Linear ceramic culture

The linear ceramic band culture , also known as linear ceramic band culture or ceramic band culture , technical abbreviation LBK , is the oldest rural culture of the Neolithic Age in Central Europe with permanent settlements. The introduction of this culture , also known as Neolithic, subjected the pre-existing cultures to extensive changes; this is accordingly referred to as the Neolithic , the epoch that began with the LBK as the Early Neolithic . In 1883, the historian Friedrich Klopfleisch introduced the term "ribbon ceramics" into the scientific discussion, derived from the characteristic decoration of the ceramic vessels, which have a ribbon pattern of angular, spiral or wave-shaped lines.

With the appearance of the linear ceramic culture, there were a number of technical, instrumental and economic innovations, such as ceramic production, improved tool and work equipment production, sedentarism, agriculture, cattle breeding, house and well construction and the construction of trenches. It was a period of economic change from an appropriating, extractive economy to a food-producing economy , which went hand in hand with the emergence of immobile property and storage for the group members.

In Anglo-Saxon literature, linear ceramics are referred to as linear pottery culture or linear band ware, linear ware, linear ceramics or as incised ware culture .

Spread of the band ceramists

The spread of the Linear Band Ceramic Culture (LBK) probably began around 5700 BC. BC - starting from the area around Lake Neusiedl - and created a large, culturally uniform and stable settlement and cultural area within a period of human history of around 200 years . The reconstruction of this cultural unity is based on finds in the areas of today's countries West Hungary ( Transdanubia ), Romania , Ukraine , Austria , South West Slovakia , Moravia , Bohemia , Poland , Germany and France (here under the name culture rubanée: Paris Basin , Alsace and Lorraine ) . Accordingly, the LBK is considered the largest area culture of the Neolithic .

A possible division of the LBK into epochs in the sense of an absolute chronology is:

- around 5700/5500 to around 5300: oldest LBK;

- around 5300 to 5200: average LBK;

- around 5200 to 5000: younger LBK;

- around 5100 to 4900: youngest LBK (overlaps with younger LBK).

With the end of the LBK, the transition from the Early Neolithic to the Middle Neolithic is set in a synthetic chronology for Central Europe . The Alföld linear ceramics (Eastern ribbon ceramics in Hungary: 5500-4900 BC), in the broadest sense also the stitch ribbon ceramics in Central Europe (4900-4500 BC ), are also counted among the ribbon ceramics or ribbon ceramics in a broader sense .

The band ceramists are probably closely related to the Körös-Criș culture (in short: Körös culture ), which dates back to the period from 6200 to 5600 BC. Is dated. In the Danube region, it is considered to be one of the most important cultures of the early Neolithic and is regarded as an eastern precursor culture of the LBK (compare Pișcolt culture ).

The Starčevo culture is also seen as a precursor culture . The Hungarian prehistorian Eszter Bánffy wants to derive the LBK solely from the Starčevo culture. Paleogenetic analyzes carried out in 2014 by a group led by the German anthropologist Kurt W. Alt support this hypothesis.

Two models are primarily discussed for the process of Neolithization:

- cultural diffusion: Appropriation of cultural techniques ( culture transfer , acculturation ) by the local late Mesolithic population (compare diffusionism and cultural diffusion ) - the Neolithic developed out of the local Mesolithic population and knowledge of agriculture, cattle breeding and the associated technologies came from the Middle East from from one indigenous group to the next without any fundamental migration of human groups

- demic diffusion: immigration of groups from the Middle East - the bearers of the band ceramic culture were not members of or descendants of the post-glacial , Mesolithic indigenous hunters and gatherers ; the spread of the Neolithic (Neolithic) was based on population growth with spatial expansion of agricultural communities or entire societies.

Integrative models exist between the two extremes, representing a certain degree of mixture of indigenous Mesolithic and immigrant Neolithic population groups. This could have been caused by dominant elites, infiltration, leapfrog colonization, or flexible borders.

Based on DNA analysis after the turn of the millennium, the immigration theory is preferred. Whether increasing population density and the scarcity of resources, among other factors, were the sole motives for immigration cannot be determined with evidence.

Origin of band ceramics

The ribbon ceramics reached the northern loess borders in Central Europe from 5600 to 5500 BC. According to some common doctrines, it emerged from the Starčevo - Körös cultural complex. This is how the earliest ceramic ribbon settlements in Transdanubia that have been excavated in recent years are interpreted. The vessels of the oldest band ceramics are characterized by their flat bottom and organic aging , they are very similar to the late Hungarian Starčevo ceramics. Around 5200 BC A different style prevails, the ceramics are now round-bottomed and inorganic. Settlements of this transition stage were z. B. found in Szentgyörgyvölgy-Pityerdomb ( small area Lenti ), Vörs-Máriaasszonysziget ( Balaton ) and Andráshida-Gébarti-tó (near Zalaegerszeg ). The research group led by Barbara Bramanti ( Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz ) examined ancient DNA from skeletons made of ceramic tape. The findings suggest that the wearers of the ceramic ribbon immigrated to Central Europe from the Carpathian Basin around 7,500 years ago. From there, the band ceramists could have spread in two directions, on the one hand via Bohemia and Moravia along the Elbe to Central Germany, on the other hand via Lower Austria along the Danube to southwest Germany and further along the Rhine .

According to this immigration hypothesis , there is no anthropological continuity from Europeans of the late Mesolithic to the ribbon ceramists. Then neither those nor the ribbon ceramists are to be seen as ancestors of today's European population (see the section The ribbon ceramists and the question of the ancestors of modern Europeans ). A study from 2010 even found a match between the DNA of ribbon ceramic graves from Derenburg (Saxony-Anhalt) and today's population in the Middle East . There, at the site of the Neolithic Revolution, the ancestors of the band ceramics would have to be looked for.

The immigration hypothesis described did not go unchallenged: the archaeologist Claus-Joachim Kind (1998) stated that the ribbon ceramists could be an autochthonous development in the European Neolithic. Silex artifacts in the oldest ceramic band indicated Mesolithic traditions. The similarities between ceramics from the oldest band ceramics and those from the Starčevo-Körös cultural complex are also minor; this excludes immigration from those cultures.

An autochthonous, in some cases multilocal, ceramic ribbon culture could have been established at the respective location through vertical culture transfer (i.e. a certain relationship between tradition and innovation); but this does not fit well with the striking uniformity of the culture in its area of distribution. This uniformity suggests horizontal culture transfer through transmigration; H. indigenous Mesolithic population groups may have adopted the Neolithic way of life from migrating groups (without having perished as a result). A corresponding further doctrine particularly points to the continuity of material culture. So had the flint - equipment ältestbandkeramischer settlements Mesolithic trains on what is (at faceted face remains both in certain forms sheeter , trapezoids etc.) show in the preparation of the playing surfaces as well. The band ceramics are also detached from a differently designed religious background, as Clemens Lichter (2010) notes. For example, the newly emerging circular moats in the Starčevo-Körös complex did not exist.

It is unclear what proportion the so-called La Hoguette group had, which spread from Normandy (where the eponymous site is located) to the Main - Neckar region. A pastoral livelihood is assumed for this culture , i.e. non-sedentary sheep or goat herders who have had strong economic ties to ceramic tape since the spread of the LBK. The La Hoguette group can be derived from the Cardial or Impresso culture , an early Neolithic culture that chronologically precedes the Starčevo-Körös complex and was widespread on the coasts of the western Mediterranean. It spread from the mouth of the Rhone around 6500 BC. To the north and reached the Rhine and its tributaries as far as the Lippe about 300 years before the band pottery . The proportion of pet bones is significantly greater in the La Hoguette culture finds than in the band ceramists, who conversely did more farming . Since intensive contacts between the two cultures have been documented, it is easy to imagine that the La Hoguette shepherds and band pottery farmers benefited from each other economically.

