Veliky Novgorod

| city

Veliky Novgorod

Великий Новгород

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| List of cities in Russia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Veliky Novgorod ( Russian Вели́кий Но́вгород ), until 1999 Novgorod , is a large city in Russia with 218,717 inhabitants (as of October 14, 2010). It is located about 164 km south-southeast of Saint Petersburg on the Volkhov north of Lake Ilmen and is the administrative center of Novgorod Oblast in the federal district of northwestern Russia .

Until 1999 the city was officially called Novgorod , also written Novgorod ( Russian : Новгород ). Veliky Novgorod literally means Great Novgorod ("large" in the sense of "significant"). Earlier names (as exonyms ) were German Navgard, Naugard, Neugarten, Neugard and Old Norse Hólmgarðr .

As one of the oldest cities in Russia, Veliky Novgorod celebrated its 1150th anniversary in September 2009. In the 9th century Novgorod was the first capital of the young Kievan Rus . From the 12th to 15th centuries, Novgorod was the capital of the influential, trade-oriented Novgorod Republic and an important mediator between the Rus and the West before it became part of the centralized Russian Empire . Novgorod's architectural heritage has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1992 . According to a survey from 2010, Veliky Novgorod is one of the most livable cities in Russia.

geography

Geographical location

Novgorod is located in the northwest of the European part of Russia, 164 kilometers from Saint Petersburg and 494 kilometers from Moscow . The Volkhov River cuts through the city from south to north . It is an average of 25 m high. The urban area has an area of 90 square kilometers. About 60 percent of the surrounding area is forested, mostly with elms . The south of Novgorod, near Lake Ilmen, is very rich in marshland. Overall, Veliky Novgorod is surrounded by extensive swamp and forest areas, in which peat in particular is extracted .

The geographical location is favorable for traffic, as the Lowat , Schelon , Msta and Volkhov rivers , which flow into the lake, offer ideal transport routes. The Volkhov flows into Lake Ladoga , from which one reaches the Baltic Sea through Saint Petersburg . There is a connection to the Black Sea via the rivers in the south of Novgorod .

geology

The city lies in the Eastern European Plain and in the easternmost part of the Baltic Ridge . Geologically, the city lies on the Russian table , which consists mostly of unfolded Young Proterozoic to Cenozoic sediments , which here cover large areas of the ancient continent Fennosarmatia . Unlike its surrounding mountains, the Russian table is poor in natural resources despite its size. During the last ice ages , the Scandinavian glaciers reached into the Novgorod region. The shallow Ilmensee (only 2.5 to 10 meters deep) is the remainder of a glacial melt lake in which fluvial and periglacial sediments are widespread.

City structure

The city is roughly divided into the historic city center and the new town, which was laid out outside the former city walls. The old town is divided into the Sophienseite, named after the Sophienkathedrale, on the western bank of the Volkhov and the trading side on the eastern bank. The Sophienseite consists of three fifths of the city, in the north the Nerewski fifth, in the west the Sagorodski fifth and in the south the Lyudin fifth, the former potter fifth. The trade side consists of the Plotniki fifth, the former carpenter 's fifth, in the north, and the Slavno fifth in the south. These districts are called konzy (literally "ends", singular konez ) in Russian , which is specific to Novgorod.

In the eastern center on the Sophia side is the Novgorod Kremlin . The sides have been connected by a large wooden bridge since the 11th century; it was sporadically destroyed by fire, flood or ice. In the western center of the trading side were the medieval market square, the Jaroslaw-Hof and the offices of foreign traders, especially the Hanseatic Peterhof . The new town is much more developed on the western side of the river than on the eastern side. The districts of Koltowo, Grigorowo, Sapadiny, Nowaja Melnitsa, Leschno, Pankowka and Bely Gorod join the Sophienseite from north to south, and the Antonowo district on the trading side in the north.

Neighboring communities

Seven other Rajons border the Stadtrajon Novgorod within the Novgorod Oblast . Clockwise from north to west, these are: Chudovo Raion, Malaya Vischera, Krestzy , Parfino , Staraya Russa, Shimsk and Batetsky. In the northwest, the Rajon borders on the Pskov Oblast .

climate

With its humid climate, Novgorod is located in the cool temperate climate zone influenced by the continental climate . In the climate classification it is classified as DfB, that is, (D) the coldest month has a temperature of less than −3 ° C, the warmest month is over 10 ° C, (f) all months are humid and (B) the The temperature is below 22 ° C, but there are at least four months that are warmer than 10 ° C. The average annual temperature in the city is 4.3 ° C. Although the annual precipitation is only 561 millimeters (for comparison Cologne : 798 millimeters), it is higher than the evaporation, which is why a humid climate prevails. The warmest months are June and July with an average of 15.7 and 17.3 ° C, the coldest months are January and February with an average of −9.2 and −8.2 ° C. Most of the precipitation falls in the months of July and August with an average of 72 millimeters each, the lowest in February with an average of 23 millimeters.

| Veliky Novgorod | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Average monthly temperatures and rainfall for Veliky Novgorod

Source: Roshydromet

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

history

Prehistory and early history

The surroundings of Novgorod are characterized by many forests, lakes, swamps and marshland , which made the area almost impenetrable and the rivers to the most important transport routes. The only areas suitable for settlement lay along the banks of the rivers and lakes.

In Rurikowo Gorodishche near Novgorod there was a Neolithic settlement since the 3rd millennium BC. The first settlers in the area around and north of Lake Ilmen were Finno-Ugric hunters and fishermen. The newcomers introduced agriculture . Since the 8th or early 9th century, Slavic Ilmen Lake Slovenians also settled there.

Novgorod Rus

Scandinavian Varangians drove through this area on the trade routes to the Byzantine Empire since the 8th century. In the middle of the 9th century, one of their settlements, today's Rurikowo Gorodishche , arose on the eastern bank of the Volkhov at the exit of Lake Ilmen, two kilometers south of today's Novgorod . This settlement initially developed into the region's central trading center.

The settlement was first mentioned in ancient Russian chronicles in 862. The Varangian prince Rjurik established the center of his rule here.

Novgorod in the Kiev Rus

Around 911, Kiev became the new center of Russia. Old Novgorod lost this role. Around 969, Vladimir I became the first separate prince of Novgorod. In 988/989 Novgorod became the seat of the second eparchy (diocese) of the Rus. The first bishop was Joachim Korsunianin .

Around this time, today's Novgorod ( New Town ) emerged as a merchant settlement some distance from the old Rurikowo Gorodishche castle. The wooden Sophienkirche and the Joachim-und-Anna-Kirche were probably the first to be built .

Yaroslav the Wise had been Prince of Novgorod since around 988. In 1015, after the death of his father Vladimir I, he sought control of Kiev. Since the Novgorodians supported him in this successful enterprise, he gave them extensive rights, which formed the basis for the future boyar order in Novgorod. These privileges led to a structural division of the city. The boyar courts were no longer under the jurisdiction of the prince and formed the basis for the five districts ( конец , end ). Freelance artists and traders settled between these quarters, who continued to be under the prince's jurisdiction. These areas were divided into hundreds ( sotni ) and administered by so-called "thousands leaders " ( tysjazkie ) and "hundreds leaders " ( sotskie ).

During a visit in 1030 Yaroslav ordered that 300 children of the elders and priests should be instructed in reading.

Around 1030, the seat of the prince of Gorodishche was probably moved to the Novgorod Kremlin.

The social structure consisted of three layers: wealthy merchants and bankers (also landowners) were at the top; ordinary merchants represented the middle class; Craftsmen and day laborers belonged to the lower class of the population.

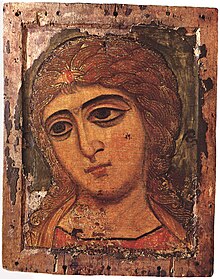

In addition to trade, culture also flourished. Famous icon painters such as Theophanes the Greek and Andrei Rublev worked in the city. In 1056/1057 the Ostromir Gospel was made for the Novgorod governor Ostromir.

