Weinviertel

Coordinates: 48 ° 30 ' N , 16 ° 20' E

| Districts and districts of Lower Austria |

|---|

|

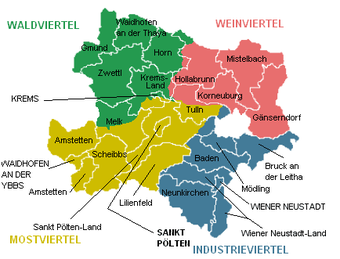

The Weinviertel , an ancient quarter under the Manhartsberg , is a region in the northeast of Lower Austria .

Since the political districts were formed in 1868, the districts in Lower Austria no longer have a legal basis and are purely landscape names. The older district division , which was still based on the old quarters, was replaced.

The name "Weinviertel" has been in use for about a century: The Weinviertel is Austria's largest wine-growing region . It largely corresponds to one of the main regions of the country ( main region Weinviertel or European region Weinviertel , as part of the Euregio Weinviertel-South Moravia-West Slovakia ). In the official statistics there is a group of districts ( NUTS: AT 125) with this name, but they only cover the northern part of the area.

overview

The borders of the Weinviertel run in the east along the state border from Austria to Slovakia , which is formed by the March . In the north, the Weinviertel borders the Czech Republic , where the Thaya essentially forms the border. The Manhartsberg , which lies east of the Kamp , represents the border to the Waldviertel in the west. In the south the Weinviertel borders on the Mostviertel and the industrial district , here the border is formed by the Danube . The Weinviertel covers an area of around 4,900 km².

The districts of Gänserndorf , Hollabrunn , Korneuburg and Mistelbach are counted as part of the Weinviertel . The judicial district of Kirchberg am Wagram of the Tulln district and small parts of the Horn and Krems districts of the Waldviertel (Manhartsberg area, Kremser Danube plains) are traditionally located in the Weinviertel region. Smaller mountainous western parts of the Hollabrunn and Tulln districts, however, are counted accordingly to the Waldviertel. Eggenburg is located at the transition between Waldviertel and Weinviertel.

Most populous cities and municipalities

Weinviertel municipalities with more than 5000 inhabitants:

| rank | City / market / municipality | Inhabitants January 1st, 2020 |

political district |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Stockerau | 16,875 | Korneuburg |

| 2. | Korneuburg | 13,331 | Korneuburg |

| 3. | Hollabrunn | 11,882 | Hollabrunn |

| 4th | Gänserndorf | 11,643 | Gänserndorf |

| 5. | Groß-Enzersdorf | 11,600 | Gänserndorf |

| 6th | Mistelbach | 11,583 | Mistelbach |

| 7th | Gerasdorf near Vienna | 11,401 | Korneuburg |

| 8th. | Strasshof on the northern line | 10,767 | Gänserndorf |

| 9. | Deutsch-Wagram | 8,960 | Gänserndorf |

| 10. | Langenzersdorf | 8,027 | Korneuburg |

| 11. | Wolkersdorf in the Weinviertel | 7,299 | Mistelbach |

| 12. | Laa an der Thaya | 6.241 | Mistelbach |

| 13. | Poysdorf | 5,483 | Mistelbach |

| 14th | Zistersdorf | 5,379 | Gänserndorf |

Administration and political structure

Historical administrative region

As part of the Teresian reforms was circular sub-Manhartsberg (abbreviated in the 18th and 19th centuries V. U. M. B. or UMB) established that as the lowest government unit to local landlords faced. Korneuburg was the seat of the district office . After the upheaval around 1848 and the transfer of rulers to free municipalities, district offices (see administrative district ) took over many areas of responsibility of the district offices. Such district offices were set up in 1853 for the districts of Feldsberg , Groß-Enzersdorf , Haugsdorf , Kirchberg am Wagram , Korneuburg , Laa , Marchegg , Matzen , Mistelbach , Hollabrunn , Ravelsbach , Retz , Stockerau , Wolkersdorf and Zistersdorf and the district office in Korneuburg now acted as the second Instance of the district offices and also acted as a supervisory authority. This administrative structure was in place until 1867. With the settlement in 1867 , the Weinviertel was divided into districts (or district authorities ) in the new constitution of Austria of 1867 , and thus the district of Unter-Manhartsberg was abolished.

However, the old district structure survived in the area of justice as the district court of Korneuburg , which was still the second instance for the district courts of the Weinviertel and the Weinviertel was also a separate constituency for the National Council until 1992, until a structure with smaller regional constituencies was established in the National Council electoral code of 1992 has been.

Main region

For spatial planning, Lower Austria is divided into five main regions . The Weinviertel is largely covered by the main Weinviertel region . The municipalities of the Tulln district to the left of the Danube, which belong to the central Lower Lower Austria region , and the municipalities of the Horn district east of Manhartsberg ( main region Waldviertel ) do not belong to this main region . In contrast, the area around Hardegg , which is part of the landscape of the Waldviertel, belongs to the main Weinviertel region.

