Bavarian

| Bavarian ( Boarisch ) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

|

|

| speaker | an estimated 12 million speakers | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | - | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

gem (other Germanic languages) |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

bar |

|

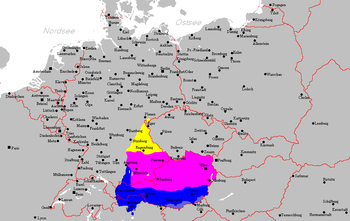

As Bavarian , often also Bavarian-Austrian (Bavarian in Bavaria : Boarisch or Bairisch ; in Austria named after places and regions, e.g. Weanarisch in Vienna or Styrian in Styria ; in South Tyrol : South Tyrolean ) is used in German linguistics due to common Linguistic features denote the south-eastern dialect group in the German-speaking area . Together with the Alemannic and East Franconian in the west, the Bavarian dialect group is one of the Upper German and thus also one of the High German dialects . With an area of around 125,000 km², the language area of the Bavarian dialects is the largest German dialect area; The Bavarian dialects are spoken here by a total of around 12 million people in the German state of Bavaria (mainly Old Bavaria ), most of the Republic of Austria (excluding Vorarlberg ) and the South Tyrol region, which belongs to Italy .

The Bavarian dialect group is classified by the International Organization for Standardization as an independent individual language (the language code according to the ISO 639-3 standard is bar ) and has been listed by UNESCO in the Atlas of Endangered Languages since 2009 . With a history going back over 1000 years to the older Bavarian tribal duchy , Bavarian is a historically developed, independent dialect association of the German language (such as Alemannic or Low German ), which, however, has never been standardized . Bavarian is not a dialect of the standard High German written language , which only developed much later as an artificial equalization language and is also a dialect of the German language. The difference between Bavarian and Standard High German is e.g. B. greater than that between Danish and Norwegian or between Czech and Slovak . The simultaneous growth of a person with dialect and standard language is considered in brain research as a variant of multilingualism , which trains cognitive skills such as concentration and memory.

Since the Bavarian-Austrian dialects are spoken in the east of the Upper German language area, they are also referred to as East Upper German . The spelling Bavarian , which describes the language area of the Bavarian-Austrian dialects, should not be confused with the spelling Bavarian or Bavarian , which refers to the territory of the State of Bavaria. Bavarian-Austrian is also not to be confused with Austrian German , which - like Federal German High German in Germany and Swiss High German in Switzerland - is the Austrian standard variety of Standard High German .

The name of the Bavarians

etymology

The word Bavarian is a dialectological term that is derived from the name of the Bavarian settlers and their tribal dialect. It must be separated from the word Bavarian, a geographical-political term that refers to the Free State of Bavaria, where non-Bavarian dialects are also common.

The origin of the name of the Bavarians is disputed. The most widespread theory is that it comes from the putative Germanic compound * Bajowarjōz (plural). This name has been passed down as Old High German Beiara , Peigira , Latinized Baiovarii . It is believed that this is an endonym . Behind the first link Baio is the ethnicon of the previous Celtic tribe of the Boier , which is also preserved in the Old High German landscape name Bēheima 'Böhmen' (Germanic * Bajohaimaz 'home of the Boier', late Latin then Boiohaemum ) and in onomastic connecting points ( Baias , Bainaib , etc.) .

The term goes back to the area of Bohemia , which owes its name to the Celtic people of the Boier . The second link -ware or -varii of the resident designation Bajuwaren comes from ancient Germanic * warjaz 'residents' (cf. Old Norse Rómverjar 'Römer', old English burhware 'city dwellers'), which belongs to defend ( ancient German * warjana- ) (cf. also Welsh gwerin 'crowd'). The name 'Baiern' is therefore interpreted as 'inhabitant of Bohemia'. A more general interpretation, which does not imply the origin from Bohemia, is that of “people of the land of Baja”.

It is believed that the Celtic people of the Boier mixed with the rest of the Roman population and immigrants and that the name passed to the entire newly formed people. The oldest written find on German soil is a pottery shard with the inscription "Baios" or "Boios" and was found in the Celtic oppidum of Manching (near Ingolstadt on the Danube). This find can also be written evidence of the Boier migration to Old Bavaria. The phonetic matches are obvious, but some scholars disagree. In science it is currently considered relatively certain that the Bavarians did not advance into the land between the Danube and the Alps in one big hike, but in individual spurts and settled this area together with the already resident Romans and Celts. There the various immigrants grew together to form these Bavarian wares, which Jordanis described in his Gothic history in 551 .

Probably the Bavarians were formed from different ethnic groups:

- from remnants of the Celtic population ( Vindeliker )

- from native Romans

- from several Elbe and East Germanic tribes (including Marcomanni , Rugier , Varisker , Quaden )

- from Alemannic, Franconian or Thuringian, Ostrogothic and Longobard ethnic groups

- from descendants of the mercenaries of the Roman border troops

In modern research there is no longer any talk of a closed immigration and land occupation of a fully trained people. It is assumed that the Bavarian tribes will be formed in their own country, i.e. the country between the Danube and the Alps.

The oldest written tradition of Bavarian is the collection of laws of the Lex Baiuvariorum from the early Middle Ages. The work, which is mainly written in Latin, contains everyday Bavarian words and fragments as a supplement.

Bavarian and Bavaria

In linguistics , the spelling Bavarian and Bavarian language area is used. In contrast, the word Bavarian does not designate any language dialects, but refers to a political territory, the Free State of Bavaria . The different spellings were introduced because on the one hand in Bavaria Franconian and Alemannic (in Franconia and Bavarian Swabia ) dialects are spoken in addition to the Bavarian (in Old Bavaria ) , on the other hand the Bavarian dialects are not limited to Bavaria, but also in Austria, South Tyrol and spoken in some isolated linguistic islands in the northern Italian province of Trentino and in a village in the Swiss canton of Graubünden ( Samnaun ). The historical spelling Baiern for the evolved Bavarian state structure was replaced by an order from October 20, 1825 by King Ludwig I with the spelling Bavaria, i.e. with the letter y .

Spread and delimitation

The Bavarian spread in the course of migration movements of people beyond today's southern Bavaria east of the Lech and in the course of the Middle Ages over today's Austria east of the Arlberg, South Tyrol and some areas in western Hungary (today's Burgenland), Italy, as well as parts of today's Slovenia and Czech Republic. During this time, parts of Bavarian (in what is now southern and eastern Austria) mixed with Slavic and Rhaeto-Romanic language elements. This becomes clear with certain place names and in some dialect expressions.

The Bavarian dialect areas are part of a dialect continuum that has developed through geographical isolation and thus the development of local communication. The southern Bavarian dialect area in Tyrol includes the areas of the old County of Tyrol, which did not include the Tyrolean Unterland and Ausserfern . Carinthia was separated from Bavaria in 976 (as was Styria in 1180) and annexed to Austria in 1335 by Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian . The situation is similar with the northern Bavarian dialects, because the balance of power has changed over time, especially in the Upper Palatinate . The mixed areas between Central and South Bavarian can be identified by belonging to the Duchy of Austria (Tiroler Unterland to Tyrol and Styria to Austria) and by hiking movements such as B. in the then diocese of Salzburg .

With more than 13 million speakers, Bavarian is the largest contiguous dialect area in the Central European language area. The Bavarian language area covers a total of 150,000 km². The dialects of the following areas belong to Bavarian :

- In the Free State of Bavaria, the administrative districts of Upper Bavaria , Lower Bavaria , Upper Palatinate , parts of Upper Franconia , parts of Middle Franconia as well as the district of Aichach-Friedberg and parts of the districts of Augsburg and Donau-Ries of the administrative district of Swabia , which make up the so-called Old Bavaria .

- The Republic of Austria with the exception of Vorarlberg and the northern part of the Tyrolean Ausserfern ( Reutte ).

- the German-speaking population of South Tyrol .

- Samnaun in the canton of Graubünden ( Switzerland )

- the southern Vogtland in Saxony , south of Tetterweinbach and Eisenbach .

- the seven municipalities , the thirteen municipalities and Lusern (see also Zimbern ), the Fersental , Sappada (Bladen), Sauris (Zahre), Timau (Tischelwang) and the Canal Valley in northern Italy, in which, because of the centuries-old isolation of the localities, old and Middle High German elements of Bavarian have received several local variants.

- the dialects of the German-speaking population in southern and western Bohemia , southern Moravia and the Egerland

- the dialects of the German-speaking population in western Hungary

- the Romanian Landler villages in Transylvania ( Großpold , Grossau , Neppendorf ), some villages in the Banat (e.g. Wolfsberg ) and the so-called Zipser settlements in Oberwischau in Maramuresch and Kirlibaba in Bukovina .

- some villages in the western Ukrainian Oblast of Transcarpathia : Deutsch-Mokra (Німецька Мокра), Königsfeld (Усть-Чорна), Kobalewetz (Кобилецька Поляна), Bardhaus (Барбово) etc.

- in Siberia some scattered groups of Ukrainian peasants who were deported to Khanty-Mansiysk district during the Soviet era

- by the Hutterites spoken in Canada and the US German language form ( Hutterite ).

