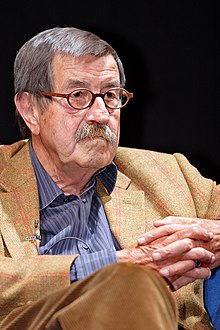

Günter Grass

Günter Wilhelm Grass (born on October 16, 1927 in Danzig - Langfuhr , Free City of Danzig , as Günter Wilhelm Graß ; died on April 13, 2015 in Lübeck ) was a German writer , sculptor , painter and graphic artist . Grass had belonged to Group 47 since 1957 and became an internationally respected author of German post-war literature with his debut novel Die Blechtrommel in 1959.

Grass' work and role as an author and political intellectual was and is the subject of extensive research and media interest at home and abroad. His main motivation was the loss of his homeland Gdansk and the confrontation with the National Socialist past, which is often reflected in his works. He often used his popularity as a writer to publicly comment on political and social events. For many years he was active and present in election campaigns for the SPD and the Greens . Grass' books have been translated into numerous languages and some have been made into films. In 1999 he received the Nobel Prize in Literature ; he was honored with numerous other awards.

resume

Origin and family

Günter Grass was the son of a Protestant grocer and a Catholic of Kashubian descent and spent his childhood in Gdansk in simple circumstances. The parents ran a grocery store in the Langfuhr district of Gdańsk (today: Wrzeszcz ).

Influenced by his Catholic mother, Grass worked as an altar boy among other things as a teenager . Initially not exactly enthusiastic about the Hitler Youth , he volunteered for the Wehrmacht in 1944 at the age of 17 - according to his own statements, in order to escape the tight family atmosphere .

Youth and military service

After deployments as an air force helper and in the Reich Labor Service , he was drafted into the 10th SS Panzer Division "Frundsberg" of the Waffen SS on November 10, 1944 at the age of 17 .

After being wounded on April 20, 1945 near Spremberg , Grass was taken prisoner on May 8, 1945 near Marienbad and was an American prisoner of war until April 24, 1946 . In his autobiographical story, The Skin of the Onion from 2006, he describes a fictional meeting with Joseph Ratzinger in Bad Aibling . Grass revealed himself as a member of the Waffen SS when he was captured, but kept this silent in his biographies, which were published until 2006. There it was always said that he had become an anti-aircraft helper in 1944 and then called up as a tank soldier in the Wehrmacht. In When Skinning the Onion , Grass revealed that he had volunteered for the Wehrmacht and was then drafted into the Waffen SS at the age of 17.

Since October 2014 the Günter-Grass-Haus in Lübeck has been showing “Grass as a soldier” as part of the permanent exhibition. Among other things, the route of the SS Panzer Division to which Grass belonged, as well as his prisoner-of-war files and photographs of the young person in 1944 in uniform of the Reich Labor Service are presented. A showcase shows pages from the original manuscript of Onion Skin , they illustrate the writing process. Klaus Wagenbach's diary notes from 1963 show that Grass told him about his membership in the Waffen SS.

Education and family

In 1947/1948 he completed an internship with a stonemason in Düsseldorf . He then studied graphics and sculpture at the Düsseldorf Art Academy from 1948 to 1952 under Josef Mages and Otto Pankok . He earned his living together with the later famous painter Herbert Zangs as a doorman in the restaurant Zum Csikós on Andreasstraße in Düsseldorf's old town. Later he immortalized Herbert Zangs, who like Grass was a soldier in the war, as Lanke's idiosyncratic painter in the tin drum. He continued his studies from 1953 to 1956 at the University of Fine Arts in Berlin as a student of the sculptor Karl Hartung . He then lived in Paris until 1959. In 1960 he moved again to Berlin-Friedenau , where he lived until 1972. From 1972 to 1987 he lived in Wewelsfleth in Schleswig-Holstein .

In 1954, Grass married the Swiss ballet student Anna Margareta Schwarz, and they had four children. He spent the period from the beginning of 1956 to the beginning of 1960 with Anna Schwarz in Paris and at times also in Wettingen , Switzerland, where the manuscript for The Tin Drum was written. In 1957 the twins Franz and Raoul were born there. In 1961, after returning to Berlin, the daughter Laura followed, in 1965 the son Bruno was born. In 1972 Günter and Anna Grass separated and they divorced in 1978. The actress Helene Grass , born in 1974, is the daughter of the architect and painter Veronika Schröter (1939–2012), with whom Grass was one in the 1970s had a long-term relationship. In 1979 Nele Krüger, Grass' daughter, was born with the editor Ingrid Krüger. In the same year he married the organist Ute Grunert, who brought two sons into the marriage. In the autobiographical novel Die Box , Grass lets his six biological children and Ute Grunert's sons appear as "his eight children".

From August 1986 to January 1987 Günter Grass lived with Ute Grunert in India , mostly in Calcutta .

Creative period and political activities

In the years 1956/57 Grass began to be active as a writer in addition to his first exhibitions of sculptures and graphics in Stuttgart and Berlin. In 1956 he made his debut as a poet, in 1957 as a playwright and librettist of ballets . Up until 1958 he wrote mainly short prose, poems and plays, which Grass classified as poetic or absurd theater. Even with his first novel The Tin Drum , which was written during his stays in France and Switzerland, Grass, who was only 31 years old at the time, had his literary breakthrough in 1959.

On February 19, 1967 , the members of Commune I, founded at the beginning of the year, moved into the apartment of his neighbor and friend in Berlin-Friedenau Uwe Johnson , who was currently in New York . It was Johnson's West Berlin studio and work apartment, which he maintained next to his actual apartment at Stierstrasse 3 and which he had sublet to Ulrich Enzensberger during his stay abroad . Johnson only found out about it from the newspaper. The " pudding assassination attempt " on US Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey was planned in the apartment . It was discovered, but led to extensive media coverage. At Johnson's request, Günter Grass had the police clear the apartment.

Following a reading by Grass at the Protestant Church Congress in Stuttgart in 1969, a former SS member committed suicide with potassium cyanide. It was about the father of the later journalist and political scientist Ute Scheub , who goes into the figure of "Manfred Augst" in Grass' diary of a snail .

In November 1971, Grass took part in a week of German culture in Tel Aviv and was received for an interview by Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir .

For decades, Grass supported the SPD in the election campaigns and as a speechwriter for Willy Brandt, to whom he was personally connected, among others. He only became a party member in 1982 and remained so until 1993. In 1965, 1969 and 1972 he took part in election campaign tours of the SPD. By means of open letters and speeches on political issues, he made himself heard in public beyond his literary work.

In 1974, Grass resigned from the Church in protest against the bishops' position on the question of the right to abortion and the demanded abolition of § 218.

Together with Heinrich Böll , Carola Stern and others, he published the magazine L'80 (Democracy and Socialism. Political and Literary Contributions) , which appears four times a year .

A collaboration with the jazz musician Günter Sommer from 1985 onwards produced several recordings on which the writer reads from his works to the percussion music of Sommer.

Günter Grass was the official supporter of the 1: 1 campaign. of the lesbian and gay association in Germany , which advocates equal rights and obligations in civil partnerships . In 1989 he signed the ADAC Ade campaign .

In 1996, Grass was a signatory to the Frankfurt Declaration on the Spelling Reform . Grass continued to use the tried and tested spelling in more recent works .

In 1997 he established the Foundation for the benefit of the Roma people , which awards the Otto Pankok Prize , in honor of his former teacher and as a commitment to the benefit of the Sinti and Roma .

In 1999 Günter Grass received the Nobel Prize for Literature for his life's work at the age of 72 . In 2005 he founded the Lübeck 05 authors' circle .

Grass was also active against nuclear power, e.g. B. at a reading in front of the Krümmel nuclear power plant in April 2011.

Günter Grass lived from 1987 until his death in Behlendorf in the Duchy of Lauenburg near the district town of Ratzeburg , about 25 kilometers south of Lübeck . The Günter-Grass-Haus is located in Lübeck with most of his original literary and artistic works.

