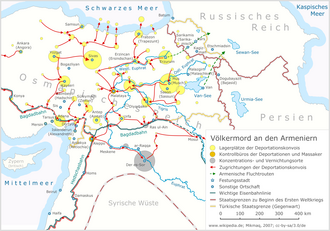

Genocide against the Armenians

The Armenian genocide was one of the first systematic genocides of the 20th century. It happened during the First World War under the responsibility of the Young Turkish government of the Ottoman Empire formed by the Committee for Unity and Progress . In massacres and death marches , which mainly took place in 1915 and 1916, between 300,000 and more than 1.5 million people died, depending on the estimate. Estimates of the number of Armenians killed during the persecution of the previous two decades vary between 80,000 and 300,000.

The events, which the Armenians themselves use the term aghet ("catastrophe") to refer to, are documented by extensive documentary material from various sources. The vast majority of historians around the world therefore recognize this genocide as a fact. The Armenians see in him an unpunished injustice and have been demanding appropriate remembrance in Turkey for decades . On the other hand, official Turkish historiography and the government of the Republic of Turkey, which emerged from the Ottoman Empire, deny that it was genocide. They describe the deportations as "war-related security measures" that had become necessary because the Armenians betrayed the Ottoman Empire, supported those who were opponents of the war and, in turn, committed massacres of Muslims. They attribute the deaths to unfavorable circumstances and only isolated attacks. The dispute over the recognition of the genocide as a historical fact still strains the relations between Turkey on the one hand and Armenia and numerous Western states on the other.

prehistory

Social structure and demographics

The Armenians formed the second largest Christian minority in the Ottoman Empire after the Greeks. Its non-Muslim population groups were in Millets according to their religious affiliation - i. H. organized in recognized, legally protected "faith nations". From the Ottoman point of view, the Armenians were traditionally regarded as a “loyal nation” (Ottoman: millet-i sadika ), were able to practice their faith without significant restrictions, and within the Ottoman state had the opportunity to acquire honor, prosperity and status. Nevertheless, like Orthodox Greeks, Jews and other religious minorities, they were not treated on an equal footing with Muslims. They had to pay an additional poll tax , which was graded according to wealth, called cizye , which was increased in 1856 by a military exemption tax ( bedel-i askerî /بدل عسکری) has been replaced. They were legally underprivileged and sometimes exposed to discriminatory treatment.

Around 1800 the majority of the Armenians lived under Ottoman rule. Their main settlement areas were in the Ottoman Empire

- in what is now Eastern Anatolia - in the area of Erzurum , Kars , Van and Diyarbakır ,

- in Cilicia near Adana and Maraş ,

- in the Ottoman metropolises Alexandria , Smyrna (İzmir) and especially in Constantinople .

Before the First World War, the Armenians made up 1.7 million people, about ten percent of the population of Anatolia . The number of Muslims in no Vilayet (Greater Province) exceeded that of the Muslims. This was in 1896 only a few Kazas (jurisdictions) of the Sanjak Van and Siirt (Saird or Sartu District) the case. As a minority, however, they could not be overlooked. The Turkish government later put their number at 1.3 million. The Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople , on the other hand, assumed that there were almost 2 million church members in the Ottoman Empire, according to a census that it held in its congregations in 1913/14.

Ottomans and Armenians in the second half of the 19th century

Attempts at reform, nationalism and escalation of the domestic political situation

In the 19th century, the multi-ethnic Ottoman Empire was in decline. The so-called “ Sick Man on the Bosporus ” fell behind his European rivals economically and militarily. Internally, the awakening national consciousness of its peoples and ethnic groups increasingly disrupted the “delicate balance between official inequality and relative tolerance”.

In the Tanzimat period (1839–1876) the empire tried to reform itself by adopting western concepts. European powers often called for such reforms; in doing so, they were also pursuing their own interests. The Russian Empire, for example, which saw itself as the protective power of the Orthodox and ancient Near Eastern churches in the Ottoman Empire, tried, as part of its expansion policy , to instrumentalize the Anatolian Armenians for destabilizing it. Under the pressure of external events such as the Balkan crisis of 1876, Sultan Abdülhamid II initially continued the reforms of his predecessors and, in Article 61 of the Berlin Treaty of 1878, undertook to protect the Armenians from attacks by the Kurds and give them certain autonomy rights in the course of an administrative reform to grant. These commitments were never implemented, however, because Abdülhamid II, who had only half-heartedly agreed to them anyway, dissolved parliament for an indefinite period during the Russo-Turkish War in February 1878 .

The conflicts that increasingly shaped the relations between the ethnic-religious groups in the 19th century included a permanent land conflict, exacerbated by the settlement of Muslim refugees from the Caucasus and Europe in Eastern Anatolia (especially after 1878), which was often perceived as oppressive Relationship between rural Armenian population and Kurdish local princes and their family clans. The European socialized Armenians in Western Turkey, on the other hand, were characterized in part by a high standard of living and upward social mobility and thus aroused envy and resentment among the Muslims who felt themselves disadvantaged. The sultan as well as the conservative and liberal elites of the empire saw with growing suspicion that a small part of the Armenian ruling class was striving for reforms and seeking protection from European powers. Abdülhamid II was determined to vigorously counter this supposed threat. In the case of the Armenians in the Ottoman eastern provinces, the delay in the reforms promised in 1878 created permanent dissatisfaction. Their efforts for independence intensified, also supported by the political parties that emerged in the 1880s. The moderate party Armenakan Kasmakerputjun (Armenian Organization) was founded as the first in 1885 in Van . In contrast, the Social Democratic Huntschak Party, founded in 1887, and the Bells Party, which themselves considered the use of terrorist means to be justified, made radical demands for independence . In 1890 the Dashnak party was formed , which propagated a people's war against the Ottoman government. In 1890, Armenian terrorists also began targeted murder of Ottoman officials.

The aim of the Daschnak party was to unite all revolutionary forces that had existed until then, but the Huntschak party soon separated from it. The latter lost its effectiveness when it split into two warring camps in 1896. In the period that followed, Dashnak was the main actor in the Armenian revolutionary movement. In addition to the political parties, combat groups of the rural Armenian population sworn by oath emerged from 1885, which saw themselves as "self-protection associations" and called themselves Hajdukner or Fedajiner . In return, the Sultan created irregular cavalry units from 1891 based on the model of the Cossacks and in the tradition of the Akıncı and Deli , which were named Hamidiye in his honor . They were mainly recruited from government-loyal Kurdish tribes and were rewarded with tax exemption and the right to plunder. Officially, they were supposed to protect the borders with Russia, but actually serve as a domestic combat force against the Armenians. To this day (as of 2006) it is unclear whether Abdülhamid II approved or ordered the following massacres of Armenian rebels by the Hamidiyean under his command.

Massacres from 1894 to 1896

Growing nationalism intensified the already long-standing tensions between Armenians and Kurds. This had a cause in the dispute over the so-called kischlak (winter pastures) of the Kurdish pastoral nomads in Armenian villages. In addition, the Kurds collected irregular taxes in the form of money, natural goods or labor from the Armenians, who, like all Ottoman nationals, were under enormous tax pressure. The Ottoman authorities were often unable or unwilling to protect the Armenians from such arbitrary acts. The tensions finally erupted in numerous pogroms against the Armenians in the years 1894–1896.

This was triggered by the successful defense against Kurdish invaders from the region around Diyarbakır by the Armenians von Sason, who were considered to be able to defend themselves, in 1893. They also repulsed another attack, to which the Ottoman authorities had encouraged the Kurds. In the summer of 1894, the Sasun Armenians refused to pay the double tax burden demanded by the government and local Kurdish tribal leaders. Activists from the Huntschak Party tried to take advantage of this tax revolt, which eventually spread to 25 villages, to spark a nationwide uprising. During the resistance of Sason in 1894 there were armed clashes, but there was no general Armenian uprising. Nevertheless, the Ottoman state power struck back with great severity. The Turkish military and irregular Hamidiye units with a strength of around 3,000 stormed the rebellious villages in August after more than two weeks of bloody fighting. They killed between 900 and 4000 Armenians and destroyed 32 of the 40 Armenian villages in the region. Startled by the incidents in Sasun, the other European states increasingly demanded reforms and autonomy for the six eastern vilayets , in which most of the Armenians lived. As these reforms failed again, Great Britain, France and Russia submitted their own proposal to the Ottoman Empire in April 1895.

