Crimean War

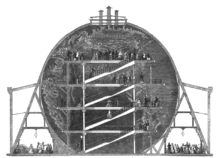

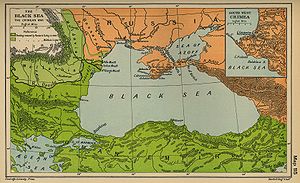

Most important scenes of the Crimean War: Crimea, the coast of southern Russia , the north coast of Turkey and the Danube principalities

| date | 1853 to 1856 |

|---|---|

| place | Crimea , Balkans , Black Sea , Baltic Sea , Pacific |

| exit | Allied victory |

| Peace agreement | Paris Peace |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

Olteniţa - Akhaltsikhe - Başgedikler - Sinope - Cetate - Silistra - Nigojeti - Tscholok - Odessa - Kurekdere - Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky - Alma - Sevastopol - Bomarsund - Balaklava - Inkerman - Yevpatoria - Taganrog - Çorğun - Kars - Tschernaja - Malakoff - Kinburn- Third Peace of Paris

The Crimean War (also East war , Russian Восточная война, Крымская война Vostochnaya wojna, Krymskaja wojna or 9th Turkish-Russian War ) was a 1853 permanent and 1856 military conflict between Russia on the one hand and the Ottoman Empire and its allies France , Britain and since 1855 also Sardinia-Piedmont on the other hand. It began as the ninth Russo-Turkish War , in which the Western European powers intervened to prevent Russia from expanding at the expense of the weakened Ottoman Empire.

importance

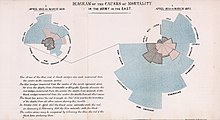

The Crimean War is seen as the first “modern” and the first “industrial” war. During the siege of Sevastopol came the first trench warfare of the modern and the first grave war on a grand scale. It was more of a war of machines, logistics and industrial potential and less of general art. Before Sevastopol, those involved fought the first material battle in history. As a result of new technical developments, this military conflict was particularly costly, with most of the victims dying from hunger, thirst, epidemics, diseases and improper wound treatment on the one hand, and from mechanization and modernized weapon systems on the other. The Crimean War is closely linked to the incipient reform of the British hospital system and, in this context, to the world-famous nurse Florence Nightingale , due to the poor supply that became apparent at the time . Since telegraphy made it possible for the first time to transmit messages from remote theaters of war to the capitals of Western Europe within a few hours, and because the new visual media such as the newly emerged printing technology (lithography) and press illustrations made it possible to report on the events of the war in real time, the Crimean War applies as the hour of birth of modern war reporting . Photography, which was still in its infancy, was a useful source of information for the military and the wealthy for the first time. In spite of the new telegraphy technology, most of the communications continued to be in paper form.

War was not waged with huge armies and national enthusiasm, as had become customary after the French Revolution, but in the style of the Ancien Régime , with limited military expeditions of manageable dimensions, comparable to a cabinet war of the 18th century, albeit that Characteristic of non-participation of the public, since it was the first European “media war”, does not apply and elements of a national war were present. Soldiers fought without uniforms, and so there was still a colorful war that continued the image of war as an adventure. Battles continued to be overlooked and directed by the commanders' hills. The war had not yet lost the character of the play with prominent actors, which was so important for battle painting. There was no national enthusiasm and mass participation, as became common for modern warfare after the French Revolution. At the same time, the educated classes of the tsarist empire felt their side's defeat as a “national disgrace” and the Allied populations felt a strong identification of fighting troops and homeland. With the conquest of Sevastopol in September 1855, the war was in fact decided. All the powers involved, with the exception of the Kingdom of Sardinia, had used only small parts of their military power directly.

The war was of paramount importance in Europe between the Napoleonic Wars (until 1815) and the First World War (from 1914) and significantly disrupted the European equilibrium of the pentarchy , although on the surface it confirmed the status quo . Russia was largely isolated, while France could clearly see itself again as a great power on an equal footing with the others. The diplomacy of the Habsburg monarchy, which was deliberately opaque, but securing its livelihood, led to political isolation and lastingly damaged its good relations with Russia.

All the names found for this war are - if you look closely - too short for him. The western term “Crimean War” - based on its main theater of war on the Crimean peninsula - does not do justice to its global dimensions and its great importance for Europe, Russia and the Orient. The name "Oriental War" used in Russia connects it at least with the Oriental question, which can be localized in the areas of the Balkans to Jerusalem and Constantinople to the Caucasus. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire created international problems. The title as another "Turkish-Russian War", as found in many Turkish sources, does not take into account the massive involvement of the West. The Crimean War was something of a preliminary form of the First World War and it is likely that a similar conflagration would have occurred through a more active participation by Prussia and Austria. There were comparable pre-forms in weapon technology, industrialization and motivations in this war. Global dimensions of the struggles were also present. These began in the Balkans, shifted to the Caucasus and from there to the other Black Sea regions. When Russia threatened a hostile alliance between Austria and Great Britain and France, the fighting shifted to the Crimea. In addition, there was a war in the Baltic Sea right from the start, right up to plans by the Royal Navy to bomb the capital Saint Petersburg , the White Sea as a war zone, on the coast of which the Solovetsky Monastery was shelled and the Pacific coast of Siberia as another scene. In contrast to the five main parties, Austria and Prussia, countries that remained neutral, such as Sweden, Greece, Spain, Portugal and the German Confederation, were more or less indirectly involved in the war.

The type of warfare already took on a partially industrialized form and for the first time comprehensively exploited all social resources. HE shells, steamships, underwater mines with remote ignition, rifles with rifled barrel were used. The British built a railway for purely military purposes. The fighting in the Caucasus, the Balkans and the Crimea was also accompanied by organized ethnic persecution and massacres of civilians. Against this background, there is talk of a first “ total war ”. Despite all the mass deaths, this war was no more bloody than others before it, but in its course it for the first time tore all branches of human and state existence to itself, through ever more systematic and total use of all intellectual, economic and technical means of power.

background

Between the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1853, Europe experienced a unique period of peace in which the great powers Russia, Great Britain, France, Austria and Prussia avoided waging war against each other. Rather, they formed an association described as a “ European concert of powers ”.

According to the historian Jürgen Osterhammel , the Crimean War emerged less determinedly than later the Sardinian War or the German Wars of Unification after a chain of diplomatic errors, misunderstandings and hostility. In the most varied of systems, both in autocratic Russia and in the more liberal Great Britain, war promoters were at work, for example in Russia a “poorly informed” tsar and in France “a political gambler ”. However, there was also “a logic of geopolitical and economic interests”. In essence, it was a conflict between the two powers Great Britain and Russia, which had interests in Asia, and it revealed the military weaknesses of both. "For the first time since 1815, war was accepted to the point that it actually happened."

Several independence movements, including in Egypt under Muhammad Ali Pasha , weakened the Ottoman Empire in the 1830s. In 1833, Egyptian troops under Ali Pasha had conquered Syria and threatened Constantinople. Thereupon the Russian tsar formed an alliance with the Turkish sultan and dispatched troops, which alarmed Great Britain, since from their point of view this represented an attempt by the land power Russia to gain strategic military access to the Mediterranean.

The Egyptian troops had to withdraw to Syria. The Middle East problem became acute again in 1839 when the Sultan made his claims in Syria and attacked the Egyptian forces there. France sided with Egypt, while the then British Foreign Minister Palmerston arranged for Austria, Russia and Prussia to intervene in favor of the Sultan. The Orient Crisis occurred , in which European powers interfered in the conflict between the Ottoman Empire and Egypt, which formally belonged to the Ottoman Empire, from 1839 to 1841. The Egyptian military leader gave up Syria, which limited France's ambitions in the Orient. With the Dardanelles Treaty of 1841, the Ottoman Empire undertook to close the straits to warships during peacetime. This reduced the influence of Russia, which had previously threatened British access from the Middle East to India.