Grass died on April 13, 2015 at the age of 87 in a Lübeck hospital as a result of an infection. He was buried on April 29, 2015 in the closest family circle at the Behlendorf cemetery. The central memorial ceremony took place on May 10, 2015 in the presence of Federal President Joachim Gauck in the Lübeck Theater, the main speech was given by John Irving . Schleswig-Holstein honored Grass with mourning flags on public buildings on that day.

Work and action

Motivation and role as a political writer

The intentions of Grass' works include “writing against oblivion” and the loss of his homeland, Danzig. His works address National Socialism or deal with its background and consequences for the Federal Republic. The works by Grass, which are set in the post-war period ( e.g. Im Krebsgang , 2002), deal with the subject of forgetting and guilt, but at the same time - as in the Rättin - question the reliability of personal and collective memories. According to the committee's justification for his Nobel Prize, he was honored for having "drawn the forgotten face of history in lively black fables."

Rebecca Braun noted in the literary works and political writings after 1970 a constant tendency of Grass to coordinate his permanent presence in the media public with the self-images he consciously inserted into his literary works. Similarly, Monika Shafi sees a constant tendency to consciously incorporate autobiographical aspects and to conceal them at the same time.

Stuart Taberners observes in the Cambridge Companion to Günter Grass a thoroughly democratic tendency in a complete work that was driven by Grass's departure from his youthful enthusiasm for National Socialism. As a public figure, he transferred his personal experience to the failure of the entire nation, but avoided unambiguous and one-sided determinations, literally As with all of Grass's work, and testament to the essentially democratic tenor of his literary texts, artistic endeavours, essays and speeches, Peeling the Onion tenders an invitation to its reader to think in shades of gray rather than in black and white .

Narrative works

The novel The Tin Drum (1959) is written in a very figurative language. It is about the infantile eccentric Oskar Matzerath, who describes the adult world from his "child's perspective" and, thanks to his tin drum, can also report on events in which he was not directly involved, such as the birth of his mother. He had found his style with the tin drum , in which Grass confronted historical events with his surreal, grotesque imagery for the first time. As one of the first German-speaking writers, he faced the events of the Second World War and made a conscious decision to use the objective description of the historical context. The Kashubian found by this inclusion in the world literature.

After reading from the as yet unpublished manuscript, Grass received the prize for the novel in 1958 from Gruppe 47 , of which he had been a member since 1957. In 1960 the jury of the Bremen Literature Prize wanted to award Grass for the tin drum, which was prevented by the Bremen Senate. The prize was not awarded this year and the following year. The Tin Drum in 1979 by Volker Schlöndorff filmed .

His second book, Katz und Maus (1961), which was also set in Gdansk during the Second World War and in which he told the story of the boy Joachim Mahlke, initially became the cause of a scandal. Mainly because of a "masturbation scene", the Hessian Minister for Labor, Public Welfare and Health Care applied to the Federal Inspectorate to index the amendment because of its immoral content. However, in response to protests from the public and other writers, the application was withdrawn. Two years later, the novel “ Dog Years” (1963) was the last work in the Danzig trilogy .

With The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising , another Grass drama appeared in 1966, which became his most famous play. It deals with the workers' uprising of June 17, 1953 in the GDR and the role of Marxist intellectuals. The main character of the "boss" is equipped with numerous features from Bertolt Brecht . Grass always protested against an interpretation that reduced the drama to an anti-Brecht play. In 1968 Grass published the book Letters Across the Border , a dialogue between the Czech writer Pavel Kohout and Grass on the subject of “Prague Spring”.

In 1969, Grass' novel appeared locally anesthetized . In it, the author distributed his own ( anarchist and social democratic) political views to various people, the focus being a dentist, who deal with current problems. It was the first time that Grass wrote on a current topic ( student movement ). Other books always had a strong reference to the past. In the USA the book was received with euphoria, while in Germany the critics were more reserved. After the publication of the story From the diary of a snail (1972), which describes the Bundestag election campaign in 1969, Grass temporarily withdrew from political life.

In 1977 Grass' novel Der Butt was published, which cemented his international reputation as an epic poet. Two years later, Grass published the story Das Treffen in Telgte . Some poets of the Baroque period met there in 1647 during the negotiations for the Peace of Westphalia . The meeting is largely in line with the customs of Group 47, which Hans Werner Richter set up 300 years later . The story is dedicated to Richter. The first sentence of Der Butt ("Ilsebill salted after.") Was voted the most beautiful first sentence in German-language literature by a jury of celebrities in 2007 .

A trip to Asia inspired Grass to be born in the head in 1980 or Die Deutschen die aus die aus , a narrative work which, among other things, deals with political events of the time. 1986 followed the prose work Die Rättin , which was filmed in 1997 and draws an apocalyptic feature about the suicide of mankind . In 1992 the story Doomsday was published , which shows Grass's efforts to reconcile the Germans with themselves and their eastern neighbors.

In 1995 Grass' novel A Wide Field was published . It takes place in Berlin between the construction of the Berlin Wall and reunification and is a panorama of German history from the revolution of 1848 to the present. The long-term effect of the novel, which has not diminished to this day, unfolded through the phrase about the GDR that has become a popular phrase: “We lived in a modest dictatorship.” Grass received the Hans Fallada Prize for this highly controversial, politically oriented book . The protagonist of the novel, Fonty is, to the alter ego of Theodor Fontane ajar and so runs the gamut from the 19th century to the present. The book was widely discussed in public, which, among other things, led to the fifth edition going to print after just eight weeks.

In 2002 the novella Im Krebsgang was published , which deals with the sinking of the ship Wilhelm Gustloff occupied with refugees at the end of the Second World War. Last dances , a collection of predominantly erotic poems and drawings , appeared a year later .

The Skinning of the Onion , an autobiographical book with no explicit genre, was published in August 2006. In this memory book, the author “skinned” himself by uncovering layers of his childhood memories. When exposing one of these “skins”, Grass caused a sensation by announcing, after more than 60 years, that in autumn 1944, at the age of 17, he had been drafted intothe Waffen SS . This fact became known to the public shortly before the book was published through an interview that Grass gave to the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung .

Lyric works

In addition to his novels, Grass wrote several volumes of poetry, which he supplemented with his own pictures and drawings. He later explained that he liked the lyrics most of all, from which he actually came. It appeared to him to be the clearest and clearest form of writing, and with which he could best question and measure himself. His literary career began in the spring of 1955 when he submitted poems to a poetry competition organized by the Süddeutscher Rundfunk and won third prize straight away. Returning from the award ceremony, he found a telegram from Hans Werner Richter inviting him to the Group 47 meeting in Berlin. His reading aroused Walter Höllerer's interest . As a result, Luchterhand-Verlag published its first book in 1956.

The advantages of the greyhurts sold only 700 times in the first few years, but critics judged the book quite positively as a “way to a realistic representation of everyday life”.

In Gleisdreieck , published in 1960, he deals with the tin drum that was just released at the time . In addition to large and gloomy charcoal drawings, there are 55 poems that very much incorporate reality or describe objects. He tells about Berlin.

In the next volume of poetry, Interviewed in 1967, Grass refers to two things in particular: the biographical and the political. He writes about personal experiences and processes the 1965 election campaign in which he stood up for the SPD and Willy Brandt .

In addition to some less eminent works (for example, love checked ) and some anthologies, Ach Butt, your fairy tale goes badly , was published in 1983 . In this work, the poems from the novels Der Flounder and Die Rättin were mainly brought together. In terms of content, they sometimes describe in detail food or the excrement (as a human end product ).

Grass' poems are realistically shaped, but often seasoned with typically sharp irony, like his shortest poem Glück :

An empty bus

crashes through the dead of night.

Maybe his chauffeur will sing

and be happy.

(The ironic key word of the poem is the word perhaps . In connecting a senseless event with a feeling of happiness on the part of the person involved in this event, it refers to religious, metaphysical speculations in which, despite a senseless earthly existence, there is speculation on happiness beyond.)

In 2012 Grass published the political poems What Must Be Said and Europe's Shame in various daily newspapers .

