Black scene

The Dark Scene is in the late 1980s from the followers of the Dark Wave and Independent resulting scene . It developed from a youth-cultural community over decades into an age-independent social network , whose great common ground lies in an aesthetic, self-portrayal and individualistic concept. It is regarded as a community that is defined by symbols, media and meeting points within the scene, especially scene-specific events and discos as well as the different trends in the scene's own fashion. The common interests of the scene include music , art and fashion as well as dealing with philosophical , new-religious or society-perceived topics and taboos. In particular, against the background of the individualistic concept, there is a discussion of the topics of death, mortality, sadness, grief and melancholy, clinical psychology and psychopathology .

The scene is neither musically nor fashionably understood as a homogeneous group. It is divided into different currents, some of which are diametrically opposed to one another in terms of their musical and fashionable ideas. The musical preferences of the various fans of the black scene are characterized by an almost unmanageable variety of styles. The term black music is used as a collective term for the entirety of the music received in the scene in social and cultural studies literature .

The color black with all its conceivable symbolic values is named as the lowest common denominator, and thus a central aspect of communalization . It is seen in the scene as an expression of seriousness, darkness and mysticism, but also as a symbol for hopelessness, emptiness, melancholy and as a reference to grief and death.

Content and delimitation

Definition

The black scene is now a milieu made up of parts of different scenes . The scene without a name (as titled by Ecki Stieg ) can also be found in a comparable form outside of the German-speaking countries. In Spain it is called cultura oscura , in the Portuguese-speaking areas of America cultura dark and in Luxembourg Schwaarz Zeen . In the English-speaking world - besides the sporadically used terms dark scene and dark culture - no corresponding designation seems to have established itself; sometimes, as in Italy, for example, the term Gothic is misleading as a generic term for the entire black scene continued from the Gothic scene .

The origin of the term "black scene" is controversial. In 1990 this appeared, for example, in the report Schwarze Szene, Berlin - A Critical Self-Presentation , which was completed in autumn 1989, but was not published until 1990 in the January issue of the Zillo music magazine. According to this report, the Berlin scene at that time was recruited from “Goths, Wavers and New Romantics”. Self-titling as "black" is also mentioned there.

Only a little later the term "black scene" was used in a report on one of the two concerts of The Cure in the GDR ; this appeared in the autumn 1990 edition of the Freiburg wave magazine Glasnost . About two years later, the name appears in the Gothic Press magazine in Bonn , this time in the foreword to an interview with Death in June , on which a journalist from Zillo magazine worked intensively.

After the negative attitude of the subcultures to one another gradually gave way to an opening in many places in the 1990s, the term advanced to a widely used term in numerous music magazines to address a specific target group of readers. The independent magazine Zillo itself was long regarded as one of the most important media in the black scene and was probably able to establish the name. It is unclear, however, whether the motto “from the scene for the scene”, which has adorned the front page of Zillo magazine for the next three years since 1997 , actually applied to the black scene, or whether it meant the independent and alternative culture in their entirety was meant.

In one of the first German-language social-scientific discussions with the scene, Das Charisma des Grabes , Roman Rutkowski advocated the use of the term in 2004, as this term, compared to other partially used terms, is used to name a generic term for all sub-scenes and currents of the black scene. According to Rutkowski, this term is preferred by a large number of followers of the scene. Nym stated in 2010 that the term had already established itself, especially in sociology and youth culture research. The term has also spread in scene media and the press since the 90s, but the misleading title Gothic , which denotes a subcurrent of the scene , is sometimes used.

Occasionally the term is also used for the black metal scene, which, however, has different subcultural origins and musical preferences.

Definition of terms

As early as 2004, the term “ Gothic ” was used several times, especially by outsiders, to mean “Black Scene”. The Gothic subculture, however, is linked to the post-punk and wave movements and thus represents only a fraction of the entire spectrum of the black scene. Against this background, its use as a synonym is controversial and is controversially discussed within the black scene. A clear delimitation is sometimes made difficult by the frequent use of the term “Gothic” in the music press and international differences in the use of the term.

Social structure

In an international comparison, the German scene is often seen as the most important expression of the subculture. Due to its internationally recognized events and the high proportion of music produced in Germany, the German subculture is perceived as outstanding and special, sometimes referred to as 'Urland'.

Contact and exchange mostly take place via concert and discotheque events as well as via internet forums or chats , which can lead to cultural overlaps (“patchwork cultures”), although the original subcultural forms remain independent.

The largest meeting rooms for culture in German-speaking countries are the Wave-Gotik-Treffen in Leipzig with around 20,500 visitors and the M'era Luna Festival in Hildesheim with around 25,000 visitors and the Amphi Festival in Cologne with 16,000 visitors. The magazines Orkus , Sonic Seducer and Gothic with print runs of 40,000 to 60,000 monthly printed copies are considered important media . In addition, local and regional event calendars are common. The Internet is particularly important for the self-organization of the scene. In the early to mid-2000s, the TV music program Onyx.tv presented the weekly moderated music program Schattenreich, tailored to the scene, in cooperation with the magazine Sonic Seducer .

In terms of size, the German black scene was estimated at around 50,000 to 100,000 people in 2004. In 2010 this assessment was confirmed again.

In contrast to many comparable youth cultures , the gender ratio is balanced. The established age structure of the scene shows that it “can hardly be described as a pure youth culture .” A large number of the scene-goers have regular employment and have families of their own. The age range begins at fourteen, but there is no upper age limit to be determined, so that even entire scene families are “not uncommon”.

Scene content

The scene is seen as a heterogeneous collection of different subcultural currents, without being "tied to a style of popular music and the associated thinking, behavior and dress codes". Rutkowski names the style, consisting of fashion and habitus , as the core of the scene. Alexander Nym also underlines this thesis in an interview with the website of the Süddeutsche Zeitung . According to Nym, "music no longer plays the main role." Rather, "black culture extends to every aspect of life", so that other cultural aspects such as "literature, films [or] the way you furnish your home" are shaped by the scene . He describes “black clothing” as “universal commonality” and “lowest common denominator”.

The “scene” is neither musically nor fashionably to be understood as a homogeneous, self-contained group. It is divided into different currents, some of which are diametrically opposed to one another in terms of their musical and fashionable ideas. The musical preferences of the various followers of the black scene are shaped by a “mix of styles that covers the spectrum from avant-garde bruitism to electronic pop music , old music […], ( neo- ) classical and folk to ( punk ) rock , techno and ambient ” . As a collective term for the entirety of this music received in the scene, the term black music is preferred in social and cultural studies literature.

The color black with all its symbolic values is named as the lowest common denominator, and thus as the central aspect of communalisation . Among other things, it is an expression of seriousness, darkness and mysticism, but also a symbol of hopelessness, emptiness, melancholy and a reference to grief and death.

The original dark wave scene increasingly lost its importance in the black scene from the mid-1990s. This existed from then on, without referring to a certain musical style as a common denominator. Popular performers disappeared or changed their musical orientation and took on new influences that were not typical for the scene . Meanwhile, the grunge hype of the early 1990s activated media interest in subcultures. "In the years that followed, the cleverly fueled mass hysteria about anti-stars, Gen-X lifestyle, teenage rebellion and grunge look formed the ideal hook for the effective marketing of youthful identification poles [...]."

In the aftermath of this alternative rock hype, a habitus based on the origins of the black scene established itself in pop culture. New, previously unknown artists such as HIM , Nine Inch Nails or Marilyn Manson established themselves with anti-star existence and teenage rebellion in the scene as well as on music television and in the charts, while already popular scene artists such as Depeche Mode , Project Pitchfork or Wolfsheim were marketed accordingly in the media.

From this development, the style, as the core cohesion of the scene, gained the importance that music lost with the rapidly advancing musical development. A coherent and coordinated atmosphere encompassing all areas of life, with sometimes exaggerated caricature-like features, took up the space that the scene had given up when it turned away from the dark wave. Instrumental and everyday objects here have a decorative and thus symbolic character, which refers to contexts beyond everyday life. The unifying color black has a special symbolic value in the scene, and as an overdetermined symbol it is filled with a wide variety of interpretations. The color black becomes the leitmotif of the scene here, although “all individuality of the respective form of aestheticization”. "Black is [...] not just a color, it is an expression of attitude to life, tradition and attitude." Schmidt and Neumann-Braun also point out that the importance of authentic self-expression is ascribed to black clothing in particular and that the different currents in the Black scenes create their own styles, which extend from clothing to everyday objects. "So [...] the color black functions in the scene as a 'super sign' for a 'black cosmos', which is accompanied by a grown (and not created for provocation purposes) 'way of life' [...]."

In addition to the color black, aesthetic awareness and supposed individuality are at the center of the black scene. These factors require a constant individual self-presentation against the background of meaning of the scene's internal aesthetics. So the main points of social demarcation are stylistic and aesthetic, making style the core content. Hitzler and Niederbacher also refer to the "stylistic unity of music, body staging ('outfit') and 'way of life', which express central convictions, attitudes and values of the scene in an aesthetic way" as a focus of the scene that distinguishes it from society . This demarcation marks the level of identification in the scene. An authentically perceived scene appearance creates identification, and thus recognition, in the scene.

In 2004, Rutkowski named seven recurring interwoven themes that contribute to the habitualized thought and appearance of the black scene, shape the style throughout the development of the scene and which, in addition, connect the different currents in the scene with one another:

According to Schmidt, these topics provide the basis for the community's feeling of community. In this way, they represent a thematic complex with reciprocal effects that unites the different stylistic currents within the scene. The common core of this complex of topics is the passive demarcation from society, especially the fun society , and thus the emphasis on personal individuality by dealing with taboo topics and personal withdrawal from the social context of society as a whole, in favor of fantasy worlds and past eras.

“Due to the overriding value of individualism, the individual has the opportunity to act out independently of the clichés of the scene. A scene that allows sadness, grief and melancholy; Respecting the visual expression of the individual in every case, can never be the place for group dynamic processes that express themselves in an interactionist manner or in violence towards society as a whole. The rebellion that the individual may aim at through their scene affiliation (especially through their appearance) is always a silent rebellion that does not attack anyone directly, but is only 'a thorn in the side' of those who respond to the taboos (e.g. . Death, Satanism or even sex) react sensitively. "

romance

With the term romanticism, Rutkowski refers to the black scene as a connection with past times and the search for past values. With the aim of bringing something forgotten back to mind, the black scene sets the meaning-seeking individual against tendencies towards massiveness. The scene, however, regards the “almost religious cult around the idol triad progress, consumption and growth” with suspicion.

In this search for meaning and values in the past, Rutkowski justifies the clothing that reminds us of bygone times as well as the inclination towards castles, ruins, cemeteries and forests. In the thematic complex of Romanticism, dealing with past times and dilapidated places requires a search for peace, melancholy and aesthetics. The scene photographer and editor Marcus Rietzsch emphasizes the importance of the atmosphere of cemeteries as a place of peace and harmony.

death

The subject of death and the awareness of mortality have been consistently habitualized aspects of the scene since the Gothic and Dark Wave scene began. The symbolic color black can also be found in this complex of themes, as well as various band names, the tendency towards vampire and horror films , visits to the cemetery and morbid accessories.

Matzke sees in dealing with transitoriness a possibility for the black scene to rebel against the tendencies towards social constriction, as well as an active occupation in order to distance itself from the canon of values of the consumer society.

mysticism

In relation to the black scene, the term mysticism means general openness to supernatural experiences and the associated preoccupation with esotericism , mythology, occultism , rituals, fantasy , symbols and religion in the search for the “existence and experience of another, transcendent world ". Dealing with fantastic literature and fantastic films as well as dealing with spiritual topics is covered by the term mysticism.

religion

The topic of religion follows on from the topic of mysticism. The scene predominantly sees religion as an abstract topic that is critically and rationally questioned. Dealing with death also contributes to dealing with religious content. “Reasons for the increased focus on issues of faith lie in the continuous human continuation of the concept of being beyond death - and especially with a youth culture that deals with death to such a great extent, it is only natural that one should high occupation with religion is recorded. "

According to Schmidt and Neumann-Braun, the self-centered preoccupation with different religious teachings is an expression of the individualization and privatization of religion. In the scene, preoccupation with religions, rituals and ceremonies creates "a space for manifold fantasies and identifications around the more or less 'darkly connoted transcendent'."

In the context of the topic of religion, scene-goers and designers deal with various religious writings, practices and content. The intensity and individual consequences of the dispute vary. From convinced Christians to agnostics and followers of so-called new " natural religions " such as Wicca and Voodoo to atheists, there are various religiously convinced people in the scene. Theoretical and practical occupation with occultism and esotericism is a permanent part of the black scene.

Some scene designers and scene-goers deal intensively with occult topics, in particular with neo-paganism , chaos magic and thelema , from which frequent erroneous general judgments about the scene as satanists and sectarians have been shaped. Meanwhile, the “term Satanism frequently used in the media [...] in the black scene in relation to religion is mostly only found in the theoretical and historical discussion of the topic, for example through dealing with literature. Further preoccupation with Satanism [...] only takes place in marginal groups, if at all locally, and is by no means to be assessed as typical of the scene [.] "

Most references to thelemic and chaos-magical topics, but also to the Church of Satan, can be seen in Gothic Rock , Gothic Metal , Industrial Rock , Neofolk and post-industrial .

The band Current 93 named itself after a thelemic term for the inter-order totality of the thelemic movement. The band Fields of the Nephilim made intertextual references to statements by Crowley with the songs Love Under Will and Moonchild . Thelemitic and chaos-magical symbols and references can also be found in The Cassandra Complex , whose main initiator Rodney Orpheus is a member of the Ordo Templi Orientis , and Marilyn Manson , whose band founder of the same name Crowley counts among his most important non-musical influences. The Gothic Metal bands Tiamat and Moonspell were also interested in Crowley and were thematically influenced by his writings. Marilyn Manson also uses thelemic and chaos-magical symbols in the design of his sound carriers and music videos as well as direct quotations and allusions in his texts. An official Mansons fan club named itself accordingly Abbey of Thelema . Manson is also a member and priest of the Church of Satan , whose founder Anton Szandor LaVey wrote the Satanic Bible . LaVey, whose own work was influenced by Crowley, also had an intertextual effect on the black scene. Other Church of Satan members such as Boyd Rice and Michael Moynihan were still perceived as part of the scene in the 1990s.

In the post-industrial environment, the openness to the supernatural founded the term occulture , which was originally intended to describe that “a large number of music (or psychic TV ) fans not only because of their common taste, but also because of psychic TV conveyed common 'occult' interests. "

art

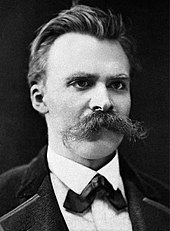

The scene is characterized by high artistic, creative and consuming demands. In addition to music, photography, painting and poetry are often creative activities for those in the scene. The design and manufacture of clothing is also part of typical activities. The abundance of creative activity and consuming preoccupation with literature, poetry and the fine arts is based on the desire to express one's own feelings or to find them confirmed in the works of others. Works of art preferred by the scene can be found primarily in the style epochs of Symbolism , Expressionism , Romanticism and Early Romanticism as well as Surrealism . In particular, the "literature is [...] a not inconsiderable influence on the self-positioning" of the scene-goers. A large number of the authors received belong to the canon of literature . In the specialist literature on the black scene, various authors are assigned great importance within the scene. For example, poets of Expressionism such as Gottfried Benn , Georg Heym and Georg Trakl , Romanticism such as Novalis and Heinrich Heine and Symbolism such as Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud are accorded great importance. Similar preferences can be seen among the preferred prose writers in the scene. In particular, morbid, frightening and fantastic literature is preferred in the scene. Classics of horror literature by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu , Edgar Allan Poe , HP Lovecraft , Mary Shelley , Lord Byron and Bram Stoker are just as much part of the scene's repertoire as canonized literature by Oscar Wilde , Friedrich Nietzsche , Fyodor Dostoyevsky , Hermann Hesse , Franz Kafka , John Milton , Donatien Alphonse François de Sade or Vladimir Nabokov . The scene's tendency towards fantasy not only favors the reception of canonized writers such as ETA Hoffmann and JRR Tolkien, but also the increased reception of non-canonized authors such as Anne Rice , Markus Heitz and Wolfgang Hohlbein .

The counterpart to literature is dealing with comics and films, which either take up an atmosphere that corresponds to the scene or subjects that are usual in the scene. Horror and vampire films and comics in particular appeal to the scene.

In these areas, too, they repeatedly produce their own productions, primarily independent films , video clips and comic strips. Furthermore, comics, television and cinema productions have been taking up stereotypes of the scene since the 1980s and have an interactive influence on the scene. The US crime series Navy CIS established a main character based on the scene in the forensic scientist "Abby" Sciuto . The series South Park introduced a group of children corresponding to the scene in season 7. The comic series Preacher , Sandman and X-Men have just such stereotypical characters. Among other things, the cartoon characters Ruby Gloom , Die kleine Gruftschlampe and Emily Strange are based on an aesthetic that corresponds to the scene and are often received in the scene.

However, the products by Tim Burton and James O'Barr are ascribed to special interaction with the scene . The graphic novel The Crow , written and drawn by James O'Barr, referred intertextually to the band Joy Division ; the main character of the story was optically based on Peter Murphy from Bauhaus . Nine Inch Nails and The Cure contributed to the soundtrack of the film adaptation . The film achieved cult status in the scene. The band The 69 Eyes named a song after the main actor Brandon Lee and adapted film sequences for the accompanying music video. The music video for the song Beyond The Veil by the band Tristania was cut from scenes from the film.

Tim Burton created a figure with Lydia Deetz in Beetlejuice as early as 1988 , who was not only attributed to stereotypes of the scene, but who also had an influence on the scene. Other Burton films such as Nightmare Before Christmas , Sleepy Hollow and Corpse Bride followed in terms of content and became, among other things through various fashion quotes, an integral part of the scene repertoire. The independent film Kinder der Nacht, recorded separately, became known as a feature film production of the German scene . The successor, which was filmed with Kelly Trump , Bela B. , members of Das Ich and Chris Pohl in 2002, has not yet appeared.

The artistic aspect of the scene also gave rise to various pictorial and collective works that deal with events and self-staging of the scene. The photographer Timo Denz published, among others, Modern Times Witches and FreakShowDiary illustrated books that are dedicated to the appearance of the scene. The book Whispering Whispers: Impressions and Thoughts from Leipzig , illustrated and edited by photographer Marcus Rietzsch, was dedicated to the audience, the ambience and the artists of the Wave-Gotik-Treffen in 2013 with articles by Christian von Aster , Klaus Märkert , Gitane Demone and many others The illustrated book Black Scene. Live photography 2003–2005 by Tim Rochels is dedicated exclusively to the artists of the scene and documents performances by various performers.

philosophy

In relation to the black scene, the term philosophy summarizes the employment and exchange on essential existential questions. So “in the black scene there is a high degree of inclination to think about life and existence itself, about the meaning and nature of being.” In this context, there is also a constant examination of mental disorders and people as social beings and society generally held. Existentialist , nihilistic , skeptical and atheistic writings are mostly supplemented by social psychological and sociological ones in search of knowledge about one's own existence and a meaning of being. This includes "different complexes of interests such as foreign / past cultures and traditions of thought [...], supernatural explanations of the world and cosmologies [...], the simply 'unimaginable' '[...] as well as phenomena, ideas and theories relating to man and his existence [...]." Rutkowski owns a corresponding collection of scientific and philosophical literature, with works by Fromm , Nietzsche and Sartre, which are regularly owned by members of the scene. Meanwhile, the dispute with authors like Evola , D'Annunzio and Ernst Jünger also led to the accusation of affirming proto-fascist ideas.

In dealing with philosophical, sociological and psychological topics, there are not only private but also intertextual references. Some performers created entire albums on psychological topics. With The Downward Spiral, Nine Inch Nails conceived an album about the efforts to escape the control of religion and society through the unreserved expression of sex and violence . With Resurrection, the band Janus created an entire album based on traumatic events and their effect on the human psyche.

“Traumatic events such as For example, the death of a loved one in You Look Like Always or the nightmare of a dark family secret in Survival are the greatest threats to our fragile sanity. All the texts of 'Resurrection' move on this boundary between delusion and the will to survive. "

The band Oomph! With the album Wunschkind produced a concept album about traumatic childhood memories, primarily experiences of abuse and violence. Marilyn Manson created with Holy Wood and Antichrist Superstar albums that dealt with issues of society as a whole.

Body feeling

The sub-scenes unite in a self-portrayal body concept, which "contains an erotic representation of the body [and] appears more revealing than it is in its entirety." The staging of oneself and one's own physicality is an inherent part of the individualistic conviction that the scene members united. This self-expression takes place through body-hugging clothing, piercing jewelry and tattoos . This self-staging is meanwhile a conscious and targeted presentation of oneself, which rarely goes beyond the scene's own meeting points. The creation of a meaningful connection between clothing, the social group and the person takes place here on the basis of mutual recognition. The often made attribution and equation of erotic self-portrayal with sexual permissiveness turns out to be a prejudice. The black scene also distances itself from the fashionable BDSM scene in its active implementation. Nevertheless, the scene members meet the BDSM supporters openly and accepting. A practicing overlap, as represented by Umbra et Imago , Die Form or Grausame Töchter , is seldom found in the scene.

history

Various fashion and musical currents influenced the black scene from the very beginning. Musical and fashion innovations and further developments in the scene emanated from formative trends. Beyond such significant phases, individual currents occasionally stopped working. Most of the time these currents were weakened and had no deeper influence. Many of the different currents have their own unique selling points, so that we can often only speak of overlays and influences from and with the corresponding scenes and youth or subcultural groups.

Due to artistic advancement and particular popularity, some interpreters asserted themselves beyond the period of formative phases. Important publications and individual performers from earlier phases were later found at festivals and major events in the scene, and popular performers from past trends were frequented after the current trend subsided. For example, performers such as The Cure , Depeche Mode , Rammstein , Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds or Marilyn Manson are considered important for and in the scene regardless of genre.

Emergence

The classic black scene was initially formed in the 1980s and in the first half of the 1990s from the independent and dark wave movements, whose members originally came from youth cultures such as punk , new wave , gothic , new romantic or in the post Industrial environment were anchored. The followers of this early black scene were called "blacks" because of the color of their clothes or their outlook on life, or "wavers" because of their preferred forms of music. With the disintegration of the wave culture, however, the term "waver" disappeared from German usage.

In the course of the 1990s, various culture and style terms became comprehensive super terms in the black scene, which were applied to performers from outside the genre, as well as fragmented cultures, in some cases completely independent musical styles. This form of use is criticized by actors and observers of the original cultures and genres as incomprehensible and absorbing misuse. From the diversity of the music received, cultural and social scientists coined the delimiting and neutral generic term black music as a comprehensive collective term for music received and created in the context of the scene, which contrasts with the continued use of the style by others. The concept of the black scene behaves in an analogous manner, in contrast to frequently attempted self-attributions such as Gothic or Industrial .

Establishment

In the second half of the 1990s there was an increasing number of overlays with parts of the metal movement or the BDSM scene, with the BDSM look in most cases only being adopted as a fashionable element by the “blacks” and now a common style element in the Scene is represented. The term “black scene” now implies and includes smaller and occasionally changing currents such as the cyber and electronic scene, visual kei or marginal areas of the Wicca and medieval scene . "Within the black scene there are many sub-styles, whereby the external appearance is mostly closely linked to the respective music styles to which the respective scene-goer is attached." With each change of generation, several subcultural overlays emerged, as a result of which several parts of the black scene do not appear assign more to certain subcultures. In the archive of youth cultures , the black scene is described as an “alternative movement of young (and no longer quite so young) people whose appearance is remarkably diverse”. "Symptomatic of this diversity is the difficulty in finding a suitable generic term for this scene."

First mixed cultures

From the mid-1990s onwards, the black scene grew noticeably, so that new, sometimes rival, youth cultures developed. One of these cultures was the "Gothic Metal scene", which emerged from the fusion of the genres Gothic Rock and Metal to Gothic Metal . The members of the mixed culture that arose on this basis did not use any self-designation. They were - depending on the individual opinion - either attributed to the metal movement or the Gothic culture.

“With an almost meiotic approach, they [ Paradise Lost ] created a new style in the early 1990s with the album Gothic , which combined the elements of Gothic Rock and Death Metal. Gloomy men, for whom Gothic Rock did not produce hard guitars, and Metal types who could no longer hear the eternal thrashing around grew together to form a new fan base. "

In addition to Paradise Lost, the bands Tiamat and My Dying Bride contributed to the establishment of the new style in the scene. Their influence favored the success of other bands such as Crematory , Theater of Tragedy and Moonspell . Whereupon already established scene interpreters like Lacrimosa or Secret Discovery recorded metal elements. The Gothic Metal trend was short-lived and was partly criticized by musicians and followers of the scene. However, from the mid-1990s onwards, it formed the breeding ground for a following within the black scene that was flowing into Dark Metal , Dark Rock and Symphonic Metal .

Changing development

In the mid-1990s the importance of the originally formative musical styles in the black scene decreased. The once most important currents of the scene, Gothic and the superordinate Dark Wave, lost the breeding ground for this scene as many of the main bands reoriented themselves or even dissolved. Last but not least, the lack of new performers and the new impulses from old greats opened up new musical fields in the entire scene. The black scene quickly established itself as a subcultural milieu in social perception and experienced a high phase with high media and social interest.

“There was this revival in the nineties - all of a sudden an incredible number of people were interested in our music and our clothes. The scene moved a huge step towards the mainstream. Today [2013] one can no longer speak of a youth culture. The protagonists who were there from the start are now about to retire. "

New styles of music such as New German Hardness , Gothic Metal and parts of Alternative Metal found their own place in the black scene, which over time almost completely displaced the original styles.

Similar upheavals took place several times in the following years and once atypical styles of music became an integral part of the black scene. Since then, medieval , sleaze and dark rock as well as future pop , synth rock , aggrotech , big beat , dark and symphonic metal have been able to record their own high phases in the black scene. Alexander Nym describes the diverse styles and currents of the scene as a heterogeneous mass that can hardly be overlooked, which sometimes leads to divisions within the scene itself. “Few scene-goers still have a real overview of this diversity; the scene is divided into various sub-currents that are sometimes diametrically opposed to one another, both in terms of clothing and musical preferences. "

With the first upheaval in the scene in the mid-1990s, various bodies tried to unite the expanded spectrum of music under one name, which resulted in terms such as Dark Alternative Music , Dark Music or Black Music . None of these terms has so far been able to establish itself as a generally applicable and comprehensive term in the scene. The term “Dark Music” first appeared in writing in the mid-1990s through Entry magazine . which carried this designation in the slogan magazine for dark music, cult (ur) and avant-garde on the front page. In the scientific literature on the scene, the term black music is preferred.

Black techno music like Aggrotech and Future Pop also emerged in the late 1990s, and techno black like Big Beat was received in the scene from then on. With the influence of metal, alternative and techno, there were hardly any taboo areas with regard to the musical interests of the scene. In addition, since the first upheavals in the scene, bands that previously did not correspond to the styles assigned to the scene have marketed themselves via a corresponding image as artists of the black scene. A circumstance through which genre terms were further watered down and titles such as Industrial Rock, EBM, Gothic Metal or Gothic Rock were applied to bands with a different style, so that, among other things, technoid-influenced music is titled and perceived as EBM or Industrial. This development is particularly criticized by long-time members of the scene, but interpreters of the different musical styles often react by rejecting the respective names. In particular, the term Gothic , "under which the dark alternative culture mostly trades in the media", is also being used in an inflationary manner as a music journalistic term with regard to the black scene. "Which not least has to do with the linguistic conventions of the (English-speaking) music press, which likes to describe everything as 'gothic', which at first glance can be assigned to the black scene."

Commercialization

By the end of the 1990s at the latest, the scene began to be widely commercialized , supported in particular by the big media outlets Orkus , Zillo and Sonic Seducer . Popular performers, who were assigned to the black scene in their appearance, made the leap into the top of the charts since the 1990s. In addition to the representatives such as The Cure and Depeche Mode , who have already been popular since the 1980s , this achieved, among others, The Prodigy 1996, Rammstein 1997, Witt 1998, HIM 1999, Marilyn Manson 2001 and with sometimes more, sometimes less changed sound Wolfsheim 1998, Oomph! 2004 and Rammstein and Unheilig 2009.

Until the mid-2000s, "the content of the black scene was exploited in popular music culture due to the market potential of its large following [...] and too often degenerated into a marketing-technical scare to raise record sales." Even non-genre artists such as Lacuna Coil or Evanescence , which are “stylistically closer to Nu-Metal acts like Korn or Linkin Park than to models” from the black scene, were marketed as part of the scene and received by parts of the scene.

A highlight of this commercialization and appropriation of the German scene was the media-effective attempt in the mid-2000s to market performers such as the casting group Nu Pagadi or the pop singer La Fee as part of the black scene via an appropriate image and some music videos adapted to this image. The pop project Unheilig took a further step in this development with an image typical of the scene and the musical turn to German Schlager , which brought success to the project around the singer Der Graf on a national level. Even before the band's great success, which began after the Unheilig victory at the Bundesvision Song Contest at the latest , scene designers such as Myk Jung and Michael Zöller complained about the scene's turning to hits using the example of the band.

Internal conflicts

With the increasing growth of the scene with a far-reaching confusion of musical styles, internal criticism of the development of the scene grew. The successes of performers assigned to the scene or marketed as part of the scene contributed to the conflicts. The rapid growth of the scene without new people in the scene having to deal with the values and themes of the scene leads, according to the critics, increasingly to a loss of scene identity and community in favor of one-dimensional segregation . As early as 1998, at a panel discussion at the Wave-Gotik-Treffen, people who played a part in the scene criticized the increasing musical opening of the scene, given the appropriate image, and a blatant lack of interest in the social and musical roots and contexts of the scene.

“Any kind of scrap is being sold to us as a new trend, optical high-gloss tapes deliver inferior performance. The music of bands like Call or Gothic Sex z. B. have nothing to do with their image. This is rock of the late 70s with Gothic clichés "

In 2000, as part of the anthology Gothic! The scene in Germany from the point of view of its creators, several well-known actors in the scene, the development of the scene music and a lack of awareness of the scene history within the scene itself.

The party aspect of the 1990s, which was embodied by the techno movement and the fun society and originally rejected by the black scene, flowed into the scene and was vehemently rejected by parts of the scene. According to Sonic Seducer employee Frauke Stöber, "the black scene is still a counterpoint to the conformist rest, but has [but] incorporated the spirit of the nineties."

With the increasing mixing of once atypical styles of music, beyond the post-punk and post-industrial spectrum, there was increased criticism from previous designers and recipients of the scene. Tilo Wolff complained in 2005 that the scene had moved away from the original movement and that the music had developed into something archaic that was incompatible with his musical ideas. In 2010, Oswald Henke criticized the loss of the former scene identity through the blending with the techno scene through the current known as cyber as "black ball man " as well as the confrontation with "black hit ".

“At many events in the last few months I got the feeling that I was the wrong person in the wrong place. [...] Unheilig , Combichrist , Tumor and all the others have also broken into our 'beautiful eternal island'. In Berlin, however, we have another problem: The strictly commercial club K17, which has destroyed a lot of underground culture with free events with up to five floors here in recent years and has unfortunately also massively established the aforementioned junk bands. "

In particular with the erroneous appropriation of genre terms and the omnipresence of the music associated with the newer currents, the efforts of other scene-goers to distance themselves from the new developments grew. This development was already apparent in 2004 when there were anti-future pop events, and continued in the rejection of Aggrotech and Rhythm 'n' Noise . The cyber group in particular is rejected by other scene-goers because of the technoid music they have received. These conflicts are increasingly followed by a spatial delimitation of the different groups of scenes, up to and including complete “tendencies towards splintering”.

Appearance of the scene

The black color and an aesthetic awareness based on the black scene and its themes characterize the appearance of the scene, especially against the background of constant self-presentation. Body jewelry such as piercing jewelry and tattoos are therefore just as common as body-hugging clothing. Jewelry is mostly worn in silver and steel. Jewelry often includes animal symbols in the form of spiders, snakes and scorpions as well as religious, mythological and occult symbols. In addition, materials such as lacquer, leather, mesh and velvet are typical of the scene. The color black dominates the clothing style of the scene, but contrasts are also common. Furthermore, items of clothing that exude a pronounced androgyny, such as men's skirts , are often to be found. The appearance of clothing and jewelry meanwhile ranges from inconspicuously discreet to extravagant. Period clothing from baroque , rococo , art nouveau as well as medieval fantasy costumes and similar overall stagings can occasionally be found in the scene. Fashionable influences of the different currents, up to unique selling points such as those of cyber culture or steampunk , are also common. Since its inception, the black scene has "differentiated a range of groupings or sub-scenes, which results in very different degrees of style, internal cohesion, independence and proximity to the ideal-typical Goth style."

Development of trendy fashion

The different currents of the black scene often influenced each other in the entire development of the scene. Since there were always dominant styles and style elements in the different time periods, these were often eclectically combined with other current or past styles, which means that the scene cannot be reduced to a certain appearance and the general appearance of the scene usually corresponds to a mixed form of different style elements. A general similarity can only be determined in the dominance of the color black. The independent fashion styles that were brought in were occasionally retained beyond the high phases of the respective musical styles due to the takeover by other splinter cultures. The individual style elements of the splinter cultures can be found in their respective representations.

1980s

The black scene emerged at the end of the 1980s from the independent environment of the 1980s with various subcultural groups whose musical core was post-punk , post-industrial and dark wave . In this first loose network, the Gothic scene , Waver , EBM followers , the Neofolk scene as well as followers of the different post-industrial forms operated.

The individual subcultures brought their own fashionable elements into the superordinate scene, which were considered to be the unique selling points of the respective groups. While from Martial Industrial , post-punk and Neofolk the slope was introduced to uniforms and camouflage uniforms, were from the EBM and synthpop , among others, Flat , tank tops , bomber jackets , polo shirts and lace-up boots ( Doc Martens introduced). From the post-punk came fashionable elements of punk as well as the first bondage elements. The range of fashionable elements in the Gothic scene led to separate splinter cultures in the corresponding sub-scene as early as the 1980s .

In particular, these splinter cultures of the Gothic scene produced items of clothing themselves or traveled to London to shop and sold items of clothing to one another via fanzines . Clothing based on punk, but equally independent items of clothing such as sarouel trousers and accessories such as Egyptian jewelry and independent hairstyles or elements from clothing styles from the Renaissance were just as present here as clothing based on the Victorian era or Art Nouveau. The respective clothing styles were rarely found in their pure form. As a rule, it was about individual clothing components from different eras that were combined with one another.

1990s

The increasing growth of the black scene from the end of the 1980s, under the increasing influence of music styles that were not typical of the scene, led not only to the musical but also to a fashionable mixture with other scenes. Fashionable elements from the fetish and BDSM scene, alternative rock , metal and medieval rock were incorporated . Previously rarely available accessories from the bondage and fetish scene as well as vinyl and latex clothing increasingly found their way into the scene, which until then had been more focused on velvet, brocade and in places leather, jeans, fabric and linen. From metal, the tendency towards band shirts and studs was particularly taken up. From medieval rock too, medieval jewelry and kilts in particular flowed into the scene , as did accessories such as drinking horns . Closely connected with medieval rock, parts of the role-playing scene, especially the LARP scene, with epoch-making and fantastic overall costumes became part of the scene fashion. The mutual interest of the medieval scene, LARP scene and black scene meet in the aesthetic self-portrayal as Vikings and damsels as well as vampires , zombies or werewolf .

The spread of fashion has meanwhile been professionalized by mail order catalogs that are specifically dedicated to the scene (X-tra-X) or the scene with supplies ( EMP ). In addition, shops were established in metropolitan areas, which were exclusively or predominantly dedicated to the scene audience. In particular, the adoption of stereotypes associated with the scene in films, television series and music videos contributed to a broader perception of fashionable elements in the scene.

Body-hugging clothing, tattoos and piercings also established themselves as fashion accessories in the 1990s. Keith Flint, singer and dancer of the band The Prodigy , made a significant contribution to the acceptance of piercing . Some other interpreters of alternative, primarily alternative rock and alternative metal , presented themselves in music videos by representatives of the black scene in a fashionable and, in some cases, also musically influenced, and brought further stylistic elements into the scene. In the meantime, former unique selling points became increasingly blurred in a general scene appearance by a broad scene audience, while in parallel, however, equally isolated splinter cultures remained constant and in some cases separated.

2000s

The increasing popularity of the scene towards the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s led not only to a boom in the scene but also to the takeover of fashionable elements by large retail chains such as H&M .

In the further course of the 2000s it was less musical than fashionable subcultural currents such as visual kei and steampunk that gained a foothold in the black scene. Fashionable accessories and individual items of clothing from these independent scenes can be found as well as complete disguises. The oriented to the techno-culture of the 1990s, youth culture fashion trend of cyber developed after 2000 in the club event of the black scene, bringing features such as wide falling flares , ultraviolet lights , nylon -Shirts, tight nylon quilted jackets, neoprene -Jackets and hair extensions made of plastic and foam into the scene.

General scene appearance

Occurrence of different currents within the scene

The visual kei borrowed Lolita fashion

Cyber look with face mask and matching color choices

Steampunk look

Goth look

A musician from Nachtgeschrei in a medieval rock look with a modernized kilt

Political tendencies

The black scene primarily takes a politically passive stance. According to Matzke, the scene is characterized by conservative values . As the cornerstones of this conservatism, he names skepticism towards consumer society, doubts about the reformability of industrial society, the tendency towards mysticism and the passive rejection of modernity. Alexander Nym, on the other hand, calls the scene “fundamentally apolitical” and points out that the people in the scene “reluctantly let themselves be taught”. The proportion of politically motivated people is therefore low. However, since the scene does not have a homogeneous structure and is made up of different youth cultures and individualists, divergent political tendencies can be found.

The charge of right-wing extremism

On the outer edges of the neofolk and martial industrial scene, whose members form an independent subculture and have no direct contact with Gothic culture, points of contact arise between the black scene and the new right . Parts of the scene describe these contacts as well as the publications and actions of individual actors with a right background as an attempt at infiltration. This attempted infiltration, however, is perceived as a more global phenomenon that can also be found in other subcultures and is not limited to the black scene.

The debates about possible influence by right-wing extremists took place predominantly in the 1990s. Common interests between right-wing extremists and the black scene were found particularly in esoteric , mythical and historical topics. In addition, the interest in breaking taboos and the will to provoke offered the opportunity for discussion. The generalizing stigmatization of the scene as a new right-wing radical movement occasionally haunted the press, but was rejected even by left-wing observers:

“[T] spit of the predominantly gloomy image of a gloomy scene, it would be nonsense to now put the entire scene in the right-wing extremist corner. Such reactions are left to the Bavarian Radio and the Catholic Church . "

In addition, counter-initiatives such as the “Goths against the Right” or “Black instead of Brown” quickly formed. The broad mass of the scene remained unimpressed by the efforts to create their own scene and acted emphatically individualistic. After the turn of the millennium, interest ebbed noticeably after the New Right was unable to establish itself in the scene. Rather, the New Right could only refer to “the same right-wing representatives of the black scene in articles and reviews”. "Despite the theoretical affinities, they were only able to activate contacts with right-wing musicians and authors."

Zillo and the boy freedom

Alfred Schobert analyzed the first scandal of a burgeoning connection for the magazine Spex in 1996. He attacked the outrage of the label Strange Ways Records over the cooperation of the scene magazine Zillo with the new right newspaper Junge Freiheit in the form of advertisements for Junge Freiheit im Zillo and the joint author Peter Boßdorf on. Meanwhile, Schobert also explains the basis of a possible rapprochement between the scene and the New Right:

"The greed for the mysterious, for the only initiated, ie esoteric knowledge and the longing for hidden meaning form the structure that makes the crypt scene attractive for the 'New Right'."

Schobert adds, however, that the alleged radicalization of the entire black scene should rather be understood as a dangerous press construct that creates identification. The points of contact between the New Right and Black Scene would still exist, which in turn creates conflict with the anti- fascist scene. In 2007 at the Wave-Gotik-Treffen there was a violent confrontation between antifa activists and supporters of the scene, in which a member of the scene was injured in the back of the head.

VAWS and Josef Maria Klumb

The VAWS publishing house is seen as an important authority in the discussion about possible influence from the right , which in the mid-1990s published the Independent News , which was classified as right-wing extremist by the protection of the Constitution , and has various books by the right-wing erotic Jan Udo Holey in the publishing program. According to Schobert, VAWS stands out as the right mail order company with its music program. "While other right-wing mail-order companies offer sound carriers for those who are nostalgic for the Wehrmacht, people who are homeless and bald, VAWS is also looking for customers in the dark wave scene."

In May 1994 the VAWS published the free 16-page A4 glossy sheet Undercover . Undercover presented apparently apolitical bands, events and recreational opportunities that were primarily aimed at the black scene. In addition, the publisher's owner Werner Symanek placed mail order ads in music magazines such as Sub Line . With the ordered goods, however, one also received propaganda material from the radical right-wing Independent Circle of Friends. In the same year VAWS therefore became a topic in the scene. Magazines and labels were informed by fans and mostly reacted with a boycott of the advertisements and labels such as Gymnastic Records by stopping supplies to the VAWS. In the same year VAWS began to publish its own interpreters who should also serve the black scene. The first album to appear was Inception by the largely unknown electro-wave formation Experience of Nation. Two years later , Josef Maria Klumb, who in the meantime had come under criticism for his statements on a Zionist world conspiracy, arranged a sampler dedicated to the propaganda director Leni Riefenstahl . Klumb, already active in various bands and projects and known in the black scene, had to leave the NDH band Weissglut in 1999 under pressure from the record company Sony BMG . He then had other projects, such as the dark wave bands Forthcoming Fire and Von Thronstahl , transferred via VAWS and his own label Fasci-Nation, whereby Klumb and his music increasingly disappeared from the focus of the broad mass of the black scene. In 1998 VAWS published the first Maxi-CD of the rhythm-and-noise project Feindflug I./ST.G.3, which was not self-distributed . Feindflug, who became known in the scene at the latest in 1999 with the maxi CD Im Visier , later distanced themselves from the political orientation of the label and declared that they had no knowledge of the company's ideology. The VAWS did not give up its efforts for the scene despite growing opposition. In both 2004 and 2010, Werner Symanek and his VAWS tried to organize festival events, which in 2004 were based on the resistance of the Austrian scene against the VAWS festival "Holy Austria", and in 2010 on the resistance from the Ruhr area, against the "Independent Ruhr Festival" , failed and were canceled.

Martial Industrial and Neofolk

In the black scene itself, especially since the 1990s, Martial Industrial and Neofolk have been discussed repeatedly with a view to influencing the right. Both styles cover topics that can be interpreted in a right-wing context. The war theme, military look and the Leni-Riefenstahl aesthetic that is often used in the Martial Industrial and the mostly esoteric and folkish content of Neofolk offer a corresponding projection surface , which was partly filled and used by representatives of the New Right . With many bands and projects, the political classification is ultimately more difficult. In particular, the neofolk bands Death in June , Blood Axis and Sol Invictus were discussed controversially for a long time in the scene without conclusive knowledge. The design of sound carriers in Nazi aesthetics, the setting of the Horst Wessel song and the use of a varied SS skull as a band symbol brought Death in June repeatedly into discussion and criticism. The effect of an appropriation from the right could still be observed, even without being able to finally clarify the intention of the projects, for example, the former author of Junge Freiheit, Gerlinde Gronow, described her turn to the right-wing scene based on corresponding bands.

“I […] come from the wave scene myself - keyword Death In June, Sol Invictus, NON . This made me aware of authors like Evola , D'Annunzio and Ernst Jünger . Although I originally approached these bands and writers critically, I was gradually brought into line with the undeniable fascination that emanates from this world, so that the step to Junge Freiheit seemed to me to be a natural consequence at some point. "

In addition to the authors named by Gronow, the homosexual Japanese writer and nationalist political activist Yukio Mishima represents a significant intertextual influence in the Neofolk.

Even Michael Moynihan and his band project Blood Axis are often a neo-pagan - esoteric , right counterculture with reference points to positions of the New Right and fascist ideology associated with a scene of Moynihan felt at least sometimes explicitly linked.

“I respect many of the ideas of the 'New Right' and the Third Position. The people I met who are involved with these groups (Junge Freiheit, Orion, Aurora, The Scorpion, Vouloir, Lutte du Peuple ...) are all exceptionally intelligent and open-minded. I hope they continue to gain influence for Europe's future. "

In the discussion about the possible right-wing extremist orientation of performers such as Death in June, Blood Axis or Sol Invictus, the advocates of the performers often advocate the thesis that it is a matter of deliberate provocations, staged taboos or artistic implementations of criticism of everyday fascism. The singer Gitane Demone also represented this thesis in an interview with the organization Goths against the law . In the meantime, these musical styles and their supporters in the black scene can only be made out peripherally, so the discussion about the political orientation of the Neofolk scene has become more of a marginal note.

Provocation and breaking taboos

Meanwhile, the provocative play with National Socialist elements was inherent in the scene from the beginning. The former initiators of the first musical wave had already started. In 1976 Siouxsie Sioux wore a swastika armband for their first appearance at the 100 Club Festival, for which Siouxsie and the Banshees , then a punk band, had even formed . A year later, Bernard Sumner opened a gig by the punk band Joy Division , in the opening act of the Buzzcocks , with the words "Do you remember Rudolf Hess ?" Joy Division, which after a fictional division of comfort women from the concentration camp - novel The House of Dolls had named, were aware of the possibility to polarize with such statements, and brought so this week. In June 1978 they followed up with the EP An Ideal for Living , on the cover of which, in addition to lettering in broken script , a Hitler Youth drawn by Bernard Sumner beats a drum.

Since then, the provocative game with National Socialist symbols and the preoccupation with the subject of fascism have appeared in the scene in ever new ways. This dispute takes different forms; While the martial industrial band Laibach wants to stimulate discussion and reflection on pop culture with parodying and overstylistic confrontations with fascist content and symbols , Rammstein and Joachim Witt flirted with the videos for Stripped and Die Flut with an aesthetic that is otherwise martial industrial and Neofolk, however, reached a far larger audience. While Rammstein referred directly to Leni Riefenstahl, the music video for Die Flut was based on Sergei Michailowitsch Eisenstein , but like Stripped , it offers clear links to a fascist aesthetic.

Other interpreters of the scene, such as Marilyn Manson or the Undead , used and still use less themed fascist symbols in their self-portrayal. The constant provocation, stimulation of discussion and the will to break taboos with regard to fascist symbols and content continue to make the scene a target for anti-fascist organizations.

The flag of the British Union of Fascists used Marilyn Manson in a modified form for the design of the album Antichrist Superstar

The symbol of the Hird , a paramilitary defense organization of the Norwegian Nasjonal Samling , has been part of the name of the band Untoten in a slightly different form since 1999

Ljubljana designed her album Opus Dei with a composite of axes swastika , originally by John Heartfield dates

Laibach, Death in June and other performers used the symbol of the SS Division Totenkopf

Anti-fascist statements

1st Dark-X-Mas Festival 1992

After right-wing extremist violence in Germany had escalated in the early 1990s , Bruno Kramm from the NDT project Das Ich wrote a statement in the run-up to the first Dark-X-Mas festival, which was to be published as a joint declaration by all participating bands. On the occasion of the riots in Hoyerswerda, Kramm's declaration was directed against “assassinations on asylum seekers' homes and memorials, attacks on foreigners, Nazi marches and the […] blatant, aggressive anti-Semitic provocation” and advocated a clear position against the rising right-wing extremism, so should the "neo-Nazism [...] to be fought as neo-Nazism and not as a result of anything." The I, your lackeys , Project Pitchfork , Goethe's heirs , Love Like Blood , YelworC , Plastic Noise Experience , Trauma , the organizer of the Dark-X-Mas -Festivals Sven Affeld (Gift) and Gymnastic Records signed. Only Death in June refused to sign and take part in the festival on the grounds that it did not want to support a ready-made political statement, to refuse all political dogmas and all propaganda, and not to have to be explained that mindless violent attacks were racist , sexist or political justification are pathetic crimes. Bruno Kramm replied that a call for humanity would not correspond to any political dogma or propaganda.

In this context, Death in June already idealized “the fight, the war and an associated image of masculinity in affirmative references. These ideals refer to the Conservative Revolution and Italian Fascism. ”In particular, intertextual and creative references to thought leaders, artists and ideologues of fascism and nationalism such as Leni Riefenstahl , Ernst Röhm , Julius Evola , Karl Maria Wiligut , Alfred Rosenberg , Oswald Spengler or Ernst Jünger had previously shown that Death in June was open to right-wing extremist content.

According to a statement by Ernst Horn ( Deine Lakaien ), Pearce refused to sign a joint declaration by the performers against racism and neo-Nazism at the Festival Of Darkness in 1994 .

The arguments about the 1992 Dark-X-Mas-Festival have been considered the first internal scene scandal since then and justified the argument about new right tendencies in the scene, which mostly also had Pearce and Death in June as their topic.

Musical confrontation

The theme continued to accompany the scene and many bands commented on their music. For example, Die Krupps took a stand against xenophobia and racism in 1993 with the song Fatherland, as did And One with the song Deutschmaschine 1994. Other performers of the scene who, over the years, also opposed a racist, right-wing extremist, anti-Semitic or fascist ideology in their music, were e.g. . B. London After Midnight (Revenge) , Das Ich (Satan's new clothes and reflex) , ASP (Say No!) , Janus ( Exodus / The Ballad by Jean Weiss ), Shnarph! (The egg dance) or Velvet Acid Christ (Futile - Nazi-Bastard-Mix) .

Wave Gothic meeting

After the influence of right-wing extremists in the black scene was repeatedly discussed in the 1990s, a broad discourse took place. Schobert predicted in 1997 that “the conflict over the penetration of right-wing extremist tendencies into the dark wave scene will continue to develop out of the variously interwoven music scenes. There are many signs of such a positive development, even if the debate was slow. Some musicians in particular [take] their responsibility for the young fans very seriously. ”The possible influence was discussed at a panel discussion at the Wave-Gotik-Treffen in 1998. In the following year, the organizers planned to dedicate a separate item on the program to the topic with “The brown flood”. The panel discussion had to be canceled because the critics of right-wing tendencies refused to sit on a panel with the new-right musician Josef Maria Klumb . Campino canceled due to scheduling reasons; the representative of the "Goths against the Right" invited in his place did not want to take part in offering Klumb a political forum. Alfred Schobert, who was invited instead, also canceled, as he “did not want to expose himself to a 'discussant' who had repeatedly assaulted his critics or beat them up in the past”.

The active engagement with the problem of right-wing extremist content nevertheless remained part of the scene actors. Mila Mar 2002 and ASP 2009 took a stand on the WGT program of the respective year.

reception

Media reception and attributions

Since the 1980s, press reports on the scene, which liked to make use of common clichés such as Satanism , desecration of the grave , National Socialism and sadomasochism , were common. According to Schobert, however, these reports belonged more to the ranks of lurid sex-and-crime fiction . At the turn of the millennium, media interest in the scene reached some unintended highs.

On April 20, 1999, two students committed Columbine High School a near Littleton, Colorado school shooting . The perpetrators were interested, among other things, in music from the black scene - a circumstance that made the scene, and especially Rammstein, KMFDM and Marilyn Manson, appear as a breeding ground for a misanthropic attitude that did not shrink from murder. In this regard, Rammstein , KMFDM and especially Marilyn Manson were charged as the inspiration for the act. Marilyn Manson canceled several concerts and addressed the circumstances of the massacre, a year after the fact, in her album Holy Wood - In The Shadow of the Valley of Death . The band especially dealt with the American gun lobby. Singer Brian Hugh Warner also had a say in the Michael Moore documentary Bowling for Columbine . Other bands belonging to the black scene also addressed the events. The symphonic metal band Nightwish treated the two gunmen and their emotional state in their song The Kinslayer . The Aggrotech project SITD also addressed the events in the song Laughingstock , as did the band Untoten with the piece Church of Littleton .

In 2000, four young people killed themselves in Klietz ; according to the press report, four more tried. The band Wolfsheim , among others, was used as inspiration ; In addition, the Wave-Gotik- Treffen was transfigured into a conspiratorial, occultist, satanic meeting.

" Occultism , contacts in the Gothic scene and chatting in the dark forums of the Internet promote the longing for death."

The Witten murder case in July 2001 sparked renewed interest in the scene. In the course of the murder of Witten, called “the murder of Satans in Witten” by the newspaper Bild , Soko Friedhof and Wumpscut received special media attention. These projects worked on the reporting differently, in particular both projects used different samples of the police press conference for new songs or remixes.

Scientific reception

An extensive, content-based, popular scientific and scientific discussion of the scene began in 2000. Before that, only a few scientific publications had sporadically dealt with the scene. The Gothic! Published in 2000 by Peter Matzke and Tobias Seeliger ! serves primarily to present the German scene in articles by various scene designers. In the same year, the Gothies , which focused on the scene fashion at the time, appeared - youth culture in black by Schmidt and Janalik. Die Gothics , from 2001, by Klaus Farin and Kirsten Wallraff, strives for a self-portrayal of the scene similar to that of Matzke and Seeliger, but documented various interviews and contains the first approaches of a social and cultural studies view of the scene. In 2002 Andreas Speit published the first critical German-language book on the scene. Aesthetic mobilization , however, focuses on the affirmation of new right ideology in connection with the musical styles Neofolk and New German Hardness. Speit thus followed up on similar disputes that had started in the second half of the 1990s by Alfred Schobert in Spex and Martin Büsser in the Testcard book series .

In 2004, the first primarily cultural and social science debates with the scene appeared. Roman Rutkowski published his master's thesis with a study on “Stereotype and prejudice in relation to youthful subcultures using the example of the black scene” under the title The Charisma of the Grave . The social scientist Axel Schmidt and the media scientist Klaus Neumann-Braun , on the other hand, examined in practical studies, in the book Die Welt der Gothics , the scene ethnography and community practices of the scene. In the book Flyer of the Black Scene of Germany , published in 2010, the cultural scientist Andrea Schliz examines the visualization and staging of flyers as a communication tool for the scene. In the same year, the social scientist Alexander Nym published his collective work Schillerndes Dunkel , which serves both to portray the scene itself and to offer a sociological consideration of the scene's ethnography and contains contributions from scientists and scene designers. In 2013, the musicologist Bianca Stücker published her doctorate Gothic Electro on the functionalization of technology within the subcultural context of the black scene.

Well-known events

Some festivals such as Blackfield, Castle Rock and Dark Dance focus exclusively on performers from the black scene. However, the bands and artists of the black scene also appear at events such as the Bochum Total or the Wacken Open Air , which cannot be assigned to the black scene. Meanwhile none of the festivals claims to do justice to all represented styles of the black scene.

|

|

|

Print media

In the past

|

The Glasnost Wave magazine was a music and cultural magazine of the early black scene. It existed from 1987 to 1996 and was therefore one of the oldest of its kind - even before magazines like Zillo , Sub Line and Gothic Press were published . Sections such as Gothic Rock , Industrial , Neofolk , Dark Ambient , Ethereal , EBM and Cold Wave were covered . Initially based in Freiburg, the editorial management relocated to Hamburg in the 1990s. The record company of the same name, Glasnost Records , was bound to the magazine .

In the present

|

|

Well-known magazines on the black scene in the German-speaking area currently include Orkus , Sonic Seducer and Gothic . In addition to these print media, some of which are commercially oriented, there are a large number of other magazines, such as Black , Transmission or Graeffnis , whose content is practically independent of the mainstream.

literature

- Alexander Nym (Ed.): Iridescent Darkness: History, Development and Topics of the Gothic Scene. Plöttner Verlag, Leipzig 2010, ISBN 978-3-86211-006-3 .

- Roman Rutkowski: The charisma of the grave. Stereotype and prejudices in relation to youthful subcultures using the example of the black scene. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2004, ISBN 3-8334-1351-4 .

- Doris Schmidt, Heinz Janalik: Goths - youth culture in black. Schneider-Verlag, Baltmannsweiler 2000, ISBN 3-89676-342-3 .

- Andrea Schilz: Flyer of the black scene in Germany: visualizations, structures, mentalities. Waxmann, Münster a. a. 2010, ISBN 978-3-8309-2097-7 .

- Axel Schmidt, Klaus Neumann-Braun: The world of the Gothics. Scope of dark connotations of transcendence (= worlds of experience. Volume 9). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-531-14353-0 .

- Andreas Speit (Ed.): Aesthetic mobilization. Dark Wave, Neofolk and Industrial in the field of tension of right-wing ideologies (= series of anti-fascist texts. Volume 8). Unrast Verlag, Hamburg et al. 2002, ISBN 3-89771-804-9 .

- Frauke Stöber: Origin, content, values and goals of the black scene - the youth culture of the waver, goths and goths. Thesis . University of Essen, October 1999. (online version)

See also

- Black Music - On the variety of styles of music received by the black scene

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ecki Stieg: A scene without a name . In: Peter Matzke, Tobias Seeliger (eds.): Gothic! The scene in Germany from the point of view of its makers . Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-89602-332-2 , p. 15 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Alexander Nym: The Gothic scene does not exist . In: Alexander Nym (ed.): Shimmering darkness: history, development and topics of the Gothic scene . Plöttner Verlag, Leipzig 2010, ISBN 978-3-86211-006-3 , p. 13–15 , here p. 13 .

- ^ Black Scene, Berlin, A Critical Self-Presentation . In: Zillo music magazine . No. 1 , 1990, p. 25 .

- ^ The Cure in Leipzig . In: Glasnost Wave magazine . No. 23 September 1990, pp. 19 .

- ^ Roman Rutkowski: The charisma of the grave . Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2004, ISBN 3-8334-1351-4 , pp. 18 .

- ^ Markus Blaschke: Index. Black scene, accessed April 13, 2015 .

- ↑ Enrico Ahlig: Interview with Lacrimosa. Bild.de, accessed on April 13, 2015 .

- ↑ WGT in Leipzig Black scene sweats at 30 degrees. Focus.de, accessed on April 13, 2015 .

- ^ Andreas Behnke: Night plan. Nachtplan, Andreas Behnke, accessed on April 13, 2015 .

- ^ Gunnar Sauermann: Black Metal in the USA. Black America . In: Metal Hammer . August 2007, p. 87 .

- ^ Gunnar Sauermann: Lord Belial. Black dynamite . In: Metal Hammer . November 2008, p. 86 .

- ^ Roman Rutkowski: The charisma of the grave . Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2004, ISBN 3-8334-1351-4 , pp. 51 .

- ^ Roman Rutkowski: The charisma of the grave . Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2004, ISBN 3-8334-1351-4 , pp. 18 .

- ↑ Axel Schmidt, Klaus Neumann-Braun: Die Welt der Gothics. Scope of dark connotations of transcendence . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-531-14353-0 , pp. 96 .

- ↑ Axel Schmidt: Gothic . In: Ronald Hitzler, Arne Niederbacher (Hrsg.): Life in scenes . 3rd, completely revised edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-15743-6 , p. 61–70 , here p. 67 f .

- ^ Roman Rutkowski: The charisma of the grave . Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2004, ISBN 3-8334-1351-4 , pp. 42 .

- ^ A b Axel Schmidt: Gothic . In: Ronald Hitzler, Arne Niederbacher (Hrsg.): Life in scenes . 3rd, completely revised edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-15743-6 , p. 61–70 , here p. 63 f .

- ^ A b c Axel Schmidt: Gothic . In: Ronald Hitzler and Arne Niederbacher (eds.): Life in scenes . 3rd, completely revised edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-15743-6 , p. 61–70 , here p. 62 .

- ^ Peter Matzke: Gothic - Conservative cultural movement . In: Alexander Nym (Ed.): Schillerndes Dunkel. History, development and topics of the Gothic scene . 1st edition. Plöttner Verlag, Leipzig 2010, ISBN 978-3-86211-006-3 , p. 387-397 , here p. 395 .

- ^ Roman Rutkowski: The charisma of the grave . Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2004, ISBN 3-8334-1351-4 , pp. 62 f .

- ↑ a b c d e Black scene: Decal of society - in black. Sueddeutsche.de, accessed on October 6, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c d Alexander Nym: The Gothic scene doesn't exist . In: Alexander Nym (ed.): Shimmering darkness: history, development and topics of the Gothic scene . Plöttner Verlag, Leipzig 2010, ISBN 978-3-86211-006-3 , p. 13-15 .

- ↑ Doris Schmidt, Heinz Janalík: Raisins. Youth culture in black . Schneider, Baltmannsweiler 2000, ISBN 3-89676-342-3 , p. 40 .

- ^ Roman Rutkowski: The charisma of the grave . Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2004, ISBN 3-8334-1351-4 , pp. 63 f .

- ↑ Anders, Marcel: Alternative - how long will the new way? In: Uwe Deese, Peter Erik Hillenbach, Dominik Kaiser, Christian Michatsch (eds.): Jugend und Jugendmacher . 1996, ISBN 3-89623-050-6 , pp. 57 .

- ↑ a b c d Frauke Stöber: Origin, content, values and goals of the black scene - the youth culture of the wavers, goths and goths. Thesis. University of Essen, October 1999, accessed on March 28, 2015 .

- ^ A b c d Axel Schmidt, Klaus Neumann-Braun: Die Welt der Gothics. Scope of dark connotations of transcendence . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-531-14353-0 , pp. 172 f .

- ^ A b c Axel Schmidt: Gothic . In: Ronald Hitzler, Arne Niederbacher (Hrsg.): Life in scenes . 3rd, completely revised edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-15743-6 , p. 61–70 , here p. 63 .

- ↑ Axel Schmidt, Klaus Neumann-Braun: Die Welt der Gothics. Scope of dark connotations of transcendence . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-531-14353-0 , pp. 204 .

- ↑ Grit Grünewald, Nancy Leyda: The real existing vampire horror . In: Claudio Biedermann, Christian Stiegler (Ed.): Horror and Aesthetics . UVK-Verlags-Gesellschaft, Konstanz 2008, ISBN 978-3-86764-066-4 , p. 180 .

- ^ Roman Rutkowski: The charisma of the grave . Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2004, ISBN 3-8334-1351-4 , pp. 69 f .