Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain (born April 24, 1856 in Cauchy-à-la-Tour , Pas-de-Calais department , † July 23, 1951 in Port-Joinville , Île d'Yeu , Vendée department ) was a French military man , Diplomat and politician . From 1940 to 1944 he was head of state of the authoritarian État français ( Vichy regime ).

During the First World War , Pétain became a celebrated national hero ( "Hero of Verdun" ) due to his defensive successes in the Battle of Verdun and in 1917 became Commander-in-Chief of the French Army . In the interwar period , as an influential Marshal of France and in various military offices , he played a decisive role in shaping the defense doctrine of his country.

In the course of the looming French defeat against the National Socialist German Reich , Pétain became the last head of government of the Third Republic on June 16, 1940 and obtained the Compiègne armistice . He then took over from 1940 to 1944 as Chef de l'État ( Head of State) with almost absolute powers of leadership of the État français in Vichy, which collaborated with the Reich , and in the Révolution Nationale proclaimed the breach of the republican-democratic principle in France. With the political rise of Pierre Laval , Pétain lost his unrestricted position of power from 1942.

Because of the collaboration, Pétain was sentenced to death in 1945. However, the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment .

Origin & early years

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain was born on April 24, 1856 on his parents' farm in Cauchy-à-la-Tour . The Pétains were simple, long-established farmers from the coal mining area in northern France who cultivated the family's ten hectares of arable land . He was the only son of Omer-Venant Pétain (1816–1888) with his wife Clotilde nee. Legrand (1824–1857) and had three older sisters, Marie-Françoise (1852–1950), Adélaïde (1853–1919) and Sara (1854–1940). After the birth of the daughter Joséphine (1857–1862), the mother died in October 1857 in childbed , which is why the father remarried in 1859 and had three more children. As a result of the neglect by the stepmother, Philippe and two of his sisters, described as quiet, grew up in the household of their strictly religious grandmother.

His uncle, Abbé Jean-Baptiste Legrand, is ascribed a formative influence on the adolescent Pétain ( "My dear nephew! I only wish one thing, that there will always be men in my family who carry the cross - and the sword." ) . As pastor of the parish of Bomy This allowed his eleven year old nephew by half scholarship from October 1867 to visit the Jesuit College Saint-Bertin in Saint-Omer . In the monastery school there , Pétain received a school education characterized by religiosity , obedience and discipline between 1867 and 1875 . Under the impression of the French defeat of 1871 and the war reports of his great-uncle Joseph Lefebvre, a Catholic priest who had served as a young man in the Grande Armée , Pétain developed the desire to serve his country as a soldier. In preparation for the planned military career, he moved in 1875 to that of Dominicans led Collège Albert-le-Grand to Arcueil ( department Val-de-Marne ).

Officer career until 1914

On October 25, 1876, Pétain entered the Saint-Cyr National Military School as the 403rd of 412 cadets . He completed his two-year training as an officer as the 229th of 336 graduates of his year ( N ° 61 de Plewna ).

After military school, Pétain went to the infantry and served with the rank of Sous lieutenant in the 24th battalion of the Chasseurs à pied in Villefranche-sur-Mer (1878-1883), then for five years as a lieutenant in the 3rd battalion in Besançon . Pétain was seen as distinguished, cool and intelligent. From 1888 to 1890 he completed his training as a general staff officer at the École supérieure de guerre in Paris , which he finished as captain ( 14 e doctorate ). As a result, Pétain entered his first staff positions at the XV. Army Corps in Marseille (1890-1892) and the 29th Chasseurs Battalion in Vincennes (1892/93) before he was appointed to the staff of the Paris military governor Général Félix Gustave Saussier in 1893 . Under his successors Émile Auguste Zurlinden and Henri Joseph Brugère , Pétain was an orderly officer . In the course of his officer career, Pétain showed little interest in a use within the growing colonial empire and was, unusual for the conditions at the time, only used in locations in the mother country . In order not to jeopardize his career, Pétain treated his political views with the utmost discretion and his stance on the Dreyfus Affair is unknown.

Rejection of the offensive à outrance

Pétain experienced a relatively slow military rise and remained 22 years of service in the group of subaltern officers . It was not until 1900 that he received the position of battalion chief in Amiens (8th battalion of the Chasseurs à pied) while simultaneously being appointed instructor at the École normal de tir in Châlons-sur-Marne . There Pétain drew attention to himself because of the unconventional rejection of a pure offensive strategy and with this alternative stance stood in contrast to the tactical doctrine of army leadership ( offensive à outrance ). For their leading military theorists, Ferdinand Foch and Louis Loyzeau de Grandmaison , a defensive attitude was the main cause of the French defeat in 1871. In order to compensate for the objective German advantage of the larger population, the army should be trained in an offensive spirit, regardless of opposing intentions become. This is the only way to win back Alsace-Lorraine for France ( revanchism ). Impressed by the enormous firepower of modern machine guns , Pétain was skeptical and thought the strategic offensive was no longer justifiable. He did not believe in the effectiveness of fanatical, frontal assault attacks by the infantry. This would inevitably lead to a massacre. Rather, Pétain demanded a high rate of fire and accuracy, while the increased weapon effect made safe cover for the troops necessary ( "If necessary, let yourself be killed. But I would prefer you do your duty and stay alive." ). His opposing views, which he summarized under the catchphrase " Le feu tue " (Firepower kills) , hampered Pétain's military advancement. After only six months, he was replaced again as an instructor and 5th Infantry Regiment added .

Despite critical consideration of his tactical ideas, Pétain worked at the École supérieure de guerre between 1901 and 1903 and 1904 and 1907. First as an assistant professor for infantry tactics , then he filled the chair for infantry. In addition to his teaching position, he wrote memoranda to improve the interaction between infantry and artillery , an area that had been neglected by the French general staff. With his undisguised disdain for the offensive à outrance, Pétain remained an outsider within the officer corps and found no support from his superiors either. After Foch had taken over the management of the war college, he replaced Pétain as a lecturer and arranged for his temporary transfer as Lieutenant-Colonel to the 118th Infantry Regiment in Quimper in Brittany . Between 1908 and 1911 Pétain returned for the last time as a tactics professor at the École supérieure de guerre.

After teaching, Pétain returned to command of the troops on June 26, 1911 and took over the 33rd Infantry Regiment in Arras with the rank of Colonel . There the young Charles de Gaulle was a member of the regimental staff from 1912. When Pétain was given command of the 4th Infantry Brigade in Saint-Omer on March 20, 1914 , the War Ministry denied him the associated promotion to the Général de brigade . As a result, Pétain, who had not actively participated in any combat events in his 36 years of service, began to prepare for his retirement after an unremarkable career.

First World War

Fast ascent

When the general mobilization was triggered on August 2, 1914, Pétain's brigade was assigned to the 5th Army under Général Charles Lanrezac . This marched against the approaching German troops and was supposed to prevent them from crossing the Maas . During the beginning of the border fighting, Pétain was first used in active combat on August 14 near Dinant . In the following Battle of the Sambre (August 21-23), Pétain's units managed to cover the tactical retreat of the 5th Army, and he did well during the Battle of St. Quentin (August 28-30) emerged as a capable commander. In the first few weeks of the war, the French high command removed hundreds of officers from their posts, and the promotion to the Général de brigade marked the beginning of the late military rise of the 58-year-old Pétain, who wanted to retire before the war began. In the course of the German advance on Paris, he received command of the 6th Infantry Division on September 2 . In the course of the decisive battle on the Marne , the latter was in fierce defensive fighting between the Aisne-Marne Canal and the Fort de Brimont . After the surprising Franco-British counterattack, the advancing German army withdrew and Paris was saved (“Miracle on the Marne”). Through his resolute action, Pétain had successfully recommended himself for higher tasks and received the rank of Général de division on September 14 and the Officer's Cross of the Legion of Honor in recognition of his achievements .

With the rapidly following promotion to the Général de corps d'armée on October 20, 1914, Pétain had risen to a four-star general within eleven weeks of the war and was given command of the XXXIII. Army corps . The corps belonged to the newly formed 10th Army under Louis Ernest de Maud'huy and was located in the Arras area ( Flanders ). After the race to the sea , the movement had in the meantime frozen into position warfare and as one of the few higher French commanders, Pétain worried about the well-being of the common soldiers. During the trench warfare , he tried to improve their everyday conditions and trained the units under him in the winter months for the upcoming offensives of 1915. His demeanor made Pétain a "human general". During the Second Battle of Artois in May / June 1915 broke through the German positions on Pétain associations ridge of Vimy , but failed the planned capture of the town Carency , and the operation had to be abandoned due to lack of reserves.

