Homosexuality in Spain

Homosexuality is socially accepted in Spain . Spain is considered a liberal country when it comes to dealing with homosexuality . With the replacement of the conservative government by the socialists in 2005 , Spain became the third country in the world to allow homosexual couples to marry and adopt.

legality

Homosexual acts are legal in Spain and the age of consent for sexual intercourse in Spain is 16 years, as with heterosexuals. In November 2006, the Zapatero government passed a law allowing trans people to have their gender entered in public documents, even before they undergo surgery.

Recognition of same-sex marriages

On June 30, 2005, the Cortes Generales under the Socialist Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero passed the law that allows homosexual couples to enter into traditional marriages from July 3, 2005 and gives them all the rights of heterosexual couples, such as marriage . B. the adoption of children .

On June 27, 2007, two years after the law was introduced, the Spanish Ministry of Justice announced that 3340 couples had married by then. However, the number of homosexual marriages is possibly three times higher, as the data from the uninformed municipalities and those from the Basque Country could not be taken into account. According to the ministry, of these 3,340 marriages, 2,375 were between men and 965 were between women. Madrid is the autonomous region where the highest number has been registered (1060), followed by Catalonia (871), Andalusia (399), Valencia (263), Balearic Islands (116), Asturias (101), Castile and León (89) , Aragón (86), Canary Islands (83), Murcia (61), Castile – La Mancha (56), Extremadura (54), Galicia (31), Cantabria (28), Navarra (25) and La Rioja (13) .

On November 5, 2012, the Spanish Constitutional Court upheld the opening of marriage in Spain.

Adoption law

Since 2006, the Spanish government has been negotiating with other states to enable foreign adoptions. The artificial insemination law was also amended in 2006. Thus, the lesbian wife of the woman giving birth is also recognized as the parent.

Social situation

Homosexuality and bisexuality are accepted in the population, especially in big cities like Madrid , Barcelona , Valencia , Seville , Bilbao , Málaga , Zaragoza , Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and other cities with a lot of tourists and foreign populations like Santa Cruz de Tenerife and Cádiz . In addition, there are still cases of discrimination, especially in smaller towns and villages.

In the ILGA study “Rainbow Europe” , Spain always ranks first in Europe with regard to tolerance and rights for LGBT citizens. In 2010, Spain was in second place with Belgium, the Netherlands and Norway; In 2012 Spain held the second position again, this time together with Germany. The 2013 qualification put Spain in fourth place (65%) along with Portugal and Sweden; however, Belgium with 67% and Norway with 66% were closely in second and third place. Great Britain came in first with 77%. Spain came sixth in 2015 (69%), together with the Netherlands and Norway, well ahead of Germany (56%) and Austria (52%). This downgrade was justified by the ILGA because of some measures taken by the conservative PP government in health and social policy, such as the discrimination against lesbian women in state-paid artificial insemination .

In the 2013 study “The Global Divide on Homosexuality” by the Pew Research Center , Spain was given the top position in social acceptance among 39 countries; 88% of the population currently believe that »homosexuality should be accepted by society«. The same position was achieved in 2014. In a poll by Gallup , Spain was one of the four best countries for homosexual living in 2014. According to a survey by PlanetRomeo from 2015 among 115,000 of its users, Spain, together with Germany, ranks 13th worldwide in the "Gay Happiness Index".

In a study by The Hague Center for Strategic Studies from 2014, the Spanish army ranks tenth worldwide (91.8 points) in terms of LGBT acceptance, together with France and ahead of Germany, which is in twelfth place with 90.8 points behind Spain.

The CSD's annual demonstrations stunted after the first revival in the late 1970s, when cities like Barcelona, Madrid, Seville or Valencia had up to 5,000 demonstrators. In 1991 only 300 people took part in the CSD demonstration in Madrid. This tendency was not reversed until 1994, and the number of participants rose rapidly: in 2000, when the FELGBT organized a uniform CSD for the whole of Spain in Madrid for the first time, 60,000 people marched with them. This development reached its peak in 2007 when the Europride took place in Madrid: over 1.5 million people marched through the city center in 100 organizations and with 40 floats. This made it the largest CSD in Europe. The CSD in Barcelona, less commercial and more aggressive in calling for gay rights, stagnated in the late 1990s: only about 500 people marched in 1999, and about 900 attended the party afterwards. In contrast, gay entrepreneurs organized a Pride party that same year, attended by 6,000 people. This tendency broke off in 2000 when gay entrepreneurs and LGBT groups united in an event and 10,000 people marched along. In the meantime the CSD in Barcelona has developed into the second largest CSD in Spain, with 150,000 visitors in 2013. The largest “ Circuit Party ” in Europe is now being organized in Barcelona with 70,000 visitors.

LGBT culture

literature

At the beginning of the 20th century, Spanish homosexual writers such as Jacinto Benavente , Pedro de Répide, José María Luis Bruna, known as Marqués de Campo, or Antonio de Hoyos y Vinent had to choose between ignoring the topic or portraying it negatively. Only foreigners living in Spain published literature in which homosexuality became visible: the Chilean Augusto d'Halmar wrote Pasión y muerte del cura Deusto ("Passion and death of the priest Deusto"), the Cuban Alfonso Hernández Catá published El ángel de Sodoma (»The Angel from Sodom«) and the Uruguayan Alberto Nin Frías wrote La novela del Renacimiento. La fuente envenenada ("The Renaissance novel. The poisoned spring"), Marcos, amador de la belleza ("Marcos, lover of beauty"), Alexis o el significado del temperamento Urano ("Alexis or the meaning of the uranic temperament") and, in 1933, Homosexualismo creador ("Creative Homosexualism"), the first essay to put homosexuality in a positive light.

Others hid behind the vague language of poetry, such as the authors of the Generación del 27 , whose homosexual and bisexual authors Federico García Lorca , Emilio Prados , Luis Cernuda , Vicente Aleixandre and Manuel Altolaguirre can be counted. These poets were influenced by the great homosexual writers in Europe, such as Oscar Wilde , André Gide , mainly his Corydon , or Marcel Proust . At that time Emilio García Gómez published Poemas arabigoandaluces ("Arabic-Andalusian Poems"), the first time that the homoerotic poems of Spanish-Arabic poets were published in Spanish without censorship.

There was also a shy revival of lesbian literature at the beginning of the 20th century. The first work to take up the subject was the novel Zezé (1909) by Ángeles Vicente. In 1929 the first play was premiered, Un sueño de la razón ("A Dream of Reason") by Cipriano Rivas Cherif. The only author who dared to write homoerotic poetry was Lucía Sánchez Saornil, although she did it under a male pseudonym.

In the mid-1930s, the slow build-up of gay and lesbian literature was brutally ended by the civil war. After the war, with Lorca's death and the majority of homosexual authors in exile, literature withdrew again into the dark poetry of Vicente Aleixandre, a poet who never publicly recognized his homosexuality. Other gay poets of the time were Francisco Brines, Juan Gil-Albert and Jaime Gil de Biedma and, in Córdoba , the Cántico group, Ricardo Molina, Vicente Núñez, Pablo García Baena, Julio Aumente and Juan Bernier.

Among those authors who became known between the end of the dictatorship and after the Transición , the following must be mentioned: Juan Goytisolo , the most influential outside Spain, a poète maudit in the tradition of Jean Genet ; Luis Antonio de Villena , the gay intellectual who best presents the subject; Antonio Gala and Terenci Moix , best known in Spain for their frequent appearances on television. Not so well known are Álvaro Pombo , Antonio Roig , Biel Mesquida, José Luis García Martín, Leopoldo Alas, Leopoldo María Panero, Vicente García Cervera, Carlos Sanrune, Jaume Cela, Eduardo Mendicutti , Miguel Martín, Lluis Fernández, Víctor Monserrat, Alberto Cardín, Mariano García Torres, Agustín Gómez-Arcos and Juan Antonio González Iglesias. For the Catalan language, Terenci Moix, Lluís Maria Todó and the Mallorcan Blai Bonet can be mentioned.

Until the late 1990s, there were no Spanish women writers who publicly recognized their homosexuality. For example, Gloria Fuertes didn't want it to be public. The first female writer to publicly admit it was Andrea Luca. Among the authors who have dealt with the topic, Ana María Moix, Ana Rosetti, Esther Tusquets , Carmen Riera, Elena Fortún, Isabel Franc and finally Lucía Etxebarría with her novel Beatriz y los cuerpos celestes (»Beatriz and the heavenly bodies«) , Premio Nadal 1998. For Catalan, reference can be made to Maria Mercè Marçal.

