History of the Port of Hamburg

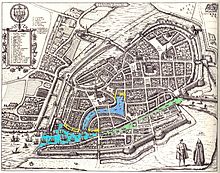

The history of the Port of Hamburg describes the development of the port from a place of landing on a tributary of Bille for Alster in Hamburg Old Town in the 9th century, with the harbor right from 1189, a Alster port in the 16th century; to a port on the Elbe with numerous harbor basins in the 19th century and further to a so-called world port upstream to the west .

In line with this development, the port image has undergone fundamental changes time and again: as the Alster port, it had grown continuously over the centuries and with the relocation to the Elbe, its expansion grew many times over over the decades. 1860 was the picture still characterized by tightly packed sailing ships and a few steamers on the city side of the North Elbe, the envelope was to ship its own cargo gear to admit acts Port operations take place on the quays werkten port workers with hand trucks and Schott's carts and hand cranes and winches. In 1910, steamships had displaced the freighters , and general cargo handling took place in ever deeper port basins on ever more extensive quays using steam and electric cranes. Since the 1970s, container ships and almost completely automated transshipment have dominated the picture, and the port activities shifted down the Elbe, where previously marshland and fishing villages were. The port areas close to the city center have become industrial wastelands for which the city is looking for new uses.

Development up to the end of the Hanseatic League in the 17th century

The port is a foundation of the city's prosperity. In its beginnings, this can be seen specifically in the supply of the settlement with raw materials and food for the daily needs of its residents. The Elbe was a transport route for the agricultural products of the areas on the Upper Elbe and the hinterland up to the Vltava . The location of the city on a river, not too far from its mouth into the sea, the accessibility of the hinterland via the Elbe and its tributaries as far as the Reich as a sales market and supplier of goods, favored the development of a transshipment point and thus the city. The sale of goods seaward and imports from other countries favored the formation of the merchants' class, who formed the Hanseatic League for their own protection abroad . In addition to the practical, everyday use of the Hanseatic Offices, the Hanseatic League offered diplomatic representation to foreign cities and princes. In order to assert the interests of its members, it also waged wars against states.

The dominance of the merchants in the politics of the Hamburg Council repeatedly brought about conflicts with the other citizen groups over the centuries, which were settled in several recesses , but also went up to the deployment of imperial troops.

First port facilities

The first Hamburg port in the 9th century was not yet on the Elbe, but on Reichenstraßenfleet , a former estuary of the Bille zur Alster, south of a Wik near the Hammaburg . The first merchant ships moored at a 120-meter-long and six-meter-wide wooden landing stage. Archaeologists found evidence at the Rolandsbrücke and the Dornbusch , near Domstrasse and the Old Fish Market . The Reichenstraßenfleet was filled in in 1877, its course north of the Kleine and Große Reichenstraße can still be traced by street names: the Kattrepelsbrücke , Rolandsbrücke and Börsenbrücke are no longer river overpasses and both Neß (nose or headland) and Hopfensack denote former dead ends that ended at the watercourse .

At the beginning of the 12th century, under Duke Ordulf from the Billunger family , a first artificial harbor basin was created near the confluence of the Reichenstraßenfleet in the Alster. The area near the New Castle was raised from clay and sand and a quay wall made of tree trunks was built in the Alster loop. This second port of Hamburg was completely destroyed in a storm surge on February 17, 1164, the first Julian flood .

The development of the now known trading port goes back to the Counts of Schauenburg and Holstein , who founded a secular new town on the west side of the Alster towards the end of the 12th century , in contrast to the church old town of the Hammaburg settlement east of the Alster, under the influence of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen . With an economic program , merchants, craftsmen and boatmen were recruited as settlers who created a port on the main arm of the Alster, in the immediate vicinity of the destroyed facility at the Neue Burg , which was supposed to provide navigable access to the North Sea. The reorientation of trade focus from Lubeck to Hamburg took place after the assignment of Lübeck settlement on Henry the Lion by Count Adolf II .

In 1266, the old town and new town were connected by the Trostbrücke , which crosses the former main arm of the Alster, which was named Nikolaifleet in 1916 .

In 1188 the settlement received city rights. The official founding of the port on May 7, 1189 annually as Hafengeburtstag celebrated is attributed to an alleged by Emperor Barbarossa issued on this date carte blanche , the hamburgers both the duty-free from the sea to the city, such as the fishing rights on the Elbe " two miles on either side of town "granted. This document is presumably a forgery from the 13th century, which is indicated by both the place of issue and the seal. In 1265 Hamburg got into a dispute with the downstream city of Stade . In 1259, Bremen's Archbishop Hildebold gave it the right to stack and demanded that merchants passing by should offer their goods within the city for a period of three water times , i.e. one and a half days based on the tide , before they went on to Hamburg . With evidence of allegedly older rights, Hamburg, which was then smaller, was able to secure the privilege of free trade and, among other things, achieved economic dominance on the lower Elbe. During this time, the city's first statute book was created; in 1270, the Ordeelbook (judgment book) recorded provisions of civil law, criminal law and a number of ship law provisions in Low German ; it also determined the behavior of the ship's crews in the port and the captains' liability for damages towards the owners.

The islands of Cremon and Grimm , formed by the branched river system of the Bille and Alster arms, were included in the city fortifications between 1240 and 1280. The center of the port initially continued to be the small port basin at the Trostbrücke. The count's customs house (1266), the scales (1269) and the crane (1291) were built here.

As early as the 14th century, the port had to be expanded to the mouth of the Alster , as the river carried less and less water due to the damming on Reesendamm from 1235 and the creation of the Alster Lake (today the Inner and Outer Alster) and did not hold sufficient depth for shipping. Today the Nikolaifleet falls dry at low tide. The transshipment point was now in the inland port between Kajen / Hohe Brücke and Kehrwieder , which still exists today, and from 1258 the diversion of the Bille provided enough water. It originated Dat Deep , a watercourse which still today Oberhafen and Zollkanal is understandable. In 1353, a second crane, the so-called Neue Krahn, was erected near the Hohe Brücke . Over the centuries, the wooden structure was replaced several times, until an iron crane was installed in its place in 1858 and converted to electrical operation in 1896. It was used until 1974 and is still preserved as a sight.

From 1351 the port entrance to the Elbe was secured with the so-called Niederbaum , a network of moored trunks that formed a tree wall at night or when there was a threat of war across the fairway . To the east to the Bille and Elbe above the city, the Winserbaum , called Oberbaum from 1385, secured the eastern port entrance, roughly at the height of today's Messberg .

A significant measure was the construction of a defensive tower on Neuwerk , which was decided in 1299 and finished in 1310 . This island, located in the mouth of the Elbe, came into Hamburg property in 1316 through an alliance agreement with the Wurtfriesen . The tower served both as a navigation mark and as a military base and thus secured the trade route. Hamburg levied a work tariff on all incoming and outgoing seagoing vessels , which was used to finance the construction of the tower and also to set up the navigation marks and to lay out the buoys on the Lower Elbe. Hamburg thus asserted its claim to dominance over the Elbe .

The oldest representation of the Port of Hamburg can be found as the introduction to the chapter Van Schiprechte in the illuminated manuscript of the Hamburg city law from 1497.

Trade goods and destinations

Hamburg as an up-and-coming trading center created an ideal connection between the agrarian East and the markets of Western Europe. The trade routes were expanded to London, Scandinavia, Iceland and the Atlantic coast as far as southern Europe, and the goods handled were diverse.

In the 13th and 14th centuries, cloths came mainly from Brabant and had a large share of imports in terms of value, later the share of Dutch and English cloths increased. Westphalian linen was exported. Grain and wood from the hinterland of the Elbe were important export items in terms of quantity. Furs and wax came from Eastern Europe. Salt came from Lüneburg (Hamburg had a share of 30%). In the 15th century, Baiensalz , sea salt from France (Bourgneuf) and Portugal, was also imported and resold in large quantities . Fish came as stockfish from Iceland, Scotland and Norway, as matjes from Skåne and later also from Holland. Wine was imported from France. Other goods are: Copper from Rammelsberg for export to England and Flanders and metals and metal products from Scandinavia for import. In the 16th century, the importance of the spice trade also increased.