When the Sultan did not respond, the Huntschak Party organized a protest demonstration in Constantinople on September 30, 1895, which was shot down by the police. Around 20 demonstrators were killed. Incited Turkish counter-demonstrators pursued the fleeing Armenians and killed many of them. Around 3,000 Armenians who had fled to their churches were besieged there for days without the Turkish police intervening. The attacks in the capital only came to an end with the mediation of the Russian embassy.

In Trabzon on the Black Sea there were further massacres of the Armenians with several hundred dead, and the pogroms quickly spread to the highlands. In February 1896, the suppression of an alleged Armenian uprising in Zeytun / Ulnia , today's Süleymanlı near Maraş , was only ended after months of fighting through the mediation of the great powers.

On August 26, 1896 , 25 Dashnaks occupied the Ottoman Bank in Constantinople and took its 160 employees hostage. They demanded autonomy for the Armenian provinces under the supervision of European powers, the release of Armenian prisoners and the return of confiscated property. Although these demands were not met, the hostage-takers were granted free withdrawal to France. As a reaction to this, there were extremely bloody attacks on Armenians by the Turks in Constantinople, claiming 6,000 to 14,000 deaths. All reports from foreign diplomats agreed that the killers were organized and acted in consultation with the authorities. After the massacres of Armenians in Van and the surrounding area in June 1896, others followed in Egin and Niksar in September .

An estimated 80,000 to 300,000 people were killed in the pogroms of 1894–1896. In addition, tens of thousands of homeless Armenians died in the following years from starvation and harsh winters. In 1897 the Armenian Patriarchate counted 50,000 orphans. The Ottoman government restricted the Armenians' freedom of movement between the districts until 1908, which drastically reduced trade. Nevertheless, the massacres of these years "do not fall into the category of genocide [...] The aim was a harsh punishment, not extermination." It was also not a question of so-called ethnic cleansing , since the Armenians were not generally expelled from their home regions, but rather " in their place are repressed "should.

Further development up to the beginning of the First World War

After the end of the great pogroms from 1894 to 1896, the situation between the ethnic groups remained tense, although there were also examples of joint protests by Armenians and Turks against the tax policy of the Sublime Porte . As early as 1904 there was again heavy fighting in the Sasun region , and on July 21, 1905 the Dashnaks carried out an attack on Abdülhamid II . The sultan was unharmed, but 28 people died. Terrorist acts like this reinforced many Turks in their view that the Armenians pose a permanent threat. They aroused or intensified anti-Armenian resentment.

The Armenians initially hoped their situation would improve when the Young Turks came to power . This opposition group, which had formed against the despotic administration of Abdülhamid II, came to power in the course of the constitutional revolution of 1908 and forced the Sultan to reinstate the constitution in the same year . The movement, which consisted of different, sometimes conflicting factions, initially tried to establish a parliamentary-constitutional system of government in the Ottoman Empire, which also granted Christian and non-Turkish Muslim minorities of the multi-ethnic state co-determination or autonomy rights. But authoritarian , nationalistic and Pan-Turkist ideas quickly gained the upper hand among the Young Turks , especially within the Committee for Unity and Progress ( Turkish İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti ). The committee, founded as a secret organization in 1889, soon exercised actual power. In particular, Enver Bey , who later became Minister of War Enver Pasha, striving for the establishment of a "Greater Turkish Turanian Empire" with the involvement of Azerbaijan , Turkestan , and even parts of China. After the English or French name for the organization ( Committee of Union and Progress or Comité Union et Progrès ; abbreviated: CUP ), its members were also called unionists .

In March 1909, Sultan Abdülhamid II's attempt to wrest power from the Young Turks, who had been weakened domestically as a result of the Bosnian annexation crisis, failed . This not only led to his deposition, but also to serious attacks on Armenians in the Cilician Adana and in the surrounding areas. Between 15,000 and 20,000 Armenians died within a few weeks. Although warships from Germany, France, Great Britain, Italy, Austria, Russia and the USA crossed the Cilician coast, their crews did not intervene, although they might have ended the massacres. The execution of 134 “guilty parties” - 127 Muslims and 7 Armenians - ordered by the government in Constantinople - was hardly able to calm the situation in view of the extent of these events.

Due to the defeats of the Ottoman Empire in the Tripoli War and in the First Balkan War , the situation for the minorities worsened again in 1912 and 1913. As a result of the enormous Turkish territorial losses, for which the Committee for Unity and Progress made “disloyal population groups” partly responsible, it radicalized itself strongly. In 1913, the " Young Turkish Triumvirate " Enver Bey , Talât Bey (who later became Grand Vizier Talât Pascha) and Cemal Bey (who later became Minister of the Navy, Cemal Pascha) carried out a coup and established a dictatorial system that was willing to take action against the "internal enemies" in the future. The beleaguered Armenians turned to other countries for help. In particular, Russia, which hoped that this would gain the loyalty of its own Armenian minority and further destabilize the Ottoman Empire, then forced the Young Turkish government to sign the Armenian reform package on February 8, 1914 : The Hamidiye should be disarmed, international observers sent to Eastern Anatolia, regional elections and the regional languages are officially approved.

By the eve of the First World War, the repeated attacks and the associated waves of emigration - especially to the Russian Caucasus regions - had already caused the Armenian population to decline considerably. Between 1882 and 1912 the number of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire had already fallen by a third. When the war broke out in 1914, there was no Armenian majority in any of the eastern Anatolian vilayets - with the exception of Vans .

The genocide

Starting position

On November 14, 1914, the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers in the First World War against the Entente , which included Russia. The Young Turkish government took the opportunity to terminate the hated treaties with foreign countries that restricted the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire: the surrender of the Ottoman Empire , the Administration de la Dette Publique Ottomane and the Armenian reform package. Shortly afterwards, the attacks on Armenian villages began again, both in eastern Anatolia and beyond the borders with Russia and Persia, which were often organized by the Young Turkish "special organization" Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa .

Driven primarily by Pan-Turkish ideas, but also by the desire to recapture the territories that the Ottoman Empire had lost to Russia in earlier wars, the Ottoman government ordered a large-scale offensive in the Caucasus at the end of 1914 . However, this ended at the turn of the year 1914/15 with a devastating defeat in the Battle of Sarıkamış . In the course of the Russian counter-offensive, the empire lost further areas.

Some Armenians supported the Russian army in the hope of independence, and Armenian volunteer battalions fought on the Russian side. Both of these reinforced “the caricature of an alleged Armenian sabotage plan” in the Young Turkish leadership. Although the majority of Armenian civilians and soldiers remained loyal to the Ottoman Empire, the leadership now held the Armenians collectively responsible for the military problems in eastern Anatolia. She took the Russian invasion as a pretext to deport the majority of the Armenian population, which under the given circumstances amounted to “ mass murder ”.

Preparation and triggering factors

When exactly the Young Turkish “Committee for Unity and Progress” made the decision to destroy the Armenians as a whole, it cannot be determined with certainty, since the relevant documents are either missing, inaccessible or never existed. The latter could be due to the conspiratorial nature of the “Committee for Unity and Progress”, which usually issued important orders orally. The initially threatening war situation due to the lost battle of Sarıkamış and the frustration of the Young Turkish leadership are seen as just as important elements in the prehistory of the annihilation as the first Ottoman successes in the Battle of Gallipoli in March 1915. In the period from mid-March to early April 1915 In any case, the decisive prerequisites for the coming events must have been created.