In the last years of the 20th century (and in the first of the 21st) the first publishers specializing in LGBT topics appear: the Egales publishing house (founded in 1995), the Odisea publishing house (founded in 1999) and the Stonewall publishing house ( founded in 2011). Odisea has been awarding the Odisea Prize since 1999 for books with gay or lesbian content in Spanish. The Arena Foundation has awarded the Terenci Moix Prize for gay and lesbian novels since 2005. The Stonewall publishing house has held the Stonewall de Literatura LGTB prize since 2011. There are also several bookstores catering to the LGBT audience, the main ones being: Berkana and A different Life in Madrid, and Cómplices and Antinous in Barcelona. Until about 2011 there was also the Safo de Lesbos in Bilbao.

The 21st century has brought normalization towards homosexuality in Spanish society, which can also be seen in literature. Gay writers are published by mainstream publishers, as happens with the writers Luisgé Martín or Óscar Esquivias. The critic Miguel Rojo says:

"Una homosexualidad del siglo XXI en un país avanzado que no genera más conflictos que si el protagonista fuera heterosexual o bizco."

"21st century homosexuality in an advanced country doesn't cause more problems than if the main character were straight or a squint."

This normalization can also be observed in children's and young adult literature. The publication of children's stories began in 2001, in which gender diversity and the rainbow family are treated in a child-friendly manner. In the same year La Tempestad published a story with male protagonists, which tells a love story between men, El príncipe enamorado ("The Prince in Love") by Carles Recio. In 2003 Paula tiene dos mamás ("Paula has two mothers") by Léslea Newman and La princesa Ana ("The Princess Anna") by Luisa Guerrero, both with lesbian main characters. This last work was set up for the theater in 2010, with which the Tarambana theater group won the “ Sal a escena contra la discriminación ” (“Come on the stage against discrimination”) award from the Ministry of Health, Social Policy and Equality in December 2010 .

movie theater

The beginnings of depicting homosexuality in Spanish cinematography were not easy because of Frankist censorship. The first film on homosexuality was Diferente ("Anders"), a musical by Luis María Delgado from 1961. The film was only able to survive the censorship because of its dreamlike and psychedelic plot. If homosexuality was discussed at all, until 1977 it was only the archetype of the funny / ridiculous queen , of which No desearás al vecino del quinto (»You shouldn't covet the neighbor on the 5th floor«), with Alfredo Landa , one of the best examples is. In the same year A un dios desconocido (Forty Years After Granada) was premiered by the directors Jaime Chávarri and Elías Querejeta , a drama with the Spanish Civil War in the background, the main character of which is a 50-year-old gay man.

With the transition , films were made in which homosexuality was no longer viewed negatively, such as Ocaña, retrat intermitent (1978; "Ocaña, intermittent portrait") by Ventura Pons or La muerte de Mikel (1984; "Mikels Tod") by Imanol Uribe . These films show different sides of the homosexual man: the upper class gay in Los placeres ocultos (1977; "The hidden pleasures"), the closeted politician in El diputado (1978; "The MP"), both by Eloy de la Iglesia , the transvestite in Un hombre llamado Flor de Otoño (1978; "A Man Who Was Called Autumn Flower"), the combative queen in Gay Club (1980), and others. Homosexuality is at the center of the plot, and gays are portrayed as vulnerable personalities, in conflict with themselves and with society.

As of 1985, homosexuality is no longer the main subject of the plot, although it still remains a cornerstone. This trend begins with The Law of Desire (1987) by Pedro Almodóvar and follows with films such as Tras el cristal (1986; »Behind the Glass«) by Agustín Villaronga, Las cosas del querer (1989; »The things of love«) and Las cosas del querer 2 (1995; »The things of love 2«) by Jaime Chávarri.

More recently, films such as Perdona bonita, pero Lucas me quería a mí (1997; “ Sorry, Honey , but Lucas loved me”), Segunda piel (1999; “Second skin”), Sobreviviré (1999; “I will survive "), Km. 0 (2000), Krámpack (2000), Plata quemada (2000;" Burned Money "), a coproduction with Argentina, Los novios búlgaros (2003;" The Bulgarian Fiancés ") and The Bear Club (2004 ) turned. The first gay- themed film shot in Basque , Ander (2009) by Roberto Castón, deals with homosexuality in rural settings, which is not often seen on the screen. In the following years, a cheerful view of the topic is often thrown, but always with respect and normality, as in Gay Mothers Without Nerves (2005) by Manuel Gómez Pereira, about the consequences of introducing gay marriage, Chuecatown (2008) by Juan Flahn or Fuera de carta (2008; »Outside the menu«) by Nacho G. Velilla.

The most famous expression of Spanish LGBT culture is without a doubt Pedro Almodóvar , the most respected Spanish director in the world. Almodóvar, as well as Ventura Pons and Eloy de la Iglesia, are the directors who deal with this subject the most in Spanish cinematic art. In September 2004 the director Alejandro Amenábar announced his homosexuality.

Films with a lesbian plot have been made much less. In the 1970s there was real inflation in the portrayal of lesbians in B-movies , from comedy to erotic, but mostly in fantastic and horror films (fantaterror) . These representations, often of the perverted lesbian or the vamp, were not directed at women, but were filmed to satisfy the lust drive of men. Only later, from the 1980s, were lesbian films made for women. These include the comedy A mi madre le gustan las mujeres (2002; »My mother likes women«) and 80 egunean (2010; »In 80 days«), a love story between two older women filmed in Basque.

The most important film festivals are LesGaiCineMad in Madrid and the "Festival internacional de cinema gai i lèsbic de Barcelona" (FICGLB). There are also countless smaller festivals, such as the “Festival del Mar en las islas Baleares”, the “Festival del Sol” in the Canary Islands, “Zinegoak” in Bilbao, “LesGaiFestiVal” in Valencia or “Zinentiendo” in Saragossa.

music

During the dictatorship, homosexuality was a big taboo in music. Perhaps the best lyricist of the time, Rafael de León , was gay and close friends with García Lorca, but his songs did not reveal this. Miguel de Molina , one of the few Copla singers who was unable to hide their homosexuality, had to go into exile after being banned from working and beaten several times. Towards the end of the dictatorship there were some singers who were said to be homosexual, as was the case with Raphael (some of his songs, such as Qué sabe nadie , "What no one knows", Hablemos del amor , "Let's talk about love", or Digan lo que digan , »Whatever they may say«, are viewed as encrypted LGBT songs), with Camilo Sesto or with Miguel Bosé .

Around 1974, the first song about a homosexual relationship was released, María y Amaranta , by the folk-rock group Cánovas, Rodrigo, Adolfo y Guzmán . Amazingly, the song was not banned by the censors. Towards the beginning of the transition there were few songs that addressed the subject. Exceptions were Vainica Doble with her song El rey de la casa ("The King of the House"), the story of a gay man who has to fight against the prejudices of his family, and Víctor Manuel , who dealt with LGBT in several of his songs. as in Quién puso más ("Who was most involved"), the true story of a love between two men that breaks after 30 years, Como los monos de Gibraltar ("Like the monkeys in Gibraltar"), about transsexuality, Laura ya no vive aquí (»Laura doesn't live here anymore«), about female homosexuality and No me llames loca (»Don't call me a fag / crazy«).

But only after the beginning of the Movida madrileña , these topics were no longer the exception. The duet Almodóvar and Fabio McNamara became famous for its fiddling on stage and the erotically provocative lyrics. Tino Casal , who never hid his homosexuality, became a gay icon. But possibly the group that identified itself best with the gay movement was Kaka de Luxe: Alaska , Nacho Canut, and Carlos Berlanga, later known as Alaska y los Pegamoides and Alaska y Dinarama. As Alaska y Dinarama, they created the song A quién le importa ("Who's it business"), which became the gay anthem par excellence in Spain. After the end of the Movida , the artists of this movement, such as Fabio McNamara, Carlos Berlanga or Luis Miguélez, continued to use these themes for their songs. Alaska's new project, Fangoria, also addressed homosexuality in songs like Hombres ("Men") or Si lo sabe Dios que lo sepa el mundo ("If God already knows, the world should know").

Towards the end of the 1980s, the Mecano group achieved huge success with their song Mujer contra mujer ("Woman against Woman"), a clear defense of the homosexual love of two women, an appeal for tolerance and respect. The subject was also treated with humor in her song Stereosexual . In 1988 the group "Tam Tam Go!" Achieved success in the charts with Manuel Raquel about a transsexual woman.