Due to his, albeit limited, successes in the Loretto battle, Pétain moved into the field of vision of Commander-in-Chief Joseph Joffre , who appointed him to the head of the 2nd Army on June 21, 1915 and appointed him Général d'armée . Pétain was a French offensive in the Champagne prepare and its organizations were to colonial troops expanded . The unsuccessful attempt at attack by the French in the autumn battle in Champagne (September to November 1915) showed that Pétain had been right with his theories, which he had put forward as an instructor at the military academy. The defenders had a strategic advantage, and large infantry attacks against heavily developed positions defended by machine guns and artillery fire of hitherto unknown proportions led to unsuccessful material battles . The western front persisted in trench warfare. As a consequence, Pétain refused to carry out further offensives and recommended in a memorandum a more defensive warfare ( "the artillery captured, the infantry occupied" ). Accordingly, the Entente must first establish a superiority of weapons in order to then switch to locally limited offensives.

Battle for Verdun

At the beginning of 1916, the German Supreme Army Command under Erich von Falkenhayn switched to a "fatigue strategy" on the western front . This provided for the French army to literally "bleed to death " in a material battle and thus to force the decision to go to war by "exhausting" the enemy. The front arch around the Verdun Fortress was chosen as the scene of the massive offensive, and on February 21, 1916 the Battle of Verdun began with the German attack . After the fall of the strategically important Fort Douaumont (February 25th), the breakthrough threatened and the French high command quickly relocated the 2nd Army from the operational reserve to the threatened sector of the front. Despite an acute bronchitis , Général Pétain was the new commander of all troops deployed in this sector on February 26 and was supposed to organize the defense. He moved his headquarters in the immediate area of the stage and moved into the Mairie of the municipality of Souilly .

In the clear conviction that the limitation of the German attack on the right bank of the Meuse had been a serious tactical mistake, he had the inner defensive ring expanded into a barrage position that he had named . He reorganized the artillery, and the gun batteries should bring the attacks of the Germans to a standstill at any time. Pétain took measures to organize the supplies more effectively , and every day 3,500 trucks supplied the front troops via the Voie Sacrée . The introduction of the Noria reserve system developed by Pétain was decisive for the permanent stabilization of the front . If fighting units had lost a third of their combat strength, they were relocated to reserve positions and other sections after a short front-line deployment. The short fighting times before Verdun noticeably reduced the exhaustion and thus the failure rate of the soldiers, strengthened morale and the spirit of resistance. In total, 259 of the 330 French infantry divisions were used in the battle by the end of the war. This fact was an essential factor in establishing Verdun as a symbol of the unbroken French resistance.

Throughout April, Pétain led the fierce defense of Fort Vaux and the mountain ranges "304" and " Le Mort Homme ". The successful defense against the German attempts to conquer the mountain ranges prompted Pétain to write a declaration to the soldiers of the 2nd Army on April 10, in which he called on them to make even greater efforts and which is one of the most famous of the First World War :

“April 9th is a glorious day for our armed forces. The bitter attacks of the Crown Prince's soldiers have failed everywhere: Infantrymen, gunners, pioneers and pilots of the 2nd Army have surpassed each other in heroism. My respect to everyone. The Germans will certainly continue to attack. May everyone show as much commitment as before.

Take courage! ... We will defeat them! "

Pétain's central strategic goal was to retake Fort Douaumont in order to open a new flank against the Germans. However, he was still against the offensive à outrance and avoided lossy, hopeless attack operations and had to be constantly called on by Joseph Joffre to counter attacks. The Commander-in-Chief hoped that Pétain, who was inclined to constant pessimism, would have a better overview of the general situation if he gave him more distance and placed a broader front. Despite his undeniable defensive successes, Pétain was replaced on May 1, 1916 by Robert Nivelle at the head of the 2nd Army. With the appointment of Nivelle, the high command relied on a representative of the offensive defense strategy. Pétain had proven himself to be a competent and capable military commander, but against his wishes was appointed commander in chief of the superior Groupe d'Armées du Center (Army Group Center) in Bar-le-Duc . In addition to the indirect defense of Verdun, the front sections of the 3rd , 4th and 5th Army were also under his command. The battle for Verdun continued with undiminished severity and the French had to evacuate Fort Vaux on June 7th. By British relief attacks on the Somme , the Russian Brusilov offensive and a change in the Supreme Army Command, Nivelle was able to initiate successful counter-offensives. These led to the reconquest of Douaumont on October 24 and were discontinued on December 20, 1916 after a tactical victory.

Through his confidence and unshakable steadfastness, with which Pétain had driven his troops time and again, he achieved national fame in the spring of 1916. His famous commands of the day ( «Courage!… On les aura!» « Have courage!… We'll get them! « And « Ils ne passeront pas! » « You will not get through!» ) Contributed significantly to his aura as the "savior of France" at, and the French press referred to him as the "Hero of Verdun" . When the politically well-connected Nivelle was appointed the new Commander-in-Chief of the French Army in December 1916, Pétain experienced an unexpected downgrade.

French commander in chief

With the spring offensive on the Aisne that began on April 16, 1917 , the new Commander-in-Chief Robert Nivelle tried to break up the trench warfare. The inadequately prepared operation collapsed under German defensive fire after enormous losses on the Chemin des Dames ridge . As a reaction to the renewed failure, large parts of the demoralized northern armies refused to give orders and mutinied against the "blood drunkard" Nivelle. The widespread refusals of obedience affected 68 of the 112 French divisions, which threatened to collapse the entire section of the front in May 1917 ( mutinies in the French army ). In view of the threatening extent of the military crisis, Minister of War Paul Painlevé called for the offensive to be stopped and spoke in the cabinet for a change in the army leadership. The government followed the suggestion. She dismissed Nivelle and appointed Philippe Pétain, who had already expressed criticism of his predecessor's plans, on May 15, 1917, as the new Commander-in-Chief of the Army. The Grand Quartier Général (GQG) housed in Compiègne Castle , which Pétain underwent various restructuring measures, was under his command . He paid special attention to the creation of its own staff units (bureaux) for aviation , telegraphy , cryptography and the connection to the civil authorities.

Under the impression of the Russian February Revolution , many members of the government saw the mutinies as a result of Bolshevik infiltration . Pétain, on the other hand, realized, after numerous front-line visits and personal conversations with the soldiers ( Poilu ), that they were not concerned with political demands, but with changes both in the employment relationship and the appreciation of their everyday situation. Less through draconian disciplinary measures - of the 554 death sentences pronounced by the military courts, Pétain had only 49 carried out - than through an improvement in the supply organization, accommodation in regeneration camps, reform of the leave from the front and the introduction of the principle of rotation, Pétain succeeded in increasing the combat readiness and obedience of the troops up to Restore July 1917. Pétain and “apostle of the defensive” , popular with soldiers , immediately made a fundamental change in French war tactics. In accordance with his maxim “Firepower kills” ( “Le feu tue” ), he limited himself to defensive, wait-and-see warfare over the next few months and only ordered limited attack operations supported by massive artillery fire ( Battle of Malmaison ). He demanded the increased availability of the new armored weapon ( “I'm waiting for the Americans and the tanks” ) and in Directive No. 4 of December 22, 1917, he presented his views on the coming developments:

“The Entente can regain the superiority of the armed forces if the American army is able to bring in a certain number of large units. Until then, we must wait and see, even at the risk of irreparable wear and tear, but we must not give up the idea of starting the offensive, which alone can bring the final victory, as soon as possible. "

But first the German Supreme Army Command under Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff sought the decision to go to war with the spring offensive and put the Entente under pressure. The Michael company started on March 21, 1918 at the interface between the French army and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and had the goal of pushing it to the north. In this critical situation, Pétain held back most of his reserves for the possible German advance on Paris and only transferred a few divisions to the front section of the hard-pressed British 5th Army . Due to the military crisis, at a meeting of the Allied Supreme War Council ( Doullens Conference ) on March 26th, the Entente Powers recognized the need for a unified, coordinated warfare and decided to form a joint command. During the conference, Pétain accused the British of obstinately pursuing their own war aims and recommended an evacuation of the capital. Speaking to Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau , Pétain feared that the British Commander-in-Chief Douglas Haig "was a man who would have to surrender in the open field within the next fortnight" , whereas Ferdinand Foch called for fanatical resistance. Given Pétain's reservations about the British and his openly displayed pessimism, he was not proposed for the post of joint commander in chief. Finally, an agreement was reached on Foch, who as generalissimo received the supreme command of all troops on the western front and was henceforth responsible for joint warfare. Foch threw the French reserves to the front and was able to stop the German advance, which, however, was resumed in May / June 1918. The Germans conquered Soissons and advanced to the Marne ( Battle of the Aisne ). Pétain countered this critical situation by setting up a staggered defense in the depths under the temporary surrender of French territory. Despite the reservations within the generals , Pétain's defense strategy proved its worth, and the German advance was halted at Reims in July . Pétain was honored with the military medal for his successes . Compared to Foch, Pétain pleaded for the involvement of the US expeditionary force , and the increased presence of the ever-increasing number of American troops strengthened the lines and improved the morale of the fighting French units. In the Second Battle of the Marne , Foch launched a swift counterattack on July 18, and after the Battle of Amiens the Entente finally gained the strategic upper hand. Then Foch ordered the coordinated action of all armed forces and with the Hundred Days Offensive (August to November 1918) forced the German retreat behind the Siegfried line .