As a first step, the Armenian soldiers of the Ottoman armies were disarmed in February 1915 and then either killed or combined in labor battalions . A little later, the execution of the members of several of these battalions followed. The special unit Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa , led by Bahattin Şakir , was mainly involved in this and the following actions, to which other volunteer formations ( Turkish Çete ) of all kinds must probably be added. This special unit consisted of Kurds, released prisoners and refugees from the Balkans and the Caucasus.

Before the actual deportation law of May 27, 1915, the first deportations took place in Anatolia in February and April, but they were not yet aimed at scheduled extermination and were therefore limited to the transfer of parts of the population from Adana , Zeytun and Dörtyol into the interior. In this context, too, it is not entirely clear when the decision was made to allow the deportations to proceed in such a way that they would lead to the deaths of as many Armenians as possible.

In April 1915 , the Armenians rose up in Van , which resulted in atrocities against the Muslim population. Whether this uprising and the revolutionary violence of the Huntschak activists represented a reaction to the increasing repression or, on the contrary, served as a justification for the central government to start the deportations of the Armenians, is disputed in the research. There were also the so-called Armenian Fedayeen, who from Persia or Russia spread "terror among Turks and Kurds all over Armenia".

procedure

Arrest of the Armenian elite

The genocide began on April 24, 1915 with raids in Constantinople against Armenian intellectuals who were deported to camps near Ankara . The initiative came from Interior Minister Talât Bey, who, against the resistance of colleagues who feared international entanglements, was able to push through with his plan to remove the Armenians from the capital. On April 24 and 25, 1915, 235 people were arrested. According to an official report dated May 24, 1915, the number of those arrested was 2,345. In the files of the Foreign Office of the German Reich, further arrests and deportations of Armenians from Constantinople are mentioned and in some cases described in detail. They happened in the course of 1915 despite the Ottoman government's assurance that it would spare the Armenians of Constantinople. Most of the Armenians in Constantinople were spared, probably because the Young Turks shied away from the attention of the western foreigners who were numerous in Constantinople. April 24th is the official day of remembrance for the Armenian genocide .

Deportations

Now the mass deportations of the Armenians from their traditional residences to the Syrian and Mesopotamian deserts began . The Entente powers reacted quickly and on May 24, 1915, issued a joint declaration condemning the "extermination campaign against the Armenians" as a " crime against humanity " and threatening the members of the Ottoman government involved in it that they would be held accountable pull. In response to this, the Turkish government passed a deportation law on May 27, 1915 , which instructed the security forces to deport the Armenians individually or as a group. The army was charged with the immediate use of extreme military force to suppress opposition or armed resistance to government orders, national defense or public order. There have been reports of deportees' real estate being forcibly transferred by law , and cash and moveable property left behind "seized". There are no known cases in which deportees were compensated for the expropriation. Furniture and objects left in houses were looted. Often gold and jewelry were stolen on the way. Another law forbade giving the Armenians any food.

In Erzurum, Hilmi Bey, the inspector of the "Committee for Unity and Progress" wired Bahaettin Şakır:

“There are individuals within the country who need to be eliminated. We pursue this perspective. "

In June 1915 the German ambassador Hans von Wangenheim wrote from Constantinople to the German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg :

“It is evident that the exile of the Armenians was not motivated solely by military considerations. The Minister of the Interior, Talaat Bey, recently spoke to Dr. Mordtmann expressed unreservedly that the Porte wanted to use the world war to do away with their internal enemies - the local Christians - without being disturbed by diplomatic intervention from abroad; That is also in the interest of the Germans allied with Turkey, since Turkey would be strengthened in this way. "

Also in June, the Consul General in Constantinople Johann Heinrich Mordtmann reported :

“That can no longer be justified by military considerations; Rather, as Talaat Bej told me a few weeks ago, it is about destroying the Armenians. "

Up until July 1915, most of the Armenians were initially concentrated in their main settlement areas in a few places, mainly in the capitals of the affected vilayets. They were either murdered there by Turkish policemen and soldiers or Kurdish auxiliaries or, on Talat's orders, from May 27, 1915, they were sent on death marches over impassable mountains towards Aleppo . It was not about “resettlement”, as the official Turkish diction is. Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter , the then German Vice Consul in Erzurum, reported on this in a letter to Ambassador Wangenheim at the end of July 1915:

“By the way, the supporters of the latter [ie the 'more rugged direction'] frankly admit that the ultimate goal of their action against the Armenians is the complete extermination of them in Turkey. After the war we will 'have no more Armenians in Turkey' is the literal expression of an authoritative figure. Insofar as this goal cannot be achieved through the various massacres, one hopes that the privations of the long hike to Mesopotamia and the unfamiliar climate there will do the rest. This solution to the Armenian question seems to be an ideal one to followers of the harsh tendency to which almost all military and government officials belong. The Turkish people themselves are by no means in agreement with this solution to the Armenian question and are already having a hard time feeling the economic hardship that is breaking in here as a result of the expulsion of the Armenians over the country. "

In a telegram to Mehmed Reşid , the governor of Diyarbakır , Talât Pasha admitted on July 12, 1915 that there had recently been “massacres” of the Armenians and other Christians deported from Diyarbakır. In Mardin, 700 Armenians and other Christians were brought out of the city at night and "slaughtered like sheep". Overall, the number of those "murdered" in the "massacres" is estimated at around 2,000 people. It is strictly forbidden to “involve” other Christians in the “disciplinary and political measures” against Armenians. Such incidents made a bad public impression, endangered the lives of Christians and should be stopped immediately.

On August 29, 1915, Talât Pasha wrote in an encrypted telegram:

“The Armenian question has been resolved. There is no need to defile the people or the government because of the superfluous atrocities. "

Two days later he declared in the German Embassy in Constantinople that the measures against the Armenians had stopped altogether:

«La question arménienne n'existe plus. »

"The Armenian question no longer exists."

Ernst Jäckh , the well-meaning head of the “Central Office for Foreign Services” in the Foreign Office of the German Reich, said in October 1915 about Talat's role:

"Of course, Talaat made no secret of the fact that he welcomed the extermination of the Armenian people as a political relief."

According to Jäckh, Talât was in contradiction to Finance Minister Mehmet Cavit Bey and the publisher of the government-loyal newspaper "Tanin", Hüseyin Cahit Yalçın: "Jawid and Hussein Jahid always opposed this Armenian policy vigorously, the former especially for economic reasons." but later believed that those who ordered and carried out the deportations saved Turkey.

Interventions and reprimands by the German ambassador on an extraordinary mission in Constantinople, Count Paul Wolff Metternich , in December 1915 with Enver Pascha, Halil Bey and Cemal Pascha, as well as Wolff Metternich's proposal to make the deportations and riots public, were not made by Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg approved:

“The proposed public coramation of an ally during the ongoing war would be a measure that has never been seen before in history. Our only goal is to keep Turkey by our side until the end of the war, regardless of whether the Armenians perish or not. If the war lasts for a long time, we will still need the Turks very much. "

Other foreign envoys also covered the entire scope of the events, such as the US Ambassador Henry Morgenthau , who, based on conversations with the Young Turkish leaders, summed up in his memoir published in 1918:

“When the Turkish authorities gave the orders for these deportations, they were merely giving the death warrant to a whole race; They understood this well, and, in their conversations with me, they made no particular attempt to conceal the fact. […] I am confident that the whole history of the human race contains no such horrible episode as this. The great massacres and persecutions of the past seem almost insignificant when compared to the sufferings of the Armenian race in 1915. "

“When the Turkish rulers gave the instructions for these deportations, they passed a death sentence for an entire race; they were well aware of this, and in their conversations with me they made no attempt to hide this fact. [...] I am sure that the entire history of mankind has not yet seen such a cruel incident. The great massacres and persecutions of the past seem insignificant compared to the sufferings of the Armenian people in 1915. "