Protectorate of the tsar over the Holy Land

A major cause of the war were religious conflicts over the use of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem . Until then, adherents of the various Christian denominations shared the claim to ownership of this site, which was considered sacred to Christianity . From the beginning of the 19th century, however, the Greek Orthodox Christians had expanded their position in the use of the church. The Catholics tried now, with the support of Napoléon III, who was proclaimed Emperor of France in December 1852 . to change this situation.

The decisive incident was the removal of the silver star in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem in 1847 . The High Porte under Sultan Abdülmecid I replaced the star in 1852, but could not prevent the Russian Tsar Nicholas I from taking over the protectorate of all Christians in the Holy Land (the Palestine region ) to protect the Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire. demanded, so the sole patronage. The Ottoman sultan as the political representative of Islam and the French emperor - representing the interests of Catholicism - did not want to agree to Russian hegemony over the Christians in Palestine.

France was very determined to oppose further Russian expansion. However, only superficially the holy places offered conflict with the government in St. Petersburg. Jerusalem and other cities in the Holy Land were predominantly inhabited by Muslims and Jews , who at that time still coexisted peacefully. There, of all places, the Christian minorities were at odds. Especially at Easter there were violent arguments between the Greek Orthodox monks and the Catholic Franciscans . Even then, the term “monk bickering” was used for it. It was about things like who was allowed to repair the Church of the Holy Sepulcher or who was allowed to keep the key to the Church of the Nativity and the grotto. Russia stood behind the claims of the Orthodox, while France and Napoleon III distinguished themselves as advocates for the Catholics. tried to continue to rely on his support from the Catholics in his own country and his weak regime . The mobilization of society for the Crimean War was intended to help the French revolutionary supporters to reconcile themselves with their Catholic despisers, who are equally represented in the population.

For Britain's elites, apart from pretended religious motivation, there was no doubt that a war against the tsar was generally a war for English values of fair play and the values of the free world, such as separation of powers and free trade.

In the later course of the war there was a widespread opinion in the public perception that the two Christian nations France and Great Britain, allegedly out of concern for the holy places, had allied themselves with a Muslim state against Christian Russia.

The Russia connoisseur Orlando Figes calls this war the “last crusade” in connection with the long series of military conflicts of this kind, which certainly have parallels to this one. All crusades by the “ Christian West ” were without exception strategically, religiously and economically motivated wars between 1095/99 and the 13th century. In a narrower sense, however, only the Orient Crusades carried out at this time are considered to be those directed against the Muslim states in the Middle East . Even after the First Crusade , the term “crusade” was expanded to include other military conflicts whose goal was not the Holy Land , and until modern times it was used, among other things, for very different military actions.

The "sick man on the Bosporus"

One of the real and deeper causes of the war, however, was the internal disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, which many media of the time described as the " Sick Man on the Bosporus ". Russia saw this as an opportunity to expand its power in Europe and, in particular, to gain access to the Mediterranean and the Balkans . Ottoman rule in the Balkans appeared to be in jeopardy, and Russia pushed for control of the important straits of the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles . The Russian tsar had previously tried in vain to win the governments of Austria and Great Britain over to the division of the Ottoman Empire. Great Britain and France resisted this Russian expansion . They did not want the key positions to fall into Russian hands and supported the Ottomans in order to maintain the status quo and thus secure their own power in south-eastern Europe on the Ottoman borders. In the so-called Oriental question about the continued existence of the empire, they were of the opinion that the Ottoman Empire, which at that time was still vast and stretched from the Balkans to the foot of the Arabian Peninsula, from Mesopotamia in the east to Tunisia in the west , in principle must be preserved. Its collapse would have created a power vacuum. For Great Britain, the most important trading partner of the Ottoman Empire at the time, it was also a matter of securing the routes to India and preventing Russian hegemony in Asia ( The Great Game ). Economically, the Ottoman Empire sank to the level of a semi-colonial raw material supplier and became increasingly dependent on the economically highly developed countries of Western Europe. British exports to Turkey had increased eightfold in 1825-1852. In the meantime the great empire was the main importer of English industrial products. The tsarist empire, on the other hand, had become the most dangerous opponent of the Ottoman empire.

An overthrow of the European order created at the Congress of Vienna - which was perceived as disadvantageous - as a result of a congress that ended the foreseeable war was Napoleon III. War and peace goal. A favorable moment for Napoleon III to set the lever on the construction of this order of 1815. in the explosive situation of 1853 in the Orient. His later policy in the Crimean War, and especially his attitude after the fall of Sevastopol, were closely related to the overriding aspect of his grand plan. The oriental crisis and the fate of the Ottoman Empire interested him only in the context of their usefulness in realizing his idea of re-establishing France as a major European power. However, it was not the only attempt to implement his ideas and the Crimean War was only a desirable, but not a necessary war for the realization. He hesitated for a long time, considering the risks and victims of war.

In the 19th century, the oriental question found its way onto an international stage. The armed conflict between the strengthened Russian and the weakened Ottoman empire did not automatically mean the entry of the war by the other major European powers, although additional pressure arose to this end due to the different degrees of nationalism emerging everywhere. In the wake of the French Revolution, national sentiments also arose among the local peoples of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans, and this became a factor of its own in the complex of the question. The worsening of the question alone did not cause the Crimean War, because the Russo-Turkish war of 1827/28 and that of 1877 did not expand into a European war like this one. The role of the element of public opinion here suggests other contributory causes.

Ideologies and enemy images

Russia's motive for smashing the Ottoman Empire was not based solely on geopolitical interests. It was also based on Pan-Slavism , which had spread in parts of Russian society since the beginning of the 19th century, and the desire to liberate the Orthodox Slavic peoples of the Balkans from Ottoman rule. Reports of bloody crackdowns on the Balkan Slavs' freedom struggles that flared up regularly outraged the Russian public and caused calls for intervention. Russia saw itself as the protective power of the Orthodox Christians and claimed for itself to represent both the Orthodox living in its own country and those of the Ottoman Empire. At the same time, it was about preventing an impending Islamic and nationalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire.

In Great Britain, France and other countries in Western Europe, on the other hand, there were Russophobic and Turkophile ideas that sometimes gripped larger sections of the population. Russia was hated by many as a European gendarme who not only oppressed the peoples in Russia, but also fought freedom movements in the rest of Europe. They considered the suppression of the Polish uprising in 1830/1831 and the invasion of Hungary in 1849 as examples .

Some intellectuals, on the other hand, were of the opinion - with regard to the Ottoman Empire - that it could definitely reform itself in a liberal sense. The many ideological resentments in the West gave rise to aggression, but during this period these were not directed against Islam, but against Russian Orthodoxy. Clericals and newspaper makers in England feared its expansion into the Balkans more than the religious supremacy of the Muslims in this region, which had been opposed for centuries. Anglican clerics in Britain, which at that time liked to think of himself as something of the moral spearhead of mankind, did not shy away from their pulpits Islam as a beneficent supremacy for the oriental Christianity to praise his alleged tolerance in contrast to the orthodox despotism to praise. Liberal politicians such as Anthony Cooper , the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, for example, assessed the Tanzimat reforms , which were controversial in the Ottoman Empire, as Turkey's dawning into an age of progress and tolerance. The massacre of Chios (1822) carried out by the Ottoman side, for example, which Eugène Delacroix depicted in a painting, has been faded out. At that time, hundreds of apostates were still executed annually in the Ottoman Empire under Islamic law. The most modern and technologically advanced empire in the world at the time, Great Britain, went to war against its former Christian ally Russia, alongside a Muslim empire on European soil.

Menshikov's mission

The trigger for the war was the appearance of Prince Menshikov at the end of February and March 1853. The Tsar had sent the military to Constantinople to bring a number of demands to the Ottoman Empire. Thus the continuation of the privilege of Orthodox Christians in the holy places of Christianity and the repair of the dome over the Christ tomb were demanded without the participation of the Catholics. The Sultan was initially ready to meet some of these demands. But Menshikov had brought a second, very far-reaching demand: the Ottoman Empire should recognize Russia's patronage over the Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire, who made up a third of its population, by means of a treaty. Menshikov's appearance broke off the negotiations. It did not help him to extend his ultimatum several times by a few days: the Sultan, supported by the British ambassador, rejected the Russian demands. This gave Russia a pretext for the military escalation of the conflict. Menshikov left on May 21, 1853 amid great scandal. Russia broke off diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire.