Grass as a politically active intellectual

Grass' first political intervention was an open letter to Anna Seghers in connection with the construction of the Berlin Wall on August 13, 1961. Konrad Adenauer's so-called Frahmrede in Regensburg on the same day prompted Grass to actively support the disparaged SPD politician Willy Brandt .

Grass's close relationship with Willy Brandt began with Brandt's meeting with Gruppe 47 in 1961. In 1965, he published the paperback book dich singe ich Demokratie - the praise of Willy - for hermann luchterhand . In the election years 1961, 1965, 1969 and 1972 he worked as a speechwriter for Brandt, among other things , and was on the stage himself as a speaker and supporter under the title “ It's up to you ”. In the book Diary of a Snail Grass reported biographically on his role in the election campaigns, parts of his correspondence with Brandt were also published. His own political goals were broken down into many small demands, such as the abolition of the 5% clause , which never came about.

In 1965, Grass and others founded the “Wahlkontor deutscher Writers” to support Brandt. In 1967 Günter Grass and Günter Gaus initiated the Social Democratic Voters' Initiative (SWI) in coordination with Horst Ehmke, in which numerous artists, journalists and intellectuals were also represented.

It was primarily about opening the SPD to non-party voters and less about integrating supporters into the party. Grass himself only became a member of the SPD in 1982, but left it again after ten years because of the asylum policy . A first open conflict with Willy Brandt came to light when he joined the grand coalition under Kurt Georg Kiesinger as Foreign Minister in 1966. The SPD thus achieved its first participation in government at federal level, the cooperation between former NSDAP members, resistance fighters and - in the case of Herbert Wehner - a former KPD functionary, who had fought bitterly among themselves since 1945, was a deep turning point and an important one the advent of the extra-parliamentary opposition risky historical compromise. In a letter to Brandt, Grass criticized this as a lousy marriage and publicly held up Kurt Georg Kiesinger's role as a follower in the Nazi regime. Grass dealt with his criticism later in the novel locally numb .

Grass welcomed Brandt's assumption of government in 1969 and tried to work abroad with Brandt and Erhard Eppler , which Brandt refused to the disappointment of Grass. In contrast to a number of other, especially journalistic members of the SWI, Grass never succeeded in assuming a political office. He commented on Brandt's kneeling in Warsaw on December 7, 1970 in several writings. When Brandt had to resign because of his espionage affair, Grass expressed disappointment and anger at his political teacher . The SWI itself increasingly lost momentum after Brandt's loss as a key figure of identification.

In 1990 Grass spoke out (in contradiction to Brandt) against German reunification and in favor of a confederation of the two German states. Among other things, he argued that the unified state that existed from 1871 to the Greater German Reich of National Socialism “was the prerequisite for Auschwitz that was created early on. It became the power base of latent anti-Semitism, also common elsewhere. ”This was criticized by Martin Walser as“ instrumentalizing the Holocaust ”.

In 1992, Grass terminated his SPD membership in protest against the asylum compromise . Nevertheless, Grass continued to be involved in SPD election campaigns, in particular in 1998, 2002 and 2005 for Gerhard Schröder, to whom, like Brandt, he was personally connected. As a result, Grass organized the Lübeck literary meeting , mainly with writers who had clearly spoken out in favor of a continuation of the red-green coalition before the 2005 federal election. In contrast to Group 47, however, no literary critics can take part in the meetings there.

Grass played an important role in various writers' associations. As a co-founder of the Association of German Writers (VS) , now in ver.di , Grass was one of the critics of the association's policy, which, in his opinion, under the chairmanship of Bernt Engelmann, was often too tolerant of Eastern European dictatorships. At the federal delegates' conference in Hamburg (September 24-26, 1987) he was elected to the federal executive board, but resigned at the 1988 congress in Stuttgart with the entire executive board because a discussion about alternatives to joining the association in the IG Medien - Grass had proposed its own authors' union under the umbrella of the DGB - it did not materialize. With him, the VS federal chairwoman Anna Jonas and around 50 other authors left the association. Grass had been a member of the PEN Center Germany since 1968 , of which he was Honorary President since 2009.

In 1985, Grass made his rejection of a visit to a Bitburg military cemetery by the then Federal Chancellor Kohl (CDU) and the American President Ronald Reagan . He described the Mohammed cartoons in Danish and French newspapers as deliberate provocation and with the words "Where does the West get this arrogance to pretend what has to be done and what not?" In April 2010, in a speech in Tarabya , Grass called for recognition of the genocide of the Armenians by the Republic of Turkey and in December 2010 he was one of the artists who - unsuccessfully - campaigned for the Israeli government to allow Mordechai Vanunu to leave the country to receive the Carl von Ossietzky Medal from the International League for Human Rights .

Belonging to the Waffen SS

When Grass announced in August 2006 that he had belonged to the Waffen SS at the age of 17 , an extensive debate began about his role as a moral authority in post-war Germany. He first talked about it in an interview on the occasion of the publication of his autobiographical work On Peeling the Onion .

In the book, Grass wrote that in his youth he would have seen the Waffen-SS “as an elite unit” and that “the double rune on the uniform collar” was “not offensive” to him. According to his own statements, he was not involved in any war crimes of the Second World War while he was a member of the Waffen SS , and he did not even fire a single shot. Because as a loader in the tank regiment of the 10th SS Panzer Division "Frundsberg" he was only entrusted with reloading, but not with shooting.

He had indicated his SS membership to the US Army when he was captured on May 8, 1945. Twenty years before Skinning the Onion , Grass had already announced his time with the Waffen-SS to several fellow writers, including the Austrian poet, author and director Robert Schindel, born in 1944, and Peter Turrini, who was also a playwright of the same age .

In response to the late admission of his membership in the SS, there were numerous, both critical and sympathetic comments. Charlotte Knobloch (former President of the Central Council of Jews in Germany ) saw Grass' confession as a PR measure and said: “The fact that this late confession comes so shortly before the publication of his new book suggests […] the assumption that this is a PR measure to market the work. ”The journalist and Hitler biographer Joachim Fest expressed his incomprehension“ how someone can constantly rise to the guilty conscience of the nation for 60 years, especially when it comes to Nazi issues - and only then admits that he was deeply involved ”. Various authors, especially those from the circle of the New Frankfurt School , covered Grass with violent polemics with regard to his person as well as the quality of his work due to the occasion dealt with here in the anthology "Literature as Torment and Gequalle. About the literary business intriguer Günter Grass" . On the other hand, it was argued in his favor that critics had strangely distorted Grass's political positions, for example Hannes Stein and Henryk Broder presented an interview statement imprecisely and ambiguously, if not falsified, with consequences. Stefan Reinecke pointed out in the taz that it was pretended "as if the author had concealed an unspeakable personal guilt - without there being any evidence for it." In addition, "Grass was pumped up to a size" that he never had. Klaus Staeck (President of the Academy of the Arts in Berlin) emphasized that “the artistic work and also its political and moral integrity are beyond doubt even after his confession”.

The withdrawal or return of awarded awards was also requested on various occasions. The Polish politician Lech Wałęsa initially demanded that Grass should lose his honorary citizenship of the city of Gdansk . The CDU politicians Wolfgang Börnsen and Philipp Missfelder asked him to return his Nobel Prize. After a letter of repentance to the city of Gdansk and Lech Wałęsa acknowledging the repentance, the discussion subsided. Wałęsa explicitly withdrew his criticism. The mayor of Gdańsk, Paweł Adamowicz , said that Grass's late confession did not change the quality of his literature or his merits for German-Polish reconciliation. The Nobel Prize Committee also ruled out the withdrawal of the Nobel Prize.

In November 2007, Grass brought an action for an injunction against the Random House publishing group , to which Goldmann Verlag belongs , through his lawyer . The lawsuit was aimed against the claim that Grass had volunteered for the Waffen SS in an updated version of the Grass biography of Michael Juergs published by Goldmann . There was no trial. Grass and Random House have agreed on a settlement, after which Jürgs pledged to change the disputed passage in a new edition to the effect that Grass wrote in his autobiography, the age of seventeen in the fall of 1944 for Waffen-SS Division "Frundsberg" been recruited to be. This also corresponded to the presentation by Robert Schindel, according to which Grass - after he had volunteered for the submarine troops and was not taken there - was recruited to the Waffen SS.