Statistical region

As a group of districts , that is the NUTS 3 level of the official EU statistics for Austria, AT125 Weinviertel includes (as of 2015):

- Political District Hollabrunn (complete)

- Parts of the political district of Mistelbach (communities Altlichtenwarth, Asparn an der Zaya, Bernhardsthal, Drasenhofen, Falkenstein, Fallbach, Gaubitsch, Gaweinstal, Gnadendorf, Großharras, Großkrut, Hausbrunn, Herrnbaumgarten, Laa an der Thaya, Ladendorf, Mistelbach, Neudorf bei Staatz, Niederleis , Ottenthal, Poysdorf, Rabensburg, Schrattenberg, Staatz, Stronsdorf, Unterstinkenbrunn, Wildendürnbach, Wilfersdorf)

- Parts of the political district of Gänserndorf (communities Drösing, Dürnkrut, Hauskirchen, Hohenau an der March, Jedenspeigen, Neusiedl an der Zaya, Palterndorf-Dobermannsdorf, Ringelsdorf-Niederabsdorf, Sulz im Weinviertel, Zistersdorf)

The political district of Korneuburg belongs to Vienna's surrounding area / northern part (AT126). As such, the statistical region corresponds to the northern part of the traditional Weinviertel.

The structure goes back to the court districts of Laa an der Thaya and Zistersdorf , which were closed in 2013 , as Lower Austria is divided into seven sub-regions and the groups of districts comprised partly political and partly judicial districts, and will now continue to be statically comparable.

Geography and nature

Division into sub-areas

According to the nature conservation concept of 2015, Lower Austria is divided into 124 sub-areas (this division was developed in the 1990s), which are grouped into 26 regions. The decisive factor are the boundaries of the main regions, so that the division is not purely natural, but is also based on the administrative structure.

Orography and geology

The landscape of the river plains of the Thaya, March and Danube frame the Weinviertel in the north, east and south. In the west, the Manhartsberg forms the transition to the gneiss and granite highlands . The highest point is the Buschberg at 491 m. Other important bodies of water in the Weinviertel are Göllersbach , Hamelbach , Pulkau , Rußbach , Schmida , Weidenbach and Zaya .

Inside, the Weinviertel is separated into an eastern and a western part by the Waschbergzone ( Rohrwald , Leiser Berge , Staatzer Klippe and Falkensteiner Berge), the Molasse zone with gentle hills and wide hollow valleys in the west and the northern Vienna Basin and the Marchfeld in the east.

Waters

Sometimes due to the low rainfall there are relatively few wetlands in the Weinviertel these days and the landscape is considered to be extremely dry. This was not always the case, however: while elevations used to be home to dry and warm biotopes, once extensive wetlands with reeds and reed beds extended in the lowlands along Pulkau , Thaya , Zaya , Schmida , Göllersbach , Weidenbach , Stempfelbach , Rußbach and other streams .

From the late Middle Ages onwards, humans created additional bodies of water or enlarged existing wetlands by building fish ponds and building mills and weir systems. The first fish ponds were created at the end of the 14th century, the majority in the 15th and 16th centuries. The pond area in the Weinviertel exceeded that during the heyday of fish farming in the 17th century. those in the Waldviertel . In the middle of the 18th century, the Weinviertel still had a share of 64% in fish farming in the country, whereas the Waldviertel only 31.5%. The water power was used extensively by mills, at the Zaya there were once almost 50 of them, one every 1.2 km on average. At the time of the Bohemian War the pond economy collapsed and afterwards it could never reach the level it had before. The operation of ponds was no longer as lucrative as it used to be, so they were gradually drained. Larger systems exist today only in Bernhardsthal , Katzelsdorf and Nexing .

In the Waldviertel, however, this was not advantageous due to the poor soil conditions, which is why many ponds have been preserved there to this day. From the end of the 18th century, water bodies began to be straightened and lowered. The streams and rivers have been degraded to drainage ditches, the task of which is to divert the water as quickly as possible. On the one hand, this should protect the settlements against floods and, above all, enable more intensive agricultural use of the river area. In the past, wet meadows were grazed with draft animals such as horses and oxen, but with the increasing mechanization of agriculture, agricultural use was sought. These human actions have since drastically reduced the number of wetlands. After some large landowners had already started doing this in the 18th century, large areas - around 14,000 hectares - were drained especially in the 19th and 20th centuries with financial support from the state in order to be able to increase agricultural productivity. In order to enable the use of ever larger agricultural implements, small structures such as creeks, terraces, arable steps, green areas and field trees were removed, thus reducing water retention and promoting soil erosion when it rains. Existing drinking troughs, alluvial pools and ponds for ice production were also largely removed, the water table was significantly lowered and the Weinviertel turned into a largely dry stretch of land. Valuable habitats were destroyed, as a result of which many plant and animal species lost their livelihood.

