History of Loerrach

| 1102 | First mention of Lörrach as Lorach in a document from the St. Alban Monastery | |

| 1403 | On January 26, 1403 King Ruprecht of the Palatinate granted Lörrach market rights | |

| 1452 | Confirmation of the market rights by Emperor Friedrich III. | |

| 1678 | French troops destroy Rötteln Castle | |

| 1682 | Margrave Friedrich Magnus von Baden-Durlach gives Lörrach town charter on November 18, 1682 | |

| 1756 | Renewal of the town charter and move into the first town hall in Wallbrunnstraße | |

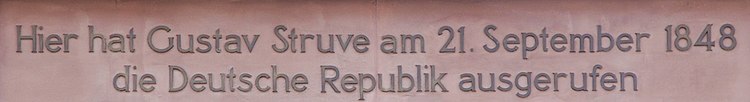

| 1848 | Gustav Struve proclaimed the German Republic on September 21, 1848 in Loerrach | |

| 1908 | Incorporation of Stettens | |

| 1975 | Incorporation of Brombach and Hauingen |

The history of Lörrach begins with the first mention of the settlement in 1102. However, archaeological finds prove the presence of people as early as the Paleolithic . Lörrach was granted market rights in 1403. It was not until 1682 that Friedrich Magnus von Durlach gave the town its town charter and, compared to its sub-towns and other localities in the region, has a relatively young town history. The place hardly developed because of the neighborhood of the dominant Basel and largely retained its village character until the second urban elevation. Even the historiography rarely mentioned Lörrach until the late Middle Ages, so that the development of Lörrach is often derived from that of Basel. In 1756 the town charter was renewed after it had been forgotten due to various armed events.

In the 19th century, Lörrach was the scene of the March Revolution in Germany, where the German Republic was proclaimed in September 1848 as a result of the second Baden Revolution. The city owes its upswing at the time of industrialization to its location on the Wiese River and the favorable traffic situation on one of the most important north-south connections across the Alps . Lörrach gained notoriety far beyond the region, primarily through the textile processing industry. The eventful history of Lörrach also includes the changing membership of different noble families and territories . Parts of today's Lörrach belonged to Upper Austria , later to the state of Baden ; since 1952 it has belonged to Baden-Württemberg .

Earlier settlement of the Loerrach area and Roman times

prehistory

Stone tools, the oldest traces of human settlement in the Lörrach area, were found in Wyhlen on the Upper Rhine and, because of the loess deposits that were above the discovered tools, dated to the Paleolithic Age. Finds in the caves of the Isteiner Klotz from the Middle Stone Age (ended around 4500 BC) indicate mining activities and reindeer hunters . The finds in the Lörracher district begin with the Neolithic Age , a period in which village-like settlements were formed during the transition to sedentariness. Along with this, agriculture, cattle breeding, stone cutting and ceramic production developed. Archaeological finds of stone tools in the Homburg Forest , in the Moosmatte in today's Stetten and in the Dalcher Boden in Tüllingen indicate living spaces. From the Iron Age (the Hallstatt period lasted from around 800 to 400 BC), a large number of fortified hilltop settlements and barrows on the Grenzacher Horn , on the skull mountain , Hünerberg and in the Homburg forest have been preserved.

In the 1st century BC The Celts from the Helvetii tribe settled in the valleys of the tributaries of the Rhine . Many geographical names for mountains, rivers and places come from the Celtic language, such as the Rhine, which arose from the Celtic Rhennos = the flowing . Traces of Celtic settlers can also be found in Herten , Wyhlen and Inzlingen . At the cross mark east of Lörrach there is a Celtic square hill from the La Tène period , which presumably served cultic purposes.

Roman times

For several centuries the region between the Rhine and Limes belonged to the Roman Empire . Under Emperor Augustus , expansion began with the occupation of the left bank of the Rhine. Around 50 AD under Emperor Claudius , Romanization continued across the Upper and Upper Rhine region to the Limes. This ushered in the end of the Celtic independence and the Latène culture. The south-west German Roman area was called the Zehntland ( Latin : Agri decumates ). It is noticeable that, in contrast to the Basel area, the southern Upper Rhine region and the High Rhine Valley, only little evidence of the Roman period can be found in the Lörrach district. The front meadow valley and the Dinkelberg did not belong to the area of interest of the Roman conquerors. Traces of Roman times are only preserved in today's Stetten and in Brombach . The Roman Empire initially limited itself to the expansion and strategic protection of the front line ( Danube - Kaiserstuhl ) with forts in the hinterland. Central points of Roman culture south of the Rhine were Vindonissa ( Windisch ) near Brugg , Basilea (Basel) and Colonia Augusta Rauracorum ( Augst ). In 40 BC Augusta Rauracorum, founded in BC, led two bridges over the Rhine. Around 100 AD, Emperor Trajan had a road built from Augst via Haltingen and Efringen to Heidelberg and Mogontiacum ( Mainz ). The more important roads of the Romans ran on the left bank of the Rhine. In 300 AD, the Rhine and Lake Constance formed a border between the Romans and the Alemanni , on which the two peoples repeatedly fought over and over.

In Lörrach, where the Romanization process started later, you can find the remains of a Roman estate, a so-called Villa Rustica , in a scenic location . The excavated and restored foundation walls of the Villa Rustica in Brombach are the only evidence of Roman buildings that has been discovered. Only with the breakthrough of the Roman defense lines in AD 260 by the Alemanni were the Romans pushed back. In the following centuries the Alemanni settled in southwestern Germany. Numerous settlements (e.g. Grenzach, Wyhlen, Basel, Weil , Haltingen, Brombach, Lörrach, Stetten) that still exist date from this time . However, the Roman influence continued to have an impact in many areas, including agriculture and viticulture . At the latest with the death of the Roman governor Aëtius in 454, Roman rule north of the Alps can be regarded as ended.

From the first mention to the late Middle Ages

Early middle ages

Most of the villages in southwestern Germany with the endings -ingen , -heim , -ach, -bach, -weil and -stetten emerged in the 6th and 7th centuries. A second wave of settlement also reached the upper Wiesental as far as Todtnau . Around 500 AD the Alemanni came under the rule of the Franks . In 746, all the leaders of the Alemanni were slain in the so-called blood court at Cannstatt on the orders of Pippin the Younger and Karlmann . In the area of today's Lörrach there are numerous indications of settlement in the Merovingian period . The districts of Tumringen , Tüllingen and Hauingen bear witness to the early founding through their names. Stetten, formerly known as Stetiheim , speaks for an expansion period in the 7th century. 600 proclaimed holy Fridolin the Christianity . The village of Zell was then a cella of the Fridolin monks. Stetten, founded by the Säckingen monastery, was first mentioned in a document in 763 and its church was consecrated to Saint Fridolin in honor of the Fridolin monks. As a collegiate fiefdom under the Habsburg patronage, Stetten was awarded to the front of Austria and remained Catholic after the Reformation . A document dated September 7, 751 documents the donation of an Ebo and his wife Odalsinda to the St. Gallen monastery . The text also speaks of a church in Rötteln (ecclesia Raudinleim) . The author of this document was a priest Landarius from the church in Rötteln. Of St. Blaise from were deaneries formed (1100 Weitenau, 1126 in Bürgeln and Sulzburg ) and a convent in Sitzenkirch . The enormous expansion of the property helped the St. Blasien Monastery to gain political and spiritual influence and made it known far beyond the region. In the 12th and 13th centuries, the village of Lörrach also gained in importance.

First mention of Lörrach until the end of the Lords of Rötteln

In 1083 the founder of Bishop of Basel Burkhard von Hasenburg the Cluny - Abbey of St. Alban . Burkhard, who was Bishop of Basel for 35 years, supported King Henry IV on his way to Canossa in 1077 during the investiture dispute . Because of Burkhard's loyalty to Heinrich, he tried to strengthen the diocese of Basel with privileges and donations. Bishop Burkhard, for his part, secured his episcopal territory in Basel by building a city wall around the city.

The first written mention of Lörrach in 1102, which was also remembered at the anniversary celebrations, dates from this time. The founding report of the St. Alban Monastery shows that Bishop Burkhard appointed Baron Dietrich von Rötteln to be the patron of the property on the right bank of the Rhine. Literally it says in the certificate:

- Lorach cum ecclesia omnibusque suis appenditiis [...] , ie: Lörrach with its church and all affiliations; This means, for example, fields, meadows and vineyards.