Observation by the Ministry for State Security of the GDR

In 2010, Kai Schlüter published a documentary entitled Günter Grass im Visier. The Stasi files . The documentation also contains comments from Günter Grass and contemporary witnesses. Schlüter prepares Grass' "Stasi" files in it. The Ministry for State Security (“Stasi”) began these acts shortly after the Wall was built in August 1961 . The State Security did not let Grass out of sight until autumn 1989, collected material about him and the group 47 and monitored him during his visits to the GDR. Grass was almost taken into (deportation) detention by the State Security in August 1961.

Relationship to the Springer Group

In order to put an end to the opposition between Group 47 and Axel Springer AG that had existed since 1967 , their CEO Mathias Döpfner made an advance at Grass in 2006. This continued to stick to the boycott of Springer newspapers decided by the group in October 1967. The writers feared a "restriction and violation of freedom of expression" and a "threat to the foundations of parliamentary democracy in Germany" by the group's market power.

After decades, Grass had indicated that he wanted to move away from the boycott if the corporation apologized for the hurtful manner with which the corporation's newspapers had followed Heinrich Böll's work . Grass agreed to receive Döpfner in his house in Behlendorf near Lübeck. The meeting took place on March 27, 2006. There was no information about the content of the conversation, but another conversation took place at the end of April 2006, which Grass and Döpfner again held in Behlendorf. Excerpts from the dispute moderated by the publicist Manfred Bissinger were printed in Spiegel (25/2006) in June 2006 . Although Grass stuck to his fundamental criticism of Springer-Verlag, his rejection was not something firmly established. He would like Döpfner to push through “a greater differentiation” in the publishing house. Döpfner declared himself ready "with a view to 1968 for the Axel Springer Verlag to conduct a self-critical revision".

The conversation was published in August / September 2006 by Steidl-Verlag under the title The Springer Controversy as a paperback.

Controversy over the poem What Must Be Said

On April 4, 2012, Grass' prose poem What needs to be said, published in the Süddeutsche Zeitung , sparked a broad social and media discussion. In this text he accuses Israel of endangering the "already fragile world peace " with its nuclear weapons and of planning a " first strike " against Iran "that could wipe out the ... Iranian people", and in the same context criticizes the delivery of German submarines to Israel . At the same time, Grass grapples with what he claims to be taboo on an uncontrolled nuclear arsenal in Israel . Disregarding this taboo would be judged as anti-Semitism .

The following day, Grass gave several interviews. Commenting on Israeli policy on the West Bank , he said : “There are few countries that disregard UN resolutions like Israel. It has been pointed out often enough by the UN that this settlement policy must end. It goes on. ”He went on:“ This omission, this cowardly ducking away, that already suggests loyalty to the Nibelung. 'Yes, no criticism of Israel' is the worst thing that can be done to Israel "and:" Israel is not only a nuclear power , but has also developed into an occupying power. "

After its publication, the poem was received negatively by the Israeli side, representatives of Judaism in Germany , German politicians and most of the German media, and in some cases criticized as anti-Israeli and anti-Semitic. On April 8, 2012, the Israeli government officially declared Günter Grass to be a persona non grata for legal reasons due to his membership in the Waffen SS and imposed an entry ban.

The reactions from the Israeli side have been described by part of the Israeli media as exaggerated and hysterical.

In May 2012, the German PEN center rejected an application to withdraw Grass's honorary presidency. Since the association has committed itself to freedom of the word, it will not comment on the content of the poem.

reception

Günter Grass' work is seen as an important part of the German literary canon . The novels, not just The Tin Drum , became known worldwide. Grass' debut, the Tin Drum, became the benchmark for his subsequent novels. According to an analysis by Heinz Ludwig Arnold , the German criticism was mixed. Heinrich Vormweg, for example, criticized Grass's obscene and sometimes blasphemous writing style. On the other side was Grass's representation of Gdansk his youth in a series of James Joyce ' Dublin , Marcel Proust's Combray , Faulkner Jefferson, Mississippi - Verewigungen a city or region as a literary monument - made and well recognized Grass give the then zeitgeist fit again. In contrast to Mann, Grass demythologized, deheroized and de-demonized the Nazi era. Authors such as John Irving and Salman Rushdie , among others, tied to his “ picaresque ” writing style . The latter also dealt in particular with Grass' processing of the loss of his homeland, which can be seen, for example, in Rushdie's novel Mitternachtskinder , which makes clear reference to the tin drum - for example in the processing of the birth scene, which in turn is based on an alienation of Goethean portrayal of his birth in poetry and truth is based.

His second novel, Dog Years , was accompanied by an extensive media campaign that had not yet been experienced in Germany. Even before it was delivered to the book market, Grass read sections on television, preliminary selections were discussed, and Der Spiegel turned the novel into a cover story. The novel Dog Years was Grass' breakthrough on the international stage. The international reception, beginning with a review in The Times Literary Supplement in 1963, was even more positive than the German reviews. After that, he had succeeded in dealing with National Socialism in a much better way than, for example, Thomas Mann in his 1948 Doctor Faustus .

The fame of Grass' outside of literary circles was reflected in a 1965 homestory in Life magazine, commented on by David E. Scherman . Its popularity is also demonstrated by the positive and extensive American media coverage of a reading tour of Grass' on the east coast of the USA in the same year. In Newsweek magazine, Grass was described as the author who brought German post-war literature to the international stage.

As a result, new releases of grass novels regularly became events in the book market and the media. His public impact is evident on the Cicero list of the leading 500 intellectuals in German-speaking countries, on which he ranked first in 2013. Grass' self-styling as a political author with mustache, reading glasses and a mouth that was always open to protest, as was his actually dominant role in post-war literature, was also viewed negatively. Stuart Taberners spoke frankly of Grass' tendency to stylize himself as a monument to himself in his later work .

Grass has repeatedly been the subject of parodies and caricatures. In 1986 Günter Ratte Der Grass appeared as a parody of Die Rättin . The work itself was rated quite negatively in German and foreign reviews, and Grass reacted extremely disappointed to the corresponding reviews. Grass' late work was overshadowed by his early successful works.

In 2012, the appearance of Grass' political poem Europa Schande in the Süddeutsche Zeitung was presented by Volker Weidermann in the FAZ as a scoop of the satirical magazine Titanic . Grass' political statements in poetry became the subject of ridicule in social networks and the subject of a veritable media farce.

In Vonne Endlichkait , his posthumous book from 2015, Grass is unusually self-deprecating.

Awards

Günter Grass was awarded in 1999 the Nobel Prize for literature, because he - so the jury - "drawn frolicsome black fables the forgotten face of history" ( English "[he is the author] Whose frolicsome black fables portray the forgotten face of history ” ). Grass has also received a number of awards, some of which are listed below.

In 1958, Grass received the sponsorship award from the Kulturkreis der deutschen Wirtschaft im BDI eV , and in 1965 he was awarded the Georg Büchner Prize , "for his work in poetry and prose, in which he boldly, far-reaching and critically depicts and shapes the life of our time." In 1967 he was awarded the Carl von Ossietzky Medal and in 1968 the Fontane Prize . In 1969 he received the Theodor Heuss Prize and in 1970 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences . In 1977 he received the Italian Premio Mondello . In 1988 the Hamburg Senate awarded him the Medal for Art and Science . In 1994 the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts awarded him its Great Literature Prize . In 1995 Grass was awarded the Hermann Kesten Medal , the following year with the Thomas Mann Prize of the City of Lübeck, the Samuel Bogumil Linde Prize and in 1996 the Hans Fallada Prize . In 1999 Spain honored him with the Prince of Asturias Prize for Humanities and Literature .

Günter Grass holds honorary doctorates from Kenyon College (1965), Harvard University (1976), Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan (1990), University of Danzig (1993), University of Lübeck (2003) and Free University of Berlin (2005) .

