, because the change through rapprochement was not represented by Schröder, he hoped to slowly soften the eastern dictatorships through trade.

A further rapprochement with the Eastern Bloc was on the way in 1964, when Nikita Khrushchev's son-in-law and closest advisor, Alexei Ivanovich Ajubei , arranged a state visit to Khrushchev during an unofficial visit to the Federal Republic of Germany in the same year, which, however, did not take place because of his overthrow. Ironically, Khrushchev's political decline is linked to the policy of rapprochement with the Federal Republic, which he initiated on his own initiative without consulting his Politburo .

This political orientation of Schröder towards a rapprochement with détente, as it corresponded to the US-American line, intensified the intra-party opposition between Gaullists and Atlanticists considerably. This fact was aggravated considerably by the support of this policy by the FDP and especially by the SPD. Many CDU Gaullists therefore hoped to be able to replace Schröder with one of their own after the 1965 federal election.

After winning the federal election in 1965, Schröder could remain in the office of Foreign Minister. He had a survey conducted on the German diplomats on East and détente policy. The unanimous tenor of the diplomats was that a policy of détente towards the East was only possible by abandoning the Hallstein Doctrine , because third world countries in particular were more than ready to diplomatically recognize the second German state. Wilhelm Grewe in particular , who helped develop the Hallstein Doctrine, advocated relaxing his own work. In 1966 the time had come for the federal government to send a peace note to all countries in the world with the exception of the GDR. Adenauer's “Politics of Strength” was dropped for the first time in order to send the Eastern Bloc countries an offer of talks and a peace signal. From today's perspective, this rapprochement was timid, but a sensation in the political life of the Federal Republic of that time.

His successor in office Brandt went further than Schröder in his détente efforts, but used the measures introduced by Schröder as the foundation of his Ostpolitik. Schröder pursued this path with considerable bitterness, as these steps were still denied him by his own party, but his successor in the grand coalition received permission to do so and Schröder's efforts lost their luster over time.

The relationship with Israel under Erhard

Under Adenauer, West German diplomacy began to take delicate steps towards the State of Israel . The first point, born of moral necessity, was reparation , which also made pecuniary payments to the Israeli state. With the further incorporation of the Federal Republic into NATO and thus via the USA in strategic partnership with Israel, German armaments were delivered to Israel in part at lower prices. These included the 150 main battle tanks (instead of 15 previously agreed) of the M48 type from German license production , as required by US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara . The arms deal should be kept secret under all circumstances so as not to deter or even provoke the Arab states, including Egypt . Despite Schröder's veto, which was very critical of the Israeli arms business from the outset, the tank business was wound up and came through indiscretions to the press and thus to the public.

Almost at the same time, the Egyptian head of state Nasser received the GDR head of state Walter Ulbricht as a state guest in Cairo and Alexandria , which amounted to a factual recognition of the GDR and thus a breach of the Hallstein doctrine . Although Israel had little economic contact with the Federal Republic compared to its Arab neighbors, Chancellor Erhard decided to establish diplomatic relations with Israel against the advice of Schröder and his ministry. Schröder feared that this step would result in the severance of many diplomatic relations with the Arab world and that these states would turn to the GDR as a German alternative; that would have meant that the GDR would inevitably have gained international reputation and influence. Schröder therefore continued to stick to the non-recognition of the GDR, because he expected this step of recognition to drop a possible reunification of Germany.

First health problems

Gerhard Schröder's health had never been seriously threatened in the previous years, but his sister Marie-Renate, a human medicine specialist, discovered in the early 1960s that her brother had a worsening, considerable and uncontrollable cardiac arrhythmia . At the beginning of October 1964, Schröder therefore underwent an operation to implant a pacemaker . Due to the recovery process, he was out for five weeks, but was kept informed about the political progress. Most of this time he spent on the Bühlerhöhe .

