Black-figure vase painting

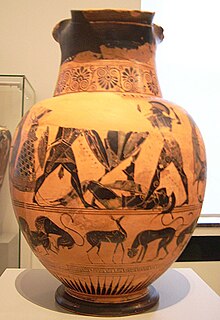

The Black-Figure Ceramics (also Black-figure style or Black- ceramic ) is one of the main techniques and styles of the ancient Greek vase painting . It was particularly widespread between the seventh and fifth centuries BC. BC, with the last offshoots up to the second century BC. To date. It differs stylistically from the previous orientalizing period and the subsequent red-figure style .

The figures and ornaments were painted on the vase body in terms of design and color in a shape reminiscent of silhouettes . The fine contours were scratched into these paintings before the fire . Details could be supported and emphasized with opaque colors, mostly white and red. The main centers of the style were initially the commercial center of Corinth and later Athens . Other important production facilities are known from Laconia , Boeotia , Eastern Greece and Italy. In Italy in particular, special styles emerged that were at least partially intended for the Etruscan market. The Etruscans were very fond of the Greek black-figure vases, as can be seen from the numerous imports. Greek artists created custom-made products for the Etruscan market that differ in shape and decor from the usual products. The Etruscans also developed their own black-figure ceramic industry, which was based on Greek factories.

The black-figure vase painting was the first art style that produced artistic personalities on a larger scale. Some are known by their real names, others are used in research under makeshift names ( emergency names ). Above all, Attica was home to numerous well-known artists. Some potters introduced various innovations that often influenced the work of the painters or were influenced by them themselves. Like the red-figure vases, those of the black-figure style are also one of the most important sources for mythology and iconography and, in part, for research into everyday life in ancient Greece . The vases have been intensively researched since the 19th century at the latest.

Manufacturing technology

The basis of vase painting is the image carrier , i.e. the vase on which the image was applied. Popular forms changed like fads. While some returned in phases, others were replaced by new ones over time. What they all had in common was the method of manufacture. After the vase was made, it was first dried. Workshop managers were the potters who, as the owners of the shops, held a high position in society.

It is unclear to what extent potters and painters were identical. It is likely that during the production period the master potters themselves did the main job as painters, with other vase painters being employed. Reconstructing the connection between potter and painter is difficult, however. In many cases, such as Tleson and the Tleson Painter , Amasis and the Amasis Painter or Nikosthenes and the Painter N , unambiguous attributions are not possible, although a significant part of the research often assumes the identity of painter and potter. However, such ascriptions can only be made if both the potter and the vase painter have signed a vessel .

The painters, who could either be slaves or hired craftsmen as pottery painters, worked on the still unfired, leather-hard vases. In the black-figure technique, the painters applied the motifs to the image carrier with clay slip ( gloss , also known as varnish in older literature ), which became black due to the fire. This was not a "color" in the traditional sense, as the paint slip was made of the same material as the clay of the vessel and only differed in particle size. First of all, all motifs were applied to the surface with a brush-like instrument. The internal structure and the representation of the subtleties were carved out of the slip by scratching , so that the clay ground could be seen through the scratches. For further detailed drawings, the artists often used two other earth colors - red and white for ornaments, garments or parts of garments, hair, animal manes, details of weapons and other equipment. They also often used white to depict women's skin. The success of the work could only be judged after a complicated three-phase fire. Only then did the red color of the vessel clay and the black of the applied clay slip emerge.

Even if the incisions are one of the main features of the style, some works dispensed with them. Their shape is technically reminiscent of the orientalizing style , but the repertoire of images no longer corresponds to the orientalizing habits.

development

The development of black-figure vase painting can only be described in terms of the individual regional styles and schools. Starting from Corinth, the production of the individual regions differed in principle despite mutual influence. Above all, although not exclusively, in Attica the best and most influential artists of their time shaped the vase painting of the Greek world. The further development of the vessels as image carriers and their quality are the main aspects of this section.

Corinth

The black-figure technique was used around 700 BC. Developed in Corinth and in the early seventh century BC. First used by Proto-Corinthian vase painters . These still belonged to the phase of the orientalizing style. The new technology was based on engraved metalwork, as figuratively painted vases were probably only a substitute for the higher-quality metal dishes. Before the end of the century, a pure black-figure style developed. Most of the orientalizing elements were abandoned, with the exception of blob rosettes (here the rosettes were formed from small individual points), and ornaments were dispensed with.

The clay used in Corinth is soft and has a yellowish, sometimes greenish hue. Bad fires were the order of the day when the complicated combustion process did not work as desired. The result was often an unwanted discoloration of the whole vase or parts of it. After firing, the glossy shade appeared matt black on the vases. The additional colors white and red were first used in Corinth and then used abundantly. The painted vessels are generally small, rarely higher than 30 cm. Most often, anointing oil vessels ( alabastrons , aryballoi ), pyxids , craters , oinochoes and bowls were painted. Plastic vessels were also often used. In contrast to the Attic vases, inscriptions are rare, painter's signatures even more rare. Most of the vessels made in Corinth and preserved today were found in Etruria , Lower Italy and Sicily; in the seventh and first half of the sixth century BC Chr. Dominated Corinthian vase painting the Mediterranean market for ceramic. It is not easy to grasp a stylistic sequence of Corinthian vase painting. It is particularly problematic that, unlike in Attic painting, for example, the proportions of the picture carriers developed only a little. Dating the Corinthian vases is also often difficult; in many cases one has to rely on secondary dates such as the founding of Greek colonies in Italy. On the basis of such information, and based on stylistic comparisons, an approximate chronology can be established, which, however, only rarely comes close to the same accuracy as the dating of the Attic vases.

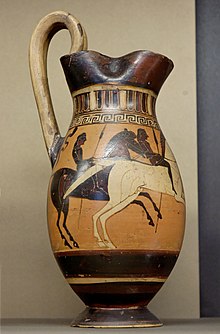

Mythological scenes are often depicted, including Heracles and figures from the Trojan saga . However, the pictorial language of Corinthian vases is thematically not as varied as the later works of Attic painters. Gods were drawn comparatively rarely, Dionysus is completely absent. The Theban sagas , on the other hand, were more popular in Corinth than later in Athens. Representations from everyday life mainly include combat depictions, riders and the revelation scenes that first appeared in the early Corinthian period. Sports pictures are very rare. The big-belly dancers , which are still controversial in their interpretation, are singular . These are carousing figures whose stomach and buttocks are stuffed with pillows. They may be related to pre-forms of Greek comedy .

Transition style

The transition style (640–625 BC) led from the orientalizing (Proto-Corinthian) to the black-figure style. The old animal frieze style of the Proto-Corinthian period had been exhausted, as had the vase painters' interest in mythical images. During this time animals and hybrids predominate. The dominant form of the time were spherical aryballoi, which were produced in large numbers and decorated with animal friezes or scenes from everyday life. The quality of the pictures is declining compared to the orientalizing period. The most prominent artists of the time were the Shambling Bull painter , whose best-known work is an aryballos with a hunting scene, the painter from Palermo 489 and his pupil, the Columbus painter . The latter's handwriting can be seen particularly well in his pictures with powerful lions. In addition to the aryballos, the kotyle and the alabastron are the most important vase shapes. Cotyls were decorated with ornaments on the edge, the rest of the decoration consisted of animals and rays. The two vertical vase surfaces are often provided with images of myths. The alabastras were generally painted with individual figures.

Early Corinthian and Middle Corinthian

The most important early Corinthian (625–600 BC) painter was the duel painter . He depicted battle scenes on Aryballoi. Since the Middle Corinthian period (600-575 BC), opaque colors were used more and more often to emphasize details. Figures were additionally painted with a number of white dots. The aryballoi were now larger and given a flat base. Worth mentioning is the Pholoe Painter , whose best-known work is a Skyphos with an image of Heracles. Although other painters had already given up this tradition, the Dodwell painter continued to paint animal friezes. His creative time extended into the late Corinthian period, and his influence on later Corinthian vase painting should not be underestimated. Also of greater importance was the main master of the Gorgoneion group and the one around 580 BC. Active cavalcade painter who was named because of his preference for riders on interior bowls. Two of his masterpieces are considered to be a bowl depicting the Ajax's suicide and a column crater depicting a wedding couple in a carriage. All figures are marked on the bowl by inscriptions. The first artist known by name is the polychrome vase painter Timonidas , who signed a bottle and a pinax . A second stage name, that of Milonidas , also appears on a Pinax. The Corinthian Olpe was replaced by Oinochoen in Attic form with a cloverleaf mouth. In the Middle Corinthian period, the representation of people increased again. The Eurytios crater from around 600 BC is considered particularly successful . BC, which shows a symposium with Heracles, Eurytius and other mythical characters in the main frieze .

