History of Schweinfurt

|

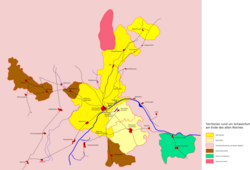

Territory in the Holy Roman Empire |

|

|---|---|

| Imperial city of Schweinfurt | |

| coat of arms | |

|

|

| map | |

|

|

| Form of rule | Imperial city |

| Ruler / government | magistrate |

| Today's region / s | DE-BY |

| Parliament | Swabian city bank |

| Reichskreis | Franconian Empire |

| Capitals / residences | Schweinfurt |

| Denomination / Religions | Roman Catholic , from 1542: Lutheran |

| Language / n |

German ( Lower Franconian )

|

| Incorporated into | 1806 Kingdom of Bavaria

|

Matthäus Merian, Frankfurt am Main

in Topographia Franconiae 1656

the former castle district

The history of Schweinfurt had its high point, with supra-regional political significance, around the year 1000. The subsequent imperial city of Schweinfurt only had regional significance. The city has played an important role again since the 20th century , as the center of the European rolling bearing industry , over which the Americans suffered their greatest air defeat in World War II .

The Schweinfurt area has a long history through almost all prehistoric and historical epochs in Central Europe due to the ford over the Main , fertile soil and its central location in the Franconian Empire . The villages surrounding the city are among the oldest in Germany (see: Dittelbrunn and Schwanfeld ). Today's Schweinfurt is at least 2100 years old. The margraves of Schweinfurt twice support East Franconian kings on their way to the imperial throne of the Holy Roman Empire. For example, the first Roman-German Emperor Otto I. The great time of the margraves, who had no male descendants, ended in 1057 at the latest. The Bamberg Monastery was created in the power vacuum in the center of the empire . In the 12th century , the imperial city of Schweinfurt, which corresponds to today's old town , was finally built 1 km down the Main (west) of the previous settlement and the castle hill Peterstirn der Margrave .

Beginnings

prehistory

Traces of settlement can be traced within today's urban area in different places, up to several kilometers apart, almost completely for 7500 years. From the linear ceramic culture (5500 to 5000 BC), the Neolithic (5500 to 2200 BC), the stitch band ceramic (4900 to 4500 BC), the Urnfield period (1300 to 800 BC), the Hallstatt period (800 to 450 BC), to the Latène period (450 BC to the year 0 ).

Early history

The name of the Affeltrach desert in the north-western part of the city, on the banks of the Wern on the Bellevue , is probably derived from the Old High German word for apple tree , aphaltar . Affeltrach would then have been the settlement near the apple trees . The village was probably founded in pre-Christian times, when Germanic tribes advanced into Franconia ; the ending in any case indicates that the settlement is very old. Around 500 BC The settlement by Celts is proven, among other things on the Biegenbach between the district Bergl and Geldersheim and during the Roman Empire at the same place a settlement by Teutons . There is also evidence of a settlement from the Merovingian period ( 5th century to 751).

Village old town

Until the founding of the imperial city in the 12th century , which corresponds to today's old town , the historic Schweinfurt was 1 kilometer further east. It was also on the Main, between the confluence of the Höllenbach in the east and the Marienbach in the west, at the foot of the Kiliansberg , which got its name from the church in the old town, the Kilianskirche . This settlement stretched along today's Mainberger Straße, immediately north of the city train station .

This first settlement called Schweinfurt is called in more recent times to differentiate it from today's old town Dorf Altstadt , because it i. Ggs. To the imperial city had no town charter. Since 2019, older and older finds have been made in the area of the old town, which go far beyond the early Middle Ages and unexpectedly extend to the beginning of the Neolithic (see: Schweinfurt, Prehistory ).

The area of the old town was completely built over again from the second half of the 19th century to the present day. The eastern part of this area at and in the Höllental is also called the old town based on history .

Early middle ages

Thuringians and Franks

The Thuringians ruled the northern Main Franconia before they were pushed back or overlaid by the Franks in the 6th century . The first settlements in the Schweinfurt area were probably founded by the Thuringians as early as the 5th century . Place names with the ending -ungen , such as Schonungen , Rannungen or Jeusungen , indicate Thuringian origins. The Franks defeated the Thuringians in 531 and then overlaid the first Schweinfurt settlement, the village of Altstadt . This was also associated with Christianization , which began in Franconia at the end of the 7th century .

Ford over the Main

The natural widening of the Main near Schweinfurt with side arms and islands has brought shallow water since ancient times. This was already known to people in the early days. North -south cross-regional connections converged north of a ford . Not far north, in the Schweinfurt Rhön , they crossed the Hochweg , later (1195) attested as Königsstraße recta strata . An important west-east connection from Frankfurt am Main via Banz in Schweinfurt to Bohemia . One of the first fords is assumed to be at the level of an oxbow lake of the Main, today's Sennfelder Seenkranz , a swamp and spring area.

Origin of the city name

Not the pig , but the swin gave the city its name. The word probably does not come from Old High German , but was brought back by the Franks from their original areas around the Maas and Schelde . In Dutch , Zwin (pronounced Swin) refers to a tidal creek , a watercourse in the mudflats and marshes . The Zwin is a silted up sea ox in Flanders ; Swin literally means to decrease ("to wane"), which in this context refers to the shallow water of a ford. The word was also in use in Old Saxon , as indicated by several places called Swinford in the British Isles . Furthermore, Swinoujscie on the Swine . Swin is also derived from a swamp area with springs that still exist around the Sennfelder Seenkranz as a landscape protection area. The name of the settlement is documented as follows:

|

|

|

First documentary mentions

The first written evidence of the existence of the settlement in the 8th century is its mention in the Codex Edelini of the Weißenburg monastery . Viticulture was probably already being carried out in Suinuurde at that time . This first definitely datable mention of the old town (see: Old town ) took place in the year 791. Hiltrih transferred a property in Suuinfurtero marcu to the Fulda monastery .

However, half a century before Oberndorf was first mentioned in a document in 741 in what is now the city of Oberndorf , only 37 years later as the first written mention of Franconia in 704 of Würzburg . In the first millennium there were two other first documentary mentions in the city area, both in 951, of the desert areas Affeltrach and Hilpersdorf . While the imperial city (today's old town ) was first mentioned in documents in 1254.

Margraviate Schweinfurt

Schweinfurt gained importance in 941 with the naming of Count Berthold as the first member of the house of the Counts of Schweinfurt. The family's origin is controversial. Schweinfurt was in the middle of Eastern Franconia , as well as in the middle of the subsequent Holy Roman Empire . Berthold's main dominions, however, were in the Nordgau and Radenzgau , which were secured by a chain of castles; the Volkfeldgau contained free float. As a result, he took an important position in the central realm, the Duchy of Franconia. Berthold gave the king of Eastern Franconia Otto I (936–973), who became Roman-German Emperor in 962 , valuable weapon aid against rebellious tribal dukes. As a thank you, Berthold received from Otto I. the counties for the Folkfeld and Radenzgau and the margraviate for the Nordgau , roughly today's Upper Palatinate . As a result, he and from 980 his son Heinrich were the most powerful secular noblemen in what is now northern Bavaria. The sphere of influence extended into the Bavarian Forest . The main castle was initially Sulzbach im Nordgau, which is why the noble family name "von Schweinfurt" actually only applies to Otto, Heinrich's son.

