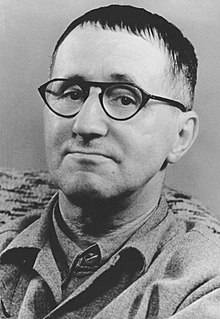

Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht (also Bert Brecht ; * February 10, 1898 as Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht in Augsburg , † August 14, 1956 in East Berlin ) was an influential German playwright , librettist and poet of the 20th century. His works are performed worldwide. Brecht founded and implemented epic theater or “dialectical theater”. His best-known pieces include The Threepenny Opera , Mother Courage and Her Children, as well as the work critical of capitalism The Saint Joan of the slaughterhouses .

Life

Childhood and youth: Augsburg 1898 to 1917

Parents and social environment

Eugen Brecht, as the young Bertolt Brecht was called, grew up in secure economic and social circumstances. His father Berthold Friedrich Brecht, son of a lithographer in Achern , Baden , had no higher education: he attended elementary school and then completed a commercial apprenticeship. In 1893 he started as a clerk at Haindl'schen Papierfabrik in Augsburg , a prosperous company that at that time had around 300 employees in Augsburg alone. There Berthold Friedrich Brecht rose quickly, in 1901 as authorized signatory and in 1917 as director of the commercial department. Brecht's mother Wilhelmine Friederike Sophie, née Brezing (1871–1920), came from the Upper Swabian town of Roßberg near Wolfegg and came from a small civil servant household (her father was the station director at the Roßberg railway junction ).

From September 1900 the family, Berthold Friedrich and Sophie Brecht as well as Eugen and the younger brother Walter , lived in two apartments with a total of six rooms in the Augsburg Klaucke-Vorstadt, also known as the " Bleich " district. The apartment belonged to a four-house Haindl foundation , mainly for deserving workers and employees of the paper mill; Berthold Friedrich Brecht's tasks included the administration of this foundation. The Brechts employed a maid . Sophie Brecht suffered from depression and breast cancer for years and died of a recurrence of her cancer in 1920 . In my mother's song , Brecht writes: "I don't remember her face as it was when she wasn't in pain." Since 1910, the Brechts therefore had an additional housekeeper . Eugen had to vacate his room for this, but was given an attic apartment with its own entrance.

The father was Catholic , the mother Protestant . They had agreed that the children would be brought up in the Protestant faith, so that the young Eugen Brecht belonged to a minority in the predominantly Catholic Augsburg. From 1904 he attended elementary school in Augsburg, from 1908 the Augsburg Realgymnasium (today Peutinger-Gymnasium ) and regularly brought home good, if not very good, certificates. He received piano, violin and guitar lessons, but only the latter struck. At an early age he suffered from heart problems, which resulted in a number of spa stays; It is unclear whether the complaints were organic or neurotic .

First publications

At the age of fifteen, Brecht and his friend Fritz Gehweyer published a school newspaper, The Harvest , in which he wrote the majority of the articles himself, some under foreign names, and also copied. He wrote poems, prose texts and even a one-act drama, The Bible . In the years that followed, Brecht continued to produce poems and drafts for dramas. After the beginning of the First World War in 1914, he managed to accommodate a series of (mostly patriotic) reports from the home front, poems, prose texts and reviews in local and regional media: the so-called "Augsburger Kriegsbriefe" (Augsburg War Letters) in the Munich-Augsburger Abendzeitung , other texts in the Augsburger Neuesten Nachrichten and in particular its literary supplement, Der Narrator . They were mostly drawn with Berthold Eugen, a combination of his first names.

In his texts, Brecht soon abandoned the patriotic glorification of the war, and production for the local newspapers declined. Because of an essay on the Horace verse Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori ("It is sweet and honorable to die for the fatherland") that Brecht wrote in 1915 and did not correspond to the expected pathos of death , he is said to have almost been expelled from high school. From 1916 onwards, he wrote poems that were added to the Bertolt Brecht's house postil in 1927 , which Brecht was also later to support. The first of them was the song of the Fort Donald railway troop , first published in July 1916 in the narrator and drawn "Bert Brecht". It was here that Brecht used the form of name under which he became known for the first time.

Friendships and love affairs

During the war years he gathered a circle of friends who wrote and sang songs with him and worked on publications. Caspar Neher ( Cas ), whom Brecht knew from school, remained a close associate as a graphic designer and, above all, a stage designer until Brecht's death; The friendships with Georg Pfanzelt (whom Brecht immortalized as Orge in the house postil) and Hanns Otto Münsterer also proved to be lasting (with interruptions). Together with his friends (especially Ludwig Prestel and Lud ), Brecht not only drafted the lyrics, but also the melodies for songs and poems and then played them on the guitar. In this phase, two characteristics of Brecht's way of working became apparent: the collective work in a team, which, however, is clearly geared towards the central figure Brecht, and the very close connection with other arts with a view to the realization, especially graphics / set design and music .

It was during this time that the young Brecht had his first love affairs. He courted the student Rosa Maria Amann, whose name later went into the title of one of his most famous poems ( Memory of Marie A. ). Soon, however, the love for Paula Banholzer came to the fore, which he called "Bi" (for bittersweet or "bittersweet", based on the model of the drama The Exchange by Paul Claudel , which is accused of exchanging partners). Even so, he continued to seek Amann and other young women whom he had eyeed - a trait that continued throughout his life.

In March 1917, Brecht announced for auxiliary military service and obtained the approval of a simplified Notabitur , which he successfully completed a 18-year-old high school. He did his job with paperwork and in a gardening shop. He was postponed from military service. In the summer he worked at Tegernsee as a private tutor for a classmate from a wealthy family; then he began studying medicine in Munich.

On the way to becoming a professional writer and theater practitioner

Studies and military service

Formally, Brecht studied medicine and philosophy. However, he rarely attended medical lectures, but concentrated on a seminar by Artur Kutscher on contemporary literature. There he met the poet and dramatist Frank Wedekind, whom he admired, as well as Otto Zarek and Hanns Johst , and established a casual relationship with the medical student Hedda Kuhn, who appears in his psalms as "He". Among other things, the current novel Ambros Maria Baal by the expressionist Andreas Thom was discussed in the seminar . This novel and Johst's Grabbe drama Der Einsame , which he saw in March 1918, inspired Brecht to draft his own drama under the title Baal , the first version of which was ready in June. Brecht's father had the company secretaries type a fair copy, which Brecht initially unsuccessfully sent to Kutscher, Lion Feuchtwanger , Jacob Geis and Alfred Kerr . It was during this time that some of Brecht's most famous poems were written, especially the legend of the dead soldier and Lucifer's evening song , later renamed Gegen Verführung .

In the first two semesters, with the support of his father, Brecht managed to get a postponement from military service; in October 1918, however, he was called up as a military nurse in an Augsburg reserve hospital. At that time he wrote his song to the cavaliers of station D - the letter stands for dermatology , it was a station for venereal diseases - and with his circle of friends produced a book of songs on the guitar of Bert Brecht and his friends . After the November Revolution , Brecht was a member of the military council and thus of the Augsburg workers 'and soldiers' council , but did not excel in any way. On January 9, 1919, he was able to finish his service again.

Determined networking

Brecht had maintained his love affair with Paula Banholzer during this time, and in January 1919 it turned out that the 17-year-old was pregnant by him. Banholzer's father did not believe in a marriage with the hitherto unsuccessful poet and sent her to the Allgäu village of Kimratshofen , where she gave birth to her son Frank on July 30, 1919. Brecht had been writing a new drama since January, Spartakus (later renamed Drums in the Night ). In February he went to see Lion Feuchtwanger to show him a first version of the play. The influential Feuchtwanger expressed himself very positively and became one of the most important and long-term supporters of the young Brecht.

Although Brecht had Feuchtwanger's support, there was initially neither a print nor a performance of one of his pieces, which he constantly reworked. In 1919 he also wrote a series of one-act plays, including Die Hochzeit (later titled: Die Kleinbürgerhochzeit ), which also remained unperformed. Since October 13, 1919, he has at least written the theater reviews for the USPD newspaper Der Volkswille in Augsburg, although the Augsburg theater faced a number of problems due to his polemics that resulted in an insulting process . During his first trip to Berlin in February 1920, Brecht used his Munich acquaintances with Hedda Kuhn and the writer and journalist Frank Warschauer (in whose apartment on Eislebener Strasse he stayed both now and during his second stay in 1921/1922) to make new contacts tie. The recommendation to Hermann Kasack , at that time a lecturer at Kiepenheuer , with whom he negotiated about the Baal without any results , was particularly valuable .

