Bad Tölz

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 47 ° 46 ' N , 11 ° 33' E |

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Bavaria | |

| Administrative region : | Upper Bavaria | |

| County : | Bad Toelz-Wolfratshausen | |

| Height : | 658 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 30.8 km 2 | |

| Residents: | 19,155 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density : | 622 inhabitants per km 2 | |

| Postal code : | 83646 | |

| Area code : | 08041 | |

| License plate : | TÖL, WOR | |

| Community key : | 09 1 73 112 | |

| City structure: | 15 parts of the community | |

City administration address : |

Am Schloßplatz 1 83646 Bad Tölz |

|

| Website : | ||

| First Mayor : | Ingo Mehner (CSU) | |

| Location of the city of Bad Tölz in the Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen district | ||

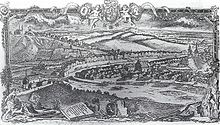

Bad Tölz (until 1899 Tölz ) is the district town of the Upper Bavarian district of Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen . The spa town is located on the Isar around 50 kilometers south of Munich and has a good 19,000 inhabitants. It represents the economic and cultural center of the Altlandkreis Bad Tölz and is known for its old town, the proximity to the mountains and the Tölzer Leonhardifahrt .

geography

location

The place is in the middle Isar valley , at the northern entrance to the Isarwinkel , from where you can see the Bavarian and North Tyrolean Limestone Alps . The district and spa town is about 650 to 700 m above sea level. NHN and is therefore one of the highest district towns in Germany . The state capital Munich in the north is around 50 kilometers away, Garmisch-Partenkirchen in the southwest is 56 kilometers away. The former district town of Wolfratshausen and Geretsried as further centers in the north of the Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen district are 25 and 20 kilometers away, respectively.

Bad Tölz is surrounded by the Tölz Moor Axis .

Community structure

There are 15 officially named parts of the municipality (the type of settlement is given in brackets ):

|

|

Neighboring communities

All neighboring communities are in the Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen district.

|

Dietramszell |

Sachsenkam |

|

|

Wackersberg |

|

Reichersbeuern |

|

Gaissach |

Greiling |

climate

history

Early history and the Middle Ages

From 550, Bavarians first settled in the area of the Ried, today's Mühlfeld, on the eastern bank of the Isar. In the 7th century these pagan Bavarians were converted to Christianity by Rupert von Salzburg , who also set up a St. Michaelis Baptistery there. This settlement, called Reginried, fell victim to marauding Hungarians . In addition to this settlement on the Mühlfeld, a second emerged with the Gries on the banks of the Isar, where mainly raftsmen , lime burners and other craftsmen settled. Above all, blacksmiths and wagons settled in the Ried , benefiting from the location on the Salzstrasse , from Reichenhall and Halle towards the Allgäu . From the 9th century onwards, many whetstone and sawmills were built there on the Ellbach , from which the name Mühlfeld refers.

Tölz was first mentioned in 1155 as "Tolnze". The name goes back to Hainricus de Tolnze (Heinrich von Tollenz), who came from a place near Pressath in the Upper Palatinate , today's Döllnitz . Documents from 1198 and 1202 also mention him as "Dominus Tolnzar de Hohenburc". Around 1180 he married Irmingard, the daughter of Gebhard von Hohenburg from the Richer family, who lived on the Hohenburg in Lenggries . Through his participation in imperial and state parliaments, Heinrich von Tollenz was regarded as a respected ducal fiefdom holder . In the area of today's parish church , he had the first Tölzer castle built from 1180 , next to it the church, first mentioned in 1262 as "Kapella Tolnze".

Ludwig I commissioned Heinrich with the further development of the Isarwinkel. As a result, the two settlement centers on Gries and Mühlfeld grew together, connected by the Sämerpfad, where mainly warehouses and inns were built. This Sämerpfad later became Marktstrasse, but was only given this name in 1624, when the place received a state salt office . According to Stephan Bammer, Marktstrasse was built according to plan in the 13th century.

Georg Westermayer , the author of the "Chronik der Burg und des Marktes Tölz", first published in 1871, for which he was granted honorary citizenship in 1879, mentions other origins of Tölz. According to Westermayer, the place goes back to a Roman settlement called Tollentium or, according to other sources, Tollusium . He also refers to Johannes Aventinus and his "Annales Bojorum Lips." As well as Karl Roth and his "Contributions to German language, history and local research", who mentions the early place names tholanza and dolanza . Furthermore, Westermayer described the Celtic settlement of the region. Finds and ground monuments testify to this Celtic ( e.g. the corona field near Gaißach, finds from the Hallstatt period ) and later Roman settlement of the area, the place name derives from the Celtic tol for valley. The historian Wilhelm Schmidt confirmed a Roman settlement . This existed at least since the time of Germanicus . This Roman settlement is said to have been an important junction on several Roman roads .

According to Westermayer, Hainricus de Tolnze did not come from the Upper Palatinate, but from Schäftlarn . He proves him to be a witness to a donation from Rudiger von Lindahe in 1180 and refers to mentions in a document from the Schäftlarn monastery from 1182, where he is also mentioned as Tolnzar with his knights . Other sources also speak against an Upper Palatinate origin, such as Stephan Glonner's “History Notes for the Isarthal”, which mentions family ties to former lords of Hohenburg, as well as Lang in his “Bavaria”, who assigned him to an old resident gender and his marriage to Bernhard the Younger von Weilheim names. Heinrich von Tollenz managed several castles and because of his reputation he accompanied Otto von Wittelsbach on his negotiating days. These first led him to the Upper Palatinate, to Amberg and Regensburg , next to the Counts of Wasserburg and Falkenstein . Heinrich von Tollenz was also in the favor of Emperor Heinrich VI. who mentions him as an "Upper Bavarian knight" among the appointed witnesses. Heinrich von Tollenz also met regularly with Ludwig the Kelheimer .

In his “Short History of Bad Tölz”, published in 2017, the cultural scientist Stephan Bammer doubts the thesis of Tölz's Roman origin. Westermayer relied too much on the assumptions of Aventinus. Bammer, on the other hand, also refers to the historian Josef Katzameyer, who is more critical of the source. The earliest mention of a place name related to "Tölz" can only be traced back to the 12th century, but in fact the origin is still to be found in the Reginried settlement. The place was mentioned as Reginpendetesried as early as 1073. The name refers to the clearing area (reed) of a Reginbrecht. At this time the place was subject to Hohenburg's rule. The name Reginried was used until 1214.

