Duchy of Cleves

|

Territory in the Holy Roman Empire |

|

|---|---|

| Duchy of Cleves | |

| coat of arms | |

|

|

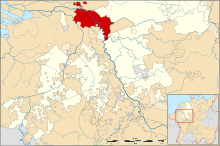

| map | |

|

|

| Map of Kleve, Berg, Mark and Jülich in the 14th century | |

| Alternative names | Cleef, Kleef, Cleve, Clèves |

| Arose from | Duisburggau |

| Form of rule | County , from 1417 duchy |

| Ruler / government | Count / Duke |

| Today's region / s | DE-NW |

| Parliament | for Kleve with Mark : Reichsfürstenrat , Secular Bank: 1 virile votes ; 3 votes in Städterat , Rhenish Bank for Duisburg , Soest , Wesel |

| Reich register | 45 horsemen, 270 foot soldiers, 500 guilders (1522, for Kleve with marks ) |

| Reichskreis | Lower Rhine-Westphalian Imperial Circle |

| Capitals / residences | Kleve , Kalkar |

| Dynasties | Kleve, Mark , Brandenburg-Prussia |

| Denomination / Religions | Roman Catholic |

| Language / n | Dutch , Kleverland |

| surface | 1,200 km² (end of 18th century) |

| Residents | 100,000 (late 18th century) |

| Incorporated into | Left of the Rhine: France, Département de la Roer , right of the Rhine: Grand Duchy of Berg

|

The Duchy of Kleve (also Cleve ) was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation in the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Circle on both sides of the Rhine between the Duchy of Münster , the Imperial Monastery of Essen , the Duchies of Berg , Jülich and Geldern and the Electorate of Cologne . Kleve existed as a county since around 1020 and was elevated to a duchy in 1417. The seat of the ruler was the Schwanenburg in the city of Kleve , and at times also Monterberg Castle near Kalkar . From 1614 the duchy belonged to Brandenburg-Prussia .

geography

The Duchy of Kleve covered an area of 2,200 km² through which the Rhine and its tributaries Ruhr , Emscher , Lippe and the Gelders IJssel as well as the Maas and its tributary Niers flow through. It had 100,350 mostly Catholic residents ( including the county of Moers ). The medieval territory was predominantly on the territory of today's Federal Republic and to a lesser extent on the territory of today's Netherlands. It roughly comprised today's area of the districts of Kleve (north), Wesel , the northern part of the independent city of Oberhausen and the independent city of Duisburg .

Cities

The Duchy of Kleve included the towns of Kleve , Wesel , Emmerich , Rees , Kalkar , Xanten , Duisburg , Kranenburg , Gennep , Griethausen , Grieth , Goch , Uedem , Kervenheim , Sonsbeck , Büderich , Orsoy , Huissen , Zevenaar , Isselburg , Dinslaken , Schermbeck , Holten and Ruhrort .

Offices

The Duchy of Kleve was subdivided into countries and offices, which were mostly named after cities, for example the Land Kleve , the Land Dinslaken and the Land Kranenburg . Exceptions to this are the offices of Aspel , Düffel , Hetter , Kleverhamm and Liemers .

history

County of Kleve

Beginnings of the county

Almost no reliable information is available about the local balance of power in the area of “Kleve” in the early Middle Ages . The few statements made by some historians on this are also controversial. According to one of these sources, after 711, a daughter from a noble family named Beatrix married Count Aelius (or Helios) Gralius, who was a follower of Karl Martell . This count owned areas in the Teisterbant area as a fief. The son from this marriage was as Theodoric I from 742 both Count of Teisterbant and the first Count of Cleve. Counties Teisterbant and Cleve were divided among the descendants. The last descendant from this noble family in Cleve was Count Nufried , after whose death in 1008 this family went out.

A "Beatrix" from a noble house is also named in a legend or fairy tale as the ancestor of the Counts of Kleve, who married a swan knight Elias. Since the 15th century at the latest, the Klever counts and dukes have derived their origins from this swan knight Elias (Aelius = Elias?), Who is related to the figure of Lohengrin .

At the beginning of the High Middle Ages there is verifiable information for the area in the Kleve area. On the Lower Rhine between the Meuse and the Rhine, around 1020, Emperor Heinrich II gave territories to two brothers from Hainaut in Flanders as fiefs . One, "Gerhard Flamens" , became the progenitor of the Counts of Wassenberg , the later counts and dukes of the Duchy of Geldern , and the other, "Rutger or Rütger Flamens" , the progenitor of the Counts of Kleve. The starting point of the Klevian rule was probably only a small area in the Kleve area. For the first time in 1092 a count named himself after Kleve Castle . The core area of the Klevian rule was initially the area between Kleve and Kalkar . Here the counts founded the Wissel and Bedburg monasteries .

Only a few verifiable data for Rütger I. are known. This also applies to the next successors up to the beginning of the 13th century. According to a chronicle from the 14th century, Rütger's son Dietrich I (also called Theodoric) is said to have been heir. After the death of the ruling count, their sons Dietrich II. And Dietrich III. the line of succession. For these, too, the available data are partly contradictory. For Count Dietrich III. there is evidence that from 1096 he received Tomburg Castle with the associated area as a vassal of the Archbishop of Cologne. Therefore, at the beginning of the 12th century, the name in documents changed for some time between Graf von Kleve and Graf von Tomburg.

