Hardcore punk

|

Hardcore punk

|

|

| Development phase: | Late 1970s |

| Place of origin: | United States , Canada , United Kingdom |

| Stylistic precursors | |

| punk | |

| Pioneers | |

| Dead Kennedys , Bad Brains , Angry Samoans , Black Flag , Minor Threat , Discharge , GBH , The Exploited | |

| Instruments typical of the genre | |

| Electric guitar , electric bass , drums | |

| Stylistic successor | |

| Digital Hardcore , Melodic Hardcore , Crustcore , Grindcore , Metalcore , Post-Hardcore | |

The hardcore punk (often referred to as hardcore abbreviated) originated in the late 1970s in the United States and independently in the UK as a more radical and faster development of punk rock . The original hardcore era has been over since the mid-1980s, when hardcore began to split into different subgenres. Since then there have been, on the one hand, so-called "old-school" groups oriented towards the original hardcore punk, on the other hand, bands developed at that time that included other styles of music, including metal, and therefore attributed them to post-hardcore become. These bands, which nevertheless strongly identified with punk rock, were called "new school" hardcore at the time.

Only later were the terms understood as a division, when the “new school” term was almost only used for some of the bands of this development, whose music and self-image were strongly oriented towards metal and whose style development ultimately led to metalcore .

Hardcore punk had a great influence on later music styles such as grunge , crossover or extreme metal .

Origin of the term hardcore

There are different opinions about the origin of the term "hardcore", the term is often traced back to the Canadian DOA , who are said to have invented or at least spread the term hardcore with their second album Hardcore '81 . Charlie Harper , singer of the British band UK Subs , has a different view , according to which hardcore is said to have emerged after the manager of the UK Subs and Anti-Nowhere League used the term "hardcore punk" to describe her during a joint US tour of the two bands Styles of music used. In Germany, the term hardcore punks has appeared in the music magazine Sounds since 1980 at the latest , initially for particularly tough fans of punk rock, later also for musically tougher groups like Die Wichser and important samplers like "Underground Hits 1". Martin Büsser cites a quote from Vic Bondi from the Headspin , according to which the term comes from the US military :

“Do you know the origins of the term 'hardcore'? You are in the Vietnam War . The American soldiers had a ritual: when a new soldier came to Vietnam he was called 'a cherry'. What it was about was 'making it hardcore'. To 'hardcore' someone meant they should be able to kill without blinking an eyelid. So you were hardcore if you could kill without hesitation. "

historical development

Beginnings

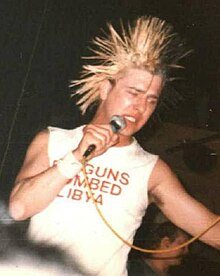

Hardcore emerged in the late 1970s, when a new generation of young people found access to punk music who, unlike the representatives of 77s punk rock, had not grown up with garage and glam rock of the 1960s and 1970s , but with punk rock, and radicalized this form of music in terms of speed and text. The classic image of a punk with a mohawk or "liberty spikes" that dominates today was only coined in the era of hardcore punk.

Paul Rachmann explains the difference between punk and hardcore with the different socialization; in hardcore music itself should be understood as a message. Punk is "musically also aggressive [...], but all in all much more accomplished and conceptual". It started out in metropolises like London and New York, and was then picked up in metropolises like Los Angeles and San Francisco; these had museums, galleries and an “intellectual climate” to show, whereas hardcore developed in suburbs and was “uncultivated” compared to Patti Smith , Television , the Ramones and the CBGB . Possibly the first hardcore punk album is the LP GI by The Germs (1979), produced by Joan Jett .

In the USA and Canada, five bands in particular, the Dead Kennedys , Bad Brains , Angry Samoans , Black Flag and Minor Threat, are the initiators of "American Hardcore". In Great Britain, however, “UK Hardcore” or “UK82” was shaped by bands such as Discharge , GBH and The Exploited . Although both scenes influenced each other (e.g. through tours by GBH and Discharge in the USA or by the Dead Kennedys and Black Flag in Great Britain), both hardcore scenes were very different in appearance and content. In addition to the USA and Great Britain, hardcore punk also spread to other countries such as Japan, Australia and Latin American countries (especially Brazil) in the early 1980s. On the European mainland a separate “Euro-Hardcore” emerged, especially in Germany and Scandinavia, but also in Italy. The Buttocks , OHL , Toxoplasma and Chaos Z are among the early German representatives of hardcore punk .