From the 1990s onwards, a new generation of singer-songwriters addressed homosexuality in their songs, mainly Inma Serrano , Javier Álvarez and Andrés Lewin, although others such as Pedro Guerra in Otra forma de sentir (»Another way of feeling«) or Tontxu in Entiendes ("Do you understand?") Did it. Other musicians from various musical genres also spoke about it, such as OBK in El cielo no entiende ("Heaven does not understand"), Mónica Naranjo in Entender el amor ("Understanding love") and Sobreviviré ("I will survive"), Malú in Como una flor ("Like a flower"), Amaral in El día de año nuevo ("New Year's Day"), Chenoa in Sol, noche, luna ("sun, night, moon") and La diferencia ("the difference" ), Pastora Soler in Tu vida es tu vida ("Your life is your life"), Mägo de Oz in El que quiera entender que entienda ("Whoever wants to understand should understand") or La oreja de Van Gogh in Cometas por el cielo ("dragons in the sky").

In the alternative areas of indie pop Ellos can use Diferentes ( "other") and L Kan Gayhetera be mentioned. The Gore Gore Gays group was linked to the leather scene ; the lyrics are often a defense of a more open sexuality.

history

The Roman Empire

The Roman Empire brought its sexual morality to the Iberian Peninsula , along with all the other components of its culture. Therefore status was more important than the gender of the partner: men were allowed slaves, eunuchs or hustlers penetrate as well as slaves, concubines or prostitutes. Still, an adult Roman citizen with a good reputation would never have been willing to have sex with another citizen or to be penetrated at all, regardless of the status or age of his sexual partner. The social distinction between the active gay, who sometimes had sex with men and sometimes with women, and the passive gay, who was viewed as submissive and feminine, was very strict. This way of thinking was also used against Caesar , whose supposed love games with the King of Bithynia were on the lips of all Rome. In general, a kind of pederasty was practiced in Rome, similar to the Greek love for boys .

The lesbianism was also known, both in the sapphic form, a sort of female pederasty, had in the female Women having sex with young girls, as well as in the form of tribadism ' , followed in the masculine women male activities, including fighting, hunting and sexual or marriage-like relationships with women.

Martial , the great Hispanic poet and man of letters , was born and raised in Bilbilis (near Calatayud ) but spent most of his life in Rome. He recorded Roman life in poems and epigrams. In a fictional first person he talks about anal and vaginal penetration and fellatio of men and women.

Another example is Hadrian from Italica (now Santiponce ) in Hispania. He was Roman emperor from 117 to 138 AD. His lover Antinous or Antonius is famous , who found his death in the Nile and had Hadrian declared to be god; he founded the city of Antinoupolis in Egypt in his honor .

Christianization

Roman morality changed as early as the fourth century AD. The non-Christian Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus criticized the sexual habits of the Taifali , a barbaric people who lived between the Carpathians and the Black Sea and who practiced pederasty in the Greek style. In 342 the emperors Constantine II and Constantius II introduced a law to punish passive homosexuality: the punishment was most likely castration . The law was extended in 390 by Theodosius I by burning all prostitutes who worked in brothels. In 438 the death penalty was extended to all passive homosexuals, and in 533 Justinian I punished any homosexual act with castration and death by fire. The law was tightened again in 559.

There are three possible explanations for this change. Prokopios of Caesarea , historian at Justinian's court, suspected political reasons behind these laws, since Justinian could have political enemies removed in this way and cash in their wealth; after all, they had no effect on the lower social classes and possibly should not do so at all. The second reason, and perhaps the most important, was the spread of Christianity in Roman society, which now adopted the Christian conception of sexual intercourse solely for the purpose of procreation. In his book Homosexuality. Finally, A history , Colin Spencer mentions the possibility that a certain self-preservation instinct in Roman society had increased the pressure on individuals to procreate, for example after an epidemic such as the plague . This phenomenon worked together with the spread of Stoic thinking in the German Empire.

Up to the year 313 there was no unified Christian teaching on homosexuality, but before that Paul of Tarsus had criticized male behavior as "unnatural":

"...; for their wives have changed the natural intercourse into the unnatural, and likewise the men have also abandoned the natural intercourse with the woman, have become inflamed in their lust for one another, in that they disgraced men with men, and received in themselves the appropriate reward for their aberration self."

The church fathers slowly created a literary corpus in which homosexuality and sexuality in general were condemned; with this corpus a common widespread custom in Roman society and even in the Church itself was combated. On the other hand, homosexuality and heresy were soon linked, not only because of pagan customs, but also because of some rituals of Gnostic sects and Manichaeism , which, according to Augustine of Hippo, had homosexual components.

Visigoth Empire

In the early Middle Ages , the attitude of southern Europe towards homosexuality did not essentially change, but remained largely the same as in the Roman Empire. There is clear evidence that, while not accepted, “sodomites” faced no consequences. As examples we can refer to the Frankish king Clovis I , who admitted his male-male love in the 6th century, or to Alcuin , the Anglo-Saxon poet of the 9th century, whose verses and letters are clearly homoerotic . Gradually, however, Christian morality, which was based very much on the idea of sexual intercourse solely for procreation, caught up, and led to a complex variety of canonical orders that were heavily incorporated into legislation.

In 415 the Visigoths conquered Hispania. Under pressure from the Ostrogoths and Franks , the Visigoths were gradually pushed into Hispania, and Toledo became their new capital under Leovigild (569-586). The new rulers formed a Germanic elite that barely mixed with the Hispanic Romanic people. Germanic peoples despised passive homosexuality, the practitioners of which were treated like women, "imbezile" or slaves. Nevertheless, there is news of travested and effeminate priests from Scandinavian countries, and the sir , including the gods Thor and Odin , gained secret wisdom by drinking seeds .

In the Middle Ages, the Liber Iudiciorum (or Lex Visigothorum ) was one of the first legal corpora in Europe to introduce criminal liability for gay acts; it was published by King Chindaswinth (642–653) in the 7th century . This law punished sodomy with castration and handover to the competent bishop , who could impose the banishment . Castration was previously unknown as a punishment, except in the case of the punishment of circumcised Jews . If the offender was married, his marriage was dissolved, the dowry returned and his belongings distributed among the heirs. Sodomy was defined as any sexual offense that was classified as unnatural, including same-sex acts between men, anal intercourse (heterosexual and homosexual) and zoophilia . Lesbianism was only punished if phallic instruments were used.

In 693, King Egica ordered the bishops to resume homosexuality as an issue. That same year, during the 16th Council of Toledo , the bishops declared that "many men" had fallen into "sodomite vice". To stop its spread, they confirmed the punishments of the Chindaswinth and introduced an additional one hundred lashes and the shaving of the skull; in addition, the banishment should apply forever. They recognized that there was also sodomy among clergy, but set significantly lower penalties for it and only included secularization and exile. Later Egica extended castration and all other punishments to clergy.

Muslim rule

In 711, the Muslims conquered most of Spain. The flourishing culture of Al-Andalus exercised great tolerance in matters of sexuality in contrast to the Christians in the north and with the exception of the times of the Almoravids and Almohads . Paradoxically, the Koran forbids homosexuality and punishes it with death. The Risala fi-l-Fiqh , a summary of Islamic law written by Ibn Abi Zayd , Faqih of the Maliki School , states that men of age who voluntarily sleep together in one bed should be stoned . However, Muslim societies, both in the Iberian Peninsula and in the rest of the Muslim world, did not always obey this rule.

Important kings such as Abd ar-Rahman III. , Al-Hakam II. , Hisham II. And Al-Mutamid , had boys as lovers. The matter went so far that, in order to secure the offspring, a young girl had to be disguised as a boy in order to seduce Al-Hakam II. Such boyish love was widespread among the nobility and the upper classes.

Abdelwahab Bouhdiba describes the mood of this epoch vividly in his work Sexuality in Islam . Around Cordoba there were some large gardens that belonged to palaces and villas, sometimes even to Christian monasteries, where money was played and wine was drunk; Plays, singers and dancers provided entertainment. In this exuberant atmosphere, sexual intercourse was carried out relatively freely in the surrounding bushes, both heterosexual and homosexual, and prostitutes of both sexes were not infrequent. It is known that male prostitutes were paid better than women for a while.

Texts rejecting homosexuality are also known, and Ahmad ibn Yusuf al Tayfashi reports in his work Nuzhat-al-Albab (The Pleasure of the Heart) that men who see other men of the same age have a short life because they have that Took the risk of being robbed or murdered. The narratives in the book Nuzhat-al-Albab can be read in such a way that the Islamic society in Al-Andalus was positive, negative or indifferent to homosexuality. The author Colin Spencer thinks it is possible that all three settings were present at the same time.