The list also includes the churches in Hauingen, Biesheim and the Martinskirche in Basel . It remains to be seen why Lörrach was mentioned so late, especially since the surrounding neighboring towns were mentioned much earlier in the Carolingian documents of the Lorsch and St. Gallen monasteries . The most plausible theory for this is that Heinrich IV's possessions in Kleinbasel and Lörrach did not come to the Basel bishop until the 11th century. This would explain why the place, which, according to archaeological findings, is old-settled and probably also has a pre-medieval place name, does not appear in the documents. Certificates are only preserved where something has been given.

The history of the free lords of Rötteln is closely linked to that of Lörrach. The exact origin of the noble family is not known. They were first mentioned in 1102/1103; In this year a Dietrich von Rötteln received the bailiwick of the goods of the young St. Alban monastery in Basel. Large parts of the possessions of the Lords of Waldeck fell to the Lords of Rötteln by inheritance . It is assumed that the Lords of Rötteln already owned the castle and church of Rötteln at that time. The possessions of the Lords of Rötteln must have had a solid base, which also enabled them to have a strong influence in the area of the diocese of Basel and partly in the diocese of Constance . The lords of Rötteln mainly held ecclesiastical offices, partly as canons or bishops. What Dietrich von Rötteln, who probably lived until 1123, owned, can hardly be reconstructed in the first generations due to a lack of donation deeds.

In the 12th century, the Lords of Rötteln - Dietrich II. (1147) and Dietrich III. (1189) - on the Second or Third Crusade under Emperor Barbarossa and died. A branch temporarily lived in the small Rotenburg castle near Wieslet in the small meadow valley. However, these two lines were hostile and also faced each other in fighting. Two factions formed in these disputes. The Counts of Habsburg as well as those of Pfirt and Eptingen sided with the Staufer Emperor Friedrich II. The Lords of Rötteln and the Margraves of Hachberg sided with the Psittichers who were loyal to the Pope . In 1238 Lüthold I of Rötteln became Bishop of Basel. Lüthold was also unable to avoid the major political disputes and supported the party of the opponents of Frederick II, who had meanwhile been involved in heavy battles with the papacy . Liutold's actions thus stood in opposition to the Basel citizenship and the almost civil war-like disputes between the city and the bishop meant that he had to resign in 1248.

In 1259, Rötteln Castle was first mentioned in a document. This happened under Konrad von Rötteln, who also made Schopfheim a town. The castle probably already existed in the 11th century. The Röttler family died out during this time. Lüthold II von Rötteln († May 19, 1316), who should have become Bishop of Basel, was the last male representative and in 1315 gave the rights to the Röttler rule to Margrave Heinrich von Hachberg-Sausenberg , the son of his niece Agnes. After Heinrich's early death (1318), the brothers Rudolf II and Otto jointly took over the government of the united dominions of Rötteln and Sausenberg and the seat was moved from the small Sausenburg to Rötteln Castle. From this point on, they referred to themselves as Margraves of Hachberg, Lords of Rötteln and Sausenberg, or Margraves of Rötteln for short .

Late Middle Ages

From reconstructions it can be concluded that the formation of Lörrach was determined by its road location. The old Wiesentalstrasse runs along the valley floor, which used to lead from Basel via Riehen to Schopfheim - in today's city center it coincides with Basler Strasse and continues after a slight curve behind the Lörrach market square in Turmstrasse. At the market square, it meets Wallbrunnstraße at right angles, which leads towards Dinkelberg. Today's roads are essentially based on the old traffic routes. At that time there was a castle south of today's Herrenstrasse, after which the Lords of Lörrach named themselves. The Lörracher Burg was a moated castle like those in Inzlingen , Grenzach and other places. It was on the eastern edge of the meadow and had existed since the beginning of the 14th century. It was a simple residential building with a double wall ring and a moat in between. A pond to the south of the castle was drained after 1595. The village of Lörrach was bordered to the north by today's Teichstrasse. The oldest village center was probably at the foot of the Hünerberg in Ufhabi , along Wallbrunnstrasse east of the market. There was also the Viehmarktplatz (today Engelplatz). The area in between was apparently not completely built up. It can be assumed that this situation lasted through the entire Middle Ages, as only a few structural extensions were made during this period.

The 14th century was marked by changing rulers and disputes over inheritance. It is known that castles were broken up into many parts and shared by ganerbe . The castle truce - a contractual agreement between the individual castle owners - is one of the most complicated forms of document of that time. The Margraves Rudolf and Otto von Hachberg concluded such a truce with Luitold and his son Heinrich von Krenkingen. The dispute over Brombach lasted for many years until the Basel earthquake in 1356 also destroyed the castles of Brombach and Oetlikon (Friedlingen). Rötteln Castle is also likely to have been affected. However, the Brombacher castle was rebuilt and belonged unchallenged to the Hachberg rule.

In autumn 1332 an army from Basel besieged Rötteln Castle without being able to take it. The reason for this was that the margrave (presumably Rudolf II ) had stabbed a Basel mayor in the dispute. The reason for this dispute is not clear from the chronicle. Nevertheless, the Hachberger still enjoyed the sympathy of the Basel landed nobility, so that there were no lasting tensions.

In the second half of the 14th century, the Lords of Lörrach disappeared from the place. A part stayed in Basel as civil servants, another part took over the rule of Biberstein in the Bern area. After the Lords of Lörrach, the castle and the land belonging to it belonged to different owners. On March 28, 1638, the castle went up in flames, the remains of which were not removed until 1720. Several buildings were built on the former castle grounds: a large mansion granary and cellar, the court cooperage (today the three-country museum) and the Burgvogteigebuilding (today the main customs office).

On January 26, 1403 King Ruprecht of the Palatinate granted the Margrave Rudolf III. von Hachberg-Sausenberg has the right to hold a fair on the Wednesday before St. Michael (September 29) in the village of Lörrach and a weekly market every Wednesday. Since Lörrach was at the intersection of important trade routes, this market law was granted by Emperor Friedrich III in 1452 . has been confirmed of great importance.

During this time, neighboring Basel, to which the Margraves of Hachberg-Sausenburg had close ties, also developed. They owned a house on the Rheinsprung . In 1400 Basel became a free imperial city in which the guilds ran the regiment. From 1431 to 1449 the council took place there, which presented the city with supply problems. Participants from all over the empire and from Italy had to be fed, which led to a shortage and increase in the price of food. A harvest disaster in 1437 put an additional strain on the economy. At Easter 1439 the plague broke out, which raged in the overpopulated Basel and among the council participants. In August 1444, the troops of the French Dauphin Ludwig, the so-called Armagnaks , approached Basel, with whom the city took up battle. They also plundered in the Wiesental, withdrew from the city after the battle of St. Jakob an der Birs and invaded Alsace . In all of these events there was no mention of Lörrach or the margravial places. The few documents that exist from these years do not reveal anything about the times of the disaster. It is not clear from the donation and lease agreements whether they were made out of necessity or whether they were routine matters. In 1473 the Swiss began the defensive battle against Duke Charles the Bold of Burgundy . Markgräfler also took part in the Battle of Murten in 1476. The Markgräfler farmers gathered around May 1st in defense and arms as a "landscape" on the Sausenhard , the old rural community field near Mappach. In the so-called Swabian War of 1499 between the Roman-German king , later Emperor Maximilian I , and the Confederation, the peasants of the margraviate were also used in the battle of Dornach . The Swiss triumphed, which led to the peace in Basel on November 22 of this year . On July 13, 1501, Basel finally joined the Swiss Confederation. In 1521 the city renounced itself politically from the bishop; there was a pure guild regiment.

Early modern age

Reformation in the Markgräflerland

The oldest preserved churches in the Wiesental are next to the Schopfheimer church the church of Rötteln , which was first mentioned on September 7th, 751. It was founded in 1401 by Margrave Rudolf III. von Hachberg-Sausenberg rebuilt after it was destroyed by the Basel earthquake . According to the inscription, the tower of the Lörrach church dates from 1517. In 1736 the church was expanded and from 1815 to 1817 a new church in the style of Weinbrenner was added to the old tower. The Reformation in Basel was brought about in 1529 by Johannes Oekolampad . The 16th century was the heyday of the university, humanism , art, science and printing . The humanist Erasmus von Rotterdam taught at Basel University from 1521 and lived for several years in Basel, where he died in 1535 and was buried in Basel Minster . The Basel book printer Johann Froben also contributed to the Reformation by printing and selling Luther's writings .