American hardcore

Initial phase from 1979 to around 1985/1986

The initiators of the early West Coast hardcore were primarily the bands Dead Kennedys and Black Flag , while East Coast hardcore was mainly influenced by the Bad Brains . Through fanzines , exchanging audio cassettes by post and concerts and tours, both scenes had a strong influence on each other and a common sense of togetherness in the hardcore scene and cross-band networks were formed. Los Angeles , San Francisco (Cali-Punk, or "Nardcore"), Boston ( Boston Hardcore ) and Washington DC-Hardcore were early strongholds of hardcore with their own influential scenes, and New York Hardcore (NYHC) later also gained in importance . In addition, however, influential hardcore scenes developed in Texas , Portland and in the northwest around Seattle . A separate Canadian scene was largely shaped by the preparatory work of the DOA group .

Important labels that were founded at that time included SST Records for Black Flag in California , BYO Records for Youth Brigade and Dischord in Washington DC for Minor Threat , which founded the Straight Edge culture with their song of the same name.

Communication in the scene mainly took place through fanzines. Especially the magazines Flipside and Maximum Rock'n'Roll became the main media of the movement.

Further development from around 1985/86

Between 1984 and 1986, many of the most influential bands in the early hardcore scene broke up or changed their style significantly. At the same time, a new generation of bands emerged who brought new influences - especially from the metal field - to the music. New names for genres such as power violence, mosh and crossover thrash emerged. The political climate after the re-election of Ronald Reagan also began to change many of the themes of the hardcore bands. With the emergence of the youth crew movement, the new hardcore scene began to move away from the image of punk. A new look, the “clean look”, prevailed and stood out from the look of the classic hardcore punks. In addition to the new Metal-influenced hardcore varieties, known as "New School", new scenes emerged from hardcore such as the grunge movement and post-hardcore . Some groups like the Beastie Boys or later Biohazard began to experiment with hip-hop influences, from which the crossover core developed. From criticism of the growing machismo within the hardcore movement, emotional hardcore, or emo for short, developed especially in Washington, DC .

In the early 1990s, in addition to a new straight-edge movement, mainly metal-influenced NYHC bands appeared on the scene. At the same time there was also a revival of old-school hardcore. In addition, West Coast hardcore was increasingly commercialized due to the mainstream success of Melodycore groups such as Bad Religion and NOFX . The late 1990s saw the emergence of a new metalcore scene as well as a revival of the youth crew movement.

More bands

1979-1985 / 86

- 7 seconds

- Adolescents

- Angry Samoans

- Antidotes

- Artificial Peace

- Battalion of Saints

- Bad brains

- Black Flag

- Cause for alarm

- Circle jerks

- Crucifix

- Dead Kennedys

- Descendents

- Dirty Rotten Imbeciles

- Pinball machine

- Gang Green

- Heart attack

- Jerry's kids

- JFA

- Hüsker Dü

- MDC

- Minor threat

- Nausea

- Negative approach

- Poison Idea

- Reagan Youth

- Rich kids on LSD

- Scream

- SS Decontrol

- Suicidal tendencies

- The mob

- TSOL

- United mutation

- Urban waste

- Youth Brigade

1985 / 86-1999

2000 until today

- Bane

- Behind enemy lines

- Black Breath

- Casey Jones

- Caustic Christ

- Code orange

- Comeback kid

- champion

- Death Before Dishonor

- Death by Stereo

- First Blood

- The Ghost Inside

- Have heart

- Off!

- Rise Against

- Rotting out

- Strike Anywhere

- Stick to your guns

- terror

- Tragedy

- Gymnastic styles

- Walls of Jericho

- The Warriors

UK hardcore

Classic phase 1979 to around 1985

UK hardcore emerged in the early 1980s directly from the environment of harder street punk groups. Particularly important is the influence of the group Discharge , whose "D-Beat" exerted a great influence on many hardcore and metal bands worldwide. However, some “UK82” groups such as Conflict are also part of the anarcho-punk movement, whose influence was less musical than political. The year 1982 is considered to be the peak of UK hardcore, after the genre was also called "UK82". From 1985, concert conditions deteriorated and many bands broke up or incorporated elements of metal into their music, leaving old fans disappointed.