Late Corinthian

In the late Corinthian period (also Late Corinthian I ; 575-550 BC) the Corinthian vases were provided with a reddish coating. This should increase the contrast between the white color used over a large area and the rather pale tone ground. The Corinthian craftsmen thus entered into competition with the Attic pottery painters, who had meanwhile taken over the dominant position in the ceramic trade. Attic vase shapes were also increasingly copied. Oinochoen, which until then had changed their form little, were now based on Attic forms; also lekythoi produced increased. The Colonettenkrater, a Corinthian invention, which was therefore called Korinthios in the rest of Greece , was varied. The Chalcidian crater was created by shortening the volute above the handles . It was decorated in the main field with various representations from everyday life as well as from mythology, the side frieze consisted of an animal frieze. The back often showed two large painted animals. Bowls became deeper in Middle Corinthian times and continued this development. They were now as popular as cotyledons. Some of them are painted with mythological scenes on the outside and Gorgon grimaces on the inside . This form of painting was also adopted by Attic painters. For their part, Corinthian painters from Athens adopted framed picture fields. Animal friezes became less and less important. During this time, the third Corinthian painter known by name, Chares , was active. The Tydeus Painter should also be mentioned, who lived around 560 BC. Chr. Gladly painted red-ground neck amphorae . Incised rosettes were still used on vases, they are only missing on a few craters and bowls. The amphiaraos crater is the outstanding work of art of the time . Around 560 BC Colonette craters created in BC is the main work of the Amphiaraos painter and shows several incidents from the life of the hero Amphiaraos .

Around 550 BC The manufacture of figured vases largely ended. The subsequent style, Late Corinthian II , is characterized by vessels painted only ornamentally and mostly in silhouette technique . This was followed by the red-figure style, which, however, did not achieve particularly high quality in Corinth.

Attica

With more than 20,000 surviving pieces, the Attic black-figure vases are the largest and at the same time the most important traditional vase complex after the Attic red-figure vases. The Attic potters benefited from the good, very ferrous clay found in Attica. High-quality Attic black-figure vases have an even, glossy and deep black coating, the color-intensive terracotta-colored clay background is finely smoothed. The skin of women was generally identified by a white overcoat. In addition, this color is also common in other details, such as individual horses, robes or ornaments. The most outstanding artists of Attica elevated vase painting to a graphic art, but goods of medium quality and series goods were also produced on a large scale. Since the silhouette-like style was of limited expressiveness, a formulaic visual language developed. The outstanding importance of the Attic vases lies in their seemingly endless repertoire of images from various subject areas. Above all for myth, but also for everyday culture, they provide rich evidence. On the other hand, images with current references are almost entirely missing. Such references only occasionally come into play through inscriptions, for example when favorite inscriptions have been painted on. On the one hand, the vases were intended for the domestic market, where they were important for celebrations or in connection with cult activities. On the other hand, they were also an important export good that was sold throughout the Mediterranean region. This is why most of the vases come from Etruscan necropolises .

Pioneers

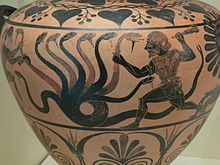

The first use of the black-figure technique falls in the time of Protoattic vase painting in the middle of the 7th century BC. Under the influence of the highest quality ceramics from Corinth at that time, the Attic vase painters changed from around 635 BC. Until the end of the century to the new technology. Initially, they were strongly based on the methods and motifs of the Corinthian models. It starts with the painter from Berlin A 34 , who is known as the first individual artist. The first artist with an individually understandable style was the Nessos painter . With the Nessos amphora, he created the first outstanding piece of the Attic black-figure style. He was also an early master of the animal frieze style in Attica. One of his vases was also the first known Attic vase to be exported to Etruria. He also made the first depictions of harpies and sirens in Attic art. Unlike the Corinthian vase painters, the Nessos painter used double and even triple incised lines to better show the parts of the animal anatomy. The double-incised shoulder line was to become a characteristic feature of the Attic vases. The possibilities of large vases, such as the abdominal amphora , as image carriers were recognized early on. Other important painters of the pioneering days were the Piraeus painter , the Bellerophon painter and the lion painter .

Early Attic vases

Around the year 600 BC The black-figure style had prevailed in Athens. The horse head amphora was an early in-house development by the Athenians . It got its name because of the horses' heads that were shown in a picture window. The development of the picture window was used frequently in the following period and was later received in Corinth itself. The Kerameikos painter and the Gorgon painter came from the area around the horse head amphorae . The orientation towards Corinth was not only retained, but intensified. The animal frieze was recognized as generally binding and mostly used. This had not only stylistic but also economic reasons. Because Athens was now competing with Corinth for sales markets. Attic vases were sold in the Black Sea area, Libya, Syria, southern Italy and Spain as well as within the Greek mainland.

In addition to the Corinthian orientation, the Athenian vases also showed their own developments. So at the beginning of the 6th century BC The lekythos of the "Deianeira type", an elongated, oval shape. The most important painter of the early period was the Gorgon painter (600-580 BC). He was a very productive artist who rarely shows mythological images or human figures and always depicts them accompanied by animals or animal friezes, if any. Other of his vases, like many Corinthian vases, are limited to depictions of animals. After the Gorgon painter, artists from the Komasten group (585–570 BC) should be mentioned. This group decorated with Lekanen , monocotyledonous and Kothonen new vessels for Athens. The most important innovation, however, was the introduction of the Komast bowl , which stands next to the "pre-Comast bowls" of the Oxford palmette class at the beginning of the development of the Attic bowl . The main painters in the group were the older KX painter and the not-so-talented KY painter who introduced the Colonette Crater in Athens. This imaginary for revelry vessels are decorated often with matching on Komasten .

Other notable first generation artists were the Panther Painter , the Anagyrus Painter , the painter of the Dresden Lekanis and the Polos Painter . The last significant representative of the first generation of painters was Sophilus (580-570 BC). He is the first Attic vase painter known by name. He signed a total of four preserved vases, three as a painter and one as a potter. Sophilos already showed that the potters of the black-figure style were also vase painters. A fundamental separation of the two areas only seems to have existed in the course of the development of the red-figure style, although specializations cannot be ruled out. Sophilus is very generous with his captions. He was evidently specialized in larger vessels, as dinosaurs and amphorae are particularly well known. Far more often than his predecessors, Sophilus shows mythological scenes such as the funeral games for Patroclus . The decline of the animal frieze begins with him, and other ornaments such as plant ornaments also lose their quality, since less attention has now been paid to them. Elsewhere, however, Sophilos showed that he was an ambitious artist. The wedding of Peleus and Thetis can be found on two dinosaurs . The vases were created around the same time as the François vase , which shows the same theme in perfection. But Sophilos did without any accessories in the form of animal friezes in one of his two dinosaurs and did not mix different myths in several levels of the vase. It is the first large Greek vase on which a single myth was shown in several sections arranged one below the other. A special feature of the painter's Dinoi is that he did not apply the opaque white for the women to the black glossy shade as usual, but directly to the clay background. The interior drawings and contours are done in a matt red. This technique is very rarely found in vase painting only in the workshop of Sophilus, next to it on painted wooden panels, which were made in the 6th century BC. Were painted in the Corinthian style. Sophilus also painted one of the rare calyxes (a special type of chalice) and created the first series of grave tablets . He himself or one of his successors also decorated the first surviving Lebes Gamikos .