Since 1102 the right to fill the Lörrach pastor's position was at the St. Alban's monastery in Basel. It passed to the Basel magistrate on April 1, 1529, going back to the Reformation regulations drawn up by Oekolampad . The first Protestant sermon was in Lörrach on 21 January 1556 by Ulrich Koch, from the Antistes the Basel Cathedral , Simon Sulzer was appointed, a student of Oecolampadius. Sermons and singing took place in the popular German language, no longer in Latin. With this sermon, the rule of Rötteln joined the Reformation on June 1, 1556. Since 1682 the evangelical pastors of Lörrach were also special superintendents of the diocese of Rötteln. The chapter and Latin school was on Rötteln; the later pedagogy was in Loerrach. The upper Wiesental ( Zell im Wiesental , Schönau in the Black Forest , Todtnau ) remained Catholic , which, like Stetten, had belonged to the front of Austria since the 14th century . During the Peasants' War in 1525, all monasteries were looted and some castles were conquered. During the reign of Margrave Ernst, the farmers occupied Rötteln Castle .

Thirty Years' War

The plague raged in 1610 and 1629. During the long years of the war, the population suffered from robbery and pillage by looting troops and brought themselves and their property to safety in Basel. From 1633 on, the repeated marching through of Spanish and other troops meant a serious plague. In 1638 there was the battle of Rheinfelden , in which Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar defeated the Imperialists. He had his headquarters in Brombach and occupied Rötteln. The Swedes captured Rötteln Castle; Loerrach Castle was destroyed by fire and not rebuilt. In 1634 the plague again claimed many victims in Lörrach. The number of inhabitants shrank sharply; In 1645 Lörrach only had 454 residents. The financial damage from 1622 to 1648 was also considerable; the Oberamt Rötteln put it at 610,290 guilders . During these years the margrave found asylum in Basel. In order to be able to pay the contributions to the French military, he was forced to sell Klein-Hüningen to Basel. Due to the looting, his subjects were no longer able to pay taxes. The Peace of Münster in 1648 also brought peace to the Markgräflerland. Switzerland was represented in the negotiations by the Mayor of Basel, Rudolf Wettstein . There the Confederation finally broke away from the German Empire . In the second half of the 17th century, the declining population of the margraviate and the Black Forest was refreshed by immigration from Switzerland.

City charter

Lörrach had acquired the privilege of holding a market in 1403, but its importance was not particularly great. In the shadow of the city of Basel, the town could not develop any further. The official authorities, the country writing department and the clerical administration resided on Rötteln. Lörrach itself had around 500 inhabitants in the middle of the 17th century.

Only when French troops destroyed the castle on January 29, 1678 as part of the Franco-Dutch War , did Loerrach come to the fore. The margravial authorities needed new accommodation, some of which they found in Basel and Lörrach. At the suggestion of Bailiff Reinhard von Gemmingen , Friedrich Magnus von Baden-Durlach granted Lörrach town charter on November 18, 1682 . The higher authority was the Landvogtei with its seat on Rheinfelderstrasse (today: Wallbrunnstrasse). On April 12, 1683, the margrave had a corresponding letter of privilege issued. However, as a result of constant war unrest, this city law did not come into effect and was forgotten. On March 26, 1755, the municipality of Lörrach asked the margravial state government again to grant city justice. Margrave Karl Friedrich renewed Lörrach's town charter on June 3, 1756 at the suggestion of Landvogt Gustav Magnus von Wallbrunn . On August 24, 1756, the new city privilege was publicly announced. The Lörrach letter of privilege comprised a total of nine points, including the right to a “mayor and six court and council persons” . The margrave also confirmed the city's coat of arms, "which this place has already chosen in the image of a Lörchen" and allowed "that she should lead a Lörche of gold in a red field" .

As a result of the city charter, new authorities and institutions had to be set up in the city. A gate tower (prison tower) was built from 1688 to 1691. The street name Turmstrasse is a reminder of this building, which was demolished in 1867. After the destruction of Rötteln, the city of Lörrach also became the seat of government authorities, the Upper Office (Landvogtei), the Special Office (Dean's Office) and the Chapter (Latin School). The two city centers, castle, church and the rural settlement of Ufhabi were connected to one another. In the years 1694 to 1697, the French architect Lefèvre drafted plans for a margraves' castle in Lörrach, but these were never realized. Instead, a margravial residence was built in Basel from 1698 to 1705 . After the city of Basel bought and remodeled the building, it was used as part of the Basel Citizens' Hospital . Since 1960 it has housed offices of the Basel University Hospital .

War of the Spanish Succession and the following years

Even after the Thirty Years' War Loerrach suffered repeatedly from armed conflicts. The peace of Rijswijk in 1697 gave hope for improvement. However, the situation in the region was difficult after the outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1701 because Bavaria sided with France and the Markgräflerland and Lörrach lay between the two allies.

During the War of the Spanish Succession, there was fierce fighting in front of the French fortress of Hüningen on the Rhine, as Hüningen was the exit gate for France. The French Marshal Claude-Louis-Hector de Villars intended to cross the Rhine with 20,000 men and occupied the Schusterinsel in September 1702. On October 14, the handle as Türkenlouis called Margrave Ludwig Wilhelm von Baden-Baden Villars on after the French had advanced already have their bridgehead at Friedlingen to Weil and the Tüllinger mountain. After Villar's cavalry had already triumphed on the plain, the margrave's infantry managed to put the French to flight in the battle of the Käferholz . There was no real winner. However, since the Imperial Army withdrew towards Staufen, the Markgräflerland was left to the French troops to plunder. A memorial on the Tüllinger Berg commemorates the battle of the Käferholz.

Both Weil and the surrounding villages of the Markgräflerland were destroyed. The Bailiwick of the Lords of Rötteln was responsible for the war debts. There is a war and military affairs file from Stetten , in which “war costs and beech nuts” are listed. The damage is estimated at 17,385 florins and 18 schillings. This included the cost of repairing the damage caused by arson, food supplies, hay, straw and wine.

Due to the border location with France, the arch enemy of the Habsburg Empire , Lörrach also had to bear the burden of war in the following years. In the War of the Polish Succession in 1735, French troops again advanced across the Rhine near Hüningen, demanding provisions from the inhabitants of the Wiesental valley and levying a war tax in all communities. The War of the Austrian Succession , which lasted from 1740 to 1748, did not spare Lörrach either. Although there was no destruction, the communities of the Markgräflerland had to provide the Austrians and French with provisions. Only the Second Peace of Aachen brought peace to the country for a few decades.

Revolutions and coalition wars

“For a few weeks now, people from Alsace have been moving into the country in droves, in Lörrach and around Lörrach. They give 10 and 12 chunks of food every day . It should be aristocrats who want to overthrow the democratic national assembly in Paris and the whole constitution again and help the king to gain respect and power. "

Pastor Herbst's note summarizes the situation in the country at that time. After the storming of the Bastille during the French Revolution , the nobility emigrated, who first stayed in Alsace and later fled across the Rhine. Imperial dragoons moved into Lörrach in April 1791, fearing the French invasion. After the French declared war on Austria, warlike times began again for Lörrach, as the margrave was connected to Austria and Prussia. In 1793 the imperial troops suffered a defeat at Haguenau . The population of Lörrach was again affected by the burden of war. After the Treaty of Basel in 1795, the Baden Oberland was defenseless at the mercy of the French armies. The governor of Lörrach and later the first minister of Baden, Sigismund von Reitzenstein , was sent to Paris as a Baden negotiator to negotiate a separate peace. In the negotiations he got the promise for the later territorial expansions of Baden . In the first phase of the war from 1792 to 1796 there were always troops in Lörrach that had to be fed by the population. For about three quarters of a year there were one hundred cuirassiers , for two days Lörrach even had to take on 16,950 men from four regiments. The daily rate for meals was mandatory. Officers received six times that amount, colonels twelve times and generals twenty-four times the rate of a soldier. At that time Lörrach had 1,700 inhabitants.

The margraviate of Baden became a theater of war in 1796 during the First Coalition War. Under General Jean Victor Moreau , the French troops swarmed at Hüningen and Kehl . 2000 men from Lörrach were supposed to compete to build the hill. When the contribution was not delivered in time, the land clerk and councilor Christian Gottlieb Michael Hugo was put in prison. Loerrach became the French headquarters for a few days. Through the Wiesental and the Höllental , Moreau was able to advance to the Danube , was defeated by the imperial troops near Ulm and Würzburg in September and returned to the Rhine Valley on October 15th while fleeing. On the way to Hüningen there was a last battle on October 24, 1796 near Emmendingen and Schliengen between Moreau and the Austrian Archduke Karl . The French who fled and plundered via the Kander and Wiesental reached Loerrach. In Tüllingen, 40 to 100 soldiers were housed in each quarter. The soldiers' constant consumption of wine ensured that many Lörrach inns began brewing beer .

