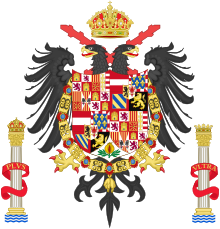

Charles V (HRR)

Charles V ( Spanish Carlos I , French Charles Quint ; born February 24, 1500 in the Prinzenhof , Ghent , Burgundian Netherlands ; † September 21, 1558 in Cuacos de Yuste, Spain ) was a member of the Habsburg dynasty and Holy Roman Emperor .

After the early death of his father Philip I of Castile , Charles was sovereign of the Burgundian Netherlands , consisting of eleven duchies and counties, and from 1516 as Carlos I, the first king of Spain , more precisely of Castile, León and Aragón in personal union . In 1519 he inherited the Archduchy of Austria and was elected Roman-German King as Charles V , after his coronation in 1520 he (like his uncrowned grandfather Maximilian I and his future successors) initially bore the title of “elected Holy Roman Emperor Rich ”. In 1520 he was crowned Roman-German king in the imperial cathedral in Aachen by the Archbishop of Cologne, Hermann V von Wied . In 1530 he was the last Roman-German king to be crowned emperor by Pope Clement VII and is thus after Friedrich III. the second and last Habsburg to be crowned by a Pope.

Karl pursued the imperial idea of the universal monarchy , according to which the emperor had priority over all kings. He saw himself as a peacekeeper in Europe, protector of the West from the expansion of the Ottoman Empire under Suleyman I and as a defender and innovator of the Roman Catholic Church . In order to be able to enforce his idea of hegemonic rule, he waged numerous wars against the French King Francis I ( Italian Wars ). In doing so, Charles was able to rely financially on his colonial possessions in America ( Viceroyalty New Spain , Viceroyalty Peru ), but could not achieve his intended goal of permanently weakening France, which was temporarily allied with the Ottomans .

In the Holy Roman Empire, Charles V sought in vain to sustainably strengthen the monarch's power over the imperial estates . Due to the Reformation that began in 1517 , which was partly supported by the estates, and the frequent absence of Charles due to the war, he was unable to prevent the spread of the Reformation movement. At times he tried to prevent the threatening denominational division of the empire by convening the Council of Trent (1545 to 1563), which however did not lead to the reconciliation of the religious parties, but instead became the starting point of the Catholic Counter-Reformation after Charles's death . After the failure of his efforts to find a compromise with the Protestants , Karl tried to dictate a solution to the religious conflict with the Augsburg Interim in the course of the Schmalkaldic War he won in 1548 . As a result of the uprising of the princes and the related French invasion , he was forced to recognize the coexistence of denominations in the Passau Treaty (1552), which was regulated by the Peace of Augsburg (1555).

With the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina , written in 1532 , Charles V issued the first general penal code in the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1556 Karl resigned from his rulership and divided his domains between his eldest son Philip II , who inherited the Spanish and Burgundian possessions, and his younger brother Ferdinand I , who had already received the Austrian hereditary lands in 1521 and who now also received the imperial title , on. This division split the House of Habsburg into a Spanish (Casa de Austria) and an Austrian line (House of Habsburg-Austria). Charles died in 1558 in his palace next to the monastery of Yuste in Spain.

Life

Family and origin

The rise of the House of Habsburg to a major European power began in 1477 through the marriage of Maximilian of Austria to Maria of Burgundy . As the heiress of the Duchy of Burgundy , Maria was the richest bride of her time and those involved hoped for support in the conflict against France ( War of the Burgundian Succession ) and a great gain in power for both dynasties through the connection with the imperial family . The marriage resulted in two descendants, Philipp and Margarete , before Maria died in 1482 as a result of a riding accident.

Maximilian, from 1486 as Maximilian I Roman-German King , was now the guardian and regent of his underage son in the Burgundian territories . It was only with the Treaty of Senlis (1493) that he succeeded in partially enforcing his dynasty's claim to succession in Burgundy against France and in transferring the government of the Free County of Burgundy to his son.

As head of the family, Maximilian was keen on a politically advantageous marriage of Philip and arranged a connection to Spain. The Catholic kings Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile ruled there . In order to consolidate the alliance, they arranged a double wedding in 1496/97 between Philipp and Johanna , the second eldest daughter of the royal couple, and between Margaret and the Spanish heir to the throne Johann . After the death of her older siblings (Johann 1497, Isabella 1498) and her nephew ( Miguel da Paz 1500), the various cortes of the Spanish rulers recognized Johanna and her husband Philip as heir to the throne of the kingdoms of Aragon and Castile . It was during these years that Johanna began to experience symptoms of depression .

The marriage between Philipp and Johanna resulted in a total of six offspring. While Karl, Eleonore, Isabella and Maria grew up in the Netherlands, Ferdinand and Katharina lived in Spain.

- Eleonore (November 15, 1498 - February 18, 1558)

- Karl (February 24, 1500 - September 21, 1558)

- Isabella (July 18, 1501 - January 19, 1526)

- Ferdinand (March 10, 1503 - July 25, 1564)

- Maria (September 17, 1505 - October 17, 1558)

- Katharina (January 14, 1507 - February 12, 1578)

After the death of Isabella I, Joanna succeeded her as Queen of Castile in 1504. Philip agreed in the Treaty of Villafáfila (1506) with Ferdinand II on the exercise of government power. Shortly after the conclusion of the contract, Philipp died on September 25, 1506 and brought Johanna into a pathological gloom, which earned her the nickname "the madwoman" . Her father took over the reign of Castile and in 1509 ordered her permanent residence in the castle of Tordesillas . Johanna died on April 12, 1555 at the age of 75 in complete mental derangement. Through the marriage policy of his grandparents, Karl united the lineages of four independent territories in his person:

- from Maximilian I .: the Archduchy of Austria

- of Mary of Burgundy: the Duchy of Burgundy , the Burgundian Netherlands

- by Ferdinand II .: the lands of the Crown of Aragon including Naples , Sicily and Sardinia

- by Isabella I .: the lands of the Crown of Castile with the newly conquered overseas territories

Youth in the Netherlands

Karl, Archduke of Austria, was born on February 24, 1500 in the Prinzenhof , a residence in the Flemish trading city of Ghent . In memory of his paternal great-grandfather, the Burgundian Duke Charles the Bold , he was baptized Karl (Charles) by the Bishop of Tournai on March 7, 1500 in Ghent's St. Bavo Cathedral . Godparents were Margaret of Austria and Margaret of York as well as Charles I. de Croÿ , an adviser to his father. As early as 1501, Philip the Fair gave his son the title of Count of Luxembourg and appointed him Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece .

In fact, Karl grew up without parents. At the side of his sisters Eleonore and Isabella, Karl remained in the Netherlands while his parents traveled to Spain in 1502 to be sworn in as heir to the throne. Shortly after their return, after the birth of Karl's sister Maria, they traveled to Spain for good. When Philipp died in 1506, Maximilian (from 1508 Roman-German Emperor ) appointed his daughter Margarete both regent in Burgundy and foster mother of six-year-old Karl and his sisters. Karl did not meet his mother again until 1517. Margarete emphatically raised her nephew in succession and carefully prepared him for the princely tasks of his future life. The politically and intellectually gifted, but also artistic governor lovingly raised the children entrusted to her. She had them taught by Dutch and Spanish scholars. At her courts in Brussels and Mechelen , which were influenced by Flemish culture , she gathered artists and scholars who made them centers of Renaissance humanism .

In addition to his aunt, the theologian Adrian von Utrecht , rector of the University of Leuven (later Pope Hadrian VI ), played an important role in the upbringing of Charles; He laid the foundation for piety and certainty of faith ( devotio moderna ), which characterized the character of his pupil throughout his life. In 1509, Emperor Maximilian appointed the nobleman Guillaume II. De Croÿ as Grand Chamberlain and commissioned him to introduce Karl into political and court life. The emperor attached great importance to imparting knightly virtues ; because the ceremonial of Burgundy, one of the richest countries of the late Middle Ages , still lived in the tradition of medieval-knightly culture and was formative for the courtly society of the time. De Croÿ awakened his pupil's interest in politics, educated him to work regularly and to fulfill his duties. In contrast to the Anglophile Margaret, de Croÿ was careful to avoid hostilities with France.