Lesbianism was also known and especially prevalent in harems ; but these relationships were cultivated with caution because of possible abuse for political machinations. Some privileged women were educated, and there are two modern collections of Muslim women poetry in Al-Andalus by Teresa Garulo and Maḥmud Subḥ, in which love among women is presented impartially.

Andalusian homoerotic poetry

There is little evidence of homosexuality from this era; but most of them can be found in Andalusian homoerotic poetry , which was as popular as its counterpart in the Middle East . That poetry was rediscovered in the West in the 1920s, thanks to the publication of the book Poemas arabigoandaluces by Emilio García Gómez .

Usually these poems are dedicated to young men of the lower classes, slaves, or Christians, whose beauty and grace are praised, although there are also poems aimed at adult men. Often referred to as a gazelle or a deer , there is talk of the fluff with which an ephebe attains supreme beauty.

Among the poets, Ibn Hazm must be highlighted with his book The Dove's Collar . In this book, poems and anecdotes describe contemporary love games of both heterosexual and homosexual nature, from which sexual habits at court and among the nobility can be read. Other important poets were Al-Mutamid , King of Seville , Ben Qusman , Ibn Sara As-Santarini , Ben Sahl of Seville and Marŷ al-Kuḥl . As an example, a poem by Ibn Hāni 'Al-Andalusī , translated into Spanish by Josefina Veglison Elías de Molins and published in 1997 in La poesía árabe clásica :

“Woman, don't offend me.

Not Hind, not Zaynab seduce me.

On the other hand, I tend towards a deer

whose properties everyone longs for:

It does not fear menstruation,

It does not suffer pregnancy

and does not disguise itself from me. "

Jewish homoerotic poetry

During the golden age of Judaism in Spain , homoeroticism and homosexuality played an important role in Jewish society; this has only been discovered in the last few decades thanks to the work of Jefim Schirmann and Norman Roth . Jewish culture in Spain reached its peak in the 11th century; At that time, homosexuality was so widespread among the aristocracy that homosexuality was no longer an exception at all. Thus the Christian culture of the 13th and 15th centuries equated Judaism with perversion and sodomy, as the satirical poetry of the time shows; this condition can even be proven up to the 18th century.

Today we are no longer aware of how widespread Jewish homoerotic poetry was, as it is largely in Hebrew and has remained largely untranslated to this day. Some of the poets who portray their love for Ephebe and adult men were important figures in Jewish society or even rabbis . Important representatives of this poetry are Solomon ibn Gabirol , Samuel ha-Naguid , Moses Ibn Ezra and Jehuda ha-Levi .

The Christian Middle Ages

The Reconquista resulted in the reintroduction of Christian morality, but up to the time of the Catholic Kings people were relatively tolerant, mainly in the upper classes. While in the 12th century Muslims accused Christian clergy of sodomy, Christians in turn condemned Muslims in the south as soft, weak, and degenerate and cited as evidence that Muslims kept Christian young men in captivity as their sex slaves. The best-known case is that of St. Pelagius , who was executed for defying the advances of Abd ar-Rahman III. did not want to allow.

As early as the 12th century, the tone began to get darker. Saint Raimund of Peñafort coined the expression “ contra natura ” (unnatural) and demanded that any sexual act not carried out by a man and a woman with the appropriate organs “should be rejected and, if not punished, so but must be strictly rejected as sin. ”In the same century, usury, Judaism and sodomy were slowly equated with one another, and between 1250 and 1300 there were new laws in Europe that almost always punished sodomy with death. There is not much evidence that these laws were ever applied on a large scale, but they were often used as political extortion.

The only evidence of the application of these laws in the Iberian Peninsula comes from the Kingdom of Navarre . In 1290 a Mohr was burned in Arguedas for "lying with others". In 1345 Juce Abolfaça and Simuel Nahamán, two Jews from Olite , were burned for committing the Sodomite sin. Both inmates were tortured first to obtain a confession, then 20 people took them to the stake while a musician played the añafil . In 1346 a certain Pascoal de Rojas was burned in Tudela for "heresy with his body". A last known case was in 1373 when a servant was caught sodomy with another.

The Las Siete Partidas set of laws, enacted by King Alfonso X of Castile in the 12th century, punished all unnatural sins with death. The Partidas had adopted elements of the Codex Iustinianus , which, as has already been explained, condemned homosexuality. Sodomites and those who tolerated sodomy should be sentenced to death, with the exception of those under the age of 14 and those who were coerced into it against their will.

An example of the use of homosexuality as a means of political leverage is the trial of Pons Hugo IV of Ampuria , who fell into the disgrace of Jacob II of Aragon when he refused to take action against the Templars . The Templars were destroyed by Philip IV of France with the approval of the Pope, citing heresy and sodomy. The trial of the Templars was the first to use sodomy as a political weapon in Christian Europe.

One of the first known homosexuals in the Christian kingdoms of the Reconquista was the Infanta Jacob of Aragon and Anjou , heir to the throne of King James II of Aragon . From childhood it was decided that Jacob would be with Leonor of Castile , sister of Alfonso XI. of Castile , should be married. But in 1319 Jacob announced to his father that he would renounce the crown, that he would not marry and that he would continue to live as a clergyman. After much discussion he was convinced and married on October 18, 1319 in Gandesa Leonor. But as soon as the ceremony was over, Jacob renounced the crown at the court meeting that had been convened in Tarragona , gave the succession to the throne to his brother Alfonso IV of Aragon and entered a monastery. Later chroniclers did not forgive him for his decision, and he is portrayed as an irresponsible, immoral libertine:

«[…] Antes pareció que haber dejado la dignidad que tenía y la que esperaba tener como una pesada y molesta carga para que con más libertad se pudiese entregar a todo género de vicios, según después se conoció, con gran indignidad no sólo de su casa y sangre, sino incluso de la religón que había profesado »

"[...] as soon as he had left behind the dignity that he had and that he expected to have, like a heavy and obstructive burden, he could turn to all sorts of vices, as later became known, unworthy not only of his house and blood, but even the religion that he practiced. "

Another homosexual from the royal family was John II of Castile . Apparently, the relationship with his tutor and protector Álvaro de Luna was physical, as the historian Marañón claims. Don Álvaro, known for his good looks, gained so much influence over the king that he was named Condestable of Castile in 1422 , despite the nobility against the appointment. The relationship between John II and Álvaro de Luna became increasingly cold as a result of pressure from the family and the nobility until the king signed his death warrant in 1453. The king's homosexuality was apparently known, as the aristocrats who rose up insulted him as "puto" (fagot).

The son of Johann II, Heinrich IV. , Was also homosexual. At that time there were many rumors and criticism about his love games with men, such as B. with Juan Pacheco or Gómez de Cáceres; some even fled the court to escape the king's advances, such as Miguel de Lucas or Francisco Valdés. Since he was unable to father an heir with his wife, Blanca of Navarre , the rumor spread that he was impotent through songs and poems by Ménestrel and by fools . This was historically significant: because when his second wife, Joanna of Portugal , became pregnant, the nobility who had turned against him did not want to believe that the child really came from Heinrich, and called it "la Beltraneja", da Beltrán de la Cueva could have been the biological father in their eyes. The whole thing helped Isabella the Catholic to come to the throne of Castile. During a rebellion of the nobility in 1465, Heinrich was dethroned in the form of a doll at the Farsa de Ávila for "sodomism".

The examples of Jacob of Aragon, Johann II. And Heinrich IV. Show that at that time in the West homosexuality could be lived with a relative freedom, at least among the nobility. It was also the time when sworn brotherhoods developed, i.e. contracts between two men, which John Boswell equates with weddings between men, although there is no evidence that there was ever male sexual intercourse in a sworn brotherhood. As an example, here is a contract from 1031:

«Nosotros, Pedro Didaz y Munio Vandiles, pactamos y acordamos mutuamente acerca de la casa y la iglesia de Santa María de Ordines, que poseemos en conjunto y en la que compartimos labor; nos encargamos de las visitas, de proveer a su cuidado, de decorar y gobernar sus instalaciones, plantar y edificar. E igualmente compartimos el trabajo del jardín, y de alimentarnos, vestirnos y sostenernos a nosotros mismos. Y acordamos que ninguno de nosotros de nada a nadie sin el consentimiento del otro, en honor de nuestra amistad, y que dividiremos por partes iguales el trabajo de la casa y encomendaremos el trabajo por igual y sostendremos por igual y sostendremos a nuestign digual yadores por partes iguales el trabajo de la casa. Y continuaremos siendo buenos amigos con fe y sinceridad, y con otras personas continuaremos siendo por igual amigos y enemigos todos los días y todas las noches, para siempre. Y si Pedro muere antes que Munio, dejará a Munio la propiedad y los documentos. Y si Munio muere antes que Pedro le dejará la casa y los documentos. »

“We, Pedro Didaz and Munio Vandiles, join and agree together on the house and church of Santa María de Ordines, which are ours and where we work together; we take care of the visitors, their physical well-being, decorate and operate the facilities, plant and build. We also share gardening, food, clothing, and livelihood. And we agree that neither of us give away anything without the other's permission, for our friendship, and that we will divide the chores in equal parts and that the work be evenly contracted, and we will entertain our workers equally and dignified. And we will continue to be good friends with faith and truthfulness, and with others we will continue to be friends and enemies, day and night, forever. And if Pedro dies before Munio, he will leave Munio's property and documents. And if Munio dies before Pedro, he will leave him the house and the documents. "

Modern times

The first mass persecutions and executions began in Europe in the 14th century, in cities such as Venice , Florence , Regensburg , Augsburg and Basel , with trials following anonymous and verbal charges, with torture as an investigative measure and with moral and physical punishment up to and including death. In Castile, however, the first executions for sodomy did not take place until 1495.