After the Kapp Putsch , Brecht returned to Munich. Around December he met the singer Marianne Zoff as Augsburg's Volkswille theater critic and began an intense love affair with her without ending the relationship with Paula Banholzer. He got involved in violent arguments with Zoff's other lover Oscar Recht. Both Zoff and Banholzer became pregnant again by Brecht in 1921, but Zoff had a miscarriage, Banholzer possibly an abortion . In the meantime, Brecht was working on another piece, later entitled In the Thicket of Cities, and also on a number of film projects, all of which, however, could not be sold. At least he managed to get the pirate story Bargan lets it be in the nationally known magazine Der Neue Merkur in September 1921 .

Especially on a second trip to Berlin between November 1921 and April 1922, Brecht made determined acquaintances with influential people in Berlin's cultural life. He conducted parallel negotiations with Kiepenheuer-Verlag (via Hermann Kasack, with the result of a general contract and a provisional monthly pension), Verlag Erich Reiss (mediated by Klabund ) and Verlag Paul Cassirer , learned actors such as Alexander Granach , Heinrich George , Eugen Klöpfer and Werner Krauss know and bonded with the aspiring playwright Arnolt Bronnen in joint ventures on the cultural market. During this time he also changed the spelling of his first name to Bertolt in order to create a distinguishing mark for the 'company' Arnolt Bronnen / Bertolt Brecht. A particularly important contact was to be the theater critic of the Berliner Börsen-Courier , Herbert Ihering , who entered since repeatedly publicly for Brecht. A first attempt at directing Bronnen's play Patermord had to be broken off due to violent arguments between Brecht and the actors. On Trude Hesterberg's Wilder stage he appeared as a singer to the guitar with his legend of the dead soldier , causing a scandal; He made similar appearances as a 'songwriter', especially at semi-public meetings of the cultural scene. At the end of 1922, Brecht, who had overwhelmed himself, had to go to the Charité for three weeks with a kidney infection .

First successes

In the meantime it had actually succeeded in arranging the first premiere of a Brecht piece in Munich : Drumming in the Night with Otto Falckenberg at the Munich Kammerspiele. Brecht revised the text again in the summer, rehearsals began on August 29, 1922, the premiere took place on September 29, 1922 and was enthusiastically reviewed by Ihering. The following day, the Kammerspiele showed the revue Die Rote Zibebe by Brecht and Valentin in their midnight performance , including Brecht himself as "Klampfenbenke", Klabund, Joachim Ringelnatz (with Kuttel Daddeldu ), Valeska Gert , Karl Valentin and Liesl Karlstadt . Feuchtwanger published an article about Brecht in Das Tage-Buch , Baal was published by Kiepenheuer, the German Theater in Berlin arranged the performance of all Brecht dramas, and Ihering awarded him the Kleist Prize, endowed with 10,000 Reichsmarks . A real “breakout house” had broken out.

During the rehearsals of the drums it had already been found that Marianne Zoff was pregnant again. Brecht, who held a position as a dramaturge and director at the Münchner Kammerspiele from mid-October 1922 , and Marianne Zoff married on November 3, 1922 in Munich. In mid-November, however, he traveled back to Berlin to take part in the rehearsals for the Berlin premiere of drums that night , which took place on December 20th. Before the turn of the year, the first print of the piece was published by Drei Masken Verlag , with the legend of the dead soldier in the appendix. In addition, in March 1923, Brecht completed the grotesque film Mysteries of a Hairdressing Salon together with Erich Engel and Karl Valentin . On March 12, 1923, their daughter Hanne was born in Munich .

In the Thicket of Cities , a version revised at short notice by Brecht, entitled In the Thicket, premiered on May 9, 1923 at the Munich Residenztheater . Caspar Neher was responsible for the set for the first time. While Ihering was again composing hymns of praise, the Nazis were already disturbing the second performance of the piece with stink bombs. The piece was canceled after six performances "because of the opposition in the audience".

Director Brecht

In the following months Brecht made another attempt as a director in Berlin, again together with Bronnen, namely for the bustling theater maker Jo Lherman . He radically shortened the mystery play Pastor Ephraim Magnus by Kleist Prize winner Hans Henny Jahnn from seven to two hours under chaotic circumstances and constant arguments with the actors, but the premiere on August 23, 1923 was not a success, especially since Lherman's checks turned out to be uncovered. During this time, Brecht met the actress Helene Weigel and began a relationship with her.

From the end of 1923, Brecht concentrated on directing the Münchner Kammerspiele. Together with Lion Feuchtwanger as well as Bernhard Reich and Asja Lacis he arranged an Elizabethan piece by Christopher Marlowe , Edward II , under the title Life of Edward II of England . It was the first directorial work that Brecht was able to successfully complete; after John Fuegi, this is where he developed his personal directorial style for the first time, especially since he was able to work with Neher as a set designer. After numerous delays, the edited piece premiered on March 19, 1924; in June the first print of the arrangement with etchings by Neher was published by Kiepenheuer, under Brecht's name, but with the note on page 2: “I wrote this piece with Lion Feuchtwanger.” Baal had already been premiered on December 8, 1923 in Leipzig. Brecht had taken part in the rehearsals and made few friends in the process. The play was immediately canceled at the instigation of the Leipzig city council.

In the spring of 1924 Helene Weigel von Brecht was pregnant. Without telling his wife Marianne anything about it, or at all about this affair, Brecht went on vacation to Capri with Marianne and Hanne in April . He also used the opportunity to meet Neher, Reich and Lacis - and to make a flying visit to Florence , where he met Helene Weigel. In June, Brecht first returned to Berlin to advance his business with the Kiepenheuer Verlag. The collection of poems Hauspostille , which he owed Kiepenheuer for almost two years, he edited together with Hermann Kasack, but afterwards again did not send a finished text, but kept the publisher off. At that time there was still talk of Marianne Brecht moving to Berlin (Kiepenheuer had already started looking for an apartment for her) - but Brecht had already reached an agreement with Helene Weigel that he could take over her attic apartment in Berlin . In September 1924 he finally moved to Berlin.

Creative period before exile

He divorced Marianne three years later and married Helene Weigel on April 10, 1929, who gave birth to their second child, Barbara, on October 28, 1930.

Brecht developed into a staunch communist in the second half of the 1920s and from then on pursued political goals with his works such as the play Mann ist Mann (premiere 1926). But he never joined the KPD . Brecht's reception of Marxism was influenced by both undogmatic and non-party Marxists such as Karl Korsch , Fritz Sternberg and Ernst Bloch, as well as by the official KPD line. From 1926, the formation of his epic theater took place parallel to the development of his political thought. Numerous theater reviews that he wrote in recent years began his criticism of bourgeois German theater and the art of acting. The remarks on the opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny , which Brecht wrote together with Peter Suhrkamp in 1930, are an important theatrical theoretical essay . The collaboration with Kurt Weill in several music-dramatic works was also essential for the development of the epic theater.

Brecht was not only active in the theater, but also in other fields, across all genres and genres. He wrote poems, songs, short stories, novels, short stories and radio plays for the radio. With his works, Brecht wanted to make social structures transparent, especially with regard to their changeability. For him, literary texts had to have a “use value”. He described this in detail in his 1927 Short Report on 400 (Four Hundred) Young Poets .

In collaboration with Kurt Weill, a number of so-called teaching pieces with avant-garde music were created, for example the piece Lindberghflug 1929, the school opera Der Jasager (1930), which he revised after discussions with students from the Karl Marx School (Berlin-Neukölln) and the alternative Der Neinsager added, as well as The measure (also 1930). Bertolt Brecht's collection of poems published in 1927 consisted of texts that were largely written earlier. In 1928 Brecht celebrated one of the greatest theatrical successes of the Weimar Republic with his Threepenny Opera , set to music by Kurt Weill and premiered on August 31. In the same year Brecht met Hanns Eisler , who now became the most important composer of his pieces and songs. A close friendship and one of the most important poet-musician partnerships of the 20th century grew out of this acquaintance.

Life in exile

In 1930 the National Socialists began to vehemently disrupt Brecht's performances. At the beginning of 1933 a performance of The Measure was interrupted by the police. The organizers were charged with high treason. On February 28 - one day after the Reichstag fire - Brecht left Berlin with his family and friends and fled abroad. His first exile stations were in Prague, Vienna, Zurich, in the early summer of 1933 Carona with Kurt Kläber and Lisa Tetzner and Paris. At the invitation of the writer Karin Michaëlis , Helene Weigel traveled with the children to Denmark on the small island of Thurø near Svendborg . In April 1933, Brecht was on the “black list” drawn up by Wolfgang Herrmann ; therefore his books were burned by the National Socialists on May 10, 1933 , and all of his works were banned the next day. Brecht was stripped of his German citizenship in 1935 .