With the son of Dietrich III., Arnold or Arnulf I named, a term of office from 1117 to 1135 was given for the first time in the older chronicle. According to this chronicle, the next reigning count from 1135 to 1150 was the son Arnold II. This is followed by the other counts who are included in the list below "Rulers of Kleve / House of Kleve until 1368". The names and dates of the first counts given above differ from this list. The information given is taken from the older "Clevische Chronik", insofar as it provides evidence.

Development of the county

The development of the important noble houses in the High Middle Ages often took place through the additional position of a bailiff for monasteries and abbeys. These bailiffs, who were responsible for the secular affairs of these religious institutions, were able to expand their power base and their area of fief. Since 1117 the Counts of Kleve were bailiffs of the Zyfflich monastery , in 1119 they became bailiffs of the Fürstenberg monastery . Between 1122 and 1299 they also took control of the bailiwick of the important Viktorstift in Xanten . Through the marriage of Count Arnold I to Ida von Brabant , the Counts of Kle came into possession of Wesel in the first half of the 12th century , which became the starting point for further acquisitions on the right bank of the Rhine. In the 13th century the territorial-political activities of the counts acquired a new quality, as the chain of founding cities from 1241 and the extensive internal colonization show.

The inheritance divisions common up to the end of the 13th century proved to be a threat to the Klever territory. So was Count Dietrich V./VII. at times in conflict with his younger brother Dietrich Luf I. He could not realize his claims to the county of Saarbrücken, which he traced back to his marriage to a daughter from this noble house. Therefore, he raised further inheritance claims for the area of Kleve, which his brother, the incumbent Count of Cleve, did not meet.

The legacy of Count Dietrich V./VII led to another conflict. from Kleve. In 1257 he married Alinde (or Aleidis ), the daughter of Heinrich von Heinsberg . As a result, the county of Hülchrath came under the rule of the "Klever". When the inheritance was divided, the younger son of the count, Dietrich Luf II , received the territories of his mother and thus also Hülchrath. In 1290 the imperial city of Duisburg was pledged to the Counts of Kleve. The pledge was never released after that, so that Duisburg became a Klevian country town with this pledge.

Since Luf II was taken prisoner in the battle of Worringen on the part of the Archbishop of Cologne, the count had to buy himself out with a large ransom. Due to the financial shortage caused by this, his son Dietrich Luf III sold. April 26, 1322 unwillingness of the current counts of Kleve for 15,000 marks the county Hülchrath at the Cologne Archbishop Henry II. Since initially only 9,030 marks were paid from the sale price, set Electorate of Cologne for the remaining sum as pledges: castle and town Aspel, Rees, Xanten and Kempen with the associated areas. On November 16, 1331, the Klevern acknowledged that the remaining sum had been paid out in the meantime and that the sale was thus completed.

After the death of Count Dietrich VI. 1305 ruled successively by his son Otto from his first marriage until 1310 and then the eldest son from his second marriage, Dietrich VII./IX. When Dietrich died in 1347, his younger brother Johann followed as Count von Kleve. Johann supported Rainald III. von Geldern in his quarrel with his brother Eduard. Rainald III. Due to lack of funds, Emmerich pledged Johann in 1355. Since the deposit was no longer released, Emmerich has belonged to the territory of Kleve since that time. When Johann died in 1368, there was no longer a male heir, as none of the three brothers had any legitimate sons. With Johann, the previous ruling house of the "noble family Flamensis" in the county of Kleve died out.

After Johann's death, his great-nephew Adolf III. von der Mark , the former bishop of Münster and Elekt of Cologne, successor as Count Adolf I of Kleve. He had to assert himself against other applicants. He was supported in his successor by the Duke of Brabant and his brother Count Engelbert von der Mark . The latter received the Grafschaft Mark for life. Another brother of Adolf III, Dietrich , received Dinslaken and the associated areas for his support and, in 1392, Schwelm , Duisburg and Ruhrort.

Adolf I von Kleve supported Charles the Bold in the conquest of the Duchy of Geldern from 1473. For his military services, he received not only financial reimbursement but also significant assignments of territory at the expense of funds. The previous right of lien for Emmerich, part of the Liemers and the Düffel was converted into a real right of ownership. In addition, Goch, Wachtendonk and the Bailiwick of Elten were now part of the County of Kleve.

One of the strongest opponents against the expansion of power for the county of Kleve through the personal union with the county of Mark was the archbishop of Cologne, Friedrich III. In 1373 the archbishop pledged the castle, town and customs of Rheinberg by the payment of 55,000 gold shields to Count Adolf, but after that the relations between Kleve and the archbishopric of Cologne deteriorated. In addition, according to the archbishop, the county of Kleve was a fiefdom of the archbishopric. A 14-year feud between Adolf I and the archbishop began in 1378 around the Klevian Linn and its associated area.

Towards the end of his life, Count Adolf von Kleve prepared the inheritance for his descendants and tried to end existing conflicts. One of these disputes was with Archbishop Friederich III. about the affiliation of Linn. In 1392 he contractually renounced the hereditary ownership of the castle, town and country of Linn in favor of the Archdiocese of Cologne. In return, the count was to receive 70,000 guilders. 13,000 guilders were paid in cash. The cities of Aspel and Rees as well as half of the Bockum court and the city of Xanten as well as farms in Schwelm and Hagen were pledged by the archbishop for the 57,000 guilders .

When, with the death of his brother Engelbert, the county of Mark on the right bank of the Rhine fell to Adolf in 1392 and the dual counties of Kleve and Mark came into being, the feud with Cologne was finally over. Even before his death in 1394, Adolf solved the problems with his younger son Dietrich and in 1393 transferred the reign there as Count von Mark.

