Orient express

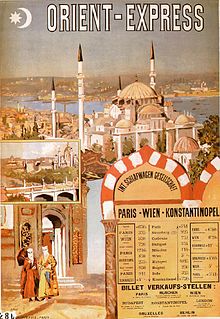

The Orient-Express was originally a luxury train of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits (CIWL) composed only of sleeping and dining cars , which first ran from Paris to Constantinople (since 1930 Istanbul ) on June 5, 1883 . Since the destination could not yet be reached continuously by rail, ferry and ship connections had to be used first. From 1890 there was a continuous connection via southern Germany, Vienna , Budapest and Sofia to Constantinople. Often referred to as the king of trains and the train of kings , the train was the core element of a whole system of luxury trains, which were mainly used to connect Paris and the canal ports to various destinations on the Mediterranean, Central and Southeastern Europe .

After the First World War , the Orient-Express ran to Bucharest , the connection between Paris and Istanbul was taken over by the Simplon-Orient-Express via Milan , Venice and Belgrade , which was also often referred to as the Orient-Express . After the Second World War , the luxury train type was abolished in 1950 and the trains were converted into normal express trains , which kept the name Orient in their names. The last continuous connection between Paris and Istanbul was the Direct-Orient , which was discontinued in 1977. From 2002 the train route called Orient-Express only ran to Vienna and began in Strasbourg instead of Paris from June 2007 until it was completely discontinued in December 2009.

Since the 1970s, various providers have offered special and tourist trains with restored old CIWL wagons , which derive their names from the historic Orient Express. The Orient Express has also become known as a setting in film and literary classics, especially through Agatha Christie's crime novel Murder on the Orient Express .

history

Until the First World War

prehistory

With the growing together of the railway networks, which were initially isolated in the European countries from around 1850, there was a need for international train connections without changing at border stations . There was also a growing interest in comfortable trains, such as those introduced in the United States by George Mortimer Pullman . Georges Nagelmackers , who had got to know Pullman's luxury trains in the USA, had been trying to introduce sleeping cars on European railways since 1870 .

Independently of this, the national railway administrations began to introduce cross-border express trains. The earliest known continuous train connection along the route of the later Orient Express is a train running between Paris and Vienna in 1867, which took two nights and a day for this route when it left Paris in the evening. The connection was in high demand after the temporary interruption caused by the Franco-German War of 1870/71 and was one of the first connections on which Nagelmackers began to realize his idea of a European luxury train network.

Establishment of the CIWL and establishment of the Orient Express

Nagelmackers founded the Compagnie de Wagons-Lits on October 4, 1872 , which soon signed the first contracts for sleeping cars between Ostend and Cologne , Ostend and Berlin as well as Vienna and Munich with the respective railway companies . Lack of money soon forced Nagelmackers to accept American investor William d'Alton Mann into the company and, after three months, to transfer her to Mann's Railway Sleeping Carriage Co. Ltd. rename it. Mann and Nagelmackers succeeded in setting up the first sleeping car route from Paris to Vienna in 1874. The cars were carried in normal express trains, then known as courier trains . In 1876 Mann had lost interest in the continental sleeping car business and Nagelmackers was able to pay him off. On December 4, 1876, he founded the still existing Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits (CIWL) in Brussels , the main shareholder of which was the Belgian King Leopold II . The CIWL quickly began to expand its network of sleeping car courses.

In the Ottoman Empire , the Compagnie des Chemins de fer Orientaux founded by Baron Maurice de Hirsch (mostly referred to as Orientbahn in the German-speaking area ) started building lines from Thessaloniki and Constantinople to develop the European part of the Ottoman Empire and the aim of a connection in the Ottoman Empire started on the European rail network. The Principality of Bulgaria , founded at the Berlin Congress in 1878 and nominally still subordinate to the Ottoman Empire, had to take over the construction of the Orientbahn routes as part of the congress agreements. Romania and Serbia , which were able to achieve complete sovereignty at the Berlin Congress, also built rail lines with the aim of creating connections with Central Europe. In 1878 the first CIWL sleeping car course was introduced from Vienna via Budapest, Szeged with the already existing Tisza bridge and Temesvár to Orșova , where there was a connection to Danube ships.

The good business development of CIWL and the growing rail network in the direction of the Balkans led Nagelmackers to develop plans for a train composed entirely of CIWL wagons. The participating state railways along the Paris – Vienna route had also recognized that there was a need for separate trains. Corresponding plans they discussed for the first time at the International Timetable Conference in 1878. In 1882 it was agreed to use such a train and from October 10th to 14th of the same year a Train de Luxe d'Essai ran for the first time as a pure sleeping car of the CIWL from Paris to Vienna and on a trial basis back. The CIWL used one of their first dining cars here , after they first used such cars between Berlin and Bebra in 1880 . The train reached average speeds of around 48 km / h on the outward and return journey and was three to four hours faster than the express trains used until then. It was therefore also known as the Train Eclair (German: Blitzzug). Due to this success, Nagelmackers was able to conclude the necessary contracts for the Orient Express with all participating railway companies in February 1883.

Participating railways were:

- the Chemin de Fer de l'Est

- the imperial railways in Alsace-Lorraine

- the Grand Ducal Baden State Railways

- the Royal Württemberg State Railways

- the Royal Bavarian State Railways

- the kk state railways (kkStB)

- the priv. Austro-Hungarian State Railway Company (StEG) and

- the Căile Ferate Române (CFR)

Initially, a train run from Paris to Giurgiu was agreed , which ran twice a week. From Giurgiu to Constantinople the connection was made with a Danube ferry to Ruse , a train of the Orientbahn to Varna and finally a steamer of the Austrian Lloyd . The CIWL was responsible for the provision of the entire fleet, which should consist of at least two sleeping and baggage cars as well as a dining car. Equipping the cars with gas or electric lighting, steam heating and Westinghouse brakes was also regulated . The wagons had to be approved by specialists from Chemin de Fer de l'Est and the Alsace-Lorraine Reich Railroad. The tariffs were also set; a first-class express train ticket and a 20% surcharge for the sleeping car had to be paid.

For the first time, the Orient Express, initially referred to as the Express d'Orient , drove eastwards from Gare de l'Est in Paris on June 5, 1883 as a luxury train of the first class of carriage . The new wagons with bogies ordered by the CIWL were not yet available, so that most of the wagons were still three-axle. Only one sleeping car of the CIWL was already equipped with four axles with bogies. Nagelmackers therefore initially decided not to have a major inauguration, which only followed when the new sleeping and dining cars with bogies built by CIWL's own workshops and the Munich wagon factory Josef Rathgeber had been delivered. The travel time from Paris to Constantinople was 81 hours and 40 minutes.

On October 4, 1883, the festive departure for the official inauguration trip took place at the Gare de l'Est, to which Nagelmackers had invited various press representatives, including the well-known journalists Henri Opper de Blowitz and Edmond About , in addition to representatives of the railway companies involved and the countries passed through . Both published enthusiastic reports about the journey, which contributed significantly to the success of the Orient Express. In the countries passed through there was local food and folklore performances, in Romania King Carol I received the travelers in Peleș Castle .

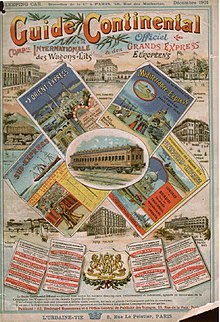

Due to the high demand, the Orient Express was already being operated daily between Paris and Vienna from June 1, 1884. After this successful introduction of its first luxury train, the CIWL added its name and from that year on was called Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits et des Grands Express Européens . After the railway line between Belgrade and Niš was completed in Serbia in 1884 , the Orient Express ran once a week from Budapest to Niš. From Niš there was only an arduous connection with horse-drawn carriages to Sofia and on to Belove . From there, trains of the Orientbahn went to Constantinople. In 1887, after the gap between Serbia and the Saloniki – Skopje line of the Orientbahn had been closed, the journeys ending in Niš were extended to what was then Ottoman Saloniki.

Continuous rail connection to Constantinople

The Bulgarian State Railways finally completed the line from Belove to the Serbian border near Dimitrovgrad (then Zaribrod ) in 1888, where there was a connection to the line to Niš, also built in 1888. From August 12, 1888, the Orient Express ran continuously via Budapest , Belgrade and Sofia to a temporary train station in Constantinople. This was replaced in 1890 by the new construction of the Müşir-Ahmet-Paşa station , the Sirkeci station . The travel time to Constantinople was reduced by over 14 hours compared to 1883.