Highly archaic time

From around the second third of the 6th century BC. The Attic artists' interest in mythological images and other figurative representations grew. The animal friezes now increasingly faded into the background. Only a few painters devoted themselves to them with greater care, mostly they were banished from the focus of attention to less important areas of the vases. The François vase by the potter Ergotimos and the painter Kleitias (570–560 BC), both of whom have signed, is particularly representative of this new style . The crater is considered the most famous work of Greek vase painting. The vase is the first known volute crater made of clay. Mythological events are portrayed on several friezes, animal friezes are shown outside the main field of vision. Several iconographic and technical details appear on the vase for the first time. Some of them, such as the depiction of a folded mast of a sailing ship, remain unique, others become standard, people seated with one leg set back instead of the usual parallel posture of both legs. Four more signed, albeit smaller, vases by Ergotimos and Kleitias have been preserved, and further vases and fragments are ascribed to them. Kleitias shows other innovations such as the first depiction of the birth of Athena or the dance on Crete.

Nearchus (565–555 BC) signed as a potter and painter. He was particularly fond of showing large figures. The first illustration of harnessing the harness to a car comes from him. Another of his innovations was the application of the tongue sheet under the vase lip on a white background. Other high quality artists were the Akropolis painter 606 and the Ptoon painter , whose most famous work is the Hearst hydria . Also of importance is the Burgon group , from which the first completely preserved Panathenaic price amphora comes.

From about 575 BC onwards, the comast bowl developed into The Siana bowls . While the Komasten group also produced other shapes in addition to the bowls, some craftsmen specialized in bowl production since the first important representative of the Siana bowls, the C painter (575–555 BC). The bowls have a higher rim than their predecessors and a trumpet-shaped base on a relatively short, hollow stem. The inside of the bowl is now decorated with framed pictures ( tondo ) for the first time in Attic vase painting . There were two types of decoration: with the “double-decker” decoration, the bowl and lip were painted separately, with the “kink frieze” variant, the image is painted over both levels of the vase body. Since the 2nd quarter of the 6th century BC BC, an increased interest in images of athletes can be seen not least on bowls. Another important Siana bowl painter was the Heidelberg painter . He too painted almost exclusively siana bowls. His most popular motif was the hero Heracles. The Heidelberg painter showed him as the first Attic painter with the Erymanthian boar , with Nereus , Busiris and in the garden of the Hesperides . At the end of the development of the Siana bowls there was the Kassandra Painter , who decorated medium-sized bowls with high feet and edges. He is particularly important as the first painter of Kleinmeister bowls . Button-handle shells were produced at the same time as the Siana shells . Their handles in the form of two-pronged forks ended in a shape reminiscent of a button. They lacked the stepped edge, and they also had a deeper pelvis and a higher and slimmer foot.

The last outstanding painter of the highly archaic period was Lydos (560-540), who signed two of his traditional works with ho Lydos (the Lydian) . He or his direct ancestors probably came from Asia Minor, but he undoubtedly enjoyed his education in Athens. Today more than 130 vases are ascribed to him. One of his pictures on a hydria shows the first known Attic depiction of the battle between Heracles and Geryon . Lydos was the first to portray Heracles with the lion skin , which was typical of Attic art in the following years . He also showed the gigantomachy on a dinosaur that was found on the Acropolis in Athens, and Heracles with Cyknos . Lydos decorated various picture carriers, in addition to hydriai and dinosaurs , plates, bowls (frieze siana bowls), grave tablets, column craters and psykteres . To this day, it is quite difficult to recognize Lydos' works as such, as they often differ only little from those around him. The style is quite homogeneous, but the quality varies a lot. The drawings are not always carefully executed. Lydos was probably the foreman in a very productive workshop in the Athens pottery district. He was probably the last Attic vase painter to show animal friezes on large vases. If he was still in the tradition of Corinth, his figure drawings are a link in the chain of vase painters who lead from Kleitias to Lydos and the Amasis painter to Exekias. With these he contributed to the Attic development and had a lasting impact on it.

A special form of Attic vases of this time were the Tyrrhenian amphorae (550-530 BC). These are egg-shaped neck amphoras, the decoration of which does not correspond to the usual Attic decoration scheme of the time. Almost all of these approximately 200 known vases were found in Etruria. The body of the amphora is usually divided into several friezes. The top one, the shoulder frieze, generally shows a common representation from the field of mythology. Sometimes there are also rare representations, such as the singular representation of the sacrifice of Polyxena . In addition, the first known erotic images can be found on Attic vases at this point. The painters often added inscriptions to Tyrrhenian amphorae, which name the people shown. The remaining two or three friezes were decorated with animals, sometimes one was replaced by a ribbon of plants. The neck is usually painted with a lotus palmette cross or loop. The amphorae are quite colored and are reminiscent of Corinthian products. Apparently a Corinthian shape was deliberately adopted here in order to produce these vases for the Etruscan market, where this style was in demand. It is possible that this form was not made in Athens, but elsewhere in Attica, possibly even outside of Attica. Important painters were the Castellani Painter and the Goltyr Painter .

The master years

The time between the years 560 and the beginning of red-figure vase painting around 530/520 BC. BC is considered to be the pinnacle of black-figure vase painting. The best and most important artists in this period made use of all the possibilities that the style offered.

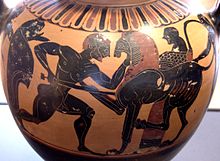

The first important painter of the time was the Amasis painter (560-525 BC), named after the important potter Amasis , with whom he primarily worked. Many researchers see both craftsmen as a single person. He began his painting career around the same time as Lydos, but was active for almost twice as long. Where Lydos showed more manual skills, the Amasis painter was an accomplished artist. His pictures are characterized by wit, charm and sophistication. The development of the vase painter almost mirrors the development of black-figure Attic vase painting of his time. In his early work he was still close to the painters of Siana bowls. The development can be seen particularly clearly in the drawing of the folds of the garment. His early female figures wear robes without folds. Later they are flat and angular, at the end they look like supple garment formations. Garment drawings were one of his main features, he liked to show patterned and fringed garments. The groups of figures shown by the Amasis painter were carefully drawn and symmetrically composed. At first they looked very calm, later you could see the movement of the figures. Although the Amasis painter often drew incidents from the myth - he is known for his pig-faced satyrs - he is particularly important because of his scenes from everyday life, which he was the first painter to show on a larger scale. With his work he significantly influenced the later work of the red-figure painters. He may have anticipated one of their changes or was influenced by it at the end of his painting career: On some of his vases women were only shown in outline drawings, i.e. not filled with black and no longer marked as such by the application of white overlay.

The group E (550-525 v. Chr.) Was a large, self-contained group of artisans. This group is considered the most important anonymous group of Attic black-figure vase painting. It broke rigorously with the stylistic tradition of Lydos, both in terms of representation and image support. Egg-shaped neck amphoras have been completely abandoned, columnar craters almost entirely. For this, the group introduced type A of the abdominal amphora, which is now becoming a leading form. Neck amphorae were mostly only produced in more special forms. The group was not interested in small forms. Many of the images, mainly based on myth, have been reproduced again and again. Several amphorae of the group show Herakles with Geryoneus or the Nemean lion as well as increasingly depictions of Theseus and the Minotaur as well as the birth of Athena. The group's particular merit, however, lies in the influence they exerted on Exekias . Most of the Attic artists of the time followed the style of Group E and Exekias. Lydos or the Amasis Painter, on the other hand, were no longer reproduced as often. Beazley formulated the meaning of the group for Exekias as follows: "Group E is the breeding ground from which the art of Exekias arises, the tradition that he assimilates and exceeds on his way from outstanding craftsman to true artist."