Schweinfurt feud

Later supported Count Heinrich , called by historians to distinguish a Kinderrufnamen "Hezilo", the East Frankish King Henry II. (1002-1024, from 1014 Roman-German emperor) at the election of the king in 1002, and got the duke of Bavaria promised. After the election, however, Heinrich II (HRR) did not keep the promise. Then there was the so-called Schweinfurt feud in 1003 . Count Heinrich lost this poorly prepared company, first of all lost his entire property, the royal estates in Rangau and the counties in Volkfeld, Radenz and Nordgau and fled to the Duke of Poland, Boleslaw Chobry , his ally. The confiscated royal estates formed the core of the new diocese of Bamberg , which was founded immediately afterwards by Heinrich II and in 1007 by Pope Johannes XVIII. has been confirmed. After negotiating mediators, Count Heinrich surrendered and was imprisoned by King Heinrich at Giebichenstein Castle . After intensive advocacy - e.g. B. Bishop Gottschalk von Freising on September 8th, 1004 in a sermon before the king - he pardoned him about a year later (1004). Whether Count Heinrich actually completely lost his royal fiefdom or was largely restituted is disputed. However, the count's monastery castle in Schweinfurt was only symbolically damaged by the personal commitment of Count Heinrich's mother Eila von Walbeck (see The Counts of Walbeck ), by the king's two ambassadors, Bishop Heinrich von Würzburg and Abbot Erkanbald von Fulda . It can be assumed that they kept their promise to repair the damage at their own expense after a pardon.

However, Hezilo undisputedly retained his property around the Peterstirn castle hill , where Eila founded a nunnery below the castle around 1015 . After a few changes of ownership, the women's monastery was converted into a Benedictine monastery called Stella Petri (in German Peterstern ) around 1055 , which in the course of time became Peterstirn .

High Middle Ages

Extinction of the margraves

Hezilos son Otto von Schweinfurt was from King Heinrich III. (1039-1056) appointed Duke of Swabia (Otto III.). One of his numerous daughters, Judith von Schweinfurt , became a central figure in the history of the old city of Schweinfurt, in which historical traditions and legends are combined . She is said to have become Queen of Hungary in her second marriage and found her final resting place in St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague .

Otto von Schweinfurt married a daughter of Margrave Ulrich Manfred von Turin (Manfred von Susa ) for reasons of imperial politics, with which connections between the kingdoms north and south of the Alps should be strengthened. After Otto, the male line died out in 1057 and this year at the latest marks the undisputed end of the important role of the Margraves of Schweinfurt . Otto's daughter Beatrix inherited the estate around Schweinfurt. The property at that time consisted of the castle on the Peterstirn and the village, which was between Höllental and Marienbach , with the former Kilian's Church ( see: Kiliansberg ). Beatrix's last male descendant, the prince-bishop of Eichstätt Eberhard I. von Hildrizhausen , bequeathed his property around Schweinfurt to the Hochstift Eichstätt in 1112 . As a result, the city came under spiritual rule until it became a free imperial city. In 1263/65 the run-down Benedictine monastery on the Peterstirn was handed over to the Teutonic Order at the instigation of the Würzburg bishop Iring von Reinstein-Homburg .

Ascent to the imperial city

At the beginning of today's old town from the 12th century , 1 km down the Main (west) of the old town , there are different views. Which range from a gradual construction to a planned Civitas Imperii ( imperial city ), i.e. a founding city , by Emperor Friedrich I Barbarossa , using existing royal property . The classic medieval city layout, with a cross on the market square, four quarters and four city gates, is, however, more clearly structured than most other medieval German cities and shows that it was built according to plan. At this new location in the city, the ford across the Main and the roads to Frankfurt, Obermain and Erfurt could be better controlled.

First city ruin and city rights

In the struggle for dominance in Main Franconia between the Hennebergers and the Bishop of Würzburg , the city was destroyed between 1240 and 1250 ( first city ruin ). However, it is controversial whether this destruction still took place in the old settlement between Höllenbach and Marienbach and thus was a reason for the rebuilding of the city at the current location further west or whether the destruction already took place here. In a letter from King Wilhelm of Holland of January 9, 1254, it is said that Schweinfurt was formerly an imperial city (... Swinforde, que olim imperii civitas fuerat) . It remains unclear whether rights were ever withdrawn from the city or whether reference is only made to city destruction. However, this letter is the first documentary evidence of Schweinfurt as an imperial city and thus also as a place with city rights .

Late Middle Ages

Hennebergisches Schweinfurt

|

|

|

|

Location map of Grafschaft Henneberg around 1350, with Schweinfurt (SW, bottom left)

|

St. Johannis, Gothic font (1367)

|

The first (inner) city fortifications of the new city were built, the course of which in the south along the Main and in the east along the valley of the Marienbach is identical to later fortifications, which are largely preserved in the Mariental today. This first city wall is mentioned for the first time in a comparison of February 17, 1258 between the Count of Henneberg and the Würzburg Bishop Iring von Reinstein-Homburg .

Around 1200 the construction of the Johanniskirche began in the new town , the oldest surviving structure in Schweinfurt and a cemetery was laid out around it. In 1237 the north tower was completed, the south tower was dispensed with.

In 1263 the monastery in the former margravial castle was converted into a commander of the Teutonic Order . In 1282, Schweinfurt was confirmed as an imperial city by Rudolf von Rudolf von Habsburg (1273–1291). In 1309, Schweinfurt was pledged to the Hennebergers, who maintained an imperial castle in the Zurich district from 1310 to 1427 . The danger of becoming permanently alienated from the empire could only be averted through self-indulgence (1361/1385) with great financial sacrifice. After the release, the city joined the Swabian Association of Cities .

As a result, numerous royal privileges strengthened the municipality in legal and economic terms. In 1397, King Wenceslas (1376–1400) granted permission for hydraulic structures and a bridge over the Main, and in the same year acquired the privilege of being exempt from customs duties . The right to hold an annual fair, which should begin on November 11th and last 17 days, acquired the city in 1415 from King Sigismund (1411-1437).

Building a territory

|

In 1436 the old fishing settlement Fischerrain , which borders the city wall to the south-west and whose origins lie in the dark of history, was incorporated into the city. Due to the positive economic development, the city was able to acquire the southwestern suburb of Oberndorf from the brothers Karl and Heinz von Thüngen on February 26, 1436 for 5,900 guilders. In 1436/37 the city council received the castle on the Peterstirn and the associated land area with the villages of Altstadt , Hilpersdorf , Zell and Weipoltshausen and the courtyards Deutschhof and Thomashof from the Teutonic Order for 18,000 guilders . This also included the two exclaves Ottenhausen and Weipoltsdorf . Madenhausen was added to the imperial city territory in 1620 . The inhabitants of these places were subjects of the imperial city and as a rule had no citizenship . As a result of the acquisitions, the territory of the imperial city now had an extension of 17 km from southwest to northeast. This resulted in an almost continuous Protestant corridor from the city of Schweinfurt via the knightly canton of Baunach through the Hochstifte Würzburg and Bamberg to the Protestant Duchy of Saxony .