Ecological framework conditions and economy

During the period of the linear ceramic culture, a warm, maritime climate with relatively high amounts of precipitation is assumed for Central Europe . The heat optimum called the Atlantic , also known as the “ Holocene optimum”, lasted in Northern Europe from around 8000 to 4000 BC. The Atlantic was the warmest and wettest period of the Blytt-Sernander sequence , according to another source also the warmest epoch of the last 75,000 years. Both the average summer and winter temperatures were 1–2 ° C higher than in the 20th century; the winters in particular were very mild.

In Europe the Atlantic showed regional temporal differences, there were also short interruptions. Such a time-wise sharply delimited climate change is the Misox fluctuation around 6,200 years BC. During this period in Mesolithic Central Europe it was about 2 ° C colder within a few decades. The Misox surge coincides with the last outflow of Lake Agassiz into Hudson Bay . This enormous freshwater input into the North Atlantic largely prevented the formation of higher-salt water, which sinks because of its higher density . The resulting impairment of the thermohaline circulation ( convection ) in the North Atlantic weakened the North Atlantic Current as the northern branch of the Gulf Stream . The northward heat transport decreased, and in Northern Europe a regionally different but considerable cooling and drying out set in . At the same time, similar things could be observed for the Middle East, especially in the Fertile Crescent (see also Pre-Ceramic Neolithic ). The climatic consequences of the Misox fluctuation can be demonstrated in the development of vegetation in Europe for a good hundred years. A hydroclimate reconstruction by Joachim Pechtl and Alexander Land (2019) showed an extraordinarily high frequency of severe dry and wet spring summer seasons during the entire LBK epoch. Furthermore, the investigation revealed a particularly high annual degree of fluctuation in the period from 5400 to 5101 BC. And minor fluctuations up to 4801 BC. Prove. Nevertheless, the authors cautiously interpreted the significant influence of the regional climate on the population dynamics of the LBK, which began around the year 4960 BC. Have started.

With the development of a warm and humid period and an increase in average temperatures , dense mixed oak forests with demanding hardwood species spread. In addition to oak and linden trees , there were also elms , birches , pines , various maples , willows , hazelnuts and forest grasses and herbs. Hornbeams and firs only repopulated these areas not long ago.

How can the deciduous forest in the climate level of the Atlantic be reconstructed on loess soil? It was not an impenetrable forest with strong undergrowth, but rather a forest with only a small undergrowth. Elm and linden, which determined the composition of the tree population alongside the oak, are characterized by a typical dense, branched crown, so that a little undergrowth could only develop at the beginning of spring. On the other hand, the oak has a much more open treetop, so that one has to imagine more and more semi-shade-loving plants under it.

The pollen analysis of soil samples shows the changes in the proportion of different woody plants in northern Central Europe associated with the band ceramic . The primeval oak forests offered the band ceramists favorable conditions for settlement and forest pasture. The band ceramists gained settlement and arable land by (partial) clearing and felled oaks to obtain wood for houses or palisades . They apparently already used the ringing and operated Schwendbau . Over time, the number of oak and linden pollen decreased , while birch, hazelnut and ash pollen became more common; it is assumed that the above-mentioned clearings contributed to this change in the vegetation pattern. The elm in particular is of great importance as a source of nutrition for cattle (forest pasture). Because the elm must have been one of the leading types of wood in the valleys of the loess areas, because the higher degree of moisture in the soil of this tree species is a little more beneficial there than that in the loess plains.

Multiple analyzes of relict soils ( paleo- soil ) as well as the deposits contained in them result in statements about paleo-ecological conditions. Such investigations showed that in many cases the Neolithic or ceramic band settlement was preceded by a steppe climate with black earth formation (Chernosem). Humic acids and humins contained in black earth , which form the basis of the clay-humus complexes in the soil, are particularly important for adequate plant nutrition , because humic substances can adsorb and thus store ions very well. Soils rich in gray and brown human acid were, in connection with the cold-age loess deposits or black earth, an essential reason for the sustainable agricultural yield . The mild, warm summer climate of the Atlantic with its reliable weather patterns was a further prerequisite for the high agricultural productivity and the successful assertion of the Neolithic cultures in Central Europe.

During this general climate change , the low-lying loess areas were first settled by Neolithic cultures . The rural settlements of the band ceramics mainly spread along the smaller to medium-sized, branched and meandering rivers ; in the case of the smaller rivers or streams, their upper course and source area were preferred. In the case of the larger watercourses, the band ceramists sought out the edges of the low terraces , i.e. slopes in the transition area between the floodplain and the flood-protected hinterland; They lived there in long houses, mostly in group settlements with five to ten courtyards. Favorable loess soils were preferred, as were areas or microclimates with moderate rainfall and the greatest possible warmth. There are indications that it was not the watercourses per se that promoted settlement, but other factors occurring in the areas concerned, such as the loess soil, which influenced the settlement, because conversely, the largely sandy landscapes on both sides of the river had an effect rather inhibiting settlement.

The main stream of the rivers is usually accompanied by many secondary streams in the lowlands , due to the low flow speed , and the surrounding landscape up to the natural high banks of the valley edges is constantly changed by the dynamics of the water flow . In these river valleys , floodplains, the floodplains , are created, which are shaped by the constant alternation of flooding and drying out.

These preferences can also be easily related to the climatic changes during the settlement history of the Bandkeramiker: In large parts of their settlement area, microclimatic changes from rather dry-warm to more humid conditions occurred. After such changes, the people of the Neolithic period chose other places of settlement, because increased rainfall led to more violent floods that occurred in shorter periods of time ( flowing water type ), from which the ceramic band settlements in the upper third of a slope were better protected.

Typically, more differentiated vegetation communities such as the winter linden - oak-hornbeam forest and the woodruff-beech forest were found on the fertile loess sites . Here, depending on the season, forest pasture ( Hute ) and leaf hay extraction ( Schneitelwirtschaft ) were operated. The cattle pasture in the forest was mainly reserved for summer fodder management, while the deciduous hay production according to Ulrich Willerding (1996) was used for winter storage. In this respect, ceramic forest clearing and pasture for arable and livestock farming are the beginning of the anthropogenic change in the dominant ecosystem, the forest history of that epoch.

The fauna contained mammals typical of the forest such as wild boar , roe deer , bison , elk and red deer . Typical predators were badgers , lynxes , foxes , wolves and brown bears . The proportion of bones from wild animals varies greatly in the individual settlements, but decreases from the early cultures to the later ones.

Arable farming or crop production

Cultivated einkorn with husks ( Triticum monococcum )

Pea plant

( Pisum sativum )Lentil vetch

( Vicia ervilia )Common flax seed pods

With paleo- ethnobotanical evaluations of the soil samples, the cultivated plants could be determined, it was proven:

- Emmer ( Triticum dicoccum ) and einkorn ( Triticum monococcum )

- Barley and husked barley ( Hordeum vulgare )

- Trespen species such as the grass species that Karl-Heinz Knörzer called Bromo lapsanetum praehistoricum in 1971 , were typical companions of emmer and einkorn; The Trespe is a type of sweet grass , its seeds made up about a third of the large-grain grass fruits in addition to einkorn and emmer in many samples, so that it can be assumed that the Trespe was not regarded as a "weed" but was consumed

- Peas ( Pisum sativum )

- Lentil vetch ( Vicia ervilia )

- a small number of lenses ( Lens spec. ) and flax ( Linum spec. )

Another source mentions spelled ( Triticum aestivum subsp. Spelta ) and limits flax cultivation to the species Linum usitatissimum ( common flax ). A few finds show the use of rough wheat (synonym: naked wheat; Triticum turgidum L. ), millet ( Panicum miliaceum ) and oats ( Avena spec. ).

All cereal types listed can be sown as winter cereals in autumn or as summer cereals in spring . The harvest was then staggered in summer. Depending on the type of grain husk , a distinction is made between spelled (emmer, einkorn, spelled barley, spelled) and naked grain (naked wheat). In the case of husked grain, the husks surrounding the grain are more or less firmly fused with it. In the case of naked grain, on the other hand, they lie loosely and fall off during threshing . The advantage of the husked grain is that it can withstand primitive storage better, the disadvantage is that the grains have to be peeled before grinding; but for this they must be completely dry.