Just three weeks later, France and Great Britain sent a clear signal: their Mediterranean fleets anchored in Besika Bay near the Dardanelles entrance. Charles John Napier was appointed Commander in Chief of the British Fleet in the Baltic Sea. He ran his warships into the Baltic Sea on March 11, 1854, 17 days before the British declaration of war, in order to block Russian ports. Since the Russian fleet did not take part in combat, Russian shipyards and ports in Finland were attacked or shot at in the following weeks.

The Russian tsar was then ready to go to war against the Ottoman Empire and its possible allies France and Great Britain. Ivan Fyodorowitsch Paskewitsch , the tsar's most important military advisor, was not sure of Austrian support in such a war. He therefore recommended that the tsar occupy the Danube principalities , if necessary for several years. This and the Russian propaganda would lead to 50,000 Balkan Christians making themselves available as soldiers for the tsar. This would deter the Western powers from intervening and force Austria to be neutral.

The autocrat Nicholas I at the military head of the "steamroller Russia" did not strive for supremacy in Europe by blowing up the strategically important Dardanelle bar. The tsar felt genuinely committed to the rules and norms of behavior that the “European concert”, embedded in the treaty system of the Congress of Vienna, demanded from its participants. Against his original will he was forced into the later war with France and Great Britain.

course

Russo-Turkish conflict

At the end of June 1853, the Tsar ordered his two armies in Bessarabia to invade the neighboring Principality of Moldova and the Principality of Wallachia . Prince Mikhail Dmitrijewitsch Gorchakov crossed the Prut with 80,000 men and set up his headquarters in Bucharest. The population was told that the Tsar was only interested in a pledge to force the gate to respect religious rights.

The Ottoman Empire - again encouraged by the British - declared war on Russia on October 16, 1853, after several diplomatic attempts to resolve the conflict had failed. The Ottoman general Omar Pascha then advanced against the Imperial Russian Army on the Danube and won the first victory in the Battle of Oltenița on November 4th. At this point in time, the Russian campaign can already be viewed as a failure, as more than two thirds of the tsarist soldiers died within a few weeks from epidemics, epidemics and wounds and the losses could not be compensated for later.

On November 30 of the same year, the Russian Black Sea Fleet attacked the Ottoman port of Sinope with six ships of the line , two frigates and three steamers under Vice Admiral Nakhimov . With HE shells fired from bomb cannons , the Russians set fire to all the ships of the Ottoman Vice Admiral Osman Pascha with 4,000 marines on board in the sea battle near Sinope . Of the seven Ottoman frigates and five corvettes, only one fleeing to Constantinople survived the battle. A British-French fleet then entered the Black Sea a few weeks later. Nikolaus now made compromise proposals. England and France then did not enter into real negotiations.

Napoleon III made a final attempt at mediation on January 29, 1854, with a letter to the Tsar in his own hand. Nicholas I rejected it, however, with a provocative reference to the defeat of Napoléon Bonaparte in the Russian campaign in 1812 for France . The mood of the population in France then turned against Russia. On March 12, 1854, France and Great Britain signed a war aid treaty with the Ottoman Empire.

In the long chain of causes of war, the battle of Sinope was the decisive reason for the Western powers to enter the war. The news of the battle, in which 3,000 Turkish sailors were killed by the technically superior Russian HE shells within a few hours, so angry public opinion in Western Europe - especially in Great Britain - against Russia that all attempts to resolve the crisis diplomatically , have been discredited.

France and Great Britain enter the war

On 27./28. In March 1854, France and Great Britain declared war on Russia to prevent Russia from expanding in power. Both countries had already sent their Mediterranean fleets into the entrance to the Dardanelles in June 1853 and into the Black Sea on January 3, 1854 . In April 1854 the Allies landed their expeditionary troops at Gallipoli to prevent a possible Russian advance into Constantinople. On April 22, Allied ships fired at port batteries off Odessa for ten hours , destroyed them and then withdrew. This was of little military importance.

In May it was decided to assemble the French and British troops that had first landed at Constantinople and Gallipoli at Varna . Since this was to be done by sea as much as possible, the transport of troops became an essential task of the Navy, which it retained during the further course of the war. However, the fleet's own resources were insufficient, so that numerous merchant ships had to be chartered. Almost the entire transport between home and depot points in the Orient was done with rented ships. These included many sailing ships that were towed by steamers for reasons of safety and time. The deployment of troops in the Crimea took place on the assumption that the opposing side would not carry out major disruptive actions either on land or on land. As with the armies' first landings on Gallipoli, far from the front, the transfer of troops to the Crimea was largely haphazard and without adequate preparation.

At the express request of Nicholas I, Ivan Paskewitsch took over command of the Danube in April 1854. It began on April 14th with the siege of the strategically important fortress Silistra . Omar Pascha brought up a relief army on June 10 and was again victorious in the fighting off Silistra. Paskevich was injured and again replaced by Gorchakov. The Ottoman army fought much more successfully than in the Russo-Turkish War from 1828 to 1829 , not least because of the reforms by Prussian officers such as Helmuth Karl Bernhard von Moltke . The Russians had to give up the siege of Silistra after 55 days, on June 23rd. Omar Pasha entered Bucharest on August 22nd .

Politics of Austria and Prussia

Austria had been supported by Russia against the rebels in the revolution of 1848/1849 , but on June 3, 1854 threatened Russia to withdraw from the Danube principalities and occupied them after the Russian withdrawal. In October 1854 Austria drew 300,000 Man together on the Russian border, which tied up considerable Russian forces. In this way, Austria played an important role in the Crimean War, even though it did not take an active part in the war, and ultimately angered both parties.

Prussia , on the other hand, was the only major power to remain neutral. The king had promised this. Because of its neutrality, there were even doubts as to whether Prussia was still a great power at all. In public opinion, the influence of the extremely conservative pro-Russian Kreuzzeitung party and the liberal-conservative pro-western weekly newspaper party were balanced. The Prussian ruling class, like that in Austria, was extremely divided in its political stance into a pro-Western and a pro-Russian parliamentary group. King Friedrich Wilhelm IV wavered between the two groups, which prompted the angry tsar to comment: "My dear brother-in-law goes to bed every evening as a Russian and gets up every morning as an Englishman." As early as the spring of 1854, the king dismissed some of her most important sympathizers, generally having the upper hand. The British and the French were considering getting the Prussians on their side. Palmerston presented the following proposals to the cabinet: Prussia should receive the Baltic provinces of the Russian Empire and Austria large parts of the region up to the mouth of the Danube for its participation as a war partner. Sweden should be offered to Finland and the Aland region. The French also insisted on the creation of an independent Polish kingdom.

Ultimately, the rulers in Vienna and Berlin shied away from actively participating in the war, not least because they should have shouldered the brunt of the war. Prussia's neutrality and Austria's only indirect war intervention made a Franco-British campaign against the Russian heartland impossible.

Allied deployment

On May 31, 1854, the first French-British troops landed near Varna (now lying in Bulgaria ). The French contingent consisted of four infantry divisions , 8.5 field batteries and Chasseurs d'Afrique ( hunters on horseback ). In total, the French army consisted of around 30,000 men and 68 artillery pieces.

- French Army ( Saint-Arnaud )

- 1st Division ( Canrobert )

- 2nd Division ( Bosquet )

- 3rd Division ( Prince Napoléon )

- 4th Division ( Forey )

- Cavalry Brigade ( Cassaignolles )

- Cavalry Brigade (D'Allonville)

The British contingent consisted of five infantry and one cavalry division with about 26,000 men and 60 guns.