In 2006 he was awarded the International Bridging Prize, which he refused to accept because CDU local politicians questioned the decision of the independent German-Polish jury. He had also refused to accept the Antonio Feltrinelli Prize in 1982.

Grass has been an honorary citizen of his native Gdansk since 1993 and an honorary doctorate from the university there. In 2007 he received the Ernst Toller Prize .

The award of the Bremen Literature Prize , which was planned for 1960, failed due to the opposition of the Bremen Senate . In the same year, however, he received the German Critics' Prize .

The German astronomer Freimut Börngen suggested the name (11496) Grass for his asteroid, discovered in 1989 .

In 2005 Günter Grass received the Eckart Witzigmann Prize for the cultural topic of food in literature, science and the media.

In 2009 a Günter Grass Museum was opened in his hometown Gdansk .

In 2012, Grass was awarded the honorary title “European of the Year 2012” by the Danish European Movement (Europabevægelsen) . Among other things, his contributions to debates on European policy were recognized.

In 2013 Günter Grass and his wife Ute received the “Schleswig-Holstein Milestone” award from the Association of German Sinti and Roma e. V. - Schleswig-Holstein State Association for its many years of commitment to the Sinti and Roma minority.

During his lifetime, Grass had objections to a monument in his hometown, which is why only a bronze figure by Oskar Matzerath placed on a park bench reminded of the writer until his death near his birthplace in what is now the Wrzeszcz district (formerly Langfuhr ). On October 16, 2015, half a year after his death and at the same time his 88th birthday, a larger bronze figure of Grass - with a book and a pipe in hand - was placed on the other side of the park bench. It was built 13 years earlier, but was never set up, respecting the author's wishes.

According to his own statement, Grass was to receive the Federal Cross of Merit in the 1970s . However, he declined, stating that he was a citizen of a Hanseatic city (see also: Hanseatic League and Awards ). The real reason, however, was that many former National Socialists had also received the medal.

Works

Novels, short stories and short stories

-

Gdansk trilogy

- The tin drum . Novel. Luchterhand, Neuwied 1959.

- Cat and mouse . Novella. Luchterhand, Neuwied 1961.

- Dog years . Novel. Luchterhand, Neuwied 1963. ( Number 1 on the Spiegel bestseller list from October 9, 1963 to February 5, 1964 and from February 26 to March 3, 1964 )

- locally anesthetized. Novel. Luchterhand, Darmstadt and Neuwied 1969. ( No. 1 on the Spiegel bestseller list from September 29 to November 30, 1969 )

- From the diary of a snail novel. Luchterhand, Darmstadt and Neuwied 1972.

- The flounder . Novel. Luchterhand, Darmstadt and Neuwied 1977. ( No. 1 on the Spiegel bestseller list from August 22, 1977 to March 12, 1978 )

- The meeting in Telgte . Narrative. Luchterhand, Darmstadt and Neuwied 1979.

- Head births or the Germans die out . Narrative. Luchterhand, Darmstadt and Neuwied 1980. ( 1st place on the Spiegel bestseller list from June 30th to August 31st, 1980 )

- The she-rat . Novel. Luchterhand. Darmstadt and Neuwied 1986. ( No. 1 on the Spiegel bestseller list from April 7th to May 25th, 1986 )

- Prophecies of doom. Narrative. Steidl, Göttingen 1992.

- A broad field . Novel. Steidl, Göttingen 1995.

- My century . Narrative volume. Steidl, Göttingen 1999.

- In the crab . Novella. Steidl, Göttingen 2002. ( 1st place on the Spiegel bestseller list from February 18 to May 26, 2002 )

- When peeling the onion . Memories. Steidl, Göttingen 2006. ( No. 1 on the Spiegel bestseller list from August 28 to October 1, 2006 )

- The box. Novel. Steidl, Göttingen 2008.

- On the way from Germany to Germany. Diary 1990. Steidl, Göttingen 2009.

- Grimm's words. A declaration of love. Steidl, Göttingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-86930-155-6 .

- Vonne Endlichkait. Steidl, Göttingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-95829-042-6 .

- The Artur Knoff stories. Steidl Verlag, Göttingen 2019, ISBN 978-3-95829-292-5 .

Dramas

- The bad cooks. A drama. 1956.

- Flood. One piece in two acts. 1957.

- Uncle, uncle. A game in four acts. 1958.

- Ten minutes to Buffalo. A game in one act. 1958.

- The plebeians rehearse the insurrection . A German tragedy. 1966.

Poetry

- The virtues of the wind grouse . 1956.

- Track triangle. 1960.

- Asked. 1967.

- Collected poems. 1971.

- Novemberland. 13 sonnets. Steidl, Göttingen 1993.

- Last dances. 2003.

- Lyrical prey. 2004.

- Stupid August. 2007.

- What needs to be said . Single publication, 2012.

- Europe's shame . Single publication, 2012.

- Mayflies . 2012.

- Poetry album 302. Märkischer Verlag, Wilhelmshorst 2012, ISBN 978-3-943708-02-8 .

- You. Yes, you. Love poems. Selected by Katja Lange-Müller . Steidl Verlag, Göttingen 2019, ISBN 978-3-95829-520-9 .

Graphics, sculptures, sculptures

- The flounder. Plastic in the port of Sønderborg , Denmark.

- Drawings and writing. The pictorial work of the writer Günter Grass. Volume I: Drawings and Texts 1954–1977. Edited by Anselm Dreher . Darmstadt / Neuwied 1982

- Drawings and Writing II. Etchings and Texts 1972–1982. Edited by Anselm Dreher. Darmstadt / Neuwied 1984.

- In copper, on stone. The etchings and lithographs 1972–1986. Goettingen 1986.

- Graphics and plastic. Edited by Werner Timm. Regensburg 1987 (exhibition catalog).

- One hundred drawings 1955–1987. Exhibition catalog of the Kunsthalle Kiel. Edited by Jens Christian Jensen . Kiel 1987, ISBN 3-923701-23-3

- Mirror images. Color lithograph, 2006.

Others

- "O Susanna". A jazz picture book. Blues, ballads, spirituals, jazz. Pictures: Horst Geldmacher. German texts: Günter Grass. Music work: Herman Wilson. With an afterword by Joachim-Ernst Berendt . Cologne and Berlin: Kiepenheuer & Witsch 1959.

- with Pavel Kohout : Letters across the border . An attempt at an east-west dialogue. 1968

- About the obvious. Speeches - essays - open letters - comments. 1968.

- The scarecrows . Ballet Libretto (WP 1970)

- The citizen and his voice. Talking essays comments. 1974.

- Memorandum. Political speeches and essays 1965–1976. 1978.

- Learn resistance. Political counter-speeches 1980–1983. 1984.

- Show tongue. A diary in drawings. 1988.

- Talk about loss. About the decline of political culture in a united Germany. 1992.

- A bargain called DDR. Last speeches before the bells ring. 1993.

- Günter Grass, Ōe Kenzaburō : 50 years ago yesterday. A German-Japanese correspondence . 1st edition. Steidl Verlag, Göttingen 1995, ISBN 3-88243-386-8 , p. 108 .

- Talk about the location. 1997.

- Time to get involved. The controversy about Günter Grass and the laudation for Yasar Kemal in the Paulskirche (1998)

- From the adventure of the Enlightenment. Workshop talks with Harro Zimmermann. 1999.

- Günter Grass - Helen Wolff. Letters 1959–1994. Steidl Verlag, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-88243-896-7 .

- The shadow. Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tales - as seen by Günter Grass. Steidl Verlag, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-86521-050-3 .

- Uwe Johnson - Anna Grass - Günter Grass. The correspondence 1961–1984. 2007, ISBN 978-3-518-41935-9 .

- Martin Kölbel (Ed.): Willy Brandt and Günter Grass - The exchange of letters . Steidl Verlag, Göttingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-86930-610-0 .

- Günter Grass, Heinrich Detering : Lately - A conversation in autumn . Steidl Verlag, Göttingen 2017, ISBN 978-3-95829-293-2 .

