Connection of Austria

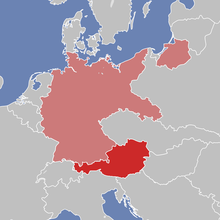

The “Anschluss” of Austria, or “Anschluss” for short , have been used since 1938 to refer to the processes with which the Austrian and German National Socialists initiated the incorporation of the federal state of Austria into the National Socialist German Reich in March 1938 .

On the night of March 11-12, 1938, following telephone threats from Hermann Göring , before the German troops marched in, Austrian National Socialists replaced the Austro-Fascist corporate state regime . From March 12th, Wehrmacht , SS and police units took command. The National Socialist federal government under Arthur Seyß-Inquart , appointed by Federal President Wilhelm Miklas that night, carried out the “Anschluss” administratively on March 13, 1938 on behalf of Adolf Hitler , who had arrived in Austria the day before. It gradually brought about the complete dissolution of Austria in the German Reich and the participation of many Austrians in the National Socialist crimes . Considerable parts of the Austrian population welcomed the "Anschluss" with jubilation, for others, especially the Jews of Austria , the "Anschluss" meant disenfranchisement, expropriation and terror .

The Federal Constitutional Law on the reunification of Austria with the German Reich , passed on March 13th by the Federal Government, ended the legal existence of the dictatorial Austrian federal state . The Republic of Austria, reestablished in 1945, considers the “Anschluss” to be void ex tunc (from the beginning). Its statehood and the consequences for the continued existence of Austria from 1938 to 1945 are controversial.

The rule of National Socialism lasted in Vienna and the surrounding area until Vienna was conquered by the Red Army in mid-April 1945. The “Anschluss” was declared “null and void” in the declaration of independence of April 27, 1945 . In many other parts of Austria the Nazi regime did not end until the end of the Second World War in May 1945; Thus the Tyrolean capital Innsbruck was handed over to the invading units of the US Army on May 3, 1945 by Austrian resistance fighters, who had replaced the Nazi regime .

prehistory

Invited by Napoleon , Franz II accepted his conditions and in 1804 accepted "for us and our successors [...] the title and dignity of hereditary emperor of Austria". That was the end of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation , which was formally confirmed in 1806. As a result, the German (now often: German-speaking) hereditary lands of Austria (as well as the lands of the Bohemian Crown ) and the other states that bound them were divided: Thus, at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the German Confederation was created as a new political union . This loose amalgamation of 41 German individual states, however, did not do justice to the aspirations for a unified state.

As a result, different approaches arose to achieve this goal: on the one hand, the Greater German Solution , a new, strongly federalist German state under the leadership of the House of Habsburg , the historic Roman-German Imperial House, including the German states of the Austrian Empire (which would have meant that the Danube Monarchy of the Habsburg would have been divided by the German external border) - and on the other hand the so-called small German solution under the hegemony of the Kingdom of Prussia .

The inclusion of the German part of Austria in a German nation-state was already discussed in the Frankfurt National Assembly in 1848/49. Archduke Johann of Austria was elected by her as imperial administrator in the spirit of the Greater German solution . In his speech of March 13, 1849, the constitutional historian Georg Waitz opposed the connection between the German and non-German “ nations ” in the Habsburg “overall monarchy” and said that German-Austrian deputies should regard it as their task to prevent the hereditary empire Austria's entry is possible at least for the future.

The small German solution was realized after the victories of Prussia and its allies over Austria in the war of 1866 and over the French Empire in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 . In 1871, the German Empire was proclaimed an empire in the Palace of Versailles near Paris , the amalgamation of German principalities and kingdoms under the leadership of Prussia, but without Austria.

Interpretation of connection requests

Friedrich Heer traced the wishes of the German-speaking population of the former Habsburg hereditary lands back to the time of the Counter-Reformation and sees them as closely linked to the centuries-long political and religious confrontation between Protestant Northern Germany and Catholic , multilingual Austria, which was subsequently brought about by the great European powers Prussia and the Habsburg Monarchy was born. The Protestants saw in the evangelical north of the “ German Empire ” the redemption from the perceived “incarceration” by the Pope and Emperor . According to the army , the first center of an independent Austrian national consciousness was Vienna , which was opposed by the rebellious states, from Upper Austria , Carinthia and Styria , as the multicultural residence of the supranational Habsburgs . This thesis is empirically supported by showing that Upper Austria was a main area of resistance at the time of the Peasant Wars and that centuries later at the time of the Nazi coup attempt in Vienna, a particularly large number of illegal National Socialists were active.

Efforts to join forces after the First World War

The end of the First World War brought the downfall of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and also the breakup of the predominantly Catholic multiethnic state of Austria-Hungary . According to Emperor Karl I's Manifesto for Cisleithanien , the new state of German Austria was founded on October 30, 1918 , before the Villa Giusti armistice on November 3, 1918, with the establishment of which the representatives of the new state wanted nothing to do: Asked by the Kaiser , they just didn't comment on it.

On November 22, 1918, the Republic of German Austria determined its (desired) national territory , the borders of which, however, had not yet been recognized in a peace treaty with the victorious powers or by the neighboring countries. Even German Bohemia and the Sudeten lands belonged to it, as are the German-speaking islands of Brno , Jihlava and Olomouc .

The provisional national assembly and the provisional German-Austrian government, an executive committee appointed from their midst, which was called the State Council , saw the constitutional connection with the now also republican German Reich as the only possibility of political existence, in particular because it turned out that the other successor states of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy were also not interested in a loose confederation .

German Austria and the Weimar National Assembly

As early as November 9, 1918, six days after the armistice between Austria-Hungary and the Entente power of Italy, the provisional national assembly turned to the German Chancellor with the request that German Austria be included in the reorganization of the German Empire. The next day the State Committee for German Bohemia agreed to this request. On November 12, 1918, the law on the form of state and government was unanimously approved by the Provisional National Assembly for German Austria. His second article read: "German Austria is part of the German Republic".

Most active politicians had previously thought in larger dimensions (of the previous Cisleithanien ) than those of a small state. In view of the fact that economically important regions no longer belonged to the national territory, “Rest of Austria” appeared to them as not viable. The famine winters of 1918/19 and 1919/20 dramatized this viability debate .

Not only German national sentiments played a role. So the Social Democrats feared - as was rightly shown later - that they would be put politically on the defensive in predominantly rural-conservative German Austria, and hoped that socialism would be implemented within the framework of the German republic . Among the Christian Socials, on the other hand, the aversion to the Viennese centralism felt in this way played a not insignificant role. In many cases, it was not a unilateral union, as it was finally completed in 1938, that was advocated, but an amalgamation of federal states with equal rights.

For centuries, the German Austrians were used to living in an imperial empire and could not identify with the new small state. In this situation, psychologically adept, the assertion was launched and constantly fed that the relatively small rest of Austria was not economically viable. In fact, however, significant businesses and branches remained in the country.

The German reaction to the vote of the provisional Austrian National Assembly in November 1918 for the Anschluss was positive. The Council of People's Representatives , under its chairman Friedrich Ebert, announced on November 30, 1918 in the ordinance on the elections to a constituent national assembly in Article 25 that if the German national assembly decides to accept German Austria into the German Reich according to its wishes, its deputies would join the German National Assembly as equal members. Citizens of German Austria were given the right to participate in these elections. The law on provisional imperial power , the emergency constitution presented by the people's representatives Ebert and Scheidemann, already proposed the first measures for Austria to participate in German legislation. According to § 2 Austria should participate in an advisory capacity before joining the German Reich.

The German National Assembly and its constitutional committee made the appropriate decision in February and March 1919. A comparable regulation was also included in Article 61, Paragraph 2 of the Weimar Constitution . According to the "connection protocol" signed by the two foreign ministers Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau and Otto Bauer on March 2, 1919, "German Austria should enter the Reich as an independent member state ". Areas with a German-speaking population such as German Bohemia and the Sudetenland should "be connected to the neighboring German federal states ".

The victorious powers criticized the connection protocol as a violation of the Treaty of Versailles accepted by the German Reich on June 28, 1919 and demanded the change. The German representatives complied with this in a formal declaration on September 18, 1919: The constitutional provisions on German Austria, in particular regarding “the admission of Austrian representatives to the Reichsrat ”, are invalid until the “League of Nations Council ” changes the international situation in Austria accordingly will have agreed ”. In the Treaty of Saint-Germain with the preservation of Austrian statehood, which was concluded in September 1919, a practically insurmountable hurdle was set up for German-Austria, recognized as the successor of (old) Austria, to unite with the German Empire. In the Versailles Treaty , Germany was forced to declare void Article 61 (2), which had just been adopted, and which gave Austria an option to join (see “ Ban on joining ”). The Allies blocked the union of Austria with Germany in two ways. At the government level, the connection was no longer actively pursued for the time being. With the ratification of the peace treaty in October 1919, the state of German Austria changed its name, as required, to the Republic of Austria .