To avoid the impending collapse, the German Reich submitted an armistice petition to the Entente, which was signed in Compiègne on November 11th . The armistice made Pétain and his chief of staff Edmond Buat 's plans for a Franco-American offensive in Lorraine obsolete. This would have aimed at an advance with 25 divisions from the Verdun area into German territory and should force the Reich to surrender .

On November 19, 1918, Pétain entered Metz, which was evacuated by the Germans, at the head of the 10th Army .

Marshal of France

Alongside Ferdinand Foch, to whom the victories of 1918 were attributed, Pétain was one of the most respected commanders of the French army after the end of the war. As an outward sign of appreciation, the Chamber of Deputies appointed him by decree on November 21, 1918, Marshal of France , the highest military honor in the republic . In a solemn ceremony in the main courtyard of the fortress Metz on December 8, 1918, Pétain received the marshal's baton from President Raymond Poincaré . Poincaré honored him in his address with the words:

“You achieved everything you asked for with the French soldier. You understood him, you loved him, and he thanked you with obedience and devotion for the affection and care you showed him [...] Fabert's virtues were also yours: cleverness, method, constant concern for that Well-being of the troop; striving to sacrifice all self-love and every personal interest to the country. "

Pétain was a celebrated national hero and his reputation abroad was manifested in military honors from all allied states. As a further expression of public appreciation, he was accepted on April 12, 1919 by the Institut de France in the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences . The inevitable high point of his officer's career was the French national holiday , which on July 14, 1919 was combined with a parade to mark the end of the First World War. For the first time, troops from all alliance powers moved across the Avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris. On a white horse , Marshal Pétain led the French units, which were composed of members of all departments .

In the course of demobilization , the Grand Quartier Général was dissolved and Pétain resigned from the position of Commander-in-Chief on October 20, 1919.

Interwar period

Conseil Supérieur de la Guerre

On January 23, 1920, Pétain was appointed Vice President of the Conseil Supérieur de la Guerre (CSG) by the government because, unlike Foch, he was considered a loyal republican who did not interfere in politics. He was chairman of the highest military institution in France and would automatically have exercised supreme command in the event of war. In addition, Pétain took over the post of inspector general of the army in February 1922 , whereby he received an advisory role in the Conseil Supérieur de la Défense Nationale (CSDN). The task of the Defense Council was to prepare a possible war strategy, to make decisions about armament, training and the formation of the armed forces. Pétain had the right to veto decisions by the Chief of Staff . He was able to fill this post with his confidante Edmond Buat and, after his death in 1923, with Marie-Eugène Debeney .

In his functions, Pétain played a decisive role in shaping France's defense doctrine. The Instruction provisoire sur la conduite des grandes unités (provisional instruction on the conduct of large units) , drafted by Général Debeney and issued by Pétain in 1921, was to remain the official doctrine of the French army until 1935. The instruction was based on Pétain's findings and conclusions from the trench warfare and provided for a strictly defensive war tactic in the event of a renewed German attack on France. The offensive should only be considered with sufficient firepower and superior personnel. Pétain manifested the primacy of infantry, while tanks and air forces were the only supporting branches of service. For an effective defense of France, he demanded the provision of 6,875 tanks, although his basic instructions on the role of the armored weapon only contained the sentence "Tanks support the infantry's advance by fighting down field fortifications and stubborn resistance of the infantry" .

High casualties during the First World War (1.3 million killed) and a lower birth rate in relation to the German Reich were the main reasons for France's defensive military orientation. Pétain had to take into account the political framework, as the government decided in 1923 to shorten compulsory military service from 36 to 18 months and made regular reductions in the military budget. The government commissioned the army to prepare a study for defending the borders in order to be prepared against another German invasion after the experiences of 1914. As part of this study, Pétain advocated a linear, fortified front and pleaded for the development of strong defensive fortifications along the border in order to guarantee the “inviolability” of French territory. He based himself on the example of the fortress city of Verdun and personal defensive successes. During an extensive tour of the French bunker systems in 1927/28 and in the course of a further reduction in conscription to twelve months, Pétain pushed the debate on building a protective wall. Although the 1920s were marked by savings in the French military budget, in 1930 Parliament approved the funding to build a fortified line of defense. War Minister André Maginot introduced the relevant bill , and the fortification was named Maginot Line . By November 1936, 1,000 kilometers were considered to have been completed and the cost was five billion francs . The dogma of the invincibility of the Maginot Line was born, and French public opinion looked at the line of fortifications with almost religious confidence.

In 1925, Pétain appointed Charles de Gaulle, whom he had promoted, to his personal staff. De Gaulle's main task was to prepare two military treatises that would appear under the name of the famous marshal. There were arguments between them about the content, which led to a significant cooling of the friendly relationship.

After Ferdinand Foch's death, Pétain was unanimously elected as a member of the renowned Académie française in 1929 and officially introduced on January 22, 1931. The laudation was given by the writer Paul Valéry .

Upon reaching the age limit of 75, Philippe Pétain retired from the army on February 9, 1931. He handed over the functions of Vice-President of the Supreme War Council and General Inspector to Général Maxime Weygand .

Reef war

The uprising of the Rifkabylen , a Berber tribe led by Abd al-Karim , which had been smoldering since 1921 , threatened Spanish colonial rule in northern Morocco ( Rif War ). The Spaniards did not succeed in crushing the Rif Republic , which had meanwhile become independent . The unrest threatened to spread to the French protectorate , and General Resident Hubert Lyautey seemed to be slipping away. The Painlevé government assured the oppressed Spaniards their support. They agreed with Miguel Primo de Rivera on a joint military operation and transferred large contingents of troops to North Africa.

Despite his reservations about never having served in the colonies, the government entrusted Marshal Pétain with supreme command of the expeditionary forces on July 13, 1925. With the appointment of Pétain, who enjoyed an enormous civil and military reputation, the aim was to win over pacifist public opinion for a war. On September 3, Pétain arrived in Fès, Morocco, and took over command, making Général Alphonse Georges his chief of staff and his most important collaborator. The arrival of Pétain led to the embittered Lyautey voluntarily resigning from office. The Spanish-French armed forces numbered 250,000 men and were supported by artillery, tanks and aircraft. With massive use of materials, the destruction of the infrastructure by air raids and strong artillery fire, Pétain managed to contain the guerrilla actions of the insurgents and to force them to retreat to the Rif Mountains by the end of 1925 . Pétain had the fertile growing areas in the north of the country occupied and was thus able to prevent the rebels from getting food. In a carefully prepared offensive, the Spaniards advanced from Al Hoceïma into the mountain range on April 15, 1926 , and the French troops advanced from the south towards Ajdir . During the fighting, the Europeans used mustard gas bombs in violation of international law (use of chemical weapons in the Rif War ). Al-Karim had to surrender to the technologically superior expeditionary forces on May 27, 1926, and the colonial powers were able to fully restore their rule.

For his services, Pétain was awarded to the Spanish King Alfonso XIII. Awarded the Medalla Militar in the Infantry Academy of Toledo .