The oldest land register of the Duchy of Bavaria from 1240 does not mention Tölz and Hohenburg as landable villages of the Herzoghof, since both were still owned by the Tölz family. The Landurbar from 1281 describes Tölz as a "ducal office of considerable size" and names it as one of the most important of the 55 Bavarian offices. Around 1245 a feud broke out between Duke Otto II and Otto von Meranien . As Vogt of the monasteries in Benediktbeuern and Tegernsee, the latter had to endure attacks. In addition to these monasteries and other smaller towns, Tölz was also unable to escape the attacks of the Duke's mercenary troops, around 500 strong. During the Middle Ages, Tölz continued to be the focus of feuds several times. So in 1301 between Konrad von Egling zu Hohenburg and Philipp von Waldeck , who owned both estates in the Isarwinkel. Before 1262, Konrad I of Tölz and Hohenburg took over the area. In 1281 the Gries, the castle and the mills on the Ried were referred to as "market" in the land register of the Duchy of Baiern , although Tölz was only granted market rights in 1331 by Emperor Ludwig the Bavarians . Around 1200 the first Isar bridge was built over the then still raging river. It was about 100 meters upstream from today's bridge and connected today's Römergasse with the other bank. Due to the flood damage, this wooden bridge had to be replaced every six to eight years. After the death of the last heirs of the von Tollenz family, Tölz and Burg fell to the Wittelsbach family . The precarious financial situation of the ruling house led Duke Rudolph to lease Tölz and the surrounding area to Freising on August 5, 1300 . After ten years, Rudolph or an heir should redeem the pledge, otherwise it would fall “forever” to Freising, but the Bishop of Freising was still the owner of Tölz after 15 years. In 1328 the Tölz keeper Konrad der Maxlrainer announced that they had “compared because of the Tölz fortress” and the place fell back to the Wittelsbach family.

The forests in the area formed the basis for the rafting trade . The rafters' guild had 24 masters and numerous journeymen in Tölz. As early as 1320, the Tölz rafters' guild was powerful enough to forbid the surrounding farmers from rafting their own wood. In 1374 the first seal of the Tölzer market, the "Sigillum Civium In Tollentze", was awarded, today's city coat of arms . Due to its location on several trade routes, the salt route between Allgäu and Reichenhall, as well as the waterway on the Isar towards Munich and Danube , Tölz achieved prosperity. “The great fire” destroyed Marktstrasse, parish church, castle and parts of Gries in 1453. After this conflagration, Marktstrasse in Stein was rebuilt according to plan with great help from Duke Albrecht III. , who paid for this reconstruction out of his own money and was best known for his love for Agnes Bernauer . From 1460 a new castle was built . After the fire, Kaspar I headed the winemaker , and later his son Kaspar II. Winemaker and grandson Kaspar III. Vintners as carers and castle keepers control the fortunes of Tölz. 40 years before the adoption of the Bavarian purity law began in 1476 in Tolz Biersiederrei . By the end of the 15th century, the place had reached its decisive size, which it maintained until the end of the 19th century.

In 1492 the dukes Wolfgang and Christoph gave up the slogan “to Tölz” and had the town and castle plundered by their mercenaries. The reason for this was that they saw themselves as insufficiently compensated by Albrecht IV for their renunciation of the throne. Both sent letters to markets and cities asking them to pay homage. Only the keepers from Tölz, then Kaspar II. Winzerer, Kelheim and Schwandorf refused and sent the document to their duke. Albrecht IV. Accepted the Tölzer pledge of loyalty benevolently in 1491 and requested Tölzer for his armed forces against the Löwlerbund , which, however, weakened the defense of the place.

Early modern age

During the Thirty Years' War Maximilian I demanded 3000 guilders from Tölz for his war chest . If selected Tölzer and Benediktbeurer were drafted as early as 1618 to implement the "new mode" under Captain Hannibal von Herliberg, the "Fenndl (Fähnlein) zu Töltz" was withdrawn in May 1622 to join Tilly's army at Rain . The Tölzer were involved in the conquest of Heidelberg . On May 20, 1632, the first Swedish troops reached Tölz. Since Wolfratshausen had been devastated by these the day before , the Tölzer did not dare to resist. In negotiations with the nurses Caesar Crivelli the Swedes demanded 600 guilders to Tolz before pillage to spare. Since the market could not raise this amount itself, the sum was paid by the citizens and the Swedes then issued an accord note, which was supposed to protect Tölz from future plundering , but which quickly turned out to be worthless. The very next day, more Swedish troops appeared with guns, again demanding 2,000 guilders. After pleading and pleading, they reduced their demand to 500 guilders, but these could not be raised either, so that the castle and market were looted and devastated. The Swedes also shot at the market from today's Kalvarienberg and set it on fire in three places. At the Hohenburg in Lenggries they were busy preparing against the Swedes when Tölzer arrived and asked for help in fighting the fire and the Swedes. 200 men then moved to Tölz and "beat the Swedes to death". Upon request, the Hohenburgers stayed in Tölz, Crivelli gathered his troops and on May 26th the withdrawing Swedes were defeated at Kirchbichl and Dietramszell . The plague years 1633 (27 adults) and 1634 (from April to June 100 adults) depopulated the place further. The flowering time of their art Schreiner known artisans and rafters site (Tölzer boxes) has been completed thereby.

In 1631 there were already 22 breweries in Tölz , with sales as far as Werdenfelser Land and Tyrol . The main buyer was the city of Munich (8,730 buckets of beer in 1782, 5600 hectoliters). After the Battle of Kahlenberg , on February 11, 1686 , Max Emanuel asked Tölz for 1,000 guilders for his army in order to push the Turks out of Hungary. In addition, he requested 90 Tölzers for his armed force. On rafts loaded with supplies, the people of Tölz went on the Isar and Danube to the camp of the Bavarian relief army in front of Ofen in April 1686, and the city was liberated from the Turks on September 2nd . In 1751 the descendants of the Tölz family who remained in Hungary were traceable.

