Nago-Torbole

| Nago-Torbole | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Country | Italy | |

| region | Trentino-South Tyrol | |

| province | Trento (TN) | |

| Coordinates | 45 ° 52 ' N , 10 ° 52' E | |

| height | 68 m slm | |

| surface | 28 km² | |

| Residents | 2,852 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density | 102 inhabitants / km² | |

| Factions | Torbole, Nago, Tempesta | |

| Adjacent communities | Arco , Riva del Garda , Mori , Ledro , Brentonico , Malcesine (VR) | |

| Post Code | 38060, 38069 | |

| prefix | 0464 | |

| ISTAT number | 022124 | |

| Popular name | Torbolani or Naghesi | |

| Patron saint | Sant'Andrea (Torbole), San Vigilio (Nago) | |

| Website | www.comune.nago-torbole.tn.it | |

Nago-Torbole is an Italian municipality with 2852 inhabitants (as of December 31, 2019) in the province of Trento . It belongs to the valley community Comunità Alto Garda e Ledro .

geography

location

The municipality of Nago-Torbole consists of three fractions :

- Torbole is located on the northern part of Lake Garda , directly on the Gardesana Orientale coastal road . The place itself is 68 m above sea level. Here the Sarca flows into Lake Garda, which leaves it as Mincio near Peschiera del Garda .

- Nago is located above Torbole at over 200 meters. Here is a former citadel at the foot of Castel Penede.

- Tempesta consists only of a few houses on the east bank of Lake Garda south of Torbole. South of Tempesta, the municipal boundary also forms the border with the province of Verona ( Veneto ).

The municipality has its seat in Torbole. The highest point in the municipality is the summit of Monte Altissimo ( 2079 m slm ).

The neighboring municipalities are: Arco , Riva del Garda , Mori , Ledro , Brentonico and Malcesine in the province of Verona.

climate

|

Average Temperatures and Precipitation for Torbole, 1981-2010

Source: Civil Defense of the Autonomous Province of Trento - Climate Department

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

According to the climatic classification of Italian municipalities , Nago-Torbole is assigned to climate zone E, which defines the heating period from October 15 to April 15.

history

Early history and antiquity

The first human traces in Nago-Torbole can be dated back to the late Upper Palaeolithic . Numerous stone artefacts have been found at Castel Penede , the foothills of Monte Altissimo di Nago and Monte Creino , which allow the conclusion that these were not just sporadic visits to the area. Further finds from the Mesolithic were discovered at Prati di Nago and Pré Alta. The first human remains come from a burial site from the Copper Age on the south-eastern outskirts of Nago. Other finds indicate the presence of humans in the Bronze Age and Iron Age . The Busa Brodeghèra site at the Rifugio Altissimo Damiano Chiesa can be traced back to the latter .

In 1832 the remains of a necropolis from the Roman era were uncovered on the castle hill of Castel Penede. Gothic and Roman coins from the reigns of Vespasian and Constantine were also found nearby . The Romans are also awarded the construction of a first road over the Valle S. Lucia to the lake shore. It is certain that the cart path over this small valley cut was the only road connection between Nago and Torbole until the middle of the 18th century. Other Roman finds were discovered in the center of Nago near the parish church of S. Vigilio and in the Tempesta district on the shores of Lake Garda.

middle Ages

During the Byzantine rule , the northern shore area of Lake Garda and thus also the area around Nago-Torbole belonged to the Curtis Ripae, i.e. the Riva farm . At the end of the 10th century it fell to the Bishop of Verona , in whose possession it remained until 1027, when Conrad II incorporated it into the bishopric of Trento . In 1039 the Pustertal monastery Sonnenburg was given rights of use and ownership in Sommolago ( "locus Summolacus" ), the area on the north shore of Lake Garda between Riva, Arco and Torbole on the lower reaches of the Sarca.