Political beginnings

Although Philippe Pétain had retired from the army, he continued to be an important figure in the French public. His unbroken authority as the Hero of Verdun and Marshal of France was firmly anchored in society. Various right-wing groups vied for the favor of the war hero, who had already developed a tendency towards authoritarian , anti-parliamentary political approaches in the 1920s and who took an increasingly critical stance on the parliamentary system of government . In particular, the politically active journalist Gustave Hervé publicly advocated the creation of an authoritarian form of government and saw the dictatorship of Marshal Pétain as the only way to save France. Pétain showed great admiration for the Spanish military dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera, who wanted to renew his country under the slogan "Fatherland, religion, monarchy" .

In 1931, Pétain received an invitation from the American General John J. Pershing and traveled with the Prime Minister's delegation, Pierre Laval, on a state visit to the United States . As the official representative of the French Republic, Pétain took part in the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Yorktown , which decided the American War of Independence against England . In doing so, he emphasized the alliance between France and the USA, in a demonstrative demarcation from Great Britain. On the occasion of the visit, the city of New York honored the highly respected Marshal with a parade on Broadway on October 26th .

Minister of War (1934)

The global economic crisis led to internal political instability in the Third Republic, which culminated in the bloody unrest of February 6, 1934 and led to the overthrow of the Édouard Daladier government. President Albert Lebrun thereupon instructed the conservative Gaston Doumergue on February 8th to form a new government of the Union Nationale . Doumergue, in turn, asked Pétain to accept the post of Minister of War , because in his opinion the person of the marshal, respected in all political camps, represented a pledge in the new cabinet to reassure war veterans (e.g. Jeunesses patriotes , Croix de Feu ).

After his final entry into civil politics, Pétain faced the usual difficulties in ministries and struggled with the most important, the budget allocated to his division . The financial situation in France was tense and required austerity measures. Pétain, who as a soldier had shown concern about German rearmament , had to approve a reduction in military credits as minister. A bill to extend compulsory military service to 24 months also failed to find a parliamentary majority. In relation to the foreign policy course of Foreign Minister Louis Barthou , who wanted to bind the Eastern European states to France ( Pacte de l'Est ), Pétain was extremely critical with regard to the military strength of these states. With the assassination of Barthou and the Yugoslav king Alexander I on October 9th in Marseilles , this endeavor suddenly came to an end, and the government fell into a crisis. As an envoy from France, Pétain traveled to the funeral ceremony in Topola and met the German representative Hermann Göring , about whom he commented positively afterwards.

The Doumergue government failed after nine months in office on November 8, 1934. It had introduced a revision of the constitutional laws of 1875 to strengthen executive power over the legislature, but did not receive a majority in the Chamber of Deputies .

Ambassador to Spain

After the recognition of the nationalist Franco Spain by the French government to Marshal Pétain was extraordinary on March 2, 1939 Ambassador appointed France in Spain and handed interior minister Ramón Serrano Suñer on March 24 in Burgos his accreditation letter . Due to his successes during the Rif War, Pétain enjoyed a great reputation in the neighboring country and was supposed to guarantee the neutrality of Spain in view of the impending conflict with the German Reich , which operated an aggressive foreign policy. After the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, Pétain turned down Prime Minister Édouard Daladier's offer to join the French War Cabinet and remained in Spain as ambassador.

The 1940 defeat

Entry into government

With the German attack in Western Europe on May 10, 1940, the phase of the drôle de guerre ended . By bypassing the Maginot Line, German tank units passed the Ardennes , after the unexpected breakthrough at Sedan on May 15, they crossed the Meuse and advanced to the English Channel ( sickle cut plan ). Just a few days after the start of the fighting, France found itself in a serious military and political crisis, which is why Prime Minister Paul Reynaud was forced to reshuffle the cabinet. He added the War Department to his portfolio, appointed Georges Mandel as Minister of the Interior and contacted Philippe Pétain, who on May 18 agreed to join the cabinet as deputy head of government . Reynaud replaced the hapless Commander-in-Chief Maurice Gamelin with Maxime Weygand . With the entry into government of the now 84-year-old Pétain, who was a symbol of perseverance during the First World War, Reynaud hoped to strengthen morale and the willingness to defend himself. In a radio address he stated:

“The Verdun winner, Marshal Pétain, returned from Madrid this morning. He will stand by my side [...] put all his wisdom and all his strength into the service of our country. He will stay there until the war is won. "

The appointment of the popular Marshal found in French public very well received and has been called "divine surprise" (heavenly surprise) welcomed hopefully. The writer François Mauriac wrote: “This old man was sent to us by the dead from Verdun.” The military situation, however, deteriorated almost daily, because the Western powers could not offer an effective defense against the Blitzkrieg , and the rapid German advance to the Channel coast closed most of the Allies Armed forces enter northern France ( Battle of Dunkirk ). During the meeting of the British-French War Council on May 25, Pétain took a defeatist stance . France was poorly prepared for the war and he blamed political decision-makers for the impending defeat. The marshal was not ready to take the fight to the extreme:

“I cannot allow the mistakes of politics to be passed on to the army […] It is easy and stupid to say that one will fight to the last man. It's better not to say something like that and not do it either. After our losses in the last war and our low birth rate, this is also a crime! "

After the defeat in Dunkirk and the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force ( Operation Dynamo ), the Wehrmacht prepared its attack on Paris ( Red Case ). The hastily erected Weygand Line , an interception position for the French south of the Somme and Aisne, could not stop the German advance. The French army was on the verge of collapse, millions of internally displaced civilians and the increasing panic of war dissolved public order. On June 10, the French constitutional organs left the capital and fled to Bordeaux via Tours . Paris, which was declared an open city , was occupied by the Germans on June 14th without a fight. Against this background, Commander-in-Chief Weygand appealed to the government to put an end to the destruction of the army and to ask the Germans to announce the terms of the armistice. There was disagreement in the cabinet on this, and two opposing views emerged: Prime Minister Reynaud and Charles de Gaulle, State Secretary in the War Ministry since June 6 , pleaded for a continuation of the military resistance. If necessary, the government should entrench itself in the "Fortress Bretagne " or move to North Africa in order to use this as a basis for further struggle. Pétain, however, considered a continuation of the war to be hopeless and supported Weygand's demand for a quick end to the fighting. Contrary to all alliance obligations towards Great Britain, he insisted as the most consistent advocate for the conclusion of a separate peace with the German Reich . To clarify his position, Pétain read a statement during the cabinet meeting on June 13:

“It is impossible for the French government to leave French soil without emigrating, without deserting. I believe that French soil must not be abandoned and that the suffering that awaits the fatherland and its sons must be accepted. The French rebirth will be the fruit of this suffering and the renewal of our country must begin on the spot. We cannot wait for Allied cannons to recapture France at an unknown time and in unforeseen conditions. I will refuse to leave the motherland, I will stay with the French people to share their sufferings and misery - outside the government if necessary. In my opinion, the armistice is the necessary precondition for the continued existence of eternal France. "

armistice

Even after arriving in Bordeaux, Reynaud stubbornly insisted that the army should capitulate while the government should maintain the resistance from exile. Since numerous ministers supported Pétain and the prime minister did not find a majority in the cabinet with his view and Winston Churchill's offer of a British-French state union was rejected, he resigned on the evening of June 16. He recommended Pétain as his successor, who was immediately charged by President Albert Lebrun with the formation of a new government and presented it with a prefabricated cabinet list with 16 ministers and two under-secretaries. With Maxime Weygand (Defense and Chief of Staff), François Darlan (Navy), Bertrand Pujo (Aviation) and Louis Colson (War), four high-ranking military officials, parliamentarians such as Camille Chautemps (Deputy Prime Minister), Jean Ybarnégaray (veterans and family) and Albert Rivière (colonies), also non-party technocrats such as Paul Baudouin (exterior), Yves Bouthillier (finance) and Albert Rivaud (education). His political mentor and confidant Raphaël Alibert he made to the Minister of State , Pierre Laval was not yet part of the government, as you him only the Justice Department , but not the coveted State Department had offered.

Immediately after taking office, Pétain had the Foreign Minister inquire about the terms of an armistice with the German Reich and addressed the population in his first radio address on June 17 at 12:30 p.m. In it he justified his request for armistice negotiations and asked for understanding for this step:

"French people!