The Catholic Kings tightened the laws against sodomites in a Pragmatic Sanction of 1497, with which the relative freedom of movement came to an end. The crime was equated with heresy and treason, a relaxed approach to evidence was introduced, and torture was systematically used, even against clergy and the nobility.

Philip II exacerbated the situation with his Pragmatic Sanction of 1592, in which the sentences did not get worse, but the evidence was even easier: from then on the testimony of a single witness was sufficient.

These trials were held either at court in Madrid or in city courts , such as B. in Málaga or Seville . Between 1567 and 1616, 71 men were burned at the stake in Seville alone for sodomy. In general, courts in the Crown of Aragon and Andalusia were less strict in persecuting homosexuals than in Castile. There are even signs of a gay ghetto in Valencia .

In the sixteenth century, moralists and moralists like Antonio Gómez discussed the case of lesbian women; the result was that women should be sentenced to the stake if they had committed sodomy with the aid of objects, but that a death sentence was not deemed necessary if they had dispensed with auxiliary objects. Few cases have been reported without the use of such auxiliary items. A famous case was that of Catalina de Belunza y Mariche, who was sued for sodomy by the Attorney General in San Sebastian . She was acquitted on appeal to the Central Court of the Inquisition in Madrid.

«[…] Penetrarse entre sí como lo harían un hombre y una mujer desnudas, en la cama, tocándose y besándose, la una encima del vientre o la panza de la otra, un crimen que habían perpetrado en numerosas y diversas ocasiones»

"[...] penetrate each other like a man and a woman, naked, on the bed, touching and kissing, one on the stomach of the other, a crime they have often committed."

society

During the Renaissance and the Enlightenment that followed later, men and women in Europe spent a good part of their lives separately from one another, which facilitated and promoted same-sex relationships of both a mental-emotional and physical-gender nature.

Although all sorts of homosexual incidents of that time are known from court records, most seem to have occurred between an older and a younger man or adolescent. The trials show frightened people who did not see what they were doing as sodomy. Many defended themselves fiercely, claiming it was a very common practice. Such encounters usually took place in public spaces: in baths, pubs and restaurants. In Madrid, 70% of those accused of sodomy were caught in public parks or baths, especially in some sections of the Paseo del Prado . Of the remaining 30%, most were men who shared their homes.

Across Europe, many homosexual relationships have been disguised as friendships . This type of idealized friendship, masterfully described by Montaigne in his essay De l'Amitié , differs markedly from today's use of the word. This friendship, which was mostly found among the nobility and at the courts of kings and popes, was often described in the same words as love and was incorporated into political intrigues and power struggles. In Spain, the Conde-Duque de Olivares had all bedroom door locks in the Royal Palace removed so that inspectors could ensure that no one among the hundreds of servants and officials was committing sodomite acts.

Lesbian love was also known in Europe and partly followed the male model, mainly in the upper and educated social classes, in which friendship played a large role. In the lower social classes, however, it was common for women to live alone, in groups with other women (mostly the poorest of them) or in noble houses where maids regularly slept together in groups, sometimes even with the housewife and housekeepers. This allowed a close intimate sphere among the women. There have also been reports of same-sex relationships among women in red light districts and prisons.

The inquisition

The medieval inquisition persecuted gay men; the offense was called sodomy , which, in the worldview of the time, represented the crime against morality. In Spain the act was punished with castration or with stoning .

With the emergence of the Spanish Inquisition and the other social and political changes introduced by the Catholic Monarchs , the punishment for sodomy changed: from now on the stake and expropriation in the worst case were planned, i.e. galley punishment , lashes , imprisonment, Fines or forced labor in other cases. Slaves were often exiled even when it was proven innocent. Torture was used during interrogation, although all under 20s were usually exempt; between 1566 and 1620 at least 23% of the accused were tortured. This new Inquisition condemned sodomy until the Grand Inquisitor decided in 1509 that it should no longer be prosecuted, except in the case of heresy. In Castile, for example, sodomy was no longer persecuted by the Inquisition, except in exceptional cases. In contrast, the Inquisition in the Crown of Aragon , with the exception of Mallorca and Sicily , regained jurisdiction over the offense, regardless of whether it was heresy , thanks to a papal bull of February 24, 1524, promulgated by Pope Clement VII or not. The Aragonese Inquisition retained this jurisdiction even after complaints presented at the Monzón Court in 1533.

The Aragonese dishes were very strict with sodomites, which could be both men and women. Anal intercourse , both homosexual and heterosexual, as well as zoophilia and the penetration of women with objects were considered sodomy . People convicted of sodomy were often priests and better-off people who were treated somewhat more leniently than those convicted of zoophilia, who were usually poor and uneducated. Many of the crimes were committed against young people, and most of the accused were foreigners, Italians or French, or priests from other areas. In the Crown of Aragon , the trials had to apply local law, which resulted in the names of the accused being published and often in acquittal. In the courts of Barcelona , Valencia and Zaragoza, 12% of the judgments were death at the stake; between 1570 and 1630 a total of 1000 people were convicted. The court in Zaragoza was particularly severe; between 1571 and 1579, 543 people were convicted of sodomy, of whom 102 were executed. From 1566 to 1775, 359 people were convicted in Valencia: 37 were handed over to execution, 50 were given a galley penalty, 60 were whipped, 67 were banished, 17 were imprisoned, 17 were fined, 10 were forced to work, and 62 were suspended or the accused released.

The fall of Pedro Luis Garcerán de Borja , son of the Duke of Gandía , brother of St. Francisco de Borja and Grand Master of the Order of Montesa , caused a sensation at the time. De Borja was arrested in 1572, tried in Valencia and found guilty. Apparently, some time before, Pedro Luis Garcerán de Borja had fallen in love with a certain Martín de Castro, a crook who made a living by prostitution and pimping with both men and women. Martín de Castro was caught in bed with Juan de Aragón, Count of Ribagorza , in 1571 , and before his execution at the royal court in 1574, he betrayed his relations with Garcerán de Borja, revealing all kinds of delicate details. Garcerán de Borja, who had been viceroy and captain-general of the kingdoms of Tlemcen , Tunis , Oran and Mers-el-Kébir , was embroiled in an internal crisis in the Order of Montesa, which was divided into different factions, and had many enemies because of each other involved in the promotion of his favorites within the order. The Suprema , the highest instance of the Inquisition, conferred with Philip II whether a trial should be brought against Garcerán de Borja; the king decided to politically exploit the process to teach the rebellious nobility a lesson while weakening the powerful alliance between the Borja family and the Portuguese royal family . Garcerán de Borja was sentenced to 10 years of seclusion and a fine of 6,000 ducats in annual installments of 1,000 ducats. After internal disputes over the successor to the office of Grand Master, Garcerán de Borja managed to make himself popular with the king again in 1583. He negotiated that the crown would incorporate the order, the last order that remained independent. In return, he received the encomienda of Calatrava , and in 1591 he was appointed Viceroy of Catalonia . He died in 1592.

A second important case, which is even of historical significance, is that of Antonio Pérez , royal secretary of Philip II Pérez, who was known as "El Pimpollo" (The Bud) in Madrid, rose in the king's favor thanks to the influence of the prince from Eboli , his lover. After falling out of favor with the king for infidelity and betrayal, he fled to Aragon , where the Inquisition arrested him for anal intercourse , among other things . The accusation was confirmed by the Inquisition in Madrid in 1591; there the squire Antón Añón had been questioned and tortured to the point of death. Other well-known cases of this period were those of Antonio Manrique, the Prince of Ascoli, Fernando de Vera y Vargas, Corregidor of Murcia , and Luis de Roda, Vicente de Miranda and Diego López de Zúñiga, Rector of the University of Salamanca , which, however, were able to save themselves.

