History of piracy

The History of Piracy deals with the historical development of piracy , including the biographies of people who influenced the piracy of their time.

Because of the intertwining of piracy with sea trade and naval warfare , the history of piracy must always be seen in a geopolitical context, so that a strictly chronological representation is not possible.

In the Mediterranean

In ancient times, the sea trade routes were basically dependent on the respective rulers on the coasts of the transit areas and, like the coastal countries themselves, were endangered by robbery and war , so that they had to be secured by the seafarers' own measures.

In the eastern Mediterranean , ancient piracy was favored by the coastline, as it offered a multitude of places of refuge with numerous islands, foothills and bays. Egyptian records from the 14th century BC. BC document attacks by the Lukka on Cyprus. These pirates came from the south coast of Asia Minor , today's south-west Turkey, probably from Lycia . In many later ancient sources, this region was also considered the home of pirates who made large parts of the eastern Mediterranean unsafe. In the 13th century auxiliary troops from the Lukka countries fought on the side of the Hittites in the battle of Qadeš (approx. 1274 BC) against Egypt . Around 1200 BC BC warriors from the Lukka countries probably take part in the so-called "sea peoples" attacks on Egypt, especially in the Libyan war under Merenptah .

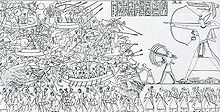

The Sea Peoples of Egypt

In popular presentations of the subject, the so-called Sea Peoples Storm is often mentioned as one of the first known highlights of piracy. A relief in the temple of Medinet Habu ( Thebes ) and the Harris I papyrus from the time of Ramses III. at least report that peoples mainly operating at sea had come together in a coalition and destroyed cities and empires in the eastern Mediterranean . The destruction around and shortly after 1200 BC, proven in large parts of this area. Are often associated with this "sea peoples storm", for example in Ugarit . Cyprus was beset by robbers (presumably coming from the Aegean or Asia Minor) for about 200 years . The classification of these events as purely predatory piracy, warlike undertakings or even migration of peoples is largely unclear.

In a combined sea and land battle in the Nile Delta succeeded Ramses III. 1186 BC To beat the sea peoples decisively. Their remains were apparently settled in Palestine , where the "Peleset" tribe is associated with the biblical Philistines .

Greek antiquity

Archaic and Classical Times

In the early days, coastal pirates prevailed, who plundered coastal towns with rowboats and uncovered galleys and attacked ships moving or resting near the coast when the opportunity was favorable. Only with the development of the trireme in the 6th century BC It became technically possible to track other ships effectively and to pursue piracy at sea in a sustainable manner.

In the saga of the Argonauts, and especially in the Homeric epics, there are still mythical echoes of early raids at sea. Especially in the so-called Homeric society , pirate-like raids from the sea seem to be nothing unusual. In the Odyssey , for example, it is described that a young Sidonian king's daughter was stolen by seafarers Taphi and led into slavery, who later helped Eumaius as wet nurse , that he was kidnapped as a child by Phoenician sailors and sold to Laertes . Odysseus himself attacked the Kikonen and claims in one of his lies that he sailed from Crete with five ships to Egypt to plunder there. Thucydides assumes that Greece was in a permanent state of war before the Trojan War , which included the sea area. In order to achieve a certain protection, cities were usually built some distance from the sea. Some pirates also worked with the coastal population who exercised the beach right. The rampant piracy was - according to Herodotus and Thucydides - first successfully fought by the Cretans under their king Minos . After the conquest of Crete by the Greeks, Crete itself became an important pirate base.

Piracy was not seen as a disreputable business, but was seen as an honorable way of increasing one's wealth. Only in later sources does piracy appear as a concept of negative valuation. In the 6th and 5th centuries BC BC the Athens Polis took action against pirate bases on Limnos , Kythnos , Mykonos and the Sporades .

Phocaeans and Etruscans in the western Mediterranean

In the western Mediterranean, the Greek Phocaeans from Asia Minor developed into a veritable sea location. The Persian expansion drove them out of Asia Minor and settled in Alalia on Corsica . From here they disrupted the trade of the Etruscans and Carthaginians as pirates and through raids on the Italian mainland. On the other hand, “Tyrrhener”, the Greek word for Etruscans, became almost a synonym for pirate among the Greeks. In a joint action, the Carthaginians and Etruscans defeated around 540 BC. The Phokaier in a sea battle and forced them to give up their settlements. With this defeat, the expansion of the Greeks in the western Mediterranean ended. The Etruscans and the great power Carthage were from then on allies. Before that, the Etruscans had also often captured Carthaginian ships.

On illustrations from the 8th century BC From Phoenician ships there are already galleys with two rows of oars one above the other, the fast biremes . Since the 5th century BC Even larger galleys with three rows of oars developed from large biremans. This Triremes or triremes were often equipped with a battering ram and used as warships. Pirates, who were not interested in ramming and sinking their prey, still preferred more agile and faster biremes with large square sails , some of which could be oars removed, which made boarding easier.

Hellenistic period

Piracy experienced another high point in the period from the Persian Wars to the middle of the 2nd century BC. While at the end of the 4th century BC From Rhodes - where one of the largest slave markets of antiquity was located - it was still possible to successfully take action against the pirates, other cities were no longer able to ensure the safety of their sea routes due to the almost permanent state of war. It was particularly problematic that the pirates often allied themselves with the warring parties. The Aitolian Bund , which was founded in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, supported Central Greece ruled, piracy against other Greek and Persian states. The toleration of piracy thus contradicted the desire of the established powers for safe sea routes. 192 BC The Aetolian League was subjugated by the Romans, after which most of the pirates fled to Cilicia . On Crete the pirates were there in the 2nd century BC. On the other hand, ousted by Cilician pirates. In the literature of the time there are often reports of people killed, abducted and sold by pirates.

Roman Empire

The Illyrians in the Adriatic

In the course of their expansion in the 3rd century BC BC out of Italy, the Romans were also confronted with piracy. First they had to fight Illyrian pirates in the Adriatic until they invaded the region in 168 BC. Annexed. Only in Dalmatia could a small refuge for Illyrian pirates survive until 9 AD. The Liburna of the Illyrian pirates became the standard ship of the Roman police watch fleet. A further development of this is the dromone (runner). In 122 BC BC the Romans waged a war against the pirates in the Balearic Islands .

The Cilikians from Asia Minor

Attempts to stop the Cilician piracy in the eastern Mediterranean, however, showed no lasting success, as the action under Marcus Antonius Orator 102 BC. In Cilicia , or failed completely, as under Mark Antony Creticus in 74 BC. In Crete. It also played a role that the Roman governors of the province of Asia and the citizens of Miletus , Ephesus and Smyrna themselves liked to do business with the pirates. B. covered their need for slaves with the Cilician pirates. During the fall of the Seleucid Empire and the wars of Mithridates , the Cilician pirates became more and more powerful. Their center became Delos , from where they brought the slave trade in the eastern Mediterranean under their control and in 86 BC. BC defeated a Roman squadron off Brindisi in southern Italy. In 75 BC During a study trip to the island of Pharmakussa , south of Miletus, the young Gaius Iulius Caesar was captured by pirates. After he was released for a ransom, he fought the pirates there.