Early modern age

The Franconian Reichskreis (original name: Reichskreis number 1 ) was constituted in 1517. The first district assembly took place in Schweinfurt.

Peasants' War

Since April 1525, the territory of the Würzburg bishopric had been almost entirely in the hands of rebellious farmers. The city of Schweinfurt took their side and supported them with teams and food. On May 17, 1525, the Mainberg Castle of Count Wilhelm von Henneberg was destroyed by the Bildhäuser Haufen . The army of the Swabian Confederation had recaptured the Würzburg area from the rebels at the beginning of June and arrived in Schweinfurt on June 12, 1525 with 15,000 men. The city was forced to terminate its alliance with the rebels and had to pay 4566 guilders for the reconstruction of Mainberg Castle and 10 Rhenish guilders per house for general pillage.

Second city ruin

On May 22, 1553, Schweinfurt was occupied for the first time by Margrave Albrecht II Alcibiades in the so-called Second Margrave War. From June 1 to 23, 1553 it was besieged and fired for the first time by the troops of Braunschweig , Saxony and Würzburg (also with the participation of Reisigern from Neustadt an der Aisch on June 17) . The big attack on the city took place the following year from March 27, 1554. The federal troops shot the city ready for storm within ten weeks and starved it to death. On the evening of June 12, 1554, the margrave had his troops withdraw from the overwhelming odds of his opponents. This left the city without protection. Before the council could begin negotiations with the federal troops, the city was plundered and set on fire on the morning of June 13, 1554. The population, already decimated by hunger and epidemics, fled in droves into the surrounding area.

The revenge-minded rural population, who suffered a lot in the war and blamed Schweinfurt, penetrated the city on the same day after the withdrawal of the federal troops and completed the work of destruction. This went down as the second city ruin in the city's history (see: First city ruin and city rights ).

The reconstruction dragged on until 1615. With the exception of the fortifications that were later modernized, the old town remained almost unchanged in this form until the early 19th century . Only in the 18th century were many two-story town houses added one floor. Certificates of reconstruction after the Second city of Destruction are the Renaissance facilities warehouse town hall , Altes Gymnasium and armory and the reconstructed Ebracher courtyard and the courtyard Metzger Gasse 16 .

Reformation and Thirty Years War

In 1542 Schweinfurt joined the Reformation and in 1609 the city joined the Protestant Union (see Evangelical Lutheran ). " Schweinfurt keeps getting caught between the fronts of major politics - as a pioneer of the Reformation since 1542 in the heart of the Catholic heartland, the city has, so to speak, chosen the status of the focal point itself." Through the Counter Reformation from 1585 to 1603 in the Diocese of Würzburg , Diocese of Bamberg and Diocese Fulda , many wealthy Protestant families turned to Schweinfurt. The most prominent among them was Balthasar Rüffer , Lord Mayor of Würzburg from 1585 to 1587 .

During the Thirty Years' War , Schweinfurt was frequently occupied by the troops of the warring parties. In 1632 the Swedish King Gustav Adolf came to the city. The Field Marshal of the Swedish army Karl Gustav Wrangel established his headquarters in Schweinfurt on Ross market. In the 1640s, Wrangel's city wall was expanded into a modern fortification. The fortifications on the Upper Wall have been preserved from this time. When the Ernst-Sachs-Bad was converted into the Schweinfurt art gallery, part of Wrangel's natural healing hill was found, which was integrated into the exhibition rooms ( see: Architecture / Schweinfurt art gallery ). In the Thirty Years War the city was not destroyed and hardly damaged. The two best-known ( opposite ) images of the imperial city come from the time immediately after the Thirty Years' War.

Attempt to found a university

The imperial city of Schweinfurt was a humanistic and Protestant island within the Würzburg monastery and in the vicinity of the Bamberg monastery , on which there was enormous political pressure. Almost a hundred years after the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina (now the National Academy of Sciences) was founded in Schweinfurt in 1652 , the last witch burning took place in Würzburg.

On the instructions of the Swedish King Gustav II Adolf , the Gustavianum grammar school , today's Celtis grammar school , was founded in Schweinfurt in 1632 . In addition, Gustav Adolf wanted to found a university in the city as a Protestant antithesis to the Würzburg monastery. During the Thirty Years' War he took land from the bishopric and donated it to the imperial city to finance the elite school. The plan was ultimately thwarted by his death in 1632 in the battle of Lützen .

In 1656 the imperial knighthood of the knightly canton of Rhön-Werra , with its office in Schweinfurt, became the largest Franconian knightly canton.

18th century

In the 18th century there were no armed conflicts in the imperial city. However, she often had to suffer from the passage of various troops who were fed, equipped or financed. The economic upturn was severely hampered by financial burdens, legal overregulation and corruption of the city council. The important local viticulture was pushed back in 1760 by the introduction of coffee in the city. From 1770 to 1772, the Würzburg monastery surrounding the imperial city imposed a fruit barrier over Schweinfurt, which led to an increase in prices. At the end of the 18th century, the city council, worried about losing its importance, rejected the request from Vienna to move the Imperial Court of Justice from Wetzlar to Schweinfurt. Which led to popular protests.

The year 1777 marked the beginning of industrialization of the city, with the establishment of a white lead mill by J. W. Schmidt. Other factory-like systems of this type were built on Bellevue and in the neighboring suburb of Niederwerrn .

Late modern times

Kingdom of Bavaria

Through the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss , Schweinfurt came to Bavaria in 1802 , three years before the Kingdom of Bavaria was founded. Lieutenant Colonel Joseph von Cloßmann took possession of the city for Bavaria on September 6, 1802. 4,000 people demonstrated against the Anschluss at Roßmarkt.

After belonging to the Grand Duchy of Würzburg (1810–1814), Schweinfurt fell to the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1814. The villages of Oberndorf , Zell , Weipoltshausen and Madenhausen belonging to the imperial city territory were spun off. As a result, Schweinfurt lost about two thirds of its territory.