In the High Middle Ages, Novgorod was the only city in Europe, alongside Constantinople , where not only the nobility and clergy, but also the common people could read and write. This is evidenced by the more than 1000 letters found during archaeological excavations and written on birch bark in an Altnowgorod dialect (so-called birch bark certificates ). These report on everyday life in the medieval city. On July 26, 1951, the first fragments of birch bark were discovered during excavations by Nina Akulova in Velikaya Street. More than a thousand birch bark fragments are now known.

The ties of the Norwegian rulers to the city can also be seen in the fact that they used Novgorod as a refuge on several occasions. So before 1000 Olav I. Tryggvason fled there, from 1027 to 1030 Olav II. Haraldsson . His son Magnus I was educated in Novgorod until 1035 and brought back by Norwegian nobles after his father's murder. Harald III, too . sought refuge in Novgorod when danger threatened. Olav I. Tryggvason and Magnus I. spent their childhood and youth here and had a close relationship with the city throughout their lives.

Novgorod Republic from 1136 to 1478

In 1136 a general uprising against the prince ended with a victory for the boyars. As a result, the prince was only an official of the boyar republic. He could only exercise his function as judge if his judgment was confirmed by the Possadnik , the head of the boyar council, who increasingly directed foreign policy and spoke law, led the army and occupied the offices and thus assumed the role of prince. As a direct result of the uprising, Prince Vsevolod II was expelled and Svyatoslaw Olegowitsch from Chernigov was installed. The second important office was held by the Tysjackiy, the leader of the thousand, who led the popular riot and was responsible for taxes, levies and the market. The bishopric that was established in 1035 rose to become an archbishopric in 1165.

Spared from the devastation of the Mongol raids, Novgorod was at times, especially under Alexander Nevsky , the center of the Russian principalities and the seat of the Grand Duke . Starting with Alexander Nevsky, the Novgorod princes were elected from among the princes of Vladimir-Suzdal . The city became one of the largest city-states and developed a territory of around 30,000 km², another 1.5 million km² to the Urals were in a tributary relationship. In the 14th century the older part of the name Veliki began to be interpreted as large in order to separate Greater Novgorod from other cities. In the 14th century, the urban area covered around 400 hectares, the city castle alone (detinec) 11 hectares. The population rose from around 50–60,000 in the 13th century to up to 80,000 in the 15th century. Their population thus exceeded the size of the most important German cities such as Cologne , Nuremberg or Lübeck .

The expansion of power based on this development made it possible for the city to militarily fend off the expansion of the Swedes in 1240 and that of the Teutonic Order in 1242 . In total, Novgorod went to war 26 times against Sweden and 11 times against the Livonian Brotherhood of the Sword . The defense in 1240 and 1242 succeeded, although Novgorod's German opponents, taking advantage of the Mongol invasion of Russia, together with Danes and Swedes, shifted their military operations to the Novgorod area. However, their campaigns failed in the Battle of the Neva and the Battle of Lake Peipus . On August 12, 1323, the Treaty of Nöteborg between Sweden and Novgorod was signed, which for the first time regulated the border between the Russian and Swedish parts of Finland.

In the late Middle Ages , Novgorod was a city dominated by the noble merchant class, who were mainly recruited from the large landowners and profited to a large extent from the collection of tributes. They were joined by a layer of full-time long-distance traders who were mainly active in Western trade. A counterbalance was formed by a veche - a people's assembly going back to Old Slavic traditions - in which non-aristocratic population groups were also entitled to speak and vote. The oligarchical city republic , which elected the prince since the 12th century, the archbishop from 1156 and the possadniks, a kind of mayor of the city, had good contacts with the Hanseatic League , which had one of its four offices there in the Peterhof .

In the 14th century Novgorod had finally risen to become the main trading intermediary with the West. Since the transit trade of the Russian countries and also of the Tatars , who traded in spices and furs, with Western Europe via Lithuanian territory was impaired by high tariffs and frequent attacks, this position remained unchallenged in the following period.

Trade with Gotlanders and Hanseatic League

Contacts of foreign traders with Novgorod are documented as early as the 10th century. For example, Ravnur Hólmgarðsfari from the Norwegian Tønsberg, mentioned in the Faroese saga, already has the Nordic name for Novgorod in its name, which means Novgorod driver.

After Lübeck was founded , the Hanseatic merchants began to travel across the Baltic Sea to Gotland in the middle of the 12th century . The first contacts to Novgorod were arranged through the local merchants. The Gotland merchants maintained the so-called Gotenhof on the trading side , and the Hanseatic merchants initially participated in its use. There was also a Gotland guild yard. In 1192 the Hanseatic League established its own courtyard, the so-called Peterhof . The name of the office goes back to the St. Peter church built in it. In addition to residential buildings, the courtyard also contained economic facilities such as a bakery, brewery, hospital, bath and prison. The Hanseatic merchants had their own legal sovereignty on the farm, but also had to take legal measures themselves. However, after the Novgorod Schra , the merchants did not have the right to stay in Novgorod permanently. According to the seasons, a distinction was made between winter and summer drivers. The traders mainly transported raw products to Western Europe, in particular furs , wax , honey and wood . In return, they mainly brought finished products to Novgorod such as wine, beer, cloth, weapons and glass, but also salt, herring, metal (silver), spices, tropical fruits, horses and amber. When a great famine broke out in Volkhov in 1230 , they mainly transported grain. With the decline of the Gotland Olafshof in the 14th century, which was subsequently leased by the Hanseatic League, the Hansa gained a monopoly in trade with Novgorod. The type of ship, the cog , also contributed to strengthening this monopoly. The import of glass products such as finger rings and window glass can be archaeologically documented between 1396 and 1462. In the 15th century trade slowly declined, as the exchange of goods was increasingly shifted to the Livonian cities. The Peterhof in Novgorod was after the conquest of the city by the Moscow Grand Duke Ivan III. 1478 not closed. On the contrary, the privileges of the Hanseatic League were confirmed again in 1487. In the course of his disputes with Maximilian von Habsburg, Ivan III. but close the farm on November 6, 1494. The confiscation brought the Grand Duke 96,000 marks. In 1514 the Gotenhof and the Peterhof were reopened and the courtyards seem to have been in use until 1560. In the 17th century, the Schwedenhof was built on Slavnaya Street northeast of the old square.

Coinage and long-distance trade

The city of Novgorod was the starting point for the development of coinage in Russia due to its strong trade relations with foreign merchants. From the second half of the 13th century it became common to use silver bars as a unit of currency. The weight of these bars was 205 grams, corresponding to the old Russian weight unit, the hryvnia . In smaller trading transactions, smaller pieces of silver, so-called rubles , were separated from the larger bars . In the 13./14. In the 19th century, coins were first minted in northwestern Russia, initially in Novgorod and Pskov , and later in Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod and Suzdal .

When the circulation of money increased at the beginning of the 15th century and all grand dukes began to mint money, Novgorod started minting its own coins from 1420 onwards. Novgorod had previously adopted the Livonian currency for a short time .

From the 10th to the 13th century came from the Byzantine Empire , especially amphorae , glass products, shoot distant whorls and walnuts in the city. From the Dnieper also were -region ambers that are waiting there in geological layers imported. Around 1100 the import experienced a brief interruption, which can be explained by a conflict between the cities of Kiev and Volkhov. With the destruction of Kiev in 1240 by the Mongols of the Dnieper-way lost most its meaning, while on the Volga pathway, the import of boxwood for comb production continued was. In the 14th century in particular, glazed pottery from the Tatar chanate of the Golden Horde reached Novgorod via this route .