Abdulahad Nuri , a senior deportation officer, later confirmed, according to court records, that Talât had told him that the deportations were intended to be exterminated. In the Yozgat procedure, twelve telegrams were read on February 22, 1919. In these telegrams, Nuri's statement that extermination was the goal of the deportation was confirmed several times. District Administrator Nuri, who was later executed in the Bayburt trial for his involvement in the genocide, later testified in court that he had received secret orders not to let any Armenians live. General Vehib Pascha , commander-in-chief of the 3rd Army, told the so-called Mazhar Commission after the war:

“The deportations of the Armenians were carried out in complete contradiction to humanity, civilization and official honor. The massacres and extermination of the Armenians, the robbery and looting of their property were the result of decisions made by the Central Committee of the Committee for Unity and Progress. "

The deportations showed the same basic pattern everywhere: disarmament, elimination of men capable of military service, liquidation of the local leadership, expropriation, death marches and massacres. Resettlement measures were not taken. The Interior Ministry rejected a request from the Governor of Aleppo to provide temporary housing for the deportees. Constantinople strictly refused all offers from other countries to provide humanitarian aid to the deportees during the marches or at their destination. There is no evidence that land was assigned to the deportees at the destination or that other goods were made available to them. Çerkez Hasan (Hasan, the Circassian ), an Ottoman officer responsible for resettling the Armenians in the Syrian and Mesopotamian deserts, resigned in 1915 when he realized that the goal was not resettlement but extermination . The central government took tough measures against governors and district administrators who opposed the deportation orders. The governors of Ankara, Kastamonu and Yozgat were deposed. Ankara's governor, Mazhar Bey , later reported that the reason for his dismissal was his refusal to carry out the interior minister's verbal order to kill the Armenians during the deportation. The district administrators of Lice, Midyat, Diyarbakır and Beşiri as well as the governors of Basra and Müntefak were murdered or executed for this reason. Under Moses Der Kalousdian there was the only successful Armenian resistance on Mosesberg , against which the German liaison officer Eberhard Graf Wolffskeel von Reichenberg, as before in Zeitun and shortly afterwards in Urfa , commanded the artillery attacks.

Military requirements for the deportations are ruled out, as the suspicion of cooperation with the enemy could not extend to women and children and Armenians far from the front, who were also deported directly to the war zone. The deportations also affected almost the entire Armenian civilian population in Anatolia, who generally kept quiet. They were also not the result of a civil war , as there was no centrally controlled nationwide rebellion by the Armenians.

It must have been clear to all those involved and responsible that the "delocalization" (Ottoman tehcîr or teb'îd , تهجير or تبعيد) had to come very close to a death sentence under the conditions of 1915/16. In the camps finally reached in what is now Syria, namely in the Deir ez-Zor concentration camp , the Armenians died from emaciation and epidemics due to lack of supplies. The German military was also involved in the logistics of the deportations, as shown by a deportation order signed by Lieutenant Colonel Böttrich , the head of transport (railway department) at the Turkish headquarters, in October 1915, which affected Armenian workers on the Baghdad railway. In 1918 the German military mission in the Ottoman Empire consisted of 800 officers and 18,000 to 20,000 soldiers. The Baghdad Railway itself and the Anatolian Railway had also previously served to transport captured Armenians. Franz Günther , Vice President of the Anatolian Railway Company, wrote on August 17, 1915 to Arthur von Gwinner , Spokesman for the Board of Management of Deutsche Bank:

"You have to go back a long way in human history to find something similar in bestial cruelty to the extermination of the Armenians in Turkey today."

Günther enclosed a further report to Gwinner with a photograph showing a large number of Armenians crammed into a train. He explained:

"Enclosed I am sending you a picture depicting the Anatolian Railway as a carrier of culture in Turkey. It is the mutton wagons in which, for example, 880 people are transported in 10 wagons. "

In the following two years, the Armenians living in the western Anatolian provinces also gradually became - with the exception of Smyrna, where the German general Liman von Sanders joined forces under threat of military countermeasures against the "with unforeseeable consequences for the victims" according to Graf Spee Mass arrests and deportations took place, and Constantinople, where most of the Armenian residents were largely spared after the arrest and deportation of the Armenian elite - deported or murdered.

The extent of the deportations and the underlying intentions were already clear to observers in 1915: Clara Sigrist-Hilty, a Swiss nurse who had seen a camp in Aleppo, stated that the Armenians would be led around in circles. She also wrote in her diary that young Armenian women were robbed during the marches.

massacre

The deportations were accompanied by massacres of the Armenian civilian population. The trains were repeatedly attacked by Kurdish or Circassian tribesmen. According to Rafael de Nogales , an officer in the service of the Ottoman army and eyewitness to the events, the Armenians were in some places protected and hidden by civilians on the death trains. In other places, the gendarmerie had to protect the column from attacks by the population. "Turkish policemen, gendarmes and soldiers [...] also took part in the killing of the evacuated, partly on the orders of their superiors, partly on their own initiative."

In Trabzon, for example, Armenian women and children were drowned in boats on the instructions of Governor Cemal Azmi . The city's American consul reported that boats were fully loaded and returned empty hours later. The Armenians from Erzincan were tied together in pairs by the Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa in June 1915 and thrown into the Kemach Gorge, killing over 20,000 people - the German consul in Aleppo, Walter Rößler , reported that corpses were washed down the Euphrates for weeks .

consequences

Fatalities

The number of people who fell victim to the massacres and deportations varies, depending on the estimate, between 300,000 and more than 1.5 million. The exact amount is difficult to quantify. The main problem with this is that the population statistics of the Ottoman Empire show serious deficiencies in its last decades. There is no reliable information on how many Armenians lived in the empire before the war. The Armenian Patriarchate put the number of Armenian subjects of the Sultan at around 2.1 million, the last Ottoman census, however, at 1.29 million. Depending on the pre-war number and whether one considers only the main phase of the genocide 1915–1917 or the entire period up to 1923, the estimates range between around 300,000 and 1.5 million dead Armenians.

Gustav Stresemann noted in 1916 after a conversation with Enver Pascha in his Balkan diary: “Armenian reduction 1–1½ million”.

A commission of the Ottoman Minister of the Interior put the number of Armenian victims at 800,000 in 1919. According to a report by US General James Harbord , Mustafa Kemal , who later became Ataturk , also mentioned this number on the occasion of a conversation between the two of them in October 1919. Grand Vizier Damad Ferid Pascha , Mustafa Kemal and the Turkish General Staff also put the number of Armenian victims at 800,000 in a book published in 1928. The Turkish historian and politician Yusuf Hikmet Bayur (1891–1980) wrote that this number was correct.

In a book published in 2006, Raymond Kévorkian estimated, based on the figures of the Patriarchate, the number of those murdered in Asia Minor at around 880,000. He gives the number of those who arrived alive in northern Syria in the summer or autumn of 1915 as 800,000. Around 300,000 other Armenians living in Asia Minor are likely to have managed to escape, hide or otherwise escape deportations and massacres. Thousands more, especially women and children, according to Kévorkian, were eventually brought into Muslim families, where they were forced to convert or raised to become Muslims.

Bernard Lewis sees no evidence that the massacres were the result of a government decision, but nevertheless set the number of victims very high in 2006: "Yes there were tremendous massacres, the numbers are very uncertain but a million may well be likely." there were tremendous massacres; the numbers are very uncertain, but one million is likely. "

The historian Viktor Krieger assumes that just under two million Armenians lived in the Ottoman Empire before the First World War. The population loss as a result of the genocide is between one and one and a half million. However, even the women and children in this number were included that were not murdered, but in Turkey Islamized and türkisiert been or Kurdish Siert.

Flight and Diaspora

During the genocide and in the years after, the Armenian diaspora grew considerably. Although the Young Turks wanted to destroy as many Armenians as possible, it is estimated that up to 600,000 of them had survived the events of 1915-1917. Around 150,000 had escaped the deportations in their original settlement areas, and around 250,000 people survived the death marches and camps. Together with members of other Christian minorities, many of these survivors first made it to the southern parts of the Arab Empire and the Mediterranean coast. From there they later emigrated in large numbers to the USA, Russia, Latin America and Australia or they settled in the countries of the Middle East that were soon to emerge. About as many Armenians and other oriental Christians are likely to have fled to the part of Armenia that belongs to Russia as to the south of the Ottoman Empire. Many Armenians also settled in Abkhazia , where they represent the third largest population group to this day (see Armenians in Abkhazia ).

