Restructuring of the federal territory

Reorganization of the federal territory is a term from the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany ( Art. 29 GG), which regulates the restructuring of the territorial layout of the states, for example through mergers or border adjustments. A territorial reorganization must be confirmed by referendum .

A reorganization of the federal territory has been discussed again and again since the Federal Republic was founded . So far, it has only been completed by the merger of the states of Baden , Württemberg-Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern to form the new state of Baden-Württemberg in 1952. The attempt to unite Berlin and Brandenburg into a new state of Berlin-Brandenburg failed in May 1996 that the necessary quorum of the state reorganization treaty was not achieved in Brandenburg , and 63% of the citizens who voted voted “no”.

Not under the concept of reorganization within the meaning of the Basic Law covered the changes made in 1990, some of the 1,952 existing borders divergent boundaries of the five new federal states , nor the municipal reclassifications within federal states (mergers and boundary changes of municipalities and counties, mainly through local government reform ) .

Regulations of the reorganization in the Basic Law: Art. 29 and 118 GG

The current version of Article 29, Paragraph 1 of the Basic Law, which has been in force since 1976, states: “The federal territory can be restructured to ensure that the federal states, according to their size and efficiency, can effectively fulfill their tasks. The ties to the country team, the historical and cultural context, the economic expediency and the requirements of regional planning and regional planning must be taken into account. "

The reorganization must be carried out by federal law and confirmed by a referendum in all the countries concerned . This does not mean that the federalist principle of the existence of countries as such is up for grabs (see Article 79.3 of the Basic Law), but their number and territorial layout can be changed on the basis of the reorganization article of the Basic Law.

Until the German Treaty of 1955, the reorganization article was subject to the reservation of their mutual approval by the Western Allies and was changed several times. But the Allies, too, had pointed out the need for a reorganization early on after drawing the boundaries following the occupation areas.

The most significant change to the article was the amendment of August 23, 1976: Through it, the Bundestag and Bundesrat turned the original target obligation, which was to be achieved within three years, into a purely optional provision.

Art. 118 and Art. 118a of the Basic Law, which were added specifically for Baden-Württemberg and, after German reunification, also for Berlin and Brandenburg, provide for an accelerated reorganization procedure . According to this, a mere "agreement" of the respective countries can be reached, in deviation from the regulation according to Art. 29 GG (with obligatory referendum and referendum), which, however, must be confirmed by the population concerned.

Chronology of the restructuring debates

prehistory

The most striking feature of the territorial structure of the Old Kingdom was its "extreme fragmentation". The only major changes to its territorial organization were armed forces and external interventions: the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss in 1803 dissolved almost all clerical principalities and assigned many smaller rulers to larger ones. With these mediatized territories, numerous secular princes were compensated for their losses on the left bank of the Rhine. In the Napoleonic era up to the Congress of Vienna , the number of territories was reduced from over 300 to 39.

German Confederation and Empire

The German Confederation (1815–1866) made leaving and joining the Confederation dependent on a unanimous decision by the Bundestag. Nevertheless, there were changes in the existence of the member states through succession or abdication. Hessen-Homburg fell to Hessen-Darmstadt in 1866, shortly before the end of the German Confederation, after the prince had died.

In the revolution of 1848/1849 a general mediatization (in the sense of the abolition of small states) was only discussed. Already in the pre-parliament , the left unsuccessfully proposed the division of Germany into a manageable number of imperial circles. The Frankfurt National Assembly left it with the request to the provisional central power to mediate between governments and populations. During the revolution, the number of individual states only decreased because the two principalities of Hohenzollern-Hechingen and Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen fell to Prussia.

After the German War and the dissolution of the German Confederation , Prussia annexed the sovereign federal states of Hanover , Nassau , Electorate Hesse and the Free City of Frankfurt and finally incorporated Schleswig-Holstein. In the North German Confederation and in the German Empire (1867–1918) there were only minor changes in territory.

Weimar Republic and the Nazi era

The actual reorganization debate in Germany, which continues to this day, did not begin until 1919 as part of the deliberations on a new Reich constitution and reform. The plan drawn up by Hugo Preuss , the 'father of the Weimar Constitution ', to divide the empire into 14 areas of almost equal size failed, mainly due to concerns of the government and the resistance of the states. Art. 18 was included in the Reich constitution, which made a reorganization possible, but set high hurdles: "To decide on a change of territory or a new formation, three fifths of the votes cast, but at least a majority of those entitled to vote, are required." In fact, it only came until 1933 on four smaller territorial changes: the merger of Thuringia (1920), the union of Coburg with Bavaria (1920), Pyrmonts (1922) and Waldecks (1929) with Prussia .

A plan for the reform of the Reich in the country commission from 1930 and in the Lutherbund from 1928 to 1933, which essentially aimed to dissolve the dualism between Reich and Prussia by splitting what is by far the largest country into "new" countries and in return the position of the " Upgrading old ”countries through the transfer of powers failed“ because the domestic political conditions for state reforms suddenly deteriorated with the general systemic crisis that broke out in 1930 and was accelerated by the economic crisis ”.

In 1934, during the Nazi era , Mecklenburg-Strelitz was united with Mecklenburg-Schwerin to form the Free State of Mecklenburg. In 1937, the Greater Hamburg Law expanded the city area by 80% and made Lübeck lose its territorial independence.

The district of Herrschaft Schmalkalden and the administrative district of Erfurt came de facto to Thuringia through the “Leader's Decree on the Formation of the Provinces of Kurhessen and Nassau” and “The Leader's Decree on the Subdivision of the Province of Saxony” of April 1, 1944 , “around the administrative districts ... to adapt to the Reich Defense Districts ”(for competences and conflicts see, for example, Reich Defense Commissioner , Reich Governor ). In June 1945 the incorporation into the province of Thuringia was ordered by the new district president Hermann Brill under American occupation.

Post-war period and entry into the Basic Law

In 1948, in the Frankfurt documents , the three western allies called on the prime ministers of the states formed in their zones of occupation to review the state borders and propose changes. The borders of the individual countries should be checked and, if necessary, new countries should be created, taking into account 'traditional forms', whereby none should be too large or too small compared to the others.

Since the Prime Ministers could not agree on this question, the Parliamentary Council was asked to settle the reorganization question. Its draft found its way into Art. 29 GG. There was a binding mandate for the general restructuring of the federal territory ("The federal territory ... is to be restructured" - Paragraph 1). In addition, in parts of the territory whose national affiliation had changed after May 8, 1945 without a referendum, a referendum could be made within one year of the entry into force of the Basic Law (special reorganization, para. 2). If a referendum came about through the consent of at least 10% of the affected population, the federal government had to include the proposals in its draft law on the reorganization. After the adoption of the law, referendums were to be carried out in every part of the area whose nationality was to be changed (Paragraph 3). If the decision was negative in just one part of the territory, the law had to be introduced again in the German Bundestag and, once it had been passed again , would require a referendum in the entire federal territory (para. 4). The reorganization should be completed within three years of the proclamation of the Basic Law (para. 6).

In the letter of approval for the Basic Law , Art. 29 GG was suspended by the Allied military governors "until the time of the peace treaty". Only the special regulation for the south-west of Germany according to Art. 118 GG could come into force.