Even in his youth, Karl showed essential character traits that should shape his life: appearing with sovereign dignity, he was surrounded by the aura of loneliness and he became more and more inaccessible in the course of his life. This tendency was supported by his pronounced Habsburg lower lip ( progeny ), which is said to have made speaking and breathing difficult for him and increased the distance to his surroundings. In addition, Karl had a great willpower with which he controlled his often sickly and weak body. Much to the delight of his imperial grandfather, Karl demonstrated great skill and perseverance in riding , fencing , shooting, hunting and in tournaments.

In addition to the French language , the language of the Flemish aristocracy, Karl spoke Latin and Dutch , had little knowledge of German and had to learn Spanish from 1517 onwards.

Burgundian and Spanish heritage

Due to the pressure of the Dutch nobility and ongoing tensions between Maximilian and Margarete, who had become politically too independent for the emperor, the emperor declared his grandson of age prematurely and ended Margarete's guardianship. The age of Charles, Duke of Burgundy , was solemnly proclaimed in front of the States General on January 15, 1515 in the Coudenberg Palace in Brussels . Karl founded his own court with the medieval ceremonies of Burgundy, while nation- states of a modern style began to form elsewhere . The homage celebrations were accompanied by tournaments , hunts and splendid banquets.

The following year, on January 23, 1516, Charles's maternal grandfather, Ferdinand II of Aragón, died. In his will he had designated his daughter as his successor in the kingdoms of the Crown of Aragon and Charles as regent. Karl, however, was proclaimed king of Castile and Aragon together with his mother in different appeals. The claim to inheritance of the House of Habsburg was recognized in Castile, but Charles was urged to receive the homage of the Spanish estates in persona . Despite the warnings from Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros , regent of Castile, it was more than a year and a half before Charles complied with the request to be officially recognized in Spain. Advised by Guillaume II. De Croÿ, Karl initially sought an understanding with the French King Francis I in the Treaty of Noyon (August 13, 1516) in order to secure his position in Burgundy during the expected absence. This step corresponded to the pro-French attitude of part of the Burgundian nobility, which also included important advisers to Charles. Only after his rule had been secured by contract, Charles and his sister Eleanor traveled to Spain in September 1517. There they first visited their sick mother in Tordesillas, before Karl met his brother Ferdinand for the first time. To avoid rivalries, he soon left Spain, left the succession to his older brother and in turn went to the Netherlands to complete his training with Archduchess Margarete.

Charles and his Flemish court were perceived as strangers in Spain, which is why he had to make concessions to the local nobility. Including the assurance that no money will be transferred abroad and no offices or benefices will be given to foreigners. Karl, who used an interpreter, was also asked to learn Spanish . In February 1518, the Castilian Cortes finally paid homage to the new king in Valladolid , followed by Aragón and Catalonia . Since Charles united the rule in the kingdoms of the Crown of Castile and the Crown of Aragon, including their subsidiary kingdoms Navarre , Naples , Sicily and Sardinia , in one person for the first time, he is considered the first king of Spain (as Carlos I ). His territory also included the possessions in America and the Pacific region east of the Moluccas .

King's election in the empire

Charles V inherited four politically independent empires from both grandparent couples:

- by Ferdinand the Catholic: Aragón and the Italian possessions (Sicily, Naples and Sardinia)

- by Isabella the Catholic: Castile and the conquered overseas territories

- by Maximilian I .: the Austrian hereditary lands

- of Mary of Burgundy: the Burgundian countries, that is the Free County of Burgundy (today's Franche-Comté) and the Burgundian Netherlands (essentially today's Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands).

Emperor Maximilian died in January 1519 and left his grandson Karl, Duke of Burgundy and Spanish King, the Habsburg hereditary lands (core area of today's Austria) and a controversial claim to the Roman-German imperial title. Before his death, Maximilian had no longer succeeded in arranging the succession in the empire in the sense of the House of Habsburg. In addition to Charles, Franz I of France and Henry VIII of England also applied for successor as Roman-German King and Emperor , and at the end of the election campaign the Curia also brought in Elector Friedrich of Saxony , and Karl's brother Ferdinand was also a candidate for a time considered. However, even Karl's application was not without controversy. Spanish circles feared that the election of Charles could put the Iberian Peninsula on the verge of his interest. The application was mainly driven by the Grand Chancellor Mercurino Arborio di Gattinara , who had been in office since 1518 , who stylized Karl as a "German" candidate. This was by no means easy, as only one line of ancestry went back to the empire and he spoke hardly any German .

The actual dispute took place between Charles and Francis I , the intensity of which exceeded all previous and subsequent elections of this kind. Both candidates represented the imperial idea of a "universal monarchy" which should overcome the national division of Europe. A dominant ruler was supposed to ensure peace within Europe and protect the West from the expansionist striving of the Muslim Ottomans (" Turkish threat "). The humanist Erasmus von Rotterdam , for example, criticized this , but the idea of a unified Europe was definitely powerful. The tradition of the Habsburg emperors, whose natural heir he was considered to be, and the importance of the dynasty in the empire spoke for Karl. On the other hand, because of his possessions outside of Germany, he was significantly more powerful than his predecessors, and his priorities so far lay outside the empire. The imperial princes therefore feared that the monarch would dominate the imperial estates , but the French king was not perceived as a threat. In the run-up to the election, Franz I secured the votes of the Elector and Archbishop of Trier and of the Elector of the Palatinate and also offered 300,000 guilders to vote. The electoral college consisted of three ecclesiastical (the archbishops of Mainz , Cologne and Trier) and four secular princes (the King of Bohemia , the Duke of Saxony , the Margrave of Brandenburg and the Count Palatine near the Rhine ). For this election, these were the archbishops Albrecht von Brandenburg (Mainz) , Hermann V. von Wied (Cologne) , Richard von Greiffenklau zu Vollrads (Trier) and the secular electors Ludwig II (Bohemia and Hungary) , Friedrich III. (Saxony) , Joachim I (Brandenburg) and Ludwig V (Palatinate) . The wife of the King of Bohemia, Mary of Hungary , is a sister of the candidate Karl; the two eligible voters, the Margrave of Brandenburg and the Archbishop of Mainz (also Imperial Arch Chancellor ), are two brothers from the House of Hohenzollern .

In this very difficult situation for Karl, the financial strength of the businessman Jakob Fugger decided in favor of the Habsburgs. He transferred the monstrous sum of 851,918 guilders to the seven electors, whereupon Charles was unanimously elected Roman-German king in his absence on June 28, 1519 in Frankfurt am Main in St. Bartholomäus . According to this, the Roman king should actually be crowned emperor by the pope in Rome; The procedure was changed due to the political situation and the coronation of Charles V was carried out in Bologna in 1530 by Pope Clement VII . Jakob Fugger raised almost two thirds of the total, namely 543,585 guilders himself. The remaining third was financed by the Welsern (around 143,000 guilders) and three Italian bankers (55,000 guilders each). This voting money is often seen as a bribe. But the balance of interests between the new king and elector was not unusual in earlier and later Roman-German royal elections. The only remarkable thing was the amount of 1519, which resulted from the uncertainty about the outcome of the election, as well as the compensation in money instead of land, titles or rights. An election surrender was negotiated between the electors and Charles's ambassadors - a new phenomenon when a king is elected. The content almost had the character of an imperial constitution, such as that represented by the Golden Bull . In it, Karl came to meet the imperial estates in various points up to the government of the empire and foreign policy. Was confirmed as the establishment of an imperial government , as were all Regalia , privileges and Reich deposit properties confirmed the princes. The fear of foreign rule was expressed in the provisions that only Germans were to be placed in important Reich offices and that foreign war people were not allowed to be stationed on the soil of the Reich. The curia's demands for money were also to be limited and the large trading companies abolished.