In addition to the trains to Constantinople, which now run twice a week, a wing train to Bucharest continued to run once a week. Despite the personal efforts of Nagelmackers in 1888, the CIWL could not prevent an express train (conventional train ) from running every day between Belgrade and Constantinople in addition to its luxury train , which carried all three classes and thus offered an inexpensive alternative to the Orient Express.

Further development until 1914

The CIWL rapidly expanded the network of its luxury trains after the successful introduction of the Orient Express. At the same time, she tried to make the Orient Express more attractive. In Constantinople, she built the luxury hotel Pera Palace for her customers , which was supposed to ensure an appropriate stay for passengers on the Orient Express. With short stops at the border and few stops, the Orient Express was over 18 hours faster than the alternative connection with normal express trains on the entire route from Paris to Constantinople in 1914 in the last timetable before the start of the First World War. However, high speed was not the only thing required. In order to do justice to the increasing tourism in the Salzkammergut , the train, which had been running on the shortest route between Munich and Linz via Simbach am Inn since 1883, was carried over the longer route via Rosenheim and Salzburg from 1897 .

The Orient Express was soon supplemented by various through carriage runs and feeder trains. From 1894 the Ostend-Wien-Express, also set up as a luxury train by the CIWL, operated as a feeder with a coordinated timetable so that passengers from London could reach the Orient Express with a change in Vienna. There were also feeder trains via Calais and Paris, but in Paris they required a cumbersome change of stations. The Club Train luxury train with saloon cars between Calais and Paris (as well as a British equivalent between London and Dover ), introduced by CIWL on the occasion of the Paris World Exhibition in 1889 , had to be discontinued in 1893 due to insufficient demand. Instead, the Ostend-Wien-Express and the Orient-Express ran together daily from May 1, 1900 from Wien Westbahnhof to Budapest. From Budapest the Orient Express drove twice a week to Bucharest and on over the King Charles I Danube Bridge opened in 1890 near Feteşti to Constanța , where there was a ship connection. On three other days of the week the route via Sofia to Constantinople was served. However, there were repeated connection problems due to delays and until 1909 both trains were only listed as connecting connections in the timetables, although the through car connection was retained. From 1911 onwards, the number of journeys to Constanța and Constantinople was increased by one more journey per week.

The decisions about the route and number of trains were often politically controversial. The states involved and their railway companies often fought violently to get the lucrative connections over their routes. The Belgian SNCB , for example, tried to prevent direct cars from other stations on the Channel coast to Vienna in competition with Ostend, while Austria-Hungary opposed all plans of the CIWL to set a luxury train beyond Trieste on a significantly shorter and compared to the Orient Express to lead the capitals Vienna and Budapest immediately through the Danube Monarchy. Political disputes between neighboring states also played an essential role. In view of the tense relations between Hungary and Romania, the Hungarian State Railways , which in 1891 had taken over the Hungarian lines of the Austro-Hungarian State Railway Company (despite its name, private), vehemently opposed further trains to Romania from the beginning.

The CIWL had driven some of its first sleeping and dining cars on Prussian routes until the Prussian State Railways ended their contractual relationships with the CIWL in 1884 after taking over the previously private railways. Since then, the Prussian State Railroad Administration has rejected the use of trains and wagon courses from the CIWL, and the establishment of the Nord-Express was only achieved by CIWL in 1896 after eleven years and by taking advantage of the personal relationships between the various European ruling houses. A luxury train from Berlin to Constantinople was therefore only possible in 1900 . Previously there were only trains and through coaches between Berlin and Vienna or Budapest. On April 27, 1900, the first direct Berlin-Budapest-Orient-Express took place, which initially ran daily, but soon only ran twice a week. In 1902 the train was stopped again due to low demand. In 1906, the Orient Express briefly received a direct sleeping car from Calais to Vienna, which was also soon discontinued. These frequent changes showed that the real transport significance of the luxury trains was comparatively low, even if the CIWL made a profit with its trains, sleeping and dining cars. No exact statistics are available, but the Orient Express of the pre-war period is said to have been profitable with 14 passengers.

In the first World War

The First World War cut the train route with its fronts and the Orient Express had to be stopped. The French-dominated CIWL was a thorn in the side of the Central Powers , so they operated to replace it. As a replacement and deliberate competition, the Balkan train operated by MITROPA was introduced between Berlin and Constantinople on January 15, 1916 , with partial use of the CIWL wagons that had been confiscated and previously used on the Orient Express. Part of the train ran from Berlin Anhalter Bahnhof via Dresden, Prague and Vienna, a second part via the Berlin Stadtbahn , Breslau and Oderberg . In Vienna, cars from Munich and from time to time Strasbourg were provided. Both parts of the train then went together from Galanta . The train reached Istanbul via Budapest, Belgrade and Sofia.

The Balkan suit led through the militarily occupied Serbia and thus connected all four allied Central Powers, the German Empire , Austria-Hungary , Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire . This train also carried what was then the second class and normal seated cars. When Bulgaria left the World War, the Balkansug operated for the last time on October 15, 1918.

Between the world wars

After the end of the war, the CIWL received its confiscated wagons back, provided they had survived the war. In order to maintain a connection between France and the newly established Central and Eastern European states of the Cordon sanitaire , a so-called Train de luxe militaire was set up with wagons of the CIWL from February 1919 , which was reserved exclusively for high-ranking Allied soldiers and politicians. It was not taken on the former route of the Orient Express through southern Germany, but via Switzerland and the Arlberg Railway to Vienna and on to Warsaw. Through coaches to Prague were deposited in Linz.

As a result of the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and the accompanying negotiations, the main axis of traffic to Southeast Europe was shifted from the previous route of the Orient Express via southern Germany and Vienna to the connection via the Simplon Tunnel , northern Italy and Trieste, the Simplon Orient Express . However, the increasing demand soon led to the re-establishment of a luxury train connection on the classic route of the Orient Express. Its brief relocation to the Arlbergbahn during the occupation of the Ruhr in 1923 finally resulted in the establishment of another luxury train through the Alps, which from 1932 was called the Arlberg-Orient-Express .

In the 1920s, the trains and through coaches changed several times, the CIWL sometimes tried out other train routes and names. This included trains such as the Ostend-Wien-Express (also known as Ostend-Wien-Orient-Express or Ostend-Orient-Express ) or the Karlsbad-Express . A whole system of luxury trains with various carriage routes was built around the Simplon Orient Express. From 1932 on, there was a system of three different train routes, all starting from Paris, which lasted until the beginning of the Second World War .

The Simplon Orient Express

At the same time as the Paris Peace Conference, the Entente Powers were negotiating the reintroduction of the Orient Express. There was agreement that the defeated states, especially the German Reich, should be excluded from important traffic to the Near East and the Balkans. On August 22, 1919, a corresponding convention was signed between France, Belgium, Great Britain, Italy, Romania, Greece and Yugoslavia, which for ten years excluded all direct train or wagon runs through Germany and beyond Vienna to south-eastern Europe. The Netherlands and Switzerland, which remained neutral during the World War, also acceded to the convention. The CIWL was initially not convinced of the success of the train. Under pressure from the Entente Powers, it took over management of the company, but announced that it would demand compensation for the expected losses.

Even before the conclusion of the convention, the Simplon-Orient-Express ran for the first time on April 11, 1919 from Paris via Switzerland , the Simplon Tunnel and Milan to Trieste . Connecting trains secured the connection via Zagreb to Belgrade. In doing so, the train bypassed not only defeated Germany, but also Austria and Hungary. From January 1920 the Simplon-Orient-Express drove continuously to Belgrade and in the summer of the same year to Istanbul and by coach to Bucharest. A predecessor of this train operated as the Simplon Express from 1906 through the tunnel that went into operation that year to Milan and later to Venice, most recently from 1912 to Trieste. As already mentioned, a continuation in the direction of the Balkans had been rejected by Austria-Hungary before the war.