Following the call of the President of the Republic, I am taking over the leadership of the French government today. Sure of the trust of the entire people, I place myself at France's disposal to alleviate its suffering […] I tell you today with a heavy heart that it is time to end this struggle. I turned to the enemy that night to ask him whether he was ready, together with us, among soldiers, after the fight and in honor to seek the means to put an end to the hostilities. "

After Pétain's announcement of an armistice with the German Reich, Charles de Gaulle, who fled to Great Britain, called on his country to continue the resistance via Radio Londres ( appeal on June 18 ) and founded the Free French Armed Forces (FFL ). While the German response to the request for an armistice was pending, the idea of a government in exile was taking shape. Former Interior Minister Georges Mandel tried to persuade the head of state, the presidents of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate as well as as many parliamentarians as possible to leave on board the Massilia . In order to secure the legitimacy of his government, Pétain then forbade all holders of public office to leave Bordeaux and threatened to arrest President Lebrun if he tried to leave. Only 27 parliamentarians followed Mandel's call and embarked on June 21 at his side for North Africa. A day later, the armistice negotiators met in the clearing of Rethondes .

Without negotiations, the German leadership dictated to the French delegation on June 22, 1940 the terms of the Compiègne armistice , which was in fact equivalent to a surrender and suspended France's status as a great power . The government accepted the terms of the contract and authorized Général Charles Huntziger to sign it. The fighting then ceased and the ceasefire entered into force on June 25. The treaty divided the territory by a demarcation line into a northern and western part under German military administration (“Zone Occupée”) and an unoccupied southern part (“Zone Libre”) , which covered around 40 percent of the country's area. The German Empire annexed Alsace-Lorraine , the Départements Nord and Pas-de-Calais placed under the military administration in Belgium and northern France . The French state had to pay the cost of the occupation (20 million Reichsmarks per day) ( see: German occupation of France in World War II ). In order to maintain internal order, France was allowed to maintain a 100,000-man army without heavy armament, and the 1.85 million French prisoners of war were only to be repatriated after a final peace had been concluded. The navy, however, was not demobilized , and the internal conditions of the colonies remained untouched.

In accordance with the armistice regulations, the French government retained control of the navy , and although Admiral Darlan had ruled out extradition to the German Reich, Great Britain feared their use on the part of the Axis powers . To prevent this, the British ultimately called for the surrender or demobilization of the French fleet that had called at the naval port of Mers-el-Kébir . After the ultimatum expired on July 3, 1940, the Royal Navy bombed this fleet ( Operation Catapult ), killing 1,297 French navy members. At the same time, all French warships in British ports were captured and confiscated ( Operation Grasp ). Events weighed heavily on Franco-British relations and Darlan demanded a retaliatory attack. Although he was inclined to anglophobia, Pétain proved to be moderate in this situation and rejected Darlan's request. In response, Pétain broke off diplomatic relations with Great Britain on July 5.

Head of State in Vichy

Creation of the État français

After the establishment of the German occupation zone, the Bordeaux government briefly relocated to Clermont-Ferrand, which is overcrowded with refugees . For practical reasons, Pétain finally moved the seat of government on July 1, 1940 to the free zone in Vichy . The health resort , located near the demarcation line, had good road and rail connections and a modern telephone exchange. The numerous hotels offered the ministries, authorities and embassies sufficient accommodation options. Pétain himself moved into two floors of the Hôtel du Parc.

Under the immediate impression of the catastrophic defeat ( "Le Débâcle" ), concrete plans for a comprehensive political reform emerged in the weeks after the armistice. Pétain's supporters, led by Pierre Laval, minister of state and deputy head of government since June 23 , called for constitutional changes. The republic had discredited itself for Laval and he believed that only an authoritarian form of government could integrate France into the victorious totalitarian system . The marshal should be given unlimited powers so that he could begin the reconstruction of the French nation. In a cabinet meeting on July 4, Laval endorsed the immediate convocation of the National Assembly to instruct Pétain to draft a new constitution. Pétain approved the proposal for a legal constitutional reform and announced that the chambers of parliament would be convened for the first time since the conclusion of the armistice. In the days that followed, Laval and Alibert drew up a corresponding bill which should guarantee “the rights of work, the family and the fatherland”. In an atmosphere full of rumors and fears, Laval conducted initial negotiations in the parliamentary environment in Vichy.

Under the chairmanship of Senate President Jules Jeanneney , the deputies and senators constituted themselves on July 10, 1940 as the National Assembly in the Grand Casino de Vichy . Pétain was represented by Laval, who called on the representatives in his speech to gather around the person of the marshal. The members of the National Assembly voted for Laval's bill with a clear majority of 570 to 80 votes (with 21 abstentions and 237 absenteeism).

“ Article 1: The National Assembly grants the Government of the Republic, under the authority and signature of Marshal Pétain, full power to proclaim a new constitution of the French state by one or more acts of law. The constitution will guarantee the rights of work, the family and the fatherland. It will be ratified by the nation and applied by the assemblies of parliament it creates.

The current constitutional law, discussed and adopted by the National Assembly, is to be implemented as a state law.

Done at Vichy, this 10th July 1940 "

On the basis of this general authorization, Pétain promulgated the first four constitutional acts ( “actes constitutionell” ) on July 11th and 12th . These overturned the republican principle of the separation of powers and replaced popular sovereignty with the personal sovereignty of the marshal. They were the foundation of a personal dictatorship and, according to the memories of Pétain's head of cabinet Henri du Moulin de Labarthète , the Marshal was not a little proud of “gaining more power than Louis XIV ever had.” The historian Pierre Bourget described Pétain as “King or regent of France, a king without a crown.” By creating a new executive power, constitutional act No. 1 effectively ended the Third Republic: “We, Philippe Pétain, Marshal of France, hereby declare the functions of the French head of state ( “ Chief de l'État français » ).” Act No. 2 gave Pétain “full power of government”, both legislative and executive , the appointment and dismissal of ministers responsible for him alone , the enactment and implementation of laws , the supreme command of the armed forces, the pardon and amnesty right as well as the negotiation and ratification of treaties. The marshal granted himself judicial powers by being allowed to sit in court over ministers or officials who "had violated their official duties". Court judgments were no longer pronounced in the name of the people, but in that of the "Marshal of France and head of the state". Act No. 3 postponed the two chambers of parliament until further notice. Act No. 4 of July 12th allowed him to appoint the members of the government and the succession in favor of Laval, known as the "Dauphin" . Pétain expanded his cabinet to the right by adding Adrien Marquet (Home Affairs), François Piétri (Communication), Pierre Caziot (Agriculture), and René Belin (Industry). At first he did not appoint a prime minister, Pierre Laval remained deputy head of government.

The État français was therefore authoritarian , reactionary and decidedly anti-democratic. Pétain made the decisions in collaboration with his confidants in an inner circle, without outside involvement. The execution of issued government decrees was the responsibility of the local mayors and regional prefects , who had taken their oath of office on the person of the head of state.

Sections of the French press described the events of July 1940 as the “political hara-kiri of the parliamentarians”, but the shock of the defeat caused no resistance within the population and met with broad approval.

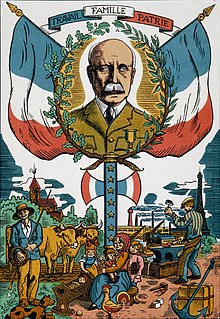

Personality cult

After the events of the summer of 1940, a real myth and personality cult arose around Pétain, which was compared to Joan of Arc and who had sacrificed his person for the good of France. From now on, his portraits replaced the pictures of Marianne in public buildings. The Francisque , consisting of a marshal's baton and two lictors' axes , became the new state symbol . “Nothing without the Marshal. Everything with the Marshal ”became the widespread slogan, the song “ Maréchal, nous voilà ”played as the unofficial national anthem after the Marseillaise . Vichy developed into a political place of pilgrimage around him. He was referred to as Our Father , Our Marshal, or the Father of all the Children of France .

The Catholic clergy in France also supported the new regime. On July 16, 1940, Cardinal Pierre-Marie Gerlier traveled to Vichy to express his respect for the sacrifice that Pétain was bringing to the fatherland.

Révolution Nationale

“From now on we have to direct our efforts towards the future. A new order begins ”, Philippe Pétain had explained to the French on June 25, 1940. He interpreted the military defeat as a sign of a process of disintegration in French society and lamented both the internal turmoil in the country and the decline in traditional values. Since the armistice, Pétain campaigned for a spiritual and moral turnaround ( "redressement intellectuel et moral" ) and wanted to lead it to new unity and moral renewal in a national revolution . Under the slogan “ Travail, Famille, Patrie ” (work, family, fatherland) , the Vichy regime firmly supported the principles of the French Revolution “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité” (freedom, equality, brotherhood) and the republican principles that grew out of it Tradition. The aim was to return to a traditional, patriarchal and hierarchical form of society and to renew it morally.