Karl was crowned on October 23, 1520 in Aachen Cathedral by the Archbishop of Cologne, Hermann V von Wied , and then called himself “King of the Romans, chosen Roman emperor, always Augustus .” Pope Leo X agreed on October 26, 1520 to lead this title. From then on, Karl bore the title:

- We, Charles the Fifth, Roman emperor chosen by God's grace, always Augustus, at all times multiples of the empire, in Germania, in Castile, Aragon, León, both Sicilies, Jerusalem, Hungary, Dalmatia, Croatia, Navarra, Granada, Toledo, Valencia, Galicia, Mallorca, Seville, Sardinia, Cordoba, Corsica, Murcia, Jaén, Algarve, Algeciras, Gibraltar, the Canary and Indian Islands and the mainland, the Oceanic Sea & c. King, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, Lorraine, Brabant, Steyr, Carinthia, Carniola, Limburg, Luxembourg, Geldern, Calabria, Athens, Neopatria and Württemberg & c. Count of Habsburg, Flanders, Tyrol, Gorizia, Barcelona, Artois and Burgundy & c. Count Palatine at Hainaut, Holland, Zealand, Pfirt, Kyburg, Namur, Roussillon, Cerdagne and Zutphen & c. Landgrave in Alsace, Margrave of Burgau, Oristan, Goziani and the Holy Roman Empire, Prince of Swabia, Catalonia, Asturias & c. Lord of Friesland and the Windischen Mark, Pordenone, Biscaya, Monia, Salins, Tripoli and Mechelen & c.

Plus Ultra ( lat . For “always further”) was his motto .

Charles V, who ruled over an empire "in which the sun never set", was now deeply indebted to the Fuggers. In 1521 his debts to Jakob Fugger amounted to 600,000 guilders. The emperor repaid 415,000 guilders by compensating the Fuggers with the Tyrolean silver and copper production. When at the Reichstag in Nuremberg in 1523 the imperial estates discussed a limitation of the commercial capital and the number of branches of companies, Jakob Fugger reminded his emperor of the electoral aid granted at the time: “It is also knowingly and on the day that your Imperial Majesty won the Roman crown could not have achieved without my involvement ... " . With the simultaneous demand for immediate settlement of the outstanding liabilities, Jakob von Kaiser Karl achieved that the considerations on the monopoly restriction were not pursued any further. In 1525 Jakob Fugger was also awarded the three-year lease for the mercury and cinnabar mines in Almadén, Castile . The Fuggers remained in the Spanish mining business until 1645.

Rule organization and self-image

The news of his election as king reached Karl near Barcelona . Here Charles, who fled the plague , stayed in a monastery in Molino del Rey, 20 kilometers away . In order to normalize the relationship with the rulers who were defeated in the competition for the empire, he traveled from Spain via England and the Netherlands to the empire on the occasion of his coronation in 1520 . High hopes were associated with Karl's accession to power. Martin Luther wrote: "God has given us young, noble blood for our heads and has thus awakened hearts to great hope."

The establishment of institutions that encompassed the entire complex of rulers never happened. The individual domains ( territorialization ) were held together solely by the person of the emperor, whose central task was to bring together the various components ("casas"). Charles exercised his rule less by attempting centralization than by coordination. Personal and client relationships, the court and the dynasty were important, which is why the court of Charles V was one of the most complex of its time. In particular, the initial predominance of the Burgundians aroused resentment among the Spanish elites, who enjoyed special weight alongside the Burgundians. The emperor transferred the Burgundian court ceremony, which was ecclesiastically charged, to Spain - this later became known as the Spanish court ceremony . Although the court displayed its splendor on certain occasions, it was much less pronounced under Charles than under previous Burgundian rulers. Emperor Karl was the last emperor without a permanent residence or capital. The multinational court, comprising between 1000 and 2000 people, moved between the individual territories, which is why the imperial cities in particular suffered greatly from the associated burdens. In the German Empire, the members of the Spanish court were extremely unpopular.

At the imperial level, Karl temporarily installed leading advisors or "ministers", the most important of which include Guillaume II. De Croÿ and the Piedmontese lawyer Mercurino Arborio di Gattinara . When it came to military matters, Karl initially trusted Charles de Lannoy , who had already served as a military leader for his grandfather. It is not entirely clear what role Charles himself played in the early days of his rule. Nicolas Perrenot de Granvelle and his son Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle later had significantly less influence. Around 1530, Charles decreed that the areas of responsibility were divided into two: Francisco de los Cobos y Molina was responsible for the Spanish territories, the overseas possessions in America and Italy, and there was also a Burgundian State Secretariat for the Burgundian possessions under Granvelle, to which the office of Imperial Vice Chancellor was subordinate. The Archbishop of Mainz, as Imperial Chancellor , largely handed over his powers to Gattinara. In the last years of Charles's reign something like a cabinet was created that was responsible for the entire empire, but it turned out to be ineffective.

To secure power in his broad, heterogeneous domain, Karl appointed family members as regents and governors in the Spanish lands, in the Netherlands, in the hereditary lands and also in the empire. According to the provisions of the Worms Treaty (1521) and the Treaty of Brussels (1522) , his younger brother Ferdinand was entrusted with the reign of the Austrian hereditary lands and the Duchy of Württemberg ; the last remnants of sovereign rights in the empire ceded to Ferdinand in 1525. If necessary, Ferdinand represented the emperor in imperial affairs, contact was maintained in writing. Tens of thousands of letters testify to the intensity of this communication, and Karl remained informed of the events even when he was absent and was able to issue appropriate instructions. This way of exercising power was made considerably more difficult by the distance, especially since Ferdinand was initially given little room for maneuver of his own.

In the empire, Charles V saw the universal power of order in Europe above the individual states. His tasks included repelling the unbelievers and securing peace within the West. In addition, there was protection, but also reform of the church. The Grand Chancellor Mercurino Gattinara with his idea of the emperor as dominus mundi d. H. as a world monarch, Karl's self-image has been strongly influenced.

Overseas possessions

To finance the wide-ranging power politics as well as the army and the navy, for which the costs rose sharply, especially in the 1530s, Charles V was dependent not least on the Spanish income. In the middle phase of his reign, Charles received at least one million ducats per year from the Spanish possessions . Spanish Affairs Director Francisco de los Cobos y Molina built an effective bureaucracy to collect the funds. Soon, however, these were no longer sufficient. The gold and silver deliveries of the conquistadors from the newly conquered countries on the American continent gained in importance. After the development of the Potosí silver mines , between 1541 and 1560 480 tons of silver and 67 tons of gold reached Spain. A fifth of the income from America went to the crown, which is why Charles V's campaigns would not have been possible without the gold shipments of Hernán Cortés from New Spain and Francisco Pizarro from Peru . In Spain began to organize the administration and exploitation of the new colonies. Seville became a monopoly port for traffic with America in 1525, and the central authority of the colonies was also established there with the Council of India . The viceroyalty of New Spain was proclaimed in 1535 and the viceroyalty of Peru in 1542 . The precious metal obtained served as the basis for bonds. Despite the high income, the income was not enough to cover the expenses for Karl's power politics. At times, the American possessions were mortgaged to the creditors. So around 1527 today's Venezuela came to the trading house of the Welser , who exploited this area until 1547. Overall, the bond policy has greatly accelerated debt, particularly in Spain.

Even if the conquests were not centrally controlled, Karl nevertheless promoted the expansion policy and helped finance Ferdinand Magellan's circumnavigation of the world . Through the new possessions in America and in the Philippines named after his son and heir to the throne Philip (which only became formally Spanish after Charles' death) in the Pacific , Charles V ruled over an empire of which he is said to have said that " the sun never set ”. In the opinion of the emperor, the overseas conquests were justified by the conversion of the pagans to Christianity. Even under the influence of Bartolome de las Casas , Charles tried to counteract the enslavement of the Indians through various ordinances and laws. In the 1540s, a liberation of all Indians was even ordered. Ultimately, however, these attempts failed because of the conditions in the colonies and Charles' need for gold.