All around the Hüningen Fortress, an attack was being prepared. From the Markgräflerland to the Fricktal , men were recruited for several days to ski jumping. A first attack by the Austrians failed with great losses on November 30th, 1796. At the time of the siege, Archduke Karl had his headquarters in what was then the pedagogy in Lörrach, today's three-country museum. The French gave up their fortress in Hüningen and Napoléon relocated the fighting against Austria to Italy in 1797. Archduke Karl withdrew from Loerrach on February 3rd of that year.

In the Second Coalition War from 1799 to 1802, the lower Wiesental was again occupied by French troops. In 1801 30,000 infantrymen and 12,000 horses were stationed in Lörrach. Infectious diseases also burdened Lörrach. However, the state of Baden benefited enormously. Napoléon raised it to the electorate in 1803 in the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss and in 1806 to the Grand Duchy. At the end of this development, the Grand Duchy had a closed national territory that was more than twice the size of the Margraviate . The consideration provided in the form of military alliances made Baden, and thus Lörrach, a hostile foreign country from a German perspective. Only after the Battle of Leipzig lost by France in 1813 Grand Duke Karl Friedrich broke away from Napoleon. During the French campaign in June 1814, Lörrach was the headquarters of Field Marshal Karl Philipp zu Schwarzenberg , who spent the holidays there with nine generals, two colonels and a 3850-strong troop on Christmas 1813. Until the middle of 1814, the Russian Tsar Alexander I , the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III. , the Austrian Emperor Franz I and Prince Wilhelm of Prussia quartered in the Lörrach restaurant Krone . Other generals, colonels and officers stayed in the Hirschen . In one month alone Lörrach had to provide food for 161,646 members of the army. At that time the city had 3000 inhabitants. In addition to catering, the city had to finance repairs to broken cannon axles, candles for the accommodations and writing materials for the military offices. The computer of the city of Lörrach counted a total of 410,917 men and 54,118 horses billeted in Lörrach for the period from November 22nd, 1813 to June 1st, 1816.

In the second half of the 18th and first half of the 19th century, the most important Alemannic dialect poet Johann Peter Hebel worked in Lörrach. Leebel's place of birth is given as Basel, but he is said to have been born surprisingly on May 10, 1760 during a visit to Pastor Nutzinger's parents at Gasthaus Bad in Hauingen. Regardless of whether he was Lörrach's son or not, he is closely connected to the city. On May 19, 1783, Hebel moved to the so-called Pädagogium , the former Latin school in Lörrach, where he taught as vicar of the Praezeptorats until November 2, 1791. Hebel described his time in Loerrach as the most beautiful of his life.

Modern times

Road to industrialization

Iron ore was mined in Kandern as early as Roman times . Iron smelting was resumed in the 9th century. Silver and lead mining was carried out in the Münstertal , in the 11th century also in Todtnau . Silver mining was stopped again in the Thirty Years War. In 1680, Zurich manufacturers had raw cotton spun by hand in communities in the Hotzenwald and upper Wiesental . In 1758, Zell im Wiesental was the center of the Upper Austrian textile industry . In 1828 the Wiesental's first mechanical cotton spinning mill was set up in Todtnau.

Paper production and letterpress printing were the most important industries in Basel in the 15th century. In 1467 Bartholome Pastor was the first papermaker to move from Basel to Lörrach. From the end of the 16th to the beginning of the 18th century, the Lörrach paper factory, which was closed in 1745, was important. Around 1700 Lörrach had three paper mills , two brick factories , a fulling mill with dyeing, a fulling mill and a powder mill. Landvogt Ernst Friedrich Leutrum von Ertingen promoted agriculture. Leutrum left Loerrach in 1748; Gustav Magnus von Wallbrunn (1702–1772) followed him as governor. He encouraged the settlement of new businesses and thus took into account the age of mercantilism . The renewal of the town charter in 1756 attracted further industries. On August 27, 1753, Johann Friedrich Küpfer received the privilege of founding an Indian (cotton) factory. Until 1802 this received state subsidies and in 1808 it was sold to the two large industrialists Merian and Koechlin. In 1857 the textile company Koechlin-Baumgartner & Cie . Today the Lörrach-based company operates under the name KBC Manufaktur Koechlin, Baumgartner & Cie. GmbH .

In 1742, the Huguenot Samuel August de la Carriere from Basel received permission to open a printing house in Lörrach. In addition to information sheets with advertisements, a German-language Bible in Martin Luther's translation was among the printed products. In 1753, Bosque from Strasbourg opened a tobacco factory. Since it could not hold up, the building changed hands in 1761 for 550 Louis d'or and the chapter school (pedagogy) moved into the former factory building.

When the state of Baden entered the German Customs Union in 1836 , economic life took off again. In the middle and end of the 19th century, numerous new factories were founded in Lörrach, including a cloth factory in 1837, the later Vogelbach cotton spinning mill in 1847, the Kern machine factory in 1885, the Suchard chocolate factory in 1885, the Kaltenbach machine factory in 1887, the Lasser brewery in 1850 and the Reitter brewery in 1864 .

The Goldene Apotheke Basel was founded as early as 1638 as one of the first pharmacies in Europe. In 1846 the Basel doctor Dr. Emanuel Wybert took the recipe for a cough suppressant from a study trip to America. His friend Dr. Hermann Geiger, then owner of the pharmacy, sold the so-called Wybertli pastilles for the first time this year during a flu epidemic . Due to the positive response from 1906 onwards, Dr. Hermann Geiger and his brother Dr. Paul Geiger in St. Ludwig (today St. Louis ) in Alsace under the name Wybert . From 1944 on, GABA specialized in oral and dental hygiene and brought out the aronal toothpaste. After the Second World War , Ernst Ludwig Heuss , the son of the former Federal President Theodor Heuss , became head of Wybert GmbH in Lörrach, and later of GABA AG in Basel.

Baden Revolution

The developing economy required the construction of workers' houses. The cityscape began to change rapidly. The hospital foundation and the lever park are two examples of emerging patronage . Around 1808, many classicist buildings were built in Lörrach, including the synagogue, the town church in the center and the Fridolinskirche in Stetten. During this time, however, changes did not only take place in the construction industry. In the new Baden, which was linked from 1806 by so-called organizational edicts , a uniform city law had to be created in view of the variety of city types . For example, the mayor was appointed by the state authority. The city council, which also exercised the function of the city court, had power together with the mayor. The city of Lörrach, as one of the wealthier communities, had been granted the appointment of its own council clerk. The city council at that time was not elected, but complemented itself through so-called co - optation . This basically little modern community structure was fundamentally changed in 1821 by a provisional law and in 1831 by a special law by the Baden municipal ordinance. This was valid until 1890 and envisaged Lörrach as a civil parish in which non-citizens were excluded from participation. It was not until 1890 that the law for Lörrach provided full equality for all residents. The community assembly of all local citizens elected the mayor and the citizens' committee, from which the city council emerged. In the municipal code of 1831, an equal voting right was stipulated. Under the influence of the Baden Revolution of 1848/49, the state of Baden switched to municipal three-tier voting rights , which were graded according to tax revenue.

First Baden Revolution

After the Hambach Festival in 1832, liberal demands were also made in Lörrach. Numerous meetings and uprisings, such as in September 1847 and March 1848 in Offenburg or February 1848 in Mannheim, followed. Demands of the revolutionary forces such as freedom of the press, freedom of conscience, freedom of teaching and personal freedoms were paramount. The Baden Constitution of August 22, 1818 was considered to be one of the most modern constitutions in the German Confederation , but it did not contain any provisions on popular sovereignty, central freedoms and independent jurisdiction . Friedrich Hecker and Gustav Struve proclaimed the republic in Constance . The next day a small group formed, which moved along the Rhine plain towards the residential city of Karlsruhe. Their destination was Schliengen , where the then terminus of the Mannheim-Basel railway was located. On April 20, 1848, Hecker called on the city of Loerrach to support the revolutionary movement. The town council refused. Of the 276 community citizens entitled to vote, 198 appeared at the community meeting and 142 voted not to participate in the survey. Only three or four men joined the procession that marched on towards Tumringen. Since the participants were ill-equipped and fragmented, the defeat was foreseeable. Under the orders of the innkeeper Joseph Weißhaar from Lottstetten , 800 insurgents, coming from Lake Constance , marched through Lörrach on the same day to rush to the Hecker train to help. Hecker's troops were defeated in the battle on the Scheideck near Kandern , in which General Friedrich von Gagern was shot. Around 1000 irregulars met around 2000 Hessian and Baden government soldiers on the Scheideck . The Stuttgart poet Georg Herwegh crossed the Rhine with his republican German Democratic Legion and was defeated near Dossenbach on the Dinkelberg , Franz Sigel on April 23 in Günterstal near Freiburg. The troops of the Grand Duke of Baden took Freiburg on April 24; Hecker fled first to Switzerland and then to North America.