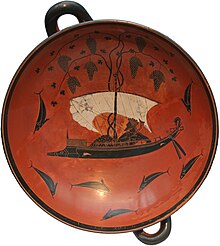

Exekias (545-520 BC) is widely considered to be the finisher of the black-figure style, which has now reached its peak. His importance lies not only in his mastery as a vase painter, but also in his high-quality and innovative pottery. He signed twelve of his preserved vessels as a potter, two as a painter and a potter. Exekias probably had a larger share in the development of the Kleinmeister's bowls , the aforementioned type A belly amphora , and possibly also invented the calyx crater , at least the oldest surviving piece from his workshop. As a painter, unlike many other representatives, he also attached great importance to the careful elaboration of the ornaments. The details of his pictures - horse's manes, weapons, robes - are executed above average. His pictures are mostly monumental, and the figures show a dignity that was previously unknown in painting. In many cases he broke with the current Attic conventions. On his most famous bowl, the Dionysus bowl, he was the first to use a coral-red coating on the inside instead of the usual red one . Exekias brings this innovation together with the classic eye cup by using two pairs of eyes on the outside . The complete use of the inside for his picture of Dionysus lying on a ship from which vines grow was probably even more innovative. The simple decoration with a gorgon face was common at that time. The bowl is probably one of the experiments that were carried out in the pottery district up to the introduction of the red-figure style in order to break new ground. He is the first to let ships sail along the edge of a dinosaur . Only rarely did he stick to the traditional patterns of previous myths. Also of particular importance is a picture of the Ajax's suicide . Exekias did not show the act itself, as was customary up to now, but the preparation for it. About as well known as the Dionysus bowl is an amphora depicting Ajax and Achilles playing a board game. Not only is the drawing detailed, Exekias himself does not leave the result of the game open, almost like in a speech bubble he lets the two players announce the numbers they rolled - Ajax a three and Achilles a four. It is the oldest picture of this scene that is never mentioned in literature. No fewer than 180 other surviving vases from the version of Exekias to about 480 BC. Show this scene.

John Boardman emphasized the extraordinary position of Exekias, which made him step out of the tradition of previous vase painting: “The people of the earlier artists are elegant dolls at best. Amasis (the Amasis painter) was able to see people as people. But Exekias could see them as gods and thus he gives us a foretaste of classical art. "

Even with the reservation that vase painters in ancient Greece were not regarded as artists but as craftsmen, Exekias counts for today's art historical research as a accomplished artist who can compete with the simultaneous “great” painting ( wall painting and panel painting ). Apparently his contemporaries also recognized this. In the Antikensammlung Berlin / Altes Museum there are still remains of a number of grave tablets . The series probably consisted of 16 individual plates. The award of such an order to a potter and vase painter is probably unique in ancient times and testifies to the high reputation of the artist. The panels show the mourning of a deceased Athenian woman as well as the laying out and transfer to the grave. Exekias shows the mourning as well as the dignity of the portrayed. A special feature is, for example, that the leader of the funeral procession has turned his face to the viewer and is looking directly at him, so to speak. The representation of the horses is unique, they have an individual character and are not reduced to their function as noble animals, as is otherwise common on vases.

The specialization in vessel and bowl producers was further advanced during the high class. From the rather large Komasten and Siana bowls, which contain a lot of liquid, finer variants of the bowl developed over the Gordion bowls, which are called Kleinmeister bowls because of their delicate painting . Accordingly, the vase painters and potters of these forms are called minor masters . The main forms of the Kleinmeister are the ribbon shell and the rim shell . The edge bowl got its name because of the rather hard edge. The outside of the bowl remains largely clay-ground and is usually decorated with only a few small pictures, sometimes only with inscriptions, or the bowls were not lavishly decorated at all. In the handle zone, too, they are rarely decorated with more than palmettes next to the handles and with inscriptions. These inscriptions could be the potter's signature, a toast or just a meaningless combination of letters. The insides of the edge bowls are often decorated with pictures.

Belt cups have a softer transition from the basin to the edge. The picture decoration is applied in the form of a circumferential band on the outside of the bowl. These are often very elaborate friezes. The edge of this shape is varnished black. The inside has been left with a clay background and a black point is only painted in the center. Special forms are the droop bowls and the Kassel bowls . Droop bowls have black, concave edges and a high foot. The edge is left black as with the ribbon cups, but the outer underside is also included in the painting. Ornaments such as leaves, buds, palmettes, points, halos or even animals were painted on. Kassel bowls are a small shape, they look squat than other Kleinmeister bowls. With this shape, the entire outside is decorated. As with the droop bowls, it is largely an ornamental painting. Well-known small masters are the potters Phrynos , Sokles , Tleson and Ergoteles , both sons of the potter Nearchus. With the Hermogenic Skyphos, Hermogenes invented a minor master version of the Skyphos as well as the vase painters Phrynos Painter , Taleides Painter , Xenocles Painter and the group of Rhodes 12264 .

The last quarter of the 6th century BC Chr.

Until the end of the century, the quality of the black-figure vase production was largely maintained. Since the development of the red-figure style around 530 BC. BC, probably through the Andokides painter , more and more painters used the red-figure style. Due to its possibilities in the interior drawing, this gave far more design leeway. In addition, the new style enabled much more promising experiments with foreshortening, perspective views or new design forms. As always, pictures were subject to taste developments and the zeitgeist, but with the red-figure style, the better design options offered better conditions for the representation of more elaborate pictures.

Initially, however, some innovative craftsmen were able to give impetus to the production of black-figure vases. The most inventive and enterprising potter of the time was Nikosthenes . More than 120 vases with his signature are known, which were accordingly made by him or in his workshop. He seems to have specialized in the manufacture of vases for export to Etruria. In his workshop common neck amphorae, Kleinmeister-, Droop- and eye bowls were made, but also an amphora shape reminiscent of the Bucchero ceramics of the Etruscans, which is called Nikosthenische Amphora after its inventor . These pieces were found mainly in Caere, the other vases mostly in Cerveteri and Vulci. The ingenuity in his workshop did not stop at the forms. In the Nikosthenischen workshop, the Sixsche technique was developed , in which the pictures were painted on the glossy shade in red-brown or white color. It is unclear whether Nikosthenes was also a vase painter, although in this case he is mostly assumed to be behind the painter N named after him . The BMN painter and the red-figure Nikosthenes painter are also named after Nikosthenes. In his workshop he employed many well-known vase painters, including the late Lydos, Oltos and Epiktetos . The workshop tradition was continued by the successor of Nikosthenes, Pamphaios .

Two black-figure vase painters are considered Mannerists (540-520 BC). The Elbows Out mainly painted small master bowls. The splayed elbows of his figures, after which he was named, are striking. He rarely shows mythological events, but likes to show pictures with love scenes. A lydion , a rarer vase shape, was also decorated by him. The more important of the two was the affecter , who got his emergency name because of his affected-looking figures. The small-headed figures do not appear to be acting, but as if they are posing. In his early days he mainly depicted everyday scenes, later he switched to decorative pictures in which figures and attributes are difficult to recognize, but processes. If he shows his figures dressed, they look as if they are upholstered, if he shows them naked, they look very angular. Affekter was both a potter and a painter; more than 130 vases have come down to us from him.

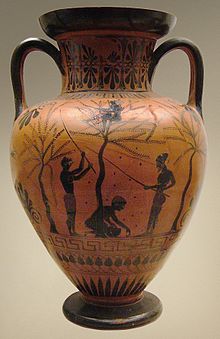

The Antimenes painter (530–500 BC) liked to decorate hydrates with animal friezes in the predella , as well as neck amphorae. Two of the hydria assigned to him are decorated in the neck region in a white-ground style . He was the first to paint amphorae with the mask-like face of Dionysus. The best-known of his more than 200 vases preserved shows an olive harvest on the back. His drawings are seldom particularly precise, but also never very careless. In terms of style, Psiax is closely related to the Antimenes painter , who, however, unlike the Antimenes painter, also worked with a red figure. As a teacher of the painters Euphronios and Phintias, Psiax had a great influence on the early development of the red-figure style. He likes to show team scenes and archers.

The last significant group of painters was the Leagros group (520–500 BC). It was named after its much-used Kalos name, Leagros . Amphorae and hydria, the latter often with palmettes in the predella, are the most frequently painted supports. The image fields are generally filled to bursting, but the quality of these images is very high. Many of the group's more than 200 vases were decorated with scenes from the Trojan War and pictures from the life of Heracles. The Leagros group included painters such as the original Acheloos painter , the conventional Chiusi painter and the detailed daybreak painter

Other well-known vase painters of the time are the painter of the mourners in the Vatican , the Princeton painter , the painter of Munich 1410 and the swing painter (540-520 BC), to whom many vases are ascribed. He is not considered a very good artist, but his pictures seem involuntarily funny because of the figures with their big heads, strange noses and often clenched fists. The Rycroft painter is close to red-figure vase painting and the new forms of expression. He especially likes to show Dionysian pictures, team scenes and the adventures of Heracles. He often shows outline drawings. He painted his approximately 50 mostly large vessels in an elegant manner. The class of Cabinet des Médailles 218 mainly decorated variants of the Nicosthenian amphorae. The Hypobibazon class adopted a newer variant of the abdominal amphora with rounded handles and feet, with the key meanders above the image fields being striking. A smaller variant of the neck amphora is painted by the three-line group . The perizoma group took the around 520 BC. Chr. Newly introduced form of the stamnos . In addition, at the end of the century the Euphiletus Painter , the Madrid Painter and the imaginative Priam Painter worked in a noteworthy quality.