An important export item from our own production was beer, which was shipped to Scandinavia and Holland. From the 13th century beer was exported from Einbeck , from 1290 the former town hall was used as a warehouse and bar and was soon called Eimbecksche Haus . The beer brewery in Hamburg has been in use since the early 14th century , in 1376 there were 457 breweries here, the annual production was around 170,000 hectoliters. In the following centuries, the export could be increased with the qualitative improvement in the change from red and dark beer to wheat beer . The recipe with the addition of hops when brewing beer was closely guarded as a secret and its passing on was threatened with punishment. The beer export formed the basis of the wealth of Hamburg, which was considered the "brewery of the Hanseatic League".

The city council, which was strongly influenced by the merchants, tried by means of a number of regulations to obtain privileges for the citizens in the affreightment and unloading of the ships and in this sense issued Burspraken , these are orders of the council that are held at citizens' meetings in December and February - that is, in the time when seafaring was idle - were announced. For example, guests were not allowed to trade directly with other guests. On the other hand, Hamburg accepted the Merchant Adventurers from London, contrary to the Hanseatic interests.

Around 1598 there were regular ship connections between Hamburg, Rouen , Berlin, Amsterdam (every 11 days) and Bremen as exchange trips with fixed tariffs and mutual preferential treatment of the skippers from the respective city.

Port operations

In Burspraken, it was regulated at an early stage where ships were berthed, unloaded or loaded. Unloading and loading had to take place at short notice in the area of the cranes and quay walls, later especially at the western extension of the port, the quays (so called since 1465). The use of fire was forbidden within the enclosed harbor as a fire protection measure, which probably also benefited the inns. Ballasters directed places for ballast dropping and waste disposal, and as early as 1359 a fine of three silver marks was threatened for violations. The cleaning of the canals was ordered in Burspraken and from 1609 could also be instructed directly by the Düpeherren , this was to ensure sufficient draft in the port for the ships.

The ship's crew was responsible for loading and unloading, until the 19th century there were no regulations here. After the unloading, there was a strong differentiation between professions, all of which had to be citizens of Hamburg who worked at fixed rates. Public offices were auctioned to the highest bidder in favor of the city treasury.

- Grain, coal and salt carriers and knives took care of the transport from the unloading point. Kneveler were responsible for the beer transport. The porters were also responsible for ensuring that customs clearance was correct.

- The crane and scales were leased for one year each. Crane girders who worked for the crane leaseholder formed an evangelical brotherhood (for benevolent help in need; 1594)

- Bestätter distributed the goods cleared on the crane centrally to ferrymen. which could also be foreigners and took over the transport to the hinterland with ships.

- Boers had their own ships or barges for the transport of goods to the roadstead, Ewerführer were responsible for the transport between the ships. The Ewerführerordnung had created a fixed, regular route between Hamburg and Harburg ; there was no Elbe bridge yet. They had the monopoly for transport to neighboring places, boats apparently operated longer distances.

- The bar manager was responsible for the buoying of the Elbe, in particular the laying out of the barrel after the winter on behalf of the combing department, and hired his own people for this.

- The Wasserschout was responsible for the registration, recruitment and prosecution of seafarers (from 1691) and was subordinate to the Admiralty .

The seafarers were organized, mostly according to sailing areas, in religious brotherhoods, mostly attached to monasteries, which were dissolved with the Reformation. Since 1522 there were shipping companies that ensured participation in social life and sent two elderly people to the common merchant , a forerunner of the later Chamber of Commerce .

Ships

Owning and building ships was heavily regulated in Hamburg. On the one hand, the ships usually belonged to several parties who were usually captains or merchants. Merchants distributed the goods to several ships in which they usually had a share in order to limit the risk of loss due to the sinking of ships. The city preferred ships from Hamburg citizens for loading and unloading. There was a ban on non-Hamburgers from participating in Hamburg ships. The shipping company was already regulated in the Hamburg maritime law of 1301.

The Hamburg maritime law of 1292, which is available in a codification of 1301, had similarities to the regulations in the Rôles d'Oléron . The other legal system has been taken into account. The regulations found their way into later Hanseatic maritime regulations and also the law of the sea in Wisby .

Ships were only allowed to be built on behalf of Hamburg citizens; in the Recess of 1412, the size of the ships was limited to 100 herring loads and a draft of six Luebian cubits in order to limit the consumption of wood and the prices for construction timber. Shipbuilding outside the city resulted in the loss of citizenship. The sale of ships was only allowed to other Hamburgers within ten years. Burspraken repeatedly renewed the size restrictions for the ships.

The handling of goods and the number of ships cannot be determined for the Middle Ages. Deggim names 1,556 ships for the year 1620 and for 1629, more precisely, 2,610 sailed ships in 1971. For 1665 is 220, for 1672 of 277 Hamburger ships with a total load of 21,258 load ( 2 tons approximately ) is assumed. The average load in long-distance trade was 200 load and 5.5 load in Upper Elbe traffic.

For the years 1369, 1399, 1400 and 1418 there are still the work and pound customs books in the archives with information about the goods, ship and ownership. Pound tariffs were used to finance the armed conflicts of the Hanseatic League, they were taxes on the value of goods, the taxes were between 1/360 and 1/240 fractions of the value of goods.

Hanseatic period

In the 13th century, Hamburg had to acquire privileges in foreign ports by granting privileges to merchants from these places (contract with the Land Wursten, 1238), with Flanders (1268). The Burspakenartikel of 1435 later restricted these granted privileges, guests were only allowed to sell them to other guests after three days of goods on offer in the city.

The Hamburg merchants joined the merchants' Hanse when necessary in order to benefit from the advantages of the Hansekontore. In the Hamburg maritime law, citizenship was obliged in 1301 to pay a contribution to the Hanseatic League and to St. Marien on the journey to Flanders. Despite the establishment of the Hansekontor in Bruges , a Bursprake was instructed to take part in the morning languages of merchants in Utrecht, Oosterkerke and Hoeke . These cities apparently continued to run despite the construction of the Bruges stack.

There were regular ship connections between Hamburg, Amsterdam, Rouen , Berlin and Bremen with fixed tariffs and mutual preferential treatment of the skippers from the respective city (1598, 1613, 1650 there was a restriction of this most-favored treatment to grain, wood and salt).

Hamburg never officially joined the Hanseatic League, but the city had been represented there since the first Hanseatic League in 1356.

In the first war between the Hanseatic cities and Denmark's King Waldemar VI. In 1362 a pound tariff was raised to finance it , the account recipient of which was the Hanseatic League. Three hundred years later, convoy money was introduced to protect against pirates.

Trade was disrupted by increasing piracy , especially on the North Sea and the Frisian coast. The city set up a fleet of warships under the command of councilors Nikolaus Schoke and Simon of Utrecht . They won several victories over the pirates. The story of the Likedeelers and their leaders Klaus Störtebeker and Gödeke Michels , who were executed on Grasbrook around 1400, has remained known.

In 1482, Emperor Friedrich III. the city the right to stack . Now, like the city of Stade 200 years earlier, Hamburg was able to force all merchants passing the Elbe to offer their goods in the city. This claim was emphasized by armed guard vehicles, which forced merchant ships traveling down the Elbe at the Bunthäuser Spitze , the southern tip of the then Elbe island of Moorwärder , to approach Hamburg via the Norderelbe instead of avoiding the duty to pay taxes on the way across the southern Elbe. In the 16th century the cities of Harburg, Stade, complained Buxtehude and Lueneburg in the Supreme Court on their right to free navigation, as the Süderelbe the main power in Elbdelta was on the Hamburg its sphere could not expand. The Hamburgers thereupon commissioned the painter Melchior Lorichs to draw up a map of the Lower Elbe. In 1568 this one meter high and twelve meter long Elbe map was presented to the court, which reduced the size of the southern Elbe and enlarged the northern Elbe. In addition, all road markings and beacons were drawn in, which emphasized the importance and concern of the city of Hamburg for the river. Fifty years later, in 1618, the verdict was passed: The north and south Elbe were considered a river on which the Hamburg privileges were to be applied.

The city fortifications were expanded in 1547 and the parts of the (Gras-) Brooks near the city , an offshore island facing the Elbe, were included. The Kehrwieder and Wandrahm residential districts were built here ; the part in front of the city wall was used as pasture. Dat Deep , later the Customs Canal, was now within the city; at the headers and the quays only loading and unloading could be done.