After the establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany

Several committees and expert commissions have submitted proposals for restructuring the federal states, such as the Bundestag committee for “internal reorganization”, the Luther committee established in 1952 or the Ernst commission appointed in 1970 . Also of importance in 1950 was the Weinheim meeting of the Institute for the Promotion of Public Affairs, at which fundamental considerations (“guiding principles”) for an optimal regional structure were discussed. Although the Luther Committee drew up several proposals for a reorganization of the Central-West German area, it did not consider a comprehensive reorganization of the states to be necessary.

Also from science (Rutz, Miegel, Ottnad and others) and politics (Döring, Apel and others) there have been several, in some cases very far-reaching restructuring proposals, none of which have been implemented so far. In many cases, the demand for a country restructuring is taken up for reasons of election tactics, often by politicians from donor countries in the financial equalization of the countries towards recipient countries.

The first elected state parliament of Schleswig-Holstein expressed its expectation of a reorganization: In 1949 it did not issue a state constitution , but a "state statute" to express its provisional character - analogous to the term "basic law". It was not until the constitution passed by the state parliament after the constitutional reform of 1990 that it was also called the state constitution. The efforts of Schleswig-Holstein to reorganize at that time are also reflected in the structure of the state's courts: it was not until 1991 that the state established its own higher administrative court , which from then on performed the tasks that the higher administrative court of Lüneburg had previously performed as the joint higher administrative court of the states of Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein . The Schleswig-Holstein State Constitutional Court only started work on May 1, 2008 . Until then, legal disputes under state constitutional law were carried out before the Federal Constitutional Court , which acted as the state constitutional court.

The formation of the state of Baden-Württemberg according to Art. 118 GG

In the south-west of Germany , territorial changes appeared urgent, as it was divided particularly unfavorably by the border between the French and the American occupation zone, which was based on the Karlsruhe-Stuttgart-Ulm motorway (today's A 8 ). The border between the occupation zones took no account of the historical areas and divided the previous states of Württemberg and Baden. The resulting tensions became an important engine for a new country solution in the southwest. Article 118 of the Basic Law deviated from the provision in Article 29 for a new structure by agreement between the three south-west German states. Without such an agreement, the reorganization should be regulated by federal law that had to provide for a referendum .

Since the states could not agree on a reorganization, this was regulated by the federal legislature. The voting mode was particularly controversial. The restructuring law of April 25, 1951 divided the voting area into four zones (Northern Württemberg, Northern Baden, Southern Württemberg-Hohenzollern, Southern Baden). The unification of the countries should be considered accepted if there was a majority in the entire voting area and in three of the four zones. Since a majority in the two Wuerttemberg zones as well as in North Baden was already foreseeable (this was shown by the outcome of a trial vote on September 24, 1950), this regulation favored the unification supporters.

After a fierce vote, the decision was made on December 9, 1951. In both parts of Württemberg the voters voted with 93.5% and 91.4% for the merger, in North Baden with 57.1%, while in South Baden only 37.8% were in favor. In three out of four voting districts there was therefore a majority in favor of the formation of the Southwest State, a total of 69.7% voted in favor of the formation of a new federal state. If the result had counted in total Baden, a majority of 52.2% would have been in favor of restoring the (separate) state of Baden. The first Prime Minister was elected at the session of the State Constituent Assembly on April 25, 1952. The new state of Baden-Württemberg was thus founded.

The popular initiative of 1956

The Paris Treaties ended the occupation statute and gave West Germany sovereignty. The one-year period of Article 29.2 of the Basic Law thus began to run. In 1956 a total of eight popular initiatives were carried out on the basis of the law on popular initiatives and referendums when the federal territory was restructured in accordance with Article 29 paragraphs 2 to 6 of the Basic Law of December 23, 1955, five of which were initially successful because the approval required in Article 29 paragraph 3 one tenth of those entitled to vote was reached:

- Restoration of the state of Oldenburg 12.9%

- Restoration of the state of Schaumburg-Lippe 15.3%

- Reclassification of the administrative districts of Koblenz and Trier of the state of Rhineland-Palatinate to North Rhine-Westphalia 14.2%

- Reclassification of the administrative districts of Montabaur and Rheinhessen of the State of Rhineland-Palatinate to Hesse 25.3% and 20.2% respectively

On May 30, 1956, the Federal Constitutional Court granted a complaint against the petition for a referendum to restore the state of Baden, which had been rejected by the Federal Ministry of the Interior. In the referendum that was then initiated in the Baden area, 15.1% of those entitled to vote requested a change in the state of the area. This meant that the ten percent threshold required for a referendum had also been exceeded in Baden.

The two Palatinate referendums (for reintegration to Bavaria and affiliation to Baden-Württemberg) failed with 7.6% and 9.3% respectively. Further motions for referendums (Lübeck, Geesthacht, Lindau, Achberg, 62 municipalities in southern Hesse) had already been rejected as inadmissible by the Federal Minister of the Interior or, in the Lindaus case, withdrawn. The refusal was upheld by the Federal Constitutional Court on December 5, 1956 in the Lübeck case .

The development up to the Hesse judgment of the Federal Constitutional Court in 1961

According to the original version of Article 29.3 of the Basic Law, the federal legislature should have submitted a law to reorganize the federal territory within three years. Once the law has been adopted, the part of the law relating to that area would have to be referred to a referendum in each area whose nationality was to be changed. If a referendum had already come about in accordance with paragraph 2, a referendum had to be held in the relevant area in any case. Since the three-year period had expired on May 5, 1958 without anything having happened, the Hessian state government sued in October 1958 for compliance with the federal obligation. In the so-called Hesse judgment of July 11, 1961, the Federal Constitutional Court rejected Hesse's complaint on the grounds that Article 29 of the Basic Law made the restructuring of the federal territory an exclusive matter for the federal government . At the same time, the court reaffirmed the obligation to reorganize the federal territory as a binding mandate to the competent constitutional organs and made it clear that a reorganization could not necessarily take place through a law in the technical sense (“uno actu”), but also in partial regulations (“phases”) .

The development up to the constitutional amendment of 1969

The subject of reorganization continued to be discussed in public. a. at the Loccum conference in 1968 or the fourth Cappenberg conversation of the Freiherr vom Stein Society in 1969.

On the political side, the grand coalition agreed to bring the pending referendums to a conclusion by amending the constitution. In the amended paragraph 3, binding deadlines have now been set for the required referendums. The referendums in Lower Saxony and Rhineland-Palatinate were to be held by March 31, 1975, and in Baden by June 30, 1970. The quorum was set at a quarter of the population eligible to vote in the state parliament. Paragraph 4 stipulated that the result of the referendum may only be deviated from if this is necessary to achieve the objectives of the reorganization according to paragraph 1 .