In April 1965 Schröder had to undergo a cure again because of his heart problems, for which he chose the idyll at Tegernsee in Bavaria . He also used the time to settle the differences that had arisen with Chancellor Erhard over the government's Israel policy in private talks, because Erhard lived privately on Lake Tegernsee.

The formation of the government in 1965

Despite the overwhelming victory of the Union, which narrowly missed an absolute parliamentary majority, the formation of a government was very tough, because the FDP had to accept noticeable losses in the election, the CSU and its policy had been enormously confirmed with over 55 percent of the Bavarian electorate the tug-of-war over the occupation of the Foreign Ministry paralyzed negotiations. Schröder absolutely wanted to remain Foreign Minister of the Federal Republic and took the offensive in the limelight at an early stage of the negotiations. After the Federal Chancellor wanted to hold on to him, the Gaullist circles around Adenauer, Krone, zu Guttenberg and Strauss did everything in their power to discredit Schröder. They did not shy away from calling Federal President Lübke unsuitable for their own cause, pointing to Schröder's private life and his affair in Paris. Ultimately, all of these attempts were in vain, as Schröder was too well secured by the EAK, the confidence of the Federal Chancellor and his first vote result in the constituency. Again, the Federal President had to reluctantly appoint a Foreign Minister Schröder.

The end of Erhard's chancellorship in 1966

Due to the failure of negotiations on the stationing costs of the US troops, Chancellor Erhard was forced to rehabilitate the federal budget through tax increases. The federal ministers of the FDP then submitted their resignation, so that Erhard no longer had a majority in the Bundestag. The legally non-binding request for a vote of confidence by the SPD parliamentary group on November 8, 1966, which had been passed with the votes of the FDP, compelled the party executive committee at its meeting on the same day to suggest that Erhard resign. Unlike some of the CDU cabinet colleagues, Schröder remained loyal to Ludwig Erhard until the end.

Second possible candidate for Chancellor in 1966

At the party executive committee meeting on November 8, 1966, the Prime Minister of Rhineland-Palatinate Helmut Kohl proposed several members of this body to be candidates for the parliamentary vote on the candidate for chancellor. They were Eugen Gerstenmaier, Kurt Georg Kiesinger, Rainer Barzel and Gerhard Schröder. All but Gerstenmaier declared their willingness to put themselves to the vote, Gerstenmaier did not want to run against Kiesinger and recommended voting for him.

In the internal vote of the CDU / CSU parliamentary group on their candidate for chancellor, Schröder was defeated by Kiesinger in the third ballot with 81 to 137 votes (with 26 votes for Rainer Barzel ). The Atlantic-Gaullist dispute had resulted in strong tensions in the Union, which were partly responsible for his defeat in the Union parliamentary group's vote for candidate for chancellor. Franz Josef Strauss denied the Protestant Schröder support for the decisive votes of the CSU in the joint parliamentary group. It was just as negative for him that Rainer Barzel also came from the North Rhine-Westphalian state association and thus also withdrew votes from Schröder. Nevertheless, without the CSU votes, Schröder was the candidate with the most votes internally in the CDU parliamentary group, so that Kiesinger had to offer Schröder a ministerial post when the government was formed. Schröder was now the longest serving minister in the current federal government.

Federal Minister of Defense 1966–1969

Taking office

When the SPD claimed the office of Foreign Minister for its chairman Willy Brandt when the Grand Coalition was formed, Schröder became Federal Minister of Defense in the Kiesinger cabinet on December 1, 1966 . Kiesinger would have gladly done without Schröder at the cabinet table, but had to consider him with another office, since Schröder's position in the CDU was still very strong. Schröder himself saw this as a descent towards the Foreign Ministry.

Schröder took a few loyal employees with him to the Federal Ministry of Defense, above all his secretary Mrs. Naphus and his state secretary Carstens. He left the General Inspector of the Bundeswehr Ulrich de Maizière in office and quickly harmonized with him. More difficult for him was the relatively quick departure of Carstens to Kiesinger as his head of the chancellery. Carstens' successor was the former federal press spokesman and active reserve officer Karl-Günther von Hase .