He was succeeded as Count von Kleve in 1394 by his older son Adolf II. There was a dispute between Adolf II of Kleve and Dietrich II of Mark on the one hand and Duke Wilhelm II of Jülich-Berg on the other. The dispute concerned an annual pension of 2,400 gold guilders from the Rhine toll at Kaiserswerth , to which both sides claimed. When there was no agreement, the duke moved to the county of Kleve with an army of knights. In the battle of Kleverhamm on June 7th 1397 the duke was defeated and taken prisoner. The power position of the County of Kleve was strengthened compared to the Duchy of Jülich-Berg, as the Duke had to raise considerable sums of money for his release and the duchy was weakened as a result. When Dietrich was killed in a feud in 1398, Kleve was again united with the county of Mark. Through the marriages of Adolf II's daughters with the Roman-German King Ruprecht of the Palatinate and Duke Johann Ohnefurcht von Burgundy, Count Adolf II was able to further expand his position of power on the Lower Rhine. The consequence was the elevation to the ducal status in 1417 and the rise of the county into a "Duchy of Kleve".

Duchy of Cleves

During the reign of Count Adolf II , the Roman-German King Sigismund appointed him “Duke Adolf I of Kleve and von der Mark” in 1417 and elevated the county of Kleve to a duchy . During his reign, the duke succeeded in expanding the clever territory and largely dissolving the dependence on the Archdiocese of Cologne. After he had already acquired Emmerich with parts of the Liemers (1402) from the Duchy of Geldern as a non-repaid pledge, other Geldrische areas followed with the Reichswald between Nijmegen and Kleve (1418), Gennep (1424), Wachtendonk (1440, but only temporarily) and Duffel (1446). The basis of the acquisition for the territories and local areas were pledge agreements.

Adolf was involved in decades of disputes with his younger brother Gerhard , because he did not agree to the inheritance of the entire inheritance for the firstborn . From 1409 Gerhard therefore claimed to take over the inheritance for the county of Mark. In addition, there were problems with Archbishop Dietrich von Moers , who tried to prevent an increase in power for the Duke, as Kleve was still a Cologne fief in the archbishop's opinion.

From 1423 there was therefore a feud between the Archbishop of Cologne and Adolf I. In this feud, Gerhard initially supported the archbishop. In 1437 an agreement was reached between Adolf and his brother Gerhard for his claim to the county of Mark. Gerhard received the reign for the greater part of the territories in the county and carried the title "Graf zur Mark", while Adolf continued to use the title "Graf von der Mark".

The dispute with the archbishop intensified over time and led to the Soest feud from 1444 to 1449 . The trigger for this feud was that the city of Soest tried to free itself from the sovereignty of the Cologne Archdiocese. The city therefore concluded a contract with Duke Adolf I in 1444 that the Klever instead of the Cologne should have the authorities in Soest. The duke called his son Johann from the court in Burgundy for the armed conflicts that broke out and gave him military leadership. Before the end of the war, Adolf I died in 1448, and his son Johann succeeded him as Duke Johann I von Kleve-Mark.

Under Johann the feud ended in a defeat for the archbishop. During the peace negotiations, among other things, Erzköln had to renounce the feudal responsibility for the Duchy of Kleve. The change of responsibility for the city of Soest was also recognized and the city was now under the Duchy of Kleve. In addition to Soest, Xanten also switched from Cologne to the supremacy of Klever.

After the end of the first feud in Soest, the arguments between the Archbishop and the Duke of Kleve were not over. Duke Johann I supported in the Munster collegiate feud from 1450 to 1458 the side that argued with the Cologne bishop about the occupation of the bishop's seat in Munster. A second "Soest feud" followed from 1462/63 and the disputes from 1467 to 1469. For the disputes from 1467 onwards, the Archbishop of Cologne , Ruprecht von der Pfalz, had allied with funds and tried to regain suzerainty over Soest, Xanten and Rees gain.

From the beginning of the 1470s, Duke Johann I allied with Charles the Bold and supported the latter in taking power in the Duchy of Geldern. Since these disputes over funds for Charles the Bold ended successfully, Johann I was one of the winners. To thank the Duke of Kleve, the Burgundian signed the city and office of Goch and the Rhine toll to Lobith as well as the bailiwick of the Elten monastery, the parish of Angerlo and the district and city of Emmerich.

In addition to the above-mentioned acquisitions, Soest, Xanten and Rees were finally secured for Kleve, since the position of the Archbishopric of Cologne on the Lower Rhine had now been permanently weakened.

Adolf II and his son Johann I were already supported by the respective Duke of Burgundy in the disputes with Erzköln. As a result, Kleve came under the strong influence of the Duchy of Burgundy at times in the second half of the 15th century .

John I's successor after his death in 1481 was his son, Duke Johann II. His initial attempt to break away from the influence of Burgundy failed. With increasing reign, the Duke's relationship to the estates in Kleve and in the Mark also deteriorated, as his financial claims were only granted against ever increasing resistance due to his unsuccessful policies and mismanagement in the duchy. From 1501 the estates reached a contractual agreement that the duke had to have his tax claims checked and approved by them. This contract was supplemented in 1510 by provisions on the feudal and inherited, whereby the duke was largely disempowered. Since all tax requests could only be valid after approval by the state authorities, his political activities were severely restricted.

During the reign of John II there was also an attempt to reform the empire . During the Diet of Worms in 1495, this reform was carried out under the Roman-German King Maximilian I , but it was only partially successful due to the resistance of the German territorial princes. One of the positive results was the division of the empire from 1500 into 10 imperial circles . The Duchy of Kleve has belonged to the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Empire since the imperial circles were formed in 1500 .