The Ernst Commission

In his policy statement October 28, 1969, Chancellor was Willy Brandt announced: "For the redrawing we will start from the benefits granted under Article 29 of the Basic Law Order." For an expert committee was set up after its chairman, former Secretary of State Professor Werner Ernst was named. After two years of work, the experts presented an expert opinion in 1973, which included an alternative proposal for northern Germany and central and southwestern Germany. In the north, either a single federal state north from Schleswig-Holstein , Hamburg , Bremen and Lower Saxony (solution A) or two new states should be formed: a north-east state from Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg and northern Lower Saxony (from Cuxhaven to Lüchow- Dannenberg) and a north-west state from Bremen and the rest of Lower Saxony (solution B). In the middle or south-west, either Rhineland-Palatinate (with the exception of most of the district of Germersheim ) with Hesse and the Saarland , including Mannheim , Heidelberg and the Rhein-Neckar district, should be merged into a new federal state in the Middle West (solution C); the majority of the Germersheim district would then have fallen to Baden-Württemberg. Or from Baden-Württemberg, Saarland, the Palatinate (including the Worms region ) and most of the Bergstrasse district , a new south-west state would be formed; the rest of Rhineland-Palatinate would then be united with Hesse to form a new state in the Middle West (solution D) Both alternatives could be combined with each other (AC, BC, AD, BD). In addition, the commission suggested minor border corrections in the areas of Ulm / Neu-Ulm , Wertheim / Tauberbischofsheim , Ahrweiler / Neuwied , Altenkirchen , Osnabrück / Tecklenburg and Kassel / Münden .

At the same time, the commission developed criteria for a qualification of the indicative terms of Article 29.1 of the Basic Law. In the first place she put the requirement of the capacity of each country, divided into the components economic, financial, political and administrative capacity. In order to be able to adequately fulfill administrative tasks, it considered a population of at least five million per country to be necessary. In contrast, she described the “country team bond” as a non-quantifiable and hardly objectifiable criterion.

After a relatively short discussion and a largely negative response from the countries concerned and large parts of the specialist community, the proposals were shelved. The population had reacted to the restructuring proposals with great serenity.

Referendums and constitutional amendments in the 1970s

A referendum was held in Baden on June 7, 1970: 81.9% of those who voted voted to remain with the state of Baden-Württemberg; 18.1% decided to restore the old state of Baden. Referendums were held on January 19, 1975 in Lower Saxony and Rhineland-Palatinate. It was decided:

- for the restoration of the state of Oldenburg 31% of the electorate

- for the restoration of the state of Schaumburg-Lippe 39.5% of the electorate

- for the reclassification of the administrative districts of Koblenz and Trier of the state of Rhineland-Palatinate to North Rhine-Westphalia 13%

- for the reclassification of the administrative districts of Montabaur and Rheinhessen of the state of Rhineland-Palatinate to Hesse 14.3% and 7.1% respectively.

The two referendums in Lower Saxony were therefore successful. The federal legislature was thus forced to act, because the result of a referendum could only be deviated from if this was necessary to achieve the objectives of the reorganization according to Paragraph 1. He responded by stipulating in the law regulating the state affiliation of the administrative district of Oldenburg and the district of Schaumburg-Lippe according to Article 29, Paragraph 3, Clause 2 of the Basic Law that both areas must remain with Lower Saxony. The reason was that the creation of the independent states of Oldenburg and Schaumburg-Lippe contradicted the goals of a timely reorganization. On August 1, 1978, the Federal Constitutional Court dismissed an action by the “Oldenburg People's Decision Committee” against this decision as inadmissible.

On August 23, 1976 the order for the reorganization of the federal territory, which had been binding until then, was changed into an optional provision : "The federal territory can be restructured ..." - Paragraph 1. At the same time, the guideline terms for a restructuring were changed. The concepts of size and efficiency now came first; the concept of the social structure was omitted, in its place came the requirements of spatial planning and regional planning. The referendum in the entire federal territory possible in the old paragraph 4 has been deleted; thus a change of nationality can no longer be forced against the will of the affected population. The new paragraph 4 enables referendums in “a contiguous, demarcated settlement and economic area whose parts are in several countries and which has at least one million inhabitants”.

The resumption of the AKK question and the Northern State discussion

At the end of the 1980s, the CDU MP Johannes Gerster tried to make it possible to reorganize the Mainz districts on the right bank of the Rhine (see AKK conflict ) by amending Article 29, Paragraph 7 of the Basic Law . However, the required two-thirds majority did not materialize. With the increase in the threshold for minor territorial changes in 1994 ( see section " Constitutional amendment of 1994 "), an improved legal basis for such a change in the Basic Law has been created. The discussion about a reorganization of northern Germany also briefly revived. Different variants (union of the four states or association of Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein) were discussed, but in the end the status quo remained .

After reunification

The formation of new federal states in East Germany

A general reorganization debate began shortly before reunification . Although there were proposals from science (Werner Rutz et al.) And politics ( Gobrecht ) for the introduction of only two, three or four countries in the territory of the GDR , the country introduction law of July 22, 1990 from the 14 districts (excluding East Berlin ) formed five states, which are largely based on the borders of the states that existed in the GDR until 1952. Saxony's attempt during the debates of the Joint Constitutional Commission to make Article 29 of the Basic Law into a “should-rule” again failed. A proposal by the Federal Minister of the Interior at the time, Schäuble , to delete the previously applicable material criteria for the reorganization and to create a temporary reorganization option in two phases (until the end of 1993 and end of 1999) was also rejected by the states with a large majority. But the commission recommended introducing a simplified reorganization procedure for the Berlin / Brandenburg area. In the course of a minor border correction according to Article 29, Paragraph 7 of the Basic Law, the Neuhaus Office was reclassified from Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania to Lower Saxony. The corresponding state treaty between the countries involved was concluded in March 1993 and came into force on June 30, 1993.

Franconian attempt at autonomy

In 1989/90 the Franconian Landsmannschaft tried to claim a federal state of Franconia through a reorganization of the federal territory according to Art. 29 GG with the help of a signature collection. It would have included the Franconian administrative districts of Bavaria as well as the Franconian areas belonging to Baden-Württemberg ( Tauberfranken ) and Thuringia. The collection of signatures was successful, but the Federal Ministry of the Interior rejected a referendum. A complaint by the initiators of the referendum before the Federal Constitutional Court against this decision in 1997 and another visit to the European Court of Human Rights in 1999 did not succeed.

1994 constitutional amendment

Article 118a of the Basic Law, which was newly introduced into the Basic Law in 1994, provides analogous to the provisions of the old Article 118 of the Basic Law for a unification of Berlin and Brandenburg, deviating from the provisions of Article 29 of the Basic Law, by agreement of both countries. Art. 29 GG was changed again and a. also proposes a restructuring through a state treaty between countries; the maximum number of inhabitants for minor changes to the area (according to paragraph 7) will be increased to 50,000.

Failed merger between Berlin and Brandenburg

The actual attempt to merge Berlin and Brandenburg into a new state Berlin-Brandenburg failed in May 1996. Although the state treaty between Berlin and Brandenburg had been adopted with the necessary two-thirds majority in both parliaments, this was in accordance with Article 3, Paragraph 1 of the restructuring treaty The necessary quorum of 25% of those entitled to vote in each of the two countries was not achieved. The merger agreement would not have come into force for lack of minimum approval. Overall, around 63% of the citizens who voted voted “no”, and just under 37% “yes”. The majority of Brandenburg's voters were particularly negative.