Moscow period from 15th to 19th centuries

For a long time Novgorod was in competition with the Grand Duchy of Moscow , with Novgorod representing the oligarchic- urban aristocratic social order, Moscow the autocratic- princely. In addition to this contrast came the fight against the Novgorod river piracy ( Uschkuiniki ), which prompted Moscow to unleash an uprising against the rule of Novgorod as early as 1397. The steady increase in power in Moscow increasingly threatened the rocking policy, which Novgorod had successfully practiced for a long time between Moscow, Tver and Lithuania , as Tver lost more and more importance and the forces of Lithuania after the union with Poland through clashes in Bohemia, Hungary and with the Teutonic Order were bound. Novgorod also failed to break away from the sovereignty of the Moscow Metropolitan. In 1441, the city made tribute payments to Moscow for the first time.

After a successful attack, Moscow was able to increase its influence on Novgorod's foreign and domestic policy after 1456. The Wetsche was no longer allowed to issue documents in its own name. After this defeat, the Novgorod boyar oligarchy had to recognize in 1458 that Moscow had in the meantime gained a clear preponderance. After the Novgorod defeat in the Battle of the Schelon (1471) and renewed anti-Moscow tendencies, it was finally incorporated into the Grand Duchy in 1478, with Moscow pretending to prevent a church schism in Russia in favor of the Lithuanian Catholics. Numerous Novgorod boyars, their clientele and merchants were relocated to Moscow, where a Novgorod district was built near the Kremlin. In return, Moscow servants took over the property of the dispossessed. The abolition of the Veche Bell symbolized the end of the Novgorod city-state.

During the Livonian War , the city was destroyed in 1570 by the troops of Tsar Ivan the Terrible , after he suspected that the citizens of Novgorod were trying to ally themselves with Poland-Lithuania . On January 15, 1582, the Jam Zapolski Treaty (Armistice) was signed in the village of Jam Zapolski near Novgorod between Poland-Lithuania and Russia. During the turmoil in the Polish-Russian War 1609-1618, Novgorod was occupied and destroyed by the Swedes between 1611 and 1617. The wars and events mentioned led to Novgorod's population dropping to 8,000, and its political and economic importance declined to the same extent.

The city flourished thereafter, but after Saint Petersburg was founded in 1703, its economic and strategic importance as Russia's northwest outpost declined. The urban structure underwent a serious change after 1778, when the new general development plan drawn up by Nikolai Tschitscherin ( Николаи Чичерин ) was signed by Empress Catherine II . While the semicircular city wall on the Sophienseite was preserved, the plan provided otherwise right-angled streets. The road structures that had grown over the centuries were destroyed for this.

In 1859, the design by Mikhail Ossipowitsch Mikeschin (1835–1896) won the competition for the Novgorod Monument Thousand Years of Russia, which was followed with great interest by the public .

Soviet Union, World War II

In the Soviet Union, Novgorod belonged to the Leningrad Region, which included the Murmansk , Pskov and Cherepovets districts or districts . Although the Novgorodians had joined the Council (Soviet) movement in Russia at the end of 1918, they were more inclined towards the moderate socialist parties.

In the German-Soviet War (1941-1945) Novgorod was under German occupation from August 15, 1941 to January 20, 1944 and suffered great damage as a result. Among other things, Bolko von Richthofen destroyed the library of the Novgorod Antiquities Society and the museum in Staraya Russa on behalf of the Foreign Office during the Russian campaign . At the request of the Wehrmacht on October 4, 1941, Heinrich Himmler ordered the Lange Sonderkommando to be brought to Novgorod by plane to kill the inmates of three institutions for psychiatric patients. The premises were needed to accommodate troops. After the liberation in the course of the Leningrad-Novgorod operation , the reconstruction of the city began at the beginning of 1944. Novgorod Oblast was established on July 5, 1944.

Recent history

In 1999 the city got its historical name Veliky Novgorod back. On July 13, 2000 the so-called Novgorod Codex was discovered during excavations , a wax tablet book from the first quarter of the 11th century, which consists of three bound limewood panels with a total of four pages filled with wax. In September 2004, Veliky Novgorod hosted the first meeting of the Valdai Club , an annual round table of experts on Russian foreign and domestic policy. Vladimir Putin was also a participant . On October 28, 2008 Veliky Novgorod received the award "Glorious Battle City" from President Dmitry Medvedev for "courage, perseverance and mass heroism in defending the city in the struggle for freedom and independence of the fatherland". In 2009, the city celebrated the 1150th anniversary of the first written mention. From June 18 to 21, 2009 the XXIX. International Hanseatic Days of the New Age .

Population development and structure

The population of Veliky Novgorod in 2010 was 218,717, making the city 86th among the largest cities in Russia. Novgorod reached the highest population in its history with over 229,116 inhabitants in the early 1990s, and in the following years the number fell significantly, as was the case in most cities in Russia during the economic crises of the 1990s. The following table shows the development of the population of the city of Novgorod since about 1825. From 1959 to 1979 the population more than tripled. In contrast, a significant decline in population was recorded in the years of the Second World War.

|

|

|

|

|

Religions

Christianity

The vast majority of the population, 93.9 percent Russians, 1.5 percent Ukrainians and 4.9 percent from other nationalities, belongs to Russian Orthodox Christianity. The city forms its own eparchy of the Russian Orthodox Church under the direction of Archbishop Lev Zerpizkij. Until 1165 the city was the seat of a bishop, but since then an archbishop. In addition, there is a separate head of the monasteries, the Archimandriten , who resides in the Jurjew monastery.

The Philip and Nicholas Church was reconstructed in the 1970s.

Atheism was officially enacted for over 70 years . The current information on religion fluctuates. According to statistics from Interfax in 2010 with 1,600 respondents, 75 percent of Russians in the whole of Russia are Orthodox, 5 percent Muslim and one percent or less each are Protestant, Buddhist, Catholic or Jewish.

In the 15th and 16th centuries a group of " Judaizers " formed as a sect in the Russian Orthodox Church . Although they did not convert to Judaism , they had a keen interest in the Old Testament and the Hebrew Letters. The sect was a mixture of late medieval Kabbalism and early Neoplatonic humanism .

Judaism

In 1990 the Novgorod Jewish Cultural Society was founded under the leadership of Grigory Fainberg, Tamara Khorewa and Lyubov Tintarewa. Until 1990 there was no Jewish religious practice in the city, only Hebrew lessons that Arkadi Freikman gave before he emigrated to Israel in 1990 . In May 1993 the community was officially approved. Since 2000 she has been a full member of the Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia (Russian Федерация еврейских общин России , ФЕОР ). The spiritual leader of the church has been Rabbi Gershon Paley from Saint Petersburg since 2002. In 2003 the community organized its first Jewish cultural festival. The community consists of about 1500 people.

politics

administration

Veliky Novgorod is the administrative seat of Novgorod Oblast . The Veliky Novgorod city administration consists of the mayor's office, whose head is the mayor , the head of the city, and the municipal authority ( муниципалитет ), whose members are determined in the course of local elections. The city council, the Novgorod Duma, consists of 30 members.

mayor

Yuri Ivanovich Bobryschew has been the mayor of Veliky Novgorod since March 11, 2008. In 2013 Bobryshev was re-elected for a second term.

The following are the mayors ( мэр ) since 1994:

| Start of office | End of office | Name and dates of life | German transcription |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | September 9, 2002 |

Александр Владимирович Корсунов * February 18, 1951, † September 9, 2002 |

Alexander Vladimirovich Korsunov |

| September 9, 2002 | December 20, 2002 |

Сергей Николаевич Лобач * November 6, 1964 (managing mayor) |

Sergei Nikolayevich Lobach |

| December 20, 2002 | December 11, 2007 |

Николай Иванович Гражданкин * August 23, 1948 |

Nikolai Ivanovich Graschdankin |

| March 11, 2008 |

Юрий Иванович Бобрышев * May 3, 1951 |

Yuri Ivanovich Bobryschew |

heraldry

Novgorod has two of its own heraldic symbols with a city coat of arms and a city flag. Both have the motifs of the bear and the archbishop's throne in common. The first coat of arms of Novgorod was made an official city symbol on August 16, 1781. It was approved on September 12, 1991 in a modified version.