From the 12th century, the history of the two places began to crystallize in a more differentiated manner. 1154 Torbole and 1171 Nago were first mentioned in writing. In the same century, the Counts of Arco cleverly expanded their sphere of influence to the two places. Torbole was of interest because of the port and the associated customs revenue and Nago because of Castel Penede. Between 1198, when Philip of Swabia granted the Arcos the right to build a customs post at the port of Torbole, and 1210, when they received the castle above Nago as a fief from the Prince-Bishop of Trient Friedrich von Wangen , they were able to exercise their sphere of influence on the northeast Strengthen the corner point of Lake Garda.

The location on the important connecting route between the Adige Valley and Lake Garda inevitably meant that armies repeatedly passed through both places in the course of history. For example, in 1243 in the conflict between Ghibellines and Guelphs , when Guelfi troops sacked the two places after their defeat against the allies Ezzelino da Romanos .

On the other hand, the location not only attracted soldiers and mercenaries, but also travelers. One of the first was Dante Alighieri , who stayed at Castel Penede at the beginning of the 14th century and mentioned this in the Divina Commedia .

Early modern age

In December 1438 Castel Penede and with it both places fell under the rule of the Republic of Venice . During the struggle for supremacy on Lake Garda between Venice and the Viscontis from Milan, the Venetian fleet, which was transported from the Adige Valley to Lake Garda by the company Galeas per montes , was launched in Torbole. Pier Candido Decembrio , who described the Venetian company, described Torbole as a small estate. With Venice, however, the importance of Torbole as a port increased, which led to a noticeable increase in population, so that the church of S. Andrea in Torbole, first mentioned in 1175, had to be expanded.

The Venetian era ended in 1509 when Maximilian I and his troops were able to occupy the castle and the two places after the defeat of Venice in the Battle of Agnadello and the associated withdrawal of the Venetians from the area of Upper Lake Garda. In the period that followed, the Counts of Arco returned as imperial feudal lords. However, the municipality retained extensive administrative autonomy , as can be seen from the preserved municipal statutes.

In 1580 Michel de Montaigne took the boat from Torbole to Riva on his trip to Italy and left a first short literary description of the place.

Modern

During the War of the Spanish Succession , Castel Penede was destroyed by the French under General Vendôme in 1703 and fell into ruin. In 1766 Maria Theresa of Austria had a customs post built in Tempesta to prevent the import of cheap grain from Veneto across the lake. A measure that aroused the resentment of the population, so that two years later the customs station was destroyed by an angry crowd.

In the same year, after three years of construction, the new road between Nago and Torbole could be used for the first time. This street, known as Strada dei forti (today via Europa ), was completed around 1773. On his way to Torbole during his Italian trip in September 1786, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe still used the old cart path leading through the Valle S. Lucia. Goethe stayed only one day and one night in Torbole, which at that point still made a poor impression on him. The house doors without locks, the windows covered with oil paper instead of glass, and the houses without hygienic facilities, coming pretty close to the natural state, as Goethe noted in his diary based on Rosseau . Nevertheless, the delightful spectacle offered by the lake and nature predominated, especially since he was also making good progress on his work Iphigiene .

Goethe saw a lemon garden for the first time during his trip to Italy in Palazzo Giordani, in which Joseph II had already stayed in 1765 , which later became one of Torbole's attractions in the 19th century and was visited by Johann von Sachsen, among others .

At the end of the 18th century, Torbole had grown to around 400 inhabitants and was particularly known as a transhipment point for grain from the Po Valley . In 1787 the porters came together here to form an independent union-like association, one of the first in Trentino, to better express their wage demands. These were seasonal workers from the near and far, who had their livelihood with unloading and loading the boats and ships lying in the port of Torbole.

In the eventful Napoleonic era, French troops marched through Nago-Torbole in 1796, before it fell to the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1802 and then to the Kingdom of Italy from 1805 to 1814 . As a result of the Congress of Vienna in 1815, it was incorporated into the Austrian Empire .