During the Spanish War of Succession , in which the Austrians occupied Bavaria, Tölz was at the center of the uprising of the Oberland farmers. The war commissioner Matthias Agidius Fuchs was able to win over the Tölz maintenance commissioner Joseph Ferdinand Dänkel for his plans. This ordered the mayors, including Hans Christoph Kyrein , to raise troops. The headquarters of the rebels was in the Höckhenhaus, the birthplace of the wine owner Johann Jäger . These three incited the locals to revolt, using threats as well. The 8,000 rifles promised from Hohenburg in Lenggries also turned out to be lies. On December 17, 1705, the "Kurbayerische Landesdefension des Oberlandes" was founded and the Tölzer Patent then called on all state patriots to resist. This survey came to a tragic end on the Sendlinger Murder Christmas . According to Johann Nepomuk Sepp, 2,769 people from the Oberland moved via Schäftlarn to Sendling, around 500 of which came from Tölz and the surrounding area.

On March 19, 1742, under Franz von der Trenck, troops of the Pandur and clumsy troops invaded Tölz as a result of the War of the Austrian Succession . Friedrich Nockher, the founder of the Kalvarienberg, who paid several hundred guilders out of his own pocket to the Pandours, prevented the plundering of the place. When a division of Pandurians withdrew on April 12th, they were attacked by Isarwinkler farmers and Trenck's adjutant Christian Gondola near Kirchbichl was killed by the Gaißach brook farmer Joseph Heimkreiter. Another five Pandours were killed in this attack, while Trenck's companion was spared. Gondola's saber and his leather, silver-embroidered gloves are now in the Tölzer City Museum. However, this attack had consequences. On May 22nd, Trenck reached Gaißach with clumsily and demanded the extradition of the brook farmer. Since this was refused, Trenck had one property after another, finally 22, set on fire and killed ten Gaißachers one after the other. The "Chapel of the Burned Down Cross" reminds of this today. After threats of further reprisals, Heimkreiter, who was hiding at the Rechelkopf , was finally extradited and beaten to death in Munich on June 7th. Friedrich Nockher was again able to avert plundering of Tölz, who on May 26th again paid 4,000 guilders in blood money . As a provocation, a student from Lenggries sent a few pfennigs to Trenck, who then had three farms in Lenggries burned down. Local farmers then drove out the Pandours, but Trenck was unsuccessful. In 1743 Austrian troops quartered themselves in Tölz.

From 1750, rafting and woodworking experienced a renewed heyday. Wood, lime and furniture were transported from the Isarwinkel on the Isar and Danube to Munich, Vienna and Budapest . As a result of a severe storm, large parts of the Princely Palace collapsed in 1770 . The castle was an extension of the last castle. It was then removed, the stones transported on the Isar to Munich and built there in the residence . The castle garden and pond were on the site of today's parking lot at the castle square and the community garden, the castle for the most part on the remaining, non-leveled spur on which there is now a kindergarten.

Modern times

In 1796, French troops marched through the market under Jean-Victor Moreau . In order to secure the place at Moreau's retreat, Albert von Pappenheim took over the defense of the market, but initially no more French came to Tölz. That only happened on July 16, 1800, one day after the Parsdorf armistice, when 20 hussars reached Tölz. In 1808 Tölz received the municipal constitution . In 1809 the Tölzer riflemen were involved in the fight against the Tyroleans , the Tölzer Landwehr defended Lenggries on July 17th against a Tyrolean invasion.

In 1861 the castle-like municipal hospital was built on Griesfeld, replacing the hospital on Krottenbach from 1822. It was expanded in 1889 and remained the municipal hospital until it was replaced in 1990 by a large, modern building in the bathing section (today's Asklepios City Clinic ).

In 1846 the turner's son Kaspar Riesch discovered Germany's strongest iodine sources on the Sauersberg . As a hunter, he observed how game animals were shot at certain sources. He carried a bottle of this spring water to Betz, a doctor in Tölz. Soon afterwards Otto Sendtner from Munich confirmed this discovery. Karl Raphael Herder and Gustav Höfler founded the Tölz hospital west of the Isar in 1856 as an iodine sulfur spring and mineral iodine bath. An upswing in this part of the village began with the emergence of spa and bathing businesses . Additional sources were discovered between 1856 and 1900.

From 1867, the "Railway Comité in Tölz" demanded its own "wood and coal railway line". Measurement of the route began in 1869 and the first phase of construction was completed three years later. In 1874 the Holzkirchen – Tölz railway was opened as a vicinal railway. The first station building , made entirely of red brick, was built in the same year. After the line to Lenggries was continued in 1924, a new, larger train station was built in the south-east of the city. The architect was Georg Buchner from Munich . The old railway systems were then given up. The technical and vocational high school is located in its place today and Eisenburger Straße continues on.

On June 22, 1899, the place was given the title " Bad ", the place name "Sickness" disappeared. The Munich architecture professor Gabriel von Seidl revitalized the dilapidated cityscape of Tölz from 1903 with new buildings in the homeland security style . He created new buildings, facade paintings and major redesigns that shape the image of the city to this day. Market and later town builder Peter Freisl (1874–1945), who carried out urgently needed structural measures between 1901 and 1937 that transformed Tölz from a rural market town into a modern seaside resort, played a significant role in the positive development of Tölz . As early as the end of the 19th century, he denounced decay and ailing conditions, even in public buildings. Although branches of the economy such as rafting, brewing, lime and coal distillery or trading in the famous Kistler goods were still profitable, he complained about the "lack of perspective for future development". Because the circumstances at the turn of the century changed dramatically. Due to the expansion of the railway network, the rafting industry lost its importance, the Tölzer breweries became fewer. The Kingdom of Bavaria began to develop from an agricultural to an industrial state. Places on main lines of the railway like Rosenheim gained in importance and outperformed smaller markets like Tölz. Magistrate resolutions, such as the dissolution of the Latin school, also disrupted the development of Tölz. Since many traditional pillars broke away at the end of the 19th century, the swimming pool should be used more with its potential. In retrospect, Freisl sees its beginnings in his “Tölzer Building History” very critically. However, he was able to rely on the "local beautification, health and tourism association" founded in 1888. The new buildings and redesigns initiated by Freisl, purchases of land, the improvement of hygiene, for example through the construction of the forest cemetery and the displacement of slaughterhouses from the interior, the new construction and expansion of schools, and the improvement of the infrastructure (new streets, Isar bridge, train station).