67 BC The pirates not only massively disrupted Rome's grain supply , but also raided several Italian cities as a sign of their power. In response to this, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus was endowed with extraordinary powers ( Imperium ) by a law ( Lex Gabinia ) in the same year and - unlike his predecessors - was able to restore the safety of the sea routes within a few weeks. Pompey developed his own strategy : he divided the Roman fleet into many small groups, which he had positioned in the Mediterranean in order to block all pirate ports at the same time. Then it was left to the army to attack and destroy the hideouts from land. Mobile reserve fleets chased the remaining pirates at sea and prevented them from merging with other groups. The last base of the Cilician pirates in today's Alanya (formerly Korakesion, Rabenhorst ), in Pamphylia , where the pirate chief Diodotos Tryphon had built a fortress, was finally defeated by Pompey. The piracy could not be completely eradicated, but the widely ramified and complex organizational structures of the pirate groups could be permanently smashed.

Several Cilician pirates, whom Pompey had captured during his campaign and taken over among his clientele, later served as fleet leaders in Sicily under his son Sextus Pompeius . The admirals Menodoros , Menekrates, Demochares and Apollophanes are known by name. From 42 BC They blocked the coasts of Italy with their squadrons in order to successfully cut off the grain supply to Octavian, who later became Emperor Augustus . After numerous battles, they were only discovered in 36 BC. Defeated by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa in the naval battle of Naulochoi .

After Octavian's final victory over his last rival, Marcus Antonius, in the Battle of Actium , the Roman fleet ensured that organized piracy on a large scale was no longer possible during the Principate's time . The moment pirates became active, the governors of the individual provinces immediately intervened . Even so, piracy was a popular motif in contemporary literature, especially in the novel.

The vandals from North Africa

In the uncertain times of late antiquity , the raids of the vandals were to blame for the unsafe sea routes. After conquering their own empire in North Africa (Carthage), they attacked Rome with a fleet from there in 455 AD and sacked the city for two weeks. This action made the term vandalism proverbial. After a Byzantine fleet landed under Belisarius in 533, however, the vandals were largely destroyed.

middle Ages

As part of the expansion of the Islamic caliphate , attacks by Arab fleets on Christian countries increased from the 7th century onwards . The Byzantine Empire was threatened from the coasts of today's Lebanon , Sicily , Sardinia and southern Italy from the area of the exarchate of Carthage , which fell in 697 , and the Balearic Islands from the Umayyad emirate (later caliphate) Córdoba. Presumably, the still common were lateen and kindred lugsail the 8th or 9th century by Saracen pirates introduced in the Mediterranean. This made cruising against the wind easier and shortened travel times considerably.

Around the same time Croatian and Serbian pirates from Dalmatia ("Narentans") began to disrupt the Byzantine trade in oriental goods in the Adriatic , occasionally making common cause with the Arabs. It was not until the 11th and 12th centuries that the up-and-coming trading city of Venice increasingly managed to bring Istria and the Dalmatian coasts under its control. From the 12th century, major counter-attacks on the North African coast from the Norman Kingdom of Sicily , heralding the age of the Crusades .

One of the reasons for the debacle of the Fourth Crusade of 1204, in which Catholic crusader fleets raided and sacked Christian Constantinople instead of liberating Muslim-occupied Jerusalem, was that the Byzantine navy had long hired Italian seamen. In the late 12th century, however, these sailors came under suspicion of secretly sympathizing with Venice and other rival Italian states. Many of the sailors who could not be arrested therefore fled to remote bases in the Aegean and Ionian Seas and became pirates instead of defending the Byzantine capital at the crucial moment. Later the Byzantines felt compelled to ask these Italian pirates for their (dubious) help, not only in the fight against the Ottomans , who were expanding into Asia Minor , but also against their own compatriots, Venetians and Genoese . In the course of the 13th century, however, these were gradually displaced by Ottoman corsairs , who in turn threatened the coasts of Christian countries. A final group, the Catalan Company , which had founded a pirate alliance in the Athens area, eventually allied itself with the Muslim corsairs.

Modern times

The Uskoks in the Adriatic

Along the eastern Adriatic coast, the so-called Uskoks resumed the Narentan tradition in the 16th and 17th centuries and plundered Venetian ships from Senj .

With their small and agile boats they made the whole Adriatic unsafe. Their operations were directed not only against the Turks, but especially, with at least the tacit consent of the Viennese court, against Venetian ships, for example on the coast of Zadar . This gave rise to a war between Austria and the Republic of Venice in 1612 , as a result of which the Uskoks had to leave Senj. Their ships were burned and they moved to the Karlovac area and to the Kupa in 1617 .

The North African barbarians

In the 16th century, alongside the Order of Malta, the Muslim corsairs were the predominant pirates on the North African coast and the Mediterranean . The bases of the Muslim corsairs were the barbaric states of Algiers , Constantine , Tunis and Tripoli , from where they hunted the ships of Christian nations throughout the Mediterranean on behalf of the Ottoman sultan . On the other hand, they defended the North African coast against the Spanish fleets , whose urge to expand had been directed primarily to the south before the colonization of America. In return for the fact that the local governors of the Sultan, the Beys , made their ports available to the corsairs, they usually received a tenth of the booty, plus port fees. Successful corsairs were often appointed Beys themselves. Among the barbares there were also some converted Christians who hoped to make a career in the service of the Sultan, and Muslims and their descendants who were expelled from Christian states, especially from Spain (" Moriscos "). The most famous corsairs included the brothers Arudsch and Khair ad-Din Barbarossa , Murad Reis , Turgut Reis and Kilic Ali Pascha .

From North Africa, the barbarians made raids across the entire Mediterranean and the Atlantic. In doing so, they not only plundered passenger and merchant ships, but also regularly raided coastal villages and towns in order to capture slaves . This mainly affected the Christian countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea , but in 1627 even several hundred Icelanders were abducted from their home villages by Algerian pirates and later sold into slavery.

The various Christian states repeatedly and alternately concluded separate peace treaties with the barbarians, which included tribute payments . In order to be able to continue on booty voyages and coastal raids, it was therefore important for the “diplomacy” of the barbarian states never to have peace with all Christian seafaring states at the same time.

The preferred types of ships of the corsairs were small galleys with latin sails, like the agile Fusta with its shallow draft. In contrast to the warships of the north, they were only weakly equipped with guns, which were also housed in the bow and could only shoot forward. They were far superior to mere sailing ships, especially when it was calm. The rowers on the large galleys were mostly slaves or prisoners of war. The corsairs, on the other hand, had to row themselves on the smaller fists and galleons , which on the other hand had the advantage that no one had to watch out for slaves and every man on board was a fighter. In the course of the following centuries the Schebeck , which was increasingly just sailed, became increasingly popular.

The Knights of St. John or the Order of Malta

On the Christian side were the Barbary especially the fleets of Johanniter opposite. The Johanniter initially had their center on Rhodes and later, after the conquest of Rhodes in 1522, from 1530 on Malta . That is why the knights of the order have been called "Maltese" since 1530. They also ruled Tripoli until the Ottoman conquest in 1551. This order, which is in the tradition of the crusaders, offered a certain military protection against the North African corsairs, but also carried out piracy itself, and not only against Muslim countries. Since peace reigned between the Ottomans and the Venetians until 1571, the Maltese believed they were entitled to raid Venetian ships, even against the will of the Pope and Emperor . For this reason, the Maltese were also referred to by their Christian victims as corsairs, namely as "corsairs who display their crosses".

The last big catch was made by the Maltese on September 28, 1644: A fleet of six galleys conquered and plundered a Turkish convoy of ten ships near Karpathos , which was on its way to Alexandria . The most valuable ship of the Turkish convoy was a galleon of around 1,200 tons, which carried one of the main wives of the Ottoman Sultan İbrahim and her considerable treasures and her entourage. This attack was one of the reasons for the opening of the 6th Venetian Turkish War (1645–1696), which ended with the loss of Crete for Venice after the siege of Candia . Although the Maltese knights were able to keep their base until 1798, from now on they were no longer a threat.