In 1933, Brecht set up the DAD agency, the "German Author Service", in Paris. This was intended to give emigrated writers, in particular his co-author and lover Margarete Steffin , opportunities for publication. Together with Kurt Weill , Brecht developed his first exile piece, the ballet The Seven Deadly Sins , which premiered in July 1933 at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Shortly afterwards, Brecht bought a house in Svendborg (Denmark) and spent the next five years there with his family. In 1938 the life of Galileo originated . In addition to dramas, Brecht also wrote articles for several émigré magazines in Prague, Paris and Amsterdam. In 1939 he left Denmark, lived in a farmhouse in Lidingö near Stockholm for a year and in April 1940 in Helsinki. During the summer stay in Marlebäck in 1940 , where the family had been invited by the Finnish writer Hella Wuolijoki , Brecht wrote the play Mr. Puntila and his servant Matti , based on a text by Wuolijoki , which was only premiered on June 5, 1948 in Zurich. In the summer of 1940 he began working with Wuolijoki on the unfinished piece Die Judith by Shimoda based on a template by Yuzo Yamamoto.

It was not until May 1941 that Brecht received his entry visa to the USA and was able to travel with his family by ship to Santa Monica in California via Moscow and Vladivostok . He lived there for five years, from 1942 to 1947, at 1063 26th Street, just outside Hollywood . He envisioned working as a successful screenwriter in the film business; but this did not happen at first because of his aversion to the USA and its isolation. He had little opportunity for literary or political work and described himself in view of the disinterest of the Americans as a "teacher without students". With Charles Laughton , who later played the lead role in Brecht's only theater work in American exile, he translated his play The Life of Galileo , which premiered in July 1947 at the Coronet Theater in Beverly Hills . The original version was premiered on September 9, 1943 in the Schauspielhaus Zurich .

After the USA entered the war, Brecht had to register as an " enemy alien " in 1942 and was monitored by the FBI. Suspected of being a member of a communist party, he was questioned by the Committee on Un-American Activities on October 30, 1947 . When asked whether he had ever been a member of the Communist Party or was still present, Brecht answered “no” and added that he was also not a member of a Communist Party in Germany. A day later he traveled to Paris and shortly afterwards on November 5th to Zurich. He stayed there for a year, since Switzerland was the only country for which he was granted a residence permit; He was forbidden from entering West Germany - the American zone of occupation. In February 1948, Brecht's version of Antigone des Sophocles was premiered in the Chur City Theater.

Return to Berlin

Sounding out the situation

Shortly after the war, Brecht was urged by friends to come back to Germany and stage his plays himself. However, he waited in Zurich and sounded out the situation. When several theaters were reopened in the Soviet occupation zone in 1948 and the "German Theater" and the Volksbühne resumed work in Berlin , he traveled from Zurich via Prague to Berlin in October 1948 at the invitation of the Kulturbund for the democratic renewal of Germany . Entry into the western occupied areas of Germany was still forbidden to him. When he arrived in East Berlin, he quickly made contact with important artists and functionaries. The fact that Alexander Dymschitz, an admirer of Brecht's works, sat in the Soviet military administration should also prove to be beneficial for him. The reunion with Jacob Walcher , whose political judgment Brecht always trusted to a particular degree, was a great pleasure for Brecht, as he had now found the expert with whom he could discuss the political constellations. Brecht initially abstained from making political statements in public. As early as January, Brecht in Switzerland expressed his skepticism about developments in Germany.

“It is clear from everything that Germany has not yet grasped its crisis. The daily grief, the lack of everything, the circular movement of all processes, keep the criticism in the symptomatic. Carry on is the watchword. It is postponed and it is suppressed. Everything fears tearing, without which building is impossible. "

Although Brecht was not granted any far-reaching privileges during his stay in Berlin, negotiations with publishers did take place. After some hesitation, he arranged his publishing affairs: The experiments and the collected works were to be published by Peter Suhrkamp , the GDR-Aufbau Verlag was also to receive a license for them, and the rights for the stage works remained with Reiss-Verlag in Basel. The Aufbau-Verlag became interested in Brecht's poetry at an early stage.

Brecht found it important to regain a foothold in the theater business. He immediately accepted an offer by Wolfgang Langhoff to stage his own plays at the Deutsches Theater. This also achieved an important goal of his Berlin friends, to tie the artist to a Berlin theater. Together with Erich Engel , Brecht staged the play Mother Courage and Her Children . The premiere on January 11, 1949 was an extraordinary success for Brecht, Engel and the leading actress Weigel, especially because of Brecht's theory of epic theater. On the one hand, the production was praised in the press, on the other hand, later conflicts with the cultural officials became apparent. Terms such as “decadence alien to the people”, still tagged with question marks, appeared in public, apparently in the expectation that the formalism debate of Zhdanov in the USSR in 1948 would inevitably reach the arts and culture of the GDR .

In February 1949, Brecht returned briefly to Zurich to apply for a permanent residence permit, as Berlin was not immediately his first choice. However, the approval was denied. Brecht also tried to win actors and directors for his upcoming work in Berlin. At the same time he conducted extensive studies on the history of the Paris Commune . The text of the play Die Tage der Commune (a revision of Nordahl Grieg's Die Deflage ) was ready in April 1949, but Brecht was dissatisfied with what had been achieved and initially postponed the production. When he finally left Zurich on May 4, 1949, he had signed contracts with Therese Giehse , Benno Besson and Teo Otto , among others . Previously, Brecht, who had become a stateless person through expatriation in 1935 , with the intention of creating a version of Jedermann , had approached the director of the Salzburg Festival Gottfried von Eine in April 1949 and at the same time pointed out the original nationality of his wife Helene Weigel the Austrian citizenship requests. In August 1949 he moved to one in Salzburg and began working on Jedermann. On April 12, 1950 , the Salzburg state government granted Brecht and Weigel the desired citizenship at the intercession of one and numerous Austrian cultural workers who expected the local cultural life to be enriched . In the GDR, the authorities from then on listed Brecht and Weigel as German and Austrian citizens. In Austria, Brecht met with criticism the following year. He left the country in 1950 without ending Jedermann . As the author of naturalization, one lost his post at the Salzburg Festival.

An own ensemble

While Brecht was in Switzerland, Helene Weigel had arranged everything necessary to be able to found Brecht's own ensemble. Wilhelm Pieck , Otto Grotewohl and on the part of SMAD Alexander Dymschitz had supported the project to the best of their ability. On April 29, 1949, the responsible state agency was informed of the decision by the SED Politburo to found a "Helene Weigel Ensemble" with the stipulation that the game should start operating on September 1, 1949. The appointment of Helene Weigel as ensemble leader only had advantages for Brecht. On the one hand, he did not have to deal with the bureaucracy of the theater business, but on the other hand he could also be sure that Weigel would not force him to compromise through his own ambition. In the first few years, the concept of working together between talented actors and directors from the exile scene and young talents from Germany seemed to work, but the Cold War and the debate about Brecht's epic theater soon had an impact in this area too. Agreements could not be kept, artists such as Peter Lorre expected by Brecht did not come to Berlin. Other artists, such as Teo Otto, who were confronted with allegations of formalism, ended the collaboration.

Theater work in the GDR

When a new Academy of the Arts was to be brought into being with the founding of the GDR in 1949 , Brecht tried to bring his ideas into play: "In any case, our academy should be productive and not just representative." " into the conversation. In the now renamed Berliner Ensemble , Brecht often and happily surrounded himself with students such as Benno Besson , Peter Palitzsch , Carl Weber and Egon Monk . At the beginning of 1950 Brecht turned to the play Der Hofmeister by the “Sturm und Drang” poet Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz , for which he felt great sympathy throughout his life. The premiere of his adaptation took place on April 15, 1950; it was the ensemble's greatest success during Brecht's lifetime, and it was here that the public saw him for the first time as a director.

In the early 1950s have been taken by the SED important policy decisions, as was the construction of socialism as the fundamental duty [...] become . At the same time, the debate about formalism in art became more acute. Brecht acted cautiously here and did not get involved in a theoretical discussion. He rather took the path of small steps and prepared his audience for the “didactic theater” he wanted with the new production of Die Mutter in 1950/1951. In the rather admonishing and benevolent criticism that began with this production, the special role of Brecht, which he enjoyed in the GDR art scene, became clear once again. Other artists like Paul Dessau felt the formalism allegations of the functionaries much more clearly. However, Brecht's libretto for the opera The Condemnation of Lucullus , the “trial performance” of which took place on March 17, 1951 under the title The Interrogation of Lucullus , also got into the dispute. A failure should apparently be organized through the targeted allocation of cards by the Ministry of National Education. The plan failed completely. In the following discussions about the play, in which the highest state officials took part, Brecht acted skillfully, always looking for a compromise. On October 7, 1951, Brecht received the national prize of the GDR first class. With his works, Brecht had helped "to lead the struggle for peace and progress and for a happy future for mankind". In 1952 he had a production of Urfaust with young actors in Potsdam - outside of Berlin - a practice that he practiced even more often. On July 2, 1952, Brecht and Helene Weigel moved into a house in Buckow . Not without pride he declared: "I now belong to a new class - the tenants." ()

Brecht's reactions to June 17, 1953

When there were mass protests by GDR workers in Berlin on June 17, 1953 , on the same day Brecht expressed his “solidarity with the Socialist Unity Party of Germany” in a concise letter to Walter Ulbricht , but at the same time formulated the expectation of a “debate with the masses on the pace of socialist construction ”. On the same day, Brecht sent further short addresses of solidarity to Vladimir Semjonow (“unbreakable friendship with the Soviet Union”) and to Otto Grotewohl and Gustav Just with the offer of contributing to the current radio program.