As early as 1888, Tölz was connected to the power grid and three power plants illuminated streets, as well as private and public buildings. From June 1, 1905, Germany's first full-service postal service began its permanent operation between Bad Tölz and Lenggries. Another positive development made it possible for Prince Regent Luitpold to grant the Bad Tölz market town charter on October 14, 1906 . In the same year Franz Edler von Koch became director of the "Krankenheiler Jodquellen AG"

After the First World War , in which Tölz had 150 fallen and missing people with around 6,000 inhabitants, a renewed upswing in tourism and spa business began. While Tölz visited 4,418 spa guests and 7,118 day trippers in 1919, with 162,077 overnight stays, by 1928 it increased to 12,714 spa guests and 10,341 day trippers and 315,796 overnight stays. Due to the high number of North German guests, the Johanneskirche was built as early as 1879/80 , the first Protestant church in the Oberland, for the construction of which Kaiser Wilhelm donated 1,000 Reichsmarks .

After the Walchensee power plant was built in 1924, the Isar barely had enough water for rafting. The construction of the Sylvenstein reservoir between 1954 and 1959 further tamed the river, and in 1961 the Bad Tölz power plant was completed, which has since dammed the Isar for more than a kilometer. In 1928 the EC Bad Tölz was founded, which later developed into one of the traditional and most successful Bavarian ice hockey clubs and thus laid the foundation stone to give Tölz the reputation of an "ice hockey city". The natural ice stadium was built in 1934 and was converted into an artificial ice stadium in 1952.

In the Third Reich , the first of the SS Junker Schools and a Nazi civil servants school in Bad Tölz began operating in 1934 . The construction of the Junker School was originally planned on a hill in the direction of Wackersberg, but that would have meant the end of the spa business. Two visits to Tölz are documented by Adolf Hitler , the last one in 1932. In mid-1940, a satellite camp of the Dachau concentration camp was established in Bad Tölz . In 1940/41 the 97th hunter division “Spielhahnjäger” was set up in Bad Tölz and the surrounding area . This was used in the Russian campaign , in Poland , Ukraine and in the Caucasus and was disbanded in Czechoslovakia at the end of the war in 1945 .

On March 27, 1945, the 38th SS Grenadier Division “Nibelungen” was set up in Bad Tölz , mainly made up of members of the Junker School and the Hitler Youth . Up until the last days of the war, the SS division “Götz von Berlichingen” fought with the advancing US armed forces in Bad Tölz and the surrounding area . The Wehrmacht had already withdrawn on April 26th. The Isar bridge and parts of the lower market street were badly damaged by American artillery fire during a German blast attempt. The resistance of the Waffen-SS, mostly very young, forcibly recruited soldiers, is said to have prompted the Americans to threaten to " bomb Tölz like Aschaffenburg ". Due to the onset of snowfall, however, approaching bombers have withdrawn again. Field Marshal General Gerd von Rundstedt , who is currently taking a cure in Tölz, is said to have contributed to protecting the place. On the night of May 1 to May 2, 1945, the US American 36th Infantry Division ("Texas Division") under Brigadier General Robert Stack occupied the city. The Waffen SS then withdrew towards Gaißach, Wackersberg and Lenggries.

Of the 1,300 called up, Tölz had 361 killed and 92 missing in World War II.

The lack of bombardment, which some locals still refer to today as the “miracle of Tölz”, meant that the huge imperial eagle, which had a swastika in its claws and had stood on the Isar bridge since 1934, melted down after the war and turned it into a statue of Mary as thanks which now adorns the fountain in the lower market street. The previously wooden well had been damaged by drunk SS Junkers.

After the end of the war, the SS Junker School was taken over by the US armed forces . The US General George S. Patton took over the post of military governor of Bavaria after the war and temporarily ruled from Bad Tölz. In memory of a fallen friend, he renamed the Junk School "Flint Barracks". Until the withdrawal in 1991, the Flint barracks was, in addition to an engineering school, also a European base of the Special Forces, commonly known as Green Berets . The words “Cleanest American Camp In Europe” appeared above the main entrance. The barracks no longer exist in their original architecture, as the buildings have only been partially preserved. The sports facilities, including a football stadium and a building that was used as a gym, boxing and ball games and also equipped with a sauna and a heated pool, the cinema and the archway above the main entrance no longer exist. Nevertheless, the exterior and the ground plan of the former barracks are still largely recognizable. However, the buildings inside have been completely rebuilt, as the city began a major redesign in 1998. There you can find various offices, shops and restaurants, the police inspection and in the courtyard of the former barracks the architecturally attractive “snail” (the construction costs of which were criticized by the taxpayers' association ) under the name “Flint Center” .

In 1956 the Tölzer Boys Choir was founded in the city. In 1969 Bad Tölz was recognized as a climatic health resort and in 2006 as a mud spa . With the Alpamare , Europe's first privately financed and operated adventure pool opened in Tölz in 1970. With its numerous attractions, the Alpamare became known nationwide and received several awards, but on August 30, 2015, operations were discontinued after 45 years of operation due to a lack of profitability, after the connected, traditional hotel "Jodquellenhof" had to close a few months earlier in its 125th year of operation . The television series Der Bulle von Tölz , which was broadcast from 1996 to 2009, made the city very popular, especially outside of Bavaria. In 2005 the new ice rink, the modern Hacker-Pschorr-Arena (with two ice rinks) was opened. This replaced the old Peter-Freisl-Stadion , the so-called corrugated iron palace , and also serves as a venue for events such as concerts and trade fairs.

Incorporations

On May 1, 1978 parts of the dissolved communities of Kirchbichl and a small part of Oberfischbach were incorporated as part of the regional reform .

Population development

Between 1988 and 2018 the city grew from 13,973 to 18,802 by 4,829 inhabitants or 34.6%.

|

|

The jump at the end of 1945 was due to the large number of displaced people .

politics

City council

The city council consists of 24 city councils:

| Political party | 2020 election | Election 2014 | 2008 election | Election 2002 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Councilors | be right | Councilors | be right | Councilors | be right | Councilors | be right | |

| CSU | 9 | 37.6% | 9 | 39.1% | 10 | 39.1% | 10 | 41.4% |

| GREEN | 7th | 27.7% | 4th | 17.2% | 4th | 15.5% | 2 | 9.3% |

| SPD | 2 | 9.4% | 3 | 12.8% | 3 | 14.8% | 4th | 17.4% |

| FWG | 6th | 25.3% | 8th | 30.9% | 7th | 30.6% | 8th | 31.9% |

| voter turnout | 52.7% | 43.5% | 45.4% | 48.9% | ||||

mayor

The first mayor is Ingo Mehner (CSU). He was elected on March 15, 2020 from three competitors with 50.84% of the valid votes. His predecessor was Josef Janker (CSU) from May 2008 to April 2020.

coat of arms

At the Great Fire letter of 1374 the seal of the market Toelz was shown for the first time, the "Sigillum Civium In Tollentze". From this the coat of arms, handed down from 1565, developed. The official description of the coat of arms reads: "In black a half, red armored golden lion". Half of the lion referred to the Duchy of Bavaria and was originally shown on a blue background.