Commercial port until the end of the 18th century

With the expansion of the city's fortifications from 1616 to 1625 , the inland port was enlarged and the Baumall reinforced, but by the end of the 17th century it had to be expanded into the Elbe as a Niederhafen . But since these systems were no longer sufficient after a few years, a number of duck dolphins were rammed into the Elbe in 1767 , to which the big sailors could moor. The transshipment took place on the water, the goods were transshipped with the ship's own loading gear onto smaller ships, ewer and barges and transported via the numerous canals and waterways to the stores and markets of the city. In 1795 a second row of dolphins followed, reaching as far as the Jonas , the Johannes bastion of the former city wall, today marked by the promenade of the Johannisbollwerk . The upstream facility created in this way was called Jonashafen .

Trade Policy in the Early Modern Era

The German-Roman emperors were aware of the importance of the trade taking place via the port of Hamburg and the associated supply of the empire, and they promoted the city through privileges. In 1359, Charles IV granted the city the right to catch and judge sea and land robbers, and in 1365 he granted the privilege to hold a three-week fair at Whitsun. The size of the catchment area is evident from the invitations sent to this market: Bohemia, Bavaria, Hungary, Austria and all principalities and merchants along the Elbe were invited, as well as Flanders and Westphalia. Soon after the death of Charles IV, in 1383 at the latest, Hamburg decided not to hold this market. In 1482, Emperor Friedrich III. gave the city the right to stockpile , with which merchants could be forced to offer their goods for a certain period of time.

Due to the privileges it had received, the city council maneuvered between a position as a Countess Holstein city and that of a free imperial city, which, however, delayed the payment of taxes to the empire and sometimes failed to do so. When Denmark's influence on Holstein increased at the end of the 16th century and the weakening of Hamburg's position due to tariff levies on the Elbe (1611) and the founding of the Danish port of Glückstadt (1617) became foreseeable, Hamburg sought the proceedings that had been going on before the Imperial Court of Justice since 1548 its recognition as a free imperial city .

Hamburg accepted the judgment of 1618, Denmark only waived the revision in the Gottorp Treaty in 1768. In the Catholic Habsburg emperors, the city did not have strong support against Denmark, as Austria and Denmark formed an alliance against Sweden in the Thirty Years War .

The London Hansekontor, the Stalhof , was closed by Elizabeth I in 1598 ; expelled the English envoys and merchants from Hamburg. At the same time the London office in Stade was closed, the importance of the Hanseatic League as a strong association of merchants from several cities decreased rapidly. The Merchant Adventurers finally relocated their branch from Antwerp to Hamburg in 1611, and more merchants from Flanders settled in Hamburg after Spain had conquered the southern Netherlands. The restrictions on acquiring citizenship have in fact been relaxed.

Numerous Huguenots from France settled in Hamburg and brought good connections to the French port cities with them, especially Bordeaux , with which there had been good trade relations since the Middle Ages.

In 1619 the Hamburger Bank was founded on the model of the Amsterdam Bank .

To protect the ships from pirates and capture, the Hamburg Admiralty was founded in 1623 , which had its own ships and received its funds through a separately levied admiralty duty. Since the ships of the Admiralty were insufficient for protection on more distant routes, the convoy deputation was founded in 1662 . The contributions for the required ships were shared between the council and the admiralty, initially two armed merchants, the Wapen von Hamburg and the Leopoldus Primus were built. The surcharge for financing, the convoy money, was differentiated according to the shipping area and was between one and a half percent of the cargo value.

Charles Colbert , the French foreign minister, founded the Compagnie du Nord in 1669 , which was supposed to establish the independence of trade between France and the Baltic Sea region and employed Hamburg merchants for trade in order to make themselves independent of Amsterdam merchants. The city tried to maintain its neutrality in the good relations with France and refused to expel the French ambassador d'Asfeld in the Dutch War of 1674 . Trade with France and the procurement of freight - French ships played only a subordinate role in the Baltic Sea trade - opened up products from the West Indian colonies, especially sugar, in addition to the long-standing wine trade.

In 1716, Hamburg signed a bilateral trade agreement with France, thereby consolidating its neutral stance in trade matters. In the wars of the early 18th century, this neutrality - even without formal contracts - led Hamburg merchants to trade with both parties to the conflict and sometimes to the Swedish Stade or the Danish Altona to circumvent the regulations of the Reich . The protective tariffs from 1749 and the mercantilism of Prussia disrupted Hamburg's trade. In anticipation of a conflict, the city strengthened Austria, which was dependent on Hamburg for its copper exports, in which the port had a share of twenty percent. In the resulting Seven Years' War , Hamburg contributed 0.6 million guilders, a disproportionate share of 8% to the imperial contributions and granted 2.1 million guilders credit.

Due to trade, the city grew in prosperity and was the second largest in the empire after Vienna at the beginning of the 18th century. Hamburg's neutrality and the diverse trade relations meant that most European countries had diplomatic missions in Hamburg , which were also helpful in initiating new business.

Hamburg was the last state to ratify the Federal Act in 1815 .

whaling

Hamburg ships have been whaling since 1643, initially from the Netherlands and later also from Hamburg. The Danish King Christian IV allowed the Greenland voyage and thus whale hunting in his duchies . In neighboring Altona, a Mennonite shipowner was given the privilege of founding a Societas Groenlandiae . Hamburg ships - mostly with captains and crews from the North Frisian Islands - made 6,000 voyages for whaling by 1861. Many well-known merchants were involved in the ships, including the Roosens, Amsincks, Hudtwalckers and van der Smissens,

The main purpose of whaling was to obtain oil for lighting, but all other parts of the whale were also used. Because of the unpleasant smell when the oil was burned, the base of the whalers was in the western suburb of St. Pauli on the Hamburger Berg.

Age of groceries

| percent | total | |

|---|---|---|

| sugar | 32.89 | 3,490,955 |

| Wine | 10.02 | 1,063,141 |

| Wool | 6.40 | 678.995 |

| cotton | 4.79 | 508.050 |

| indigo | 4.45 | 472.075 |

| tobacco | 4.41 | 467,700 |

| oil | 3.62 | 384.414 |

| coffee | 2.40 | 255.117 |

| Fires | 1.96 | 207,615 |

| Spices | 1.88 | 199,699 |

| ginger | 1.67 | 177.155 |

| fruit | 0.62 | 66,294 |

| Almonds | 0.42 | 44,820 |

| fish | 0.01 | 1,345 |

| total | 10,615,198 |

The type of goods imported via the port of Hamburg changed due to the colonies conquered by the colonial powers. Colonial goods such as spices, silk and tea were imported from merchants via middlemen and found good sales. At the end of the 16th century, Sephardic Jews from Portugal and refugees from the Netherlands settled in the city. They had good contacts with the merchants of their old homeland and had relatives in the Portuguese colonies and thus brokered imports from Brazil. They began to build up a sugar industry, which in the following years assumed a similar importance as beer production in the Middle Ages. Through the Huguenot refugees, contacts arose in later years with the sugar and coffee-growing areas on the French West Indies, whose products were shipped via French ports, especially Bordeaux.

In 1756 there were over 300 (1807: 428) sugar boilers in Hamburg, mostly small businesses with fewer than eight employees, which produced a fine white sugar that was very popular in Central European sales areas and was sold as far as Austria. In 1778, 21% of Santo Domingo's sugar production ran through the Port of Hamburg; at the same time, the city was the main hub for coffee with 25 million pounds.

A direct call to the French West Indian colonies by Hamburg ships was initially not possible, in 1796 a Hamburg ship landed for the first time on the Île de France . The island of Saint Thomas , which was Danish until it was sold in 1917 and formed one of the largest storage areas in this area, was significant for the West India trade .

With the continental blockade, sugar boiling was practically discontinued, after which the production of sugar from sugar beet outside of Hamburg quickly gained in importance.

The Napoleonic wars at the beginning of the 19th century brought about a temporary stoppage of growth when the Elbe blockades and continental barriers led to the collapse of trade and the city was occupied during the so-called French period from 1806 to 1814.

The end of the French occupation coincided with the independence of several Spanish and Portuguese colonies in South and Central America, which from then on could be started directly without the intervention of intermediaries. The Godeffroy family had trading establishments in Havana , San Francisco and Valparaíso , from where Cesar Godeffroy (1813–1815) opened up the western South Seas and also acquired plantations here. On the initiative of Godeffroy, the Société commerciale de l'Océanie was founded in Hamburg , which had its only branch in Tahiti and from here it became the most important trading company in Eastern Polynesia.