Homosexuality and Art in the Siglo de Oro

The Renaissance is also the time of the rediscovery of the Greek and Roman heritage. Homoerotic art and stories reached Spain from Italy, like that of Ganymede and Zeus or Apollon and Hyakinthos , through artists, both heterosexual and homosexual, such as Leonardo da Vinci , Michelangelo or Sodoma . The connection between Italians and sodomite was constant in the Siglo de Oro and continued until the 20th century, when Marañón attributed Antonio Pérez's homosexuality to his visit to Italy. Or, as Luis de Góngora put it:

"Que ginoveses y el Tajo

por cualquier ojo entran bien"

"Because Genovesi and the Tajo

get in easily through every hole."

In the literature of the Siglo de Oro , ridicule, jokes and attacks on sodomites accumulate. As an example, a few lines from Quevedo :

«ÚLTIMA DESGRACIA: Finalmente, tan desgraciado es el culo que siendo así que todos los miembros del cuerpo se han holgado y huelgan muchas veces, los ojos de la cara gozando de lo hermoso, las narices de los buenos olores lo, b la boca de los buenos olores lo sazonado y besando lo que ama, la lengua retozando entre los serves, deleitándose con el reír, conversar y con ser pródiga y una vez que quiso holgar el pobre culo le quemaron. »

"LAST MISSION: Ultimately, the ass is so unhappy that, although all other parts of the body enjoy and have enjoyed it a lot, the eyes on the face rejoice in the beautiful, the nose in the good smells, the mouth in the well-spiced and kissing what he loves, dancing his tongue between his teeth, delighting himself with laughing, talking and generosity, and once the poor ass wanted to enjoy and was burned. "

The theater world was particularly suspect. The plot of the plays was often immoral, with men and women adopting the clothes and behaviors of the opposite sex, as e.g. B. can be seen in the play El vergonzoso en palacio by Tirso de Molina , in which Serafina pays court to both men and women. Mainly it was female characters who disguised themselves as men in order to enjoy their privileges. During the 16th and 17th centuries there were several attempts to put a stop to this immorality with certain regulations, such as the duty of the theater owner to provide information about the marital status of the actors, that the wives of the married actors had to be present during the performance, that women's roles were only allowed to be portrayed by young men or, in contrast, only by women, that men were not allowed to dress like women, etc.

The social pressures and the legal consequences meant that many sodomites hid their predisposition, and today only clues of what may once have remained. For example:

- El Greco lived in an all-male household in which his secretary Francesco Preboste (1554–1607) had an astonishingly close relationship with El Greco and his son Jorge Manuel Theotocopoli. Some of El Greco's paintings have a distinct homoeroticism, such as Laocoon (1604 / 1608–1614) or his Saint Sebastian.

- The sexuality of Cervantes was examined by Daniel Eisenberg. Eisenberg has used soft facts found in Cervantes' work, which leads him to the following conclusion: “He was not heterosexual either, in the same sense as the word is used today. If you want to call him bisexual , […] I couldn't deny it. ”Although he does not consider the terms heterosexual, homosexual or bisexual to be appropriate for the time.

- There were countless rumors about Luis de Góngora in the streets of Madrid; Songs and poems referred to him as Bujarrón (passive homosexual). Many descriptions of young male beauty can be found in his poems.

«CONTRA DON LUIS DE GÓNGORA Y SU POESÍA

Este cíclope, no sicilïano,

del microcosmo sí, orbe postrero;

this antípoda faz, cuyo hemisferio

zona divide en término italiano;

este círculo vivo en todo plano;

este que, siendo solamente cero,

le multiplica y parte por entero

todo buen abaquista veneciano;

el minoculo sí, mas ciego vulto;

el resquicio barbado de melenas;

esta cima del vicio y del insulto;

éste, en quien hoy los pedos son sirenas,

éste es el culo, en Góngora y en culto,

que un bujarrón le conociera apenas. "

- The historians Narciso Alonso Cortés and Gregorio Marañón tell of Juan de Tassis , Count of Villamediana and a close friend of Góngoras, that he had a post-mortem legal dispute over sodomy, the documentation of which they could see in the Archivo de Simancas , but which later disappeared . In his book Reyes que amaron como reinas, Bruquetas de Castro goes so far as to suggest a relationship between the murder of Villamediana and his knowledge of the sodomite excesses of King Philip IV of Spain . The mysterious assassination of Villamediana caused persecution of his close circles for sodomy. The first case was caused by the murder of the son of the Count of Benavente; Diego Enríquez, a relative, was charged and confessed to the crime; he admitted to having committed it out of jealousy caused by a love fight over a third man. Other cases included Luis de Córdoba, firstborn of the Count of Cabra, who was sentenced to death by Garrotte , and Diego Gaytán de Vargas, representative of the court in Salamanca.

- By Juana Ines de la Cruz is also because of the close friendships she had with some women whose beauty she extolled in poems, been claimed that she was a lesbian:

«Yo, pues, mi adorada Filis,

que tu deidad reverencio,

que tu desdén idolatro

y que tu rigor venero: […]

Ser mujer, ni estar ausente,

no es de amarte impedimento;

pues sabes tú que las almas

distancia ignoran y sexo. "

“I, my beloved Filis,

who adore your divinity,

who adores your contempt,

and who adores your severity: […] to be a

woman or to be away

is no obstacle to loving you;

because you know that

distance and sex do not count for souls . "

- There has also been speculation about the relationship between María de Zayas y Sotomayor , novelist, and Ana de Caro , dramaturge and essayist. Both lived together in Madrid and ate what they earned by writing, regardless of any man. Diaries, letters, and comments from contemporaries such as Alonso de Castillo Solórzano and modern scientists such as Maroto Camino have shown that both as a couple lived their love not only emotionally but also physically.

- Cosme Pérez , better known under the name Juan Rana ("Hans Frosch"), can be chosen from the actors . It is known from a contemporary comment that he was arrested for "nefarious sin", although he was later released. He became so famous as the «prankster des entremés » that entire plays were written for him: El doctor Juan Rana by Luis Quiñones de Benavente , Juan Rana poeta by Antonio de Solís , Juan Rana mujer by Jerónimo de Cáncer or El triunfo de Juan Rana by Pedro Calderón de la Barca , a total of 44 pieces. From the plays that were written for him, it can be said that the actor was probably affected and thus was performing on the stage for which he was famous.

Beginning of modernity

The custom of bringing homosexuals to a secular court and convicting them persisted until the mid-17th century, when there were no more public executions. This fact can be explained by a change in the sensitivity of Spanish and European society and the desire not to give sodomy a public space; the judges preferred to send the condemned to galleys or into exile. At the beginning of the 18th century only a few important cases were brought before the judge.

From the 1830s onwards, the Inquisition also changed its penalties, the number of those sentenced to death or the galley fell, torture and whipping gradually ceased, and exile, fines and forced labor were increasingly imposed as punishments: Politics changed from the containment [of homosexuality] through terror to a pure and simple politics of exclusion ”. Exiles, which made up 28.8% of convictions, could be temporary or lifelong, and usually related to the jurisdiction of the Court, although banishment from all over Spain was also possible in the case of foreigners.

Fernando Bruquetas de Castro explains part of the history of Spain , namely the rise of Godoy and the French invasion , with the homosexuality of King Charles IV. At that time it was well known among the people that Godoy was the lover of Queen Maria Luise of Bourbon-Parma was, but Bruquetas de Castro goes further and says Godoy was also the king's lover. In his opinion, this would be the only explanation to make the actions and reactions of Charles IV plausible: "[... He] was gay or stupid, maybe even both at the same time [...]" Other historians, such as Juan Balansó or Emilio Calderó, have downgraded the importance of the relationship between Godoy and Maria Luise in the rise of Godoy.

