Celts

As Celts ( Greek Κελτοί keltoi or Γαλάται Galatai , Latin Celtae or Galli ) is known since the antiquity of the ethnic groups Iron Age in Europe. Archaeological finds bear witness to a distinctive culture and highly developed social structure of these tribes.

etymology

According to the historians Herodotus and Diodorus , then Caesar and Strabons, the name of the Celts is probably a self-designation of the inhabitants of Central Gaul. The meaning of the name is in the dark. It is possible to derive from various Indo-European roots, including * ḱel- ' to hide', * kel- , to rise 'and * kelh₂- to' beat '. The last-mentioned root resulted in a protoceltic * kladiwos , from which perhaps the Latin gladius comes from.

The names "Gauls" and "Galatians", on the other hand, are derived from an Indo-European root * gal- " to be strong, to be (physically) able", which has been preserved in the island Celtic languages as gal "power, strength, bravery". In some cases, however, both names are seen as related and put to the root * gal- . The meaning of the ethnonym is given accordingly as "the mighty, sublime, strong" or as "the high, outstanding". In the case of the derivation of * ḱel- 'hide', a form * kltós is assumed, the meaning of which in this case would be 'hidden, descendants of the hidden God (the underworld)'. According to Caesar, the Gauls traced their origins back to an underworld god (" Dis Pater ").

Definition

The term Celts goes back to Greek traditions from Herodotus and other authors from the 6th and 5th centuries BC. BC, where tribes from the sources of the Danube to the hinterland of Massilia ( Marseille ) are called Keltoi . Greek and Roman writers each knew only a part of the tribes now regarded as Celtic. They transferred the term Celts to other tribes and peoples who they perceived as belonging together.

Depending on the subject area or point of view, the term Celts refers to either a Central and Western European language community ( linguistic definition), settlement communities with a similar material culture ( archaeological definition) or tribes with the same customs and beliefs ( ethnological definition). In addition, there is the notion that the Celts are the peoples regarded by the Greeks and Romans as Celtic.

The definitions of the various subject areas do not completely correspond to one another. The determination is made more difficult by the almost complete lack of written evidence of the cultures assumed to be Celtic from the time before the Romanization of their settlement areas. Knowledge of the early Celtic cultures is mainly gained through archaeological finds and individual general reports by Greek and Roman chroniclers.

Linguists see Celts primarily as speakers of Celtic languages . Birkhan postulates: “He who speaks Celtic is a Celt.” Likewise Rockel: “The Celts are therefore the speakers of one of the Celtic languages.” The Celtic languages form their own Indo-European language group.

Archeology sees cultural commonalities among the Celtic tribes from northern Spain to Bohemia during the Iron Age in Central Europe (8th – 1st century BC). The continuous development from the local Bronze Age predecessor cultures of Central Europe, in particular the Late Bronze Age Urnfield Culture , is proven beyond doubt today. The Celts are mainly associated with the Hallstatt culture and the Latène culture . The names of these cultures are derived from two sites, the cemetery of Hallstatt on Lake Hallstatt in Austria and the site of La Tène on Lake Neuchâtel in western Switzerland. In the middle of the 19th century, rich finds were made at both sites, which made a first chronology possible. Some authors use the term Celts only for the so-called classical Celtic epoch, which started around 650 BC. Begins.

It can be taken as certain that the Celts never formed a closed people or even a nation , at best one can speak of numerous different ethnic groups with a similar culture. They were related tribes who had cultural similarities and thus differed from the neighboring peoples, which is described, for example, by Romans such as Tacitus in Germania or Caesar in the Gallic War .

distribution

Archaeological determination

Archaeologically, the greatest expansion of the material Celtic culture reached from southeast England , France and northern Spain in the west to western Hungary , Slovenia and northern Croatia in the east; from Northern Italy in the south to the northern edge of the German low mountain range . There are also individual finds from the Latène period throughout the Balkans as far as Anatolia (settlement area of the Galatians in today's Turkey ). These finds are based on the 4th century BC. Attributed to the beginning of the Celtic migrations.

The inclusion of south-east England in the range of the archaeologically known as Celtic culture is controversial. The archaeological finds there from the middle and late Iron Age (approx. 600–30 BC) show regional and local peculiarities that distinguish them greatly from the continental finds at the same time. In northern Spain's Galicia also some Latène found fibulas , but can there not a closed Celtic culture horizon talk in terms of culture Latène be.

In the south of the Celtic region of Central Europe there was initially the Etruscan , in the east and south-east the Greek , Thracian and Scythian cultures. Large parts of these areas later became part of the Roman Empire and its culture. Germanic tribes resided north of the Celtic area of influence . The Celts maintained intensive cultural and economic relationships with all of the cultures mentioned.

Linguistic evidence

Celtic languages can be found from parts of the Iberian Peninsula to Ireland in the west, in the southeast to the northern Balkans, with a late branch in Anatolia. The northern border to the Teutons, for example in the area of the German low mountain range, has not been determined with certainty. South of the Alps, the Celtic area extends as far as the Po plain . The evidence for this linguistic interpretation is:

- The former largest area of distribution of Celtic tribes documented by ancient sources, for example the immigration of Celtic (and Thracian ) tribes to Anatolia, as attested by ancient Greek and Roman authors , cf. Paul's letter to the Galatians .

- Late antique evidence, according to which a dialect similar to the area around Trier was spoken in Anatolia .

- Little linguistic evidence of Celtic words in modern Central and Eastern European languages. These are reflected, for example, in the naming of individual tribes or areas as Gauls in France, Galicia in Spain and Galatians in Asia Minor; Borrowings in Basque like iskos 'fish'.

- Characteristic Celtic language elements in topographical names , for example place names in -briga and -durum with the changes made depending on the language area.