In the Duchy of Kleve, at the end of the reign of Johann II, the only positive result that remained was the inheritance contract with the Duchy of Jülich-Berg . The dukes of both territories had agreed an inheritance contract because of the lack of a legitimate son in the Duchy of Jülich-Berg. The first step was therefore the engagement of son Johann von Kleve and the Mark in 1496 to the heiress Marie von Jülich-Berg. Since both were minors at the time, the marriage did not take place until 1510.

Duke Johann III. , the peacemaker, became Duke of Jülich and Berg as early as 1511 . After the death of his father in 1521, these duchies were combined with the Duchy of Kleve and the County of Mark to form the United Duchies of Jülich-Kleve-Berg . With this he acquired a secular position of supremacy in the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Empire. The restrictions on government power that Johann II had accepted could largely be lifted by his successor. The focus of his activities now shifted more and more from Kleve to the residence of the United Duchies in Düsseldorf .

Shortly before his death, Johann III. signed an inheritance contract with the Duke of Geldern, Karl von Egmond , in 1537 under pressure from the Geldrian estates . According to this contract, after Karl's death, Geldern and Zutphen should go to the only son of Johann III, Wilhelm von Jülich-Kleve-Berg, as there was no legitimate direct heir for Geldern. Shortly after the conclusion of the treaty and five months before Charles' death in 1538, the future Duke Wilhelm V took over the reign of the Duchy of Geldern.

As Johann III. When Wilhelm V died in 1539, he also took over the reign of “Jülich-Kleve-Berg” and was now one of the most powerful regents in the north-west of the empire. However, in the “Peace Treaty of Grave” in 1536, Egmond had to cede the Duchy of Geldern to Emperor Charles V and only received it as a fiefdom for life. When Egmond died in 1538, Emperor Charles V demanded the Duchy of Geldern as a fief for the Habsburgs . Since Wilhelm V did not want to give up money voluntarily, the Third War of the Geldrian Succession followed . After initial success, Wilhelm V lost the Battle of Sittard at the end of 1543 and had to forego money and Zuphen in favor of Emperor Charles V in the Treaty of Venlo .

When Wilhelm V died in 1592, his son, Duke Johann Wilhelm I of Jülich-Kleve-Berg, succeeded him . In the last phase of his life he was mentally ill and died childless in 1609 despite having married twice. After his death, several princely noble houses, and even for a short time the King of France, raised claims on the lands Jülich, Kleve, Berg, Mark, Ravensberg and Ravenstein that were left behind . Until these claims were clarified, disputes and armed conflicts over the final division of the inheritance followed until the 1660s. Detailed information on this under → “ Jülich-Klevischer Succession Controversy ”.

The Duchy of Kleve as part of Brandenburg-Prussia

Through the Treaty of Xanten in 1614, Kleve came into provisional and in 1666 into permanent possession of the Electors of Brandenburg . From 1609 to 1672, however, the States General held the permanent positions of Kleve with their troops, and it was not until the Great Elector of Brandenburg that Kleve was fully united with the Brandenburg-Prussian state after the special estates were abolished. From 1647 to 1679 Johann Moritz von Nassau-Siegen officiated as governor of the Brandenburg elector in Kleve. After his death, Prince Elector Friedrich temporarily held this office. In 1655 the first university was established in Duisburg. While the Duchy of Kleve still played an important role in the rise of Brandenburg-Prussia in the 17th century, the importance of Kleve and the other western provinces fell steadily in the 18th century, especially after the acquisition of Silesia by Frederick the Great in 1740/42. After Kleve had been under French control from 1757 to 1762 , Prussia remained in the possession of the actual duchy until the Treaty of Basel in 1795, in which it ceded the part on the left bank of the Rhine (about 990 km²) to France . The districts of Zevenaar , Huissen and Malburgen came to the Batavian Republic in 1795 and are now part of the Netherlands . The remaining part of the duchy on the left bank of the Rhine belonged to the Roer department from 1798 to 1814 and returned to Prussia in 1815 due to the agreements made at the Congress of Vienna .

The Klevian areas in the 19th century

In the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss (1803), Prussia was compensated for the loss of its areas on the left bank of the Rhine. In the Treaty of Schönbrunn (1805) Prussia also ceded the part of Kleve on the right bank of the Rhine to France . Napoleon I proposed the city and fortress of Wesel to become the Roer department , and in 1806 he handed over the remaining part together with the Duchy of Berg to his brother-in-law Joachim Murat . In connection with the Confederation of the Rhine established in the same year , the two duchies were combined to form the Grand Duchy of Berg ; as early as 1810, Napoleon separated the northernmost part of the Grand Duchy and connected it with the French department of Oberijssel .

After the collapse of French rule at the end of 1813, the initiative for political action on the entire Lower Rhine was transferred to Prussia , which was awarded essential parts of the Rhineland by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 . Prussia not only won the territories it owned before 1794 ( northern part of the upper quarter of the Duchy of Geldern , Duchy of Kleve and the Principality of Moers ) as well as the areas allocated in the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss ( Reichsabtei Essen , Reichsabbey Werden , Reichsstift Elten and parts of the Duchy of Münster ) back. Rather, it inherited the legacy of all other Rhenish territorial lords by also taking over the formerly Electoral Cologne and Bergisch - Jülich possessions.