Further development from around 1985

After the metal crossover of the 1980s and the collapse of the "UK82" scene, the most influential crust movement emerged in Great Britain around this time, combining elements of the anarcho scene , hardcore and metal into a new, independent subculture . In addition, the style of Grindcore , which was initially similar but more closely related to Death Metal , was created . Both scenes developed into independent subcultures, which also had an international impact on other countries such as Germany, Japan and the USA, while at the same time American Hardcore, especially the New School style influenced by Death Metal and the commercial Californian Melodycore began The 1990s increasingly affected a new British hardcore scene. At the end of the 1990s, in addition to smaller revivals of the “UK82” style, post-hardcore and metalcore had prevailed over classic hardcore punk in Great Britain.

More bands

1979-1985 / 86

1985 / 86-1999

2000 until today

Euro hardcore

Hardcore in Germany

In the beginning, hardcore was the term for harder punk in Germany. Groups like The Buttocks , Toxoplasma , and sometimes Slime were influenced by early British and American hardcore bands like Discharge, Dead Kennedys and Black Flag to a faster, harder style. They were later followed by groups such as the pre-war youth and the Spermbirds . The first band to become known outside of the German scene was Inferno . They were the first to have pieces that appeared on foreign samplers. From the mid-1980s, part of the German hardcore scene explicitly separated from the punk subculture and established German hardcore as a counterculture independent of classic punk rock, partly with reference to the American new school scene and the straight Edge thoughts. For a long time the fanzines ZAP and Trust were able to establish themselves as the mouthpieces of the German-speaking hardcore scene .

In some cases, the term hardcore was also used for punk bands without the rock 'n' roll elements common in the original bands , which would no longer fall under this name or are now usually referred to as German punk . So it says on the back of the re-release of the " H'Artcore " sampler:

“The somewhat strange title arises from the name of the label H'Art at the time and the new term hardcore in 1981, which at that time stood for harder, faster punk like here on the sampler (the expression German punk did not exist yet). Well, that's how it was back then ... "

Until the 1990s, two different hardcore punk scenes existed side by side, a German-speaking one that produced bands like Recharge or Rawside , and one based on American models, including bands like Ryker’s and Bonehouse .

In 2008 right-wing extremist mail order company and drummer Timo Schubert secured the word mark “Hardcore” in Germany. On December 28, 2009, the word mark was deleted due to an application by the Aktion Kein Bock auf Nazis .

More German bands

1978-1985

1986-1999

2000 until today

Content and values

Do it yourself

One of the central content-related points of hardcore punk is the do-it-yourself principle, which replaced the no-future attitude of the original punk. Do it yourself underlines the desired independence from the music industry, society and other external influences and thus the belief in yourself and your own strength to achieve things. This attitude can also be found in the nearby indie scene. The do-it-yourself idea is particularly evident in the fact that bands record and produce their music themselves and do not hire outsiders to do it, distribute their recordings themselves through labels specially set up for this purpose or that concerts are organized themselves, no bookers are commissioned and the Bands run their own stands at concerts.

Hardcore activists were also involved in autonomous centers from the start , the establishment of which has been based on DIY ideas since the 1960s. In the USA, the ABC No Rio in New York and “The Garage” in Minneapolis , among others, became centers of movement, the “924 Gilman Street project” in Berkeley, California is even directly initiated by the punk fanzine Maximum Rock'n 'Roll back. The sampler This Is Boston, Not LA , released by Modern Method Records in 1982 , was criticized for being released by "off-scene businessmen," such as SS Decontrol in The Kids Will Have Their Say . The subculture feared a change in the scene for which control from the inside, not the outside, was an integral part of DIY .

Straight edge

The term Straight Edge was coined by the American band Minor Threat and their front man Ian MacKaye . Refraining from alcohol, tobacco and all other drugs are central to the straight edge idea. The renouncement of frequently changing sexual partners is one of the three central points of the movement, which were formulated by the band Minor Threat in their song " Out of Step ": "(I) don't drink, (I) don't smoke, (I) don't fuck ”. Some straight edgers are also vegetarian or vegan . A popular way to identify yourself as a straight-edge follower is a black "X" on the back of the hand. In the 1980s, the black “X” was used in some clubs in the United States to mark underage visitors so that they were not served alcohol. The straight edge concept is also widespread in the metalcore scene.

politics

An important factor in hardcore punk music is politics. The political aspect of music ranges from nihilistic anti-attitudes (in early American groups like TSOL or British bands like the Exploited) to constructive social criticism in bands like the Dead Kennedys, Bad Religion or Conflict. The ideologies represented vary widely from liberal and ecological approaches (Dead Kennedys, Bad Religion) to anarchism (MDC) and communism (Born Against, Boysetsfire). However, widespread lifestyles such as straight edge or veganism are also seen as political values in the hardcore scene.