Central Germany

The initiative to form a federal state " Central Germany " repeatedly came from southern Saxony-Anhalt , although the name, the state capital and the structure below the state level have not been clarified. A collection of signatures, initiated and organized by Member of Parliament Bernward Rothe in the Halle (Saale) / Leipzig area , had collected over 8,000 supporters' signatures by July 2015. The then submitted application for a referendum to bring about a uniform nationality for this area was rejected on September 30, 2015 by the Federal Ministry of the Interior as “inadmissible and unfounded”. The reorganization area designated in the applications is not a contiguous, delimited settlement and economic area within the meaning of Article 29 (4) of the Basic Law. On November 2, 2015, Rothe lodged a complaint with the Federal Constitutional Court against this decision as the initiative's shop steward. In a letter dated November 14, 2018 to the person of trust for the referendum for the state of Saxony, Roland Mey, applicant for Bernward Rothe, the Federal Constitutional Court rejected the complaint, referring to the refusal by the Federal Ministry of the Interior.

Conclusion

It is questionable whether there will ever be a reorganization of the federal territory. This is less due to the procedure provided for in Article 29 of the Basic Law, which in its current form is "rather hindering than promoting" ( Schmidt-Jortzig ), than above all to the lack of political will and disinterest of the population. At most, demographic change and / or financial constraints could lead to country mergers in the coming years.

Restructuring with the aim of fewer countries

Proposals for the amalgamation of countries are repeatedly put forward from different sides.

The attempt by the Rhineland-Palatinate Prime Minister Kurt Beck to merge his state with Saarland in January 2003 met with rejection.

Also in 2003, Brandenburg's Prime Minister Matthias Platzeck called for Berlin , Brandenburg and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania to be merged .

The unification of the state of Bremen with the state of Lower Saxony to form a north-western state , which has been repeatedly discussed , currently has little chance of success. In parts of northern Germany , the discussion in politics and the media about a northern state is a constant topic .

In October 2014, the then Prime Minister of the Saarland , Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer , initiated the discussion about mergers between individual federal states. She called for a radical reorganization of the Federal Republic, if the reform of the financial equalization does not relieve the poor countries. "We would then have to talk about how we in Germany as a whole position ourselves for the future, specifically whether there will only be six or eight federal states in the future instead of the previous 16 states."

Arguments for and against a reorganization

The following arguments are typically put forward for reorganization:

- Saving of administrative costs by eliminating state parliaments and governments

- With fewer state elections, the long-term election campaign is restricted and a more reform-friendly federal policy emerges

- fairer distribution of votes in the Federal Council

- more weighty representation of the national interests in the central government

- common policy between a city-state and the surrounding country

- better development for previously divided metropolitan areas

- greater influence of the countries if they want to have a say as regions of the weight of the small to medium-sized EU member states in Europe.

Frequently mentioned arguments against reorganization are:

- Loss of regional identification and loss of power due to the loss of one's own political leadership

- Loss of seats in the Federal Council due to the favorable weighting of smaller countries in the Basic Law

- possible neglect of the surrounding area in the event of a merger with a city-state, if the policy focuses on the big city (example Berlin-Brandenburg), or just the opposite: loss of the city-state privilege through affiliation to a larger state (example Bremen-Lower Saxony)

- Taking over the problems of the predecessor countries such as national debt or structurally weak regions

- Much greater differences in the area and the number of inhabitants in the constituent states of other federal states ( Switzerland , USA , Brazil ) have not resulted in any demand for a reorganization

- Loss of closeness to the citizens of a government due to larger areas of responsibility and weakening of direct democracy

- possibly lower savings in administrative costs through the establishment of regional central authorities as compensation for lost capital functions.

Types and proposals of reorganization

There are different types of reorganization, which are usually combined in the various proposals as an overall concept: mergers of federal states (such as 1952 to Baden-Württemberg ) or border adjustments between two federal states (such as 1955, when the Lindau district back to Bavaria ) came.

Concrete proposals for a reorganization after 1990

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 17 countries | 9 countries | 8 countries | 7 countries | 6 countries | 6 countries | 6 countries |

| Reorganization (different country profile) |

fusion | Reorganization | Merger and split ST (similar population) |

Reorganization | fusion | Fusion (similar population) |

| Werner Rutz 1995 | Döring 2003 | Werner Rutz 1995 | Miegel 1990 and Ottnad 1997 | Werner Rutz 1995 | Apel 1997 | Barthelmess / Hübl , 2006 |

Almost all merger models force an average enlargement of the countries through amalgamation. Therefore, the key data of the countries to be created can be calculated arithmetically from the previous countries. Since these variants are formally "easy" to create, these models are at the front in the following detailed explanation.

In the following tables, the metropolitan regions in federal states in which their center is located - which does not necessarily mean that the majority of the residents live there, see Bremen - are printed in bold. On the other hand, small print means that the country concerned only has marginal shares.

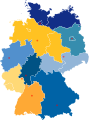

16 countries (current status)

According to the current status it looks like this:

- Country sizes between 419 and 70,552 km², on average 22,318 km² with a Gini coefficient of 56.80%

- Population between 0.7 and 18 million, on average 5.14 million with a Gini coefficient of 53.97%

- Population densities between 72 and 3834 inhabitants per km²

- The centers of the 11 metropolitan regions are in only 9 of the 16 countries.

- 3 countries manage without significant shares of metropolitan regions.

- 6 metropolitan regions are not marginally at national borders

9 country model

In this model, Schleswig-Holstein and Hamburg merge with Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Berlin with Brandenburg and Saxony-Anhalt, Saxony with Thuringia, Lower Saxony with Bremen and Rhineland-Palatinate with Saarland. This proposal was brought up by the FDP politician Walter Döring .

- Country sizes between 21,225 and 70,552 km²

- Population between 5 and 18 million

- Population densities between 158 and 528 inhabitants per km²

- The centers of the 11 metropolitan regions are in 8 of the 9 countries

- All countries have significant shares in metropolitan regions

- 3 metropolitan regions are not marginally on national borders

| country | Area [km²] |

Population [million] |

Inhabitants per km² |

Metropolitan areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baden-Württemberg | 35,751 | 11.070 | 310 | Stuttgart , Rhine-Neckar |

| Bavaria | 70,552 | 13,077 | 185 | Munich , Nuremberg , Rhine-Main |

| Berlin - Brandenburg - ST | 50,818 | 8.365 | 165 | Berlin |

| Hesse | 21,115 | 6.266 | 297 | Rhine-Main , Rhine-Neckar |

| Lower Saxony / Bremen | 48,029 | 8.665 | 180 | Hanover , Bremen , Hamburg |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 34,086 | 17.933 | 526 | Rhine-Ruhr |

| Northern State ( SH / HH / MV ) | 39,739 | 6.348 | 160 | Hamburg |

| Rhineland-Palatinate / Saarland | 22,422 | 5.075 | 226 | Rhine-Main , Rhine-Neckar |

| Thuringia - Saxony | 34,590 | 6.221 | 180 | Central Germany |

| Federal Republic of Germany | 357.104 | 83.019 | 232 | all |

8-country model according to Voscherau

In the Henning Voscherau model , Schleswig-Holstein merges with Hamburg and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saxony with Saxony-Anhalt, Rhineland-Palatinate with Saarland, Hesse and Thuringia, Berlin with Brandenburg and Lower Saxony with Bremen.