In summary and semiquantifying, the band ceramists mostly cultivated the spelled wheat species emmer and einkorn in the loess soils. The cultivation of naked barley and husk barley were less widespread. Other types of grain such as spelled, oats, rye and millet could only be detected sporadically.

The band ceramics cultivated different plants than the cardial or imprint culture (see above the section on the origin of the band ceramics ). It was only when the two currents later met in the Main-Neckar-Rhine area that poppy cultivation reached the linear ceramists. This can be assumed, for example, since the older band ceramics . Binkel wheat ( Triticum compactum ) only became important in the late ceramic band . The hazelnut ( Corylus avellana ) was collected as a wild fruit . In addition to geoclimatic, the geo-ecological research mentioned above also indicates a very mild climate during the spread of the ceramic band culture in Central Europe.

The band ceramists were probably Hackbauern in the sense of Eduard Hahn (1914), whereas Lüning suspected the use of the plow . The digging stick is the most important tool in hacking cultures ; but this has so far only been documented for the later Egolzwiler culture .

In 1998, Manfred Rösch was able to demonstrate an increase in both the density and the diversity of species of spontaneous accompanying vegetation in the cultivated plant stocks (so-called "weeds") through a botanical analysis of soil samples in various southern German ceramic settlement areas . These data are consistent with pure summer cultivation. But whether the increase in accompanying vegetation speaks for fallow land or perhaps just for grazing cannot be determined from the evidence. The massive occurrence of some weeds and the indications of a poor nitrogen supply to the soil suggest that the agricultural production conditions deteriorated in the course of the ceramic band culture.

Early calendar systems are generally based on observations of nature and weather. The course of the year is divided into repetitive corresponding phenomena without counting them. An observation calendar is based on natural, mostly astronomical events (such as the position of the sun , phases of the moon , the rise or position of certain stars ). With the occurrence of certain defined sky event (about the new moon , or of the day and night are equally long in the Central European Spring ) initiated a new cycle. In crops such as the ceramic band, which are involved in agriculture, it is necessary to record the seasons on a calendar . Therefore, parallel to the transition from a Mesolithic to a Neolithic society or from a hunter-gatherer society to a sedentary way of life, a transition from the lunar calendar to the solar calendar is assumed (see the ceramics stitches and the circular moat by Goseck ).

Pets and game animals

Even in the settlements of the rural, ceramic band cultures of Central Europe there were dogs that were found in graves and settlements, for example in the Swabian town of Vaihingen an der Enz . These are not supposed to be wolf-like dogs, but rather medium-sized breeds. In 2003, a separately buried peat dog ( Canis palustris ) was found in the flat ceramic settlement of Zschernitz in Saxony . The dog from Zschernitz had a shoulder height of about 45 cm, which is compared to the size of today's Spitz . It can be assumed that the neolithic dog breeds of the band ceramists already had the ability to differentiate between domestic and farm animals on the one hand, which had to be protected or which had to remain intact, and hunted game . The loss of (wolfish) escape behavior in the event of imminent danger and a lack of aggressive behavior despite the predator-prey relationship in the human communities in the canine behavior repertoire was one of the essential prerequisites for distinguishing the Neolithic domestic dogs from the wolf. In addition to the dog , which has been domesticated since the Mesolithic Age , according to Raetzel-Fabian (2000), an average of 55.2% domestic cattle and 12.2% domestic pigs were kept in the ceramic settlements . In addition, are sheep and goats proved. All of these farm animals supplied meat, skin, wool , horn , hides, tendons and bones as coveted raw materials in different ways as slaughter animals .

The immigration hypothesis on the origin of the band ceramics suggests that the livestock (and seed plants) were not created from the Central European wild stock through domestication or breeding, but were brought with them. Analysis of mitochondrial DNA shows that the pigs in Central Europe came from the areas of what is now Turkey and Iran. It can also be regarded as confirmed that all European cattle descend from the Eurasian subspecies of the aurochs ( Bos primigenius taurus ), whose original home is Anatolia and the Middle East ; so they do not come from tamed European aurochs. The domestication of the house cattle took place before the v 9th millennium. Chr. , D. H. in the Epipalaeolithic . Proof is that from 8300 BC Cattle came to Cyprus together with arable farmers ; Investigations of the mitochondrial DNA of recent domestic cattle also show that the current haplotypes of Central European domestic cattle breeds are similar to those of Anatolian cattle breeds.

However, it is still uncertain whether the current distribution pattern of domestic cattle in Europe goes back to the early Neolithic era. There is evidence of a gene flow between the Middle Eastern Anatolian populations in the early phase of the European Neolithic, but this can be traced back to the period after 5000 BC. Limited. This is interpreted as an indication of large-scale trade. Accordingly, from the middle of the 9th millennium BC reached Eastern populations domesticated Western Anatolia and the Aegean region before 7000 BC. BC, after 6400 BC In BC genetic diversity declined with the migration to the west. The Neolithic settlers reached the southern Mediterranean, but also southern France, by boat, but initially only with very few (female) cattle. Without any appreciable gene flow on the part of the native bovine species , their descendants reached around 5500 BC. Central Europe, around 4100 BC Northern Europe. Genetic diversity was again lost, especially with immigration to Central Europe.

There is also evidence that band ceramists often castrated their bulls . Oxen are less aggressive and manageable than bulls, also less muscular than those, but more muscular than cows. Since the growth plates close later in castrated male mammals , oxen grow significantly longer than bulls and become larger than them. The late closure of the growth plate also affects the bony basis of the horn, the horn cone ( processus cornualis ), which the frontal bone forms in horned ruminants. Therefore, oxen can be distinguished from bulls by the horn cones.

The band ceramists apparently used the cased milk of their cattle. However, the level of milk production of Neolithic cows differed significantly from that of modern cattle. Small, funnel-shaped vessels with perforated walls appeared at the sites where they were found, which are very similar to modern cheese-making equipment. A working group led by Mélanie Salque (2013) was also able to detect milk fat in ceramic shards from ribbon ceramic production. Likewise, the development of lactase persistence (the ability of adults to digest milk ) is associated with the ceramic band culture.

The undergrowth of the contemporary mixed oak forests offered domestic cattle rather sparse food, so that larger forest areas were required if the animals were to cover their current energy needs through grazing . This resulted in a critical size of the herds for the individual ceramic band settlements. This varied with the location, but also with the type of economy, such as long-distance pasture with winter leaf fodder use, or animal husbandry near settlements made possible by improved arable farming.

In the oldest ceramic band settlements, around 5700/5500 to around 5300, the analysis of the animal bones found, for example by Stephan (2003), suggested that the ceramic settlers in certain areas built on the technological traditions of the indigenous Mesolithic hunters, fishermen and collectors . During excavations in an early ceramic settlement in Rotteburg- Fröbelweg, the animal bones were recorded qualitatively and quantitatively, in addition to the domestic and farm animals, which represent the species population usual from the band ceramic, such as cattle, sheep, goats, pigs and dogs, but it was shown that they were only represented in low frequencies. So they do not seem to have made a major contribution to the meat supply of the settlement inhabitants. On the other hand, the hunt for the wild mammals, red deer, roe deer and wild boar, which were common at the time, was of striking importance. According to Stephan (2003), high proportions of wild animals were also observed in other, if not all, simultaneous locations in southern Germany.