- Finds of stone inscriptions, potsherds graffiti, coin inscriptions and lead tablets in Celtiberian, Lepontic and Gallic languages from the 6th century BC. BC, either in its own script (for example the Lepontic alphabet from Lugano ) or in foreign scripts such as the Iberian, Etruscan or later the Latin script.

language

The Celtic languages are assigned to the western group of the Indo-European languages . An ancient Celtic language has not been handed down. Among the oldest language documents classified as Celtic are those in the Lepontic language from the 6th century BC. In addition to mostly short inscriptions made of non-perishable material (stone, lead), the Gaulish lunisolar calendar of Coligny has survived, which allows direct insights into non-material aspects of the Celtic culture of faith and everyday life. The Botorrita tablets from the 2nd and 1st centuries BC are noteworthy longer documents in Celtiberian and Iberian script . Chr.

The mainland Celtic languages are consistently extinct. On the Iberian Peninsula, Celtiberian was spoken, which, like Gallic and Lepontic, was lost in the course of Romanization. In Asia Minor, the poorly documented Galatian language was still to be found in antiquity.

Island Celtic languages are still used today in Wales ( Welsh or Cymrian) as well as in Ireland ( Irish , officially the first official language alongside English since 1922 ), in Scotland ( Scottish Gaelic in the Highlands and especially in the Hebrides ) and in Brittany ( Breton , brought to the continent by emigrants from the British Isles in the 5th century). The Manx on the Isle of Man died out in the 1970s, the Cornish in Cornwall in the 18th century. However, there have recently been efforts to make Manx and Cornish into lively colloquial languages again.

history

Hallstatt culture

The naming of the Celts and their localization coincides with the Iron Age late Hallstatt culture in Central Europe. This culture had been around since around 800/750 BC. Developed from the late Bronze Age urn field cultures in a region between Eastern France and Austria with its neighboring countries.

The Hallstatt culture reached from Slovenia via Austria, northwestern Hungary, southwestern Slovakia , the Czech Republic , southern Germany , Switzerland to eastern France. In 1959 Georg Kossack differentiated the entire area into an East and West Hallstatt district. The Westhallstatt district extended from eastern France, central and southern Germany via Switzerland to central Austria. The Osthallstattkreis comprised northern Austria, southern Moravia , southwest Slovakia, western Hungary, Croatia and Slovenia.

East and West Hallstatt district differed mainly in terms of the way of settlement and burial custom. In the West Hallstatt circle ruled large fortified hilltop settlements conducted by small, hamlet-like settlements were surrounded before. Small fortified manor houses dominated the Osthallstatt district. If in the west important personalities were buried with sword ( HaC ) or dagger ( HaD ), in the east they were given a battle ax with them in the grave. In the west there were rich chariot graves , while in the east the warrior was buried with his entire armament, including helmet and breastplate.

The late Hallstatt culture (HaD, around 650 to 475 BC) is famous for its richly decorated state or princely graves , which were found in southern Germany ( Hochdorf an der Enz ), near Villingen-Schwenningen ( Magdalenenberg ) and in Burgundy ( Vix ) as well as for tank graves (men's graves with full weapons) from Eastern Bavaria to Slovenia.

Numerous finds have proven contacts between the Hallstatt period elites and southern European antiquity. The origin of the imported goods reached from the western Mediterranean to Iran. Greek and Etruscan imported goods were particularly popular.

Striking features of the Hallstatt culture are fortified hilltop settlements that were found from eastern France to the east - above all in Switzerland and parts of southern Germany. The Mont Lassois near Vix in France and the Heuneburg near Hundersingen on the Danube in Baden-Württemberg are particularly well-known because they have been well researched . As the height fortifications often had Greek imports and so-called princely graves were often located in their vicinity, they are also referred to in research as princely seats. However, recent investigations in the run-up to the Heuneburg and in Hochdorf also uncovered unfortified flat settlements in which corresponding imports were found. This means that there is now also a resident upper class in flat settlements.

There is evidence of close trading relationships with the Greek cultural area, in particular with the colony of Massilia / Marseille , whereby the Hallstatt period population in what is now eastern France, along the Rhône and Saône , probably assumed a key position in the development of the Central European Hallstatt culture.

In the second half of the 6th century, the societies on the northern and western fringes of Hallstatt culture increasingly came under their influence, took over part of their customs and were integrated into the Hallstatt network of relationships, with the Hunsrück - Eifel and the Champagne - Marne regions in the west and the area around the Dürrnberg ( Hallein ) in Austria played a special role in this development.

Latène culture

The Hallstatt culture is followed by the Latène culture (from approx. 480 BC to 40/41 BC, depending on the region), whose artistic styles are influenced by Mediterranean and Eastern European models (Etruscan, Greek and Scythian influences). The Latène period represents the last blooming period of the Celtic culture.

The Latène culture itself can be roughly divided into three phases, which - depending on the region - can be clearly understood in different ways and whose temporal approach can vary regionally by around one to two generations:

- Early La Tène (around 480 or 450 to 300 BC)

- Middle Latène (around 300 to 150 BC)

- Late Latène (around 150 until after 50 BC or regionally until the turn of the century)

Spring atène - the horizon of the grand tombs

In the Early La Tène the flower of the material culture of the Hallstatt period continues, however, to move the cultural centers of different reasons from southern Germany to the north, west and east. In addition to armed conflicts, for which there is no reliable evidence, environmental problems in the vicinity of the Hallstatt period hilltop settlements are mentioned. Another theory assumes that the Etruscans - in competition with the Greek colonies in southern France - opened up alternative trade routes to the north and towards the Atlantic and thereby contributed to an economic upswing in the wider Middle Rhine and Champagne - Marne region. The new wealth would then have found its expression in the graves for a few generations. An indication of an increased influence from the Mediterranean area could also be the drastic change in style from the more geometric-abstract style of the Hallstatt period to the more naturalistic-figurative style of the early La Tène period.