However, the Anschluss remained a long-term goal for various reasons, above all for the Greater German People's Party , the German National Movement and for the Social Democrats ("Anschluss an Deutschland is Anschluss an den Sozialismus", the slogan of the Arbeiter-Zeitung , central organ of the party). The Christian Social Party also advocated it politically.

Follow-up efforts in the Austrian states

While the Anschluss movement of 1918/19 was still strongly shaped by socialist politicians, in the following years it shifted to Christian-social and conservative-monarchist-dominated countries in Austria that wanted to break away from “ Red Vienna ”.

Vorarlberg voted in a referendum in favor of annexation to Alemannic Switzerland , which was rejected by both the Swiss Federal Council and the Austrian state government .

After the failed attempt at restoration by the former emperor Karl I , who had traveled to Hungary as King of Hungary from exile in Switzerland on March 26, 1921 and tried to take over the government again, the still monarchist-conservative group grew stronger coined federal states opposed the republican government in Vienna. With support from neighboring Bavaria, where the socialist Munich Soviet Republic had been defeated two years earlier, the first Austrian Home Guard were formed in Salzburg and Tyrol . These were made vigorously for a merger with the now conservative-ruled Germany of the Weimar period one. Even monarchists, who had previously rejected the merger as a “Jewish invention”, openly sought it together with the German Nationals .

In April 1921 the Tyrolean state parliament had a vote in which a majority of 98.8% voted in favor of the merger. A vote carried out on May 29, 1921 in Salzburg resulted in an approval of 99.3% of the votes cast.

Further votes were prevented by protests by the guarantee powers of the peace treaty, especially the French government. In the event that other federal states should follow, threats were made to prevent foreign loans to economically weakened Austria. Federal Chancellor Michael Mayr (CS), who had called for the suspension of all planned related votes, resigned on June 1 when the Styrian state parliament announced that it would still be able to vote. His successor was Johann Schober , who had no party to the German nationality (at the same time Police President of Vienna), who prevented further votes and referred those who were striving for the merger to a later, more favorable time.

Geneva Protocols and Lausanne Protocol

The ban on joining in the Geneva Protocols of October 4, 1922 between the governments of France , the United Kingdom , Italy , Czechoslovakia and Austria was reaffirmed - a prerequisite for the granting of bonds from the League of Nations to Austria in the amount of 650 million gold crowns . Against the resistance of the Social Democrats, the National Council adopted the Geneva Protocols; they were a prerequisite for the containment of inflation and the 1925 change from the krone currency to the shilling .

Once again, the 1932 protocol was the subject of the prohibition of affiliation in the Lausanne Protocol , where it was one of the conditions for the granting of another League of Nations loan that Austria had to take on in order to cope with the effects of the global economic crisis .

Positions of the parties

All Austrian parties - including the Communist Party of Austria , which after a successful revolution demanded the annexation of "Soviet Austria" to "Soviet Germany" - were in principle for unification with the German Reich before 1933. The Social Democratic Workers' Party of German Austria (SDAPDÖ), for example, still called in 1926 in the predominantly Marxist -oriented Linz program to join the German Republic "by peaceful means" . However, she deleted the corresponding passage "in view of the situation changed by National Socialism in the German Reich" at her party congress in 1933. The Christian Social Party (CS) and the Patriotic Front that emerged from it also opposed the annexation to the " Third Reich ".

In the so-called socialist trial in 1936, the defendant Roman Felleis declared that the workers would “only stand up for this state in the future when it returns to the home” on the question of the active intervention of the Austrian social democracy, which was banned in 1934, against the threat to Austria from National Socialism for their rights, for their freedom. [...] Give us freedom, then you can have our fists! ”The defendant Bruno Kreisky said at the trial:“ Only free citizens will fight against servitude. ”

Austria and Nazi Germany 1933–1937

With the takeover of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany, the general conditions in 1933 changed fundamentally. Adolf Hitler , who was born in Upper Austria and lost his Austrian citizenship in 1925 and became a German citizen of the German Reich in 1932 at the age of 43 , adhered to this in spite of the demand written in his book Mein Kampf in 1924/25: “German Austria must go back to the great German motherland” foreign policy initially back. He did n't want to upset Benito Mussolini because he wanted an alliance with him.

On July 25, 1934, the Austrian National Socialists under the leadership of SS Standard 89 attempted what was later to be known as the July Putsch against the dictatorial corporate state , but it failed. Some putschists managed to penetrate the Vienna Federal Chancellery , where Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss was so badly injured by gunshots that he, left without medical assistance, succumbed to the injuries a little later. Hitler denied that the Germans were involved in the attempted coup. The Austrian national organization of the NSDAP, which had been banned since 1933, continued to receive support from the German Reich, but the German regime increasingly began to infiltrate the political system in Austria with confidants. These included, among others, Edmund Glaise-Horstenau , Taras Borodajkewycz and Arthur Seyß-Inquart .

After the start of the Italian aggression against Abyssinia , Great Britain demanded sanctions against Italy before the League of Nations in October 1935 and subsequently pursued the dissolution of the Stresa Front and the Locarno Treaties . Mussolini was thus isolated internationally and pushed to Hitler's side. For Austria's ruling Fatherland Front, this meant the loss of an important patron, since Italy was the guarantor of Austria's national independence .

Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg , successor to the murdered Dollfuss, now had to look for ways to improve relations with the German Reich. On July 11, 1936, he concluded the July Agreement with Hitler . The German Reich lifted the one-thousand-mark ban imposed in Austria in 1933 as a result of the NSDAP 's ban , imprisoned National Socialists were amnestied and National Socialist newspapers were re-admitted in Austria.

In addition, Schuschnigg accepted the National Socialists' representatives into his cabinet . Edmund Glaise-Horstenau became Federal Minister for National Affairs, Guido Schmidt became State Secretary in the Foreign Ministry , and Seyß-Inquart was admitted to the State Council . In 1937 the Fatherland Front was opened to the National Socialists. The NSDAP was able to reorganize itself in newly set up "People's Political Units", which were mostly under the direction of National Socialists.

1938 crisis

The meeting at the Berghof

After consolidating his alliance with Mussolini, the Berlin-Rome axis in October 1936 and Italy joining the Anti-Comintern Pact in November 1937, it became increasingly clear that Austria's independence would no longer be an issue of conflict between the two powers. At the same time, Hitler could not be entirely sure that Rome would accept the annexation of Austria.

When Hitler explained his military plans to the Wehrmacht leadership on November 5, 1937 , which was recorded in the so-called Hoßbach record, he named the year 1943 as the latest date for the annexation of Czechoslovakia (→ smashing of the rest of Czechoslovakia ) and Austria Under favorable circumstances, this could take place as early as 1938. At that point in time, Hitler was still planning to take Austria militarily. At the same time, however, he still shied away from war . A few weeks after the meeting held by Friedrich Hoßbach on December 16, 1937, he declared that he did not want a “brachial solution” to the follow-up question “as long as this is undesirable for European reasons”. Apparently he was hoping for a seizure of power by the Austrian National Socialists without outside help, as he had succeeded in doing.

The Nazi underground movement in Austria was therefore encouraged from Berlin, and its influence has grown since the July Agreement. Chancellor Schuschnigg's efforts to obtain a British declaration of guarantee failed in the early summer of 1937. The German ambassador in Vienna, Franz von Papen , advised him to meet with Hitler at the beginning of February 1938, to which Schuschnigg agreed after some hesitation. With Seyss-Inquart he worked out a series of concessions that he wanted to submit to Hitler. Without Schuschnigg's knowledge, Seyss-Inquart passed the planned concessions to Hitler.