- British Army ( Fitzroy Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan )

- Cavalry Division ( George Bingham, 3rd Earl of Lucan )

- light cavalry brigade ( James Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan )

- heavy cavalry brigade ( James Yorke Scarlett )

- 1st Infantry Division ( Prince George, 2nd Duke of Cambridge )

- Guard Brigade ( Heinrich Johann Wilhelm Bentinck )

- Highland Brigade ( Colin Campbell )

- 2nd Infantry Division ( George De Lacy Evans )

- 3rd Brigade (Adams)

- 4th Brigade ( John L. Pennefather )

-

3rd Infantry Division ( Richard England )

- 5th Brigade

- 6th Brigade

- 4th Infantry Division ( George Cathcart )

- 7th Brigade

- 8th Brigade (from July 28th Arthur Torrens )

- Light Division ( George Brown )

- 1st Brigade ( William John Codrington )

- 2nd Brigade (Buller)

- Cavalry Division ( George Bingham, 3rd Earl of Lucan )

Shortly after the arrival of the troops in Varna, the Allies suffered their first illnesses. The Allies suffered from poor medical conditions throughout the war. The recommendations of the Commission of the Royal Army Medical Department ( British Medical Services ) previously sent by Director General Andrew Smith to set up sanitary facilities and army hospitals were largely ignored by the army command. As a result, more than 20 percent of British soldiers developed cholera, dysentery and other diarrheal diseases. More than 1,000 British soldiers died before their units became involved in combat.

On June 25th, Lord Raglan instructed the chief of the light cavalry, Lord Cardigan, to march inland to explore the Russian positions. On June 29th, these troops reached Karasu to find that the Russians had begun their retreat behind the Danube and later the Prut . Cardigan then returned to Varna, which he reached on July 11th.

The Russian withdrawal disappointed the Western powers because it made their reason for war obsolete. But Napoléon III. was looking for a military success to meet his great power ambitions. And George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen , Prime Minister of the United Kingdom , expected the war to gain the sympathy of the anti-Russian British public. France and the United Kingdom therefore refused to conclude a ceasefire without a clear victory over Russia. Since a march into the interior of the Russian Empire seemed hopeless, the Allies decided to attack the Russian fortress Sevastopol on the Crimean peninsula .

Although the attack on the Crimea had already been decided, three French divisions marched into Dobruja in the Balkans at the end of July to attack a Russian corps supposedly stationed there . This expedition turned into a debacle. After the French lost 7,000 men to cholera , they returned to Varna. On September 7th, the Allies finally embarked to attack the Crimea.

The Ottoman Empire administered important Greek settlement areas and even its capital, Constantinople, had a large Greek community. When the Russian Empire opened the fighting, the Greeks seemed to have the chance to inherit the Ottoman Empire territorially. King Otto took a strongly pro-Russian course. After the Crimean War began, a British-French fleet quickly occupied the important and largest Greek port of Piraeus . In addition, the capital Athens was occupied and the Greek fleet was confiscated by the Western powers. Otto was thus demonstrated his powerlessness in foreign policy. If he had already lost influence domestically, he was now also shown boundaries in terms of foreign policy. Great Britain saw a kind of protectorate in the Greek Empire. While it was officially independent, the British politically kept it on their leash. Since Otto had taken the Russian side, Britain understood him to be no longer reliable enough. From then on, measures were taken to politically eliminate him altogether.

Fight in the Baltic region

As early as March 11, 1854, the first British warships under Admiral Charles John Napier sailed into the Baltic Sea to block Russian ports (and to forestall a possible Nordic alliance that might block access to the Baltic Sea as part of armed neutrality to protect its trade with Russia would have). Since the Russian fleet did not fight, Russian shipyards and ports in Finland were attacked or shelled in the following weeks .

In August 1854 the Allies attacked the Bomarsund fortress on Åland with around 12,000 landing troops under General Baraguay d'Hilliers . The fort's garrison had hundreds of guns, but the land side defense was weak. In addition, the fortress was not yet completely finished. The Russians under General Bodisco surrendered on August 16; over 2,200 Russians were taken prisoner. After the islands were occupied, the forts of the fortress were blown up. The Russian admiral Pyotr Ivanovich Rikord successfully defended Kronstadt and St. Petersburg. In 1855 the Allies bombed the docks in Suomenlinna near Helsinki for two days .

Karl Marx saw the diplomatic efforts of Russia at the beginning of the Crimean War as a continuation of the Tsarist policy before Alexander I to politically isolate Great Britain through armed neutrality , at least to militarily neutralize the Baltic Sea and thus to protect Saint Petersburg . While Russia was facing an alliance made up of France, Great Britain, Sardinia and the Ottoman Empire, in 1855 Prussia, Sweden and Denmark again declared armed neutrality to protect their trade with Russia and thus in fact adopted a benevolent stance towards Russia. They did not prevent British warships from entering the Baltic Sea and shelling Russian ports.

Fight in the Far East

On August 18, 1854, a British-French ship formation consisting of three frigates , two corvettes and a steamship launched an attack on the Russian city of Petropavlovsk on Kamchatka . However, the city had been fortified in previous years thanks to the foresight of the Far East Governor Nikolai Muravyov-Amursky . The Russians had only a small garrison of several hundred men and 67 cannons. They faced numerically superior Allied landing forces and 218 ship cannons. After long bombardment, around 600 soldiers landed south of the city, but after heavy fighting they were repulsed by 230 defenders and forced to retreat. On August 24, another 970 allies landed east of the city, but were also unable to prevail against 360 Russians. After that, the ships left Russian waters. The losses of the Russians were about 100 men, those of the British and French were about five times as much.

War in the Crimea

Landing in the Crimea

On September 12, 1854, the allied British and French reached the Bay of Yevpatoria north of Sevastopol in the Crimea. From 14th to 19th September they landed their troops and 50,000 British, French and Ottoman soldiers disembarked in the Bay of Eupatoria . When the Allied fleet arrived, it began to rain and soon it was pouring down. As an accompanying and sole journalist with the troops, posted by The Times newspaper , William Howard Russell wrote : "Seldom or never did 27,000 English find themselves in a more dire situation." The British military leadership had not brought tents, blankets, and land for the troops The soldiers' coats were soaked, and most of the men slept in puddles or in streams. The French troops, however, were well armed. He noticed, for example, hospitals , bread and biscuit bakeries, covered wagon trains for the transport of supplies and baggage. "Our great naval state was represented by a single steamer owned by a private company." Such accusatory tone was to be heard often in The Times in the months that followed, with far worse accounts. Russell's reporting brought the glorious British Empire to the public and the assessment of the Crimean War and its sometimes catastrophic circumstances were generally decisively shaped by him. Since then he has been considered the first modern war correspondent.

Battle of the Alma

On September 19, the Allies marched inland, where they were expected on the Alma River by the Russians under Prince Menshikov, who had meanwhile become commander in chief of the Russian troops. Menshikov had taken up a well-developed position. After difficulties coordinating the Allied attack between Commander-in-Chief Marshal Arnaud and Lord Raglan, the Allies were able to achieve their first victory in the Battle of the Alma on September 20. The war correspondent Thomas Chenery of The Times reported after the Battle of the troubling poor sanitary conditions in the British military hospital in Scutari . The performance of the medical service quickly collapsed due to the mass of sick and injured soldiers. Unlike the French troops, there were no stretchers or wagons to transport the wounded from the battlefield. Wounded and sick people who reached the disembarkation port waited here for days or weeks for ships to take them to the military hospital set up in Scutari. This transfer took between 2 and 7 days, depending on the type of ship and weather conditions. Survivors were again faced with a poorly organized transport to the central military hospital on a hill above the port. The Selimiye barracks was built at the beginning of the century and made available to the British as a central military hospital. But it was unsuitable simply because of the lack of water supply. Press reports on these conditions had an enormous effect in England and revealed that not only the cabinet in London and the local plumbing, but also the British army in general were insufficiently prepared for the Crimean War. The care of the sick and injured was probably no worse than during the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, the last major battle in which the British Army was involved. For the first time, however, there were newspaper reporters who quickly informed the British public of the events. Drastic reports by Times correspondents Russell and Chenery shocked British newspaper readers. Chenery asked why the French army was able to organize care for its wounded and sick with the help of nuns, while the British army was unable to provide such good care.