“The National Revolution is not directed against political oppression, but against an outdated order. It takes place on the morning after the defeat, seven years after the German revolution, eighteen years after the Italian revolution, and in a completely different spirit than these two historical revolutions ”

collaboration

After intensive diplomatic preparation by Pierre Laval and the German ambassador Otto Abetz , Pétain met Adolf Hitler in person on October 24, 1940 in Montoire-sur-le-Loir . Opposite this, the marshal refused to allow his country to enter the war on the side of the Axis powers . In return Pétain made an offer of cooperation ( collaboration ), which he considered necessary to ensure the supply of the population, the nature and scope of the material, human and industrial exploitation of France to keep in check and the return of the French soldiers from German prisoner of war to to reach. On October 30, Pétain justified his policy in a radio address:

“I met the Chancellor of the German Reich last Tuesday [...]. Of my own free will, I accepted the Fuehrer's invitation. I did not experience any “dictation” or pressure from his side. A collaboration between our two countries has been envisaged. I have basically accepted this. [...]

I take the path of collaboration with honor to preserve the unity of France - a unity of ten centuries - and this is done in the context of building a new European order. [...] This collaboration has to be sincere. It must exclude all aggressive thinking. It must be borne by a patient and trusting effort. France is bound by numerous commitments to the winner. At least it remains sovereign. This sovereignty obliges it to defend its soil, settle differences of opinion and lessen the apostasy of its colonies.

This is my policy. The ministers are responsible to me only. History will judge me alone. So far I have spoken to you in the language of your father. Today I am speaking to you in the language of the boss.

Follow me. Keep your trust in eternal France. "

In order to assert the state sovereignty of France and to maintain the colonial empire, Pétain proclaimed the collaboration with the German occupying power. By doing so, he wanted to ease the harsh conditions of the armistice. On the other hand, he pursued a hesitant policy of “direct non-warfare” with the Western Allies until mid-1942, with the aim of maintaining equidistance between the warring parties ( attentism ). Laval, on the other hand, interpreted the Montoire meeting as a Franco-German alliance against Great Britain and he actively campaigned for closer ties to the German Empire, while Pétain - frightened by the forced deportation of Lorraine to unoccupied France ( Wagner-Bürckel action ) - campaigned adhered to his swing policy. The ongoing conflict led to a trial of strength and Pétain relieved Laval of his offices on December 13, 1940 and had him arrested. Due to sharp German intervention, Laval had to be released.

Because of state collaboration, authoritarian domestic politics and increasing German reprisals , the Vichy regime noticeably lost support in the population from 1942 and became increasingly dependent on the German Reich. The establishment of a volunteer legion to support the Wehrmacht in the fight against Bolshevism in the Soviet Union radicalized the communist resistance in France and brought the Resistance a lively popularity. In response to German pressure and against the US Council , Pétain reappointed Pierre Laval as his deputy and head of government on April 18, 1942, and as a result Laval rose to be the most important decision-maker of the Vichy regime. The decidedly German-friendly Laval intensified the collaboration by organizing the increased provision of French forced laborers for the German war economy and the deportation of Jews . To this end, he founded the Milice française, a paramilitary unit that worked closely with the German occupying forces.

When, in November 1942, after the Allies landed in North Africa, an attack on “Fortress Europe” became apparent, German and Italian troops occupied the previously unoccupied southern zone of France on November 11th ( company Anton ). Pétain stayed in Vichy, but the occupation largely caused the regime to lose its already low de facto power and finally sank to the status of a German puppet government . Hitler said it was wise to “maintain the fiction of a French government with Pétain. That is why Pétain should be kept as a kind of ghost and let Laval inflate him a little from time to time if he sags a little too much ”. In the last few months, Pétain hardly played a political role, but his authority covered Laval's policies and the measures of the milice.

The end in Vichy

After the Allied landing in Normandy in early June 1944 ( Operation Overlord ), the liberation of France began and the end of the Vichy regime was looming. On August 20, the government was relocated to Belfort and, on German orders, to Sigmaringen in Hohenzollern on September 7 . There she moved into quarters in the Hohenzollern Palace and formed a government-in-exile without influence in the "Provisional Capital of Occupied France" . Pétain, who had been forced to leave France, did not participate in this government commission, which now included fascists such as Fernand de Brinon and Jacques Doriot .

In view of the looming military collapse of the German Wehrmacht and to avoid arrest by the advancing French Army , Pétain and his wife left for neutral Switzerland on April 23, 1945 . After diplomatic preparation, he surrendered to the French authorities three days later at the Vallorbe border station and was arrested by Général Marie-Pierre Kœnig . Pétain was imprisoned in Fort de Montrouge near Paris until his trial began .

process

In the course of the cleansing of the state apparatus and public life , the Commission d'Épuration sought to convict leading representatives of the collaboration and the Vichy regime. The court case against Pétain, which received much public attention, opened on July 23, 1945 in the Palais de Justice in Paris . The public prosecutor sued the former head of state before the Haute cour de justice u. a. for “conspiracy against the French Republic and the security of the state” and “collaboration with the enemy”. Pétain, who appeared in the dock in the uniform of a Marshal of France, was defended by lawyers Jacques Isorni , Fernand Payen and Jean Lemaire and commented only once on the allegations. On the first day of the meeting he stated:

“I volunteered to answer to the French people, not the High Court, which does not represent the French people. In my estimation, the armistice saved France, during the four years of occupation I saved the French from the worst through my actions, prepared the liberation and laid the only possible foundations for national resurgence. In condemning me you are prolonging the discord in France. (...) I declare myself innocent and refuse to make any further statements ... "

The jury dropped key points in the indictment in the course of the trial, but maintained the charge of high treason and sentenced Pétain to death on August 15. The guilty verdict had been decided by fourteen votes to thirteen. In view of the condemned's advanced age, 17 of the 27 jurors pleaded for a suspension of the death penalty and recommended commuting to life imprisonment . As provisional head of government , Charles de Gaulle followed the pardon recommendation and converted Pétain's sentence to life imprisonment on August 17th . After the verdict and the revocation of his civil rights, Pétain was initially imprisoned in Fort du Portalet ( Département Pyrénées-Atlantiques ). The Pyrenees fortress had served the Vichy regime as a prison for political prisoners.

End of life

On November 16, 1945, Pétain was relocated to the Atlantic island of Île d'Yeu ( Département Vendée ) and housed as the only inmate in the citadel of Fort de Pierre-Levée . In the course of a questioning by the delegation of a parliamentary committee under the medical presidency, the latter diagnosed the 91-year-old in June 1947 with old age and a memory disorder . For health reasons, Pétain's lawyers and various foreign dignitaries such as the Duke of Windsor and Francisco Franco unsuccessfully requested early release. Due to dementia and heart failure , Pétain's health had deteriorated considerably by 1949. In order to be able to take better care of the patient, he was moved to a private house in the main town of Port-Joinville in June 1951 . Philippe Pétain died there on July 23, 1951 at the age of 95. Two days later he was buried in the local Cimetière communal de Port-Joinville cemetery.

The French government refused his request to be buried in the Douaumont ossuary near Verdun . In order to force a reburial there, the bones of Pétain were stolen by supporters of the Marshal two weeks before the elections for the National Assembly in 1973, found by the police two days later and returned to the Île on February 22, 1973 on the instructions of President Georges Pompidou d'Yeu convicted.

Personal

Philippe Pétain was considered a die-hard bachelor who led an eventful, amorous life and contented himself with fleeting love affairs (" homme à femmes "). He is said to have said to a confidante: "I have had two passions in my life: love and infantry." It was not until 1901 that he asked for the hand of Eugénie Hardon (1877–1962), who was twenty-one years his junior , about their family declined to the humble career of the officer. In 1915, Pétain and the now divorced Eugénie met again and they married on September 14, 1920 in the town hall of the 7th arrondissement of Paris . Best man was his longtime companion Général Émile Fayolle . Annie (or Ninie ) had a son from their first marriage, and the connection with Pétain did not result in any offspring.

In 1920, the Pétain couple moved into an apartment in the Square de La Tour-Maubourg in the posh 7th arrondissement and acquired the Villa L'Ermitage in Villeneuve-Loubet on the Côte d'Azur . On the four hectare property, a tenant tilled the land and looked after the poultry farming . The state court confiscated the owners after Pétain's conviction on August 15, 1945.