Administration

During his tenure, several important defense policy decisions were made, including the high rate of crashes in the Starfighter fleet , which is mainly thanks to Johannes Steinhoff as the Air Force Inspector . In addition, in consultation with his British counterpart Denis Healy von Schröder, the foundation stone was laid for a European fighter aircraft project that would later lead to the tornado . As defense minister, Schröder was also anxious that the project of a joint coordination of nuclear weapons of the NATO alliance was resumed after the multilateral force had failed. Therefore, he supported the establishment of the nuclear planning group .

The tense relationship with Kiesinger

In the situation at that time, Schröder saw himself as reserve chancellor of the CDU in the event of the failure of the grand coalition, which he gave little chance of success. Kiesinger's reserved attitude towards Schröder was also shown by the fact that the Chancellor very often invited the decision-makers of the coalition to his holiday resort Kressbronn on Lake Constance in order to better mediate between the groups, but Schröder was only invited once and thus less than any other Federal Minister.

The Bundeswehr would have had to accept the greatest financial cuts in the draft budget of the new Finance Minister Strauss, which Schröder openly opposed. Kiesinger responded by consulting the retired Generals Speidel and Heusinger , who criticized Schröder and his Inspector General and accepted the cuts made by the Ministry of Finance.

An uproar arose when the Parliamentary Secretary of State in the Chancellery zu Guttenberg the inspector of the army Josef Moll to talk with the Registrar invited to inform without Schroeder as a minister. Schröder then threatened to resign. Ultimately it was decided that such consultations with the head of government should only take place with the assistance of the minister.

When the emergency laws were introduced , Schröder was the only cabinet member who voted against it, because the government drafts did not go far enough for him and he stuck to his drafts as Federal Minister of the Interior.

Other health problems

On August 29, 1967, he fell on the stairs of his Atterdag holiday home on Sylt due to cardiac arrhythmias and clouding of consciousness and was flown by rescue helicopter to the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf . Schröder never fully recovered from it, his memory often left him, and his voice has remained sluggish ever since. Furthermore, his state of health became increasingly a political issue when he was proposed for higher offices and his opponents pointed out his poor health.

Candidate for the Federal Presidency in 1969

In the run-up to the federal presidential election in 1969 , Schröder was seen as a suitable candidate for the Union parties. In the CDU, however, resistance arose from Kiesinger and other opponents of Schröder, who also brought Richard von Weizsäcker , who was then still rather unknown, into play via Helmut Kohl . In the decisive internal party vote, Schröder clearly prevailed against his rival with 65 to 20 votes. The SPD nominated his cabinet colleague in the Justice Ministry Gustav Heinemann . This caused a certain polarization, as a former member of the Confessing Church , thus a proven opponent of the Nazi dictatorship, and, what was again brought into the public eye, a former member of the NSDAP and the SA faced each other.

In the months leading up to the election, both Heinemann and Schröder attempted to win over the FDP, which was then in opposition at the federal level and whose votes would most likely be important. On the morning of election day, the FDP chairman, Walter Scheel, informed Schröder that the FDP would vote for a majority of Heinemann.

In the election itself, Schröder was defeated by Heinemann in the third ballot with 506 to 512 votes. He was probably also elected by 22 members of the Federal Assembly who had been sent by the NPD , some votes for him may also have been cast by the FDP. With this result, the loss of power for the Union parties ruling since 1949 and a new majority for a social-liberal coalition became apparent.

Cabinets

- Cabinet Adenauer II - Adenauer III - Adenauer IV - Adenauer V

- Cabinet Erhard I - Erhard II

- Kiesinger cabinet

After active politics 1980–1989

In the years after his active political activity, Schröder maintained a private discussion group of former politicians, diplomats and economic functionaries who philosophized about the global problems of the new era, but no longer intervened politically in day-to-day business. In this circle he thought the Reagan administration's policies were good, as he believed the West was showing strength again, and he supported the SDI program .

