Witch hunt

As a witch hunt , is called tracing, hard business, torturing and punishing (in particular the execution) of persons, is believed by those practicing witchcraft or stood with the devil in the league. In Central Europe it took place mainly during the early modern period . Seen globally, the persecution of witches is widespread to the present day.

The peak of the wave of persecution in Europe lies between 1550 and 1650. The reasons for the significantly increased mass persecution in some regions compared to the Middle Ages in the early modern period are diverse. At the beginning of modern times there were a multitude of crises such as the Little Ice Age , pandemic epidemics and devastating wars. In addition, structural mass persecution could only occur when individual aspects of belief in magic were transferred to the criminal law of the early modern states . There was an interest in the persecution of witches or pre-Christian-Germanic patterns of interpretation, which attributed personal misfortunes such as regional bad harvests and crises to magic, existed in broad sections of the population. Hunts of witches were sometimes actively demanded and practiced against the will of the authorities .

Overall, it is estimated that three million people were tried in the course of the witch hunt in Europe, with 40,000 to 60,000 people executed. Women made the majority of the victims in Central Europe (around three quarters of the victims in Central Europe) as did the informers of witchcraft and witches. In Northern Europe, men were more severely affected. There is no clear connection between denomination and the persecution of witches.

Today, witch hunts are particularly common in Africa , Southeast Asia and Latin America .

antiquity

Although the legal use of the term "witch" was only introduced at the beginning of the 15th century, the belief in magicians can already be demonstrated in the ancient civilizations . Magical practices were carefully observed and often feared as black magic . Both in Babylonia ( Codex Hammurapi : water sample ) and in ancient Egypt magicians were punished. The Old Testament forbids sorcery ( Lev 19.26 EU ) and calls for the persecution of sorcerers ( Ex 22.17 EU ). However, the Bible does not recognize witches in the sense of the early modern period. According to the Twelve Tables of the Romans, negative spells were punishable by death (Table VIII). However, there was never a targeted persecution of alleged witches as it did later in the early modern period .

The old church was not involved in persecutions and rejected the views and practices associated with witchcraft as superstition ( canon episcopi ).

middle age

The widespread opinion that the persecution of witches was mainly a phenomenon of the Middle Ages is just as wrong as the opinion that the great waves of modern witch persecution were primarily aimed at or carried out by the ecclesiastical inquisition .

In the Carolingian early Middle Ages, however, there was no persecution of witches.

The first evidence for the German term “witch” in the context of legal prosecution can be found, as Oliver Landolt was able to show, in the crime books of the city of Schaffhausen from the late 14th century. The term first appeared in Lucerne between 1402 and 1419.

inquisition

The first isolated convictions of witches occurred in the 13th century with the rise of the Inquisition , whereby the objective of the Inquisition must be observed: If the witch trials of secular courts, which were dominant in the early modern era, aimed at punishing allegedly guilty people, the Inquisition aimed to repentance and Reconciliation of the accused, which was expressed in the less frequent use of the death penalty. Furthermore, the main focus of the Inquisition was not on witches but on heretics . This priority becomes clear in the instruction of Pope Alexander IV of January 20, 1260 to the inquisitors that witches should not be actively pursued, but rather arrested in response to reports. Trials against witches should be postponed if there is insufficient time, the fight against heresies has priority. The state Spanish Inquisition , founded in the late 15th century, partially rejected the persecution of witches. The Roman Inquisition that followed in the 16th century also repeatedly intervened against the persecution of witches.

Early modern age

The witch hunts in Europe took place predominantly in the early modern period , from 1450 to 1750. They reached their peak between 1550 and 1650, in Austria until 1680. The Holy Roman Empire and the areas bordering on it were hardest hit. It is estimated that Germany alone accounted for 40,000 witch burnings (and thus more than half of the total European number).

Cultural and historical background

With the Christianization of Europe, pagan beliefs were reinterpreted and reinterpreted . The pre-Christian cults were classified as superstitions in the late Middle Ages and early modern times . At that time, Christianity had already adopted Jewish-Old Testament worldviews: For example, in the Old Testament it says “You shouldn't let a witch live” according to Ex 22.17 EU . The New Testament knows the belief in "evil spirits", e.g. B. Jesus' healing of a possessed person by allowing the demons to enter a herd of pigs (see Mk 5, 1-20 EU ). According to the Acts of the Apostles , Paul temporarily beats a magician with blindness ( Acts 13 : 4–12 EU ). Nevertheless, in early Christian theology the fundamental "doubt about the effectiveness of any sorcery" dominated. It was also believed that the demons could not gain any power over believing Christians. The “pagan” gods were polemically equated with mere demons. Against this background, the church had for centuries put a relatively stable stop to the systematic persecution of witches; In individual cases, however, relevant “crimes” could be punished. Until the 13th century, however, the official church conviction remained that the “belief in sorcery” was “pagan heresy and imagination” and should “be punished by church punishments such as penance or - in severe cases - by exclusion from the community”.

However, a theological discourse began as early as early Christian times, which later turned out to be extraordinarily disastrous: the combination of sorcery and demonology in the so-called devil's pact . This was first elaborated by Augustine of Hippo († 430) in his work De doctrina christiana from 397 AD. However, it was a very unspecific, theoretical consideration that, it is assumed, was only meaningful as a metaphorical image . This teaching was accepted in the High Middle Ages , v. a. also by Thomas von Aquin († 1274), who invented the existence of a tightly organized “demon state” with many seduced human followers, which was a significant “leap in quality” compared to the idea of “lone warriors” who knew how to magic. This idea of a powerful, closed counterparty then required much more severe prosecution and sanctioning. According to Thomas, the devil's pact was concluded through sexual intercourse between humans and demons. Such a reason is explained by the fact that Thomas generally viewed sex out of lust as unnatural. The main concern of the official church, however, was in the 12th-14th centuries. Century especially the Cathars , from their point of view, so to speak, the "arch heretics" (etymologically, "heretics" is also derived from "Cathars"). In addition to the use of physical force, the “propaganda war” also played an important role in combating this religious movement: Black magic, pacts with the devil and sexual debauchery. Based on this, the “sect of witches and wizards” was soon put on an equal footing with the other heretics in terms of their practices and their dangerousness. The witches' discourse was supplemented by another direction: traditional Christian anti-Judaism . The Jews were defamed by all sorts of accusations (exercise of satanic rites, harmful magic , well poisoning , etc.), which could easily be transferred to witches and wizards (cf. the Witches' Sabbath ).

Serious crises at the transition from the Middle Ages to the modern age

From the 15th century onwards, the Little Ice Age in Europe contributed to the massive insecurity of the people , which led to the late medieval agricultural crisis , "rising prices" (inflation) and famine. The unfavorable climate was often reflected in concrete catastrophic extreme weather events (hail, storms, etc.), which in a predominantly agricultural society could quickly lead to existential hardship. Various epidemics found easy victims among the often weakened people. Notorious is the Black Death (the plague), which broke out for the first time and pandemically in Europe from 1347 to 1353 and repeatedly terrified the continent into the 18th century. Many people felt that the Church did not have satisfactory answers to mass extinction. The church's claim to sole representation was also questioned more fundamentally and more openly: Heretical movements could mostly still be suppressed in the late Middle Ages. At the latest with the successful establishment of Protestantism from 1517, the claim of the church to be “Catholic”, i.e. all-encompassing, collapsed. In the Franconian region the "witch-mad" began in 1575 in the margraviate of Ansbach, Nuremberg followed in 1591. The persecutions of witches were more violent after 1622 in Würzburg and after 1623 in Bamberg. Wars also contributed to the uncertainty. In Central Europe, for example, there were more and more witch trials during the devastating Thirty Years War from 1618 to 1648. For many, this bundling of crisis phenomena was accompanied by a massive psychological shock to the worldview and the loss of truths that were believed to be certain, and could increase to the point of expectation of the imminent apocalypse. The search for scapegoats is an anthropological constant in such existential emergency situations. The persecution of witches was therefore an expression of widespread fears and mass hysteria , which were often expressed as regular popular movements and even against the will of state authorities and the churches. In the latest waves of persecution in the 17th century, such as the Salem witch trials in Massachusetts , the persecutors took seriously accusations by children who had succumbed to mass hysteria.