- the Brazilian Tyrolean villages Treze Tílias (Dreizehnlinden) in the state of Santa Catarina and the Colônia Tirol in Espírito Santo

- the Tyrolean village of Pozuzo in Peru

In Nuremberg room a Franco-of Bavarian dialect transition is resident which, although predominantly East Frankish has features but leaves most recognized in the vocabulary strong Bavarian influence. Many of them go back to the numerous immigrants from Upper Palatinate who found a new home in this northern Bavarian metropolis during the period of industrialization . In the Middle Ages, however, Nuremberg was directly on the Franconian-Bavarian language border.

Bavarian, along with Alemannic and East Franconian, is one of the Upper German dialects of High German .

Internal system

Bavarian can be divided into three areas - North, Central and South Bavarian - based on linguistic features. Between these there are transition rooms, which are named as North Central Bavarian ( example ) and South Central Bavarian.

Northern Bavarian

Northern Bavarian is spoken in the greater part of the Upper Palatinate , in the southeastern parts of Upper Franconia ( Sechsämterland ) and Middle Franconia , in the northernmost part of Upper Bavaria and in the southernmost part of Saxony (Südvogtland). In the south-eastern Upper Palatinate and in the northernmost part of Lower Bavaria , mixed forms of northern and central Bavarian - linguistically called northern central Bavarian - are spoken, with the city of Regensburg being a central Bavarian language island within this area.

The dialects of the Upper Palatinate and the Bavarian Forest are also called “Waidlerische”. Linguistically speaking, these are North Bavarian, North Central Bavarian and Central Bavarian dialects, with the North Bavarian elements gradually increasing towards the north.

The East Franconian dialects in eastern Middle Franconia up to and including Nuremberg show a strong northern Bavarian influence and thus mark a transition area between Bavaria and Franconia.

Northern Bavarian is an original variant of Bavarian, which still retains many archaisms that have already died out in the central Middle Bavarian language area. It has many phonetic peculiarities, some of which it shares with the neighboring East Franconian dialects. In the following, the important phonetic characteristics of North Bavarian are listed, through which it differs from Central Bavarian.

Northern Bavarian is particularly characterized by the "fallen diphthongs" (preceded by mhd. Uo, ië and üe ) and the diphthonged Middle High German long vowels â, ô, ê and œ ; For example, the standard German words brother, letter and tired ( monophthonged vowels) correspond here to Brouda, Brejf and mejd (first monophthonged, then again diphthonged ) instead of Bruada, Briaf and miad (preserved diphthongs) as in Middle Bavarian south of the Danube. Furthermore, for example, the German standard corresponds sheep here Schòuf (mittelbair. Schoof ), red here Rout / rout (mittelbair. Red / rout ), snow here Schnèj (mittelbair. Snow ), or angry here Bey (mittelbair. Bees ).

In the northern and western northern Bavarian dialects, these diphthongs are also preserved before the vocalized r and thus form triphthongs, for example in Jòua, Òua, Schnoua, umkèjan, Beja, what southern and central Bavarian Jåår, Oor, Schnuòua, umkeern, Biia and standard German Year, ear, cord, reverse, beer equals.

In the dialects in the west and north-west of the northern Bavarian language area, a characteristic elevation of the vowels e (and ö after rounding) and o to i and u is recorded, for example Vuugl and Viigl, in contrast to the more southern forms Voogl and Veegl for standard language Bird and birds. Incidentally, this elevation is also considered a characteristic (East) Franconian feature. In the northeast of the language area these sounds are the diphthongs , among others , and in general, so Vuagl and Viagl.

Unlike in Middle Bavarian (and similar to neighboring Franconian dialects), L after vowel is not or not completely voweled, but remains as a semi-consonant / semi-vowel, with some of the vowels (especially e and i ) in front of it changing (e.g. correspond to North Bavarian Wòld, Göld, vül / vul, Hulz / Holz, Middle Bavarian Wòid, Gèid / Gööd, vui / vèi / vüü, Hoiz and in the standard language Wald, Geld, viel, Holz ).

G is (in contrast to Middle Bavarian and South Bavarian) inwardly and outwardly softened in certain sound environments to ch ( spirantization ). That is standard German way here Weech, lean here moocher, right here richtich (not provided to teach is sanded). In terms of linguistic history, this spiraling can be traced back to Central German influence, but it is not identical with the sound and occurrence relationships in today's Central German dialects, although it is more pronounced in the west and north of the northern Bavarian region than in the southeast.

The plural forms of diminutive and pet forms usually end in - (a) la, in the singular with - (a) l, for example Moidl = girls, d 'Moi (d) la = girls.

Verbs with double vowels such as au or ei in Northern Bavarian consistently end in -a: schaua, baua, schneia, gfreia, in contrast to the Middle Bavarian schaung, baun, schneim, gfrein (= look, build, snow, look forward ).

The ending -en after k, ch and f has been retained as a consonant in the northern northern Bavarian dialects, for example hockn, stechn, hoffn, Soifn (= soap ). In the more southern northern Bavarian dialects, as in the central Bavarian dialects further south, it has become -a , i.e. hocka, stecha, hoffa, Soifa.

The weakening of the consonants and the nasalization of vowels is common to North Bavarian and Central Bavarian. These characteristics are described in more detail in the following section on Middle Bavarian.

The form niad for Middle Bavarian net and the various forms of the personal pronoun for the 2nd person plural are also characteristic: enk, enks, ees, èts, deets, diits, diats, etc.

In terms of the special vocabulary, North Bavarian as a whole cannot be differentiated from Central Bavarian, because there are different regional distributions word for word. From language atlases one can see, however, that there are increasing similarities (apart from phonetic subtleties) between (Upper) East Franconian and North Bavarian dialects in the west and north of the North Bavarian language area, such as Erdbirn instead of Erdåpfl (= potato ), Schlòut instead of Kamin, Hetscher instead of Schnàggler (= hiccups), Gàl (= nag ) instead of Ross (= horse).

In the north-east there are also similarities with East-Central German dialects, such as Pfà (rd) (= horse ) instead of horse. Duupf / Duapf (= pot ) instead of Hofa / Hofm. In the south-east, commonalities with the “waidler” dialects, such as Schòrrinna instead of Dochrinna, Kintl / Raufång instead of Schlòut / Kamin. Examples of small-regional variants are Ruutschan and Ruutschagàl instead of Hetschan and Hetschagàl (= children's swing and rocking horse ) or Schluuder / Schlooder instead of Dopfa / Dopfm / Dopfkàs (= topfen / quark ) in the westernmost Upper Palatinate.

Middle Bavarian

Middle Bavarian is spoken in Lower Bavaria , Upper Bavaria , in the south of the Upper Palatinate , in Flachgau in Salzburg , in Upper Austria , Lower Austria and Vienna . The Tiroler Unterland , Salzburg Innergebirg (without the Flachgau), Upper Styria and Burgenland form the south-central Bavarian transition area . In the north-west there is a broad transition zone to the East Franconian and Swabian regions. Some phonetic characteristics of the Middle Bairischen, especially the diphthong / oa / for MHG. Ei (for example Stoa or stoan = "stone"), to a smaller extent, the l-vocalization, penetrate into a wedge, including the city Dinkelsbühl up across the state border to Baden-Württemberg .

It has a great influence on its sister dialects in the north and south, as almost all of the larger cities in the Bavarian language area are located in the Danube region; This also means that Central Bavarian enjoys a higher level of prestige and is well known outside of its speaking area. The regional differences along the Danube lowlands from the Lech to the Leitha are generally smaller than the differences between the various Alpine valleys in the South Bavarian region.

A general characteristic of these dialects is that Fortis sounds like p, t, k are weakened to the Lenis sounds b, d, g. Examples: Bèch, Dåg, Gnechd (“Pech, Tag, Servant”). Only k- is retained in the initial sound before the vowel as a fortis (for example in Khuá “cow”). In addition, the final -n can nasalise the preceding vowel and fall off itself, as in kôô (“can”, not even nasalized ko ) or Môô (“man”, not even nasalized Mo ). Whether or not a nasal vowel occurs varies from region to region.

Central Bavarian can still be subdivided into West Central Bavarian (also sometimes called "Old Bavarian") and East Central Bavarian. The border between these runs through Upper Austria and is gradually shifting westward towards the state border between Germany and Austria due to the strong pressure exerted by the Viennese dialect .

In Upper Austria (with the exception of the more strongly radiating city dialects in the central area and the inner Salzkammergut ), in the Salzburg outskirts (Flachgau) as well as in the linguistically conservative regions of the Lower Austrian Waldviertel and Mostviertel , as in neighboring Bavaria, the (West Central Bavarian) Old Bavarian tribal tongue is at home; the local dialects form a dialect association with the neighboring dialects of Lower Bavaria , the Danube Bavarian . Unlike the East Central Bavarian, it originated on the soil of the old tribal duchy.