Decline of corsairism

The piracy of the barbarian corsairs had already passed its peak in the middle of the 17th century. In the later phase they were mostly no longer interested in the cargo itself, but in extorting ransom money for ships and crews and in informal tribute payments from the nations concerned. The merchant navy of the young and militarily weak United States particularly suffered from this. At the beginning of the 19th century, these practices were largely curbed by military undertakings such as the First Barbarian War between Tripoli and the preform of the United States Navy (1801-1805) and finally ended by force with the conquest of Algeria by France around 1830.

The Greek freedom fighters

Piracy never completely disappeared in the Aegean with its countless islands. When the open uprising against the Ottoman Empire broke out on February 22, 1821 in the course of the Greek Revolution , the pirates rallied under the flag with the blue cross and raised their pirates to fight for freedom. Their starting point was the island of Hydra . Similar to the Dutch Zeegeuzen , the status of the Greek “freedom pirates ” is unclear. On the one hand, they provided the Turkish fleet with bitter and often successful battles that real pirates would never have done. On the other hand, they did not show the slightest fear of bringing up and robbing cargo ships of whatever nation in order to replenish their war chest. Under Konstantin Kanaris , Andreas Miaoulis and Jakob Tombasis , hundreds of ships supported this independence effort . They were later appointed Greek admirals, and many of their deeds were glorified as a struggle for freedom.

In the North and Baltic Sea region

Antiquity

Already in antiquity , Chauky and later Saxon robber bands made the coasts of the North Sea region unsafe. The Romans set up their own defense system consisting of fortresses on the Saxon coast . This coast did not get its name from the inhabitants, but from the looters who regularly visited the coast in their boats.

The Vikings

From the 8th century the Vikings from Scandinavia appeared as looters on all European coasts. They were first mentioned on the occasion of the looting of the Lindisfarne monastery in 793, and looting is reported over the next two centuries. While the raids were initially limited to places directly on the coast, the raids spread from around the middle of the 9th century along the river systems into the inland. Hamburg was destroyed for the first time in 845 , the then important trading center Dorestad was plundered six times between 834 and 873 alone, and Paris was also attacked several times. Vikings advanced as far as Kiev and even plundered the Mediterranean . The raids along the rivers followed the pattern that the Vikings appeared with large naval formations, set up bases on both sides of the river mouths and then carried out surprise attacks on worthwhile targets inland.

The Heimskringla by Snorri Sturluson and Skáldskaparmál contains details of how the Vikings used to hijack foreign ships. However, with the rise of royal power and the advance of Christianity, they were gradually ostracized. Most integrated themselves into the regular armies of the kings and stopped being Vikings.

Area of the Hanseatic League

In contrast to the Mediterranean area, rowed galleys in northern Europe soon went out of use after the Viking Age. All seafarers used more or less the same types of ships. For warlike and pirate purposes, the ordinary merchant ships were usually only more manned and provided with raised battle platforms at the bow and stern. One of the most important innovations in shipbuilding during the Hanseatic era was the development of the cog with stern rudder, which replaced the rudder that had been common up until then. From the 14th century it was also used in the Mediterranean area. Before the introduction of firearms and cannons , archers formed the ship artillery.

After the sinking of the island of Rungholt near the Groote Mandränke in January 1362, many of the fishermen and farmers who had become homeless got together at the so-called Wogemannsburg near Westerhever in order to earn a living by raiding small farms and small merchant ships. But the Wogemänner were defeated as early as 1370 after betrayal by Staller Owe Hering and the residents of the area.

The Likedeeler

The buccaneers and pirates who made the North and Baltic Seas unsafe from the mid-1390s onwards , because they basically shared the booty among themselves in equal parts, called themselves Likedeeler (“equal share”) . For more than 30 years they inflicted great losses on the Hanseatic sea trade . The most famous leaders were Klaus Störtebeker , Gödeke Michels , Hennig Wichmann and Magister Wigbold .

Originally they were hired in 1391 as seafaring blockade breakers , so-called "Vitalienbrüder", to maintain the food supply for the besieged Stockholm in the war between Sweden and Denmark. In addition, they were supposed to sink Danish warships in the sea war and prevent Denmark's sea trade with pirate trips. Since 1392, the island of Gotland has served them as a base of operations. In the same year they attacked Bergen , Norway. On Gotland they gradually became independent and under the slogan “God's friend and enemy of all worlds!” They developed into pirates who were feared by all. In 1398, however, the Vitalienbrüder were expelled from the island again by an attack by the Teutonic Order under Konrad von Jungingen .

After that they moved their main activity to the North Sea. They found bases above all in East Frisia , for example in the trading town of Emden and in Marienhafe . However, under pressure from the Hanseatic League, the Likedeelers had to withdraw from this base. Störtebeker was arrested at Heligoland on April 22, 1401 by an association of Hamburg peace ships under Nikolaus Schocke and Hermann Lange, both Hamburg councilors and England drivers, captured after heavy fighting and executed on the Grasbrook in Hamburg on October 20, 1401 . Gödeke Michels and Magister Wigbold were initially able to escape, but were also caught on October 20, 1401 and also executed on Grasbrook in 1402.

The piracy that started in Friesland only ended for a short time with the end of the Likedeeler. In 1430, 1431 and 1433 there were military expeditions from Bremen to Hamburg to stop piracy, in 1433 Emden was besieged, captured on July 20, 1433 and a Hamburg governor was installed in Emden. The Hamburgers did not leave Emden until 1447. At the Hanseatic Day in Bremen on May 25, 1494 a lawsuit was brought against the robbery of Frisian chiefs. The island of Borkum is also considered a pirate refuge during the Hanseatic League.

More pirate wars of the Hanseatic League

The constant restrictions on the privileges of the Hanseatic League at London's Stalhof led to the declaration of war by the Wendish and Prussian cities of the Hanseatic League against England . The naval war was waged as a pirate war and was successfully concluded for the Hanseatic League through the Peace of Utrecht (1474) by Mayor Hinrich Castorp . The ship's captain Paul Beneke from Danzig captured the galleon Saint Thomas from Florence in the English Channel . The famous winged altar of The Last Judgment by Hans Memling was captured on it.

Between 1522 and his death in 1540, the Frisian chief Balthasar von Esens in the Harlingerland practiced piracy against ships of the Hanseatic city of Bremen. After two campaigns by Count Edzard I of East Frisia in 1524 and 1525 and his successor, Count Enno II of East Frisia , he briefly lost his rule, but was able to regain it in the wake of the Geldrian feud . Since he had intensified the raids on Bremen ships from 1537, a dispute began between Bremen and the Schmalkaldic League on the one hand and Balthasar von Esens and the Duchy of Geldern, which had been allied with him for a long time, on the other. 1538 was subsequently outlawed on Balthasar imposed by Esen. Bremen took this as an opportunity to take military action against Balthasar. In 1540 the people of Bremen attacked Esens together with Maria von Jever . Balthasar died during the siege.