On October 9th, the Allied forces began to encircle Sevastopol . The Russian Black Sea Fleet had sunk in the city's port, preventing a sea-supported attack by the Allies. The fortifications were oriented mainly to the north on the seaside. For this reason the Allies decided to besiege Sevastopol from the south, but never succeeded in completely enclosing the city. The northern flank beyond the Chernaya Bay ( Great Bay ) was not used for the attrition strategy. Through this corridor, the besieged were able to supply themselves with essentials via ship bridges and transport ships. A railway line from the center of Russia to the south did not yet exist, so the supply of Sevastopol became increasingly inadequate.

The Baltic German engineer officer and later Russian general Eduard Totleben had a system of field entrenchments, battery positions and trenches built at short notice, which enabled the fortress to be defended for almost a year.

The siege was marked by catastrophic medical conditions among the Allies. Shortly after the siege began, the French commander-in-chief Saint-Arnaud fell ill with cholera, whereupon he had to surrender his post to General Canrobert . He died three days later on September 29, 1854 on board the Bertholet that was to bring him back to France. This should not remain an isolated case even among senior officers, because the causes of the bacterial infections could not be eliminated. Lord Raglan succumbed to dysentery in June 1855, and the commander of the French fleet Armand Joseph Bruat died of cholera in November of the same year .

Battle of Balaklava

An attempt by the Russians to end the siege led to the Battle of Balaklava on October 25, 1854. During the siege of Sevastopol, the British had established their base in the port city of Balaklava . The Russians had brought in a relief army from Bessarabia and assembled about 8 kilometers away with 25,000 men and 78 cannons under their commander, Count Liprandi . Liprandi occupied the heights and the way to the port seemed clear. However, the Russians hesitated, so Lord Raglan had time to bring his troops up.

After the successful deployment of the heavy cavalry brigade, the light brigade (English Charge of the Light Brigade ) went to death . The debacle would later become a myth of British history. The British Light Brigade's attack on a valley - which was trapped on three sides by Russian artillery - became tragically famous for its heavy casualties and confusion in the transmission of orders. In this fatal attack, which is a central event of the Crimean War in British literature to this day, 156 men of the 673-strong cavalry brigade died from Russian gunfire within 20 minutes and 122 were wounded. However, this battle did not lead to the lifting of the siege.

Battle of Inkerman

The day after the Battle of Balaklava, the Russians attacked the position of the British 2nd Division at Inkerman , but were driven back by heavy artillery fire. The Russians lost 270 men, the British 100. The fighting went down in history as Little Inkerman because a few days later a major battle was to be fought at the same place.

On November 5, 1854, the trapped Russians attempted a sortie against British troops, which led to the Battle of Inkerman . The Russians advanced in three divisions. While General Gorchakov was supposed to bind the French with 22,000 men, General Sojmonow and General Pavlov attacked the British with a total of 35,000 men. The Russians tried to flank the British by occupying the hills at the northern end of the British position. For about three hours, around 8,000 British defended their position against around 30,000 Russians in bitter fighting. Then French Zouaves and Foreign Legionaries attacked the Russians again in the flank and forced them to retreat.

Siege of Sevastopol

When the fortress was built, an attack from the land side was not expected, so the fortifications of Sevastopol were much more developed on the sea side. After the Allies had defeated the Russian field army on the Crimean peninsula on September 20 in an extremely disorderly battle on the Alma, it would have been entirely possible to take Sevastopol in a single stroke from the movement . The Russian side had also positioned their rather small contingents of soldiers there for coastal defense. Even so, the British and French generals decided to besiege the fortress and city according to the classical rules. As a result, Totleben had a system of field entrenchments, battery positions and trenches that was difficult to detect for the attackers and, as it later turned out, an efficient system, which also enabled flexible defense, to be built at an enormous pace in front of the fortress. Admiral Menshikov ordered the Black Sea Fleet to be disarmed and made their marines and cannons available. The Allies, for their part, dug entrenchments and slowly drove their trenches towards the fortress. The British obtained supplies from the port of Balaklava. At the rear, threatened by attacks by the Russian Crimean Army, they were forced to build fortifications there too. They waged a positional war on two sides. From October the warring parties fired at the enemy positions with previously unknown use of ammunition.

The ships of the Allied fleet had no safe anchorage either in the port of Balaklava they used, or in Kamiesch Bay . A large number of transport ships, heavily loaded with food, horse fodder and storage needs, received orders on November 14, 1854, in front of the port of Balaklava - on an unsuitable rocky seabed 35-40 fathoms deep (about 64 to 73 meters) and from Surrounded by 1200 foot (about 365 meters) high rocks - anchor. This happened despite the fact that it was known that violent storms raged there at this time of the year. A later investigation by Urbain Le Verrier into the upcoming November storm showed that a storm field had spread across Europe and that the then new telegraph could have been used to predict the storm for the Crimea in good time. At that time there was no daily published weather forecast. In the hurricane, numerous ships with many crews went down or crashed on cliffs. Five English and two Turkish warships sank at the mouths of the Katscha and Belbek rivers , no fewer than eleven in Balaklawa, and the French lost the ship of the line " Henry IV " at Eupatoria .

There was a shortage of food and animal feed in the Balaklava camp. While order still prevailed under the war and transport navy in Kamiesch Bay, the French disembarkation point, confusion and arbitrariness spread in the British supply port of Balaklava. The November hurricane showed the poor organization of the Balaklava army camp. The torrential rain had turned the whole area from Balaklava to the front into a swamp and devastated it. Of all the tents, which were already extremely poorly constructed, only three remained in the whole camp. The hospitals were also housed in tents. Around noon there was a snowstorm. Many soldiers perished in the cold and wet by the next morning. In the middle of the night, during all the horrors of nature, a violent cannonade began on the upstream front from the batteries of the Sevastopol fortress. On the night of November 28th, cholera broke out. As early as the beginning of December, an average of 80 to 90 soldiers per day died in the English camp. Scurvy and fever epidemics also raged.

On April 9, 1855, the city was bombed particularly intensely. British chief engineer John Fox Burgoyne saw the center of the Russian position in Fort Malakov and concentrated the Allied fire there. In May 1855 there were 35,000 British and 100,000 French in the Crimea. At the end of May, 14,000 Italians from the Kingdom of Sardinia also arrived. In addition, tens of thousands of Ottoman soldiers were involved in varying numbers in the Crimea. The Sardinian expeditionary force was commanded by Alfonso La Marmora . Sardinia had signed a military convention with the two western powers in Turin on January 26, 1855. It sent 15,000 soldiers to the Crimea to support Great Britain. The goal of Prime Minister Camillo Cavour was to promote the Italian unification movement and to fight Russia (and with it the Holy Alliance ). As a result, the map of Europe should be redrawn in a liberal-national sense. It was also about showing that Sardinia could be more valuable to the Western powers than Austria. These in turn avoided making official promises to the Italian cause, since Austria should at least be kept neutral. France even signed a secret agreement with Austria on December 22nd that the status quo in Italy should be maintained for the duration of an alliance against Russia.