A large number of Armenians had initially survived in the western provinces of the Ottoman Empire, especially in the big cities. There the Young Turks - probably because of the presence of foreign observers and diplomats - had not dared to act as obviously ruthless as in the east. However, many Armenians were also expelled or killed during the chaotic years of the Turkish Liberation War , including the Smyrna fire . In 1922 it is estimated that there were only about 100,000 Armenians left in Turkey.

In the 1980s, the number of Armenians living in Turkey was given as around 25,000. In addition, there were up to 40,000 so-called crypto - Armenians , i.e. people who denied their Armenian ancestry. Around half of both groups belonged to the so-called Hemşinli , whose main residential areas are between Trabzon and Erzurum .

Material losses

The events from 1915 to 1917 not only claimed countless lives, but also resulted in enormous material losses for the Armenians. Armenian property - land, houses and apartments as well as personal effects of all kinds - was almost always forcibly expropriated without compensation. For the perpetrators, the appropriation of Armenian property was undoubtedly an important incentive. There are no completely reliable sources on the basis of which the Armenian prewar property could be accurately estimated. A report of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919/20 put the losses at 7.84 billion French francs based on the value at the time. This sum corresponded to around 1.8 billion francs from 1914 or 80 million Turkish lira and thus two and a half annual budgets of the Ottoman central government in peacetime.

In principle, Armenian property should go to the state, which used it to “nationalize” the economy, to resettle Muslims in the depopulated areas and to finance the costs of the war. Young Turkish functionaries, local officials and local potentates enriched themselves as well as many simple villagers.

Cultural losses

The cultural loss that went hand in hand with the expulsion and murder of the Armenians cannot even begin to be quantified. Hundreds of Armenian schools, churches and monasteries were looted and destroyed or converted into mosques in the years 1915–1917 and afterwards; many other historical monuments, works of art and cultural assets were destroyed or lost forever. The western Armenian cultural renaissance (Զարթօնք / Zartʻōnkʻ), which began in Smyrna and only fully developed in Constantinople, came to an abrupt end. A pulsating literary life was characteristic of this period. During this period, Constantinople was the place of publication of numerous Armenian newspapers and magazines, and the residence and abode of many Armenian intellectuals, poets and writers such as Daniel Varuschan and Siamanto . Both died in the course of the mass arrest of Armenian intellectuals on April 24, 1915.

Situation of the survivors

Compared to survivors of other genocides, the psychological state of the survivors of the events from 1915 to 1917 is much poorer documented. Oral history projects and corresponding systematic evaluations of the same could be carried out far less often due to the time lag to the events. In addition, the survivors in the diaspora faced a variety of new problems. As socially and culturally uprooted, predominantly rural rural dwellers, they found themselves mostly completely destitute refugees in foreign cities with a completely foreign culture and mentality. In contrast to those of their ethnic group who had fled to the part of Armenia that belonged to Russia, they were safe. For those Armenians who fled to Russian Armenia , however, the horrors went even further. Many of them had already died of starvation and disease during their flight as a result of the privations they had suffered. Tens of thousands more were killed during the attacks by Ottoman forces on the Democratic Republic of Armenia in 1918 and 1920. In the end, both groups had to experience the painful experience that the governments of the former “protective powers” in Western Europe and the USA were ultimately indifferent to their fate even after the First World War and had not taken any concrete steps to help them.

Processing after the First World War

Legal measures

"Unionist Processes" and Political Development up to 1920

Following their announcement of May 24, 1915 that those responsible would be held responsible, France and above all Great Britain put the Ottoman government under pressure after the occupation of Istanbul to punish the murders of the Armenians. Thereupon Sultan Mehmed VI ordered. on December 14, 1918 the criminal prosecution of the Young Turkish functionaries responsible for the genocide, who were to be tried by a military court as a special tribunal . The establishment of an international court favored by Great Britain had already failed in the run-up to the conflicting interests of the Entente powers, especially those of France and Great Britain.

On January 23, 1919, at a conference in London, the Rules of Procedure were established, and on February 5, the trials began. It dealt with the following criminal offenses : violation of the agreements on warfare, attacks against Armenians and members of other ethnic groups as well as robbery, looting and destruction of property. For the first time in legal history, these so-called “unionist trials” represented an attempt to punish state crimes and war crimes at the government level. Numerous regional and local officials, officers and functionaries as well as 31 ministers of the war cabinets who belonged to the "Committee for Unity and Progress" ( Turkish Ittihat ve Terakki Cemiyeti ) were charged. The proceedings against the latter lasted from April 28 to June 25, 1919. The former interior minister and grand vizier Talât Pascha, the former war minister Enver Pascha and the former naval minister Cemal Pascha were also indicted. However, they escaped the trial by fleeing to Germany and were sentenced to death in absentia. In total, the military tribunal pronounced 17 death sentences, three of which were carried out. The processes caused great indignation among the Turkish population, in turn they were seen as necessary concessions in government circles because they hoped to negotiate more favorable peace conditions with the Entente powers and to get them to recognize state sovereignty.

But when the Greek armed forces occupied Smyrna (Izmir) in May 1919 (they stayed there until September 9, 1922), the willingness of the Turkish government to pursue further prosecution quickly waned. After even 41 suspects had been released, the British transferred twelve prisoners to Moudros and 55 more to Malta at the end of May . However, they were later extorted by the Turkish national movement under Mustafa Kemal by threatening British hostages with execution. Mustafa Kemal, who later became Ataturk, had a tense relationship with the three Young Turkish leaders, whom he did not want to see in the ranks of the Turkish national movement as those primarily responsible for the deportations of the Armenians, and at first he had advocated severe punishment. As the situation in the beginning of the Turkish Liberation War became increasingly chaotic and Kemal realized that the Entente powers would not take the Turkish wishes for state sovereignty into account, he too lost interest in prosecuting those responsible for the genocide. This became apparent when, following the proclamation of the Democratic Republic of Armenia, there was Armenian-Turkish fighting and renewed massacres of Armenians. In a speech on April 24, 1920, one day after the opening of the Turkish Grand National Assembly in Ankara, Mustafa Kemal commented on the British demand to prevent this :

“The […] proposal provides that no massacres of Armenians should be carried out in the interior of the country. It is out of the question that these were found in Armenians. We all know our country. On which of its continents were or are massacres of Armenians carried out? I don't want to talk about the phases at the beginning of the [First] World War, and anyway what the Entente states are talking about is of course not an outrage that belongs to the past. With their assertion that such catastrophes are occurring in our country today, they asked us to refrain from them. "

Further political developments and the end of the trials in 1923

In the Treaty of Sèvres , the fifth and last of the Paris suburban treaties signed on August 10, 1920, the Turks were no longer left as a “rump state without actual sovereignty”. The treaty not only provided for the establishment of an Armenian state (in fact this already existed and had also annexed the Ottoman provinces of Eastern Anatolia), the borders of which the US President Woodrow Wilson determined on behalf of the signatory powers of the treaty, but also international control Constantinople and the Straits ( Bosporus and Dardanelles ) as well as the division of the rest of the Ottoman Empire among the Entente Powers and their allies. The Turkish National Assembly in Ankara in particular did not recognize this treaty and now continued its liberation struggle by all means. Initially, their armed forces turned to the Democratic Republic of Armenia and, after heavy fighting, forced their representatives on December 3, 1920 to sign the Treaty of Alexandropol ( Turkish Gümrü ; Armenian Gyumri ), in which today's border was determined. Thus the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres with regard to Armenia were de facto canceled. The result of this treaty was also confirmed in a friendship treaty with the Soviet Union in March 1921.