Possible livestock diseases and health impairments

For questions of hygiene, it seems important that livestock husbandry expanded the spectrum of possible pathogens. A change in the microbiome surrounding humans began; as a result of the closer coexistence of LBK and their livestock or the corresponding culture followers . So-called zoonosis can be transmitted from humans to animals (anthropozoonosis) or from animals to humans (zooanthroponosis). Cattle are susceptible to bacterial zoonoses such as tuberculosis , brucellosis or anthrax and are therefore possible carriers of these diseases. The roundworm ( Trichinella spiralis ) can colonize cattle, other mammals and humans. Other parasites such as the great liver fluke ( Fasciola hepatica ) also infect humans as well as cattle; the same applies to eukaryotic unicellular organisms such as cryptosporidia . Cattle are even intermediate hosts of a human parasite, the beef tapeworm ( Taenia saginata ). The brucellosis is a so-called venereal disease . It is caused by the Brucella abortus bacterium from the Brucella genus when it infects domestic cattle . Cattle are the main hosts , while almost all mammals, including humans and poultry, are secondary hosts . The haemorrhagic septicemia in cattle caused by the pathogen Pasteurella multocida can also, albeit concern man nonspecific. On the other hand, leptospirosis in cattle , as a Weil disease, can be quite dangerous for humans.

For other health impairments, a study by Klingner (2016) on a total of 112 adult individuals from the LBK from Wandersleben ( Thuringia ) found skeletal indications that there were diseases in connection with the domestic smoke gas development at the fireplace; chronic exposure to smoke gas . But there were also strong indications in the finds for cases of tuberculosis.

A one-sided vegetarian diet promoted changes in the microbiome of the oral cavity or the dental biofilm and was associated with the increased incidence of dental caries .

Settlement

The band ceramic production was based on agriculture and animal husbandry. This suggested building settlements where water was easily accessible and where the landscape and soil conditions were suitable. In fact, flat ceramic settlements are mainly found in the lowlands of larger rivers with black earth soils, but not in the center, but in the edge area of such landscapes (up to 300 m above sea level ), such as the edge of a high terrace or the upper third of one facing the river sloping hillside. Settlements were often in close proximity to surface water, but also up to a kilometer away, such as in Kückhoven or Arnoldsweiler . The water supply from wells took place in all settlement areas and proves the great importance that was attached to a drinking water source directly in the settlement. In some cases the distance to flowing water would have been only a few hundred meters.

Important settlements are Bylany , Olszanica, Hienheim , Langweiler 8 , Cologne-Lindenthal , Elsloo , Sittard , Wetzlar -Dalheim. In the early Bandkeramik, there was often a single long house in such a settlement ; in the later there were also three to ten long houses. Characteristic longhouses of the Bandkeramische culture were found during excavations of the Bandkeramische Siedlung (Mühlengrund in Rosdorf) . In older publications, larger settlements were assumed; However, finds of house floor plans that are close together seem to belong to different periods, and it is to be assumed that houses that have become unusable were rebuilt in the immediate vicinity. Large families probably lived in the long houses of the LBK.

The central (Neolithic) innovations in a Mesolithic environment were sedentariness and immovable property . While (Mesolithic) forager cultures are more likely to have been characterized by a largely egalitarian social structure , where individually assignable property was less dominant, it gained increasing importance in sedentary cultures due to unequal distribution . An uneven distribution is reflected in the ribbon ceramic grave goods . For Gronenborn (1999), the various grave goods , such as jewelry made from spondylus shells, point to the burial sites of privileged individuals.

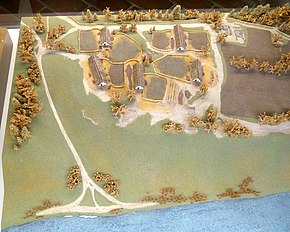

The hamlet as a typical form of settlement

Settlements made up of several longhouses are called hamlets ; these were 3 km apart. The territorial area of a hamlet comprised approximately 700 hectares. Each nave included a Schwendbau arable area of approximately 2.5 hectares .

Occasionally ditches and earth walls surrounded the hamlets. Such systems, documented in the oldest ceramic band settlements, were closed with the exception of a few passageways and represented an approach obstacle for both animals and other people. They are therefore to be regarded as fortifications , but need not have served military-strategic tasks.

Longhouses in a hamlet were about twenty yards apart. In the area between them there are storage pits , slit pits and pits with built-in components such as pit ovens . According to Pechtl (2008), a distinction is made between stoves and ovens in terms of construction . Stoves as open fireplaces can be provided with a specially prepared base plate, but have at most a low border on the side; Ovens, on the other hand, have walls. Pit ovens are ovens that are digged into the ground and whose combustion chamber is limited by the walls of the hollow.

In 1982, Ulrich Boelicke suggested the " yard model " to interpret the excavations at Langweiler 8 . This assigns all pits to a nave that are within an arbitrary radius of 25 m around its floor plan. Jens Lüning also speaks of the courtyard square as an economic area of a ceramic house . However, the model is not supported by further research.

Construction and use of the nave

The rectangular, 5-8 m wide and up to 40 m long structures contained three inner rows of posts that divided the space between the longitudinal walls into four naves. Parallel to the short wall, the posts also formed rows that divided the room into three modules.

The longitudinal axis of a nave was usually north-south to north-west-south-east. The houses stood on an area of 20 m × 5 m to 40 m × 8 m; for settlements in the Rhineland, up to 255 m² was calculated. The load-bearing elements were posts arranged in 5 rows, and often wooden posts on the northeast side . The arrangement of the posts indicated that the four-aisled house was divided into a north, a central and a south module (see diagram on the right “House types”). There were also longhouses that consisted only of the central module or only this and the northern module. In the central module, the distances between the posts were larger. A special post arrangement, the so-called Y-position, only appeared in an earlier form of the central module. In the southern module, the posts contained additional holes.

The outer rows of posts were supplemented with mud-plastered rod networks to form walls, with the builders digging deep removal pits along the side walls; in the Paris basin such a pit was even interpreted as a well. The wood consumption for the construction of long houses such as the ceramic well construction in log construction shows the high effort involved in woodworking. In the northern module, the wickerwork merged into a closed split plank wall. The argument based on the posts gabled roof was probably with straw , reeds or bark covered. It is assumed that cords held the roof together (see the chapter on cords ), although the tools of the band ceramists would have made it possible to produce simple plug-in or tenon connections . Because of the additional post holes, a false ceiling is assumed in the southern module.

One can only speculate about the use of the nave. The plank wall in the northern module could be due to a stronger influence of the weather on this house wall. The northern module could also have been the sleeping area. For the central module, additional finds and evidence of fireplaces suggest living and working areas. A storage facility is assumed in the southern module because of the possible false ceiling ; As a result, the nave was not only used as accommodation, but also for storage (e.g. after Jens Lüning). It is unlikely that the nave was not only an apartment but also a stable; At least the phosphates expected from the breakdown of animal manure cannot be detected in the soil. The pits created during the building of the house when the clay was removed were probably used as a cellar or landfill. Early research referred to them as "curved complex buildings" and wrongly interpreted them as the actual dwellings of the band ceramists.

The ceramic band houses were mostly built on loess-covered high terraces, that is, on the upper third of a ridge sloping towards the course of the water, river, stream. One had deliberately sought out these slopes to build houses there. The reason was probably the climatic conditions of the early Neolithic, so above-average rainfall was frequent. This is supported by the following indications:

- Thick calcium deposits in the Atlantic and especially in the subboreal ;

- In Central and Northern Europe, the European pond turtle , Emys orbicularis (LINNAEUS, 1758) has been identified for the ceramic period ; it prefers to live in a very humid climate;

- Two-grain einkorn dominates agriculture. This einkorn is characterized by its resistance to heavy rainfall.

In 2007, Oliver Rück proposed a long house model with a living space partially raised from the ground. So, as evidenced by excavations, the northwestern part of the building could probably still have lay directly on the sloping terrain. With the increasing slope of the hillside and depending on the length of the house itself, the distance to the ground in the south-eastern part of the house increased continuously. In the southwest part of the long houses there were additional posts (double post positions) in order to be able to maintain the statics of the wooden construction. If the distance to the running horizon was too great and thus the load on the post was increased, additional posts had to be installed. There was always a small wall moat in the northwest part of the building. In view of the high seasonal rainfall, this could have had a protective function for the part of the building in order to divert the runoff surface water.