Personal motives

Material motifs played an important role in many denunciations; Finally, the informer was given a share of the victim's property to be distributed. Likewise, simply antipathy or neighborhood disputes could end up at the stake for one of the parties. But even if limited persecution was often possible against secular and clerical authorities with a correspondingly robust demeanor of those reporting the witchcraft, more systematic and more extensive actions usually required a greater or lesser degree of agreement between state authority, church representatives and the people.

Role of the Churches and Confessionalization

The churches played an ambiguous role in this. There were powerful witch theorists who were clergy. This is particularly true of the author of the notorious witch's hammer Heinrich Kramer , who belonged to the Dominican order. However, Kramer had to fight against church resistance all his life, for example in Innsbruck (where he was expelled from the country by the bishop) or in Cologne (the Cologne Inquisition condemned the unethical and illegal practices of the witch hammer because they were not in accordance with Catholic teaching). Likewise, many of the most important opponents of the witch hunt (well-known church critics were, among others, Johannes Brenz , Johann Matthäus Meyfart , Anton Praetorius , Friedrich Spee and Johann Weyer ) came from the church. Misogyny, which is common in the churches , had a devastating effect in that women were seen as an “easy gateway” for the devil and, depending on region or denomination, were more often victims than men. On the basis of the Catholic Vulgate translation of Exodus 22:17 “you should not let the sorcerers live”, men were condemned on average more often in Catholic areas than in Protestant areas, where the translation of the Luther Bible “A witch you shouldn't let them live ”.

On the papal side, the belief in witches was represented relatively late and only in a single bull; We are talking about Innocent VIII and his witch bull of 1484, which came about at the instigation of Heinrich Kramer.

Preachers who imparted theoretical demonology to the population in a practical way and thus often gave direction and clout to the search for answers of the masses already outlined were ominous.

Historically, however, the widespread notion that “the Inquisition” was responsible for carrying out the witch trials has been refuted. In fact, there were much fewer witch trials in countries where the Inquisition was able to prevail, and torture was also limited (e.g. in Spain, Italy and Ireland; in Portugal there were no fewer than three executions of “witches "). The downside of this inquisitorial reluctance, however, is that it was not used in the persecution of "heretics" and Jews.

Michael Hochgeschwender considers denominational differences in particular to be the cause of the witch madness. He sees the persecutions that took place at the beginning of modern times in Europe and later in the area of today's USA as well comparable. Here as there, confessional conflicts were also used to resolve family and property conflicts or to eliminate competitors and unwelcome outsiders. The persecution of witches is a typical consequence of denominational divisions. In contrast to the religiously divided Central Europe of the post-Reformation period, they hardly occurred in southern Europe or only in a moderate form.

Role of secular authorities

With regard to the witch trials, however, it should be noted that the proceedings were primarily initiated by secular institutions and heard before state courts. As a matter of principle, the secular rulers had to be ready to promote or at least tolerate witch trials and to make their administrative and judicial apparatus available for this purpose. However, small and medium-sized rulers were more prone to massive witch hunts than large territorial states. Small and micro states (as they occurred most frequently on the territory of the Holy Roman Empire) often only had poorly trained judges, whose decisions could not have been revised through a regulated process of authority at a higher level. In addition, those in charge of the state in the manageable atmosphere of small rulers felt much more often indirectly or even directly affected by alleged witchcraft in the neighborhood. Furthermore, many old rulers fought not to lose their jurisdiction to the early nation-states that were being formed. Unauthorized trials against witches served here for legitimation.

Structural causes

- At many universities the persecution of witches was theoretically supported, discussed and promoted in the various faculties; Such ideas found widespread dissemination through the Europe-wide networking of academics.

- The innovation of book printing, invented around 1450, had a similar effect. This media revolution made it possible for the first time to bring the latest “findings on magical nonsense” to a larger audience. The privilege of censorship was mostly on the part of the proponents of witch persecution, so that they could control the publication activity accordingly.

- In Central Europe, which is still relatively more densely populated, new ideas about magicians spread faster than in more sparsely populated peripheral areas.

Why could witch trials become a mass phenomenon?

As soon as the witch trials had reached a certain extent, inter alia. the following factors are often "catalysts" for ever more far-reaching persecution:

- The legalization of torture in many European legal systems resulted in many "confessions".

- The accused's confessions, often extorted under torture, convinced many previously uninvolved of the correctness and dangerousness of the allegations and of the existence of witchcraft in general.

- Common questions to the accused included about accomplices. Here, too, torture led to all sorts of acquaintances being “announced” in order to put an end to the torture quickly.

- The more the witch hunt became a mass phenomenon in a territory, the more dangerous criticism of the trials became and the less it was still practiced.

- Residents of neighboring territories often wished that their authorities would act just as consistently against the "witchcraft" and exerted corresponding pressure.

- A psychological attempt at understanding lies in the fact that the peak of the wave of persecution in Europe paradoxically lies between 1550 and 1650, i.e. contradicts the philanthropic aspect of the Enlightenment . The explanation of this paradox is that during the Middle Ages the mental energy fixed by belief in gods and demons no longer possessed any projection objects as a result of the clarification of their reality character and therefore attached them collectively to people who had not previously been exposed to these impulses to this archaic degree was.

distribution

The number of convicts varied greatly in the different regions. There were focal points such as Scandinavia, Thuringia, the Rhineland , Westphalia (such as the witch hunt in the Duchy of Westphalia ), the Catholic princedoms in the German Empire (see e.g. witch trials in Würzburg or Bamberg ; also the dioceses of Cologne (approx 2000 victims), Mainz (approx. 1500 victims) and Trier (approx. 350 victims) were the focus of persecution at the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th centuries, the Netherlands, Mecklenburg, Lower Saxony, Schleswig-Holstein, areas in North America and the Swiss Valais . Around the year 1431, the Swiss chronicler Hans Fründ describes the circumstances surrounding the witch hunts that began in Valais from 1428, with a thoroughly critical view of current affairs. Research assumes that around 10,000 witch trials took place in what is now Switzerland. But there were also other areas, such as the Duchy of Württemberg , where there was hardly any persecution. In Spain, the Inquisition prevented the witch hunt. Claims, as they were spread again in the Kulturkampf , that the Jesuits incited the persecution of witches, have already been refuted by the detailed investigations of the historians Johannes Janssen and Bernhard Duhr .

The first witch trial in Scandinavia took place in Finnmark in 1601 . Two men (in Scandinavia the persecution extended much more to men) were sentenced to death by fire because they were supposed to have killed a royal commissioner in what was then Vardøhuslen by magic damage. From 1601 to 1678, 90 people, mostly women, were burned. It was the worst persecution in Norway in peacetime. In the fishing communities of Vardø , Kiberg, Ekkerøy and Vadsø , parts of the female population were exterminated during this time. In 1617 some women were accused of having caused such a storm by magic that 40 fishermen drowned in one day. They were burned.

There is no clear connection between the regional denomination and the persecution of witches: In some Catholic countries, such as the Papal States, Ireland, Portugal and Spain, the persecution of witches was rare to very rare. In areas of the Orthodox Churches they were almost nowhere to be found, with the exception of Russia in the course of modernization, i.e. the adaptation of the country to Central Europe by Tsar Peter . In mixed confessional Germany, both Protestant and Catholic territories were affected to different degrees. In the Ottoman Empire, which also ruled the Balkans, there was no large-scale witch hunt, not even in Christian areas, because it would have contradicted the teachings of Islam.

Justice against witches

The trials in the Holy Roman Empire were based on the embarrassing court order of Charles V , which, however, was limited to the offense of “magic spells” and provided that witchcraft was to be punished with a fine for the actual damage. However, the court order of the (Catholic) emperor was only partially followed in Protestant territories. In Protestant regions this rule was tightened because witchcraft represents a covenant with the devil and is therefore always worthy of death.

An important element of the witch trial was the confession, which was also sought through threats or execution of torture. Those accused of the witchcraft crime should admit and show repentance and betray co-conspirators. One witch trial, for example, might lead to a number of others. There are indications that, for example, in German witch trials of the 17th century, nobles were deliberately included in the persecution in the futile hope of putting an end to the waves of trials.

It is true that the neck court order attempted to strictly regulate torture and renounced divine judgments . Evidence of guilt was only given if the defendant made a confession, which had to be repeated without torture. This relative progress, however, was often thwarted in practice: They resorted to the Hexenhammer (see below), which spoke of "interruption" and "continuation" of the torture in order to be able to resume an unsuccessfully broken torture. Also the renunciation of divine judgments was lifted on the part of the Protestants by the so-called witch tests, most famous the water test and the kettle trap, which also existed as divine judgments, as well as new elements the weighing test , the pricking of birthmarks (" witch marks "), the Reading of Jesus' ordeal etc.