In the meantime, the Greek troops in the west had taken advantage of the Armenian-Turkish fighting in the east and began their advance into the Turkish interior, accompanied by massacres of the civilian population. However, the troops of the Turkish National Assembly succeeded in defeating the invading army in several battles in the following Greco-Turkish War and driving them back to the Aegean coast . Strengthened in terms of domestic and foreign policy, the Turkish National Assembly under Mustafa Kemal was now able to openly press for a revision of the Treaty of Sèvres, which the Entente powers and their allies, who had meanwhile evacuated large parts of the occupied Turkish territories, finally in the Treaty of July 24, 1923 Lausanne agreed. The judicial prosecution of those responsible for the genocide had long ago come to an almost complete standstill. The criminals interned in Malta had already been released by the British in October 1921, and on March 31, 1923 the Turkish government under Mustafa Kemal issued a general amnesty Turkish Aff-ı Umumi for all those accused of genocide. This step was largely due to the fact that not a few of those who were jointly responsible for the genocide from the ranks of the “Committee for Unity and Progress” belonged to the Turkish national movement under Mustafa Kemal. After the incorporation of their state into the Soviet Union and its conversion to the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Armenians had no diplomatic opportunities to push for the processes to be continued. And the Entente Powers, on the other hand, were no longer interested, because in this case they feared the newly founded Republic of Turkey would merge with the Soviet Union, which they had not recognized.

Operation Nemesis

Apart from the Armenians themselves, after 1921 no one was seriously interested in carrying out the death sentences announced in the Unionist trials and in prosecuting other perpetrators. The Dashnak party therefore set up a secret task force to kill those responsible for the genocide under the code name Operation Nemesis . For example, on March 15, 1921 , the Armenian student Soghomon Tehlirian shot the former Interior Minister Talât Pascha, who was living in exile in Berlin . In the subsequent trial, the Berlin district court acquitted Tehlirian, mainly because of the presentation of the events in Armenia by surviving eyewitnesses such as Bishop Krikor Balakian . Only later did it emerge that Tehlirian was a member of the Dashnaken Sonderkommando. He had already in Constantinople Opel Armenian collaborator Harutiun Mugerditchian (also: Mkrttschjan ) shot, the list of those arrested on April 24, 1915 notables had created.

The murder of Talât was the prelude to a series of attacks in which other people involved in the genocide fell victim. On December 6, 1921, the former Grand Vizier Said Halim Pasha was shot in Rome; On April 17, 1922, two assassins in Berlin liquidated Bahaettin Şakir , the head of Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa , and Cemal Azmi , another Young Turkish leader. On July 21, 1922, Cemal Pascha and his secretary Nusrat Bey were shot by three assassins while walking in Tbilisi . Enver Pasha , who had joined pan-Islamic insurgents in Central Asia, escaped the Avengers, but fell on August 4, 1922 in a battle with Red Army troops in the Pamirs in Tajikistan . Two Azerbaijani politicians were also victims of the series of attacks: Prime Minister Fətəli Xan Xoyski was killed on June 19, 1920 in Tbilisi and Interior Minister Behbud Khan Javanshir on July 18, 1921 in occupied Constantinople.

Recent reviews of the events

Importance to the Armenians

The memory of the genocide represents - next to religion and language - the strongest emotional link that unites the Armenian people, who are scattered over around 120 countries around the world. April 24, the anniversary of the first arrests of Armenian intellectuals in Constantinople, is regularly celebrated as " Genocide Remembrance Day " (Armenian: Եղեռնի զոհերի հիշատակի օր Jegherni soheri hischataki or ) and is one of the most important national holidays of the Republic of Armenia and the Armenian people . Every year hundreds of thousands make the pilgrimage to the Jerern Genocide Memorial on the Yerevan hill Zizernakaberd ("Swallow Fortress "). Millions more worldwide are celebrating the day of mourning. The deep emotional significance of the genocide for the Armenians also explains why Armenian politicians, organizations and lobbies around the world have been fighting so persistently against its trivialization and denial for decades and strive for it to be officially recognized as genocide, i.e. H. based on the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide (officially: English Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide , CPPCG) of 1948.

The struggle of the Armenian people for this recognition was made particularly difficult by the fact that for a long time they did not have their own state that could have served as a platform for it. In the Soviet Union , which was part of Armenia until its dissolution in 1991, the topic was taboo . Only in the so-called " thaw period " after the death of Josef Stalin could it be discussed publicly for the first time. In 1965 there were even public protests in Yerevan , the participants demanding recognition of the genocide. The government of the Armenian SSR did not comply with this demand, but arranged for the Zizernakaberd memorial to be erected in 1967. These and other memorials erected in the 1960s and 1970s are visible evidence of a memorial architecture now tolerated by the Soviet leadership.

During the Cold War , however, there was no political opportunity for the Armenians to make their concerns heard by the international community. The states of the West and especially the NATO -Staaten it did not seem opportune, Turkey - from a geostrategic point of view an important NATO ally - to scare because of this issue. As a result, several terrorist groups formed in the Armenian diaspora, the most active of which was the Asala (Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia) . Using terrorist means, they not only fought against the “crime of silence”, as they called it, but also for the “liberation” of the areas in Turkey that were once inhabited by Armenians. Their attacks claimed a total of 79 lives between 1975 and 1984: 40 Turks, 30 Armenians and nine members of other nationalities. The attacks also brought movement to the issue of recognition: the public was increasingly concerned with it, as did church and political bodies. However, it was only with the emergence of an independent Armenian state and its acceptance into international bodies that the Armenians were given the opportunity to emphasize their wish for the events of 1915 to 1917 to be recognized as genocide, also through political and diplomatic means. Since then, this endeavor has been an integral part of the foreign policy of all Armenian governments.

Rating in Turkey

Damat Ferid Pascha , the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire at the time of the occupation of Istanbul by troops of the victorious powers, publicly admitted the crimes on June 11, 1919. Nevertheless, the denial of the Armenian genocide remains the official policy of all Turkish governments to this day. They describe the deportations as "war-related security measures" that had become necessary because the Armenians betrayed the Ottoman Empire, supported those who were opponents of the war and, in turn, committed massacres of Muslims. They attribute the deaths to unfavorable circumstances and only isolated attacks. They try, with varying degrees of success, to prevent resolutions and publications to the contrary through political pressure and exclusions from international contracts. In Turkey, the genocide is officially described with terms such as Turkish Ermeni soykırımı iddiaları (" Alleged genocide of the Armenians"), Turkish Sözde ermeni soykırımı ("Alleged genocide of the Armenians") and Turkish Ermeni Kırımı ("Armenian massacre"). This attitude repeatedly weighs on Turkey's relations with Armenia and other states that officially recognize the genocide.

Official Turkey does not deny that there have been hundreds of thousands dead. It assumes around 300,000 Armenian victims, but regards the deportations as an emergency measure by a state that had to fear for its existence during the First World War and could not be sure of the loyalty of its Armenian subjects. Some Turkish scientists deny intentional and planned extermination and state that this has not been historically proven.

The official Turkish historiography attributes the many deaths to attacks, hunger and epidemics and refers to the civil war-like conditions in which 570,000 Turks were also killed. Some Turkish scholars and historians of other nationalities such as Erik-Jan Zürcher or Klaus Kreiser regard the Andonian documents , which several scholars cite as evidence of the genocidal intentions of the Young Turks, as forgery . They describe Arnold J. Toynbee's Blue Book and the memoirs of the American Ambassador Henry Morgenthau as partisan. They also criticize the evidence of the Istanbul trials that took place during the Allied occupation and claim that there were a number of Young Turkish decrees to treat the deportees well.

The first Turkish politician after the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey to honor the victims of the genocide by visiting the memorial in Yerevan in June 1995 was Gürbüz Çapan, Esenyurt's social democratic mayor . In 2008, Turkish professors and intellectuals started the Özür Diliyorum (“I apologize”) signature campaign to ask forgiveness from the Armenians.