Audio books

- Pen & flute. Birthday serenade Willy Brandt. Thirteen poems like impromptu compositions. Günter Grass speaks & Horst Geldmacher flutes. Vinyl record. NBB publisher o. J. [1963]

- Günter Grass: There is a choice. Speech in the 1965 Bundestag election campaign . Record. Production by Hermann Luchterhand Verlag o. J. [1965]

- Günter Grass… reads,… in Bremen,… answers,… about the person. CD-ROM. Editor Jörg-Dieter Kogel u. Kai Schlueter. Production by Radio Bremen / Steidl Verlag 1998.

- Günter Grass reads “My Century”. 6 CD. Editor Jörg-Dieter Kogel u. Kai Schlueter. Production by Radio Bremen / Steidl Verlag / Deutsche Grammophon, 1999.

- Heinrich Böll, Günter Grass: Speeches on the occasion of the award of the Nobel Prize for Literature 1972 and 1999. 2 CD. Editor Kai Schlueter. Production Radio Bremen / Deutsche Grammophon, 2000. Also in: Freipass. Forum for literature, fine arts and politics. Writings of the Günter and Ute Grass Foundation Vol. 2. Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag 2016. 2 CD supplements.

- Günter Grass: “I became famous when I was 32 years old.” An acoustic collage of original sounds. By Gabriele Intemann, Dorothee Schmitz-Köster a. Walter Weber. Production by Radio Bremen / Der Audio Verlag, 2001.

- Günter Grass, Günter “Baby” Summer: My Century. A text and sound collage. 2 CD. Editorial office Jörg-Dieter Kogel. Production by Radio Bremen / Steidl Verlag, 2001.

- Günter Grass reads “Im Krebsgang”. 9 CD. Production by Der Hörverlag, 2002.

- Günter Grass reads "Lyrische Beute". 140 poems from fifty years. 3 CD. Production by Steidl Verlag, 2004.

- Günter Grass, Helene Grass, Stephan Meier: Des Knaben Wunderhorn or The Other Truth. A literary-musical evening. 2 CD. Production by Steidl Verlag, 2004.

- Günter Grass reads “A wide field”. 24 CD. Editorial office Jörg-Dieter Kogel, Kai Schlüter u. Harro Zimmermann. Production by Radio Bremen / Steidl Verlag, 2006.

- Günter Grass, Hermann Kant: "I make you jointly responsible ...". The debate about the GDR past on March 21, 2010 in the Berliner Ensemble. Editor Kai Schlüter u. Ralph shock . Production Saarländischer Rundfunk / Radio Bremen, 2010 (SR2 Edition No. 05).

- Günter Grass reads “Grimm's Words. A declaration of love". 11 CD. Production by NDR / Steidl Verlag, 2010.

- Günter Grass reads “Der Butt”. 24 CD. Editor Jörg-Dieter Kogel u. Harro Zimmermann. Production by Radio Bremen / Steidl Verlag 2011.

- Günter Grass: “I'm accusing”. The Cloppenburg campaign speech. September 14, 1965. Ed. Kai Schlueter. Production Radio Bremen / Ch. Links Verlag, 2011.

- Günter Grass: The anger over the lost milk penny. A satirical campaign speech with music. Ed. V. Kai Schlueter. Coproduction Radio Bremen / NDR Kultur / Ch. Links publisher 2017.

- with Martin Walser :

- A conversation about Germany. Edition Isele, ISBN 3-86142-044-9 .

- Second conversation about Germany. Edition Isele, ISBN 3-86142-167-4 .

Film adaptations

- The tin drum . Feature film, Germany, Poland, France, Yugoslavia, 1980, 142 min., Director: Volker Schlöndorff , a. a. with Mario Adorf as Alfred Matzerath, Angela Winkler as Agnes Matzerath, David Bennent as Oskar, Katharina Thalbach as Maria Matzerath

- Cat and mouse. Feature film, FRG, 1967, 88 min., Director: Hansjürgen Pohland, a. a. with Wolfgang Neuss as Pilenz

- My century. TV reading. Günter Grass reads My Century in the Deutsches Theater Göttingen. Production Radio Bremen / 3sat 1999.

- The she-rat. TV film, Germany, 87 min., Director: Martin Buchhorn, first broadcast: ARD , October 14, 1997, a. a. with Matthias Habich as Markus Frank

- Prophecies of doom - time of reconciliation . Feature film, Germany, Poland, 2005, 98 min., Director: Robert Glinski

See also

literature

life and work

- Wolfgang Beutin: The Grass case. A German debacle. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-631-57004-3 .

- Hanspeter Brode: Günter Grass. Beck, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-406-07437-5 .

- Frank Brunssen: Günter Grass (= Literature Compact. Volume 7). Tectum, Marburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-8288-3291-6 .

- Claudia Mayer-Iswandy: Günter Grass. dtv, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-423-31059-6 .

- Volker Neuhaus : Günter Grass. Metzler, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-476-10179-7 ; 3rd, updated and expanded edition, ibid. 2010, ISBN 978-3-476-13179-9 .

- Volker Neuhaus: Writing against the passing of time: On the life and work of Günter Grass. dtv, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-423-12445-8 .

- Volker Neuhaus: Günter Grass. Writer - artist - contemporary. A biography. Steidl, Göttingen 2012. ISBN 978-3-86930-516-5 .

- Dieter Stolz: Günter Grass, the writer. An introduction. Steidl, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-86521-172-0 .

- Heinrich Vormweg : Günter Grass (= rororo monograph ). Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1986, ISBN 3-499-50359-X ; Revised and expanded new edition, ibid. 2002, ISBN 3-499-50559-2 .

Biographical aspects

- Margarethe Amelung: Five Grass seasons. About the girl who always blushed so easily. Edited by Manfred E. Berger. Langen Müller, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-7844-3123-9 (commemorative volume about five seasons as a house daughter in the Grass family).

- Kai Schlüter: Günter Grass in sight - the Stasi files. Ch. Links, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86153-567-6 .

- Kai Schlüter: Günter Grass on tour for Willy Brandt. The legendary election campaign trip 1969. Ch. Links, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-86153-647-5 .

- Kai Schlüter (ed.): Günter Grass: The milk fairy tale. Early promotional work. With a DVD from Radio Bremen. Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag 2013, ISBN 978-3-86153-739-7 .

Work aspects

- Heinz Ludwig Arnold (Ed.): Günter Grass. In: text + criticism . Issue 1, 7th revised edition, edition text + kritik in Richard Boorberg Verlag, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-88377-564-9 .

- Gertrude Cepl-Kaufmann: Günter Grass, an analysis of the entire work under the aspect of literature and politics (= scripts / literary studies , volume 18), scriptor, Kronberg im Taunus 1975, ISBN 3-589-20061-8 (dissertation University of Düsseldorf, Philosophical Faculty, 1972, 305 pages, 21 cm).

- Volker Neuhaus , Anselm Weyer (Ed.): Kitchen notes. Eating and drinking in Günter Grass's factory. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-57072-2 .

- Anselm Weyer: Günter Grass and the music. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-631-55593-8 .

- Anselm Weyer, Volker Neuhaus: Of cats and mice and mea culpa: Religious motifs in Günter Grass' work. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-631-62632-0 .

Culture, literature and media

- Klaus Bittermann (Hrsg.): Literature as torment and Gequalle. About the cultural company intriguer Günter Grass. Edition Tiamat, Berlin 2007, ISBN 3-89320-108-4 (with contributions by FW Bernstein , Henryk M. Broder , Wiglaf Droste , Gerhard Henschel , Eckhard Henscheid , Bernd Gieseking , Jörg Schröder and others).

- Hanjo Kesting (ed.): Die Medien und Günter Grass (= A publication of the Medienarchiv-Günter-Grass-Stiftung Bremen ), SH-Verlag, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-89498-173-0 .