Above all, bowl painters such as Oltos , Epiktetos , Pheidippos and Scythians painted vases - primarily eye bowls - in both styles, so-called bilingual vases . The inside was mostly painted in black, the outside mostly in red-figure style. There are several amphorae, the front and back of which are decorated in different styles. The works of the Andokides painter, whose black-figure pages are assigned to the Lysippides painter , are particularly well-known here . It is controversial in research whether both painters are identical. Only a few painters, such as the Nikoxenos Painter and the Athena Painter , worked in any significant quantity in both techniques. While bilingualism was popular for a short time, its time is over by the end of the century.

Late period

At the beginning of the 5th century BC Until 480 BC at the latest All painters who claim to use the red-figure style. But black-figure vases were also produced for around 50 years, the quality of which continued to decline. The last painters of acceptable quality on larger vases were the Eucharides Painter and the Cleophrades Painter. Only workshops that produced smaller shapes such as olpen, oinochoen, skyphoi, small neck amphoras and, above all, lekyths, still worked increasingly in the old style. The Phanyllis painter worked, among other things, in the Six technique, the Edinburgh painter , like the Gela painter, decorated the first cylindrical lekyths. The former painted his vases mainly with loose, clear and simple pictures using black-figure technique on a white background. The white background of the vases was quite thick and was no longer painted on the clay background. This technique should become mandatory for all vases of the white-ground style. The Sappho painter specialized in gravekyths. The workshop of the Haimon painter , from which more than 600 vessels have been preserved, was particularly productive . Athena Painter (perhaps identical to the red-figure Bowdoin Painter ) and Perseus Painter continued to decorate the larger standard Lekyths. The pictures of the Athena painter still exude something of the dignity of the pictures of the Leagros group. The marathon painter is best known for the Grablekythen, which one in the grave tumulus for the 490 BC. Found Athenians who had fallen in the battle of Marathon . As the last important Lekythen painter, began around 470 BC. The Beldam painter carried out his work until around 450 BC. Chr. Continued. Apart from the Panathenaic price amphoras, the black-figure style in Attica ended at this time.

Panathenaic price amphoras

Among the black-figure vases of Attica, the Panathenaic prize amphoras play a special role. They were since 566 BC BC - the introduction or reorganization of the Panathenaic Festival - the prize for the winners of the sporting competitions. On the front they were adorned as standard with an image of the goddess Athena between two pillars on which roosters stand, on the back with a representation from the sport. The shape was always the same and changed little over the long production period. According to its name, the abdominal amphora was initially particularly bulbous, had a short neck and a narrow, high foot. The amphorae were filled with one of the city's main export goods, olive oil. Around 530 BC The necks get shorter and the body a bit narrower. Around 400 BC The shoulders are already drawn in, the curve of the vase body looks slack. Since 366 BC The vases became more elegant and even narrower again.

The vases were mainly made in the leading workshops of the Kerameiko. It seems to have been an award or particularly lucrative to have been commissioned to produce the vases. This also explains the many prize amphoras from outstanding vase painters. In addition to black-figure masters such as the Euphiletus painter , Exekias, Hypereides and the Leagros group, many red-figure masters are also known as the creators of the price amphoras. These include the Eucharides Painter, the Cleophrades Painter , the Berlin Painter , the Achilles Painter and Sophilus , who was the only one who signed one of the well-known vases. The first amphora, the Burgon vase, came from the Burgon group. Since the 4th century BC Sometimes the name of the reigning archon is noted on the vase, some of the vases can be dated precisely. Since the Panathenaia were a religious festival, the style and form of decoration did not change either during the period of the red-figure style or after figurative vase painting was no longer practiced in Athens. The price amphoras were used until the 2nd century BC. Chr. Produced. Today about 1000 such vases are known. Since one knows for some times how high the prize money was, it can be estimated that around one percent of the vases have been preserved. With further extrapolation it can be concluded that a total of around 7 million figuratively painted vases were made in Athens. In addition to the price amphorae, imitating forms were also created, the pseudo-Panathenaic price amphorae .

Laconia

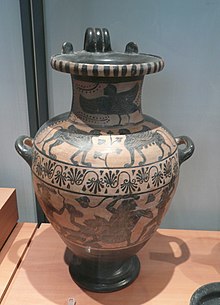

Since the 7th century BC Painted ceramics were produced in Sparta both for their own use and for export. The first high quality pieces were made around 580 BC. Manufactured. The climax was with the black-figure pottery in the period between about 575 and 525 BC. Reached. In addition to Sparta, the main sites are the islands of Rhodes and Samos as well as Taranto , Etruscan necropolises and Cyrene , which was initially thought to be the place of origin of pottery. The quality of the vessels is very high. The clay is finely muddy, it was provided with a cream-colored coating. Amphoras, hydria , colonnette craters, which in ancient times were called krater lakonikos , volute craters and craters of the Chalcidian type , lebetes , aryballoi and the Spartan drinking vessel Lakaina were painted . The main form and most common find, however, is the shell. In Laconia the deep basin was usually placed on a high foot, bowls on a low foot are far less common. The decoration of the outside with ornaments, mostly pomegranate chains , is typical , the mostly figurative interior is quite large. In Laconia, the tondo became the main carrier of the action in bowl paintings earlier than in the rest of Greece. The main picture was also split early on into two sections, a main picture and a smaller lower segment. Often the vessels were only covered with gloss or only decorated with a few ornaments. Inscriptions are not the rule, but appear as name inscriptions. Signatures are not known for either potters or painters. The laconic craftsmen were probably Perioec pottery painters, peculiarities in the pottery often coincide with the recognized painter's handwriting. Possibly it was also a question of eastern Greek wandering potters, which would explain the strong eastern Greek influence on the Boread painter in particular .

There are now at least eight vase painters. Five painters, the Arkesilas Painter (565–555), the Boreaden Painter (575–565), the Hunt Painter , the Naukratis Painter (575–550) and the Reiter Painter (550–530) are considered to be the more important representatives of the style, while other painters are considered to be artists of less skill. The pictures usually appear angular and stiff. Animal friezes, everyday scenes, especially from symposia and many mythical images are shown. Above all, Poseidon and Zeus are frequently depicted here, but also Heracles with his 12 deeds as well as the Theban and the Trojan sagas. A gorgoneion is also used as a shell tondo, especially in early vases. A special feature is a picture of the nymph Cyrene , as well as a tondo with a rider who has a volute tendril growing out of his head (name vase of the horseman painter). Of particular importance is a bowl with the depiction of Arkesilaos II. ( Arkesilas bowl ), which gave the Arkesilas painter the emergency name. It is one of the rare representations of current events or people in Greek vase painting. The subjects of the picture reveal Attic influences. The main color used was a shade of red with a strong purple tinge. More than 360 laconic vases are currently known, almost a third of them, 116 pieces, go back to the Naukratis painter. The decline of Corinthian black-figure vase painting, which had a great influence on laconic painting, around 550 BC. Chr. Led to a massive slump in the laconic production of black-figure vases, which finally began around 500 BC. Came to a standstill. The pottery was very widespread, from Marseilles to Ionian Greece. On Samos, laconic pottery is more common than Corinthian pottery due to the close political ties to Sparta.