The Simplon Orient Express also began its journey in Calais from 1920, but mostly in combination with other CIWL trains. A year later, the train also received a sleeping car to Athens , which for the first time had a rail connection to Western Europe without changing trains. In order to guarantee a connection to the train for Belgium, a through car was introduced from Ostend via Brussels and Strasbourg to Istanbul, which reached the Simplon-Orient-Express in Milan. This through car drove through a total of nine countries, but was discontinued after a few years in 1925. The attempt of a train part introduced in 1920 from Bordeaux and Lyon to Milan had already been terminated in 1921 due to lack of demand. In 1927 the CIWL set up the Anatolia Express as a sleeping car train between Istanbul and the new Turkish capital Ankara , the timetable was designed so that passengers on the Simplon Orient Express with ships under the direction of CIWL could get direct connections at Istanbul Haydarpaşa station . From 1930 there was also a connection to the Taurus Express to Aleppo and Rayak , which was also operated under the direction of the CIWL.

The Simplon Orient Express was the only train in the Orient Express system that ran daily during the interwar period. In Paris he drove in the evening from the Gare de Lyon , where the through coaches coming from Calais with the Flèche d'Or were delivered. He reached Brig via Lausanne and at night drove through the eponymous Simplon tunnel. The next morning he traveled to Trieste via Milan and Venice . After Trieste, the second night route began, leading via Ljubljana , Zagreb and Vinkovci to Belgrade. In Vinkovci, the part of the train to Bucharest was suspended, which was led there, bypassing Hungarian territory via Subotica and Timișoara . Carriages through to Constanța, as they existed before the war, were no longer introduced. As a substitute reversed from 1933 CIWL train with Pullman and dining cars from Bucharest to Constanta, who after Romanian King Carol I as Fulgur Regele Carol I was called.

The main part of the train in Belgrade was reinforced by through coaches of the Orient Express as well as from Berlin, Ostend or Prague, which came with a night train from Budapest, while the coaches to Athens were handed over to a normal express train. The Simplon-Orient finally reached Turkey via Sofia and Svilengrad , after the third night the Istanbul Sirkeci train station was reached the next morning .

Parallel to the Simplon-Orient-Express, a normal express train from Paris to Trieste operated as Direct Orient from 1921 , which also carried seating cars.

When it was first introduced, the Simplon-Orient-Express was on the road one night and one day longer than the Orient-Express in the last peace timetable of 1914 due to the run-down routes after the war and the time-consuming passport, customs and currency controls that were considerably expanded compared to the pre-war period In 1930 it was almost back to 1914 driving time. In the following years it was possible to accelerate it further and in 1939 the Simplon-Orient only needed about 56 hours, a travel time that was not reached again until 1974 for the Paris-Istanbul route after the Second World War.

The Orient Express

The Treaty of Versailles stipulated in Article 367 that international trains were to be transported by the Deutsche Reichsbahn in accordance with the requirements of the victorious powers and at least at the speed of the best domestic German trains on the respective routes. Taking advantage of this clause, the train de luxe militaire was released for normal travelers in 1920 and guided on its conventional route via Strasbourg and Munich. To distinguish it from the Simplon-Orient-Express, the train across southern Germany was initially called the Boulogne / Paris / Ostend-Strasbourg-Vienne-Express . One wing of this train ran from Strasbourg as the Boulogne / Paris / Ostend-Prague-Varsovie-Express to Warsaw. After direct sleeping cars Paris-Cologne-Berlin-Warsaw were reintroduced on the basis of Article 367 from 1921 onwards, the use of the Warsaw train section declined rapidly and the train route was limited to Prague. From the summer schedule of 1921, the train got its traditional name back and was extended from Vienna via Bratislava and Budapest to Bucharest. However, deviating from the pre-war route, it no longer ran via Szeged and Timișoara , but via Arad , as the old route ran on a short section through Yugoslavia since the end of the war. In accordance with the 1919 convention, there were no cars from Paris to Istanbul; a sleeping car only ran for a short time from Munich to Istanbul.

In January 1923, the Orient Express through Germany was discontinued due to the occupation of the Ruhr and relocated to the Arlberg line. It was not until November 30, 1924 that the Orient Express ran through southern Germany again , but only by car to Bucharest. It was not until 1932, two years after the convention concluded in 1920, that the Orient Express received a Paris-Istanbul sleeping car again, which, however, only ran to Belgrade from 1933 to 1935 due to weak demand.

The Orient Express on the classic route via Strasbourg – Stuttgart – Munich only ran on three days of the week, in the last timetable before the war on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. Despite the poor demand, the Deutsche Reichsbahn applied at the 1938 timetable conference to expand the Orient Express by introducing daily traffic. The CIWL and the other participating railway companies rejected this, however. The timetable for this train, which runs from Gare de l'Est at around 8 p.m. , has been the basis for almost all express train services in Central Europe for decades . Not only the French railways, but also all other Central European rail administrations based themselves on the timetable of this train. Unlike the Simplon-Orient-Express, the Orient-Express did not get its through coaches from Calais in Paris, but only in Châlons-sur-Marne , where a normal express train had brought them from the Channel coast. The Orient-Express reached Stuttgart via Strasbourg and Karlsruhe, where early morning coaches to Karlsbad and Prague were detached as the Karlsbad-Express . Before the First World War, this connection was served by its own train directly from Paris.

Around noon, the Orient-Express reached Linz after its journey via Munich and Salzburg , where through coaches from the Ostend-Vienna-Express were delivered. Via Wien Westbahnhof and Bratislava (only until 1938, from then directly via Hegyeshalom ) the train reached Budapest Ostbahnhof in the evening . There the through coaches to Istanbul switched to a normal night train to Belgrade, where they were added to the Simplon Orient Express. The main part of the train drove during the night via Szolnok , Arad and Sighișoara to Bucharest, which it reached around noon.

The Arlberg-Orient-Express

After the Orient Express returned to southern Germany in November 1924 after the Ruhr crisis had ended, the CIWL introduced the Suisse-Arlberg-Vienne Express on the diversion route . Both the increasing tourism in the Alps and the connection to the banking metropolis of Zurich had generated good demand for the rerouted Orient Express, which now justified a permanent connection. From 1926 onwards, the Suisse-Arlberg-Vienne-Express also had 2nd class sleeping car spaces in Switzerland and Austria and was therefore no longer referred to as a luxury train, but simply a sleeper train . In 1927 the train received a through car to Bucharest. In the summer of 1930 he was given a Pullman saloon car between Basel and Vienna, but it was not profitable and disappeared from the train set after the end of the summer schedule. From the summer schedule of 1931, it was renamed the Arlberg-Orient-Express to Budapest. At the same time, it was given the luxury train type again, as 2nd class was introduced in the other luxury trains of the CIWL due to the global economic crisis and the decreasing capacity utilization. The managing administration was the Chemin de Fer de l'Est until 1932 , from then on the SBB.

In addition to the Orient Express , the Arlberg-Orient-Express also ran three days a week at the same time from the Gare de l'Est, on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. At the same time, since 1925 it operated as an Oberland-Express through coach to Interlaken and as an Engadin-Express through coach to Chur . The train kept these branches even after it was renamed. Like the Orient-Express, the Arlberg-Orient-Express ran through coaches from Calais, which were delivered in Chaumont . After the night journey via Basel , Zurich-Enge and Sargans , the train reached the eponymous Arlbergbahn the next morning . Even before the war, tourism to Austria was of great importance, so the train served important tourist destinations such as St. Anton am Arlberg and Kitzbühel . Salzburg was reached via the Giselabahn .

From the winter timetable in 1936, the Tirol-Express also ran on the days when the Arlberg-Orient-Express was not running , but only between Paris and Salzburg. There was thus a daily luxury train from Paris or the Channel coast to the Tyrolean winter sports resorts. A major trigger for the increased demand and the introduction of the Tirol Express was the winter vacation that the then Prince of Wales and later King Edward VIII spent in Kitzbühel in 1935.

Unlike the Orient-Express, the Arlberg-Orient-Express did not take through coaches from the Ostend-Wien-Express. The Arlberg-Orient-Express ran like the Orient-Express via Vienna Westbahnhof to Budapest, but it ended there and also traveled differently via Hegyeshalom and not via Bratislava. He only took through cars to Athens and Bucharest (via Oradea , not Arad), but not to Istanbul. An application by SBB to drive a sleeping car to Istanbul was unsuccessful at the 1934 timetable conference.