Another important element was denunciations. Informers did not have to reveal to the defendant what was important for the success of the witch trials. In practice, appeals were made to other witnesses to the crimes, so that the first informer was followed by others. In the event of a conviction, the denouncer sometimes received a third of the defendant's property, but at least 2 guilders. A well-known example is the case of Katharina Kepler , the mother of the astronomer Johannes Kepler . In 1615 she was called a witch by a neighbor in Wuerttemberg due to a dispute, held prisoner for over a year and threatened with torture, but was finally acquitted due to the efforts of her son.

Procedure in witch trials

The procedure at witch trials of the early modern period was structured according to the following pattern:

- Indictment: Often an actual indictment was preceded by years of rumor . The indictment could be based on a denunciation by an already imprisoned witch - possibly under torture - a so-called denunciation . Alleged witches were rarely given the right to a defense.

- Imprisonment: Prisons in today's sense did not yet exist in the early modern period, so the accused were kept prisoner in cellars or towers. The witch's towers , which can still be found in many places today , were often not pure witch's towers, but mostly general prison towers, sometimes just towers of the city walls. At the beginning of the trial, the accused was completely stripped and shaved ( depilation ). This was done so that she couldn't hide any magic or to break her magic power. Then she was examined all over her body for a witch mark. The executioner raped the victim on this occasion .

- Interrogation: There are usually three phases of interrogation: the amicable interrogation, the interrogation with demonstration and explanation of the instruments of torture and the embarrassing interrogation in which the torture was used.

- Amicable questioning: The actual questioning by the judges . The questions were very detailed; they included, for example, sexual intercourse with the devil , the " devil's agreement" and agreements or appointments with him.

- Territion: If the accused did not make a " confession ", the territion (dt. Fright ) followed, d. H. showing the instruments of torture and their detailed explanation.

- Embarrassing questioning: This was followed by interrogation under torture (the embarrassing (i.e. painful) questioning of the accused), which often resulted in a "confession". Any “protective regulations” such as limiting torture to one hour, breaks during torture, etc. were mostly ignored. In the context of witch trials, the use of torture was usually no longer limited to one hour, as a crimen exceptum (exceptional crime ) was assumed, which required particular severity. Here came inter alia. Thumb screw and rack used. Likewise, in witch trials, the usual rule that a defendant could only be subjected to torture three times and if there was no admission that he was to be released was often not applicable. In the Hexenhammer it was advised to declare the prohibited resumption of torture without new evidence as a continuation .Water sample, title page of the writing by Hermann Neuwalt , Helmstedt 1581

- Witch Trials: The official court proceedings did not provide for a witch trial , in fact, their use was actually prohibited. However, many courts used them in various parts of the Holy Roman Empire . The evaluation of the witch samples was just as varied as their application in general. Sometimes the witch trials were seen as strong evidence, sometimes as weak evidence. The following witch samples are the best known:

- Water sample (also known as witch bath)

- Trial by fire (but this was extremely rare)

- Needle sample (the so-called witch's mark was searched for here)

- Tear test

- Weighing sample

- Confession: In the early modern period, no one was allowed to be convicted without a confession - this also applied to the witch trials. However, due to the rules governing the use of torture, the likelihood of obtaining a confession was many times higher in witch trials than in other trials.

- Questioning about complicit parties ( statement ): Since, according to witch doctrine , the witches met their fellow comrades on the witch sabbaths, they had to know them too. In a second phase of interrogation, the accused were asked about the names of the other witches or sorcerers, possibly with renewed use of torture. As a result, the list of suspects grew longer and longer, as more and more people were accused of being witches under torture. The result were real chain processes.

- Condemnation

- Execution: The crime of witchcraft was punished by fire death, i.e. the pyre on which one was burned alive in order to purify the soul . The witch was on a pole in the midst of a brushwood pile tied , then the kindling pile was ignited. As an act of grace, beheading, strangling or hanging a gunpowder sachet around the neck was considered to be an act of grace.

Example of a recorded protocol about a witch trial against the " Bader-Ann " in Veringenstadt in 1680.

victim

Number of victims

According to more recent research and extensive evaluations of the court files, Schwerhoff assumes that the persecution claimed around 40,000 to 60,000 deaths across Europe. Around 25,000 people were executed on the soil of the Holy Roman Empire , around 9,000 of them in southern Germany and in the Thuringian region, according to the research status of 2006, 1,565 (when the number of unreported cases was estimated to be low). In addition, there were a large number of others convicted of confiscation and imprisonment. The previously popular figures of several 100,000 fatalities were based on exaggerated estimates and the image of an unbridled witch hunt spread through literature and films. The false death toll of nine million of executed witches goes on Quedlinburger City Counsel Gottfried Christian Voigt back (1741-1791). It was taken up by Mathilde Ludendorff for national and Nazi propaganda and is still cited as a historical fact in some publications today.

gender

About 75 to 80 percent of the victims of the European witch hunt were women, which corresponded to the gender-based belief in witches in Central Europe. There could be regional deviations. The witchcraft concept in Northern Europe, for example, was based more on male witchers, which can be seen from the fact that men were convicted equally or predominantly. That was between 50% in Finland and up to 90% in Iceland, also in the archbishopric Salzburg two thirds of the convicted persons were male (133 executed beggars, mostly children around the Schinderjackl in the years 1675 to 1681). Men were also persecuted who allegedly could turn into werewolves with the help of a special belt .

Wise women

Probably in the 19th century the idea developed that the witch hunt was an organized suppression or destruction of pre-Christian cults practiced by wise women. The thesis was later taken up first by the völkisch movement , then also by feminism of the 1960s and 1970s, and today forms the basis of various neo-pagan and spiritual-feminist movements. The Bremen social scientists Gunnar Heinsohn and Otto Steiger put forward the thesis that the persecution of witches was a method with which traditional, secret knowledge of contraception was suppressed in order to protect the population of the newly emerging territorial states . In the scientific witch research this work was rejected. The assumption that the authorities and the church controlled the witch hunt centrally is considered a conspiracy theory .

Social structure

In the early days it was mainly women living alone, elderly and socially disadvantaged from a rural environment who were victims of the witch hunts. From around 1590, with the change in the witch stereotype, the social class of the persecuted also changed, which is clear from victims such as the Arnsberg mayor Henneke von Essen . There is evidence that there was a deliberate attempt to imply noble and high-ranking people, possibly because it was hoped that they could use their influence to end the wave of persecution. In addition, there were certainly personal reasons such as envy, jealousy or the like for denouncing someone as a witch; but the real belief in the power of witches should not be underestimated. The mayor Johannes Junius , who was burned in Bamberg in 1628, wrote a letter to his daughter Veronika in captivity, in which he described how the executioners asked him to confess something he had thought up, even if he was completely innocent.

Last witch trials

The last victim of the witch hunt in Brandenburg was the 15-year-old maid Dorothee Elisabeth Tretschlaff on February 17, 1701, who was beheaded in Fergitz in the Uckermark for "bullying with the devil". There were other trials that ended in acquittals. In 1714, King Friedrich Wilhelm I had the fire piles torn down after the witch trials had been removed from the witch trials in 1708 by stipulating that judgments on the use of torture had to be confirmed by the king personally in individual cases.

On August 19, 1738, in the last witch trial on the Lower Rhine, Helena Curtens, only 14 years old at the time of their arrest, and Agnes Olmans (mother of three daughters) were executed by burning in Düsseldorf-Gerresheim for "witchcraft and loverhood" with the devil .

In southwest Germany, Anna Schnidenwind was one of the last women accused of witchcraft on April 24, 1751 in Endingen am Kaiserstuhl . Probably the last execution of witches on Reichsboden took place in Landshut in 1756 : on April 2, 1756, 15-year-old Veronika Zeritschin was burned as a witch after she was beheaded.