The Risorgimento , which made itself felt in the political and intellectual circles of Trentino in the 19th century with its nation-state ideas and the question of the autonomy of Tyrol and as an increase in the separation from Austria, also found its supporters in the small town of Nago-Torbole. One of the leading figures in these circles was Antonio Gazzoletti from Nago, who presented this question to King Charles Albert of Sardinia-Piedmont in 1848 and to his son Victor Emanuel II in 1859 . The port of Torbole was used for the illegal import of weapons after Lombardy was annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont. As a result, more than 20 people, including dockworkers, boat owners and landlords from Nago-Torbole, were arrested in 1860, so that the community felt compelled to provide for the maintenance of their families. In 1864, after the conspiracy of Giuseppe Mazzini's action party , which sought a forcible annexation of Trentino and Veneto with the support of local sympathizers, further arrests were made. In the course of the growing nationality conflict, the German place name Naag-Turbel was emphasized as a differentiation to Italian-nationalist circles.

The increasing tensions with neighboring Italy prompted Austria-Hungary to build the Nago barrier in 1861 on the new road to Torbole. The obsolete work was later incorporated into the Riva fortress , but was never of particular military importance, not even after the loss of Veneto in 1866 as a result of the Third Italian War of Independence .

With the annexation of Veneto to the Kingdom of Italy , the northern coast of Lake Garda, which remained Austria, developed into the Riviera of the Empire . The picturesque Torbole with its small harbor exerted its fascination especially with artists and writers such as Hans Lietzmann , Paul Franz Flickel , Paul Hey , Michael Zeno Diemer , Eduard Weichberger , Georg Macco , Hermann Drück , Heinrich Adam , Carl Wuttke , Josef Rolletschek , Ludwig Friedrich Hofelich and others. It was quickly taken over by the emerging tourism as a fishing village and advertised accordingly. In 1875, with the construction of a fish farm, an additional source of income was created and the increasing demand for fish in the inns in Torbole was taken into account.

At the end of the 19th century, the traffic routes were further expanded. In 1884 the road from Nago to Arco was opened and with the opening of the local railway Mori-Arco-Riva and the Nago-Torbole train station in 1891, the municipality was connected to the railway network, from which tourism and day-trippers in particular benefited.

20th and 21st centuries

From the increasing tourism, in 1907 the Grand Hotel Torbole was opened, which was converted into the Colonia Pavese in the 1930s , benefited almost exclusively Torbole. From 1900 to 1910 the population increased here almost twice as fast as in Nago. In the latter, the economy at the turn of the century was still almost exclusively characterized by agriculture , alpine pasture and forestry . This was mostly geared towards subsistence farming and was characterized by a strong fragmentation of property so that livelihoods were often not secure. The consequences were malnutrition and deficiency diseases such as pellagra . The poverty and neglect in Nago were increasingly noticed by travelers heading to Lake Garda. Children begging at the train station in Nago were a common sight. It was not until the 1910s that people in Nago tried to make more money with strangers. In 1911 the construction of a cable car from Torbole to Nago was planned, but the project did not get beyond the planning phase, and in 1913 the first larger and more modern hotel was built near the train station in Nago.

Nevertheless, the place continued to benefit only marginally from the tourist development, but did not escape the nationalist debate. This was fueled by the publication of a pamphlet by Giulio de Frenzi, a pseudonym of the writer and later fascist politician Luigi Federzoni , with the telling title La italianità del Gardasee (Eng. The Italianity of Lake Garda). In it, the author denounced, among other things, the displacement of Italian owners on the private and commercial real estate market in favor of financially strong German-speaking owners on the north shore of the lake. Because of these national and social tensions, the inhabitants of Nago and Torbole from the most diverse social classes, even if the liberal bourgeois element predominated, became active in nationalist irredentist organizations. In this context, the deportation of Scipio Sighele because of political nationalist agitation by the Austro-Hungarian authorities caused a stir in the summer of 1912. Not only the local council in Nago protested against the deportation, Sighele owned a house, but also parts of the population with signature campaigns.

First World War

With the outbreak of the First World War , the able-bodied male population was drafted. Like most of those drafted from Trentino, the soldiers from Nago-Torbole were deployed on the Eastern Front against Russia . Until the Italian entry into the war in May 1915, the Austro-Hungarian army built numerous field positions around the two places. A tank plant planned by the Austrian General Staff below the summit of Monte Altissimo di Nago, however, did not get beyond the first excavation work. On May 22, 1915, both places were evacuated and the population was brought to Bohemia and Moravia as well as to the Mitterndorf refugee camp, from where they only returned between 1918 and 1919.