Internal Turkish critics of the official view must expect legal prosecution due to the controversial Article 301 of the Criminal Code, which, among other things. makes “insulting the Turkish nation” a punishable offense. Journalists such as Hrant Dink, who was murdered in 2007, and the writer and Nobel Prize winner Orhan Pamuk were the main sources of critical examination of the subject . Pamuk was sentenced in March 2011 for violating Article 301 to pay damages to six plaintiffs who felt offended by his statements about the killings of Armenians in 2005 (Pamuk: “The Turks have 30,000 Kurds and one million on this soil Armenians killed. "). The German writer Doğan Akhanlı , who fled Turkey in 1991 , published the novel Kıyamet Günü Yargıçları ( German The Judges of the Last Judgment ) in Istanbul in 1999 . This novel deals with genocide and its official state denial in the Republic of Turkey. Akhanlı was arrested and held in custody while visiting Turkey in August 2010. He was acquitted in October 2011 of his involvement in a robbery and attempted coup. Before the trial he was deported and banned from entering Turkey.

The Turkish governments have made several proposals to have the events scientifically investigated by a joint Turkish-Armenian historians' commission. This proposal was made in 2005 by the Turkish Prime Minister Erdoğan to the Armenian President Robert Kocharyan and in 2007 by the Turkish Foreign Minister Ali Babacan to his Armenian colleague Vartan Oskanjan . The Armenian government rejects this proposal (as of April 2010). In 2010, President Serzh Sargsyan said that the creation of such a body would raise doubts about the fact of the genocide.

Turkey accused France and Russia of passing parliamentary resolutions, but not looking back on their own cruel past with many genocides. For example, when the French National Assembly passed a law in 2006 that was explicitly intended to criminalize the denial of the Armenian genocide, serious diplomatic disputes and economic boycotts by the then Turkish government, Erdoğan I, broke out . When the French National Assembly passed a similar law to combat the denial of the existence of legally recognized genocides in December 2011, the Erdoğan III government reacted in a similarly drastic manner. The law was rejected by the French Constitutional Court in February 2012 (see section “France” ).

On April 24, 2010, a public memorial event for the Armenian victims in Turkey took place in Istanbul for the first time. The date was chosen symbolically; on April 24, 1915, the first 235 Armenians were deported from the Haydarpaşa train station . Organized by the initiative “Irkçılığa ve Milliyetçiliğe Dur de!” (In German: Say stop to racism and nationalism), activists in mourning clothes met on Taksim Square , showed pictures of the deportees and laid flowers.

In 2011, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan ordered the demolition of the sculpture “ Monument to Humanity ” created by Mehmet Aksoy in 2006 to commemorate the genocide.

In a message published the day before April 24, 2014, Erdoğan described it as “a human duty to understand and share the memory of the Armenians of the memory of the suffering the Armenians went through at that time . "Towards the end of the message it says in the text: in the hope of common remembrance of the dead" we wish that the Armenians, who perished under the conditions at the beginning of the 20th century, rest in peace and express our condolences to their grandchildren . ”However, he did not call the acts genocide.

The genocide is still denied in Turkish school books from 2015. In the history book for grade 10 it says on page 212: “With the resettlement law, only those Armenians were removed from the war zone and brought to the safe regions of the country who had participated in the uprisings. This approach also saved the lives of the rest of the Armenian population, because the Armenian gangs killed those of their compatriots who had not participated in the acts of terrorism and uprisings. ”In September 2014, a hundred Turkish intellectuals, including Nobel Prize winner Orhan Pamuk, two demands on the government ( Davutoğlu I ): They should withdraw the history textbooks used so far and apologize to the Armenians.

Evaluation by the Kurds

Kurdish tribes provided numerous members of the guerrilla organization Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa , which was involved in the Armenian massacres. On the other hand, Kurds rescued between 20,000 and 30,000 Armenians from the columns of deportees, especially in the Dersim and Mardin regions , sometimes for financial reasons. In recent years, some Kurdish organizations and politicians, including MP Ahmet Türk , have acknowledged the Kurds' involvement in the massacres and have asked the Armenian people for their forgiveness for the deeds of that time.

Evaluation in history

In historical studies , the deportations and the massacres of the Armenians have been largely assessed as genocide for many years and are considered to be one of the first systematic genocides of the 20th century. These include the works of Wolfgang Gust , Vahakn N. Dadrian and Donald Bloxham , who, based on a wide range of sources from German and American archives, come to the unanimous assessment that the three leading men of the Ittihat ve Terakki Cemiyeti - Enver Pascha, Talât Pascha and Cemal Pascha - set about the murder of up to 1.5 million Armenians. Their goal was on the one hand to eliminate all non-Turkish ethnic groups from Asia Minor, which was to become a "national home" for the Turks ("Türk Yurdu"), and on the other hand, the " fifth column " of Armenians, who were suspected across the board, with the To make common cause for the Russians, to eliminate them. The fact that the persecution of the Armenians in the final phase of the war and in the Turkish-Armenian War of 1920 also continued outside Anatolia, for example in the Armenian pogrom in Baku in 1918 , is seen as evidence that the Turks really want the complete annihilation of all Armenians went. The head of the Berlin Center for Research on Antisemitism, Wolfgang Benz , therefore describes the genocide of the Armenians as typical of the subsequent genocides of the 20th century: They were “staged according to plan and in cold blood”, they were the result of “systematic planning”, ethnic ones were affected , religious or cultural minorities, the persecution began under the “pretext that the majority had been provoked”, the “solution” to the alleged problem was presented as “resettlement, as a peacemaking measure” and was carried out as “displacement, robbery and murder”. In comparison with other genocides such as the one committed against the Armenians, Germans should not lose sight of the singularity of the Shoah .

Some scholars, such as Bernard Lewis , Justin McCarthy and Guenter Lewy , hold the opinion that the deportations and the murders were certainly crimes, but that overall one cannot speak of genocide. The American historian Justin McCarthy, based on demographic statistics, believes that 600,000 Armenians perished during the First World War, that is, 20% of the Armenian population of Anatolia. Of the Anatolian Muslim population, 18% died in the same period, i.e. 2.5 million. The acts of violence were not one-sided, rather a bloody " civil war " had taken place in Eastern Anatolia . According to the German political scientist Herfried Münkler , who does not deny the genocidal character of the Armenian murders, "elements of the [...] civil war" flowed into the conflicts in the Ottoman Empire during the World War, which significantly increased the cruelty "on all sides". For the German-American historian Guenter Lewy, on the other hand, it was by no means a civil war, but neither could one speak of genocide. Genocide presupposes central control, for which there is no authentic source material. Rather, the deportations and the massacres were so improvised and chaotic that central planning was not discernible. As evidence, he cites contradicting orders from the Young Turks and punishments for the murders of Armenians, for example on the deputy Krikor Zohrab . Lewy draws the conclusion: "Under the conditions of the Ottoman disregard, it was possible that even without a deliberate plan of extermination there was such great loss of life in the country."

Aspects of international law

The UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide is decisive for the evaluation of the events of 1915/16 as genocide under international law . Their emergence goes back to these events. The attacks, which killed some of those responsible for the massacre in the early 1920s, drew the attention of the Polish constitutional lawyer Raphael Lemkin to the issue. As a result, he developed the international criminal offense of genocide. After the Second World War and the Holocaust , Lemkin drew up a bill to punish this crime, in which he used the name "genocide", which he had coined earlier. The General Assembly of the United Nations adopted this draft on December 9, 1948, almost unchanged and unanimously. It defines genocide as an act “committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group as such.” For the Republic of Turkey, which signed the convention on July 31, 1950, came into force it entered into force on January 12, 1951. Turkey thereby also recognized the definitions in Articles I and II.