Town twinning

Bad Tölz maintains the following city partnerships:

-

France : Vichy in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region (since 1963)

France : Vichy in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region (since 1963) -

Italy : San Giuliano Terme in Tuscany (since 2001)

Italy : San Giuliano Terme in Tuscany (since 2001) -

Austria : Market town of Mayrhofen in the Zillertal .

Austria : Market town of Mayrhofen in the Zillertal .

Religious communities

In the municipality of Bad Tölz, around 10,700 residents belong to the Roman Catholic Church . The parish association of Bad Tölz consists of the parishes Maria Himmelfahrt Bad Tölz, Hl. Familie Bad Tölz and St. Martin Ellbach. In addition, the parish of St. Nikolaus in the Wackersberg parish is part of the parish association. The parish association is located in the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising (South region).

The Evangelical Lutheran parish of Bad Tölz is the second largest religious community in Bad Tölz. Along with eleven other parishes, it belongs to the Evangelical Lutheran Dean's Office in Bad Tölz (approx. 35,000 members).

Other Christian denominations are represented by the Old Catholic parish of Bad Tölz (Munich parish), the Free Christian Community of Bad Tölz and the New Apostolic Church . The Islamic community, the Jehovah's Witnesses and a Buddhist group represent other religious communities.

traffic

Road traffic

The federal highway 13 leads through Bad Tölz from Würzburg to the Sylvensteinspeicher and the federal highway 472 , part of the German Alpine Road , from Marktoberdorf to Irschenberg .

A 2.5 km north bypass for the congested federal highways 472 and 13 is included in the federal route plan as an urgent requirement. The construction costs are projected at EUR 8.5 million.

Rail transport

Bad Tölz is on the single- track Holzkirchen – Lenggries railway line . Bad Tölz train station is served every hour by trains of the Bayerische Oberlandbahn (BOB) from Munich main station to Lenggries . In the rush hour, additional repeater trains run every half hour.

Bus transport

Several regional and city bus routes operated by the Upper Bavaria Bus and the Munich Transport and Tariff Association (MVV) travel to Bad Tölz. The most important stops are the train station and the central bus station (ZOB). The bus station is more central than the rail station.

Public facilities

Educational institutions

As the educational center of the southern district of Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen, the city has a high density of schools. In addition to three primary schools, this includes a secondary school, a secondary school and the Gabriel-von-Seidl-Gymnasium. There is also a school for people with learning disabilities and a school for the mentally handicapped. Also located in Tölz are the vocational training center for bricklayers and carpenters , the state vocational school and a technical college and a vocational college .

In addition, the University of Applied Management offers various courses on its Bad Tölz campus.

Offices

Since the Bavarian district reform in 1972, the district offices have been concentrated in the cities of Bad Tölz and Wolfratshausen. The main offices of the District Office and the Forestry Office are located in Bad Tölz. The tax office and the surveying office have branches in the city.

freetime and sports

The city of Bad Tölz is known for its high recreational value. After the closure of the Alpamare adventure pool , the city still has an indoor and natural outdoor pool . There are several golf courses and climbing opportunities in the vicinity. The DAV climbing center Upper Bavaria South is located in Bad Tölz. Tölz and the Oberland were described as a suitable destination for cyclists as early as 1892. Today the city is at the junction of several cycle paths z. B. the Via Bavarica Tyrolensis , the Isar cycle path and the Lake Constance-Königssee cycle path. A sporty flagship of the city is ice hockey and the Tölzer Löwen, which is based here . The weeArena (formerly Hacker-Pschorr-Arena) used for home games can accommodate 4115 people.

Culture and sights

The Marktstraße forms a late medieval and baroque ensemble with broad-based houses of the Tölz merchant families and patricians adorned with facade paintings ( Lüftlmalerei ) . The old post office from 1600, the Sporerhaus, the Moralthaus and the Old Town Hall with the onion dome from the 15th century, the former girls' school (1843 to 1982) from 1588, the Marienstift, the Höckhenhaus and the nursing home from Kaspar Winzerer II from 1485. In the cellar of today's Metzgerbräus below the parish church, late Gothic vault remains of the first Tölz castle have been preserved. The Tölzer castle stood until it collapsed in 1770 due to a storm to a large extent, served at the site of today's Castle Square and the new town hall, which was built in 1772 and 1779 as the seat of the judge.

The Khanturm from 1353, one of the most important medieval buildings in the city, which formed the historic end of Marktstrasse, was sacrificed to the growing car traffic despite protests by the city council in 1969. Subsequently, a free new building was built that was only approximated and widened to the historical original. Instead of the Gothic gateway, the new tower, designed by the architect Hans Döllgast , has a wide, flat arch made of concrete.

At its upper eastern end is the monument to Kaspar Winzerer III , called the "Golden Knight" , erected in 1887 . He was a governor in Toelz. The memorial initiated by Johann Nepomuk Sepp also serves to commemorate the six Tölz soldiers who died in the Franco-German War . The town museum is also located at the beginning of Marktstrasse in the magnificent home and town house from 1602. This home and town house also serves as the backdrop for the police headquarters of the television series " Der Bulle von Tölz ".

Further down towards the Isar is the late medieval parish church of the Assumption of Mary , the oldest existing structure in the Isarwinkel (built from 1460), which received the neo-Gothic tower from 1875 to 1877 and some of the furnishings date from the 19th century. Overlooking the city in the north is the Calvary with the Holy Cross Church, a double church complex from the 18th century (built from 1723), the Holy Stairs (replica of the Scala Santa in Rome) and the Leonhardi Chapel. The chapel was built in 1718 in honor of Saint Leonhard and the fallen soldiers of the peasant uprising of 1705. It is also the destination of the Tölzer Leonhardifahrt , which has been taking place on November 6th every year since 1856 , with more than 80 wagons and around 25,000 visitors annually, the largest of its kind. One of the two places of execution in Tölz was located on this Calvary in the Middle Ages and the early modern period, which the name Galgenleite is reminiscent of.