The old form for “are” is also typical of West Central Bavarian: hand (“Mir hand eam inna worn” = “We found out”). “Us” often appears as “ins” and “zu” as “in” (“Da Schwåger is in's Heig'n kema” = “the brother-in-law came to make hay”). "If" is resolved with "boi" (= as soon as): "Boi da Hiabscht umi is" = "when autumn is around / over". The old Germanic temporal adverb "åft" is used next to "na" in the sense of "afterwards", "afterwards". The latter forms are now limited to rural areas.

In Upper Austria the dialect of the Innviertel and the neighboring Lower Bavarian dialect form a historical unit - politically, the Innviertel did not become Austrian until 1814. While the dialect of the Innviertel undergoes a noticeable change in sound towards the east (towards Hausruck ) ( ui becomes ü, e.g. "spuin" / "spün", increasing å-darkening), the transitions further east along the Danube are over the Traunviertel flowing towards the Mostviertel (East Central Bavarian). In addition, towards the east the influence of Viennese increases, which in recent decades has increasingly overlaid the down-to-earth dialects. This Viennese impact is most noticeable in the larger cities and along the main traffic routes.

The Eastern Austrian branch of Middle Bavarian goes back to the dialect of the Babenberg sovereign area Ostarrichi , which arose in the wake of the Bavarian eastern settlement . Eastern Central Bavarian has a Slavic substratum and a Franconian superstrat , which is reflected in the special vocabulary and some phonetic peculiarities. In addition, East Central Bavarian was enriched with many Slavic, Yiddish and Hungarian foreign words during the Habsburg Empire, which clearly sets it apart from West Central Bavarian.

In spite of the dwindling dialect in the larger cities of the Danube region, the city dialects of Munich and Vienna are still to a certain extent "prime dialects " for West and East Central Bavarian. The following phonetic signs characterize the relationship between West and East Central Bavarian:

| Isogloss | western variant | eastern variant | Standard German |

|---|---|---|---|

| ui vs. üü (<ahd. il ): | vui Schbui, schbuin i wui, mia woin |

vüü Schbüü, schbüün i wüü, mia wöön / woin |

a lot of game, I want to play, we want to |

| å vs. oa (<ahd. ar ): | i få, mia fåma håt, heata Gfå, gfâli |

i foa, mia foan hoat, heata Gfoa, gfeali |

I drive, we drive hard, harder danger, dangerous |

| oa vs. â (<ahd. ei ): | oans, zwoa, gloa, hoaß, hoazn, dahoam, stoa |

âns, zwâ, glâ, hâß, hâzn, dahâm, Stâ |

one, two, small, hot, heating, at home, stone |

| o vs. à (<ahd. au ): | i kàf, mia kàffa (n) | i kòf, mia kòffa (n) | i buy, we buy |

| illegal: | i kimm, mia kemma (n) | i kumm, mia kumma (n) | I'm coming, we're coming |

The table is greatly simplified. In the western variant, the “r” is often spoken, which is often vocalized in East Central Bavarian and standard German; so z. B. i får, hart, hårt, hirt.

In addition, the Viennese influence has the effect that in the East Central Bavarian dialect area there has been a tendency in the last few decades to replace the old oa with the Viennese â . However, this language change has not yet led to a clear dialect border, as even in the far east of Austria (Burgenland) the historical oa still holds against the Viennese aa, just as in large parts of Lower Austria and Upper Austria. The ancestral (Old Bavarian) word ending -a instead of -n (måcha, låcha, schicka) is also common there.

The "ui dialect" can be found on the eastern edge of the Middle Bavarian region, in the Weinviertel region and in Burgenland. Here a ui (Bruida, guit) corresponds to the common in Central and South Bavarian among others (Bruada, guat). In the Lower Austrian Weinviertel in particular, however, these variants are on the decline. This phenomenon goes back to an old Danube Bavarian form, some of which is found much further west.

In conservative dialects of old Bavaria and western Austria north and south of the Danube, ia often appears as oi when it goes back to old Upper German iu , e.g. B. as “Floing” (from bair.-mhd. Vliuge , bair.-ahd. Fliuga ) instead of “Fliang”, north bair. “Fläing” (fly) (which is adapted to the Central German representation, cf. mhd. Vliege , ahd. Flioga ); a reflex of the old Upper German iu is also preserved in the personal name Luitpold .

In Danubian (especially Eastern Austrian) dialects, o is often raised to u ( furt instead of "fort").

The "rural", the dialect that is or was spoken in the Hausruckviertel and in the western Traun and Mühlviertel has or had a certain independence . Here, instead of the East Central Bavarian long o (root, grooß, Broot = red, large, bread), the diphthong eo occurs, with the emphasis on the second part of the twilight. That results in reot, greoß, Breot. Both oo and eo are spoken very openly and could just as easily be written åå or eå . In the western Mühlviertel there are also forms with an inverted diphthong such as red, groeß, broet. However, all these forms are rarely heard today.

A typical distinguishing criterion between the Danube Bavarian (large part of Austria, Lower Bavaria and the Upper Palatinate) and the south-western group (large part of Upper Bavaria, Tyrol, Carinthia, large parts of Salzburg and the Styrian Oberennstal) is the dissolution of initial and final -an and final -on . While the double sound in the Danube-Bavarian area is pronounced predominantly as ã (Mã, ãfanga, schã = man, begin, already ), a light, partly nasal o is at home in the southwest (Mo, ofanga, scho). For example, lift for hold is characteristic of the south-western dialects , instead of the High German word lift , the word lupfen is used.

Western Upper Austria (Innviertel, Mondseeland), parts of the Salzburg region and the upper Ennstal belong to the West Central Bavarian region. Here the diphthong ui (i wui, schbuin), which is common in old Bavaria, is used . In: Lower Bavaria (and in rural areas of Upper Austria) one often encounters öi instead of ü ( vöi = a lot, schböin = to play). In parts of Upper and Lower Bavaria, ej is also widespread (vej, schbejn). In the western Salzkammergut and in Salzburg, the form schbiin is used.

Phonically, the (core) Upper Bavarian, Tyrolean and the above-mentioned transitional dialect in the Alpine region are very close. -An- appears as a light -o- (who ko, the ko) and r plus consonant is resolved consonantically (schwå r z / schwåschz instead of Danubian schwooz or schwoaz ). Similarly, in the down-to-earth dialect of the Hausruck area and other remote and traffic-free areas of Upper Austria, it is called schwåchz or Kechzn (candle), but this has recently been disappearing more and more in favor of schwoaz or Keazn .

The language border between Upper Bavarian and the “Danube Bavarian” Lower Bavarian is not identical to the borders of the two administrative districts, as Lower Bavaria was once much larger than it is today. That is why people on both sides of the Salzach, in parts of the Inn Valley and in the western Hallertau, still speak with the Lower Bavarian tongue.

The Lech forms the western border of the Bavarian and separates it from the Swabian language area. Nevertheless, people near Lech (Pfaffenhofen, Schrobenhausen, Landsberg am Lech) already speak with a Swabian touch ( I håb koa Luscht) (→ Lechrain dialect ).

Central Bavarian also includes the dialects in southern Bohemia and South Moravia, which are in danger of becoming extinct; they are similar to those in the neighboring area, but are usually more conservative. On the other hand, innovations can also be observed, e.g. B. long a instead of oa for mhd. Ei (as in Vienna and Southern Carinthia).

South Bavarian

South Bavarian is spoken in Tyrol , in the Swiss municipality of Samnaun , in South Tyrol , in Werdenfelser Land , in Carinthia , in parts of Styria (especially in western Styria ) and in the German- speaking islands of Veneto , Trentino (see Cimbrian ) and Carnia . Upper Styria, the Salzburger Alpengaue and the Tiroler Unterland belong to the transition area between southern and central Bavarian. The Zarzerian and the Gottscheerian were also southern Bavarian.

The affricate kχ , which arose in the High German sound shift from k , is secondary to the area of western southern Bavarian and high and high Alemannic. In Alemannic, the initial k has disappeared, so that the initial affricate is now a typical characteristic of Tyrolean in particular.

South Bavarian is a rather inhomogeneous linguistic landscape, but it has some characteristic features. It is divided into halfway closed language areas and numerous transitional dialects, the exact delimitation of which is almost impossible.

Probably the best known South Bavarian dialect is Tyrolean . In addition to the strong affricatization, its most prominent feature is the pronunciation of “st” in the interior of the word as “scht” (“Bisch (t) no bei Troscht?”). Here is an original distinction is maintained, since the s -sound, which was inherited from the Germanic example, in Old High German namely, sch was spoken -like, in contrast to the s -According, by the High German sound shift from Germanic * t originated. This sch -like pronunciation attests to German loanwords in West Slavic languages, e.g. B. Polish żołd (Sold). To this day, this has been preserved in the interior of the word st in the Palatinate, Alemannic, Swabian and Tyrolean languages. The sp is also pronounced in Middle Bavarian as šp , z. B. Kaspal (Kasperl). As in Middle Bavarian it is called `` scht '' (first), `` Durscht '' (thirst), because rs is pronounced as rš in almost all Bavarian dialects.