Diet of Worms 1521

The situation in the empire was difficult when Charles came to power. Unrest spread among the peasants and poor city dwellers. The imperial knighthood was also restless. In particular, the Reformation movement around Martin Luther began to gain in importance. In the Luther case, Charles V initially followed his advisers from the humanist environment and at the end of November 1520 promised arbitration. Luther was excommunicated by the Pope in 1521. The usual enforcement of the imperial ban in such cases did not take place because Luther was under the protection of Elector Frederick the Wise . This demanded a clarification of the case on the basis of imperial law without taking into account the Roman heretic trial. The previous relationship between the Empire and the Church was thus called into question. The Reichstag was the appropriate forum to clarify the question. Karl agreed to a compromise and invited Luther to Worms so that he could revoke his teachings there. If Luther were to stand firm, Karl threatened the execution of the eight. The Luther case was used for political purposes between the Emperor and Pope Leo X. It served as a means of exerting pressure on the emperor in order to achieve rapprochement with the curia.

The first Reichstag at the time of Charles V took place in Worms in 1521. The focus was on questions of imperial reform and how to deal with the Reformation movement that started out from Martin Luther. As far as the questions of the imperial constitution were concerned, the conflict between the emperor and imperial estates initially concerned the power of government. This question had not been clearly clarified under Maximilian I, and the estates demanded again to participate in the government through the establishment of a Reich regiment. Karl had promised this in his election surrender. But Karl insisted that the imperial regiment should only take effect in the absence of the emperor. In the regimental order resolved on May 26, 1521, he was able to largely prevail. In addition, with his brother Ferdinand as governor and head of the imperial regiment, the imperial influence was largely secured even in his absence. But in the end the decision was only a compromise between the estates and the monarchical principle. A conflict between the emperor and the imperial estates could therefore not be ruled out. Further questions that had to be clarified concerned the Reich Chamber of Commerce and the order of the peace . With regard to the Reich Chamber Court, which had got into a crisis, a workable compromise could be reached between the Emperor and the Imperial Estates, which contributed to the fact that the court gained reputation and importance. With a view to the peace in the country, the execution of the judgments of the court was transferred to the imperial circles . In this way, the imperial circles were given a higher level of competence than the individual imperial estates. The imperial finances, which were put on a sustainable basis, were also regulated. As a means of financing, it was finally agreed on the system of matriculation fees . Basically, this regulation applied until the end of the empire.

The Reichstag in Worms became known through the Luther question. The attitude of the emperor to Luther's positions before the Reichstag is not entirely clear. Personally, he seems to have had a very differentiated relationship to the Reformation theses. However, after the verdict of the Roman heretic trial, he held Luther convicted. Outside the empire, he had the scriptures forbidden and against Luther's followers.

In the run-up to the Reichstag there had been negotiations on the part of the imperial court both with Electoral Saxony and with the Curia in Rome. Initially, Charles V and his advisors did not seem to have had a solid line. However, the emperor wanted to prevent participation of the imperial estates in the question of the imposition of imperial ban. He did not succeed. Charles V felt compelled to assure Luther safe conduct to Worms. A first interrogation of Luther took place on April 17th in the presence of the Emperor. In another interrogation the next day, Luther refused to revoke his writings as long as no one had refuted them on the basis of the Bible. After Luther's departure, Charles V made a statement on April 19, in which he pledged himself to the thousand-year-old Christian tradition, to his loyalty to Rome and to the protection of the Roman Church. He did not go into the content of Luther's teaching. After some preparation time, on May 8th, Charles V issued the Edict of Worms , which imposed the imperial ban on Luther and forbade his writings. However, he could no longer stop the Reformation movement, especially since Frederick the Wise brought Luther to safety in the Wartburg . In secret negotiations between Friedrich and the imperial court, it was agreed that Saxony would not officially receive the edict. The background to the imperial reluctance were the clashes with France. Overall, the empire only played a minor role for Karl at this time. At the Reichstag, Karl did not find any real understanding of the Reich and its problems.

Securing power in Spain, marriage

During his absence in Spain Karl had entrusted his former teacher Adrian von Utrecht with the reign of Castile. The rebellion of the Comuneros developed in 1519 against this reign, which was perceived as foreign rule, and was mainly supported by the bourgeoisie of the Castilian cities, especially Toledos . The Comuneros found support from parts of the clergy and the nobility . Their goal was to limit the royal power in favor of the Cortes. At the same time there was a social revolutionary movement in the Kingdom of Valencia , which became known under the name Germanía , there was no cooperation between the movements in the various Spanish territories. Concerned about the anti-feudal attitude of the insurgents in Valencia, much of the nobility sided with Charles, and the insurgents under Juan de Padilla were defeated at Villalar in 1521 . To clarify the situation, Charles V traveled personally to Spain in the winter of 1521/22, and although he insisted on being lenient, he saw the uprising as an offense against the divine order. There were several death sentences and property confiscations. There was also a bishop among those executed, which made Karl fear the excommunication . Even if the papal absolution came some time later, the executions kept Charles busy until his death. In the course of his reign, Karl managed to limit the political influence of the high nobility without affecting his other privileges, thus securing his allegiance. The Spanish Inquisition , which primarily acted against Jews and Muslims who had converted to Christianity and their descendants, continued to function under Charles V. On the need to fight heretics and defend Catholicism, Charles and the leading forces in the Spanish territories agreed. After securing power in favor of the crown, Spain became a central power base of the emperor.

Charles had been engaged to Mary Tudor , daughter of King Henry VIII of England , since 1522 . But also because of financial advantages, he decided to marry Isabella of Portugal , the daughter of the Portuguese King Manuel I. The wedding took place on March 10, 1526 in the magnificent Alcázar of Seville. Because Isabella's mother Maria was also an aunt of Charles V and thus the imperial spouses were first cousins, they needed a dispensation for the marriage , which Pope Clement VII also granted. The people cheered the graceful Portuguese, who thanked her in the purest Castilian for the endless ovations and immediately won the hearts of the masses for herself. Although the marriage of the imperial couple was purely politically motivated, the couple quickly fell in love and had an extremely happy marriage, which is also proven for posterity in the form of numerous letters between the two. Charles V always showed his wife a courtly veneration that went far beyond the usual extent.

In the summer of 1526 the newlyweds moved from Seville to Granada and stayed there in the Alhambra until the end of the year . The emperor was even reprimanded by members of the Council of State for not extending his honeymoon too long.

European power politics

War until the Peace of Madrid (1520-1526)

In order for Karl's claim to enforce the empire as a superordinate, supranational European regulatory power, a power superior to the other states was required. Wealthy Italy played a central role here, because if it was possible to gain significant influence there, European hegemony would be possible. In addition, the emperor wanted to regain the Duchy of Burgundy, which fell to France in 1477 , for the House of Habsburg, since his Burgundian ancestors were buried in Dijon . His will in 1522 emphasized the importance of Burgundy for Charles by decreeing to be buried next to his ancestors in the Chartreuse de Champmol of Dijon. With this nostalgic endeavor, he challenged the compromise of the division of the Burgundian inheritance of 1493 ( Treaty of Senlis ). Furthermore, Charles V wanted to end the French feudal rights in the county of Flanders and the Artois and also claimed the southern French regions of Provence and Languedoc as an imperial fief .

As a result of these territorial demands, Charles came into conflict with the power-conscious French King Francis I, who was not prepared to give in to the claims. He, too, harbored hegemony efforts in Italy: after a military victory over the Swiss in 1515, large parts of northern Italy, and in particular the Duchy of Milan, fell to France, and he also had claims to the Kingdom of Naples and the parts of the Kingdom of Navarre that had fallen to Spain in 1512 .

As early as 1520 Charles had obtained the tolerance of the English King Henry VIII for his planned war against France, a year later he was able to win the Pope for an anti-French alliance. First, Henri d'Albret , who lived in exile in France, marched into Navarre, Spain, but had to withdraw after a few weeks; There were also skirmishes on the Dutch-French border. In the second half of 1520 the direct confrontation between Charles V and Francis I began in Champagne and northern Italy, and in November 1520 Henry VIII joined the war on the side of the emperor. At first the imperial troops were successful, until May 1522 large parts of northern Italy were in the hands of the emperor. The House of Sforza was returned to Milan as an imperial fief, Duke Charles III. de Bourbon-Montpensier fell away from the French king, but the plans to acquire his own territory at the expense of the French crown failed and he had to flee into exile at the imperial court. Due to the strong position of Charles V, an anti-imperial mood developed in Italy, the Pope and the Republic of Venice tended more and more towards France. For their part, the French troops began to achieve military success. An English invasion of France failed, as did the imperial advance into Provence in 1524. In return, the French succeeded in conquering Milan and besieging Pavia , which they now controlled almost all of Northern Italy. On February 24, 1525, Charles V's troops finally achieved a decisive military victory in the battle of Pavia and they were able to take the French king prisoner.