On the morning of February 12, 1938, Schuschnigg arrived at the Berghof in Bavaria . Hitler received him on the stairs of the Berghof and led him into his study. After briefly responding to Schuschnigg's reference to the beautiful view, he suddenly started talking about Austrian politics: Austria's history was an uninterrupted treason. This historical nonsense must finally come to an end. He, Hitler, was determined to put an end to all of this, his patience was exhausted. Austria stands alone, neither France nor Great Britain nor Italy would lift a finger to save him. Schuschnigg only had until the afternoon. At lunch Hitler showed himself to be an attentive host, but the three generals who were to command a possible operation against Austria were also sitting at the table. In the afternoon, Ribbentrop and Papen presented Schuschnigg with a document with demands that went well beyond Schuschnigg's planned concessions. Hitler threatened the invasion of the Wehrmacht if Schuschnigg did not sign the list of demands. Demands included the lifting of the party ban for the Austrian National Socialists and their full freedom of agitation, increased involvement in the government and that Seyß-Inquart should become Minister of the Interior , Glaise-Horstenau Minister of War and Hans Fischböck Minister of Finance. Hitler refused to negotiate a change to the text. When Schuschnigg declared that he was ready to sign, but could not guarantee ratification, Hitler summoned General Keitel . Hitler now agreed to give the Austrians three days to sign the document. Schuschnigg signed and declined Hitler's invitation to supper . Accompanied by Papen, he drove to the border and reached Austria again in Salzburg . Schuschnigg bowed to the threats and believed that the Berchtesgaden Agreement could secure Austria's independence. As requested by Hitler, Seyss-Inquart was appointed Minister of the Interior on February 16, thereby gaining control of the Austrian police .

Hitler, too, was initially satisfied with the result: according to the historian Henning Köhler , he had only allowed the crisis to escalate for domestic political reasons, in order to divert attention from the Blomberg-Fritsch crisis , and achieved a better result than expected.

The Berchtesgaden Agreement led to protest strikes in Viennese factories on February 14, 1938. On February 16, representatives of these factories asked for a personal interview with Schuschnigg in order to explain the willingness of the workers to fight for a free Austria. Schuschnigg did not respond to this until March 4th. On March 7th there was a shop steward conference in the social democratic workers' home in Floridsdorf ; the only meeting of its kind that did not have to be held in a conspiratorial manner due to the SDAPÖ's party ban . The government did not respond to the demand for elections in the trade union federation established by the dictatorship.

For the referendum announced by Schuschnigg, the Revolutionary Socialists printed 200,000 leaflets, which were burned after the vote was canceled.

Hitler's ultimatum

The pressure was maintained through military preparations against Austria.

When Göring asked for a statement, the British ambassador Nevile Henderson explained to Hitler on March 3, 1938, in line with the appeasement policy , that Great Britain considered Germany's claims against Austria to be in principle justified. The events in Berchtesgaden gave the Austrian National Socialists a great boost.

Schuschnigg realized that his new government partners were pulling the rug from under his feet within a few weeks and were about to take power . In a public speech on February 24, 1938, he invoked Austria's independence: “Until death! Red White Red! Austria!"

The content and tone of Schuschnigg's speech sparked initial irritation among Hitler, which intensified when Schuschnigg announced on March 9th that he would hold a referendum on the independence of Austria on the following Sunday, March 13th .

The question should be whether the people want a “free and German, independent and social, Christian and united Austria” or not. Schuschnigg failed to question the cabinet, as stipulated in the constitution on the occasion of a referendum. The counting of votes should be done by the Fatherland Front alone . The members of the public service should vote in their departments under supervision on the day before the election and hand over their completed ballot papers openly to their superiors. In addition, only ballot papers with the imprint "YES" should be given out in the polling stations, which would have meant a "Yes" to independence. Interior Minister Seyß-Inquart and Minister Glaise-Horstenau immediately explained to their Federal Chancellor that the vote in this form was unconstitutional.

Whether the plebiscite was a “flight forward” by the Austrian Chancellor or a “serious mistake”, Hitler changed his strategy again and set about achieving his goal immediately: he ordered the mobilization of the 8th Army planned for the invasion instructed Seyss-Inquart on March 10th to issue an ultimatum and to mobilize the Austrian party supporters. The Reich government demanded that the referendum be postponed or canceled. Joseph Goebbels noted in his diary:

“Consult with the guide alone until 5am. He thinks the hour has come. Just want to sleep on it for the night. Italy and England won't do anything. Maybe France, but probably not. The risk is not as great as with the occupation of the Rhineland . "

On the following day, March 11, 1938, Hermann Göring took over the direction of preparations for the “Anschluss” of Austria by telephone and telegraph. Ultimately, he demanded Schuschnigg's resignation and the appointment of Seyss-Inquart as Federal Chancellor. Glaise-Horstenau, who had been in Berlin , brought Hitler's ultimatum from there, which Göring also confirmed in telephone calls with Seyss-Inquart and Schuschnigg. Following an instruction from Berlin, the Austrian National Socialists poured into the Federal Chancellery and occupied stairs, corridors and offices. On the afternoon of March 11th, Schuschnigg agreed to cancel the referendum. In the evening Hitler forced his resignation in favor of Seyss-Inquart (Federal President Wilhelm Miklas had previously tried in vain to persuade several non-National Socialists to take over the chancellorship).

Schuschnigg announced his resignation on the radio ( "God save Austria!") And had the Austrian Federal Army tended to withdraw when German troops marched unopposed.

At the same time, the takeover of power by Austrian National Socialists began in Vienna and all the provincial capitals , who hoisted swastika flags on numerous public buildings on the evening of March 11th, long before the invasion of the German armed forces began. The Federal Chancellery in Vienna, where Federal President Miklas also held office, was surrounded by armed men - allegedly for his protection. On March 12, 1938, in many places, on the night of March 11, 1938, appointed Nazi officials were in office.

As a result, Goring, with Hitler's consent, sent a telegram requesting the dispatch of troops from the Reich, which the Reich government then sent itself on behalf of the new Federal Chancellor Seyss-Inquart. The latter was informed of the “urgent request” from the “provisional Austrian government” only afterwards.

Controversy about making decisions

How the decision-making process within the National Socialist polycracy took place in March 1938 is debatable in research:

Goering's biographer Alfred Kube believes that it was primarily due to Goering's initiative that Schuschnigg's plan for a plebiscite was not only thwarted, but the entire neighboring country was annexed. At first Hitler was rather hesitant. This thesis, which goes back to Göring's statements in the Nuremberg trial against the main war criminals , is shared by a large number of historians .

The Heidelberg historian Georg Christoph Berger Waldenegg contradicts this : According to his analysis, Hitler did not have to be “pushed to his luck”: After Schuschnigg's provocative plebiscite proposal, he was so angry that, as Ambassador Henderson learned, the moderates in the leadership of the empire could no longer hold him back.

According to Henning Köhler, too, the initiative for the Anschluss lay with Hitler. He interprets the connection crisis in a functionalist way as an indication of the volatile nature of Nazi foreign policy, which did not proceed according to a pre-determined program, but instead used improvised and pragmatic opportunities from case to case where they came up.

Completion of the connection

invasion

After Hitler had issued the military instructions for the invasion of Austria on March 11, 1938 under the code name " Company Otto ", on March 12, 1938, soldiers of the Wehrmacht and police officers - a total of around 65,000 men, some of them heavily armed - marched into Austria which were often received with spontaneous jubilation by parts of the population. In a German proclamation it was announced that Hitler had decided to liberate his homeland and to come to the aid of the brothers in need. Thus he stood there as the perfecter of the great German longing that many Austrians felt in the interwar period . There was no resistance anywhere, although the chaotic conditions that had caused the hastily improvised preparations for the invasion in many places would have offered the opportunity.

In Vienna, met on March 12 at 4:30 pm at the airport Aspern the realm leader SS Heinrich Himmler , accompanied by SS and police officers in order to take over the Austrian police conduct; he was expected by Ernst Kaltenbrunner and Michael Skubl . With the ringing of bells, Hitler crossed the border at his native Braunau on the afternoon of March 12th and reached Linz four hours later , where he gave a short speech from the balcony of the town hall and declared that he had been commissioned to return his dear home to the Reich. For two days (March 12th and 13th) Seyß-Inquart formed a National Socialist federal government sworn in by Miklas. That same evening, Hitler and Seyss-Inquart met in Linz and agreed to carry out “reunification” immediately without the transition periods planned earlier.