After the increase in the musical hardness and the combative attitude developed an "increasing manliness mania" and under the influence of the skinhead movement, chauvinism, social Darwinism and acceptance of violent behavior increased in the scene 1990s especially in the area around Olympia the movement of the Riot Grrrls , who dealt with Third Wave Feminism from a hardcore-punk and post-hardcore background and the role of women in the punk rock scene, as the organizer of Labels and concerts, artists and fanziner are more prominent. As some musicians from bands like Team Dresch and Tribe 8 to lesbianism known, there was some overlap for Queercore scene consisting of homosexual hardcore punks and provocative as subversive of the rights of homosexuals in society and their acceptance the punk scene sets in.

Through straight edge and the breakdown of hardcore, it increasingly broke with punk. This favored the radicalization of the skinhead in the scene, "who now blatantly acted as patriots" and formed an intersection with the right-wing rock scene, for which, according to the author collective Ingo Taler, "especially through the accentuation of hatred" in the Hatecore there were points of contact. Straight Edge also provided a starting point for NSHC and Autonomous Nationalists . Right -wing tendencies were particularly noticeable in New York Hardcore from the mid-1980s. Especially the bands Agnostic Front , Cro-Mags and Warzone - partly also Slapshot from Boston - formed the beginning of this development. Decisive for this were the highly apolitical aspects of some of the New York bands - at the British Oi! oriented - thoughts. And as in the UK with the emergence of Rock Against Communism , this development was repeated in New York. From the so-called apolitical views, nationalist , anti-communist and homophobic thoughts gradually developed . American flags on the stage and texts against gays shaped the image of the band Agnostic Front. The Warzone group, which sees itself as a skinhead band, was also shaped by anti-communist ideas; the members regularly emphasized their patriotism and also conveyed strongly patriotic content in some of the lyrics. In a characteristic song Fighting for Our Country , the group sang: "Fuck the communists and the people who always put us down / Because of them, fighting for our country, it mean so much to me". The band Youth Defense League from New York called themselves in a radio interview on the station WNYU as a White Pride band, but this could not apply to the whole band given the fact that one band member (Rishi) came from the Middle East. YDL was a "multi-racial band" just like Warzone and used the polarizing shock effect of a right-wing extremist attitude. These pro-American, anti-communist bands had nothing in common with today's racist Hatecore bands. Nevertheless, Taler describes YDL as a “white power band” that was “part of the New York HC punk scene”.

This development met with strong rejection in the hardcore and punk movement. In the period that followed, groups that defined themselves as strongly left-wing groups emerged, such as Born Against . On the one hand, the left-wing radical Hatecore of SFA in New York developed as a harder form , on the other hand, with the - often strongly left-wing - emotional hardcore bands - in New York Policy of 3 or Native Nod - others emerged Groups and many other anti-trend campaigns.

In the early 1990s, white power hardcore bands such as Extreme Hatred and Aggravated Assault appeared on the scene, building on the masculinity, musical harshness and dynamism of hardcore. In Europe, a “White Power HC boom” arose in the course of the tour of the band Blue Eyed Devils; As a buzzword, Hatecore has become “synonymous with racist hatred and racist violence”. At the end of the 1990s there was an increased discussion of the problem, which increased the right-wing extremist scene's interest in hardcore and its "adaptation of the music style and lifestyle". As a response from the radical left to right-wing extremist Hatecore, the “Good Night White Pride” campaign was launched, to which the German bands Full Speed Ahead and Loikaemie dedicated a song each.

After Blood & Honor was banned , the scene relied on “coded messages and lifestyle, which gave the extreme right a modern look and acted as a 'cultural door opener' for the 'autonomous [sic!] Nationalists'”. Accordingly, NSHC is described by Ingo Taler as an “ideology carrier without a clear political message”. Instead of using terms such as WP-HC, Hatecore and NS-HC, the right-wing extremist scene is now looking for the connection and using the term hardcore.

Hardcore and dress codes

A more radical form of punk style was common in early hardcore punk. While many “UK82” followers took this style to the extreme with extreme mohawk hairstyles or “liberty spikes” and studded leather jackets, a less extreme “street look” quickly spread in American hardcore, with only short hair (often as short “spikes "Or as a military" crew cut ", in the 1980s also as a short mohawk - often in the taxi-driver style) and band badges (band shirts, patches) were common. Elements of street gang culture such as colored bandanas , berets and graffiti were also adopted from the scene. Bands like Suicidal Tendencies , Agnostic Front and sometimes Sheer Terror , Cro-Mags and Poison Idea as well as their fans corresponded externally at times to typical "inner city thugs " rather than classic punks.