On April 4, 1775 in Kempten Prince pen Anna Maria Schwegelin for sex with the Devil made the process as the last "witch" in the area of today's Germany. The verdict of the Prince Abbot Honorius Roth von Schreckenstein , who by virtue of imperial privilege (Campidona sola judicat ense et stola) was entitled to spiritual and secular jurisdiction , was not enforced, as the Prince Abbot ordered the investigation to be restarted a few days before the enforcement. However, the case was not pursued further, so that Anna Schwegelin died of natural causes in the Kempten prison (Stockhaus) in 1781 .

Even later, in 1782, Anna Göldi was the last Swiss witch to be executed in Glarus , although terms such as “witchcraft” or “sorcery” were avoided in the judgment. It was the last legal execution of witches to be carried out in the reformed Swiss canton of Glarus, to the horror of the Protestant public. It aroused outrage across Europe. In 1783 the council of Stein am Rhein started an investigation against four men who were suspected of sorcery and witchcraft.

The last recorded execution of a witch in Central Europe took place in South Prussia in 1793 . Wilhelm G. Soldan and Heinrich Heppe wrote in their fundamental work "Without a doubt this was the last judicial witch burn [...] that Europe saw in the eighteenth century". It is unlikely that the trial actually took place. Information about this comes only from one and also quite uncertain source. However, it was certainly not the final "judicial" treatment of witchcraft.

Witch bull

Pope Innocent VIII published the bull Summis desiderantes affectibus in 1484 , the formulation of which probably goes back to the notorious inquisitor Heinrich Kramer . Although this is a document stating the necessity of the Witch Inquisition in Germany and authorizing Kramer to pursue his witches, historians agree that the use of this document in other cases prevented the outbreak of a witch craze, as in Italy was the case where the Pope could prevail. The witch bull had to owe its relatively high degree of popularity to Heinrich Kramer, who put it in front of the actual text of the witch hammer .

Witch hammer

The witch's hammer , Malleus maleficarum , published in 1486, played an important role in popularization , in which the Dominican and failed inquisitor Heinrich Kramer summarized his ideas about witches and tried to back them up with dozens of church fathers' quotes. Although his work never achieved ecclesiastical recognition - even if the author tried to suggest this by placing the papal bull Summis desiderantes affectibus in front - and was therefore not a basis for ecclesiastical procedures and never replaced secular jurisprudence, it nevertheless had an effect on ideas such as legal practice the end.

Luther's attitude to the witch hunt

In his sermons, lectures, table speeches and letters, Martin Luther has expressed himself in many ways on the subject of “sorcery” and “witches” over the past three decades. Luther was convinced of the possibility of the devil's pact, the devil's compensation and the magic of damage and advocated the judicial prosecution of wizards and witches.

The statement of the Old Testament "You should not let the sorceresses live" ( Ex 22.17 LUT ) was valid for him. This becomes clear in a witch's sermon that Luther gave on this point. Here he expressed his disgust for the evil of witchcraft and agreed to condemn the suspected women:

“From the sorceress. ... Why does the law tend to name women rather than men, even though men also violate it? Because women are more subject to Satan through seductions (superstitionibus) than they are. Like Eve. ... It is a very just law that sorceresses should be killed, because they cause a lot of damage, which is sometimes ignored, namely they can steal milk, butter and everything from a house ... They can bewitch a child ... They can also have mysterious diseases produce in the human knee that the body is consumed ... When you see such women, they have diabolical forms, I've seen some ... That's why they must be killed ... They cause damage to bodies and souls, they give potions and incantations to arouse hatred, love, storms, all the devastation in the house, in the field, over a distance of a mile and more, they make limps with their magic arrows so that no one can heal ... The sorceresses are to be killed because they are thieves , Adulterers, robbers, murderers ... they harm in many ways. So they should be killed, not only because they harm, but also because they have dealings with Satan. "

Numerous Lutheran theologians, preachers and lawyers and sovereigns, for example Heinrich Julius von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel , later referred to relevant statements from Luther.

Calvin and the witch trials

Just like Luther, John Calvin advocated the persecution and execution of witches. With reference to the Bible passage Exodus 22:17 LUT , Calvin explained that God himself had determined the death penalty for witches. In sermons he therefore reprimanded those who refused to burn witches, and wanted to cast them out of society as despisers of the divine word.

Calvin believed that men and women in Geneva had used magic to spread the plague for three years, and held all the self-accusations pressed from them through torture to be true, and retrospectives to be untrue.

Canisius and the persecution of witches, especially in Catholic areas

The eloquent counter-reformer and religious provincial of the Jesuits for southern Germany, Petrus Canisius , was also an advocate of the persecution of witches. In sharp pronouncements between 1559 and 1566, as cathedral preacher in Augsburg, he made “witches” responsible for all kinds of “shameful outrages” and “devil's arts”. This contributed to a change in mood in favor of the proponents of persecution in Augsburg, which had previously been more cosmopolitan and humanistic, and encouraged the rural population in their desire to persecute women who were unpopular or considered peculiar. After a latency phase of two generations, Canisius' sermons caused great damage in the minds of many people in the southern German Catholic area. Wolfgang Behringer sees the sermons given by Petrus Canisius in the 1560s as one of the reasons for the subsequent new outbreak of the witch craze in Central Europe. Canisius biographer Mathias Moosbrugger shares this view .

The fight against the witch hunt

The criticism of the witch hunt began almost immediately with the onset of modern persecution. For example, in 1519 Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486–1535) in Metz successfully defended a woman accused of witchcraft before the inquisitor Claudius Salini.

Initially, there were concerns, especially from the legal and administrative side, about the creation of a special jurisdiction alongside the state judicial organs. Fundamental criticism of the superstition in witches only began later.

Doubts about magic arts and criticism of the litigation

The interpretation of weather anomalies, which in popular beliefs were attributed to witches and wizards, in the " Little Ice Age " had a not inconsiderable influence on the development of intellectual history. Especially in the area around the University of Tübingen , a number of theologians and lawyers expressed themselves critical of the belief in witches, because one saw God's omnipotence so comprehensively that there can be no weather magic or damage magic : Ultimately, misfortune, misfortune and storms are also directed by God himself, to punish sinners and try the righteous. Damage magic, witch flights and witches dance are diabolical imaginations. Witches could only be punished by the pact of the devil because of their apostasy from God .

To this group from the environment of the Tübingen University belonged:

- Martin Plantsch (around 1460–1533) from Dornstetten , from 1477 to 1533 in Tübingen, regarded magic as an imagination as early as 1507, two years after a witch was burned in Tübingen; the work of witches could not be combated because it was under God's will: "This is the first general truth: No being can harm another or produce any actual effect on the outside, unless by the will of God" .

- Johannes Brenz (1499–1570) from Weil der Stadt , 1537 to 1538 in Tübingen, denied the responsibility of witches for a large hailstorm in 1539, but considered their punishment to be justified if they imagine themselves and have the bad intention of joining the covenant to face the devil.

- Matthäus Alber (1495–1570) from Reutlingen , 1513 to 1518 in Tübingen, and Wilhelm Bidembach (1538–1572) from Brackenheim , in the mid-1550s in Tübingen, preached in Stuttgart in 1562 after a large hailstorm against the Esslingen pastor Thomas Naogeorg (1508 –1563), who blamed witches for it and demanded that they be severely punished.

- Jakob Heerbrand (1521–1600) from Giengen an der Brenz , 1543 to 1600 in Tübingen, presented the disputation thesis on Ex 7 : 11–12 LUT in 1570 that people can neither do magic nor make weather, and let his pupil do this Nikolaus Falck (1540–1616) defend: “One must not think that these words of the 'magicians' have such a great effect or that they have the power to accomplish such things” - but they are “phantasmata” that Satan pretends no real substantial changes in nature or damage to people, because only God's word can actually work creatively.

- (Theodor) Dietrich Schnepf (1525–1586) from Wimpfen , 1539 to 1555 and 1557 to 1586 (with interruptions) in Tübingen, turned around 1570 in sermons against the belief in witches.

- Jacob Andreae (1528–1590) from Waiblingen , 1541 to 1546 and 1561 to 1590 in Tübingen.

- Johann Georg Gödelmann (1559–1611) from Tuttlingen , 1572 to 1578 in Tübingen, presented disputation theses for Marcus Burmeister as a lawyer in Rostock in 1584 , in which he considered magic to be “the devil's web, deceit and fantasy” and the strict observance of the procedural rules demanded. In 1591 he published a corresponding three-volume work on dealing with witches.