In addition to the Danube and Marchauen there are today in the Weinviertel only in Pulkautal and the Thayatal larger swamps. Since wetlands and tributaries serve as receiving waters during floods and dampen the flood peaks in the places downstream, the measures have increased the risk of flooding in many places. From the end of the 20th century, attempts were therefore made - again with financial support from the state - to improve the ecological and flood situation by building retention areas , widening bodies of water, creating small bodies of water and increasing the structural diversity in river beds and bank areas.

climate

The Weinviertel belongs to the relatively dry Pannonian climatic area with cold winters and hot summers. The annual mean temperature in Retz is 10.3 ° C and in Poysdorf 10.4 ° C. The mean annual sums of precipitation are only between 500 and 600 millimeters. The duration of the snow cover in Retz is around 30 days and there are around 81 frost days , in Poysdorf, on the other hand, the duration of the snow cover is around 25 days and there are around 87 frost days. The duration of sunshine in Retz is around 1900 hours and in Poysdorf around 2000 hours.

|

Climate table for Oberleis (420 m)

Source:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hours of sunshine in Poysdorf (209 m)

Source:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

fauna and Flora

From a floristic point of view, the Weinviertel is part of the Pannonian Floral Province , part of the South Siberian-Pontic-Pannonian Floral Region , which is why the vegetation differs greatly from the more western parts of Austria and is accordingly unique and worthy of protection. In addition to specifically Pannonian species (e.g. forest-steppe wormwood on the Bisamberg ), there are also those that have their main distribution area much further east and here - partly as relics of the cold ages - reach their western limit of distribution (e.g. Tátorján sea kale in Ottenthal ). In addition, a clear sub-Mediterranean influence can be seen, as dry and warm summers are characteristic there too and sub-Mediterranean species such as downy oak and diptame therefore also thrive in the Pannonian region. Without human influence, the area would presumably be forested, but has been kept forest-free through clearing and centuries of use (agriculture, grazing). Extensive grazing by livestock resulted in large secondary steppes , which were largely destroyed after the intensification and mechanization of agriculture in the second half of the 20th century and have only survived in rudimentary form. In addition to the dry and warm climate, the soil conditions also shape the vegetation: large parts of the Weinviertel are covered with loess , a sediment that was transported and deposited by the wind during the cold periods. Along the Waschberg zone, the limestone is characteristic, which created substrate steppes over the shallow ground. In the Marchfeld there is a specific sand vegetation (e.g. sand mountains near Oberweiden ) over sands deposited during the last Ice Age and the Post Ice Age, which were blown out of the rivers, especially the Danube . At Zwingendorf and Baumgarten an der March there are small areas of interesting salt locations, above correspondingly salty soils.

The fauna in the Weinviertel also differs from that in the more western parts of the country. In the Weinviertel, for example, the northern white-breasted hedgehog (Ostigel) occurs exclusively , which reaches its limit of distribution around 200 kilometers to the west and there, after an area of overlap, is replaced by the brown-breasted hedgehog (western urchin).

history

Prehistory and early history

Compared to many other Austrian landscapes, the Weinviertel has a dense prehistoric and early historical settlement. The reasons for this are the favorable climatic conditions and the nature of the soils (mainly brown earth and steppe black earth soils). This land between the Thaya and the Danube lies at the intersection of the Amber Road and the Danube Path and has therefore - in contrast to remote areas - has always had easier access to cultural events. The earliest human traces date from the last glacial period and therefore belong to the Paleolithic (Aurignacia and Gravettia). Since the sites of this time are mostly under mighty loess packages , the discovery is left to chance. Important stations have become known from Großweikersdorf and Stillfried , among others .

From the end of the Paleolithic and for the transition to rural management of the Neolithic, there are so far unambiguous legacies only from Ebendorf near Mistelbach and from Bisamberg . In contrast, the Neolithic is from around 5000 BC. Chr. Represented with an almost unmistakable number of settlement places. Even the oldest linear ceramics can refer to numerous settlements, for example in Grafensulz . This is followed by the note head ceramics , the rare stitch band ceramics (Grafensulz, Großmugl ), the Moravian painted ceramics ( Wetzleinsdorf ) and several small groups from the end of the Neolithic, such as the bell beaker culture ( Laa / Thaya ).

The painted ceramic culture has become widely known primarily through numerous evidence of idols (anthropomorphic and zoomorphic idols ) and the monumental circular moats . The around 2000 BC The Bronze Age that started in BC is represented with all sections. The early Aunjetitz and Veterov culture is known in its classic form. There were significant settlements at Großmugl and Zellerndorf , for example . The Middle Bronze Age is mainly known from ceramic depot finds , such as the eponymous corn pear tree . Barrows from the Middle Bronze Age (approx. 1600 BC) were found near Gaweinstal .