- Country sizes between 30,371 and 70,552 km², on average 44,638 km², with a Gini coefficient of 84.35%

- Population between 6 and 18 million, on average 10.28 million, with a Gini coefficient of 78.73%

- Population densities between 158 and 528 inhabitants per km²

- The centers of the 11 metropolitan regions are in all 8 countries

- All countries have significant shares in metropolitan regions

- 3 metropolitan regions are not marginally on national borders

| country |

Area [km²] |

Population [million] |

Inhabitants per km² |

Metropolitan areas |

Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baden-Württemberg | 35,751 | 10,750 | 301 | Stuttgart , Rhine-Neckar | Stuttgart |

| Bavaria | 70,552 | 12,520 | 177 | Munich , Nuremberg , Rhine-Main | Munich |

| Berlin-Brandenburg | 30,371 | 5,952 | 196 | Berlin | Potsdam |

| HE / TH / RP / SL | 59,709 | 13,445 | 225 | Rhine-Main , Rhine-Neckar , Central Germany | n / A |

| Lower Saxony / Bremen | 48,029 | 8,635 | 180 | Hanover , Bremen , Hamburg | Hanover |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 34,086 | 17,997 | 528 | Rhine-Ruhr | Dusseldorf |

| Northern State ( SH / HH / MV ) | 39,739 | 6.288 | 158 | Hamburg | Kiel or Schwerin |

| Saxony - Saxony-Anhalt | 38,865 | 6.632 | 171 | Central Germany | Dresden |

| Federal Republic of Germany | 357.104 | 82.219 | 230 | all | Berlin |

8-country model according to Rutz

The 8-country model according to Werner Rutz 1995 tries, on the one hand, to create countries of comparable size and, on the other, to expand economic areas - especially the 11 metropolitan regions - to just one country each. In addition to the division and merger of some countries, the model also provides for border corrections aimed at making the proposals capable of reaching a consensus among the populations of the countries - e. B. Compensation areas to Bavaria for the surrender of Neu-Ulm (merger with Ulm in the south-west state) and the Aschaffenburg area ( metropolitan region Rhine-Main ). In some cases, historical areas are also growing - e.g. B. the Palatinate divided by the Rhine - together again.

The following fusions, splits and shifts are mainly considered:

- Nordelbingen (“Northern State”) is created from the merger of Schleswig-Holstein , Hamburg , the west of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (Mecklenburg except its extreme east) and the strip in northeast Lower Saxony belonging to the Hamburg metropolitan region .

- Lower Saxony merges with Bremen , gives a strip near the Elbe in the northeast to Nordelbingen and receives large parts of the East Westphalia-Lippe region and the Tecklenburger Land from North Rhine-Westphalia.

- North Rhine-Westphalia gives the two regions mentioned in the north to Lower Saxony and receives u. a. the upper district belongingto the Siegerland economic area(previously part of the Altenkirchen (Westerwald) district , Rhineland-Palatinate) andplaces in the Rhine Valley bordering the Bonn economic area(previously Ahrweiler and Neuwied district ).

- Middle Rhine-Hesse is created by the merger of Hesse with the north of Rhineland-Palatinate (former Trier administrative district and large parts of Rheinhessen ). The area of Aschaffenburg ( Rhine-Main area ) is integrated from today's Bavaria, but southern parts of the country ( Odenwald and Bergstrasse ) are transferred to the southwestern state of Palatinate-Swabia .

- Palatinate-Swabia is created through the merger of Baden-Württemberg with the Palatinate on the left bank of the Rhine , the south of Rheinhessen ( Worms ) - both previously in Rhineland-Palatinate - and the Saarland . Ulm is expanded to include the Neu-Ulm area (previously Bavaria), parts of Upper Swabia (north of Lake Constance ) and the Heidenheim an der Brenz area go to Bavaria in return.

- In addition to the postponements already listed, Bavaria will receive some Franconian communities in the south of the Hildburghausen and Sonneberg districts of Thuringia.

- (Greater) Brandenburg arises from the merger of Brandenburg , Berlin , the north of Saxony-Anhalt and Western Pomerania, along with Mecklenburg-Strelitz (previously east of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania). Parts in the southwest go to Thuringia-Saxony .

- Thuringia-Saxony is created through the merger of Thuringia , Saxony and the south of Saxony-Anhalt as well as south-western parts of today's state of Brandenburg.

Parameters for this reorganization:

- Country sizes between 30,317 and 71,337 km²

- Population between 6.3 and 16.3 million

- Population densities between 156 and 538 inhabitants per km²

- All 11 metropolitan regions are each undivided in exactly one of the 8 countries

- The 8 largest metropolitan regions are each located in exactly one of the 8 countries

- Every country has at least one and at most two metropolitan regions

- About 50% to 75% of the population of any country lives in metropolitan areas

With regard to the population figures of the metropolitan regions (MPR) it should be noted that these include a surrounding area that is more or less arbitrarily included in spatial planning. So z. B. the metropolitan region of Berlin-Brandenburg from exactly two previous countries, while the metropolitan region of Stuttgart is relatively close to the city. The city of Worms and the Bergstrasse district have so far been part of two different metropolitan regions ( Rhine-Main and Rhine-Neckar ) at the same time .

| country |

Area [km²] |

Population [million] |

Inhabitants per km² |

Metropolitan areas |

Population per MPR |

Population in MPR [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bavaria | 71,337 | 11.4 | 160 |

Munich Nuremberg |

5.71 3.56 |

76 |

| Brandenburg | 50,635 | 7.9 | 156 | Berlin | 6.00 | 75 |

| Middle Rhine-Hesse | 35,011 | 8.1 | 231 | Rhine-Main | 5.70 | 68 |

| Lower Saxony | 44,182 | 8.9 | 201 |

Hanover northwest |

3.78 2.72 |

71 |

| North Elbingen | 37,975 | 6.3 | 166 | Hamburg | 5.00 | 68 |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 30,317 | 16.3 | 538 | Rhine-Ruhr | 10.68 | 70 |

| Palatinate Swabia | 42,855 | 12.8 | 299 |

Stuttgart Rhine-Neckar |

5.29 2.40 |

60 |

| Thuringia Saxony | 44,226 | 8.9 | 201 | Central Germany | 2.40 | 49 |

| Federal Republic of Germany | 357.104 | 82.219 | 230 | all | 57.98 | 71 |

7-country model

The 7-country model according to Miegel and Ottnad is, apart from the division of Saxony-Anhalt , a pure merger model.

In this model, Schleswig-Holstein merges with Hamburg, Lower Saxony and Bremen. Berlin merges with Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and the north of Saxony-Anhalt. Saxony merges with Thuringia and the south of Saxony-Anhalt. The state of Rhineland-Palatinate is merging with Saarland and Hesse.