Francis I arrived in Barcelona as a prisoner on June 19, 1525 and was brought to Madrid in July. How one should deal with the imprisoned king and the advantageous situation in terms of power politics was controversial between Karl and his advisors. Gattinara would have loved to have him killed, and a de facto smashing of France was in his mind. Charles V, however, joined the proposals for a moderate peace. It was not until November 1525 that Franz responded to the emperor's demands on the condition that Burgundy could only be surrendered after his return to France. In the Treaty of Madrid (January 14, 1526), Francis I renounced the Duchy of Milan and the feudal sovereignty in Flanders and the Artois. However, he did not give in to the demand to renounce the claims in Burgundy. The release of the French king was to take place with the abandonment of his two sons, who were housed under unfavorable conditions in various Castilian fortresses until the Peace of Cambrai (1530).

On the part of the emperor, the peace conditions were intended as a mild gesture of reconciliation, and the promise to give his sister Eleanor as a wife to the French king also aimed in this direction. Karl hoped to get Franz to fight together against the Ottomans and the Lutherans and the Habsburg appealed to the "gloire" - the knightly honor - to keep the treaty and released Franz - against the advice of his advisors - from captivity. On the French side, however, the peace was not viewed as moderate, but as a peace of submission.

War against the Holy League of Cognac (1526–1529)

After his release from Spanish captivity and his return to Paris, Francis I revoked the provisions of the Peace of Madrid because he had acted under duress. He succeeded in creating a broad anti-Imperial alliance between France, Pope Clement VII , the Republic of Venice, Florence and finally Milan ( Holy League of Cognac ). The Duchy of Bavaria also belonged to the anti-Habsburg opposition. Franz had already come to an understanding with Henry VIII and the fighting broke out again. When an Ottoman army threatened the Austrian hereditary lands in 1526 , the situation for Charles V became threatening.

The expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the early modern period meant a long-term shift in the European balance of power. The conquering expeditions of the Ottoman armed forces along the Mediterranean coast and on the Balkan peninsula in the direction of Vienna threatened the Habsburg rule in the hereditary lands as well as the peace in Europe. In 1521 the Ottomans conquered Belgrade, in 1526 they defeated the Hungarian King Ludwig II in the battle of Mohács . With the death of Ludwig, the House of Habsburg in the person of Ferdinand received an inheritance claim to the crowns of Bohemia and Hungary . Now the Ottomans threatened Ferdinand's rule in Hungary ( First Austrian Turkish War ) and besieged the city of Vienna in 1529 with a force of 120,000 men. However, due to his campaigns in northern Italy, Emperor Karl was militarily bound and could not support his brother Ferdinand, who was ultimately only able to rule part of Hungary.

The war against France increasingly overwhelmed the imperial finances. The mercenaries in northern Italy were dissatisfied with their wages and when their commander Georg von Frundsberg tried to prevent an impending mutiny , he suffered a stroke. The mercenaries then marched against Rome , which they regarded as the "whore of Babylon" . When Charles of Bourbon fell while storming the city on May 5, 1527, the leaderless imperial mercenaries sacked the city at the infamous Sacco di Roma . Pope Clement VII had fled to Castel Sant'Angelo and surrendered at the beginning of June 1527. Once again an adversary was in the hands of the imperial family and Charles V prevailed again with mild treatment of the enemy. Although Charles was not responsible, the incident was viewed as evidence of the imperial threat to the papacy and the emperor's violent policies in Italy. The events of the Sacco di Roma strengthened the anti-imperial forces in Italy and Charles found himself in distress. This guaranteed the Republic of Genoa its independence, whereby Andrea Doria with the Genoese fleet switched to the emperor's side and cut off the supply routes of the French troops in Italy. The forces of the League of Cognac suffered military defeats and Francis I had to make peace again.

The Women's Peace of Cambrai , negotiated on August 5, 1529, sealed France's renunciation of claims in Italy. The renunciation of the French feudal claims in Flanders and Artois was confirmed, while the Emperor for his part withdrew from the claim to the Duchy of Burgundy. With the peace the rule of the House of Habsburg was secured until the end of the 16th century. In the Peace of Barcelona , Charles granted the Pope favorable peace conditions and concluded a defensive alliance with him. The holding of a council on church reform could not be enforced by Karl. The reconciliation with the Pope led to Charles receiving the Iron Crown of the Lombards from Clement VII on February 22, 1530, who crowned him Roman Emperor on February 24, 1530 in Bologna in the Basilica of San Petronio . Charles V was the last Roman-German emperor whose rule was confirmed by the coronation by the Pope .

Fight against the Ottomans and the French (1532)

The peace, however, was short-lived. In 1532 there was another major campaign against the Ottomans. Charles V took part in it himself, without this war having brought a decision. Karl returned to Spain to start a "crusade" against the Ottomans from there. But he left the fight on the continent to his brother.

The relationship with Pope Clement VII, who increasingly joined France, deteriorated. Henry VIII also turned against the Habsburgs. However, Franz I did not succeed in concluding an anti-imperial alliance with the German Protestants. The French, on the other hand, had been allied with the barbarians and the Ottomans since 1534 . Overall, Karl was unable to decisively weaken the Ottoman-French alliance. But the French did not succeed in revising the results of the Cambrai peace either. Rather, after the Sforza died out, Karl succeeded in taking Milan as an imperial fief and giving it to his son Philip . Charles was able to achieve an important victory in 1535 by conquering Tunis in the Tunis campaign . It was the first time that the emperor personally took part in a battle. The victory increased his reputation in Europe. From Tunis he visited the Kingdom of Naples, including the Charterhouse of San Lorenzo di Padula , and moved from there to Rome. His entry there was like a triumphal procession. However, the power of the barbarians was by no means broken. Francis I conquered Turin. Charles V gave a long speech in the Vatican on Easter Monday, accused the French king of breaching the peace and appealed to the Pope to act as an arbitrator. Also intended as a propaganda measure for the Italian public, this did not lead to success with the Pope. At least he met him on the Council question. On the advice of Andrea Doria, Karl decided to launch a counter-offensive in the direction of Marseille. The attack on the city failed and the imperial army had to return to Lombardy. In the meantime, the cooperation of the French with the Ottomans promoted the rapprochement between the Pope and Charles. In 1538 an anti-Turkish league was concluded between Charles, his brother Ferdinand, Venice and the Pope. In the same year, Pope Paul III mediated . the ten-year armistice of Nice between Charles V and Francis I. This laid down the status quo in Italy. After a meeting between Charles and Francis I, a reconciliation even seemed possible at times.

War against France until the Peace of Crépy (1540–1544)

As early as 1540, Charles and Franz I began to prepare diplomatically for the next armed conflict. The situation worsened when the French envoys sent to Istanbul were murdered by Spanish soldiers on their return. Even if the emperor denied participation, he had a certain complicity. Instead of helping his brother on the Hungarian front, Karl ordered a naval expedition to Algiers in 1541 , but this failed due to the sinking of numerous ships in a storm. Francis I, who was still allied with the Ottoman Empire, declared war on Charles in 1543. This time he relied on a defensive concept and was thus successful against the French advances ( see also: Siege of Nice (1543) ). The alliance between France and Denmark and Sweden was of little importance. In 1543 Charles entered into an alliance with Henry VIII. Instead of looking for the decision in the Mediterranean area, Karl shifted the focus of his efforts to Central Europe. With the defeat of Duke Wilhelm von Kleve , who was allied with France , Francis I lost his last ally in the empire. In 1544, the emperor and the imperial estates agreed in their policy against France. Karl then advanced into French territory. However, the advance failed because of the delaying tactics of the enemy and the fortresses of the country. Henry VIII limited himself essentially to the siege of Boulogne. The army began to disintegrate due to the lack of pay. An advance to Paris could therefore not take place. Nevertheless, the danger led Francis I to the armistice in 1544 in the Peace of Crépy . Franz I contractually renounced future alliance attempts with the Protestant estates in the Reich and undertook to send participants to a council on Reichsboden.