Blazon : In silver, two profiled black bears left and right of a golden archbishop's throne, on top of which a red pillow and, crossed over it, two golden lecture crosses and a three-armed golden candlestick with red burning silver candles.

In the older version from 1781, the archbishop's throne and the two bears stood over a blue water surface in which four silver fish, two on top of each other, were facing towards the center.

The city flag of Veliky Novgorod was horizontally striped white, blue and white with the city coat of arms in the middle. This flag was officially approved on April 14, 1994. It was changed on April 29, 2008 and since then has only been white with the coat of arms in the middle.

Town twinning

Veliky Novgorod is a member of the New Hanseatic League of Cities . Veliky Novgorod has twinned cities with seven locations:

-

Uusikaupunki , Finland (since 1965)

Uusikaupunki , Finland (since 1965) -

Moss , Norway (since 1970)

Moss , Norway (since 1970) -

Nanterre , France (since 1974)

Nanterre , France (since 1974) -

Watford , United Kingdom (since 1984)

Watford , United Kingdom (since 1984) -

Bielefeld , Germany (since 1987)

Bielefeld , Germany (since 1987) -

Rochester , USA (since 1990)

Rochester , USA (since 1990) -

Zibo , People's Republic of China (since 1995)

Zibo , People's Republic of China (since 1995)

The city also maintains administrative partnerships with three cities, in particular close cooperation in the cultural field:

-

Strasbourg , France (since 1997)

Strasbourg , France (since 1997) -

Polatsk , Belarus

Polatsk , Belarus -

Kohtla-Järve , Estonia

Kohtla-Järve , Estonia

As a result of a decision by the Bundestag on military retrofitting, Bielefeld contacted Veliky Novgorod in the winter of 1983/84. From the initial contact by letter, a town twinning developed by 1987. In the 1990s, the people of Bielefeld undertook many aid transports to the Russian twin city, and social projects in Veliky Novgorod are still financially supported today.

Culture and sights

Museums

The "State Unified Museum Complex" was founded on May 4, 1865 by Nikolai Gavrilowitsch Bogoslowski and in 1992 included in the list of world cultural heritage. It includes exhibitions, exhibition halls, monuments and museums in Novgorod and the Novgorod region. The following exhibitions in Novgorod are currently mainly shown in the old administration buildings of the Kremlin. The exhibition The History of Novgorod and Novgorod Country from Ancient Times to the Present Day exhibits work tools, household items, armor and fragments of birch bark, as well as the oldest Russian musical instruments, chess pieces and children's toys.

The exhibition Russian icons of the 11th to 19th centuries in the collection of the Novgorod Museum shows 268 icons in chronological order in 14 halls . Special features are on the one hand the oldest Russian icon "Peter and Paul" from the 11th century and on the other hand "Saint Nikolai" from 1294 by the master Alexei Petrow. In the exhibition The Old Russian Carved Wood , the various carved everyday objects, pieces of furniture and sledges and structures of the houses are shown. One of the oldest monuments of Russian wooden sculpture is the Ludogoshensky Cross , donated in 1359 by residents of Lyudogoschtscha Street. Further exhibitions are located in the Bishop's Palace and in the Johannes Building . In the latter, a collection of old Russian ornamental embroidery is exhibited. The Museum of Fine Arts presents the works of fine and decorative arts from the 18th to the 20th century.

An open-air museum of wooden architecture Vitoslawlizy illustrates the wooden architecture of Russia. It stands near the Yuriev Monastery and is one of the most popular places for recreation among Novgorodians. Founded in 1964, the museum covers an area of 33.4 hectares . By 2005, 20 remarkable buildings from Russia had moved to the museum grounds and thus saved from collapse. One of the oldest wooden buildings in the Novgorod region is also located here, the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary from 1531 from the village of Perjodki.

Buildings

Novgorod Kremlin

The entire old town on both sides of the Volkhov is worth seeing, in the west including the Novgorod Kremlin, which was first mentioned in 1044. The Kremlin was commissioned by Prince Yaroslav the Wise . The Kremlin stands on a hill about ten meters above the Volkhov and is enclosed by a 1487 meter long wall. This was reinforced with twelve towers, nine of which have been preserved. The total area of the Kremlin with 565 meters north-south and 220 meters east-west is 12.1 hectares. The walls are made of bricks and chunks of limestone. The wall thickness varies between 3.6 and 6.5 meters; the height varies between 8 and 15 meters. A special feature of the Novgorod Kremlin are the churches built above the gate entrances. The Novgorod archbishops played the largest part in the establishment of the Kremlin, while the elected princes had little influence. In the 1950s and 1960s, the masonry was restored under the direction of A. Vorobjow and represents the state of the 15th century.

St. Sophia Cathedral

The Cathedral of St. Sophia (Russian Собор Святой Софии ) in the Kremlin of Veliky Novgorod is the cathedral of the Archbishop of Novgorod and the mother church of the Novgorod eparchy. It was first built of wood in 989, had 13 domes and was consecrated by Bishop Ioakim Korsunjanin, but then burned down. Between 1045 and 1050, Vladimir of Novgorod had the 38 meter high stone church with five domes built. It was consecrated by Bishop Luka Schidjata (1035-1060) on September 14, 1050 (or 1052) and was supposed to commemorate the victory over the nomadic tribe of the Pechenegs . The choice of the main saint was based on the Church of St. Sophia in Kiev and especially the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople . The famous bronze doors were cast in Magdeburg between 1152 and 1156 . The doors for the Cathedral of the Assumption in Płock were originally created. They came to Veliky Novgorod in the 13th or 14th century under unexplained circumstances. In 1981, copies were made for the cathedral in Płock and placed there. There is a wall of bells at the rear of the cathedral. The wall, first mentioned in the 15th century, has been rebuilt several times and today dates from the 17th century. Bells, which were cast in the 16th and 17th centuries, stand on small platforms in front of the wall, which tourists can climb in the summer.

Jaroslaw-Hof on the old market square

The location of the Yaroslav court is on the right bank of the Volkhov, opposite the Kremlin. According to legend, Prince Yaroslav the Wise had a palace built on this square in the 11th century. In the 17th century, most of the buildings of a trading yard that stand here today were built. The complex consists of monuments from the 12th to 18th centuries. The oldest church is the Nicholas Cathedral, which was built from 1113 to 1136.

National Monument Thousand Years of Russia

The national monument in front of the Cathedral of St. Sophia in the Novgorod Kremlin, inaugurated in 1862, marked the millennium of the beginning of Rurik's rule in Novgorod, which is widely considered to be the beginning of Russian history and statehood. The creator of the project was Michail Ossipowitsch Mikeschin , who won a tender from 40 sculptors and architects in 1859. Mikeschin, who was inspired by the unexpected bid and the responsible commission, drew many well-known sculptors of his time, including Viktor Hartmann , Schreder, Tschischow, Saleman, Opekuschin , Lyubimow and Michailow. When creating the monument, the history of Russia, but also the role of the ruling house of Romanovs, had to be taken into account. The figures on the monument had to be personally accredited by Tsar Alexander II during the planning phase . The project reflects the contemporary transition from classicism to realism, in that the upper part with the angel and the allegorical personification of Russia is still classicist, while the lower part is realistically depicted. The monument was opened on September 8, 1862, in the presence of the Tsar. In 1925, after the October Revolution , Moscow ordered the demolition of the “ Monument to Orthodoxy and Tsarism ”. However, the local authorities decided to "hide" the monument. It was covered with wooden boards on which revolutionary posters and banners hung. So the monument survived until the beginning of the Great Patriotic War . Although it was already occupied by the Wehrmacht on August 15, 1941 , the Germans only began to dismantle the monument in December 1943, until the city was liberated by the Red Army on January 20, 1944 . The monument was so damaged that 1,500 missing details had to be remade. The second official opening took place on November 2, 1944.