Verbs in the infinitive and plural, as in written German, always end in -n . Middle High German egg appears as "oa" ( hey , it 's 'it's hot'). The "Tyrolean" is spoken in North Tyrol (Austria) in the so-called Tyrolean Central and Oberland, in all of South Tyrol (Italy) and in a transitional variant in East Tyrol (Austria). The East Tyrolean dialect is gradually changing into Carinthian. The Werdenfels dialect around Garmisch and Mittenwald is also Tyrolean.

In the Tyrolean Oberland around Landeck , in the Arlberg area and the side valleys behind, the Alemannic influence is unmistakable. All infinitives and plurals end in -a ( verliera, stossa etc.). The majority of the Ausserfern region with the district town of Reutte already speaks an Alemannic dialect that is part of Swabian ("Tyrolean Swabian", with similarities to the dialect of the neighboring Ostallgäu).

In the Tiroler Unterland ( Kitzbühel , Kufstein , St. Johann , Kaisergebirge ) one does not speak Southern, but Central Bavarian ( l -ocalization, st inside the word ... with the exception of the tendency to affricatization, it shares all characteristics with West Central Bavarian). To the ears of “outsiders” it sounds like a harder variant of Upper Bavarian, with which it otherwise corresponds completely. The infinitives end after n-, ng- and m- on -a ( singa 'sing', kema ' to come'), otherwise on -n .

Together with the Alpine transitional dialects noted under the heading “Middle Bavarian”, the “Lower Bavarian” also shares some phonetic similarities such as the mostly subtle affricates that can be found everywhere. The dialects of the Salzburger Gebirgsgaue are all bridge dialects. The Pinzgau dialect behaves largely like that of the Tyrolean lowlands, the Pongau dialect shows Danubian influences and the Lungau dialect Carinthian influences.

The other major southern Bavarian core dialect is Carinthian . Like the East Central Bavarian, it has a compact Slavic substrate. Carinthia was in fact inhabited by Slavic tribes in the early Middle Ages and beyond; After the Bavarian conquest of the land, the Slavs (the Winden or " Windische ") were gradually assimilated, yet they left traces in the German dialect of Carinthia. The soft melody of Carinthian is reminiscent of South Slavic, many proper names end in -ig (Slovene -ik ) and some dialect words also correspond to Slavic. Typical characteristics of the Carinthian dialect are the different distribution of the vowel quantity and the gentle affricatization (like voiced gg ).

In addition, the Carinthian denotes strong sound darkening ("a" often becomes "o" instead of å ) and in the south monophthonging from mhd. Ei to a ( Dås wās i nit 'I don't know')

The South Bavarian has no r- vocalization , but it is advancing especially in city dialects. After vowels, l is not vocalized here, but as a preliminary stage e and i are rounded before l (e.g. Mülch ). In the cities the l -ocalization is advancing (also with proper names , e.g. Höga ). In addition, some southern Bavarian dialects differentiate between strong and weak sounds , as in Dåch next to Tåg, old k in Carinthia and in parts of Tyrol and Salzburg has been shifted to the affricate kch, as in Kchlea (clover). This affricate represents a phoneme (cf. the minimal pair rukn 'back' / rukchn 'back').

A characteristic of the Carinthian dialect is the so-called Carinthian stretching: Due to interference with Slovenian, many vowels are pronounced long, contrary to the High German norm, for example låːs lei laːfm 'just let it go'. This phenomenon has the consequence that, for example, “oven” and “open” coincide aloud (oːfm), as does Wiesn and know to [wi: zn].

Another feature of South Bavarian is the use of the words sein (1st person) and seint (3rd person) instead of the written German “are” (to me, be happy , we are happy ”). This shape is typical for the Tyrolean and Carinthian. However, it is hardly to be found in the transition dialects to Central Bavarian, which have already been mentioned several times. Instead, the Middle Bavarian san is used, sometimes with phonetic shades ( sän etc.).

Dialects of West and East Styria are characterized by the diphthongization of almost all accented vowels, which is colloquially known as "bark". In the vernacular, the o is mainly used together with u and ö with a subsequent ü ( ould 'old', Öülfnban 'ivory').

More precise subdivision

Apart from the historical isoglosses discussed above, Bavarian can also be divided into other dialects, which are mainly based on the regions. A specialty is the Viennese , but also the Munich . In Austria the Hianzisch in Burgenland, the Styrian dialects , the Carinthian dialects and the Tyrolean dialects exist . A very distinctive dialect in Upper Austria is the dialect of the Salzkammergut , in Lower Bavaria the Waidler language . In addition, there is Cimbrian and Eger German from the linguistic islands in Northern Italy and Bohemia.

Phonology

Vowels

Bavarian distinguishes long and short vowels from one another; However, this is not expressed in writing, but, as in standard German, by the number of consonants following the vowel: if there is only one or no consonant after the vowel, it is usually long; if two or more follow it, it is short. Here ch and sch each apply like a consonant, since these letter combinations only correspond to one sound.

The distribution of long and short vowels is completely different in Bavarian than in standard German, so that it sometimes seems as if every corresponding standard German word with a long vowel is short in Bavarian and vice versa; however, this is only partly true.

In total, Bavarian distinguishes between at least eight vowels, each with two levels of quantity.

Compare the following comparisons:

| vocal | long vowel | standard German | short vowel | standard German |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dark ɑ or ɒ | what | what | Wåssa | Water |

| middle ɐ | Staad | Country | Mass | Maß (beer) |

| light a | Dràm | Dream | dràmma | dream |

| light e | és , Héndl | you , chicken | wegga (d) , dreggad | away , dirty |

| dark ɛ | Bede | Peter | bèdt! | pray! |

| i | gwiss | sure | know | know |

| O | Ofa / Ofn | Furnace | offa / offn | open |

| u | Train | Train | zrugg | back |

The speaker in the above Examples speak Middle Bavarian and of course German as their mother tongue, but with a Bavarian accent.

In the Middle Bavarian dialects of Austria and in parts of Salzburg, vowels are usually long before weak sounds and r, l, n , and short before strong sounds. For distribution in Carinthia s. Carinthian dialect.

Dark vs. medium vs. light a

Phonologically, the Bavarian dialects differentiate between up to three a-qualities. This means that a distinction is sometimes made between light à, medium a and dark å , with light à originating from the Middle High German ä or the diphthongs ou / öu, in Carinthian and Viennese also from the diphthong ei . Today in Bavarian lààr it says empty compared to standard German , both from mhd. Lære, i glààb compared to I believe, both from ich g (e) loube, kärntn. / Wien. hààß (rest of Bavarian: hoaß ) compared to hot, all from mhd. heiz. The representation of a Middle High German a-sound, however, is usually a "darkened" one, i.e. H. a sound further back in the mouth and also more highly developed from the position of the tongue. So appear Middle High German Wazzer, hare, wâr example as water, Haas, waar / woa compared to standard German Water, Hare and true. Regionally, there can also be variations between the dark å and the middle a (see mia håmma / mia hamma ), but not between one of these two a sounds and the light à . Umlaut occurs especially in the formation of the diminutive with the suffixes -l and -al . i.e. , dark -å- becomes light -à-. Below are some examples of the a -sound, including some distinct minimal pairs :

| dark å as in engl. (US) to call [ ɑ ] or Hungarian a [ɒ]: a lab [ɒ lɒb] |

middle a like [ ɐ ] |

light à like [ a ] or even more open |

|---|---|---|

| å ('from / to') | A8 ('[Autobahn] A8') | à ('after'), àà ('also') |

| wåhr ('true') | i wa (r) ('i was') | i would be ('I would be') |

| mia håm ('we have') | mia ham ('we have') | mia hàn ('we are') |

| Ståd ('city') | Staad ('State') | stààd ('still'), Stàddal ('town') |

| Såg ('sack / saw') | Saag ('coffin') | Sàggal ('little bag') / Sààg (à) l ('little saw') |

| Måß ('the measure') | Mass ('die Mass [beer]') | Màssl ('luck') |

NB: Unstressed a are always light and are therefore not marked as such. This is especially true for the indefinite article, which is always unstressed, as well as for all unstressed a in inflected endings (e.g. in the plural of nouns and in the case of the adjectives).

The shortest sentence, which contains the three "a", is: "Iatz is des A àà å." (Now the A [= the A string of the guitar] is also off [= torn] ...)

Pronunciation of place names

In almost all Bavarian place names that end in -ing , any -a- present in the stem must be pronounced lightly; So “Plàttling” (not * “Plåttling”) and “Gàching” (instead of * “Gårching”), also “Gàmisch” (instead of * “Gåmisch”) and beyond that “Gràz” (not * “Gråz” - the city was called in the Middle Ages finally “Grätz”, from which the light a ) developed. Exceptions are some place names with -all- such as “Bålling / Båing” (Palling) or “Dålling” (Thalling).

Differentiation from the above

Standard German speakers perceive the light à in Bavarian as ordinary a , while the dark å is mostly an open o, which is why many Bavarians also tend to write dark a as o (ie mocha instead of måcha for “to do”). However, this notation leads to a coincidence with the Bavarian o, which is always spoken in a closed manner (i.e. direction u ). The words for “oven” and “open” in Bavarian do not differ in the quality of the vowels, but only in the length of the vowels, which, as in standard German, is expressed by the doubling of consonants (also known as gemination ): Ofa (long) vs. offa (short) with constant vowel quality.