The water geusen in Holland

In the 16th century in Holland , the Wassergeusen were feared privateers. During the Spanish tyranny in the Netherlands, many refugees from Holland equipped privateers with which they hunted Spanish ships. Both nobles and merchants gave sums to equip the ships and shared the profits. The Wadden Islands Terschelling and Rottumeroog in particular served the water geusen as places of refuge. The English, French and German North Sea ports (especially Emden) also took them on. However, since they were without appointment, they were treated by the Spaniards as pirates until Prince Wilhelm of Orange allied with them, gave them letters of piracy and appointed Wilhelm II von der Marck as admiral of the Wassergeusen. The "resistance movement on water" received more and more support from all strata of the population.

Polar circle

In the polar seas , piracy was closely linked to seal and whaling . One of the most famous pirates was the Danish whaler Jürgen Jürgensen (1780–1845). Jürgensen used the war between England and Denmark to secure Iceland 's longed-for independence from Danish food deliveries, which were regularly intercepted by England, by forcing English food on the Icelanders, and immediately proclaimed himself King of Iceland.

In the Atlantic and in the New World

The European pirate system

Already in the Middle Ages , especially during the Hundred Years War , and in the early modern period , state-tolerated pirates went on a pirate voyage .

In the French and Mediterranean regions, they were often referred to as corsairs (Italian: corsaro ). The word buccaneering was originally a synonym for piracy and referred to free booty, only later the more or less legal pirate war. From the Dutch word vrijbuiter , however, the French flibustier , the English filibuster and the Spanish filibustero , which again denoted common pirates, arose in the Caribbean . In German, however, the term Flibustiers is often translated as privateer, which creates a certain uncertainty about the meaning of the word.

In times of war the warring parties tried not only to defeat the opposing navies, but above all to disrupt the opposing merchant shipping. In the absence of royal warships - navies in the modern sense of the word did not emerge until the 16th century - private ships were empowered to capture enemy merchant ships during the war through letters of piracy. These ships were then to be handed over to a prize court in the home ports of the privateers. After part of the booty, mostly 10–20%, had been taken to the crown or the government for the letter of piracy, the remaining booty was divided among the owners and masters of the ships. The crews usually received no wages or salaries, but were also involved in the booty. As long as only enemy ships were attacked, the raids were covered by the letter of piracy. But if your own or allied ships were attacked, which mainly happened in times of peace, the privateers were considered common pirates from this point on. Corsairs and pirates often had a similar business basis: Ships, equipment and crew were financed by private individuals, not infrequently also by stock corporations , whose share certificates guaranteed the buyer a corresponding share of the booty.

French corsairs from the time of the "Sun King" to the Republic

French cities like Saint-Malo , Dieppe , Boulogne , Dunkirk , Cherbourg , Nantes and Brest had their own “corsair heroes” or even, like the little town of Rothéneuf , an entire corsair dynasty. At the time of Louis XIV of France, the letters of marque ( Lettres de Marque ) were personally issued and signed by the king. Their owners were sworn to strictly observe international rules of war designed to prevent excesses and brutality that can be considered the forerunners of the Geneva Convention . Significant for the attitude of the "Sun King" towards the corsairs is the fact that he exercised strict controls over the shipping companies to which he loaned his officers. The shipowners had to deposit large sums of money before they sailed, which were to be used to redress injustices and damage that might have occurred outside of royal guidelines. They were supposed to protect the officers from being coerced by the financiers to do things that were incompatible with the honor of a royal naval officer. One of the outstanding corsairs of this time was René Duguay-Trouin (1673–1736).

French, Italian and Greek corsairs had the small but extremely fast and agile Lugger , Chasse-Marées , Tartanen , Navicellos and Sakolevas built, which were still widespread in the Mediterranean until the beginning of the 20th century.

The Spanish silver fleet

The discovery, colonization and exploitation of the New World , especially by the Spaniards, has also attracted large numbers of pirates. The rivalry between the Spaniards, the English, the French and the Dutch was also fought through political support for piracy.

Raids by French privateers

The European courts soon learned of the riches of the New World from French corsairs who crossed in front of European ports. Jean Florin or Fleury , who was in the service of Jean Ango, Viscount of Dieppe , sighted three Spanish caravels off the south coast of Portugal in 1523. Fleury and his men captured two of them and looted three large boxes of gold bars, 500 pounds of gold dust, 680 pounds of pearls , as well as emeralds and topazes . Thereupon the French King Francis I issued letters of invasion to hunt down Spanish treasure ships.

The ships of the Spaniards had to cross the Caribbean with its many small and large islands, which were ideal as bases for pirates, to transport the goods from South America. The gold and silver transports by the Spanish silver fleet (flota), which transported the yield from the high-yield silver mines every year, were just the most spectacular way to gain prey. Tobacco , sugar cane , cocoa , spices and cotton were also lucrative commodities. The first was François Le Clerc , a Huguenot , called Jambe de Bois because of a wooden leg . With three of the king's ships and several corsairs, he hijacked ships belonging to Spanish merchants and in 1554 attacked the largest settlement at the time, Santiago de Cuba , and Havana the following year , together with Jacques de Sores. When the ransom money demanded was not paid there, he burned the settlement and all the ships in the port . Once in France, the persecution had begun by Huguenots, founded displaced Protestants in 1564 the colony Fort Caroline near the present-day St. Augustine in Florida , organized by where they pirate attacks on Spanish ships and ports. But just a year later, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés captured the fort and had all Protestants executed without exception.

Ambushes by English privateers

The next to challenge the Spanish for the riches of the New World were the English. The English Queen Elizabeth I in particular supported the piracy against the Spaniards, sometimes even during official peacetime. The most famous of them is Francis Drake . Especially on his second pirate voyage, he captured enormous wealth, including valuable ship prizes , such as the treasure ship Nuestra Señora de la Conceptión , which was called Cacafuego because of its armament . His attack on the mule track with silver near Panama failed, however. After Drake's successful raids on coastal towns, the Spanish built numerous fortifications. Examples are the fortifications on San Juan de Ulúa to defend the port of Veracruz , as well as the Fort San Felipe in Cartagena .

On behalf of Drake, John Hawkins and Martin Frobisher , English shipbuilders developed the type of Elizabethan galleon , which was faster and more manoeuvrable than the carracks , galeas and large caravels of the Spaniards. They were better armored and provided a quieter platform for the guns. This type of ship remained trend-setting for almost two centuries. In contrast, the pirates in the Caribbean preferred the even smaller Bermuda sloop .

Raids by the Dutch West India Company

Although the system of the treasure fleets had been in decline since the beginning of the 17th century - the enormous quantities of imported silver had led to a general decline in prices - the Dutch West India Company was founded in 1621 with the business purpose of raiding the Spanish silver fleet, among other things . In its founding charter, it even specifically stipulated that a peace with Spain should be counteracted so that robbery raids could be carried out. In 1628 the Dutchman Piet Pieterszoon Heyn managed a large pirate attack against the silver fleet, and in 1702 an Anglo-Dutch fleet was successful in the sea battle at Vigo . The annual transports were finally stopped around 1740. Nevertheless, the Spanish silver fleet represents one of the most successful naval operations in history and was of almost existential importance for the mother country at the time, as the Spanish crown waged costly wars without developing the domestic economy sustainably.

Central America / Caribbean

The buccaneers

The expression buccaneers - from the French boucanier - originally referred to the mostly French hunters of the Hispaniola forests, who hunted feral cattle or pigs above all. Then they smoked the meat, using a method that still came from the indigenous people, on the eponymous “boucan” ovens and sold it together with the hides.