His last appearance in the Bundestag was on June 17, 1984, when he gave the speech at the memorial event on June 17, 1953 .

Schröder died on December 31, 1989 in his house on Sylt. After his death, the German Bundestag honored him on January 12, 1990 with a state ceremony in the plenary hall . Gerhard Schröder was buried in the cemetery of the island church St. Severin in Keitum on Sylt.

Private

Schröder had a Prussian upbringing and kept a cool distance from most people. Until he left the Bundestag in 1980, he did not speak to any member of the CDU / CSU parliamentary group.

In 1960, Schröder built a holiday home for himself on the North Sea island of Sylt in the village of Kampen in Südwestheide, which he called Atterdag . Atterdag is Danish and means “new day”, but was also the nickname of the Danish king Waldemar IV. Here he maintained close relationships with influential people in society and the economy, such as Berthold Beitz . On Sylt, Schröder also got to know the painter Albert Aereboe , who lived and worked there and by whom he had himself portrayed. Aereboe sparked his interest in modern art .

Schröder was honorary president of the German Society for Photography .

Relationship with the press

The initially good relationship with the publisher Rudolf Augstein was hopelessly shattered by a negative article in the Spiegel about Schröder as Minister of the Interior, although Augstein saw Schröder as a potential candidate for Chancellor in the early years. He was never able to develop a good relationship with the head of the Springer publishing house, Axel Springer , at times he was severely attacked in the Bild newspaper , such as on March 23, 1965 with the headline Minister Schröder - the loser of the year . Today it is assumed that Springer was an opponent of Schröder's Berlin policy, was closer to the Gaullist forces in the CDU / CSU and also disagreed with Schröder's Israel policy, because friendship with Israel was at the core of Springer Verlag's orientation .

Awards (excerpt)

- 1934 SA sports badge

- 1942 Iron Cross 2nd class

- 1942 black wound badge

- 1942 Medal Winter Battle in the East 1941/42

- 1942 Cholmschild

- 1962 Large gold medal on ribbon for services to the Republic of Austria

- 1965 Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic together with Willy Brandt

- 1966 Grand Cross of the Order de Isabel la Católica

Trivia

On October 10, 1987 there was to be an interview on WDR 2 with the then SPD opposition leader of the Lower Saxony state parliament, Gerhard Schröder , about the collapsed red-green coalition in Hesse . Due to a mistake, the moderators did not get the SPD politician connected by phone, but Gerhard Schröder from the CDU, who was just as irritated as the moderators. The broadcast could still be saved because Gerhard Schröder was able to present his view of things on this topic.

See also

- Cabinet Adenauer II - Cabinet Adenauer III - Cabinet Adenauer IV - Cabinet Adenauer V - Cabinet Erhard I - Cabinet Erhard II - Cabinet Kiesinger

Publications

- For or against the constructive vote of no confidence. In: Bonner Hefte. 1953, No. 1, pp. 22-26.

- We need an ideal world. Econ, Düsseldorf / Vienna 1963.

- The plane was called "Westward Ho". In: Horst Ferdinand (ed.): Beginning in Bonn. Memories of the first German Bundestag. Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 1985, ISBN 3-451-08235-7 , pp. 139-144.

literature

- Walter Henkels : 99 Bonn heads , reviewed and supplemented edition, Fischer-Bücherei, Frankfurt am Main 1965, p. 226ff.

- Rainer Barzel : A daring life. Memories. Hohenheim, Stuttgart / Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-89850-041-1 .

- Rainer Barzel: In dispute and controversial. Comments on Adenauer, Erhard and the Eastern Treaties. Ullstein, Frankfurt a. M. 1986, ISBN 3-550-06409-8 .