In 2004 the newspapers reported the possibility that the painter Francisco de Goya could have had a homoerotic relationship. The art history scholar Natacha Seseña wanted to recognize a homoerotic relationship in Goya's letters to his close friend and accountant Martín Zapater. The proof is in letters that remained unpublished until 2004:

«Martín mío, con tus cartas me prevarico ... me arrebataría a irme contigo porque es tanto lo que me gustas y tan de mi genio que no es posible habenrar otro y cree que mi vida sería el que pudiésemos estar juntos y cazar y chocolatear y gastarme mis veintitrés reales que tengo con sana paz y en tu compañía me parecería la mayor dicha del mundo (pero qué poltroncitos que nos volveríamos), y en realidad no hay otra cosa que apetecer en este mundo con que si me escribes por ese estilo me revientas y me haces pasar unos ratos que me estoy hablando solo y contigo horas […] »

"My Martin, your letters drive me crazy ... I would be carried away to go to you because I like you so much and you are so related to my soul that it is not possible for me to find anyone else and I believe to me, I would love to be with you for my life and hunt and chat and spend my twenty-three reales peacefully with you in your company, it would appear to me as the greatest happiness in the world (but how comfortable we would be), and really exist there is nothing that gives more pleasure in this world than when you write in this style that I burst and you let me talk to myself and you for a long time [...] "

" El que te ama más de lo que piensas " ("who loves you more than you think") or " tuyo y retuyo, tu Paco Goya " ("yours and yours again, your Franz Goya") are some of the texts and expressions you can find about it.

The 19th and early 20th centuries

legislation

At the beginning of the 19th century, liberal ideas spread from France and later from Krausismos , which originated in Germany. This led to the first Spanish penal code of 1822 that did not mention sodomy as a crime, during the so-called Trienio Liberal ; but it was abolished shortly afterwards. The offense of "sodomy" before and after still referred to the old concept of all sexual acts outside of the reproductive. It was not until 1848, with the new penal code, that sodomy finally disappeared, which was retained in the 1850, 1860 and 1870 versions. However, this does not mean that other laws could not be applied, such as the provisions against "public nuisance" (escándalo público) or the "offenses against morality, decency and good manners" (faltas contra la moral, el pudor y las buenas costumbres) .

The crime of homosexuality was made under the Penal Code of 1928 during the reign of Alfonso XIII. reintroduced with Section 616 of Title X:

"El que, habitualmente o con escándalo, cometiere actos contrarios al pudor con personas del mismo sexo será castigado con multa de 1,000 to 10,000 pesetas e inhibición especial para cargos públicos de seis a doce años."

"Anyone who repeatedly or under excitement of public nuisance violates morality with same-sex persons is punished with a fine of 1,000 to 10,000 pesetas and a special ban on the exercise of public office."

1,000 to 10,000 pesetas was a huge fine that only rich people could pay. Poor victims had to serve a prison sentence as a substitute. Women were also specifically mentioned in section 613:

«En los delitos de abusos deshonestos sin publicidad ni escándalo entre hembras, bastara la denuncia de cualquiera de ellas, y si se realizan con publicidad o producen escándalo, la de cualquier persona. En los cometidos entre hombres se procederá de oficio. "

“In sexual abuse crimes without public knowledge or public nuisance among women, it is sufficient for either [women] to report it, or if it is done with public knowledge or with arousing public nuisance, it is sufficient to report it of each. The crimes committed by men are prosecuted ex officio. "

This penal code was abolished by the new republic on April 13, 1931 , and the previous one from 1870 was reintroduced. The new Republican Penal Code of 1932 maintained impunity. With this, homosexuality among adult men was again exempt from punishment, with the exception of the military.

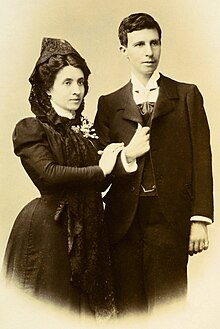

In 1901 the wedding of Spain's first known gay marriage took place. On June 8, 1901, Marcela Gracia Ibeas and Elisa Sánchez Loriga, two women, married in La Coruña , for which Elisa disguised herself as a man. When the deception was exposed, they both had to flee the country because they could no longer find work, the judiciary was persecuting them and society was putting enormous pressure on them. The marriage certificate was never canceled, however, which may have been due to the fact that the marriage was considered ineffective.

All this was not enough to create a homosexual movement , as was the case in Germany or even in France or England, which would have fought against the discrimination of gays and lesbians or would have stood up for their own appreciation. However, there are individual voices that even spoke out in favor of gay marriage. So José María Llanas Aguilaniedo in a text from 1904 in the Madrid magazine Nuestro Tiempo :

«El homosexual entre individuos de sexo contrario, tan insatisfecho resulta como si se hallara aislado en el desierto; y un individuo insatisfecho es al fin un inútil; nada puede ni hace; ó viene á loco ó á un obseso peligroso. Apareado, en cambio, con otro homosexual, resulta apaciguado y puede ser útil á los demás. La molécula, el verdadero elemento social, quedan tan cerrados en este caso como en el matrimonio corriente, pues hay en la pareja amor, hay ayuda y sostén, lugar de reparo para la lucha y satisfacción perfecta del instinto, la única apetecida.

Si no se había presentado aún esta cuestión, es indudable que algún día, por muy triste y antipático que hoy nos parezca, ha de presentarse para su resolución.

¿Por qué no ocuparse en serio de ella ya? »

“The homosexual among individuals of the opposite sex is as dissatisfied as if he were isolated in the desert; and an unsatisfied individual is ultimately useless; she can do nothing, she does nothing; either she goes mad or a dangerous man possessed. On the other hand, mated with another homosexual, she is calm and can be useful to others. The [social] molecule, as a real social element, remains just as complete in this case as in the case of normal marriage, because in togetherness there is love, help and support, a place of rest for struggle and a perfect satisfaction of instinct, the only one desired .

If none of these questions have ever been asked, there is no doubt that there will come a day, no matter how sad or disagreeable it may seem to us today, that this should be presented as the solution.

So why not get serious about it right away? "

Subculture and names

Among the politicians and rulers of the 19th century, Francisco de Asís de Borbón , husband of Queen Isabella II , and Emilio Castelar should be mentioned. The homosexuality of the former was well known among the people. There were innumerable anecdotes about it, and in Madrid there were pennies:

"Paquito Natillas

que es de pasta flora,

orina en cuclillas,

como una señora."

"Franzi vanilla pudding

made from shortcrust pastry,

he pees sitting down

like a lady."

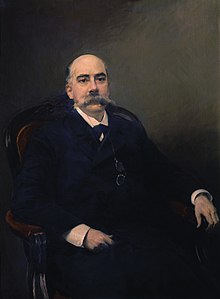

Castelar's homosexuality is and was nowhere near as well known, although some newspapers then called him "Doña Inés del Tenorio". Bruquetas de Castro tells a tender love story between Castelar and José Lázaro Galdiano , which in the end broke because of the difference in age and interests.

Homosexual men from exalted circles could be found in the Café de Levante and Café del Vapor in Madrid or in the Chinese Quarter of Barcelona, often in expensive hotels. As in other countries, there was a certain identification of homosexuality with the aristocracy, as evidenced by the figure of the Marquis of Bradomín in the story "Estío" by Valle Inclán or the author Antonio de Hoyos y Vinent himself. In these places the » Señoritos « and » Señorones « could be found. Señorones were rich and somewhat older men who are now known as sugar daddies and who took ephebic youths from the lower social classes as protégés , the so-called señoritos .

The homosexuals from the lower classes were usually divided into the " locas ", literally "crazy", queens , effeminate men who often took on female roles, and " chulos ", literally "pimps", men from the lowest social classes who however, did not see themselves as homosexuals, as they took the active role in the sexual relationship. The Chulos often got themselves paid for their services, which at the same time gave them an excuse not to consider themselves gay: they only did it for money.