- Country sizes between 34,086 and 70,552 km²

- Population between 8 and 18 million

- Population densities between 134 and 528 inhabitants per km²

- In each country there is at least 1 center of one of the 11 metropolitan regions

- 1 federal state is home to 3 metropolitan regions

- 1 Metropolitan region is not marginally at national borders

| country |

Area [km²] |

Population [million] |

Inhabitants per km² |

Metropolitan areas |

Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baden-Württemberg | 35,751 | 10,750 | 301 | Stuttgart , Rhine-Neckar | Stuttgart |

| Bavaria | 70,552 | 12,520 | 177 | Munich , Nuremberg , Rhine-Main | Munich |

| Berlin - BB / MV / - ST-North | 63,942 | 8,551 | 134 | Berlin , Hamburg | Potsdam |

| Hesse / RP / Saarland | 43,537 | 11,156 | 256 | Rhine-Main , Rhine-Neckar | Wiesbaden and / or Mainz |

| Lower Saxony / SH / HH / HB | 64,584 | 13,243 | 205 | Hamburg , Hanover , Bremen | Hanover |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 34,086 | 17,997 | 528 | Rhine-Ruhr | Dusseldorf |

| Thuringia - Saxony - ST-South | 44,650 | 7,972 | 179 | Central Germany | Dresden |

| Federal Republic of Germany | 357.104 | 82.219 | 230 | all | Berlin |

6-country model

The model by Andreas Barthelmess and Philipp Hübl goes a little further than the model by Henning Voscherau. In addition to his model, the states of Berlin-Brandenburg and Saxony / Saxony-Anhalt, as well as the states of Lower Saxony / Bremen , merge with Hamburg / Schleswig-Holstein / Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

- Country sizes between 34,086 and 87,768 km², on average 59,157 km², with a Gini coefficient of 82.16%

- Population between 11 and 18 million, on average 13.70 million, with a Gini coefficient of 91.01%

- Population densities between 170 and 528 inhabitants per km²

- The centers of the 11 metropolitan regions are in all 6 countries

- All countries have at least one metropolitan area

- 3 metropolitan regions are not marginally on national borders

| country |

Area [km²] |

Population [million] |

Inhabitants per km² |

Metropolitan areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baden-Württemberg | 35,751 | 11.070 | 310 | Stuttgart , Rhine-Neckar |

| Bavaria | 70,552 | 13,077 | 185 | Munich , Nuremberg , Rhine-Main |

| Middle Rhine-Thuringia ( HE / TH / RP / SL ) | 59,709 | 13,484 | 226 | Rhine-Main , Rhine-Neckar , Central Germany |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 34,086 | 17.933 | 526 | Rhine-Ruhr |

| Hanseatic League ( NI / SH / HH / MV / HB ) | 87,768 | 15.013 | 171 | Hamburg , Hanover , Bremen |

| Brandenburg-Saxony ( SN / BE / BB / ST ) | 69,236 | 12,443 | 180 | Berlin , Central Germany |

| Federal Republic of Germany | 357.104 | 83.019 | 232 | all |

Alternatively: 17-country model according to Rutz

As an alternative to the solutions that provide for a reduction in the number of countries, Werner Rutz has also presented a model that roughly preserves the number of countries, but is much more oriented towards the existing conurbations and economic areas. It was investigated to what extent a conurbation appears suitable to become the core of a (possibly smaller) country. For this purpose, u. a. checked whether the respective agglomeration, together with its surrounding area, would have a minimum population of 1.9 million (comparative figure for Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania ) or not.

The emerging countries would be comparatively homogeneous in terms of their national team. Following this, the naming z. Some of the medieval territorial names.

This model gives:

- Country sizes between 8,438 and 40,461 km²

- Population between just under 2 and 16 million

- Population densities between 81 (MV) and 152 and 570 inhabitants per km²

- The eleven metropolitan regions are each located in different countries.

- Even smaller metropolitan areas remain undivided.

In the “Centers” column, metropolitan regions are each printed in bold. Larger cities in the metropolitan region not mentioned by name are also located in the respective country. However, u. U. peripheral areas, which have so far been counted as part of the metropolitan region for spatial planning purposes, in neighboring countries, as they are more likely to be assigned to the catchment area of a smaller center there.

| Country (mainly includes) |

countries |

Area [km²] |

Population [million] |

Inhabitants per km² |

Centers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baiern ( sic !) Upper Bavaria , Lower Bavaria , Upper Palatinate |

BY | 38,158 | 6.09 | 160 | Munich , Regensburg , Ingolstadt , Passau , Landshut |

| Brandenburg Brandenburg , Berlin , northern half of Saxony-Anhalt |

BB, BE, ST | 40,461 | 7.10 | 175 | Berlin , Magdeburg |

| Ems-Weser-Land Free Hanseatic City of Bremen and western Lower Saxony , Tecklenburger Land |

NI, HB , NW | 24,243 | 3.84 | 158 | Bremen , Osnabrück |

| Engern Southern half of the medieval Engern - Ostwestfalen-Lippe , districts of Holzminden , Hameln-Pyrmont and Schaumburg |

NW , NI | 8,866 | 2.36 | 266 | Bielefeld , Paderborn , Minden |

| Hessen-Nassau Hessen , Rheinhessen , Middle Rhine , Lower Main |

HE, RP | 26,939 | 7.20 | 270 | Rhine-Main , Kassel , Koblenz , Marburg |

| Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania |

MV | 22,708 | 1.84 | 81 | Rostock , Schwerin |

| North Rhine-Westphalia North Rhine-Westphalia excluding Ostwestfalen-Lippe , the extreme north of Rhineland-Palatinate |

NW , RP | 27,591 | 15.74 | 570 | Rhine-Ruhr , Aachen , Munster , Siegen |

| Lower Swabia Württemberg north of the Swabian Alb |

BW | 8,438 | 3.70 | 438 | Stuttgart |

| Oberschwaben Oberschwaben inc. of the Bavarian part |

BY, BW | 17,991 | 2.90 | 161 | Augsburg , Ulm , Constance , Kempten (Allgäu) |

| Ostfalen In the former West Germany situated part of the medieval Ostfalen - south-east of Lower Saxony |

NI | 14,038 | 3.27 | 167 | Hanover , Braunschweig , Göttingen , Goslar |

| East Franconia Upper , Lower and Middle Franconia ; Districts Main-Tauber , Hohenlohekreis , district Schwäbisch Hall , south of the districts Sonneberg and Hildburghausen |

BY , BW | 24,751 | 4.00 | 162 | Nuremberg , Würzburg |

| Rheinpfalz-Baden Entire Electoral Palatinate east of the Palatinate Forest , north of Baden |

BW, RP | 9,690 | 3.87 | 399 | Rhine-Neckar , Karlsruhe , Pforzheim |

| Saxony Saxony , southern half of Saxony-Anhalt |

SN, ST , TH | 27.405 | 6.33 | 231 | Central Germany , Dessau-Roßlau |

| Schleswig-Holstein Schleswig-Holstein , Hamburg , northeast Lower Saxony |

SH, HH, NI | 25,441 | 5.21 | 205 | Hamburg , Lübeck , Kiel |

| Thuringia Thuringia , parts of southern Saxony-Anhalt |

TH | 16,776 | 2.55 | 152 | Erfurt , Gera , Jena |

| Trier-Saarpfalz Rhineland-Palatinate to the southeast, Saarland |

RP, SL | 13,622 | 2.48 | 182 | Saarbrücken , Trier , Kaiserslautern |

| Zähringen South Baden or the German part of Zähringen |

BW | 9,613 | 2.10 | 218 | Freiburg , Villingen-Schwenningen , Offenburg |

| Federal Republic of Germany | all | 357.104 | 82.219 | 230 | all |

Alternatives to reorganization

As an alternative to a reorganization, there are numerous forms of cooperation between the countries, which are regulated in each case by international treaties. Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate jointly financed the research institute for horticulture and viticulture in Geisenheim until 2011 ; Berlin and Brandenburg each have a common finance, state labor, state social and higher administrative court; Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein had a joint higher administrative court in Lüneburg until 1991. Some federal states also cooperate by amalgamating authorities; z. B. Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein have merged the data centers, calibration offices and the Landesbanken. However, these collaborations are always limited to certain points; The focus is on a technical and organizational division of tasks. There is no nationwide cross-border cooperation.