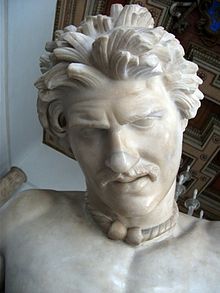

From the regions of Champagne-Marne, Hunsrück, Eifel and Dürrnberg, numerous so-called ceremonial graves are known for the springtime La Tène. To the east of it, there are richly furnished burials and large fortified settlements from the early La Tène period in Franconia and Bohemia. The burials of high-ranking people from this period show rich grave goods, which are characterized above all by carriages decorated in the Laten style , jewelry (often gold), weapons and imports from the Mediterranean region. The custom of marking burial mounds or grave districts with stones or steles, which has been known since the Hallstatt period, developed into finely crafted statues with human features in rare individual cases (on the Glauberg ). The statues from Glauberg show details ( mistletoe leaf crown and dagger ) that exactly match the grave goods of the buried. The statues can therefore be viewed as an attempt to depict the deceased, the function of which may have gone far beyond the mere marking of the burial site. These statues could be modeled on Greco-Etruscan tombs.

In addition, numerous graves from other social classes as well as isolated smaller settlements were excavated, especially in the spring-Latène centers mentioned, but also beyond. Gold and fine forging as well as stone carvings, but also the few surviving wooden sculptures (Fellbach-Schmiden) in the Latène style testify to high technical and artistic skill. Well-researched examples of grand tombs from the early La Tène period are the graves of Glauberg , Waldalgesheim and Reinheim .

While the custom of richly furnished ceremonial tombs flourished on the western and northern fringes of the Celtic cultural area, the Celtic migrations began further south and east. Although the time of the Celtic migrations is usually equated with the Middle La Tène period, the first migrations began earlier. Regional differences are likely to become apparent here.

Middle Latène and Celtic walks

The first stays of Celtic immigrants in what was then mainly Etruscan northern Italy began in the 6th century BC. Demonstrable. During the from the 5th century BC. The Celtic culture is also palpable in northern Spain and Portugal when the waves of migration began, although no displacement of local cultures can be demonstrated here. A gradual adoption of Central European cultural elements by the resident societies is far more likely. The people of the late Iron Age living in northern Spain and Portugal are therefore also known as the Celtiberians . Celtic groups also settled in northern Italy and the Po Valley, from where they settled at the beginning of the 4th century BC. Attacked Rome . The siege of Rome under the Celtic military leader Brennus (probably 387/386 BC) left the later world power with a long-lasting trauma.

Other tribes penetrated through south-eastern Europe and the Balkans to Greece and Asia Minor. 279 BC Celtic groups under the leadership of a military leader also called Brennus (Brennus is therefore seen more as a title than a name) advanced to Delphi , but were ultimately repulsed. A part of the tribe finally settled in Central Anatolia and was mentioned centuries later in the New Testament under the name Galatians .

At the same time, parts of the tribes remained settled in their ancestral regions in Central Europe. This is indicated by the archaeological finds, albeit much rarer compared to the previous early and subsequent late La Tène periods. The density of finds varies greatly depending on the region. While the Middle La Tène period can be clearly identified in some regions, there are largely no finds in other regions. According to the current state of research, there is likely to be a significant decline in settlements during the Middle Latène period, especially in southern Germany and the northern Alpine region.

Not only the number, but also the type of finds differ greatly from those of the early La Tène period: royal tombs and large fortified hilltop settlements have almost completely disappeared. In their place are comparatively simple, almost poorly equipped graves and smaller, less structured settlements. In regions where there are graves, there is still evidence of a local or regional upper class, who now only gets inconspicuous parts of their property into the graves ( pars-pro-toto custom).

Towards the end of the Middle Latène period, Celtic populations began to migrate back to the regions north of the Alps. The probable cause for this are the devastating victories of the Romans advancing to the Alps over various Celtic tribes in northern Italy. Some researchers assume that the subsequent culture of the late Latene period was decisively influenced by Celtic migrants from northern Italy. They had lived in northern Italy for several generations and there came into contact with the highly developed urban culture of the late Etruscans, Greek influences and the early Roman culture that was newly formed on this basis. At the same time, since the late Middle Latène period, Celtic influences on Roman culture, such as in the field of weapon technology and car making, can be proven.

Late Latène - Oppida Culture

From the second half of the 3rd century BC. Starting from the east and south, large fortified settlements, so-called oppida, were founded again in the area of the Alpine foothills up to the northern edge of the German low mountain range . The name Oppida goes back to Roman descriptions, for example by Julius Caesar, and is mostly only applied to settlements from the late Latene period. Similar to the large fortified settlements of the late Hallstatt and early La Tène periods, these oppida have city-like structures and, in individual cases, could reach considerable numbers of inhabitants (5,000 to 10,000 inhabitants). Examples of these settlements include the Staffelberg ( Menosgada ) in Upper Franconia, the oppidum from Manching in Upper Bavaria, the oppidum Finsterlohr near Creglingen , the Heidetränk oppidum in the Taunus, the ring wall on the Dünsberg near Gießen, the ring wall from Otzenhausen near Nonnweiler, the Heidenmauer near Bad Dürkheim, the Donnersberg in the Northern Palatinate and others apply. The Celtic oppida culture experienced from the end of the 2nd to the late 1st century BC. Its heyday, whereby it reached the stage of high culture due to its social and economic differentiation, highly developed craftsmanship and artistry as well as long-distance trade . Only the lack of general written form contradicts this designation. On the basis of ancient descriptions in Roman and Greek sources, however, one can assume a highly developed cultural technique of the exact transmission of oral knowledge in the area of the Celtic tribes. Probably for cultic reasons, the Celts seem to have deliberately avoided written records as far as possible. Findings from the late La Tène period indicate that the Celtic upper class was increasingly literate.

The Celtic tribes reached their greatest extent around 200 BC. In the northwest of their settlement areas, d. H. in the broadest sense in the area of the northern, right bank of the Rhine, the Celtic culture gradually disappeared during the 1st century BC. BC probably as a result of the advance of Germanic tribes to the south.

Celts and Romans - Gallo-Roman and Noric-Pannonian culture

The situation in the Roman sphere of influence is completely different. After the conquest of the northern foothills of the Alps and Gaul by the Romans under Caesar (in Gaul) and under Augustus (in Raetia), large parts of the Celtic culture initially lived in Gaul , to which today's Saarland and the areas on the left bank of Rhineland-Palatinate belonged, and south of the Danube in the now Roman provinces of Raetia , Noricum and Pannonia, as well as in a transition zone between Roman and Germanic areas of influence, which stretched from the Taunus and the lower Lahn through northern Hesse to northern Bavaria . In the areas conquered by the Romans, after the turn of the ages, with increasing Romanization, Celtic and Roman cultural elements merged into the relatively independent Gallo-Roman culture in the west and the Noric-Pannonian culture in the east. Individual elements of the Celtic culture lived there until late antiquity.