Second Baden Revolution

→ Main article: Struve Putsch

The second attempted coup was made by Struve ( Struve-Putsch ) from Basel, where he had fled to avoid the authorities' access. On September 21, 1848, he arrived in Stetten and on the same day, with the help of the Stetten vigilante, at around 5:30 p.m., he marched to the town hall in Lörrach on Wallbrunnstrasse. The red flag was put on the market fountain, red-painted wooden panels with the black and gold inscription German Republic were attached to the office and post office . Already in the afternoon, the Loerrach vigilante group, under the orders of Captain Markus Pflüger, met to give Struve support. The grand ducal officials were arrested, mayor Carl Georg Wenner and the local council were called to the town hall. Struve gave a speech from the first floor of the town hall and proclaimed the republic. He proclaimed the martial law , promised the abolition of all taxes and assured numerous social measures. An "Appeal to the German People" with a provisional government program, an instruction for the mayor and various messages from the headquarters in Lörrach were printed on leaflets in the Gutsch printing works confiscated by the revolutionaries and distributed among the population. All men between 18 and 40 years of age were obliged to take part in the Struvezug to Karlsruhe. For four days, Loerrach was the capital of the Struve Putsch, in a sense the “seat of government”. The Lörrach doctor and politician Dr. Eduard Kaiser described the attempted coup from a local but also from a general point of view and said: “Half Schinderhannes, half monkey theater”. On September 24th, Struve's 1,000-strong contingent suffered a defeat near Staufen by the government troops under General Hoffmann . Struve was captured in Wehr and brought to Rastatt . A large contingent of troops was quartered in Lörrach under Colonel Rotberg. This meant that the second attempt at a revolution had failed. The historian Hubert Bernnat sees the main reasons for the failure of the Struve Putsch in the fact that, despite his demands, Struve received no support from the underprivileged sections of the population and, on the other hand, Struve's utopian idea of socialism was mixed with blind radicalism and actionism.

Third Baden Revolution and opening of the railway line

During the third revolution in Baden, a mutiny broke out among the troops in Lörrach and the surrounding area on May 11, 1849 . On May 12 and 13, the Lörrach garrison marched to Kandern and from there via Müllheim to Freiburg and Karlsruhe. After the quick defeat of the irregulars in July 1849, the revolutionaries fled back to Basel via Lörrach. On July 10th, the Prussian occupation troops moved from Binzen to Lörrach.

In the same year, the Baden main line was completed shortly before the Swiss border and in 1862 the line from Basel to Lörrach and Schopfheim opened in the presence of Grand Duke Friedrich. With the completion of the hydropower plant in Rheinfelden in 1899, the Wiesentalbahn was electrified in 1913 as the first railway line in Baden and one of the first in Germany. It was also the first private railway in the Grand Duchy of Baden. In 1867 the Catholic Church of St. Boniface was built. At that time Lörrach had around 6000 inhabitants. Lörrach was largely spared from the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, but was the scene of a successful deception maneuver ( deception with the beetle wood ), which was staged on the Tüllinger Höhe. The community meetings took place in the so-called parlor tavern until the middle of the 18th century. In 1756 the town hall in Wallbrunnstraße was rebuilt and in 1869/1870. Since 1927 the town hall has been located in the converted Villa Favre at the train station.

The 20th century

The advancing industrialization let the population of Lörrach increase further. In 1900 it hit the 10,000 mark. In 1907 Wilhelm Schöpflin founded his company in Haagen, which in 1930 became the well-known mail-order company. The village of Stetten was incorporated on April 1, 1908, thereby increasing the population of Lörrach to 15,000, the area of the district had grown from 752 hectares to 1213 hectares.

In 1906 the 27-year-old assessor Erwin Gugelmeier (1879–1945) was elected mayor of Lörrach. Gugelmeier, who was previously the town councilor in Pforzheim , was the first mayor to come from outside Lörrach. He held this office for almost 21 years until he was elected to the Reichstag in 1927 . He maintained particularly good contacts with Riehen and Basel. The largest economic project of the time was the expansion of the municipal gas works to meet the increased demand for gas due to the introduction of street lighting.

World War I and hyperinflation

The upswing was ended by the First World War , which broke out on August 1, 1914 . In the courtyard, which was used as a barracks square, the men fit for military service were mustered, dressed and armed. The Lörracher conscripts living abroad also had to report. After the French army had made the breakthrough to Mulhouse , there were also some unrest in Loerrach. The fighting shifted to the north, so that the front in the Vosges froze to a trench warfare. Mayor Gugelmeier negotiated with the Basel government council to enable children and women to take refuge in neutral Basel if Lörrach were shot at. In 1915 Lörrach suffered deaths from enemy air raids . On the Tüllinger Berg, a Hindenburg line was expanded to defend the city and in 1916 an additional hospital was set up in the secondary school. During the First World War, Lörrach and the surrounding suburbs suffered a total of 813 casualties.

For almost a year, from November 1920 to July 1921, the Lörrach airfield was in operation in the Tumring district . On November 15, 1920, the first mail flight, which opened the then Frankfurt am Main - Karlsruhe - Lörrach line and is considered a milestone in the history of air mail , left him. The Versailles peace treaty forced Loerrach to destroy the airfield and all aircraft.

Even after the end of the First World War in November 1918, the situation for Loerrach did not improve. As early as 1913, the scarcity of raw materials had plunged the region's textile industry into a deep crisis. At the end of 1914, the city already had around 1,000 unemployed. The far-reaching structural changes caused by the war put Lörrach's economy at risk. The control and centralization offices were in Berlin , and the factories on the border were in danger of being shut down due to a lack of allocation quotas . In contrast, the border situation in Switzerland and France was able to provide some relief. In the course of the November Revolution of 1918, a strong political radicalization took place in the left-wing camp, which had a stronger effect in Lörrach than in other Baden cities. Significant for this was an assassination attempt on the then Lord Mayor Gugelmeier on the evening of March 4, 1919.

The social situation worsened and the currency began to decline in August 1922. In January 1923, French and Belgian troops moved into the Ruhr area because of allegedly backward reparation payments ( occupation of the Ruhr ). Just a month later, French troops marched into Baden and took possession of Appenweier , among others . This interrupted the important connection on the Rhine Valley route between Karlsruhe and Basel. The announcement of passive resistance by the German government on January 13th further accelerated the galloping inflation . In the last week of August 1923, a construction worker in Weil am Rhein- Leopoldshöhle earned 985,000 marks an hour. A kilo of rye bread cost 414,000, a kilo of pork 4,400,000 marks. A curious advertisement in the Oberbadischer Volksblatt appeared on September 7, 1923: “The man who is said to have received the check for $ 10 with a little over 3 million marks at the cash desk of the local Reichsbank last Tuesday was asked to report because, according to the general opinion, he should have received around 170 million marks that day. ”However, that was only the beginning of inflation. At the end of this development, a tram ride from the train station to the border in Loerrach cost 290 million marks, and at the end of October the city granted the consumer association a loan of 10 trillion marks to purchase potatoes. The communities printed their own emergency money and much was only available in kind or in foreign currency. Falling wages and rising food prices led to malnutrition and poverty among the population. In Baden, the first unrest began in the first days of September, first in Rheinfelden , in Freiburg on the 12th and in Lörrach on the 14th. The number of job seekers rose from 200 to 1,600 by the end of 1923.

Time of the Weimar Republic

These developments led to increased social unrest in Lörrach. The city authorities were called upon to pay more attention, as it was also seething in the Loerrach underground at this time. The climax was the September riots in Lörrach in 1923 . On September 14th, workers were mobilized on the streets of Lörrach and in the Wiesental. The deployment of the security police prevented a further escalation of the civil war-like conditions. The results of these days were three dead, many injured and several hostage abuse.