- Franz Eibl: Politics of Movement. Gerhard Schröder as Foreign Minister 1961–1966. (= Studies on Contemporary History. Vol. 60). Oldenbourg, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-486-56550-8 .

- Review by Stefan Gänzle, in: Portal for Political Science . January 1, 2006.

- Daniel Koerfer: Fight for the Chancellery. Erhard and Adenauer. Ullstein, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-548-26533-2 .

- Torsten Oppelland: Gerhard Schröder (1910–1989). Politics between state, party and denomination. Droste, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-7700-1887-7 .

- Review by Bernhard Löffler . In: see points . 3rd year, No. 6, June 15, 2003.

- Review by Martin Menke. In: H-Net Reviews. March 2004.

- Torsten Oppelland: Schröder, Gerhard. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 23, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-428-11204-3 , p. 562 f. ( Digitized version ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Gerhard Schröder in the catalog of the German National Library

- Stefan Marx, Wolfgang Tischner: Schröder, Gerhard. In: KAS.de , history of the CDU .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung , accessed on August 17, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d e receipt available . In: Der Spiegel . No. 9 , 1969, p. 36 ( online - February 24, 1969 , accessed October 30, 2011).

- ↑ BT-Drs. 17/8134 of December 14, 2011: The Federal Government's response to the major question from the Die Linke ea .: "Dealing with the Nazi past"

- ↑ a b Schreiber, Hermann: A king's child on the move . In: Der Spiegel . No. 31 , 1972, p. 22-23 ( Online - July 24, 1972 , accessed on 30 October 2011).

- ↑ BVerfG, February 28, 1961, 2 BvG 1, 2/60, BVerfGE 12, 205 <215>.

- ↑ a b Gerhard Schröder's lonely fight . In: Der Spiegel . No. 4 , 1965, pp. 20 ( Online - Jan. 20, 1965 , accessed on March 6, 2012).

- ^ Henning Köhler: Germany on the way to itself. A history of the century . Hohenheim-Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, p. 566.

- ^ Die Zeit , accessed on August 17, 2011.

- ↑ Gerhard Schröder . In: Der Spiegel . No. 2 , 1990, p. 67 ( online - January 8, 1990 , accessed October 30, 2011).

- ↑ Drank whiskey . In: Der Spiegel . No. 20 , 1969, p. 34 ( online - May 12, 1969 , accessed October 30, 2011).

- ↑ scene changed . In: Der Spiegel . No. 37 , 1967, p. 24-25 ( online - 4 September 1967 , accessed on 30 October 2011).

- ↑ Gerhard Schröder . In: Der Spiegel . No. 49 , 1960, pp. 94 ( online - November 30, 1960 , accessed October 30, 2011).

- ↑ List of all decorations awarded by the Federal President for services to the Republic of Austria from 1952 (PDF; 6.9 MB)

- Torsten Oppelland: Gerhard Schröder (1910–1989). Politics between state, party and denomination. Droste, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-7700-1887-7 .

- ↑ p. 38.

- ↑ pp. 51-53.

- ↑ pp. 56-63.

- ↑ pp. 91-92.

- ↑ pp. 102-103.

- ↑ pp. 106, 110-111, 129.

- ↑ p. 112.

- ↑ p. 116.

- ↑ p. 119.

- ↑ p. 120.

- ↑ p. 123.

- ↑ p. 126.

- ↑ p. 121.

- ↑ p. 124.

- ↑ p. 130.

- ↑ pp. 131-141.

- ↑ pp. 150-151.

- ↑ pp. 154-157.

- ↑ pp. 163-172.

- ↑ p. 168.

- ↑ pp. 83-87.

- ↑ p. 92.

- ↑ p. 122.

- ↑ pp. 180-181.

- ↑ p. 238.

- ↑ p. 689.

- ↑ p. 716.

- ↑ pp. 719-724.

- ↑ pp. 382-401.