Boeotia

From the 6th to the 4th century BC Black-figure vases were produced in Boeotia. In the early 6th century BC Many Boeotian painters used the orientalizing outline technique. After that they orientate themselves particularly closely to the Attic production. Sometimes it is difficult to differentiate and assign to one of the two regions, and it can also be confused with Corinthian pottery. It is not uncommon for Attic and Corinthian vases made of inferior ceramics to be declared Boeotic works. Often, good Boeotian vases were initially mistaken for Attic, but bad Attic vases were mistaken for Boeotian. There was probably an exchange of skilled workers with Attica, at least once it has been proven that an Attic potter emigrated to Boeotia ( horse-bird painter , possibly also the Tokra painter , among the potters certainly Teisias the Athenian ). The most important motifs are animal friezes, symposia and comasts. Mythical images are rather rare; when they appear, Heracles or Theseus is usually shown. For the late 6th and 5th centuries, a silhouette-like style is prevalent. Kantharoi , Lekaniden , bowls , plates and jugs are mainly painted . As in Athens, there are favorite inscriptions ( Kalos inscriptions). Particularly fond presented Boeotian pottery plastic vessels ago, also kantharoi with plastic lugs and tripod - pyxides . Lekanis , bowl and neck amphora are also taken from Athens . The style of painting is often comical; comasts and satyrs are preferred.

Between 425 and 350 BC The Kabiren vases were the main black-figure style in Boeotia. Mostly it was a deep mixed form between Kantharoi and Skyphoi with vertical ring handles, besides Lebetes, bowls and pyxids. They were named after their main place of discovery, the Kabiren shrine near Thebes . The pictures show the cult there. The vases, which are mostly only painted on the front, caricature mythological events in a humorous, exaggerated form, sometimes Comos scenes are also depicted, which are probably directly related to the cult.

Euboea

The black-figure vase painting of Euboea was also influenced by Corinth and especially by Attica. Differentiating it from Attic vases is not always easy. Research suggests that most of the pottery was made in Eretria . Mainly amphorae, lekyths, hydrates and plates were painted. Large-format amphorae were mostly used as image carriers for mythical scenes, such as the adventures of Heracles or the judgment of Paris. The large amphorae, which differ from shapes dating back to the 7th century BC. Chr. Derive, have conical lips and mostly show pictures with wedding related. These were obviously grave vases made for children who had died before their wedding. Typical of the black-figure ceramics from Eretria was the restrained use of incisions and the regular use of opaque white for the floral ornaments. In addition to images based on attic, wilder images were shown, such as the rape of a deer by a satyr or Heracles with centaurs and demons. The vases of the dolphin group used to be considered Attic, but are now considered Euboean. But their tone does not correspond to any known source of Eretria. It may have been produced in Chalkis .

The origin of some black-figure regional styles is disputed. So the Chalcidian vase painting was initially referred to Euboea, now it is more likely that it was made in Italy.

Eastern Greece

In hardly any other Greek region are the boundaries between orientalizing and black-figure styles as fluid as in Eastern Greek vase painting. Until about 600 BC Only outline drawings and recesses were used in the 2nd century BC, then, coming from Northern Ionia, the use of incised drawings began during the late phase of the orientalizing style. The animal frieze style that had prevailed until then was quite decorative, but offered hardly any opportunities for further technical and design development. Especially in Ionia, regional styles emerged.

In the final phase of the Wild Goat style (wild goat) nordionische artists imitated - rather poor quality - Corinthian models. But as early as the 7th century, high-quality vases were being produced in Ionia. Since around 600 BC The black-figure style was used in whole or as part of the decoration of vases. In addition to the developing regional styles in Klazomenai , Ephesos , Miletus , Chios and Samos , there were styles that could not be more precisely localized, especially in northern Ionia. Vessels of anointing oil based on the Lydian model ( Lydion ) were widespread, but mostly only decorated with stripes. There are also original images, such as a Scythian with a Bactrian camel or a satyr and a ram. For some styles, the assignment is very controversial. The Northampton Group, for example, has strong Ionic influences, but it was probably created in Italy - possibly by immigrants from Ionia.

In Klazomenai people painted in the middle of the 6th century BC. BC (around 550 to 530 BC) mainly amphorae and hydria as well as deep bowls with flat, angular-looking figures. The vessels are not very elegant. We are happy to depict women or animals. The leading workshops were those of the Tübingen painter , the Petrie painter and the Urla group . Most of the vases were made in Naukratis and in 525 BC. Found abandoned Tell Defenneh . The origin was initially unclear, Robert Zahn recognized the origin by comparing it with the pictures on clazomenic sarcophagi . It was not uncommon for ceramics to be decorated with plastic women's masks. Mythological scenes are rarely shown; scale ornaments, rows of white dots and stiff-looking dance of women are popular. The depiction of a herald before a king and queen was singular and unusual. In general, men were characterized by enormous spade beards. Already since 600 to about 520 BC BC, the rosette bowls , successor to the Eastern Greek bird bowls , were probably made in Klazomenai .

Sami ceramics first appeared around 560/550 BC. BC with forms that she took over from Attic ceramics . These are small master bowls and kantharoi in the shape of a face. The painting is precise and decorative. Along with Miletus and Rhodes, Samos was one of the main centers for the production of wild goat-style vases.

The Rhodian vase painting is particularly known for its Rhodian plates . They are painted using a polychrome technique, some details have been scratched as in black-figure painting. Around 560 to 530 BC Chr. Reign oriented Egyptian models Situlae ago. They show both Greek themes, such as Typhoeus , as well as ancient Egyptian images such as Egyptian hieroglyphics and Egyptian sports.

Italy including Etruria

Caeretan hydrates

The Caeretaner Hydrien is a particularly colorful style of black-figure vase painting. Research has argued about the origin of the vessels. In the last few years the view has become more and more accepted that the producers of the vases are two pottery painters who immigrated to Caere in Etruria from Eastern Greece. Because of their painting, the vases were considered Etruscan or Corinthian for a long time. However, inscriptions in Ionic Greek supported the theory of immigration. Their workshop lasted only one generation. Today about 40 vases of the style are known that the two masters produced. All of them are hydrated except for one alabastron . None of them were found outside Etruria, most of them in Caere. They also have their names after the place. The vases are dated between 530 and 510/500 BC. Dated. The Caeretaner Hydrien adjoin the neck amphorae stylistically painted with stripes.

The technically rather inferior hydria have a height of 40 to 45 centimeters. The vase bodies have recessed, high and broad necks, broad shoulders and low ring feet in the form of inverted goblets. Quite a few of the hydrates are deformed or have false fires. The painting of the body was divided into four zones: shoulder, a figurative and an ornamental belly zone and a lower end. With the exception of the figurative abdominal zone, all zones were decorated with ornaments. Only once is it known that two figural friezes were applied. This genre differs from all other black-figure styles in its multicolor. The style is reminiscent of Ionic vase painting and of multi-colored wooden panels found in Egypt. Men can be shown with red, black or white skin, women are almost always indicated by opaque white. The contours as well as the details are carved as usual in the black-figure style. Surfaces made of black gloss tone were often covered with another colored layer of gloss tone, so that the black gloss tone became an interior drawing when scratched. On the front the representations are always animated, on the back they are more often heraldic. The ornaments are an important part of the hydration, they do not take a back seat to the other motifs. Templates were used for the ornaments. They are not scratched.

The painters are called Busiris Painter and Eagle Painter . The latter is considered the leading exponent of the style. They had a special interest in mythological materials, which mostly also show an Eastern influence. On the name vase of the Busiris painter, Heracles tramples the mythical Egyptian pharaoh Busiris. Heracles is also often depicted elsewhere. There are also pictures from everyday life. Rare images are also shown, such as Keto , who is accompanied by a white seal.