The end of the Gallo-Roman and Norico-Pannonian cultures

With the onset of incursions by Germanic tribes into the northern Alpine provinces of the Roman Empire from the beginning of the 3rd century AD, Germanic influences east of the Rhine and south of the Danube increasingly displace the Gallo-Roman and Noric-Pannonian cultures. The subsequent extensive transfer of the defense of the northern border of the empire to Germanic mercenaries, the gradual evacuation of the Noric-Pannonian population towards Italy and Byzantium and the increasing spread of Germanic tribes to Italy, Spain and beyond the borders of the Eastern Roman Empire are still going on At the end of the Western Roman Empire in AD 476, the Noric-Pannonian culture largely emerged in the culture of the Germanic tribes advancing from the north. In the area of the province of Pannonia , the last remnants of the Noric-Pannonian culture can be preserved for a few years, but disappear at the latest at the beginning of the 5th century with the final capture of the Roman province of Pannonia by the Huns .

On the left bank of the Rhine, the first raids by Germanic groups took place in the middle of the 3rd century AD . After the Limes was abandoned around 260 and the border was moved to the Rhine, the provinces were relatively stabilized despite repeated Germanic raids and held until the end of the Western Roman Empire. In the first half of the 4th century, the provinces on the left bank of the Rhine, and thus the Gallo-Roman culture, experienced a final boom and stability with the establishment of Triers as an imperial city. A population decline in the countryside is likely, but the Gallo-Roman population remained in the fortified places south of a line between Cologne and Boulogne-sur-Mer .

From the 3rd century onwards, Frankish groups had been settled north of this line , the heads of which gradually assumed leadership positions in the late Roman army. This was followed by immigration of Frankish families into the Gallo-Roman areas, now called Romanesque, which probably formed more and more of the upper class, but only overlaid the local population, not displacing them. After the end of the Western Roman Empire, the Frankish kings, who saw themselves as the successors of the Roman Empire, were able to fall back on the local and regional administrative structures supported by Gallo-Romans (Romanes) on the Rhine and in Gaul, some of which still functioned. In the west, the Franconian new settlers were gradually Romanized, while in the east as far as the Rhine the Romanesque, originally Gallo-Roman population was increasingly Germanized in the following two centuries, i.e. the customs and language of the Franks who had moved there increasingly took over. Christianity, introduced in Roman times, survived the cultural change in most of the regions south of the line mentioned above. The last remnants of Gallo-Roman culture persisted in the Moselle region through special linguistic forms and customs until the High Middle Ages.

Between the Middle Rhine and the Alps, numerous place, terrain and water body names go back to Celtic names and testify to a certain degree of the adoption of Celtic cultural and linguistic elements by the newly formed population groups during and after the migration period . However, no continuity of a Celtic population in these regions can be derived from this.

Notes on the ancient sources

Texts

The Celts probably deliberately avoided recording social, religious or tradition-related content in writing and also on permanent material. Oral distribution of content seems to have been a priority. The high skills of the Celts in the art of handing down content orally, as well as the latent hostility to writing of the Celts, are documented by several ancient authors, including Caesar.

In addition to the short texts that have survived, there is also archaeological evidence of writing implements from the Oppida, especially from the late La Tène period . At least for the Celtic upper class , a certain amount of written language - especially in economic matters - and foreign language skills must be assumed. In addition to Gaulish, Celtiberian and Lepontic scripts, Iberian, Etruscan and Latin script were also used for writing.

The Celts in Noricum had their own script, similar to the Etruscan , written from right to left, of which discoveries were made in the Magdalensberg excavation site in particular . But even before the Roman occupation (15 BC), Latin was predominantly in use there in language and writing.

From the 4th to the 7th centuries, the Ogham script was also documented on Irish gravestones and boundary stones on the British Isles .

Due to the lack of own written documents, the knowledge about the Celts is based on sometimes very problematic sources of the historiography of their Mediterranean neighbors ( ancient Greece , Roman Empire ) as well as on archaeological finds.

archeology

Numerous archaeological finds in Central Europe convey a vivid picture of the culture of the ancient Celts. The older information about the culture and trade relations of the Celts comes from the extremely richly furnished barrows of the late Hallstatt and early Latène periods . These so-called splendid or princely graves are burial sites for the dead in high society and usually contain rich grave goods. Often the dead were buried lying on wagons, the remains of which we owe most of today's knowledge about the high level of Celtic wagon construction. In addition, burials on bronze Klinen (Hochdorf), a kind of sofa, are known. In addition to men's burials, there were richly furnished princely graves of women, especially in the late Hallstatt and early La Tène periods. In addition, numerous other finds from less well-equipped hill or flat burial grounds and smaller settlements are known.

On Glauberg near Glauburg in Hesse on the eastern edge of the Wetterau was built in the 5th century BC. A nationally important center of the Celts. There seems to be evidence of a Celtic calendar structure that is unique in Europe.

The Celtic culture culminated in the so-called Oppida , large, fortified (high) settlements in the entire Celtic area, which appear to be particularly “typical” . In southern Germany, the Viereckschanzen can still often be seen in the terrain as ground monuments of the time. According to the current state of research, the latter probably had several functions (religion / cult, fortification, enclosure for farmsteads, etc.), but were primarily enclosed farmsteads.

society

The insights that ancient authors give into the structure of Celtic society are rather poor.

From the royal tombs of the late Hallstatt period and from Julius Caesar 's De Bello Gallico (From the Gallic War) , at least for the West Hallstatt district, it can be concluded that society was divided into local and regional units with a more or less structured hierarchy. At the top of the society were outstanding personalities, so-called princes , who probably ordered and controlled large building projects. In addition, these princes maintained extensive contacts with other princes and controlled long-distance trade. Genetic analyzes and ancient sources from the late La Tène period show that, at least in some tribes such as the Haeduern in eastern France, offices and leadership positions were not inherited, but were given through elections.