Closed vs. open e

The sharp separation that still exists in Middle High German between the open e-sound inherited from Germanic and the closed e-sound resulting from the primary umlaut of a has been abandoned in large parts of Bavarian, so that almost every stressed short e is closed (in In contrast to standard German: here all these are open), d. i.e., it sounds closer to i than standard German e. There are only a few words with a short open è; the best example is the following minimal pair: beds ("beds", with a closed e ) vs. bètn ("pray", with an open è ). In standard German, however, it is exactly the other way around in this example: the word “bed” has an open (because it is short), the word “pray” has a closed (because it is long) e. However, there are also exceptions to this. The Salzburg mountain dialects, for example (but also other) preserve the old order in most positions, so it there ESSN instead essn , Wetta or Wèitta with diphthongization for "weather" instead of Weda , but bessa "better" Est "branches" or knitted "Guests" means.

Unstressed i or e

In addition to the unstressed a, there is also another unstressed vowel in Bavarian, which stands between i and e , and is spoken more openly (direction e ) or closed (direction i ) depending on the dialect . It mostly originated from the secondary syllable -el in words like gràbbin ("crawl") or Deifi ("devil") and is written below as i . This sound is not to be confused with that which occurs only in the definite article of the masculine (in the forms im, in ), which lies between i and dull ü .

Schwa-Laut

In most Bavarian dialects, the Schwa sound, which corresponds to the unstressed e in standard German, has no phoneme status. Regionally it occurs in certain positions as an allophone to the unstressed a and i .

Diphthongs

Another characteristic of Bavarian is the retention of the Middle High German diphthongs ie, üe, uo as ia and ua, as in liab, griassn, Bruada (“dear, greetings, brother”), which distinguishes it from East Franconian Bruda , which is simple like the high language Long vowels used. Towards the west, Bavarian delimits itself with Dåg, Wåsser and dàd (“day, water” and “täte”) from Swabian Dààg, Wàsser and däät .

These diphthongs are joined by the new diphthongs öi, oi, ui, which arose from the vocalization from l after vowel to i . In total, most Bavarian dialects distinguish 10 diphthongs, namely:

| diphthong | Examples | standard German | diphthong | Examples | standard German |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ea | i hea (her) | I hear | egg | no | New |

| oa | i woass | I know | åi, oi | fåin, foin | fall |

| ia | d'Liab | love | öi, äi | schnöi, schnäi | fast |

| among others | i dua | I do | ui | i fui | I feel |

| ouch | i look | I am looking | ou | Doud | death |

Historical digression: old vs. young egg

A special characteristic of Bavarian is the vowel oa ( pronounced as a in Eastern Austria ), which arose from the Middle High German ei . This sound change only affects the so-called older ei of German, but not the younger ei, which only emerged from the Middle High German long î in the course of the New High German diphthong and therefore no longer participated in the sound change. That is why it is called in Bavarian "oans, zwoa, three" - the first two numerals have an older ei as the stem vowel, the third numeral a younger ei, which was still third in Middle High German .

However, there is a third, even younger egg in Bavarian , which arose from the rounding of the diphthong nhd. Eu , äu , which is derived from the long vowel mhd. Iu ([ yː ]), or mhd. Öu . However, reflexes of an older sound level can still be found. In Tyrolean dialects it can be nui (new), tuier (expensive) or Tuifl , while in Salzburg, for example, noi (new), toia (expensive) or Toifi can be heard. A brief overview:

| According to | Middle High German sound level | Bavarian loudness | New High German sound level | English comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| old egg | egg | oa, z. B. gloa, Goaß, Stoa, Loab, hoazn | ei, z. B. small, goat, stone, loaf, heat | clean, goat, stone, loaf, heat |

| middle egg | î | ei, z. B. white, three, riding, Leiwi | ei, z. B. know, drive, ride, body | white, drive, ride, life |

| young egg | iu | ei, z. B. nei / neig / neich, deia, Deifi, Greiz, Hei / Heing | eu, z. B. new, expensive, devil, cross, hay | new, dear, devil, cross, hay |

In North Bavarian oa (Middle High German ei ) appears as oa, oi or åå (the latter only in the north towards East Franconian ) depending on the dialect and sound environment . This is how a kloana Stoa sounds like a kloina Stoi in parts of northern Bavaria.

Remarks

Spiritual words

There are, however, exceptions to the sound change rule ei > oa, which mainly concern words that were presumably preserved in their old form through their use in worship; These are spirit, flesh, holy and the month names May, which should actually be Goast, Floasch, hoalig, and Moa , but do not exist in this sound form in Bavarian.

Boa (r) or Baier?

The conventional Bavarian sound for "Baier", "Bairin", "Baiern", "Bavarian" and "Bavaria" is Boa (r), Boarin, Boa (r) n, boaresch / boarisch, Boa (r) n. In the 20th century, however, the written German sounds have spread - depending on the word. In the older dialect, the name of the country was also often combined with the neuter article: s Boarn "das Bayern".

Consonants

The Bavarian consonant system comprises around 20 phonemes, the status of which is partly controversial:

| bilabial |

labio- dental |

alveolar |

post- alveolar |

palatal | velar | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | b p | d t | g k | ʔ | |||

| Affricates | pf | ts | tʃ | ( kx ) | |||

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| Vibrants | r | ||||||

| Fricatives | f v | s ( z ) | ʃ | ( ç ) | ( x ) | H | |

| Approximants | j 1 | ||||||

| Lateral | l |

The sound j is a semi-vowel. Parenthesized consonants are allophones of other consonants; these are distributed as follows:

- h occurs only in the initial sound, its allophones x and ç in contrast, in the internal or final volume

- z occurs as a voiced variant of s in some dialects, v. a. intervocalic; but never in the initial sound, as is the case in stage German

- Some dialects, especially southern Bavarian dialects such as Tyrolean, know the affrikata kx , which arose from the High German sound shift .

Although the Fortis plosives p and t coincide with their Lenis counterparts b and d in the initial sound, they cannot be regarded as two allophones of one phoneme each , since they have different meanings in certain positions. Only in the initial sound can they be viewed as variants, the pronunciation of which depends on the following sound - see the following paragraph and the glottic stroke below.

Plosives or plosives

In most Bavarian dialects and the Fortis Lenis- are plosives p, t, k , and b, d, g in initial position and collapsed between vowels and will not be further distinguished. That is why the “day” is called da Dåg in Bavarian , the “cross” is called as Greiz, and the “parsley” is called da Bêdasui, and that is why words like “drink” and “penetrate” fall together to form dringa . The only Fortis sound is k- at the beginning of a word, if it is followed by a vowel; before r, l and n it is also to g lenited. It should be noted, however, that the Bavarian lenes are bare but generally voiceless. For North and Central Germans they don't sound like b, d, g, but like a mixture of these and p, t, k.

The sounds b, d and g are fortified at the beginning of the word before s, sch, f and h ; However, these new Fortis sounds do not have a phoneme , but only an allophone status, because they only occur in certain environments where their Lenis variants do not occur, and therefore cannot relate to them in a meaningful way. Examples of fortization in Bavarian:

| Lenis | Fortis | standard German |

|---|---|---|

| b + hiátn | > p hiátn | watch over |

| d + hex | > t hex | the witch |

| g + hoitn | > k hoitn | held |

Fricatives or gliding sounds

The Bavarian knows five fricatives; f (voiceless) and w (voiced) form a pair. The fricative s is always voiceless except before n , so in contrast to German also at the beginning of the word. For this purpose, the written letter combinations with sounds coming ch and sch, wherein ch as allophone [ x ] or [ ç ] (after -i- or -e- ) to anlautendem h [ h ] occurs in the internal or final volume. Unlike in German, the sound ch does not come after -n- , hence bair. Minga, mank, Menk vs. German Munich, some, monk,

Sonorants

The Bairische has the same sonorant inventory as the standard German, namely the nasals m, n and ng [ ŋ ] and l, r and j. The r is rolled in some areas with the tip of his tongue, (so-called. Uvulares in other parts of the uvula r ), without this being perceived by Bavarian-speakers as an error.

Morphology (theory of forms)

Nominal inflection

The entire Bavarian noun inflection is based on the noun whose grammatical gender or gender constitutes the declension of the noun phrase; d. That is, both article and adjective and other attributes must be aligned in gender, case and number with the noun they accompany. There are three genera: masculine, feminine and neuter. The cases or case nominative, dative and accusative as well as the numbers singular and plural exist as paradigmatic categories . Adjectives can also be increased.