The products of East Africa - the coloring raw material orseille , sugar, cloves and ivory - came mainly via Zanzibar , where William Henry O'Swald ran the business of his family, who had made a fortune exporting cowrie shells from the Indian region to West Africa. In 1859 William H. O'Swald negotiated a trade agreement with Mâdjid ibn Sa'id , the Sultan of Zanzibar, for the Hanseatic cities of Lübeck, Bremen and Hamburg, which was very favorable for them, and the Sultan also benefited from the resulting increased tax revenue .

The trading company Hansing & Co , whose managing director Justus Strandes played a key role in the establishment of the colony in German East Africa , was also active in Zanzibar .

The merchants and shipowners

World trade and the founding of shipping companies and shipping lines led to the considerable wealth, advancement and fame of some Hamburg merchant families , who were called pepper sacks in the pun . As in the days of the Hanseatic League, individual merchants took on diplomatic tasks and negotiated contracts with other states or princes on behalf of the city council, which in the days of small German states acted like an independent principality. The Hanseatic cities sent diplomatic representatives to various government seats. In 1869 such diplomatic missions were perceived by the North German Confederation . Consular representations, which were set up in numerous port cities from 1796 ( Philadelphia ) to 1851, became important for trade .

The increasing size of ships and the diversification in trade brought ship ownership into the hands of shipowners who had their business objective in the provision of ship space and transport capacity. The construction of iron ships and steam-powered ships resulted in increasing costs, which were raised by established family businesses and also by corporations from the middle of the 19th century ( HAPAG , Hamburg Süd ).

Significant families included:

- Amsinck family

- A family that immigrated from the Netherlands at the end of the 16th century and was active in the cloth trade. In the 19th century, they became prosperous in the cloth and textile trade in South America and provided senators and mayors.

- Smelted copper ores from Chile in their own refinery , the predecessor company of Aurubis AG

- They acquired Richter's shipyard to build the ships they needed. had trading companies on numerous islands in the South Seas and on Australia. They also took part in whaling in the South Seas.

- Ferdinand Laeisz , originally a hat maker, was active in the South American business and imported rubber, sugar, cotton, coffee and tobacco to Hamburg. The family ran the shipping company F. Laeisz and founded other shipping companies ( Hamburg Süd , Deutsche Levante-Linie , Deutsche Ost-Afrika Linie ) and participated in others.

- Roosen

- Descendants of Gerrit Roosen , a Mennonite family of Dutch origin who lived in Altona and Hamburg

- Berend I. Roosen (1705–1788) was involved in 21 ships and operated whaling in the North Sea (among others with de Hermann ). Thirteen ships were used on the White Sea voyage to Archangelsk to bring grain to France.

- They had a stake in the Kramer shipyard on Reiherstieg . A list of the family's ships lists one hundred and forty family-owned ships for the period from 1717 to 1880.

- Rudolph Roosen (1830–1907) was a Hamburg senator.

- were and are a merchant family that provided several senators and mayors.

- Georg Heinrich Sieveking made a fortune trading with North America and the French Atlantic ports. He ran his business together with Caspar Voght for a long time . As Hamburg ambassador in Paris, he achieved the lifting of a trade embargo against Hamburg.

- Sloman

- Robert Miles Sloman (1783–1867), son of an English shipbroker, founded Germany's oldest existing shipping company Rob. M. Sloman , who operated liner shipping to England and North America from 1836. a regular parcel trip to New York was started and emigrants were taken to the United States as cargo . In 1849 the Helena Sloman was the first steamship to go into service for the North Atlantic traffic, but it went down on the third voyage.

- Henry B. Sloman (1848–1931), who made a fortune in Chile mining saltpetre and who commissioned the Chilehaus , is also part of the family.

- Woermann

- Carl Woermann and his son Adolph Woermann expanded trade with Africa and, with the Woermann Line , set up a regular ship connection with Nigeria , Cameroon and Namibia , what was then German South West Africa . The trading house played a controversial role in the colonization of Africa , which was publicly discussed after the Woermann Line had shipped German troops to Namibia to fight the Herero uprising in 1904 and made good profits.

- Jauch

- The Jauch first appeared in Hamburg at the end of the 17th century. In 1752 the Jauch relocated their trading business from Lüneburg, which was becoming economically insignificant, to Hamburg. Johann Christian Jauch senior and his sons and grandchildren built JC Jauch & Söhne into the dominant timber trade in Hamburg with business relationships in Russia and overseas. The company was based at the Holzhafen on the city dike.

- Jauch Gebr. Import & Export mainly operated the coffee trade with the Jauch coffee plantations in Guatemala. Walter Jauch founded Jauch & Hübener in Hamburg , the largest German insurance brokers and, until the Second World War, the largest continental European insurance brokers.

The time of the continental lock

After the Battle of Trafalgar (October 21, 1805), Napoleon prohibited trade in goods to and from the British Isles. To enforce this continental barrier, u. a. British goods confiscated in French-controlled areas and British traders prosecuted. Towards the end of 1807, Napoleon extended the block to neutral shipping; further gradual tightening followed.

Napoleon's protectionism (protecting one's own economic space) damaged the continental economy. The smuggling flourished. With British imports continuing to come to the continent, Napoleon declared that he must take the entire North Sea coast under his supervision. On December 13, 1810 , he annexed areas at the mouths of the Ems , Weser and Elbe as well as the Hanseatic cities of Bremen , Hamburg and Lübeck .

The continental barrier polluted occupied territories especially in those areas where one was dependent on the purchase of British goods or colonial goods and / or on exports to Great Britain. The northern German port cities were badly affected by the lockdown due to a decline in shipping and an outflow of capital to Great Britain. For example, the trade in bulk goods such as wood and grain between Great Britain and Germany collapsed completely (Great Britain was largely deforested; during this time there was a lack of wood in many places ). In many places, social unrest was the result. The continental blockade ended in 1814. The year without a summer also hit Hamburg in 1816 .

Port expansions in the 19th and early 20th centuries

After 1814 and the reorganization of Europe ( Congress of Vienna 1815), trade quickly increased again. The beginning of industrialization caused the flow of goods to increase. Efforts for independence by the Spanish, Portuguese and French colonies stimulated direct trade across the Atlantic. Branches of Hamburg trading houses were set up in numerous cities, often under the management of family members of the owners of the Hamburg houses. The imported goods were sugar, coffee, and later also rubber and saltpetre . On the outward journey, textiles and tools and, in smaller numbers, emigrants were transported to South America. Trade with North America (tobacco and cotton) was reserved for the Bremen merchants, who early on took emigrants to the United States in the opposite direction.

In 1835, at a distance from the other port facilities in front of the Hamburger Berg , today's St. Pauli, at the former whaling port , a separate steamship dock was built to keep the danger of fire away from the sailing ships, in 1840 the first St. Pauli jetties were built at this point . However, the measures soon proved to be insufficient to cope with the growing trade flows and transshipment possibilities.

Hamburg instructed a commission (J. Walker - W. Lindley - H.Hübbe ) to develop a planning concept for the port expansion, which was presented in 1845 and provided for a dock port based on the London model and which was not implemented, as obstacles from the necessary locks were feared. At the initiative of the Commerzdeputation, a different concept with quay facilities for immediate cargo handling without long storage, with mechanical support from cranes and rail links was presented and finally implemented. In 1860 the Senate issued the general plan for the expansion of the Port of Hamburg ; this was implemented by Johannes Dalmann , the later hydraulic engineering director of Hamburg.

A system of connecting canals between the harbor basins and only a relatively small number of locks reduced sediment deposition, primarily by directing the flow of water during the tides. The Ellerholz lock and the Rugenberger lock belong to this system.

Technical progress and growth

In the nineteenth century, several factors led to an expansion of sea trade in the Port of Hamburg:

- the world population grew rapidly; likewise the population of Germany ;

- new raw materials overseas were developed.