The late Bronze Age ( urn field culture ) is represented in the early phase by the important grave finds from Baierdorf and Pleißing and the ceramic depot from Großmeiseldorf . For the later phase, it is sufficient to refer to the important eponymous fortification of Stillfried ( Stillfried type), from whose area extensive settlement and grave inventories of this cultural level have become known. The around 750 BC The early Iron Age ( Hallstatt culture ), which began in the early 3rd century BC, is best known in the Weinviertel through the numerous "princely" barrows (e.g. Großmugl , Niederhollabrunn ). The late Iron Age ( Latène Age ) is well represented by the important grave finds from Leopoldau , Bernhardsthal and Laa / Thaya. In Ladendorf an important settlement is detected (with Eisenverhüttungsanlagen) of the late period. A central position is to be assumed for the hillside settlement of Oberleis due to the rich jewelry and coin inventory. The earliest mint north of the Danube was documented for the supra-regionally important settlement in Roseldorf , municipality of Sitzendorf .

The arrival of Germanic peoples in the course of the first century AD brought about a far-reaching change in the cultural image of northern Lower Austria. The marcomanni and quadrupeds now settling here seem to have lived in peaceful coexistence and togetherness with the down-to-earth “Celtic” population, although the Celtic peculiarity is gradually becoming only slightly noticeable. In older research (until around 1960) it was assumed that there were also Illyrian peoples in Austria in addition to the native Celtic population. However, this has been refuted according to the latest research, with the result that no settlement activity by Illyrians could ever be established in the area of today's Austria.

The occupation of the area north of the Danube brought the Teutons into direct contact with the Roman Empire, to which the rest of today's Austria belonged since Emperor Augustus. For four centuries, warlike and peaceful events between these two powers determined cultural events. The earliest Germanic finds (1st century) are known from Baumgarten an der March , Mannersdorf an der March , Gaweinstal and Mistelbach , to name but a few.

The Germanic settlements of the 2nd and 3rd centuries can be found scattered all over the Weinviertel. Especially in the March and Thaya areas there was a very dense settlement activity along the rivers. In the 4th century in particular, disk-turned ceramics appeared as an innovation, sometimes with typical wave decoration. The dovetailing with Roman culture in the first four centuries is perhaps most evident in the Roman systems of Stillfried , Oberleis and Niederleis , Grafensulz and Michelstetten .

The time of the Great Migration, the 5th and 6th centuries, is known almost exclusively from graves. The rich burials of Untersiebenbrunn and Laa / Thaya , which are attributed to a Gothic upper class, should be mentioned. Towards the end of the 5th century, another Germanic tribe, the Longobards , came to Lower Austria. The graves of Aspersdorf , Hollabrunn and Poysdorf are mentioned for the Weinviertel . The withdrawal of the Lombards to Pannonia in the middle of the 6th century made the settlement area free for new populations. A small cemetery from Mistelbach and individual finds (Oberleis) are attributed to the Avars . Early Slavs are also suspected due to fewer finds.

From the end of the 8th century, settlements and grave finds are known, which are mainly attributed to a western Slavic peasant population because of typical ceramic products. Magyar influences are also suspected. A remnant of Staatz -Kautendorf and place names ( Ungerndorf , Schoderlee, Fallbach and Gaubitsch ) point in this direction.

middle Ages

At the end of the Migration Period , the Lombards , among others, settled in the Weinviertel before they founded an empire in northern Italy . According to this, the sources are sparse, but the Weinviertel is likely to have been under the influence of the emerging Great Moravian Empire , and Slavic settlements can be assumed to be safe. Finds also indicate Avar settlements. From the 8th century, the Franconian colonization from the west by the Bavarians began. Under Charlemagne , the Avars were defeated in the Pannonian Plain and thus set a further impetus for the Frankish settlement. In the subsequent decline of the Carolingian Empire , the Weinviertel was probably exposed to changing influences from Bavaria, Slavs and Hungary until, after the battle on the Lechfeld in 955 and the defeat of the Hungarians, the influence of the newly formed Holy Roman Empire prevailed in the long term . In the Kamptal ( Gars am Kamp ) there was a Slavic principality under Franconian sovereignty from the beginning of the 9th century to around the middle of the 10th century, until it was probably destroyed by the Hungarians.

With the enfeoffment of the Franconian Babenbergs from around 976 as margraves for the Mark on the Danube, a steady development of the Danube area and subsequently also of the adjacent areas began.

From the turn of the millennium it can be assumed that the Weinviertel will be settled and reclaimed across the board. From this time onwards, a functioning administrative apparatus provides documents as sources. The Weinviertel suffered again and again from wars and organized raids by Hungarians and especially by Czechs from the north. In the battle of Mailberg an Austrian army suffered a defeat against a vastly superior Czech army.

The Crusades had a remarkable impact on the Weinviertel: On the return trip to England, King Richard the Lionheart was captured by the Babenberg Duke Leopold V and released for a ransom . With the proceeds, Duke Leopold fortified the northern border of his duchy and built fortifications in Drosendorf , Laa an der Thaya, etc. After that, the threat from the north apparently decreased.