In World War II

With the outbreak of the Second World War, the continuous Orient-Express via southern Germany and the Arlberg-Orient-Express via the then German Austria were discontinued. The Orient Express ran on the Munich – Bucharest route until May 1940; there was a through car from Zurich for travelers from Switzerland. Mitropa took over the management. The Simplon-Orient-Express also ran continuously until shortly before Italy entered the war towards the end of the western campaign in May / June 1940. He remained on the Lausanne – Istanbul section until April 1941.

In view of the state of war it was remarkable that the Simplon Orient Express carried CIWL through coaches from Berlin from Belgrade until May 25, 1940. Between Belgrade and Istanbul, wagons from Paris and Berlin were united in one train, thus the capitals of two countries at war with one another.

From April 1941 - the exact date is not known - the CIWL had to stop the Simplon-Orient-Express on its remaining route after the start of the Balkan campaign . All courses in the German sphere of influence were to be ceded to MITROPA , which set up sleeping car runs from Berlin to Belgrade, Athens and Sofia and from Paris to Budapest via Munich and Vienna. The unofficial successor to the Orient Express was the D 148/147, which carried MITROPA sleeping car courses from Berlin via Vienna to Sofia and from Paris via Munich to Budapest. The CIWL remained active in Italy and Turkey and ran through coaches from Rome and Turin to Belgrade and Sofia until 1943. The connection to Turkey was only possible with a change in Sofia and at the border in Svilengrad. With Mussolini's fall in 1943, the CIWL carriage races ended and in 1944 MITROPA also ended its sleeping car races towards the Balkans.

After the Second World War

The consequences of the iron curtain

After the end of the Second World War, the Simplon-Orient-Express, the Orient-Express and the Arlberg-Orient-Express ran again, starting in September 1945. However, all trains also carried normal seating cars and were no longer considered luxury trains of the CIWL from 1950, but classified as normal F or D trains. In the 1970s, however, railway workers in southern Germany called the Orient Express colloquially as "Lux". The CIWL limited itself to the operation of the sleeping and dining cars. Initially, the Arlberg-Orient-Express was reintroduced from September 1945 and the Simplon-Orient-Express from November of the same year; the Orient-Express only re-connected Paris with Stuttgart , Munich and Vienna on April 1, 1946 .

All three trains could only gradually return to their previous routes, destroyed lines and bridges as well as the lack of coal prevented a quick return to the pre-war status. Added to this were the effects of the Greek Civil War and the consequences of the communist takeover in the Eastern European countries until 1949 . The Simplon-Orient-Express initially only ran between Paris and Venice, and only from 1947 could it run to Istanbul again. A direct connection to a train from Istanbul Haydarpaşa to Cairo was even planned after a continuous rail link between Turkey and Egypt had been completed in 1946. From 1947 the Arlberg-Orient-Express drove back to Bucharest and took a sleeping car to Warsaw. From 1948 the Orient Express also served its pre-war route from Paris to Bucharest.

The system of trains was supplemented from 1948 by the Balt-Orient-Express , which received the train route Stockholm – Belgrade. The Simplon-Orient through car to Istanbul took over from this train, but not as a continuous carriage run from Stockholm. In 1950, the Orient Express also introduced third class cars for the first time. From 1951 through cars from the Tauern Express were integrated into the system.

With the erection of the Iron Curtain , the demand for rail traffic to Eastern Europe fell rapidly. Complex border controls and foreign exchange regulations significantly reduced the number of passengers, only diplomats , who had fewer problems with border controls due to their passports, remained on the Orient Express trains as customers. CIWL also had to gradually renounce its operating rights in the Central and Eastern European countries. Only the sleeping car courses from Western Europe remained with the company. In accordance with the demand and the political development, the train routes of the Orient Express system were repeatedly changed in the 1950s and temporarily withdrawn to Vienna. From 1952 the Simplon Orient Express was diverted between Belgrade and Istanbul for several years, bypassing Bulgaria via Thessaloniki . It was not until 1954 that he returned to his normal route. In order to avoid problems with Bulgarian transit visas, there were still through coaches to Istanbul running via Thessaloniki for a few years. In contrast to the pre-war period, the Athens branch of the Simplon-Orient established in 1950 after the end of the civil war was much more important than the Istanbul wing train . From 1951 the Orient Express only ran to Vienna and only returned to its route via Budapest to Bucharest after the Hungarian uprising in 1956.

In 1960 the direct through coaches from Calais for the Simplon Orient Express were discontinued, only the through coaches for the Orient Express remained. In order to secure at least one connection, the Flèche d'Or was extended to the Gare de Lyon .

The end of the old Orient Express system in 1962

In 1961 the European Timetable Conference decided on a fundamental restructuring and thus the end of the previous system of Orient Express trains with its various through coaches. The Arlberg-Orient therefore ran for the last time in 1962, the Arlberg-Express remained as a normal night train between Paris and Vienna, without any further through coaches. The Direct-Orient Paris-Belgrade, which has been running again since 1950, took over the sleeping car courses to Istanbul from the Simplon-Orient-Express; the direct through cars from Calais to Istanbul that had been running until then were no longer available. There remained only two to three times a week sleeping car courses from Paris to Istanbul or to Athens. The remaining Simplon Express only ran to Belgrade. The Orient Express via southern Germany was shortened to Vienna, only from 1964 did it return to Budapest, from 1971 to Bucharest. Through coaches from Munich to Athens and Istanbul were run independently of the Orient Express on a separate train, which was called the Tauern Orient from 1966 . From Belgrade the Marmara-Express to Istanbul and the Athenes-Express to Athens took over the through coaches of the Direct-Orient and the Tauern-Orient as normal express trains .

A final special feature of the Arlberg Express from its times as a luxury train was the bypassing of the Zurich main station with a stop at Zurich Enge station . This saved the headache of changing the locomotive and shortened the travel time. From 1969 the Arlberg Express ran like the other long-distance trains into the hall of Zurich's main train station, so that a change of locomotive became necessary.

The last direct orient to Istanbul

Initially, the so-called guest worker traffic ensured a strong increase in traffic to Eastern Europe and the Balkans from around the mid-1960s , the railway companies responded by setting up additional trains and through coaches between Western Europe and the Balkans, from around 1963 with the Hellas Express . The existing trains were adapted to the initially increasing demand, the Direct-Orient often had a length of more than 500 m, which corresponds to around 19 to 20 cars. At the same time, however, the criticism of the increasing unpunctuality and the condition of the trains increased. Various attempts by the railways involved to improve the quality offered and to raise punctuality and comfort to a contemporary level failed. In 1969, the Deutsche Bundesbahn downgraded the Orient Express on its section from the F train to the express train. Since the beginning of the 1970s, the sleeping car courses have increasingly lost passengers to air traffic, with Direct-Orient the number of sleeping car travelers fell by 20% from 1972 to 1976. In 1972, the Munich – Istanbul sleeping car, which went from the Tauern-Orient in Belgrade to the Direct-Orient, was the last sleeping car route between Germany and Turkey.

With the Direct-Orient, the 13 railway and nine sleeping and dining car companies involved also failed to make it more punctual and more attractive, so operations had been in deficit since the early 1970s and the Direct-Orient acquired a reputation as the slowest international train. At the timetable conference in 1975 it was finally decided to end the continuous train service from Paris to Istanbul. The Direct-Orient ran for the last time on May 19, 1977 from the Paris Gare de Lyon to Istanbul, the entire train run was canceled. This last sleeper trip was booked out months in advance after the discontinuation became known, the last trip of the Direct-Orient took place with considerable media attention and was often perceived as the end of an era.

The direct connection Paris – Istanbul was replaced by a connection with the Venezia-Express from Venice to Belgrade. The Simplon Express from Paris to Belgrade also offered at least connections to Athens. In 1979 the Tauern-Orient between Munich and Belgrade also disappeared, the Hellas Express, the Acropolis and the Istanbul Express remained as trains from Central Europe to Athens and Istanbul. A brief attempt with the trains running as a pure sleeping and Liegewagenzug Attica bring from Munich to Athens from 1989 again a superior proposal to the rails, failed because of the outbreak of the Yugoslav wars . Initially, all trains from Central Europe to Turkey and Greece had to be diverted via Budapest, but gradually the continuous train service between Central and Southeastern Europe was finally stopped until 1993. Since then, passengers have had to change either in Belgrade or Budapest. Even after the end of the Yugoslav wars, there was no resumption of direct traffic.