- The shipbuilding industry increasingly used iron, initially for the masts and later also for the overall construction of the ships. The ship sizes, which had only increased slightly since the Middle Ages, increased considerably due to new construction methods and exceeded the 1,000 ton mark.

| Ship type | Occurrence | length | Load capacity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prahm | 13-18 Century | 12 | 7.5 t | for example for salt transport on the Stecknitz Canal |

| Cog | 12-14 Century | 20-30 m | 80-200 t | Common standard ship |

| Holk | 11-15 Century | 25 m | 100-20 t | common flat type up to 300 t |

| Kraweel | 12-15 Century | 25-30 m | 120 t | different planking than Holk, therefore faster |

| Carrack | 14.-16. Century | up to 40 m | up to 500 t | Three-master / later also four-master |

| Pinass ship | 16.-17. Century | 35-45 m | East Indiaman | |

| brig | 19th century | 50 m | 140-350 tons | Two masters, also Schnau with different rigging |

| Barque | 19th century | 90 m | 1500-4500 GRT | Three / four masters |

| Logger | 18. – 19. Century | up to 20 m | 100 t | Coastal cargo ship, three-master |

| Full ship windjammer | 19th century | 110 m | 4000 t | Four- / five-masted steel masts |

| Clipper | 19th century | 45-100 m | 500-1800 GRT | very fast |

By improving the ship's engines, it was then also possible to run economically viable steamships, which gradually replaced the sailing ships.

The motorization of the ships led to a smaller number of crews who were no longer able to carry out the unloading and loading work on the ships, whose cargo capacity was increasing, on their own. From 1840 the loading work was increasingly carried out by rural day laborers (the Schauerleuten ). The occupation of the showers was largely erratic and there were always times without employment. There was no regulated employment agency and the economic situation of the less organized workers led to the Hamburg port workers strike in 1896/97 .

Electric winches on board and electric cranes on the quayside, for example built by Kampnagel in Hamburg, made charging easier. The construction of the cranes as a portal crane made it possible to load them directly onto railway wagons that could be brought close to the edge of the quay.

The port was connected to the railroad from 1866 onwards with the Quaibahn , which was later expanded to become the Hamburg port railway , to the Berlin train station . In 1872, the railway connection via the new Elbe bridges went into operation. Shipping the goods to Harburg and reloading there was no longer necessary.

In addition to unloading and loading on the land side, some of the goods were unloaded on the waterside via barges and ewer and transported further. The onward transport then took place via smaller seagoing vessels or with inland waterways across the Elbe inland.

There are no long-term consistent trade statistics, but there are always statistical surveys for different years:

- The loading volume was 14 million tons in 1855, 21 million tons in 1860, 34 million tons in 1871, half of which were seaward. The number of ships per year was 5200 ships during this period, with slight fluctuations, the size of the shipping space grew from 1.2 to 1.9 million GRT .

In terms of value, Great Britain had the largest share of imports in 1872 with 504 million marks (USA: 114 million marks, Brazil 54 million marks). The goods were distributed according to the countries: textiles 155 million marks, coffee 141 million marks, raw sugar and tobacco each 31 million marks.

The onward transport of the goods took place to a considerable extent by rail as early as 1875: Berlin-Hamburg Railway : 3.8 million t, Lübeck-Hamburg 0.8 million t, Venlo-Hamburg 1.2 million t. 3.9 million t were transported further by barge in the direction of the Upper Elbe.

The great Grasbrook

The Elbe island of the Grasbrooks , formerly a swampy area in the river splitting area, located directly in front of the city, was particularly suitable for the port expansion . In the 16th century, the area was divided with a breakthrough and the relocation of the Norderelbe. The Small Grasbrook is thereafter on the southern side of the river, the city near Big Grasbrook was used primarily by the end of the 18th century as pasture. It could be reached via the Brooktor and the associated bridge, roughly at today's Brooktor bridge . In 1532 the northern part of the Großer Grasbrook, the Kehrwieder and the Wandrahm were included in the fortified city. The defenses from the 17th century ran roughly at today's Sandtorkai, in front of a ditch almost 70 meters wide. At the Ericusspitze with the Ericusgraben, parts of this facility can still be seen today. When the city wall was demolished after the French era at the beginning of the 19th century, open spaces were created in the immediate vicinity of the city. The western part of the city moat on Kehrwieder was expanded into a new basin in 1830 by deepening and widening and later expanded to become the Sandtorhafen.

The southern part of the Großer Grasbrook, located directly on the Norderelbe, served the ship carpenters as a shipyard. In 1844 the first Hamburg gasworks was built here, which was in operation until 1976.

The first port basin , the Sandtorhafen , was created under the direction of Hydraulic Engineering Director Johannes Dalmann from 1863 to 1866 on the Großer Grasbrook in front of the former sand gate of the razed city wall. The shipbuilders and shipyards previously resident here had to move to the other side of the Elbe to the Kleiner Grasbrook and to Steinwerder .

The newly created quays of the northern Sandtorkai consisted of wooden bulwarks, later at the southern Kaiserkai , completed in 1872, of clinker brick walls on which the seagoing ships could dock directly. They were considered to be masterpieces of structural statics, as they had to withstand the earth pressure on the one hand and the different water pressures caused by the tides on the other. They mostly had crane systems that could move on rails parallel to the edge of the quay for general cargo handling, rail connections and simple quay sheds that were used for sorting but not for storing goods. For the first time, this enabled goods to be handled directly in railway wagons or carts, and it was considered the most modern handling system in the world at the time. Within a few years, further harbor basins were built on the Großer Grasbrook, such as the Grasbrookhafen (1876), the Magdeburger Hafen (from 1872) and the Brooktorhafen (around 1880) with a passage between the two.

For the siding, a railway bridge, the Große Wandrahmsbrücke , was built over the Oberhafen between Deichtor on the former outskirts and the Theerhof at the eastern end of the Großer Grasbrook . With the expansion of the port, the problem of the bridge connection over the Elbe also had to be resolved; a place should be found where shipping would not be hindered. From 1868 to 1872 the first two Elbe bridges were built for the Hamburg-Venloer Bahn over the North and South Elbe ; followed by the two road bridges Neue Norderelbbrücke (1887) and Old Harburg Elbbrücke (1899) with their impressive sandstone portals. The railway line ran along the upper harbor , bridged from the island Baakenwerder the Norderelbe to Veddel , went through Wilhelmsburg and crossed the Finkenriek Süderelbe to time to province Hannover belonging Harburg . During the Empire , the port facilities were connected to the Cologne-Minden Railway Company by the Cologne-Minden Railway Company (from 1879 part of the Prussian State Railways ) when the Venlo train station went into operation (from 1892 Hannoverscher Bahnhof) in the eastern part of the Großer Grasbrook near Magdeburg harbor . For road traffic, the free port bridge was built from 1884 to 1887 . To connect the main station , which was completed in 1906, the Oberhafenbrücke was built from 1902 to 1904 as a swing bridge for road and rail traffic.

In 1875, Johannes Dalmann had the imposing "Kaiserspeicher" ( Kaispeicher A ) built on the prominent and widely visible tip of the Kaiserkais, the Kaiserhöft , previously called Johns'sche Ecke after the shipyard located there. In particular, its tower with a time ball system , the signal ball of which fell every noon at exactly twelve o'clock and enabled the skippers to precisely regulate the chronometers , which are important for navigation , was considered the landmark of the port for many decades until it was demolished in 1963 and replaced by a monumental, but simple storage structure was replaced. The Elbphilharmonie has been built on its gutted outer walls since 2007 , a much discussed prestigious project of the city.

The free port

to be demolished because of the free port buildings”, view of the inland port, on the right the Kehrwiederviertel before the demolition for the Speicherstadt.

Illustration in Die Gartenlaube 1883

After the Franco-Prussian War from 1870 to 1871, pressure grew on the previously Free Imperial City of Hamburg to join the newly founded German Empire and the Zollverein . With the customs union agreement of May 25, 1881, the negotiations about the affiliation found a compromise. Hamburg lost its status as a duty-free national territory, but a defined area, which included the large and small Grasbrook, should be declared as a free port for foreign customs. There, the free transshipment and storage of goods as well as the duty-free processing of imported goods remained possible within the set limits. The access via the Lower Elbe was also duty-free and the customs administration was in Hamburg's hands.