The Russian commander-in-chief Menshikov was replaced by Prince Michael Gorchakov, who had already led the attack on the Danube principalities and Silistra in 1853. In the field camp near Sevastopol, great importance was attached to the capture of the port city of Kerch and the rulership of the Sea of Azov , because the Russian army in the Crimea obtained a large part of its food from there. That is why preparations began at the end of April. At the beginning of May the Allies undertook this expedition to Kerch in the south-east of the Crimea. The British Highland Brigade , the Rifle Brigade , the Royal Marines and 8,500 French soldiers were embarked under the command of Sir George Brown but returned without attacking the city. The reason for this was a telegraphic order from the French emperor to collect the reserves from Constantinople. The French ships were needed for this. The relationship between the Allies had suffered when the expedition was broken off. Canrobert, since he could not achieve any decisive successes despite all his efforts and could not come to an understanding with the British, resigned command on May 16, 1855 to make way for General Aimable Pélissier , and took over command of the 1st Corps again. In order to improve relations with the British again, Pélissier agreed to a second expedition to Kerch. The expedition started on May 24th with 60 ships, 7,000 French, 5,000 Turkish and 3,000 British soldiers. This destroyed the Kerch arsenal and several Russian ports on the Kerch Strait . Kerch was occupied after the slight resistance had been put down. The Allies also seized the Jenikal fortress , which lies on a promontory north of the city, and thus gained entry into the Sea of Azov. In the days that followed, the Allied light ships entered these waters. In the individual Russian supply points such as Berdjansk , Mariupol , Taganrog landed and stored supplies were partly taken over and partly destroyed. From then on, Kerch remained permanently occupied by the Allies for the duration of the war. As a result of the appearance of the Alliance's fleet, the Russians also cleared the last two points that they had previously held on the Caucasian coast: Anapa and Sudschukkale. This success was easily achieved, but of great importance. The Russian side found this defeat very painful.

On June 28, 1855, Lord Raglan died of dysentery , his successor was Sir James Simpson and, after his resignation on November 11, William John Codrington . On July 12, Admiral Nakhimov, who had been fatally wounded by a sniper and had been in charge of the defense of the city and its port , died on July 12th .

The Allied fleets ruled the Black Sea, sank transport ships and shot at military objects such as Kinburn Fortress as well as civil objects on the coast. When the ship formation appeared in front of the fortress on October 14th, it was in poor condition and was taken after a short resistance. For this purpose, 4,000 soldiers of the Anglo-French troops were landed on the Kinburn Peninsula on the 15th . These first cut off the fortress on the land side. After a brief resistance, the fort's garrison surrendered on October 17, 1855. The attack on the fortification posed no particular difficulty in terms of the means of defense available to the defenders. This was the first time in history that armored floating batteries were used brought into use. The French fleet had recently been reinforced by three such ships: Lave , Tonnante and Dévastation. The first appearances of an armor system - which was consistently equipped with cast-iron plates - were used on these vehicles. These protected against projectiles of the normal caliber of the time. High hopes were placed in the batteries, especially for the option of an attack on the Russian fortifications of Sweaborg and Kronstadt on the Baltic coast, which so far had nothing to be worn and which were to be fired on again next spring. To enable the floating batteries to pass, icebreakers had to be used before they were deployed in the Dnepr-Bug-Liman . When the fort was bombarded, the armored batteries developed by France showed that ships with iron armor were able to withstand heavy cannon fire. Although the crew members were killed by projectiles that penetrated the gun ports, the iron armor was not penetrated despite many hits.

On August 16, the Russians attempted the only sortie from the siege of Sevastopol under the command of Gorchakov in the Battle of Chernaya . The outnumbered but poorly armed Russian infantry attempted to cross the Chorna River without the support of cavalry or artillery to take the heights beyond. The attempt ended in a bloody massacre in which they suffered casualties between 8,000 and 9,000 soldiers.

The struggle for the Sevastopol fortress reached its climax after almost a year of siege and ended with the storming of the Malakov fort . After three days of bombardment of the city by 775 British and French guns, three French and two British divisions attacked the fortress in several places. After the conquest of Malakov by the French under the command of Generals Patrice de Mac-Mahon and Pierre Bosquet on September 8, 1855, Gorchakov decided - in view of the great losses of his own - to vacate the city of Sevastopol. On the night of September 9th, Russian pioneers blew up most of the fortifications as the fort allowed control of the Black Sea port of Sevastopol. The remaining 40,000 defenders withdrew across Chernaya Bay. The wrestling of the fortress led to the first material battle in history and was characterized by the massive use of weapons and war material. The warring parties threw enormous amounts of troops, military equipment and ammunition into the battle. In the process, an extensive strategic conception of the campaign against Russia was lost. The main goal became to overwhelm the opponent by means of quantitative and qualitative superiority.

The British troops suffered a heavy defeat in the storming of Sevastopol. While the defenders were thrown out of the Malachov bastion by the waves of attack by the French troops, the simultaneously undertaken attack by the English on the Redan - Sevastopol's second important fortress - got stuck in the trenches. The British leadership was dissatisfied and angry about the failure at Redan, especially in view of the militarily glorious French victory. The Queen's statement that she could not bear the thought "that 'the failure on the Redan' should be our last fait d 'Armes" expresses the widespread mood in Britain. This is one of the reasons for the unbroken belligerence there.

Although the Russian army had a total of 1.2 million soldiers, it was never able to concentrate 200,000 soldiers in the Crimea. Because they had to secure the Baltic provinces and the Baltic coast against possible landing operations by the British and French, they stood with troops in rebellious Poland as a precaution, in the south there was danger from Austria and the Caucasian front against the Turks also tied 100,000 soldiers. The Allies won the battle mainly because of their great material superiority. With their bombardments they almost completely destroyed the city of Sevastopol. Generals on both sides ruthlessly sacrificed thousands of their soldiers. As the battle progressed, the French armed forces increasingly bore the brunt of the battle.

The Russian side could not generally count on the support of the native Crimean population. Eighty percent of them were Tatars. When the Allied fleet showed itself off the Crimean coast, large parts of the Russian and Greek population fled and various groups of Tatars rose up against their Russian masters. These formed armed gangs to help the Western powers. On the way to the Isthmus of Perekop , many Russians fleeing the war zone were robbed and killed by these gangs of Tatars. It was alleged, among other things, that seizures would be carried out for a newly established “Turkish government” in Evpatoria .

Although mercenaries like something out of date had gone out of fashion in Europe as a result of the Napoleonic wars, Great Britain in particular immediately began to look for such support in the fight against the Russian mass armies. At the same time, British diplomacy tried to get Prussia, Austria and even Sweden to their side with the help of subsidy payments . However, these countries could not be persuaded to get involved in the war with the gigantic Russian empire for the promised funds. At the same time, the first war reports arrived: the soldiers died en masse in the camps in the Crimea from epidemics and diseases, and the Russians fought doggedly defensively. In contrast to the land powers, England relied on a poorly paid volunteer army, which also had a huge colonial empire to support. As an alternative, the up-and-coming industry offered sufficient job offers and the British press reported extensively on the misery of the sick and wounded on the peninsula, making it difficult to recruit. England was now falling behind on this point in times when it had fought many of its wars with the help of foreign mercenaries. Small states that did not have to fear the effects of diplomatic entanglements with Russia, such as Switzerland, Italy and German principalities, were particularly suitable for recruitment. Immediately the British press and people - driven by national pride - were in an outcry. But more pay for the British soldiers would have led to higher wage demands from the domestic workers. The later legionnaire Rodowicz von Oswiecinski wrote: “One counted with certainty on the Poles, who found the opportunity here to legitimately attack their mortal enemy, the Russian. You counted on the Swiss, who from time immemorial were always men with the syringe when there was a fire somewhere (...) You counted on Italians and Americans, but above all on the German mercenaries. "

Mercenary recruitment was now banned in large parts of Europe. For this reason, among other things, Great Britain limited itself to three foreign legions, one German, one Swiss and one Italian. The formation of the Italian Legion made slow progress. The king of Sardinia had taken over the patronage, hoping to strengthen his own army at English expense. But his subjects showed little interest in being recruited for his political goals.