After the Babenbergs died out, Austria became a bone of contention for the European dynasties. Matthias Corvinus , King of Hungary , and before that, Ottokar II. Přemysl , King of Bohemia , each attempted to win the country for themselves by marrying a Babenberg woman and granting them privileges. Ultimately, Přemysl Ottokar II of Bohemia was able to prevail. However, this was defeated by the German King Rudolf von Habsburg in the Battle of Dürnkrut in 1278. In 1282 the sons of Rudolf von Habsburg Albrecht I and Rudolf II were enfeoffed with the entire hand of the Duchy of Austria. This also brought the Weinviertel under the rule of the Habsburgs .

Under the Habsburgs, the Weinviertel did not necessarily become more peaceful; the overpowering Luxembourgers in Bohemia and Moravia set the political line. The Hussite Wars also took place in the Weinviertel, among other places. Only when the legacy of the Luxembourgers passed to the Habsburgs through persistence and marriage contracts did the Weinviertel become a heartland of the developing Habsburg possession. Under Emperor Maximilian I , Hungary was also added.

Modern times

The Weinviertel was also affected by the first Turkish siege of Vienna in 1529 . The area around Vienna was hit hard by the Akıncı , a 20,000-strong cavalry troop serving the Ottomans . A drastic population decrease in the Weinviertel was the result.

The Counter-Reformation did not begin in the country, which had become largely Protestant during the Reformation , until the 1570s. A peasant uprising was bloodily suppressed in 1597. The Thirty Years' War seemed to have little to touch the wine district for a long time, only at the beginning of this long war, when Count Heinrich Matthias von Thurn with the army of the rebel Bohemia was advancing on Vienna, some places along today was Brünnerstraße looted. Towards the end of the war, however, things got far worse: the last great battle of the Thirty Years' War took place near Jankau in Bohemia, about 60 km southeast of Prague .

On March 6, 1645, a defeated Swedish -protestantisches army under Field Marshal Lennart Torstensson the Imperial - Habsburg forces under Field Marshal Melchior Count of Hatzfeld , which was open for the Swedes the way to Vienna. The Swedish troops devastated the Weinviertel, and several castles such as Staatz and Falkenstein have been in ruins since then . The Gaunersdorf market , today's Gaweinstal , was completely burned down, but Mistelbach was also badly hit.

Even in 1683 after the unsuccessful Second Turkish Siege of Vienna , there was severe devastation in the Weinviertel. Again large parts of the Weinviertel population perished or were abducted.

19th century

During the Napoleonic Wars , the Battle of Hollabrunn and Schöngrabern between the French and the Russian-Austrian troops took place on November 16, 1805 . In the spring of 1809 Austrian, Russian and French troops again crossed the Weinviertel. The political upheavals of 1848 also resulted in the abolition of the aristocratic lords in the Weinviertel .

Jewish Weinviertel

After 1848, flourishing Jewish communities developed in the Weinviertel. There were religious communities in Gänserndorf , Mistelbach and Hollabrunn , and prayer houses and cemeteries were set up in numerous places. Jewish life in the Weinviertel came to an almost complete standstill in 1938.

20th century

At the end of the First World War and with the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy , the Weinviertel became a border area again, lacking the larger and more important part of the hinterland. After Austria was annexed to the German Reich in March 1938 , the Weinviertel became a part of the "Niederdonau" district . In the last days of the Second World War , the bitterest fighting took place on Austrian soil in the eastern Weinviertel. One of the reasons for this was that the last still functioning oil fields of the Third Reich were in Zistersdorf and its surroundings . This made this area one of the primary targets of the Red Army when it crossed the March to the west on April 6, 1945 . The area was vigorously defended by the Wehrmacht and the Waffen-SS , but was overrun by the Russians in April .

After the end of the Second World War, the Weinviertel was in the Soviet occupation zone , and the population also had to endure the reprisals of the Red Army. In 1955 the occupation troops withdrew again. The northern Weinviertel in particular has benefited from the turnaround in Eastern Europe since 1989 and the opening of the border; since 2003 the Weinviertel has been located in the middle of the Centrope European region .

Economy and Infrastructure

In addition to viticulture and the agricultural industry, other sectors also contribute to the Weinviertel's economy: the food industry, building materials industry, as well as chemistry and the extraction of crude oil and natural gas by OMV in the east of the Weinviertel in the so-called oil communities of Neusiedl an der Zaya , Zistersdorf , Matzen , Auersthal and Prottes . Due to its proximity to Vienna , excursion traffic also plays a role in the Weinviertel's economy.