Connection Act

| Basic data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Law on the reunification of Austria with the German Empire |

| Abbreviation: | (unofficial: Anschlussgesetz 1938) |

| Scope: | German Empire , Federal State of Austria (thus: Country of Austria) |

| Legal matter: | International law / constitutional law / constitutional law |

| Reference: | RGBl. I No. 21/1938 (p. 237) |

| Date of law: | March 13, 1938 |

| Date of regulation: | March 16, 1938 (RGBl. I 25/1938, p. 249) |

| Effective date: | March 13, 1938 |

| Expiration date: | May 1, 1945 ([1.] Constitutional Transition Act StGBl. 4/1945) |

| Legal text: | i. d. F. 1938 (alex.onb) |

| Regulation text: | Overview (ns-quellen.at) |

| Please note the note on the applicable legal version ! | |

The law on the reunification of Austria with the German Reich was agreed on the following day, March 13, in the Hotel Weinzinger in Linz by Hitler for the Reich ( RGBl. I 1938, p. 237) and by Seyß-Inquart for Austria. It was passed in accordance with Article III, Paragraph 2 of the Federal Constitutional Act of April 30, 1934 on extraordinary measures in the area of the constitution , the so-called “Enabling Act 1934”, passed by the Dollfuss dictatorship in the second cabinet meeting of the Seyß-Inquart government in Vienna.

Federal President Miklas then resigned because he did not want to certify the so-called reunification law; as head of state for a few minutes Seyss-Inquart carried out the authentication. In the Reich the law came into being on the same day by resolution of the Reich Government. The 13th March 1938 is therefore legally the date of the "Anschluss". As the state of Austria, Austria was now part of the German Empire under international law ; the federal government of Seyß-Inquart continued to function as the Austrian state government under the supervision of the Reich government. After joining the German Reich, Austria was deleted from the list of League members because it was about the fall of a member state .

Mass enthusiasm and terror

On March 15, Hitler announced "the entry of my homeland into the German Reich" on Heldenplatz in Vienna to the cheers of allegedly around 250,000 people. (The exact number of listeners has not been determined. Mostly 250,000 are assumed.) He described Austria as the “oldest Ostmark of the German people” and “the youngest bulwark of the German nation and thus of the German Empire”, but avoided naming Austria. In numerous Viennese companies, the workforce was obliged to take part in this rally as a group. The cheers on Heldenplatz reflected the enthusiastic mood in a large part of the population.

In the first few days after they came to power, the new rulers arrested around 70,000 people, especially in Vienna, with the help of Austrian supporters. These included many politicians and intellectuals from the First Republic and the corporate state, as well as Jews in particular. The terror had already begun before the Wehrmacht marched in: In an "orgy of unparalleled violence" ( Hans Mommsen ), thousands of Jewish institutions and shops were plundered on March 12, and Jews were publicly mistreated and humiliated. Among other things, they were forced to clean the sidewalks of anti-National Socialist slogans in so-called friction sections . This outburst of anti-Semitic hatred was spontaneous and had not been foreseen by any side. A total of over 8,000 Jewish retail stores went into “ Aryan ” ownership or had to close completely. In particular, members of the Austrian NSDAP and their affiliated organizations shamelessly enriched themselves. In April 1939, Gauleiter Josef Bürckel tried in vain to collect an Aryanization levy from them . The Austrian pogrom of March 1938 far surpassed the extent and brutality of the situation in Germany. He gave the anti-Jewish policy in the “Old Reich” a new impetus, which reached a new high point in the same year in the November pogroms .

In Switzerland tens of thousands of refugees arrived, most in transit, while they had the number of refugees from Austria in Switzerland estimated on the eve of the "Anschluss" in 5000th Before crossing the border, after luggage control and body searches, those leaving were only allowed to take 10 marks or 20 schillings with them, Jews also had to hand over valuables.

The retired on March 11 Schuschnigg was first in his official residence in Belvedere placed under house arrest, then for months in Vienna Gestapo -Hauptquartier, the former Hotel Metropole , imprisoned and later like most other prisoners in the Dachau concentration camp deported , but where he significantly was treated better than the other prisoners (Hitler considered keeping him ready for a later planned show trial).

The police, now reporting to Himmler, put an end to any resistance. The borders were sealed off to make it impossible for opponents of the regime to escape. German and Italian troops finally met at the Brenner for friendly ceremonies.

Carl Zuckmayer described the process in 1966 in his autobiography As if it were a piece of me .

Referendum

Hitler had the unification of Austria with the German Reich approved retrospectively in a referendum on April 10, 1938 and combined the decision on the "Anschluss" with a vote of approval for himself. Josef Bürckel was responsible for the organization, who in 1935 was responsible for the National Socialists had organized a very successful referendum in the Saar area .

The question put to the people was:

"Do you agree with the reunification of Austria with the German Reich on March 13, 1938, and do you vote for the list of our Führer Adolf Hitler?"

In the run-up, prominent Austrian personalities had publicly advocated the yes, according to the Viennese Cardinal Theodor Innitzer , who already signed an affirmative “solemn declaration” of the bishops with “and Heil Hitler” on March 18, as well as the president of the evangelical councilor Robert Chew . Former State Chancellor Karl Renner also advised the Neue Wiener Tagblatt on March 13, 1938 to vote yes. Supporters were also the former Federal President Michael Hainisch as well as artists such as Paula Wessely , Paul Hörbiger , Hilde Wagener , Friedl Czepa , Ferdinand Exl , Erwin Kerber , Rolf Jahn, Josef Weinheber and Karl Böhm (“Anyone who does not agree to this act of our leader with a hundred percent yes , does not deserve to bear the honorary name of German ").

In several Austrian cities, meticulously staged appearances by high officials of the NSDAP took place before the vote, such as von Goebbels, Göring, Hess and others. Hitler himself gave a speech on April 9 in the Nordwestbahnhalle in Vienna .

The Nazi propaganda penetrated all areas of life: flags, banners and posters with slogans and a swastika symbol were installed in all the cities where trams, on walls and specially erected poster stands and columns. In Vienna alone there were around 200,000 portraits of Hitler in public places. Even on postmarks one could read: On April 10th to the Führer, your “Yes” .

The press and radio were firmly in the hands of the new rulers, had no other topic than the yes , so that there could be no public votes against. The satirical magazine Kladderadatsch, for example, featured a drawing by Otto von Bismarck on the cover picture on the day of the vote , who paid tribute to him with a ballot paper entitled “The Creator of Greater Germany”. Around eight percent of those actually eligible to vote were excluded from the vote: around 200,000 Jews , around 177,000 “ mixed race ” and those previously arrested for political or racial reasons.

During the vote itself, many voters publicly ticked yes in front of the election workers and not in the voting booth , in order to avoid suspicion of having voted against the “Anschluss” and to avoid being exposed to possible reprisals as “opponents of the system” . Voting secrecy was practically not observed, there was usually no alternative to an open vote without exposing himself and his family to possible political persecution. In addition, the National Socialists spread the word that voting secrecy was not guaranteed and that secret controls were taking place. People who were critical of the referendum or who recommended a “no” were reported and faced harsh penalties.

The cruise ship Wilhelm Gustloff was already used on April 8th to take 2,000 Germans and Austrians living in England on board and then on April 10th, three miles off the coast of England, to give them the opportunity to vote in the "floating polling station".

On the evening of April 10th, Gauleiter Josef Bürckel reported the result of the vote to Berlin from the Wiener Konzerthaus . According to official information, 99.73% of those who voted had approved. In the previous area of the Reich, now known as the Old Reich , supposedly 99.08% voted for the "Anschluss". According to the statistics of the German Reich, there were 4.474 million voters in Austria, the turnout in Austria was 99.71%, in the old Reich 99.59%.

The attitude of the Austrian population towards an Anschluss and the motives responsible for this are the subject of a historical and political debate. Numbers about how many Austrians were for the “Anschluss” cannot be approximated either. Firstly, there are no relevant surveys, secondly, Schuschnigg canceled his referendum and thirdly, the referendum held on April 10th cannot be described as free. The German historian Hans-Ulrich Thamer puts the result of the referendum, which “surpassed all previous totalitarian dream brands”, in a context of jubilation, approval and widespread relief that fighting could be avoided. The political scientist Otmar Jung quotes the assessment of the Germany reports of the Sopade , according to which about 80% would have voted for the “Anschluss” even in a free vote, which is not, however, synonymous with a commitment to National Socialism. The social historian Hans-Ulrich Wehler also suspects that the vote would not have turned out significantly different if the conditions were free and under international supervision. Above all, Gordon Brook-Shepherd was convinced that a completely free vote would have resulted in a majority in favor. The 40% or so of the population who stood between opponents and supporters, who would have voted for Austria in the vote planned by Schuschnigg, would have been decisive. The British historian Richard J. Evans , on the other hand, attributes the result to the “massive manipulation and intimidation” that took place before the vote: According to reports by the Gestapo, for example, in Vienna, for example, only a third of the population should not be nearly one hundred percent for the unification of Austria with the German Empire.