A recruited contingent of German volunteers on the British side as the German Legion (British-German Legion) was brought to Constantinople, but was no longer used because the fighting had ended. Mercenary recruitment had long been banned in Germany. Nevertheless, the British government appointed Richard von Stutterheim Major General and then entrusted him with the heavily disguised recruitment and organization, as he already had relevant experience. At the end of 1855 the Legion numbered almost 9,000 men and shipments from Great Britain began. Most of them were agricultural workers and artisans, only about half had military training or equivalent experience.

In 1855, Great Britain recruited 3,338 soldiers for the Crimean War without having negotiated a military service agreement with Switzerland. A law had already existed since 1851 which forbade the recruiting of conscripts on the territory of the Confederation and was extended to all Swiss residents in 1853. Even before the British Swiss Legion (BSL) could take action against the Russian troops, the hostilities ceased.

France and Great Britain, encouraged by Adam Jerzy Czartoryski and the political faction within the Polish emigration Hôtel Lambert , encouraged the establishment of a Polish legion. It consisted of 1,500 exiles , prisoners of war and deserters from the tsarist army, was equipped by western powers and was given the cover name "Cossacks of the Sultan". Since the spring of 1855, the question of whether the Western powers would recognize the Legion as a national armed force and whether they would indirectly promote the restoration of a Polish nation-state has been discussed for a very long time. According to statements about the service, a large part was pressed. The Legion did not enter service until the fall.

War in Transcaucasia

The Russians fought more successfully in the Asian theater of war, to which the western allies of the Ottoman Empire had sent only a few military advisers. To defend the Armenian highlands, the Ottomans had concentrated the army corps from Asia Minor , Mesopotamia and part of the Syrian corps in the border area. On November 26, 1853, General Ivan Andronikashvili and 10,000 men routed the Turkish main corps at Suplis . General Bebutov , at the head of a corps of the Caucasian army, won the Battle of Basgedikler over Abdi Pasha on December 1, 1853 , which thwarted the intended Turkish invasion of Russian Armenia . The Turkish commander in Eastern Anatolia, Abdi Pascha, was then deposed and brought before a military tribunal. He was succeeded by Akhmet Pasha. On June 16, 1854 Andronikashvili was again successful against 30,000 Turks at Osurgeti and was able to secure Mingrelia for Russia.

In July 1854, the Russian general Wrangel invaded Turkish Armenia. On July 29th, he defeated a Turkish division at Bajesid . The Turkish commander Zarif Mustafa Pasha attacked the Russians in August with more than 40,000 men. At Kurukdere he came across Prince Bebutow on August 5, 1854. In a five-hour battle, the Russians were able to defeat the Turkish army, but due to their own heavy losses, they were unable to take advantage of the victory and take the important fortress of Kars .

In 1855 General Muravyov was appointed commander in chief of the Caucasian army. He marched into the Ottoman part of Armenia in June 1855 and was greeted with joy by the people there. With 40,000 men he reached Kars in northeastern Anatolia . The 30,000 defenders under the British officer William Fenwick Williams were initially able to repel the attack by the Russians. Thereupon Muravyov led the siege of the fortress from the beginning of June to the end of November 1855. Omar Pasha , who was so successful in the Danube principalities, informed the Allies on July 11th that he would move his troops from the Crimea to Asia Minor. The Allies were against this decision and only approved the plan in September. Omar Pasha's diversionary attack on Kutaisi was eventually foiled by General Bebutov. On November 29, the Ottoman occupation in Kars finally had to capitulate because of the poor supply situation and Muravyov was able to take the city. This success allowed Russia, despite the loss of Sevastopol, to conduct moderate peace negotiations.

Although the warring parties and historiography were certainly unaware of it, after the fall of Kars the Russian army occupied more square miles of enemy territory than, conversely, the naval powers. The conquest of the fortress made the Russian government more inclined to explore peace. This victory seemed to make up for the defeat of Sevastopol, in keeping with the military concept of honor of the time. The fact that the fall of Kars was viewed as a disgrace among the Allies proves this. Queen Victoria described the defeat as "a disgrace to the Allies". The 200,000-strong troops were inactive or only used to build roads remained in the Crimea without having sent a relief army to Kars in Asia Minor. For Napoleon and the French public, the events in this theater of war meant little, as its security had been tacitly left to the British. For the French side, their honor, which had been discredited since the Battle of Waterloo, was restored by the conquest of the Malachov bastion Sevastopol, which dominated the Black Sea region. This removed an important obstacle to peace. Thinking in terms of military honor and shame, which has lost its effectiveness with the change in the image of war, was dominant in the Crimean War - in the forms it was fought until 1855 - for the political calculation of all warring parties and must be taken into account for the assessment of events .

End of war

After the conquest of Sevastopol, Napoléon III wanted. advance inland to step out of the shadow of his uncle Napoléon Bonaparte through the expected success . But his generals advised against such an adventure. The mood in France had also changed because of the length of the campaign and the high losses. Prince Napoléon , the emperor's cousin, had also left the troops, which led to discussions among the French public. Napoleon III in the face of all this, found himself ready to negotiate peace. While the French war preparations, which were much better than the British (also based on the experience of the Russian campaign in 1812 ), ensured that their troops were relatively well supplied in the first winter of the war in 1854/55, the following winter hit them when it fell the fortress of Sevastopol the war had already been decided, all the harder. Although Sevastopol only had to be kept occupied in the second winter of the war, massive losses occurred in the French army camps, which were also huge, due to the damp and disease-promoting accommodation of soldiers in holes in the ground.

In November 1855 the new Russian tsar Alexander II visited the Crimea. There he convinced himself of the need to make peace. In addition, Austria had meanwhile threatened to fully enter the war against the Tsarist empire and Russia had found itself completely in a politically isolated situation. On March 30, 1856, Russia concluded the Third Peace of Paris with its war opponents - the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, France and Sardinia as well as the non-belligerent states Prussia and Austria . It declared the integrity and independence of the Ottoman Empire. Russia had to cede the southeast of Bessarabia : the Budschak , between the Black Sea and the Prut . The strategically important Danube Delta, conquered by Russia in 1812, fell to the Ottoman Empire. The northern part, with the fortress city of Ismail , went to the Principality of Moldova . The lost territories, but not the Danube Delta, were given back to Russia at the Berlin Congress in 1878.

Navigation on the Danube was released, the Commission of the Danube Shore States was established and the Black Sea was declared a neutral area.

Political Consequences

The Crimean War shook the previous equilibrium between the five great powers of Europe ( pentarchy ). The “concert of the powers” no longer worked. Power politicians could now use their chance to establish large nation states (Italy and Germany), even at the risk of international tensions or even wars.

The political system created at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 finally disintegrated as a result of the Crimean War . As a result of Austria's stance in the Crimean War, the solidarity of the “Holy Alliance” - under the three conservative eastern great powers - was dropped. Russia had also played out its role as a major military power and “European gendarme”. Its defeat in Crimea revealed to the world how backward Russia actually was in many areas.

The Crimean War showed contemporaries that a war between great powers could be fought in a “limited” manner. It changed the character of international diplomacy. Generally speaking, its aim was to maintain peace, and alliances were more of a defensive nature: revolutions and hegemony were to be prevented. After the war, on the other hand, the alliances became offensive and diplomacy served as preparation for war. However, the time before the Crimean War should not be portrayed too positively, and with the Berlin Congress (1878) the concert of the powers returned, albeit in a weakened manner.

In England there was a loss of confidence in the British aristocracy due to the carelessness of the noble officers in the Crimean War. In Russia, the tsarist government also lost its reputation, and in France there was euphoria at the glossed over victory and prestige gained through the peace negotiations in Paris . In 1870, in the run-up to the Franco-Prussian War , this resulted in overconfidence.

Russia

The Crimean War ended the strong role that Russia had played in Europe after the coalition wars. Russia's defeat revealed how backward the country was in technology and in its entire social structure. Tsar Alexander II undertook far-reaching reforms in administration, education and in the tsarist army .