Churches and monasteries

The entire old town with churches, monasteries and the Kremlin since 1992 is part of the World Heritage of UNESCO . In a list from the 15th century, 81 churches in Novgorod were counted, but not all of them were built of stone. The number of preserved churches is comparatively large at 52. The most famous are the Church of St. Boris and Gleb in Plotniki, the Church of St. Demetrius, the Church of St. Nicholas and the Church of the Assumption of the Virgin in Volotovo.

The foundation stone for the St. Nikolai Church in the Jaroslaw Hof was commissioned by Prince Mstislaw in 1113 after he had successfully completed a campaign against the Tschuden , a Finno-Ugric tribe. In particular, the Nikolai icon played an outstanding role.

The St. Peter and Paul Church in Koschewniki was built in 1406 and restored in 1950.

The Church of the Twelve Apostles was first mentioned in 1230. This first known wooden church burned down and was rebuilt in 1358. This building, also destroyed by fire, was replaced in 1432 by a church commissioned by Archbishop Euthymius II . In 1453 the stone building was built instead of the wooden church.

The Boris and Gleb Church was built in 1536 on the foundations of an older wooden structure from 1377. Instead of the single dome used since the 12th century, the new building consists of five domes.

The Juryev Monastery (Russian Юрьев монастырь ) with the St. George's Church is one of the oldest monasteries in Russia. It was mentioned for the first time in 1119 in the chronicles, but the foundation will go back to Yaroslav the Wise in the 11th century. It stands south of Novgorod on the river bank of the Volkhov near the outflow from the Ilmen Lake. The monastery was the main center of the Novgorod Republic. It is an important source for the history of Novgorod, as parts of the Novgorod Chronicle (1016–1471) were written within its walls . St. George's Church is the largest in Novgorod and the surrounding area. It is 33 meters high, 28 meters long and 25 meters wide with three silver domes (which is unusual as Russian Orthodox churches usually have five domes; one represents Christ and the other four the Evangelists). During the Soviet era, the monastery was looted in 1928 and five of its six churches were destroyed. It was closed in 1929 and occupied and seriously destroyed by German and Spanish troops during World War II. It was only returned to the Russian Orthodox Church in 1991 and has been partially renovated since then. Nevertheless, the western part with a church there are still ruins.

The Antonius Monastery (Russian Антониев монастырь ), located in the north of Novgorod on the Volkhov, was the greatest competitor of the Juryev Monastery in terms of importance. The monastery was founded in 1106 by Antonii Rimlianin , who according to legend fled Rome on a rock to Novgorod, and consecrated in 1131 by Archbishop Nifont (1130-1156). The most important church in the monastery is that of the Nativity of the Blessed Mother, a building with three domes like the St. George's Church in Juriev Monastery. It was started in 1117 by Antonii Rimlianin and completed in 1119. The rock on which Rimilianin is said to have fled can be seen in the church. Some frescoes from the Middle Ages (1125) have been preserved in the chancel, but most of them date from the 16th and 17th centuries. Some of the frescoes were seriously damaged during restoration work. The monastery is owned by the United Novgorod Museums and has not been returned to the Russian Orthodox Church.

The Arcadius Monastery (Russian Аркажский монастырь ) was one of the most important monasteries in medieval Novgorod. It is four kilometers south of the city, west of the Juryev monastery. Only the Church of the Assumption of Mary still testifies to the location of the monastery. The foundation walls of the monastery were excavated archaeologically in 1961. The monastery was founded in 1153 by Arkadius before he was elected Bishop of Novgorod (1156–1165). The church, initially built in wood, was replaced by a stone building by Simeon Dibakevits in 1188 and consecrated by Archbishop Gawriil (1186-1192) the following year. Many possadniks supported the monastery over time. In 1206 Possadnik Tverdislav Mikhailovich had the Simeon Stylites Church built over the gate. The church of Archangel Michael had Isaak Onkifow built in stone in 1395 and renovated in 1407 by Possadnik Yuri Dmitriewich and his cousin Jakob. In 1764 the monastery was destroyed.

The Chutyn Monastery (Russian Хутынский Спасо-Преображенский Варлаамиев монастырь ) was one of the holiest monasteries in the Novgorod Republic. The monastery is located on the right bank of the Volkhov, about ten kilometers northeast of Novgorod in the village of Chutyn ( chudoi [ худой ], "bad, poor"). The monastery was founded in 1192 by the former Novgorod boyar Oleksa Mikhailovich, whose monastery name became Varlaam . The church was consecrated by Archbishop Gawril the following year. Catherine the Great had the neoclassical bell tower built. The monastery was closed in 1925. In 1993 the monastery was re-established with a women's convent, although it had housed a men's convent for the longest time.

Sports

- The Novgorod football club plays in the central stadium in the Dynamo sports complex in the northeast of the city. Furthermore, the "Wolna Stadium" is located in the northwest.

- The Novgorod region is one of the best areas for rafting in Russia.

- Garry Kasparov won the international chess tournaments in Novgorod in 1994, 1995 and 1997 .

- In the southwest of the city there is an autodrome and a cartodrome.

Regular events

The New Year in Veliky Novgorod will be followed by the “Christmas Star” program with the “Kudesy” folk art theater from January 6th to 18th. In February or March there are events for " Carnival ". The fashion and design festival takes place every year in February or March. The “Russian Music” art festival follows in March with the winners of Russian and international competitions. From March 20 to April 8, the memorial days for SW Rachmaninov are held. Every year in April, the “Clean Thursday” festival is held, a special girls' festival with traditional washing customs and plaiting. On April 18, the battle on Lake Peipus will be re-enacted, the re-enactment event in honor of Alexander Nevsky’s victory . The International Festival of Folk Art “Sadko” and the so-called “CITY DAY” follow in June. August is marked by the interregional summer festival of the author's song "North-West" and ends with the equestrian festival in Borowitschi on 30/31. August. On the third Saturday of September the folk festival "Waldajskije Baranki" invites and on 17./18. September the bell art festival "Slatosarnye swony". The year ends with concerts, initially the "Festival of Western European Music" on October 1st, the concert of the Novgorod Region Governor's Fellows in the last week of November and the concert of the Fellows of the Federal Office for Culture and Film in the third week of December. The New Year's Fair of Folk Crafts and Crafts “Novgorodskaya Yarmarka” takes place in the second week of December, and the “Roshdestvensky podarok” ( Christmas present ) arts festival on December 25th.

Economy and Infrastructure

Economic sectors

The gross regional product of the Novgorod Oblast is 87.6 billion rubles, which is about 0.3 percent of the GDP of all of Russia. The processing industry accounts for around 91.8 percent, including 31.1 percent in the chemical industry, 20.1 percent in food production and 12.3 percent in the woodworking industry. Energy generation (electricity and gas generation and water distribution) account for 7.9 percent and raw material extraction (clay, limestone, quartz sand, peat) makes up 0.3 percent. Other branches of industry are mechanical engineering, cellulose and paper industry, black metallurgy and the fuel industry. The unemployment rate is 1.2 percent and is thus lower than in the rest of Russia (2 percent). Veliky Novgorod is the headquarters of one of the largest fertilizer manufacturers in the world, the Akron Group . The German company Pfleiderer , specializing in the manufacture of wood-based materials, has had a location in Veliky Novgorod since 2006, which was taken over by IKEA (Swedspan) in 2012 .

tourism

Around 30,000 tourists from 60 countries and 200,000 from Russia visit the city every year. Despite constant growth, the region's tourist potential has not yet been exhausted.

Theater, cinema and music

Novgorod has two cinemas: the “Novgorod” and the “Kinozentr”, each with three halls. It also has three theaters: the Novgorod Academy Theater Fyodor Michailowitsch Dostojewski founded in 1853 , the Drama Theater created in 1924 and the Novgorod City Theater for children and young people "Mali", which opened in 1990 . The city also has a philharmonic orchestra. The folklore theater "Kudessy" is a specialty. It has existed for 20 years and, along with ten other Russian Folk Culture Theaters, has been recognized by UNESCO as a “World Heritage of National Culture”. Every year around 2700 concerts and theater performances take place in Novgorod, with over 400,000 spectators.

traffic

The city is located on the Russian trunk road M 10 Rossija , which is part of the European route 105 . This connects Moscow with Saint Petersburg and continues to the border with Finland.