The Orient Express from 1962 to 2009

The Orient Express, on the other hand, continued to run as a night train between Paris and Vienna via Strasbourg and Munich. From 1965 it was extended again to Budapest, a year later the Paris– Bucharest sleeping car was reintroduced, initially as a through car. As a continuous train to Bucharest from 1971 onwards, the Orient Express only ran in the summer schedule, in the winter schedule only through coaches ran from Budapest. The sleeping car courses to Bucharest operated by the CIWL remained in the timetable until 1991, and the Orient Express also ran a dining car for most of the years. The train last only ran three days a week between Budapest and Bucharest. In 1991, the train route to Paris – Budapest was shortened, and the last dining car between Stuttgart and Budapest was no longer available. In 1999 a sleeping car from Paris to Bucharest was introduced again, but not managed by the CIWL but by the CFR . In 2001, the CFR discontinued this sleeper run after it was last only driven twice a week.

As of the 2001 summer timetable, the Orient Express operated as EuroNight (EN) only between Vienna and Paris. From December 2002, after the Eurocity Mozart was discontinued, it was the only remaining direct connection between the two cities. For some time the train carried through cars from Vienna via Salzburg to Venice, which were, however, shown in the timetable as their own EN Allegro Don Giovanni .

For the small timetable change on June 9, 2007, the train run on the Vienna – Strasbourg route was shortened due to the start of traffic on the new TGV line between Paris and Strasbourg . In addition, the Austrian Federal Railways (ÖBB ) provided the rolling stock instead of the Société nationale des chemins de fer français (SNCF). From then on, the train was run independently by the ÖBB; in Germany, Deutsche Bahn AG tickets were only accepted against payment of a (reservation) surcharge. In addition, the train carried through coaches between Vienna and Amsterdam , which are run as a separate CNL Donau-Kurier train . These through coaches hung on the Orient Express to and from Karlsruhe. The through car group drove to Dortmund Hbf until December 8, 2007, and from December 9, 2007 these through cars drove to Amsterdam Centraal . Between December 9, 2007 and December 14, 2008, the train stopped in Wels Hbf, in contrast to Stuttgart Hbf was temporarily bypassed by the Stuttgart freight bypass. Instead of through coaches to Amsterdam, the pair of trains ran through coaches from Budapest to Frankfurt am Main from December 2008.

Until December 14, 2009, the Orient Express ran daily between Strasbourg and Vienna. With the discontinuation of this night train came the end of the scheduled Orient Express after 126 years. The train last consisted of sleeping, couchette and seating cars of the ÖBB and MÁV . The through coaches from Frankfurt to Budapest, which also included a dining car, were referred to as the independent EuroNight Danubius and run between Karlsruhe and Vienna together with the Orient Express.

Famous passengers

The King of Trains was nicknamed the Train of Kings because of the large number of royal passengers. The most famous passengers of the Orient Express include King Ferdinand I of Bulgaria, who, like his son Boris III. repeatedly led the locomotive of the Orient Express on the Bulgarian section. While his son had the necessary permissions as a train driver , this was not the case with Ferdinand I. His driving style allegedly led to repeated complaints from passengers.

Other well-known passengers from the high nobility were King Constantine I and Paul I of Greece, Prince Regent Paul of Yugoslavia , the Duke of Windsor , Archduchess Marie Valerie , Aga Khan III. and his son Aly Khan . As a shareholder in CIWL, Leopold II of Belgium was a regular passenger. Other rulers such as King Carol I of Romania had their court saloon car attached to the Orient Express. The CIWL and the railways involved had real problems due to the large number of court saloon cars when rulers and princes from all over Europe were on their way to London on the occasion of the funeral of King Edward VII in May 1910. Due to the permissible train load, the Romanian Crown Prince Ferdinand , for example, had to do without half of his planned six cars. After his dismissal in 1924, the last caliph , Abdülmecit II , also left Turkey on the Orient Express. Indian maharajas were among those passengers who liked to book an entire car. One of the stories about prominent passengers that can be found time and again in reports about the Orient Express is the legend that Queen Maria of Romania on the Orient Express assisted a fellow passenger in labor as a midwife during the birth of her child after no one else did Passenger saw able to do so. Her son, King Carol II , was also a regular on the Orient Express. He used it one last time when, on his escape in September 1940, he and his lover Magda Lupescu took several special wagons filled with art treasures and valuables to the Orient Express at the București Nord station (which at that time only drove as far as Italy due to the war ) hung.

Regular customers were also other nobles, politicians, diplomats, industrialists, bankers and artists. A particularly loyal passenger was the arms dealer Basil Zaharoff , who for 30 years always booked compartment No. 7 on the Orient Express and got to know his future wife in it. The German banker Carl Fürstenberg , who booked all the beds in his compartment , also had special requests . Other well-known regular passengers were the actress Sarah Bernhardt , the dancer Mata Hari , the English banker Sir Ernest Cassel , the future US President Herbert Hoover , who worked as a mining engineer in Europe before the First World War, and the oil magnate Calouste Gulbenkian . On his first trip on the run from an Armenian pogrom in Constantinople in 1896, he allegedly led his son hidden in a carpet with him.

After the First World War, the prominent clientele concentrated largely on the Simplon Orient Express. Eugenio Cardinal Pacelli, later Pope Pius XII. used it for a visit to south-eastern European dioceses, politicians like Pierre Laval , Sir Robert Vansittart or Maurice Hankey took the Simplon-Orient-Express to diplomatic conferences. Journalists, artists and writers like Elsa Maxwell , Arturo Toscanini and F. Scott Fitzgerald were also regular customers. There were also representatives from the opposite political camps - for example, in 1937 the German Foreign Minister Konstantin Freiherr von Neurath took the Simplon-Orient-Express to Bulgaria, like the Marshal of the Soviet Union Mikhail Nikolajewitsch Tukhachevsky heading west a year earlier . But the Orient-Express via southern Germany and the Arlberg-Orient-Express also saw many prominent passengers in the interwar period. A curious anecdote was the trip of the violinist Jascha Heifetz , who consulted Sigmund Freud from the open car window during his stay in Vienna . After Austria's annexation, Freud and his family took the Orient Express from his hometown to emigrate to Paris on June 4, 1938, and from there to London with the Night Ferry . Unlike many emigrants and refugees of that time, he was largely unmolested thanks to the accompaniment of a member of the American embassy on the border in Kehl.

After the Second World War, the prominent clientele soon switched to aircraft. In addition to the last Romanian King Michael I , who went into exile on the Orient Express in 1948, Princess Gracia Patricia von Monaco and Brigitte Bardot were among the occasional users of the Orient Express in the 1950s .

Accidents and special events

The trains of the Orient Express system became known not only for their luxury and the audience from the European nobility and finance, but also for accidents and some spectacular incidents.

Accidents

The Orient Express and its wing trains were repeatedly hit by accidents. So there were derailments on April 9, 1910 at Vitry-le-François and on December 7, 1927 near Istanbul. In the railway accident in Pont-sur-Yonne , another express train hit the Simplon-Orient-Express in Pont-sur-Yonne on November 3, 1919 , killing 20 people and injuring over 100. In 1921 the train derailed in Romania and in 1924 the Istanbul part of the train collided with a freight train near Belgrade . On November 6, 1929, the Orient Express crashed into a stationary freight train near Vitry-le-François , killing the engine driver , the stoker and a conductor .

The most momentous accident was the railway accident in Istanbul on October 21, 1957. Shortly after Istanbul, the Simplon Orient Express collided head-on with a local train , killing 95 people and injuring 150.

Special events

The passengers of the opening train in 1883 had been advised by the CIWL to carry a weapon with them for safety reasons. Contrary to widespread fears about the insecurity of the Balkans and the Orient, there were no special incidents with the exception of an axis of the dining car that had already overheated between Ulm and Munich .

Unlike the opening train, the scheduled trains were repeatedly affected by disruptions to the train's run, armed events and criminal activity. As early as 1883 bandits had attacked a station on the route from Ruse to Varna, which the connecting train of the Orient Express used until 1888. In 1891 the Greek robber Athanasios derailed the train 100 km west of Constantinople, kidnapped four men and only released them after a ransom of 8,000 pounds sterling in gold had been paid. Since the abductees were German businessmen, even Kaiser Wilhelm II intervened in the efforts to get them released . The various Balkan wars led to weekly and month-long interruptions in the train run. A cholera epidemic in Turkey in 1892 also caused disruptions and, above all, a rapidly falling demand.