Towards the end of the 19th century, public tuna balls became widespread in Madrid and Barcelona, such as the one held in 1879 at La Alameda on Alameda Street in Madrid on the last day of Carnival . "Over a hundred sodomites in elegant clothes and rich jewelry" took part. All of this was gone by the beginning of the 20th century; possibly it was public nuisance laws that led gays to retreat to private clubs and apartments. This subculture is transmitted mainly in literary, criminal and medical texts, which led to the homophobic attitude inherent in these texts, which was widespread at the time. Homosexuals were "baptized" in ceremonies described by Teodoro Yáñez in 1884 as follows:

«[En determinados días se admitían socios nuevos en el club ...] y despues [ sic ] de acreditar que no habían conocido varon [ sic ] con dos testigos, se les ponía una túnica blanca y una corona de azahar, y se les paseaba por el recinto, haciendo luego uno de ellos la primera introduccion [ sic ]. »

"[On some days new club members were admitted to the club ...] after they had given two witnesses to prove that they had not" recognized "a man; then they were given a white tunic and a crown of orange blossoms and they were driven across the room; later one of them would do the first introduction. "

Other, similar ceremonies were "weddings" and "births":

«The ceremonia del paritorio es complicada y variable en cada caso. Celébranse en lugares de reunión, algunos de los cuales se han hecho famosos. Aparece un uranista en traje femenino, con el vientre abultado, andando penosamente. El supuesto médico y la reunión de amigos, deudos y familiares, alarmados, oblíganle a tenderse en el lecho, prodíganle toda clase de cuidados, refrescan con paños mojados su frente y sienes, sobreviniendo, al fin, tras una larga y ena simulada, medio de grandes alaridos, el alumbramiento del muñeco, que es inmediatamente presentado al oficioso senado de expectantes. La más viva alegría se pinta en las caras; corre el vino a raudales, y el suspirado desenfreno hace al fin su aparición ente la grotesca turba. "

“The 'birth' ceremony is complicated and changes every time. It is carried out in certain meeting places, some of which later became famous. A Urninger appears dressed in a feminine manner, with a swollen belly who has difficulty walking. The supposed doctor and the pretend friends, relatives and family are together and alarmed, lay him on the bed, look after him lovingly, refresh him with wet towels on his forehead, until finally, after a simulated fight and in the midst of great shouts, to the A doll is born, which is immediately shown to the waiting audience. They are happy and the wine flows in large quantities until the expected licentiousness has found its way into the bizarre rabble. "

Also cabaret and revue were important centers of "Rüchigkeit," mainly during the years of Sicalipsis . In the café concerts there were even travesty performances, such as the case of Edmond de Bries, who sang the song Tardes del Ritz ("The Evenings of the Ritz") by Retana in 1923 disguised as a woman. Some songs even had homosexuality as their theme, always in the form of derision and ridicule , such as El peluquero de señoras ("The women's hairdresser") or ¡Ay Manolo! , sung by Mercedes Serós.

"Un pollito de esos que llevan

Las melenas hasta los pies

De este modo habló al peluquero

Con un poco de timidez:

" Quiero que me haga usted un peinado

Con raya al medio, en dos bandós,

Que sea así por el estilo

Del de la Cléo de Mérode "[…]

No hay un batidor en la ciudad

Que peine con tanta suavidad […]

" A nadie jamás yo dejaré

Que ande en mi cabeza más que usted "

Y con gran amor él le dijo así

Lleno de rubor:" ¡Ay sí! "»

“A chick, of those who have

long hair down to their feet,

So spoke to the hairdresser

with a little shyness:

“ I want you to do me a hairstyle Parted

in the middle, parted in half,

in a style similar to

that of Cléo de Mérode «[…]

There is no hairdresser in town who

would comb so gently […]

» In future I will not

let

anyone else touch my head except you «

And with great love he said so

blushing:» Oh yeah! ""

One of the centers of gay life in Spain during the 20s and 30s was the Residencia de Estudiantes , whose roots went back deep into the Institución Libre de Enseñanza of Francisco Giner de los Ríos and Krausismo . Some of the students were homosexual, such as Federico García Lorca . Lorca belonged to the gay core of the Generación del 27 , which also included other LGBT personalities, such as Luis Cernuda , Juan Gil-Albert , Emilio Prados , Vicente Aleixandre and Rafael de León . Salvador Dalí must also be counted among this group of poets .

There was also a "Sapphic Circle" in Madrid, which served as a meeting and exchange place. Women like Carmen Conde , Victorina Durán , the journalist Irene Polo and Lucía Sánchez Saornil met there . The only one who dared publish homoerotic verse was Sánchez Saornil, although she did it under a male name, Luciano de San-Saor. In Barcelona, Ana María Sagi and Tórtola Valencia must be mentioned.

Some books on homosexuality were even published, but most were written by foreigners. Emilio García Gómez published the book Poemas arábigo-andaluces ("Arabic-Andalusian Poems") and was the first to publish the homoerotic tradition of Al-Ándalus without censorship. Donde habite el olvido ("Where oblivion may dwell", 1934), El marinero joven ("The young sailor", 1936) and Los placeres prohibidos ("The forbidden pleasures", 1936) by Luis Cernuda contain some homoerotic poems and had some response. García Lorca never published his Sonetos del amor oscuro ("Sonnets of Dark Love") and they remained hidden from the family and unpublished until 1984.

Homosexuality, while not criminal, was nonetheless despised and excluded from society, mainly from the more conservative and ultra-Catholic sections of the Church. Homophobia has also been used by the left of the political spectrum to attack the aristocracy and the church, as the books AMDG by Pérez de Ayala , Ellas y ellos o ellos y ellas by Carmen de Burgos or Las locas de postín by Álvaro Retana show . During the 19th century, forensics had turned the homosexual into a monster - a judgment that was gradually softened in the 20th century thanks to greater visibility and the gradual decline in moralizing baggage. But it was doctors who contributed most to this exclusion and rejection of homosexuals. From the turn of the century, an endocrine view of homosexuality prevailed in Spain, dividing homosexuals into "good" (chaste) and "bad". A typical statement from the 1920s reported, "por lo general la homosexualidad no se observa más que en individuos tarados desde el punto de vista psicopático o biológico" ("in general, from a psychopathic or biological point of view, homosexuality can only be found among dysfunctional individuals" ). The main proponent of this view was Gregorio Marañón ; Fairer than most, he was against the criminalization of homosexuals, but he pleaded for the concealment of homosexuality and, as such, can be described as the predecessor of "liberal homophobia". This suffocating atmosphere led some men to seek exile in Paris.

The Spanish Civil War and the Franco dictatorship (1936–1976)

On July 18, 1936, the Spanish Civil War began with the uprising of the Spanish military in Morocco against the 2nd Republic. The rebellious nationalists did not have a clear ideology, but were in any case strongly nationalist and Catholic conservative and later leaned on fascism and Nazism . There is no evidence of deliberate or organized persecution of homosexuals, although homosexuality was a risk factor that could lead to abuse, imprisonment or even murder amid the chaos of war. The best-known case is that of Federico García Lorca , who was shot dead by a Falange militia group for being a “red fagot”, as Ruiz Alonso, leader of the group that arrested Lorca, later justified the act.

Initially, the dictatorship of Franco was concerned with the persecution and elimination of any political dissidence, but this became less and less over time. This was the beginning of the general persecution of the so-called "Violetas" ("Lilas"), for which the amendment to the law for idlers and vagrants (Ley de vagos y maleantes) on July 15, 1954 was a cornerstone.

«A los homosexuales, rufianes y proxenetas, a los mendigos profesionales ya los que vivan de la mendicidad ajena, exploten menores de edad, enfermos mentales o lisiados, se les aplicarán para que cumplan todas sucesivamente, las medidas siguientes:

a) Internado en un establecimiento de trabajo o colonia agrícola. Los homosexuales sometidos a esta medida de seguridad deberán ser internados en instituciones especiales, y en todo caso, con absoluta separación de los demás.

b) Prohibición de residir en determinado lugar o territorio y obligación de declarar su domicilio.

c) Sumisión a la vigilancia de los delegados. "

"Homosexuals, pimps, professional beggars and those who live off the begging of others who exploit minors, the mentally ill or cripples are subject to the following measures, which are carried out in sequence:

a) Imprisonment in a labor camp or an agricultural colony. The homosexuals who are given these security measures must be locked up in special facilities, and in any case completely separated from the others.

b) Prohibition of residence in a certain town or area and obligation to register one's place of residence.

c) Submission to the supervision by those commissioned. "

These labor camps and agricultural colonies were real concentration camps in which prisoners had to work under inhumane conditions until they fell over from exhaustion, were often beaten up and starved to death. The agricultural colony of Tefía in Fuerteventura is famous and notorious , the living conditions of which are dealt with in the novel Viaje al centro de la infamia (2006; Journey to the Center of Shame) by Miguel Ángel Sosa Machín. The church and the medical profession became accomplices of the regime in destroying all places of self-respect for homosexuals.

Despite everything, a gay subculture gradually emerged in the sixties, mainly in the big cities, initially in the underground and in the tourist areas where society was less conservative, such as in Barcelona , Ibiza , Sitges or Torremolinos .

In 1970 the law on dangerousness and social rehabilitation ("Ley de Peligrosidad y Rehabilitación Social") was passed, which, unlike the previous one, aimed at the "treatment" and "cure" of homosexuality. Two prisons were designated, one in Badajoz , where the "passive" gays were collected, and one in Huelva , to which the "active" gays were deported. In addition, there were special areas for homosexuals in certain prisons. In these institutions, the sexual orientation of the inmates should be transformed by aversion therapy ( electric shocks ). A total of 5,000 men and trans women were arrested across Spain for gay behavior during the dictatorship. Those arrested and imprisoned were not included in either the November 25, 1975 pardon or the July 31, 1976 amnesty.