The article

In Bavarian nouns are divided according to their grammatical gender, gender ; The gender is usually not recognizable by the noun itself, but by its accompanying specific article:

| masculine | feminine | neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| da dog (the dog) | d'Ruam (the turnip) | as / 's child (the child) | de / d'Leid (the people) |

The definite article singular of the feminine, d ', often assimilates to the initial sound of the accompanying noun: before fricatives (f, h, s, z) it is hardened to t' , before labials (b, m, p) to b ' and before velars (g, k) assimilated to g'- . Examples:

| d '> t' | d '> b' | d '> g' |

|---|---|---|

| t'woman (the woman) | b'Bian (the pear) | g'Gåfi / Gåbe (the fork) |

| t'Haud (the skin) | b'Muadda (the mother) | g'Kua (the cow) |

| t'Sunn (the sun) | b'Pfånn (the pan) |

Before f- , however, it can also become p ' in Allegro pronunciation : p'Frau (the woman), p'Fiaß (the feet).

The indefinite article, on the other hand, is identical for all three genera in the nominative ; In contrast to standard German, however, Bavarian also has an indefinite article in the plural (see French des ):

| masculine | feminine | neuter |

|---|---|---|

| a Må (a man) | a woman (a woman) | a child (a child) |

| oa Måna (men) | oa woman (a) n (women) | oa Kinda (children) |

In the basilect , a before a vowel becomes an. In Lower Bavarian the indefinite article occurs in the plural partly in the phonetic form oi , in Carinthian as ane; the definite article always keeps the final vowel ( de, nie d ' ).

The article is inflected in Bavarian, i.e. i.e., the case is made clear by it. Because most nouns in Bavarian have lost all case endings, the case display is largely concentrated on the article. An overview of his paradigm:

| best. | masculine | feminine | neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nom: | there dog | d'Ruam | as child / 's child | de Leid / d'Leid |

| dat: | in the dog | da Ruam | in the child | de Leid / d'Leid |

| battery: | in dog | d'Ruam | as child / 's child | de Leid / d'Leid |

| indefinite | masculine | feminine | neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nom: | a dog | a Ruam | a child | oa / oi sorrow |

| dat: | on the dog | ana / oana Ruam | on the child | ane / oane suffering |

| battery: | to dog | a Ruam | a child | oa / oi sorrow |

The noun

The noun is one of the inflected parts of speech in Bavarian; Its most striking criterion is - as in other Germanic languages - the gender (gender), which is only rarely based on the object to be designated and therefore has to be learned with every word. However, those familiar with the German language should have no problem with that.

Plural formation

Bavarian has retained three of the four cases commonly used in standard German : nominative, dative and accusative . The latter two partially coincide; Genitive is only preserved in frozen expressions. As in standard German, the Bavarian noun is rarely declined, but expresses case through the accompanying article. There are different classes of declension , which mainly differ in the formation of the plural; As a rough guideline, a distinction is made between weak declination (so-called n-class) and strong declination (so-called a-class).

Weak nouns

Weak nouns usually end in -n in the plural. Many weak feminines already form the singular on the suffix -n, so that in the plural they either read the same or add -a (in analogy to the strongly inflected nouns). The weak masculine especially have an ending for the oblique case in the singular , i.e. H. for all cases except the nominative, preserved. Mostly it is -n.

The class of weak nouns (W1) includes masculine and feminine nouns with -n in the plural as well as all feminines with the plural ending -an (which usually end in -ng in the singular ; the -a- is a so-called scion vowel or epenthetic ). Furthermore, all masculine and neuter that end in the singular with the suffix -i can be classified here. Many of the related nouns of Standard German are strong there, however, hence the standard German plural for comparison:

| W1: -n | Singular | Plural | standard German | Singular | Plural | standard German | Singular | Plural | standard German |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m: | Hås | Håsn | Hare | bush | Bushn | bush | Deifi | Deifin | devil |

| f: -n | Brugg | Bruggn | Bridge, bridges | Goass | Goassn | goat | nut | Nuts | nut |

| f: -an | Dàm | Dàman | lady | Schlång | Schlångan | Snake | Clothing | Notice | newspaper |

| n: | Oar | Oarn | ear | Bleami | Bleamin | flower | Shdiggi | Schdiggin | piece |

Strong nouns

There are no case endings for the strong declension classes; the only change in the word takes place in number inflection, i.e. when changing from singular to plural. There are different ways of marking the plural in Bavarian. Strong masculine and neuter characters use the ending -a, which mostly originated from the Middle High German ending -er and is still preserved as such in New High German . However, there are also words that have only recently been added to this class , i.e. form an a -plural without ever having an er -plural. Feminines often form their plural with the ending -an, as the word ending itself does: oa ending, zwoa endingan.

You can divide nouns into different classes based on their plural forms. The most common possibilities of plural formation are umlaut or suffixation; both options can also be combined. -N and -a appear as plural endings ; There are the following variants of umlauts:

| S1: Umlaut (UL) | Singular | Plural | standard German | S2: UL + -a | Singular | Plural | standard German |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| å> à | Nåcht (f) | Night | night | ||||

| å> e | Dåg (m) | Deg | Day | Lånd (n) | Lenda | country | |

| o> e | Dochta (f) | Dechta | daughter | Hole (noun) | Lecha | hole | |

| u> i | Fox (noun) | Fichs | Fox | Mouth (noun) | Minda | mouth | |

| au> ai | Mouse (noun) | Corn | mouse | House (noun) | Haisa | House | |

| ua> ia | Bruada (m) | Briada | Brothers | Buach (n) | Biacha | book | |

| åi, oi> äi, öi | Fåi (m) | Fäi | case | Woid (noun) | Woida | Forest |

The examples given here form classes 1 and 2 of strong nouns, which are characterized by an umlaut plural. The class (S1) has no additional plural identifier besides the umlaut, so it is endless; only masculine and feminine members belong to her. Class S2, which is characterized by the umlaut plural plus the ending -a (which mostly corresponds to the standard German ending -er ), includes some masculine and many neuter. The same rules for umlaut apply as above:

Class S3 includes all masculine , feminine and neuter without umlaut with the plural ending -a; most feminines end in the singular with the original dative ending -n. Some masculine nouns whose stem ends in vowel have the ending -na:

| S3: -a | Singular | Plural | standard german | Singular | Plural | standard german | Singular | Plural | standard german |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m: | Bàm | Bàm, Bàma | tree | Mõ, Må | Måna | man | Stõa | Stõa, Stoana | stone |

| f: | A | One | owl | Paradeis | Paradeisa | tomato | |||

| n: | child | Kinda | child | Liacht | Liachta | light | Gschèft | Gschèfta | business |

The last strong class (S4) are nouns with zero plural, for example 'fish' (m) and 'sheep' (n). In some dialects, however, these nouns express the plural by shortening or lengthening the vowel. This class actually only consists of masculine and neuter; however, all feminines ending in -n, which historically belong to the weak nouns, can also be counted here, as their plural is also unmarked: 'Àntn - Àntn' "duck". However, these feminines gradually change to group S3 and adopt the ending -a in the plural (cf. the example of an "owl" above ).

There are also some irregular plural forms in Bavarian:

| Singular | Plural | standard German | |

|---|---|---|---|

| m: | Boar, also Baia | Baian | Baier |

| f: | Beng | Benk | (Seat) bench |

| n: | Gscheng | Gschenka | gift |

| Aug | Aung | eye | |

| Fàggi | Fàggin / Fàggal | Piglet, pig | |

| Kaiwi | Kaiwin / Kaibla | calf |

The following words only exist in the plural: Suffering (people), Heana / Hiana (chickens), Fiacha ( the cattle, for example cattle; not to be confused with Fiech, Fiecha , for example mosquitoes).

Case relics

Some weak masculine nouns have retained case endings in the oblique cases , i.e. in the dative and accusative, e.g. B. Fåda "father" and Bua "son; Boy, boy ":

| best. | Singular | Plural | best. | Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nom | da Fåda | t'Fådan | nom | da Bua | d'Buam (a) | |

| dat | at Fådan | di Fådan | dat | at the boy | di Buam (a) | |

| battery | to Fådan | t'Fådan | battery | to Buam | d'Buam (a) |

Often d / is assimilated across the word boundary ( Sandhi ), so it is mostly called Nom./Akk. Pl. B Fådan and b buam (a).

Just as Fada inflect Baua "Bauer" Boi "ball", Breiss (of Prussian) "North German; Fremder ”, Depp “ Depp ”, Buasch [Austrian]“ Bursche, Bub , Junge ” Frånk “ Franke ”, Frånzos “ Franzose ”, Hiasch “ Hirsch ”, Hås “ Hase ”, Lef “ Löwe ”and a few others. Similar to Bua, the words Råb inflect "Rabe" and Schwåb "Schwabe": all forms except nominative singular have the stem ending -m instead of -b : Råm, Schwåm; the plural forms Råma, Schwåma are rare.

Excursus: gender deviating from standard German

The grammatical gender of a noun is marked on the article (see above). In most cases, the gender of a Bavarian word corresponds to that of the corresponding word in standard German. But there are quite a few exceptions. Many of them can also be found in the neighboring Alemannic dialects , for example in Swabian .