This style found many followers, especially in the “new school” and metalcore scene. At the same time, many American hardcore fans took up a form of the skinhead style that turned out to be particularly influential for the NYHC. Towards the end of the classic hardcore phase, however, many members of the original scene had their hair grow long demonstratively (often in the form of dreadlocks) in order to set themselves apart - a look that would later prevail, especially in the grunge scene. In New School Hardcore - especially by the youth crew movement - uniformity in the style of the “UK82” punks (“Nietenkaiser”) is mostly rejected. However, many bands are accused of having introduced their own form of uniformity through typical hardcore codes. Members of the youth crew scene mostly prefer sportswear, while the more militant scene members often prefer military clothing. Preferred hairstyle types are often bleached short haircuts or military crewcuts , an appearance that is referred to as a “clean look” or “clean cut”. The slogan “No Dresscodes” is directed against the uniformity and clichéd stereotyping of the hardcore scene.

Crews and gangs

Hardcore punks often meet and organize themselves in small, particularly close-knit groups of friends, which are also known as "crews". The Washington “Georgetown Punks” around Minor Threat and the New York “Lower Eastside Crew”, in which members of the Agnostic Front, Warzone and the Cro-Mags were involved, gained notoriety. In the second wave of the hardcore movement, many young people joined together to form so-called “youth crews”, based on the straight-edge lifestyle. In California, street gangs such as "LADS" (LA Death Squad) emerged from some hardcore crews. Other crews such as the " Friends Stand United " (FSU), which was formed in Boston from the band Wrecking Crew and was originally founded to clean the Boston hardcore scene of neo-Nazi influences, or the "Courage Crew" from Ohio , a radical straight-edge group, are often viewed critically because of their sometimes violent reputation - although they do not see or call themselves gangs. From other hardcore crews, for example from the "Better Youth Organization" founded by the Californian band Youth Brigade (whose New York chapter was led at times by agnostic front guitarist Vinnie Stigma ), independent labels and booking were also created Networks.

The music

Hardcore subgenres

- Buenos Aires Hardcore

- D-beat

- DC Hardcore

- Hatecore

- Melodic Hardcore

- New York Hardcore

- Powerviolence

- Skatepunk

- Streetcore

- Thrashcore

Independent styles influenced by hardcore

- Thrash metal

- Crust

- Digital hardcore

- Grindcore

- Metalcore

- Post-hardcore

- Skacore

- Queercore or Homocore

- Sludge

Hardcore labels

|

|

|

|

Media on the subject

literature

- Martin Ableitinger: Hardcore Punk and the Opportunities of Counterculture: Analysis of a Failed Attempt . Publishing house Dr. Kovac, 2004. ISBN 3-8300-1636-0

- Mark Andersen, Mark Jenkins: Dance of Days: Two Decades of Punk in the Nation's Capital , ISBN 1-888451-44-0 (English) (German translation: Punk, DC , ISBN 3-931555-86-0 )

- Peter Belsito, Bob Davis: Hardcore California: A History of Punk and New Wave , ISBN 0-86719-314-X (English)

- Steven Blush, George Petros: American Hardcore. A tribal history. , ISBN 0-922915-71-7 (English)

- Martin Büsser : If the kids are united. From punk to hardcore and back. Ventil Verlag Mainz, 2003, ISBN 3-930559-48-X (1st edition 1995).

- Dirk Budde: Take three chords… punk rock and the development towards American Hardcore . Coda Verlag, 1997, ISBN 3-00-001409-8

- Marc Calmbach: More than Music. Insights into the youth culture Hardcore . Transcript, 2007, ISBN 3-89942-704-1

- Ian Glasper "the day the Country Died-A history of Anarcho-Punk". Cherry Red Books, 2006, ISBN 978-1-901447-70-5

- Ian Glasper Burning Britain: The History of UK Punk 1980–1984 . Cherry Red Books, ISBN 978-1-901447-24-8

- George Hurchalla: Going Underground: American Punk 1979-1989 . 2nd Edition. PM Press, Oakland 2016, ISBN 978-1-62963-113-4 .