In this context, another general plan for the expansion of the port of Hamburg was approved in 1883 . In order to create an area that was both within the free trade zone and close to the city center, the Kehrwieder and Wandrahm districts, which were inhabited by 20,000 people, had to be cleared and 1,000 residential buildings and warehouses laid down. The Speicherstadt was built here in just a few years and was handed over to its destination on October 15, 1888. From 1886 to 1899 the southern development of the Grasbrookhafen, new facilities at the Strandhafen as well as export and collection sheds to the west and east of the Magdeburg harbor were built. In this construction phase, the Versmannkai and the fruit sheds A and B were built around 1897.

The connection to the German Reich and the establishment of the free port turned out to be favorable for the further upswing of Hamburg, contrary to the long-standing fears and resistance of the conservative Hamburg merchants. Within a few years, the port, and with it its free port borders, had to be expanded many times over. Since possible areas on the side of the Elbe near the city were now occupied, further development continued on the south side of the North Elbe. From the middle of the 19th century, shipbuilders and shipyards occupied properties on the Kleiner Grasbrook and Steinwerder. In 1869, the handling of flammable goods was banned to the other side of the Elbe and the petroleum port was established. In order to create a navigable route outside the free port, between the city center and Speicherstadt, the sailing ship port was moved from the inland port in 1888, a few years earlier the core of the port, to the Kleiner Grasbrook and the wooden port from the upper port to Billwerder Bay. The waterway that still exists today was created from Dat Deep with the Oberhafen, Zollkanal and inland port, separating the old town and new town from the Speicherstadt and HafenCity.

The free port area was subsequently slightly changed several times. With the inclusion of the container terminals at Waltershof and Altenwerder , the maximum expansion was finally achieved. With the deedication of the port area on Kehrwieder, the area was initially slightly reduced, the customs station was on the street “Am Sandtorkai” (2003) and in the following year until shortly before the Hamburg Elbe bridges . This meant that the area north of the Norderelbe was practically outside the free port area.

In December 2009 the Hamburg Senate decided to apply for the closure of the free port on January 1, 2013. The federal government at the time launched the necessary draft law in September 2010; the Federal Council approved the draft on December 17, 2010. The repeal became effective on January 1, 2013 through the “Law to Repeal the Free Port of Hamburg” of January 24, 2011 ( Federal Law Gazette I p. 50).

Kleiner Grasbrook and Steinwerder

Between 1888 and 1893 the Hansahafen and the Indiahafen were built on the Kleiner Grasbrook. With a depth of the basins of 6.5 meters at medium low water as well as enlarged quays and shed rows , the growing ship sizes and quantities of goods could be taken into account. The system of river ports in the rear region located as Vltava , Saale - and Spreehafen that enabled access from inland vessels in the port basin, without barriers Elbschiffsverkehrs and direct handling and further shipment. The technical development also brought changes in the loading and lifting equipment with it, steam and electric cranes increased the handling speed many times over.

The further expansion of the port opened up the areas in western Steinwerder, in 1887 the Kuhwärder port with the premises of the Blohm & Voss shipyard was built, in 1899 the Kaiser-Wilhelm port and in 1901 the Ellerholz port , both of which were owned by the Hamburg-American Packetfahrt-Actien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG). These ports were also deposited with a system of river ports and canals that created a rearward passage from the Veddel to the Köhlbrand .

emigration

The transport of migrants did not play a major role in port operations at the beginning of the 19th century, as the proportion of journeys to North America was lower for Hamburg than for Bremen. Passengers were accommodated in uncomfortable crates, which could be expanded after the ship's arrival and converted back into hold; the sanitary conditions were poor.

In 1832 Hamburg still feared difficulties with the appearance of emigrants in troops. Since the passengers lived or lodged in the city until the ship was full and had to eat for themselves during the passage, emigration was a considerable economic factor. For humanitarian reasons, Hamburg passed an emigration ordinance on February 27, 1837 (which stipulated, for example, minimum provisions and bunk sizes); this made Hamburg more progressive than other ports. However, the rules were later weakened due to intervention by shipowners. From 1850 the annual number of passengers quickly rose to over 50,000. In 1855 the city founded the deputation for emigration .

During the Atlantic passage of the sailing ship "Howard" in 1857, 37 of 286 passengers died. The crossing had taken an extremely long 96 days. New York newspapers then criticized Hamburg's legislation and inadequate health checks before departure. The Mecklenburg-Schwerin government (from which many emigrants came to Hamburg) complained; likewise the Australian government. The mortality on Hamburg ships between 1854 and 1857 was four times higher than on Bremen ships. A sufficient medical examination before the voyage could not be enforced against the shipowners due to economic considerations.

The regulations were extended in 1868 after there were 100 deaths among 450 travelers on the voyage of the »Leibnitz« in the winter of 1867. From now on, a medical examination before embarkation was carried out by a city doctor.

The proportion of steamships increased; The passage time on these was significantly shorter. After 1890, more and more pure passenger ships were commissioned, which brought a significant improvement in travel conditions. Here Hamburg’s HAPAG and Bremen’s Norddeutsche Lloyd were in direct competition for the largest and fastest ships.

After 1880, many people came from Eastern Europe, especially Polish and Russian Jews , and moved from Hamburg to the United States of America, among other places . After the outbreak of the cholera epidemic of 1892 (an unproven connection with the migrants was suspected), the emigrants were kept away from the city area. They had to stay in the HAPAG passenger halls on Amerikakai and later in the emigration halls built in 1901 on the Veddel , of which the Ballinstadt Museum reminds us today. The facility was expanded until 1905 and consisted of around 30 individual buildings with sleeping and living pavilions, dining halls, baths, churches and a synagogue as well as rooms for medical examinations. From the adjacent Müggenburger Zollhafen there was a direct navigable connection through the Veddel Canal to the Ellerholzhafen and Kaiser-Wilhelm-Hafen with the HAPAG quays, where the emigrant ships left. In addition to the social and health aspect, this facility was another source of income for the shipping company. Between 1850 and 1915, 4,179,489 people emigrated via the port of Hamburg.

The Köhlbrand and Waltershof

The growing need for territory in the Port of Hamburg exacerbated the centuries-old conflicts of interest with the neighboring cities of Altona and Harburg, both of which had been Prussian since 1866. Since the Gottorp Treaty of 1768, all Elbe islands and lowlands between Billwerder and Finkenwerder, including Kaltehofe, Peute, Veddel, Grevenhof, Griesenwerder, Pagensand and the northern part of Finkenwerder, belonged to the Hamburg Elbe area . The border with the Harburg district ran at Finkenwerder Landscheideweg, and Altenwerder and Wilhelmsburg also belonged to the Prussian area. In a total of three so-called Köhlbrand contracts between Hamburg and Prussia between 1868 and 1908, common interests in the expansion of the Elbe were regulated, as a result of which several new harbor basins were created in the area of today's Waltershof .

From November 21, 1896 to February 6, 1897 there was an eleven-week strike, the Hamburg port workers' strike . It is considered to be one of the largest labor disputes in the German Empire . It comprised nearly 17,000 workers at its height and ended in the complete defeat of the strikers. The dispute had a significant impact on Hamburg's economy and also caused a stir outside of Germany. The strike was mainly carried out by groups of workers who were barely unionized and whose working conditions were characterized by discontinuity. They faced well-organized entrepreneurs. The events gave the conservatives and the Reich government (1894 to 1900 under Chancellor zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst ) an opportunity to attempt an intensified policy of repression against the Social Democrats two years later with the prison bill .

In the expanding port, the volume of traffic increased, in particular the increasing number of port and shipyard workers had to get to more and more distant places in the port on the other side of the Elbe. At the beginning of the 20th century, the St. Pauli Landungsbrücken were created as a mooring and landing point for the port launchers . At the same time they became the starting point for the seaside resorts and the Lower Elbe. To the west of the facility is the city-side access to the St. Pauli Elbe Tunnel , now known as the Old Elbe Tunnel . It was opened in 1911 and leads at a bottom depth of 24 meters and over a distance of 388 meters to the other side of the Norderelbe to Steinwerder . Access is possible via spiral stairs or elevator cars, also for vehicles. The historic elevators were able to transport 9,000 people per hour, giving port and shipyard workers a quick, uncomplicated and weather-independent route to their workplaces.

Before the First World War , Hamburg had the third largest port in Europe and fourth largest world port after London and Rotterdam. With the general plan for the expansion of the port of 1908, the Dradenau and Finkenwerder were declared port expansion areas and the planning for further port basins in Waltershof began. An outer port, a petroleum port, three sea ports, a river port, an ever port and a yacht port were to be created. The implementation continued until the First World War, but could only be continued in a modified version in the 1920s.