Since the 1920s, drug smugglers also used the Orient Express, which was to remain a side effect of the train until it was closed. In 1948, during the post-war chaos, a conductor estimated that 40% of passengers were black marketeers or with contraband. The troubled times after the end of the First World War also had an impact on the company. In 1924 a bridge in Hungary was blown up, the Orient Express could be stopped in time. On the other hand, the bombing of the connecting train of the Arlberg-Orient-Express to Budapest by the Hungarian railroad bomber Sylvester Matuska in 1931 had more serious consequences. In Biatorbágy the train from a bridge collapsed after Matuska the rails had blown up. 24 people died. The American dancer Josephine Baker , who was also on the train, survived the attack unharmed.

There were also complications because the Orient Express was preferred by diplomats. Shortly after the start of the Orient Express, the British government had one compartment per week booked with the CIWL for its King's messengers , who act as diplomatic couriers to transport mail to the various embassies and consulates . The French government also booked a permanent compartment for its diplomatic couriers. In addition to these official customers, agents and spies also liked to travel on the Orient Express. Since most agents stayed incognito as much as possible , serious incidents rarely occurred, and many spectacular cases found in the literature turned out to be legends or less dramatic events. The last known case occurred in 1950 when a US military attaché was found dead on the tracks in the tunnel under the Lueg Pass . It is assumed that he invaded by Soviet bloc agents, robbed and from the Arlberg-Orient-Express, which is now a normal express train was encountered was what rolled over him following features. The gradual construction of the Iron Curtain in the 1950s also repeatedly led to border closings and diversions.

The Orient Express was held up several times by natural events. Especially on the alpine routes used by the Simplon-Orient- and Arlberg-Orient-Express, mudslides and landslides led to the suspension and, in some cases, detours lasting for months. Drifting snow repeatedly brought him to a standstill. In 1907 the train between Constantinople and Edirne was blocked by snow for 11 days. This was repeated several times in 1929, the severe winter of 1928/29 not only resulted in significant disabilities in the Balkans, but also in Central Europe. The Simplon Orient Express was snowed in for five days this winter in Turkey near Çerkezköy , which inspired Agatha Christie to write her novel Murder on the Orient Express . In contrast, as far as is known, there was never a real murder on the Orient Express.

On the other hand, the Italian racing driver Carlo Abarth caused a sensation with a race against one of the Orient Express trains, which at the time was considered to be a cultural and technical peak performance. In 1934 he hit the Ostend-Orient-Express with his motorcycle team on a trip from Ostend to Vienna .

vehicles

The Orient Express quickly became popular because of its sleeping and dining cars and the comfort they offered, although the actual comfort offered did not always correspond to the reputation and legend that the luxury train soon acquired. The railway companies involved each used their most modern express train locomotives, but freight locomotives were also used in the war and post-war times.

dare

The CIWL had ordered new cars for the introduction of the Orient Express in 1883, but these had not yet been delivered when the first train started. From June 1883, the company therefore mainly used three-axle sleeping and dining cars. It was not until autumn of the same year that the new wagons with bogies delivered by Rathgeber in Munich could take over operation. First, the CIWL had individual vehicle series developed for each of its luxury trains. Some of these were supplied by various European wagon construction companies and some were built in CIWL's own workshops. From around 1910, the vehicle fleet was standardized and large series of a few vehicle types were produced. Until 1922, however, the cars were used in fixed circuits, only after that they were generally no longer used specifically for certain trains. While the sleeping and dining cars were all equipped with bogies and four or six axles from autumn 1883, the CIWL used two or three-axle luggage cars on the Orient Express until shortly before the First World War .

Just four years after the train was introduced, CIWL put a new series of vehicles into service for the Orient Express in 1887, and the wagons used changed frequently in the years to come. After 1890, the CIWL, like most Central European railway administrations, gradually introduced wagons with bellows , which enabled a protected and safe transition between the wagons. Until then, the cars had still had open boarding platforms.

As a rule, the Orient Express and the other luxury trains of the Orient Express system consisted only of sleeping, dining and luggage cars. The CIWL only used saloon and Pullman cars occasionally on sections of the route; otherwise, their use was limited to the Pullman express trains established since 1925 . Most attempts of this kind, for example on the scenic routes of the Arlberg-Orient-Express, turned out to be not profitable. The last time there was an attempt in 1949 was a Pullman car on the Basel – Vienna section. Normal seat cars of the railway companies, over whose routes the trains rolled, were only used after the Second World War. The sleeping and dining cars remained in the possession of the CIWL until 1971, after which they were transferred to the TEN pool of the state railways, the CIWL only took over the management.

From the mid-1880s to 1922, CIWL received all new wagons with the characteristic teak exterior cladding ; only some saloon and Pullman wagons not used on the Orient Express had a cream-colored window area. The last sleeping car series of this type were designated as type R , some older cars were converted to this type. All wagons were built with wooden bodies.

From 1922 onwards, the CIWL only procured sleeping cars with steel superstructures, the new color scheme of dark blue with gold lettering soon becoming typical for the entire CIWL fleet. From 1926 corresponding dining cars were also delivered. The company did not park the last teak wagons until after the Second World War, after they were only used in subordinate services.

The first series of blue all-steel wagons was designated Type S and was procured for the luxury train from Calais or Paris to the French Riviera , later called Train Bleu , according to the color . The Orient Express and the Simplon Orient Express received the blue coaches from 1926. Various series of the Type S were purchased; the coaches had four two-bed and eight single-bed compartments . With the global economic crisis , the CIWL had the second class introduce its luxury trains in order to remain profitable. From 1930 onwards, the type Z and Y cars, which were fully equipped with two-bed compartments, were also used. On the other hand, the Lx type, known from its operations in the Train Bleu and the various tourist trains such as the Nostalgie-Istanbul-Orient-Express and the Venice-Simplon-Orient-Express, with its particularly luxurious equipment, was not regularly used in the Orient before the Second World War. Express system used. Type Lx or substructure types Lx10, Lx16 and Lx20 only operated on a few sections of the through carriage runs on the Simplon-Orient- or Orient-Express. As a special feature, the Simplon Orient Express was given a baggage car with a shower compartment from 1930 onwards.

After 1945 old type R teak wagons were still used at times on the Simplon-Orient-Express, but were soon scrapped. The Type S remained in service until 1965, most recently between Paris and Bucharest. The Lx wagons, which originally only had single compartments, were soon completely or partially converted to two-bed compartments and also ran on the trains of the Orient Express system after the war. By the end of the 1960s, they were also scrapped, as were the types Z and Y. From 1955, the first new type P sleeping cars were used. CIWL built this under license from the American vehicle manufacturer Budd with external walls made of stainless steel . The MU vehicles acquired in 1964 were also used on the Orient Express.

Since the mid-1960s, the remaining train routes and wagons of the Orient Express system no longer differed significantly from other international long-distance trains in Europe. From 1968 the CIWL introduced the uniform type T2 , which the DSG also used and which was further procured from 1971 as part of the TEN pool by the participating state railways. Since the 1950s, there were also couchette cars on the trains that were provided by the state railways involved.

The pre-war blue steel dining cars remained on sections of some trains of the Orient Express system until 1966, but in principle the CIWL started using newly delivered dining cars from 1950 until the use of dining cars gradually ended in 1962. With the exception of the Greek and Turkish routes, the use of CIWL dining cars on the Eastern and Southeastern European routes ended as early as 1950, but the local state railways continued to use older dining cars that were taken over from the CIWL for years.

Until the final discontinuation of the Orient Express in 2009, its fleet of cars consisted of seated, sleeping and couchette cars from the participating state railways.

Locomotives

On the first run of the Orient Express, around 20 different locomotives were used, due to the eight railways involved and the relatively short range of the locomotives at the time. Unlike, for example, the Rheingold of the Deutsche Reichsbahn, which is also known for the locomotives of the formerly Bavarian class 18.4-5 , which were used from 1928 onwards , the Orient Express is not associated with any particular locomotive series in the specialist literature. The state railways involved each use their most modern locomotives, so that over the years almost all express train locomotive series of the respective railway administrations were used before the Orient Express and the other trains in the system. In contrast, the French steam locomotive 4353 of the class PO 4200 of the Chemin de fer de Paris à Orléans , known from its use in front of the Orient Express in the Agatha Christie filming Murder on the Orient Express, never counted among the scheduled locomotives. Nevertheless, it is so well known because of the film that the Institut du monde arabe (IMA) used it as an eye-catcher for its exhibition on the Orient Express in 2014.