The economic difficulties did not stop at the authorities and the administration. Financing overdue projects became increasingly difficult. There was no new building for the elementary school in Stetten, the construction of a new hospital was imminent. The funds were just enough for the construction of the swimming pool. The city administration had to postpone the actually unavoidable project of the new town hall building and find emergency solutions. The number of investments with the help of outside capital and thus Loerrach's debt increased considerably between 1923 and 1927. The term of office of Mayor Dr. Heinrich Graser (1927–1933) rated defects management. Due to the tight financial leeway, improvements in traffic conditions were postponed into the future, such as the construction of the duty-free road . The 1930/1931 draft budget was largely characterized by a decline in tax revenues and an increase in consumer spending. It was impossible to carry out major construction projects as much of the tax revenue had to be used for general welfare. Since November 1929, unemployment in Lörrach remained at 450, in September 1930 517 unemployed were registered.

The political polarization in the autumn of 1930 became clear in political discussions and in the election results. The NSDAP began to gain in importance. In the Baden state elections in 1929, Hitler's party grew significantly. In Lörrach the NSDAP received 115, nationwide it won 65,121 votes and thus six seats in the state parliament. Nevertheless, Loerrach remained the prime example of a medium-sized town in which political radicalization was evident from both the left and the right. The introduction of the city drink tax was approved by the municipal council in September 1930, but was prevented by a citizens' committee. At the first citizens' committee meeting after the municipal council elections on December 29, 1930, there were tumultuous scenes, police operations and, with the exclusion of communist city councilors, a tight casting vote for the introduction of the beverage tax. The budget would not have been more balanced without this tax; a possible city supervision would have meant a temporary end to Lörrach's self-government.

time of the nationalsocialism

The local branch of the NSDAP in Lörrach had existed since 1922. However, it found it difficult to gain a foothold during the 1920s of the Weimar Republic , although there was anti-parliamentary propaganda in Lörrach with the German national-folk magazine Der Markgräfler by dialect poet Hermann Burte . With the death of Gustav Stresemann in October 1929 and the economic consequences of the New York stock market crash on October 25, 1929 ( Black Friday ), the influence of the National Socialists increased significantly. In the 1928 Reichstag election in Lörrach, the NSDAP received just 57 votes. In the Protestant rural communities in the Lörrach area, however, she has already achieved high results. In the fall of 1930 the local branch of the NSDAP had only eleven members. Bad organization, debt and unpaid bills led to their dissolution. Reinhard Boos helped it to flourish by founding a new company. Boos stood up for the party with great commitment. The number of members, who came from all strata of the Lörrach population, rose to 376 by the end of 1932. The Nazis' seizure of power in 1933 brought Boos the post of mayor, which he held until 1945. From 1931 to 1938 he also held the position of district leader . In addition to the NSDAP, the Sturmabteilung (SA) gained in importance and engaged in the first recorded night-time brawl with supporters of the KPD in June 1931. With the daily newspaper Der Alemanne , the National Socialists of Oberbadens installed a propaganda organ that appeared in Freiburg. Reprisals began against members of the KPD. On May 1, 1933, a flag of the Iron Front was burned, which Boos justified with the fact that the entire Lörrach recognized the National Socialist movement. A little later the KPD was banned completely and in April 1933 ten political prisoners were taken to the concentration camp . Newspapers from the neighboring foreign city of Basel were banned in Lörrach.

After Germany refused to pay further reparations , the Wehrmacht was founded in 1935 and occupied the demilitarized zone on March 7, 1936 (occupation of the Rhineland ). Loerrach also became a provisional garrison town. Soldiers were present at the celebration on May 1, 1936, and the Hitler Youth held public air raid exercises at the station. On October 18, 1936, a major National Socialist event took place in which the then Gauleiter of Middle Franconia, Julius Streicher , primarily attacked the Catholic Church and especially the then Archbishop Conrad Gröber as a person. Boos propagated the city of Loerrach as the center of a greater Loerrach area. Boos' goal was to strengthen Lörrach so that in the foreseeable future it could outstrip the city of Basel, which had 160,000 inhabitants at the time. The incorporation plans at that time included Brombach, Haagen, Tumringen and Tüllingen. The district administrator, who strongly supported Boos, even wanted to go a step further and also incorporate Weil, which had a population of 8,000 at the time. However, most of the proposals met with opposition. At the end of these efforts it remained with the incorporation of Tumringen and Tüllingen, which was completed on October 1, 1935.

After the beginning of the Second World War , Boos was appointed Gauredner and had ideas about a border adjustment in the southwest corner , especially during the triumphant frenzy because of the allegedly successful large offensive Operation Barbarossa . He summed up:

“The Führer decides what will happen to Switzerland. Above, opposite the Swiss city of Basel - and that is probably the wish of the entire border population - we hope that the arbitrary political borders, which must be addressed as Polish, will be recognized as completely intolerable in the future and will be removed accordingly. "

Boos wanted to distinguish himself as a thought leader with these views, after he had already encountered opposition from within the party with his ideas for the greater Lörrach area.

Although Lörrach was geographically far from the war fronts, the traces of the war, which had already been revealed before it began, could also be felt in the Lörrach area. The border to Basel was closed and mined. During the French campaign, the evacuated population jammed in the market square. Construction vehicles have been transporting material from the Isteiner Klotz for the Westwall bunker since 1937 and Adolf Hitler visited Kirchen and the mountain ridge near Lörrach, used as a fortress, on May 19, 1939 . From June 16 to 18, 1940, railway guns fired from Lörrach into the Belfort area . The French counter-attack left Haltingen and the surrounding villages to rubble and ashes. On April 24, 1945, French tanks were standing on the Lucke pass . One of these tanks was shot down from Brombach. This was one of the last acts of war that ended with the occupation of Lörrach by the French. After a hopeless defensive battle together with the Volkssturm on April 24, 1945, Reinhard Boos was removed from his office by the French and Josef Pfeffer was appointed acting mayor. In the years 1943 to 1945 there were isolated bombings. In 1945 there was a bomb attack on Brombach. Nevertheless, the city was largely spared from destruction. At the end of the war, a total of 1792 men from Lörrach, Stetten, Tüllingen, Tumringen, Haagen, Hauingen and Brombach had died.

On January 2, 1940, the Cologne cyclist Albert Richter was killed in Lörrach prison . The official version was suicide , but he was allegedly murdered by the Gestapo . In 2010 a street in Lörrach was named after him.

Persecution of the Jews at the time of National Socialism

→ See also: Jews in Lörrach

Mayor Reinhard Boos, who was seen as a despiser of religion, not only had an anti-Semitic attitude in accordance with Nazi racial doctrine, but was also particularly hostile to Judaism as a religion. Many then living in Loerrach Jews already fled in the " seizure of power " Hitler in 1933 in Switzerland. In 1935 the local Jews lost their civil rights as a result of the Nuremberg Laws . November 9, 1938, known as the Reichskristallnacht , brought the end of Jewish business life in Lörrach as well. Between 30 and 40 men, including the then head of the municipal works yard and his servants, gained access to the approximately 130-year- old synagogue and smashed the facility. The devastated synagogue had to be demolished later. The city tried to put the destruction and the subsequent demolition into perspective by presenting the state of the roof structure as in need of renovation anyway.

In 1940 the Jewish community was asked to cede the property of the old Jewish cemetery to the city. The reprisals culminated on October 22nd, 1940 in the so-called Wagner-Bürckel-Aktion , in which more than 6,000 Jews from Baden, the Palatinate and Saarland were deported, including the last 50 Jews from Lörrach. They were taken to the French internment camp in Gurs .

Post-war years until 1960

On May 2, 1945, the French occupying forces appointed Joseph Pfeffer as mayor of the city of Lörrach. Immediately after the war, the provisional city administration had to ensure that the city population received assistance. From soldiers confiscated apartments households were from Requisitionsamt supplied with home furnishings. Generous food donations came mainly from neighboring Switzerland, which alleviated the hardship of the first post-war years. The aid organization of the Protestant Churches in Switzerland, the Swiss Workers' Organization, the Swiss Caritas Association, Christian emergency aid and the Swiss Red Cross took part in the relief effort. The drought year of 1947 worsened the situation, so that material help was still urgently needed in Lörrach.

Mayor Pfeffer initially had to do without a city council because this body was officially not allowed to exist. It was not until 1946 that political forces formed again, so that Pfeffer was elected by the local council on September 22, 1946. In the course of parliamentary work, a Baden municipal ordinance was passed in 1948, on the basis of which local council elections took place on November 14, 1948 and mayoral elections on December 5. Pfeffer did not run for reasons of age and so on December 5, 1948, the SPD candidate Arend Braye was elected mayor.

The post-war years were marked by the arrival of refugees and displaced persons and a disproportionate growth in the urban population. In order to offer new living space, the Nordstadt was founded as a new quarter from a fallow land north of the city center . The relatively minor war damage in the Lörrach area also attracted many job seekers. This was related to the shortage of labor, especially skilled workers, which was felt in the late 1950s. This shortage was exacerbated primarily by the increased number of cross-border commuters , who usually had better earning opportunities in neighboring Switzerland. This aspect had a pull in the near and far surrounding area. From around 20,000 residents after the war, the number grew to over 30,000 by 1960. Around 7500 of them were displaced persons and refugees from the German eastern areas and from the GDR area . The number of foreigners also increased. From 1950 to 1960 it almost doubled to 1055. Due to the sharp rise in the need for living space, Wohnbau Lörrach was founded in 1956 .

The political landscape in Lörrach shifted in the municipal council elections in 1959 in favor of the CDU , which with six seats was as strong as the SPD . The SPD has always had a good position in the city. The local association Lörrach, founded in October 1868, is only five years younger than the party as a whole and can therefore look back on a long tradition. In August 1960, the 70-year-old Lord Mayor Braye died unexpectedly. A new mayor was elected on November 13th. With 57.70 percent, politician Egon Hugenschmidt , who is close to the CDU, was able to unite the most votes in the first ballot.

1960 to the end of the century

Due to the rapidly growing city, the Salzert settlement and the Bühl in Brombach were created in the 1960s . The housing shortage was due to both world wars. In the economically poor 1920s and during the Nazi era, the city government failed to create enough living space. In February 1960, the Salzert development plan for the satellite city was approved. To the east of Stetten , around 23 hectares of land on a mountain have been released for development. On April 16, 1963, construction began on the first single-family house. After about three years, over 2000 people lived on the Salzert. The project was initially very controversial and the exposed residential area on a mountain with originally only one access road was considered utopia by the people of Lörrach. The cheap land price of five marks per square meter made it possible for many families to get their own home or rented apartment cheaply.

The general traffic plan drawn up in 1964 by Professor Schächterle from Ulm was the basis for further urban planning. He envisaged the city bypass of the B 316 from the Lucke to Waidhof as well as the construction of the B 317 from Steinen along the meadow with continuation as a duty-free road from the border in Stetten to Weil am Rhein. This plan was on May 19 in 1964 by a town meeting approved. Lörrach created the basis for urban planning back in 1955 through the zoning plan with the neighboring communities of Brombach, Haagen and Hauingen. This was expanded to include the area of the municipality of Inzlingen and came into force in 1973. Extensive renovation measures began in Lörrach as early as the 1960s. Disused factory areas such as that of the former Conrad spinning and weaving mill offered space for redesign. New living space was created not only on the periphery, but also in the city center when the high-rise building on the market square was completed in 1973. The planning of a pedestrian zone could only be tackled relatively late because the central Turmstrasse was also the main road. The federal road administration only agreed to a downgrade to a municipal road when the western one-way ring was built. At the same time, the construction of the A 98 motorway from the Lucke to Waidhof began, thereby ensuring the bypassing of the town. Under Mayor Hugenschmidt it was decided in 1975 to implement the pedestrian zone concept. The first section was the redesign of Turmstrasse in 1978.

Haagen was incorporated into the rapidly growing Loerrach on January 1, 1974. A year later, today's city of Lörrach was formed by the merger of the city of Lörrach with the two communities Brombach and Hauingen. The core city now includes three urban and three districts. The districts have their own local administration with a local mayor . In order to better meet the increased needs and requirements of Lörrach's administrative operations, it was decided to build a modern high-rise building on the site of the former Villa Favre, which had served as the town hall since 1927. The 17-storey, dark green skyscraper made it possible for the first time to unite all city offices in one building. Mayor Hugenschmidt inaugurated the new town hall on June 13, 1976 .

On March 27, 1979 the Lörrach city government decided on the plan to hold the 4th State Horticultural Show 1983 (→ State Horticultural Show 1983 ) in the city. It was decided to convert the large area of "Grütt" between the Lörrach core town, Tumringen, Brombach and Haagen, which was previously used exclusively for agriculture and was now wasteland, into a sports and leisure facility. Further deep wells for the Lörrach water supply urgently had to be developed on the approximately 51 hectare property . In addition to the design of a landscape park, securing the water supply by acquiring the protected areas, integrating the roads (A 98, B 317) and expanding and supplementing the sports facilities and the campsite were the primary goals. On March 20, 1982, a large tree-planting campaign took place as part of the large-scale project with the help of the Black Forest Association , Naturefriends and other volunteers. The rose garden was completed in summer. On April 15, 1983, in the year of the 300th anniversary of the city law, the state horticultural show was opened. The event, which lasted until October 16, 1983, was attended by around one million interested people.

Rainer Offergeld , who had been Federal Minister for Economic Cooperation in the Federal Cabinet under Chancellor Helmut Schmidt , replaced Egon Hugenschmidt as Lord Mayor in 1984. During Offergeld's tenure, the expansion of the pedestrian zone continued. In 1986 a new traffic concept was gradually implemented in the city center. In a first phase, Basler Strasse was closed to public transport from the intersection with Herrenstrasse. Tumringer Strasse and Teichstrasse followed with a time delay. In a later section, the street and sidewalk were dismantled and the areas paved flat. The new pedestrian zone in the city center was officially inaugurated in 1991. Along the new center, but also a little outside of it, various sculptures have been set up at 22 stations over the years . Works by Stephan Balkenhol , Bruce Nauman and Ulrich Rückriem can be found on this so-called Lörrach Sculpture Trail . On April 2nd, 1995 Gudrun Heute-Bluhm was elected as the new mayor. It promoted the expansion of the Loerrach city center. The most important construction projects in her term of office , which will last until 2014, include the construction of the Burghof , which replaced the old town hall in 1998 and serves as a cultural and event location, and the Lörrach innocel innovation center .

The 21st century

In 2000, an industrial park was created that offers 12,000 square meters of commercial space for companies specializing in information technology and life sciences to buy or rent. In 2002, the city celebrated the city's 900th anniversary with a supporting program spread over the year. In the same year Lörrach was the first German municipality to be awarded the Swiss energy label “ Energiestadt ” and in the following years it received three gold awards, the European Energy Award . The basis for this is the planned and implemented measures to transform the city into a climate-neutral municipality by 2050. A showcase building is the Niederfeldplatz residential area , which is the first CO 2 -neutral residential complex in Germany.

Since July 2007, part of the Lörrach University of Cooperative Education , which was founded in Lörrach in 1981, has been based in the innocel . In September 2007 the Straße der Demokratie was opened, a holiday route that runs from Frankfurt am Main and Neustadt an der Weinstraße to Lörrach.

On November 9, 2008, in the presence of the then Prime Minister Günther Oettinger, 70 years after the destruction by the National Socialists, the new Lörrach synagogue was opened in the city center. The design of the cube-shaped building comes from the Lörrach architects Wilhelm, Hovenbitzer und Partner.

On September 19, 2010, there was a rampage at St. Elisabethen Hospital in which three people were killed and 18 others were injured. The internationally acclaimed act sparked another nationwide discussion about the tightening of the German weapons law.

One of the largest construction projects for decades is the planned construction of a central clinic on the northern edge of the city area. For the development of the construction area, the traffic connection is to be optimized with several measures. In addition to the relocation of the L138 road, a new S-Bahn stop for the S-Bahn should be built and the connection to the B317 federal road changed. The current (as of March 2018) schedule stipulates that construction will start in 2020 and the opening of the clinic will be pursued for 2025. For the clinic, whose location is intended for the Entenbad-Nord district, an area of around 7 to 8 hectares and around 700 beds is to be developed. The construction costs including the medical technology are estimated at around 239 million euros.

After the demolition of the old main post office in a central location on Bahnhofsplatz in Lörrach, the Lö , a residential and commercial building, has been built on the old post office area since May 2019 . In addition to the 13,000 square meters of commercial space for retail, it will accommodate 59 apartments and include underground parking for 192 vehicles. Completion of the building complex is scheduled for 2020.

A striking, seven-story building has been under construction in the corner area of the “Weberei Conradi” area since 2019. The building with underground parking for the adjoining residential area is to become the new second location of the Lörrach district office.

See also

literature

General representation

- Otto Wittmann , Berthold Hänelet: Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture . Issued in memory of the privilege granted 300 years ago on November 18, 1682. Ed .: City of Lörrach. City of Lörrach, Lörrach 1983, ISBN 3-9800841-0-8 .