According to Jens Lüning , a long house accommodated a family of six to eight people, its size being due to additional storage functions. In a more recent publication Biermann looks at the extraordinarily high collective workload involved in its construction and concludes that between 20 and 40 people lived in it. The different sizes and designs of the longhouses could also reflect different origins or the social rank of their residents.

Earthworks and palisades

Although the structural climax of the circular moat systems is to be relocated to the Middle Neolithic (4900-4500 BC), such ring-shaped moat and wall structures and comparable circular moat systems were assigned to the time of the Early Neolithic (5500-4900 BC) . They are counted among the cultures of the linear ceramics (LBK) and the later funnel beaker culture (TBK) (around 4200–2800 BC). The oldest systems were laid out as approximately circular, elliptical or rectangular pit-wall combinations, combined excavated trenches with raised walls, and come from the context of the LBK in the early Neolithic. Since then, deep and wide trenches have been dug, the extent of which is interpreted as an organized, collaborative work performance. Earthworks of this type were found in the period between 5500 and 3500 BC. Dated.

The archaeological exploration and recording shows coherent systems of pits, trenches, ramparts and palisades, which appear for the first time in the ceramic band and are referred to as earthworks . These may or may not enclose a settlement; The list of earthworks and palisade works of the Bandkeramischen Kultur and Meyer / Raetzel-Fabian provide an overview . Earthworks have already been demonstrated for the oldest linear ceramic band, but more frequently in the more recent.

An earthwork can form a round closed line, its longitudinal axis oriented towards the cardinal points. In 1990, Olaf Höckmann pointed out that the clearly defined trench or palisade stretches showed a noticeable preference for the north-east, south-west and north-south orientation of the buildings, while the north-west-south direction that dominates house construction East axis does not play a role here. He interpreted these alignments in connection with astronomical references, for example from solar observations to calendar regulation.

The term was initially limited to systems with a continuous trench, but now also includes other systems based on observations in Herxheim and Rosheim in Alsace. In the case of the latter, a defensive function can be ruled out because of their successive emergence and their construction as individual, overlapping long pits. Sometimes skeletons or parts of skeletons, ceramics, animal bones, flint can be found in the long pits ; they could have had a cultic meaning.

In Esbeck a fortification and settlement system ( earthworks by Esbeck ) was uncovered. Heege and Maier (1991) and others were able to prove a double moat that partially encompassed the Neolithic settlement. The same ditch and wattle fence surrounded the Eilsleben and Cologne-Lindenthal settlements. Similar to the erection of the longhouses, these fortifications were only likely to be carried out in collaboration.

Well construction

A well is a construction for pumping water from an aquifer , thus opening up a regulated water supply for the settlements. Ribbon ceramic wells consisted of pits up to 15 meters deep. There were mostly wooden structures joined together in block construction (so-called box wells) as well as hollow / hollowed-out trunk drums (so-called tube wells) that were erected from the bottom to the surface. However, it is still controversial whether a well had to be stiffened with wood, since over the years wells have been dug out in which the findings did not allow any conclusions to be drawn about wood. In the course of the construction work, the pits were backfilled with the excavation. So far there has been no evidence of a secure expansion of the construction pits (the so-called Pölzung ). Obviously, the tightly joined and also usually caulked well boxes had two functions: they once formed a storage container for the groundwater and at the same time played the indispensable role of a clearing.

The most important tool for woodworking u. a. for well was on a lower bar transversely geschäftete with the cutting edge to the striking direction Dechsel . Symmetrical ax blades that are operated in parallel are not documented for linear ceramics and did not appear until the late Middle Neolithic period at the earliest, but usually did not appear until the early Neolithic period. Experiments with replicas of ribbon ceramic dechs have clearly demonstrated their effectiveness.

Cultural techniques, population density and socio-cultural organization

The advent of agriculture made carbohydrates much more readily available for human consumption . By keeping livestock, she created a prerequisite for an increase in population density . The new techniques mentioned were accompanied by others, such as the construction of ceramic wells to secure the water supply, or the stock management . In flat ceramic settlements, questions of land and property distribution and security had to be clarified.

The population density (of any population) cannot increase further if the resources of the natural environment of that population are exhausted. More specifically, as the maximum load ( = carrying capacity ) of a living space is defined that the number of individuals of a group of people for which the group may exist in the considered habitat for an unlimited time, without him lasting harm. Examples of exhaustible resources are construction timber or energy sources such as firewood and food , which can only be obtained in limited quantities over the long term from a given area.

The social structure of the band ceramic companies remains unclear in detail. Mostly, a segmentary , low division of labor and largely egalitarian form of society without major social differentiation is assumed. In view of the interpretations of the findings, this point of view is not uncontroversial, as archaeological finds from excavations of LBK grave sites show that the grave goods differed in terms of their size and value.

The social togetherness of the early LBK was shaped by widespread family associations; they had remained connected by independent (trade) networks, as can be seen above all in the raw material supply ( Silex ).

The strontium isotope analysis from the female and male skeletal finds suggests a patrilineal or patrilocal descent. That is, a female sequence ( residence rule) to the man's place of residence .

Materials and their ways

There is some strong evidence that members of ribbon pottery settlements engaged in some form of Neolithic mining. This applies to the mining of red chalk as well as to the search for flint .

Materials sometimes covered considerable distances (possible exchange systems ). This is how Rijckholt-Feuerstein came from the Dutch province of Limburg to the Rhineland. Amphibolites were preferred as the raw material for ceramic band shoe last wedges , including metamorphic rock types of the actinolite - hornblende - slate group (abbreviation: AHS group ). Amphibolite probably came from today's Bohemia to more western settlement areas, so that contacts between people in regions even further apart can be assumed.

In the Rhineland there were larger main or central settlements for the ceramic band such as Langweiler 8, as well as smaller sub-settlements. From settlement to settlement artifacts made of flint ( synonym : flint artifacts ) have been passed on, such as raw pieces and so-called basic shapes ( cuts , cores, etc.), but also semi-finished devices such as blades and finished ones such as drills or scrapers . The finds from smaller settlements mostly come from neighboring larger settlements.

According to intra-site analyzes, i. H. Investigations into the processes within a site , such transfers are also to be assumed within each band ceramic settlement. They are probably due to social differentiations within the settlement.

Tools

A wide variety of tools were found in the vicinity of the band ceramic cultures . The attempt at a complete reconstruction of the ceramic tape tool inventory encounters the difficulty that suspected tool (parts) are missing if they were made of organic material and have decomposed .

Separating or cutting tools

First of all, the (stone) adze blades should be mentioned. An adze is a cross-cut cutting tool, i. H. its blade is inserted into a shaft in such a way that its edge passes through the plane of a cut at right angles. Drilled club heads are found less often at the sites . The artifacts of the band ceramists show real holes executed as full or hollow holes ; they are made more complex than those used in the Mesolithic.

The band ceramists often used a narrow, high type of dix, the blade of which is called a shoe last wedge , based on the shape of the shoemaker's last . The term describes the flat bottom and the curved top of the blade, which often result in a D-shaped cross-section. An experimental archaeological investigation, the "Ergerheim Experiment", showed that these stone tools can be used to fell trees without any problems. A classification of shoe last wedges according to shape type is only possible to a limited extent, since use and re-sharpening of a blade can change its shape. In addition to shoe last wedges, flat and wide blades were already available in ribbon ceramics; Dechs equipped with them are called flat axes . The cutting tools were also used as weapons, as demonstrated by injury patterns on skeletal parts found, in particular skullcap .

The band ceramists also used sickles , made from a slightly curved piece of wood. Notches were made in its concave side and sharp-edged blade knobs were attached with birch pitch in the notches . In many cases the finds show a sickle luster . This is caused by intensive use of a sickle when cutting plants, especially grasses that contain silica particles, because these act like an abrasive on the sickle.

In addition to the classic flint , other raw materials were used to produce artifacts or tools in the linear ceramic settlements. During excavations in Stephansposching according to Pechtl (2017), the following mineral raw materials were found in this linear ceramic culture of southern Bavaria: Jurassic chert , alpine radiolarite , lydite , quartzite , rhyolite , obsidian .