1883 to 1914

The locomotives used in the first few years are largely unknown. At this time, the railways involved almost always used express train steam locomotives of various types with the 1'B wheel arrangement. From around 1890, the 2'B wheel arrangement was increasingly used. Some railways also used locomotives with the 1'B1 'wheel arrangement, such as the Königlich Württembergische Staatsbahn, which used the Württembergische E before the Orient Express from 1892 . The locomotives with two coupling axles were soon overwhelmed by the increasing train weights and the desire for faster travel times, so that from around 1900 to 1910 all railways switched to locomotives with three coupling axles. One of the last locomotives with two coupling axles was the Württembergische ADh , which was used before the Orient Express until 1908.

In the last years before the First World War, the following locomotive series were used before the Orient Express:

- Chemin de Fer de l'Est: Est 3100 (2'C wheel arrangement, from 1907)

- Imperial railways in Alsace-Lorraine: Alsace-Lorraine S 9 (from 1908) and Alsace-Lorraine S 12 (from 1909)

- Grand Ducal Baden State Railways: Badische IV f (from 1908)

- Royal Württemberg State Railways: Württembergische C (from 1909)

- Royal Bavarian State Railways: Bavarian S 3/6 (from 1908), from 1907 to 1910 temporarily Bavarian S 2/6

- kk Austrian State Railways: kkStB 310 (from 1911), kkStB 109 (east of Vienna, from 1902 as StEG 36.5)

- Royal Hungarian State Railways: MÁV class 327 (from 1912)

- Royal Romanian railways: CFR class 231 (wheel arrangement 2'C1 ', similar to Bay S 3/6, from 1913)

- Serbian State Railways: SDŽ 151 to 158 (wheel arrangement 1'C1 ', from 1912, later JŽ 04)

- Bulgarian State Railways: BDŽ-series 09 (wheel arrangement 2'C1 ', 1912 supplied as a single copy especially for the Orient-Express), BDŽ-series 27 (wheel arrangement 1'D, from 1911)

- Orientbahn: CFO IX (wheel arrangement 2'C, from 1908), CFO XIV (wheel arrangement 1'C1 ', from 1911)

1919 to 1940

Even before the First World War, various European railway administrations began to electrify individual routes. With the expansion of the Orient Express to a whole train system, its train runs were therefore transported on the first sections by electric locomotives. The steam locomotives used before the war were largely replaced by newer machines in the 1920s.

The French railways - with the introduction of the Simplon-Orient-Express, the PLM was also included in the network - until 1939 mainly used their most modern express locomotives, both modern Pacifics and the large Mountains with the 2'D1 'wheel arrangement. The Eastern Railway put the Est 241 an A, the PLM its PLM 241 A . On the steep routes up to the Swiss border, PLM used the PLM 141 E series and older Mikado series before the Simplon-Orient-Express . The French AL in Alsace-Lorraine continued to use their pre-war S 9 and S 12 series .

The Deutsche Reichsbahn initially continued to use the various express train series of its predecessor trains, which it had taken over as the 18 series. From 1927 the section between Stuttgart and Salzburg was gradually electrified, the DR replaced the Württemberg series C and the Bavarian S 3/6 before the Orient Express with electric express locomotives, initially the DR series E 16 and DR series E 17 . In the 1930s, the DR series E 04 and finally the DR series E 18 were also used. Between Strasbourg or Kehl and Stuttgart the Baden IV f disappeared in favor of the DR series 39 .

After the First World War, Switzerland began rapidly electrifying its rail network. The steam locomotives of the type SBB A 3/5 pulled the Simplon-Orient- and the Arlberg-Orient-Express for only a few years and were completely replaced by the new SBB Ae 3/6 and SBB Ae 4/7 by 1930 . The Ae 3/6 were only used on short sections such as between Sargans and Buchs SG , on most sections the Ae 4/7 were planned as scheduled covering.

In Austria, various routes were also fitted with contact wires in the 1920s . Before the Arlberg-Orient-Express, the BBÖ 1100 replaced the previously used BBÖ 81 on the Arlbergbahn from 1924 . On the valley routes, the BBÖ 1570 and BBÖ 1670 took over the traction of the luxury train from the steam locomotives of the BBÖ 113 and BBÖ 110 series . East of Salzburg, the Gölsdorf locomotives , which were taken over as BBÖ 310, remained the locomotives of the Orient Express until 1938, when they were replaced by the new tank locomotives of the BBÖ 729 series. Before the Arlberg-Orient-Express, these locomotives had already proven their worth since 1933. The heavy express locomotives of the BBÖ 214 series, which were also newly acquired , were not used before the comparatively light Orient Express trains. The short sections to the new border stations with Czechoslovakia and Hungary were taken over by the new tank locomotives of the BBÖ 629 series from 1927 .

The Italian Ferrovie dello Stato (FS) also electrified part of the routes used by the Simplon Orient Express. The FS E.626 replaced the steam locomotives of the series FS 685 (wheel arrangement 1'C1 ') and FS 691 (wheel arrangement 2'C1') in the Trieste area to Postumia , the former border station to Yugoslavia, during the section between Milan and Venice For the time being, the steam locomotives remained, as did the route from the border station Domodossola to Milan.

The Hungarian state railway MÁV electrified the line from Hegyeshalom on the border to Austria to Budapest in 1934 , the standard locomotive on this line, the MÁV V40 series, also hauled the Arlberg-Orient-Express. Steam locomotives remained in service east of Budapest and the Italian border until after the Second World War. The MÁV used their standard locomotives of the MÁV class 424 , while the ČSD used the ČSD class 375.0 before the Orient Express on the section between Bratislava and the Hungarian border . In Romania, the Hungarian 327s used before the war continued to be used, now numbered as CFR 230. The CFR also held on to their Maffei - Pacific's series 231, in addition came in 1937 the CFR built according to the plans of the Austrian BBÖ 214142 used.

The newly founded railways of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (SHS) used the formerly Hungarian class 323 (JDŽ 107) before the Simplon-Orient-Express, but above all their 1'C1 'locomotives of the class SDŽ 121ff. (JDŽ 01). From the beginning of the 1930s, the Yugoslav State Railways (JDŽ) also used the JDŽ 05 series of heavy Pacific locomotives newly delivered from Germany . To the west of Zagreb the JD® 06 , with the 05 closely related Mikado locomotives , at times ran the Simplon Orient Express. After the war, the BDŽ used locomotives of the BDŽ class 08 , which corresponded to the Bavarian P 3/5 N , in addition to the one-off series 09 locomotives . From 1930 new Mikados of the series 01 and 02 were used, the Pacifics of the series 05 were only delivered from Germany from 1941 and were only used on the remaining routes of the Orient Express during the war.

The demarcation between Turkey and Greece caused inconvenient operating conditions, as the line after the Bulgarian border station Svilengrad first reached the Greek Ormenio , then switched to the Turkish Edirne , which in turn served the Greek station Pythio and finally the Turkish Uzunköprü . The section from Svilengrad to Pythio was operated from 1929 by the Chemin de fer Franco-Hellenique , which continued to use the locomotives already used by the Orientbahn. The last section from Uzunköprü to Istanbul remained with the Orientbahn until 1937 and was only then taken over by the Turkish state railways TCDD . Both railways use 1'D locomotives with separate tenders, which were grouped as class 45.5 at the TCDD . On the Greek section, the Simplon-Orient-Express was finally transported by powerful 1'E locomotives of the SEK series Λα (Lambda-Alpha) based on the model of the 580 series of the Austrian Southern Railway .

1945 to 2009

After the Second World War, the state railways involved in the train runs initially continued to use mainly steam locomotives. Since only a few steam locomotives were built after 1945, the majority of these were the series used before the war; the few exceptions included, for example, the SNCF 141 R delivered from 1945 , which the French state railroad, for example, north of Paris and between Dijon and Vallorbe used before the Simplon-Orient-Express. With the heavy 1'E1 'of the SEK series Μα (My-Alpha), the Greek State Railways also used new steam locomotives .