In addition to these territorial gains, Prussia also had to accept some territorial losses. All parts of the former upper quarter of the Duchy of Geldern west of the Meuse , a narrow strip east of the Meuse and the exclaves and peripheral areas west and north of Elten ( Huissen , Malburgen , Zevenaar , Lobith and Wehl ) as well as Kekerdom and Leuth south of the Waal were finally incurred the Netherlands . At the same time, Dutch territory passed to Prussia: the Schenkenschanz exclave and the Borghees , Speelberg , Leegmeer and Klein-Netterden districts , which today belong to Emmerich .

The entire area of the former duchy was included in the Prussian administrative structure. It initially belonged to the province of Jülich-Kleve-Berg and the administrative district of Kleve , both of which were dissolved on June 22, 1822 and united with the southern province of Lower Rhine to form the Rhine province and the administrative district of Düsseldorf .

Ruler of Kleve

county

House Kleve (* until 1368)

- about 1020-1050 Rutger I.

- around 1051-1075 Rutger II.

- around 1076-1091 Dietrich (II.)

- 1092-1117 Dietrich I./III.

- 1120–1147 Arnold I.

- 1150-1172 Dietrich II./IV.

- 1173-1193 Dietrich III./V.

- 1189-1200 Arnold II.

- 1202-1260 Dietrich IV./VI.

- 1260-1275 Dietrich V./VII.

- 1275-1305 Dietrich VI./VIII.

- 1305-1310 Otto

- 1310-1347 Dietrich VII./IX.

- 1347-1368 Johann

House Mark (1368-1417)

(Klevian counting method)

Duchy

House Mark (1417–1609)

- 1417–1448 Adolf II.

- 1448–1481 Johann I.

- 1481–1521 Johann II.

- 1521–1539 Johann III. (from 1521 at the same time Duke of Jülich and Berg )

- 1539–1592 Wilhelm

- 1592–1609 Johann Wilhelm

(Klevian counting method)

House of Hohenzollern (1609 / 1666–1918)

Gradual incorporation into the Prussian and later German state , the duchy increasingly loses its function as an independent territory in the Holy Roman Empire. After the last emperor abdicated, the title of Duke of Kleve also lost its meaning for good.

- 1609–1619 Johann Sigismund

- 1619–1640 Georg Wilhelm

- 1640–1688 Friedrich Wilhelm ; resided in Kleve 1646–1649, 1651/52, 1660/61, 1665/66, 1675 and 1686

- 1688–1713 Friedrich I.

- 1713–1740 Friedrich Wilhelm I.

- 1740–1786 Frederick II.

- 1786–1797 Friedrich Wilhelm II.

- 1797–1840 Friedrich Wilhelm III.

- 1840–1861 Friederich Wilhelm IV.

- 1861–1888 Wilhelm I.

- 1888–1888 Friederich III.

- 1888–1918 Wilhelm II.

(Counting of the Hohenzollern follows the Prussian counting method)

Governor of the Electors of Brandenburg in the western provinces of Kleve and Mark

The governor was in charge of the three Klevian authorities, the government college, the official chamber and the court court, and the court offices alongside the government.

- 1604–1609 Stephan VII. Von Hertefeld (1561–1636), Herr auf Kolk (authorized representative)

- 1610–1613 Margrave Ernst of Brandenburg (1583–1613)

- 1613–1618 / 19 Prince Elector Georg Wilhelm of Brandenburg (1595–1640)

- since 1613 Adam Graf von Schwarzenberg (1583–1641), Lord of Gimborn-Neustadt (deputy)

- 1619–1623 / 24 Johann von Kettler († 1624), Freiherr zu Oyen, Montjoie (Monschau) and Amboten

- from around 1625 Gebhard von Eyll († around 1637) to Heideck

- 1643–1647 Johann von Norprath († 1658) (lieutenant general and authorized commissioner)

- 1645 Georg Ehrentreich von Burgsdorff (1603–1656) (representative of the sick commissioner)

- 1647 / 49–1679 Johann Moritz von Nassau-Siegen (1604–1679), since 1652 at the same time master master of the Brandenburg ballot of the Order of St. John

- 1660–1692 Alexander Freiherr von Spaen (1619–1692), Lord of Ringenberg and Moyland (deputy)

- 1681–1688 Prince Elector Friedrich von Brandenburg (1657–1713), later King Friedrich I in Prussia

- 1660–1692 Alexander Freiherr von Spaen (1619–1692), Lord of Ringenberg and Moyland (deputy)

Upper President of the Brandenburg-Prussian government, from 1701 royal government

- 1679–1692 Alexander Freiherr von Spaen (1619–1692), Lord of Ringenberg and Moyland, Drost von Orsoy (Field Marshal General and Governor)

- 1692–1695 Eberhard Christoph Balthasar Freiherr von Danckelman (1643–1722)

- from 1705 Philipp Karl Graf von Wylich and Lottum (1650–1719) (Field Marshal and High President)

- Johann Sigismund von der Heyden (1656-1730)

- 1719–1722 Reinhard von Hymmen (1661–1722)

- 1722–1742 Johann Konrad Freiherr von und zu Strünkede (1670–1742) zu Marnix, Sodingen, Herne and Pöppinghausen

- 1742–1757 Johann Peter (von) Raesfeld (1679–1764)

During the Seven Years' War Kleve was occupied by Austria and France in 1757 / 58–1763.

- 1757–1763 Johann Anton Graf von Pergen (1725–1814) (Austrian administrative president).

In the Peace of Hubertusburg in 1763, the status quo ante was restored.