Viticulture

Due to the Pannonian climate and the loess soils , the Weinviertel is particularly suitable for viticulture. With around 15,800 hectares, the Weinviertel is the largest wine-growing region in Austria. Well-known wine towns are Röschitz , Retz , Haugsdorf , Falkenstein , Poysdorf , Herrnbaumgarten , Wolkersdorf and Mannersdorf / March. The wine-growing areas and places are grouped under the 400 km long "Weinviertel Wine Route". Around the wine town of Retz - with the Retz adventure cellar and the windmill known as a tourist destination - red wines have always thrived . The dry, low-precipitation climate favors red wine production.

The following grape varieties are mainly grown:

- Grüner Veltliner - the leading grape variety in the Weinviertel

- Pinot Blanc

- Welschriesling

- Zweigelt

- Blue Portuguese

The Weinviertel DAC has existed since 2003 . It stands for “Grüner Veltliner” with a peppery taste that is typical of the region.

Typical wine events

The Weinviertel is historically shaped by wine. Therefore, there have been and are many initiatives that promote wine culture and are known across the country. The most important events related to wine are:

- Weinviertel wine tour: at the start of the season, 200 winemakers on the Weinviertel wine route open their doors. Above all, the bottles of the new vintage will be tasted.

- Going to the Grean: an old Lower Austrian custom. As a thank you, the winemakers took their reading helpers out into the countryside on Easter Monday to taste the new wine together. Today all guests are invited, the cellar lanes and wine cellars will be opened for the first time after winter.

- Dining in the Weinviertel: popular outdoor events in the open air, in the middle of vineyards, in cellar lanes or at special locations. Long tables are covered in white, 5-course menus are served and local bottlings are served.

- Wine autumn in the Weinviertel: is typical of the Weinviertel. The high season in the Weinviertel starts with the grape harvest (late August / early September). Every cellar lane and every wine village celebrates the grape harvest, there is a fresh storm and local products to buy and taste.

Agriculture

In addition to viticulture, there is also extensive agriculture. Vegetables have been grown in Marchfeld for generations and are therefore a supplier to the nearby capital Vienna. Grain and potato cultivation are also traditional foods. Pig breeding is of great importance in animal breeding .

In the last decades of the 20th century, apricots were also grown , so that the Weinviertel has become one of the largest growing areas in Austria. Around Poysdorf alone, 350 hectares are cultivated with this type of fruit.

Interlinked with tourism, efforts are being made to promote and market traditional foods in their respective regions under the umbrella brand Genussregion Österreich . This includes:

- Laaer onion region

- Marchfeld region vegetables

- Marchfeld asparagus region PGI

- Retz pumpkin region

- Weinviertel potatoes region

- Weinviertel grain region

- Weinviertel pig region

- Weinviertel Wildlife region

See also: List of enjoyment regions in Austria

Public transport

The Weinviertel is part of the Verkehrsverbund Ost-Region (VOR) and is integrated into public transport by the Vienna S-Bahn and numerous bus connections.

The most important rail connections in the Weinviertel (starting from Vienna ):

- Northern line via Gänserndorf - Bernhardsthal - and on towards Břeclav (Czech Republic)

- Nordwestbahn via Korneuburg - Stockerau - Hollabrunn - Retz - and on towards Znojmo (Czech Republic)

- Laaer Ostbahn via Gerasdorf - Wolkersdorf - Mistelbach - Laa an der Thaya

- Franz-Josefs-Bahn in the area Absdorf-Hippersdorf - Ziersdorf - and further towards Gmünd and České Velenice (Czech Republic)

- Marchegger Ostbahn via Marchegg and on towards Bratislava (Slovakia)

In addition to these main lines, there are also numerous branch lines in the Weinviertel .

Road traffic

Due to the immediate proximity to Vienna and the resulting and growing suburbs , there is a high volume of traffic, which was further increased by the opening of the borders. Large-scale transport projects are attempting to take this development into account.

- The Vienna outer ring expressway S 1 connects the Danube bank motorway A 22 from Korneuburg with the north motorway A 5 near Eibesbrunn and finally with the Vienna north edge expressway S 2 in Vienna-Süßenbrunn. In the final stage, it will cross the Danube at Groß-Enzersdorf and establish a connection to the east A4 motorway at the Schwechat junction .

- The north A 5 motorway runs from the Eibesbrunn junction north to Gaweinstal and, when completed, will lead to the Czech border near Drasenhofen.

- The Weinviertel expressway S 3 leads from Stockerau to Hollabrunn and, in the final stage, is to continue following the course of the current Weinviertler Straße B 303 towards the Czech border near Kleinhaugsdorf.

- The planned Marchfeld expressway S 8 is to lead from the Deutsch-Wagram junction via Marchegg in the direction of Bratislava.