At the end of the 1960s, the so-called community tasks were included in the Basic Law. In this way, the federal government was supposed to take part in the fulfillment of certain tasks (e.g. university building or coastal protection) that individual states were unable to perform. The joint tasks were, however, partially abolished again in the course of the federalism reform.

Alternatives to the previous territorial division were usually developed for economic or administrative reasons, if the given division into federal states was found to be impractical (e.g. too small-scale) and attempts were made to create larger units (though completely uncoordinated).

Various public and private institutions have given themselves an organizational-territorial structure, when it seemed appropriate to them, which in some cases deviates considerably from the structure in federal states. Either several federal states were merged into larger units or larger units were created in some cases without considering existing state borders. Institutions that have a high level of interest in efficient spatial (decision-making) structures are, for example, the Federal Police, the Federal Employment Agency or the Technical Relief Organization. Although these structures have their own logic, it is noteworthy that a number of 8 to 10 spatial units have emerged and the city-states are almost always part of a larger unit.

But the regional broadcasting corporations of the ARD are also trying to shape regional affiliation across national borders (“Central Germany”, “SWR3-Land”). Postal code regions and telephone area codes differ even more considerably from the existing country structure. Ultimately, this resulted in multiple overlapping units.

ARD

9 state broadcastersFederal Police

8 regional officesFederal Police (old)

5 praesidia and 19 officesTHW

8 regional associationsDGB

9 districtsBundesbank

9 headquarters (former Land Central Banks )DFB

5 regional and 21 regional associationsGerman pension insurance

14 regional carriersTelephone prefixes

8 area codes

See also

literature

- Daniel Buscher: The state in times of the financial crisis . A contribution to the reform of the German financial and budgetary regulations (federalism reform). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-13166-2 .

- Benjamin-Immanuel Hoff : Country reorganization. A model for East Germany . Leske and Budrich, Opladen 2002, ISBN 3-8100-3267-0 (Stadtforschung aktuell 85).

- Rudolf Hrbek: The problem of the restructuring of the federal territory . In: From Politics and Contemporary History . Supplement to the weekly newspaper Parliament". B 46/71, p. 3 ff .

- Hartmut Kühne: Federalism is an obsolete model? Renew the state - break the blockades of reform. Olzog, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-7892-8138-7 .

- Klaus-Jürgen Matz : Country reorganization . On the genesis of a German obsession since the end of the Old Kingdom. Schulz-Kirchner Verlag, Idstein 1997, ISBN 3-8248-0029-2 (Historical Seminar NF 9).

- Werner Rutz, Konrad Scherf, Wilfried Strenz: The five new federal states . Historically justified, politically wanted, and sensible in the future? Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1993, ISBN 3-534-12114-7 .

- Werner Rutz: The division of the Federal Republic into countries . A new overall concept for the territorial status after 1990. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1995, ISBN 3-7890-3686-2 (Föderalismus-Studien 4).

- Reinhard Schiffers: Fewer countries - more federalism? The reorganization of the federal territory in the conflict of opinions 1948 / 49–1990. A documentation. Droste, Düsseldorf 1996, ISBN 3-7700-5195-5 (documents and texts / Commission for the history of parliamentarism and the political parties 3).

- Reinhard Timmer: reorganization of the federal territory . Short version of the report of the Expert Commission for the reorganization of the federal territory. Ed .: Expert commission for the reorganization of the federal territory. Carl Heymanns, Cologne [a. a.] 1974 (on behalf of the Federal Ministry of the Interior ).

Web links

- Reorganization of the Federal Republic of Germany

- "Eight, six or seventeen countries for the republic"

- "The state of Baden-Württemberg and the possible border changes in the event of a reorganization of the federal territory" (PDF; 518 KiB)

- BVerfGE 1, 14 - Southwest State

- "State reorganization as a reform option" with special consideration of Berlin-Brandenburg (PDF; 530 KiB)

- Edzard Schmidt-Jortzig : Suggestion for an extension of the discussion on Art. 29 GG (PDF; 128 KiB)

- Reorganization of the federal territory - initiative country merger

- Academy for Spatial Research and Regional Planning : Fewer Federal States - More Efficiency? , Press release October 18, 2011

- Academy for Spatial Research and Regional Planning : Territorial Structure of the German Federal State - Problems and Reform Options , Position Paper 100, 2014

- New countries only by referendum. German Bundestag , accessed on June 5, 2016 .

- IG reorganization: reorganization of the federal territory

Individual evidence

- ^ Adrian Ottnad, Edith Linnartz: Seven are more than sixteen. A proposal for the reorganization of the federal states , in: Information on Spatial Development (IzR) 10.1998, ed. from the Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning , Bonn 1998, pp. 647–659.

- ↑ GG - single standard. In: www.gesetze-im-internet.de. Retrieved March 25, 2016 .

- ↑ See overview of amendments to Article 29 of the Basic Law on www.verfassungen.de .

- ^ Documents on the future political development of Germany ("Frankfurter Documents"), July 1, 1948 . With an introduction by Rudolf Morsey . In: 1000dokumente.de

- ^ Klaus-Jürgen Matz: Country reorganization. On the genesis of a German obsession since the end of the Old Kingdom. Schulz-Kirchner Verlag, Idstein 1997, p. 29.

- ^ Ernst-Hermann Grefe: The Mediatization Question and the Principality of Lippe in the years 1848–1849. Natural science and historical association for the state of Lippe, Detmold 1965, p. 64.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 794-796.

- ↑ Karl-Ulrich Gelberg: Restructuring of the Empire (1919-1945) , in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns .

- ↑ Everhard Holtmann : The crisis of federalism and local self-government , in: Ders. (Ed.): The Weimar Republic. The end of democracy. Volume 3: 1929-1933. Munich: Bavarian State Center for Political Education 1995 (workbook 83), p. 172.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Thuringia Handbook , 1999, p. 40 ; Decree of the Führer on the formation of the provinces of Kurhessen and Nassau , Decree of the Führer on the subdivision of the Province of Saxony , accessed on July 24, 2018.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Thuringia Handbook , 1999, p. 227 .