On May 18, 1871, the 73-kilometer railway line from Chudovo to Novgorod was opened. She was initially as narrow-gauge railway in Cape gauge of 1067 mm gauge designed and was 1878 to to Staraya Russa (95 km) extended. During the First World War in 1916, the entire route was changed to broad gauge with 1524 millimeters. The section between Chudowo and Novgorod was partially redrawn. A year later, in 1917, the line from Novgorod to Batezkaya was built and extended to Luga in 1923 . Of the Novgorod - Valdai route , the eastern bypass of Lake Ilmen, only the section from Krestzy to Valdai (58 kilometers) was completed in 1916 . With the opening of the route from Novgorod to Pavlovsk in 1926, there was the first direct connection to Leningrad . During the Second World War , the route from Novgorod to Staraya Russa was destroyed and not rebuilt afterwards. In 1991 the line from Novgorod to Chudovo was electrified. The city has direct connections to Moscow (night trains), Saint Petersburg and other major cities in the northwest such as Pskov and Murmansk .

In addition to the rail link, there is a network of buses and trolleybuses . The trolleybus network has five lines and was established in 1995 as the first trolleybus system in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union . The bus network has direct buses to various cities, including Saint Petersburg.

The city's two airports are in Jurjewo and Kretschewizy . However, since the collapse of the Soviet Union, there have been hardly any flight movements. Novgorod Juryevo Airport ( IATA : NVR, ICAO : ULNN) is four kilometers southwest of Jurjewo. Before 1991 there were several regular flights to Minsk , Moscow and Krasnodar . The 1320 meter long asphalt runway is currently hardly used for flight movements, but for car races.

The second airport, Kretschewizy, is located eleven kilometers northeast of Novgorod. The former military airfield with a 2000 meter long concrete runway was expanded into a civilian international airport in 2009 for the 1150th anniversary of Novgorod and opened for air traffic in spring 2010. The nearest international airport is Pulkovo Airport ( IATA : LED) near Saint Petersburg, about 180 kilometers northwest of Novgorod.

media

Veliky Novgorod has a broadcaster operated by the autonomous non-commercial organization “Novgorod Oblast Television” (Russian : Новгородское областное телевидение ). There is also a branch of the Russian media network WGTRK with the name “Slawja” (Russian Славия ) and the television channel “Triada” (Russian Триада ) in the city.

education

The formation of broader strata of the population began very early in Novgorod. Yaroslav the Wise had already given the order to teach 300 selected children to read and write. This seems to have been one of the foundations for the extremely high literacy of the Novgorod population in the Middle Ages. This was not limited to men, but also applied to women, as some birch bark fragments written by women show.

Education

Today the educational infrastructure in the city consists of 64 pre-schools for 8,800 children, 40 secondary schools for 32,636 pupils, 30 secondary schools, six grammar schools and a lyceum for a total of 29,723 pupils. School No. 14 in Novgorod has a school partnership with the Marienschule in Bielefeld. Veliky Novgorod is still a university location and has four independent secondary educational institutions.

Further educational opportunities

The Yaroslav the Wise State University of Novgorod (NovSU) was founded in 1993 through the merger of the Pedagogical and Polytechnic University, into which the Agricultural Academy was later integrated. The university consists of 20 faculties, which are spread over seven universities and four vocational colleges. There is a school for the humanities, one for economics and management, one for teacher training and the polytechnic. The 14,000 students can choose from 64 diploma, 19 bachelor's and 11 master's courses and are supervised by 896 lecturers, 115 of whom have completed their habilitation. 335 guest students from 41 countries are currently studying at NovSU. The university has cooperation programs with 36 universities in 14 countries. In 2006 the NovSU was ranked 63 among the 215 classical universities in Russia.

- Department of the North-Eastern Academy of Civil Service Novgorod

- Novgorod Department of Distance Learning of the Saint Petersburg Academy of the Ministry of Interior of Russia

- Department of the St. Petersburg State University of Economics and Finance .

- Novgorod State Agricultural Academy

Personalities

- List of Novgorod Possadniks

- List of Archbishops of Novgorod

- List of Russian rulers

- Tribe list of the Rurikids

Honorary citizen

- Archbishop Lew Zerpizki has been an honorary citizen of the city since 1992 .

- Valentin Lavrentjewitsch Janin (1929–2020), historian and archaeologist

- Ninel Nikolajewna Kusmina (1937–2020), architect and restorer

sons and daughters of the town

- Sophie of Novgorod (1141–1198), wife of the Danish King Valdemar I the Great (1131–1182)

- Wassili Adodurow (1709–1780), mathematician, philologist and university professor

- Johann Daniel Schade (1730–1798), master builder working in Dresden

- Alexei Bogolyubov (1824-1896), landscape painter

- Ivan Goremykin (1839–1917), statesman, Minister of the Interior from 1895 to 1899 and two-time Prime Minister 1906 and 1914 to 1916

- Robert Reinhold von Wirén (1857–1917), Admiral of the Imperial Russian Navy

- Anton Arensky (1861–1906), composer

- Sergei Rachmaninov (1873–1943), composer

- Mstislaw Dobuschinski (1875–1957), painter, art critic and memoir writer

- Alexander Bakhtin (1885–1963), Lieutenant General

- Boris Numerow (1891–1941), astronomer and geophysicist

- Xenia Boguslawskaja (1892–1973), painter

- Boris Koschewnikow (1906–1985), composer and professor

- Vsevolod Kochetov (1912–1973), writer and cultural functionary

- Pāvels Seničevs (1924–1997), marksman

- Jurij Striedter (1926–2016), German Slavist and comparativeist

- Erik Kalugin (1937–2003), Russian rower

- Pyotr Rykov (* 1981), actor, television presenter, singer and model

- Marija Novolodskaja (* 1999), racing cyclist

Other personalities with connections to the city

- Theophana of Novgorod (* 941)

- Kirik von Novgorod (1110–1156), Russian monk and chronicler

- Pachomi Serb († 1484), biographer and hagiographer of the Russian aristocracy

- Silvester (Protopope) (late 15th century – 1565), was a Russian Orthodox clergyman, author, and confessor of Ivan the Terrible .

- Wassili Wassiljewitsch Schuiski (before 1500–1538), was 1500–1506 Muscovite governor of Novgorod

- Albert Burgh (1593–1647), Mayor of Amsterdam

- August von Denffer (1786–1860), governor of Novgorod

- Theophan Goworow also Teofan Pustelnik (1815-1894), was inspector and lecturer at the spiritual seminary in Novgorod in 1842

- Anna Haava (1864–1957), Estonian poet and translator.

- Jacob Johann Sievers (1731–1808), Governor General of Novgorod

- Weniamin Innokentjewitsch Sosin (1896–1956), Soviet chess master and important theorist.

- Nikolai Grigoryevich Wassiljew (1908-1943), Soviet lieutenant colonel and partisan commander, was head of the House of the Red Army in Novgorod

- Tamara Viktorovna Gladenko (1917–1991), Soviet architect and restorer of Novgorod churches and monasteries

- Nikodim of Leningrad (1929–1978), Russian Orthodox metropolitan, ecumenist and peace activist.

Media, literature and filmography

The plot of some literary texts is set in Novgorod and the surrounding area:

- The life of Alexander Nevsky (Russian Житие Александра Невского , 13th / 14th century)

- Marfa, the governor or submission of Novgorod , novella by Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamsin (1803)

- Andrew Drummond: Novgorod the Great. A novel. 2010. ISBN 978-1-84697-101-3 .

Due to the historical structure of the building, Veliky Novgorod is ideal as a background for various film and television projects. The following list shows a selection of films partially shot in Veliky Novgorod. Novgorod's archaeological plans also formed the basis for the installation of a wooden film set near Moscow.