From the Kalvarienberg there is a panoramic view over the Isarwinkel and into the Karwendel Mountains . To the east of Marktstrasse is the Maria Hilf subsidiary church (Mühlfeldkirche, built from 1735) with a fresco of the Tölz plague procession by Matthäus Günther in the chancel and a double onion tower . In the bathing part of the city, west of the Isar, are the Kurpark, the Streidlpark and the Rosengarten. The Franciscan Church is also located there . Its construction was initiated by Maximilian I in 1624, who sent the Franciscans from Milan to Tölz to build a monastery there. Also on the left bank of the Isar is the Protestant Johanneskirche (built 1879/80), with a ceiling painting by Hubert Distler from 1970 and an altarpiece by Lovis Corinth from 1898.

On a hill above the city, in the direction of Wackersberg , stands the memorial of the Spielhahnjägerdivision. This monument was erected there in 1957 and serves to commemorate more than 10,000 game cock hunters who fell in World War II. Before that, there was a pavilion (called Belvedére) at this point, which was built in 1848 by students and the Freikorps Tölz in honor of the imperial administrator Johann von Österreich .

The Isar Bridge serves as a link between Tölz's old town and the bathing area. This has been renewed and redesigned many times over the centuries. The last wooden bridge was replaced by an iron one in 1881. This was followed in 1934 by a reinforced concrete bridge, the axis of which was oriented towards Marktstrasse for the first time. Today's Isar Bridge was built in 1969.

Worth the rafters monument and 1929-1930 of the bath are also part of Heinz Moll newly built pump room , the largest in Europe (110 m long). Since the end of the cure, the Wandelhalle has developed into a point of attraction for artists and curators who realize exhibitions and interdisciplinary cultural projects here.

The Kurhaus was built according to the design by Gabriel von Seidl , who died in 1913, so that his brother Emanuel von Seidl took over the work until completion.

The last remaining historic lime kiln is located near the banks of the Isar at the Jägerwirt , as is the forest cemetery, which was inaugurated in 1906 (after the old cemeteries around the Tölzer churches were gradually closed for reasons of hygiene and space). Somewhat in the shadow of Marktstrasse lies Gries with its narrow, winding medieval streets and squares and numerous fountains. This district, the oldest of Tölz, once served as a place of residence and hostel for the craftsmen (mainly raftsmen, lime burners, sieve makers, fishermen, charcoal makers and carpenters). Because many of the poor craftsmen could not afford their own house at the time, they often only owned or rented one floor. The wooden stairs on the outer wall of many houses in Gries are evidence of this.

Since Tölz has been hit by devastating large fires several times in the course of its history, the Floriansbrunnen was built on Fritzplatz in honor of St. Florian . In order to mock the customs and tax office behind it at the time, its colorful wooden sculpture was depicted with its bare bottom.

Tölz was once known for its beer and the main supplier for Munich, although the Oktoberfest , which had its own beer taverns , was also supplied. Up until the 18th century there were 22 breweries in Tölz. 19 of them were on Marktstrasse, two on Klammergasse and one on Amortplatz. Numerous building and alley names are reminiscent of the brewery's history. Another small brewery was located in the Franciscan monastery. The Tölz hop gardens, which were not very productive, were given up around 1650, and hops from then on were mainly sourced from Franconia and Bohemia . Most of the barley was bought in the Munich Schranne .

The advantage of the market was the cool storage cellars, insulated and near the river. Tölz was built on tuff , whereas Munich was built on gravel. So around 1700 several beer storage cellars were built on the Mühlfeld, some of which still exist today. With the invention of the compression refrigeration machine by Carl von Linde in 1873, this advantage was lost and breweries newly established elsewhere reduced sales noticeably. The decline of the Tölzer brewing industry is said to have started as early as 1816.

The last historic brewery, the Grünerbrauerei (founded in 1603) closed its doors in 2005 and was converted into a residential building. There are now two breweries again in Tölz. In 2008, a former brewer from Reutberg Monastery founded a new brewery under the name Mühlfeldbräu not far from the former Grünerbrauerei. This was followed by the Binderbräu in the bathing section at the end of 2015 .

Other facilities

There are several libraries in the city, e.g. B. the city library and the city archive, the spa library in the bathing area and the parish library. Exhibitions and readings take place in the Alte Madlschule cultural center and in the art tower and art park at the Flint Center.

The Tölzer Marionette Theater on Schlossplatz has existed since 1908, making it one of the most traditional puppet theaters in Germany. It was founded by the pharmacist Georg Pacher, whose grandfather ran a traveling theater as early as 1850. In 2013, the only Zeiss planetarium in southern Bavaria was added to the marionette theater.

Since 2009 the simulation center for mountain and air rescue of Bergwacht Bayern has been located in Bad Tölz . The world's first such simulation system offers the advantage that training on real helicopters can be largely dispensed with.

Regular events

In Bad Tölz there are regular events with a national character, e.g. B. the famous Tölzer Leonhardifahrt , the Christkindlmarkt and the Tölzer Rose Days.

Soil monuments

Personalities

literature

- Stephan Bammer: A Brief History of Bad Tölz . Ed .: City of Bad Tölz. Bad Tölz 2017, ISBN 978-3-00-056827-5

- Peter Blath: Bad Toelz. Everyday impressions . In: The archive pictures series . Karl M. Sutton-Verlag, Erfurt 2009, ISBN 3-89702-885-9

- Maximilian Czysz, Christoph Schnitzer: Murder stories from Bad Tölz and the Isarwinkel . CS publishing house

- Gregor Dorfmeister, City of Bad Tölz: Bad Tölz , Löbl-Schreyer Verlag, 1988

- Peter Eberts, Bavarian Publishing House Bamberg, Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen district (Ed.): Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen district. Bavaria from its most beautiful side . Bayerische Verlagsanstalt, Bamberg 2014, DNB 1072471353

- Walter Frei: Tölz in old pictures . 2., ext. Edition. Mayr, Miesbach 2000

- Christoph Schnitzer (Eds.), Martin Hake, Sebastian Lindmeyr, Gisbert Pohl: Bad Tölz: Rare Photos, Forgotten Stories (s) up to 1920 . CS-Verlag, 2019