It should be noted that in Austrian Standard German the use of gender differs from Federal German in individual cases and corresponds to the usage of Bavarian language.

| standard German | Bavarian | standard German | Bavarian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| the ash | da Åschn (m) | the cart, ( in Austria too ) the cart | da Kårn (m) | |

| the butter | da Budda (m) | the dish | as Della / Dölla, as Dala (n) | |

| the radio | da radio (noun) | the comment | also: as comment (s) | |

| the potato | da Kardoffe (m) | the drawer | da drawer ( noun ) | |

| the onion | da Zwife (m) | the jam | s'Mamalàd (n) | |

| the virus | da virus ** (m) | the chocolate | da Tschoglàd (m) | |

| the shard | da Scheam (m) | the sock, ( in Austria ) the sock | da Socka (m) / as Segge (n) | |

| the toe | da Zêcha (m) | the prong | da Zaggn (m) | |

| the parsley | da Bèdasui / Bèdasüü (m) | the rat | da Råtz (m) | |

| the skirt | da Schurz (m) | the wasp | da Weps (m) | |

| The Lord's Prayer | da Vadtaunsa * (m) | the tick, ( in Austria also ) the tick | da Zegg (m) | |

| the month | also: s Monad *** (n) | The Grasshopper | da Heischregg (m) | |

| the hay | d'Heing (f) or as Hai (n) | the snail, ( in Austria also ) the snail | da Schnegg (m) | |

| the tunnel | as Tunnöi / Tunnöö / Tunell [-'-] (n) | the tip, ( in Austria ) the tip | da Schbiez (m) | |

| the swamp | d'Sumpfn (f) | the corner, ( in Austria ) the corner | s'Egg (n) | |

| the fat | b'Feddn (f) | the Masel, ( in Austria also ) the Masen | d'Màsn | |

| the ketchup, (in Bavaria / Austria) the ketchup | s'Ketchup (n) | the praline | the praline (s) |

* Also "the paternoster" (rare) is male in Bavarian.

** This modification, based on the Latin words ending in -us and German words ending in -er, which are almost always masculine, shares Bavarian with everyday and colloquial high German.

*** Especially in the expressions "every month" (every month), "next month" (next month), "last month" (last month) etc. - but never with month names: da Monad Mai etc.

Pronouns

Personal pronouns

In terms of personal pronouns , Bavarian, like many Romance and Slavic languages, differentiates between stressed and unstressed forms in the dative (only 1st, 2nd singular) and accusative (only 3rd singular and plural); There is also an independent politeness pronoun in the direct address, comparable to the German "Sie":

| 1st singular | 2nd singular | 3rd singular | 1st plural | 2nd plural | 3rd plural | Politeness pronouns | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nom | i | you | ea, se / de, des | mia | Eß / öß / ia * | se | Si |

| unstressed | i | - | -a, -'s, -'s | -ma | -'s | -'s | -'S |

| dat | mia | slide | eam, eara / iara, dem | us | enk / eich * | ea, eana | Eana |

| unstressed | -ma | -there | |||||

| battery | -mi | -de | eam, eara / iara, des | us | enk / eich * | ea, eana | Eana |

| unstressed | -'n, ..., -'s | -'s | Si |

* These forms are considered "less" Bavarian, but are typically Franconian.

In North Bavarian the nominative is the 2nd pl. Dia, in South Bavarian the dative is the 3rd pl. Sen.

When combining several unstressed personal pronouns that are shortened to -'s , the connecting vowel -a- is inserted; In contrast to German, there are different variants of the order of arrangement. There can also be ambiguity - a couple of examples:

| unstressed | * (written out) | standard German | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.a) | Håm it zoagt there? | Håm s (e) d (ia) (de) s scho zoagt? | Have they shown you yet? |

| or: | Håm sd (ia) s (dia) scho zoagt? | Have they shown you yet? | |

| 1.b) | Håm'sas da scho zoagt? | Håm s (de) sd (ia) scho zoagt? | Have they shown you yet? |

| or: | Håm s (e) da d (ia) scho zoagt? | Have they shown you yet? | |

| 2.a) | Håd a ma'n no ned gem? | Håd (e) am (ia) (der) n no ned according to? | Hasn't he given it to me yet? |

| 2 B) | Håd a'n ma no ned according to? | * Håd (e) ad (ern) m (ia) no ned according to? | Hasn't he given it to me yet? |

Possessive pronouns

a) predicative:

| masculine | feminine | neuter | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nom | mẽi | mẽi | mẽi | my |

| dat | meim | meina | meim | my |

| battery | my | mẽi | mẽi | my |

b) attributive:

| masculine | feminine | neuter | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nom | meina | my | mine | my |

| dat | meim | meina | meim | my |

| battery | my | my | mine | my |

The possessive pronouns deina and seina also inflect like this. The possessive pronoun (Fem. Sg.) Iara ("their") has penetrated from the standard German language; originally Bavarian also uses the pronoun seina for female owners . Often the noun adjective der mei (nige) (der dei (nige), der sein (nige), in the plural: de meinign, de deinign ...) is used: "Whom ghead der?" - "Des is da mẽi!" (= that's mine!)

Indefinite and question pronouns

Just like the possessive pronouns listed above, the indefinite pronouns koana “none” and oana, which means “one” in standard German, inflect ; the latter can be prefixed with the word iagad- (“Any-”), as in German .

There is also the indefinite pronoun ebba, ebbs "someone, something"; it is pluralless and inflected as follows:

| person | Thing | |

|---|---|---|

| nom | ebba | ebbs |

| dat | ebbam | ebbam |

| battery | ebban | ebbs |

So here a distinction is not made between the sexes, but between people and things.

The same applies to the question pronoun wea, wås "who, what":

| person | Thing | |

|---|---|---|

| nom | wea | What |

| dat | whom | whom |

| battery | whom | What |

Adjectives

Many Bavarian adjectives have a short form and a long form. The former is used in the predicative position, i.e. when the adjective forms a predicate with the auxiliary verb sei (for example as Gwand is rosa ). The long form is used when the adjective serves as an attribute of a noun (for example the rosane Gwand ), in the nominative neuter singular the short form can also be used (a rosa (n) s Gwand). Short form and long form often differ (as in the example) by a final consonant, which the short form lacks (in this case -n ), and only occurs in the long form ( des Sche n e Haus, but: Sche ). Most of the time these final consonants are -n, -ch, -g.

Declination of adjectives

As in German, adjectives are inflected in an attributive position, i.e. that is, they have different endings. A distinction must be made between whether they accompany a noun with a definite article (and therefore inflect in a certain form) or one with an indefinite article (and then inflect it according to an indefinite pattern). If adjectives are used substantively, i.e. only with an article, they are also based on this. The adjective sche (beautiful) serves as an example, the stem of which is expanded by -n when inflected (except for the neuter singular).

| "Sche" indefinite | masculine | feminine | neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nom: | a schena Mon | a beautiful woman | a little child | d 'schena sorrow |

| dat: | on beautiful Mon. | anaschenan wife | at the beautiful child | I'm suffering |

| battery: | to beautiful Mon. | a beautiful woman | a little child | d 'schena sorrow |

| "Sche" determined | masculine | feminine | neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nom: | there nice Mo | d 'beautiful woman | a beautiful child | d schena sorry |

| dat: | (i) m schena Mon | da schan woman | am schena (n) child | d schena sorry |

| battery: | n nice Mon | d 'beautiful woman | a beautiful child | d schena sorry |

In the predicative position, on the other hand, adjectives - as in German - are not inflected, but only used in their nominal form:

| predictive | masculine | feminine | neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| indefinite: | a Mo is cal | a woman is shit | a child is shit | d sorry sàn sche |

| certainly: | da Mo is she | d'Woman is she | the child is shit | d sorry sàn sche |

Increase in adjectives

In Bavarian, the suffix -a is used to form the comparative , the first form of increase. The basis of the comparative is the long form described above; some adjectives have umlauts, others change the vowel length or the consonantic end. Examples from West Central Bavaria:

| umlaut | positive | comparative | Standard German |

|---|---|---|---|

| no umlaut: | |||

| gscheid | gscheida | Smart | |

| no | neiga / neicha | New | |

| liab | liawa | dear | |

| schiach | schiacha | ugly | |

| hoagli | hoaglicha | picky | |

| diaf | diaffa | deep | |

| with vowel abbreviation: | |||

| å> e: | long | lenga | long |

| å> à: | warm | warm | warm (West Middle Bavarian) |

| o> e: | rough | grewa | rough |

| big | gressa | big | |

| u> i: | stupid | dimma | stupid |

| healthy | gsinda | healthy | |

| young | jinga | young | |

| oa> ea: | broad | breada | wide |

| gloa | gleana | small | |

| hate | heaßa | hot | |

| after | weacha | soft | |

| woam | weama | warm (East Central Bavarian) | |

| oa> öi: | koid | köida | cold |

| oid | oida | old | |

| ua> ia: | kuaz | kiaza | short |

For the superlative , depending on the landscape, a separate shape is created on (as in standard German) -st or not. In the latter case, the comparative is used as a superlative offset. The sentence “Max Müller is the tallest of the twelve boys” in Bavarian can produce the following variants: “Vo de zwöif Buam is dà Müller Màx am gressan (comparative) / am greßtn (superlative) / seldom dà greßte / dà gressane.” It there is also a suppletive adjective enhancement, i.e. enhancement with another word stem (so-called strong suppletion) or a stem extension (so-called weak suppletion):

| Suppletion | positive | comparative | superlative | Standard German |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| strong: | guad | better | am bessan | Well |

| stâd | leisa | am leisan | quietly | |

| weak: | deia (a deirigs ...) | deiriga | at deirigan | expensive |

Numeralia (numerals)

Bavarian numerals end differently depending on the region, but mostly with -e, which they often repel in an attributive position; they are immutable, so do not inflect. An exception to this is the numeral oans for the number 1.