- 1763 Johann Peter (von) Raesfeld (1679–1764)

- 1763 – after 1780 Adolph Albrecht Freiherr von Danckelman (1736–1807)

- 1784–1790 Emil (Aemilius) Albert Karl Freiherr von Foerder (1754–1790)

- 1790–1803 Otto George Albrecht von Rohr (1736–1815)

Administration and court offices

In addition to the government college (privy council; secret government), official chamber, court court and the war and domain chamber established in 1723 (merged in 1749), there were various court offices in Kleve, which, however, increasingly lost their real influence.

The Erbhofmeisteramt held the family of Wylich to Diersfordt that Erbamt of Erbschenken and land Drosten the family of the Boetzelaer and Erbkämmeramt the family Quadt-Wyckrath-Hüchtenbruck to Gartrop . The office of land marshal was held by members of different families (Steck, von Keppel , Counts von Schauenburg and Holstein , von der Horst , from 1526 inherited from Pallandt zu Zelhem , von Bylandt , then Quadt-Wyckrath-Hüchtenbruck).

The management of the current government administration was incumbent on the chancellor , in Brandenburg-Prussian times the vice-chancellor or director. In 1665 there were 83 members and servants in the three colleges in Kleve, plus 4 pulpit messengers and 22 court attendants, in 1677 41 people were employed at the colleges and 9 as castle staff, plus four court offices.

In 1797 the authority was moved from Kleve to Emmerich am Rhein .

Head of the firm

Chancellor of Kleve-Mark

- 1422 first mention of a law firm

- (1486, 1495) Dietrich von Ryswick

- 1520–1530 Sibert von Rysswich († 1540)

- 1530–1546 / 47 Johann Ghogreff (around 1499–1554); also Chancellor of Jülich-Berg

- 1546 / 47–1575 Heinrich Bars called Olisleger (before 1500–1575)

- 1575–1600 Dr. Heinrich von Weeze (1521–1601)

- around 1600–1609 lic. jur. Hermann ther Lain called Lennep († 1620) (as "Vice Chancellor" entrusted with the duties of the Chancellor)

1609–1614 dispute over succession

- 1658 / 59–1661 Daniel (von) Weimann (1621–1661)

- 1733–1742 Johann Peter von Raesfeld (1679–1764)

Vice Chancellor of the Brandenburg-Prussian government, from 1701 royal government

- 1652–1665 Johann von Diest (1598–1665)

- 1665–1681 Dr. jur. Matthias Romswinkel (1618–1699)

- 1685 – after 1693 Johann de Beyer (around 1630 – after 1693)

- from 1695 Friedrich Wilhelm von Diest (1647–1726)

- 1708–1719 Dr. Reinhard von Hymmen (1661–1722)

- 1720–1732 Johann Freiherr von Motzfeld (1702–1778); The Freiherr von Motzfeld School in Goch - Pfalzdorf was named after him in 1997

- 1733 Johann Peter von Raesfeld (1679–1764)

- 1734–1747 Johann Heinrich Becker (1690–1747)

- 1747–1750 Abraham (von) Koenen (1687–1757), ennobled in 1749

The government in Kleve was united with the court court through the Coccejische judicial reform in 1749.

- 1793–1803 Arnold Wilhelm Elbers (1714–1807), director; 7,200 volumes from his private library were donated to the Bonn University Library in 1829

Sources and literature

literature

- Kurt Schottmüller : The organization of the central administration in Kleve-Mark before the Brandenburg takeover in 1609 . (Diss. Phil. Marburg). ES Mittler, Berlin 1896 ( Google Books ; limited preview); 2nd edition (Staats- und Socialwissenschaftliche Forschungen 14/4 = Heft 63). Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1897 ( digitized version from the Bavarian State Library in Munich).

- Klaus Flink: The Klevian dukes and their cities. 1394 to 1592 . In: Land at the Center of Powers. The duchies of Jülich - Kleve - Berg . Boss, Kleve 1984, ISBN 3-922384-46-3 , pp. 75-98.

- Klaus Flink: Klevische Stadtprivilegien (1241–1609) (= Klever Archive 8). Stadtarchiv Kleve, Kleve 1989, ISBN 3-922412-07-6 .

- Klaus Flink: Territorial formation and residence development in Kleve . In: Klaus Flink, Wilhelm Janssen (Ed.): Territory and Residence on the Lower Rhine. Lectures at the 7th Lower Rhine Conference of the Lower Rhine Municipal Archives Working Group for Regional History (= Klever Archive 14). Stadtarchiv Kleve, Kleve 1993, ISBN 3-922412-13-0 , pp. 67–96.

- Manuel Hagemann: Kleve in crisis. A Lower Rhine county in the 14th century . In: Lectures on the Karl Heinz Tekath Prize 2010 . Historical association for Geldern and the surrounding area, Geldern 2010, ISBN 978-3-921760-47-5 , pp. 47–58.

- Heike Hawicks: Xanten in the late Middle Ages. Abbey and city in the field of tension between Cologne and Kleve (= Rheinisches Archiv 150). Verlag Böhlau, Cologne 2007, ISBN 3-412-02906-8 content (PDF; 53 kB).

- Wilhelm Janssen: The development of the territory of Kleve (= Historical Atlas of the Rhineland Supplement V / 11-12), Bonn 2007, ISBN 978-3-7749-3520-4 .

- Dieter Kastner: The Counts of Kleve and the development of their territory from the 11th to the 14th century . In: Land at the Center of Powers. The duchies of Jülich - Kleve - Berg . Boss, Kleve 1984, ISBN 3-922384-46-3 , pp. 53-62.