- David Chytraeus (1530–1600) from Ingelfingen , 1539–1544 in Tübingen, published a Low German text by Samuel Meiger (1532–1610) on the persecution of witches in 1587 and in the foreword spoke out in favor of extreme restraint in the persecution.

- Wilhelm Friedrich Lutz (1551–1597) from Tübingen, from 1567 to about 1576 at the University of Tübingen, spoke out against the witch trials in Nördlingen from 1589 in harsh sermons.

- Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) from Weil der Stadt , 1589–1594 in Tübingen, defended his own mother, who was accused as a witch, from 1615–1620 with the help of a legal opinion, which was probably based on his friend Christoph Besold (1577–1638), 1591 to 1598 and from 1610 to 1635 in Tübingen.

- Theodor Thumm (1586–1630) from Hausen an der Zaber , 1604 to 1608 and 1618 to 1630 in Tübingen, restricted the criminal liability of witchcraft in his disputation theses for Mag. Simon Peter Werlin in 1621 and pleaded for help for women deceived by the devil .

- Johann Valentin Andreae (1586–1654) from Herrenberg , 1601 to 1614 (with interruptions) in Tübingen, generally rejected pyre as a punishment for witches.

In other regions, too, there was criticism of witch trials as early as the 16th century. B. on the sentence imposed. For example, Anders Beierholm (approx. 1545–1619) from Skast , from 1569 to 1580 Lutheran pastor in Süderende on Föhr , rejected the death penalty for sorceresses and tried to ensure that the bailiff of the island no longer allowed witches to be burned. As a result, Beierholm was accused of sorcery himself by his opponents and, in 1580, deposed as pastor on Föhr.

General rejection of the witch trials

The doctor Johann Weyer (1515 / 16–1588) had a significant moderating influence with his work De praestigiis daemonum (“From the dazzling works of demons”) , published in 1563 . He accused Brenz and others of inconsistency: if there was no magic spell, witches should not be punished either. The (well-reformed) doctor Weyer also argued against the belief in witches based on the omnipotence of God. He was legally influenced by Andrea Alciato (1492–1550) and the humanistic law school of the University of Bourges .

Immediately after the publication of Weyer's book, Duke Wilhelm V von Jülich-Kleve-Berg (1516–1592), Elector Friedrich III. von der Pfalz (1515–1576), Count Hermann von Neuenahr and Moers (1520–1578) and Count Wilhelm IV. von Bergh-s'Heerenberg (1537–1586) from further torture and application of the death penalty; Count Adolf von Nassau (1540–1568) also represented Weyer's opinion. Christoph Prob († 1579), the Chancellor of Frederick III. von der Pfalz, Weyer's view defended in 1563 at the Rhenish Electoral Congress in Bingen . However, witch hunts in these territories were not stopped permanently, but flickered again later.

In 1576, the execution of Catharina Hensel from Föckelberg , who had been convicted of being a “sorceress”, was canceled because she revoked her torture-extorted confessions and protested her innocence at the place of execution. The executioner refused to carry out the execution for reasons of conscience, and the bailiff of Wolfstein and Lauterecken , Johann Eggelspach (Eigelsbach), broke off the execution. Count Palatine Georg Johann I von Veldenz-Lützelstein (1543–1592), who hired Weyer's son Dietrich as senior bailiff in 1581/82 , commissioned three expert opinions from lawyers at the Speyer Imperial Court, including one from Franz Jakob Ziegler, who was under Weyer's influence as a senior expert in 1580 recommended dismissal against a guarantee (sub cautione fideiussoria) and the imposition of costs on the denouncing community.

The Reformed doctor Johannes Ewich (1525–1588), who condemned torture and water testing in 1584, and the Reformed theologian Hermann Wilken (Witekind) (1522–1603) thought similarly to Weyer in the pseudonym published in 1585: Christian bedencken and the reminder of magic or the Catholic Theologian Cornelius Loos (1546–1595) in his treatise De vera et falsa magia from 1592.

The English doctor Reginald Scot (before 1538-1599) published the book The Discoverie of Witchcraft in 1584 , in which he explained magic tricks and explained the persecution of witches to be irrational and unchristian. King James I (1566–1625) had Scots' books burned after taking office in England in 1603.

The reformed pastor Anton Praetorius had already campaigned as a princely court preacher in Birstein in 1597 for the end of a witch trial and the release of women. He railed against the torture to such an extent that the trial ended and the last prisoner still alive was released. This is the only recorded case of a clergyman demanding and enforcing the end of the torture during a witch trial. In the documents it says . "Because the pastor alhie hefftig dawieder been that you tortured the women ALSs it is deßhalben dißmahl been underlaßen" The first reformed pastor published Praetorius under the name of his son John Scultetus 1598 the book of witchcraft vnd wizards Thorough Report against the witchcraft madness and inhumane torture methods. In 1602, in a second edition of the Thorough Report, he took the courage to use his own name as an author. In 1613 the third edition of his report appeared with a personal foreword.

The Urgent Subjects Wemütige Klage Der Pious Invalid by Hermann Löher did not appear until 1676 after the end of the harshest wave of persecution, but is significant because the author himself was more or less a volunteer in the persecution apparatus in the 1620s and 1630s, and only because of this had become an opponent of persecution. In this respect, it offers an insider perspective on the course of the process and the power relationships behind it, which is not found in the same way with the other opponents of the persecution.

Before the Age of Enlightenment, the Jesuit Friedrich Spee von Langenfeld , professor at the Universities of Paderborn and Trier and author of the writing Cautio Criminalis (legal concerns about the witch trials) from 1631, was the most influential author who attacked the witch trials. He was appointed as confessor for the convicted witches and in the course of his work gained doubts about the witch trials as a means of finding guilty parties. For fear of being portrayed as the protector of the witches and thus strengthening the party of Satan, he published it anonymously. His book was the answer to the standard work on the theory of witchcraft from his Rinteln professor colleague Hermann Goehausen Processus juridicus contra sagas et veneficos from 1630.

In 1635, pastor Johann Matthäus Meyfart , professor at the Lutheran theological faculty in Erfurt, turned to his work “Christian Remembrance, To Powerful Regents, and Conscientious Predicants,” how to eradicate the hideous vice of witchcraft with seriousness, but in pursuit of the same, to open up Cantzeln to act very modestly in court houses ”against witch trials and torture.

The evangelical lawyer and diplomat Justus Oldekop turned openly and decisively not only against the "hideous and barbaric procedure" of the proceedings themselves, but with a remarkably modern-looking conviction he spoke out against the well-founded witch madness behind it - only shortly after Friedrich Spee and thus Decades before the actual Enlightenment.

When the persecution of witches had already become rare around 1700, the German lawyer Christian Thomasius published his writings against the belief in witches . He observed that the defendants only “confessed” when they could no longer endure the agony of torture . On the basis of the book De crimine magiae , which he wrote on this subject in 1701, King Friedrich Wilhelm I (Prussia) issued on December 13, 1714 a ministerial v. Plotho worked out a mandate that restricted the witch trials to such an extent that there were no further executions.

However, at the beginning of the 18th century , the famous physician Friedrich Hoffmann from Halle was still convinced of the possibility of the attachment of diseases by witches in connection with the supernatural powers of the devil .

The process of rethinking was completed in the times of the Enlightenment. With the turning away of legal practice from the oath and divine judgment towards provability, the unprovability of supernatural damage led to the fact that the witchcraft accusations were no longer investigated, although parts of the population continued to demand this for a long time.

Reactions from the church

- In 1997 the Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria published a statement on the responsibility of the Church in the witch trials.

- Church services for the victims of the witch hunt were held in many cities.

- In the Mea culpa forgiveness request of Pope John Paul II in the Holy Year 2000 , Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger , Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith , uttered the words: that people of the Church in the name of faith and morality in their necessary commitment to protection have resorted to methods inconsistent with the gospel to deal with the truth . This is interpreted in commentaries as an apology by the Church for the witch hunts, although the word "witch trial" is not mentioned.

- In 2000, the German Dominicans explicitly named their predecessors' mistakes in the witch hunt; see “Dominicans and Inquisition Today” .

- Ruedi Reich , President of the Church Council of the Evangelical Reformed Church of the Canton of Zurich , demanded on September 9, 2001 about the Wasterking witch trial: The events of 1701 are an injustice, which the Reformed Church of Zurich also has to face. Here people have sinned against the gospel because they have sinned against defenseless people.