Afterlife

Since Pétain was still considered a war hero in large parts of the population and, above all, the political and military elite, for years he was seen more as a victim of the German occupation and emphasized that his regime also acted as a "protective shield" against National Socialist Germany for all its mistakes have. The crimes of the regime, such as the deportation of French Jews , were either kept secret or ascribed to other Vichy functionaries. The historian Henry Rousso referred to this in 1987 as the "Vichy Syndrome". Even François Mitterrand (the first socialist president, 1981-1995) rose in 1987 as all his predecessors a rose in memory of Petain at Fort Douaumont (Verdun) down; when this became public in 1992 it sparked a scandal. It was only Mitterrand's successor, Jacques Chirac , who condemned the crimes of the regime and named the French state responsible for them.

In some right-wing national to right-wing extremist circles, such as the Rassemblement National (RN), Pétain is still considered a hero. However, the current party leader Marine Le Pen, unlike her father and former party leader Jean-Marie Le Pen, avoids the issue.

Publications (selection)

- Actes et écrits . Flammarion, Paris 1974 (2 vol.).

- La bataille de Verdun . Édition Avalon, Paris 1986, ISBN 2-906316-02-4 (reprint of the Paris 1929 edition).

- Discours aux Francais. June 17, 1940–20 August 1944 . Albin Michel, Paris 1989, ISBN 2-226-03867-1 .

literature

- Ansbert Baumann: A national hero in court. Philippe Pétain is sentenced to death. In: THEN. The magazine for history and culture . Issue 8/2010, pp. 10-13.

- Gérard Boulanger: A mort la Gueuse! Comment Pétain liquida la République à Bordeaux, 15, 16 and 17 June 1940 . Calmann-Lévy, Paris 2006, ISBN 2-7021-3650-8 .

- Pierre Bourget: The Marshal. Pétain between collaboration and resistance. ("Un certain Philippe Pétain"). Ullstein Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1968.

- Christiane Florin : Philippe Pétain and Pierre Laval . The image of two collaborators in French memory; a contribution to coming to terms with the past in France between 1945 and 1995. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-631-31882-0 (also dissertation, University of Bonn 1996).

- Günther Fuchs among others: Becoming and passing away of a democracy France's Third Republic in nine portraits. Léon Gambetta , Jules Ferry , Jean Jaurès , Georges Clemenceau , Aristide Briand , Léon Blum , Édouard Daladier , Phillipe Pétain, Charles de Gaulle. Universitätsverlag, Leipzig 2004, ISBN 3-937209-87-5 .

- Henry d'Humières: Philippe Pétain, Charles de Gaulle et la France. Lettres du Monde, Paris 2007, ISBN 978-2-7301-0212-4 .

- Pierre Pelissier: Philippe Pétain. Hachette, Paris 1980, ISBN 2-01-005746-5 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Philippe Pétain in the catalog of the German National Library

- Henri Philippe Pétain 1856-1951 (LEMO)

- Short biography and list of works of the Académie française (French)

- Newspaper article about Philippe Pétain in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- "It was unthinkable to execute Philippe Pétain" (NZZ July 25, 2020)

Individual evidence

- ^ Herbert R. Lottman: Pétain. Éditions du Seuil, Paris 1984, ISBN 2-02-006763-3 , p. 13.

- ↑ Pierre Bourget: The Marshal. Pétain between collaboration and resistance. Ullstein Verlag, 1966. p. 28.

- ↑ gw.geneanet.org

- ^ Herbert R. Lottman (trad. Béatrice Vierne): Pétain, Éditions du Seuil. Paris 1984.

- ↑ Hervé Bentegeat: "Et surtout pas un mot à la Maréchale". Pétain et ses femmes. Albin Michel, 2014, p. 230.

- ^ Robert B. Bruce: Pétain: Verdun to Vichy (Military Profiles) . Potomac Book, 2008, ISBN 978-1-57488-757-0 .

- ↑ Richard Griffiths: Marshal Pétain . Faber and Faber, 2011, ISBN 978-0-571-27814-5 .

- ^ A b Nicolas Atkin: Pétain . Longman, Harlow 1997, ISBN 0-582-07037-6 .

- ^ Robert B. Bruce: Pétain: Verdun to Vichy (Military Profiles). Potomac Book, 2008, ISBN 978-1-57488-757-0 .

- ^ Nicolas Atkin: Pétain. Longman, Harlow 1997, ISBN 0-582-07037-6 , p. 5.

- ^ Henry du Moulin de Labarthète: Le Temps des illusions - Souvenirs (July 1940 – April 1942). Ed. La diffusion du livre, 1947, p. 97.

- ^ Robert B. Bruce: Pétain: Verdun to Vichy (Military Profiles). Potomac Book, 2008, ISBN 978-1-57488-757-0 , p. 54.

- ^ Charles Williams: Pétain. London 2005, ISBN 978-0-316-86127-4 , p. 206.

- ^ Robert B. Bruce: Pétain: Verdun to Vichy (Military Profiles). Potomac Book, 2008, ISBN 978-1-57488-757-0 .

- ^ Robert B. Bruce: Pétain: Verdun to Vichy (Military Profiles). Potomac Book, 2008, ISBN 978-1-57488-757-0 , p. 17.

- ↑ Pierre Bourget: The Marshal. Pétain between collaboration and resistance. Ullstein Verlag, 1966. p. 56.

- ↑ Guy Pedroncini: Pétain, 1856-1918 - Le soldat et la gloire. Perrin, 1989.

- ↑ Richard Griffiths: Marshal Pétain. Faber and Faber, 2011, ISBN 978-0-571-27814-5 .

- ↑ Nicholas Atkin: Pétain. Routledge, London / New York 2014, ISBN 978-1-315-84547-0 , p. 14.

- ^ Sven Lange: Hans Delbrück and the "strategy dispute". Warfare and War History in the Controversy 1879–1914. Rombach, Freiburg im Breisgau 1995, ISBN 3-7930-0771-5 , p. 129.

- ↑ Jost Dülffer: Making Peace. De-escalation and peace policy in the 20th century. Böhlau, Cologne / Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-412-20117-3 , p. 191.

- ↑ Richard Griffiths: Marshal Pétain. Faber and Faber, 2011, ISBN 978-0-571-27814-5 .

- ^ Robert B. Bruce: Pétain: Verdun to Vichy (Military Profiles). Potomac Book, 2008, ISBN 978-1-57488-757-0 .

- ↑ Pierre Bourget: The Marshal. Pétain between collaboration and resistance. Ullstein Verlag, 1966. p. 71.

- ^ Nicolas Atkin: Pétain. Routledge, London / New York 2014, ISBN 978-1-315-84547-0 , p. 20.

- ^ Francois Caron: France in the Age of Imperialism 1851-1918 (= History of France. Vol. 5). DVA, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-421-06455-5 , p. 600.

- ^ Mutiny in the French Army. historylearningsite.co.uk. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ^ LaGarde, Lieutenant Benoit: Grand Quartier Général 1914–1918. Sous series GR 16 NN - Répertoire numérique détailleé (French). Service historique de la Defense .

- ↑ Guy Pedroncini: Les Mutineries de 1917. Presses universitaires de France (PUF), Paris 1967 (new edition 1999).

- ^ Leonard V. Smith: France. In: John Horne (Ed.): A companion to World War I. Wiley-Blackwell, Malden, Mass. u. a. 2010, ISBN 978-1-4051-2386-0 , p. 425.

- ↑ Arlette Estienne Mondet: Le général JB E Estienne - père des chars: Des chenilles et des ailes. Editions L`Harmattan, 2011, p. 159.

- ↑ Pierre Bourget: The Marshal. Pétain between collaboration and resistance. Ullstein Verlag, 1966. P. 91/92.

- ↑ Richard Griffiths: Marshal Pétain. Faber and Faber, 2011, ISBN 978-0-571-27814-5 .

- ^ Robert B. Bruce: Pétain: Verdun to Vichy (Military Profiles). Potomac Book, 2008, ISBN 978-1-57488-757-0 , p. 60.

- ^ Robert B. Bruce: Pétain: Verdun to Vichy (Military Profiles). Potomac Book, 2008, ISBN 978-1-57488-757-0 , p. 63.

- ^ Robert B. Bruce: Pétain: Verdun to Vichy (Military Profiles). Potomac Book, 2008, ISBN 978-1-57488-757-0 , p. 64.

- ^ Marc Ferro: Pétain (= Pluriel ). Hachette, Paris 2009, p. 789.

- ↑ Pierre Bourget: The Marshal. Pétain between collaboration and resistance. Verlag Ullstein, 1966. p. 110.