Effects

The “Anschluss” was seen as another personal success of Hitler, which gave the leader myth renewed nourishment and further legitimized Hitler's charismatic rule . Hitler's popularity now approached the enthusiasm that Otto von Bismarck had enjoyed after the unification of the empire , which seemed to be overshadowed by the success of having all German-speaking people gathered in one state. The Sopade reports on Germany reported that many Germans had now come to believe that “the Führer can do everything he wants”. After the Anschluss, even Renner praised the “unprecedented perseverance and drive of the German Reich leadership” in the manuscript The Establishment of the Republic of German Austria, the Anschluss and the Sudeten German Question, which was written until 1939 and was published only later, or referred to the Anschluss of Austria and the Sudeten German regions as also shows the actions of Hitler and his government in this context very positively.

Germany immediately made use of Austria's gold and foreign exchange reserves, which had reached considerable stocks due to the deflationary economic policy of the governments in the 1930s; they have now been transferred to the old Reich, which has poor foreign exchange. More than 2.7 billion schillings in gold and foreign exchange came under Nazi control.

In Austria, renamed Ostmark in 1939 , the NSDAP was very popular. In 1943 the number of members reached its peak: almost 700,000 Austrians and thus more than ten percent of the population belonged to it. The distribution was very different from region to region: In Tyrol a peak value of 15% was reached, in the economically poor Burgenland , which is divided into Lower Austria and Styria , it was only 6%.

After the war, 536,000 people were required to register for denazification . For comparison: In West Germany around 13 million National Socialists out of a total population of 58 million people, i.e. significantly more in percentage terms, were registered for denazification. In June 1938, the Gestapo estimated that 30% of Austrians were supporters of National Socialism, even if not only for ideational reasons. According to the Gestapo, however, 30 to 40% of Austrians were open or hidden opponents.

International reactions

The Anschluss violated international law: both the Treaty of Versailles , which the victorious powers of World War I had concluded with the German Reich, and the Treaty of Saint-Germain between them and Austria explicitly forbade an annexation of Austria to the Reich. This prohibition was confirmed by the Republic of Austria in the Geneva Protocols of 1922 . With the Little Entente between Romania , Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, France had created its own security architecture in East Central Europe in the 1920s , which also served the purpose of preventing a Anschluss. Nevertheless, both France and Great Britain accepted the connection, which was contrary to international law. The ambassadors of both countries, Nevile Henderson and André François-Poncet , protested against the German approach in Berlin on the evening of March 12 in only two separate, albeit parallel, demarches .

During the crisis that preceded the Anschluss, the French Foreign Minister Yvon Delbos had a proposal in London on February 11, 1938, to clarify in good time and together in Berlin that “every act of violence aimed at calling into question the territorial status quo in Central Europe to face the resolute resistance of the Western powers ”. Nothing came of this action when the British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden resigned a few days later . His successor, Lord Halifax, was a staunch advocate of the appeasement policy, who believed that if Germany were only allowed to enforce its legitimate interests - after all, the ban on affiliation violated the peoples' right to self-determination - then it could then become a reliable partner in one stable international system. For similar considerations, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain concluded the German-British naval agreement with Germany in 1935 , which partially legalized the illegal German rearmament. Thus Delbos was left without a partner in the follow-up crisis. In addition, the Popular Front government under Camille Chautemps , of which he was a member, resigned on March 10th: at the time of the annexation, France had no effective government.

In addition, the security architecture that France had built since the 1920s made military intervention impossible. The Locarno Treaty of 1925 guaranteed the Franco-German border, so France would have been guilty of a breach of treaty in the event of a military intervention in the Rhineland. For a long time, his most important ally, Poland , signed a non-aggression pact with Germany in 1934 - so no military pressure was to be expected from this side. In this respect there was nothing left but to accept the German fait accompli . For Chamberlain, the question on the agenda was “how we can prevent similar events from occurring in Czechoslovakia”.

The London Times wrote that after all, Scotland also joined England 200 years ago . Italy, which was still the guardian of Austrian sovereignty in 1934 , did not protest at all: Hitler had informed Mussolini by letter on March 11th of his "decision to restore order and calm in my homeland", and in doing so he had drastically mapped Austria's domestic political situation. Although the letter was only written after the marching orders for the Wehrmacht had been issued, Mussolini was able to feel that he had been informed in advance, as had been promised in the Axis Alliance. Berger Waldenegg speculates counterfactually that just a sharp protest note from Italy could have prevented the Anschluss: Then the Western powers would have been more aggressive and Hitler might have backed down. But Italy tolerated the "Anschluss".

On March 18, 1938, the Soviet government called on the United States of America , Great Britain and France to take collective action against Germany, but to no avail. In September 1938 Josef Stalin tried again, this time within the framework of the League of Nations, to come to a concerted approach, but this time too without success. The USA and France did not de jure accept the Anschluss , but they did de facto. Great Britain raised a formal protest, but finally recognized the Anschluss de jure.

In Czechoslovakia the conclusion from the Anschluss of Austria was that they were preparing for a military conflict: the government in Prague did not want to accept the absorption of its own territory without a fight .

Switzerland responded with the proclamation of the Federal Council and the parliamentary groups regarding the neutrality of Switzerland, which was fully approved in the National Council across all party lines.

Mexico lodged a protest with the League of Nations by sending a diplomatic note "against foreign aggression against Austria" and its Foreign Minister Eduardo Hay called for a council meeting to be convened. In honor of the Mexican protest note, the Erzherzog-Karl-Platz in Vienna was renamed Mexikoplatz on June 27, 1956 . A memorial stone with the following inscription has stood there since 1985: “In March 1938, Mexico was the only country that lodged an official protest against the violent annexation of Austria to the National Socialist German Reich in front of the League of Nations. To commemorate this act, the City of Vienna named this square Mexikoplatz. ”Another monument donated in 1988 is in Mexico City .

Incorporation into the German Empire

With the exception of Michael Skubl - he resigned from his position on March 13 - the Seyss-Inquart government continued to operate as the state government of Austria in the Third Reich under the supervision of the Reich government. It was headed by Seyss-Inquart, who was appointed Reich Governor on March 15 .

In April 1938, Josef Bürckel was appointed “Reich Commissioner for the Reunification of Austria with the German Reich”. He was followed by Baldur von Schirach in 1940 .

The Austrians became citizens of the German Reich by ordinance of July 3, 1938 and now shared the National Socialist history of the Reich until its historic fall in 1945, with quite a few Austrians actively participating in the National Socialist policy of aggression and extermination. In Nazi propaganda , the state was now referred to as the Greater German Reich ; This designation became official by a decree of June 26, 1943. Adjustments have now been made in numerous everyday details. For example, the coins of two and one groschen on the part of the Reichsbank were equated with coins of one and two Reichspfennig and were considered a means of payment throughout the entire Reich .

On May 1, 1939, the so-called Ostmarkgesetz was passed, with which the powers of the Reich governor were to be transferred to the Reich Commissioner . The implementation of this law was completed on March 31, 1940. At the same time as the takeover of power, Vienna was deprived of power as the capital: It lost its metropolitan position and relations between the federal states and districts with Vienna were cut off; The capital was exclusively Berlin. The state structures remained (apart from the division of Burgenland and the unification of Vorarlberg with Tyrol) as structures of the Reichsgaue .

The area of the former federal state of Austria was divided into the Reichsgaue Carinthia, Lower Danube , Upper Danube , Salzburg, Styria, Tyrol and Vienna. Hitler initially replaced the unloved name Austria (in his words a “freak of history”) with Ostmark , a translation for marcha orientalis that was widespread from the 19th century and was also used for those eastern areas of Germany that were partly inhabited by Poles became (→ Deutscher Ostmarkenverein ). During the time of National Socialist rule there was also a Gau Bayerische Ostmark .

As of 1942, the name Ostmark was replaced by the Danube and Alpenreichsgaue . Karl Vocelka , Professor of Austrian History at the University of Vienna , saw this as a further step in the endeavors of the National Socialist rulers to erase any evidence of Austria's (historical) independence . Another possible reason for the renaming is that in the course of the conquests of the German Empire in Eastern Europe, the former Austria was no longer an “eastern border march”.