During the First World War, Great Britain practiced a comprehensive sea blockade against the German Empire, which until then had, among other things, imported large quantities of grain and other food by ship.

With the State Treaty on the transition of waterways from 1921 (WaStrÜbgVtr), sovereignty over the Elbe and its tributaries and canals was transferred to the German Reich . Hamburg secured the supervision of the waterways from Oortkaten in the east to Blankenese in the west, while at the same time obliging the Reich to ensure that "as a rule, the largest ships can reach Hamburg using the floods".

In 1929 the Hamburg-Prussian port community was united , with which the villages of Finkenwerder, Francop , Moorburg and Altenwerder were defined as port expansion areas. These plans experienced in 1930, the Great Depression initially a provision.

The exclave: America harbor in Cuxhaven

The journey time of passenger ships in traffic with North America from Cuxhaven , located at the mouth of the Elbe, could be shortened by several hours. Cuxhaven was in the then Ritzebüttel office , which belonged to Hamburg. The regular service with fast steamers of HAPAG to New York was operated from Cuxhaven from 1889, whereby the passengers had to be transferred with tenders to the ships lying in the roadstead. The connection to Hamburg was made with the Niederelbebahn , which opened in 1881. Quays were built in the years that followed, followed in 1902 by the HAPAG halls with the America train station . In view of the constantly increasing size of the ships used, the system had to be expanded in the direction of Steubenhöft up to a length of 400 meters. Since 1913 the quays have been called America Harbor .

The Greater Hamburg Act in 1937 struck the Hamburg Office Ritzebüttel with Cuxhaven, the neighboring communities and the islands of Neuwerk and Scharhörn Prussia . With the fourth implementing regulation of the Greater Hamburg Act , Hamburg continued to secure the America Port in the Cuxhaven urban area as an exclave. It was only with the Cuxhaven Treaty in 1961 that Hamburg exchanged the America port for the islands of Neuwerk and Scharhörn in order to secure the option for a deep-water port in the Outer Elbe.

On August 15, 1969, the Hanseatic was the last time a liner cast off from Steubenhöft.

In 1993, Hamburg handed over ownership of the Amerikahafen to the state of Lower Saxony.

The port during the National Socialism

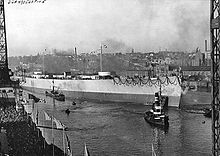

The wealth of Hamburg and the importance of the port were based on world trade, the world economic crisis went hand in hand with its collapse and in the early 1930s caused a large part of the merchant fleet to be shut down and shipbuilding orders to decline almost completely. Unemployment in the port and especially in the shipyards was up to 40 percent. The economic policy in the time of National Socialism with the restriction of foreign trade and foreign exchange prevented a recovery, as it took place in the ports outside the German Reich from the beginning of the 1930s. With job creation measures, Senate orders and in particular the orders placed by the Reich government from 1934 to arm the Wehrmacht , a pseudo- boom was created up to the beginning of the Second World War . The administration of the port and the organization of port work were restructured, the principle of leader and allegiance was to centralize the processes and align them with the requirements of the war economy . It was mainly the shipyards that benefited from these programs. The launching of the two KdF ships Wilhelm Gustloff and Robert Ley as well as the battleship Bismarck were spectacularly staged by Nazi propaganda .

The Greater Hamburg Law

With the Greater Hamburg Law of 1937, the ports of Altona and Harburg came under Hamburg's jurisdiction and there was no competition. They were attached to the Port of Hamburg and used or shut down as required. As a result of the incorporation, Hamburg was also able to dispose of industry that the merchant town had previously only had to a small extent. The striving of National Socialist Germany for independence in the provision of basic services was of particular importance. In the port there was therefore a far-reaching expansion of the mineral oil industry, especially in Wilhelmsburg and Harburg, the fishing industry in Altona and the storage and processing of grain on the Reiherstieg. After the start of the Second World War in 1939, the Navy pushed the construction of submarines at Blohm & Voss , the Howaldtswerke , Stülcken and at the Deutsche Werft . From 1940 the U-boat bunker Elbe II was built at the Vulkanhafen at the Howaldtswerke and the Fink II bunker at the Deutsche Werft in Finkenwerder .

Expropriations of port operations

As elsewhere, the Nazi racial ideology led to attacks on Jewish merchants and business owners in the port. In the first few years after the seizure of power, the repression against the companies was limited, mainly because they did not want to endanger jobs with the still high unemployment. From 1936 the foreign exchange office of the tax office controlled the companies, they had to provide lists of their assets, which in many cases they could no longer dispose of after a so-called security order . They were obliged to make special payments and compulsory levies, so that they were often forced to sell their businesses far below their value. From 1938 at the latest, the companies were transferred to non-Jewish owners as part of further aryanization measures. In the port industry, around 150 companies were "aryanized" . For example:

- The Fairplay tugboat shipping company Richard Borchard GmbH was owned and managed by the Jewess Lucy Borchardt . She had 15 harbor tugs, two ocean tugs and a cargo steamer. Until 1938, it made it possible for a number of young people to attend seaman training, which enabled them to emigrate to Palestine as part of the Hachshara . At the same time, the tug fleet offered an opportunity for illegal emigrants. From 1937 the pressure of the Nazi state on the well-positioned shipping company increased, in particular through controls, security measures and warning money imposed by the foreign exchange office. In September 1938 the company was converted into an "Aryanized" foundation under private law. Lucy Borchardt fled to England. She did not return to her hometown after the end of the war, but managed to have the Fairplay shipping company returned to her family in 1949. Today the tug company operates under Fairplay Towage throughout Europe with its headquarters in Hamburg.

- The Arnold Bernstein shipping company employed more than a thousand seafarers in the mid-1930s. From 1936 the Jewish owner was under the pressure of accusations and defamation by the foreign exchange office, and in 1937 he was arrested. In September 1937 a Hamburg special court sentenced him to two and a half years in prison, and he also had to transfer his shares. The shipping company was sold to the Holland-America Line in March 1939. After Arnold Bernstein was released from prison, he managed to emigrate to New York.

- The Köhlbrand shipyard in Altenwerder belonged to the shipbuilder Paul Berendsohn, who was of Jewish origin. In 1938 the shipyard area covered over three hectares and three helges, on which ships of up to 1,000 tons were built. Around 120 shipyard workers were employed. In 1938 the shipyard, which had a nominal value of 1.9 million Reichsmarks, was "aryanized" and in 1943 it became the property of the City of Hamburg.

- Several Jewish owners ran their businesses in the Am Sandtorkai coffee stores, such as Keller & Hess Coffee Import , Otto Hesse Coffee Agency , Tomkins, Hildesheim & Co. Coffee Import and Franz Wolff & Co. Coffee Import . All of these companies were expropriated in 1938. Likewise, the neighboring export and import company Gebr. Weigert .

Forced laborers in the port industry

The labor shortage as a result of the war was forcibly recruited in the occupied territories. Around 500,000 men, women and even children were brought to Hamburg from Western and especially Eastern Europe and used primarily in the port industry and in the shipyards or used to clean up after bomb attacks. Without exception, slave laborers were employed in all port operations . In the morning they were driven to their places of work from their accommodation, so-called company or community camps in the city and port area, cleared schools or halls, sometimes residential buildings and in harbor sheds and warehouses. The Wehrmacht transferred prisoners of war for forced labor, mostly they were interned in camps on the company premises or in the immediate vicinity. In the area of today's HafenCity alone , eleven forced labor camps are known, two of which were prisoner of war camps .

Towards the end of the war, more and more prisoners from the Neuengamme concentration camp were deployed. In order to save long distances, four outposts of the concentration camp were set up in the port from September 1944:

- the Blohm & Voss subcamp , from October 9, 1944 to April 12, 1945, with six hundred male prisoners mainly from Poland and the Soviet Union. There were at least two hundred and fifty deaths. In April 1945 the prisoners were transferred back to the Neuengamme main camp.

- the Stülckenwerft subcamp , from November 22, 1944 to April 21, 1945, with two hundred and fifty male prisoners from various countries. In April 1945 those who had survived until then were taken to the Sandbostel reception camp.