Last foreign wars

The new French King Henry II had been working towards a new offensive alliance with the Ottomans since 1550. He intended to persuade the sultan to break the armistice concluded with Ferdinand in 1547. With his actions against a pirate leader in the Mediterranean, who was also a Turkish vassal, Karl annoyed the High Porte . Ferdinand's negotiations with the Turks failed and there was a threat of a two-front war in Italy and Hungary. Henry II also made an alliance with the Protestant opposition in the empire. In the Treaty of Chambord , which was invalid under imperial law , Henry II undertook to cut off Charles's connection with his troops in the Netherlands. In addition, he was supposed to pay substantial subsidies to the princely opposition. For this he should receive the cities of Metz , Toul , Verdun and Cambrai as imperial vicar. Heinrich then occupied the cities mentioned in the so-called Trois-Évêchés with an army of 35,000 men . After the agreement with the opposition, Karl tried to win back the cities. He besieged the city of Metz, which was strategically located on the line connecting the Netherlands and Italy. The fortress could hardly be taken with the means at the time and was also well defended. The siege therefore failed with high losses. At two and a half million ducats, the campaign was extremely costly; this corresponded to twice the annual income of Spain. As damaging as the defeat at Metz was to Karl's reputation, it did not mean defeat or the end of the war as a whole. Rather, the imperial resumed fighting since 1553 in both Italy and the Netherlands. Peace was only made after Karl's abdication.

Imperial and religious policy

Until the Speyer protest

As a result of campaigns, wars or other obligations, Charles V was absent from the Empire for nine years from the winter of 1521/22 and had given his brother Ferdinand numerous powers in accordance with the provisions of the Treaty of Brussels (1522). He had also promised Ferdinand that he would be elected as Roman-German king and thus as a possible successor. The administration of the Reich was made more difficult by the fact that Karl was represented at the Reichstag with his own envoys, whose instructions were often not coordinated with the governor or the Reich regiment and he reserved the right to personally confirm the Reichstag resolutions. In addition, the imperial regiment proved to be ineffective and the Worms Edict thus had no major effect. Rather, the imperial estates insisted on a general or at least a national council on the religious question, while the emperor forbade the preparations for a national council in 1524. A national church solution to the religious question was no longer possible.

Between 1524 and 1526, the German Peasants' War shook conditions in the empire, combining social demands and influences of the Reformation movement. The absent emperor was hardly involved in the suppression of these uprisings; the main opponents of the peasants were the Swabian League and various imperial estates.

At the Diet of Speyer in 1526 there was renewed movement in the resolution of the religious conflict: again attempts to reform the church on a national basis failed due to the opposition of the emperor staying in Spain, the imperial estates continued to push for a council and decided that the Worms Edict should be implemented in the Responsibility of the individual booths should fall. The imperial farewell laid the foundations for the choice of denominations of the imperial estates as well as for the establishment of a Reformation church system. The further expansion of the Reformation movement was further facilitated by the enmity between the emperor and the pope during the League of Cognac. Landgrave Philipp von Hessen became the engine of a Protestant and at the same time anti-Habsburg politics. At another Reichstag in Speyer in 1529, Ferdinand tightened his pace against the Evangelicals against the will of Charles. These, on the other hand, lodged the Protestation at Speyer , which led to the name Protestants. The Protestant estates tried in vain to persuade Charles V to suspend the Edict of Worms. Then the Protestants began to prepare for a defensive alliance.

Until Nuremberg decency

After his coronation as emperor, Karl returned to the Reich in 1530 with a program of ecclesiastical unity and took over the chairmanship of the Reichstag in Augsburg . The presence of the emperor made the assembly far more binding than all imperial assemblies since 1521. In the invitation to tender, he indicated a renunciation of the Edict of Worms and with this position met the resistance of the Catholic imperial estates and the Pope. Against this background, Karl had already moved away from his desired role as a referee in the Reichstag proposal. Karl asked the Protestants to present their views as a basis for discussion for further negotiations. The Protestants did not take Charles' willingness to negotiate very seriously and came to Augsburg without explaining. Philipp Melanchthon then wrote the Confessio Augustana during the Reichstag . In addition, Strasbourg , Constance , Memmingen and Lindau submitted the Confessio Tetrapolitana . The emperor had the writings examined by a Catholic commission of experts. Above all, Johannes Eck wrote a counter-opinion that became the basis of the Catholic " Confutatio ", with which the Emperor declared the Confessio Augustana to be refuted. Because he was dependent on the empire's financial help against the Ottomans, the negotiations ultimately continued without success. After the evangelical estates left, Karl had the Edict of Worms put into effect again with the votes of the Catholic estates.

Despite the contradiction between the denominations, Karl succeeded in persuading the electors to elect his brother Ferdinand as Roman-German king. However, he had still secured the decisive powers in a secret treaty. Because the Protestant estates had to fear that Charles would take violent action against the Reformed, some united in February 1531 in the Schmalkaldic League . This union also aimed to protect against an overpowering Habsburg. Therefore, at least for a time, Catholic Bavaria was close to the federal government. The federal government was also a possible ally for external powers such as France. This situation forced the emperor to exercise restraint on the question of religion.

As important as the question of religion was, important imperial legal decisions were also made during this period. With the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, Karl issued uniform criminal and procedural law for the entire empire. The Carolina was ratified at the Reichstag in Regensburg in 1532 and is considered the first general German penal code. At the Augsburg Reichstag of 1530, the Reich Police Order was enacted, which became the basis for further Reich laws and regulations in the individual territories. If the regulations were overall moderate, this did not apply to the discriminatory provisions on Jews. Another point during the Reichstag was the discussion about the monopolies of the large trading companies. However, a very extensive draft law was not passed.

Against the background of the Turkish threat, Karl felt compelled, also at Ferdinand's insistence, to conclude the Nuremberg religious peace and Nuremberg decency with the Protestant imperial estates in 1532 . This meant a kind of armistice between the denominations until the religious question was resolved by a general council. From a legal point of view, it was a contract between the emperor and the evangelical imperial estates and not part of the Reichstag farewell. Despite all reservations, this meant that Karl had for the first time abandoned the anti-reformatory path that had been taken since 1521. Luther saw decency as divine confirmation of the Reformation and was convinced that sooner or later a reconciliation of the empire with the Reformation would be possible.

After the campaign against the Turks in 1532, Karl left the empire again for almost ten years. During these years Karl transferred responsibility for Germany to his brother Ferdinand. Charles' absence had a detrimental effect on Habsburg rule in the empire. As early as 1531, Electoral Saxony, Hesse and Bavaria had joined forces across confessional boundaries to form the Saalfeld Bund under the pretext of not recognizing Ferdinand's election as a king , and pursued a more or less open anti-Habsburg policy.

Religious Discussions

The restoration of the rule of Duke Ulrich von Württemberg and his transition to Protestantism also triggered the founding of the Nuremberg League of Old Believers in 1538 , in which Karl and Ferdinand were also involved. On the other hand, the Schmalkaldic League had strengthened its alliance negotiations with Denmark and France. At times the situation even threatened to lead to violent clashes.

In 1539, Charles's wife, Isabella of Portugal, died of a miscarriage. This loss hit him deeply. At the end of the year he felt compelled to leave Spain to take action against unrest in Ghent. There the lower classes of the people had rebelled against the ruling patricians. Religious motives also played a role. The citizens dreamed of a Protestant city under French protection. At the insistence of Francis I, Karl traveled overland through France. Because he could no longer ride longer distances, he used a litter. After he was honored by the king, he traveled on to the Netherlands. With military force he suppressed the Ghent uprising and issued a series of death sentences. From 1541 he was back in the empire.