During the war, the front ran directly through the municipality of Nago-Torbole and formed an Austro-Hungarian front arc to the south. In the first and last year of the war in particular, there were repeated battles on the northern foothills of Monte Altissimo di Nago. For example, in December 1915 when the Italians attacked Malga Zures and in the summer of 1918 when the Austro-Hungarian troops briefly captured the neighboring Doss Alto di Nago held by the Czechoslovak legions . Torbole, on the other hand, was the target of the Italian navy , who undertook sabotage actions with MAS units . The section of the front at Doss Casina gained a certain degree of awareness through the presence of some futurists , including Filippo Tommaso Marinetti , Anselmo Bucci , Antonio Sant'Elia , Mario Sironi , Achille Funi and Luigi Russolo , who had volunteered in the Italian army. Both Nago and Torbole were badly affected by artillery fire and looting, and after the war they were classified in the black zone and the zone most severely damaged by the war.

Interwar period

With the construction of the Gardesana Orientale in 1929, the state road between Nago and Torbole in 1935 and the Etsch-Gardasee tunnel pierced in 1939 , the landscape in the municipality was to change radically. In the 1920s, the socio-economic differences between the two places became more pronounced. While Nago was still dominated by agriculture, the service sector and handicrafts played the greater role there due to tourism in Torbole. These differences led to the fact that both places made efforts to form independent communities, as was the case in the second half of the 19th century. This endeavor was followed by the fascist municipal reform in 1927, on the basis of which over 2000 Italian municipalities with fewer than 2000 inhabitants were incorporated. Before that, and in 1929 Nago-Torbole was attached to the municipality of Riva.

The reconstruction in the post-war period and the subsequent global economic crisis and its consequences were decisive for the fact that tourism in Torbole no longer had the same growth rates until the Second World War as immediately before the First World War. During fascism, it was mainly state institutions and organizations, such as the Colonia Pavese, established in 1935 for tuberculosis prevention , that determined the image of tourism in Torbole. At the beginning of 1939, Lake Garda was also included in the Nazi holiday culture with the KdF trips .

Second World War

With the Italian entry into the war on June 10, 1940 at the latest, tourism came to a complete standstill. The repressive measures of the fascist regime and the increasing food rationing made themselves increasingly noticeable. After the fall of Mussolini and the armistice with the Allies in September 1943, Nago-Torbole was also occupied by German troops on September 9 and incorporated into the foothills of the Alps . The Germans requisitioned the school buildings, hotels and private accommodation as quarters . An air force command was housed in the Casa Beust at the port . The Colonia Pavese, which housed over 250 children, had to be cleared within 24 hours. In the following years it served as a Wehrmacht hospital . On June 8, 1944, 11 resistance fighters were shot by members of the Trientiner security association , the Bolzano police regiment and the SS during an action against the Resistance between Riva, Arco and Nago-Torbole . In 1944, the Caproni works in the Etsch-Gardasee tunnel near Torbole began operations. In the underground armaments factory , parts for so-called miracle weapons such as the Me-262 and the V2 were produced. As part of the so-called Alpine fortress , the organization Todt built the Blue Line with ring stands and bunkers around Nago-Torbole between 1944 and 1945 .

On the morning of April 29, 1945, the US 10th Mountain Division began to attack Nago-Torbole. In two groups, one over the Gardesana Orientale and one over the western flank of the Altissimo di Nago, the Americans succeeded in breaking the resistance of the last German units of the XIV Panzer Corps , which joined after the collapse of the German front on April 21 Bologna had set off to the north during the Allied spring offensive . Torbole was captured in the early morning of April 30 and Nago in the late morning after 30 hours of fierce fighting. The company also used amphibious vehicles of the type DUKW , whereby one DUKW was lost before the mouth of the Sarca .