- Matthias Mader: New York City Hardcore - The Way it was . IP Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-931624-10-2

- Matthias Mader: This is Boston, not New York. A hardcore punk encyclopedia. IP Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-931624-19-6

- Craig O'Hara: The Philosophy of Punk. The story of a cultural revolt. Valve, 2001, ISBN 3-930559-72-2

Movies

- 1991: The Year Punk Broke (USA 1992)

- American Hardcore (USA 2006)

- Another State of Mind (USA 1984)

- Boston Beatdown vol. II (USA 2004)

- NYHC (New York Hardcore; USA 2008)

- Repo Man (USA 1984)

- Suburbia (USA 1984)

- The Decline of Western Civilization (USA 1981)

- The Edge of Quarrel (USA 2000)

- The New York Hardcore Chronicles (USA 2017)

- The Slog Movie (US 1981)

- xxx All Ages xxx (USA 2012)

Web links

- Wolfgang Sterneck: The goal of change - hardcore and consistent music

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. for example with the self-determination of bands like Refused ; Quote: “We made this album wanting to challenge peoples preconceptions of what a punk band could be and what it could play […]” - Dennis Lyxzén / Refused; accessed on February 8, 2008. Also Snapcase: straightedgelifestyle.moonfruit.com. Accessed February 8, 2008; "Would you like to talk about the tour? Snapcase are a band that have broken grounds I think in every area of hardcore as one of the most furious and passionate punk bands "

- ↑ Steven Blush: American Hardcore. A tribal history . 2nd Edition. Feral House, Port Townsend 2010, ISBN 978-0-922915-71-2 , pp. 18 .

- ↑ Arte.tv: UK Subs ( Memento from October 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ punk-disco.com

- ↑ punk-disco.com

- ^ Ingo Taler: Out of Step . Hardcore punk between rollback and neo-Nazi adaptation. series of anti-fascist texts / Unrast Verlag, Hamburg / Münster 2012, ISBN 978-3-89771-821-0 , p. 16 .

- ^ Ingo Taler: Out of Step . Hardcore punk between rollback and neo-Nazi adaptation. series of anti-fascist texts / Unrast-Verlag, Hamburg / Münster 2012, ISBN 978-3-89771-821-0 , p. 20 .

- ↑ Crispin Sartwell: Political Aesthetics . Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY / London 2010, pp. 111 ( google.com [accessed September 6, 2014]).

- ^ Tesco Vee & Dave Stimson: Touch and Go. The Complete Hardcore Punk Zine '79 -'93 . 3. Edition. Bazillion Points, New York 2013, ISBN 978-0-9796163-8-9 , pp. XIX .

- ↑ “Hardcore” no longer a neo-Nazi brand. Press display, January 25, 2009, accessed January 26, 2009 .

- ↑ taz.de : Hardcore term is now the right brand

- ↑ a b Ingo Taler: Out of Step . Hardcore punk between rollback and neo-Nazi adaptation. series of anti-fascist texts / Unrast-Verlag, Hamburg / Münster 2012, ISBN 978-3-89771-821-0 , p. 11 .

- ↑ a b Ingo Taler: Out of Step . Hardcore punk between rollback and neo-Nazi adaptation. series of anti-fascist texts / Unrast-Verlag, Hamburg / Münster 2012, ISBN 978-3-89771-821-0 , p. 19 .

- ↑ a b c d e Ingo Taler: Out of Step . Hardcore punk between rollback and neo-Nazi adaptation. series of anti-fascist texts / Unrast-Verlag, Hamburg / Münster 2012, ISBN 978-3-89771-821-0 , p. 12 .

- ↑ a b c Ingo Taler: Out of Step . Hardcore punk between rollback and neo-Nazi adaptation. series of anti-fascist texts / Unrast-Verlag, Hamburg / Münster 2012, ISBN 978-3-89771-821-0 , p. 13 .

- ↑ for example at the concert of Agnostic Front, Sick of It All and Gorilla Biscuits in 1991 in New York

- ^ Matthias Mader: New York City Hardcore - The Way It Was ... 143rd edition. IP Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-931624-10-1 .

- ↑ Christoph Schulze: Label fraud: The autonomous nationalists between pop and anti-modern . Tectum Wissenschaftsverlag, Marburg 2017, ISBN 978-3-8288-6672-0 , p. 245 .

- ^ "Mike's Angle" blog. Retrieved May 5, 2008

- ^ Ingo Taler: Out of Step . Hardcore punk between rollback and neo-Nazi adaptation. series of anti-fascist texts / Unrast-Verlag, Hamburg / Münster 2012, ISBN 978-3-89771-821-0 , p. 12 f .

- ↑ trust-zine.de

- ↑ a b homepages.nyu.edu