Ranged weapons

In the band ceramic culture, chert and flint were used to make arrowheads . Finds in the Abensberg-Arnhofen flint mine indicate that the Abensberg-Arnhofen chert was a preferred raw material for tool manufacture, especially in the late ceramic band. The arrowheads were often relatively small, their outline triangular and the side edges straight. It was easy to manufacture: blades were dismantled from a pyramidal core, these were deliberately broken and further processed by retouching . The main disadvantage of flint points is their brittleness , because if you miss a shot in the ground or a tree, the point often shatters. If it hits a bone in the body of a prey or enemy, this also happens, but the splinters are also sharp-edged and smooth and are hardly slowed down. By shifting the center of gravity forwards and due to the low air resistance due to the size, such arrowheads enable high accuracy. In the European Neolithic , arrows were preferably made from the saplings of the woolly snowball , which were very elastic and unbreakable due to their fibrous structure ( shaft ).

Fibers, cords and fabrics

A fiber is an elongated structure made of plant parts, made for everyday use and usually only subjected to tensile force (instead of pressure). Cords were probably made of bast fiber, as in other Neolithic cultures. In addition to bast from linden trees , which was very often used in the Neolithic, bast from other trees could also be processed. Depending on the tree species, they had to be " rotted " in water for different lengths of time . Stem fibers from nettles and flax were probably also used, but have not been clearly documented.

Hand spindles made of clay were found during the excavation of the Rosdorf “Mühlengrund” settlement . These spindle whorls could be used for the production of threads and thus for the production of textiles . Some finds indicate that the spinning and weaving of nettles or flax fibers made fabrics. Clay figurines and figuratively shaped vessels can be differentiated into men or women on the basis of the differences in beard hair , hairstyle , headgear and clothing. In both sexes, trouser-like trousers and throws can be seen over the upper body; however, the section is pointed for women and rounded for men.

A bark bag was found in an LBK well in Eythra south of Leipzig and was dated around 5200 BC. The bag was almost completely preserved due to the good conservation conditions in the water table.

Household or other tools

Harvested grain was crushed in sliding mills . A sliding mill consists of two grinding stones , the lower part and the upper part or rotor . To grind grain between the millstones, a person knelt in front of the person below, grabbed the runner, and pushed it back and forth. The not inconsiderable stone abrasion remained in the grist. Operating a sliding mill was a physically demanding job. Since sliding mills were often found as burial goods among female ribbon ceramists, it was more likely to have been carried out by women.

Jens Lüning assumes that the line ceramists already used the plow . However, there is no clear evidence of this.

The fact that the band ceramists mastered simple boat building is likely due to the way they settled in the area near the river, even if only indirect evidence can be found for this. So basket boats, skin boats or dugouts are to be assumed.

Jens Lüning suspects that the seating furniture depicted on the figurines, such as a bench and three-legged stool, was also used in everyday pottery.

Lighting a fire

In the LBK, too, fire was probably produced by blow lighters (percussion) and not with friction lighters (friction). Such lighters consisted of three obligatory components: a "spark dispenser" made of a fine crystalline pyritic pebble ( pyrite / marcasite ), a "spark remover", i.e. a fire stone made of hard pebbles (flint, chert, quartzite or similar) and a "spark catcher", mostly Tinder from a tree sponge (Fomes fomentarius).

The standard method of igniting a fire in the Neolithic is the “pebble lighter ”, which can be proven in various finds from the ceramic culture. They are also known as "marcasite lighters". To strike a spark , a piece of pyrite or marcasite is beaten with another piece of pyrite or a flint . The generated sparks are dropped into an easily flammable material. The pyrite with its burning sulfur content is the "spark donor", the fire stone is the "spark hammer". As a tinder sponge (Fomes fomentarius) or tree sponge, besides the tinder with similar properties, the birch sponge (Piptoporus betulinus) is also suitable .

Ceramics

In the so-called "open field fire " ( burning ) ceramics were produced from clay minerals . Pit furnaces were used for this. Such pit ovens are often found, they are ovens below the ground level in excavated earth, the furnace of which was dug out of the soil material. The artifacts, which had previously been air- dried , were lined up or stacked in such a pit on top of and next to one another; The heat input took place around this . As soon as the ceramics had warmed up evenly, the partially burned logs were pushed closer to the ceramics until the whole thing was completely covered and the pieces began to glow. The pit was then covered so that the potters could continue to burn in the reduction fire. The surfaces of the ceramics have already been smoothed using clay casting. Although the ovens did not generate very high temperatures, they were sufficient to make the vessels produced tough. In an open field fire, temperatures of around 800 ° C are reached. By definition , a firing temperature of 600 ° C is used as a fired ceramic . A field fire lasted around 5-6 hours. In a number of ceramic band ceramics, devices were found in the form of knobs, eyelets or flaps, which, according to the assumption, were used to fasten cords . The colors of the burnt earthenware ranged from yellowish-gray-beige to red-brown to light gray and dark gray-black. Such spotty, different color shades showing shards or vessels give an indication of unevenness during the fire. In principle, oxidizing- fired clay minerals result in light to reddish ceramics, while reducing-fired clays lead to darker to black color patterns.

The extent to which there was a gender-specific division of labor in the manufacture of the ceramics cannot be proven directly. Ethnographic studies indicate that such a division of labor also existed in the band ceramic cultures. It should be noted that the production of ceramics is a multi-part process, it comprises a number of work steps. So the extraction and possibly the transport of the raw material is at the beginning. This is followed by the processing of the raw material into a usable plastic mass. The vessels are then shaped by hand, air-dried and decorated in a leather-hard state. After the objects are completely dry, they are fired in the manner described above. Different physical and manual skills or requirements are required for these individual steps . Extraction, transport and preparation of the raw materials (clay, fuel, etc.) are definitely physically demanding activities that require both endurance and muscle strength . A great deal of experience is required for the open field fire, the construction of the firing pits and the fire itself, as is the shaping of the ceramics and the creation of decorations, where (manual) skill and experience are essential.

Shapes and style phases

The standard shapes LBK ceramic are: Kumpf , bottle, Butte (a bottle with five cross handles) and shell . It is very similar to the pottery of the Danubian Starčevo culture. Different styles or, better, style phases can be differentiated along a timeline . First of all, an older ceramic band from 5700-5300 BC. And a younger 5300-4900 BC. In the case of the latter western ceramic band, one can essentially differentiate between the style phases of Rubané du Nord-Ouest, Rubané de l'Alsace, Rubané du Neckar and Rubané du Sud-Ouest. The vessels of the oldest Linear Pottery had thick walls and strong organic leaner . A technique was used to manufacture the ceramics without a rotating potter's wheel, by building up strips of clay in a spiral or layering them and then spreading the joints.

A distinction is made between decorated and undecorated ceramics, which, however, represents a more technical classification, since undecorated ceramics, for T. also have decorations (e.g. border patterns). The group of undecorated ceramics mainly consists of storage vessels of coarse design and greater wall thickness. Ornate ceramics are mainly made of fine clay with thin walls.

Decorating ceramics

The decorations of the ceramics consist mainly of this culture, which gives its name to parallel bands with incised decorations. Such ribbon-like decorations with linear patterns were carved, engraved and grooved into the still soft clay around the vessel in order to be fired afterwards. In addition, there are motifs that were placed in the empty spaces between the bands, so-called gusset motifs (see illustration on the right: e.g. the three horizontal lines on the body). It can be assumed that the decorations, especially the gusset motifs, served not only a decorative purpose, but rather are to be understood as an expression of togetherness or as a symbol for social groups. The project “Settlement Archeology of the Aldenhovener Platte (SAP)” (Rhineland), which began in 1973, resulted in a catalog of features that offers a recording system for processing the ceramics and has recently been revised, supplemented and made available online by the catalog of features .