Brecht analyzed the situation at the same time in an unpublished typescript as follows: “The demonstrations of June 17th showed the dissatisfaction of a considerable part of the Berlin working class with a number of unsuccessful economic measures. Organized fascist elements tried to abuse this discontent for their bloody ends. For several hours Berlin was on the brink of a Third World War . It is only thanks to the rapid and safe intervention of Soviet troops that these attempts were foiled. It was evident that the intervention of the Soviet troops was by no means directed against the workers' demonstrations. It was apparently directed exclusively against attempts to ignite a new world fire. It is now up to each individual to help the government eradicate the mistakes that have created discontent and threaten our undoubtedly great social achievements. "

Brecht saw the cause of the strikes in the government's attempt to “increase production” by raising labor standards without adequate consideration. The artists were functionalized as propagandists for this project: “The artists were given a high standard of living and the workers were promised it.” Brecht saw a real change in the sphere of production as an alternative.

Brecht had closed his letter to Ulbricht with an address of solidarity for the party, which for some biographers was a mere polite phrase. The government published in Neues Deutschland on June 21, 1953, however, only its affiliation with the party, which permanently discredited Brecht. Brecht tried to correct the impression made by the published part of the letter. Under the heading For Fascists There Can Be No Mercy , Brecht, along with other authors, took a position in the New Germany of June 23, 1953. In addition to a legitimizing introduction, which cited the abuse of the demonstrations "for warlike purposes", he again called for a "big debate" with the workers "who demonstrated with justified dissatisfaction". In October 1953, Brecht tried to distribute the complete letter to Ulbricht through journalists.

“At that time a world collapsed for Brecht. He was shocked and horrified. Eyewitnesses report that they saw him downright helpless at the time; For a long time he carried a copy of the fateful letter with him and showed it to friends and acquaintances to justify himself. But it was too late. Suddenly the West German theaters, the most loyal ones he had next to his own, removed his plays from the repertoire, and it took a long time for this boycott to loosen up again. "

Ronald Gray found in Brecht's behavior the figure of Galileo Galilei , whom Brecht himself had created literarily: The chameleon-like verbal adaptation to the regime enabled him to pursue his real interests. Walter Muschg reflected on Brecht's unclear behavior with reference to the double life of the Brecht character Shen-Te from The Good Man of Sezuan :

“He who remained free from the cowardice and stupidity of the time led the double life represented by 'The Good Man of Sezuan' and tainted himself with concessions in order to be able to keep himself up. It did not help him that the verses he provided for official occasions, intentionally or not, were astonishingly bad; Schweyk's cunning in dealing with the dictatorship could not calm him down. He had to feel like a ghost of himself because, too proud to flee, he persevered under the flag that had long since become questionable to him. Only a better end to the war could have saved him from this predicament. He wasn't a traitor, but a prisoner. He became an outsider again, his face took on a corpse-like appearance. The worst abuse of his person was the embezzlement of his critical position on the suppression of the Berlin June uprising of 1953, of which the public only got to see the binding final formula. After his early death, which is probably related to the grief over it, poems came to light that show what he suffered. "

In his Brecht biography Brecht & Co. , John Fuegi analyzes Brecht's reactions differently . Brecht himself was under pressure during this time and fought to take over the theater on Schiffbauerdamm . His reference to CIA provocateurs shows his fundamental misinterpretation of the situation. "The GDR government had lost contact with the workers, and that also applied to Brecht." In addition to the letter cited above, Brecht had also sent further solidarity addresses to Vladimir Semjonow and Otto Grotewohl. Brecht also did not react to protests by a worker in the Berliner Ensemble against the low wages of around 350 marks net, although he had received a salary of 3000 marks at the theater alone.

In the poetic reflection of the events in July / August 1953, Brecht took a clearly distant attitude towards the GDR government, which he articulated in the Buckower Elegies in the poem The Solution, among other things .

After the June 17th uprising

Left the secretary of the Writers' Union

Hand out leaflets in Stalinallee

On which it was read that the people

I forfeited the government's trust

And only by doing double the work

Could recapture. If it were there

Not easier, the government

Dissolved the people and

Chose another?

The kind of discussion Brecht had wished for did not take place; he withdrew from the fruitless debates that followed. From July to September 1953, Brecht worked mainly in Buckow on the poems of the Buckower Elegies and on the play Turandot or the Congress of the White Washer . During this time, Brecht also experienced several personal crises in connection with his constantly changing love affairs. Helene Weigel temporarily moved alone to Reinhardstrasse 1, Brecht in a backyard building at Chausseestrasse 125. His long-time loyal companion Ruth Berlau was now increasingly a burden for Brecht, especially since she only carried out her work in the ensemble sporadically.

The last few years

In January 1954 the Ministry of Culture of the GDR was founded, Johannes R. Becher was appointed minister and Brecht was appointed to the artistic advisory board. The old administrative structures were dissolved. This was supposed to finally eliminate the ubiquitous tension between the artists and the state officials. The concept of formalism disappeared from the debates. Brecht welcomed the changes and called on his fellow artists to take advantage of the new opportunities. On March 19, 1954, Brecht and his staff opened the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm with an adaptation of Molière's Don Juan . Against the background of the ever worsening East-West confrontation, Brecht took part in discussion evenings in West Berlin in 1955 and worked to publish his war primer . On December 21, 1954, Brecht was awarded the International Stalin Peace Prize, which was presented to him on May 25, 1955 in the Moscow Kremlin. Brecht continued to have ideas and plans for new pieces, which he increasingly delegated to his staff. In June 1954, Brecht was appointed Vice President of the German Academy of the Arts. Brecht also did an enormous amount of work in the last years of his life: two productions per year as a director, participation in almost all productions by other directors of the Berliner Ensemble as well as all kinds of literary work. With two guest performances, in 1954 with Mother Courage and in 1955 with The Caucasian Chalk Circle in Paris , Brecht's ensemble has now made its international breakthrough. The triumphant success signaled to every theater official: Brecht can be staged without taking a risk.

death

On May 15, 1955, Brecht wrote his will and wrote a letter to Rudolf Engel , an employee of the Akademie der Künste, pleading with him: “In the event of my death, I do not want to be laid out or publicly displayed anywhere. No one should speak at the grave. I would like to be buried in the cemetery next to the house I live in on Chausseestrasse. ”A year later, Brecht was admitted to the Charité hospital in Berlin with flu . To relax, he spent the summer in the country house on Buckower Schermützelsee in Märkische Schweiz. But even the country air could not cure his heart problems, which he had had since childhood.

Brecht died on August 14, 1956 at 11:30 p.m. in Berlin's Chausseestrasse 125, today's Brecht House . It was long believed that he suffered a heart attack on August 12, 1956 . However, in his childhood Brecht had suffered from rheumatic fever - a disease that was still little understood at the time. This attacked his heart, which led to chronic heart problems. The rheumatic fever was associated with minor chorea , and urological problems also occurred . Brecht had organic complaints throughout his life that ultimately led to heart failure .

On August 17, 1956, Brecht was buried with great public participation and in the presence of numerous representatives from politics and culture. At the funeral, as he had wished, there was no speech. He is buried with his wife Helene Weigel, who died in 1971, in the Dorotheenstädtischer Friedhof in Berlin. The grave of honor is located in the CAM department.

His wish for the design of his gravestone with the inscription proposed by him

I don't need a tombstone, though

If you need one for me

I wish it was written on it:

He made suggestions. we

Have you accepted.

Such an inscription would be

We are all honored.

was not complied with. Instead, only his name was affixed to the rather simple stone.

Brecht in portraits and sculptures

- Fritz Heinsheimer : Bert Brecht (1926) in the Brechthaus Museum in Augsburg

- Rudolf Schlichter : Bertolt Brecht (around 1926) in the Lenbachhaus in Munich.

- Paul Hamann : Bertolt Brecht (1930). Head. Hamburger Kunsthalle .