- Statement by Salzburg Archbishop Alois Kothgasser in 2009 on the trial of the "witch" of Mühldorf 1749/50: The judicial murder of Maria Pauer, who was convicted as a "witch" in the last trial of this kind on the soil of the archbishopric of Salzburg at that time, is a horrific one Crimes in which the church of that time is not only interwoven because of the people involved. There is nothing to gloss over it, but to face the inhuman historical reality and to ask God and the people for forgiveness for this atrocity.

- In 2012 the Evangelical Lippe Regional Church issued a declaration on the subject of witch hunts.

- The Archbishop of Bamberg, Ludwig Schick, rehabilitated the victims of the witch trials in the Bamberg Monastery in 2012.

- Evangelical Church District Soest (Evangelical Church of Westphalia) for the persecution of witches November 20, 2013.

- Evangelical Church District Hattingen-Witten (Evangelical Church of Westphalia) 2014 for the rehabilitation of the victims of the witch trials.

- The Church Senate of the Evangelical Lutheran Regional Church of Hanover published a statement on September 18, 2015 about “the injustice, about the failure of theologians of the Reformation churches” when “innocent people were put to death” in the witch hunts, and it has a “social rehabilitation of the Victims of the witch trials ”.

- On February 17, 2016, on behalf of the Council of the Evangelical Church in Germany , its chairman, Regional Bishop Heinrich Bedford-Strohm , commented on the Church's joint responsibility in the witch trials and on the rehabilitation of the victims of the witch persecution the churches and many of their representatives are also guilty ”.

- In a mass on April 11, 2016, Pope Francis denounced the persecution of witches and the burning of heretics as injustice.

Reception history

The persecution of witches has repeatedly been a topic of both historical research and political discussion. In the Prussian Kulturkampf , the Catholic Church was accused as the sole author of the persecution of witches and the number of victims, up to 9 million, was clearly too high; at the moment it is assumed that around 40,000 to 60,000 dead (see number of victims ).

In the era of National Socialism primarily the exaggerated Rosenberg office and the Ahnenerbe the SS led by the witchcraft research. Alfred Rosenberg , for example, presented the belief in witches as an originally oriental and thus alien superstition that had been brought into Germany by the Catholic Church. On the other hand, the SS stylized the witches as representatives of an ancient Germanic religion that the church had opposed. The religious scholar Otto Huth saw the witch trials in the tradition of suppressing Germanic wise women: "The seer died - the Judaist priest moved in." Heinrich Himmler dramatized this view in a speech in Goslar in 1935 when he exclaimed:

"We see how the pyre flares up on which, after countless tens of thousands, the tortured and torn bodies of the mothers and girls of our people burned to ashes in the witch trial."

Himmler also endeavored to portray Jews and homosexuals, who are numerous in the Catholic clergy , as the backers of the witch hunt in terms of conspiracy theory . Both positions clearly had anti-clerical tips, but competed sharply with one another within the National Socialist polycracy . In 1935, Himmler tried with a “H [exen] special order” to assign sole responsibility for all further witch research in the Nazi state to the security service of the Reichsführer SS , but this only partially succeeded. The Reich Security Main Office , which was founded in 1939, had its own office for this purpose under Rudolf Levin , who had already started to set up an extensive witch card file the year before . The Austrian Germanist Otto Höfler pursued a different approach , who interpreted the witch hunt as an originally positive hunt for “female demons” by Germanic “ecstatic male societies”, which was later perverted by the church.

Under the auspices of feminism , the subject of witch hunts was increasingly taken up from 1980. Today, historical research on the topic focuses primarily on approaches to the history of the country and the region.

The Bremen social scientists Gunnar Heinsohn and Otto Steiger have interpreted the witch persecution in two very controversial books as a population policy: for the purpose of repopulation, to compensate for the dramatic population losses caused by the plague waves, the church and state criminalized birth control and, as the first measure of this policy, the female experts for birth control - the midwife witches - get persecuted. They cause mainly quotes from works that have been written to guide the witch hunts - the Malleus as well as a work of as witches theorists applicable Jean Bodin , La Démonomanie of Sorciers (lat. De Magorum Daemonomania , dt. From ausgelasnen raging Teuffelsheer ). Heinsohn and Steiger, on the other hand, did not look at witch trial files in detail. This view has found no approval among early modern historians.

The work of HC Erik Midelfort is considered to be a turning point in modern research into the persecution of witches in Germany and Europe . According to this, the persecution of witches was not only tolerated by the majority of the people. Instead of attributing the initiative to the ecclesiastical and secular authorities, according to Midelfort, witch hunts were essentially demanded by broad strata of the population and organized by hand. A tightly organized judicial apparatus, where it was effective in individual states, contributed considerably to preventing the grossest excesses.

Rehabilitation of victims of the witch hunt

A growing number of European cities have given official moral rehabilitation to those convicted of witchcraft since the 1990s.

Germany

- Bensberg : 1990 memorial plaque at the town hall of Bensberg for the women who were innocently mocked, tortured and executed as witches .

- Winterberg : Mayor Braun, local history and history association and representatives of the two churches inaugurated a memorial at the town hall on November 19, 1993. Winterberg was the first city in Germany to rehabilitate the victims of the witch trials.

- Veringenstadt : In 1994 the Strübhaus action group erected a sculpture in memory of Bader-Ann, who was executed as a "witch" . The unveiling took place during the Veringer forum “Hexenwahn. State of the art "on June 8, 1994. [1]

- Idstein : Inauguration of a memorial plaque on the Hexenturm on November 22, 1996 by Mayor Hermann Müller and representatives of the churches. On November 6, 2014, the Idstein City Parliament unanimously resolved the moral and socio-ethical rehabilitation of the victims of the Idstein witch trials.

- Kempten (Allgäu) : In Kempten, a fountain named after her with a memorial plaque on a plinth was inaugurated on the southeast side of the residential building of the former Benedictine abbey in Kempten as a memorial for Anna Maria Schwegelin . The construction of the fountain was initiated and financially supported by the Kempten women's list.

- Semlin : Mayor Alfred Mantau and the local advisory board declared the persecution of the Anna Rahns in 1672 wrong and unveiled the first witch memorial in the new federal states on July 27, 2002.

- Kammerstein and Barthelmesaurach on November 24, 2002 and November 23, 2003 by Mayor Walter Schnell and representatives of the churches.

- Bad Wildungen : On the Day of Repentance and Prayer in 2004, a rose was planted at the Evangelical City Church in Bad Wildungen and a memorial plaque was attached: “Resist evil, preserve the dignity of people! - Remembrance of the victims of the witch hunt ”.

- Eschwege : Mayor Jürgen Zick on behalf of the city and synod of the Evangelical Church District Eschwege on October 30, 2007.

- Hofheim am Taunus : Resolution of the city council on November 3, 2010.

- Rüthen , Hilchenbach , Hallenberg , Düsseldorf , Sundern (Sauerland) , Menden (Sauerland) , Werl and Suhl followed in 2011 .

- In 2012, the cities of Bad Homburg vor der Höhe , Rheinbach , Detmold , Cologne , Osnabrück and Büdingen announced that the victims of the local witch trials should be rehabilitated.

- On June 18, 2012, the city council of Lemgo declared that it had rehabilitated the victims of the witch trials with its resolution of January 20, 1992 to erect the “Stumbling Block” (monument to Maria Rampendahl - see photo).

- On February 27, 2013, the city council of Soest announced that the victims of the witch hunt would be rehabilitated.

- The Council of the City of Freudenberg (Siegerland) on April 19, 2013.

- On September 25, 2013, the City Council of Rehburg-Loccum passed a resolution on the socio-ethical rehabilitation of the victims of the witch trials.

- On October 30, 2013, the Lutherstadt Wittenberg Council announced a socio-ethical rehabilitation of the victims of the witch hunt.

- On December 18, 2013, the city council of Datteln unanimously passed the resolution to rehabilitate the victims of the witch trials in a socio-ethical manner. Many death sentences from Vest Recklinghausen were pronounced at Horneburg Castle .

- The Council of the City of Horn-Bad Meinberg : Social-ethical rehabilitation of the victims of the witch trials on April 10, 2014.

- Mayor Klaus Jensen of the city of Trier : Memorial event on April 30, 2014 for the victims of the witch persecution.

- Resolutions were passed by the city councils of Witten in 2014 and Dortmund in 2014 on the socio-ethical and moral rehabilitation of the victims of the witch trials .