Jewelry and artistic representations

The band ceramists used the mussel shells of the prickly oyster ( Spondylus gaederopus, also called Lazarus rattle), which occurs in the Black Sea, the Mediterranean Sea and the adjacent Atlantic. They made arm rings, belt buckles and pendants from the spondylus shells; they can be found mainly in burial fields, such as Aiterhofen- Ödmühle in Bavaria and Vedřovice in Moravia. The jewels found in the inland, far from the seashore, indicate the trade networks that already existed in the Neolithic over great distances.

The anthropomorphic sculpture

The most diverse types of figurative anthropomorphic representations have been found in the excavations since the earliest band ceramists. Often they are full or hollow sculptures, carved human representations and figurative finds made of bones. The sculptures are stereotypical and are derived from the culture from which the LBK arose, the Starčevo culture. As a cultural phenomenon they accompany the spread of ribbon ceramics in Central Europe, whereby they are limited to the settlement area of the oldest ribbon ceramics and find concentrations are evident in Central German, Austrian-Slovak and Main Franconian-Hessian areas. A total of around 160 fragments are known, which are spread over a little more than 120 sites. The group of statuettes is therefore one of the rare finds within the ceramic spectrum.

Small figurative sculptures are made of clay , are small in size and have almost always been found broken. The representations of the round eye sockets, the decorative element of the nested angles, the arms often pushed into the sides and the curly hairstyle of some statuettes are originally of band ceramic origin . While there are no known anthropomorphic sculptures from the Middle Neolithic cultural groups in western Germany ( Großgartacher Kultur , Rössener Kultur , Hinkelstein group ), there are some figurines of stitchery ceramics in Saxony and Bohemia , but very diverse and numerous figurines in the simultaneous eastern Lengyel culture .

Many figures, such as the seated ("enthroned") and richly decorated sculpture of the older LBK von Maiersch , lack clear gender characteristics. Jens Lüning interprets this incised decoration - including that of the animal-shaped ones - as clothing, which is plausible in various cases, at least when it comes to the clear depiction of belts and necklines of clothing items. Hermann Maurer (1998), on the other hand, focuses more on ornaments that are reminiscent of skeletal representations and are understood by him in the sense of a cross-cultural " X-ray style ".

The fragment of the “ Adonis von Zschernitz ” dating to the middle to younger LBK represents the oldest clearly male ceramic clay figure so far, along with the sculpture from Brunn-Wolfsholz. Dieter Kaufmann assumes in 2001 that these little figures were intentionally broken, which he said Hypothesis that could have served as so-called substitute victims. This is supported by the fact that the sculptures were broken not only at weak points (head, arms, legs) caused by their manufacture, but also at the torso, for example the “Adonis von Zschernitz”. All sculptures come from house or settlement pits - unless they are readings - which suggests a cultic or ritual meaning in the house.

Figural vessels

In addition to sculpture, there are also anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figural vessels. Some vessels - such as the bottle-shaped ones from the older linear ceramics from Ulrichskirchen and Gneidingen - have depictions of faces or they stand on human feet.

Clothes, headgear and hairdressing derived from statuettes

For Jens Lüning (2005), (2006) the figurative-anthropomorphic representations made of clay represent an important source material for the reconstruction of hairdresses , headgear but also clothing of men and women of the band ceramic culture. The figurines, also known as idols, are mostly between 10 and 35 cm high and, according to the working hypothesis , would have played an important role in ancestral cult . In addition to these objects, finds from ribbon ceramic settlements, such as the spindle whorls and weaving weights , testify that fibers , probably flax or flax and wool-like fibers, are tied in principle. Further indications are finds from ceramic wells , which were described as coarse to fine meshes . There is also an imprint of a linen fabric on a piece of ceramic clay from Hesserode , Melsungen district in Northern Hesse . From these finds and their interpretations, attempts were made to reconstruct both the clothing and the hairdress. The male clay figures of the band ceramics very often have diverse headgear. Lüning suspected in 2006 that these could have consisted of leather ( tanning ), braid, linen or felt and also combinations of these materials.

For the manner in which hair was worn, different hair styles were derived from the representations on the figurines; such as the so-called "top curly hairstyles" and "back of the head curly hairstyles". In the first case, the curls would sit on the top of the head, while in the second case the curls were arranged on the back of the head, while the hair on the front head would have been laid out smoothly. As a third form, a “ pigtail hairstyle with a fringe of hair” could be derived, then a fourth so-called “ribbon hood hairstyle” - a band divided the hair from the forehead area to the neck - and a fifth “snail hood hairstyle ” and a sixth the ( cornrow-like ) “ Ear hairstyle ". The extent to which the hairstyles shown on the clay figurines matched the (everyday) hairstyle of the band ceramists remains hypothetical.

Due to the rich symbolism on the clay figures, the differences in the shape of the hairdresses and the headgear as well as the different patterns on the (figurine) clothing, it is assumed that this could have been the expression of the corresponding characteristics of the ceramic families, lineages and clans .

Graves and spirituality

Dealing with the dead

There are frequently occurring features that are to be regarded as characteristic of the band ceramists:

- Establishment of burials mainly within extramural burial fields

- Burial of only one deceased per grave

- The corpse is furnished with some gender-specific additions

- Bedding of the corpse in a crouch on the left side of the body

- Maintain an approximate orientation from east to west

The linear ceramics knew cremation , partial and body burials on grave fields , in settlements and in other places. Individual and collective burials were found, sometimes both forms of burial on the same burial ground.

In the case of body graves, a corpse was mostly placed on the left, more rarely on the right, crouching down ( stool grave ). Its longitudinal axis (anatomically: longitudinal axis ) mostly corresponded to the north-east-south-west direction, the imaginary direction of view often the east or south cardinal direction . The dead were buried in traditional costumes and with additions, with gender-specific differences. Typical costume components were chains and headdresses, arm rings and belt clasps. They could contain pearls that came from the prickly oyster ( Spondylus gaederopus ); this sea shell is widespread in the Adriatic and Aegean Seas and was traded over long distances. Beads were also made from stone and bones . Jewelry made from snails is documented in the Danube region, e.g. B. in the large burial ground of Aiterhofen-Ödmühle . In the hip and leg area there were often bone gags with an as yet unclear function. Millstones, shoe last wedges , arrowheads, colored stones ( red chalk , graphite ), animal bones, ceramics, spondylus and quartzite beads as well as bone gags remained from other additions .

A second form of linear ceramic burial could be interpreted as a secondary burial . In the Herxheim mine, for example, the hand and tarsal bones were almost completely missing . Shards of deliberately destroyed clay pots showed band patterns from far away settlement areas; Isotope examinations have even detected human enamel from non-band ceramics. Other bone finds from Herxheim, however, showed traces of processing as with slaughter cattle, which indicate cannibalism within the LBK (see section on cannibalism in Herxheim ). The scattered, small-scale bone finds from the Jungfernhöhle near Tiefenellern were initially interpreted in this way; after detailed investigations, however , Jörg Orschiedt assumed a secondary burial for them.

Dead or sacrificial ritual

According to Norbert Nieszery (1995), there are four stages of ribbon ceramic dead or sacrificial rituals , some of which are chronological:

- Prothesis and cult activities at the (open) grave (paint spread, fire sacrifice, deliberate fragmentation)

- Manipulation of corpses or skeletons (exhumation, empty graves)

- Transfer of a final dump site and domestic cult (archaeologically not verifiable)

- Burial and dumping, possibly also construction victims

There is only evidence (of whatever kind) for about 20% of the expected deaths in a resident population; Nieszery considers this group to be a privileged part of society (see grave field ).

Jörg Orschiedt interprets the finds from the Jungfernhöhle , a Neolithic cult site in the Bamberg district , as an expression of this cult . The at least 40 mostly female skeletons (at least 29 were children under the age of 14) puzzled because all of them were incomplete. It cannot be a burial site as the skeletons were also scattered around. All skulls were shattered and some long bones splintered, suggesting that the bone marrow had been removed. There were no teeth in the jaws.