Culture

Events

The Weinviertel Festival , the Summer Games in Stockerau and the performances in the Westliches Weinviertel Theater (TWW) also contribute to cultural life, as does the annual Filmhof Festival in Asparn an der Zaya , the Musical Festival in Staatz and the Puppet Theater Days in Mistelbach . Several classical music festivals take place in the region: Con Anima in Ernstbrunn , culture in Schloss Kirchstetten near Neudorf and the Gottfried von Eine days in Oberdürnbach (municipality of Maissau ). With 50,000 to 60,000 visitors in just two days, the pumpkin festival in the Retzer Land is one of the largest events in the Weinviertel, as is the knight's festival in Dürnkrut and Jedenspeigen , which takes place alternately every year and is attended by 20,000 people on the two days. The largest wine festival is the Poysdorf wine festival with 30,000 visitors.

Art in public space

Numerous art projects in public space were realized in the Weinviertel. Land Art in particular has emerged in recent years, such as the Hetzmannsdorf art field , the Paasdorf cultural landscape , the hand with grapes in Wetzelsdorf and numerous other projects.

Museums

Important museums are the MAMUZ Prehistory Museum (formerly the Asparner Museum for Prehistory ) and the Niedersulz Museum Village , the Nonseum in Herrnbaumgarten and the Liechtenstein Museum in Wilfersdorf. Some museums and cultural initiatives in the eastern part of the Weinviertel have joined forces in the Bernsteinstrasse Association. The Mistelbach Museum Center was opened in 2007 in Mistelbach , and is primarily dedicated to Hermann Nitsch . In 2014 the Vino Versum Poysdorf opens , an adventure museum on the history of viticulture and wine trade.

Architectural monuments

Castles

The ruins of the Falkenstein and Staatz castles on high limestone cliffs were considered impregnable fortresses until they were captured by the Swedes in the Thirty Years' War. At that time, Kreuzenstein Castle was also destroyed, but rebuilt in the 19th century.

A special feature is the Palterndorf defense tower , the only medieval tower of its kind north of the Danube. Buildings from the transition period from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance are the castles Asparn and Jedenspeigen .

Castles

There is a castle in almost every place, most of them go back to medieval fortresses and were repeatedly destroyed and rebuilt, especially in the baroque period such as Schloss Kirchstetten and Schloss Wilfersdorf . Particularly noteworthy are Schönborn Castle ( Johann Lucas von Hildebrandt ), Schmida Castle ( Jakob Prandtauer ), the Marchfeld castles Niederweiden Castle and Hof Castle or Thürnthal Castle .

In the period of classicism and romanticism, interior fittings such as those at Loosdorf Castle or gardens such as the Heldenberg emerged .

Cellar lanes

In Lower Austria there are 1107 cellar lanes with 36,857 buildings in 181 communities, three quarters of them in the Weinviertel. Well-known cellar lanes are, for example, the Öhlbergkellergasse in Pillersdorf , the Zipf in Mailberg , where 21 adjacent press houses are listed, and the Gstetten in Poysdorf . The longest cellar lane in the world is the one in Hadres with a length of 1,600 meters and 400 cellars and press houses. Kellergassen in Pulkautal also served as a venue in the Polt novels of Alfred Komarek .

Small monuments

The Weinviertel is rich in small monuments such as wayside shrines , columns of light, tabernacle pillars , statues of saints, groups of calvaries and pillories that can be found practically in every place and densely distributed in the landscape and have a significant impact on the image of the region. Many of these buildings date from the Gothic period , but most from the Baroque period , are mostly made of ( Zogelsdorfer ) stone and are often of remarkable quality.

Sports

The so-called Weinviertel Raiffeisen Running Cup , a series of up to seventeen regional running competitions , has been held annually since 1989, mainly in the Gänserndorf and Mistelbach districts . In 2013 this will take place in 14 municipalities. The evaluation of the competition is a point system in which women and men are evaluated separately; the respective winners receive 100 points, those placed behind receive their points in proportion to the winning time. The best eight runs of each season are included in the overall standings.

Personalities

The list of important Weinviertel residents presents past and present personalities who were born in the Weinviertel or who live here or who are particularly connected to this region.

literature

- Brochure Main Region Strategy 2024 - Weinviertel. NÖ.Regional.GmbH , 2015 (pdf).

- Eva Rossmann , Manfred Buchinger: Off to the Weinviertel. Folio Verlag, Vienna / Bozen 2012, ISBN 978-3-85256-569-9 .

- Mella Waldstein , Manfred Horvath : The Weinviertel. More than idyll. Verlag Bibliothek der Provinz , Weitra 2013, ISBN 978-3-99028-200-7 (Yearbook Volkskultur Niederösterreich, 2013).

various more special:

- Franz Stojaspal: Introduction to the geology of the Weinviertel. In: Mannus. 32, Bonn 1989, pp. 3-25.

- Hermann Maurer : Introduction to the prehistory and early history of the Lower Austrian Weinviertel. In: Mannus. 32, Bonn 1989, pp. 26-76.

- Antonín Bartoněk, Bohuslav Benes, Wolfgang Müller-Funk: cultural guide Waldviertel, Weinviertel, South Moravia. Deuticke, Vienna 1993, ISBN 3-216-30043-9 .