The following is a list of the most important Numeralia ; they are difficult to pronounce for non-native speakers, partly because of their unusual consonant sequences:

| 1 | oas / oans / àns | 11 | öif (e) / ööf | 21st | oana- / ànazwånzg (e) | ||||||||

| 2 | zwoa / zwà * | 12 | twelve (e) / twelve | 22nd | zwoara- / zwàrazwånzg (e) | 200 | zwoa- / zwàhundad | ||||||

| 3 | three | 13 | dreizea / dreizen | 23 | dreiazwånzg (e) | 300 | threehundad | ||||||

| 4th | fiar (e) | 14th | fiazea / fiazen | 24 | fiarazwånzg (e) | 40 | fiazg (e) | 400 | fiahundad | ||||

| 5 | fimf (e) | 15th | fuchzea / fuchzen | 25th | fimfazwånzg (e) | 50 | fuchzg (e) | 500 | fimfhundad | ||||

| 6th | seggs (e) | 16 | sixth / sixth | 26th | seggsazwånzg (e) | 60 | sixty (e) | 600 | six dog ad | ||||

| 7th | siem (e) | 17th | sibzea / sibzen | 27 | simmazwånzge | 70 | sibzg (e) / siwazg (e) | 700 | siemhundad | ||||

| 8th | eighth) | 18th | åchzea / åchzen | 28 | åchtazwånzge | 80 | åchtzg (e) | 800 | åchthundad | ||||

| 9 | no / no | 19th | neizea / neizen | 29 | no longer | 90 | no (s) | 900 | neihundad | ||||

| 10 | zeene / zeah | 20th | Zwånzg (e) e / twenty (e) | 30th | thirty | 100 | hundad | 1000 | dausnd |

- West Central Bavarian still differentiates regionally into three genders when it comes to the number “two”: “two” (masculine), “zwo” (feminine) and “zwoa / zwà” (neuter), although this distinction is now out of date or out of date and through the neuter form "zwoa / zwà" has been displaced.

Example sentences: "Sie hand ea two" = "There are two (men, boys etc.)", "Sie hand ea two" = "There are two (women, girls etc.)".

Substantiated numbers are masculine in Bavarian, as in Austrian German, while feminine in Germany:

| Bavarian | Standard German (D) | Bavarian | Standard German (D) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| da nulla | the zero | da Åchta | the eight | |

| da Oasa / Oansa / Ànsa | the one | there no | the nine | |

| da Zwoara / Zwàra | the two | da Zena | the ten | |

| there Dreia | the three | there Öifa / Ööfa | the elf | |

| da Fiara | the four | da Zwöifa / Zwööfa | the twelve | |

| da fimfa | the five | da Dreizena | the thirteen | |

| da sixa | the six | da Dreißga | thirty | |

| da Simma / Siema | the seven | da Hundada | the hundred |

Verbal system

The Bavarian only knows a synthetic tense , the present tense . All other tenses, namely future and perfect tense , have been formed analytically since the Upper German past tense decline. As a mode in addition to indicative and imperative , Bavarian also has a synthetic, i.e. H. Formed without an auxiliary verb , subjunctive , which corresponds to the standard German subjunctive II (mostly in function of the unrealis , the optative or as a polite form).

Conjugation of weak verbs

As in German, the indicative expresses reality; it is formed by adding different endings to the verb stem and is generally relatively close to standard German. Sometimes the plural endings differ from standard German. In the following the example paradigm of the weak verb måcha (to make) in the indicative and subjunctive as well as in the imperative:

| måcha | indicative | imperative | conjunctive |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sg | i can | - | i måchad |

| 2nd Sg | are you doing | måch! | you måchast |

| 3rd Sg | he makes | - | he måchad |

| 1st pl | mia måchan * | måchma! | mia måchadn |

| 2nd pl | eat it | does it! | eat måchats |

| 3rd pl | se måchan (t) ** | - | se måchadn |

Participle of this verb is gmåcht - see for more details under past .

* See the next paragraph.

** Regarding the 3rd person plural, it should be noted that in some areas (for example in Carinthia) the ending t from Old High German has been retained, which has become the general plural ending in Swabian (mia, ia, si machet).

In the 1st person plural, only one form was used. In fact, in addition to the (older) short form above, there is also a (younger) long form, which (except in the subordinate sentence, where it is ungrammatic in most regions) is the more commonly used. It is formed by replacing the ending -an with the ending -ma , i.e.: måchma. For the origin of this form s. u. Digression .

Verbs with alternations

However, there are verbs that deviate from this ending scheme because their stem ends in -g or -b , and thus merges with the original infinitive ending -n to -ng or -m . In addition, the stem ending -b before the vowel ending is usually fricatized to -w- . This creates so-called end-of-speech changes in flexion; Examples are sång (to say) and lem (to live):

| sång | indicative | imperative | conjunctive |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sg | i såg | - | i sågad |

| 2nd Sg | you say | say! | you sågast |

| 3rd Sg | he says | - | he sågad |

| 1st pl | mia så ng | - | mia sågadn |

| 2nd pl | eat sågts | - | eat sågats |

| 3rd pl | se så ng (t) | - | se sågadn |

The past participle is gsågt; Participle I is not in use.

| lem | indicative | imperative | conjunctive |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sg | i live | - | i le w ad |

| 2nd Sg | you live | live! | you le w ast |

| 3rd Sg | he lives | - | he le w ad |

| 1st pl | mia le m | - | mia le w adn |

| 2nd pl | eat live | - | eat le w ats |

| 3rd pl | se le m (t) | - | se le w adn |

The participle I reads lewad "alive", the participle II is alive.

Verbs with a subject suffix -a- or -i-

Another group of verbs whose infinitive ends in -an or -in shows the ending -d in the 1st person singular ; the theme-a or -i- is retained throughout the indicative paradigm. These verbs often correspond to the German verbs ending in -ern (> -an ) or -eln (> -in ); As an example, first zidan (trembling), which on the one hand shows ( -a- >) r -containing forms in the subjunctive , on the other hand can fall back on doubling the syllable -ad- :

| zidan | indicative | imperative | r-subjunctive | dupl. conjunctive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sg | i zidad | - | i zid r ad | i zid ad ad |

| 2nd Sg | you zidast | zidad! | you zid r ast | you zid ad ast |

| 3rd Sg | he zidad | - | he zid r ad | he zid ad ad |

| 1st pl | mia zidan | - | mia zid r adn / zid r adma | mia zid ad n / zid ad ma |

| 2nd pl | eat zidats | - | eat zid r ats | eat zid ad ats |

| 3rd pl | se zidan (t) | - | se zid r adn | se zid ad n |

In contrast to the above verb, the next verb kàmpin (to comb) has only one possibility of the subjunctive in addition to the periphrastic subjunctive that is possible everywhere (using the subjunctive of the auxiliary verb doa ), namely stem modulation i > l; a doubling of syllables as above is not possible:

| kàmpin | indicative | imperative | l subjunctive |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sg | i kàmpid | - | i kàmp l ad |

| 2nd Sg | you fight | kàmpid! | You Kamp l ast |

| 3rd Sg | he fights | - | he kàmp l ad |

| 1st pl | mia kàmpin | - | mia kàmp l adn |

| 2nd pl | eating kàmpits | - | eating kàmp l ats |

| 3rd pl | se kàmpin (t) | - | se kàmp l adn |

Conjugation of strong verbs

Strong verbs sometimes form their subjunctive with ablaut instead of the ad suffix, but you can also combine both. In the case of strong verbs with stem vowels -e-, -ea-, -ai- (see examples above), umlaut to -i-, -ia-, -ui- occurs in the indicative singular and imperative , unlike in standard German as well 1st person. The stem vowel -a- , on the other hand, is not changed: he strikes.

| kema | indicative | imperative | Conj. + Ablaut | Conj. + Ablaut + ad |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sg | i kim | - | i kâm | i kâmad |

| 2nd Sg | you kimst | kimm! | you came | you kâmast |

| 3rd Sg | he kimt | - | he came | he kâmad |

| 1st pl | mia keman | - | mia kâman / kâma | mia kâmadn / kâmadma |

| 2nd pl | eat kemts | - | eat it | eat kâmats |

| 3rd pl | se keman (t) | - | se kâman | se kâmadn |

Participle of this verb is kema - see for more details under past .

Strong verbs can also show alternations -b - / - w - / - m- ; Example according to "give":

| according to | indicative | imperative | Conj. + Ablaut | Conj. + Ablaut + ad |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sg | i give | - | i gâb | i gâ w ad |