From the 1540s onwards, Karl took an increasing part in imperial politics. He initially followed a conciliatory course on the question of faith, also with a view to foreign policy dangers. On the Protestant side, corresponding initiatives came from Elector Joachim II of Brandenburg . The Pope also initially signaled approval. A first step in this direction was the Frankfurt decency of 1539. This guaranteed the Protestants an initially limited religious peace. However, it turned out to be ineffective as both sides did not adhere to the established conditions. The emperor tried to continue on the path of compromise. He had a religious talk organized, which took place in June 1540 in Haguenau under the chairmanship of King Ferdinand. However, there was no tangible result. Another conversation should take place in Worms. They also asked for the presence of the emperor at one of the next diets in order to advance the negotiations with his authority. The Worms Religious Discussion was successful, and both sides agreed on compromise formulas on important theological issues. The talks were to be continued at the Reichstag.

At the Regensburg Reichstag of 1541, Karl was actually present again in person. There, on the basis of the Worms resolutions, another religious discussion took place between high-ranking and respected representatives of both faiths. Certain compromises were made on individual issues, and there were indications of a partial unity and the recognition of Protestantism under imperial law. The Curia and the determined Old Believers, especially the Duchy of Bavaria and Kurmainz, objected to this. The Protestant estates as well as Luther and Melanchthon did not agree with the results either. After the failure of this attempt at compensation, the Council question came to the fore again. The imperial attempt at compensation had largely failed. The emperor met the Protestants on other issues. For example, the Nuremberg decency was extended. Karl achieved a certain degree of success when he was able to get Philipp von Hessen , one of the leaders of the Protestants, on his side.

Council policy

As early as 1529/30 Karl began to push for a general council to reform the church. At the same time it was a means for him to solve the religious problem in Germany. With Clement VII, Karl met with little concession. Paul III Although he saw the need for a church assembly, he feared the influence of Charles on the members of the council. Francis I was not prepared to make concessions in matters of a council. Rather, he was interested in the conflict between the emperor and the Protestants in the empire. Under pressure from the emperor, Paul III appointed. the council on May 23, 1537 in Mantua . The German Protestants decided not to take part in the council, but decided not to hold a counter-council. The council itself was postponed several times as a result of French policy. Together with the emperor, the Catholic imperial estates renewed the demand for a council. At the Diet of Regensburg in 1541 it was decided to convene a national council if necessary. The convocation of a general council failed again because of Francis I. Only with the Peace of Crépy the way was clear. At the instigation of the emperor, the Council of Trento was opened in 1545 . The Pope had accepted the Protestants' demand to hold the council on Reichsboden, but the essential decisions were made without the participation of the Protestants. The conclusion of the council some twenty years later marked the actual beginning of the Counter Reformation.

Schmalkaldic War

In the absence of the emperor, the Reichstag made no further progress in the following years, particularly on the religious question. After an often long absence, the emperor was then present in the empire for a long time between 1543 and 1551. From Germany he wanted to realize his plan for a universal monarchy. France was to be defeated, the problem of religion in the empire was to be resolved, and the imperial constitution was to be redesigned in the monarchical sense. In doing so, Karl relied primarily on military means. He left his sixteen-year-old son Philip as regent in Spain. He was married to the Infanta Maria of Portugal . Karl gave the son a private and a political will. The latter made it clear that he considered his plans to be the greatest venture of his reign. The war with France up to the peace of Crépy has already been mentioned. But in the empire too, Karl now went on the offensive.

In 1543 Charles attacked the United Duchies of Jülich-Kleve-Berg in the Third War of the Geldr Succession . One background was the interest from the Netherlands in the Duchy of Geldern , which had inherited from Wilhelm von Jülich-Kleve-Berg . The duke sought protection from France, from the Schmalkaldic League and from Archbishop Hermann von Wied. There was no significant support. Düren was destroyed. Geldern went to Karl, who united it with the Netherlands. The Duke also had to promise in the Treaty of Venlo not to join the Reformation. Overall, the success of Charles inhibited the advance of the Reformation in parts of northwest Germany and made the weakness of the Schmalkaldic League clear.

At the Reichstag in Speyer in 1544, Karl appeared with a stronger position vis-à-vis the imperial estates. This granted him not only support for the war against France, but also, for the first and only time, financial aid for a new war against the Ottomans under Suleyman I. It was thus possible to separate the two most dangerous opponents of his policy from one another. The Protestant estates, however, demanded a high price. The religious trials before the Reich Chamber of Commerce should be finally stopped and the Augsburg confession should be recognized under Reich law. Charles set aside his self-image as patron of the church in favor of the fight against France and agreed to the demands up to a council decision or that of a Reichstag. The Pope responded to this compromise with harsh criticism, to which Luther and Calvin in turn defended Charles V.

The Treaty of Crépy of September 1544 gave the emperor scope for a solution to the religious question. After the failure of his mediation policy, Karl had decided to take violent action against Protestantism. To this end, considerable financial efforts were once again made. The Pope promised the emperor an army of 12,500 men and large sums of money. Charles was also allowed to sell Spanish church property to finance the war. The start of the war was delayed for various reasons. Last but not least, the transition from the Electoral Palatinate to the Reformation played an important role. The Regensburg Religious Discussion of 1546 brought no progress whatsoever. The decision to go to war was made at the Diet of Regensburg in 1546, which was again chaired by the emperor. He succeeded in winning over the Pope, Bavaria, Duke Moritz of Saxony and other allies.

An economic war was waged against the Protestant cities of Frankfurt am Main , Strasbourg, Augsburg and Ulm . Trade goods were confiscated and the cities' economies were hit. In 1546 the emperor opened war against the Schmalkaldic League . The Protestant army, with 57,000 men, was superior to the armies of the emperor and his allies. However, the federal government was unable to show its superiority because it was not possible to agree on a coordinated approach. The numerical advantages were largely offset by the papal troops and units from the Netherlands. After the first successes of the Imperialists, the front of the enemy began to crumble. In the end, the emperor largely dominated Upper Germany. Then he was able to advance against central and northern Germany. In March 1547 the emperor marched in the direction of Saxony to look for the decision there. At this time it was problematic that the Council of Trent condemned the Protestant doctrine of justification as heretical. With this the hope of recognition of the council by the Protestants was finally ended. Politically, the Pope began to orientate himself again towards France, worried about imperial hegemony. The alliance with the emperor was terminated. By moving the council to Bologna , it was largely withdrawn from imperial influence. During the war itself, the emperor invaded Electoral Saxony. Charles V defeated Johann Friedrich von Sachsen in the Battle of Mühlberg (April 24, 1547). This and later Philip of Hesse were taken prisoner. The Elector of Saxony was later sentenced to death. The sentence was not carried out, but Karl granted the electoral dignity to Moritz von Sachsen. The Kaiser imprisoned both prisoners for years. The emperor used the opportunity during his stay in Wittenberg, allegedly to visit the grave of Martin Luther. The emperor had himself portrayed by Titian as a triumphant in 1549. Also in connection with his participation in the Schmalkaldic War, Charles V enforced a patrician constitution ( Hasenrat ) in the imperial cities in Upper Germany instead of the one dominated by guilds .

Armored Reichstag

Karl intended to use the victory for his goals. The so-called armored Reichstag met in Augsburg between September 1547 and May 1548. This was so named because the city was occupied as a member of the Schmalkaldic League and numerous regiments, mainly from Spain, were gathered around the city as a demonstration of imperial power. The Reichstag dealt with questions of imperial reform as well as the problem of religion. The emperor prevailed with his ideas for the restoration of the Imperial Court of Justice. The costs had to be borne by the imperial estates, while the emperor was given the right to fill vacancies. A chamber court order was also adopted, which essentially lasted until the end of the empire. Particularly central to Karl was the formation of an alliance of imperial estates for external warfare and internal peacekeeping. Above all, the electors resisted the imperial draft. When Karl realized that he couldn't get his way, he gave up the project.