Post-war period, economic miracle and mass tourism

Immediately after the liberation, so-called National Liberation Committees were set up in Nago and Torbole , which were primarily concerned with maintaining public order, repairing war damage and clearing war material. The tasks of the CLN also included looking after returning military internees . The CLN in Torbole also set itself the task of building a new port for the fishermen in Torbole, as the old port had largely fallen victim to the construction of the Gardesana. With the first municipal elections in Riva in March 1946, the CLN practically dissolved. Nago and Torbole were still districts of Riva, but the discussion about a new establishment had already been sparked by the CLN in October 1945.

At the end of the 1940s, tourism development returned to the fore of public interest. In this context, administrative independence was seen as crucial for future development in both places. The first step in this direction was taken by the hoteliers in Torbole, who in 1952 founded a tourist association independent of Riva. The debate was also fueled by a new zoning plan , which was viewed as a sell-out of Nago-Torbole. In the winter of 1955/56, the necessary signatures for a referendum were finally collected, which was held on July 15, 1956. Over 70% of the electorate voted in favor of re-establishing the municipality of Nago-Torbole, which was completed in 1958.

Little had changed in the socio-economic situation until the 1950s. Agriculture, which was still oriented towards self-consumption, determined the lives of most of the residents. Only wine and tobacco were grown in the sense of an agricultural production. Fishing was also intended for personal consumption or for the local market. The emigration as guest workers to Switzerland , Germany or the Belgian mining areas were only the logical consequence. With the advent of the economic miracle , the number of overnight stays slowly but steadily increased. In 1956 there were already over 120,000 overnight stays in the municipality. There were already 20 hotels, 17 of them in Torbole, 16 guest houses, 27 room renters and a campsite. Numerous restaurants and shops sprang up. At the same time, however, there were also infrastructural problems. In summer there was a lack of drinking water and water had to be rationed. To remedy this, untreated water was pumped from the lake in Torbole, with the corresponding hygienic problems. A new water pipe was not completed until 1957. Similar problems arose with sanitation .

With the founding of the sailing club in 1964, Torbole also became known in water sports circles. The founding of the Torbole surf club in 1978 also contributed to the level of awareness . In the period that followed, the location was repeatedly host of national and international sailing and surfing events. With the completion of the A22 autostrada in 1974, Nago-Torbole was finally opened up for mass tourism . In 2015, the number of overnight stays, with almost 760,000 overnight stays, 88% of them foreigners, had increased more than sixfold since 1956.

Population development

| year | 1921 | 1931 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents | 1,761 | 1,849 | 1,868 | 2,081 | 2,199 | 2,303 | 2,236 | 2,289 | 2,728 |

Source: ISTAT

tourism

Like the surrounding area, Torbole is a popular tourist destination . The place is particularly popular with windsurfers due to the constant winds. In addition, the surrounding Lake Garda mountains offer countless opportunities for mountain bike tours as well as hiking and climbing routes .

Attractions

- Castel Penede

- Roadblock Nago

- Natural park around Monte Baldo

- Customs house - On a pier in the harbor basin there is a small customs house from the time of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, as Tempesta was the border between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Kingdom of Italy until the First World War . The origins of the house are probably even further back, as a relief on the outer wall recalls the Venetian period. In the summer months the customs house is partly used as a bar. Today it is privately owned.

- Memorial plaque in Torbole, which commemorates the stay of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in Torbole during his Italian trip in September 1786.

- Large mural on the facade of the "Casa Beust", the old home of Friedrich Constantin von Beust , in Torbole on Lake Garda: St. Antonio speaks to the fish by Hans Lietzmann

- Valle di Santa Lucia with an old, roughly paved path through olive groves. Once the only connection between Nago and Torbole. The Venetian fleet in the company Galeas per montes was lowered through this valley from the Adige Valley to Torbole in 1439 .

Personalities

- Antonio Gazzoletti (1813–1866), poet and librettist

- Scipio Sighele (1868–1913), criminologist , anthropologist and pioneer of mass psychology

- Hans Lietzmann (1872–1955), painter and draftsman

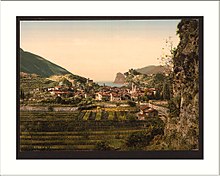

photos

literature

- Franco Bonomi, Tullio Pasquali, Valentino Rosà: Arco, Nago-Torbole e Mori . In: Museo tridentino di scienze naturali (ed.): Preistoria alpina N. 21 - 1985 , Temi, Trient 1986. ( PDF )

- Maria Luisa Crosina, Franco Farina: Il viaggio segreto con Goethe da Karlsbad a Malcesine . In: Accademia roveretana degli Agiati (ed.): Atti della Accademia roveretana degli Agiati Series VIII Volume IV (I) A (2004) , Accademia roveretana degli Agiati, Rovereto 2005. ( PDF )

- Giorgia Gentilini, Gian Pietro Brogiolo, Walter Landi: Castel Penede a Nago nel Sommolago. In: Elisa Possenti, Giorgia Gentilini, Walter Landi, Michela Cunaccia: APSAT 6. Castra, castelli e domus murate. Corpus dei siti fortificati trentini tra tardo antico e basso medioevo. Saggi. SAP Società Archeologica srl., Mantua 2013, ISBN 978-88-87115-83-3 ( PDF )

- Ferdinando Martinelli: Saluti dal Garda. Conoscere Torbole e Nago , Piave, Belluno o. J.

- Graziano Riccadonna: Anni di guerra: Nago e Torbole 1940-1945 , Gruppo culturale Nago-Torbole, Arco 1995.

- Michael Wedekind: Folk Studies and Folk Politics in the Area of German Language Islands in Northern Italy . In: Rainer Mackensen (Hrsg.): Origins, types and consequences of the construct “population” before, during and after the “Third Reich”: On the history of German population science, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-531- 16152-5

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Statistiche demografiche ISTAT. Monthly population statistics of the Istituto Nazionale di Statistica , as of December 31 of 2019.

- ↑ Municipal statute in Italian (PDF; 320 kB), accessed on May 29, 2017.

- ↑ Mean maximum and minimum temperatures; Maximum and minimum temperatures - extreme values; Monthly and yearly mean values of the temperature. (PDF links) Weather station Torbole. Civil defense of the autonomous province of Trento, accessed on June 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ monthly and annual rainfall; Number of monthly and annual precipitation days. (PDF links) Weather station Torbole. Civil defense of the autonomous province of Trento, accessed on June 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Website of the Agenzia nazionale per le nuove tecnologie, l'energia e lo sviluppo economico sostenibile (ENEA), accessed on May 20, 2019 (Italian) (PDF; 330 kB)

- ^ Franco Bonomi, Tullio Pasquali, Valentino Rosà: Arco, Nago-Torbole e Mori , pp. 181-190

- ^ Giorgia Gentilini, Gian Pietro Brogiolo, Walter Landi: Castel Penede a Nago nel Sommolago , p. 217

- ^ Giovanbattista Mezzi: Nago e Torbole: dalle origini al secolo XVI pp. 36–39

- ↑ History Riva del Garda (Italian) , accessed on February 16 2018th

- ↑ Martin Bitschnau , Hannes Obermair : Tiroler Urkundenbuch, II. Department: The documents on the history of the Inn, Eisack and Pustertal valleys. Ed .: Tiroler Landesmuseen-Betriebsgesellschaft mb H. Band 1 : By 1140 . Universitätsverlag Wagner, Innsbruck 2009, ISBN 978-3-7030-0469-8 , p. 174-182, No. 201 (f) .

- ↑ Giovanbattista Mezzi: Nago e Torbole: dalle origini al secolo XVI , pp. 44–45

- ^ Giorgia Gentilini, Gian Pietro Brogiolo, Walter Landi: Castel Penede a Nago nel Sommolago pp. 217-218

- ^ Emanuele Curzel, Gian Maria Varanini: La documentazione dei vescovi di Trento (XI secolo - 1218) , p. 81

- ↑ Giovanbattista Mezzi: Nago e Torbole: dalle origini al secolo XVI , pp. 51-60

- ↑ Giorgia Gentilini, Gian Pietro Brogiolo, Walter Landi: Castel Penede a Nago nel Sommolago , pp. 222-224

- ↑ Historical outline of the Church of S. Andrea in Torbole (Italian) , accessed on January 30, 2018.