Cancellation of the "connection"

On September 9, 1942, the British Foreign Minister Eden declared before the House of Commons that he would no longer recognize the annexation of Austria to the German Reich (which had been accepted in 1938) and that he would not feel bound by any changes in post-war agreements that had occurred since 1938. Nevertheless, Austria could not be treated like any other country under German occupation. This shows the vague attitude of the British towards Austria at the time.

Austria's membership of the German Reich came to an end in April / May 1945 with the victory of the Allied Soviet Union, USA, Great Britain and France in World War II. The Red Army won in the " Vienna Offensive " beginning of April 1945 a victim they defeated Wehrmacht, Waffen-SS and Volkssturm so that in Vienna as early as mid April 1945 democratic parties could be re-established and on April 27, 1945, when Eastern Austria largely on the Soviet Union was occupied, the state government chaired by Karl Renner could begin to officiate. In western and southern Austria , control passed to units of the western allies at the beginning of May 1945, mostly without major fighting. Innsbruck was the only major city in the Third Reich not liberated from the victorious powers, but from Austrian resistance fighters.

The three parties ÖVP , SPÖ and KPÖ issued the Austrian Declaration of Independence in Vienna on April 27, 1945 , which deemed the “Anschluss” null and void. It was included as a proclamation on the independence of Austria as No. 1 in the State Law Gazette for the Republic of Austria published on May 1, 1945 and is considered the founding document of the Second Republic .

The Austrian State Treaty of 1955 forbids political or economic unification between Austria and Germany ( connection ban ).

Legal issues

The “Anschluss” in 1938 was not a voluntary accession of the Republic of Austria to the German Reich , but took place illegally and under threat of violence. In the Moscow declaration of the allied states Great Britain, the USA and the Soviet Union of November 1, 1943, their foreign ministers declared it null and void . At this conference they also used the expression " Germany within the borders of December 31, 1937 " for the first time to make it clear that they qualified all subsequent territorial expansions of the German Reich as not in accordance with international law. In the proclamation on the independence of Austria signed on April 27, 1945 and announced on May 1, 1945, and the declaration of independence contained therein , the Anschluss was described as "dismissed and forced", "forced" and "abused" and thus "null and void." " explained. In the Nuremberg Trial in 1946, the circumstances that led to the Anschluss were not counted as a war of aggression , but as a planned act of aggression that was carried out with the intention of making later wars of aggression possible. There is therefore unanimous agreement about the illegal character of the connection and thus its nullity ex tunc .

Its legal character is, however, controversial. The Moscow Declaration of 1943 exhibits a certain “contradiction and inaccuracy” in that it described the connection as “ annexation ” on the one hand , while the German translation used the term “ occupation ”. The description of the “Anschluss” as annexation (contrary to international law) can often be found in the specialist literature, but in 2003 an Austrian commission of historians rated it as a unique “borderline case between annexation, merger and occupation”.

Closely related to this is the question of the existence of Austria in the years 1938 to 1945. Proponents of the annexation theory assume that the Republic of Austria perished as a result of the Anschluss, while supporters of the occupation theory assume that they as a subject of international law also in the years 1938 to 1945 continued. The Polish international lawyer Krystyna Marek consistently draws from the legal principle that no new law can arise from injustice ( ex iniuria ius non oritur ) that the Austrian state was not wiped out by the injustice of the National Socialists, which in her result leads to continuity of the state leads. The continuity thesis also prevailed in Austrian jurisprudence and the highest court rulings in Austria after 1945: The Republic of Austria was therefore not annexed in 1938, but only occupied and continued to exist. This assumption became "quasi the official Austrian state doctrine".

German courts, on the other hand, assumed that the connection had taken place with the consent of the Austrian people . Since there was no significant resistance to the Anschluss, Austria's statehood was deemed to have expired in the years 1938–1945. The state "restored" in 1945 was "in truth rebuilt". The Austrian legal opinion that the republic was "only temporarily occupied and its state authority suspended" is called fiction . The legal historian Rudolf Hoke states that “the legal nature of the 'Anschluss' by many contemporaries, also in Austria, and by most foreign governments” was seen as the downfall of the Austrian state, after which it needed to be re-established in 1945 : the foreign governments had theirs Expressed their stance by immediately converting their Vienna diplomatic missions into consulates general . The legal scholar Oliver Dörr also doubts the continuity thesis, which represents a “suppression of real historical events”. Nevertheless, today there is largely a consensus on a fictitious identity of Austria after 1945 with the Austrian state before 1938, that it is one of the "established beliefs of the modern world of states". Because the “Anschluss” in 1938 initially had all the characteristics of an incorporation under international law , despite the “reestablishment thesis” .

Israel sent a delegate to Austria as early as 1948. Consular relations were established in 1950 and upgraded to full diplomatic relations in the following months. Negotiations about “reparation” were never conducted with Austria. In 1952, Israel officially renounced demands on the Republic of Austria, thereby recognizing that Austria had fallen victim to the Nazi Reich's policy of aggression.

Victim thesis

The initially euphoric mood in the population gave way to widespread disillusionment in the course of the war. After the war an independent Austria was restored. Nevertheless, the events of 1938 were taboo for large sections of the population. The myth of Austria as the “first victim” of National Socialist Germany was widely accepted and the official position of the Republic of Austria. Among other things, it was based on the Moscow Declaration of 1943. In it the Allies had declared:

"The governments of the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and the United States of America are of the same opinion that Austria, the first free country to fall victim to Hitler's typical aggressive policy, should be liberated from German rule."

On the basis of this myth, the Republic of Austria refused for decades to officially apologize to the victims of National Socialism and to seek compensation, especially for the Jewish Austrians. This attitude was justified by the fact that Austria no longer existed as a subject of international law with the execution of the “Anschluss” and therefore could not be called to account. Its population was also exculpated from any guilt, for example officials meticulously avoiding the word reparation in their drafts and pleadings, which implied that there was actually something to be made up for.

It was not until the controversial Waldheim affair in 1986 that the critical illumination of the past of the role of the Austrians during the “Anschluss” and the Second World War began in earnest. The election of Waldheim sparked a great debate in Austria; In 1993 the then Chancellor Franz Vranitzky apologized in a speech to the Knesset for the role played by the Austrians involved in the Nazi crimes and asked for forgiveness. In response to massive pressure from the US government, the National Fund, among other things, was set up to symbolically compensate the persecuted and to tackle restitution . Textbooks and lessons were changed to identify the extent to which Austrians had helped and availed of the “Anschluss” while other Austrians became victims. The Memorial Service for Young Citizens, set up in 1992, is a network for memorials for the victims of National Socialism and for relevant museums that want to help their archives and libraries.

For the spelling of the term in quotation marks

When the "annexation" of Austria to the German Reich in 1938 is mentioned, historians mostly put the term under quotation marks . Florian Wenninger sees it as an expression of distancing himself from a term that was taken over and reloaded by National Socialist propaganda . The quotation marks are intended to mark the historical distinction to the previous follow-up efforts.

For Oliver Rathkolb , the quotation marks indicate that the term is now used in many different ways. If the events in March 1938 were described by the National Socialists as "voluntary Anschluss", the use of the term in 1945 changed into the opposite, with "Anschluss" meant an occupation in line with the victim thesis . It was not until the 1980s and the debates in the context of the Waldheim affair, in which the complicity of many Austrians was discussed, that a more differentiated view of what was going on at the time developed.

The use of the quotes, however, is not a shared consensus on all sides. Kurt Bauer, for example, considers it an expression of political correctness that has become naturalized. For reasons of readability, he does not use quotation marks in his texts; the historical location of the term results from the context.

reception

In 1989 Hugo Portisch and Sepp Riff designed the documentary film series Austria I for Austrian Broadcasting Corporation , which in twelve episodes depicts the history and sequence of the “Anschluss”.

The "connection" of Austria to the German Reich is documented in the Army History Museum , a federal museum in Vienna, in room VII - "Republic and Dictatorship". Exhibited are u. a. , the National Socialist advertising pamphlets, ballots and objects the acquisition of the Armed Forces illustrate the Wehrmacht. However, after an evaluation by an expert commission in 2020, the exhibition was sharply criticized: The exhibits were inadequately contextualized, which would create problematic room for interpretation.