- ^ The federal states: contributions to the restructuring of the Federal Republic; Discussion and results of the Weinheim conference / presentations by HL Brill… , Inst. Affairs, Frankfurt am Main 1950 (Scientific series of the Institute for the Promotion of Public Affairs eV; 9), p. 47 f.

- ↑ Frank Meerkamp: The Quorenfrage popularly legislative procedure: the importance and development civil society and democracy. Wiesbaden 2011, 345

- ↑ Reinhard Schiffers: Fewer countries - more federalism? The reorganization of the federal territory in the conflict of opinions 1948 / 49–1990. A documentation. Droste, Düsseldorf 1996; Document No. 20b April 9-22. and 3. – 16.9.1956: Results of the approved referendums .

- ↑ BVerfGE 5, 34 - Baden vote

- ^ Results of previous votes in Baden-Württemberg

- ↑ BVerfGE 13, 54 - reorganization of Hesse.

- ↑ Schiffers, Fewer Countries - More Federalism? , Droste, Düsseldorf 1996; Document No. 31 1965–1970: Meetings on the Question of Restructuring .

- ^ Government declaration by Federal Chancellor Willy Brandt before the German Bundestag in Bonn on October 28, 1969.

- ↑ Schiffers: Fewer Countries - More Federalism? , Droste, Düsseldorf 1996; Document No. 40a February 20, 1973: Ernst's report on the restructuring .

- ^ Erich Röper: Aspects of the reorganization of the federal territory. In: The State . 14th year (1975), p. 305.

- ^ Edda Müller: The status of the restructuring discussion. In: Public Administration . 27. Vol. (1974), Issue 1, p. 1.

- ↑ Schiffers, Fewer Countries - More Federalism? , Droste, Düsseldorf 1996; Document No. 37d 1.6.1970: Result of the referendum in Baden .

- ↑ Schiffers: Fewer Countries - More Federalism? , Droste, Düsseldorf 1996; Document no. 46a 19.1.1975 Results of the referendums in Lower Saxony and Rhineland-Palatinate .

- ↑ Bundesrat, Drs. 551/75, September 5, 1975.

- ↑ BVerfGE 49, 15 - Oldenburg referendum.

- ↑ One country - 16 countries - or can it be a little less?

- ↑ Reinhard Schiffers: Less countries, more federalism? , Droste, Düsseldorf 1996, p. 88 f.

- ↑ BVerfGE 96, 139 - Popular initiative in Franconia.

- ↑ Referendum Mitteldeutschland , Neugliederung-bundesgebiet.de, accessed on September 15, 2015.

- ↑ Decision of the Federal Ministry of the Interior 09/30/2015, Neugliederung-bundesgebiet.de, accessed on November 5, 2015.

- ↑ Complaint of November 2, 2015 to the Federal Constitutional Court regarding the admission of a referendum in accordance with Art. 29 para. 4 GG in the Leipzig / Halle (Saale) area , Neugliederung-bundesgebiet.de, accessed on November 5, 2015.

- ↑ Central Germany's referendum also fails at the Federal Constitutional Court , Leipziger Internet Zeitung of November 24, 2018

- ↑ Commission of the Bundestag and Bundesrat for the modernization of the federal system Commission printed matter 0033 (PDF; 128 kB).

- ↑ "The political will to reorganize the federal territory according to the indicative terms mentioned in Art. 29 GG [...] still does not exist." - Werner Rutz, How many countries does the republic need? , in: RUBIN 2/96; P. 25.

- ↑ This statement is also indicative: "It was [...] the lack of political backing that led to the implementation of the investigation [meaning the Ernst report, editor's note. Ed.] Failed - which the minister responsible at the time admitted frankly and freely (cf. Genscher 1995: 124 f.) ) 5/2014, ed. from the Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning, Bonn 1998, p. 394.

- ↑ "Debt brake increases pressure for country mergers" , tagesspiegel.de (August 19, 2010), accessed on June 6, 2016.

- ↑ Kramp-Karrenbauer: "Only six or eight federal states" , spiegel.de, accessed on October 24, 2014.

- ↑ Saarland has to become leaner. Sustainability requires further cost-cutting measures. ( Memento from May 18, 2014 in the web archive archive.today ) saarbruecker-zeitung.de

- ↑ Cost savings after country mergers. www.neugliederung-bundesgebiet.de

- ↑ Werner Rutz: The division of the Federal Republic into Länder: a new overall concept for the territorial status after 1990. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1995, p. 96.

- ↑ The suggestion to accomplish this kind of compensation by expanding or building up central bodies ("provinces") was made at the Cappenberg conversation. Cf. Land reform and landscapes (1969 - Münster), series of publications Cappenberg Talks, Vol. 3. G. Grotesche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Cologne / Berlin 1970, pp. 83 f.

- ↑ For his six-country solution, Rutz also suggests the establishment of centralized entities (“ landscape associations of a new kind”), which are usually to be merged with existing government districts or regional planning agencies in order to ensure “economical and effective state administration” . Werner Rutz: The division of the Federal Republic into states: a new overall concept for the territorial status after 1990. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1995, p. 78 ff.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Source: Federal and State Statistical Offices : Territory and Population ( Memento of July 6, 2017 in the Internet Archive ), as of December 31, 2007, inh. / Km² calculated from the original figures . All figures rounded to the nearest whole number.

- ↑ a b Area and population | Drupal | Statisticsportal.de. Retrieved July 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Federal states: Reorganization of Germany stimulated , Spiegel Online , January 19, 2003, accessed on June 7, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d Area and population | Drupal | Statisticsportal.de. Retrieved on July 29, 2020 (Figures for merged countries calculated from the figures for the respective federal states and rounded off commercially.).

- ↑ Wolfgang Clement , Friedrich Merz : What is to be done now. Freiburg 2010, p. 89 f .; No Saarland, no Bremen, no Hesse. Another option: Germany with eight countries , Focus Online , October 30, 2014, accessed on January 9, 2015.

- ↑ Werner Rutz: The division of the Federal Republic into Länder: a new overall concept for the territorial status after 1990. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1995, pp. 69–72.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Source: "Land reorganization as reform option" with special consideration of Berlin-Brandenburg (PDF; 530 kB)

- ↑ Source: "The state of Baden-Württemberg and the possible border changes in the event of a restructuring of the federal territory" , in particular map p. 8 (PDF; 518 kB)

- ↑ see list of metropolitan regions in Germany

- ^ Adrian Ottnad, Edith Linnartz: Seven are more than sixteen. A proposal for the reorganization of the federal states , in: Information on Spatial Development (IzR) 10.1998, ed. from the Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning , Bonn 1998, pp. 647–659.

- ↑ State reorganization: Plea for the strong six , Spiegel Online, December 15, 2006, accessed on October 4, 2012.

- ↑ Werner Rutz: The division of the Federal Republic into Länder: a new overall concept for the territorial status after 1990. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1995, pp. 82–95.

- ↑ a b c Werner Rutz: How many countries does the republic need? in: RUBIN 2/96 , pp. 24-29.

- ↑ Markus Eltges: Selected territorial divisions in Germany , in: Information on Spatial Development (IzR) 5.2014 , ed. from the Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning, Bonn 2014, p. 489.