- Fritz Cremer : Portrait of Bertolt Brecht (1956/57) National Gallery Berlin ; State Art Collections Dresden; Rostock art gallery

- Gustav Seitz : Portrait of Bertolt Brecht (1959)

- Gustav Seitz : Statuette Bertolt Brecht I (1957/58)

- Waldemar Grzimek : Portrait Study Bertolt Brecht (1958)

- Fritz Cremer : Monument to Bertolt Brecht (1986–1988 / 89) on Bertolt-Brecht-Platz in Berlin

- Bust of the Hall of Fame in Munich unveiled on April 22, 2009

Epic theater

Brecht wanted an analytical theater that encourages the viewer to reflect and question at a distance rather than empathize. For this purpose, he deliberately "alienated" and disillusioned the game in order to make it recognizable as a drama in relation to real life (Brecht called this the " alienation effect "). Actors should analyze and synthesize, that is, approach a role from the outside, and then consciously act as the character would have done. This new conception of the theater, originally "epic theater", he later called "dialectical theater", since a contradiction between entertainment and learning is supposed to arise that wants to destroy the illusion of "being emotionally drawn into" the audience. Brecht took the view of the dialectic of people as the product of relationships and believed in their ability to change them: "I wanted to apply the sentence to theater that it is not just a matter of interpreting the world, but of changing it." With this he refers to the central conclusion of the Marxian theses about Feuerbach .

The epic theater of Brecht is contrary both to the teaching of Stanislavski and that of the method acting (methodical acting) by Lee Strasberg demanded aspired to the highest possible realism and the actor to put themselves in the role. However, the most important elements of the epic theater were already developed in Brecht's work before his encounter with Marxism.

The term misuk coined by Brecht represents an attempt to transfer these ideas to the field of music.

The work

Pieces

Brecht mostly formed his pieces in direct interaction with the performances. So, at least in the time before his exile, the print versions often followed the productions. Experiences made here could be incorporated there. Between 1918 and 1933, Brecht experimented intensively with the various artistic possibilities offered by the theater stage. That changed after Brecht had to leave Germany. With a few exceptions, he was now only able to produce "on stockpile". In this so-called “second period”, Brecht's style, his epic theater, was shaped . Modifications to the pieces were the order of the day. Changing political circumstances, reflected by the author, flowed into the pieces. The American version of the life of Galileo may serve as an example here , in which both the language and stage skills of the main actor Charles Laughton were found , as well as Brecht's shock at the American atomic bombs in World War II , which led to a shift in the focus of the statement to the question of personal responsibility of the scientist before society. When Brecht returned to Europe after the war, direct theater work - including the adaptation of plays by other authors - was the focus of his work.

Brecht wrote 48 dramas and around 50 dramatic fragments, seven of which are considered playable. Apart from smaller works, Baal Brecht's first piece was followed in 1919 by a drama that was clearly more socially critical with Drums in the Night . His greatest success, the Threepenny Opera , fell in 1928; it would not have been possible without Kurt Weill's music. In 1930 the play Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny caused one of the biggest German theater scandals when tumultuous scenes occurred in Leipzig that were probably provoked by political opponents among the audience. Brecht's operas and his didactic pieces are considered avant-garde , while his exile dramas do not leave the classical framework of “theater as an institution”.

According to Elisabeth Hauptmann, Brecht needed a “lively counterpart, an intellectual player” to write the play. Brecht's student Manfred Wekwerth also knew that the poet was particularly productive where he already found something that he could change, correct, redesign. It was not just about doing, but about doing differently . Cooperative working methods and close collaboration with students were common at Brecht, with Brecht being the dominant person. Several legends grew up around Brecht's working style after his death. On the other hand, Brecht considered all the possibilities that modern theater offered and incorporated them into the design of his plays. Here, too, he was dependent on the help of the appropriate specialists.

Poems

In his much-cited essay Kurzerbericht über 400 (four hundred) young poets from 1927, Brecht explained his conception of the “ use value ” that a poem must have. “[...] such 'purely' lyrical products are overrated. They are simply too far removed from the original gesture of communicating a thought or a sensation that is also advantageous for strangers ”. This and the documentary value that he attributed to a poem can be traced through all of his lyrical oeuvre. This was extraordinarily extensive, in the large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt editions there are around 2,300 poems, some of them in different versions. It was evidently a deep need for Brecht to reflect on every impression, every essential event, even every thought in poetry. About twenty new poems were written shortly before his death. The form is also extraordinarily varied, it ranges from inconsistent text to paired rhymes to classic hexameters .

Since many of Brecht's poems were written as a reaction to events in the outside world, i.e. in connection with specific occasions, the reader often sees them as occasional poems in the literal sense of the word , if he understands them that way . The “opportunity-relatedness” can be demonstrated both in Brecht's love poetry and in his political poems. The latter often arose from specific inquiries or at the request of anti-fascist circles (see also united front song ).

Even if modern research assumes that Brecht is the sole author of most of his poems, there was nonetheless collaboration with other artists, especially with composers, which was reflected in the works. Brecht always attached great importance to the setting of his poems, many of which were created directly as songs. It is assumed that there is or has been music for around 1000 texts. Brecht worked with Franz S. Bruinier , Hanns Eisler , Günter Kochan , Kurt Weill and Paul Dessau , among others .

Brecht published his first poems in 1913 in the school magazine Die Harvest . The first important publications are Bertolt Brecht's Hauspostille (published by Propylaen-Verlag in 1927 ) and The Songs of the Threepenny Opera (1928). In exile, the collections of Lieder, Gedichte, Choirs (1934 in Paris with notes after Hanns Eisler) and Svendborger Gedichte (1939 in London as preprint, editor Ruth Berlau ) were published. After the war, the anthology Hundred Poems was published in 1951, among others, and the War Primer was published in 1955 . The Buckower elegies , on the other hand, were only published individually, for example in experiments 12/54.

It is considered likely that still unknown poems by Brecht can be found, as only the titles of some are known. In 2002 in Berlin at an international fair for autographs, books and graphics, a previously unpublished handwritten poem with the title The Dead Plow was offered for sale.

Brecht's poems have been translated into numerous languages. Well-known translators in English-speaking countries are, for example, Eric Bentley , John Willett and Ralph Manheim . Miguel Sáenz is particularly important in the Spanish-speaking world .

Didactic pieces

The term Lehrstück is now used synonymously for teaching example , its origin in the field of practical art is largely unknown. It appears sporadically in Brecht's work and in unexposed places from around 1926.

It is assumed that he did not use the term as a classification term from the start. The didactic pieces developed as a type from around 1929 in connection with the music festival in Baden-Baden , Brecht himself included six of his works. Important first examples are the radio cantata Der Lindberghflug and Lehrstück as “community music”. With "community music", the audience was given the function of a choir and was supposed to sing along at certain points in the piece. From 1930 onwards, Brecht used “Lehrstück” as a genre designation. The new genre was controversial, so the premiere of Lehrstück in Baden-Baden ended with a scandal, but the approach of actively practicing art in community and in cooperation with many people was rated as avant-garde . Brecht's intentions went far beyond that. A politically oriented collectivity should develop out of community and practical art.

From around 1930 the genre experienced a brief upswing when school projects were also included, whereby the focus was always on collective practice, not eventual performance. The transitions to other genres such as school opera were not clearly delimited. In 1930, Der Jasager, a school opera with the participation of many Berlin students, was premiered for the first time in the 20th century. It was very successful and Brecht immediately took up tips from the students in order to revise the work. This later resulted in The Naysayer .

Brecht never lost his interest in the didactic pieces, neither in exile nor later in the GDR. However, since they were neither suitable to be produced on stockpile, nor were the conditions for reestablishing them in the post-war GDR, he gave priority to other tasks. In 1953 there was still a draft project The new sun as a lesson, which was related to the events of June 17th , but was not realized.

Films and scripts

Brecht's estate contains a large number of ideas, sketches and screenplays for films, only very few of which have been implemented.

From around 1920, Brecht began to be interested in film projects. These were initially drafts for advertising films, scripts for detective stories, a kind of alienated Robinsonade . In 1923 the short film (approx. 32 minutes) Mysteries of a Hairdressing Salon was made , a series of bizarre scenes for which Brecht is said to have written the screenplay (the film was long considered lost and was only found again in 1974 and painstakingly reconstructed). A contract that Brecht had concluded in 1930 with Nero-Film AG to film the Threepenny Opera was terminated by the latter and the film was completed without Brecht's collaboration. The first film in which he was largely able to implement his ideas was the 1931 film Kuhle Wampe or: Who Owns the World? . He wrote the script for this together with Slatan Dudow and Ernst Ottwalt . There were several censorship proceedings around the film, and from 1933 it was no longer allowed to be shown. In exile in the US, Brecht initially wrote numerous film texts without success. In his journal in 1942 he noted: "For the first time in ten years I have not done anything properly". This changed when he and Fritz Lang developed the concept for the film in 1942 , which later came out under the title Hangmen Also Die . Brecht's large share in the film was not properly valued until after 1998, when his contracts with Lang were discovered. After his return from exile, Brecht concentrated on filming existing works. In 1955, after a lot of quarrels, the plan to film the play Mother Courage at DEFA failed and he considered the filming of his play Herr Puntila and his servant Matti by the Austrian Wien-Film to be a failure. Further attempts by Brecht to push through his ideas at DEFA were unsuccessful.

reception

Various pieces by Brecht were already rejected during the Weimar Republic , such as Saint Joan of the slaughterhouses . The film Kuhle Wampe or: Who Owns the World? was heavily censored. Brecht's clear political positioning overshadowed the evaluation of his artistic work, even after his death. While he was blacklisted by the National Socialists as early as 1933, he was canonized in the GDR as a bourgeois intellectual who found his way to communism. In doing so, Brecht by no means subordinated himself to the official art and culture guidelines of the SED; in the arguments with the functionaries, however, he always looked for compromises.