Documentaries

- Günter Grass and Pierre Bourdieu in conversation. Documentation, 59 min., Director: Dieter Franck, first broadcast: December 5, 1999, excerpt from an interview ( memento from March 16, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) by Radio Bremen

- Günter Grass: Lübeck workshop report. Six lectures at the Medical University of Lübeck . Steidl, Göttingen 1998, ISBN 3-88243-618-2 (3 video cassettes).

- In Abraham's lap - Günter Grass travels to Yemen. Documentary, 2002, 30 min., Director and script: Tim Lienhard , production: Goethe-Institut InterNationes, commentary by Tim Lienhard.

- The inconvenient: Günter Grass. Documentation, 2007, 60 min., A film by Nadja Frenz and Sigrun Matthiesen, production: Regina Ziegler Film GmbH, theatrical release: April 19, 2007, first broadcast: ZDF , October 14, 2007, film review by WN .

- Günter Grass - The Tin Drum Story. Documentary film, Germany, 2007, 45 min., A film by Wilfried Hauke, production: NDR , summary by 3sat .

- Göttingen celebrates Günter Grass - the Nobel Prize winner turns 80. A birthday review from the Lokhalle Göttingen , production: NDR, first broadcast: October 21, 2007, summary from NDR.

- Germany, your artists . Günter Grass. Documentary, Germany, 2011, 44 min., Script and director: Dagmar Wittmers, production: Prounenfilm, NDR , first broadcast: August 3, 2011 on ARD , episode 19, synopsis by ARD.

Web links

- Literature by and about Günter Grass in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Günter Grass in the German Digital Library

- Short biography and information on the work of Günter Grass at Literaturport

- Günter Grass in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1999 award ceremony for Günter Grass (English)

- Günter Grass. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Short biography and reviews of works by Günter Grass at perlentaucher.de

- Steidl Published by Günter Grass

- Günter Grass at LYRIKwelt

- Archives in the German Literature Archive in Marbach

- Readings with Günter Grass to listen to and download on Lesungen.net

- Günter Grass archive in the archive of the Academy of Arts, Berlin

- Biographical

- The life and work of Günter Grass , photo series from Tagesspiegel , 2012

- Biography of the Nobel Institute Stockholm and press release

- Günter Grass - writer, critic, painter , updated dossier of the NDR , October 16, 2007

- Daniela Dahn : "... and live as serene as it goes to death ..." memories of Günter Grass

- Link collection

- Annotated link collection of the university library of the FU Berlin ( memento from October 11, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ) (Ulrich Goerdten)

- Assorted link collection of the virtual general library (1999–2009)

- Günter Grass, the SS, the confession

Individual evidence

- ^ Grass, Günter. In: Tim Woods: Who's who of twentieth-century novelists. London 2001. ( available online at Google Books )

- ↑ In handwriting he always used the form Graß (see above name), while all his publications (even before the spelling reform) were made under the name form Grass .

- ↑ Michael Jürgs: Who is Günter Grass? In: Tagesspiegel , August 13, 2006.

- ↑ a b The Günter Grass case. In: Stern , No. 34/2006.

- ^ As a prisoner of war, Grass admitted Waffen SS membership. In: Spiegel Online . August 15, 2006.

- ↑ Patrick Bahners : At seventeen heroism and youth mania: The Grass debate rages on. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . August 18, 2006, No. 191, p. 33.

- ↑ a b Why I break my silence after sixty years. A German youth: Günter Grass speaks for the first time about his memory book and his membership in the Waffen SS. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . August 12, 2006, No. 186, p. 33.

- ^ Hubert Spiegel : Günter Grass as an SS fighter. Of marching routes and storms of protest. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , October 19, 2014.

- ↑ “Blechtrummler” was a wettinger - that's how he inspired Günter Grass . In: Aargauer Zeitung from April 15, 2015.

- ↑ Lothar Müller : Günter Grass: "The Box". The consent machine. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung of August 25, 2008.

- ↑ Anselm Weyer: The dance of Günter Grass. Scarecrows, moths, five cooks and a goose: the great man of letters had a weakness for ballet. Tanz the European magazine for ballet, dance and performance (May 2010), p. 50ff. ( Memento of the original from August 14, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Volker Weidermann: That was potassium cyanide, my lady! In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung. February 19, 2006, No. 7, p. 26.

- ^ German-Israeli Society ( Memento from June 4, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ "From cat and mouse and mea culpa": Günter Grass and the religion In: haz.de of November 22, 2012.

- ↑ Action 1: 1: Testimonials - Statements from the supporters of the Action 1: 1 ( Memento from May 4th 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Protest reading in Krümmel. Günter Grass rumbles against lobbyists . In: Spiegel Online . April 10, 2011.

- ↑ Hannah Pilarczyk / dpa: Nobel Prize Laureate in Literature: Günter Grass is dead. In: Spiegel Online from April 13, 2015 (accessed on April 13, 2015); Nobel laureate for literature Günter Grass died at the age of 87. In: FAZ.NET , April 13, 2015. ( online )

- ↑ Günter Grass buried in Behlendorf. Lübecker Nachrichten, April 30, 2015, p. 19.

- ^ Knerger.de: The grave of Günter Grass

- ^ John Irving says goodbye to Günter Grass . Lübecker Nachrichten of April 25, 2015, p. 18.

- ↑ Mourning flags for Günter Grass . Lübecker Nachrichten, May 9, 2015, p. 18.

- ^ An emotional farewell to Günter Grass . ndr.de, May 10, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ^ Press release of the Swedish Academy: The Nobel Prize in Literature 1999: Günter Grass . September 30, 1999.

- ^ Rebecca Braun: Constructing Authorship in the Work of Günter Grass. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-954270-3 , p. 57, quote: Only very loosely engaging with the real novel, it focuses instead on how an oversized Grass storms through the Berlin underworld showering all and sundry with his half-baked political ideas

- ↑ Monika Shafi: Günter Grass' When peeling the onion. In: Stuart Taberner: The Novel in German since 1990. Cambridge 2011, pp. 270–280, here: 271 and 273. Cf. also Stuart Taberner: "It could be that something of his ego can be found in every book": "Political" Private Biography and "Private" Private Biography in Günter Grass's Die Box '(2008), In: German Quarterly. 82, 4, 2009, pp. 504-521.

- ↑ Stuart Taberner: The Cambridge Companion to Günter Grass, Stuart Taberner, Cambridge University Press 2009, p. 150.

- ↑ Locally different anesthetized , review by Hellmuth Karasek in Die Zeit from May 29, 1970, accessed October 20, 2014.

- ↑ Günter Grass biography on the biography portal www.die-biografien.de

- ^ Heinz Ludwig Arnold : The group 47 . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2004, ISBN 3-499-50667-X , pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Dieter Stolz: From the private complex of motifs to the poetic world design. Constants and developments in the literary work of Günter Grass (1956–1986). Würzburg 1994, p. 91.

- ^ Poem by Günter Grass on the Greek crisis of Europe's shame Süddeutsche Zeitung May 25, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012; Grass writes about Greece: with refilled ink. In: Spiegel Online. May 25, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ↑ Stuart Taberner (Ed.): The Cambridge companion to Günter Grass. Cambridge et al. 2009, p. Xvi.

- ^ Klaus Roehler, Rainer Nitsche (ed.): The election office of German writers in Berlin 1965. Attempt to take sides. Political-literary revue with contributions by Friedrich Christian Delius, Günter Grass, Peter Härtling, Günter Herburger, Klaus Roehler, Karl Schiller, Peter Schneider, Günter Struve and Klaus Wagenbach. Transit, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-88747-061-3 .

- ↑ SWI entry at Hajekmuseum ( Memento from October 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c See the articles in Kai Schlüter (Ed.): Günter Grass on tour for Willy Brandt. The legendary election campaign trip in 1969. Berlin 2011.

- ^ A b Heinrich August Winkler: The long way to the west. German history from the “Third Reich” to reunification. Volume 2, Munich 2000, p. 241 ff.

- ^ The Grass case and its predecessors . In: Handelsblatt . August 16, 2006.

- ↑ Jan Fleischhauer: Farewell to a moral authority. 2011.