Pontic vases

The Pontic vases are stylistically closely related to the Ionic vase painting. They are also believed to have been made in Etruscan workshops by craftsmen who immigrated from Ionia . The vases got their misleading name because of the depiction of archers on a vase, which was thought to be Scythians who lived on the Black Sea (Pontus). Most of the vases were found in tombs in Vulci, and another considerable part in Cerveteri. The main form was the neck amphora, which was noticeably slim. They are very similar to Tyrrhenian amphorae. Other forms were oinochoen with spiral handles, dinoi, kyathos, plates and tall cups, more rarely kantharos or others. The structure of Pontic vases is the same. In general, they have an ornamental decoration on the neck, followed by a more figural one on the shoulder, followed by another ornamental band, which was followed by an animal frieze and finally a halo. The base, neck and handle are black. The importance of the ornaments is striking. Sometimes vessels are decorated purely ornamentally. The tone of the vases is yellowish-red, the glossy shade with which the vases were coated was black to brownish-reddish, is of high quality and has a metallic sheen. Red and white body paint was used extensively for the figures and the ornaments. Animals were usually decorated with a white stripe on the belly. The ornaments are often designed rather carelessly. To date, research has identified six workshops. The earliest and best is that of the Paris painter . Shown are mythological figures, including one as common in Eastern Greece beardless Heracles. Sometimes there are scenes outside of Greek mythology, such as Heracles fighting Iuno Sospita by the Paris painter or a wolf demon by the Tityos painter . In addition, scenes from everyday life, comasts and riders were painted. The vases are made between 550 and 500 BC. Dated. About 200 vases are known today.

Etruria

An own production of Etruscan vases probably started in the 7th century BC. A. The vases were initially based on black-figure models from Corinth and Eastern Greece. It is believed that Greek immigrants were the main producers in the early stages. The first important style was the Pontic vase painting. This was followed in the period between 530 and 500 BC. The Micali painter and his workshop. At that time, Etruscan artists were more oriented towards Attic models. They mainly created amphorae, hydrates and pitchers. These mostly show comasts, symposia and animal friezes. It is less common that they are mythical pictures, but they are designed very carefully. The black-figure style ended around 480 BC. Finally, the style developed mannerist and towards a less careful silhouette technique.

Chalcidian ceramics

The Chalcidian vase painting was named after mythological inscriptions, which were sometimes applied in Chalcidian script . Therefore, the origin of the pottery was initially assumed to be in Evia. It is now assumed that the pottery was made in Rhegion , perhaps also in Caere . However, the question has not been finally resolved to this day. The Chalcidian vase painting was influenced by the Attic, Corinthian and especially the Ionic vase painting. The sites are in Italy (Caere, Vulci and Rhegion), but also in other places in the western Mediterranean.

The production of the Chalcidian vases starts suddenly around 560 BC. A. Forerunners have not yet been identified. Already after 50 years, around 510 BC It ended again. About 600 vases are known today. 15 painters or groups of painters have been identified so far. The vases are characterized by the excellent quality of the pottery. The gloss shade with which they were coated is generally deep black after the fire. The tone has an orange hue. When painting, red and white opaque colors are used generously, as well as incisions for internal drawing. The main form is the neck amphora, which makes up a quarter of all known vases, there are also eye cups, oinochoa and hydria, other vessels are less common. Lekanids and cups based on the Etruscan model are exceptions. In terms of construction, the vases appear taut and strict. The “Chalcidian bowl foot” is characteristic. It is sometimes imitated in black-figure vases in attic, less often in red-figure vases ( chalcidizing bowl ).

The most important representative among the recognized artists is in the older generation of the inscription painters , among the younger representatives the Phineus painters . The former is believed to be the inventor of the style; the very productive workshop of the latter alone is attributed about 170 of the known vases. He is probably also the last representative of the style. The images usually have a decorative rather than narrative effect. Riders, animal friezes, heraldic images or groups of people are shown. A large lotus palmette cross is often part of the picture. Mythical images are rarely shown, but these are generally of particularly outstanding quality.

The Chalcidian vase painting is followed by the pseudo-Chalcidian vase painting . It is based strongly on the Chalcidian, but also has strong references to Attic and Corinthian vase painting. The artists here do not use the Chalcidian but the Ionic alphabet for inscriptions. In addition, the vases have a different tone quality. Today about 70 vases of the genus are known, which was first put together by Andreas Rumpf . The artisans may be the successors of the Chalcidian vase painters and potters who immigrated to Etruria.

The pseudo-Chalcidian vase painting can be divided into two groups. The older of the two groups is the Polyphemus group . She also made most of the surviving works. They mainly created neck amphoras and oinochoes. Usually groups of animals are shown, rarely mythical images. The vessels were found in Etruria and Sicily, but also in Marseille and Vix . The younger and less productive Memnon group , to which 12 vessels are currently assigned, had a much smaller distribution area, which was limited exclusively to Etruria and Sicily. Except for one oinochoe, they only produced neck amphoras, which were mostly painted with animals and riders.

Other

With the exception of a single abdominal amphora, the vases of the Northampton Group were all small neck amphorae. Stylistically, they are very close to Northern Ionian vase painting. However, they were probably not made in Ionia, but in Italy, probably in Etruria, around 540 BC. Chr. Produced. The vases of the group are very high quality products. They show rich ornamental painting and partly scientifically very interesting pictures, including a prince with horses and a crane rider. They are closely related to the works of the Campana Dinoi group and the so-called Northampton Amphora , the tone of which corresponds to that of Caeretan Hydrien. The Northampton group was named after the Northampton amphora. The round Campana hydrates, painted with animal friezes, are reminiscent of Boeotian and Euboean models.

Other regions

Alabastrons with a cylindrical body by Andros or the Lekanen by Thasos , which are reminiscent of Boeotian products, but have two individual animal friezes instead of the individual animal friezes customary for Boeotia are rare . Thai plates are more based on Attic models and are more ambitious with their figure images than the Lekanen. Imitations of Chiot vases of the black-figure style are also known from the island. The local black-figure pottery from Halai is also very rare. After the Athenians had occupied Elaious near the Dardanelles , a local black-figure ceramic production was also established there. The modest production produced simple lekanes with pictures in outline drawings. Very few black-figure style vases were made in Celtic France. They too were almost certainly inspired by Greek vases.

Exploration and reception

→ For a description of the research and reception before the 19th century, see the representation in the sister article Red Figure Vase Painting , as there were no notable differences in research into the two styles.

Scientific research into vases began particularly in the 19th century. Since that time it has also been assumed that the vases are not of Etruscan but of Greek origin. A discovery of a Panathenaic price amphora in Athens by Edward Dodwell in 1819 supported this assumption. The first to provide evidence was Gustav Kramer in his work Styl and Origin of the Painted Greek Clay Vessels (1837). However, it took a few years before this realization could really take hold. Eduard Gerhard published the essay Rapporto Volcente in the Annali dell'Instituto di Corrispondenza Archeologica , in which he was the first researcher to devote himself to the systematic research of vases. To this end, he examined the vases found in Tarquinia in 1830 and compared them with vases found in Attica or Aegina . During his studies, Gerhard was able to distinguish 31 painter and potter signatures. Until then, only the potter Taleides was known .

The next step in the research was the scientific cataloging of the large museum vase collections. In 1854 Otto Jahn published the vases of the Antikensammlung in Munich , catalogs from the Vatican Museums (1842) and the British Museum (1851) had already been published. The description of the vase collection in the antiquarium of the Berlin Antikensammlung , which Adolf Furtwängler acquired in 1885, was particularly influential . Furtwängler arranged the vessels for the first time according to artistic landscapes, technique, style, shapes and painting style and thus had a lasting influence on further research into Greek vases. Paul Hartwig tried in 1893 in the book Meisterschalen to differentiate between different painters on the basis of favorite inscriptions, signatures and style analyzes. Edmond Pottier , curator of the Louvre , initiated the Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum in 1919 . All major collections worldwide are published in this series. To date, more than 300 volumes in the series have been published.

John D. Beazley has made a particular contribution to the scientific research of Attic vase painting . From around 1910 he began to work with vases, using a method developed by the art historian Giovanni Morelli for examining paintings and refined by Bernard Berenson . He assumed that every painter creates individual works of art that can always be assigned unmistakably. Certain details, such as faces, fingers, arms, legs, knees, folds in clothes and the like were used. Beazley examined 65,000 vases and fragments, 20,000 of which were black-figure. In the course of his almost six decades of studies , he was able to assign 17,000 painters to known names or to painters identified using a system of emergency names ; he summarized them in painter groups or workshops, circles and style relationships. He distinguished more than 1500 potters and painters. No other archaeologist has ever had such a formative influence on the exploration of an archaeological sub-area as Beazley, whose analyzes are still largely valid today. Beazley's form of style analysis has been criticized repeatedly as circular in recent years . According to Beazley, researchers such as John Boardman or Erika Simon and Dietrich von Bothmer dealt with the black-figure Attic vases.