- Dieter Kastner: The territorial policy of the Counts of Kleve (= publications of the historical association for the Lower Rhine, in particular the old Archdiocese of Cologne 11). Schwann, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-508-00161-X .

- Thomas R. Kraus: Studies on the early history of the Counts of Kleve and the emergence of the Klevian rule . In: RhVjbll . 46.1982. Pp. 1-47.

- Jens Lieven: nobility, rule and memory. Studies on the culture of remembrance of the Counts of Kleve and Geldern in the High Middle Ages (1020 to 1250) (= writings of the Heresbach Foundation Kalkar 15), Bielefeld 2008, ISBN 978-3-89534-695-8 .

- Wolf-Rüdiger Schleidgen: Territorialization through administration. Notes on the history of the Duchy of Kleve-Mark in the 15th century . In: RhVjbll . 63.1999. Pp. 152-186.

- Review of the history of the Duchy of Cleve in general, and of the city of Wesel in particular: during the Cleve succession dispute, from 1609 to 1666 . Bagel, Wesel 1830 ( digitized ).

Source publications

- Theodor Ilgen: Sources for the internal history of the Rhenish territories. Duchy of Kleve 1: Offices and Courts , 2 volumes in 3 parts, Bonn 1921-25 (publications by the Society for Rhenish History 38).

- Heike Preuss (arr.): Kleve-Mark documents 1394–1416. Regesta of the holdings of Kleve-Mark documents in the North Rhine-Westphalian main state archive in Düsseldorf , Siegburg 2003 (publications of the state archives of North Rhine-Westphalia C 48).

- Wolf-Rüdiger Schleidgen (arrangement): The copy of the Counts of Kleve , Kleve 1986 (Klever Archive 6).

- Wolf-Rüdiger Schleidgen: Kleve-Mark documents 1223–1368. Regesta of the holdings of Kleve-Mark documents in the North Rhine-Westphalian main state archive in Düsseldorf , Siegburg 1983 (publications of the state archives of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia C 13).

- Wolf-Rüdiger Schleidgen: Kleve-Mark documents 1368–1394. Regesta of the holdings of Kleve-Mark documents in the North Rhine-Westphalian main state archive in Düsseldorf , Siegburg 1986 (publications of the state archives of North Rhine-Westphalia C 23).

- Robert Scholten (Ed.): Clevische Chronik after the original manuscript of Gert van der Schuren with prehistory and additions by Turck, a genealogy of the Clevischen Haus and three writing tablets , Kleve 1884.

archive

The Kleve-Märkische Landesarchiv is now in the main state archive in Düsseldorf .

Web links

- Kleve . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 9, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, p. 841.

- Edicts of the Duchy of Kleve and the County of Mark (Scotti Collection) (1418–1816) online

- "Clef" coat of arms in the Book of Arms of the Holy Roman Empire , Nuremberg around 1554–1568

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Gerhard Köbler : Historical Lexicon of the German Lands. The German territories and imperial immediate families from the Middle Ages to the present. 5th, completely revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39858-8 , pp. 307-308.

- ↑ Otto Titan von Hefner, in: Stammbuch des blooming and dead nobility in Germany , 1860, 1st volume A to F, p. [250] 446. Online version

- ^ Gert van der Scheuren, in: Clevische Chronik , 1884, Cleve, Ed. Robert Scholten, p. [84] 42. Online version

- ^ Gert van der Scheuren, in: Clevische Chronik , 1884, Cleve, Ed. Robert Scholten, p. [93] 51. Online version

- ↑ a b Gert van der Scheuren, in: Clevische Chronik , 1884, Cleve, Ed. Robert Scholten, p. [228] 186. Online version

- ^ Gert van der Scheuren, in: Clevische Chronik , 1884, Cleve, Ed. Robert Scholten, p. [238] 196. Online version

- ^ Friedrich Everhard von Mering, Ernst Weyden, in: History of the castles, manors, abbeys and monasteries in the Rhineland , 1833, Cologne, p. [119] 113. Online version

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of the original from May 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Rhineland History Regional Association of the Rhineland

- ↑ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine or the Archbishopric of Cöln, document 192 , 1853, part 3, 1301–1400, p. [185] 165. Online version

- ↑ According to the notes on the sales deed in the cited document book from 1853, p. [185] 165.

- ^ NDB, Wilhelm Janssen, in: Johann von Kleve , 1974, Volume 10, p. 491/2. Online version [1]

- ↑ a b NDB, Helmut Dahm, in: Adolf III. von der Mark , 1953, Volume 1, pp. 80/1. Online version

- ^ Wilhelm Janssen, in: History of Geldern bis zum Traktat von Venlo (1543) , 2001, edited by Johannes Stinner and Karl-Heinz Tekath, part 1, p. 23

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine or the Archbishopric of Cöln, document 737 , 1853, part 3, 1301–1400, p. [645] 633.

- ↑ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine and the Archbishopric of Cöln, preliminary remarks , Volume 3, p. [12] XII. Digitized edition of the ULB Bonn

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine and the Archbishopric of Cöln, document 968 , 1853, volume 3, p. [863] 851.