- Schleswig : Memorial service with Mayor Arthur Christiansen and the Protestant cathedral community for the victims of the witch hunt on November 21, 2014.

- Lippstadt 2015, Wemding 2015, Blomberg 2015, Rottweil 2015

- Bamberg : On April 29, 2015, the city council passed a resolution on the witch trials in the Bamberg Monastery and decided on a text for a plaque on the memorial behind Geyerswörth Castle: “In the 17th century, around 1000 women, men and children were living in the Bamberg Monastery innocently accused, tortured and executed. "

- Gelnhausen 2015, Balve 2015, Bad Laasphe 2015, Barntrup 2015, Bad Saulgau 2015, Schlangen 2015, Gadebusch 2015, Hattersheim am Main 2015, Kriftel 2016, Schwerin 2016, Buxtehude 2016, Neuerburg 2016, Wiesensteig 2017, Bernau bei Berlin 2017, Ahlen 2017 , Marburg 2018, Sindelfingen 2019, Horb am Neckar 2019, Bodenheim : In its meeting on February 23, 2021, the municipal council decided to rehabilitate the citizens of Bodenheim who were wrongly tortured and killed during the witch hunt,

Switzerland

- In 2001, Ruedi Reich , President of the Church Council of the Canton of Zurich / Switzerland, theologically rehabilitated the victims of the Wasterking witch trial .

- August 27, 2008: The Glarus district administrator rehabilitated Anna Göldi , the “last witch of Europe”, as a victim of a judicial murder.

- 2013: Otto Sigg , historian and former head of the Zurich State Archives , has processed the original sources of the witch trials with death sentences in the city of Zurich in a book - between 1478 and 1701 these 75 women and four men lost their lives. From the location of today's memorial to the reformer Huldrich Zwingli at the Wasserkirche , those accused of witchcraft were transferred to the Wellenberg Tower, locked up and tortured before they were burned alive. Sigg therefore suggests placing a memorial plaque at this point.

- March 22, 2019 Canton of Basel-Stadt / Switzerland: Inauguration of the memorial plaque for the victims of the witch hunt. "The memorial plaque is to be understood as rehabilitation in the symbolic sense."

Rest of Europe

- October 31, 2004: The Scottish city of Prestonpans rehabilitated 81 executed women in the presence of descendants.

- 2012: Nieuwpoort / Belgium

- 2021: Lier (Belgium) (Antwerp Province)

America

- October 17, 1711: General amnesty for most of the convicts from Salem, Massachusetts , USA.

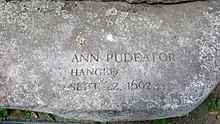

- In 1957 Ann Pudeator, hanged as a witch in Salem, was declared innocent.

- October 31, 2001: The governor of Massachusetts signed a declaration of innocence for the last five women in the Salem witch trials.

Memorial stones and plaques for the victims of the witch trials

In many places in Europe, politicians and the population suggested commemorating the victims of the witch trials in the form of monuments, memorial plaques and street signs. In Germany, memorial plaques commemorate the persecution of witches in around 100 municipalities.

Witch hunt today

distribution

The persecution of witches in the sense of people who supposedly perform harmful magic is in many countries and cultures, e.g. B. in Latin America, Southeast Asia and especially in Africa, still relevant at the beginning of the 21st century. Probably more people have been executed or killed for witchcraft since 1960 than during the entire European period of persecution. In Tanzania in East Africa alone, 100 to 200 cases of murders of alleged witches and wizards have been reported every year since the 1990s. In South Africa, witch hunts became particularly important through the Comrades , a youth organization of the ANC , since the mid-1980s. Since the liberation, witch hunts have increased again in the 1990s, and the annual number of victims is estimated at several dozen to hundreds.

In West Africa , witches were blamed for an epidemic in the 1970s. Instead of initiating vaccination programs, the government let old women broadcast confessions on the radio that they had taken the form of tawny owls to steal the souls of sick children.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the cases of so-called witch children in the Congo have received special attention. The aggression against children as the alleged cause of the disease AIDS and the death of their parents is apparently on the rise. Identical reports can be heard from Nigeria , Benin and Angola. In some countries in Africa - e.g. B. in Cameroon , Malawi - legislation against witchcraft has been reintroduced since their independence, and there are corresponding discourses in almost all African countries. This is seen as an attempt to legalize witch trials in order to limit the uncontrolled persecution of the suspected persons. Most experts regard this goal as doomed to failure, and elementary principles of the modern constitutional state are disregarded: The courtroom can only serve public opinion, it is an extension of the lynch mob. Accusations and witch persecutions are also frequent in the Central African Republic, and especially in Kenya . The official Ghanaian politics to the closure of the local witches camps and return settlement of the refugee women ( Resettlement ) was non-governmental organizations so far unsuccessfully, according to.

The "reality of witchcraft" is tricky in the educational work: Because the rich and powerful are fundamentally assumed to have obtained their power through ritual murders and witchcraft, some actually see ritual murders as a means of attaining power. A tremendous healing and destructive power is ascribed to human body parts and blood. In Nigeria and South Africa up to a hundred ritual murders are uncovered every year or appropriately prepared corpses with missing genitals are found, which only fuels the belief in witches.

Further reports of epidemic witch hunts are known from Indonesia, India, South America and the Arab states.

- In many traditional ethnic groups of the South American lowlands, the murder of a witch or a wizard is an inevitable consequence of a fatal illness.

- In Indonesia, between December 1998 and February 1999 , after Suharto was deposed , around 120 people were murdered as witches.

- In India, 400 Adivasis were killed on charges of witchcraft between 2001 and 2006 in Assam state.

- In January 2007, three women in Liquiçá , East Timor, were accused of being witches. The women, aged 25, 50 and 70, were murdered and their homes set on fire. Three suspects were arrested by UN police. There are isolated cases of such lynching among the uneducated rural population.

- In Saudi Arabia , too , men and women are persecuted for suspicion of sorcery and women for witchcraft. Both offenses are punishable by the death penalty.

Legal protection

The modern witch hunts are now from the UNHCR the UN continuously criticized as massive abuse of human rights. According to the UNHCR reports, the socially weakest in society are affected: above all women and children as well as the elderly and outsider groups such as albinos and those infected with HIV . Poverty, hardship, epidemics, social crises and a lack of education promote the persecution of witches as well as the economic benefits of the persecutors and their leaders, often pastors or "witch doctors" Earning money, for example, from exorcisms or from the sale of body parts of the murdered.

A “well-founded fear of (witch) persecution” can be a reason for fleeing in the sense of the Geneva Refugee Convention . By moving to other parts of the country, however, social pressure and persecution such as genital mutilation or the persecution of witches could be avoided, although this would not offer complete security in view of the widespread family relationships.

International Day Against Witch Mania

The papal missionary organization missio launched the International Day Against Witch Mania, which was celebrated for the first time on August 10, 2020.

See also

literature

Bibliographies

- Wolfgang Behringer did not make the revised version (from 2004) of his history of witch research available online, but the first version from 1994: doi : 10.22028 / D291-23579

- In November 2007 the Dresden selection bibliography on witch research (DABHEX) (Gerd Schwerhoff) was updated for the last time ( PDF ). The status from 2001 is available as a PDF .

- Until 2012 the results of the Witchcraft Bibliography Project Online (Jonathan Durrant) are documented in the Internet Archive .

- Also from 2012 is the most recent title of the general bibliography on witch trials on the Witches Trials website in Kurmainz .

- The bibliography compiled by Johannes Dillinger extends until 2017 (see secondary literature).

- A bibliography was compiled by Klaus Graf for 2017 : https://archivalia.hypotheses.org/70415 .

- Only English-language title contains A Bibliography of the Early Modern Witch Hunts (Yvonne Petry) June 2018: https://www.academia.edu/36870512 .

- In June 2019 Burkhard Beyer and Christian Möller presented the first edition of their bibliography (including general titles) on the history of the witch persecution in Westphalia and Lippe ( PDF ).

Secondary literature

- Wolfgang Behringer: Witch hunt in Bavaria: Folk magic, zeal for faith and reasons of state in the early modern period . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-486-53903-5 .

- Wolfgang Behringer: Witches. Faith, Persecution, Marketing (Beck series 2082). Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-41882-1 .