Extensive relationships are documented for both the late Hallstatt period and the Latène period, and loose, far-reaching political structures are documented for the late Latène period by ancient authors. However, at no time did they form the basis for a common consciousness as an ethnic group or a permanent, coherent political entity.

Druids

Several spiritual and spiritual leaders who came from the upper classes of society are documented by authors from late antiquity. These people are known as druids. According to ancient authors, they formed the Celtic priesthood. In order not to confuse historical Druidism with modern Druidism , Caesar's original text should be used here. He wrote: “The druids are responsible for the affairs of the cult, they direct the public and private sacrifices and interpret the religious precepts. A large number of young men gather with them for lessons, and they are held in great honor by the Gauls . ”According to Caesar, cult and religious considerations played an important role among the Gauls.

The Druids formed an intellectually and religiously highly educated upper class of the Celtic social system. From ancient sources and traditional myths of Celtic origin, the Druids also have a position of power over the princes, who mostly come from the same upper class.

The training to become a druid took an extremely long time, according to Caesar sometimes up to twenty years: “As a rule, the druids do not take part in the war and neither do they pay taxes like the rest of the world […] These great benefits induce many to take advantage of their own free will Initiate teaching, or their parents and relatives send them to the druids. They are said to have memorized a large number of verses there. Therefore some stay in class for 20 years. "

In addition to their priestly functions, the druids also had secular duties and privileges. They were responsible for the role of teacher, physician, natural scientist and judge. According to Caesar, excommunication , i.e. exclusion from sacrificial customs, was the most severe of the possible punishments. The druids are known for their justice , Strabo boasted .

In later times there are also said to have been female druids . Information about this comes mostly from Roman and late medieval sources.

The role of the woman

Although women were held in high esteem and - albeit rarely - were able to occupy leadership positions, Celtic society as a whole was organized in a patriarchal manner. The most famous Celts named by ancient authors were Boudicca , leader of the Iceni (Britain, Norfolk ), who led the revolt against the Roman occupation in AD 60/61, and Cartimandua , "queen" of the brigands , who lived in AD 77 Were defeated by Agricola .

religion

There is hardly any ancient evidence of the beliefs of the Celts. Moreover, according to the usual Interpretatio Romana , ancient authors compared the Celtic gods and cults with their own Roman ones and assigned Roman interpretations and god names to the Celtic gods depending on their jurisdiction. Thus, statements about the original function, myth and cult of the Celtic world of gods are difficult. Examples of equations: Teutates was placed equal to Mercurius , Cernunnos to Jupiter , Grannus to Apollo and Lenus to Mars .

Due to the different religious ideas in different regions (both among Romans and Celts), these reinterpretations could have several Roman "godfather gods" with the same model, whereby the same Roman gods appear in different regions with different Celtic surnames, but also the same Celtic gods were assigned to different Roman ones.

Agriculture and Food

The Celtic economy was based on agriculture and animal husbandry . Grains ( emmer , spelled , barley , millet ) and legumes ( broad beans , peas , lentils ) were grown on small, fenced-in fields . The vegetables that were consumed included dandelions , nettles , turnips , radishes , celery , onions and cabbage . Archaeological finds (leftovers) in Hallstatt indicate that the Celts ate a dish that is still common in Austria today, Ritschert , a stew made from pearl barley and beans .

The Latin word for beer ( cervisia ) is a Celtic loan word . Cervisia was a wheat beer with honey for the more affluent population among the Celts . Korma or Curma was a simple barley beer. The upper class also drank imported wine. In Hochdorf and the Glauberg, mead was archaeologically proven by pollen finds .

The most important domestic animal was the cattle , which in addition to the delivery of meat, milk ( cheese ) and leather was also indispensable for the cultivation of the fields. Besides were sheep ( wool ) and pigs kept; Dogs were used as herding dogs and hunting dogs . Horses were a status symbol and important on military campaigns and were probably bred more intensively by some tribes.

technology

Mining was also important to the Celtic economy . Mining on salt is clearly proven. Iron extraction and smelting is to be assumed. Due to later mining activities, however, the last evidence of Iron Age ore mining is usually missing from the mining areas.

The Celts were pioneers in the further development of the car . They invented turntable steering and suspension . In metallurgy , too , they were initially superior to the Romans; Ferrum noricum in particular was a widely coveted material. Presumably they inherited various skills in these fields from the Etruscans and Scythians. For a long time, imports of weapons, especially swords from Celtic production, were an integral part of the armament of Roman troops. In addition, the Romans not only adopted technical details in car construction, but presumably also individual terms of car construction from them. In addition, the invention of wooden barrels composed of staves is associated with the Celts.

trade

Grave finds prove the extensive trade of the Celts with all peoples of ancient Europe . Exported iron , tin , salt , wood , flax , wool , weapons, tools, floats , textiles , shoes . Mainly glass , wine and other luxury goods were imported from the Mediterranean and the Middle East .

The Celtic tribes on the continent took over the monetary system from the Greeks and Romans , but began to shape them from the end of the 3rd century BC. Chr. Own gold coins. The early gold coins probably only served to exchange information at first. At the latest at the beginning of the 1st century BC. At least the western (Gallic) oppida culture had switched to the three-metal currency: in addition to gold pieces, silver and potin coins were also minted. Silver coins seem to have been used for supra-regional exchange, while potin coins were used as small change for local and regional trade.

Settlements

From the end of the 3rd century BC onwards, the main trade routes were built. Fortified urban settlements, so-called oppida . Through decades of excavations in several countries, some oppida are now well researched. These include:

- Germany: Dünsberg , Heidenmauer (Bad Dürkheim) Pfalz, the Altburg (castle) near Bundenbach Donnersberg North-Palatinate, Altkönig and heather drink with gold mine and Altenhöfe in the Taunus, Ipf , Manching , Martberg , Finsterlohr , Wallendorf (Eifel) , Heiligenberg (Heidelberg) , Steinsburg , Staffelberg , Ehrenbürg , Heuneburg , Altenburg-Rheinau , Kelheim , Dornburg , Eintürnen , Heidengraben near Grabenstetten , the ring wall of Otzenhausen, North Saarland, Tarodunum in the Dreisamtal near Freiburg, Oppidum Milseburg in the Rhön, near Vaihingen / Enz ( Celtic prince of Hochdorf ).