- ^ NDB, Henny Grüneisen, in: Adolf I. Herzog von Kleve , 1953, Volume 1, pp. 81/2. Online version

- ↑ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine and the Archbishopric of Cöln, document 102 , 1858, part 4, p. [138] 112. Online edition 2009 [2]

- ↑ a b c NDB / Henny Grüneisen, in: Graf Adolf II. , 1953, vol. 1, p. 81/2. Online version [URL: http://www.deutsche-biographie.de/ppn133534138.html ]

- ↑ Robert Scholten; in: On the history of the city of Kleve , 1905 Cleve, p. [534/535] 508/509. Online version

- ^ NDB / Manfred Groten, in: Ruprecht von der Pfalz , 2005, Vol. 22, pp. 286/7. Online version [URL: http://www.deutsche-biographie.de/ppn12388957X.html ]

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine or the Archbishopric of Cöln. Document 369. 1858, part 4, 1401-1609, p. [488] 462. Online version

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine or the Archbishopric of Cöln. Certificate 3701858. Part 4, 1401-1609, p. [496] 464. Online version

- ^ NDB / Wilhelm Janssen, in: Herzog Johann I. , 1974, vol. 10, p. 492. Online version [URL: http://www.deutsche-biographie.de/ppn132254948.html ]

- ↑ Theod. Jos. Lacomblet, Woldemar Harleß: Archive for the history of the Lower Rhine . In: The new episode, second volume / III. The Cleve-Märkischen state stands… . 1870, Cöln, p. [183] 179. Online version

- ↑ a b NDB / Wilhelm Janssen, in: Herzog Johann II. , 1974, Vol. 10, p. 493. Online version [URL: http://www.deutsche-biographie.de/ppn119135574.html ]

- ↑ Theod. Jos. Lacomblet, Waldemar Harleß: Archive for the history of the Lower Rhine . In: The new episode, second volume / III. The Cleve-Märkischen state stands… . 1870, Cöln, p. [184] 180. Online version

- ↑ a b ADB / PL Müller, in: Karl von Geldern , 1882, Vol. 15, pp. 248 to 292. Online version [URL: http://www.deutsche-biographie.de/ppn104206527.html?anchor=adb ]

- ↑ a b c d e Cf. Bert Thissen: The governor and the residence - Johann Moritz von Nassau-Siegen and the city of Kleve . In: Irmgard Hantsche (ed.): Johann Moritz Von Nassau-Siegen (1604–1679) as a mediator. Waxmann, Münster 2005, pp. 107-130, especially pp. 110, 116.

- ^ On behalf of the Elector of Brandenburg, he took possession of the duchies in Kleve on April 4, 1609 in Düsseldorf ; see. Ernst von Schaumburg : The establishment of the Brandenburg-Prussian rule on the Lower Rhine and in Westphalia or the Jülich-Clevian succession dispute. A. Bagel, Wesel 1859, pp. 100-103.

- ↑ a b cf. Stephanie Marra : B.7_Kleve_und_Mark . In: Courtyards and residences in the late medieval empire. A dynastic topographical handbook (Residency Research 15/1). Jan Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2003, pp. 820–826 (online resource, accessed February 1, 2013).

- ^ A b c cf. Daniel Legutke: Diplomacy as a social institution. Brandenburg, Saxon and Imperial ambassadors in The Hague 1648–1720 (Netherlands Studies 50), Waxmann, Münster 2010, passim .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Rolf Straubel : Biographical manual of the Prussian administrative and judicial officials 1740–1806 / 15 . In: Historical Commission to Berlin (Ed.): Individual publications . 85. KG Saur Verlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-598-23229-9 .

- ↑ Cf. Elisabeth Knecht: The administrative organization in the territory of Kleve and its reforms under the Count and later Duke Adolf (1394–1448) , Diss. Cologne 1958.

- ^ Cf. Woldemar Harleß: Olisleger, Heinrich Bars . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 24, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1887, pp. 303-305.

- ↑ See Kurt Schottmüller: The organization of the Central Administration in Kleve-Mark before the Brandenburg takeover in 1609 . (Diss. Phil. Marburg). ES Mittler, Berlin 1896, p. 53.

- ↑ See Ferdinand Hirsch: Weimann, Daniel . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 41, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1896, pp. 494-500.

- ↑ See Hans Saring: de Beyer, Johann. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 2, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1955, ISBN 3-428-00183-4 , p. 205 ( digitized version ).

Remarks

- ↑ The historian JF Knapp gives in his book "Regents and People's History of the Countries Cleve, Mark, Jülich, Berg and Ravensberg" from 1831, Volume 1 for the Counts of Cleve a complete list from 827 on, which inevitably from the before 1041 The information here differs completely and only shows some matches from around 1200. In the introduction to the history of the County of Kleve, however, a Theodoric von Teisterbant-Cleve for the reign of Karl Martell around 725 is cited as the first or second count.

- ↑ Chronicles that were created in the Middle Ages were often manipulated in order to make a noble family older or to increase their importance. In addition, oral sources often had to be used due to the lack of documents. The chronicle from the 14th century was revised by "von Turck" and "Robert Scholten" in 1884 and supplemented with many reliable documents.

- ↑ Regarding Arnold II, the dates of the reign in both chronicles differ particularly strongly. In the older one this ends in 1150 while in the newer one it does not begin until 1189. However, since 1147 is given as the year of death for Arnold II in the "NDB", the newer for the period between around 1130 and 1200 is likely to be incorrect.

- ↑ The different counting methods for the counts, for example Dietrich III./V., Result from the non-identical sources. The way of counting with “III.” Refers to the root list and also corresponds to the opinion of some of the current historians. In contrast, “V.” corresponds to the counting method of the older chronicle. Inevitably, there are clear differences with regard to the names of the first counts as well as for the term of office because of the poor sources. Only from Count Dietrich V./VII., Reign from 1260 to 1275, are both chronicles identical, even if the different counting methods remain unchanged.