The City of Vienna commemorates the events of 1938 and after in its Vienna Museum and in the Jewish Museum Vienna . In 1988, at the instigation of the then mayor Helmut Zilk , the memorial against war and fascism , designed by Alfred Hrdlicka , was unveiled on Vienna's Albertinaplatz in the city center . To commemorate the horrors of the Vienna Gestapo headquarters there is a memorial room at its former location in Salztorgasse . In 2000 the city administration unveiled the memorial designed by Rachel Whiteread for the Austrian Jewish victims of the Shoah on Vienna's Judenplatz .

On October 24, 2014, Federal President Heinz Fischer and Mayor Michael Häupl presented the deserters' monument in Vienna . The monument designed by Olaf Nicolai was erected on Ballhausplatz opposite the Federal Chancellery on behalf of the Vienna city administration . It serves to commemorate the victims of Nazi military justice .

In many Austrian communities, those who fell in World War II are commemorated on the same memorial as those who fell in World War I; the involvement in the National Socialist war of aggression and annihilation that began after the “Anschluss” is mostly not mentioned. In all federal states of Austria there are also memorial sites on the murderous consequences of the “Anschluss” .

The author Erich Kästner addressed the "Anschluss" and the following Austrian victim myth in the post-war period in a mocking song in which he had the National Allegory Austria sing the following:

- I gave myself up, but only because I had to.

- I only screamed out of fear and not out of love and lust.

- And that Hitler was a Nazi - I didn't know that!

Artistic and literary processing

- 1938 to 1945

- Franz Schmidt / Oskar Dietrich / Robert Wagner : German resurrection. A festive song ( Universal Edition , world premiere: Wiener Musikverein 1940)

- after 1945

- Thomas Bernhard : Heldenplatz . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-518-01997-X .

- Ernst Jandl : Vienna: Heldenplatz . In: Laut and Luise . Walter, Olten / Freiburg im Breisgau 1966.

See also

- Medal in memory of March 13, 1938 ("Ostmark Medal")

literature

- Documentation archive of the Austrian resistance (ed.): "Anschluss" 1938. A documentation . Österreichischer Bundesverlag, Vienna 1988, ISBN 3-215-06824-9 .

- Gerhard Botz : Vienna from the “Anschluss” to the war. National Socialist takeover and political-social transformation using the example of the City of Vienna in 1938/39 . 2nd Edition. Jugend und Volk, Vienna / Munich 1978, ISBN 3-7141-6544-4 .

- Georg Christoph Berger Waldenegg : Hitler, Goering, Mussolini and the “Anschluss” of Austria to the German Reich . In: VfZ . Volume 51, No. 2 . Oldenbourg, 2003, ISSN 0042-5702 , p. 147–182 ( ifz-muenchen.de [PDF; 8.0 MB ; accessed on July 23, 2013]).

- Bruce F. Pauley : The Road to National Socialism. Origins and development in Austria . Edition revised and supplemented by the author, German translation by Gertraud and Peter Broucek , Bundesverlag, Vienna 1988, ISBN 3-215-06875-3 .

- Nikolaus von Preradovich : Wilhelmstrasse and the Anschluss of Austria, 1918–1933 (= European university publications . Series 3: History and its auxiliary sciences , Volume 3). Lang, Bern [u. a.] 1971.

- Erwin A. Schmidl : The “Anschluss” of Austria. The German invasion in March 1938. 3., verb. Edition, Bernard and Graefe, Bonn 1994, ISBN 3-7637-5936-0 .

- Alkuin Volker Schachenmayr (Ed.): The Anschluss in March 1938 and the consequences for churches and monasteries in Austria. Research report of the working conference of the EUCist in Heiligenkreuz from 7./8. March 2008 . Be & Be-Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-9519898-5-3 .

- Heidemarie Uhl : Between Reconciliation and Disturbance. A controversy about Austria's historical identity fifty years after the “Anschluss”. Böhlau, Vienna 1992, ISBN 3-205-05419-9 (= Böhlaus Zeitgeschichtliche Bibliothek , Volume 17, also: Dissertation , Univ. Graz, 1988 - limited preview ).

Web links

- Entry on the Anschluss of Austria in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- The way to the "Anschluss" (documentation archive of the Austrian resistance)

- Federal constitutional law on the reunification of Austria with the German Reich of March 13, 1938 ( Federal Law Gazette No. 75/1938)

- Ordinance on German citizenship in Austria of July 3, 1938 (RGBl. 1938 I, p. 790 f .; amended RGBl. 1939 I, p. 1072)

- Connection plans for Austria and Austrian federal states after 1918 in the Bavarian Historical Lexicon

- German Historical Museum : The "Anschluss" of Austria

- Hour of Salvation , The Time of March 13, 2008 No. 12

- Adolf and the Patriots , Die Zeit of March 13, 2008 No. 12

- British literature review on connection (PDF; 54 kB)

- Audio tracks - audio guide with recordings of contemporary witnesses for connection

- Propaganda of the “Anschluss” - online exhibition with historical original sounds in the “Akustische Chronik” of the Austrian media library

- Peter Mayr, Conrad Seidl: Federal President Fischer: “12. March 1938 a day of shame ” , derStandard.at , March 12, 2013

Individual evidence

- ↑ Federal Law Gazette No. 75/1938 , published again in the Law Gazette for the State of Austria No. 1/1938 .

- ^ Friedrich Heer : The Struggle for Austrian Identity , Vienna 2001, ISBN 3-205-99333-0 , u. a. Pp. 21, 29, chap. 3.

- ↑ Margarethe Haydter, Johann Mayr: Regional connections between main areas of resistance at the time of the Counter Reformation and the July battles in 1934 in Upper Austria. In: Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 11/12, 1982, pp. 392–407.

- ↑ Walter Rauscher : The founding of the republic in 1918 and 1945. In: Klaus Koch, Walter Rauscher, Arnold Suppan, Elisabeth Vyslonzil (ed.): Foreign policy documents of the Republic of Austria 1918–1938 (ADÖ), special volume: From Saint-Germain to the Belvedere. Austria and Europe 1919–1955 , Verlag für Geschichte und Politik, Wien / Oldenbourg, Munich 2007, ISBN 3-486-58378-6 , pp. 9–24, here p. 15.

- ^ So Rudolf Hoke , Austrian and German legal history , 2., verb. Ed., Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 1996, ISBN 3-205-98179-0 , p. 460 .

- ↑ State Law Gazette No. 5/1918 (= p. 4)

- ↑ Hellwig Valentin : From regional particularism to the federal state . In: Stefan Karner , Lorenz Mikoletzky (Ed.): Austria. 90 Years Republic , Innsbruck 2008, ISBN 978-3-7065-4664-5 , p. 35 ff.

- ^ Already previously stated on the Austrian side in a protocol of February 28, 1919.

- ^ Horst Möller : Austria and its neighbors: Germany (1919–1955). In: Klaus Koch, Walter Rauscher, Arnold Suppan, Elisabeth Vyslonzil (eds.): Foreign policy documents of the Republic of Austria 1918–1938: From Saint-Germain to the Belvedere. Austria and Europe 1919–1955 , Vienna 2007, pp. 158–171, here p. 161 f.

- ^ Call of the Communist Party of Austria to participate in a "Voters' Assembly" ( poster ).

- ^ Social Democratic Workers' Party in German Austria: The Linz Program , November 3, 1926.

- ^ Documentation archive of the Austrian resistance (ed.): Resistance and persecution in Vienna 1934–1945. A documentation , Vienna 1984, vol. 1, p. 105, quoted from: Rudolf G. Ardelt: Die Sozialdemokratie und der “Anschluss” , in: Documentation archive […]: “Anschluss” 1938. A documentation , Österreichischer Bundesverlag, Vienna 1988 , P. 65.

- ^ Resistance , p. 186, quoted from ibid.

- ↑ Georg Christoph Berger Waldenegg: Hitler, Göring, Mussolini and the "Anschluss" of Austria to the German Reich. In: Vierteljahrshefte zur Zeitgeschichte 51, issue 2 (2003), pp. 164–168 ( PDF ; 7.98 MB, accessed on July 21, 2014).

- ↑ Klaus Hildebrand : The Third Reich. Oldenbourg, Munich 2009, p. 37.

- ↑ Cf. Erwin A. Schmidl: “Anschluss” 1938 - a look back after 75 years. In: Stefan Karner, Alexander O. Tschubarjan (Hrsg.): The Moscow Declaration 1943. “Restore Austria”. Böhlau, Vienna [a. a.] 2015, pp. 134–161, here p. 158 .

- ^ Henning Köhler: Germany on the way to itself. A history of the century. Hohenheim-Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, p. 344.