- Evelyn Benesch, Bernd Euler-Rolle , Claudia Haas, Renate Holzschuh-Hofer, Wolfgang Huber, Katharina Packpfeifer, Eva Maria Vancsa-Tironiek, Wolfgang Vogg: Lower Austria north of the Danube (= Dehio-Handbuch . Die Kunstdenkmäler Österreichs ). Anton Schroll & Co, Vienna et al. 1990, ISBN 3-7031-0652-2 .

- Alfred Komarek : Dives in the green sea. Kremayr & Scheriau, Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-218-00641-4 .

- Franz K. Obendorfer, Franz Obendorfer: The other Weinviertel. Self-published, Mistelbach 2010, ISBN 978-3-200-01807-5 .

- Norbert Sinn: The operational significance of the Weinviertel area. In: Stefan Bader, Mathias Hirsch u. a. (Ed.): The Mistelbach garrison. The story of a barracks and its surroundings. Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-902551-33-7 .

Further information

media

- Weinviertel - wide country. Documentary, Austria, 2009, 44:20 min., Book: Robert Neumüller, director: Alfred Vendl, moderation: Alfred Komarek , production: AV Documenta, ORF , BMUKK , series: Universum - Wundersame Österreich, first broadcast: November 12, 2009 at ORF 2 , table of contents from 3sat and from ORF .

Web links

- weinviertel.at

- weinviertel.net

- bernsteinstrasse.net

- weinstrasse-weinviertel.at

- Niederösterreich.at / weinviertel

Individual evidence

- ↑ Breakdown of Austria into NUTS units. Territorial status 01/01/2015 (PDF, statistik.at).

- ↑ Lower Austria nature conservation concept

- ↑ Heinz Wiesbauer, Manuel Denner: Wetlands - natural and cultural history of the Weinviertel waters. Vienna 2013 (published by the Federal Ministry for Agriculture, Forestry, Environment and Water Management and the Office of the Lower Austrian Provincial Government, Department of Water Engineering).

- ↑ a b climadata_oesterreich_1971

- ^ Manfred A. Fischer , Karl Oswald, Wolfgang Adler: Excursion flora for Austria, Liechtenstein and South Tyrol. 3rd, improved edition. Province of Upper Austria, Biology Center of the Upper Austrian State Museums, Linz 2008, ISBN 978-3-85474-187-9 , pp. 120 f., 127.

- ↑ Luise Schratt-Ehrendorfer: The flora of the steppes of Lower Austria: flora and vegetation, site diversity and endangerment. In: Heinz Wiesbauer (Ed.): The steppe is alive - rocky steppes and dry grasslands in Lower Austria . St. Pölten 2008, ISBN 978-3-901542-28-2 .

- ↑ Manfred A. Fischer: A touch of the Orient - Pannonian vegetation and flora. In: Nature in the heart of Central Europe. 2002, ISBN 3-85214-776-X .

- ^ Friederike Spitzenberger: The mammals of Lower Austria. In: Nature in the heart of Central Europe. 2002, ISBN 3-85214-776-X .

- ↑ Bundesdenkmalamt (Ed.): Trassenarchäologie. New streets in the Weinviertel . Vienna 2006, pp. 20–23, 26–31.

- ^ Walter F. Kalina: Ferdinand III. and the fine arts. A contribution to the cultural history of the 17th century . Dissertation, University of Vienna 2003, p. 16.

- ↑ Christa Jakob: A journey through time through the history of the city of Mistelbach. In: Stefan Bader, Mathias Hirsch u. a. (Ed.): The Mistelbach garrison. The story of a barracks and its surroundings . Vienna 2012, p. 21 f.

- ↑ Jewish Weinviertel - map overview. Retrieved November 14, 2019 .

- ^ Hans Egger, Franz Jordan: Fires on the Danube. The finale of the Second World War in Vienna, Lower Austria and Northern Burgenland . Graz 2004, pp. 264-279, pp. 332 f., P. 415.

- ↑ Wine from the Weinviertel - Wine. Retrieved November 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Grüner Veltliner - Wine. Retrieved November 14, 2019 .

- ^ Weinviertel DAC - Wine from the Weinviertel. Retrieved November 14, 2019 .

- ^ Events in the Weinviertel. Retrieved November 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Weinviertel wine tour. Retrieved November 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Go to the Grean. Spring offers in the Weinviertel. Retrieved November 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Dining in the Weinviertel - Culinary. Retrieved November 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Wine autumn in the Weinviertel - wine and themed festivals. Retrieved November 14, 2019 .

- ↑ More apricots than in the Wachau in Lower Austria from June 26, 2017, accessed on July 12, 2019.

- ↑ Theater, music and stage - culture and art. Retrieved November 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Museums in the Weinviertel - museums and galleries. Retrieved November 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Cellar alleys - wine. Retrieved November 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Regulations . Weinviertel Raiffeisen Laufcup , accessed on June 3, 2013.