- the Finkenwärder satellite camp , Deutsche Werft, from October 1944 to the end of March 1945, around six hundred male prisoners, mostly from the Soviet Union, Poland, Belgium, France and Denmark. After several bomb attacks, they were transferred to the Bullenhuser Damm and Dessauer Ufer subcamps.

- the Dessauer Ufer subcamp , Lagerhaus G , from July to September 1944, around 1,500 Jewish women were housed here; they were used to work in the mineral oil industry and to clean up. In September 1944 they were distributed to other camps in the city. From September 15 to October 25, 1944 and from February 15 to April 14, 1945, the warehouse was occupied by prisoners working for the Geilenberg program to secure the mineral oil industry. In 1944, initially two thousand male prisoners were interned here, mostly from the Soviet Union, Poland, Belgium and France. After the camp was destroyed by a bombing raid in October 1944, the survivors were taken to the Fuhlsbüttel satellite camp. In February 1945, eight hundred prisoners were transferred back, and in April 1945 the prisoners were transferred to the Sandbostel reception camp. Sheds E, F and H on Dessauer Ufer were also temporarily set up as forced labor camps from 1943 onwards.

War destruction

From the early summer of 1944, the port was exposed to massive, area-wide air raids. Mainly the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) flew a total of 40 sorties. They were aimed at the industry in the port, especially the large refineries and the shipyards with the submarine construction. Because of their important function for the German war economy, the plants were repeatedly repaired in order to keep operations going. The last major air raid was on April 14, 1945; British troops occupied the city on May 3, 1945.

At the end of the war, 80% of the port facilities were destroyed, three quarters of the Speicherstadt and half of the port bridges, the large Elbe bridges , however, remained intact. Over 3,000 shipwrecks lay in the docks and waterways. After the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht on May 8, 1945, Hamburg became part of the British occupation zone . As a restricted military area, the port was under the control of the British military government . The reconstruction was considered to be largely complete around 1956, but Hamburg could no longer build on its former importance as a world port - with the division of Germany and the beginning of the Cold War , the port lost its Central and East German sales markets as well as its trade connections with the industries of Eastern Europe .

The container port at the end of the 20th century

Already during the reconstruction a relocation of the port became apparent. The Große Grasbrook, an ambitious expansion project almost a hundred years earlier, was only partially used. The area west of the Magdeburg harbor lay fallow until the early 1950s, and the area at Strandkai was also not used until 1964. Then a heating plant and tank farm were built there. With the emergence of changed handling techniques and the construction of the first container terminals downstream from the Elbe in the 1960s, the port operations began to move away from the Großer Grasbrook. In 1979 the first partial filling of the Sandtorhafen and the Brooktorschleuse was carried out, in 1989 another part of the Sandtorhafen was filled in and a coffee roasting plant and storage facility were built on the site.

In 1968, with the erection of the first container bridge on Burchardkai, the expansion of Waltershof to the Burchardkai container terminal (CTB) by Hamburger Hafen und Logistik AG (HHLA) began. With the construction of the Köhlbrand bridge , the Kattwyk lift bridge for the port railway and the new Elbe tunnel , all in 1974, the logistical prerequisites for the growing transport demand were created. This was followed in 1977 by the Tollerort container terminal , which was also taken over by HHLA in 1996, and the Eurogate Container Terminal Hamburg (CTH) on Predöhlkai in Waltershof in 1999 .

The port expansion law passed by Hamburg in 1961 revived the plans of the Hamburg-Prussian port community from 1929 and continued to include the former villages of Altenwerder and Moorburg for the expansion of the port . In 1973 the Hamburg Senate decided to vacate Altenwerder. The port development plan presented in 1989 also adhered to the port expansion in the southern Elbe region. In spite of massive protests from the population, Altenwerder was finally and completely cleared and torn down by 1998, only the church and the cemetery remained. In 2002 the Container Terminal Altenwerder (CTA) started operations at this point , it was considered the most modern terminal in the world.

The port economy has thus shifted further elbab, the port basins on the Großer and Kleiner Grasbrook did not meet the requirements of a seaport in terms of size, depth or space from the 1980s. The space requirements in the container ports are also different than in conventional transhipment, large storage and loading areas are required. In the meantime, numerous harbor basins have been filled in again, for example the Indiahafen , the Vulkanhafen or the Griesenwerder Hafen in order to create these parking spaces.

After the opening of the socialist countries and the opening up of the Asian markets in particular, the Port of Hamburg has developed into a world port again and is considered one of the winners of globalization. The total throughput more than doubled between 1990 and 2007; in 2008 it stagnated at 140 million tons. The proportions of bulk goods in relation to piece goods were 30% to 70%. 97% of the general cargo was sold in containers, which corresponds to a turnover of 95 million tons or 9.8 million TEU. Further stagnation is expected for 2009 due to the financial crisis.

The conversion of former port areas

The modern handling techniques and the sizes of the container ships resulted in a relocation of the port management elbab to the western port areas such as Steinwerder, Waltershof or Altenwerder. But not only the restructuring in the handling of goods and the changes to the requirements of storage, also the closure of the large shipyards from the 1980s, left extensive fallow land in the former heart of the Hamburg port, the Großer and Kleiner Grasbrook and the eastern Steinwerder. Since the end of the 20th century, the city has been faced with the task of finding conversions for these areas. A modernization of the port facilities is only possible for those to the west of the Old Elbe Tunnel, as its upper edge, at twelve meters below the mean high water, does not meet today's ship depths.

In 1997, the then Mayor of Hamburg, Henning Voscherau, published plans for the redevelopment of the area near the city center, the Großer Grasbrook. As so-called HafenCity , an entire district with mixed commercial, office and residential developments as well as a selected structural and leisure offer is to be built. This planning has been implemented on the 155 hectare area since 2004, with projects that are outstanding in terms of architecture, construction or content, such as the Elbphilharmonie , the Cruise Center , the HafenCity University or the Überseequartier .

See also

- History of Hamburg

- List of Hamburg port facilities

- Shipyards in Hamburg

- Chronology of hydraulic engineering on the Hamburg Lower Elbe

- Hamburg Harbor Museum

literature

- Karl Heinrich Altstaedt: Schauerlüd, Schutenschupser and Kaitorten: Workers in the Port of Hamburg , 2011, books.google

- Jörgen Bracker : Hamburg. From the beginning to the present. Turning marks in a city's history. Hamburg 1988, ISBN 3-8225-0043-7 .

- Christina Deggim: Harbor Life in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times - Sea Trade and Working Regulations in Hamburg and Copenhagen from the 13th to the 17th Century. Conventverlag, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-934613-76-4 .

- Herbert Diercks : The Port of Hamburg under National Socialism. Economy, Forced Labor, and Resistance. published by the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial. Hamburg 2008 (The booklet is based on the exhibition The Port of Hamburg under National Socialism in the Hamburg City Hall from January 25 to February 17, 2008 and other dates.)

- Carl von Düring: The entire port operations of the Port of Hamburg (1936, Reprint 2012, 96 pages) books.google , reading excerpt, p. 7–17 (PDF) Dr. Carl Freiherr von Düring was chairman of the port operations association and leader of the entire port operations .

- Heinrich Flügel (1914, dissertation): The German world ports of Hamburg and Bremen . 420 pages (Reprint 2012, ISBN 978-3-95427-097-2 )

- Michael Grüttner : The world of work at the water's edge. Social history of Hamburg port workers 1886–1914 (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht), Göttingen 1984.

- Arnold Kludas , Dieter Maass, Susanne Sabisch: Port of Hamburg. The history of the Hamburg free port from the beginning to the present. Hamburg 1988, ISBN 3-8225-0089-5 .

- Jorun Poettering: Commerce, Nation and Religion. Merchants between Hamburg and Portugal in the 17th century. Göttingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-525-31022-9 .

- Johannes Schupp (1908, dissertation): The social conditions in the port of Hamburg . Verlag Lüdtke & Martens ( archive.org - 98 pages)

- Hans Jürgen Teuteberg : The emergence of the modern Hamburg port (1866-1896) . (PDF) In: Tradition, 17th vol. (1972), pp. 257–291.

- Klaus Weinhauer : Everyday life and labor dispute in the port of Hamburg. Social history of the Hamburg port workers 1914–1933 . Schöningh, Paderborn 1994, ISBN 3-506-77489-1 digitized