The fundamental research on Corinthian ceramics comes from Humfry Payne . In the 1930s, Payne created an initial stylistic structure that has basically remained to this day. He arranged the vases according to shape, type of decoration and subject matter of representation. A distinction between painters and workshops was only made last. Payne based himself on Beazley's method, but placed only a subordinate value on painter and group assignments. A framework for chronological order was more important to him. Jack L. Benson took on this task in 1953 and distinguished 109 painters and groups. Most recently Darrell A. Amyx summarized the research in 1988 in his Corinthian Vase-Painting of the Archaic Period . In research, however, it is fundamentally discussed whether the possibilities of assigning painter personalities to Corinthian vase painting are even given.

Laconic pottery was known in significant numbers from Etruscan tombs since the 19th century. At first, however, it was incorrectly assigned and for a long time it was considered a product from Cyrene, where some of the earliest finds were also made. Thanks to British excavations carried out in the Artemis Orthia sanctuary of Sparta since 1906 , the true origin was quickly discovered. In 1934 Arthur Lane summarized the known material and was the first archaeologist to distinguish between different painters. In 1956 the new discoveries were examined by Brian B. Shefton . He reduced the recognizable painters by half. In 1958 and 1959 other important new finds from Taranto were published. In addition, a significant number of other vases were found on Samos. Conrad M. Stibbe re- examined all 360 vases known to him and published his findings in 1972. He distinguished between five major and three minor vase painters.

In addition to researching Attic, Corinthian and laconic vase painting, archaeologists have always been particularly interested in the smaller styles based in Italy. The Caeretaner Hydrien were the first to be recognized and named by Carl Humann and Otto Puchstein . Andreas Rumpf and Adolf Kirchhoff , who coined the name, and other archaeologists wrongly suspected the origin of the Chalcidian ceramics in Evia. Georg Ferdinand Dümmler is responsible for the incorrect naming of the Pontic vases , which he suspected based on the depiction of a Scythian on one of the vases in Pontos . Research into all styles is now carried out less by individuals than by a large group of international scientists.

literature

General

- John Boardman : Early Greek Vase Painting. 11th - 6th Century BC. A handbook. Thames and Hudson, London 1998, ISBN 0-500-20309-1 .

- John Percival Droop : Droop Cups and the Dating of Laconian Pottery. In: Journal of Hellenic Studies . Vol. 52, 1932, pp. 303-304.

- Thomas Mannack : Greek vase painting. An introduction. Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-8062-1743-2 .

- Heide Mommsen , Matthias Steinhart : Black-figure vase painting. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 11, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01481-9 , Sp. 274-281.

- Ingeborg Scheibler : Greek pottery art. Manufacture, trade and use of antique clay pots. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39307-1 .

- Ingeborg Scheibler: vase painter. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 12/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01482-7 , column 1147 f.

- Erika Simon , Max Hirmer : The Greek vases. 2nd revised edition. Hirmer, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-7774-3310-1 .

- Matthias Steinhart: Pottery and master drawing. Attic wine and oil vessels from the Zimmermann collection. von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1896-0 .

Attica

- John D. Beazley : Potter and Painter in Ancient Athens. (= Proceedings of the British Academy 30, ISSN 0068-1202 ). Cumberledge, Oxford 1944.

- John D. Beazley: The Development of Attic Black-figure . (= Sather Classical Lectures 24, ZDB -ID 420164-4 ). University of California Press et al., Berkeley CA et al. 1951 (Revised edition. Ibid. 1986, ISBN 0-520-05593-4 ).

- John D. Beazley: Attic Black-figure Vase-painters. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1956.

- John D. Beazley: Paralipomena. Additions to Attic black-figure vase-painters and to Attic red-figure vase-painters. 2nd edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1971.

- John Boardman: Black-Figure Vases from Athens. A handbook (= cultural history of the ancient world . Vol. 1). Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1977, ISBN 3-8053-0233-9 .

- Heide Mommsen: Tyrrhenian amphorae. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 12/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01482-7 , Sp. 955-955.

Corinth

- Humfry Payne : Necrocorinthia. A study of Corinthian art in the archaic period. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1931.

- Humfry Payne: Protocorinthian Vase Painting. (= Research on ancient ceramics. Row 1: Pictures of Greek vases. Vol. 7, ISSN 0933-1808 ). Keller, Berlin-Wilmersdorf 1933 (reprinted by Zabern, Mainz 1974).

- Darrell A. Amyx , Patricia Lawrence: Archaic Corinthian Pottery and the Anaploga Well. (= Corinth 7, 2). American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Princeton NJ 1975, ISBN 0-87661-072-6 .

- DA Amyx: Corinthian Vase-Painting of the Archaic Period. 3 volumes. University of California Press et al., Berkeley CA et al. 1988-1991, ISBN 0-520-03166-0 .

- Vol. 1: Catalog. (= California Studies in the History of Art 25, 1). University of California Press, Berkeley CA 1988.

- Vol. 2: Commentary: The Study of Corinthian Vases. (= California Studies in the History of Art 25, 2). University of California Press, Berkeley CA 1988.

- Vol. 3: Indexes, Concordances, and Plates. (= California Studies in the History of Art 25, 3). University of California Press, Berkeley CA 1988.

- on this: Cornelius W. Neeft: Addenda et Corrigenda to DA Amyx, Corinthian Vase-Painting in the Archaic Period. (= Allard Pierson Series. Scripta minora 3). Burg, Alkmaar 1991, ISBN 90-71211-18-5 .

- Darrell A. Amyx, Patricia Lawrence: Studies in Archaic Corinthian Vase Painting. (= Hesperia. Supplement 28). American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Princeton NJ 1996, ISBN 0-87661-528-0 .

- Matthias Steinhart : Corinthian vase painting. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2 , Sp. 738-742.

Laconia

- Arthur Lane : Lakonian Vase Painting. In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . Vol. 34, 1933/34, pp. 99-189.

- Matthias Steinhart : Laconic vase painting. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2 , Sp. 1074 f.

- Conrad M. Stibbe : Laconic vase painters of the 6th century BC Chr. (= Studies in Ancient civilization. New Series 1). 2 volumes. North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam and London 1972, ISBN 0-7204-8020-5 .

- Conrad M. Stibbe: Laconic vase painters of the sixth century BC Chr. Supplement. von Zabern, Mainz 2004, ISBN 3-8053-3279-3 .

- Conrad M. Stibbe: Laconian Mixing Bowls. A History of the Lakonikos Krater from the seventh to the fifth century BC (= Laconian black-glazed pottery. Part 1: Allard Pierson Series. Scripta minora. Vol. 2). Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam 1989, ISBN 90-71211-16-9 .

- Conrad M. Stibbe: Laconian Drinking Vessels and Other Open Shapes. (= Laconian black-glazed pottery. Part 2: Allard Pierson Series. Scripta minora. Vol. 4). Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam 1994, ISBN 90-71211-22-3 .

- Conrad M. Stibbe: Laconian Oil Flasks and Other Closed Shapes. (= Laconian black-glazed pottery. Part 3: Allard Pierson Series. Scripta minora. Vol. 5). Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam 2000, ISBN 90-71211-33-9 .

- Conrad M. Stibbe: The other Sparta. (= Cultural history of the ancient world. Vol. 65). von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1804-9 , pp. 163-203.

other areas

- John D. Beazley: Etruscan vase painting. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1947.

- John Percival Droop: The dates of the vases called 'Cyrenaic'. In: Journal of Hellenic Studies. Vol. 30, 1910, ISSN 0075-4269 , pp. 1-34.

- Andreas Rumpf : Chalcidian vases. Using the preliminary work by Georg Loeschcke . de Gruyter, Berlin et al. 1927.

- Gerald P. Schauss : Eastern Greek vase painting. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 9, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01479-7 , Sp. 92-96.

- Matthias Steinhart: Caeretaner Hydrien. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 2, Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01472-X , column 907 f.

- Matthias Steinhart: Chalcidian vase painting. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 2, Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01472-X , Sp. 1088 f.

- Matthias Steinhart: Pontic vase painting. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 10, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01480-0 , column 138 f.

Web links