- Walter Frei, Barbara Schwarz (Ed.): Bad Tölz. Streets, squares, people . Walter Frei, Bad Tölz 2003, DNB 987424785

- Roland Haderlein, Claudia Petzl, Christoph Schnitzer: Bad Tölz. City and country in portrait . CS-Verlag, 2006

- Roland Haderlein, Christoph Schnitzer: The Tölzer city parish church of the Assumption . CS-Verlag, 2011

- Claus Janßen, Historical Association for the Bavarian Oberland: Back to the Future - Gabriel von Seidl in Tölz , Stephan Bammer Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-00-041570-8

- Georg Paula , Angelika Wegener-Hüssen: Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen district (= monuments in Bavaria . Volume I.5). Karl M. Lipp-Verlag, 1994, ISBN 978-3-87490-573-2

- Christoph Schnitzer: The Nazi era in the Altlandkreis Bad Tölz and its consequences . 1st edition 1995, 2nd edition 2001, 3rd edition 2015. Verlag Tölzer Kurier

- Christoph Schnitzer: The Tölzer Leonhardifahrt . CS publishing house

- Barbara Schwarz: Der Isarwinkel and Bad Tölz , Volk-Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-937200-90-3

- Patrick Staar, Kurt Stern: Tölzer Buam. Ice hockey stories, people, emotions

- Gabriele Stangl: Leonhardifahrt in Bad Tölz. Verlag Günther Aehlig, 1977, ISBN 978-3-922189-02-2

- Georg Westermayer : Chronicle of the castle and the market Tölz . 1st edition 1871, 2nd edition 1895: Verlag Franz Paul Schapperer, Tölz. 3rd edition 1976: Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz, DNB 780193474 ( digital copy of the 1st edition )

- Edmund Kammel : Cyclist tour book for Weilheim, taking into account the neighboring towns of Landsberg, Munich, Murnau, Schongau and Tölz . Gebr. Bögler, Weilheim 1892 ( digitized version )

- Sibylle von Kamptz: First World War in the Tölzer Land . CS-Verlag, 2018

Web links

- Homepage

- Entry on the coat of arms of Bad Tölz in the database of the House of Bavarian History

References and comments

- ↑ "Data 2" sheet, Statistical Report A1200C 202041 Population of the municipalities, districts and administrative districts 1st quarter 2020 (population based on the 2011 census) ( help ).

- ↑ 1. Mayor Dr. Ingo Mehner. City administration Bad Tölz, accessed on May 25, 2020 .

- ^ Community Bad Tölz in the local database of the Bavarian State Library Online . Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, accessed on September 6, 2019.

- ↑ a b c Walter Frei: Tölz in old pictures . 2., ext. Edition. Mayr, Miesbach 2000, p. 7 .

- ↑ a b Peter Blath: Bad Tölz. Everyday impressions . In: The archive pictures series . Karl M. Sutton-Verlag, Erfurt 2009, ISBN 3-89702-885-9 , p. 7 .

- ^ Roland Haderlein, Claudia Petzl, Christoph Schnitzer: Bad Tölz. City and country in portrait . CS-Verlag, 2006, p. 7 .

- ↑ Stephan Bammer: A short history of Bad Tölz . City of Bad Tölz (ed.), 2017, p. 14 .

- ^ Roland Haderlein, Claudia Petzl, Christoph Schnitzer: Bad Tölz. City and country in portrait . CS-Verlag, 2006, p. 82 .

- ^ Georg Westermayer : Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 11 .

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 254 .

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 13 .

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 18 .

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 44 .

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 46 .

- ↑ Stephan Bammer: A short history of Bad Tölz . City of Bad Tölz (ed.), 2017, p. 22 .

- ↑ Stephan Bammer: A short history of Bad Tölz . City of Bad Tölz (ed.), 2017, p. 19 .

- ↑ Isarkiesel; Number 2; Isarkiesel-Verlag; 1998; Page 11; The Tölz castles

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 89 .

- ^ Peter Blath: Bad Tölz. Everyday impressions . In: The archive pictures series . Karl M. Sutton-Verlag, Erfurt 2009, ISBN 3-89702-885-9 , p. 8 .

- ↑ a b c Georg Paula, Angelika Wegener-Hüssen: Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen district (= monuments in Bavaria . Volume I.5 ). 1st edition. Karl M. Lipp-Verlag, 1994, ISBN 978-3-87490-573-2 , p. 16 .

- ^ Walter Frei: Tölz in old pictures . 2., ext. Edition. Mayr, Miesbach 2000, p. 127 .

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 66 .

- ↑ Isarkiesel; Number 2; Isarkiesel-Verlag; 1998; Page 11; The Tölz castles

- ↑ Isarkiesel; Number 13; Isarkiesel-Verlag; 2002; Page 23; “I did business on the water!” - A brief history of rafting on the Isar

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 111 .

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 95 .

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 160 .

- ↑ a b Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 161 .

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 162 .

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 165 .

- ↑ The Chronicle of Tölz; Publishing house Günther Aehlig; Georg Westermayer; 3rd edition 1976; Page 169

- ↑ The Chronicle of Tölz; Publishing house Günther Aehlig; Georg Westermayer; 3rd edition 1976; Page 170

- ↑ Isarkiesel; Number 6; Isarkiesel-Verlag; 1998; Page 5; The Sendlinger Murder Christmas 1705 - Myth and History

- ^ Georg Paula, Angelika Wegener-Hüssen: Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen district (= monuments in Bavaria . Volume I.5 ). 1st edition. Karl M. Lipp-Verlag, 1994, ISBN 978-3-87490-573-2 , p. 18 .

- ↑ Isarkiesel; Number 6; Isarkiesel-Verlag; 1998; Page 7; The Sendlinger Murder Christmas 1705 - Myth and History

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 184 .

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 185 .

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 240 .

- ^ Peter Blath: Bad Tölz. Everyday impressions . In: The archive pictures series . Karl M. Sutton-Verlag, Erfurt 2009, ISBN 3-89702-885-9 , p. 69

- ^ Walter Frei: Tölz in old pictures . 2., ext. Edition. Mayr, Miesbach 2000, p. 8 .

- ^ Anton Platiel: For the 32nd Bavarian Doctors' Day in Bad Tölz. (PDF file; 56.6 MB) In: Bayerisches Ärzteblatt 10/79. 1979, p. 868 , accessed January 9, 2016 .