- ^ Giorgia Gentilini, Gian Pietro Brogiolo, Walter Landi: Castel Penede a Nago nel Sommolago , pp. 224–226

- ^ Dazio di Tempesta - Giornaletrentino.it (Italian) , accessed February 1, 2018.

- ↑ Maria Luisa Crosina, Franco Farina: Il viaggio segreto con Goethe da Karlsbad a Malcesine , pp. 136-138

- ↑ Maria Luisa Crosina, Franco Farina: Il viaggio segreto con Goethe da Karlsbad a Malcesine, pp. 136-138

- ^ Maria Luisa Crosina, Franco Farina: Il viaggio segreto con Goethe da Karlsbad a Malcesine , p. 140

- ↑ Aldo Miorelli: Il sindacato dei Facchini di Torbole (1787) , pp 9-18

- ^ Tullio Rigotti: Domenico Rigotti. Dalla cospirazione mazziniana (1863–1864) alla rete del fuoriuscitismo (1914–1915) , pp. 15–22

- ↑ Michael Wedekind: Volkstumswwissenschaft and Volkstumsppolitik in the area of German language islands in Northern Italy , pp. 84–88

- ↑ On the history of the Garda Trentino Tourist Association (Italian) (PDF; 117 kB), accessed on February 5, 2018.

- ^ Tullio Rigotti: Domenico Rigotti. Dalla cospirazione mazziniana (1863–1864) alla rete del fuoriuscitismo (1914–1915) , pp. 78–80

- ^ Tullio Rigotti: Domenico Rigotti. Dalla cospirazione mazziniana (1863–1864) alla rete del fuoriuscitismo (1914–1915) , pp. 83–84

- ^ Donato Riccadonna, Mauro Zattera: Sentieri di confine. Segni da ritrovare della Prima guerra mondiale nell'Alto Garda e Ledro , pp. 54–58

- ^ Mauro Grazioli: Fra le rovine della guerra. Il Basso Sarca e la Valle del Ledro alla fine del primo conflitto mondiale , pp. 250-253

- ^ Donato Riccadonna, Mauro Zattera: Sentieri di confine. Segni da ritrovare della Prima guerra mondiale nell'Alto Garda e Ledro , pp. 225–227

- ↑ Graziano Riccadonna: Anni di guerra: Nago e Torbole 1940-1945 , pp. 16-17

- ↑ 1939 hardly any time or money for long journeys , accessed on February 7, 2018.

- ^ Graziano Riccadonna: Anni di guerra: Nago e Torbole 1940-1945 , pp. 19-23

- ^ The Resistenza in Trentino (Italian) , accessed on February 8, 2018.

- ↑ Giorgio Danilo Cocconcelli: factories tunnel. Le officine aeronautiche Caproni e FIAT nell'Alto Garda 1943-1945 , pp. 202-243

- ↑ Ben Appleby, Aldo Miorelli, Antonella Previdi: Sulla Blaue Linie con la Decima Divisione da Montagna (USA). I bunker, le vicende, i documenti, le immagini (Garda Trentino April 27th - 2nd Maggio 1945) , pp. 89-99

- ^ Ferdinando Martinelli: Dalla dittatura alla democrazia. I Comitati di Liberazione Nazionale a Riva del Garda, Arco, Torbole e Nago 1945-1946 , pp. 72-82

- ↑ Giacomo Nones: La separazione da Riva , pp. 48-63

- ↑ Aldo Miorelli: La rinascita del comune , pp. 74-87

- ↑ Aldo Miorelli: I naghesi ei torbolani , pp. 106-107

- ↑ Statistics from the Garda Trentino Tourist Association 2015 (Italian) , accessed on February 8, 2018.

- ^ Italian Journey, Part 1 , from gutenberg.org, accessed on May 29, 2017