- ↑ See: Volker Neuhaus : Günter Grass: Mein Jahrhundert - 1970. In: Werner Bellmann , Christine Hummel (ed.): Interpretations. German short prose of the present. Reclam, Stuttgart 2006 ( RUB ), pp. 244-249.

- ↑ A short speech by a journeyman without a fatherland . In: The time . No. 7/1990.

- ↑ Martin Doerry & Volker Hage : Spiegel talk: "You are lonely anyway" . In: Der Spiegel . No. 19 , 2015, p. 136 ff . ( online ).

- ↑ Toad to snail. In: Der Spiegel 1/1993.

- ↑ Exodus of the lion . In: Der Spiegel . No. 51 , 1988 ( online - The Association of German Writers has no effective leadership. Celebrities step out, the wings are squabbled - is the Association at its end?).

- ↑ Renate Chotjewitz, Carsten Gansel (Ed.): Verfeindete loner. Writers argue about politics and morals . Aufbau Verlag, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-7466-8023-9 and the representation of the VS-Landesverband Bayern Who we are: To the history of VS. Part 5: The 80s: Further congresses, topics, goals, disputes, crises. VS Bayern, accessed on April 15, 2019 .

- ↑ Günter Grass: Freedom given - failure, guilt, lost opportunities. In: The time . May 10, 1985.

- ↑ Caricature dispute: Grass criticizes caricatures as deliberate provocation . In: FAZ . February 9, 2006.

- ↑ Murder of Armenians: Grass and the Turks. In: Zeit Online. April 16, 2010. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ↑ Nobel laureates urge Israel to let Vanunu receive int'l rights award. In: Haaretz . November 20, 2010.

- ↑ Frank Schirrmacher, Hubert Spiegel: Why I break my silence after sixty years. Interview with Günter Grass in: FAZ. August 11, 2006.

- ↑ Quoted from Die Welt : Text passages from "When skinning the onion" , August 16, 2006

- ↑ Lothar Schröder: No shot fired during his service: Grass, the Waffen SS man. In: Rheinische Post . August 14, 2006. Retrieved August 29, 2018 .

- ↑ Klaus Wiegrefe : Grass granted Waffen SS membership as a prisoner of war. In: Der Spiegel. August 15, 2006.

- ↑ a b Interview with Robert Schindel: "The way Grass is treated is a poor testimony" . In: Spiegel Online . August 15, 2006.

- ^ "Günter Grass and his SS past" (compilation of numerous statements)

- ↑ Netzeitung : Central Council of Jews accuses Grass of PR campaigns ( memento from August 22, 2006 in the Internet Archive ). August 15, 2006.

- ↑ Reactions to Günter Grass' SS confession - "It would be best if he would do without it" . ( Memento from April 20, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . August 14, 2006.

- ↑ Klaus Bittermann (ed.): Literature as torment and gequalle. About the literary company intriguer Günter Grass. Berlin 2007.

- ↑ Klaus Priesucha: Halali on a Nobel Prize winner. A confident nation blows to hunt . ( Memento of December 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ WHY THE GRASS AFFAIR MUST ALWAYS CONTINUE - court poet with party book

- ↑ SS past: Walesa contests Grass for honorary citizenship . In: Spiegel Online. August 13, 2006.

- ^ Grass' SS confession - CDU politician demands return of the Nobel Prize . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . August 14, 2006.

- ↑ Junge Union : Too late admission by Günter Grass is shameful . August 14, 2006.

- ^ Walesa: "Have no more conflict with Mr. Grass" In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of August 22, 2006

- ↑ SWR2 : A pale grazing light from Grass in the sharp shadow of the crane gate . October 16, 2007, broadcast by Ursula Escherig; Manuscript ( RTF ; 69.8 kB)

- ^ Grass' Nobel Prize for Literature: "The award is final" . In: FAZ. August 15, 2006.

- ↑ Controversy over biography: Günter Grass sues against SS allegations . In: Spiegel Online. November 23, 2007.

- ↑ Spiegel Online: Complaint because of SS allegation: Grass and Jürgs agree on a settlement . In: Spiegel Online. February 11, 2008.

- ↑ Stasiakte Grass www.mauerfall-berlin.de, accessed on October 23, 2016.

- ↑ Stasi study: Strittmatter "prevented" the arrest of Grass in 1961. In: Mitteldeutsche Zeitung. October 5, 2011; accessed on October 23, 2016.

- ↑ We Germans are unpredictable . In: Der Spiegel . No. 25 , 2006 ( online ).

- ↑ Günter Grass: What has to be said. - Original text of the first publication in the Süddeutsche Zeitung of April 4, 2012, online at Süddeutsche.de

- ^ Grass interviews on television. The poet defends himself. In: Spiegel online. April 5, 2012 (online)

- ^ "Israel accuses Grass of anti-Semitism." Die Zeit , April 4, 2012.

- ↑ Poem on the Iran conflict. Günter Grass brings against Israel from Spiegel de, April 4, 2012. Retrieved on April 4, 2012.

- ↑ Grass writes poem against Israel What had to be said? ( Memento of April 7, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Tagesschau de., April 4, 2012. Retrieved on April 4, 2012.

- ^ Israel declares Grass to be a persona non grata. ( Memento from April 10, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Tagesschau.de , April 8, 2012.

- ↑ Online edition of the Haaretz magazine: Israel has reacted with hysteria over Gunter Grass , April 9, 2012.

- ↑ Leaning too far out of the window against Grass? In: new Germany . from April 19, 2012.

- ^ Decision of the writers' association: Grass remains PEN honorary president. at: sueddeutsche.de , May 12, 2012 (accessed May 12, 2012).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Siegfried Mews: Günter Grass and his critics. From "The tin drum" to "Crabwalk". Rochester 2008, pp. 77-81.

- ^ Günter Grass and Alice Schwarzer peak. In: Cicero . May 2007.

- ^ Carolin John-Wenndorf: The public author. About the self-presentation of writers. Bielefeld 2014, p. 330.

- ↑ Stuart Taberner: Aging and old-age style in Günter Grass, Ruth Klüger, Christa Wolf, and Martin Walser. The mannerism of a late period. Rochester 2013, pp. 40-91.

- ↑ Media farce. “FAS” mocks the Grass poem in the “SZ” . Spiegel online May 27, 2012.

- ↑ Volker Weidermann: Noch'n poem: Where would Günter Grass be without Greece? In: faz.net of May 26, 2012. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ↑ Burkhard Müller: Delicate final line. In his posthumous book ‹Vonne Endlichkait›, Günter Grass shows himself unusually self-deprecating. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , 29./30. August 2015, p. 18.

- ↑ https://www.kulturkreis.eu/kuenstlerfoerderung

- ↑ Albo d'oro ( Memento of the original from March 21, 2019 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Press release: Günter Grass honorary doctorate from the University of Lübeck

- ↑ PRIZE WINNER 2005 - International Eckart Witzigmann Prize. Retrieved on December 19, 2017 (German).

- ↑ Günter Grass: "The European of the Year". In: The time. December 19, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Schleswig-Holstein milestone - Association of German Sinti and Roma e. V.

- ^ Danzig honors Grass on dw.com, October 17, 2015 (accessed October 17, 2015).

- ↑ Lübeck News. October 8, 2014, p. 3.

- ↑ Review of Vonne Endlichkait : Friedmar Apel : Was mecht nu los sain inne Polletik . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . September 1, 2015, ISSN 0174-4909 , p. 12 ( faz.net [accessed February 2, 2019]).

- ↑ Early stories published by Grass , deutschlandfunkkultur.de, published and accessed on May 10, 2019

- ^ Poem by Günter Grass on the Greek crisis, Europe's shame Süddeutsche Zeitung. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ↑ https://steidl.de/Buecher/Du-Ja-Du-Liebesgedichte-0813324758.html

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Grass, Günter |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Grass, Günter Wilhelm (full name); Graß, Günter Wilhelm (birth name); Graß, Günter; Knoff, Artur (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German writer, sculptor, painter and graphic artist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 16, 1927 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Danzig - Langfuhr , Free City of Danzig |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 13, 2015 |

| Place of death | Lübeck |