Friedrich Torberg , together with Hans Weigel , implemented a boycott in Austria against the performance of Bertolt Brecht's works on the Vienna theaters, which lasted until 1963 ( Wiener Brecht boycott ).

In the Federal Republic of Germany, on the other hand, attempts were made for a long time to ignore Brecht's left-wing political involvement and were able to search through his pieces, mostly those from exile, largely calmly for timeless issues. Brecht's remarks on current political events also led to several boycotts of his plays in the Federal Republic. It was not until the 1980s that research began to work out the avant-garde in Brecht's work, his operas and didactic pieces, but also in his theoretical writings. After the German reunification , a more objective approach to his oeuvre became established .

During the upheavals of the 1960s, Brecht was also criticized by unorthodox left: Günter Grass throws in his play The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising Brecht, who is easy to see as "the boss" in the play before, the success of the revolt of the plebs to have been more interested on the stage than in the real workers' uprising on June 17th. At the same time, the piece shows the manipulability of the masses (in the case of Grass: by Brecht himself, who, contrary to his official program, constantly works with suggestions, i.e. does not make people think for themselves in the tradition of the Enlightenment ).

Friedrich Dürrenmatt criticizes Brecht's dramaturgy with the words: "Brecht thinks inexorably because he inexorably does not think of many things."

Brecht from the end of the 20th century

Bertolt Brecht's estate

His legacy is of outstanding importance for Brecht research . The entire estate that exists today is one of the most extensive literary estates in the German language. It contains more than 500,000 Brecht documents, including 200,000 manuscripts and manuscripts, and is on permanent loan to the archive of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin. The Brecht holdings are kept in the Bertolt Brecht Archives of the Academy in the Brecht House at Chausseestrasse 125 (10115 Berlin). The Brecht estate consists of the Bertolt Brecht Archive, founded as a private archive by his wife Helene Weigel on December 1, 1956, as well as various parts of the Brecht Collection Renata Mertens-Bertozzi and the Brecht Collection Victor N. Cohen and Brecht Collection of the then East Berlin Academy of the Arts: Two years after the death of Helene Weigel, the East Berlin Academy of the Arts merged the Berlin private archive in 1973 with the Brecht collections that already existed in the Academy. In 1992 these originals were given to the Akademie der Künste on permanent loan. The Brecht Collection Renata Mertens-Bertozzi and the Brecht Collection Victor N. Cohen were only acquired in 2004 and 2006, respectively.

Barbara Brecht-Schall , daughter of Helene Weigel and Bertolt Brecht, was his main heir and administrator of the estate. She died on August 31, 2015.

Brecht memorials

The Brecht Weigel Memorial , which opened on Brecht's 80th birthday on February 10, 1978 and today belongs to the Academy of the Arts, is located in the courtyard of the Brecht House at Chausseestrasse 125 (10115 Berlin), right next to the Dorotheenstadt cemetery, on the Bertolt Brecht and his wife Helene Weigel are buried. Bertolt Brecht lived in Chausseestrasse 125 (rear building, 1st floor) from October 1953 until his death on August 14, 1956. During this time, Helene Weigel lived on the second floor and moved to the ground floor in 1957, where she lived until her death on Lived on May 6, 1971. Most of the apartments have been preserved in their original condition. In addition to Brecht's estate, the Helene Weigel archive is also located there .

The “ Brechthaus ” memorial has also been located in Brecht's birthplace in Augsburg since 1990 . In this city there are numerous points of contact to Brecht's biography and work; The Brecht Festival is also regularly held here (every three years from 1995, annually since 2006). With a view to Augsburg's ambivalent handling of Brecht, the cultural journalist Ralf Hutter speaks of a “return of the prodigal son”.

The house in Svendborg, in which Brecht stayed on his escape in Denmark, is made available by the local Brecht Association under the name "Brechts hus" as an artist and researcher apartment.

There is also a memorial in Buckow in Märkische Schweiz, not far from Berlin: The Brecht-Weigel-Haus is partially open to the public and commemorates the author of the Buckower elegies with exhibitions and events .

Inherit

When Helene Weigel died in 1971, Brecht's children, Stefan Brecht , Hanne Hiob and Barbara Brecht-Schall , who had meanwhile died, took over the rights to Brecht's work. According to German copyright law, these will expire in 2027. Stefan Brecht was the authorized heir who also took care of the granting of rights in English-speaking countries. Barbara Brecht-Schall took on the same tasks for the German-speaking area, Hanne Hiob was granted the right to advise. According to their own admission, the heirs were particularly keen to ensure that the pieces were faithful to the work and that the tendency of the pieces was adhered to, but they did not want to have any direct influence on the artistic design of the productions. Confrontations between the rights holders and those responsible for the theater were the exception, as was the case in 1981, when the performance of a production of the play The Good Man by Sezuan by the director Hansgünther Heyme was prohibited. In addition, the heirs also paid attention to publications about the father, his activities and the family. When John Fuegi published his biography The life and lies of Bertolt Brecht in 1994 , there were numerous arguments between the author and the Brecht heirs. Barbara Brecht-Schall "recently prohibited a further performance of Brecht's play 'Baal', directed by Frank Castorf, at the Munich Residenztheater because of interfering with the original text."

Awareness survey

“The greatest playwright of the 20th century”, said Marcel Reich-Ranicki about him, was (in the meantime), statistically speaking, little known in Germany, according to the interpretation of a representative study (from the literary magazine “ bücher ” at the Gewis Institute) at the age of 50 Day of death in 2006. 55 percent only had contact with Brecht's work while they were at school, and only two percent read something about it this year or last. 42 percent of German citizens have never had it or do not remember it. Brecht's biography is also unknown to most Germans. Eight percent know that he founded the Berliner Ensemble. Three percent mistakenly think of the Berlin Schaubühne, the other 89 percent have no idea which theater Brecht could have founded (1,084 women and men between 16 and 65 years of age were surveyed).

The Suhrkamp publishing house replied: “Which German author is still sold 300,000 times a year today? […] [On the survey and its interpretation] it should at least be noted that the alleged survey results […] can also be interpreted and commented on exactly the other way around: 55 percent of those surveyed read Brecht's works during their school days. Which author can this be said of? So far, Suhrkamp Verlag has sold over 16.5 million books by Bertolt Brecht, with an average of 300,000 copies being added each year. His work has been translated into over 50 languages. And Brecht is still a leader on the repertoire of German theaters. "

factories

Pieces

| piece | Emergence | First publication in print form | World premiere of the first version |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Bible. Drama in 3 scenes | 1913 | 1914 in The Harvest | February 8, 2013 Augsburg |

| Baal | 1918 | 1922 | December 8, 1923 Leipzig |

| Drums in the night | 1919 | 1922 Kiepenheuer | September 29, 1922 Munich |

| The wedding , also the petty bourgeois wedding (one-act) | 1919 | December 11, 1926 Frankfurt / M | |

| He casts out a devil (one act) | 1919 | 1966 Suhrkamp | October 3, 1975 Basel |

| Lux in Tenebris (one act) | 1919 | ||

| The beggar or the dead dog (one act) | 1919 | ||

| The fish haul (one-act play) | 1919 | ||

| Prairie (opera libretto) | 1919 | 1989 Suhrkamp, GBA | 1994 Rostock |

| In the thicket of the cities also in the thicket | 1921 | 1927 Propylaea | May 9, 1923 Munich |

| Life of Edward II of England | 1923 | 1924 Kiepenheuer | March 18, 1924 Munich |

| Hannibal (fragment) | 1922 | ||

| Man is man | [1918] -1926 | 1927 Propylaea | September 25, 1926 Darmstadt and Düsseldorf |

| Fatzer (fragment), also the downfall of the egoist Johann Fatzer | 1927-1931 | 1930 Kiepenheuer | 1975/1976 Stanford |

| Jae Meat Chopper in Chicago (fragment) | 1924-1929 | BFA Volume 10.1 Suhrkamp 1997 | |