In their free time they often attacked Spanish ships passing by on the nearby coast and, because of their excellent shooting skills, were often used as auxiliary troops for the north-western European sea powers. The term later became another synonym for 17th century Caribbean pirates. The Île de la Tortue (Tortuga), north of Hispaniola, was chosen mainly by French pirates as a base. The protected natural harbor and the only weak French sovereignty over the island offered good protection against the attack of the Spaniards. Tortuga is also conveniently located on the Windward Passage between Cuba and Hispaniola, which was used by many merchant ships. From 1655 was Port Royal in Jamaica for the second base primarily English privateers.

The "Brotherhood of the Coast"

Around 1640, the international buccaneer's commune , made up of escaped engagés (contract workers ), religious refugees and hunters, became the so-called frères de la côte , brethren of the coast , or fraternity of freelance traders on Saint Domingue . Even if this union is often referred to as the “Republic of the Pirates”, we should not imagine an organized community with permanent institutions. Rather, this "brotherhood" was characterized primarily by a common lifestyle and social customs.

Over the years the buccaneers developed a common lifestyle. Particularly typical was the so-called matelotage , a partnership not dissimilar to marriage, which buccaneers entered into with each other ( s'amateloter ) and thus had a right to the partner's inheritance, among other things. It is precisely this custom that has led to countless controversies and has been repeatedly referred to in recent historiography as a form of homosexuality. But if you disregard the fact that homosexuality was certainly common among buccaneers due to an acute shortage of women, similar to that of seafarers, there is no evidence that the matelotage has explicitly homosexual backgrounds. Rather, it included a division of tasks between the buccaneers, one of whom usually stayed with the camp or went on a pirate journey and the other went hunting.

Well-known buccaneers

Perhaps the most famous buccaneer is Henry Morgan , who was even governor of Jamaica for some time . During his raids with large pirate fleets on the rich Spanish cities such as Portobelo (1668), Maracaibo and Gibraltar on Lake Maracaibo (1669), and especially on Panama (1671), he made use of the fact that their fortifications were exclusively oriented towards the sea . After the buccaneers went ashore elsewhere, they attacked the cities from the unprotected land side. The French buccaneer François l'Ollonais (actually 'Ollonois) was notorious for his cruelty against the Spaniards. Some buccaneers were known for their erudition and anti-feudal attitudes. The hydrograph and zoologist William Dampier (1651-1715) z. In the course of his extremely eventful career, B. also attacked cities on the Pacific coast of South America. His extensive geographical and zoological records, u. a. in the Galapagos Islands , however, Charles Darwin served as a rich source.

When England made peace with Spain in 1689, the era of buccaneers came to an end. (The so-called baymen on the coast of Belize had given up buccaneering as early as 1670.) Some buccaneers settled on the islands, while others had switched from buccaneer to open piracy for some time. After Port Royal was destroyed by an earthquake and subsequent tidal wave in 1692 , the pirates moved to the Bahamas Islands (until 1718) and North American ports such as New York .

Spanish countermeasures

The Spanish military system in the American colonies was initially based on the feudal principle of the encomiendas . First, conquistadors were assigned native labor and a specific area for exploitation (the encomienda ), later this was reduced to the right to levy taxes. In return, the owner of the encomienda was obliged to contribute to the defense of the respective province with horses and weapons. The reason for this system was that maintaining a standing army seemed too costly to the Spanish authorities. Despite some modifications and weakening, the system remained in place until the encomiendas were abolished on July 12, 1720. The military operations of the owners of the encomiendas were Indian uprisings and the defense against pirates.

Because of the pirate attacks, regulations gradually passed that every free man had to practice the use of weapons. The first such order was dated 1540 and concerned Santo Domingo , in the coastal areas the militia system based on it became a constant practice. The entertainment of permanent salaried associations did not arise until the 18th century (see also: Islands above the wind , islands below the wind ).

British countermeasures

In 1536 a law was passed in England regulating the punishment for piracy. The law remained in force until 1700. The Grand Admiral's jurisdiction was then responsible for all acts of piracy on the high seas, in ports and on rivers. The governors of the colonies therefore had to have all pirates brought to London , where the criminal proceedings then took place. The competent court ( Old Bailey ) was composed of an admiral and the judge appointed by the Lord Chancellor .

The convicted pirates were executed at the Execution Dock on the Thames . The gallows for the execution of pirates were erected on the bank near the low water mark . The bodies of the hanged were usually exposed to the flood three times. Convicted pirates were hanged below the flood mark as an expression of having committed their crimes within the jurisdiction of the Lord Admiral.

Greater practicality was achieved with the More Effective Suppression of Piracy Act of 1700. After 1700 pirates no longer had to be transferred to London for trial. This law enabled pirates to be sentenced to death overseas as well. Now the execution should also take place on the coast or in its immediate vicinity. Seafarers who had defended themselves against pirates were to be rewarded with a share of the shipload saved in this way. Another measure to curb piracy was to pardon pirates who were still at large. In a decree (1714) from King George I , for example, pirates can count on His most gracious forgiveness within a certain period of time . Many took advantage of this amnesty . After that, the euphemistically called golden age of piracy, there was, however, increased to mass executions of entire pirate crews, while it had been common until the end of the 17th century to execute only the leader.

From around 1702 the presence of English warships also increased. Previously there had only been a fleet of four ships in the Caribbean; this could hardly monitor the entire sea area with hundreds of islands that were not adequately mapped . Furthermore, the fleets were repeatedly weakened by diseases such as malaria , dysentery and yellow fever . It is estimated that one in three white crew members died within the first four months. The expedition against pirates carried out by Admiral Francis Hosier in 1726 was so lossy that it frightened generations of sailors. Hosier lost 4,000 of 4,750 men to fever in two years. Still, by around 1730, most of the notorious pirates were either captured or executed.

North America

In addition to the trade routes, the weather also played a large role in the activities of the pirates. In New England it can be quite inhospitable, especially in winter, the harbors could freeze over, which then meant weeks of berthing for the ships. For this reason, the pirates mostly overwintered in warmer climes and only sailed north again in April or May. For example: Blackbeard is known to have operated on the Virginia coast in October 1717 ; in June 1718 he blocked the port of Charleston in South Carolina with his fleet and the flagship, the Queen Anne's Revenge , and in the winter months he made the south unsafe and pillaged ships off the coast of St. Kitts and in the Gulf of Honduras .

During the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) up to 500 American pirates drove against England, who sunk or raised about 13 percent of their sea trade, while the official American Navy could do little against the Royal Navy . Buccaneers like John Paul Jones are still national heroes for Americans today, even though they were just vulgar pirates to the British at the time. In the so-called "Second War of Independence" (1812–1814) between the United States and Great Britain , which was fought almost exclusively at sea, the North Americans initially repeated the pirate tactic with great success. Because of their speed, the privateers and blockade breakers liked to use small mail ships, the so-called Baltimore clippers . The famous tea clipper later developed from these . However, after Napoleon Bonaparte's surrender in 1814, Britain was able to turn its full attention back to America. With a successful trade blockade, the British also removed the basis for piracy.

During the Civil War of 1861–1865, the pirate war flared up again. Most of the privateers in the Confederate South were built in officially neutral Great Britain. This would have been accepted internationally if Confederate officers like Raphael Semmes had not operated partly from British ports. With the Alabama he had taken action against the northern states with great success and had already hijacked 60 merchants before he was sunk by the Kearsarge on June 19, 1864 .

Then something happened that England, undisputedly the greatest sea power , had not thought possible: England was ordered by the international arbitration tribunal in Geneva to compensate the United States for the $ 15 million damage caused by Semmes.