- 1987: Portrait of the World USSR , Movie made for TV USA (with Roy Scheider; Director: John Purdie)

- 1997: Transit Bruges - Novgorod. 4000 km of European history (Director: Ulla Lachauer )

- 2001: DR-Explorer: Rusland , documentary (28 minutes; Denmark; director: Per Bjørn Rasmussen)

- 2004: Novgorod, lettres du moyen âge , documentary (52 minutes; France; director: Marc Jampolsky)

- 2008: 1-2-3 Moscow! , TV series (163 minutes; Germany; with Katrin Bauerfeind ; director: Irina Enders)

Others

The five- ruble note , which was put into circulation in 1997, shows motifs from the city of Veliky Novgorod. Novgorod is one of the seven cities in Russia that are represented on national banknotes. The front of the banknote shows the Cathedral of St. Sophia and the Monument to Thousand Years of Russia , and the reverse shows a section of the wall of the Novgorod Kremlin.

The asteroid (3799) Novgorod , which was discovered on September 22, 1979 by the Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanowitsch Tschernych , is named after the city.

List of sources, literature and maps

swell

- Joachim Dietze: The first Novgorod Chronicle according to its oldest editing (synodal manuscript) 1016–1333 / 1352: Edition of the old Russian text and facsimile of the manuscript in reprint. in German transl. ed. and with an introduction by Joachim Dietze. Munich 1971.

- Robert Michell: The chronicle of Novgorod: 1016-1471. London 1914.

- Ludolf Müller (ed.): Manual for the Nestor Chronicle . Munich 1978 ff. (Previously published: Volumes I – IV)

- The Novgorod Schra: in seven versions from the 13th to 17th centuries. ed. by Wolfgang Schlueter. Lübeck 1916.

- A Source Book for Russian History from Early Times to 1517. Volume 1, New-Haven 1972.

literature

- Norbert Angermann and Klaus Friedland (eds.): Novgorod. Hanse market and office. Böhlau, Cologne et al. 2002, ISBN 3-412-13701-4 .

- Great Novgorod in Medieval History. Festschrift for the 70th birthday of Valentin Lavrentjewitsch Janin. Moscow 1999.

- Valentin Lavrent'evič Janin: Medieval Novgorod. In: The Cambridge History of Russia . Vol. 1: From Early Rus' to 1689, ed. By Maureen Perrie. Cambridge 2006, ISBN 978-0-521-81227-6 , pp. 188-212.

- Jörg Leuschner: Novgorod. Investigations into some questions of its constitution and population structure. (= Eastern European studies at the universities of the State of Hesse , 107). Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-428-04722-2 .

- Eduard Mühle : Hólmgarðr. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 15, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2000, ISBN 3-11-016649-6 , pp. 80-82. (Old Norse name for the early urban trading center Novgorod)

- Michael Müller-Wille (Ed.): Novgorod. The medieval center and its surroundings in northern Russia. Studies on the settlement history and archeology of the Baltic Sea regions. Volume 1, Wachholtz Verlag, Neumünster 2001, ISBN 3-529-01390-0 .

- Konrad Onasch : Großnowgorod and the realm of Saint Sophia. Church and cultural history of an old Russian city and its hinterland. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 1969.

- Donald O'Reilly: Alexsandr Nevsky - Russias Savior. In: Military History 4 (2004), pp. 58-80.

- Thomas Stiglbrunner: Novgorod in the High Middle Ages. Some aspects of culture and everyday history. (PDF) Diploma thesis, Vienna 2007, 135 pp.

- Michael W. Thompson: Novgorod the Great: excavations at the medieval city. directed by AV Artikovsky and BA Kolchin, London 1967.

cards

- Novgorod: Turistskij plan (scale: 1: 20,000), Leningrad 1990.

- Henrik Birnbaum : Lord Novgorod the Great; Essays in the History and Culture of a Medieval City-State. Part One: The Historical Background. (UCLA Slavistic Studies 2). Los Angeles 1981. Contains many historical phase plans.

- Valentin L. Janin: Plany Novgoroda Velikogo: XVII - XVIII vekov [City maps of Greater Novgorod from the 17th-18th centuries Century], Moscow: Nauka, 1999. ISBN 5-02-009587-7

Web links

- Tourist information "Rote Isba"

- www.novgorod.ru Official website (English)

- mojgorod.ru: Veliky Novgorod (Russian)

- Novgorod Ressources University Washington (English)

- Link catalog on Veliky Novgorod at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Itogi Vserossijskoj perepisi naselenija 2010 goda. Tom 1. Čislennostʹ i razmeščenie naselenija (Results of the All-Russian Census 2010. Volume 1. Number and distribution of the population). Tables 5 , pp. 12-209; 11 , pp. 312–979 (download from the website of the Federal Service for State Statistics of the Russian Federation)

- ↑ World Heritage List No. 604 (English)

- ↑ regnum.ru

- ↑ Novgorod - the office in the east ( Memento of March 2, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Jörg Stadelbauer: Space, resources and population. Information on political education (issue 281).

- ↑ Evgenij N. Nosov: A territory is created. The Prehistory of Northern Rus' and Novgorods. In Michael Müller-Wille (Ed.): Novgorod. The medieval center and its surroundings in northern Russia. Neumünster 2001, pp. 13–74, here p. 14

- ↑ Evgenij N. Nosov: A territory is created. The Prehistory of Northern Rus' and Novgorods. In Michael Müller-Wille (Ed.): Novgorod. The medieval center and its surroundings in northern Russia. Neumünster 2001, pp. 13–74, here p. 16 f.

- ↑ Erich Donnert: The ancient Slavic empire Kiev. Society, state, culture, art and literature from the 9th century to the middle of the 13th century , 3rd edition of the work from 1985, Berlin et al. 2012, p. 10

- ↑ Nosov, Evgenij N .: A domain arises. The prehistory of the northern Rus' and Novgorods, in: Müller-Wille, Michael (Hrsg.): Novgorod. The medieval center and its surroundings in northern Russia, Neumünster 2001, pp. 13–74, here pp. 54–70. See also Rolf Hammel-Kiesow: Novgorod and Lübeck. Comparison of the settlement structures of two commercial cities. In: Norbert Angermann, Klaus Friedland (ed.): Novgorod. Hanse market and office. Cologne et al. 2002, pp. 25–68, here pp. 30–33.

- ↑ Evgenij N. Nosov: A territory is created. The Prehistory of Northern Rus' and Novgorods. In Michael Müller-Wille (Ed.): Novgorod. The medieval center and its surroundings in northern Russia. Neumünster 2001, pp. 13–74, here p. 54.

- ^ First Novgorod Chronicle , Nestor Chronicle , for 859 the late Sophienchronik

- ↑ The fact that this was Rurikowo Gorodishche and not the later Novgorod proper is undisputed due to the archaeological findings, cf. Evgenij N. Nosov: A domain is emerging. The Prehistory of Northern Rus' and Novgorods . In Michael Müller-Wille (Ed.): Novgorod. The medieval center and its surroundings in northern Russia . Neumünster 2001, here p. 67, but also TN Jackson; AA Molchanov: The old Scandinavian name of Novgorod in the toponymy of the way "from the Varangians to the Greeks". In: Vspomogatel'nye istoriceskie discipliny 21 (1990), pp. 226-237. (Russian)

- ↑ Archaeological findings attest to the emergence of a Christian quarter in the castle town during this time.

- ↑ Valentin L. Janin: A medieval center in the north of the Rus'. The excavations in Novgorod. In: Michael Müller-Wille (Ed.): Novgorod. The medieval center and its surroundings in northern Russia. Neumünster 2001, pp. 75–98, here p. 83.

- ^ Rolf Hammel-Kiesow: Novgorod and Lübeck. Comparison of the settlement structures of two commercial cities. In: Norbert Angermann, Klaus Friedland (ed.): Novgorod. Hanse market and office. Cologne et al. 2002, pp. 25–68, here p. 33.