- ↑ p. 365.

- ↑ p. 736.

- ↑ pp. 401-404.

- ↑ p. 407.

- ↑ pp. 207-225.

- ↑ pp. 228-235.

- ↑ p. 339.

- ↑ p. 224.

- ↑ pp. 244-246.

- ↑ p. 716.

- ↑ pp. 731-732.

- ↑ p. 685.

- ↑ p. 728.

- ↑ p. 735.

- ↑ p. 730.

- ↑ p. 685.

- ↑ pp. 734-735.

- ↑ pp. 183-184.

- ↑ p. 187.

- ↑ p. 238.

- ↑ p. 254.

- ↑ pp. 714-715.

- ↑ pp. 733-736.

- ↑ pp. 735-736.

- ↑ pp. 255-258.

- ↑ pp. 275-276.

- ↑ pp. 279-282.

- ↑ pp. 284-288.

- ↑ pp. 292-298.

- ↑ pp. 304-309.

- ↑ pp. 315-316.

- ↑ pp. 340-346.

- ↑ p. 351.

- ↑ p. 360.

- ↑ pp. 352-354.

- ↑ p. 360.

- ↑ pp. 365-366.

- ↑ pp. 370-379.

- ↑ p. 335.

- ↑ pp. 312-315.

- ↑ pp. 430-434.

- ↑ p. 435.

- ↑ pp. 435-437.

- ↑ pp. 43-442.

- ↑ pp. 444-454.

- ↑ pp. 518-522.

- ↑ pp. 526-522.

- ↑ pp. 459-465.

- ↑ pp. 485-489.

- ↑ pp. 490-502.

- ↑ pp. 502-506.

- ↑ pp. 466-471.

- ↑ pp. 510-511.

- ↑ pp. 476-485.

- ↑ pp. 523-525.

- ↑ p. 588.

- ↑ pp. 506-518.

- ↑ p. 568.

- ↑ pp. 539-542.

- ↑ pp. 545-547.

- ↑ pp. 555-560.

- ↑ S. 592-608.

- ↑ pp. 673-677.

- ↑ pp. 549-555.

- ↑ pp. 564-567.

- ↑ p. 567.

- ↑ pp. 571-572.

- ↑ pp. 627-638.

- ↑ pp. 662-671.

- ↑ pp. 552-558.

- ↑ S. 591-592.

- ↑ pp. 627-638.

- ↑ pp. 657-662.

- ↑ p. 695.

- ↑ pp. 609-627.

- ↑ pp. 593-596.

- ↑ p. 639.

- ↑ pp. 642-656.

- ↑ p. 677.

- ↑ pp. 677-684.

- ↑ p. 686.

- ↑ pp. 686-687.

- ↑ p. 703.

- ↑ p. 700.

- ↑ p. 698.

- ↑ pp. 688-689.

- ↑ pp. 690-698.

- ↑ p. 744.

- ↑ pp. 695-698.

- ↑ p. 736.

- ↑ p. 741.

- ↑ p. 738.

- ↑ p. 417.

- ↑ p. 418.

- ↑ pp. 638-639.

- ↑ p. 103.

- ↑ p. 123.

- ↑ p. 123.

- ↑ p. 123.

- ↑ p. 123.

- ↑ p. 7.

- Daniel Koerfer: Fight for the Chancellery. Erhard and Adenauer. Ullstein, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-548-26533-2 .

- Rainer Barzel: In dispute and controversial. Comments on Adenauer, Erhard and the Eastern Treaties. Ullstein Verlag, Frankfurt / M. 1986, ISBN 3-550-06409-8 .

- Rainer Barzel: A daring life. Memories. Hohenheim Verlag, Stuttgart and Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-89850-041-1 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schröder, Gerhard |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German politician (CDU), Member of the Bundestag |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 11, 1910 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Saarbrücken |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 31, 1989 |

| Place of death | Kampen on Sylt |