- Rosmarie Beier-de Haan (Ed.): Hexenwahn - Fears of the early modern times. Accompanying volume to the exhibition of the same name at the German Historical Museum; Berlin ... Ed. Minerva Farnung, Wolfratshausen 2002, ISBN 3-932353-61-7 ( modified online edition ).

- Nicole Bettlé : When Saturn eats its children. Child witch trials and their importance as a crisis indicator. Peter Lang Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-0343-1251-6 .

- Matthias Blazek: Witch Trials - Gallows Mountains - Executions - Criminal Justice in the Principality of Lüneburg and in the Kingdom of Hanover. Ibidem, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-89821-587-3 .

- Rainer Decker: Witches. Magic, Myths and the Truth. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-89678-329-7 .

- Johannes Dillinger : Witches and Magic. (= Historical introductions. Volume 3). Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007; 2nd edition ibid. 2018. Additional material (bibliography from 2007 and sources): campus.de . Bibliography 2017 in the Internet Archive

- Jonathan B. Durrant: Witchcraft, Gender, and Society in Early Modern Germany. Brill, Leiden 2007, ISBN 978-90-04-16093-4 .

- Silvia Federici : Caliban and the witch. Women, the body and the primordial accumulation. Mandelbaum, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-85476-615-5 .

- Christoph Gerst: The witch trial. From recognizing a witch to judgment. AV, Saarbrücken 2012, ISBN 978-3-639-42732-5 .

- Christoph Gerst: Witch persecution as a legal process. The Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel in the 17th century. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-89971-970-3 .

- Peter Gbiorczyk: Magic belief and witch trials in the county of Hanau-Münzenberg in the 16th and 17th centuries . Shaker, Düren 2021. ISBN 978-3-8440-7902-9

- Thomas Hauschild , Heidi Staschen, Regina Troschke: Witches. Exhibition catalog. University of Fine Arts, Hamburg 1979.

- Claudia Kauertz: Science and belief in witches. The University of Helmstedt 1576–1626. 2001, ISBN 3-89534-353-6 .

- Michael Kunze: Road into the fire. About life and death in the time of the witch madness. Kindler, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-463-00838-6 .

- Joachim Lehrmann : Faith in witches and demons in the state of Braunschweig. Lehrmann-Verlag, Lehrte 2009, ISBN 978-3-9803642-8-7 .

- Erik Midelfort : Witch Hunting in Southwestern Germany 1562–1684. Stanford 1972.

- Brian P. Levack: Witch Hunt. The history of witch hunts in Europe (Beck'sche Reihe 1332). CH Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-42132-6 .

- Sönke Lorenz (Ed.): Himmler's Hexenkartothek. The interest of national socialism in the witch hunt. (Witch Research 4). Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 2000, ISBN 3-89534-313-7 .

- Monika Lücke , Dietrich Lücke: burned for their magic sake. Hunts of witches in the early modern period in the area of Saxony-Anhalt. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Halle 2011, ISBN 978-3-89812-828-5 .

- Friedrich Merzbacher : The witch trials in Franconia. 1957 (= series of publications on Bavarian national history. Volume 56); 2nd, extended edition: CH Beck, Munich 1970, ISBN 3-406-01982-X .

- Katrin Moeller: That arbitrariness takes precedence over law. Hunting of witches in Mecklenburg in the 16th and 17th centuries (Hexenforschung 10). Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-89534-630-9 .

- Lyndal Roper : Witch Mania. Story of a persecution. CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-54047-9 .

- Walter Rummel, Rita Voltmer: Witches and witch persecution in the early modern period. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2008, ISBN 978-3-534-19051-5 ; 2nd edition, ibid. 2012, ISBN 978-3534245857 .

- Andreas Schmauder (Ed.): Early witch persecution in Ravensburg and on Lake Constance. 2nd Edition. UVK, Constance 2017

- Rolf Schulte: Warlocks. The persecution of men as part of the witch hunt from 1530–1730 in the old empire (Kieler Werkstücke. Series G: Contributions to the early modern times, 1, also a dissertation at the University of Kiel, 1999). Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2001, ISBN 3-631-37781-9 .

- Gerd Schwerhoff : Witchcraft, Gender and Regional History. In: Gisela Wilbertz, Gerd Schwerhoff, Jürgen Scheffler (eds.): Witch persecution and regional history. The county of Lippe in comparison (= studies on regional history. Vol. 4). Bielefeld 1994, pp. 325-353.

- Gerd Schwerhoff: Criminal justice and justice from a historical perspective - the example of the witch trials. In: Andrea Griesebner, Martin Scheutz, Herwig Weigl (eds.): Justice and Justice - Historical Contributions (16th – 19th centuries). Studien-Verl., Innsbruck / Vienna / Munich / Bozen 2002, ISBN 3-7065-1642-X .

- Otto Sigg : witch trials with death sentence: judicial murders in the guild city of Zurich . 2nd Edition. Self-published, Zurich 2013, ISBN 978-3-907496-79-4 .

-

Wilhelm Gottlieb Soldan : History of the witch trials. Illustrated from the sources. Cotta, Stuttgart et al. 1843.

- Wilhelm Gottlieb Soldan, Heinrich Ludwig Julius Heppe : Soldan's history of the witch trials. Cotta, Stuttgart 1880.

- Wilhelm Gottlieb Soldan, Heinrich Heppe, Max Bauer : History of the witch trials. Parkland-Verlag, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-88059-960-2 .

- Wilhelm Gottlieb Soldan, Heinrich Heppe, Sabine Ries: History of the witch trials. Vollmer, Essen 1997, ISBN 3-88851-205-0 .

- Wilhelm Gottlieb Soldan, Heinrich Ludwig Julius Heppe : Soldan's history of the witch trials. Cotta, Stuttgart 1880.

- Manfred Wilde : The sorcery and witch trials in Saxony. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-412-10602-X .

- Manfred Wilde: Witch trials in the Anhalt principalities . In: On the way to a story of Anhalt. Announcements of the Verein für Anhaltische Landeskunde , 21st year 2012, special volume (conference proceedings). Köthen 2012, pp. 133–157.

- Werner Tschacher: The witchcraft stereotype as a conspiracy theory and the problem of the epoch boundary . In: Johannes Kuber, Michael Butter, Ute Caumanns, Bernd-Stefan Grewe, Johannes Großmann (eds.): From back rooms and secret machinations. Conspiracy theories in the past and present (In dialogue. Contributions from the Academy of the Diocese of Rottenburg-Stuttgart 3/2020). Pp. 39-58.

Source works

- Joseph Hansen: Sources and studies on the history of the witch madness and the witch hunt in the Middle Ages. C. Georgi, Bonn 1901 (reprint: Olms, Hildesheim 1963). (The representation of the historical development is out of date.)

- Heinrich Kramer alias Institoris: The witch hammer. Malleus maleficarum. Commented new translation. 5th edition. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-423-30780-3 .

- Friedrich Spee : Cautio Criminalis or legal concerns about the witch trials. From the Latin by Joachim-Friedrich Ritter. 8th edition. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-423-30782-6 .

- Nicolas Rémy : Daemonolatreia or devil service. UBooks-Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-86608-113-0 .

- Ulrich Molitor : Of monsters and witches. UBooks-Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-86608-089-8 .

- Hermann Löher : Wistful lament of the pious innocent. A lay judge criticizes the witch hunt. Taken from the Early New High German by Dietmar K. Nix. Cologne 1995, ISBN 3-9803297-4-7 .

- Friedrich-Christian Schroeder (Ed.): The embarrassing court order of Emperor Charles V and the Holy Roman Empire from 1532 (Carolina). Reclam, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-018064-3 .

Web links

- Thematic portal witch research at historicum.net

- Catalog Hexenwahn 2002

- Gabriele Gierlich: Handout for educators , 2009

- Rita Voltmer: witch hunts . In: The scientific-religious-pedagogical lexicon on the Internet, 2017

- Andreas Deutsch : “Witch hunt against famine? On the irrational handling of problems using the example of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) ” on YouTube , June 18, 2019 (video, Heidelberg University, 21:23 min.)

- Presentation by Wilhelm Liebhart

sources

- To the Mayor of Bamberg Johannes Junius :

- Interrogation protocol of Johannes Junius , digitized version of the manuscript RB.Msc.148 / 299 of the Bamberg State Library

- Letter from Johannes Junius to Veronika Junius , digitized version of the manuscript RB.Msc.148/300 of the Bamberg State Library