In the ceramic sepulchral culture , the red chalk played an important role. Scattered red chalk within the graves, coloring of the dead or additions in the form of cut colored stones or vessels filled with red chalk paste were an integral part of their cult of the dead. It is believed that the addition of red chalk is a special addition. Red chalk appears mainly in the more richly furnished ribbon ceramic graves. Usually, the dead were buried in a stool on the left, facing east-west; men received stone tools and weapons as grave goods, women ceramics or jewelry.

Numerous different large grave fields were excavated at the Herxheim site, in which the dead were buried in simple earth pits. As at other excavation sites, most of the corpses were stored sideways for burial with arms and legs drawn up. Overall, the number of buried dead who were lying on their backs and stretched out or who were previously cremated is rarer. The burned bones were then placed in a grave pit.

The grave goods at the Stuttgart-Mühlhausen cemetery , Viesenhäuser Hof , for the buried women and also children, were limited to ceramics, apart from the ubiquitous red chalk dye. The men's graves, on the other hand, had a much more varied design: In addition to red chalk and ceramics, there were food additions, arrowheads, cut stone tools, bone and antler tools, but also items of equipment such as B. to light a fire, as well as spondylus shell jewelry and robe gag were exposed. There were also above-average grave decorations with red chalk packs, dechs, spondylus and quartzite pearls and bone gag.

It is noticeable that when examining the spectrum of grave goods in the ceramic burial fields, the artefacts of spondylus conch shells , which appeared to be reserved for a small group of men and women. Whether this find situation suits religious officials remains undetermined. Possibly the wearing of the mussel shells was not limited to a function as body ornament, due to profane prestige, but it could also have been a carrier of magical-spiritual powers and the utensil of ritual specialists.

The mass grave in Halberstadt, discovered in 2013 by an excavation team from the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments and Archeology in Saxony-Anhalt , can be dated to the same time period using the radiocarbon method ( 14 C) as the already known graves from other parts of Germany and Austria. Comprehensive investigation of the mass grave recovered in the block revealed new aspects of the collective, lethal use of force . The distribution of the injuries on the skullcap from Halberstadt differ from that of other sites at the same time. The fatal injuries were placed almost exclusively on a specific area of the back of the victim's head, mainly on the occiput and parietal bone . With one exception, these are younger men who have hardly any other ailments other than the serious injuries that occurred around the time of their death . Children are completely absent from the mass grave in Halberstadt. Among other things, it is hypothesized that this was a group of prisoners of foreign origin who were killed in a controlled manner.

References to cannibalism (Herxheim)

"The archaeological criteria for cannibalism are broken bones, hacking and cut marks , longitudinal splitting of the long bones for the medullary and opening of the skull for brain removal, as well as the effects of fire, which occur in the same or a similar way on animal bones and suggest the same treatment of humans and animals . "

Whether there was some kind of cannibalism among the band ceramists - cannibalism in extreme situations (e.g. due to lack of food) or in its ritual or religious manifestations - can not be clearly proven from the current finds . Although the bones come from recently deceased corpses , it seems reasonable to assume that the bodies will be dissected on site, and the type of cut marks left on the bone also suggests that the meat was systematically cut up and removed. This interpretation would essentially contradict a second burial. A subsequent ingestion in the sense of cannibalistic acts is neither proven nor proven according to the current state of knowledge.

If cannibalism had taken place, it would have to be clarified for what reasons this was carried out. If it was the consequence and consequence of acts of war, an expression of a critical change in the relationship between man and the environment (in the sense of an ecological explanatory model), it was the demonstration of the actions of a local ceramic band culture, exclusively religious ideas moved people in their actions or Did the most varied of types, such as invasions , catastrophes and epidemics (in the sense of a non-ecological explanatory model), lead the band ceramists to such actions and other things?

Incidentally, there are only a few band ceramic sites ( Herxheim , Jungfernhöhle , Talheim , Kilianstädten ) in which human skeletons can be used to infer a violent death.

Hypotheses on a spiritual system

As with all non-literate cultures of pre - and early history can about the world view or the spiritual (religious) ideas of the people of the Linear Pottery no reliable statements are made. The anthropomorphic (human-shaped) sculptures and scratched drawings, which have always been of great interest in research, provide clues. The majority of specialist publications classify them in the religious area of ribbon ceramics (compare Archaic Spirituality in Systematized Religions ). Some authors conclude from the grave goods ( paraphernalia ) that the plot must be embedded in a religious-spiritual narrative; a position that did not go unchallenged.

It can be assumed from these narratives that they connected the natural with a supernatural world and were accompanied by rituals. According to Clive Gamble , the narrative is carried by the imagination of human communities, which makes it possible to imagine beyond the here and now and to exchange the contents with one another in a verbal manner. According to Gamble, these systems of ideas, as an integral part of social life, not only fostered the sense of community of a single local group, but created a form of identical (cultural) community over a greater territorial distance.

Furthermore, the underlying scientific constructs or concepts on matriarchy or the (religious) worship of a mother goddess are in part only poorly documented in the scientific discussion or have to be classified in a different framework ; in any case, they often leave room for an ideologically colored discussion. From this it is conclusively derived that the conclusions, which are presented as an interpretation of the find and are based on those hypothetical constructs, can only be read with sufficient criticism.

Fertility cult

The seasons with the rise and fall of the water levels in the rivers, and the course of the stars repeat themselves periodically, as well as the sowing and harvesting or the calving of the domestic cattle. Some researchers associate a reverence for fertility with the new mode of production (agriculture, animal husbandry) and as a result of observing the growth and decay in nature . The woman and her childbearing capacity were understood as their manifestation. It is therefore assumed that the ceramic ribbon sculptures represented women or goddesses .

In 1896, Ernst Carl Gustav Grosse divided the economic or production forms into five categories, the band ceramics formed the cultural level of low or early agriculture. In these cultures, women or the feminine had a noticeably high position, which is evident in the pictorial representations. The groups were organized matrilocal .

Svend Hansen , on the other hand, is of the opinion that the connection between women and fertility was a construction of the 19th century and could in no way be transferred to the Neolithic . A developed cult around a female deity with temple complexes and associated priesthood cannot be determined for the Neolithic in the archaeological find inventory. His criticism is based primarily on the fact that the sex of many statuettes cannot be clearly determined. From this he concludes that the assignment of the female gender in the statuettes was based on interpolation. With the questioning of the female sex, in his opinion, the theory of the cult of a fertility goddess collapses.

Primal mother

On the ceramics there is quite often the motif of stylized figures with raised arms and mostly spread legs. Even if the gender is usually not recognizable, the religious scholar Ina Wunn took the view in 2014 that these were women in conception or childbearing posture and iconographic representations of a primordial mother, such as those found in Çatalhöyük , for example . It is said to have been associated with birth or rebirth and death . Whether there was a matrilateral cult around a “ primordial mother ” in the band ceramics cannot be determined from the finds. In 1999, Wunn suspected that there were no “ fertility cults ”. Cult dramas of a deity who changed over the course of the year and was associated with the change in nature were of much later date and could not be proven for the Neolithic. Wunn also suspects that the other female sculptures represent ancestral and guardian spirits , some were also worn as amulets .

Ancestral cult

The interpretation of the sculptures and incised drawings as ancestral figures is also derived from the Neolithic economy. So it would have been necessary for agricultural societies to legitimize their land ownership through the existence of ancestors . Ina Wunn (2009) also suspects a house cult with its veneration of ancestors as an integral part of the religious life of the band ceramists, with the secondary burials on the one hand attesting to the ancestor cult and on the other hand in this ritual the celebration of death as a stage of transformation and transition. Representatives of the ancestry such as Jens Lüning mainly point out the following archaeological findings:

- Findings in houses, especially near the herd. The idea that ancestor worship is linked to the domestic sphere is taken over from religious studies in archeology .

- Some of the anthropomorphic sculptures are miniature vessels. In an ethnological context, these are associated with food and drink offerings.