This judgment showed that it was important for the European states to get serious about eradicating piracy and piracy. Under these circumstances it had become pointless to build and equip privateer ships and to entrust naval warfare to private individuals.

South America

Around 1815, the South Americans began their struggle for liberation from Spanish supremacy. Only Cuba, shaken by guerrilla fighting, remained under Spanish control, with the Spanish governors also making common cause with pirates. The revolutionary governments, however, tried everything to harm the Spaniards. Since they did not have a fleet, they issued letters of piracy, even for ships that did not have a single South American on board. The letters of piracy of the South American revolutionary governments represented only a slim chance for these pirates to escape the gallows . They not only hijacked ships of the Spaniards, but everything they came across, and enjoyed the reputation of going over corpses even for small booty. It was primarily the North Americans, English and French who took up the fight against these pirates, and it was not until 1826 that they got the situation somewhat under control. At that time Mexico , Peru and Chile had fought for independence. Simón Bolívar liberated the area of Greater Colombia , later Venezuela , Colombia and Ecuador . The last pirates to be executed in the United States in 1835 were Pedro Gibert and three of his comrades who tried to burn a North American ship with the crew trapped below on Florida Strait.

Indian Ocean and its tributaries

Long before European traders first arrived at the end of the 15th century, piracy was practiced in the Indian Ocean, especially on the monsoon- dependent trade routes between India and Arabia. When the buccaneers were ousted from the Caribbean towards the end of the 17th century and looked for new hunting grounds, the Indian Mughal Empire was in a phase of internal conflict and was no longer able to effectively protect its sea trade routes.

Madagascar and Mauritius

Between 1680 and 1720 Madagascar became a base for pirates from all over the world. The island was only sparsely populated, but provided numerous well-protected anchorages, safe inland retreats and sufficient game. Well-known pirates such as William Kidd , Henry Every , John Bowen , La Buse and Thomas Tew made Antongil Bay and the small island of Sainte Marie (Nosy Boraha), 15 km off the northeast coast of Madagascar, their base. From here they robbed the merchant ships of the East India Companies commissioned by France, England and the Netherlands in the Indian Ocean , the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf , with their silk, porcelain, spice and jewelery freight. Ships going in the opposite direction to India were attacked because of their cargo of cloth, manufactured goods and coins. The pirates' targets were also the Indian cargo ships sailing between the ports of the Indian Ocean and the pilgrim fleet sailing between Surat in India and Mocha at the tip of the Arabian Peninsula, because the wealthy Muslim pilgrims to Mecca often carried jewels and other gems with them.

As early as 1705, the British government took action against the pirates in Madagascar. Merchant ships were grouped into convoys, and British warships patrolled the main pirate ports. When the Dutch left the island of Mauritius for South Africa around 1710 , many pirates from Madagascar fled there or joined the Indian pirates in the Gulf of Khambhat . The trading power France intervened in 1715 and drove out the well-organized piracy of Mauritius.

Gulf of Khambhat

When in the first half of the 18th century the Hindu Marathas contested the rule of the Muslim Mughal princes in western India , an African Muslim named Kanhoji Angria managed to bring a stretch of coast south of Mumbai under his control and into a small but to transform practically independent pirate empire with hundreds of ships. In its coastal fortresses and on some offshore islands, not only Indian but also European adventurers gathered, who particularly attacked the merchant ships of the East India companies. Finally, the East India Company, which had its headquarters in Bombay, was forced to pay protection money in order to be able to leave the port unmolested. During this time Angria limited its raids on Indian ships. In 1712 and 1717 several attempts by the British governors to take the pirate fortresses off Bombay failed. After Kahonji's death in 1729, his sons Sumbahji and Mannaji took control of the pirates, after 1743 Sumbahji's half-brother Tulaji. It was not until the 1750s that the British allied with the Marathas League and conquered one pirate fortress after another in combined land and sea attacks. In 1756 the ancestral seat of the Angrias fell and the pirate fleet was destroyed.

Persian Gulf

From 1747 the Bedouin tribes Qawasim and Banu Yas settled on the south coast of the Persian Gulf in what is now the United Arab Emirates . Mainly from the ports of Sharjah and Ra's al-Khaimah they attacked the merchant shipping with their dhows , which is why this area was also known as the " pirate coast " or "pirate coast ". Along with the slave trade, piracy became the region's main source of income during this period. The pirates benefited from the fact that the many islands, sandbanks and coral reefs off the coast made the waters difficult to navigate and therefore offered good protection. Around 1780 the pirates from Qawasim ruled large parts of the Persian south coast and impaired Oman's trade considerably. Attempts to master Oman's piracy were initially unsuccessful, only through the intervention of Great Britain could the area be occupied and finally pacified between 1806 and 1820. In 1853, the emirs of the pirate coast undertook against military protection by the British not only to refrain from the slave trade and piracy, but to take active action against them. The most important economic basis was now pearl fishing and, from the 1960s, oil production .

In East Asia and Southeast Asia

In the relatively poor fishing villages, especially on the south-east Chinese coast, there was a form of part-time piracy for centuries. The fishermen living there could not fish all year round, especially not in the summer months. These fishermen therefore used the fishing boats in the summer months to drive north armed with knives and spears, to raid coastal towns and ships and to extort ransom for prisoners and hijacked ships. The respective pirate captains were the owners of the boats, the crew consisted mostly of friends and relatives of the owners. After the pirates' voyages, these pirates returned to their villages and started fishing again. In some cases, this type of piracy could reach a considerable extent, but never become a serious problem itself. However, teams of Asian pirate groups were recruited from the southern Chinese fishing villages, which in turn became problematic.

The wokou

The Wokou ( Chinese : 倭寇; Japanese pronunciation : wakō ; Korean pronunciation : 왜구 waegu , with the approximate meaning: "Japanese bandit weights") were pirates who attacked the coasts of China and Korea from the 13th century . They consisted to a large extent of Japanese soldiers, rons , and traders - later also of Chinese bandits and smugglers.

The early phase of the Wokou's activities began in the 13th century and extended into the second half of the 14th century. Japanese pirates concentrated on the Korean peninsula and spread across the Yellow Sea to China. The second phase was in the early to mid-16th century. During this time the composition and leadership of the Wokou changed considerably. During their heyday in the 1550s, they operated in the seas of East Asia and even sailed up river systems such as the Yangtze . The junk and the turtle ship were the preferred ship types of the Wokou.

Piracy at the transition from the Ming to the Qing dynasty

In addition to the time of Wokou in the 13th century, the transition period between the Chinese applies Ming Dynasty and that of the people of the Manchu worn Qing Dynasty as a golden age of Chinese piracy. It was shaped by members of the Zheng family, starting with Zheng Zhilong , who initially worked as a merchant in Macau and Manila and joined pirates in 1624. He attacked Chinese and Dutch ships and developed into a serious threat to the weakened Ming government, as he had a large number of junks and eventually went on to extort protection against other merchants.

The rulers of the Ming dynasty paid him substantial sums of money and in 1628 persuaded him to help the government fight piracy. He achieved military honors and received a title of nobility. However, when the Ming government asked him to leave his bases on the coast in order to help them defend against the Manchu inland, he refused and allied himself with the new Manchurian Qing dynasty. In contrast, his son Zheng Chenggong - better known as Koxinga - fought long battles with the Qing dynasty, during which, among other things, he temporarily blocked the mouth of the Yangtze . Between around 1650 and 1660 he represented the strongest power factor in the sea area between the Yangtze and Mekong Delta . Around 1655 he had 100,000 to 170,000 men in Fujian Province , who were commanded by former Ming officers. With these forces he attacked Nanjing , but was severely beaten there in 1659. He could be in the coastal city of Xiamen initially hold, retired in 1661 but with 25,000 men on 900 ships to Taiwan , where he, the Dutch sales. With his death in 1662, the era of the Zheng family ended.