From 1950, however, the electrification of the main lines and the conversion to diesel locomotives quickly began . The Orient Express ran continuously from Paris to Vienna with electric locomotives from 1962 onwards, while the scheduled use of steam locomotives on the Arlberg Orient and Simplon Orient Express also ended in the early 1960s. The last time the German Federal Railroad hauled the Arlberg Express between Lindau and Munich in 1965 during a winter diversion was one of the last locomotives of its class 18.6 . Diesel locomotives were only used for longer periods on a few routes in Western Europe; most routes were electrified by the mid-1960s.

The Eastern European railways followed a few years later, which led to longer periods of diesel locomotive use. The last steam locomotives disappeared in the 1970s, most recently the Greek and Turkish state railways occasionally hauled the Direct-Orient and its Greek through car feeders with steam locomotives. From around 1980 the contact wire was only missing on a few sections of the classic Orient Express routes. In addition to the Paris – Belfort route used by the Arlberg Express , these were above all the route from Niš to just before Istanbul, which is only partially electrified in Bulgaria, and the entire Greek section south of the Yugoslav border station Gevgelija . They remained without contact wire until the end of the continuous train runs from Western Europe.

Tourist trains

Even before the end of the continuous Orient Express to Istanbul, private entrepreneurs began restoring old CIWL wagons and using them for charter journeys on rails. The nostalgic train sets that have been created in this way have been used by various companies for rail cruises since 1976. They all have names that are derived from the Orient Express, but which do not correspond to the historical names of the scheduled trains.

On other continents, too , luxury trains used for rail cruises are often referred to with the epithet "Orient Express", sometimes in a slightly modified form. Examples are the American Orient Express used in the USA , the Eastern and Oriental Express , which runs between Bangkok and Singapore in Southeast Asia , and the Indian Royal Orient Express .

Nostalgia Istanbul Orient Express

The first provider of this type of rail cruise was the Swiss entrepreneur Albert Glatt , owner of Intraflug AG. He has been collecting original CIWL cars from the 1920s and 1930s since the early 1970s and had them restored to their delivery condition from 1926-29. The Nostalgie Istanbul Orient Express (NIOE) was the first luxury train of its kind and ran from the beginning of 1976 to mid-2008. Only restored original vehicles from the CIWL were used. Various routes across Europe were offered.

The NIOE wagons undertook their furthest journey in September 1988, when they drove from Paris across Europe via Berlin, Warsaw, Moscow and the Trans-Siberian Railway to Hong Kong on the occasion of the anniversary of a Japanese television station . Brought to Japan by ship , they were reconnected to the Cape gauge and used for various journeys.

1993 took over travel agency Mittelthurgau the car of the NIE and put them together with five observation car of the TEE Rheingold , two cars from the historic Rheingold -Luxuszug the German Railway in 1928 and converted the French State Dining Car No. 3354 (of French President Charles de Gaulle ) a. An L'Aquitaine SNCF dining car has also been restored in a nostalgic style.

Thirteen NIOE wagons were re-gauged for the Russian broad gauge on their own bogies and ran on the Russian broad gauge network, including the Trans-Siberian Railway, until October 2007. At the beginning of 2008, the NIOE, train part Russia traffic, returned from the Moscow depot to Europe and was at the PKP backed up securely.

After the bankruptcy and bankruptcy of the Mittelthurgau travel agency and the Mittelthurgau Railway in 2001, the Transeurop Eisenbahn AG (TEAG) in Basel took over the entire NIOE and its more than 30 former CIWL wagons built between 1926 and 1929. The wagons were completed between 2003 and 2005 at a cost of millions renovated and revisions carried out. The company Orient-Express Luxury Train Betriebs GmbH / Austria led railway operations and sales. The NIOE fleet of TEAG and two subsidiaries now includes 32 former CIWL cars. The inventory also includes former saloon cars of the Nazi Reich government and six old Rheingold cars from 1928, two of which have been completely renovated.

Due to a legal trademark dispute over the original brand name Orient-Express initiated by the operating company of the Venice Simplon Orient Express (VSOE) and conducted with the SNCF, the NIOE had to be shut down in 2007. In 2008 an international court was due to rule on the lawsuit and a counterclaim that has since been filed. The case has since been accepted by the European Court of Justice , but no decision has yet been made. A decision period is completely open. The NIOE's business and driving operations have been inactive since July 2008, and the CIWL wagons have been safely preserved. In autumn 2008 the vehicles were sold to an American railroad company. This operates the train as the Grand Express European - Train de Luxe .

In 1988 a trip was made from Paris to Hong Kong . 13 wagons of the historic train used were leased to the Russian company Orient-Express , which organized charter trips starting in Vladivostok and Beijing for twelve years . After the lease expired in 2008, the wagons were to be returned to their owner in Austria, but the owner was not prepared to pay fees for the storage of the standard gauge bogies in Belarus. As a result, the wagons were parked on a wide-gauge siding in the Polish marshalling yard Małaszewicze near the border with Belarus , whereby PKP also charged fees for the use of the siding. Conversely, the owner of PKP Cargo asked for the damage caused by vandalism to be settled. The wagons were finally taken over by SNCF and transported away without bogies in January 2019.

Venice Simplon Orient Express

In 1977 Sea Containers Ltd. began . Acquire and extensively restore historic cars that were first used in 1982 as the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express (VSOE). The first trip offered was the route of the former Simplon Orient Express from London to Venice and once a year to Istanbul. In Great Britain, the Belmond British Pullman operates as a feeder during daytime traffic, passengers travel by ship across the English Channel and continue on the continent with the VSOE. In addition to the trips on the route of the former Simplon-Orient-Express, the VSOE also operates to other cities in Europe. The historic cars were modernized in the 2000s and fitted with new bogies so that they can run at 160 km / h.

Pullman Orient Express

In 1967, the CIWL first briefly pursued plans for a rail cruise with its blue sleeping car on the historic route of the Orient Express between Paris and Istanbul, which it ultimately did not implement. After the success of NIOE and VSOE, CIWL only got into the business of nostalgic trips in 1994. She initially used seven, later nine, of her historic dining and Pullman cars, built between 1920 and 1939, mainly for day trips in domestic traffic in France or rented them to tour groups. In contrast to the NIOE and VSOE, however, the CIWL generally did not use sleeping cars on these trains; if necessary, normal sleeping cars from the SNCF fleet were used.

The Pullman Orient Express has also been inactive since 2007 due to the trademark dispute over the name Orient Express. The Accor Group, as the owner of CIWL, decided to discontinue operations as it was being attacked under trademark law by the SNCF and VSOE. The vehicles have not been used since then and should be taken to a museum if necessary. A restart was ruled out, according to the board decision. The train was taken over by SNCF in 2008 and has since been marketed as Orient-Express by the Société des Trains Expos (STE) branch .

Cultural and political importance

Soon after its introduction, the Orient Express was seen as a train of diplomats , spies and adventurers . It was “the epitome of luxurious travel, combined with the mysterious magic of illustrious names and events” ( Hermann Glaser : Kulturgeschichte der Deutsche Eisenbahn, Gunzenhausen 2009). Like famous passenger steamers of the Belle Époque, the Orient Express stood for the advancement of western civilization. Der Spiegel described the passengers on the train in 1948 as follows:

"Secret agents clad in mink, men with monocles and little beards, indefinable chiefs of any ethnic group, beautiful women who no one knows what they live on, royal highnesses on the run and Indian maharajas."

At the same time, all questions relating to the timetable and the route of the Orient Express were eminently politically determined. Its introduction in 1883 was a direct consequence of the results of the Berlin Congress in 1878, which obliged the participating Balkan states to expand the railway lines and operate at least one continuous daily train. After the conclusion of the Paris suburb agreements in 1919, the victorious powers converted the connecting function of the Orient Express into a separating one - the Simplon Orient Express was created under the premise of "revenge and security", which France put before its policy in the years after the First World War . At the same time as the reconciliation between Gustav Stresemann and Aristide Briand and Germany's return as an equal player in international politics, the first through coaches of the Orient Express were once again led through Germany and beyond Vienna. Most recently, the outcome of the Lausanne Conference in 1932 was symbolically reflected in the reintroduction of direct coaches from Paris to Istanbul on the Orient Express, which ran across southern Germany, in the same year.