- Austria: Roseldorf (municipality of Sitzendorf) , castle in Schwarzenbach , Mitterkirchen .

- Czech Republic: Stradonice , Zavist .

- Switzerland: Bern-Enge , Basel-Münsterhügel , Oppidum von Bas-Vully , Altenburg-Rheinau , Oppidum Lindenhof , Oppidum Eppenberg , Oppidum Uetliberg , Aventicum , Oppidum Mont Terri , Vicus Petinesca and Vindonissa .

- Luxembourg: Titelberg .

- France: Bibracte , Alesia , Oppidum d'Ensérune , Gergovia

In some of these oppida, excavations continue. Results from smaller excavation campaigns are available from numerous other sites of this type. However, the popular image of a Celtic oppidum is largely shaped by the results in the Czech Republic, Manching and Bibracte.

Arts and Culture

Visual arts

As unreservedly Celtic, i.e. H. attributed to the historically documented Celts, the artistic styles of the Latène period apply, the research of which is particularly associated with the names of the two archaeologists Paul Jacobsthal and Otto-Herman Frey . The art styles developed from the beginning of the 5th century BC. From Mediterranean models, which were interpreted relatively freely by the Celtic artists, dismantled and synthesized into their very own form and art expression. An influence of the Cimmerians and Scythians could have existed. The clearest models, however, can be found in the orientalizing art of the Greeks and Etruscans, who for their part seem to have had models in the Orient, as in Iran.

literature

The literature and mythology of the Iron Age Celts is unknown. Occasionally - only rarely from the archaeological point of view - the thesis is put forward that remnants of mainland Celtic traditions could have entered the British narratives of the early and high Middle Ages , including perhaps parts of the Arthurian legend , which, however, probably did not have its core until late antique, early Christian times when the fringes of the Roman Empire began to move.

Myths of the island celts have been passed down in different cycles: the Finn cycle , which is about the Irish hero Fionn mac Cumhaill , the Ulster cycle , primarily the story of two fighting bulls, the four branches of the Mabinogi , which represent Pryderi's life story, and the mythological cycle .

music

The fact that the Celts made music is proven by texts by Greek writers; However, style, harmony and sound have been lost. The appearance of the carnyx , a trumpet-like instrument, is known from archaeological finds and depictions on Roman reliefs . Various Celtic coins depict string instruments that are similar to the ancient Greek instruments lyra and kithara . The statue of a man with such a stringed instrument in his hands was found in 1988 during excavations in the Celtic fortress of Paule-Saint-Symphorien in Brittany.

The music now called " Celtic " was not written down until the 17th century. It is the traditional music of Ireland, Scotland and Brittany, but also of emigrants from these areas such as Cape Breton (Canada). However, whether these are remnants of the music of the historical Celts must be highly doubted.

Celtic tribes

Several Celtic tribal names and their approximate settlement areas have come down from various ancient sources. The most important ancient sources of Celtic tribal names are the descriptions of Celtic tribes in Julius Caesar's De bello gallico (Gallic War). An exact localization of the tribes and delimitation of the ancient settlement area of the Celts is, however, mostly insufficient due to the often confusing location information and mostly completely inadequate knowledge ancient authors from the Mediterranean region. The separation carried out by Caesar into Teutons east of the Rhine and Celts or Gauls west of the Rhine has proven completely inaccurate on the basis of archaeological findings. Numerous allegedly Celtic tribal names mentioned in the literature, which were reconstructed with "Celtic" words based on alleged name components in place and river names, are however inventions of the 19th century, when a true "Gallomania" broke out, especially in France, and every city suddenly wanted to go back to the foundation by a Celtic tribe.

The Gallic tribes collectively under Gauls out, settled the present-day France, parts of Switzerland, Luxembourg, southeastern Belgium, Saarland and parts of the left bank of Rhineland-Palatinate 'and parts of Hesse (Region of Central Hesse ). The northern tribes at Caesar are called Belger, whereby areas in today's Belgium and in the Eifel (the Leuker ) are particularly suitable .

In present-day France and in the bordering areas of Belgium and Germany, Caesar mentioned: the Allobroger ( Savoy and Dauphiné ), the Ambian (near Amiens ), the Arverni ( Auvergne ), the Bituriger (near Bourges ), the Cenomaniac (Seine-Loire) Region, as well as partly in Northern Italy), the Eburonen (Lower Rhine), the Häduer (Bourgogne, around Autun and Mont Beuvray ( Bibracte )), the Mediomatriker (region around Metz , parts of the Saarland), the Menapier , the Morin , the Parisian ( Central Britain and Gaul / Paris? ), The Senones (near Sens, as well as in northern Italy), the Sequaner , the Remer , the Treverer (in the Moselle region , from the Maas via Trier to the Rhine), the Venetians (on the Loire - Estuary), the Viromanduer (near Vermandois ), the Santonen in today's Saintonge around the city of Saintes , and a number of other tribes.

In Bavaria, Baden, Württemberg and is now Switzerland, the group who found Helvetier , with the districts of Tigurini and Toygener also the root of, Vindeliker (now Upper Bavaria, Bavarian Swabia Augsburg : Main place of Vindeliker = Augusta Vindelicorum as a Roman city) Upper Swabia and around Manching (Upper Bavaria) as well as the Boier in Bohemia, Upper and Lower Bavaria, the Noriker in Austria and in Upper Bavaria, south of the Inn, and the Likater around the Lech in Upper Bavaria and Swabia.

In the south of the Gallic area, in northern Italy, sat the Insubrians , in the north the Nervi and Belger , some of whom were also to be found in Britain. In northern Spain who lived Gallicier and the Asturians , in what is now Portugal the Lusitanian . The Celts settled in the Balkans are summarized as Danube Celts . The Galatians penetrated as far as Asia and settled in what is now Turkey .

reception

Reception history

In 1760 a critic from Edinburgh , Hugh Blair , published "Fragments of Ancient Poetry" ("Fragments of ancient poetry, collected in the Scottish Highlands , translated from Gaelic or Ersian"). Blair had asked a tutor named James Macpherson to collect "ancient Gaelic chants of home". Since Macpershon did not know where to find them, he wrote them himself, claiming to have translated them from Gaelic into English.

Blair was enthusiastic and suspected that the alleged chants from Celtic prehistoric times were fragments of a national epic that has not yet been shown in Scotland . As the author of the work, Blair “identified” Ossian, who is known from Scottish Gaelic mythology (details there), and his hero must be the legendary King Fingal (Fionn). At Blair's urging, Macpherson delivered the epic poems "Fingal" and "Temora", which were published in 1762 and 1763, respectively.

In the same year, Samuel Johnson described these seals as "not authentic and [...] poetically without value". In 1764 the “ Journal des sçavans ” in Paris also expressed serious doubts. In a public dispute, Johnson accused Macpherson of imposture and asked him to produce original manuscripts. The public took little notice of this controversy; rather, the chants were eagerly received. In 1765 they were brought out in a summarized form, meanwhile completed to “Works of Ossian” (“Ossian's Chants”). Many readers of the pre- romantic era liked the dark and the prehistoric (see Schauerroman ) and believed willingly in the rediscovery of a national epic.

politics

The appeal to the Celts in France (especially in the 19th century, see among other things the figure of Vercingetorix ), but also in Ireland , Wales, Scotland and Brittany shows how attempts are being made in modern times to see the past as traditional and to use to create identity for modern nations. The historical reality is often extremely falsified.

Postage stamps

The German special stamp Keltenfürst vom Glauberg (144 cents, circulation: 17 million, graphic designer: Werner Schmidt, Frankfurt am Main) from the series Archeology in Germany was presented on January 7, 2005.

Two postage stamps with Celtic exhibits were issued as part of an archaeological series in 1976. The motifs were the gold-decorated bowl from the princely grave of Schwarzenbach and the silver neck ring from Epfendorf -Trichtingen.

Comics: Asterix and Obelix

The Asterix comic stories are mostly about the conflict between the Gauls and the Romans. Historical facts are not described, rather memories from Latin and history classes - first and foremost Caesar's De bello Gallico and the Gauls ' struggle for freedom under the leadership of Vercingetorix - as well as (pseudo) historical legends and clichés - such as those of Celtic bards and Druids - merely points of contact for fictional adventures with “comical” intentions, with everyday ( situation comedy , slapstick ) as well as with current or historical objects that are caricatured . The mythical-Celtic motif is always expressed in the village druid Miraculix , who uses a magic potion to give his tribesmen superhuman strength for the duration of a fight (a caricature of Superman ), and the last picture of each episode shows a feast in the last free Gallic village Honor of his heroes Asterix and Obelix , where you protect yourself from the "art" of the village bard Troubadix by tying and gagging him. Portraits of Vercingetorix as the “original French national hero” or a Roman denarius from 48 BC. BC, which shows a Gaul, probably Vercingetorix, are the template for the hair and beard of the "funny" Gauls.

Museums and exhibitions

- Important museums and open-air exhibition venues include the Celtic Museum in Hallein , the Celtic Museum in Hallstatt , the Celtic World on Glauberg , the Celtic World in Uttendorf in Pinzgau, the Celtic Museum in Hochdorf , the Celtic-Roman Museum in Manching, the KeltenKeller Museum in Biebertal- Rodheim and the Steinsburg Museum in Römhild , the Celtic village Mitterkirchen and the Keltenerlebnisweg (a long-distance hiking trail in Thuringia and Bavaria ).

- The Frög cemetery is an archaeological site with constantly changing special exhibitions.

See also

- Celtic head cult

- Celtic south walks

- Celtic warfare

- Celtomania

- List of Celtic gods and legendary figures

- List of island celtic myths and legends

literature

- Dorothee Ade, Andreas Willmy: The Celts. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2115-2 .

- Jörg Biel , Sabine Rieckhoff (ed.): The Celts in Germany. Theiss, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1367-4 .

- Helmut Birkhan : Celts. Attempt at a complete representation of their culture. 2nd Edition. Böhlau, Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-7001-2609-3 .

- Helmut Birkhan: Post-ancient Celtic reception. Praesens-Verlag, Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-7069-0541-1 .

- Helmut Birkhan: Celtic religion. In: Johann Figl (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Religionswissenschaft. Religions and their central themes. Tyrolia / V & R, Innsbruck / Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-7022-2508-0 (Tyrolia), ISBN 3-525-50165-X (V&R).

- Jean-Jacques-Henri Boudet: The True Language of the Celts and the Kromleck of Rennes-les-Bains. German translation and editor Olaf Jacobskötter, Waldkraiburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-00-021219-2 .

- Olivier Büchsenschütz, Thomas Grünewald , Bernhard Maier , Karl Horst Schmidt : Celts. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 16, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2000, ISBN 3-11-016782-4 , pp. 364-392.

- Jean-Louis Brunaux: Les religions gauloises. Errance, Paris 2000 (= Nouvelles approches sur les rituels celtiques de la Gaule indépendante).

- Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier (Hrsg.): Hundred masterpieces of Celtic art. Trier 1992, ISBN 3-923319-20-7 .

- Barry Cunliffe : The Celts and Their History. 8th edition. Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 2004, ISBN 3-7857-0506-9 .

- Hermann Dannheimer, Rupert Gebhard: The Celtic Millennium. Mainz 1993, ISBN 3-8053-1514-7 (partly outdated).

- Alexander Demandt : The Celts. 8th, revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-44798-3 , ( Beck Wissen 2101 ).

- Myles Dillon, Nora Kershaw Chadwick : The Celts. From the prehistory to the Norman invasion. Zurich 1966.