- ↑ a b c d Valentin Lavrent'evič Janin: Medieval Novgorod. In: The Cambridge History of Russia. Vol. 1: From Early Rus' to 1689. Edited by Maureen Perrie. Cambridge 2006, ISBN 978-0-521-81227-6 , pp. 188-212. (English)

- ↑ Database of Birch Bark Fragments (Russian)

- ↑ 999 Birchbark Manuscripts Discovered in Novgorod (English)

- ↑ Michael C. Paul: Was the Prince of Novgorod a 'Third-rate bureaucrat' after 1136? In: Yearbooks for the History of Eastern Europe 56 (2008), no. 1, pp. 72–113.

- ^ A. Poppe: Novgorod. In: Lexikon des Mittelalter, Sp. 1306.

- ^ Goehrke / Hellman / Lorenz / Scheibert: World History Russia. Volume 31, Augsburg 1998, ISBN 3-596-60031-6 , p. 107, on the other hand, are of the opinion that the city only had 30,000 inhabitants, which still makes it one of the largest in Northern Europe.

- ↑ For example Hans-Joachim Torke: Introduction to the History of Russia. Munich: Beck 1997, p. 43.

- ^ Gottlieb Christian Friedrich Mohnike (transl.): Faereyinga Saga or History of the Inhabitants of the Faroe Islands: in the Icelandic basic text with Faroese, Danish and German translations . Copenhagen 1833.

- ^ LK Goetz: German-Russian trade agreements of the Middle Ages. Hamburg 1916, pp. 86, 159 f.

- ↑ Lasse Nitz, Berend Schulte: Novgorod - the office in the east ( Memento from March 2, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Marina Bessudnova: The closure of the Hanseatic Kontor in Novgorod in 1494 in the context of the relations of the Grand Duke of Moscow to Maximilian of Habsburg. In: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 127 (2009), pp. 69–99.

- ↑ Norbert Angermann: The Hanseatic trading Novgorod according to the testimony of archaeological sources. Report on a Soviet publication. In: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 98 (1980), pp. 76–84, here p. 82.

- ↑ Description on gramoty.ru ( Memento of the original dated November 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Russian)

- ^ Goehrke / Hellman / Lorenz / Scheibert: World History Russia. Volume 31, Augsburg 1998, p. 103.

- ↑ Norbert Angermann: The Hanseatic trading Novgorod according to the testimony of archaeological sources. Report on a Soviet publication. In: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 98 (1980), 76-84, here p. 77 f.

- ↑ About the history of Novgorod ( Memento of the original from October 14, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Oskar Annweiler: The council movement in Russia from 1905 to 1921. Leiden, Brill 1958, p. 230.

- ^ Gerhard Ziegengeist: Science at the crossroads. Critical articles on Slavic studies, literary studies and East research in West Germany. Akademie-Verlag 1964, p. 34.

- ^ Peter Longerich: Heinrich Himmler: Biography. Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-88680-859-5 , p. 555.

- ^ President of Russia. Ukaz # 1533 of 28 October 2008 On the assignment to Veliky Novgorod of the Honorary title of the Russian Federation "City of Military Glory" (Russian)

- ^ Program for the celebrations of the XXIX. Hanseatic Days of the New Age ( Memento of the original from December 22nd, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Population figures in Novgorod

- ↑ According to ru-Wiki, the source is: ЦГА СПб., Ф. 1684, op. 4, д. 177, л. 114 .

- ↑ a b c Information from the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce ( Memento from July 11, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Henrik Birnbaum : Novgorod and Dubrovnik. Two Slavic City Republics and Their Civilization. Zagreb 1989, p. 11.

- ↑ Interfax statistics for all of Russia

- ^ Henrik Birnbaum: Novgorod and Dubrovnik. Two Slavic City Republics and Their Civilization. Zagreb 1989, p. 25.

- ^ Website of the FJC ( Memento of November 24, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) (English) of September 29, 2010.

- ^ Website of the FJC ( Memento of July 28, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (English) of September 29, 2010.

- ↑ Сайт избирательной комиссии Новгородской области , accessed July 17, 2019

- ↑ Administration Veliky Novgorod ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Russian)

- ↑ Mayor of Novgorod ( Memento of the original from December 19, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Russian)

- ↑ geraldika.ru: coat of arms of Veliky Novgorod ; Reviewed September 24, 2010

- ↑ geraldika.ru: coat of arms of Veliky Novgorod ; Reviewed September 24, 2010

- ↑ geraldika.ru: coat of arms of Veliky Novgorod ; Reviewed September 24, 2010

- ↑ Novgorod Region (Russia) Flags (English)

- ↑ Jumelage strasbourg.eu ( memento of June 23, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (French) of September 30, 2010.

- ↑ Board of Trustees between Bielefeld and Velikij Novgorod e. V. ( Memento of the original from August 11, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Sights and museums ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. dated September 29, 2010 (page no longer available)

- ^ Irena Daniec Jadwiga: An Enigma: The Medieval Bronze Church Door of Płock in the Cathedral of Novgorod. In: Dies (ed.): The Message of Faith and Symbol in European Medieval Bronze Church Doors. Danbury 1999, pp. 67-97. (English)

- ↑ Ursula Mende: The bronze doors of the Middle Ages. 800-1200. Munich 1983.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Krause, Ernst Schubert: The bronze door of the St. Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod. Leipzig 1968.

- ↑ Destroyed Russian Church built with the help of Germany, from: Orthodoxie aktuell 09/2003 ( Memento from August 17, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Cathedral of St Nicholas (English)

- ↑ Church of Sts Peter and Paul (English)

- ↑ Church of the Twelve Apostles (English)

- ↑ Church of Sts Boris and Gleb (English)

- ↑ St George Cathedral (English)

- ↑ Antoninew Monastery (Russian)

- ↑ Church of the Nativity of Our Lady (English)

- ↑ Arkadius Monastery (Russian)

- ↑ Novgorod FK website ( Memento of the original from September 22, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Russian) (page no longer available)

- ↑ What is Novgorod (English)

- ↑ Event calendar ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. dated September 29, 2010 (page no longer available)

- ↑ Swedspan takes over Pfleiderer's Novgorod plant , notification dated October 22, 2012 at EUWID. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ↑ Website of the theater ( Memento of the original from July 23, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Russian)

- ↑ Website of the theater (Russian)

- ↑ Example of music performances ( Memento of the original from October 14, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Videos from 2009), September 29, 2010.

- ↑ Cultural life ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. dated September 29, 2010 (page no longer available)

- ↑ Novgorod Bus Company (Russian)

- ↑ Valentin Lavrentévic Janin: Novgorod birch bark manuscript. In: Archiv für Diplomatik 41 (1995), pp. 211-238.

- ↑ Novgorod Education System (Russian)

- ↑ Stages of the school partnership

- ↑ University website

- ↑ Yanin's biography (Russian)

- ↑ Юбилей отметит Почетный гражданин Великого Новгорода Кузьмина Нинель Николаевна (accessed April 1, 2020).

- ↑ Erik Kalugin in the database of Sports-Reference (English)

- ^ Andrzej Poppe: Theophana of Novgorod. In: Byzantinoslavica 58 (1997), pp. 131-158; Andrzej Poppe: Theophana of Novgorod. In: Byzanz und das Abendland in the 10th and 11th centuries, ed. by Evangelos Konstantinou. Cologne 1997, ISBN 3-412-13595-X , pp. 319-350.

- ↑ Medieval Architecture (English).

- ↑ / Portrait of the World USSR in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ / DR-Explorer: Russia in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ / Novgorod, lettres du moyen age in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ 1-2-3 Moscow! in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ^ Lutz D. Schmadel: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names , 5th. Edition, Springer Verlag, New York 2003, ISBN 3-540-00238-3 , p. 321. (English)

- ↑ NASA orbit data (English)

- ↑ Digital map of Novgorod (Russian)