| Mahagonny (song game) | 1927 | 1927 | July 17, 1927 Baden-Baden |

| The rise and fall of the city of Mahagonny (opera libretto) | 1927-1929 | 1929 | March 9, 1930 Leipzig |

| Berliner Requiem (small cantata for three male voices and wind orchestra) | 1928 | 1967 David Drew | February 5, 1929 Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft Berlin |

| The Threepenny Opera | 1928 | 1928 | August 31, 1928 Berlin |

| The ocean flight , also The Lindbergh flight , also The flight of the Lindberghs | 1928 | 1929 in Uhu | July 17, 1929 Baden-Baden as a radio cantata |

| The Baden lesson on consent , also lesson | 1929 | 1929 Baden-Baden | |

| The yes-man . The naysayer (opera libretti / didactic pieces [school opera]) | 1929-1930 | 1930 | July 23, 1930 Berlin |

| The measure (lesson) | 1930 | 1930 | 13./14. December 1930 Berlin |

| Saint Joan of the slaughterhouses | 1929 | 1931 | April 30, 1959 Hamburg |

| The bread shop (fragment) | 1929-1930 | 1967 Berlin | |

| The exception and the rule (didactic piece) | 1931 | 1937 Moscow | May 1, 1938 Givath Chajim |

| The mother | 1931 | 1933 | January 17, 1932 Berlin |

| The round heads and the pointed heads | 1932-1936 | 1932 | November 4, 1936 Copenhagen |

| The seven deadly sins , also the seven deadly sins of the petty bourgeoisie (ballet libretto) | 1933 | June 7, 1933 Paris | |

| Safety first | 1934 | ||

| The Real Life of Jakob Gehherda (fragment) | 1935? | ||

| The Horatians and the Curiatians (lesson) | 1935 | 1936 Moscow | April 26, 1958 Halle / S |

| Mrs. Carrar's rifles | 1936-1937 | 1937 London | October 16, 1937 Paris |

| Goliath (fragment - opera libretto) | 1937 | ||

| Fear and Misery of the Third Reich | 1937-1938 | 1938 Moscow | May 21, 1938 Paris |

| Life of Galileo | 1938-1939 | 1948 Suhrkamp | September 9, 1943 Zurich |

| Dansen (one act) | 1939? | ||

| What does the iron cost? (One act) | 1939 | August 14, 1939 Tollare near Stockholm | |

| Mother Courage and her children | 1939 | 1941 | April 19, 1941 Zurich |

| The interrogation of Lucullus (radio play), later The condemnation of Lucullus (opera libretto) | 1939 | 1940 Moscow | 1940 Beromünster transmitter (Berlin Opera 19.3 / 12 October 1951) |

| The good man from Sezuan | 1939 | 1953 | February 4, 1943 Zurich |

| Mr. Puntila and his servant Matti | 1940 | 1948? 1950 in trials | June 5, 1948 Zurich |

| The resilient rise of Arturo Ui | 1941 | 1957 | November 10, 1958 Stuttgart |

| The face of Simone Machard also The Voices (see Lion Feuchtwanger Simone ) | 1941 | 1956 Sense and Form | March 8, 1957 Frankfurt / M |

| Schweyk in World War II | 1943 | 1947 in Ulenspiegel | January 17, 1957 Warsaw |

| The Duchess of Malfi (After John Webster ) | 1943 | October 15, 1946 New York | |

| The Caucasian chalk circle | 1944 | 1949 Sense and Form | [May 1948 USA na] May 23, 1951 Gothenburg |

| Editing Sophocles - Antigone | 1947 | February 15, 1948 Chur | |

| The days of the Commune | 1949 | 1957 | 1956 Karl-Marx-Stadt |

| Adaptation Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz - Der Hofmeister | 1949 | 1951 | April 15, 1950 Berlin |

| Editing Gerhart Hauptmann - beaver fur and red rooster | 1950 | March 24, 1951 Berlin | |

| Adaptation William Shakespeare - Coriolanus | 1951-1955 | 1959 Suhrkamp | September 22, 1962 Frankfurt / M |

| Adaptation Anna Seghers - The Trial of Joan of Arc in Rouen 1431 | 1952 | 1952 Berlin | |

| Turandot or The White Washer Congress | 1953 | 1967 | February 5, 1969 Zurich |

| Arrangement Molière - Don Juan | 1952 | 1952 Rostock | |

| Timpani and Trumpets (after George Farquhar ) | 1954 | 1959 Suhrkamp | September 19, 1955 |

Origin of the data:

- Unless otherwise stated, Jan Knopf's Brecht-Handbuch 2001 is the source for the data.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Werner Hecht (Ed.): Everything that Brecht is ... facts - comments - opinions - pictures. Frankfurt am Main 1997.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Bertolt Brecht: Large commented Berlin and Frankfurt edition. Suhrkamp 1988-1999.

- ^ A b Bertolt Brecht: Selected works in 6 volumes. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1997.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Ana Kugli, Michael Opitz (ed.): Brecht Lexikon. Stuttgart / Weimar 2006.

- ↑ a b c Werner Hecht: Brecht Chronicle 1998–1956. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1998.

The year of creation is only to be understood as a guide, as Brecht reworked most of his pieces several times. Data that are controversial in research are marked with question marks.

Poetry

Poetry collections

| Serial No. | Poetry collection | Number of poems | Emergence | First printing | Reorganization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Songs for the guitar by Bert Brecht and his friends | 7 (8) | 1918 | 1988 GBA | |

| 2. | Psalms | 19 (23) | 1920 | 1960 | 1922 |

| 3. | Bertolt Brecht's house mail | 48 (52) | 1916-1925 | 1926 Kiepenheuer PD | 1937, 1956 |

| 4th | The Augsburg sonnets | 13 | 1925-1927 | 1982 | |

| 5. | The songs of the Threepenny Opera | 17 (20) | 1924-1928 | 1928 Kiepenheuer | 1937, 1946-1948 |

| 6th | From the reader for city dwellers | 10 (21) | 1926-1927 | 1930 in trials | 1938 |

| 7th | Stories from the revolution | 2 | 1929-1931 | 1933 in trials | |

| 8th. | Sonnets | 12 (13) | 1932-1934 | 1951, 1960, 1982 | |

| 9. | English sonnets | 3 | 1934 | ||

| 10. | Songs poems choirs | 34 (38) | 1918-1933 | 1934 Editions du Carrefour | |

| 11. | Hitler chants | 4th | 1933 | (included in songs poems choirs ) | |

| 12th | Chinese poems | 15th | 1938-1949 | ||

| 13. | Studies | 8th | 1934-1940 | 1951 in trials | |

| 14th | Svendborg poems | 93 (108) | 1934-1938 | 1939 | |

| 15th | Steffin's collection | 23 (29) | 1939-1940 | 1948 construction | 1942, 1948 |

| 16. | Hollywood Elegies | 9 | 1942 | 1988 GBA | |

| 17th | Poems in exile | 17th | 1936-1944 | 1988 GBA | 1949, 1951 |

| 18th | War Primer | 69 (86) | 1940-1945 | 1955 Eulenspiegel | 1944, 1954 |

| 19th | German satires (second part) | 3 | 1945 | 1988 GBA | |

| 20th | Nursery rhymes / new nursery rhymes | 9/8 | 1950 | 1953 construction | 1952 |

| 21. | Buckower Elegies | 23 | 1953 | 1964 | |

| 22nd | Poems from buying brass | 7th | 1935-1952 | 1953 in trials | |

| 23 | Poems about love | 76 | 1917-1956 | 1982 | |

| 24. | A hundred poems. 1918 to 1950 | 100 | 1918-1950 | 1958 |

Origin of the data: Bertolt Brecht: Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt edition. Suhrkamp 1988-1999.

The number of poems in brackets also adds up the poems that have been added or dropped through rearrangement or addition. The dates indicate the period in which the main poems of the collection were written; there were in some cases later changes / additions as well as new compilations by the author using older poems.

Selected poems and songs

- Alabama song

- To those born later

- The Anachronistic Train or Freedom and Democracy

- The Song of the Vltava

- The tailor from Ulm

- The solution

- The Ballad of Mack the Knife

- The pirate Jenny

- United front song

- Memory of Marie A.

- Questions from a reading worker

- Children's anthem

- Legend of the dead soldier

- Legend of the origin of the book Taoteking on the Laotse's path to emigration

- To read in the morning and in the evening

- resolution

- Bad time for poetry

- Solidarity song for the film Kuhle Wampe

Selected prose

- Bargan lets it be. In the magazine “Der Neue Merkur”, monthly magazine, Munich 1921.

- The Augsburg Chalk Circle . In “Internationale Literatur” magazine, Moscow 1941.

- The business of Mr. Julius Caesar .

- The unworthy old woman .

- The beast .

- Threepenny novel. Publisher Allert de Lange , Amsterdam 1934th

- Refugee talks.

- Stories from Mr. Keuner .

- Calendar stories .

Radio plays

- 1927: Man is man - with Ernst Legal ( Funk-Hour Berlin )

- 1927: Macbeth by Bertolt Brecht and Alfred Braun based on Shakespeare, directed by Alfred Braun ( Funk-Hour Berlin )

- 1928: Calcutta - May 4th by Bertolt Brecht and Lion Feuchtwanger , directed by Fritz Walter Bischoff ( Schlesische Funkstunde Breslau)

- 1929: Der Flug der Lindberghs by Bertolt Brecht, composition: Paul Hindemith / Kurt Weill, director: Ernst Hardt (WERAG)

- 1931: Hamlet by Bertolt Brecht based on Shakespeare, composition: Walter Gronostay , director: Alfred Braun ( Funk-Hour Berlin )

- 1932: Saint Joan of the slaughterhouses - also director ( Funk-Hour Berlin )

- 1940: Lukullus in court by Bertolt Brecht (Radio Beromünster, Switzerland)

- 1949: The interrogation of Lukullus by Bertolt Brecht, composition: Bernhard Eichhorn , director: Harald Braun ( BR )

- 1966: The interrogation of Lukullus - Director: Kurt Veth ( Deutschlandsender )

- 1969: The Ocean Flight - Director: Kurt Veht / Tilo Medek ( Radio DDR I )

- 1988: Fall of the egoist Fatzer - music: Einstürzende Neubauten , director: Heiner Müller ( radio of the GDR )

Fragments and piece projects

In addition to the fragments already listed under pieces , there are numerous other different genres, the following selection is alphabetical:

Alexander and his soldiers, Nothing becomes nothing, Büsching [Garbe], Chinese patricide, Dan Drew, Dante-Revue, David, The evil Baal the asocial, The bridge builder, The green Garraga, The impotent, The chariot of Ares, The bellows , The Judith von Shimoda , The Neanderthals, Eisbrecher Krassin, Galgei, Goliat, Gösta Berling, Hans im Glück, Mr. Makrok, Life of Confutse, Life of the philanthropist Henri Dunant, Life of Einstein, Man from Manhattan, Me-ti. Book of Twists , Oratorio, Park Gogh, Popess Johanna, Pluto, Revue, Rosa Luxemburg, Journeys of the God of Fortune, Ruza Forest, Salzburg Dance of Death, Deluge, Exercise Pieces for Actors, Small Organon for the Theater, Songs, Poems, Choirs, The Interrogation of Lucullus, The threepenny novel

Work editions

- Collected works in 20 volumes, writings on politics and society. Work edition Edition Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1967.

- Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt edition. 30 volumes (in 32 sub-volumes) and one index volume. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1988–2000 ( list of volumes )

- All the pieces in one volume. Comet, 2002, ISBN 3-89836-302-3 .

- The poems in one volume. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-518-02269-5 .

- Stories from Mr. Keuner. Zurich version. Edited by Erdmut Wizisla. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-518-41660-X (Contains first published stories from a Zurich find in 2000.)

-

Notebooks . Edited by Martin Kölbel and Peter Villwock, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, later Berlin, since 2010 ("The Electronic Edition (EE) supplements and substantiates the book edition.").

- Notebooks. Volume 1: 1918–1920 , Frankfurt am Main 2012, ISBN 978-3-518-42299-1 .

- Notebooks. Volume 2: 1920 , Frankfurt am Main 2014, ISBN 978-3-518-42431-5 .

- Notebooks. Volume 3: 1921 , Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-518-42596-1 .

- Notebooks 13–15. Volume 4: 1921–1923 , Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-518-42884-9 .

- Notebooks 16-20. Volume 5: 1924-1926 , Berlin 2021, ISBN 978-3-518-42987-7 .

- Notebooks. Volume 7: 1927–1930 , Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 978-3-518-41971-7 .

See also

- Anachronistic move

- Bertolt Brecht Literature Prize

- Brecht's radio theory

- Exile literature

- Carola Neher

- Wolfgang Staudte

- Peter Voigt

- List of banned authors during the Nazi era

literature

Biographies

- Günter Berg, Wolfgang Jeske: Bertolt Brecht. Metzler Collection. Metzler, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-476-10310-2 .

- John Fuegi : Brecht & Co. Translated and corrected by Sebastian Wohlfeil. EVA, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-434-50067-7 .

- Werner Hecht : Brecht Chronicle. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-518-40910-7 .

- Jürgen Hillesheim : Bertolt Brecht's Augsburg stories. Biographical sketches and pictures. Augsburg 2004, ISBN 3-938332-01-8 .

- Jürgen Hillesheim: Bertolt Brecht - First love and war. With a previously unknown text and unpublished photos. Augsburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-938332-11-5 .

- Reinhold Jaretzky : Bertolt Brecht. (= rororo monographs. Volume 50692). Rowohlt, Reinbek 2006, ISBN 3-499-50692-0 .

- Sabine Kebir : An acceptable man? Dispute over Bertolt Brecht's partner relationships. Der Morgen, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-371-00091-5 .

- Sabine Kebir: An acceptable man? Brecht and the women. Pahl-Rugenstein, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-7609-7028-1 ; Structure paperback, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-7466-8028-X .

- Marianne Kesting : Bertolt Brecht with self-testimonials and photo documents. Hamburg 1959; Rowohlt, Reinbek 2003, ISBN 3-499-50037-X .

- Jan Knopf : Bertolt Brecht - the art of living in dark times: biography. Hanser Verlag, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-446-24001-8 .

- Jan Knopf: Bertolt Brecht. (= Suhrkamp BasisBiographie. 16). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-518-18216-1 .

- Werner Mittenzwei : The Life of Bertolt Brecht or Dealing with the World Riddles. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 2002, ISBN 3-518-02671-2 .

-

Stephen Parker : Bertolt Brecht: a literary life. Bloomsbury, London et al. 2014, ISBN 978-1-4081-5562-2 .

- German translation by Ulrich Fries and Irmgard Müller: Bertolt Brecht: Eine Biographie. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-518-42812-2 .

- Anthony Squiers: An Introduction to the Social and Political Philosophy of Bertolt Brecht: Revolution and Aesthetics. Rodopi, Amsterdam 2014, ISBN 978-90-420-3899-8 .

- Klaus Völker : Bertolt Brecht, A Biography. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1988, ISBN 3-499-12377-0 .

miscellaneous

- Bertolt Brecht. In: Heinz Ludwig Arnold (Ed.): Kindlers Literature Lexicon . 3rd completely revised edition. 18 bde. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2009, ISBN 978-3-476-04000-8 , Vol. 3, pp. 92-123

- Louis Althusser : About Brecht and Marx . 1968.

- Christine Arendt: Nature and Love in Brecht's Early Poetry. Peter Lang, Frankfurt / M. 2001, ISBN 978-3-631-37813-7 .

- Hannah Arendt Bertolt Brecht. In: people in dark times. Piper, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-492-23355-4 , pp. 237-283. (Also in: Hannah Arendt: Walter Benjamin - BB- Two Essays. Piper, Munich 1971, pp. 63-107).

- Michael Bienert : Brechts Berlin. Literary scenes , Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-947215-27-0 .

- Bernd-Rainer Barth , Andreas Kölling: Bertolt Brecht . In: Who was who in the GDR? 5th edition. Volume 1. Ch. Links, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86153-561-4 .

- Wendula Dahle (ed.): The business with poor BB From vilified communist to top-class German poet. VSA-Verlag, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-89965-209-6 .

- Franz-Josef Deiters : "'The event took place, here the repetition takes place'. Bertolt Brecht's Epic Theater". In: Franz-Josef Deiters: Secularization of the Stage? On the mediology of the modern theater. Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag, 2019. ISBN 978-3-503-18813-0 , pp. 133-169.

- Albrecht Dümling : Don't let yourself be seduced. Brecht and the music , Munich 1985, ISBN 3-463-40033-2 .

- Helmut Fahrenbach : Bertolt Brecht - Philosophy as a theory of behavior . Mössingen-Talheim: Talheimer Verlag, 2018. ISBN 978-3-89376-177-7 .

- Christoph Gellner: Brecht, Bertolt. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 31, Bautz, Nordhausen 2010, ISBN 978-3-88309-544-8 , Sp. 193-208.

- Günter Grass : The plebeians are rehearsing the uprising . A German tragedy. Steidl , Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-88243-934-3 . (First published in 1966)

- Werner Hecht: The troubles of the plains. Brecht and the GDR. Construction Verlag, Berlin, 2014, ISBN 978-3-351-03569-3 .

- Hans-Christian von Herrmann: Sang of the machines. Brecht's media aesthetics. Fink , Munich 1996, ISBN 3-7705-3107-8 .