- Otto-Herman Frey : Celtic large sculpture. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 16, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2000, ISBN 3-11-016782-4 , pp. 395-407.

- Janine Fries-Knoblach: The Celts. 3000 years of European culture and history. Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-17-015921-6 .

- Alfred Haffner (Ed.): Sanctuaries and sacrificial cults of the Celts. Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-933203-37-6 .

- Martin Kuckenburg: The Celts. Theiss, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-8062-2274-6 .

- Johannes Lehmann : Teutates & Co. Journey to the Celts in southwest Germany. Tübingen 2006, ISBN 978-3-87407-693-7 .

- Bernhard Maier : History and Culture of the Celts . CH Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-64140-4 .

- Bernhard Maier : The Celts. History, culture and language . A. Francke Verlag, Tübingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-8252-4354-8 .

- Bernhard Maier : The Celts. Your story from the beginning to the present. 3rd, completely revised and expanded edition. CH Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-69752-4 .

- Bernhard Maier : The religion of the Celts. Gods, myths, worldview. CH Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-48234-1 .

- Bernhard Maier: Celtic religion. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 16, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2000, ISBN 3-11-016782-4 , pp. 413-420.

- Ranko Matasović: Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic . Brill, Leiden 2009.

- Wolfgang Meid : The Celts. 2nd, improved edition. Reclam, Stuttgart 2011.

- Felix Müller (Ed.): Art of the Celts. 700 BC Chr. - 700 AD. Verlag NZZ Libro, Bern 2009, ISBN 3-7630-2539-1 .

- Albin Paulus: Celts. In: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon . Online edition, Vienna 2002 ff., ISBN 3-7001-3077-5 ; Print edition: Volume 2, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-7001-3044-9 .

- Astrid Petersmann: The Celts. An introduction to Celtology from an archaeological-historical, linguistic and religious-historical perspective. Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-8253-6451-9

- Heinzgerd Rickert: Introduction to the history and culture of the Celtic peoples. Bochum 2006, ISBN 978-3-89966-190-3 .

- Anne Ross: Pagan Celtic Britain. London 1974, ISBN 0-351-18051-6 .

- Martin Schönfelder (Ed.): Celts! Celts? Celtic traces in Italy. (= Mosaic stones. Volume 7.) Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-88467-152-8 .

- Markus Schußmann: The Celts in Bavaria. Archeology and history. Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2019, ISBN 9783791730936 .

- Konrad Spindler : The early Celts. 3. Edition. Reclam, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-15-010323-1 (partly outdated).

- Patrizia de Bernardo stamp: Celtic place names. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 16, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2000, ISBN 3-11-016782-4 , pp. 407-413.

- Reinhard Wolters : Celtoskyths. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 16, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2000, ISBN 3-11-016782-4 , pp. 420-422.

- Stefan Zimmer (Ed.): The Celts - Myth and Reality. Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, 3rd updated and expanded edition 2012, ISBN 978-3-8062-2693-5 .

- Der Spiegel (magazine): The Celts - princes, druids, Gallic warriors - Europe's puzzling barbarians , history issue 5/2017, Spiegel-Verlag, Hamburg 2017

Web links

- The Celts on Antikefan.de

- Gilbert Kaenel : Celts. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- archaeologie-online.de (link to numerous archaeological and linguistic articles on the subject of "Celts")

- The Helvetier, Rauracher and Bojer three Celtic-Indo-European tribes in Switzerland

- Early centralization and urbanization processes

- Celtic Hessen

- kelten-info-bank.de

Individual evidence

- ^ Diodorus Siculus: Historical Library V, 32.

- ^ Gaius Iulius Caesar: De bello gallico , introductory sentence.

- ^ Strabo: Geography IV, 1, 1.

- ↑ a b c d Wolfgang Meid: The Celts. P. 10 f.

- ^ K. McCone: “Greek Keltós and Galátēs , Latin Gallus 'Gaul'”. In: Die Sprache 46/2006, pp. 94–111, especially p. 95.

- ^ Ranko Matasović: Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic . P. 199, p. v. "* Kellāko-, fight, was'".

- ↑ Ranko Matasović: Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic , s. v. "* Kladiwo-, sword '".

- ↑ Julius Pokorny: Indo-European Etymological Dictionary , Volume 2. Francke, Bern 1959–1969, p. 351 sv “3. gal- or ghal- 'can' " .

- ^ Ranko Matasović: Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic . P. 149, p. v. "* Gal-n-, be able '".

- ↑ See the entry Κελτός in the English Wiktionary.

- ↑ Helmut Birkhan: Celts. Attempt at a complete representation of their culture. P. 47 f.

- ^ Gaius Iulius Caesar, De bello gallico VI, 18.

- ↑ Ranko Matasović: Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic , s. v. "* Kel-o-, hide '".

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 2, 33, 3; 4, 49, 3.

- ↑ Helmut Birkhan: Nachantike Keltenrezeption. P. 16 f.

- ↑ Martin Rockel: Principles of a History of the Irish Language. Vienna, 1989, p. 15.

- ↑ De bello gallico , Book VI, Chapter 14.

- ^ Archaeological Park Magdalensberg ( Memento from February 20, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Between heaven and earth - the early Celtic calendar structure on Glauberg ( Memento from February 11, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ^ Caesar: De bello gallico , VI, 13

- ^ Caesar: De bello gallico , VI, 16

- ^ Caesar: De bello gallico , VI, 14

- ^ Caesar: De bello gallico , VII 33.3

- ^ Strabo: Geographika , IV, 4,4

- ↑ Julio Caro Baroja: The witches and their world. Verlag Ernst Klett, 1967; in the biographies cited: Historiae Augustae (ascribed to Aelius Lampridus or Flavius Vopiscus).

- ↑ Franz Meußdoerffer , Martin Zarnkow: The beer: A story of hops and malt . CH Beck Verlag, 2014, ISBN 3-406-66667-1 , p. 35

- ↑ According to the article Asterix, the Celtic final syllable "-rix" stands for "king".

- ↑ Internet presence of the Keltenwelt Frög ( memento of December 7, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on September 17, 2012.