- August Baumhauer: Overview of the history of Lörrach and its surroundings . Peter Krauseneck, Rheinfelden 1948.

- Gerhard Moehring : A short history of the city of Loerrach . Braun, Karlsruhe 2007, ISBN 978-3-7650-8347-1 .

Baden Revolution in Loerrach

- Jan Merk: «Lörrach 1848/49», essays, biographies, documents, projects, city of Lörrach . In: Lörracher Hefte . tape 3 . Lutz, Lörrach 1998, ISBN 3-922107-45-1 (accompanying publication to the exhibition "Nationality separates, freedom connects" of the House of History Baden-Württemberg and the Three- Country Museum in Lörrach, April 19, 1998 to January 10, 1999).

- Hans R. Schneider, Benoit Brunant, Markus Moehring, Albrecht Krause (Editor): Nationality separates, freedom connects / Séparés par la nationalité, unis par la Liberté . Catalog for the exhibitions in Liestal (Switzerland), Lörrach (Germany), Mulhouse (France). A trinational exhibition project. House of History Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-933726-10-7 .

Second World War and Nazi era

- Markus Moehring: A Path to World War II, Lörrach 1933–1939 . Accompanying document to the exhibition in the Museum am Burghof, September 1, 1989 to July 1990. Museum am Burghof, Lörrach 1989, DNB 901044830 .

- Wolfgang Göckel: Loerrach in the Third Reich . Self-published, Schopfheim 1990.

- Bernd Serger, Karin A. Böttcher, Gerd R. Ueberschär (eds.): South Baden under swastika and tricolor . Contemporary witnesses report on the end of the war and the French occupation in 1945. Rombach, Freiburg in Breisgau, Berlin, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-7930-5013-0 .

- Robert Neissen: Lörrach and National Socialism - Between Fanaticism and Distance . Ed. City of Lörrach, City Archives, doRi Verlag, Bötzingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-9814362-1-1 . (Scientific companion volume for the exhibition of the same name)

Others

- Heinz Heimgartner: Rötteln castle ruins . A castle guide through the history of Rötteln Castle with a map of the castle complex. Röttelnbund, Haagen (Lörrach) 1964.

- Susanne Asche, Ernst Otto Bräunche, Kathryn Babeck: Street of Democracy - Revolution, Constitution and Law . A route companion on the trail of freedom to Bruchsal, Frankfurt, Freiburg, Heidelberg, Karlsruhe, Landau, Lörrach, Mainz, Mannheim, Neustadt, Offenburg and Rastatt. Ed .: Working group Street of Democracy. Info Verlag, Karlsruhe 2007, ISBN 978-3-88190-483-4 , p. 150-175 .

Web links

- Tabular listing of the historical data of Lörrach

- Notification of the city of Lörrach regarding June 3, 1756 on the homepage of the Badische Landesbibliothek

References and comments

- ^ Gerhard Moehring: Brief history of the city of Loerrach. P. 16.

- ↑ Small Chronicle of Adelhausen ( Memento from October 6, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 63 ff.

- ↑ Country churches and country clergy in the Diocese of Constance during the early and high Middle Ages, p. 150.

- ^ Church history of the parish Rötteln

- ↑ on the various names that can be found in later documents for Lörrach see Albert Krieger : Topographic Dictionary of the Grand Duchy of Baden. Volume 2, Column 106-108, ( digitized version )

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 116 ff.

- ^ Heinz Heimgartner: Rötteln castle ruins. Verlag Röttelnbund eV 1964, p. 5.

- ↑ Lüthold I. von Rötteln was referred to as Basel Bishop Lüthold II, alternative spelling to Lüthold also Liuthold and Leuthold.

- ↑ A. Baumhauer: Origin and meaning of the Loerrach "Ufhabi". In: Badische Heimat. 35, 1955, p. 275.

- ^ Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar took the castle Rötteln by storm after his victory in the battle of Rheinfelden; see also: Battle of Rheinfelden # Further development

- ↑ The certificate is now in the General State Archives in Karlsruhe (GLA D 477)

- ↑ 600 years of market law in Lörrach ( Memento from December 22, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Further information on the Armagnaks

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 216.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 273.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 224.

- ↑ The file is now in the Lörrach city archive.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 275.

- ↑ From a facsimile of Herbst's personal diary, privately owned.

- ↑ StA Lörrach IX / 1.

- ^ Bernhard Erdmannsdörffer , Karl Obser : Politische Correspondenz Karl Friedrichs von Baden , Heidelberg 1892 ff.

- ^ Gerhard Moehring: Brief history of the city of Loerrach. P. 67.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 282.

- ^ Gerhard Moehring: Brief history of the city of Loerrach. P. 63.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 291 f.

- ^ Gustav Struve: History of the three popular surveys in Baden 1848/1849 ; Freiburg, 1980, p. 67 f., Quote: “ In order to establish contact with the Hecker band as quickly as possible, the Weisshaar-Struve Colonne, about 700 strong, moved the following morning, Maundy Thursday, April 20 , to Loerrach. There should be rest. "

- ↑ Willy Real: The Revolution in Baden 1848/49 (Stuttgart, 1983), Fig. 3 (between pp. 64 and 65)

- ^ Constitutional text of the Baden Constitution ( Memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ StA Lörrach IV 2/1.

- ^ Gerhard Moehring: Brief history of the city of Loerrach. P. 76 ff.

- ↑ Eduard Kaiser : From the old days - memoirs of a Markgräfler 1815-1875. P. 268.

- ↑ Hubert Bernnat: 125 years labor movement in the border region. Loerrach 1993, p. 6.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 300.

- ↑ Lörrach town halls ( Memento from November 16, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Gerhard Moehring: Brief history of the city of Loerrach. P. 88.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 312.

- ↑ Regional history working group: On the history of the workers' movement on the Upper Rhine 1850–1933. P. 106 f.

- ↑ Oberbadisches Volksblatt, October 31, 1923.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 327.

- ↑ Hubert Bernnat: 125 years labor movement in the border region. Loerrach 1993, p. 140.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 332.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 333.

- ↑ State elections in 1929 in the Free State of Baden

- ↑ StA Lörrach District Office VI 2/11.

- ↑ Hubert Bernnat: 125 years labor movement in the border region. Loerrach 1993, p. 157.

- ↑ Oberbadisches Volksblatt, June 5, 1931.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 346.

- ↑ StA Loerrach, stand. Main office 1400/9.

- ^ Gerhard Moehring: Brief history of the city of Loerrach. P. 111.

- ↑ Lörrach: A stele against oblivion. In: Badische Zeitung . September 29, 2010, accessed March 30, 2016 .

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 345.

- ^ History of the Jews in Loerrach

- ↑ StA Lörrach VI 1/22.

- ^ Gerhard Moehring: Brief history of the city of Loerrach. P. 106.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 366.

- ↑ Baden municipal ordinance of September 23, 1948 ( Memento of September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ H. Heim: Change in the cultural landscape in the southern Markgräflerland. Basel Contributions to Geography, Issue 10, Basel 1977.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 477 f.

- ↑ Hubert Bernnat: 125 years labor movement in the border region. Loerrach 1993, p. 1.

- ↑ With a turnout of 70.53% of a total of 13,529 votes cast, source: Lörrach: Landschaft - Geschichte - Kultur. P. 488.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 42.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. Pp. 493, 509 f.

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 512.

- ^ Federal Statistical Office (ed.): Historical municipality directory for the Federal Republic of Germany. Name, border and key number changes in municipalities, counties and administrative districts from May 27, 1970 to December 31, 1982 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Mainz 1983, ISBN 3-17-003263-1 , p. 521 .

- ^ State garden shows in Baden-Württemberg , information on LGS Lörrach 1983, p. 9. ( Memento from July 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 3.4 MB).

- ^ Lörrach: Landscape - History - Culture. P. 551 f.

- ↑ Information on the Lörrach Sculpture Trail , accessed on November 13, 2019

- ↑ loerrach.de: Energiestadt Lörrach , last accessed on April 18, 2019

- ↑ swr.de: New synagogue opened in Lörrach

- ↑ badische-zeitung.de: The profound effect of geometry , November 8, 2008 , last accessed on June 30, 2009.

- ↑ District council decision on the Central Clinic, October 19, 2016 , last accessed on July 20, 2018

- ↑ Lörrach City Administration: Information on the Central Hospital Lörrach , accessed on November 13, 2019

- ↑ Blauraum Architekten : Project description for the Lö residential and commercial building , accessed on February 24, 2020