Whether the events from 1915 to 1917 are to be regarded as genocide within the meaning of the UN Convention of 1948 also depends on whether this can even be applied to events before it came into force. The Entente powers, however , viewed the crimes of the Young Turks as early as the First World War - long before the term "genocide" found its way into international law - as a violation of generally applicable legal principles and as serious, punishable crimes. The Treaty of Sèvres explicitly called for the punishment of those responsible for the massacres and deportations and obliged the Ottoman government in Article 230 to extradite the suspects. Article 144 required her to declare the law of 1915, which made Armenian property “abandoned property”, null and void. Although the Treaty of Sèvres was never ratified, there is clear evidence of its relevance in the materials of the United Nations War Crimes Commission on the London Statute of August 1945. There it says

“The provisions of Article 230 in the Peace Treaty of Sèvres were obviously intended to cover, in conformity with the Allied note of 1915… This article constitutes, therefore, a precedent for Articles 6 c) and 5 c) of the Nuremberg and Tokyo Charters , and offers an example of one of the categories of 'crimes against humanity' as understood by these enactments. "

In a legal opinion of May 1951, on the question of possible reservations regarding the validity of the Genocide Convention, the International Court of Justice finally referred to the high humanitarian goals of this convention, which corresponded to the most elementary principles of morality , and stated that civilized states would regard these principles underlying the convention as binding anyway, which is why they would apply even without any obligation under the convention. Therefore, the Convention can legally be viewed as Ius Cogens , which means that it also applies to genocides that occurred prior to its entry into force.

Assessment by international institutions and organizations

UN Human Rights Commission

The 'Subcommittee on the Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities' of the UN Human Rights Commission named the events as genocide in a report on genocidal crimes published on August 29, 1985. In an addendum, it was noted that some members of the subcommittee objected to this because they considered the massacre of the Armenians to be inadequately documented and that certain evidence was falsified. With the acceptance of the report by this UN subcommittee , the genocide of the Armenians is nonetheless recognized by the UN.

European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP), through Decision of 18 June 1987 and 15 November 2001, the recognition of the genocide by the Turkish state today a prerequisite of EU accession of Turkey declared on 28 February 2002, in a further resolution Turkey reminded to comply with this requirement.

In 1987, the EP claimed to be the first major international organization to describe the events of 1915 as genocide.

On April 15, 2015, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Armenian genocide, the EP passed a resolution calling on Turkey to recognize the genocide as such and to continue its efforts, including granting access to the archives.

European Court of Human Rights

In December 2013, the European Court of Human Rights declared the decision of three Swiss courts that convicted Doğu Perinçek for denying the crimes against the Armenians to be unlawful . According to the court, unlike denial of the Holocaust, this should not be prosecuted because the term “genocide” is controversial in the case of the Armenians and Perinçek's condemnation therefore violates the fundamental right to freedom of expression. The Switzerland appealed against the verdict. The large chamber of the European Court of Human Rights confirmed the first-instance judgment on October 15, 2015, but emphasized that it was not associated with an assessment of the mass murders and deportations of the Armenians by the Ottoman Empire.

Permanent tribunal of the people

The Permanent People's Tribunal investigated the massacres of the Armenians during the First World War in 1984 and ruled that the extermination of the Armenian population through deportation and massacre constituted a genocide, and called on the United Nations and all member states to recognize the genocide of the Armenians . The verdict was pronounced by 13 representatives of the tribunal, who listened to reports from various legal experts as well as reports from historians and survivors of the genocide. The representatives, consisting of Nobel Prize winners and respected international scientists, also examined archival material.

The tribunal's independent examination board described the genocide of the Armenians as an "international crime" and ruled that the Young Turkish government is to blame for this genocide and the Turkish state take responsibility for it and the reality of the genocide and the damage it caused the Armenian people has suffered officially. The declaration by the Republic of Turkey, which was proclaimed in October 1923, that it did not yet exist at the time of the genocide, is considered by the tribunal to be null and void.

International Association of Genocide Scholars

In 1997 the International Association of Genocide Researchers unanimously passed a resolution classifying the massacre of over a million Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in 1915 as genocide and condemning the denial on the part of the Turkish Republic. In 2005, the organization wrote an open letter to Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, reaffirming that the Armenian genocide has been recognized by hundreds of independent genocide researchers. There is a reference to the lack of impartiality of researchers who advised the Turkish government and the Turkish parliament. In 2006, the organization wrote another open letter to those historians who follow the Turkish position of genocide denial, describing this stance as a blatant ignoring of overwhelming historical and scientific evidence and calling on the US Congress to do so a year later To officially recognize genocide. Between 1997 and 2007, the International Association of Genocide Researchers published four resolutions and declarations in which the genocide of the Armenians was recognized.

Turkish-Armenian Reconciliation Commission

In 2001 a Turkish-Armenian Reconciliation Commission was founded with the aim of promoting dialogue and understanding between Armenia and Turkey. The commission commissioned the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) to investigate the events of 1915. In 2003 the ICTJ came to the conclusion that the events of 1915 fulfilled all criminal offenses of the UN Genocide Convention .

Reviews outside of Armenia and Turkey

Since 1965, a number of states have officially recognized the deportations and massacres committed by the Ottoman state from 1915 to 1917 as genocide in accordance with the UN Genocide Convention of 1948 (including Argentina , Belgium , France , Greece , Italy , Canada , Lebanon , Luxembourg , the Netherlands , Austria , Russia , Sweden , Switzerland , Slovakia , Uruguay , the USA and Cyprus ).

Other states (such as Israel , Denmark , Georgia and Azerbaijan ) officially do not speak of genocide (as of 2008). In 2009, the Brown ( UK ) government condemned the crimes but did not label them as genocide under the UN Convention on Genocide.

Germany

In April 2005, the German Bundestag debated for the first time a resolution tabled by the CDU / CSU parliamentary group, according to which Turkey should be asked to acknowledge its historical responsibility for the massacre of Armenian Christians in the Ottoman Empire. The authors of the motion, who avoided the term “genocide” themselves, regretted “the inglorious role played by the German Reich, which in view of the wealth of information about the organized expulsion and extermination of Armenians did not even try to stop the atrocities.” In July of the same That year, the Bundestag unanimously passed a motion from all parliamentary groups, the reasoning of which referred to the more than one million victims and stated that numerous independent historians, parliaments and international organizations described the expulsion and extermination of the Armenians as genocide.

In a small question on February 10, 2010, the Left Party asked the Federal Government at the time to comment on whether it would consider the massacre of the Armenians in 1915/16 as genocide within the meaning of the 1948 UN Convention. The answer says: “The Federal Government welcomes all initiatives that serve to further process the historical events of 1915/16. An assessment of the results of this research should be left to scientists. The Federal Government is of the opinion that dealing with the tragic events of 1915/16 is primarily a matter for the two countries concerned, Turkey and Armenia. ”On June 4, 2010, the Federal Government replied to another small question that it saw no reason to to doubt the authenticity of the documents in the Political Archive and, overall, do not evaluate the available results of scientific research on the role of the German Empire. She mentioned that the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide does not apply retrospectively.

In the run-up to the Bundestag debate on the 100th anniversary of the start of the deportations, controversial discussions arose in the grand coalition about whether or not the genocide should be mentioned by name, as desired by the opposition parties. On April 14, 2015, the Scientific Services of the Bundestag presented a paper on the April 24th Remembrance Day.

On April 23, 2015, Federal President Joachim Gauck was the first Federal President to describe the Armenian massacre as genocide. According to Gauck, it is above all a matter of "recognizing, lamenting and mourning the planned annihilation of a people in all of its terrible reality". He warned against reducing the debate “to differences over a term”.

On April 24, 2015, the Bundestag discussed three motions (one joint from the Union and the SPD and one from the Greens and one from the Left ) on the genocide of the Armenians, in which this is referred to as such. The opposition parties also demanded a formal recognition according to the Genocide Convention of the United Nations , as well as a commitment to the historical responsibility of the German Reich. At the beginning of the debate, the President of the Bundestag Norbert Lammert said: "What happened in the middle of the First World War in the Ottoman Empire, under the eyes of the world, was genocide."