For example, there was a lot of catching up to do in industrialization, for example because of the continued serfdom of small farmers, which resulted in a shortage of workers. The most important elements since 1861 were the abolition of serfdom and the renewal of the military organization. Alexander pushed through these reforms against great resistance in the Russian aristocracy. The agriculture of the tsarist empire, which was based on serfdom, could only be maintained if no more than five to six men per thousand of the able-bodied population were drafted into the military, because after their 25 years of service the soldiers gained social freedom. One of the effects was the need to maintain a standing professional army with a high level of peacekeeping, as there was no way to fall back on trained reservists as with a conscript army . Due to the military failures in the Crimean War, the new tsar and his advisors recognized that the serfdom of farm workers was the main obstacle to the creation of an army on par with the western armies. Milyutin , who later became Minister of War and the driving force behind the Russian army reform of the 1870s, had already pointed out this issue very clearly in his memorandum of spring 1856. His plan envisaged the introduction of a conscript army. The age of recruitment was then set at 20, and the mostly rural conscripts were given the opportunity to catch up on primary school education.

Before the Crimean War, the Russian government shrank from the high costs of extensive expansion of the railway network, but modernization has now taken place in the Tsarist empire, for which the later construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway became one of the synonyms. The project of connecting Siberia with European Russia by a rail line dates back to this time.

Before the beginning of the war, the tsarist empire only had a rail network of 1065 kilometers in total. This circumstance led to noticeable logistical problems on the Russian side during the military conflict. The defeat of the tsarist army on its own territory, which was not least a consequence of these logistical problems during the Crimean War, led to a new transport policy. Initially, however, expansion considerations focused on European Russia. But voices were quickly heard calling for a connection to Siberia with the burgeoning Russian rail network on the European side.

When, after the victory of the Allies, at the Paris peace negotiations, the great powers tried to cast the result of these meetings into a treaty under international law, France had the say and had significant influence on peace conditions. Many points were tough for Russia and the Habsburg Monarchy has remained the “traitor” for Alexander II ever since. He claimed that his predecessor and father died just before the end of the war because of grief over Austria's infidelity.

The Crimean War and the reforms that followed were very expensive for Russia. There was also a new feeling of being vulnerable. This contributed to the decision to sell Alaska, which had been Russian until then, to the USA in 1867 .

Ottoman Empire

In the Peace of Paris the territorial independence and inviolability of the Ottoman Empire was guaranteed. In the peace treaty it was formulated that every act and every event that calls the integrity of the Ottoman Empire into question should be seen as a question of European interest . The conquests made were mutually released, but Russia had to admit under the name of "border rectification" that part of Bessarabia with the fortress Ismail was reunited with the Principality of Moldova. The Danube Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia were assured that their old privileges and immunities would be maintained and these were placed under the guarantee of the treaty powers.

Apart from the brief involvement of the Ottomans in the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, it was the first European conflict in which the empire was involved. Through him, the Muslim world of the Ottoman Empire opened up to western technologies and armies. In addition, it pushed its integration into the global capitalist economy. At the same time, however, the war triggered an Islamic defensive stance against the West, which continues to this day.

France

Since the Congress of Vienna in 1815, France was considered the defeated country that had to be guarded by the other great powers so that a new Napoleon would not wreak war on Europe. Soon, however, France again belonged to the great powers and played a role in the pentarchy. Nevertheless, there were diplomatic regressions and during the revolution of 1848 France fell into a certain isolation. Napoleon III also met with suspicion, especially after he made himself emperor in 1852.

However, the Crimean War valued Napoleon III's France. considerably on. It was able to cope with a major conflict, fought alongside Great Britain and the peace negotiations took place in Paris under Napoleon's leadership. That being said, the status quo persisted while France had tried in the past to distinguish itself at Constantinople's expense.

Great Britain

The Crimean War showed that there was significant maladministration in the British military. As a result, the Aberdeen government lost its reputation. In February 1855 she was forced to resign and Palmerston took over the formation of a new cabinet. The future British Prime Minister Disraeli declared the war to be an “Indian war” from a South Asian perspective, as there had previously been (unreal) fears that Russia could endanger British India by expanding south. The relationship between Great Britain and Russia remained tense until the 20th century for reasons of ideology and world power politics.

The war resulted in the formation of a modern national myth in Britain of the "common" soldier defending the nation's honor, instead of the aristocrat of earlier wars. In the middle class, there was a new sense of self-confidence in connection with ideas such as professional ability and the principle of achievement. The middle class recognized themselves in a Florence Nightingale who rose to become a national heroine. The Queen donated the Victoria Cross in 1857 , with which non-officers could be awarded for the first time.

Italy

The Kingdom of Sardinia saw itself upgraded through its participation in the Crimean War. It was able to put the Italian question on the French political agenda with the aim of uniting Italy. In addition to the rapprochement with France, it was important for Sardinia that Austria had been diplomatically weakened. In July 1858 it concluded with Napoléon III. signed a secret treaty in Plombières-les-Bains . In the alliance with France, the unification of Italy under the leadership of Sardinia against Austria after the Sardinian War was finally achieved until 1861 and the Italian nation-state was founded as a constitutional monarchy (see Kingdom of Italy ).

German Confederation

Austria had been the supreme power in the German Confederation since 1815 , and this position was now gradually faltering. Russia was disappointed in Austria, but so were the Western powers, who found themselves inadequately supported. This foreign policy weakened position of Austria was later to prove fatal in the Sardinian War (1859) and then in the German War (1866). Prussia's relationship with Russia, on the other hand, improved.

The effort involved in mobilizing the troops sent to demonstrate their power against Russia brought Austria to the brink of financial ruin. This led to lasting savings in the army. Austria lost the war of 1866 not least because of the savings made earlier. The German Confederation was dissolved and Prussia significantly increased its territory and power. The Crimean War thus paved the way for German unity in 1871 under Prussian leadership and Prussia can thus be seen as the only beneficiary of this war.

Today the accusation, which goes back to contemporaries, can no longer be upheld that Austria wavered back and forth between the ally of the Holy Alliance Russia and the Western powers England and France and thereby caused her later political isolation among the powers themselves. The main members of Austria's policy, which was unwaveringly aimed at the rapid termination of war and peace, were the alliance of protection and defiance with Prussia of April 20, 1854; in the various calls to the German Confederation to participate in the Austrian policy of gradually moving away from Russia and finally to provide troops for any necessary intervention in the war; in mobilizing one's own troops; in the request to Russia of June 3, 1854, to evacuate the occupied Danube principalities; in the subsequent occupation of these principalities by Austrian troops; in the formulation of the Four Points on August 8, 1854, the joint war target program of the two Western powers and Austria (international declaration of protection for the Danube principalities, freedom of navigation on the Danube, revision of the Straits Treaty of 1841, Russia renouncing its protectorate over the Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire) ; in the alliance treaty between Austria and the Western powers of December 2, 1854, which was only apparently entered into as a war alliance; and finally in the Austrian ultimatum to Russia of December 16, 1855 - the non-acceptance of which was expected - which in turn would entail Austria's entry into the war.

Austria did not want to allow any party to dictate its war and peace policy . The Metternich's Austria had played the role of a junior partner in the Holy Alliance. Like his predecessor Schwarzenberg , Count Buol , Minister of Foreign Affairs, was looking for ways to free himself from the pressure of Russian guardianship in European politics. In the course of the Crimean War the opportunity came and was used by him.

The fear of revolution weighed heavier on the leadership of the multiethnic state than the fear of Russia's overwhelming power. In connection with this war, this runs like a red thread through Austrian politics. In the wake of the revolutionary years 1848/49 , for example, the state of siege over Vienna and Prague lasted until September 1853, in the outer regions of the empire, such as Lombardy-Venetia , Galicia and Transylvania , until the middle / end of 1854. The extensive service obligation of Austrian (Hungarian , Polish) deserters from 1848/49 in the Turkish occupation army on the Danube front gave rise to diplomatic presentations at the Sublime Porte in Constantinople, just as the formation of an Anglo-Italian legion in Sardinia prompted corresponding diplomatic steps towards the seat of government in London.