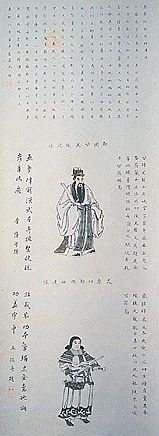

Zheng Qi and Zheng Yisao

When, towards the end of the 18th century, the Lê dynasty in Vietnam was overthrown by the Tay-Son rebellion that broke out in 1765 and civil war broke out, the Tay-Son tried to hire pirates from the southern Chinese fishing villages from around 1792, to consolidate their power. Zheng Qi , who had already entered their service in 1786, had sufficient experience as a former bandit leader and pirate to organize a pirate fleet. When the Tay-Son came under increasing pressure in the fight against Nguyn Phúc Ánh , who was supported by the French , Zheng Qi had to flee Vietnam in 1801. In 1802 he tried to support the Tay-Son with a fleet of 200 junks, but was defeated. Then there was bitter fighting among the pirates, until 1805 Zheng Yi , a cousin of Zheng Qi, was able to persuade the pirate leaders of the entire Guangdong province to come to a treaty in which they merged under his command. There were six fleets, the largest comprising about 300 junks and 40,000 pirates and the smallest about 70 junks. In contrast to other pirate organizations, this pirate organization was strictly hierarchical. The fleets were reorganized into squadrons of up to 36 ships each with 1,500 crew members. The system of loot distribution was interesting - only a fifth received the ship that had taken the loot, the rest was transferred to its own warehouses, recycled and distributed to all members. This resulted in a considerable cohesion of the organization.

Zheng Yi died on November 16, 1807. He was succeeded by his wife Zheng Yisao and Zheng Yi's foster son, Zhang Baozai, who was later to marry Zheng Yisao. Zheng Yisao instituted a code of conduct that was severely punished if ignored. She was able to lead the company so far that hardly a ship could be on the Chinese coast without a certificate of protection from the pirates. The letters of protection could be purchased against payment of protection money from the pirate captains or from regular branch offices on land. At the height of power, the Pirate League comprised over 1,000 ships and comprised 150,000 pirates.

Military means failed to counteract this pirate nuisance, and even the use of European ships did not bring any resounding success. Only a comprehensive amnesty program ended this pirate alliance after it had weakened itself through internal disputes.

The decline of classic piracy

After the international outlawing of the slave trade at the beginning of the 19th century, piracy was effectively combated on the west coast of Africa and in the Persian Gulf . After the end of the Latin American Wars of Independence, pirates largely disappeared from the Caribbean in the 1820s and 30s . Since the middle of the 19th century, piracy had almost disappeared in the industrial nations of the western world. Even piracy in the China Sea was curbed after the Second Opium War in the 1860s, but it occasionally flared up again into the 1920s.

The fast, steam-powered gunboats of the colonial powers made it possible to protect the coast from wind and weather , and the network of customs controls became increasingly dense. Up until now, pirate ships had always been state-of-the-art in their construction, often ahead of it. Now they definitely lacked the means to keep pace here too, because they now needed engineers , coal stations and well-equipped shipyards to overhaul the boilers and machinery. These are requirements that no pirate group, however well organized, was able to cope with.

More historical pirates

A selection, more under category: Pirate :

- Menodorus († 35 BC), Cilician pirate, later admiral of Sextus Pompey .

- Tarkondimotos I († 31 BC), Cilician pirate, ally of Mark Antony .

- Margaritos of Brindisi (12th century), Norman pirate in the service of William II of Sicily.

- Roger de Flor (1266–1305), former Knights Templar and founder of the Catalan Company .

- Marten Pechlin (1480–1526), privateer in the service of Christian II in Scandinavian waters.

- Lin Feng († 1575), Chinese pirate and warlord in the Philippines.

- Magnus Heinason (1545–1589), Norwegian-Faroese pirate driver.

- Pierre le Grand (17th century), is considered to be one of the first French buccaneers in the Caribbean.

- Michel de Granmont (missing off Mexico in 1686), French buccaneer.

- Richard Sievers (Indian Ocean; 1660–1700), the largely unknown German pirate.

- Jean Bart (1650–1702), Flemish privateer in the service of Louis XIV.

- Robert Culliford (17th to early 18th centuries), contemporary of Captains Kidd's in the Caribbean and Indian Ocean.

- Jean Baptiste du Casse (1646–1715), French privateer and buccaneer.

- Bartholomew Roberts (1682–1722) was a notorious pirate in the Atlantic.

- Samuel Bellamy (Caribbean, Cape Cod; 1690-1717) and his crew owned the greatest pirate treasure of all time

- Benjamin Hornigold († 1719), privateer, pirate and later pirate hunter in the Caribbean.

- Edward "Ned" Low († probably 1724), English pirate in the Atlantic Ocean; is considered one of the cruelest pirates of the golden age of piracy

- Woodes Rogers (1679-1732). Also first privateer and pirate, later pirate hunter. His motto Expulsis Piratis Restituta Commercia ( German: "Pirates expelled, trade restored") remained the national motto of the Bahamas until independence in 1973.

- "Billy One-Hand" Condon , (early 18th century), pirate in the Caribbean, Atlantic and Indian Ocean.

- Jacques Cassard (1679–1740), French privateer in the War of the Spanish Succession.

- Francois Thurot (1727–1760), French privateer in the waters of the British Isles.

- Louis Michel Aury (1788–1821), pirate and privateer during the South American Wars of Independence.

- Jean Laffite (1780–1826), French privateer in the Caribbean, Mississippi Estuary and Galveston .

- Cui Apu († 1851), Chinese pirate in the South China Sea.

Famous pirates

- Jeanne de Belleville (France 14th century) - Breton noble lady, who took revenge for her on Aug. 2, 1343 on behalf of Philip VI. beheaded man, Olivier IV. de Clisson , who turned to piracy and fought France, she is the mother of Olivier V. de Clisson .

- Grace O'Malley (actually: Gráinne Ní Mháille , * 1530 on Clare Islands in the west of Ireland; † 1603, place of death unknown)

- Mary Read (Caribbean, 1690-1720)

- Anne Bonny (Caribbean, * 1700)

- Zheng Yisao also Ching Shih or Cheng I Sao , Chinese pirate (17th / 18th century)

literature

- Frank Bardelle: Privateer in the Caribbean Sea. On the emergence and social transformation of a historical fringe movement . Verlag Westfälisches Dampfboot, Münster 1986, ISBN 3-924550-20-4 (scientific work with extensive bibliography).

- Douglas Botting et al. a .: History of seafaring - adventurers of the Caribbean. Bechtermünz, Eltville am Rhein 1992, ISBN 3-86047-025-6 .

- Arne Bialuschewski: The pirate problem in the 17th and 18th centuries. In: Stephan Conermann (ed.): The Indian Ocean in historical perspective . EB-Verlag, Schenefeld / Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-930826-44-5 , pp. 245-261 (= Asia and Africa; 1).

- Angus Konstam : Atlas of the forays into the sea. Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1999, ISBN 3-8289-0736-9 . (Extensively illustrated overview from antiquity to the present day. Contrary to the title, only a few and small scheme cards.)