In 1852, with the opening of the Ludwigs-Westbahn from Bamberg to the city station, it was connected to the railway network. As a result, the area of the city's first settlement was rebuilt after 700 years. The railway line was then expanded to Würzburg (1854) and Aschaffenburg . With the construction of the lines to Bad Kissingen (1871) and Meiningen (1874) Schweinfurt became a railway junction . In 1874 a large marshalling and central station was built 3 km west of the city station , today's main station . Then the branch lines to Kitzingen with the Schweinfurt Sennfeld train station and to Gemünden were added. However, unlike its neighbors Würzburg and Gemünden, Schweinfurt did not develop into a railway town . As an employer, the railway always played a subordinate role, which has had a positive effect on the cityscape to this day. The Centralbahnhof was laid out in a far-forward manner in the midst of fields on Oberndorf's municipal area as a passenger and goods station when the city had barely outgrown the medieval walls. With the aim of leaving as much space as possible for the expected industrialization around the station, which had taken place here until the end of the 1930s. The relatively large distance from the Central Station to the city center was bridged from 1895 with Bavaria's first municipal tram, the Schweinfurt tram , a horse-drawn tram . In 1906 the Centralbahnhof was renamed Hauptbahnhof .

|

|

|

|

Fichtel & Sachs AG Plant 1, Schrammstrasse 1913; from 1929 VKF, eastern part of the factory

|

Western inner city

justice building and Schillerplatz 1915 |

Due to the industrialization between 1840 (7,700) and 1939 (49,700 inhabitants) Schweinfurt had the second highest population growth of all Franconian cities with 635% after Nuremberg . Street and bridge names, such as Luitpoldstrasse , Maxbrücke and Ludwigsbrücke , are still reminiscent of Schweinfurt's time in the Kingdom of Bavaria . Before the outbreak of the First World War , a military training area was set up in the city forest, north of what is now the Deutschhof district , which was never used as a result of the outbreak of war.

Interwar period

After the proclamation of the Munich Soviet Republic in 1919, there were exchanges of fire in Schweinfurt with some dead. In 1921 the operation of the Schweinfurt tram was stopped as a result of the crisis after the First World War and replaced by regular buses from 1925. In contrast to many other cities, the 1930s were one of the most important epochs of urban development in Schweinfurt. The number of employees in the large metal processing companies rose to 20,700 by 1939. This led to a building boom and the course for modern urban development was set. The city planning from the 1920s for a new, extensive development along Niederwerrner Straße was modernized and the city was built on with residential areas in the northwest and with facilities for large-scale industry in the southwest. In the interwar period, the St. Josefs Hospital of the Catholic Redeemer Sisters (1929), the Municipal Hospital (1930), the Ernst Sachs Bad (1932), the headquarters of Fichtel & Sachs AG (1933) and the Willy were built Saxon Stadium (1936). Schweinfurt has been a garrison town since 1936. As part of the armament of the Wehrmacht operated by the Nazi regime , the large tank barracks were built on Niederwerrner Strasse .

See also: Schweinfurt industrial history

Second World War (Third Ruin of the City)

Schweinfurt (checkered hatching in the German center) the only primary target (was Primary ) Allied in Bavaria

The aerial warfare over Schweinfurt was different from the other cities. The attacking bomber units suffered unusually high losses. The local warehousing bearing industry was a key industry , as no tanks can drive or fly planes without bearings. Albert Speer , Reich Minister for Armaments and Munitions from 1942 , said that if the Schweinfurt industry had failed, the war would have ended two months later. The city therefore had the best air defense in Germany. The railway flak , batteries of heavy flak on wagons , was u. a. Posted on the railway line to Erfurt west of the city, at an air base , the later Conn Barracks .

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) suffered their greatest losses in aerial battles over the city. In total, 40% of the city and 80% of the industrial area were destroyed in 15 larger and seven smaller air strikes, which is known as the Third City Ruin ( see also: Second City Ruin ). However, unlike in many other German cities, there was no firestorm .

After the devastating failure of the air defense during Operation Gomorrah in the summer of 1942 against Hamburg , the German air force command had given up its resistance to new weapons. Air-to-air missiles were used for the first time in large numbers over Schweinfurt . The first air attack by the Allies took place relatively late, due to the location of Schweinfurt in the center of Germany and the long, dangerous approach routes of the Allied bomber units, without the protection of fighter planes , which was not technically or logistically possible. On August 17, 1943, the aerial warfare over Schweinfurt began as part of USAAF's Operation Double Strike with 376 bombers. 36 bombers were shot down and 122 damaged.

Black Thursday

The second attack on October 14, 1943 led the USAAF into a catastrophe; it suffered its greatest air defeat over Schweinfurt. The day later went down in American Air Force history as Black Thursday . Of a total of 291 bombers in this attack, the US 8th Air Force lost 77 B-17 bombers and another 121 were hit so badly that they could no longer be used. With 600 dead, there were far more victims among the bomber crews than among the civilian population. After that, attacks on Schweinfurt were feared by the Allied bomber crews. The largest attacks took place on February 24 and on the night of February 25, 1944 as part of Big Week with a total of 1,100 bombers in three individual attacks , with the USAAF always flying their attacks during the day and the Royal Air Force at night. The suburbs of Sennfeld and Grafenrheinfeld were also more severely damaged.

The civilian population, excluding forced laborers and prisoners of war , died in the air strikes 1,079. Schweinfurt was one of the 56 German cities in which there were bunkers . In 1940 about 14 bunkers were planned here (A 1 to A 14), ten of which were built. There were no fatalities in them in any air raid.

Since 1945: Americans in Schweinfurt

US garrison in Schweinfurt 1945–2014

On April 11, 1945, the 42nd Division of the 7th US Army marched into the city from the west and southwest, after being shelled by artillery for two days . The next day the American President Franklin D. Roosevelt died and the Americans held a great funeral service in front of the destroyed Kilian's Church in the city that same day . The Americans immediately occupied the air base on the city limits, the later Conn Barracks , confiscated offices and houses, took over the tank barracks and renamed them Ledward Barracks in 1946 . Here also the headquarters of the garrison, which was the headquarters of the US A rmy G arrison ( USAG ) Schweinfurt furnished. The America House was opened in May 1948 . In the 1960s, the on- site practice area was set up at Brönnhof .

In the Cold War USAG Schweinfurt had the highest concentration of US combat units in West Germany . The American residential area Askren Manor was built in the 1950s and the officers' residential area Yorktown Village was built around 1990 . Until the late 1990s, a civil infrastructure was gradually built up that corresponded to that of a small American town. At times the US military community in Schweinfurt comprised 12,000 people, including around 5,000 soldiers and over 7,000 family members and civilian employees. As a result of the closure of many other German US locations, areas were relocated to Schweinfurt and this location became one of the largest in Europe. From the 1990s onwards another billion US dollars were invested in the Schweinfurt location.

social change

Since the 1990s, the image has changed significantly compared to the conventional idea of a US location and USAG Schweinfurt has become more civilized. The military service was abolished in the United States already 1973rd With the professional soldiers came many family members, who in the end were in the majority. In addition, one noticed the social change in the USA towards a more multicultural society with more colored people, Latinos and Asians. Americans brought a multicultural enrichment, with a, compared to other cities, more exotic event and discotheque scene (see: Nightlife ). In addition, due to globalization and subcultural change in fashion and lifestyle since the 1990s, differences between young Americans and Germans, especially those with a migration background , were hardly noticeable in the city.