- ^ Robert B. Bruce: Pétain: Verdun to Vichy (Military Profiles). Potomac Book, 2008, ISBN 978-1-57488-757-0 .

- ^ Robert B. Bruce: Pétain: Verdun to Vichy (Military Profiles). Potomac Book, 2008, ISBN 978-1-57488-757-0 , p. 42.

- ^ Robert B. Bruce: Pétain: Verdun to Vichy (Military Profiles). Potomac Book, 2008, ISBN 978-1-57488-757-0 , p. 43.

- ↑ Guy Pedroncini: Pétain, le soldier, from 1914 to 1940. 1998, p. 339; see also: Guy Pedroncini: Remarques sur les grandes décisions stratégiques françaises de 1914 à 1940 ( Wikiwix ).

- ↑ Alistair Horne: To lose a battle. France 1940. New York 1979.

- ↑ Richard Griffiths: Marshal Pétain. Faber and Faber, 2011, ISBN 978-0-571-27814-5 .

- ^ Exposé d'une organization des nouvelles frontières de la France , April 1919 and Exposé d'une organization des frontières de la France , end of 1919.

- ^ Paris daily newspaper. Vol. 1, 1936, No. 148, November 6, 1936, p. 2, column.

- ^ Raymond Cartier: The Second World War. Volume 1. Lingen Verlag, 1967, p. 37.

- ↑ Eric Roussel: De Gaulle. Volume I: 1890-1945. Éditions Gallimard, Paris 2002, quoted from the paperback edition: Éditions Perrin, p. 61 ff.

- ^ Herbert R. Lottman (transl. Béatrice Vierne): Pétain. Editions du Seuil. Paris 1984.

- ↑ Richard Griffiths: Marshal Pétain. Faber and Faber, 2011, ISBN 978-0-571-27814-5 .

- ↑ España y sus bombas tóxicas sobre Marruecos. In: El Mundo. July 5, 2008.

- ^ Stefan Grüner: Paul Reynaud (1878-1966): Biographical studies on liberalism in France. Munich 2001, p. 164.

- ^ Matthias Waechter: The Myth of Gaullism: Hero Cult, History Politics and Ideology 1940-1958. Göttingen 2006, p. 38.

- ↑ Pierre Bourget: The Marshal. Pétain between collaboration and resistance. Ullstein Verlag, 1966. p. 44.

- ↑ Richard Griffiths: Marshal Pétain. Faber and Faber, 2011, ISBN 978-0-571-27814-5 .

- ↑ Pierre Bourget: The Marshal. Pétain between collaboration and resistance. Ullstein Verlag, 1966. p. 117.

- ^ Raymond Cartier: The Second World War. Volume 1. Lingen Verlag, 1967, p. 179.

- ↑ Alistair Horne: To lose a battle. France 1940. New York 1979.

- ^ Raymond Cartier: The Second World War. Volume 1. Lingen Verlag, 1967, pp. 181/182.

- ^ A b Raymond Cartier: The Second World War. Volume 1. Lingen Verlag, 1967, p. 196.

- ↑ Medard Ritzenhofen: A spark - not a flame of resistance. De Gaulle's appeal of June 18, 1940 and its effects. Ingo Kolboom : Nation and Europe. Charles de Gaulle - as a symbol for a misunderstanding. Ernst Weisenfeld : Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals. A magic formula - a vision - a policy. Pierre Maillard: Germany with France - an "unfinished dream". In: Documents / Documents. Journal for the Franco-German Dialogue (PDF; 15.63 MB).

- ^ Raymond Cartier: The Second World War. Volume 1. Lingen Verlag, 1967, p. 200.

- ^ Jean Lacouture: De Gaulle: The Rebel 1890-1944. 1984 (English edition 1991), 640 pp. Volume 2: De Gaulle: The Ruler 1945–1970. 1993, 700 pp., The standard scholarly biography.

- ^ Roman Schnur: Vive la République or vive la France. On the crisis of democracy in France in 1939/40. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1982, p. 20.

- ↑ Philippe Petain on Lignemaginot.com.

- ↑ on writing 'to the enemy' see the OKW's war diary. Volume IS 965.

- ^ Raymond Cartier: The Second World War. Volume 1. Lingen Verlag, 1967, p. 223.

- ↑ Götz Aly: Hitler's People's State. Robbery, Race War and National Socialism. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2005, p. 170.

- ^ Roman Schnur: Vive la République or vive la France, Duncker & Humblot, ISBN 3-428-45285-2

- ^ Nicolas Atkin: Pétain. Longman, Harlow 1997, ISBN 0-582-07037-6 .

- ^ Henry Rousso: Vichy, France under German occupation; CH Beck, ISBN 978-3-406-58454-1

- ↑ Roll- call voting results in the minutes on the website of the French National Assembly (PDF; 3.1 MB).

- ↑ http://www.verfassungen.eu/f/fverf40.htm

- ^ Loi constitutionnelle du 10 juillet 1940 ( Digithèque MJP ).

- ^ Jäckel, France in Hitler's Europe, p. 85.

- ↑ Julian Jackson; France: The Dark Years, 1940-1944. Oxford University Press. Pp. 124-125, 133. ISBN 0-19-820706-9 .

- ↑ Pierre Bourget: The Marshal. Pétain between collaboration and resistance. Ullstein Verlag, 1966. p. 219.

- ^ Henry Rousso: Vichy, France under German occupation; CH Beck, ISBN 978-3-406-58454-1 , p. 31.

- ^ Henry Rousso: Vichy, France under German occupation; CH Beck, ISBN 978-3-406-58454-1 , p. 31.

- ↑ Régime de Vichy 1940-1944

- ^ Ministries, political parties, etc. from 1870 (rulers.org)

- ↑ Richard Griffiths: Marshal Pétain. Faber and Faber, 2011, ISBN 978-0-571-27814-5 .

- ^ Raymond Cartier: The Second World War. Volume 1. Lingen Verlag, 1967, p. 272.

- ↑ Charles Sowerwine: France since 1870. Culture, Society and the Making of the Republic. Palgrave Macmillan, London 2001/2009, pp. 190/191.

- ^ Robert B. Bruce: Pétain: Verdun to Vichy (Military Profiles) . Potomac Book, 2008, ISBN 978-1-57488-757-0 , p. 67.

- ^ Henry Rousso: Vichy, France under German occupation; CH Beck, ISBN 978-3-406-58454-1 , p. 32.

- ↑ OKW War Diary, Volume I, p. 130 (October 28, 1940)

- ^ Pétain, Philippe: Address on the “collaboration” (October 30, 1940). European history thematic portal.

- ↑ See Eberhard Jäckel : France in Hitler's Europe: the German French policy in World War II. Stuttgart 1966, p. 260 f.

- ↑ deutschlandfunk.de

- ↑ Paxton RO: La France de Vichy 1940-1944, Nouvelle Édition. Paris, Édition du Seuil, 1997, p. 76.

- ^ Herbert R. Lottman (trad. Béatrice Vierne): Pétain. Éditions du Seuil, Paris 1984, ISBN 2-02-006763-3 .

- ^ Charles Williams: Pétain . London 2005, ISBN 0-316-86127-8 , p. 206.

- ↑ Time Magazine , March 1973.

- ^ Tomb of Pétain

- ↑ Pierre Bourget: The Marshal. Pétain between collaboration and resistance. Ullstein Verlag, 1966. p. 115.

- ^ Herbert R. Lottman (trad. Béatrice Vierne): Pétain. Éditions du Seuil, Paris 1984, ISBN 2-02-006763-3 , pp. 120–122: “[…] Pétain épousait Alphonsine Berthe Eugénie Hardon […]”.

- ↑ archives.nicematin.com

- ↑ Pierre Bourget: The Marshal. Pétain between collaboration and resistance. Ullstein Verlag, 1966. p. 137.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Joseph Paul-Boncour |

Minister of War of France February 9 - November 8, 1934 |

Louis Maurin |

| Eirik Labonne |

French Ambassador to Spain March 11, 1939 - May 18, 1940 |

François Piétri |

| Paul Reynaud |

Prime Minister of France June 16-July 11, 1940 |

Pierre Laval |

| Albert Lebrun |

French President July 11, 1940 - August 20, 1944 |

Charles de Gaulle ( provisional ) |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pétain, Philippe |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Pétain, Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French general and President of the Vichy regime |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 24, 1856 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cauchy-à-la-Tour, Pas-de-Calais department |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 23, 1951 |

| Place of death | Île d'Yeu |