- David Cordingly: Pirates: Fear and Terror on the Seas . VGS Verlagsgesellschaft, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-8025-2708-9 .

- Dieter Zimmermann: Störtebeker & Co. Verlag Die Hanse, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-434-52573-4 .

- Hartmut Roder (Ed.): Pirates. The Lords of the Seven Seas . Edition Temmen, Bremen 2000, ISBN 3-86108-536-4 (catalog book for an exhibition).

- David Cordingly: Under the black flag. Legend and reality of pirate life . Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-423-30817-6 (good, introductory presentation of the private sector).

- Hartmut Roder (Ed.): Pirates. Adventure or Threat? Edition Temmen, Bremen 2002, ISBN 3-86108-785-5 (companion volume to the symposium Piracy in Past and Present. Adventure or Threat? Of the Überseemuseum Bremen on November 10/11, 2000).

- Marcus Rediker: Villains of All Nations, Atlantic Pirates in the Golden Age. Beacon Press, Boston 2004, ISBN 0-8070-5024-5 .

- Robert Bohn : The pirates. 2nd Edition. Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-48027-6 (a generally understandable introduction to the history of piracy in the Caribbean and the "Golden Age").

- Peter Linebaugh, Marcus Rediker: The Many Headed Hydra, Sailors, Slaves, Commoners and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic Beacon Press, Boston 2005, ISBN 0-8070-5007-5 .

- Daniel Heller-Roazen: The enemy of everyone. The pirate and the law . From the English by Horst Brühmann. Fischer Wissenschaft, Frankfurt am Main 2010. ISBN 978-3-10-031410-9 .

- Andreas Obenaus, Eugen Pfister, Birgit Tremml (eds.): Terror of the traders and rulers: Pirate communities in history . Mandelbaum, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-85476-403-8 .

- Volker Grieb, Sabine Todt (Ed.): Piracy from antiquity to the present . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-515-10138-7 .

- Peter Lehr: Pirates: A New History, from Vikings to Somali Raiders. Yale University Press, New Haven 2019, ISBN 978-0-300-18074-9 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Heinrich Otten : Linguistic position and dating of the Madduwatta text. , Studies on the Boǧazköy texts, volume 11, Otto Harrassowitz-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1969, p. 34.

- ↑ Frank Starke : Lukka. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 7, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01477-0 , column 505 f.

- ↑ Helke Kammerer-Grothaus: From Argonauts and pirates in antiquity. In: Hartmut Roder (Ed.): Pirates - The Lords of the Seven Seas. Edition Temmen, Bremen 2000, ISBN 3-86108-536-4 .

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 425-429

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 15, 402-484.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 9, 39-61

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 14, 192ff.

- ↑ Introduction, ( Memento of October 17, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The Path of the Turkish Invasion

- ^ Museum about the history of the Crusades and the Order of St. John and Maltese of the Ritterhausgesellschaft Bubikon

- ^ Ekkehard Eickhoff: Venice, Vienna and the Ottomans. Callway, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7667-0105-3 , p. 17 ff.

- ↑ Detlev Quintern: To the shores of Tripolis. The USA in the Mediterranean around 1800 - The myth of the US Navy. In: Hartmut Roder: Pirates - Adventure or Threat. Edition Temmen, Bremen 2000, ISBN 3-86108-785-5 .

- ↑ Maria Christina Chatzioannu, Gelina Harlaftis: Greek privateers and pirates during the Enlightenment. In: Hartmut Roder: Pirates - Adventure or threat. Edition Temmen, Bremen 2004, ISBN 3-86108-785-5 .

- ^ Matthias Springer: The Saxons. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-17-016588-7 .

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Weidter: The Viking incursions in the area of the southern North Sea. In: Hartmut Roder (Ed.): Pirates - The Lords of the Seven Seas. Edition Temmen, Bremen, 2000, ISBN 3-86108-536-4 .

- ^ Eiderstedt and the surrounding area. ( Memento from April 22, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Mats Mogren: The Vitalienbrüder and the building of castles in the northern Baltic Sea area. In: Jörgen Bracker (Hrsg.): The Hanseatic League - Reality and Myth. Volume 1, Museum for Hamburg History, Hamburg 1989, ISBN 3-7950-1275-9 , p. 627.

- ↑ Cf. on the Vitalienbrüders in general: Hartmut Roder: Klaus Störtebeker - Chief of the Vitalienbrüder. In: Hartmut Roder: Pirates - The Lords of the Seven Seas. Edition Temmen, Bremen, 2000, ISBN 3-86108-536-4 ; Mats Mogren: The Vitalienbrüder and the building of castles in the northern Baltic Sea area. In: Jörgen Bracker (Hrsg.): The Hanseatic League - Reality and Myth. Volume 1, Museum for Hamburg History, Hamburg 1989, ISBN 3-7950-1275-9 , p. 627; Püschel, Wiechmann, Bräuer: Störtebeker and the pirate skulls from Grasbrook. ( Memento of October 22, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF)

- ↑ Ute Scheurlen: Bremen and the pirates. In: Jörgen Bracker (Hrsg.): The Hanseatic League - Reality and Myth. Volume 1, Museum for Hamburg History, Hamburg 1989, ISBN 3-7950-1275-9 , p. 620; Renate Niemann: Where a number of pirates were executed in Bremen . In: Hartmut Roder: Pirates - The Lords of the Seven Seas. Edition Temmen, Bremen, ISBN 3-86108-536-4 .

- ↑ Gilles Lapouge: Pirates, pirates, privateers, buccaneers and other hunters of the seas. The Hanse / Sabine Groenewold publishers, Hamburg 2002, pp. 105–108.

- ↑ Blake D. Patt Ridge: Buccaneers and Freebooters. In: Tenenbaum: Encyclopedia. Volume 1, p. 477.

- ↑ David Cordingly: Under the Black Flag. The Romance and the Reality of Life among the Pirates. Harcourt Brace, San Diego 1997, p. XVIII.

- ↑ Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin: The pirate book of 1678. The American pirates. Edition Erdmann, Stuttgart 1983, p. 118; Clinton V. Black: Pirates of the West Indies. Cambridge Caribbean, Cambridge 1989, p. 7.

- ↑ The Proceedings of the Old Bailey London 1674 to 1834 - Famous Court and Pirate Cases (English)

- ^ Marc C. Hunter: Pirates in the Gulf of Mexico in the early 19th century. In: Hartmut Roder: Pirates - Adventure or Threat? Edition Temmen, Bremen, 2004, ISBN 3-86108-785-5 .

- ↑ Bettina v. Briskorn: A Brief History of the Pirates in Madagascar. In: Hartmut Roder (Ed.): Pirates - Adventure or Threat. Edition Temmen, Bremen 2004, ISBN 3-86108-785-5 .

- ^ History of India at that time

- ↑ Dubai . LexiTV. United Arab Emirates . ( Memento from May 27, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Meyers-online.

- ↑ a b See on piracy in the Chinese Sea Udo Allerbeck: Piraterie in China. In: Hartmut Roder (Ed.): Pirates - The Lords of the Seven Seas. Edition Temmen, Bremen 2000, ISBN 3-86108-536-4 .

- ↑ Gilles Lapouge: Pirates, pirates, privateers, buccaneers and other hunters of the seas. The Hanse / Sabine Groenewold publishers, Hamburg 2002, p. 83.

- ↑ On pirates in general: Heide vielle, pirate brides and other women. In: Hartmut Roder (Ed.): Pirates - Lords of the Seven Seas . Edition Temmen, Bremen 2000, ISBN 3-86108-536-4 .