US conversion

On February 2, 2012, Schweinfurt's Lord Mayor Sebastian Remelé announced after a conversation with Mark Hertling , Commander in Chief of the US Armed Forces in Europe , that the US Army would completely dissolve the garrison in Schweinfurt. Because the restructuring of the US armed forces is a relocation of heavy troops from Europe back to the USA. With small exceptions, the properties freed up as a result became the property of the Federal Agency for Real Estate Tasks (BImA). Due to its size, the US conversion in Schweinfurt is one of the Federal Agency's five most important projects in Germany. The US Army left Schweinfurt on September 19, 2014, with the ceremonial collection of the flags in the Ledward Barracks. USAG Schweinfurt covered areas of 29 km² with a wide variety of buildings: hangars , warehouses, residential complexes, single-family houses, schools, churches, clinics, department stores, gas stations, cinemas, bowling centers, event and sports halls.

On February 26, 2015, the city acquired the Ledward Barracks from the BImA, with an area of 26 hectares. a. An initial reception facility for asylum seekers will be housed, which will then be replaced by an anchor center in the Conn Barrack, in the suburb of Niederwerrn , which should exist until 2025 at the latest . The Ledward barracks is currently (2018) being converted into the new Carus Park district . The main user will be the University of Applied Sciences Würzburg-Schweinfurt (FHWS), with an international university campus, the i-Campus Schweinfurt . On February 29, 2016, the city acquired three more conversion areas totaling 48 hectares from the BImA: the former US housing estate Askren Manor, for the development of the new Bellevue district , the former US officers' housing estate Yorktown Village , whose semi-detached houses were raffled among 800 prospective customers in 2016 and Kessler Field , where the Mainfranken International School moved into the former US high school in 2016 . The areas of Heeresstrasse in the city area were also transferred to the city of Schweinfurt by the BImA. The city had thus acquired a total of around 94% of the former US land in the city. The Brönnhof training area, located outside the city, was the third largest US Army training area in Europe at 26 km², and in 2016 it became the largest national natural heritage site in Bavaria.

In 2016, the final point in the now 71-year post-war history of the city was set.

Schweinfurt in the mirror of world history

In the Second World War the Americans suffered their greatest defeat in the air over Schweinfurt (see: Schweinfurt, Second World War ). The Cold War was clearly audible in the western city area, as the local location had the highest concentration of US combat units in West Germany . After the fall of the Iron Curtain and the supposed end of history , the situation changed fundamentally. In the Ledward Barracks the controls were completely lifted and every German could freely use the civil American facilities (bars, cinema etc., except PX ).

The terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 changed the situation suddenly. Barriers with massive checkpoints (security gates) were built around all US facilities, including American residential areas . The German-American folk festival was discontinued (see also: US Army Garrison Schweinfurt, September 11, 2001 ).

Many US soldiers stationed in Schweinfurt were drafted into wars: from the 3rd Infantry Division in 1990 and 1991 to Iraq and Kuwait and from a later division in the Iraq War 2003. In the Conn Barracks , tanks were loaded onto the railroad for the wars . Soldiers stationed in Schweinfurt died in the wars. In the west of the city one saw war-wounded US soldiers on crutches in the completely unfamiliar picture.

World events in the city were also reflected outside the USAG Schweinfurt: As a result of the nuclear disaster in Fukushima in 2011, the Grafenrheinfeld nuclear power plant not far from the city limits was shut down prematurely in 2015. As a result of the civil war in Syria , an initial reception center was set up (see: US conversion ).

Since 1945: German history

The city's history between the Second World War and the present was very structured, with three mayors who were each in office for 18 years. The first shaped the post-war period , the second an intermediate phase with new challenges and the third led the city to unimagined shores.

The Wichtermann era 1956–1974

A quick, planned reconstruction of the city was not necessary due to the degree of destruction of 40 to 45%, but it dragged on over several stylistic epochs, even today (2018) the last vacant lots are being closed. So Schweinfurt was spared a dreary post-war cityscape (see: Cityscape ), i. Ggs. To neighboring Würzburg or for example Hanau , Heilbronn , Hildesheim or Pforzheim .

Like many other West German cities, Schweinfurt experienced an unprecedented economic miracle in the 1950s and 1960s and large-scale industry boomed. To counteract the labor shortage, southern Europeans, mainly from southern Italy and later from eastern Anatolia, were recruited as guest workers from 1960 onwards .

Most of the post-war construction projects were carried out under the aegis of Mayor Georg Wichtermann (SPD) in the city ruled by the SPD with an absolute majority. Numerous new districts emerged: Bergl (from 1950), Musikerviertel -West (from 1950), Steinberg (from 1955), Hochfeld (from 1956), Haardt (from 1972) and Deutschhof (from 1972). In 1964, the so-called Blue Skyscraper , also by SKF, was completed at the same time as the SKF administration high-rise (see picture at the beginning of the article) . With 25 storeys, it was initially the tallest residential high-rise in Germany and at 73 m higher than the highest completed high-rise in Frankfurt am Main . After 1973, no more high-rise residential buildings were built. The jump over the Main (from 1963) created the Hafen-Ost industrial park and the new Hafen-West industrial area south of the Main .

The infrastructure was expanded: New Town Hall (from 1954–58, under monumental protection ), new Volksfestplatz (1958), summer pool (1958), Friedrich-Rückert-Bau with adult education center and city archive (1962), Mainhafen (1963), Theater der Stadt Schweinfurt (1966, under monument protection), University of Applied Sciences Würzburg-Schweinfurt (1971) and Bildungszentrum-West (1974).

The Petzold era 1974–1992

After the reconstruction and the boom years, this time was marked by the oil crisis and recessions , with job cuts in the local large-scale industry. In the city, despite the continued positive migration balance , there was a decline in population as a result of an enormous birth deficit , as everywhere in Germany. This interim period in urban development was under the aegis of Mayor Kurt Petzold (SPD) and was characterized by consolidation.

The renovation of the old town began in 1979, initially in the old commercial district , as the starting point of a 40-year-long redesign of the city that has continued to this day, with a successful image change from the gray-mouse industrial city to a city with a high quality of life . In 1981 the large city clinic Leopoldina Hospital was opened, in 1982 the previous, historic pedestrian zone Kesslergasse was expanded to include Spitalstrasse, from 1984 the new Eselshöhe district built, from 1988 the city wall restored, and finally from 1990 the joint power station Schweinfurt (GKS) built.

Social upheavals

Since the 1970s, many younger families and also long-established citizens left the narrow political boundaries of the city and moved to the suburbs, creating a bacon belt . The development of new residential areas shifted from the core city to the suburbs in the course of suburbanization . The core city was now increasingly determined by segregation , in conjunction with the declining German population as a result of demographics . In the inner-city and western residential areas, which no longer met the new, high demands, there was often an exchange of people. Migrants moved into cheap, vacant apartments and there were no vacancies. As a result, in addition to the bourgeois quarters in the north and east of the city, ethnically influenced quarters in the west, such as Turkish - Muslim quarters (e.g. Wilhelminian style ) or, as an exception in the bourgeois northeast, a Russian-German quarter in the core of the Deutschhof . There were also American neighborhoods and residential complexes (see: Americans in Schweinfurt ). As a result, quarters of the most diverse ethnic groups emerged, as in very large cities. Since the 1990s, information boards in the city have been in four languages: German, English, Turkish and Russian. Heilmannstrasse from the early 1950s, on the southern part of the mountain , degenerated into a ghetto and, like some other places, a no-go area and was finally completely demolished and re-planned.

Although the number of Turks within the narrow city limits rose to 3,000, they formed i. Compared to many other larger German cities, only the third largest ethnic group, after Americans and Germans from Russia. Today the proportion of people with a migration background in the core city is almost 50%. It stands in unprecedented contrast to the bacon belt and the surrounding area, which is more bourgeois than in many places and is a center of Franconian customs and tradition .

The Grieser era 1992–2010

In the city dominated by the SPD, the CSU succeeded in appointing the mayor for the first time in 1992, with the politically unspent Gudrun Grieser , who only joined the CSU shortly before her election. The then Bavarian Prime Minister Edmund Stoiber (CSU) supported this historic change of power. As a countermeasure to the severe crisis in large-scale industry around 1992 (see: Phönix aus der Asche ), the Free State of Bavaria now strengthened the service sector . Parts of the Bavarian State Social Court and the Bavarian State Office for Statistics were relocated from Munich to Schweinfurt.

During Grieser's tenure, the economic situation stabilized from the mid-1990s, 4,500 new industrial jobs and around 6,000 jobs in the service sector were created, which ultimately led to a boom phase from 2005 to 2008 until the global economic crisis in 2009 . The business tax revenue rose to record levels and the city could save up reserves in the tens of millions.

In the Grieser era, the new motto of the city of Industry and Art was developed. A large number of projects, in cooperation with the then construction consultant Jochen Müller (SPD), gave the city a new face, set new, nationally recognized signals in architecture and were honored with numerous architecture prizes. Which resulted in a change in the city's image.

The following projects were implemented in the Grieser era: the start-up, innovation and advice center Schweinfurt (GRIBS) (1994), the new Maintal industrial and business park (from 1995), the new junction 6 Schweinfurt-Hafen of the A 70 , the redesigned Roßmarkt (1997), the Vehicle Academy (1998), the Bavarian State Office for Statistics (1998), the Georg Schäfer Museum (2000), the branch of the Bavarian State Social Court (2000), the Maininsel Conference Center (2004), the restoration of the Schweinfurters City wall Am Unteren Wall, the city library in the Ebracher Hof (2007), the art gallery Schweinfurt (2009), the city gallery Schweinfurt (2009), the redesign of the Weststadt (2009), the health park Schweinfurt (from 2009), the campus 2 of the university for applied sciences , the DB-Halt Schweinfurt-Mitte, the youth hostel (2009) and the first section of the redesign of the Main bank east of the Maxbrücke (2010).

The Grieser era continues to shape the cityscape like no other epoch since the reconstruction after the war and changed the city's image permanently.

present

Under the new Lord Mayor Sebastian Remelé (CSU, since 2010), trade tax revenues rose to a new record high of 60.462 million euros in 2013. The city was able to save higher reserves. These are currently being used for the major US conversion project (see: US conversion ).

In addition, the Neue Hadergasse was realized in 2014 . A business and residential quarter on the base of a new underground car park on the western city wall, with a hotel, on a large vacant lot from the Second World War . In addition, instead of a demolished complex from the 1950s, the Krönlein-Karree (also: City-Karree ) on Georg-Wichtermann-Platz was completed in 2017 as the entrance gate from the city to the old town . The Riedel Höfe and the Luitpold-Terrassen in the Wilhelminian style quarter and the residential complex An den Brennöfen in the old town quarter of Fischerrain will be almost the last major, war-related gap closings in 2019.

Thus 74 years after the Second World War, with the exception of a larger wasteland in the Hadergasse in the old town , the reconstruction of the city will be finally completed. Currently (2018) the demolition work on part of the New Town Hall, the so-called Stadtkasse, begins . A seven-storey new town hall is being built here.

Further major projects are currently being planned, such as the reorganization of the Leopoldina Hospital area, and the like. a. through a large car park and the reorganization of municipal museums through the Kulturforum Martin-Luther-Platz .

additional

Desolation

Several devastations are documented within the present urban area . South of the Main , on Oberndorfer district, near the Schweinfurt-Sennfeld train station, was the village of Leinach, which perished in the 16th century . Schmalfeld , which was abandoned in the 13th century, was only a few hundred meters down the Main . The Schmachtenberg desert is located on the southern edge of the urban area at the Schwebheimer Wald . After Schmachtenberg was abandoned in the 15th century, the residents probably settled at the so-called Senftenhof , which existed until the 17th century. On the road from Schweinfurt to Niederwerrn , near the settlement An der Schussermühle , which has been called Bellevue since 1830 , the villages of Affeltrach and Hilpersdorf were once located . Hilpersdorf was mentioned in the document of June 29, 1282 in a dispute between the Teutonic Order and the imperial city of Schweinfurt. The city of Schweinfurt acquired it in 1437. The village was destroyed in the Thirty Years War . In 1661 the ruins of the church disappeared as the last remnant.

Incorporation and revisions

In 1436/37 the villages of Oberndorf , Zell and Weipoltshausen and in 1620 Madenhausen became part of the imperial city of Schweinfurt ( see building a territory ). When in 1802 Schweinfurt came to Bavaria through the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss , the city-state was dissolved and all four villages were spun off from the city.

On December 1, 1919, Oberndorf was incorporated again. The Oberndorfer district borders on the city center (Landwehrstraße) and includes the old town as well as the main station , the Bergl district and by far the largest part of today's urban area south of the Main . In 1919, the majority of large-scale industry was located in Oberndorf and today all of Schweinfurt's large-scale industry is located on it, with the exception of the SKF administration high-rise . Oberndorf was incorporated because it could no longer guarantee the water supply for the industry despite the construction of a large water tower (1911).

During the Bavarian territorial reform , the state government had already decided to incorporate the suburbs of Dittelbrunn , Niederwerrn and Sennfeld . The decision was reversed by order of State Secretary Erwin Lauerbach . Since the city had no expansion areas for its large-scale industry in the south, Grafenrheinfeld had to cede an unpopulated 2.4 km² area to the city of Schweinfurt on May 1, 1978. It is the southern part of today's industrial and commercial park Maintal . As a result, Schweinfurt became the smallest independent city in Germany, while the city ranks 44th out of a total of 110 independent cities in terms of population density with 1,477 inhabitants per km² (2016) and is more densely populated than 30 large cities. Statistically, Schweinfurt cannot therefore be compared with other German cities, as almost all values are distorted. This fact is unknown in the national media, which is why incorrect conclusions are usually drawn from local statistics. For example, the neighboring Bad Kissingen, which is known to be preferred by pensioners, is not named as the city with the most German senior households, but Schweinfurt, with a share of 53%.

See also: Population development of Schweinfurt

Place name

The Latin name Porcivadum corresponds to a ford suitable for pigs . The humanist Johannes Cuspinian , who comes from the city, traces the name back to a ford for pigs. As a result of later findings, however, this simple name derivation became increasingly unlikely (see: Origin of the city name ).

Friedrich Rückert commented on the name of his hometown in his youth poem The Visit to the City :

- "If you had Mainfurt, if you had Weinfurt,

- Because you lead wine

- Can be called, but Schweinfurt,

- It should be Schweinfurt. "

Decades later he came back to it with the following poem, with which he thanked Karl Bayer (1806-1883), a grammar school professor who was associated with him from his time in Erlangen and who worked in Schweinfurt from 1862, for his congratulations on his seventy-fifth birthday on May 16, 1863:

- "May sixteenth glory is full of May,

- On the seventeenth it is drawing to a close.

- On the sixteenth he still has a few steps to climb

- Up to the summit, steps sprinkled with roses.

- Before and after in May other poets were born,

- On the sixteenth alone I believe I was born.

- If I praise one thing, I praise another: not just born

- I am in the middle of May, also in the middle of the Main.

- From Jean Paulschen Bayreuth to Goethe's Frankfurt

- Is he in the middle of the run where the Main was born to me.

- Mainfurt should therefore be called my hometown;

- It is called Weinfurt without the hissing in front of it. "

useful information

Earliest printed puppetry text from 1582

The puppeteer Balthasar Klein from Joachimsthal visited the city in 1582 and had the text A funny, short and no less useful game printed from the penitential sermon Jone des Prophet zu Niniue . This font is the oldest printed puppetry text and is of great importance for theater research . The only surviving copy was found in the library of the University of Krakow .

See also

- Schweinfurt industrial history

- Benedictine monastery Schweinfurt

- Carmelite Monastery Schweinfurt

- Old town (Schweinfurt)

- Zurich (Schweinfurt)

- Fischerrain

literature

- Thomas Horling, Uwe Müller, Erich Schneider: Schweinfurt: Small city history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2609-0 .

- Andreas Mühlich, G. Hahn: Chronicle of the City of Schweinfurt - Compiled from various manuscripts. Nabu Press, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-1-247-00419-8 .

- Heinrich Christian Beck : Chronicle of the city of Schweinfurt . British Library, London 2011 ISBN 978-1241415693 .

- Heinrich Christian Beck: Address book of the city of Schweinfurt - With representation of the main moments of its history and an overview of the sights . Schweinfurt 1846 ( e-copy ).

- Heinrich Christian Beck: Chronicle of the city of Schweinfurt

- Michael Sirt: Reformation history of the imperial city - reprint of the edition from 1794. Hansebooks, Norderstedt 2016, ISBN 978-3-7434-1143-2 .

- Johannes Strauss (Hrg), Kathi Petersen (Hrg): Streiflichter on the church history in Schweinfurt - Writings for the 450th anniversary of the Reformation in Schweinfurt . Verlagshaus Weppert, Schweinfurt 1992, ISBN 3-926879-13-0 .

- Friedrich L. Enderlein: The Imperial City of Schweinfurt - During the last decade of its imperial immediacy with comparative views of the present. Hansebooks, Norderstedt 2016, ISBN 978-3-7434-1090-9 .

- Paul Ultsch: Back then in Schweinfurt - Volume 1 - When the city wall was still a boundary . Book and idea publishing house, Schweinfurt 1980, ISBN 3-9800480-1-2 .

- Paul Ultsch: Back then in Schweinfurt - Volume 2 - Development into an industrial city . Book and idea publishing house, Schweinfurt 1983, ISBN 978-3980048026

- Hubert Gutermann: Alt Schweinfurt - in pictures, customs and legends. Publishing house Schweinfurter Tagblatt, Schweinfurt 1991, ISBN 3-925232-09-5 .

- Friedhelm Golücke: Schweinfurt and the strategic aerial warfare 1943. (= Schöningh Collection on the past and present ). Paderborn 1980, ISBN 3-506-77446-8 .

- Edward Jablonski: Double strike against Regensburg and Schweinfurt - school example or failure of a large bomb attack in 1943. Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-87943-401-8 .

- Martin Caidin : Black Thursday: The Story of the Schweinfurt Raid. 1960. (English; story about the greatest American air defeat in World War II).

- Several authors: After the war no one was a Nazi - workers' movement in Schweinfurt between 1928 and 1945 . Verlag Rudolf & Enke, 2001, ISBN 3-931909-07-7 .

- Uwe Müller , Irene Handfest-Müller: Schweinfurt Turbulent Times - The 50s . Wartberg Verlag, Gudensberg 2002, ISBN 3-8313-1255-9 .

Web links

- Historical lexicon of Bavaria: History of the imperial city of Schweinfurt

- Peter Hofmann: schweinfurtfuehrer.de/Geschichte

- Video: The History Channel: 11-The Schweinfurt Raid. The Schweinfurt Disaster . First air raid on Schweinfurt (US Army Air Force) on August 17, 1943 (45:26)

- Video: chronoshistory: Flight over the destroyed Berlin (0:00 to 2:00) and the destroyed Schweinfurt (2:00 to 6:00; in color)

Individual evidence

- ↑ mainpost.de: The first Schweinfurt settlement was a fishing village, May 10, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Peter Hofmann: schweinfurtfuehrer.de/Geschichte. Retrieved March 8, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g geodaten.bayern.de Monument list Schweinfurt / soil monuments. (PDF) Retrieved November 24, 2017 .

- ^ Anton Oeller: The place names of the district of Schweinfurt. 1955, p. 52.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of Bavaria: Schweinurt, imperial city. Retrieved May 24, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d Dr. Wolf-Armin Freiherr von Reitzenstein, lecturer for Bavarian onomatology at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich . Treatise published by Michael Unrath in: Schweinfurtführer Mein Schweinfurt: Geschichte. Retrieved May 15, 2016 .

- ↑ Schweinfurt Heimatblätter: Article by Wilhelm Fuchs, 1957.

- ↑ a b c d e Karl Treutwein : Lower Franconia. P. 141.

- ^ First edition of the Romwegkarte, 1500, by Erhard Etzlaub

- ^ Heinrich Wagner: On the foundation of the Weissenburg and Echternach monasteries and their work in Mainfranken. In: Archive for Middle Rhine Church History. 55 2003, pp. 123 f., 127.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Schweinfurt | City | Culture | Topics. Publication of the Schweinfurter Tagblatt and special edition for the Handelsblatt and ZEIT: micro-arena of German history. May 20, 2009, p. 4 f.

- ↑ Fundamental to the development up to 1300 and as evidence for all information: Achim Fuchs: Schweinfurt. The development of a Franconian villula into an imperial city. (= Main Franconian Studies. 2). Wuerzburg 1972.

- ↑ a b c d e City of Schweinfurt information brochure. Weka Info-Verlag, Mering 2002, p. 5.

- ↑ Rudolf Endres: The role of the Counts of Schweinfurt in the settlement of northeast Bavaria. In: Yearbook for Franconian State Research. 1972, p. 7 and F. Stein: The Margravial House of Schweinfurt. P. 27 ff.

- ^ Peter Hofmann: The important role of the margraves of Schweinfurt from 973 to 1057. In: Schweinfurtführer. Retrieved December 12, 2016 .

- ^ Paul Friedrich von Stälin : Otto III., Duke of Swabia. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB), Volume 24. Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1887, p. 726 f.

- ↑ Several authors: Bikeline-Radtourenbuch Main-Radweg . Esterbauer Verlag, Rodingersdorf 2005, ISBN 3-85000-023-0 , p. 60.

- ^ A b Peter Hofmann: History of Schweinfurt from 1200 - 1300. In: Schweinfurt guide. Retrieved May 6, 2018 .

- ↑ Peter Hofmann: https://www.schweinfurtfuehrer.de/geschichte/1200-1300/ Geschichte Schweinfurt from 1200 - 1300. In: Schweinfurtführer.

- ↑ Overview of the files in the Würzburg State Archives with contents. ( Memento of the original from May 17, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c City map of Schweinfurt with history and sights, printing and publishing house Weppert, Schweinfurt 2003.

- ↑ Several authors: Great Atlas of World History . Lingen Verlag, Cologne 1987, map p. 79: Germany in 1648.

- ↑ a b Lower Franconian History, Volume 3. Echter Verlag Würzburg 1995.

- ↑ Max Döllner : History of the development of the city of Neustadt an der Aisch until 1933. Ph. CW Schmidt, Neustadt ad Aisch 1950. (New edition 1978 on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the Ph. CW Schmidt Neustadt an der Aisch publishing house 1828–1978. ) P. 197.

- ↑ a b Information brochure City of Schweinfurt. Weka Info-Verlag, Mering 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Heinrich Christian Beck: Chronicle of the city of Schweinfurt . Schweinfurt 1836–1841, Volume 1, section. 2, column 28.

- ↑ A brief history of the city of Schweinfurt. P. 40.

- ^ Historical lexicon of Bavaria: Imperial Knighthood of the Canton of Rhön and Werra. Retrieved January 3, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Peter Hofmann: 1700–1800. In: Schweinfurt Guide. Retrieved October 20, 2018 .

- ↑ Uwe Müller: Schweinfurt - from the imperial free imperial city to the royal Bavarian city. In: Rainer A. Müller, Helmut Flachenecker, Reiner Kammerl (eds.): The end of the small imperial cities in 1803 in southern Germany. Supplements of the magazine for Bavarian regional history, B 27, Munich 2007, 139-163; (Digital view)

- ^ TV Touring Schweinfurt, January 29, 2016.

- ↑ Bayer. State railways , expansion status until 1912.

- ↑ Werner Bätzing: The population development in the administrative districts of Upper, Middle and Lower Franconia in the period 1840–1999. In: Yearbook for Franconian State Research. No. 61, 2001, p. 196.

- ↑ mainpost.de: Troubled times and storming the Schweinfurt harmony, April 28, 2019. Accessed on April 28, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c Video (English 45:26): The History Channel: 11-The Schweinfurt Raid. "The Schweinfurt Disaster". First air raid on Schweinfurt (US Army Air Force) on August 17, 1943. Retrieved May 7, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c Michael Bucher, Rolf Schamberger, Karl-Heinz Weppert: How long do we have to live in these fears? Printing and publishing house Weppert, Schweinfurt 1995, ISBN 3-926879-23-8 , p. 42 f.

- ^ Federal Agency for Real Estate Tasks: Conversion Schweinfurt / History of the real estate. Retrieved June 17, 2018 .

- ^ A b Welt.de: The sinking of the US Air Force over Schweinfurt. Retrieved April 15, 2016 .

- ^ Second Schweinfurt Memorial Association. Black Thursday 10/14/1943. Retrieved April 15, 2016 .

- ↑ mainpost.de: “Memories of the bombing night”, February 26, 2019. Accessed on February 26, 2019 .

- ^ Peter Hofmann: Bunker. In: Schweinfurt Guide. Retrieved May 2, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c Information from the Federal Agency for Real Estate Tasks (BImA) in: History of the properties of the military site in Schweinfurt

- ↑ a b Ron Mihalko, Forst : History of the US barracks in Schweinfurt

- ^ Mathias Wiedemann: End of a 70-year neighborhood. In: Schweinfurter Tagblatt. 19th September 2014.

- ↑ Ron Mihalko, Forst : History of the US barracks in Schweinfurt

- ↑ Video: Reim Hart Nei 2 - Hip Hop Jam: Street scenes from the west of downtown Schweinfurt (2:48). Retrieved June 18, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Information from the Federal Agency for Real Estate Tasks (BImA)

- ↑ City grows by 48 hectares. In: Schweinfurter Tagblatt. 23rd December 2015.

- ↑ One of the best US locations in Europe. In: Main Post. Online edition, November 21, 2006.

- ↑ A soldier becomes a murderer . In: time online . ( zeit.de [accessed on October 18, 2016]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Information brochure City of Schweinfurt. Weka Info-Verlag, Mering 2002, p. 7.

- ↑ When it was completed in 1964, the 73 m high blue skyscraper was 5 m higher than the tallest skyscraper completed in Frankfurt am Main , the Zurich House

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Information brochure City of Schweinfurt. Weka Info-Verlag, Mering 2002, p. 8.

- ↑ mainpost.de: There is also racism in the multicultural city of Schweinfurt, March 21, 2019. Retrieved on April 3, 2019 .

- ↑ FOCUS: Poor city, rich city. A visit to the job paradise Schweinfurt and the debt stronghold of Oberhausen. Asg. No. 34, August 14, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2017 .

- ^ Bavarian State Office for Statistics and Data Processing, Statistics communal 2014.

- ↑ Heimatbuch Oberwerrn. Part 1, Niederwerrn 2006.

- ^ Wilhelm Volkert (ed.): Handbook of Bavarian offices, communities and courts 1799–1980 . CH Beck, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-406-09669-7 , p. 602 .

- ↑ Schweinfurt came away empty-handed during the regional reform. In: Schweinfurter Tagblatt. February 22, 2012.

- ^ Federal Statistical Office (ed.): Historical municipality directory for the Federal Republic of Germany. Name, border and key number changes for municipalities, counties and administrative districts from May 27, 1970 to December 31, 1982 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Mainz 1983, ISBN 3-17-003263-1 , p. 734 .

- ↑ rp-online: These are the German single cities. Retrieved May 4, 2018 .

- ^ Collected poems by Friedrich Rückert, fourth volume, Erlangen 1837, p. 285 books.google

- ^ Rückert-Nachlese , Volume 2, Gesellschaft der Bibliophilen 1911, p. 522 books.google

- ↑ Puppenspieltage.de. Retrieved January 23, 2016 .