- ↑ a b Ardelt in: “Anschluss” 1938 , p. 67.

- ↑ a b Georg Christoph Berger Waldenegg: Hitler, Göring, Mussolini and the "Anschluss" of Austria to the German Reich. In: Vierteljahrshefte zur Zeitgeschichte 51, issue 2 (2003), p. 162 ( PDF ; 7.98 MB, accessed on July 21, 2014).

- ^ Norbert Schausberger : On the prehistory of the annexation of Austria. In: Heinz Arnberger (ed.): “Anschluss” 1938. A documentation. Österreichischer Bundesverlag, Vienna 1988, p. 15.

- ^ Henning Köhler: Germany on the way to itself. A history of the century. Hohenheim-Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, p. 344.

- ^ Joseph Goebbels: Diaries 1924–1945. Volume 3: 1935-1939. Edited by Ralf Georg Reuth . Piper, Munich 1999, p. 1211.

- ↑ Last radio address by the Austrian Chancellor Schuschnigg on March 11, 1938. (Audio, 2:51 min) Austrian Media Library , March 11, 1938, accessed on March 30, 2018 (with a declaration of non-violence in the event of a German invasion).

- ^ Alfred Kube: Pour le mérite and swastika. Hermann Göring in the Third Reich. Oldenbourg, Munich 1986, p. 1 u. ö.

- ↑ Georg Christoph Berger Waldenegg: Hitler, Göring, Mussolini and the "Anschluss" of Austria to the German Reich. In: Vierteljahrshefte zur Zeitgeschichte 51, issue 2 (2003), p. 149 ff. ( PDF ; 7.98 MB, accessed on July 21, 2014).

- ↑ Georg Christoph Berger Waldenegg: Hitler, Göring, Mussolini and the "Anschluss" of Austria to the German Reich. In: Vierteljahrshefte zur Zeitgeschichte 51, issue 2 (2003), pp. 160–163 ( PDF ; 7.98 MB, accessed on July 21, 2014).

- ^ Henning Köhler: Germany on the way to itself. A history of the century. Hohenheim-Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, p. 344.

- ^ Gustav Spann: Anschluss of Austria . In: Wolfgang Benz , Hermann Graml and Hermann Weiß (eds.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, p. 363.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949 , CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 651.

- ^ Henning Köhler: Germany on the way to itself. A history of the century . Hohenheim-Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, p. 344.

- ↑ Already stated in the proclamation of April 27, 1945 about the independence of Austria (StGBl. 1/1945): "the democratic republic of Austria is restored and to be re-established in the spirit of the constitution 1920/29 " (Art. I)

- ↑ BGBl. I, No. 255/1934 ; see. Otmar Jung, plebiscite and dictatorship: the referendums of the National Socialists. The cases “Leaving the League of Nations” (1933), “Head of State” (1934) and “Anschluss Österreichs” (1938) , Tübingen 1995, p. 115 ; Thomas Olechowski , Legal History. Introduction to the historical foundations of law. 3rd edition, facultas.wuv, Vienna 2010, p. 109 .

- ↑ Eckart Klein / Stefanie Schmahl, in: Graf Vitzthum , Völkerrecht , 5th edition 2010, p. 298 .

- ↑ See also with further references Angela Hermann: Der Weg in den Krieg 1938/39. Source-critical studies on the diaries of Joseph Goebbels. Oldenbourg, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-486-70513-3 , p. 109, note 238.

- ^ Gustav Spann: Anschluss of Austria . In: Wolfgang Benz, Hermann Graml and Hermann Weiß (eds.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, p. 363; Hans Mommsen: The Nazi Regime and the Extinction of Judaism in Europe. Wallstein, Göttingen 2014, p. 89 f.

- ↑ Switzerland and the refugees at the time of National Socialism , Independent Expert Commission Switzerland - Second World War, p. 77.

- ^ A b Richard J. Evans: The Third Reich. Vol. II / 2: Dictatorship . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2006, p. 793.

- ↑ The text of the ballot paper of the Federal Government had been as determined by the March 15, 1938 followed by the Regulation: "confess You have as our leader Adolf Hitler and thus the completed on March 13, 1938 reunion of Austria with the German Reich?" ( Ballot in the annex in the legal gazette for the state of Austria to No. 2/1938 ).

- ↑ letters claiming the Catholic bishops of Austria to the "German Reich" in advance of the referendum on 10 April 1938 of 18 March 1938 ÖNB ÖGZ S56 / 57th

- ↑ The Church, too, is committed to Greater Germany! In: Wiener Bilder, April 3, 1938, p. 17.

- ^ Ernst Hanisch : Austrian History 1890-1990. The long shadow of the state. Austrian social history in the 20th century. Ueberreuter, Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-8000-3520-0 , p. 345 ff .; Siegfried Nasko, Johannes Reichl: Karl Renner. Between the Union and Europe . Holzhausen, Vienna 2000, p. 54 ff.

- ^ Viennese artists on April 10th. In: Neues Wiener Journal , April 7, 1938, p. 13 (online at ANNO ).

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Thamer : Seduction and violence. Germany 1933–1945. Siedler, Berlin 1994, p. 577.

- ^ Wilhelm J. Wagner: The large picture atlas on the history of Austria . Kremayr & Scheriau, 1995, ISBN 3-218-00590-6 (chapter "Heim ins Reich").

- ↑ Sandra Paweronschitz: Between Claim and Adaptation. Journalists and the Concordia press club in the Third Reich. Ed. Steinbauer, Vienna 2006, ISBN 978-3-902494-19-1 , p. 21; Gabriele Holzer : Neighbors friends. Austria Germany. A relationship. Kremayr & Scheriau, Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-218-00606-6 , p. 84.

- ^ Leopold Rosenmayr : Overwhelming 1938. Early experience, late interpretation. A sociologist's review of his own childhood and early adolescence. Böhlau, Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-205-77751-9 , p. 322.

- ^ Gerhard Botz : National Socialism in Vienna. Seizure of power and securing rule 1938/39. 3rd, change Aufl., Obermayer, Buchloe 1988, ISBN 3-9800919-5-3 , p. 182.

- ↑ Announcements of the Documentation Archive of the Austrian Resistance, No. 236, May 2018, p. 7 ff. The Documentation Archive of the Austrian Resistance has put a lot of information about the referendum (ballot papers, propaganda posters, police reports, etc.) online, see Nazi "referendum" , April 10, 1938. Propaganda and fault lines - From the archive .

- ↑ London Polling Station: Menus for April 9th, April 10th, and April 11th, 1938 , The Wilhelm Gustloff Museum, accessed December 4, 2015.

- ↑ Audio document (Josef Bürckel) from April 10, 1938 on YouTube , accessed on February 18, 2017.

- ^ Dolf Sternberger, Bernhard Vogel, Dieter Nohlen: The election of parliaments and other state organs. Volume 1 / Halbband 1, 1969, ISBN 978-3-11-001156-2 , p. 365, table A 19.

- ↑ Otmar Jung: Plebiscite and dictatorship: the referendums of the National Socialists. The cases "Leaving the League of Nations" (1933), "Head of State" (1934) and "Anschluss Österreichs" (1938) (= contributions to the legal history of the 20th century 13). Mohr, Tübingen 1995, ISBN 3-16-146491-5 , p. 119 ff.

- ↑ Georg Christoph Berger Waldenegg: The great taboo! Historian controversies in Austria after 1945 about the national past. In: eForum ZeitGeschichte 1/2002 .

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Thamer: Seduction and violence: Germany 1933-1945. Siedler, Berlin 1994, p. 578.

- ↑ Otmar Jung: Plebiscite and dictatorship: the referendums of the National Socialists. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1995, p. 122.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949. Beck, Munich 2003, p. 622.

- ↑ Paul Schneeberger: The difficult handling of the "connection". The reception in historical representations 1946–1995. Studien Verlag, Innsbruck / Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-7065-1497-4 , p. 385.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949 , CH Beck, Munich 2003, pp. 622, 651 (here the quote) and 675.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Ernst Hanisch, The Long Shadow of the State (1994), p. 347; Siegfried Nasko, Johannes Reichl, Karl Renner. Between connection and Europe (2000), p. 66 ff.

- ^ Manfred Jochum: The First Republic in documents and pictures . Wilhelm Braumüller Universitäts-Verlagbuchhandlung, Vienna 1983, p. 247.

- ↑ Ernst Hanisch: The long shadow of the state. Ueberreuter, Vienna 1994, p. 370.