- ^ Die Tölzer Eisenbahnlinie In: Isarkiesel , number 7. Isarkiesel-Verlag, 1999, p. 13

- ^ Wilhelm Volkert (ed.): Handbook of Bavarian offices, communities and courts 1799–1980 . CH Beck, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-406-09669-7 , p. 428 .

- ↑ a b Walter Frei: Tölz in old pictures . 2., ext. Edition. Mayr, Miesbach 2000, p. 9 .

- ^ Christoph Schnitzer, Roland Haderlein, Claudia Petzl: Bad Tölz . CS-Verlag, 2006, p. 97

- ^ A b Claus Janßen, Historical Association for the Bavarian Oberland: Back to the Future - Gabriel von Seidl in Tölz . Stephan Bammer Verlag, 2013, p. 3

- ↑ Claus Janßen, Historical Association for the Bavarian Oberland: Back to the Future - Gabriel von Seidl in Tölz . Verlag Stephan Bammer, 2013, p. 9ff

- ^ Peter Blath: Bad Tölz. Everyday impressions . In: The archive pictures series . Karl M. Sutton-Verlag, Erfurt 2009, ISBN 3-89702-885-9 , p. 13

- ^ Peter Blath: Bad Tölz. Everyday impressions . In: The archive pictures series . Karl M. Sutton-Verlag, Erfurt 2009, ISBN 3-89702-885-9 , p. 77

- ↑ Christoph Schnitzer: The Nazi era in the Altlandkreis Bad Tölz and its consequences . Verlag Tölzer Kurier, 2001, p. 8 .

- ↑ Christoph Schnitzer: The Nazi era in the Altlandkreis Bad Tölz and its consequences . Verlag Tölzer Kurier, 2015, p. 113 .

- ^ A b Rainer Bannier: The last days of the war in Gaißach: 200 interested parties at a lecture. In: Merkur.de. May 2, 2019, accessed May 2, 2020 .

- ↑ “A gruesome sight”: contemporary witness remembers the last days of the war in Bad Tölz. In: Merkur.de. May 1, 2020, accessed May 2, 2020 .

- ↑ Josef Wasensteiner: From childhood, war and captivity . Isarwinkel-Verlag, 2019, p. 59 .

- ↑ Christoph Schnitzer: The Nazi era in the Altlandkreis Bad Tölz and its consequences . Verlag Tölzer Kurier, 2015, p. 112 .

- ↑ Christoph Schnitzer: The Nazi era in the Altlandkreis Bad Tölz and its consequences . Verlag Tölzer Kurier, 2001, p. 82 .

- ↑ Christoph Schnitzer: The Nazi era in the Altlandkreis Bad Tölz and its consequences . Verlag Tölzer Kurier, 2001, p. 162

- ↑ Christoph Schnitzer: The Nazi era in the Altlandkreis Bad Tölz and its consequences . Verlag Tölzer Kurier, 2001, p. 157 .

- ↑ Christoph Schnitzer: The Nazi era in the Altlandkreis Bad Tölz and its consequences . Verlag Tölzer Kurier, 2015, p. 129 .

- ^ Federal Statistical Office (ed.): Historical municipality directory for the Federal Republic of Germany. Name, border and key number changes in municipalities, counties and administrative districts from May 27, 1970 to December 31, 1982 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Mainz 1983, ISBN 3-17-003263-1 , p. 569 .

- ↑ Local elections in Bavaria on March 15, 2020 - overall result. Retrieved March 16, 2020 .

- ↑ Local elections in Bavaria on March 16, 2014 - Upper Bavaria municipal council elections. In: www.wahlen.bayern.de. Retrieved January 9, 2016 .

- ↑ Election of the municipal councils in the municipalities belonging to the district in Bavaria in 2008 according to municipalities. In: wahlen.bayern.de. Retrieved January 9, 2016 .

- ↑ Election of the municipal councils in the municipalities belonging to the district in Bavaria in 2002 according to municipalities. In: www.wahlen.bayern.de. Retrieved January 9, 2016 .

- ↑ Stephan Bammer: A short history of Bad Tölz . City of Bad Tölz (ed.), 2017, p. 25 .

- ↑ Buddhist center of the Bad Tölz Diamond Way Line . In buddhismus-bayern.de , accessed on January 9, 2016

- ↑ Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Housing: Federal Transport Route Plan ( Memento from November 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). P. 91, accessed on January 9, 2016 (PDF; 101 kB)

- ^ Edmund Kammel : Cyclist tour book for Weilheim, taking into account the neighboring towns of Landsberg, Munich, Murnau, Schongau and Tölz . Gebr. Bögler, Weilheim 1892 ( digitized version )

- ↑ 40 years ago the khan tower was demolished . Merkur.de

- ↑ mediaTUM , University Library, Technical University of Munich, Collections, Hans Döllgast

- ↑ The Isarwinkel and Bad Tölz; Volk-Verlag; Barbara Schwarz; 2010; Page 54

- ^ Georg Westermayer: Chronicle of the castle and the market of Tölz . 3. Edition. Verlag Günther Aehlig, Bad Tölz 1976, DNB 780193474 , p. 245 .

- ↑ The city of 22 breweries. In: sueddeutsche.de. July 28, 2016, accessed December 11, 2016 .

- ↑ The city of 22 breweries. In: sueddeutsche.de. September 18, 2015, accessed December 11, 2016 .

- ↑ The secret of Tölzer beer. In: Merkur.de. September 25, 2016, accessed December 11, 2016 .

- ↑ New life for Tölz brewing tradition. In: https://www.merkur.de/ . March 1, 2009, accessed January 10, 2016 .

- ↑ Binderbräu: History (n) of beer. In: https://www.merkur.de/ . January 15, 2009, accessed January 19, 2016 .

- ↑ The Isarwinkel and Bad Tölz; Volk-Verlag; Barbara Schwarz; 2010; Page 54

- ↑ Simulation center for mountain and air rescue. (PDF; 3.06 MB) In: bergwacht-bayern.de. Bergwacht Bayern, accessed on January 10, 2016 .

- ↑ Helicopter rescue in the training hall. Worldwide unique simulation center for mountain and air rescue. (PDF; 256 kB) In: bw-zsa.org. Bergwacht Bayern, accessed on January 10, 2016 .