With the Burgundian Treaty of June 26, 1548, the position of the Habsburg Netherlands was reorganized: Charles removed some territories that had previously belonged to the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Empire from this and added them to the Burgundian Empire ; thus the 17 Dutch provinces, which were under Charles's direct rule, were raised to a constitutional unit. Against the obligation of continuous protection by the empire, the Burgundian Imperial Circle was withdrawn from the jurisdiction of the Imperial Chamber Court. In return, the district should pay significantly higher realm contributions to the state treasury than the electors, for example to provide financial support in the fight against the Turks; In reality, however, the aid funds were significantly lower.

The central theme, however, was the question of religion. Initially it was about the recognition of the council by the evangelical estates. Among other things, the emperor promised safe conduct for the Protestants to the council. The emperor managed to convince the majority of the estates of his council resolution. He had thus achieved a central goal of the Schmalkaldic War. The realization, however, depended on the concession of the Pope. However, due to conflicts in Italy, the relationship between the emperor and the pope had deteriorated significantly, so that no support for Karl's council plans was to be expected from this side.

Against this background, the search for a provisional solution to the religious problem in Germany became more important. The emperor had previously commissioned a group of Catholic theologians to work out reform proposals and asked for conditions to be formulated for the Protestants to be tolerated. However, these drafts were so anti-Protestant that they could not provide a basis for a solution and the emperor had no viable concept. He was therefore forced to set up a committee made up of representatives from both camps to look for compromises. The committee turned out to be unable to work. In the meantime, a commission, in which, in addition to compromising Catholics, the Protestant theologian Johannes Agricola was also involved, had worked out a new proposal. This compromise envisaged, on the one hand, the admission of the laity's chalice and the recognition of already married priests and also took up other aspects of the Reformation doctrine, but otherwise called for the return of the Protestants to the old church.

The Augsburg Interim enforced by Karl failed in practice. The Catholic estates refused to implement the provisions. There were hardly any Catholic priests left in the Protestant areas, and worship services were avoided where they were. When the emperor tried to force Spanish soldiers to implement the resolutions, this caused violent displeasure. The "cattle Spanish servitude" became a well-known catchphrase. The anti-imperial opposition claimed to fight for the preservation of “German liberty”. The imperial estates found support from the new French King Henry II.

Princes' uprising (1552–1555)

The imperial superiority after the Schmalkaldic War and the displeasure over the attempt to solve the religious question from above sparked opposition movements among the imperial estates. Its engine was initially Hans von Küstrin . He planned to build a large anti-imperial and pro-evangelical covenant. Various imperial estates joined this. The leadership of the movement passed to Moritz von Sachsen, who had changed to the camp of Charles's opponents. The growing federation wanted to defend the evangelical cause and free Landgrave Philip of Hesse. Later, the freedom of the estates was also mentioned as a reason for war. The federal government allied itself with Henry II of France. In the empire there was a so-called prince uprising . The preparations were not completely hidden from Karl, but he did not react until the movement was already on its way. In February 1552, Henry II marched into Lorraine with an army of 35,000 men and occupied the Hochstifte there, which belonged to the empire. Shortly afterwards the royal army marched into the Austrian hereditary lands and came close to Karl, who was staying in Innsbruck. In addition, Albrecht Alkibiades waged war on his own against the Franconian Hochstifte and against Nuremberg. The enemy army advanced as far as Tyrol . Charles' situation was at times desperate. He lacked money and troops, the connection to the Netherlands was broken, he had no allies in the empire and even his brother Ferdinand did not confess to him clearly. Charles's policy of tough hands against the Protestants had thus failed. He had to enter into negotiations with the opponents. Ferdinand negotiated with the princes in Linz. In addition to various other conditions, the princely demands also included a permanent religious peace. Ferdinand was ready to accept most of the demands. Karl played for time. But soon the opponents marched into Innsbruck and the emperor had to flee to Villach . Negotiations were resumed in Passau. The emperor was still trying to resist. But Catholic imperial princes and even clergy princes pushed for a lasting religious peace that would also secure their existence. Ferdinand, too, urged the emperor to give in to the Ottoman threat. Based on the troops that had been gathered in the meantime, Karl introduced various changes that endangered the entire negotiations. Even if the princes had not achieved all of the war aims, the benefits to them were considerable. The core of the Passau contract was a return to Nuremberg decency. The interim was thus effectively eliminated. The next Reichstag should then decide on the question of religion. Charles's successes in the Schmalkaldic War were thus wasted. Karl now intensified the war against France for the liberation of the Lorraine Hochstifte. (see above) He allied himself with Albrecht Alkibiades. This collaboration with a peace-breaker severely damaged Karl's reputation. After the inglorious end of the campaign to Lorraine, Alkibiades began again to take action against the Franconian high monasteries. This triggered the Markgräflerkrieg . Above all, Ferdinand and Moritz von Sachsen took action against Alcibiades.

Religious Peace of Augsburg (1555)

After the failure of the campaign against Metz and the Passau Treaty, the emperor had largely given up on imperial politics and withdrew to Brussels. However, the marriage of his son Philip to Maria, the heiress of England, opened up new dynastic perspectives and the prospect of further encircling France. The business in the empire again essentially led the brother Ferdinand.

The emperor hesitated for a long time to convene the Reichstag agreed in the Passau Treaty. When he decided to do so, he immediately made it clear that it was not he, but Ferdinand who should be in charge. He did not want to be responsible for any likely concessions made to Protestants. However, the Reichstag of Augsburg was opened in 1555 in the name of the emperor. Except for the preparation of the proposition, Karl did not take part in the negotiations, especially on the religious question. Against Charles's concerns, the Augsburg Religious Peace was concluded on September 25, 1555 . He recognized the Lutheran variant of Protestantism. The imperial estates, with the exception of the spiritual territories, were granted the right of free choice of religion ("cuius regio, eius religio"). In addition, a reform of the chamber court order and an enforcement order for rural peace were resolved.

Shortly before the end of the Reichstag, one of the imperial councilors appeared at Ferdinand's and announced the emperor's abdication in favor of Ferdinand during the Reichstag, so that the imperial farewell to the religious peace would not be published in Karl's name. This meant an admission of the failure of his policy. However, the mission of the envoy came too late, so that the imperial farewell was issued in the name of Charles. Ferdinand sent the messenger back to Brussels with the request that his brother reconsider the decision. In fact, it was still some time before the abdication, but the emperor had already made up his mind to resign.

Clarifying the succession had occupied Karl for a long time. The Spanish inheritance would go to his son Philip. The succession in the empire was more complicated. Karl wanted Ferdinand to follow Philip in the empire as well. In Augsburg there were negotiations about it between Karl, Philipp and Ferdinand. The latter has contradicted these plans. Ferdinand's son Maximilian also disagreed with this. Maria of Hungary tried to mediate. It was finally agreed that Ferdinand should help Philipp to be elected Roman-German king. Philipp, in turn, was to follow Maximilian. In addition, Philipp was supposed to marry a daughter of Ferdinand. This plan of Spanish succession failed. In September 1555 the decision was made to divide the possessions. The Spanish line also got the Netherlands and the Italian possessions. The Austrian line received the hereditary lands, Bohemia, Hungary and the claim to the imperial crown.

Control of literature and printing in the individual territories of his rule

Charles V took measures to censorship of printed products in the Kingdom of Spain from its predecessors. Because already under the Catholic Monarchs in 1502 an ordinance had been decreed that forbade a book to be printed without the prior license of the Royal Council, Consejo real or equivalent. These were the Presidents of the Courts of Justice, Audiencias in Valladolid and Ciudad Real, the Archbishops and Bishops in Toledo, Seville, Granada, Burgos, Salamanca and Zamora. This control also applied to imported books. Already in 1546 Charles V had commissioned members of the University of Leuven to compile an index of books to be banned. This indexed list of books was available to the Spanish Inquisition . It was adopted and extended to use independently of the Roman index Librorum Prohibitorum . In 1554, Charles V and his son Philip II tightened the censorship ordinances by reducing the number of admissions offices and making the criteria more stringent. Incidentally, Bibles in one of the vernacular languages ( Spanish Bible translations ) were also subject to censorship .

In the course of the Worms Reichstag in 1521 , Charles V not only banned all of Martin Luther's writings , but also ordered that: